Ted Sturgeon on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Theodore Sturgeon (; born Edward Hamilton Waldo, February 26, 1918 – May 8, 1985) was an American author of primarily

Theodore Sturgeon (; born Edward Hamilton Waldo, February 26, 1918 – May 8, 1985) was an American author of primarily

The Theodore Sturgeon Page

- an informative and comprehensive fan site

The Theodore Sturgeon Literary Trust

– owners of Sturgeon copyrights, information on Sturgeon publications * Theodore Sturgeon Papers

MS 303

an

MS 254

housed at th

Kenneth Spencer Research Library

University of Kansas * * * * *

at Free Speculative Fiction Online

* ttp://efanzines.com/SFC/SteamEngineTime/SET13.pdf The Work of Theodore Sturgeon– lengthy biographical and critical study of Sturgeon {{DEFAULTSORT:Sturgeon, Theodore 1918 births 1985 deaths American horror writers American science fiction writers American speculative fiction editors Hugo Award–winning writers Nebula Award winners People from Springfield, Oregon Writers from Staten Island American science fiction critics Science Fiction Hall of Fame inductees World Fantasy Award–winning writers 20th-century American novelists American male novelists American atheists American Scientologists Journalists from New York City 20th-century American male writers Novelists from New York (state) American male non-fiction writers American weird fiction writers

Theodore Sturgeon (; born Edward Hamilton Waldo, February 26, 1918 – May 8, 1985) was an American author of primarily

Theodore Sturgeon (; born Edward Hamilton Waldo, February 26, 1918 – May 8, 1985) was an American author of primarily fantasy

Fantasy is a genre of speculative fiction that involves supernatural or Magic (supernatural), magical elements, often including Fictional universe, imaginary places and Legendary creature, creatures.

The genre's roots lie in oral traditions, ...

, science fiction

Science fiction (often shortened to sci-fi or abbreviated SF) is a genre of speculative fiction that deals with imaginative and futuristic concepts. These concepts may include information technology and robotics, biological manipulations, space ...

, and horror, as well as a critic. He wrote approximately 400 reviews and more than 120 short stories, 11 novels, and several scripts for '' Star Trek: The Original Series''.

Sturgeon's science fiction novel ''More Than Human

''More Than Human'' is a 1953 science fiction fix-up novel by American writer Theodore Sturgeon. It is a revision and expansion of his 1952 novella '' Baby Is Three'', which is bracketed by two additional parts written for the novel, "The F ...

'' (1953) won the 1954 International Fantasy Award (for SF and fantasy) as the year's best novel, and the Science Fiction Writers of America

The Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America, doing business as Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers Association and commonly known as SFWA ( or ) is a nonprofit 501(c)(3) organization of professional science fiction and fantasy writers. Whi ...

ranked " Baby Is Three" number five among the " Greatest Science Fiction Novellas of All Time" to 1964. Ranked by votes for all of their pre-1965 novellas, Sturgeon was second among authors, behind Robert Heinlein

Robert Anson Heinlein ( ; July 7, 1907 – May 8, 1988) was an American science fiction author, aeronautical engineer, and naval officer. Sometimes called the "dean of science fiction writers", he was among the first to emphasize scientific acc ...

.

The Science Fiction and Fantasy Hall of Fame

The Museum of Pop Culture (or MoPOP) is a nonprofit museum in Seattle, Washington, United States, dedicated to contemporary popular culture. It was founded by Microsoft co-founder Paul Allen in 2000 as the Experience Music Project. Since then ...

inducted Sturgeon in 2000, its fifth class of two dead and two living writers.

Biography

Youth and education

Sturgeon was born Edward Hamilton Waldo inStaten Island, New York

Staten Island ( ) is the southernmost of the boroughs of New York City, five boroughs of New York City, coextensive with Richmond County and situated at the southernmost point of New York (state), New York. The borough is separated from the ad ...

, in 1918. His name was legally changed to Theodore Sturgeon at age eleven after his mother's divorce and subsequent marriage to William Dicky ("Argyll") Sturgeon.

Theodore's birth father, Edward Waldo, was a color and dye manufacturer of middling success. With his second wife, Anne, he had one daughter, Joan. Theodore's mother, Christine Hamilton Dicker (Waldo) Sturgeon, was a well-educated writer, watercolorist, and poet who published journalism, poetry, and fiction under the name Felix Sturgeon. His stepfather, William Dickie Sturgeon (sometimes known as Argyll), was a mathematics teacher at a prep school and then Romance Languages Professor at Drexel Institute (later Drexel Institute of Technology

Drexel University is a private research university with its main campus in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States. Drexel's undergraduate school was founded in 1891 by Anthony J. Drexel, a financier and philanthropist. Founded as Drexel In ...

) in Philadelphia. Sturgeon's account of his stepfather is included in a posthumous memoir.Sturgeon, Theodore (1993). ''Argyll; A Memoir'', Entwhistle Books. Sturgeon's sibling, Peter Sturgeon, wrote technical material for the pharmaceutical industry and the WHO

The World Health Organization (WHO) is a specialized agency of the United Nations which coordinates responses to international public health issues and emergencies. It is headquartered in Geneva, Switzerland, and has 6 regional offices and 15 ...

, and founded the American branch of Mensa.

Upon graduating from high school in 1935, Sturgeon pleaded to be allowed to attend college, but his step-father refused to support him, citing his frivolity.

Great Depression and the war years

The young Sturgeon held a wide variety of jobs. As an adolescent, he wanted to be a circusacrobat

Acrobatics () is the performance of human feats of balance, agility, and motor coordination. Acrobatic skills are used in performing arts, sporting events, and martial arts. Extensive use of acrobatic skills are most often performed in acro d ...

; an episode of rheumatic fever

Rheumatic fever (RF) is an inflammation#Disorders, inflammatory disease that can involve the heart, joints, skin, and brain. The disease typically develops two to four weeks after a Streptococcal pharyngitis, streptococcal throat infection. Si ...

prevented him from pursuing this. From 1935 (aged 17) to 1938, he was a sailor in the merchant marine, and elements of that experience found their way into several stories. He sold refrigerator

A refrigerator, commonly shortened to fridge, is a commercial and home appliance consisting of a thermal insulation, thermally insulated compartment and a heat pump (mechanical, electronic or chemical) that transfers heat from its inside to ...

s door to door. He managed a hotel in Jamaica

Jamaica is an island country in the Caribbean Sea and the West Indies. At , it is the third-largest island—after Cuba and Hispaniola—of the Greater Antilles and the Caribbean. Jamaica lies about south of Cuba, west of Hispaniola (the is ...

around 1940–1941, worked in several construction and infrastructure jobs (driving a bulldozer in Puerto Rico

; abbreviated PR), officially the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico, is a Government of Puerto Rico, self-governing Caribbean Geography of Puerto Rico, archipelago and island organized as an Territories of the United States, unincorporated territo ...

, operating a filling station

A filling station (also known as a gas station [] or petrol station []) is a facility that sells fuel and engine lubricants for motor vehicles. The most common fuels sold are gasoline (or petrol) and diesel fuel.

Fuel dispensers are used to ...

and truck lubrication center, work at a drydock

A dry dock (sometimes drydock or dry-dock) is a narrow basin or vessel that can be flooded to allow a load to be floated in, then drained to allow that load to come to rest on a dry platform. Dry docks are used for the construction, maintenance, ...

) for the US Army in the early war years, and by 1944 was an advertising copywriter. In addition to freelance fiction and television writing, in New York City he opened his own literary agency (which was eventually transferred to Scott Meredith), worked for ''Fortune

Fortune may refer to:

General

* Fortuna or Fortune, the Roman goddess of luck

* Luck

* Wealth

* Fate

* Fortune, a prediction made in fortune-telling

* Fortune, in a fortune cookie

Arts and entertainment Film and television

* ''The Fortune'' (19 ...

'' magazine and other Time Inc. properties on circulation, and edited various publications.

Sturgeon initially had a somewhat irregular output, frequently suffering from writer's block

Writer's block is a non-medical condition, primarily associated with writing, in which an author is either unable to produce new work or experiences a creative slowdown.

Writer's block has various degrees of severity, from difficulty in coming ...

. He sold his first story, "Heavy Insurance", in 1938 to the McClure Syndicate, which bought much of his early work. It appeared in the ''Milwaukee Journal'' on July 16th. At first he wrote mainly short stories, primarily for genre magazines such as ''Astounding

''Analog Science Fiction and Fact'' is an American science fiction magazine published under various titles since 1930. Originally titled ''Astounding Stories of Super-Science'', the first issue was dated January 1930, published by William Cl ...

'' and ''Unknown

Unknown or The Unknown may refer to:

Film and television Film

* The Unknown (1915 comedy film), ''The Unknown'' (1915 comedy film), Australian silent film

* The Unknown (1915 drama film), ''The Unknown'' (1915 drama film), American silent drama ...

'', but also for general-interest publications such as '' Argosy Magazine''. He used the pen name

A pen name or nom-de-plume is a pseudonym (or, in some cases, a variant form of a real name) adopted by an author and printed on the title page or by-line of their works in place of their real name.

A pen name may be used to make the author's na ...

"E. Waldo Hunter" when two of his stories ran in the same issue of ''Astounding''. A few of his early stories were signed "Theodore H. Sturgeon".

1950s: The boom years

Although the bulk of Sturgeon's short story work dated from the 1940s and '50s, his original novels were all published between 1950 and 1961. Disliking arguments withJohn W. Campbell

John Wood Campbell Jr. (June 8, 1910 – July 11, 1971) was an American science fiction writer and editor. He was editor of ''Astounding Science Fiction'' (later called ''Analog Science Fiction and Fact'') from late 1937 until his death and wa ...

over editorial decisions, Sturgeon only published one story in ''Astounding'' after 1950. He did, however, take very seriously Campbell's enthusiasms for psionics

In American science fiction of the 1950s and '60s, psionics was a proposed discipline that applied principles of engineering (especially electronics) to the study (and employment) of paranormal or psychic phenomena, such as extrasensory perceptio ...

and for L. Ron Hubbard

Lafayette Ronald Hubbard (March 13, 1911 – January 24, 1986) was an American author and the founder of Scientology. A prolific writer of pulp science fiction and fantasy novels in his early career, in 1950 he authored the pseudoscie ...

's Dianetics

Dianetics is a set of pseudoscientific ideas and practices regarding the human mind, which were invented in 1950 by science fiction writer L.Ron Hubbard. Dianetics was originally conceived as a form of psychological treatment, but was reje ...

(even before it became the Church of Scientology

The Church of Scientology is a group of interconnected corporate entities and other organizations devoted to the practice, administration and dissemination of Scientology, which is variously defined as a cult, a business, or a new religiou ...

in 1953). Sturgeon was "audited" by Campbell himself, and according to Alec Nevala-Lee

Alec Nevala-Lee (born May 31, 1980) is an American biographer, novelist, critic, and science fiction writer. He was a Hugo and Locus Award finalist for the group biography ''Astounding: John W. Campbell, Isaac Asimov, Robert A. Heinlein, L. Ron ...

, he became more devoted to it than any other science fiction writer other than A.E. van Vogt. He became a trained auditor and defended the Church for decades.

Sturgeon published the "first stories in science fiction which dealt with homosexuality, ' The World Well Lost' une 1953and 'Affair with a Green Monkey' ay 1957, and sometimes put gay subtext

In any communication, in any medium or format, "subtext" is the underlying or implicit meaning that, while not explicitly stated, is understood by an audience.

The Oxford English Dictionary defines it as "an underlying and often distinct theme ...

in his work, such as the back-rub scene in " Shore Leave", or in his Western story, "Scars".

Carl Sagan

Carl Edward Sagan (; ; November 9, 1934December 20, 1996) was an American astronomer, planetary scientist and science communicator. His best known scientific contribution is his research on the possibility of extraterrestrial life, including e ...

later described "To Here and the Easel" (1954) as "a stunning portrait of personality disassociation as perceived from the inside", and further said that many of Sturgeon's works were among the "rare few science‐fiction novels hat

A hat is a Headgear, head covering which is worn for various reasons, including protection against weather conditions, ceremonial reasons such as university graduation, religious reasons, safety, or as a fashion accessory. Hats which incorpor ...

combine a standard science‐fiction theme with a deep human sensitivity".

According to science fiction writer Samuel R. Delany

Samuel R. "Chip" Delany (, ; born April 1, 1942) is an American writer and literary critic. His work includes fiction (especially science fiction), memoir, criticism, and essays on science fiction, literature, sexual orientation, sexuality, and ...

, a friend of Sturgeon's, Sturgeon was bisexual.

Though not as well known to the general public as contemporaries like Isaac Asimov

Isaac Asimov ( ; – April 6, 1992) was an Russian-born American writer and professor of biochemistry at Boston University. During his lifetime, Asimov was considered one of the "Big Three" science fiction writers, along with Robert A. H ...

or Ray Bradbury

Ray Douglas Bradbury ( ; August 22, 1920June 5, 2012) was an American author and screenwriter. One of the most celebrated 20th-century American writers, he worked in a variety of genres, including fantasy, science fiction, Horror fiction, horr ...

, Sturgeon became well known among readers of mid-20th-century science fiction anthologies. At the height of his popularity in the 1950s he was the most anthologized English-language author alive.

Three Sturgeon stories were adapted for the 1950s NBC radio anthology ''X Minus One

''X Minus One'' is an American half-hour science fiction radio drama series that was broadcast from April 24, 1955, to January 9, 1958, in various timeslots on NBC. Known for high production values in adapting stories from the leading American ...

'': " A Saucer of Loneliness" (broadcast twice), "The Stars Are the Styx" and "Mr. Costello, Hero".

Sturgeon was a member of the all-male literary banqueting club the Trap Door Spiders, which served as the basis of Isaac Asimov

Isaac Asimov ( ; – April 6, 1992) was an Russian-born American writer and professor of biochemistry at Boston University. During his lifetime, Asimov was considered one of the "Big Three" science fiction writers, along with Robert A. H ...

's fictional group of mystery solvers the Black Widowers

The Black Widowers is a fictional men-only dining club created by Isaac Asimov for a series of sixty-six mystery fiction, mystery short story, stories that he started writing in 1971. Most of the stories were first published in ''Ellery Queen's Mys ...

. In 1959, Sturgeon moved to Truro, Massachusetts

Truro is a town in Barnstable County, Massachusetts, United States, comprising two villages: Truro and North Truro. Located slightly more than 100 miles (160 km) by road from Boston, it is a summer vacation community just south of the n ...

where he met and became friendly with a then unknown Kurt Vonnegut, Jr. (Sturgeon was the inspiration for the recurrent character of Kilgore Trout

Kilgore Trout is a fictional character created by author Kurt Vonnegut (1922–2007). Trout is a notably unsuccessful author of paperback science fiction novels.

"Trout" was inspired by the name of the author Theodore Sturgeon (1918–1985), Vo ...

in Vonnegut's novels.)

In 1959, he began to write book reviews for National Review

''National Review'' is an American conservative editorial magazine, focusing on news and commentary pieces on political, social, and cultural affairs. The magazine was founded by William F. Buckley Jr. in 1955. Its editor-in-chief is Rich L ...

, and continued until 1973.

1960s and '70s: Ellery Queen and TV scripts

Sturgeon ghost-wrote oneEllery Queen

Ellery Queen is a pseudonym created in 1928 by the American detective fiction writers Frederic Dannay (1905–1982) and Manfred Bennington Lee (1905–1971). It is also the name of their main fictional detective, a mystery writer in New York City ...

mystery novel, ''The Player on the Other Side'' (Random House, 1963). This novel was praised by critic H. R. F. Keating: " had almost finished writing ''Crime and Mystery: The 100 Best Books'', in which I had included ''The Player on the Other Side'' ... placing the book squarely in the Queen canon"Keating, H. R. F. (1989). ''The Bedside Companion to Crime''. New York: Mysterious Press. when he learned that it had been written by Sturgeon. Similarly, William DeAndrea, author and winner of Mystery Writers of America

Mystery Writers of America (MWA) is a professional organization of mystery and crime writers, based in New York City.

The organization was founded in 1945 by Clayton Rawson, Anthony Boucher, Lawrence Treat, and Brett Halliday.

It presents the E ...

awards, selecting his ten favorite mystery novels for the magazine ''Armchair Detective'', picked ''The Player on the Other Side'' as one of them. He said: "This book changed my life ... and made a raving mystery fan (and therefore ultimately a mystery writer) out of me. ... The book must be 'one of the most skillful pastiches in the history of literature. An amazing piece of work, whomever did it'."

Sturgeon wrote the screenplays for the '' Star Trek: The Original Series'' episodes " Shore Leave" (1966) and " Amok Time" (1967, adapted as a Bantam Books

Bantam Books is an American publishing house owned entirely by parent company Random House, a subsidiary of Penguin Random House; it is an imprint of the Random House Publishing Group. It was formed in 1945 by Walter B. Pitkin Jr., Sidney B. K ...

"Star Trek Fotonovel" in 1978). The latter featured the first appearance of pon farr, the Vulcan mating ritual, the sentence "Live long and prosper" and the Vulcan hand symbol. Sturgeon also wrote several more ''Star Trek

''Star Trek'' is an American science fiction media franchise created by Gene Roddenberry, which began with the Star Trek: The Original Series, series of the same name and became a worldwide Popular culture, pop-culture Cultural influence of ...

'' scripts that were never produced. One of these first introduced the Prime Directive

In the fictional universe of ''Star Trek'', the Prime Directive (also known as "Starfleet General Order 1", and the "non-interference directive") is a guiding principle of Starfleet that prohibits its members from interfering with the natural dev ...

.

Sturgeon also wrote an episode of the Saturday morning show '' Land of the Lost'', " The Pylon Express", in 1975. His 1944 novella '' Killdozer!'' was the inspiration for the 1974 made-for-TV movie, Marvel comic book, and alternative rock band of the same name, as well as becoming the colloquial name for Marvin Heemeyer

Marvin John Heemeyer (October 28, 1951 – June 4, 2004) was an American automobile muffler repair shop owner who demolished numerous buildings with a modified bulldozer in Granby, Colorado, in June 2004. Heemeyer's machine was posthumously n ...

's 2004 bulldozer rage incident.

Later years

Though Sturgeon continued to write through 1983, his work rate dipped noticeably in the later years of his life; a 1971 story collection entitled ''Sturgeon Is Alive and Well...'' addressed Sturgeon's seeming withdrawal from the public eye in a tongue-in-cheek manner. Two of his stories were adapted for the 1980s revival of ''The Twilight Zone

''The Twilight Zone'' is an American media franchise based on the anthology series, anthology television series created by Rod Serling in which characters find themselves dealing with often disturbing or unusual events, an experience described ...

''. One, " A Saucer of Loneliness", was broadcast in 1986 and was dedicated to his memory. Another short story, "Yesterday Was Monday", was the inspiration for ''The Twilight Zone'' episode " A Matter of Minutes".

Sturgeon played guitar and wrote music which he sometimes performed at science fiction convention

Science fiction conventions are gatherings of fans of the speculative fiction subgenre, science fiction. Historically, science fiction conventions had focused primarily on literature, but the purview of many extends to such other avenues of ex ...

s. He lived for several years in Springfield, Oregon

Springfield is a city in Lane County, Oregon, Lane County, Oregon, United States. Located in the Willamette Valley, Southern Willamette Valley, it is within the Eugene-Springfield, OR MSA, Eugene-Springfield metropolitan statistical area. Separ ...

. He died on May 8, 1985, of lung fibrosis, at Sacred Heart General Hospital in the neighboring city of Eugene. He had been a lifelong pipe smoker and his death from lung fibrosis may have been caused by exposure to asbestos

Asbestos ( ) is a group of naturally occurring, Toxicity, toxic, carcinogenic and fibrous silicate minerals. There are six types, all of which are composed of long and thin fibrous Crystal habit, crystals, each fibre (particulate with length su ...

during his Merchant Marine years.

John Clute

John Frederick Clute (born 12 September 1940) is a Canadian-born author and critic specializing in science fiction and fantasy literature who has lived in both England and the United States since 1969. He has been described as "an integral part ...

wrote in ''The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction

''The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction'' (''SFE'') is an English language reference work on science fiction, first published in 1979. It has won the Hugo Award, Hugo, Locus Award, Locus and BSFA Award, British SF Awards. Two print editions appea ...

'': "His influence upon writers like Harlan Ellison

Harlan Jay Ellison (May 27, 1934 – June 28, 2018) was an American writer, known for his prolific and influential work in New Wave science fiction, New Wave speculative fiction and for his outspoken, combative personality. His published wo ...

and Samuel R. Delany

Samuel R. "Chip" Delany (, ; born April 1, 1942) is an American writer and literary critic. His work includes fiction (especially science fiction), memoir, criticism, and essays on science fiction, literature, sexual orientation, sexuality, and ...

was seminal, and in his life and work he was a powerful and generally liberating influence in post-WWII US sf". He won comparatively few genre awards; one was the World Fantasy Award for Life Achievement

The world is the totality of entities, the whole of reality, or everything that exists. The nature of the world has been conceptualized differently in different fields. Some conceptions see the world as unique, while others talk of a "plu ...

from the 1985 World Fantasy Convention.

Sturgeon's Law

In 1957, Sturgeon coined what is now known as '' Sturgeon's Law'': This was originally known as ''Sturgeon's Revelation''; Sturgeon has said that "Sturgeon's Law" was originally However, the former statement is now widely referred to as Sturgeon's Law. He is also known for his dedication to a credo of critical thinking that challenged all normative assumptions: "Ask the next question." This was the subject of an essay published in Cavalier Magazine in June 1967. He represented this credo by the symbol of a Q with an arrow through it, an example of which he wore around his neck and used as part of his signature in the last 15 years of his life.Personal life

;Wives and partners Sturgeon was married three times, had two long-term committed relationships outside of marriage, divorced once, and fathered a total of seven children. His first wife was Dorothe Fillingame (married 1940, divorced 1945) with whom he had two daughters. He was married to singer Mary Mair from 1949 until an annulment in 1951. In 1953, he wed Marion McGahan with whom he had two sons and two daughters. In 1969, he began living with Wina Golden, a journalist, with whom he had a son. Finally, his last long-term committed relationship was with writer and educator Jayne Englehart Tannehill, with whom he remained until the time of his death. She joined Sturgeon at book signings for his collection ''Maturity'', and signed as "Jayne Sturgeon". Englehart had her own biological son prior to her partnership with Sturgeon, to whom Sturgeon became like a stepfather. ;Relationship with Kurt Vonnegut In 1965,Kurt Vonnegut

Kurt Vonnegut ( ; November 11, 1922 – April 11, 2007) was an American author known for his Satire, satirical and darkly humorous novels. His published work includes fourteen novels, three short-story collections, five plays, and five nonfict ...

devised the name of his fictional science-fiction writer Kilgore Trout

Kilgore Trout is a fictional character created by author Kurt Vonnegut (1922–2007). Trout is a notably unsuccessful author of paperback science fiction novels.

"Trout" was inspired by the name of the author Theodore Sturgeon (1918–1985), Vo ...

as an obscure reference to Sturgeon's name. The two writers had become friends when Sturgeon moved to Truro, Massachusetts

Truro is a town in Barnstable County, Massachusetts, United States, comprising two villages: Truro and North Truro. Located slightly more than 100 miles (160 km) by road from Boston, it is a summer vacation community just south of the n ...

in 1957. Vonnegut described Trout as a notably unsuccessful writer, prolifically publishing hackwork only in pulp and pornographic magazines. Since the characterization was unflattering, it was not until after Sturgeon's death that Vonnegut explicitly acknowledged the connection; he stated in a 1987 interview that "Yeah, it said so in his obituary in ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''NYT'') is an American daily newspaper based in New York City. ''The New York Times'' covers domestic, national, and international news, and publishes opinion pieces, investigative reports, and reviews. As one of ...

''. I was delighted that it said in the middle of it that he was the inspiration for the Kurt Vonnegut character of Kilgore Trout." In 2000, Vonnegut wrote an admiring introduction to Volume VII of ''The Complete Stories of Theodore Sturgeon''. Sturgeon, Theodore (2000), ''A Saucer of Loneliness: Volume VII: The Complete Stories of Theodore Sturgeon''; Paul Williams (Editor), Kurt Vonnegut Jr. (Foreword); North Atlantic Books.

Works

Novels

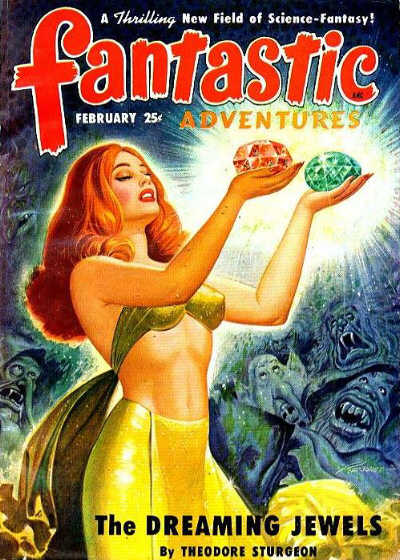

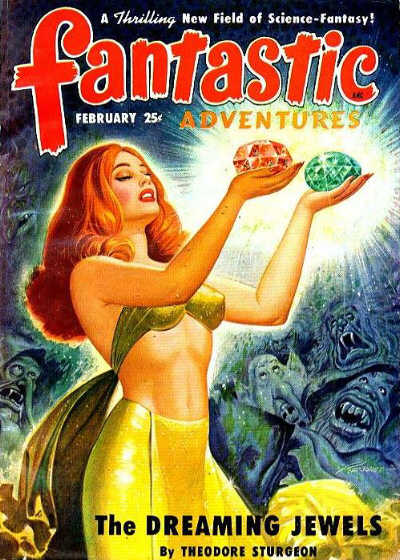

* '' The Dreaming Jewels'' (1950) Also published as ''The Synthetic Man'' * ''More Than Human

''More Than Human'' is a 1953 science fiction fix-up novel by American writer Theodore Sturgeon. It is a revision and expansion of his 1952 novella '' Baby Is Three'', which is bracketed by two additional parts written for the novel, "The F ...

'' (1953) Fix-up

A fix-up (or fixup) is a novel created from several short fiction stories that may or may not have been initially related or previously published. The stories may be edited for consistency, and sometimes new connecting material, such as a frame ...

of three linked novellas, the first and third written around '' Baby Is Three'' (Galaxy Science Fiction, October 1952)

* '' The Cosmic Rape'' (1958) A shorter version was published as ''To Marry Medusa''

* '' Venus Plus X'' (1960)

* '' Some of Your Blood'' (1961)

* '' Godbody'' (1986) Published posthumously

Novelizations

Sturgeon, under his own name, was hired to write novelizations of the following movies based on their scripts (links go to articles about the movies): * '' The King and Four Queens'' (1956) * ''Voyage to the Bottom of the Sea

''Voyage to the Bottom of the Sea'' is a 1961 American science fiction disaster film, produced and directed by Irwin Allen, and starring Walter Pidgeon and Robert Sterling. The supporting cast includes Peter Lorre, Joan Fontaine, Barbara Eden ...

'' (1961) The book is described in '' Voyage to the Bottom of the Sea (novel)''.

* '' The Rare Breed'' (1966)

Pseudonymous novels

* ''I, Libertine

''I, Libertine'' is a historical novel that began as a practical joke by Jean Shepherd, a late-night radio raconteur who aimed to lampoon the process of determining best-selling books. After generating substantial attention for a novel that di ...

'' (1956): Historical novel created as a for-hire hoax. Credited to "Frederick R. Ewing", written from a premise by Jean Shepherd

Jean Parker "Shep" Shepherd Jr. (July 26, 1921 – October 16, 1999) was an American storytelling, storyteller, humorist, radio and TV personality, writer, and actor. With a career that spanned decades, Shepherd is known for the film ''A Christm ...

.

* ''The Player on The Other Side'' (1963): Mystery novel credited to Ellery Queen

Ellery Queen is a pseudonym created in 1928 by the American detective fiction writers Frederic Dannay (1905–1982) and Manfred Bennington Lee (1905–1971). It is also the name of their main fictional detective, a mystery writer in New York City ...

and ghost-written with Queen's assistance and supervision.

Short stories

Sturgeon published numerous short story collections during his lifetime, many drawing on his most prolific writing years of the 1940s and 1950s. Note that some reprints of these titles (especially paperback editions) may cut one or two stories from the line-up. Statistics herein refer to the original editions only.Collections published during Sturgeon's lifetime

The following table includes sixteen volumes (one of them collectingwestern

Western may refer to:

Places

*Western, Nebraska, a village in the US

*Western, New York, a town in the US

*Western Creek, Tasmania, a locality in Australia

*Western Junction, Tasmania, a locality in Australia

*Western world, countries that id ...

stories). These are considered "original" collections of Sturgeon material, in that they compiled previously uncollected stories. However, some volumes did contain a few reprinted stories: this list includes books that collected only previously uncollected material, as well as those volumes that collected ''mostly'' new material, but also contained up to three stories (representing no more than half the book) that were previously published in a Sturgeon collection.

The following six collections consisted entirely of reprints of previously collected material:

Complete short stories

North Atlantic Books

North Atlantic Books is a non-profit, independent publisher based in Berkeley, California, United States. Distributed by Penguin Random House Publisher Services, North Atlantic Books is a mission-driven social justice-oriented publisher. Founded ...

released the chronologically assembled ''The Complete Short Stories of Theodore Sturgeon'', edited by Paul Williams. The series consisted of 13 volumes published between 1994 and 2010. Introductions were provided by Harlan Ellison

Harlan Jay Ellison (May 27, 1934 – June 28, 2018) was an American writer, known for his prolific and influential work in New Wave science fiction, New Wave speculative fiction and for his outspoken, combative personality. His published wo ...

, Samuel R. Delany

Samuel R. "Chip" Delany (, ; born April 1, 1942) is an American writer and literary critic. His work includes fiction (especially science fiction), memoir, criticism, and essays on science fiction, literature, sexual orientation, sexuality, and ...

, Kurt Vonnegut

Kurt Vonnegut ( ; November 11, 1922 – April 11, 2007) was an American author known for his Satire, satirical and darkly humorous novels. His published work includes fourteen novels, three short-story collections, five plays, and five nonfict ...

, Gene Wolfe

Gene Rodman Wolfe (May 7, 1931 – April 14, 2019) was an American science fiction and fantasy writer. He was noted for his dense, allusive prose as well as the strong influence of his Catholic faith. He was a prolific short story writer and no ...

, Connie Willis, Jonathan Lethem

Jonathan Allen Lethem (; born February 19, 1964) is an American novelist, essayist, and short story writer. His Debut novel, first novel, ''Gun, with Occasional Music'', a genre work that mixed elements of science fiction and detective fiction, ...

, and others. Extensive story notes were provided by Paul Williams and, in the last two volumes, Sturgeon's daughter Noël.

* Volume I – ''The Ultimate Egoist'' (1937 to 1940)

* Volume II – ''Microcosmic God'' (1940 to 1941)

* Volume III – ''Killdozer'' (1941 to 1946)

* Volume IV – ''Thunder and Roses'' (1946 to 1948)

* Volume V – ''The Perfect Host'' (1948 to 1950)

* Volume VI – ''Baby is Three'' (1950 to 1952)

* Volume VII – ''A Saucer of Loneliness'' (1953)

* Volume VIII – ''Bright Segment'' (1953 to 1955, as well as two "lost" stories from 1946)

* Volume IX – ''And Now the News...'' (1955 to 1957)

* Volume X – ''The Man Who Lost the Sea'' (1957 to 1960)

* Volume XI – ''The Nail and the Oracle'' (1961 to 1969)

* Volume XII – ''Slow Sculpture'' (1970 to 1972, plus one 1954 novella and one unpublished story)

* Volume XIII – ''Case and The Dreamer'' (1972 to 1983, plus one 1960 story and three unpublished stories)

Representative short stories

Sturgeon was best known for his short stories and novellas. The best-known include: * "Ether Breather" (September 1939, his first published science-fiction story) * "Derm Fool" (March 1940) * " It" (August 1940) * " Shottle Bop" (February 1941) * "Microcosmic God

"Microcosmic God" is a science fiction novelette by American writer Theodore Sturgeon. Originally published in April 1941 in the magazine ''Astounding Science Fiction'', it was recognized as one of the best science fiction short stories publish ...

" (April 1941)

* "Yesterday Was Monday" (1941)

* " Killdozer!" (November, 1944)

* "Maturity" (February, 1947)

* "Bianca's Hands" (May, 1947)

* "Thunder and Roses" (November 1947)

* "The Perfect Host" (November 1948)

* "It Wasn't Syzygy" (January 1948)

* "Minority Report" (June 1949, no connection to the 2002 movie, which was based on a later story by Philip K. Dick)

* "One Foot and the Grave" (September 1949)

* " Baby Is Three" (October 1952)

* " A Saucer of Loneliness" (February 1953)

* " The World Well Lost" (June 1953)

* "Mr. Costello, Hero" (December 1953)

* "The idget The adget and Boff" (1955)

* "The Skills of Xanadu" (July 1956)

* "The Other Man" (September 1956)

* "And Now The News" (December 1956)

* "The Girl Had Guts" (January 1957)

* " The Man Who Lost the Sea" (October 1959)

* "Need" (1960)

* "How to Forget Baseball" (''Sports Illustrated

''Sports Illustrated'' (''SI'') is an American sports magazine first published in August 1954. Founded by Stuart Scheftel, it was the first magazine with a circulation of over one million to win the National Magazine Award for General Excellen ...

'', December 1964)

* "The Nail and the Oracle" (''Playboy

''Playboy'' (stylized in all caps) is an American men's Lifestyle journalism, lifestyle and entertainment magazine, available both online and in print. It was founded in Chicago in 1953 by Hugh Hefner and his associates, funded in part by a $ ...

'', October 1964)

* " If All Men Were Brothers, Would You Let One Marry Your Sister?" (1967, ''Dangerous Visions

''Dangerous Visions'' is an anthology of science fiction short stories edited by American writer Harlan Ellison and illustrated by Leo and Diane Dillon. It was published in 1967 and contained 33 stories, none of which had been previously publishe ...

'' anthology edited by Harlan Ellison

Harlan Jay Ellison (May 27, 1934 – June 28, 2018) was an American writer, known for his prolific and influential work in New Wave science fiction, New Wave speculative fiction and for his outspoken, combative personality. His published wo ...

)—Nebula Award

The Nebula Awards annually recognize the best works of science fiction or fantasy published in the United States. The awards are organized and awarded by the Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers Association (SFWA), a nonprofit association of pr ...

1967 Nominee Novella

* "The Man Who Learned Loving"—Nebula Award

The Nebula Awards annually recognize the best works of science fiction or fantasy published in the United States. The awards are organized and awarded by the Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers Association (SFWA), a nonprofit association of pr ...

1969 Nominee Short Story

* " Slow Sculpture" (''Galaxy

A galaxy is a Physical system, system of stars, stellar remnants, interstellar medium, interstellar gas, cosmic dust, dust, and dark matter bound together by gravity. The word is derived from the Ancient Greek, Greek ' (), literally 'milky', ...

'', February 1970) — winner of a Hugo Award

The Hugo Award is an annual literary award for the best science fiction or fantasy works and achievements of the previous year, given at the World Science Fiction Convention (Worldcon) and chosen by its members. The award is administered by th ...

and a Nebula Award

The Nebula Awards annually recognize the best works of science fiction or fantasy published in the United States. The awards are organized and awarded by the Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers Association (SFWA), a nonprofit association of pr ...

* "Occam's Scalpel" (August, 1971, with an introduction by Terry Carr)

* "Vengeance Is." (1980, ''Dark Forces'' anthology edited by Kirby McCauley)

Autobiography

* ''Argyll: A Memoir'' (pamphlet, Sturgeon Project, 1993), an autobiographical sketch about Sturgeon's relationship with his stepfather. Introduction by his editor Paul Williams. Afterword bySamuel R. Delany

Samuel R. "Chip" Delany (, ; born April 1, 1942) is an American writer and literary critic. His work includes fiction (especially science fiction), memoir, criticism, and essays on science fiction, literature, sexual orientation, sexuality, and ...

. Cover art by Donna Nassar. The memoir, written for his psychotherapist, has many suggestions about his life, starting from his family's move from Staten Island to Philadelphia when his stepfather got a job at Drexel University and Sturgeon and his brother were still in the local public school to their attempts to catch poison ivy to delay the move—"Then we moved to Philadelphia, a little apartment on 34 Street with a sort of sun room, which was Argyll's study and had a single couch which was his and Mother's bed, and a kind of living room with a kitchenette built into one wall, where we slept on the floor on mattresses."— and his father's treatment of a puppy he couldn't discipline—"... he used to whip her with a wire after rubbing her nose in it—so he got rid of her" (p. 14). These go on to include Sturgeon's first gay experiences in his 14th year—"So 0-year-oldBert blew me practically continuously from Friday evening until dinner time Sunday; we kept score and I came 14 times. Sweet are the uses of respectability. My God! It never occurred to me until this minute that Dr. Taft was probably the one—the only one, as sole mentor, who could possibly have insured Argyll's total ignorance!" (p. 52); and in his long letter to his mother and Argyll, included in the same volume, Sturgeon harshly critiques his first novel, '' The Dreaming Jewels'': "My use of one detested Argyll would have been fine, but one wasn't enough; there had to be two, and as a result the balance of the work was destroyed and its literary worth was lost in vengeful polemic" (p. 62).

See also

*Theodore Sturgeon Award

The Theodore Sturgeon Memorial Award is an annual literary award presented by the Theodore Sturgeon Literary Trust and the Center for the Study of Science Fiction at the University of Kansas to the author of the best short science fiction story ...

* Golden Age of Science Fiction

The Golden Age of Science Fiction, often identified in the United States as the years 1938–1946, was a period in which a number of foundational works of science fiction appeared in American genre magazines. Exemplars include the '' Foundation' ...

References

Citations

Cited sources

* An overview of Sturgeon's work to 1965. * *Further reading

*External links

The Theodore Sturgeon Page

- an informative and comprehensive fan site

The Theodore Sturgeon Literary Trust

– owners of Sturgeon copyrights, information on Sturgeon publications * Theodore Sturgeon Papers

MS 303

an

MS 254

housed at th

Kenneth Spencer Research Library

University of Kansas * * * * *

at Free Speculative Fiction Online

* ttp://efanzines.com/SFC/SteamEngineTime/SET13.pdf The Work of Theodore Sturgeon– lengthy biographical and critical study of Sturgeon {{DEFAULTSORT:Sturgeon, Theodore 1918 births 1985 deaths American horror writers American science fiction writers American speculative fiction editors Hugo Award–winning writers Nebula Award winners People from Springfield, Oregon Writers from Staten Island American science fiction critics Science Fiction Hall of Fame inductees World Fantasy Award–winning writers 20th-century American novelists American male novelists American atheists American Scientologists Journalists from New York City 20th-century American male writers Novelists from New York (state) American male non-fiction writers American weird fiction writers