Taylor V. Beckham on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Taylor v. Beckham'', 178 U.S. 548 (1900), was a case heard before the

When the official tally was announced, Taylor had won by a vote of 193,714 to 191,331. Though the Board of Elections was thought to be controlled by Goebel allies, it voted 2–1 to certify the announced vote tally.Klotter, "Goebel Assassination", p. 377 The board's majority opinion claimed that they did not have any judicial power and were thus unable to hear proof or swear witnesses.Tapp, p. 444 Taylor was inaugurated on December 12, 1899. Goebel announced his decision to contest the board's decision to the General Assembly. The Assembly appointed a committee to investigate the allegations contained in the challenges.Harrison in ''A New History of Kentucky'', p. 271 The members of the committee were drawn at random, though the drawing was likely rigged – only one Republican joined ten Democrats on the committee. (Chance dictated that the committee should have contained four or five Republicans.)Tapp, p. 445 Among the rules the General Assembly adopted for the contest committee were: that the committee report at the pleasure of the General Assembly, that debate be limited once the findings were presented, and that the report be voted on in a joint session of the Assembly.Hughes, p. 174 The rules further provided that the speaker of the House preside over the joint session instead of the lieutenant governor, as was customary. The Republican minority fought the provisions, but the Democratic majority passed them despite the opposition.

Republicans around the state expected the committee to recommend disqualification of enough ballots to make Goebel governor. Armed men from heavily Republican eastern Kentucky filled the capital.Tapp, p. 446 On the morning of January 30, 1900, as Goebel and two friends walked toward the capitol building, shots were fired, and Goebel fell wounded. After being denied entrance to the state capitol by armed men, the contest committee met in Frankfort's

When the official tally was announced, Taylor had won by a vote of 193,714 to 191,331. Though the Board of Elections was thought to be controlled by Goebel allies, it voted 2–1 to certify the announced vote tally.Klotter, "Goebel Assassination", p. 377 The board's majority opinion claimed that they did not have any judicial power and were thus unable to hear proof or swear witnesses.Tapp, p. 444 Taylor was inaugurated on December 12, 1899. Goebel announced his decision to contest the board's decision to the General Assembly. The Assembly appointed a committee to investigate the allegations contained in the challenges.Harrison in ''A New History of Kentucky'', p. 271 The members of the committee were drawn at random, though the drawing was likely rigged – only one Republican joined ten Democrats on the committee. (Chance dictated that the committee should have contained four or five Republicans.)Tapp, p. 445 Among the rules the General Assembly adopted for the contest committee were: that the committee report at the pleasure of the General Assembly, that debate be limited once the findings were presented, and that the report be voted on in a joint session of the Assembly.Hughes, p. 174 The rules further provided that the speaker of the House preside over the joint session instead of the lieutenant governor, as was customary. The Republican minority fought the provisions, but the Democratic majority passed them despite the opposition.

Republicans around the state expected the committee to recommend disqualification of enough ballots to make Goebel governor. Armed men from heavily Republican eastern Kentucky filled the capital.Tapp, p. 446 On the morning of January 30, 1900, as Goebel and two friends walked toward the capitol building, shots were fired, and Goebel fell wounded. After being denied entrance to the state capitol by armed men, the contest committee met in Frankfort's

Taft's ruling had no bearing on the cases of Governor Taylor and Lieutenant Governor Marshall except to spell out a means for them to take their cases to the federal courts, if necessary. On the same day that Taft's ruling was issued, Taylor filed suit in

Taft's ruling had no bearing on the cases of Governor Taylor and Lieutenant Governor Marshall except to spell out a means for them to take their cases to the federal courts, if necessary. On the same day that Taft's ruling was issued, Taylor filed suit in

Chief Justice

Chief Justice

Supreme Court of the United States

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all U.S. federal court cases, and over state court cases that involve a point ...

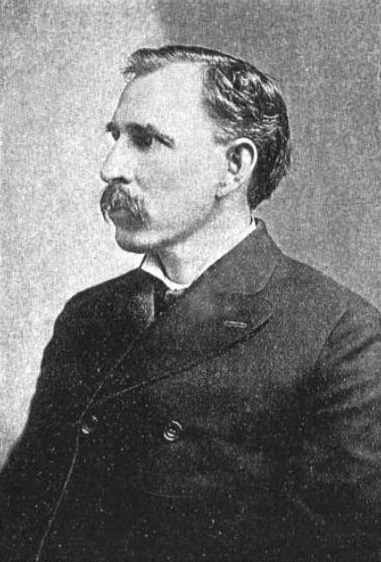

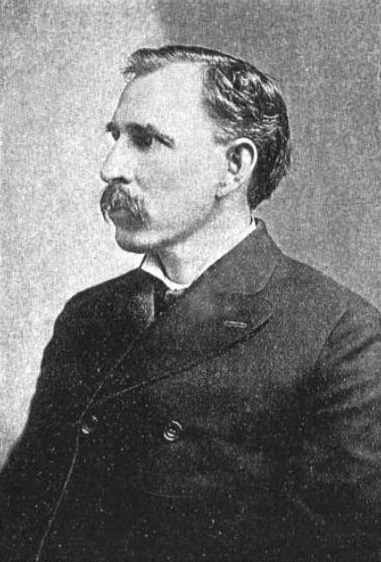

on April 30 and May 1, 1900, to decide the outcome of the disputed Kentucky gubernatorial election of 1899. The litigants were Republican

Republican can refer to:

Political ideology

* An advocate of a republic, a type of government that is not a monarchy or dictatorship, and is usually associated with the rule of law.

** Republicanism, the ideology in support of republics or again ...

gubernatorial

A governor is an administrative leader and head of a polity or political region, ranking under the head of state and in some cases, such as governors-general, as the head of state's official representative. Depending on the type of political r ...

candidate William S. Taylor and Democratic

Democrat, Democrats, or Democratic may refer to:

Politics

*A proponent of democracy, or democratic government; a form of government involving rule by the people.

*A member of a Democratic Party:

**Democratic Party (United States) (D)

**Democratic ...

lieutenant gubernatorial candidate J. C. W. Beckham

John Crepps Wickliffe Beckham (August 5, 1869 – January 9, 1940) was an American attorney serving as the 35th Governor of Kentucky and a United States Senator from Kentucky. He was the state's first popularly-elected senator after the p ...

. In the November 7, 1899, election, Taylor received 193,714 votes to Democrat William Goebel

William Justus Goebel (January 4, 1856 – February 3, 1900) was an American Democratic politician who served as the 34th governor of Kentucky for four days in 1900, having been sworn in on his deathbed a day after being shot by an assassin. G ...

's 191,331. This result was certified by a 2–1 decision of the state's Board of Elections. Goebel challenged the election results on the basis of alleged voting irregularities

Voting is a method by which a group, such as a meeting or an electorate, can engage for the purpose of making a collective decision or expressing an opinion usually following discussions, debates or election campaigns. Democracies elect holder ...

, and the Democrat-controlled Kentucky General Assembly

The Kentucky General Assembly, also called the Kentucky Legislature, is the state legislature (United States), state legislature of the U.S. state of Kentucky. It comprises the Kentucky Senate and the Kentucky House of Representatives.

The Gene ...

formed a committee to investigate Goebel's claims. Goebel was shot on January 30, 1900, one day before the General Assembly approved the committee's report declaring enough Taylor votes invalid to swing the election to Goebel. As he lay dying of his wounds, Goebel was sworn into office on January 31, 1900. He died on February 3, 1900, and Beckham ascended to the governorship.

Claiming the General Assembly's decision was invalid, Taylor sued to prevent Beckham from exercising the authority of the governor's office. Beckham countersued Taylor for possession of the state capitol

This is a list of state and territorial capitols in the United States, the building or complex of buildings from which the government of each U.S. state, the District of Columbia and the organized territories of the United States, exercise its ...

and governor's mansion. The suits were consolidated and heard in Jefferson County Jefferson County may refer to one of several counties or parishes in the United States, all of which are named directly or indirectly after Thomas Jefferson:

*Jefferson County, Alabama

*Jefferson County, Arkansas

*Jefferson County, Colorado

**Jeffe ...

circuit court, which claimed it had no authority to interfere with the method of deciding contested elections prescribed by the state constitution, an outcome that favored Beckham. The Kentucky Court of Appeals

The Kentucky Court of Appeals is the lower of Kentucky's two appellate courts, under the Kentucky Supreme Court. Prior to a 1975 amendment to the Kentucky Constitution the Kentucky Court of Appeals was the only appellate court in Kentucky.

The ...

upheld the circuit court's decision on appeal and rejected Taylor's claim that he had been deprived of property without due process

Due process of law is application by state of all legal rules and principles pertaining to the case so all legal rights that are owed to the person are respected. Due process balances the power of law of the land and protects the individual pe ...

by stating that an elective office was not property and thus not protected by the Fourteenth Amendment.

The injection of Taylor's claim under the Fourteenth Amendment gave him grounds to appeal the decision to the U.S. Supreme Court. In a majority opinion

In law, a majority opinion is a judicial opinion agreed to by more than half of the members of a court. A majority opinion sets forth the decision of the court and an explanation of the rationale behind the court's decision.

Not all cases hav ...

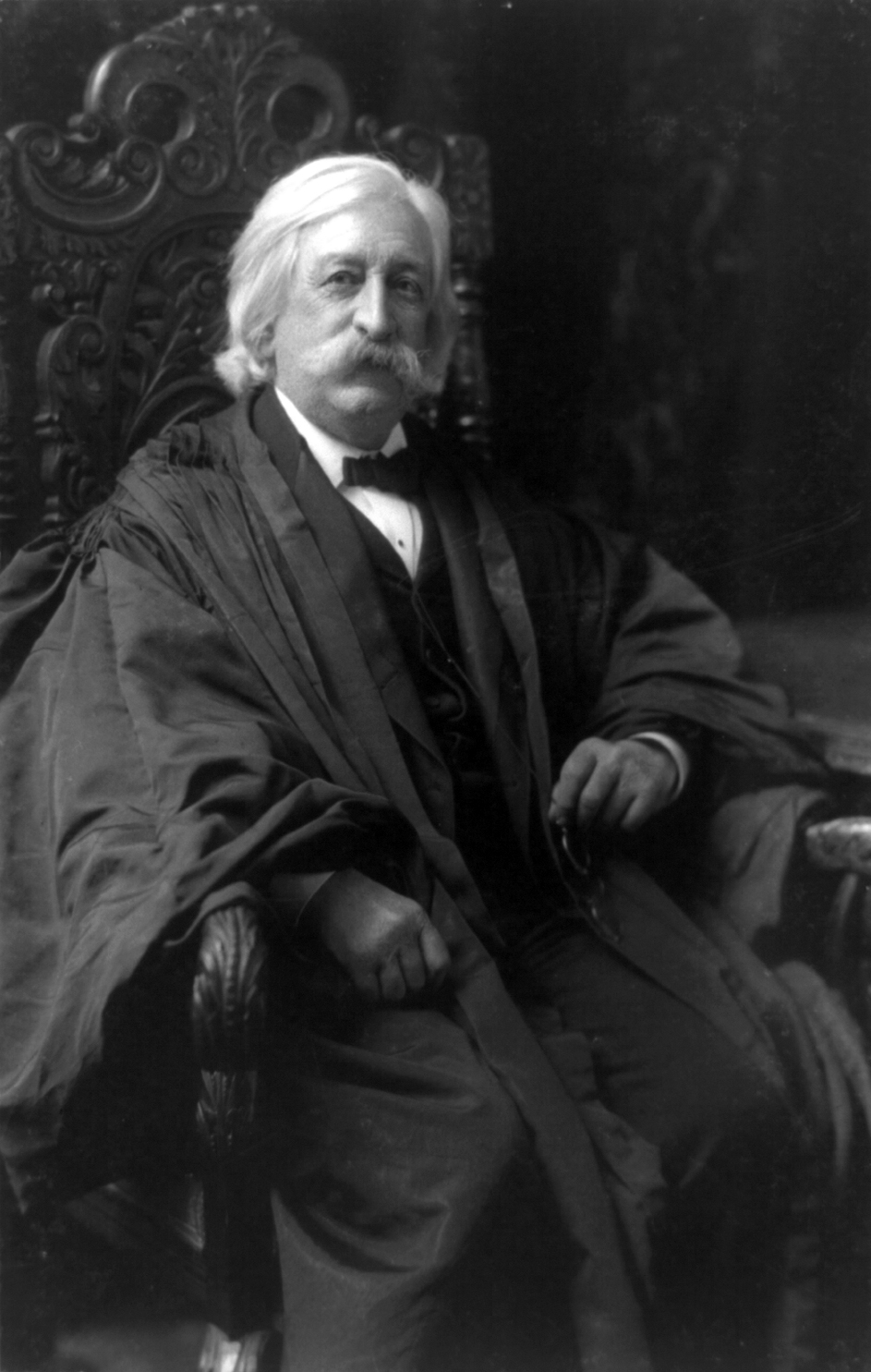

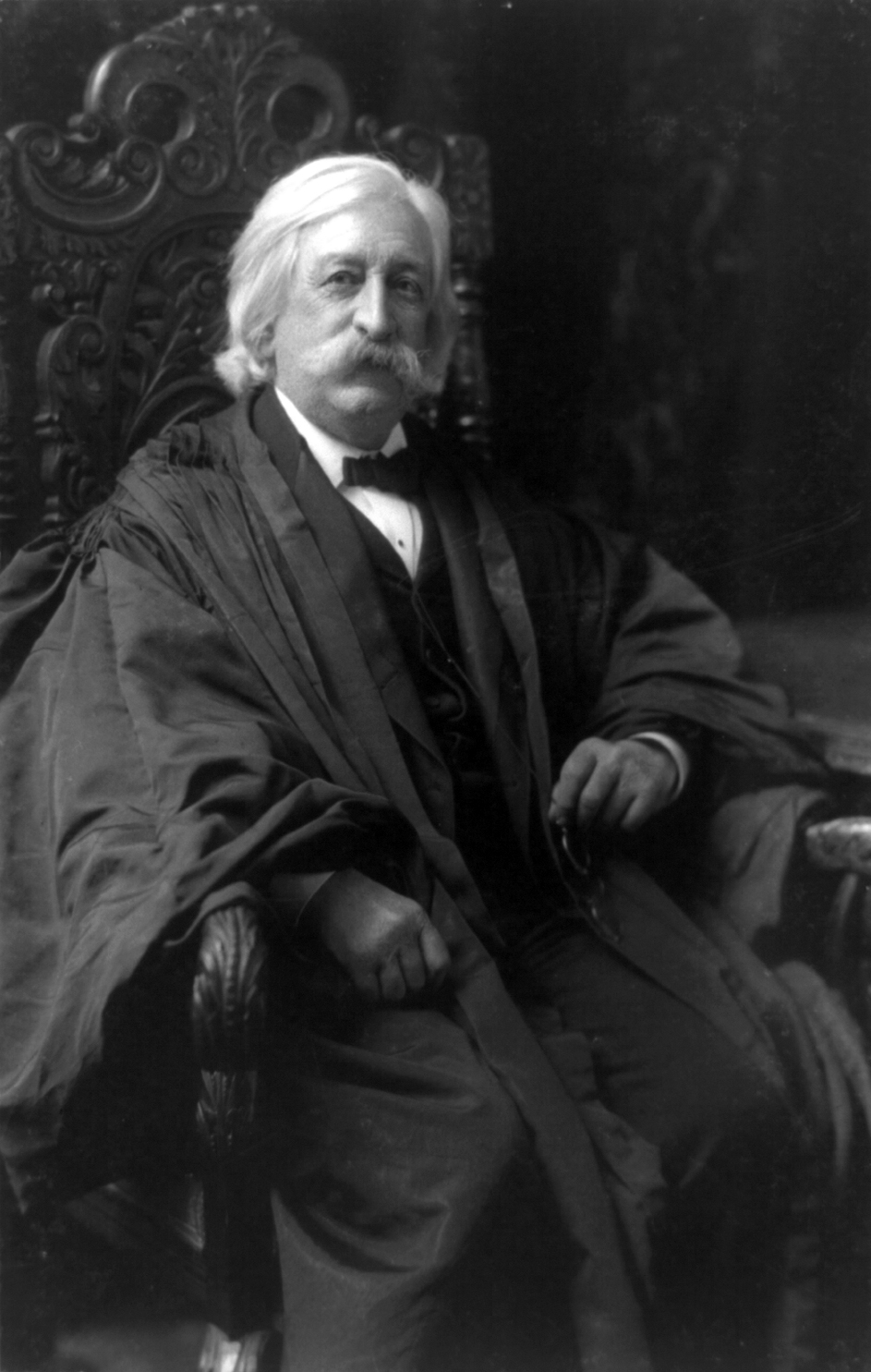

delivered by Chief Justice Melville Fuller

Melville Weston Fuller (February 11, 1833 – July 4, 1910) was an American politician, attorney, and jurist who served as the eighth chief justice of the United States from 1888 until his death in 1910. Staunch conservatism marked his ...

, the Supreme Court also rejected Taylor's claim to loss of property without due process and thus refused to intervene on Taylor's behalf, claiming that no federal issues were in question and the court lacked jurisdiction. Justices Gray

Grey (more common in British English) or gray (more common in American English) is an intermediate color between black and white. It is a neutral or achromatic color, meaning literally that it is "without color", because it can be composed ...

, White

White is the lightness, lightest color and is achromatic (having no hue). It is the color of objects such as snow, chalk, and milk, and is the opposite of black. White objects fully diffuse reflection, reflect and scattering, scatter all the ...

, Shiras Shiras may refer to:

* George Shiras Jr. (1832–1924), Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States

* George Shiras III (1859–1942), U.S. Representative from the state of Pennsylvania

*Leif Shiras (born 1959), American tennis play ...

, and Peckham

Peckham () is a district in southeast London, within the London Borough of Southwark. It is south-east of Charing Cross. At the 2001 Census the Peckham ward had a population of 14,720.

History

"Peckham" is a Saxon place name meaning the vill ...

concurred with the majority opinion. Justice Joseph McKenna

Joseph McKenna (August 10, 1843 – November 21, 1926) was an American politician who served in all three branches of the U.S. federal government, as a member of the U.S. House of Representatives, as U.S. Attorney General and as an Associate Ju ...

concurred with the decision to dismiss, but expressed reservations about the determination that an elected office was not property. Justice David J. Brewer

David Josiah Brewer (June 20, 1837 – March 28, 1910) was an American jurist who served as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1890 to 1910. An appointee of President Benjamin Harrison, he supported states' rig ...

, joined by Justice Henry B. Brown

Henry Billings Brown (March 2, 1836 – September 4, 1913) was an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1891 to 1906.

Although a respected lawyer and U.S. District Judge before ascending to the high court, Brown ...

, contended that the Supreme Court did have jurisdiction, but concurred with the result in favor of Beckham. Kentuckian

Kentucky ( , ), officially the Commonwealth of Kentucky, is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States and one of the states of the Upper South. It borders Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio to the north; West Virginia and Virginia t ...

John Marshall Harlan

John Marshall Harlan (June 1, 1833 – October 14, 1911) was an American lawyer and politician who served as an associate justice of the U.S. Supreme Court from 1877 until his death in 1911. He is often called "The Great Dissenter" due to his ...

authored the lone dissent from the majority opinion, claiming that the court did have jurisdiction and should have found in favor of Taylor based on his claim of loss of property without due process. He further argued that elective office fell under the definition of "liberty" as used in the Fourteenth Amendment and was protected by due process.

Background

History

In 1898, theKentucky General Assembly

The Kentucky General Assembly, also called the Kentucky Legislature, is the state legislature (United States), state legislature of the U.S. state of Kentucky. It comprises the Kentucky Senate and the Kentucky House of Representatives.

The Gene ...

enacted a law which created a Board of Election Commissioners, appointed by the General Assembly, who were responsible for choosing election commissioners in all of Kentucky's counties.Kleber, "Goebel Election Law", p. 378 The board was empowered to examine election returns and certify the results. The power to decide the outcome of disputed elections remained with the General Assembly under Section 153 of the state constitution.Kentucky Constitution, Section 153 The law was commonly referred to as the Goebel Election Law, a reference to its sponsor, President Pro Tempore of the Kentucky Senate

President Pro Tempore of the Kentucky Senate was the title of highest-ranking member of the Kentucky Senate prior to enactment of a 1992 amendment to the Constitution of Kentucky.

Prior to the 1992 amendment of Section 83 of the Constitution of Ke ...

William Goebel

William Justus Goebel (January 4, 1856 – February 3, 1900) was an American Democratic politician who served as the 34th governor of Kentucky for four days in 1900, having been sworn in on his deathbed a day after being shot by an assassin. G ...

. Because the General Assembly was heavily Democratic

Democrat, Democrats, or Democratic may refer to:

Politics

*A proponent of democracy, or democratic government; a form of government involving rule by the people.

*A member of a Democratic Party:

**Democratic Party (United States) (D)

**Democratic ...

and Goebel was considered a likely Democratic aspirant for the governorship

A governor is an administrative leader and head of a polity or political region, ranking under the head of state and in some cases, such as governors-general, as the head of state's official representative. Depending on the type of political r ...

in the 1899 election, the law was attacked as blatantly partisan and self-serving.Harrison in ''A New History of Kentucky'', p. 270 Republicans organized a test case

In software engineering, a test case is a specification of the inputs, execution conditions, testing procedure, and expected results that define a single test to be executed to achieve a particular software testing objective, such as to exercise ...

against the law, but the Kentucky Court of Appeals

The Kentucky Court of Appeals is the lower of Kentucky's two appellate courts, under the Kentucky Supreme Court. Prior to a 1975 amendment to the Kentucky Constitution the Kentucky Court of Appeals was the only appellate court in Kentucky.

The ...

upheld it as constitutional.Hughes, p. 8

Goebel secured the Democratic nomination for governor at a contentious nominating convention.Kleber, "Music Hall Convention", pp. 666–667 Despite the nominations of two minor party candidates – including that of former governor John Y. Brown by a dissident faction of Democrats – the race centered on Goebel and his Republican

Republican can refer to:

Political ideology

* An advocate of a republic, a type of government that is not a monarchy or dictatorship, and is usually associated with the rule of law.

** Republicanism, the ideology in support of republics or again ...

opponent, Attorney General

In most common law jurisdictions, the attorney general or attorney-general (sometimes abbreviated AG or Atty.-Gen) is the main legal advisor to the government. The plural is attorneys general.

In some jurisdictions, attorneys general also have exec ...

William S. Taylor.Tapp, p. 439 The results of the election were too close to call for several days. Before the official results could be announced, charges of voting irregularities began. In Nelson County, 1,200 ballots listed the Republican candidate as "W. P. Taylor" instead of "W. S. Taylor"; Democrats claimed these votes should be invalidated.Tapp, p. 441 In Knox

Knox may refer to:

Places United States

* Fort Knox, a United States Army post in Kentucky

** United States Bullion Depository, a high security storage facility commonly called Fort Knox

* Fort Knox (Maine), a fort located on the Penobscot River i ...

and Johnson

Johnson is a surname of Anglo-Norman origin meaning "Son of John". It is the second most common in the United States and 154th most common in the world. As a common family name in Scotland, Johnson is occasionally a variation of ''Johnston'', a ...

counties, voters complained of "thin tissue ballots" that allowed the voter's choices to be seen through them. In the city of Louisville

Louisville ( , , ) is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Kentucky and the 28th most-populous city in the United States. Louisville is the historical seat and, since 2003, the nominal seat of Jefferson County, on the Indiana border. ...

, Democrats charged that the militia had intimidated voters there and that the entire city's vote should be invalidated.

When the official tally was announced, Taylor had won by a vote of 193,714 to 191,331. Though the Board of Elections was thought to be controlled by Goebel allies, it voted 2–1 to certify the announced vote tally.Klotter, "Goebel Assassination", p. 377 The board's majority opinion claimed that they did not have any judicial power and were thus unable to hear proof or swear witnesses.Tapp, p. 444 Taylor was inaugurated on December 12, 1899. Goebel announced his decision to contest the board's decision to the General Assembly. The Assembly appointed a committee to investigate the allegations contained in the challenges.Harrison in ''A New History of Kentucky'', p. 271 The members of the committee were drawn at random, though the drawing was likely rigged – only one Republican joined ten Democrats on the committee. (Chance dictated that the committee should have contained four or five Republicans.)Tapp, p. 445 Among the rules the General Assembly adopted for the contest committee were: that the committee report at the pleasure of the General Assembly, that debate be limited once the findings were presented, and that the report be voted on in a joint session of the Assembly.Hughes, p. 174 The rules further provided that the speaker of the House preside over the joint session instead of the lieutenant governor, as was customary. The Republican minority fought the provisions, but the Democratic majority passed them despite the opposition.

Republicans around the state expected the committee to recommend disqualification of enough ballots to make Goebel governor. Armed men from heavily Republican eastern Kentucky filled the capital.Tapp, p. 446 On the morning of January 30, 1900, as Goebel and two friends walked toward the capitol building, shots were fired, and Goebel fell wounded. After being denied entrance to the state capitol by armed men, the contest committee met in Frankfort's

When the official tally was announced, Taylor had won by a vote of 193,714 to 191,331. Though the Board of Elections was thought to be controlled by Goebel allies, it voted 2–1 to certify the announced vote tally.Klotter, "Goebel Assassination", p. 377 The board's majority opinion claimed that they did not have any judicial power and were thus unable to hear proof or swear witnesses.Tapp, p. 444 Taylor was inaugurated on December 12, 1899. Goebel announced his decision to contest the board's decision to the General Assembly. The Assembly appointed a committee to investigate the allegations contained in the challenges.Harrison in ''A New History of Kentucky'', p. 271 The members of the committee were drawn at random, though the drawing was likely rigged – only one Republican joined ten Democrats on the committee. (Chance dictated that the committee should have contained four or five Republicans.)Tapp, p. 445 Among the rules the General Assembly adopted for the contest committee were: that the committee report at the pleasure of the General Assembly, that debate be limited once the findings were presented, and that the report be voted on in a joint session of the Assembly.Hughes, p. 174 The rules further provided that the speaker of the House preside over the joint session instead of the lieutenant governor, as was customary. The Republican minority fought the provisions, but the Democratic majority passed them despite the opposition.

Republicans around the state expected the committee to recommend disqualification of enough ballots to make Goebel governor. Armed men from heavily Republican eastern Kentucky filled the capital.Tapp, p. 446 On the morning of January 30, 1900, as Goebel and two friends walked toward the capitol building, shots were fired, and Goebel fell wounded. After being denied entrance to the state capitol by armed men, the contest committee met in Frankfort's city hall

In local government, a city hall, town hall, civic centre (in the UK or Australia), guildhall, or a municipal building (in the Philippines), is the chief administrative building of a city, town, or other municipality. It usually houses ...

and, by a strict party-line vote, adopted a majority report that claimed Goebel and Beckham had received the most legitimate votes and should be installed in their respective offices.Tapp, p. 449 When Democratic legislators attempted to convene to approve the committee's report, they found the doors to the state capitol and other public locations in Frankfort blocked by armed citizens.Harrison in ''A New History of Kentucky'', p. 272 On January 31, 1900, they convened secretly in a Frankfort hotel, with no Republicans present, and voted to certify the findings of the contest committee, invalidating enough votes to make Goebel governor. Still lying on his sick bed, Goebel took the oath of office.

Goebel died of his wounds on February 3, 1900. Leaders from both parties drafted an agreement whereby Taylor and his Lieutenant Governor

A lieutenant governor, lieutenant-governor, or vice governor is a high officer of state, whose precise role and rank vary by jurisdiction. Often a lieutenant governor is the deputy, or lieutenant, to or ranked under a governor — a "second-in-comm ...

, John Marshall

John Marshall (September 24, 1755July 6, 1835) was an American politician and lawyer who served as the fourth Chief Justice of the United States from 1801 until his death in 1835. He remains the longest-serving chief justice and fourth-longes ...

, would step down from their respective offices, allowing Goebel's lieutenant governor, J. C. W. Beckham

John Crepps Wickliffe Beckham (August 5, 1869 – January 9, 1940) was an American attorney serving as the 35th Governor of Kentucky and a United States Senator from Kentucky. He was the state's first popularly-elected senator after the p ...

, to assume the governorship; in exchange, Taylor and Marshall would receive immunity from prosecution

Legal immunity, or immunity from prosecution, is a legal status wherein an individual or entity cannot be held liable for a violation of the law, in order to facilitate societal aims that outweigh the value of imposing liability in such cases. Su ...

in any actions they may have taken with regard to Goebel's assassination.Tapp, p. 451 The militia would withdraw from Frankfort, and the Goebel Election Law would be repealed and replaced with a fairer election law. Despite his allies' insistence, Taylor refused to sign the agreement.

Lower court decisions

As negotiations for a peaceful resolution of the elections for governor and lieutenant governor were ongoing, the Republican candidates for the state's minor offices filed suit in federal court inCincinnati, Ohio

Cincinnati ( ) is a city in the U.S. state of Ohio and the county seat of Hamilton County. Settled in 1788, the city is located at the northern side of the confluence of the Licking and Ohio rivers, the latter of which marks the state lin ...

, to prevent their removal from office. The case could have been filed in the federal court at Louisville, Kentucky

Louisville ( , , ) is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Kentucky and the 28th most-populous city in the United States. Louisville is the historical seat and, since 2003, the nominal seat of Jefferson County, on the Indiana borde ...

, but Judge Walter Evans asked to be excused from adjudicating the case. The Republican officers, represented by ex-Governor William O'Connell Bradley

William O'Connell Bradley (March 18, 1847May 23, 1914) was a politician from the U.S. state of Kentucky. He served as the 32nd Governor of Kentucky and was later elected by the state legislature as a U.S. senator from that state. The first R ...

and future governor Augustus E. Willson

Augustus Everett Willson (October 13, 1846 – August 24, 1931) was an American politician and the 36th Governor of Kentucky. Orphaned at the age of twelve, Willson went to live with relatives in New England. This move exposed him to such a ...

among others, argued that the Goebel Election Law deprived citizens of their right to vote

Suffrage, political franchise, or simply franchise, is the right to vote in public, political elections and referendums (although the term is sometimes used for any right to vote). In some languages, and occasionally in English, the right to v ...

. The right to vote, they claimed, was inherent in the Fourteenth Amendment's guarantee of "liberty", and could not be taken from any citizen without due process

Due process of law is application by state of all legal rules and principles pertaining to the case so all legal rights that are owed to the person are respected. Due process balances the power of law of the land and protects the individual pe ...

.

The case was argued before Judge (and later President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

* President (education), a leader of a college or university

*President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Automobiles

* Nissan President, a 1966–2010 Japanese f ...

) William Howard Taft

William Howard Taft (September 15, 1857March 8, 1930) was the 27th president of the United States (1909–1913) and the tenth chief justice of the United States (1921–1930), the only person to have held both offices. Taft was elected pr ...

, who held that the federal court could not prevent the removal of officers by injunction. He advised the Republicans to seek remedy quo warranto

In law, especially English and American common law, ''quo warranto'' (Medieval Latin for "by what warrant?") is a prerogative writ requiring the person to whom it is directed to show what authority they have for exercising some right, power, o ...

in the state courts. Taft further opined that, should any federal question be raised in such proceedings, the officers could seek remedy in a federal court on appeal. The Republicans were encouraged by Taft's decision, which cleared the way for an appeal all the way to the federal Supreme Court if a federal question could be raised.Hughes, p. 282

The Republican minor officeholders returned to the state courts with their case. Franklin County circuit court justice James E. Cantrill

James Edwards Cantrill (June 20, 1839 – April 5, 1908) was elected the 22nd Lieutenant Governor of Kentucky serving from 1879 to 1883 under Governor Luke P. Blackburn. He also served as a circuit court judge starting in 1892, and in 1898 was ...

ruled against them, and the Kentucky Court of Appeals

The Kentucky Court of Appeals is the lower of Kentucky's two appellate courts, under the Kentucky Supreme Court. Prior to a 1975 amendment to the Kentucky Constitution the Kentucky Court of Appeals was the only appellate court in Kentucky.

The ...

, then the state's court of last resort

A supreme court is the highest court within the hierarchy of courts in most legal jurisdictions. Other descriptions for such courts include court of last resort, apex court, and high (or final) court of appeal. Broadly speaking, the decisions ...

, sustained Cantrill's ruling by a vote of 4–3.Tapp, p. 453Klotter in ''William Goebel'', p. 114 Republican Attorney General Clifton J. Pratt continued with legal challenges and finally was allowed to serve out his term.Tapp, p. 505 Though Cantrill's decision was based on the invalidation of Louisville's vote and the votes of four counties in eastern Kentucky

Eastern may refer to:

Transportation

* China Eastern Airlines, a current Chinese airline based in Shanghai

*Eastern Air, former name of Zambia Skyways

*Eastern Air Lines, a defunct American airline that operated from 1926 to 1991

* Eastern Air ...

, none of the legislators from those areas were unseated.

Taft's ruling had no bearing on the cases of Governor Taylor and Lieutenant Governor Marshall except to spell out a means for them to take their cases to the federal courts, if necessary. On the same day that Taft's ruling was issued, Taylor filed suit in

Taft's ruling had no bearing on the cases of Governor Taylor and Lieutenant Governor Marshall except to spell out a means for them to take their cases to the federal courts, if necessary. On the same day that Taft's ruling was issued, Taylor filed suit in Jefferson County Jefferson County may refer to one of several counties or parishes in the United States, all of which are named directly or indirectly after Thomas Jefferson:

*Jefferson County, Alabama

*Jefferson County, Arkansas

*Jefferson County, Colorado

**Jeffe ...

circuit court against Beckham and Adjutant General

An adjutant general is a military chief administrative officer.

France

In Revolutionary France, the was a senior staff officer, effectively an assistant to a general officer. It was a special position for lieutenant-colonels and colonels in staf ...

John Breckinridge Castleman

John Breckinridge Castleman (June 30, 1841 – May 23, 1918) was a Confederate officer and later a United States Army brigadier general as well as a prominent landowner and businessman in Louisville, Kentucky.

Early life

John B. Castleman was th ...

to prevent them from exercising any authority due the offices they claimed.Tapp, p. 451Hughes, p. 284 Unaware of Taylor's suit, Beckham filed suit against Taylor for possession of the capitol and executive building in Franklin County circuit court – a court believed to be favorable to the Democratic cause. Marshall also filed suit against Beckham and state senator L. H. Carter to prevent them from exercising any authority in the state senate

A state legislature in the United States is the legislative body of any of the 50 U.S. states. The formal name varies from state to state. In 27 states, the legislature is simply called the ''Legislature'' or the ''State Legislature'', whil ...

, where the lieutenant governor was the presiding officer.

Republicans claimed that Taylor's suit, by virtue of having been filed two hours before Beckham's, gave the case precedence in Louisville. By mutual consent, the parties consolidated the suits, which were heard before Judge Emmet Field in Jefferson County circuit court. Both sides knew that Field's decision, whatever it might be, would be appealed, but both agreed to abide by the outcome of the final court's decision. The case was heard on March 1 and 2, 1900.Hughes, p. 285 Taylor's attorney's contended that the General Assembly had acted in a quasi-judicial manner, violating the principle of separation of powers

Separation of powers refers to the division of a state's government into branches, each with separate, independent powers and responsibilities, so that the powers of one branch are not in conflict with those of the other branches. The typica ...

.Klotter in ''William Goebel'', p. 112 Further, because the contest committee's report did not specify how many votes were invalid, Republicans argued that all 150,000 votes cast in the contested counties had been invalidated by the General Assembly's vote, and consequently, the voters of those counties had been illegally disenfranchised. The most the Assembly should have been able to do, they claimed, was to invalidate the entire election. Finally, they contended that the alleged illegal activities of the General Assembly had deprived Taylor and Marshall of their property rights – the "property" in question being the offices they claimed – and their liberty to hold an elected office.Hughes, p. 288 Attorneys for Beckham contended that legislative actions historically had not been subject to judicial review, and indeed were not subject to such under any provision of the state constitution.

On March 10, 1900, Field sided with the Democrats. In his ruling, he opined that legislative actions "must be taken as absolute" and that the court did not have the authority to circumvent the legislative record. Republicans appealed the decision to the Kentucky Court of Appeals. In their appeal, they were careful to raise a federal issue.Hughes, p. 286 If Judge Field's ruling was correct, and the Board of Elections, the General Assembly, or both had the right under the state constitution to an absolute review of all elections, then the Assembly had been given absolute arbitrary power over elections, in conflict with the federal constitution.

On April 6, 1900, the Court of Appeals upheld Judge Field's decision by a vote of 6–1. The majority opinion held that an elected office is not property and thus not subject to the protections guaranteed in the Fourteenth Amendment.Willoughby, "Taylor v. Beckham" As a creation of the Kentucky Constitution The Constitution of the Commonwealth of Kentucky is the document that governs the Commonwealth of Kentucky. It was first adopted in 1792 and has since been rewritten three times and amended many more. The later versions were adopted in 1799, 1850, ...

, the court held, any elective office is conferred and held only subject to the provisions of that constitution. This put the matter beyond the reach of any judicial review, according to the court.

The four Democratic judges concurred on the majority opinion

In law, a majority opinion is a judicial opinion agreed to by more than half of the members of a court. A majority opinion sets forth the decision of the court and an explanation of the rationale behind the court's decision.

Not all cases hav ...

.Hughes, p. 317 Two Republican judges, in a separate opinion, concurred with the majority opinion, but declared that Taylor and Marshall had been done an irreparable injustice. The lone dissent, authored by the court's third Republican, held that the contest board had acted outside its legal authority. Republicans turned to the Supreme Court of the United States as their final option.

Supreme Court

Louisville attorney Helm Bruce opened the Republicans' case before the Supreme Court on April 1, 1900.Hughes, p. 324 He maintained that, after Taylor's election had been certified by the Board of Elections, he was legally the governor of Kentucky, and the attempt by the legislature to oust him from office amounted to an arbitrary and despotic use of power, not a due process, as the federal constitution required. In addressing the complaints upon which the dismissal of ballots was justified – namely, the intimidation of voters in Jefferson County by the state militia and the use of "thin ballots" in fortyKentucky counties

There are 120 counties in the U.S. Commonwealth of Kentucky. Despite ranking 37th in size by area, Kentucky has 120 counties, fourth among states (including Virginia's independent cities). The original motivation for having so many counties was ...

– Bruce maintained that even if the allegations were true, both were the fault of the state, not Taylor and Marshall, and were not sufficient grounds upon which to deny them their right to the offices they claimed.Hughes, p. 325

Bruce was followed by Lawrence N. Maxwell, counsel for Beckham. Maxwell reiterated that the General Assembly had acted within its enumerated powers under the state constitution in deciding the outcome of the disputed election. He claimed that the decision of the state court of appeals made it clear that Taylor had not been legally elected governor, and therefore never possessed the property he was now claiming had been taken from him without due process. Maxwell further asserted that this disposed of any federal questions with regard to the case, and that the Supreme Court could claim no jurisdiction. The decision of the state court of appeals should be allowed to stand, he concluded. Lewis McQuown further argued on behalf of Beckham that, even if Taylor's claim to the governorship were legitimate, the investigation and decision by the General Assembly's contest committee represented sufficient due process.Hughes, p. 326 He acknowledged that the Goebel Election Law's provision that the legislature be the arbiter of any contested gubernatorial election differed little if at all from provisions in as many as twenty other states. If the Goebel Election Law was constitutional, as it had before been declared, then the Supreme Court had no jurisdiction regarding how it had been administered.

When Maxwell concluded his argument, ex-Governor Bradley spoke on Taylor's behalf.Hughes, p. 327 After reiterating Taylor's legal claim to the office of governor, he answered the question of jurisdiction by citing '' Thayer v. Boyd'', a similar case in which the court had assumed jurisdiction. He further quoted authorities who opined that an elected office was property, using this to contend that Taylor's rights under the Fourteenth Amendment had been violated, thus giving the court jurisdiction. Also, Bradley asserted, the election of some members of the Assembly's contest committee would hinge on the decision of that very committee. At least one member of the committee was known to have wagered on the election's outcome. These facts should have nullified the decision of the committee and the Assembly on the grounds that it had left some members as judges of their own cases. Finally, Bradley cited irregularities in the proceedings of the contest committee, including insufficient time given for the review of testimony provided in written form by Taylor and Marshall's legal representation.Hughes, p. 328 Following Bradley's argument, the court recessed until May 14, 1900.

Opinion of the Court

Chief Justice

Chief Justice Melville Fuller

Melville Weston Fuller (February 11, 1833 – July 4, 1910) was an American politician, attorney, and jurist who served as the eighth chief justice of the United States from 1888 until his death in 1910. Staunch conservatism marked his ...

delivered the opinion of the court on May 21, 1900.Hughes, p. 341 This opinion held that there were no federal issues in question in the case, and that the court lacked jurisdiction. The opinion affirmed the state court of appeals' assertion that an elective office was not property. Justices Gray

Grey (more common in British English) or gray (more common in American English) is an intermediate color between black and white. It is a neutral or achromatic color, meaning literally that it is "without color", because it can be composed ...

, White

White is the lightness, lightest color and is achromatic (having no hue). It is the color of objects such as snow, chalk, and milk, and is the opposite of black. White objects fully diffuse reflection, reflect and scattering, scatter all the ...

, Shiras Shiras may refer to:

* George Shiras Jr. (1832–1924), Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States

* George Shiras III (1859–1942), U.S. Representative from the state of Pennsylvania

*Leif Shiras (born 1959), American tennis play ...

, and Peckham

Peckham () is a district in southeast London, within the London Borough of Southwark. It is south-east of Charing Cross. At the 2001 Census the Peckham ward had a population of 14,720.

History

"Peckham" is a Saxon place name meaning the vill ...

concurred with the majority opinion.

In his 1910 book, ''The Constitutional Law of the United States'', Westel W. Willoughby

Westel Woodbury Willoughby (20 July 1867 – 25 March 1945) was an American academic.

He and his twin brother to William F. Willoughby were the sons of Westel Willoughby and Jennie Rebecca (Woodbury) Willoughby. Their lawyer father had been Maj ...

noted that the court's ruling that an elective office was not property was at odds with previous decisions in which it had assumed jurisdiction in cases between two contestants for an office to determine if due process was granted. By assuming jurisdiction in these cases, Willoughby claimed, the court had given elective offices standing as property. Accordingly, Justice Joseph McKenna

Joseph McKenna (August 10, 1843 – November 21, 1926) was an American politician who served in all three branches of the U.S. federal government, as a member of the U.S. House of Representatives, as U.S. Attorney General and as an Associate Ju ...

issued a separate concurring opinion in which he stated: "I agree fully with those decisions which are referred to n the majority opinion

N, or n, is the fourteenth letter in the Latin alphabet, used in the modern English alphabet, the alphabets of other western European languages and others worldwide. Its name in English is ''en'' (pronounced ), plural ''ens''.

History

...

and which hold that as between the State and the office holder there is no contract right either to the term of office or to the amount of salary, and that the legislature may, if not restrained by constitutional provisions, abolish the office or reduce the salary. But when the office is not disturbed, when the salary is not changed, and when, under the Constitution of the State, neither can be by the legislature, and the question is simply whether one shall be deprived of that office and its salary, and both given to another, a different question is presented, and in such a case to hold that the incumbent has no property in the office, with its accompanying salary, does not commend itself to my judgment."

Dissent of Justice Brewer

JusticeDavid J. Brewer

David Josiah Brewer (June 20, 1837 – March 28, 1910) was an American jurist who served as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1890 to 1910. An appointee of President Benjamin Harrison, he supported states' rig ...

issued a dissent stating that he believed that due process had been observed and that the majority opinion should have affirmed the lower court rulings rather than dismissing the case. In his opinion, Brewer stated: " I understand the law, this court has jurisdiction to review a judgment of the highest court of a State ousting one from his office and giving it to another, and a right to inquire whether that judgment is right or wrong in respect to any federal question such as due process of law, I think the writ of error should not be dismissed, but that the judgment of the Court of Appeals of Kentucky should be affirmed." Justice Henry B. Brown

Henry Billings Brown (March 2, 1836 – September 4, 1913) was an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1891 to 1906.

Although a respected lawyer and U.S. District Judge before ascending to the high court, Brown ...

concurred with Brewer.

Dissent of Justice Harlan

The only dissent came from KentuckianJohn Marshall Harlan

John Marshall Harlan (June 1, 1833 – October 14, 1911) was an American lawyer and politician who served as an associate justice of the U.S. Supreme Court from 1877 until his death in 1911. He is often called "The Great Dissenter" due to his ...

. Harlan opined that not only did the court have jurisdiction, it should have sustained the writ of error

In law, an appeal is the process in which cases are reviewed by a higher authority, where parties request a formal change to an official decision. Appeals function both as a process for error correction as well as a process of clarifying and ...

on the grounds that the General Assembly's actions had deprived Taylor and Marshall of property without due process, in violation of the Fourteenth Amendment. Going beyond the claim that an elective office is property, Harlan wrote that the right to hold office fell within the definition of "liberty" as used in the Fourteenth Amendment. Justifying this claim, Harlan wrote: "What more directly involves the liberty of the citizen than to be able to enter upon the discharge of the duties of an office to which he has been lawfully elected by his fellow citizens?"

Whereas the majority opinion wholly ignored the proceedings of the General Assembly as irrelevant (the court lacking jurisdiction) and Brewer and Brown affirmed them, Harlan excoriated the legislature in his dissent. "Looking into the record before us, I find such action taken by the body claiming to be organized as the lawful legislature of Kentucky as was discreditable in the last degree and unworthy of the free people whom it professed to represent. ... Those who composed that body seemed to have shut their eyes against the proof for fear that it would compel them to respect the popular will as expressed at the polls." He also expressed disbelief at the majority opinion: " e overturning of the public will, as expressed at the ballot box, without evidence or against evidence, in order to accomplish partisan ends, is a crime against free government, and deserves the execration of all lovers of liberty. ... I cannot believe that the judiciary is helpless in the presence of such a crime."

Subsequent developments

''Taylor v. Beckham'' established as a judicial principle that public offices are mere agencies or trusts, and not property protected by the Fourteenth Amendment. The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit in 2005 stated that the Supreme Court subsequently had adopted a more expansive approach to identifying "property" within the meaning of the Fourteenth Amendment, but that it is the Supreme Court's prerogative alone to overrule one of its precedents.''Velez v. Levy'', 401 F.3d 75, 86 - 87 (2d Cir. 2005).Notes

References

* * * * * * * * *External links

* {{Good article 1900 in United States case law Legal history of Kentucky United States elections case law United States civil due process case law United States Supreme Court cases 1900 in Kentucky Kentucky gubernatorial elections United States Supreme Court cases of the Fuller Court