Tambora Volcano on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Mount Tambora, or Tomboro, is an active

Tambora lies

north of the

Tambora lies

north of the

The 1815 eruption released 10 to 120 million tons of

The 1815 eruption released 10 to 120 million tons of

A human settlement obliterated by the Tambora eruption was discovered in 2004. That summer, a team led by Haraldur Sigurðsson with scientists from the

A human settlement obliterated by the Tambora eruption was discovered in 2004. That summer, a team led by Haraldur Sigurðsson with scientists from the

A team led by the Swiss botanist

A team led by the Swiss botanist

stratovolcano

A stratovolcano, also known as a composite volcano, is a typically conical volcano built up by many alternating layers (strata) of hardened lava and tephra. Unlike shield volcanoes, stratovolcanoes are characterized by a steep profile with ...

in West Nusa Tenggara

West Nusa Tenggara ( – NTB) is a provinces of Indonesia, province of Indonesia. It comprises the western portion of the Lesser Sunda Islands, with the exception of Bali which is its own province. The area of this province is which consists of ...

, Indonesia

Indonesia, officially the Republic of Indonesia, is a country in Southeast Asia and Oceania, between the Indian Ocean, Indian and Pacific Ocean, Pacific oceans. Comprising over List of islands of Indonesia, 17,000 islands, including Sumatra, ...

. Located on Sumbawa

Sumbawa, is an Indonesian island, located in the middle of the Lesser Sunda Islands chain, with Lombok to the west, Flores to the east, and Sumba further to the southeast. Along with Lombok, it forms the province of West Nusa Tenggara, but th ...

in the Lesser Sunda Islands

The Lesser Sunda Islands (, , ), now known as Nusa Tenggara Islands (, or "Southeast Islands"), are an archipelago in the Indonesian archipelago. Most of the Lesser Sunda Islands are located within the Wallacea region, except for the Bali pro ...

, it was formed by the active subduction zone

Subduction is a geological process in which the oceanic lithosphere and some continental lithosphere is recycled into the Earth's mantle at the convergent boundaries between tectonic plates. Where one tectonic plate converges with a second p ...

s beneath it. Before the 1815 eruption, its elevation reached more than high, making it one of the tallest peaks in the Indonesian archipelago.

Tambora underwent a series of violent eruptions, beginning on 5 April 1815, and culminating in the largest eruption in recorded human history and the largest of the Holocene

The Holocene () is the current geologic time scale, geological epoch, beginning approximately 11,700 years ago. It follows the Last Glacial Period, which concluded with the Holocene glacial retreat. The Holocene and the preceding Pleistocene to ...

(10,000 years ago to present). The magma chamber

A magma chamber is a large pool of liquid rock beneath the surface of the Earth. The molten rock, or magma, in such a chamber is less dense than the surrounding country rock, which produces buoyant forces on the magma that tend to drive it u ...

under Tambora had been drained by previous eruptions and lay dormant for several centuries as it refilled. Volcanic activity reached a peak that year, culminating in an explosive eruption that was heard on Sumatra

Sumatra () is one of the Sunda Islands of western Indonesia. It is the largest island that is fully within Indonesian territory, as well as the list of islands by area, sixth-largest island in the world at 482,286.55 km2 (182,812 mi. ...

island, more than

away and possibly over away in Thailand and Laos. Heavy volcanic ash

Volcanic ash consists of fragments of rock, mineral crystals, and volcanic glass, produced during volcanic eruptions and measuring less than 2 mm (0.079 inches) in diameter. The term volcanic ash is also often loosely used to r ...

rains were observed as far away as Borneo

Borneo () is the List of islands by area, third-largest island in the world, with an area of , and population of 23,053,723 (2020 national censuses). Situated at the geographic centre of Maritime Southeast Asia, it is one of the Greater Sunda ...

, Sulawesi

Sulawesi ( ), also known as Celebes ( ), is an island in Indonesia. One of the four Greater Sunda Islands, and the List of islands by area, world's 11th-largest island, it is situated east of Borneo, west of the Maluku Islands, and south of Min ...

, Java

Java is one of the Greater Sunda Islands in Indonesia. It is bordered by the Indian Ocean to the south and the Java Sea (a part of Pacific Ocean) to the north. With a population of 156.9 million people (including Madura) in mid 2024, proje ...

, and Maluku islands

The Maluku Islands ( ; , ) or the Moluccas ( ; ) are an archipelago in the eastern part of Indonesia. Tectonics, Tectonically they are located on the Halmahera Plate within the Molucca Sea Collision Zone. Geographically they are located in West ...

, and the maximum elevation of Tambora was reduced from about . Estimates vary, but the death toll was at least 71,000 people. The eruption contributed to global climate

Climate is the long-term weather pattern in a region, typically averaged over 30 years. More rigorously, it is the mean and variability of meteorological variables over a time spanning from months to millions of years. Some of the meteoro ...

anomalies in the following years, while 1816 became known as the "year without a summer

The year 1816 is known as the Year Without a Summer because of severe climate abnormalities that caused average global temperatures to decrease by . Summer temperatures in Europe were the coldest of any on record between 1766 and 2000, resultin ...

" because of the effect on North American and European weather. In the Northern Hemisphere

The Northern Hemisphere is the half of Earth that is north of the equator. For other planets in the Solar System, north is defined by humans as being in the same celestial sphere, celestial hemisphere relative to the invariable plane of the Solar ...

, crops failed and livestock died, resulting in the worst famine of the century.

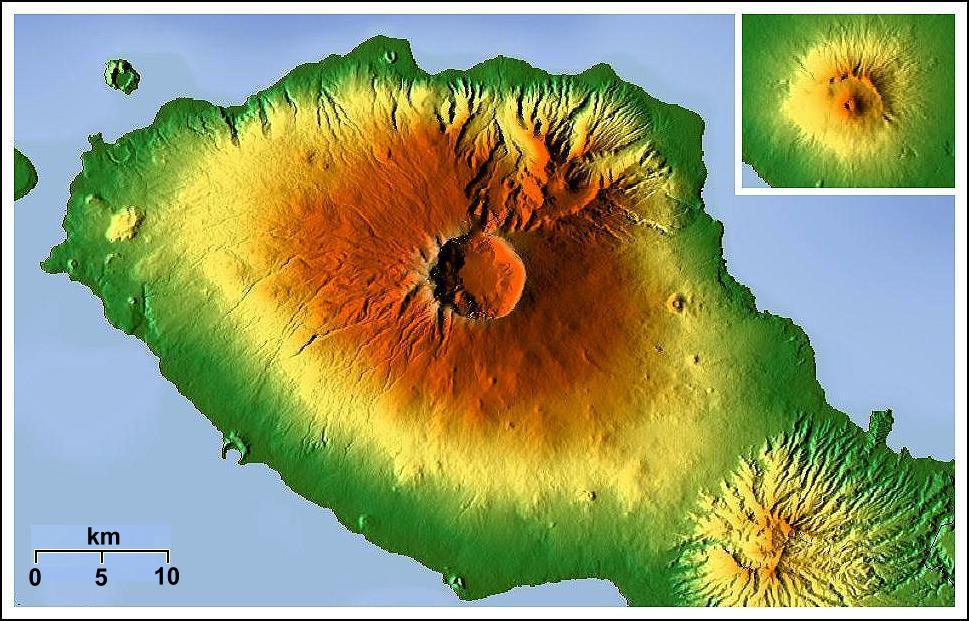

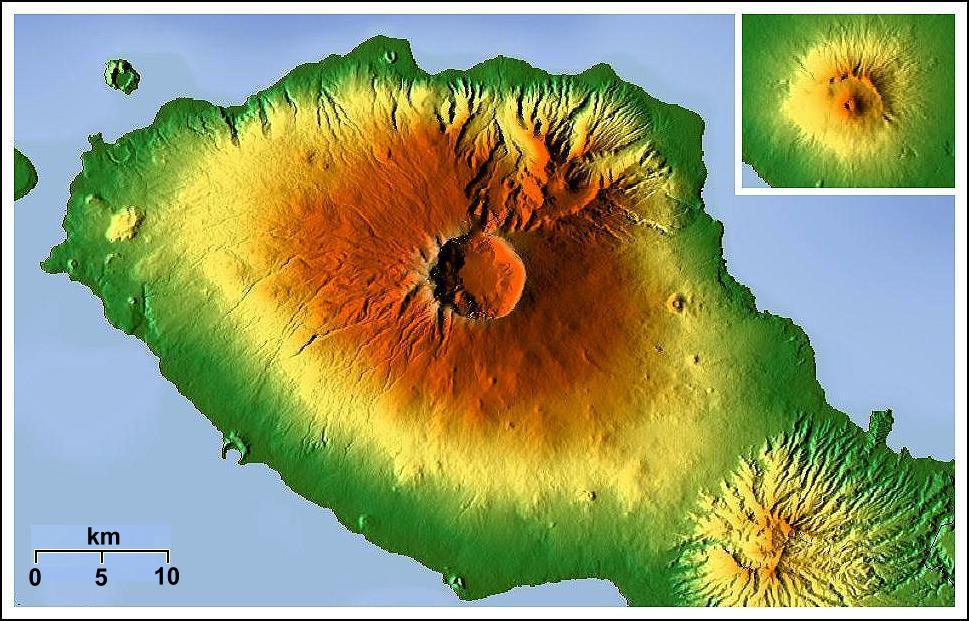

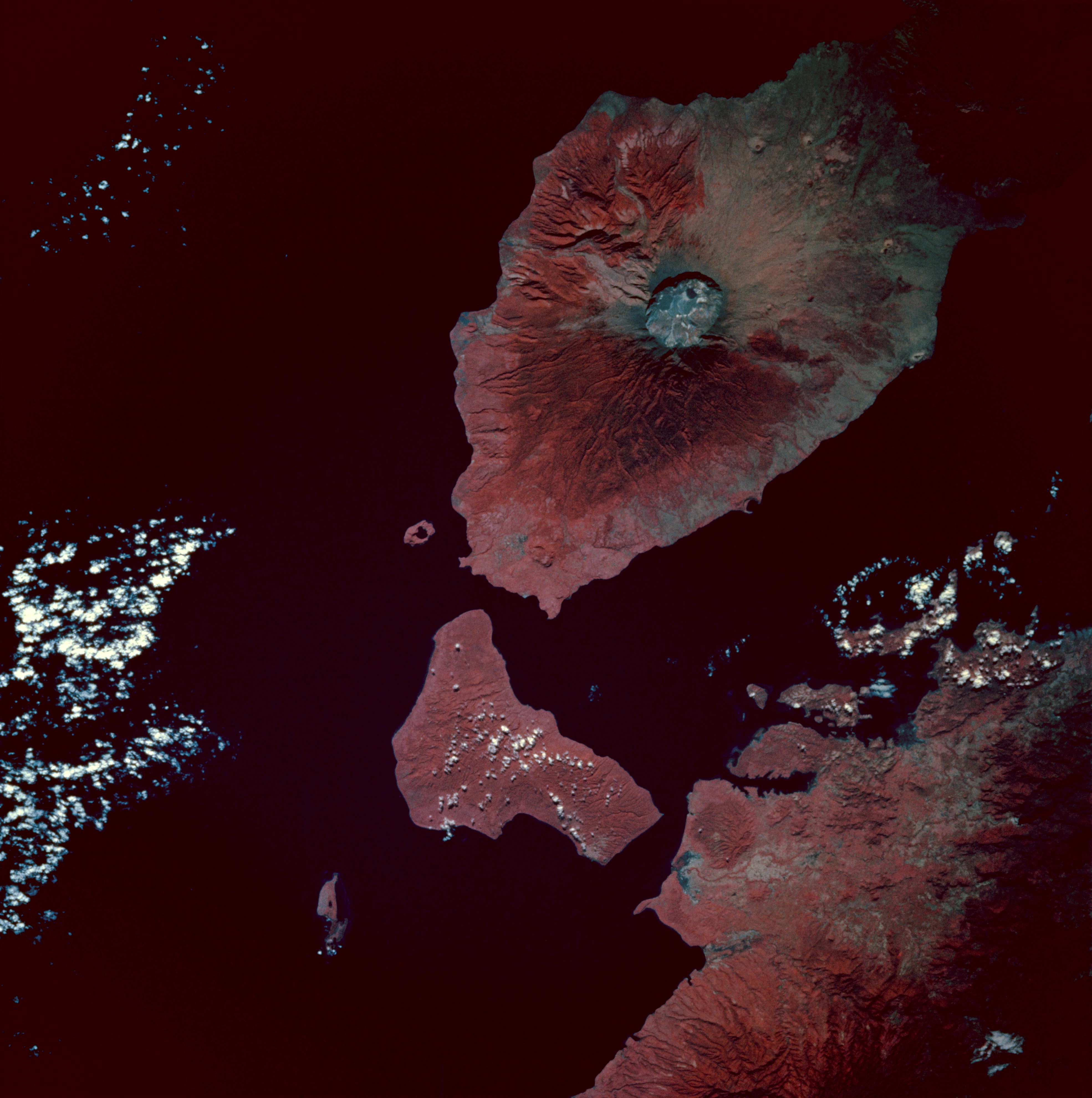

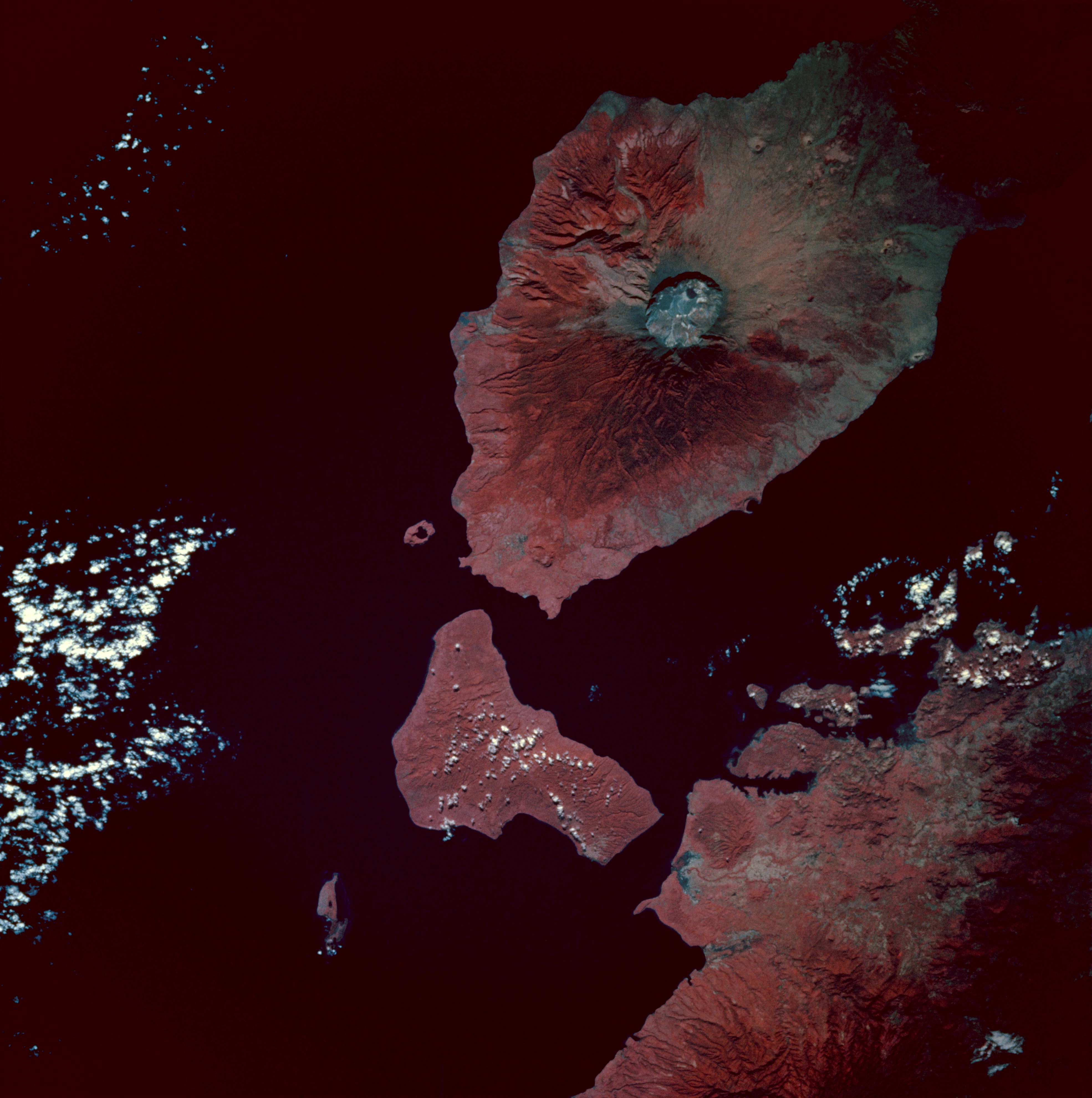

Geographical setting

Mount Tambora, also known as Tomboro, is situated in the northern part ofSumbawa

Sumbawa, is an Indonesian island, located in the middle of the Lesser Sunda Islands chain, with Lombok to the west, Flores to the east, and Sumba further to the southeast. Along with Lombok, it forms the province of West Nusa Tenggara, but th ...

island, part of the Lesser Sunda Islands

The Lesser Sunda Islands (, , ), now known as Nusa Tenggara Islands (, or "Southeast Islands"), are an archipelago in the Indonesian archipelago. Most of the Lesser Sunda Islands are located within the Wallacea region, except for the Bali pro ...

. It is a segment of the Sunda Arc

The Sunda Arc is a volcanic arc that produced the volcanoes that form the topographic spine of the islands of Sumatra, Nusa Tenggara, Java, the Sunda Strait, and the Lesser Sunda Islands. The Sunda Arc begins at Sumatra and ends at Flores, and i ...

, a chain of volcanic island

Geologically, a volcanic island is an island of volcanic origin. The term high island can be used to distinguish such islands from low islands, which are formed from sedimentation or the uplifting of coral reefs (which have often formed ...

s that make up the southern chain of the Indonesian archipelago

An archipelago ( ), sometimes called an island group or island chain, is a chain, cluster, or collection of islands. An archipelago may be in an ocean, a sea, or a smaller body of water. Example archipelagos include the Aegean Islands (the o ...

. Tambora forms its own peninsula

A peninsula is a landform that extends from a mainland and is only connected to land on one side. Peninsulas exist on each continent. The largest peninsula in the world is the Arabian Peninsula.

Etymology

The word ''peninsula'' derives , . T ...

on Sumbawa, known as the Sanggar peninsula. To the north of the peninsula is the Flores Sea

The Flores Sea covers of water in Indonesia. The sea is bounded on the north by the island of Celebes and on the south by Sunda Islands, the Sunda Islands of Flores and Sumbawa.

Geography

The seas that border the Flores Sea are the Bali Sea ...

and to the south is the long and wide Saleh Bay

Saleh Bay (Indonesian: ''Teluk Saleh'') is the largest bay in the island of Sumbawa

Sumbawa, is an Indonesian island, located in the middle of the Lesser Sunda Islands chain, with Lombok to the west, Flores to the east, and Sumba further t ...

. At the mouth of Saleh Bay there is an islet called Mojo.

Besides the seismologist

Seismology (; from Ancient Greek σεισμός (''seismós'') meaning "earthquake" and -λογία (''-logía'') meaning "study of") is the scientific study of earthquakes (or generally, quakes) and the generation and propagation of elastic ...

s and vulcanologists who monitor the mountain's activity, Mount Tambora is an area of interest to archaeologist

Archaeology or archeology is the study of human activity through the recovery and analysis of material culture. The archaeological record consists of Artifact (archaeology), artifacts, architecture, biofact (archaeology), biofacts or ecofacts, ...

s and biologist

A biologist is a scientist who conducts research in biology. Biologists are interested in studying life on Earth, whether it is an individual Cell (biology), cell, a multicellular organism, or a Community (ecology), community of Biological inter ...

s. The mountain also attracts tourists for hiking

A hike is a long, vigorous walk, usually on trails or footpaths in the countryside. Walking for pleasure developed in Europe during the eighteenth century. Long hikes as part of a religious pilgrimage have existed for a much longer time.

"Hi ...

and wildlife activities, though in small numbers. The two nearest cities are Dompu

Dompu is a town and the administrative centre of the Dompu Regency, located in the eastern part of the island of Sumbawa, in central Indonesia's province of West Nusa Tenggara. It is the third largest town on the island of Sumbawa, with a distric ...

and Bima

Bima city ( Bima: ''Mbojo'') is a coastal city on the east of the island of Sumbawa in Indonesia's province of West Nusa Tenggara.

It is the largest city on the island of Sumbawa, with a population of 142,443 at the 2010 censusBiro Pusat Stati ...

. There are three concentrations of villages around the mountain slope. At the east is Sanggar village, to the northwest are Doro Peti and Pesanggrahan villages, and to the west is Calabai village.

There are two routes of ascent to the caldera

A caldera ( ) is a large cauldron-like hollow that forms shortly after the emptying of a magma chamber in a volcanic eruption. An eruption that ejects large volumes of magma over a short period of time can cause significant detriment to the str ...

. The first begins at Doro Mboha village on the southeast of the mountain and follows a paved road through a cashew

Cashew is the common name of a tropical evergreen tree ''Anacardium occidentale'', in the family Anacardiaceae. It is native to South America and is the source of the cashew nut and the cashew apple, an accessory fruit. The tree can grow as t ...

plantation to an elevation of . The road terminates at the southern part of the caldera, which at is reachable only by hiking. This location is only one hour from the caldera, and usually serves as a base camp from which volcanic activity can be monitored. The second route starts from Pancasila village at the northwest of the mountain and is only accessible on foot. The hike from Pancasila at elevation to the caldera of the volcano takes approximately 14 hours with several stops (''pos'') en route to the top. The trail leads through dense jungle with wildlife such as ''Elaeocarpus

''Elaeocarpus'' is a genus of nearly five hundred species of flowering plants in the family Elaeocarpaceae native to the Western Indian Ocean, Tropical and Subtropical Asia, and the Pacific. Plants in the genus ''Elaeocarpus'' are trees or shrub ...

'', Asian water monitor

The Asian water monitor (''Varanus salvator'') is a large Varanidae, varanid lizard native to South Asia, South and Southeast Asia. It is widely considered to be the List of largest extant lizards, second-largest lizard species, after the Komodo ...

, reticulated python

The reticulated python (''Malayopython reticulatus'') is a Pythonidae, python species native to South Asia, South and Southeast Asia. It is the world's List of largest snakes, longest snake, and the list of largest snakes, third heaviest snake. I ...

, hawks

Hawks are bird of prey, birds of prey of the family Accipitridae. They are very widely distributed and are found on all continents, except Antarctica.

The subfamily Accipitrinae includes goshawks, sparrowhawks, sharp-shinned hawks, and othe ...

, orange-footed scrubfowl

The orange-footed scrubfowl (''Megapodius reinwardt''), also known as orange-footed megapode or just scrubfowl, is a small megapode of the family Megapodiidae native to many islands in the Lesser Sunda Islands as well as southern New Guinea and n ...

, pale-shouldered cicadabird (''Coracina dohertyi''), brown

Brown is a color. It can be considered a composite color, but it is mainly a darker shade of orange. In the CMYK color model used in printing and painting, brown is usually made by combining the colors Orange (colour), orange and black.

In the ...

and scaly-crowned honeyeater, yellow-crested cockatoo

The yellow-crested cockatoo (''Cacatua sulphurea'') also known as the lesser sulphur-crested cockatoo, is a medium-sized (about 34-cm-long) cockatoo with white plumage, bluish-white bare orbital skin, grey feet, a black bill, and a retractile ye ...

, yellow-ringed white-eye, helmeted friarbird

The helmeted friarbird (''Philemon buceroides'') is part of the ''Meliphagidae'' family. The helmeted friarbird, along with all their subspecies, is commonly referred to as “leatherhead” by the birding community.

Taxonomy

The helmeted friarb ...

, wild boar

The wild boar (''Sus scrofa''), also known as the wild swine, common wild pig, Eurasian wild pig, or simply wild pig, is a Suidae, suid native to much of Eurasia and North Africa, and has been introduced to the Americas and Oceania. The speci ...

, Javan rusa

The Javan rusa or Sunda sambar (''Rusa timorensis'') is a large deer species native to Indonesia and East Timor. Introduced populations exist in a wide variety of locations in the Southern Hemisphere. ''Rusa'' is the Malay word for "deer" in ...

and crab-eating macaque

The crab-eating macaque (''Macaca fascicularis''), also known as the long-tailed macaque or cynomolgus macaque, is a cercopithecine primate native to Southeast Asia. As a synanthropic species, the crab-eating macaque thrives near human settlem ...

s.

History

Geological history

Formation

Tambora lies

north of the

Tambora lies

north of the Java Trench

The Sunda Trench, earlier known as and sometimes still indicated as the Java Trench, is an oceanic trench located in the Indian Ocean near Sumatra, formed where the Australian- Capricorn plates subduct under a part of the Eurasian plate. It is ...

system and above the upper surface of the active north-dipping subduction zone

Subduction is a geological process in which the oceanic lithosphere and some continental lithosphere is recycled into the Earth's mantle at the convergent boundaries between tectonic plates. Where one tectonic plate converges with a second p ...

. Sumbawa Island is flanked to the north and south by oceanic crust

Oceanic crust is the uppermost layer of the oceanic portion of the tectonic plates. It is composed of the upper oceanic crust, with pillow lavas and a dike complex, and the lower oceanic crust, composed of troctolite, gabbro and ultramaf ...

. The convergence rate of the Australian Plate

The Australian plate is or was a major tectonic plate in the eastern and, largely, southern hemispheres. Originally a part of the ancient continent of Gondwana, Australia remained connected to India and Antarctica until approximately when Indi ...

beneath the Sunda Plate

The Sunda plate is a minor tectonic plate straddling the equator in the Eastern Hemisphere on which the majority of Southeast Asia is located.

The Sunda plate was formerly considered a part of the Eurasian plate, but the GPS measurements hav ...

is per year. Estimates for the onset of the volcanism at Mount Tambora range from 57 to 43 ka. The latter estimate published in 2012 is based on argon dating of the first pre-caldera lava flows. The formation of Tambora drained a large magma chamber

A magma chamber is a large pool of liquid rock beneath the surface of the Earth. The molten rock, or magma, in such a chamber is less dense than the surrounding country rock, which produces buoyant forces on the magma that tend to drive it u ...

pre-existing under the mountain. The Mojo islet was formed as part of this process in which Saleh Bay first appeared as a sea basin

In hydrology, an oceanic basin (or ocean basin) is anywhere on Earth that is covered by seawater. Geologically, most of the ocean basins are large geologic basins that are below sea level.

Most commonly the ocean is divided into ...

about 25,000 years ago.

A high volcanic cone with a single central vent formed before the 1815 eruption, which follows a stratovolcano

A stratovolcano, also known as a composite volcano, is a typically conical volcano built up by many alternating layers (strata) of hardened lava and tephra. Unlike shield volcanoes, stratovolcanoes are characterized by a steep profile with ...

shape. The diameter at the base is . The volcano frequently erupted lava, which descended over steep slopes. Tambora has produced trachybasalt

Trachybasalt is a volcanic rock with a composition between trachyte and basalt. It resembles basalt but has a high content of alkali metal oxides. Minerals in trachybasalt include alkali feldspar, calcic plagioclase, olivine, clinopyroxene and l ...

and trachyandesite

Trachyandesite is an extrusive igneous rock with a composition between trachyte and andesite. It has little or no free quartz, but is dominated by sodic plagioclase and alkali feldspar. It is formed from the cooling of lava enriched in alkal ...

rocks which are rich in potassium

Potassium is a chemical element; it has Symbol (chemistry), symbol K (from Neo-Latin ) and atomic number19. It is a silvery white metal that is soft enough to easily cut with a knife. Potassium metal reacts rapidly with atmospheric oxygen to ...

. The volcanics contain phenocryst

image:montblanc granite phenocrysts.JPG, 300px, Granites often have large feldspar, feldspathic phenocrysts. This granite, from the Switzerland, Swiss side of the Mont Blanc massif, has large white phenocrysts of plagioclase (that have trapezoid sh ...

s of apatite

Apatite is a group of phosphate minerals, usually hydroxyapatite, fluorapatite and chlorapatite, with high concentrations of Hydroxide, OH−, Fluoride, F− and Chloride, Cl− ion, respectively, in the crystal. The formula of the admixture of ...

, biotite

Biotite is a common group of phyllosilicate minerals within the mica group, with the approximate chemical formula . It is primarily a solid-solution series between the iron- endmember annite, and the magnesium-endmember phlogopite; more al ...

, clinopyroxene

The pyroxenes (commonly abbreviated Px) are a group of important rock-forming inosilicate minerals found in many igneous and metamorphic rocks. Pyroxenes have the general formula , where X represents ions of calcium (Ca), sodium (Na), iron (Fe ...

, leucite

Leucite (from the Greek word ''leukos'' meaning white) is a rock-forming mineral of the feldspathoid group, silica-undersaturated and composed of potassium and aluminium tectosilicate KAlSi2O6. Crystals have the form of cubic icositetrahedra b ...

, magnetite

Magnetite is a mineral and one of the main iron ores, with the chemical formula . It is one of the iron oxide, oxides of iron, and is ferrimagnetism, ferrimagnetic; it is attracted to a magnet and can be magnetization, magnetized to become a ...

, olivine

The mineral olivine () is a magnesium iron Silicate minerals, silicate with the chemical formula . It is a type of Nesosilicates, nesosilicate or orthosilicate. The primary component of the Earth's upper mantle (Earth), upper mantle, it is a com ...

and plagioclase

Plagioclase ( ) is a series of Silicate minerals#Tectosilicates, tectosilicate (framework silicate) minerals within the feldspar group. Rather than referring to a particular mineral with a specific chemical composition, plagioclase is a continu ...

, with the exact composition of the phenocrysts varying between different rock types. Orthopyroxene

The pyroxenes (commonly abbreviated Px) are a group of important rock-forming inosilicate minerals found in many igneous and metamorphic rocks. Pyroxenes have the general formula , where X represents ions of calcium (Ca), sodium (Na), iron (Fe( ...

is absent in the trachyandesites of Tambora.Foden, 1979, p. 49 Olivine is most present in the rocks with less than 53 percent SiO2, while it is absent in the more silica-rich volcanics, characterised by the presence of biotite phenocrysts.Foden, 1979, p. 50 The mafic series also contain titanium

Titanium is a chemical element; it has symbol Ti and atomic number 22. Found in nature only as an oxide, it can be reduced to produce a lustrous transition metal with a silver color, low density, and high strength, resistant to corrosion in ...

magnetite

Magnetite is a mineral and one of the main iron ores, with the chemical formula . It is one of the iron oxide, oxides of iron, and is ferrimagnetism, ferrimagnetic; it is attracted to a magnet and can be magnetization, magnetized to become a ...

and the trachybasalts are dominated by anorthosite

Anorthosite () is a phaneritic, intrusive rock, intrusive igneous rock characterized by its composition: mostly plagioclase feldspar (90–100%), with a minimal mafic component (0–10%). Pyroxene, ilmenite, magnetite, and olivine are the mafic ...

-rich plagioclase.Foden, 1979, p. 51 Rubidium

Rubidium is a chemical element; it has Symbol (chemistry), symbol Rb and atomic number 37. It is a very soft, whitish-grey solid in the alkali metal group, similar to potassium and caesium. Rubidium is the first alkali metal in the group to have ...

, strontium

Strontium is a chemical element; it has symbol Sr and atomic number 38. An alkaline earth metal, it is a soft silver-white yellowish metallic element that is highly chemically reactive. The metal forms a dark oxide layer when it is exposed to ...

and phosphorus pentoxide

Phosphorus pentoxide is a chemical compound with molecular formula Phosphorus, P4Oxygen, O10 (with its common name derived from its empirical formula, P2O5). This white crystalline solid is the anhydride of phosphoric acid. It is a powerful desic ...

are especially rich in the lavas from Tambora, more than the comparable ones from Mount Rinjani

Mount Rinjani ( Sasak: ''Gunong Rinjani'', ) is an active volcano in Indonesia on the island of Lombok. Administratively the mountain is in the Regency of North Lombok, West Nusa Tenggara ( Indonesian: ''Nusa Tenggara Barat'', NTB). It rises t ...

.Foden, 1979, p. 56 The lavas of Tambora are slightly enriched in zircon

Zircon () is a mineral belonging to the group of nesosilicates and is a source of the metal zirconium. Its chemical name is zirconium(IV) silicate, and its corresponding chemical formula is Zr SiO4. An empirical formula showing some of th ...

compared with those of Rinjani.Foden, 1979, p.60

The magma

Magma () is the molten or semi-molten natural material from which all igneous rocks are formed. Magma (sometimes colloquially but incorrectly referred to as ''lava'') is found beneath the surface of the Earth, and evidence of magmatism has also ...

involved in the 1815 eruption originated in the mantle and was further modified by melts derived from subduct

Subduction is a geological process in which the oceanic lithosphere and some continental lithosphere is recycled into the Earth's mantle at the convergent boundaries between tectonic plates. Where one tectonic plate converges with a second plat ...

ed sediments, fluids derived from the subducted crust and crystallization processes in magma chamber

A magma chamber is a large pool of liquid rock beneath the surface of the Earth. The molten rock, or magma, in such a chamber is less dense than the surrounding country rock, which produces buoyant forces on the magma that tend to drive it u ...

s. 87Sr86Sr ratios of Mount Tambora are similar to those of Mount Rinjani, but lower than those measured at Sangeang Api. Potassium

Potassium is a chemical element; it has Symbol (chemistry), symbol K (from Neo-Latin ) and atomic number19. It is a silvery white metal that is soft enough to easily cut with a knife. Potassium metal reacts rapidly with atmospheric oxygen to ...

levels of Tambora volcanics exceed 3 weight percent, placing them in the shoshonite

Shoshonite is a type of igneous rock. More specifically, it is a potassium-rich variety of basaltic trachyandesite, composed of olivine, augite and plagioclase phenocrysts in a Matrix (geology), groundmass with calcic plagioclase and sanidine and ...

range for alkaline series.

Since the 1815 eruption, the lowermost portion contains deposits of interlayered sequences of lava

Lava is molten or partially molten rock (magma) that has been expelled from the interior of a terrestrial planet (such as Earth) or a Natural satellite, moon onto its surface. Lava may be erupted at a volcano or through a Fissure vent, fractu ...

and pyroclastic

Pyroclast, Pyroclastic or Pyroclastics may refer to:

Geology

* Pyroclast, or airborne volcanic tephra fragments

* Pyroclastic rock, rock fragments produced and ejected by explosive volcanic eruptions

* Pyroclastic cone, landform of ejecta fro ...

materials. Approximately 40% of the layers are represented in the lava flows. Thick scoria

Scoria or cinder is a pyroclastic, highly vesicular, dark-colored volcanic rock formed by ejection from a volcano as a molten blob and cooled in the air to form discrete grains called clasts.Neuendorf, K.K.E., J.P. Mehl, Jr., and J.A. Jackso ...

beds were produced by the fragmentation of lava flows. Within the upper section, the lava is interbedded with scoria, tuff

Tuff is a type of rock made of volcanic ash ejected from a vent during a volcanic eruption. Following ejection and deposition, the ash is lithified into a solid rock. Rock that contains greater than 75% ash is considered tuff, while rock co ...

s, pyroclastic flow

A pyroclastic flow (also known as a pyroclastic density current or a pyroclastic cloud) is a fast-moving current of hot gas and volcanic matter (collectively known as tephra) that flows along the ground away from a volcano at average speeds of b ...

s and pyroclastic fall

A pyroclastic fall deposit is a uniform deposit of material which has been ejected from a volcanic eruption or plume such as an ash fall or tuff. Pyroclastic fallout deposits are a result of:

# Ballistic transport of ejecta such as volcanic bloc ...

s. Tambora has at least 20 parasitic cone

A parasitic cone (also adventive cone, satellite cone, satellitic cone or lateral cone) is the cone-shaped accumulation of volcanic material not part of the central vent of a volcano. It forms from eruptions from fractures on the flank of the ...

s and lava dome

In volcanology, a lava dome is a circular, mound-shaped protrusion resulting from the slow extrusion of viscous lava from a volcano. Dome-building eruptions are common, particularly in convergent plate boundary settings. Around 6% of eruptions ...

s, including ''Doro Afi Toi'', ''Kadiendi Nae'', ''Molo'' and ''Tahe''. The main product of these parasitic vents is basaltic

Basalt (; ) is an aphanitic (fine-grained) extrusive igneous rock formed from the rapid cooling of low-viscosity lava rich in magnesium and iron ( mafic lava) exposed at or very near the surface of a rocky planet or moon. More than 90% ...

lava flow

Lava is molten or partially molten rock (magma) that has been expelled from the interior of a terrestrial planet (such as Earth) or a Natural satellite, moon onto its surface. Lava may be erupted at a volcano or through a Fissure vent, fractu ...

s.

Eruptive history

Radiocarbon dating

Radiocarbon dating (also referred to as carbon dating or carbon-14 dating) is a method for Chronological dating, determining the age of an object containing organic material by using the properties of carbon-14, radiocarbon, a radioactive Isotop ...

has established that Mount Tambora had erupted three times during the current Holocene

The Holocene () is the current geologic time scale, geological epoch, beginning approximately 11,700 years ago. It follows the Last Glacial Period, which concluded with the Holocene glacial retreat. The Holocene and the preceding Pleistocene to ...

epoch

In chronology and periodization, an epoch or reference epoch is an instant in time chosen as the origin of a particular calendar era. The "epoch" serves as a reference point from which time is measured.

The moment of epoch is usually decided b ...

before the 1815 eruption, but the magnitudes of these eruptions are unknown. Their estimated dates are 3910 BC ± 200 years, 3050 BC and 740 AD ± 150 years. An earlier caldera was filled with lava flows starting from 43,000 BC; two pyroclastic eruptions occurred later and formed the Black Sands and Brown Tuff formations, the last of which was emplaced between about 3895 BC and 800 AD.

In 1812, Mount Tambora became highly active, with its maximum eruptive intensity occurring in April 1815. The magnitude was 7 on the Volcanic Explosivity Index

The volcanic explosivity index (VEI) is a scale used to measure the size of explosive volcanic eruptions. It was devised by Christopher G. Newhall of the United States Geological Survey and Stephen Self in 1982.

Volume of products, eruption c ...

(VEI) scale, with a total tephra

Tephra is fragmental material produced by a Volcano, volcanic eruption regardless of composition, fragment size, or emplacement mechanism.

Volcanologists also refer to airborne fragments as pyroclasts. Once clasts have fallen to the ground, ...

ejecta volume of up to 1.8 × 1011 cubic metres. Its eruptive characteristics included central vent and explosive eruptions, pyroclastic flows, tsunami

A tsunami ( ; from , ) is a series of waves in a water body caused by the displacement of a large volume of water, generally in an ocean or a large lake. Earthquakes, volcanic eruptions and underwater explosions (including detonations, ...

s and caldera collapse. This eruption had an effect on global climate. Volcanic activity ceased on 15 July 1815. Activity resumed in August 1819—a small eruption with "flames" and rumbling aftershock

In seismology, an aftershock is a smaller earthquake that follows a larger earthquake, in Epicenter, the same area of the Mainshock, main shock, caused as the displaced Crust (geology), crust adjusts to the effects of the main shock. Large earthq ...

s, and was considered to be part of the 1815 eruption. This eruption was recorded at 2 on the VEI scale.

Around 1880 ± 30 years, eruptions at Mount Tambora have been registered only inside the caldera. It created small lava flows and lava dome extrusions; this was recorded at two on the VEI scale. This eruption created the ''Doro Api Toi'' parasitic cone inside the caldera.

Mount Tambora is still active

Active may refer to:

Music

* ''Active'' (album), a 1992 album by Casiopea

* "Active" (song), a 2024 song by Asake and Travis Scott from Asake's album ''Lungu Boy''

* Active Records, a record label

Ships

* ''Active'' (ship), several com ...

and minor lava domes and flows were extruded on the caldera floor during the 19th and 20th centuries. The last eruption was recorded in 1967. It was a gentle eruption with a VEI of 0, which means it was non-explosive. Another very small eruption was reported in 2011. In August 2011, the alert level for the volcano was raised from level I to level II after increased activity was reported in the caldera, including earthquakes and steam emissions.

1815 eruption

Chronology of the eruption

Before 1815, Mount Tambora had been dormant for several centuries, as hydrousmagma

Magma () is the molten or semi-molten natural material from which all igneous rocks are formed. Magma (sometimes colloquially but incorrectly referred to as ''lava'') is found beneath the surface of the Earth, and evidence of magmatism has also ...

cooled gradually in a closed magma chamber. Inside the chamber, at depths of , cooling and partial crystallization

Crystallization is a process that leads to solids with highly organized Atom, atoms or Molecule, molecules, i.e. a crystal. The ordered nature of a crystalline solid can be contrasted with amorphous solids in which atoms or molecules lack regu ...

of the magma exsolved high-pressure magmatic fluid. Overpressure of the chamber of about was generated as temperatures ranged from . In 1812, the crater began to rumble and generated a dark cloud.

A moderate-sized eruption on 5 April 1815 was followed by thunderous detonation sounds that could be heard in Ternate

Ternate (), also known as the City of Ternate (; ), is the

List of regencies and cities of Indonesia, city with the largest population in the province of North Maluku and an island in the Maluku Islands, Indonesia. It was the ''de facto'' provi ...

on the Molucca Islands

The Maluku Islands ( ; , ) or the Moluccas ( ; ) are an archipelago in the eastern part of Indonesia. Tectonically they are located on the Halmahera Plate within the Molucca Sea Collision Zone. Geographically they are located in West Melanesi ...

, from Mount Tambora. On the morning of 6 April 1815, volcanic ash

Volcanic ash consists of fragments of rock, mineral crystals, and volcanic glass, produced during volcanic eruptions and measuring less than 2 mm (0.079 inches) in diameter. The term volcanic ash is also often loosely used to r ...

began to fall in East Java

East Java (, , ) is a Provinces of Indonesia, province of Indonesia located in the easternmost third of Java island. It has a land border only with the province of Central Java to the west; the Java Sea and the Indian Ocean border its northern ...

, with faint detonation sounds lasting until 10 April.

What was first thought to be the sound of firing guns was heard on 10 and 11 April on Sumatra

Sumatra () is one of the Sunda Islands of western Indonesia. It is the largest island that is fully within Indonesian territory, as well as the list of islands by area, sixth-largest island in the world at 482,286.55 km2 (182,812 mi. ...

island (more than away), Cited by Oppenheimer (2003) and possibly over away in Thailand

Thailand, officially the Kingdom of Thailand and historically known as Siam (the official name until 1939), is a country in Southeast Asia on the Mainland Southeast Asia, Indochinese Peninsula. With a population of almost 66 million, it spa ...

and Laos

Laos, officially the Lao People's Democratic Republic (LPDR), is the only landlocked country in Southeast Asia. It is bordered by Myanmar and China to the northwest, Vietnam to the east, Cambodia to the southeast, and Thailand to the west and ...

.

The eruptions intensified at about 7:00 p.m. on the 10th. Three plumes rose and merged. Pieces of pumice

Pumice (), called pumicite in its powdered or dust form, is a volcanic rock that consists of extremely vesicular rough-textured volcanic glass, which may or may not contain crystals. It is typically light-colored. Scoria is another vesicula ...

of up to in diameter rained down at approximately 8 p.m., followed by ash at around 9–10 p.m. The eruption column

An eruption column or eruption plume is a cloud of super-heated Volcanic ash, ash and tephra suspended in volcanic gas, gases emitted during an explosive eruption, explosive volcanic eruption. The volcanic materials form a vertical column or Plu ...

collapsed, producing hot pyroclastic flow

A pyroclastic flow (also known as a pyroclastic density current or a pyroclastic cloud) is a fast-moving current of hot gas and volcanic matter (collectively known as tephra) that flows along the ground away from a volcano at average speeds of b ...

s that cascaded down the mountain and towards the sea on all sides of the peninsula

A peninsula is a landform that extends from a mainland and is only connected to land on one side. Peninsulas exist on each continent. The largest peninsula in the world is the Arabian Peninsula.

Etymology

The word ''peninsula'' derives , . T ...

, wiping out the village of Tambora. Loud explosions were heard until the next evening, 11 April. The veil of ash spread as far as West Java

West Java (, ) is an Indonesian Provinces of Indonesia, province on the western part of the island of Java, with its provincial capital in Bandung. West Java is bordered by the province of Banten and the country's capital region of Jakarta to t ...

and South Sulawesi

South Sulawesi () is a Provinces of Indonesia, province in the South Peninsula, Sulawesi, southern peninsula of Sulawesi, Indonesia. The Selayar Islands archipelago to the south of Sulawesi is also part of the province. The capital and largest ci ...

, while a "nitrous odor" was noticeable in Batavia. The heavy tephra

Tephra is fragmental material produced by a Volcano, volcanic eruption regardless of composition, fragment size, or emplacement mechanism.

Volcanologists also refer to airborne fragments as pyroclasts. Once clasts have fallen to the ground, ...

-tinged rain did not recede until 17 April. Analysis of various sites on Mount Tambora using ground-penetrating radar has revealed alternations of pumice and ash deposits covered by the pyroclastic surge and flow sediments that vary in thickness regionally.

The eruption is estimated to have had a Volcanic Explosivity Index

The volcanic explosivity index (VEI) is a scale used to measure the size of explosive volcanic eruptions. It was devised by Christopher G. Newhall of the United States Geological Survey and Stephen Self in 1982.

Volume of products, eruption c ...

of 7. It had 4–10 times the energy of the 1883 Krakatoa eruption. An estimated of pyroclastic trachyandesite

Trachyandesite is an extrusive igneous rock with a composition between trachyte and andesite. It has little or no free quartz, but is dominated by sodic plagioclase and alkali feldspar. It is formed from the cooling of lava enriched in alkal ...

was ejected, weighing approximately 1.4×1014 kg. This has left a caldera measuring across and deep. The density of fallen ash in Makassar

Makassar ( ), formerly Ujung Pandang ( ), is the capital of the Indonesian Provinces of Indonesia, province of South Sulawesi. It is the largest city in the region of Eastern Indonesia and the country's fifth-largest urban center after Jakarta, ...

was 636 kg/m3. Before the explosion, Mount Tambora was approximately high, one of the tallest peaks in the Indonesian archipelago. After the eruption of 1815, the maximum elevation was reduced to .

The 1815 Tambora eruption is the largest and most devastating observed eruption in recorded history; a comparison with other major eruptions is listed below. The explosion was heard or away, and ash deposits were registered at a distance of at least . A pitch of darkness was observed as far away as from the mountain summit for up to two days. Pyroclastic flows spread to distances of about from the summit and an estimated 9.3–11.8 × 1013 g of stratospheric sulfate aerosols were generated by the eruption.

Aftermath

The island's entire vegetation was destroyed as uprooted trees, mixed with pumice ash, washed into the sea and formed rafts of up to across. Onepumice raft

A pumice raft is a floating raft of pumice created by some eruptions of submarine volcanoes or coastal subaerial volcanoes.

Pumice rafts have unique characteristics, such as the highest surface-area-to-volume ratio known for any rock type, long ...

was found in the Indian Ocean

The Indian Ocean is the third-largest of the world's five oceanic divisions, covering or approximately 20% of the water area of Earth#Surface, Earth's surface. It is bounded by Asia to the north, Africa to the west and Australia (continent), ...

, near Calcutta

Kolkata, also known as Calcutta (List of renamed places in India#West Bengal, its official name until 2001), is the capital and largest city of the Indian States and union territories of India, state of West Bengal. It lies on the eastern ba ...

, on 1 and 3 October 1815. Clouds of thick ash still covered the summit on 23 April. Explosions ceased on 15 July, although smoke emissions were still observed as late as 23 August. Flames and rumbling aftershocks were reported in August 1819, four years after the event.

A moderate tsunami

A tsunami ( ; from , ) is a series of waves in a water body caused by the displacement of a large volume of water, generally in an ocean or a large lake. Earthquakes, volcanic eruptions and underwater explosions (including detonations, ...

struck the shores of various islands in the Indonesian archipelago on 10 April, with waves reaching in Sanggar at around 10 p.m. A tsunami causing waves of was reported in Besuki, East Java

East Java (, , ) is a Provinces of Indonesia, province of Indonesia located in the easternmost third of Java island. It has a land border only with the province of Central Java to the west; the Java Sea and the Indian Ocean border its northern ...

before midnight and another exceeded in the Molucca Islands

The Maluku Islands ( ; , ) or the Moluccas ( ; ) are an archipelago in the eastern part of Indonesia. Tectonically they are located on the Halmahera Plate within the Molucca Sea Collision Zone. Geographically they are located in West Melanesi ...

. The eruption column

An eruption column or eruption plume is a cloud of super-heated Volcanic ash, ash and tephra suspended in volcanic gas, gases emitted during an explosive eruption, explosive volcanic eruption. The volcanic materials form a vertical column or Plu ...

reached the stratosphere

The stratosphere () is the second-lowest layer of the atmosphere of Earth, located above the troposphere and below the mesosphere. The stratosphere is composed of stratified temperature zones, with the warmer layers of air located higher ...

at an altitude of more than . Coarser ash particles fell one to two weeks after the eruptions, while finer particles stayed in the atmosphere for months to years at an altitude of . There are various estimates of the volume of ash emitted: a recent study estimates a dense-rock equivalent

Dense-rock equivalent (DRE) is a volcanologic calculation used to estimate volcanic eruption volume. One of the widely accepted measures of the size of a historic or prehistoric eruption is the volume of magma ejected as pumice and volcanic ash, k ...

volume for the ash of and a dense-rock equivalent volume of for the pyroclastic flows. Longitudinal winds spread these fine particles around the globe, creating optical phenomena. Between 28 June and 2 July, and between 3 September and 7 October 1815, prolonged and brilliantly coloured sunsets and twilights were frequently seen in London. Most commonly, pink or purple colours appeared above the horizon at twilight and orange or red near the horizon.

Fatalities

The number of fatalities has been estimated by various sources since the 19th century. Swiss botanistHeinrich Zollinger

Heinrich Zollinger (22 March 1818 – 19 May 1859) was a Swiss botanist.

Zollinger was born in Feuerthalen, Switzerland.

From 1837 to 1838 he studied botany at the University of Geneva under Augustin and Alphonse Pyramus de Candolle, but ha ...

travelled to Sumbawa in 1847 and recollected witness accounts about the 1815 eruption of Tambora. In 1855, he published estimates of directly killed people at 10,100, mostly from pyroclastic flows. A further 37,825 died from starvation on Sumbawa

Sumbawa, is an Indonesian island, located in the middle of the Lesser Sunda Islands chain, with Lombok to the west, Flores to the east, and Sumba further to the southeast. Along with Lombok, it forms the province of West Nusa Tenggara, but th ...

island.

On Lombok

Lombok, is an island in West Nusa Tenggara province, Indonesia. It forms part of the chain of the Lesser Sunda Islands, with the Lombok Strait separating it from Bali to the west and the Alas Strait between it and Sumbawa to the east. It is rou ...

, another 10,000 died from disease and hunger.Zollinger (1855): ''Besteigung des Vulkans Tamboro auf der Insel Sumbawa und Schiderung der Eruption desselben im Jahren 1815'', Winterthur: Zurcher and Fürber, Wurster and Co., cited by Oppenheimer (2003). Petroeschevsky (1949) estimated that about 48,000 and 44,000 people were killed on Sumbawa and Lombok, respectively., cited by Oppenheimer (2003). Several authors have used Petroeschevsky's figures, such as Stothers (1984), who estimated 88,000 deaths in total. Tanguy et al. (1998) considered Petroeschevsky's figures based on untraceable sources, so developed an estimate based solely on two primary sources: Zollinger, who spent several months on Sumbawa after the eruption, and the notes of Sir Stamford Raffles

Sir Thomas Stamford Bingley Raffles (5 July 1781 – 5 July 1826) was a British colonial official who served as the governor of the Dutch East Indies between 1811 and 1816 and lieutenant-governor of Bencoolen between 1818 and 1824. Raffles ...

, Governor-General of the Dutch East Indies during the event. Tanguy pointed out that there may have been additional victims on Bali

Bali (English:; Balinese language, Balinese: ) is a Provinces of Indonesia, province of Indonesia and the westernmost of the Lesser Sunda Islands. East of Java and west of Lombok, the province includes the island of Bali and a few smaller o ...

and East Java

East Java (, , ) is a Provinces of Indonesia, province of Indonesia located in the easternmost third of Java island. It has a land border only with the province of Central Java to the west; the Java Sea and the Indian Ocean border its northern ...

because of famine and disease, and estimated 11,000 deaths from direct volcanic action and 49,000 from post-eruption famine and epidemics. Oppenheimer (2003) estimated at least 71,000 deaths, and numbers as high as 117,000 have been proposed.

= Global effects

= The 1815 eruption released 10 to 120 million tons of

The 1815 eruption released 10 to 120 million tons of sulfur

Sulfur ( American spelling and the preferred IUPAC name) or sulphur ( Commonwealth spelling) is a chemical element; it has symbol S and atomic number 16. It is abundant, multivalent and nonmetallic. Under normal conditions, sulfur atoms ...

into the stratosphere

The stratosphere () is the second-lowest layer of the atmosphere of Earth, located above the troposphere and below the mesosphere. The stratosphere is composed of stratified temperature zones, with the warmer layers of air located higher ...

, causing a global climate anomaly. Different methods have been used to estimate the ejected sulfur mass: the petrological

Petrology () is the branch of geology that studies rocks, their mineralogy, composition, texture, structure and the conditions under which they form. Petrology has three subdivisions: igneous, metamorphic, and sedimentary petrology. Igneous an ...

method, an optical depth measurement based on anatomical

Anatomy () is the branch of morphology concerned with the study of the internal structure of organisms and their parts. Anatomy is a branch of natural science that deals with the structural organization of living things. It is an old scien ...

observations, and the polar

Polar may refer to:

Geography

* Geographical pole, either of the two points on Earth where its axis of rotation intersects its surface

** Polar climate, the climate common in polar regions

** Polar regions of Earth, locations within the polar circ ...

ice core

An ice core is a core sample that is typically removed from an ice sheet or a high mountain glacier

A glacier (; or ) is a persistent body of dense ice, a form of rock, that is constantly moving downhill under its own weight. A glacier ...

sulfate concentration method, which calibrated against cores from Greenland

Greenland is an autonomous territory in the Danish Realm, Kingdom of Denmark. It is by far the largest geographically of three constituent parts of the kingdom; the other two are metropolitan Denmark and the Faroe Islands. Citizens of Greenlan ...

and Antarctica

Antarctica () is Earth's southernmost and least-populated continent. Situated almost entirely south of the Antarctic Circle and surrounded by the Southern Ocean (also known as the Antarctic Ocean), it contains the geographic South Pole. ...

.

In the spring and summer of 1816, a persistent stratospheric sulfate aerosol

An aerosol is a suspension (chemistry), suspension of fine solid particles or liquid Drop (liquid), droplets in air or another gas. Aerosols can be generated from natural or Human impact on the environment, human causes. The term ''aerosol'' co ...

veil, described then as a "dry fog", was observed in the northeastern United States. It was not dispersed by wind or rainfall, and it reddened and dimmed sunlight to an extent that sunspots were visible to the naked eye. Areas of the northern hemisphere

The Northern Hemisphere is the half of Earth that is north of the equator. For other planets in the Solar System, north is defined by humans as being in the same celestial sphere, celestial hemisphere relative to the invariable plane of the Solar ...

suffered extreme weather conditions and 1816 became known as the "year without a summer

The year 1816 is known as the Year Without a Summer because of severe climate abnormalities that caused average global temperatures to decrease by . Summer temperatures in Europe were the coldest of any on record between 1766 and 2000, resultin ...

". Average global temperatures decreased about , enough to cause significant agricultural problems around the globe. After 4 June 1816, when there were frosts in Connecticut

Connecticut ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It borders Rhode Island to the east, Massachusetts to the north, New York (state), New York to the west, and Long Island Sound to the south. ...

, cold weather expanded over most of New England

New England is a region consisting of six states in the Northeastern United States: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. It is bordered by the state of New York (state), New York to the west and by the ...

. On 6 June 1816, it snowed in Albany, New York

Albany ( ) is the List of capitals in the United States, capital city of the U.S. state of New York (state), New York. It is located on the west bank of the Hudson River, about south of its confluence with the Mohawk River. Albany is the oldes ...

and Dennysville, Maine

Dennysville is a town in Washington County, Maine, United States. The population was 300 at the 2020 census.

History

Dennysville takes its name from the Dennys River. It was first settled by a group of sixteen men who came by boat from Hingha ...

. Similar conditions persisted for at least three months, ruining most crops across North America while Canada experienced extreme cold. Snow fell until 10 June near Quebec City

Quebec City is the capital city of the Provinces and territories of Canada, Canadian province of Quebec. As of July 2021, the city had a population of 549,459, and the Census Metropolitan Area (including surrounding communities) had a populati ...

, accumulating to .

That year became the second-coldest year in the northern hemisphere since 1400, while the 1810s were the coldest decade on record, a result of Tambora's eruption and other suspected volcanic events between 1809 and 1810. (See sulfate concentration chart.) Surface-temperature anomalies during the summers of 1816, 1817 and 1818 were −0.51, −0.44 and −0.29 °C, respectively. Along with a cooler summer, parts of Europe experienced a stormier winter, and the Elbe

The Elbe ( ; ; or ''Elv''; Upper Sorbian, Upper and , ) is one of the major rivers of Central Europe. It rises in the Giant Mountains of the northern Czech Republic before traversing much of Bohemia (western half of the Czech Republic), then Ge ...

and Ohře River

The Ohře (), also known in English and German as Eger (), is a river in Germany and the Czech Republic, a left tributary of the Elbe River. It flows through the Bavarian district of Upper Franconia in Germany, and through the Karlovy Vary and Ú ...

s froze over for twelve days in February 1816. As a result, prices of wheat

Wheat is a group of wild and crop domestication, domesticated Poaceae, grasses of the genus ''Triticum'' (). They are Agriculture, cultivated for their cereal grains, which are staple foods around the world. Well-known Taxonomy of wheat, whe ...

, rye

Rye (''Secale cereale'') is a grass grown extensively as a grain, a cover crop and a forage crop. It is grown principally in an area from Eastern and Northern Europe into Russia. It is much more tolerant of cold weather and poor soil than o ...

, barley

Barley (), a member of the grass family, is a major cereal grain grown in temperate climates globally. It was one of the first cultivated grains; it was domesticated in the Fertile Crescent around 9000 BC, giving it nonshattering spikele ...

and oats

The oat (''Avena sativa''), sometimes called the common oat, is a species of cereal grain grown for its seed, which is known by the same name (usually in the plural). Oats appear to have been domesticated as a secondary crop, as their seed ...

rose dramatically by 1817.

This climate anomaly has been cited as a reason for the severity of the 1816–19 typhus

Typhus, also known as typhus fever, is a group of infectious diseases that include epidemic typhus, scrub typhus, and murine typhus. Common symptoms include fever, headache, and a rash. Typically these begin one to two weeks after exposu ...

epidemic in southeast Europe and the eastern Mediterranean. Large numbers of livestock died in New England

New England is a region consisting of six states in the Northeastern United States: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. It is bordered by the state of New York (state), New York to the west and by the ...

during the winter of 1816–1817, while cool temperatures and heavy rains led to failed harvests in the British Isles. Families in Wales

Wales ( ) is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is bordered by the Irish Sea to the north and west, England to the England–Wales border, east, the Bristol Channel to the south, and the Celtic ...

travelled long distances as refugees, begging for food. Famine was prevalent in north and southwest Ireland, following the failure of wheat, oat and potato harvests. The crisis was severe in Germany, where food prices rose sharply. Demonstrations at grain markets and bakeries, followed by riots, arson and looting, took place in many European cities. It was the worst famine of the 19th century.

Culture

A human settlement obliterated by the Tambora eruption was discovered in 2004. That summer, a team led by Haraldur Sigurðsson with scientists from the

A human settlement obliterated by the Tambora eruption was discovered in 2004. That summer, a team led by Haraldur Sigurðsson with scientists from the University of Rhode Island

The University of Rhode Island (URI) is a public land-grant research university with its main campus in Kingston, Rhode Island, United States. It is the flagship public research as well as the land-grant university of Rhode Island. The univer ...

, the University of North Carolina at Wilmington

The University of North Carolina Wilmington, or University of North Carolina at Wilmington, (UNC Wilmington or UNCW) is a public research university in Wilmington, North Carolina. It is part of the University of North Carolina system and enrol ...

and the Indonesian Directorate of Volcanology began an archaeological dig

In archaeology, excavation is the exposure, processing and recording of archaeological remains. An excavation site or "dig" is the area being studied. These locations range from one to several areas at a time during a project and can be condu ...

in Tambora. Over six weeks, they unearthed evidence of habitation about west of the caldera, deep in jungle, from shore. The team excavated of deposits of pumice and ash. The scientists used ground-penetrating radar

Ground-penetrating radar (GPR) is a geophysical method that uses radar pulses to image the subsurface. It is a non-intrusive method of surveying the sub-surface to investigate underground utilities such as concrete, asphalt, metals, pipes, cables ...

to locate a small buried house which contained the remains of two adults, bronze bowls, ceramic pots, iron tools and other artifacts. Tests revealed that objects had been carbonized by the heat of the magma

Magma () is the molten or semi-molten natural material from which all igneous rocks are formed. Magma (sometimes colloquially but incorrectly referred to as ''lava'') is found beneath the surface of the Earth, and evidence of magmatism has also ...

. Sigurdsson dubbed the find the "Pompeii

Pompeii ( ; ) was a city in what is now the municipality of Pompei, near Naples, in the Campania region of Italy. Along with Herculaneum, Stabiae, and Villa Boscoreale, many surrounding villas, the city was buried under of volcanic ash and p ...

of the East", and media reports referred to the "Lost Kingdom of Tambora". Sigurdsson intended to return to Tambora in 2007 to search for the rest of the villages, and hopefully to find a palace. Many villages in the area had converted to Islam in the 17th century, but the structures uncovered so far do not show Islamic influence.

Based on the artifacts found, such as bronzeware and finely decorated china possibly of Vietnam

Vietnam, officially the Socialist Republic of Vietnam (SRV), is a country at the eastern edge of mainland Southeast Asia, with an area of about and a population of over 100 million, making it the world's List of countries and depende ...

ese or Cambodia

Cambodia, officially the Kingdom of Cambodia, is a country in Southeast Asia on the Mainland Southeast Asia, Indochinese Peninsula. It is bordered by Thailand to the northwest, Laos to the north, and Vietnam to the east, and has a coastline ...

n origin, the team concluded that the people were well-off traders. The Sumbawa people were known in the East Indies

The East Indies (or simply the Indies) is a term used in historical narratives of the Age of Discovery. The ''Indies'' broadly referred to various lands in Eastern world, the East or the Eastern Hemisphere, particularly the islands and mainl ...

for their horses, honey, sappan wood (for producing red dye), and sandalwood

Sandalwood is a class of woods from trees in the genus ''Santalum''. The woods are heavy, yellow, and fine-grained, and, unlike many other aromatic woods, they retain their fragrance for decades. Sandalwood oil is extracted from the woods. Sanda ...

(for incense

Incense is an aromatic biotic material that releases fragrant smoke when burnt. The term is used for either the material or the aroma. Incense is used for aesthetic reasons, religious worship, aromatherapy, meditation, and ceremonial reasons. It ...

and medications). The area was thought to be highly productive agriculturally.

The language of the Tambora people was lost with the eruption. Linguists have examined remnant lexical material, such as records by Zollinger and Raffles, and established that Tambora was not an Austronesian

Austronesian may refer to:

*The Austronesian languages

*The historical Austronesian peoples

The Austronesian people, sometimes referred to as Austronesian-speaking peoples, are a large group of peoples who have settled in Taiwan, maritime Sout ...

language, as would be expected in the area, but possibly a language isolate

A language isolate is a language that has no demonstrable genetic relationship with any other languages. Basque in Europe, Ainu and Burushaski in Asia, Sandawe in Africa, Haida and Zuni in North America, Kanoê in South America, and Tiwi ...

, or perhaps a member of one of the families of Papuan language

The Papuan languages are the non-Austronesian languages spoken on the western Pacific island of New Guinea, as well as neighbouring islands in Indonesia, Solomon Islands, and East Timor. It is a strictly geographical grouping, and does not imply a ...

s found or more to the east.

The eruption is captured in latter-day folklore, which explains the cataclysm as divine retribution. A local ruler is said to have incurred the wrath of Allah

Allah ( ; , ) is an Arabic term for God, specifically the God in Abrahamic religions, God of Abraham. Outside of the Middle East, it is principally associated with God in Islam, Islam (in which it is also considered the proper name), althoug ...

by feeding dog meat to a ''hajji

Hajji (; sometimes spelled Hajjeh, Hadji, Haji, Alhaji, Al-Hadj, Al-Haj or El-Hajj) is an honorific title which is given to a Muslim who has successfully completed the Hajj to Mecca.

Etymology

''Hajji'' is derived from the Arabic ' (), which i ...

'' and killing him. This is expressed in a poem written around 1830:

Ecosystem

A team led by the Swiss botanist

A team led by the Swiss botanist Heinrich Zollinger

Heinrich Zollinger (22 March 1818 – 19 May 1859) was a Swiss botanist.

Zollinger was born in Feuerthalen, Switzerland.

From 1837 to 1838 he studied botany at the University of Geneva under Augustin and Alphonse Pyramus de Candolle, but ha ...

arrived on Sumbawa in 1847. Zollinger sought to study the area of eruption and its effects on the local ecosystem

An ecosystem (or ecological system) is a system formed by Organism, organisms in interaction with their Biophysical environment, environment. The Biotic material, biotic and abiotic components are linked together through nutrient cycles and en ...

. He was the first person after the eruption to ascend the summit, which was still covered by smoke. As Zollinger climbed, his feet sank several times through a thin surface crust into a warm layer of powder-like sulfur

Sulfur ( American spelling and the preferred IUPAC name) or sulphur ( Commonwealth spelling) is a chemical element; it has symbol S and atomic number 16. It is abundant, multivalent and nonmetallic. Under normal conditions, sulfur atoms ...

. Some vegetation had regrown, including trees on the lower slope. A ''Casuarina

''Casuarina'', also known as she-oak, Australian pine and native pine, is a genus of flowering plants in the family Casuarinaceae, and is native to Australia, the Indian subcontinent, Southeast Asia, islands of the western Pacific Ocean, and e ...

'' forest was noted at , while several ''Imperata cylindrica

''Imperata cylindrica'' (commonly known as cogongrass or kunai grass ) is a species of Perennial plant, perennial rhizomatous grass native to tropical and subtropical Asia, Micronesia, Melanesia, Australia, Africa, and Southern Europe. It has al ...

'' grassland

A grassland is an area where the vegetation is dominance (ecology), dominated by grasses (Poaceae). However, sedge (Cyperaceae) and rush (Juncaceae) can also be found along with variable proportions of legumes such as clover, and other Herbaceo ...

s were also found.Zollinger (1855) cited by Trainor (2002). In August 2015 a team of Georesearch Volcanedo Germany followed the way used by Zollinger and explored this way for the first time since 1847. Because of the length of the distance to be travelled on foot, the partly very high temperatures and the lack of water it was a particular challenge for the team of Georesearch Volcanedo.

Resettlement of the area began in 1907, and a coffee plantation was established in the 1930s in the Pekat village on the northwestern slope. A dense rain forest

Rainforests are forests characterized by a closed and continuous tree Canopy (biology), canopy, moisture-dependent vegetation, the presence of epiphytes and lianas and the absence of wildfire. Rainforests can be generally classified as tropi ...

of ''Duabanga moluccana

''Duabanga moluccana'' is a species of tree native to Indonesia and surrounding areas. Its common names include ''kalanggo'' (Indonesia) ''loktob or karay'' (Philippines) and ''magas'' (Malaysia

Malaysia is a country in Southeast Asia. F ...

'' trees had grown at an altitude of . It covers an area up to . The rain forest was discovered by a Dutch team, led by Koster and de Voogd in 1933. From their accounts, they started their journey in a "fairly barren, dry and hot country", and then they entered "a mighty jungle" with "huge, majestic forest giants". At , the trees became thinner in shape. Above , they found ''Dodonaea viscosa

''Dodonaea viscosa'', also known as the broadleaf hopbush, is a species of flowering plant in the ''Dodonaea'' (hopbush) genus that has a cosmopolitan distribution in Tropics, tropical, Subtropics, subtropical and warm temperate regions of Africa ...

'' flowering plants dominated by ''Casuarina'' trees. On the summit was sparse ''Edelweiss

''Leontopodium nivale'', commonly called edelweiss () ( ; or ), is a mountain flower belonging to the daisy or sunflower family Asteraceae. The plant prefers rocky limestone places at about altitude. It is a non-toxic plant. Its leaves and f ...

'' and ''Wahlenbergia

''Wahlenbergia'' is a genus of around 260 species of flowering plants in the Family (biology), family Campanulaceae. Plants in this genus are Perennial plant, perennial or Annual plant, annual Herbaceous plant, herbs with simple leaves and blue t ...

''.

An 1896 survey records 56 species of birds including the crested white-eye. Several other zoological surveys followed and found other bird species, with over 90 bird species discoveries in this period, including yellow-crested cockatoo

The yellow-crested cockatoo (''Cacatua sulphurea'') also known as the lesser sulphur-crested cockatoo, is a medium-sized (about 34-cm-long) cockatoo with white plumage, bluish-white bare orbital skin, grey feet, a black bill, and a retractile ye ...

s, Zoothera thrushes, Hill myna

''Gracula'' is a genus of mynas, tropical members of the starling family of birds found in southern Asia and introduced to Florida in the United States.

Taxonomy

The genus ''Gracula'' was introduced in 1758 by the Swedish naturalist Carl Linna ...

s, green junglefowl

The green junglefowl (''Gallus varius''), also known as Javan junglefowl, forktail or green Javanese junglefowl, is the most distantly related and the first to diverge at least 4 million years ago among the four species of the junglefowl. ...

and rainbow lorikeet

The rainbow lorikeet (''Trichoglossus moluccanus'') is a species of parrot found in Australia. It is common along the eastern seaboard, from northern Queensland to South Australia. Its habitat is rainforest, coastal bush and woodland areas. Six ...

s are hunted for the cagebird trade by the local people. Orange-footed scrubfowl

The orange-footed scrubfowl (''Megapodius reinwardt''), also known as orange-footed megapode or just scrubfowl, is a small megapode of the family Megapodiidae native to many islands in the Lesser Sunda Islands as well as southern New Guinea and n ...

are hunted for food. This bird exploitation has resulted in population declines, and the yellow-crested cockatoo is nearing extinction on Sumbawa island.

A commercial logging

Logging is the process of cutting, processing, and moving trees to a location for transport. It may include skidder, skidding, on-site processing, and loading of trees or trunk (botany), logs onto logging truck, trucks The company holds a timber-cutting concession for an area of , or 25% of the total area. Another part of the rain forest is used as a hunting ground. In between the hunting ground and the logging area, there is a designated wildlife reserve where deer,

WikiSatellite view at WikiMapia

google/docs

{{DEFAULTSORT:Tambora, Mount Stratovolcanoes of Indonesia Subduction volcanoes Volcanoes of Sumbawa Active volcanoes of Indonesia VEI-7 volcanoes Calderas of Indonesia Two-thousanders of Asia Pleistocene stratovolcanoes Holocene stratovolcanoes Drainage basins of Sumbawa

water buffalo

The water buffalo (''Bubalus bubalis''), also called domestic water buffalo, Asian water buffalo and Asiatic water buffalo, is a large bovid originating in the Indian subcontinent and Southeast Asia. Today, it is also kept in Italy, the Balkans ...

s, wild pigs, bats, flying fox

''Pteropus'' (suborder Yinpterochiroptera) is a genus of megabats which are among the largest bats in the world. They are commonly known as fruit bats or flying foxes, among other colloquial names.

They live in South Asia, Southeast Asia, Aust ...

es and species of reptiles and birds can be found. In 2015, the conservation area protecting the mountain's ecosystem was upgraded to a national park

A national park is a nature park designated for conservation (ethic), conservation purposes because of unparalleled national natural, historic, or cultural significance. It is an area of natural, semi-natural, or developed land that is protecte ...

.

Exploration of the caldera floor

Zollinger (1847), van Rheden (1913) and W. A. Petroeschevsky (1947) could only observe the caldera floor from the crater rim. In 2013, a German research team (Georesearch Volcanedo Germany) for the first time carried out a longer expedition into this caldera, about deep, and with the help of a native team climbed down the southern caldera wall, reaching the caldera floor while experiencing extreme conditions. The team stayed in the caldera for nine days. People had reached the caldera floor only in a few cases as the descent down the steep wall is difficult and dangerous, subject to earthquakes, landslides and rockfalls. Moreover, only relatively short stays on the caldera floor had been possible because of logistical problems, so that extensive studies had been impossible. The investigation program of Georesearch Volcanedo on the caldera floor included researching the visible effects of smaller eruptions which had taken place since 1815, gas measurements, studies of flora and fauna and measurement of weather data. Especially striking was the relatively high activity of Doro Api Toi ("Gunung Api Kecil" means "small volcano") in the southern part of the caldera and the gases escaping under high pressure on the lower north-east wall. Besides the team discovered near the Doro Api Toi a lavadome which had not yet been mentioned in scientific studies. The team called this new discovery "Adik Api Toi (Indonesian "adik": younger brother). Later this lavadome was called by the Indonesians "Doro Api Bou" ("new volcano"). This lavadome probably appeared in 2011/2012 when there was an increased seismic activity and probably volcanic activity on the caldera floor (there is no exact information about the caldera floor at that time). In 2014 the same research team carried out a further expedition into the caldera and set a new record: over 12 days the investigations of 2013 were continued.

Monitoring

Indonesia's population has been increasing rapidly since the 1815 eruption. In 2020, the population of the country reached 270 million people, of which 56% concentrated on the island ofJava

Java is one of the Greater Sunda Islands in Indonesia. It is bordered by the Indian Ocean to the south and the Java Sea (a part of Pacific Ocean) to the north. With a population of 156.9 million people (including Madura) in mid 2024, proje ...

. An event as significant as the 1815 eruption would impact about eight million people.

Seismic activity

An earthquakealso called a quake, tremor, or tembloris the shaking of the Earth's surface resulting from a sudden release of energy in the lithosphere that creates seismic waves. Earthquakes can range in intensity, from those so weak they ...

in Indonesia is monitored by the Directorate of Volcanology and Geological Hazard Mitigation with the monitoring post for Mount Tambora located at Doro Peti village. They focus on seismic and tectonic

Tectonics ( via Latin ) are the processes that result in the structure and properties of the Earth's crust and its evolution through time. The field of ''planetary tectonics'' extends the concept to other planets and moons.

These processes ...

activity by using a seismograph

A seismometer is an instrument that responds to ground displacement and shaking such as caused by quakes, volcanic eruptions, and explosions. They are usually combined with a timing device and a recording device to form a seismograph. The out ...

. There has been no significant increase in seismic activity since the 1880 eruption. Monitoring is continuously performed inside the caldera, with a focus on the parasitic cone ''Doro Api Toi''.

The directorate created a disaster mitigation

Mitigation is the reduction of something harmful that has occurred or the reduction of its harmful effects. It may refer to measures taken to reduce the harmful effects of hazards that remain ''in potentia'', or to manage harmful incidents that ...

map for Mount Tambora, which designates two zones for an eruption: a dangerous zone and a cautious zone. The dangerous zone identifies areas that would be directly affected by pyroclastic flows, lava flows or pyroclastic falls. It includes areas such as the caldera and its surroundings, a span of up to where habitation is prohibited. The cautious zone consists of land that might be indirectly affected, either by lahar

A lahar (, from ) is a violent type of mudflow or debris flow composed of a slurry of Pyroclastic rock, pyroclastic material, rocky debris and water. The material flows down from a volcano, typically along a valley, river valley.

Lahars are o ...

flows and other pumice stones. The size of the cautious area is , and includes Pasanggrahan, Doro Peti, Rao, Labuan Kenanga, Gubu Ponda, Kawindana Toi and Hoddo villages. A river, called Guwu, at the southern and northwest part of the mountain is also included in the cautious zone.

Panorama

References

Notes

Bibliography

*External links

* *WikiSatellite view at WikiMapia

google/docs

{{DEFAULTSORT:Tambora, Mount Stratovolcanoes of Indonesia Subduction volcanoes Volcanoes of Sumbawa Active volcanoes of Indonesia VEI-7 volcanoes Calderas of Indonesia Two-thousanders of Asia Pleistocene stratovolcanoes Holocene stratovolcanoes Drainage basins of Sumbawa