Talbot Mundy on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Talbot Mundy (born William Lancaster Gribbon, 23 April 1879 – 5 August 1940) was an English writer of

In February 1904 he arrived in

In February 1904 he arrived in

In December 1918, Mundy and his wife had visited

In December 1918, Mundy and his wife had visited

It was also on Staten Island that he began drawing upon his experiences of Palestine for a series of novelettes set in the region that featured a new protagonist, James Schuyler Grim, or "Jimgrim". As created by Mundy, Jimgrim was an American who had been recruited by the British intelligence services because of his in-depth knowledge of Arab life. Mundy claimed that Jimgrim was based on a real individual, whose identity he refused to reveal, while later biographer Brian Taves has suggested that the character was heavily influenced by T. E. Lawrence. The first of these Jimgrim stories, "The Adventure of El-Kerak", appeared in ''Adventure'' in November 1921; the second, "Under the

It was also on Staten Island that he began drawing upon his experiences of Palestine for a series of novelettes set in the region that featured a new protagonist, James Schuyler Grim, or "Jimgrim". As created by Mundy, Jimgrim was an American who had been recruited by the British intelligence services because of his in-depth knowledge of Arab life. Mundy claimed that Jimgrim was based on a real individual, whose identity he refused to reveal, while later biographer Brian Taves has suggested that the character was heavily influenced by T. E. Lawrence. The first of these Jimgrim stories, "The Adventure of El-Kerak", appeared in ''Adventure'' in November 1921; the second, "Under the

In 1922, Mundy resigned from the Mother Church of Christian Science. He was increasingly interested in

In 1922, Mundy resigned from the Mother Church of Christian Science. He was increasingly interested in  Mundy followed this with ''Om: The Secret of Ahbor Valley'', which was serialised in ''Adventure'' from October to November 1924, before publication by Bobbs-Merrill. The characters were based upon individuals that he knew at Lomaland, and the story expounded Theosophical ideas regarding the Masters and the existence of a universal "Ancient Wisdom". ''Adventure'' included a disclaimer at the start of the story stating that they did not endorse the esoteric movement. Ellis described the work as Mundy's "most significant novel", and his "literary masterpiece", while for Taves, it was "his most distinctly literary book, surpassing earlier novels by exhibiting a maturing skill in choice of language, plot structure, theme, depth of character." Mundy received hundreds of letters praising the work, and it also received good critical reviews from press. It proved popular among Theosophists, with Tingley asking Mundy if he would adapt it for one of her theaters. The British edition underwent six reprints in quick succession, while Swedish and German translations were soon commissioned for publication. At the prompting of several letters, Mundy began work on a sequel, ''Ramsden'', which appeared in ''Adventure'' in June 1926 before being published by Bobbs-Merrill under the title of ''The Devils Guard''. Upon publication it received good reviews. A third instalment in the trilogy, ''The Red Flame of Erinpura'', appeared in ''Adventure'' in 1927. Taves later noted that these three works reflected Theosophy's "most direct influence upon Mundy's writing", adding that in looking to Asia not only "for exoticism, but for wisdom and an alternative mode of living superior to Western habits", they "reinvigorated and revitalized fantasy-adventure literature".

Mundy then moved towards

Mundy followed this with ''Om: The Secret of Ahbor Valley'', which was serialised in ''Adventure'' from October to November 1924, before publication by Bobbs-Merrill. The characters were based upon individuals that he knew at Lomaland, and the story expounded Theosophical ideas regarding the Masters and the existence of a universal "Ancient Wisdom". ''Adventure'' included a disclaimer at the start of the story stating that they did not endorse the esoteric movement. Ellis described the work as Mundy's "most significant novel", and his "literary masterpiece", while for Taves, it was "his most distinctly literary book, surpassing earlier novels by exhibiting a maturing skill in choice of language, plot structure, theme, depth of character." Mundy received hundreds of letters praising the work, and it also received good critical reviews from press. It proved popular among Theosophists, with Tingley asking Mundy if he would adapt it for one of her theaters. The British edition underwent six reprints in quick succession, while Swedish and German translations were soon commissioned for publication. At the prompting of several letters, Mundy began work on a sequel, ''Ramsden'', which appeared in ''Adventure'' in June 1926 before being published by Bobbs-Merrill under the title of ''The Devils Guard''. Upon publication it received good reviews. A third instalment in the trilogy, ''The Red Flame of Erinpura'', appeared in ''Adventure'' in 1927. Taves later noted that these three works reflected Theosophy's "most direct influence upon Mundy's writing", adding that in looking to Asia not only "for exoticism, but for wisdom and an alternative mode of living superior to Western habits", they "reinvigorated and revitalized fantasy-adventure literature".

Mundy then moved towards

After the failings of the Mexican oil expedition, Mundy left for New York City in June 1928. He officially separated from Ames the following month, leaving his Tilgaun home to her. In the city he embarked on a relationship with Theda Conkey Webber—a woman he had met in the autumn of 1927—and she shortly after legally changed her name to Dawn Allen. In New York, Mundy had resumed his friendship with Natacha Rambova, whom he had first met at Point Loma. Through her he was introduced to the spirit medium George Wehner, who helped develop Mundy's interest in Spiritualism. Mundy then wrote an introduction to Wehner's autobiography, ''A Curious Life'', reflecting his own growing interest in Spiritualism. Both Rambova and Mundy and Dawn moved into the Master Apartments building, which rented its rooms to a large number of artists and writers. Mundy became involved in Nicholas Roerich's museum, which was located in the building, and travelled to London in order to convince the authorities to permit Roerich's expedition to India and in to the Himalayas; they had initially been hesitant that Roerich—who was Russian by birth—may have been an intelligence agent for the

After the failings of the Mexican oil expedition, Mundy left for New York City in June 1928. He officially separated from Ames the following month, leaving his Tilgaun home to her. In the city he embarked on a relationship with Theda Conkey Webber—a woman he had met in the autumn of 1927—and she shortly after legally changed her name to Dawn Allen. In New York, Mundy had resumed his friendship with Natacha Rambova, whom he had first met at Point Loma. Through her he was introduced to the spirit medium George Wehner, who helped develop Mundy's interest in Spiritualism. Mundy then wrote an introduction to Wehner's autobiography, ''A Curious Life'', reflecting his own growing interest in Spiritualism. Both Rambova and Mundy and Dawn moved into the Master Apartments building, which rented its rooms to a large number of artists and writers. Mundy became involved in Nicholas Roerich's museum, which was located in the building, and travelled to London in order to convince the authorities to permit Roerich's expedition to India and in to the Himalayas; they had initially been hesitant that Roerich—who was Russian by birth—may have been an intelligence agent for the  In 1929 he proceeded on a visit to Europe with Dawn, spending time in London, Paris, and Rome before returning to New York.

Mundy and Dawn proceeded to Mexico via Cuba, settling in Yucatan, where they visited Maya archaeological sites like

In 1929 he proceeded on a visit to Europe with Dawn, spending time in London, Paris, and Rome before returning to New York.

Mundy and Dawn proceeded to Mexico via Cuba, settling in Yucatan, where they visited Maya archaeological sites like

Over the course of his career, Mundy produced 47 novels, 130 novelettes and short stories, and 23 articles, as well as one non-fiction book. Mundy biographer

Over the course of his career, Mundy produced 47 novels, 130 novelettes and short stories, and 23 articles, as well as one non-fiction book. Mundy biographer

Dustfall

* * * *

at

Talbot Mundy – Master of Mystical Adventure

Entry at the Encyclopedia of Science fiction

* * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Mundy, Talbot 1879 births 1940 deaths 19th-century English male writers 19th-century British novelists 19th-century British short story writers 19th-century English non-fiction writers 20th-century English male writers 20th-century English novelists 20th-century English short story writers 20th-century English non-fiction writers English fantasy writers English historical novelists English male non-fiction writers English male novelists English male short story writers English non-fiction writers English short story writers People from Hammersmith Writers from the London Borough of Hammersmith and Fulham Pulp fiction writers Writers of historical fiction set in antiquity Great Pyramid of Giza People educated at Rugby School

adventure fiction

Adventure fiction is a type of fiction that usually presents danger, or gives the reader a sense of excitement. Some adventure fiction also satisfies the literary definition of Romance (prose fiction)#Definition, romance fiction.

History

In t ...

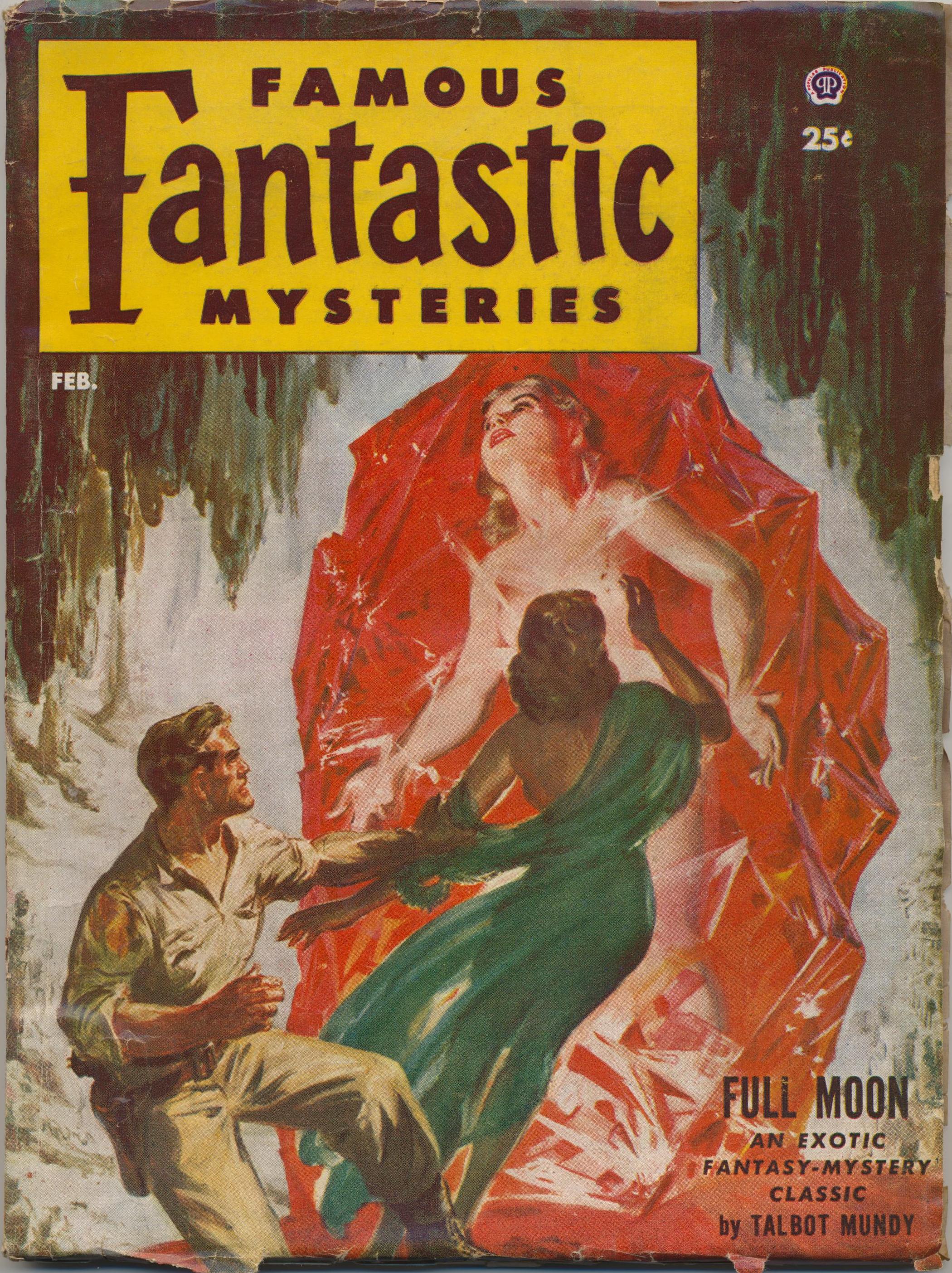

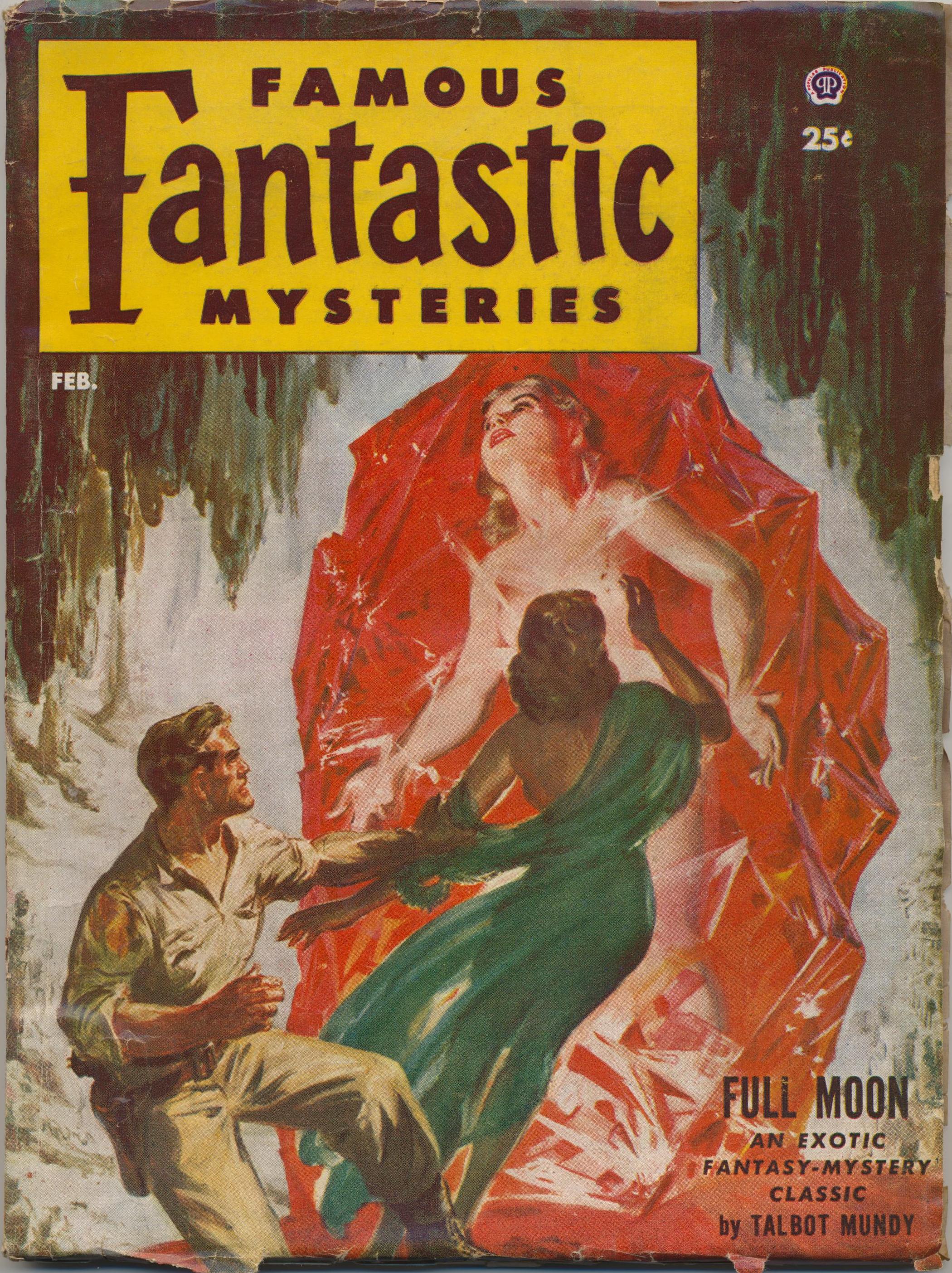

. Based for most of his life in the United States, he also wrote under the pseudonym of Walter Galt. Best known as the author of '' King of the Khyber Rifles'' and the Jimgrim series, much of his work was published in pulp magazine

Pulp magazines (also referred to as "the pulps") were inexpensive fiction magazines that were published from 1896 until around 1955. The term "pulp" derives from the Pulp (paper), wood pulp paper on which the magazines were printed, due to their ...

s.

Mundy was born to a conservative middle-class family in Hammersmith

Hammersmith is a district of West London, England, southwest of Charing Cross. It is the administrative centre of the London Borough of Hammersmith and Fulham, and identified in the London Plan as one of 35 major centres in Greater London.

It ...

, London

London is the Capital city, capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of both England and the United Kingdom, with a population of in . London metropolitan area, Its wider metropolitan area is the largest in Wester ...

. Educated at Rugby School

Rugby School is a Public school (United Kingdom), private boarding school for pupils aged 13–18, located in the town of Rugby, Warwickshire in England.

Founded in 1567 as a free grammar school for local boys, it is one of the oldest independ ...

, he left with no qualifications and moved to British India

The provinces of India, earlier presidencies of British India and still earlier, presidency towns, were the administrative divisions of British governance in South Asia. Collectively, they have been called British India. In one form or another ...

, where he worked in administration and then journalism. He relocated to East Africa, where he worked as an ivory poacher and then as the town clerk of Kisumu

Kisumu ( ) is the third-largest city in Kenya located in the Lake Victoria area in the former Nyanza Province. It is the second-largest city after Kampala in the Lake Victoria Basin. The city has a population of slightly over 600,000. The ...

. In 1909 he moved to New York City

New York, often called New York City (NYC), is the most populous city in the United States, located at the southern tip of New York State on one of the world's largest natural harbors. The city comprises five boroughs, each coextensive w ...

where he lived in poverty. A friend encouraged him to start writing about his life experiences, and he sold his first short story to Frank Munsey

Frank Andrew Munsey (August 21, 1854 – December 22, 1925) was an American newspaper and magazine publisher, banker, political financier and author. He was born in Mercer, Maine, Mercer, Maine, but spent most of his life in New York City. The v ...

's magazine, '' The Scrap Book'', in 1911. He soon began selling short stories and non-fiction articles to a variety of pulp magazines, such as '' Argosy'', ''Cavalier

The term ''Cavalier'' () was first used by Roundheads as a term of abuse for the wealthier royalist supporters of Charles I of England and his son Charles II of England, Charles II during the English Civil War, the Interregnum (England), Int ...

'', and ''Adventure

An adventure is an exciting experience or undertaking that is typically bold, sometimes risky. Adventures may be activities with danger such as traveling, exploring, skydiving, mountain climbing, scuba diving, river rafting, or other extreme spo ...

''. In 1914 Mundy published his first novel, ''Rung Ho!'', soon followed by ''The Winds of the World'' and ''King of the Khyber Rifles'', all of which were set in British India and drew upon his own experiences. Critically acclaimed, they were published in both the U.S. and U.K.

Becoming a U.S. citizen, in 1918 he joined the Christian Science

Christian Science is a set of beliefs and practices which are associated with members of the Church of Christ, Scientist. Adherents are commonly known as Christian Scientists or students of Christian Science, and the church is sometimes in ...

new religious movement

A new religious movement (NRM), also known as a new religion, is a religious or Spirituality, spiritual group that has modern origins and is peripheral to its society's dominant religious culture. NRMs can be novel in origin, or they can be part ...

, and with them moved to Jerusalem

Jerusalem is a city in the Southern Levant, on a plateau in the Judaean Mountains between the Mediterranean Sea, Mediterranean and the Dead Sea. It is one of the List of oldest continuously inhabited cities, oldest cities in the world, and ...

to establish the city's first English-language newspaper. Returning to the U.S. in 1920, he began writing the Jimgrim series and saw the first film adaptations of his stories. Spending time at the Theosophical community of Lomaland in San Diego

San Diego ( , ) is a city on the Pacific coast of Southern California, adjacent to the Mexico–United States border. With a population of over 1.4 million, it is the List of United States cities by population, eighth-most populous city in t ...

, California

California () is a U.S. state, state in the Western United States that lies on the West Coast of the United States, Pacific Coast. It borders Oregon to the north, Nevada and Arizona to the east, and shares Mexico–United States border, an ...

, he became a friend of Katherine Tingley

Katherine Augusta Westcott Tingley (July 6, 1847 – July 11, 1929) was a social worker and prominent Theosophy (Blavatskian), Theosophist. She led the Theosophical Society Pasadena, American Section of the Theosophical Society after W. Q. Judge ...

and embraced Theosophy

Theosophy is a religious movement established in the United States in the late 19th century. Founded primarily by the Russian Helena Blavatsky and based largely on her writings, it draws heavily from both older European philosophies such as Neop ...

. Many of his novels produced in the coming years, most notably ''Om: The Secret of Ahbor Valley'' and ''The Devil's Guard'', reflected his Theosophical beliefs. He also involved himself in various failed business ventures, including an oil drilling operation in Tijuana

Tijuana is the most populous city of the Mexican state of Baja California, located on the northwestern Pacific Coast of Mexico. Tijuana is the municipal seat of the Tijuana Municipality, the hub of the Tijuana metropolitan area and the most popu ...

, Mexico. During the Great Depression

The Great Depression was a severe global economic downturn from 1929 to 1939. The period was characterized by high rates of unemployment and poverty, drastic reductions in industrial production and international trade, and widespread bank and ...

he supplemented his literary income by writing scripts for the radio series '' Jack Armstrong, the All-American Boy''. He suffered from diabetes

Diabetes mellitus, commonly known as diabetes, is a group of common endocrine diseases characterized by sustained high blood sugar levels. Diabetes is due to either the pancreas not producing enough of the hormone insulin, or the cells of th ...

, eventually dying of complications.

During Mundy's career his work was often compared with that of his more commercially successful contemporaries, H. Rider Haggard and Rudyard Kipling

Joseph Rudyard Kipling ( ; 30 December 1865 – 18 January 1936)''The Times'', (London) 18 January 1936, p. 12. was an English journalist, novelist, poet, and short-story writer. He was born in British Raj, British India, which inspired much ...

. Like them he expressed a positive interest in Asian religion and philosophy, although unlike them he adopted an anti-colonialist stance. His work has been cited as an influence on a variety of later science-fiction and fantasy writers, and he has been the subject of two biographies.

Early life

Childhood: 1879–99

Mundy was born as William Lancaster Gribbon on 23 April 1879 at his parental home of 59 Milson Road,Hammersmith

Hammersmith is a district of West London, England, southwest of Charing Cross. It is the administrative centre of the London Borough of Hammersmith and Fulham, and identified in the London Plan as one of 35 major centres in Greater London.

It ...

in West London. The following month he was baptised into the Anglican

Anglicanism, also known as Episcopalianism in some countries, is a Western Christianity, Western Christian tradition which developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the ...

Church at the local St. Matthews Church. His father, Walter Galt Gribbon (1845–95), had been born in Leeds

Leeds is a city in West Yorkshire, England. It is the largest settlement in Yorkshire and the administrative centre of the City of Leeds Metropolitan Borough, which is the second most populous district in the United Kingdom. It is built aro ...

, Yorkshire

Yorkshire ( ) is an area of Northern England which was History of Yorkshire, historically a county. Despite no longer being used for administration, Yorkshire retains a strong regional identity. The county was named after its county town, the ...

as the son of a porcelain and glass merchant. Gribbon had studied at Oxford University

The University of Oxford is a collegiate research university in Oxford, England. There is evidence of teaching as early as 1096, making it the oldest university in the English-speaking world and the second-oldest continuously operating u ...

's St. John's College and then trained as a barrister

A barrister is a type of lawyer in common law jurisdiction (area), jurisdictions. Barristers mostly specialise in courtroom advocacy and litigation. Their tasks include arguing cases in courts and tribunals, drafting legal pleadings, jurisprud ...

before relocating to Swansea

Swansea ( ; ) is a coastal City status in the United Kingdom, city and the List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, second-largest city of Wales. It forms a Principal areas of Wales, principal area, officially known as the City and County of ...

, where he first worked as a school teacher and then an accountant. After his first wife's death, he married Mundy's mother, Margaret Lancaster, in Nantyglo

Nantyglo () is a village in the ancient parish of Aberystruth and county of Monmouth situated deep within the South Wales Valleys between Blaina and Brynmawr in the county borough of Blaenau Gwent.

Governance

An Wards and electoral divisions of ...

in July 1878. A member of an English family based in Wales, she was the sister of the politician John Lancaster. After a honeymoon

A honeymoon is a vacation taken by newlyweds after their wedding to celebrate their marriage. Today, honeymoons are often celebrated in destinations considered exotic or romantic. In a similar context, it may also refer to the phase in a couple ...

in Ilfracombe

Ilfracombe ( ) is a seaside resort and civil parishes in England, civil parish on the North Devon coast, England, with a small harbour surrounded by cliffs.

The parish stretches along the coast from the 'Coastguard Cottages' in Hele Bay towar ...

, Devon

Devon ( ; historically also known as Devonshire , ) is a ceremonial county in South West England. It is bordered by the Bristol Channel to the north, Somerset and Dorset to the east, the English Channel to the south, and Cornwall to the west ...

, the newly married couple moved to Hammersmith, where Mundy was their first child. They would have three further children: Walter Harold (b. 1881), Agnes Margaret (b. 1882), and Florence Mary (c.1883), although the latter died in infancy. In 1883 the family moved to nearby Norbiton, although within a few years had moved out of London to Kingston Hill, Surrey

Surrey () is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South East England. It is bordered by Greater London to the northeast, Kent to the east, East Sussex, East and West Sussex to the south, and Hampshire and Berkshire to the wes ...

.

Mundy was raised into a conservative middle-class Victorian milieu. His father owned a successful accountancy business and was director of the Woking Water and Gas Company, as well as being an active member of the Conservative Party and Primrose League. He was also a devout Anglican, serving as warden

A warden is a custodian, defender, or guardian. Warden is often used in the sense of a watchman or guardian, as in a prison warden. It can also refer to a chief or head official, as in the Warden of the Mint.

''Warden'' is etymologically ident ...

at St. Luke's Church. The family went on summer holidays to southern coastal towns such as Hythe, Sandgate, and Charmouth

Charmouth is a village and civil parish in west Dorset, England. The village is situated on the mouth of the River Char, around north-east of Lyme Regis. Dorset County Council estimated that in 2013 the population of the civil parish was 1,31 ...

, with Mundy also spending time visiting relatives in Bardney, Lincolnshire

Lincolnshire (), abbreviated ''Lincs'', is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in the East Midlands and Yorkshire and the Humber regions of England. It is bordered by the East Riding of Yorkshire across the Humber estuary to th ...

. He attended Grove House, a preparatory school in Guildford

Guildford () is a town in west Surrey, England, around south-west of central London. As of the 2011 census, the town has a population of about 77,000 and is the seat of the wider Borough of Guildford, which had around inhabitants in . The nam ...

, Surrey

Surrey () is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South East England. It is bordered by Greater London to the northeast, Kent to the east, East Sussex, East and West Sussex to the south, and Hampshire and Berkshire to the wes ...

, before receiving a scholarship to attend Rugby School

Rugby School is a Public school (United Kingdom), private boarding school for pupils aged 13–18, located in the town of Rugby, Warwickshire in England.

Founded in 1567 as a free grammar school for local boys, it is one of the oldest independ ...

, where he arrived in September 1893.

In 1895 his father died of a brain hemorrhage

The brain is an organ (biology), organ that serves as the center of the nervous system in all vertebrate and most invertebrate animals. It consists of nervous tissue and is typically located in the head (cephalization), usually near organs for ...

, and Mundy henceforth became increasingly rebellious. He left Rugby School without any qualifications in December 1895; in later years he recalled bad memories of the institution, comparing it to "prisons run by sadists". With Mundy unable to go to university, his mother hoped that he might enter the Anglican clergy. He worked briefly for a newspaper in London, although the firm closed shortly after. He left England and moved to Quedlinburg

Quedlinburg () is a town situated just north of the Harz mountains, in the Harz (district), district of Harz in the west of Saxony-Anhalt, Germany. As an influential and prosperous trading centre during the early Middle Ages, Quedlinburg becam ...

in northern Germany with his pet fox terrier. He didn't speak German but secured work as an assistant driver towing vans for a circus; after a colleague drunkenly killed his dog he left the job. Back in England, he worked in farming and estate management for his uncle in Lincolnshire, describing this lifestyle as "'High Farming,' high church

A ''high church'' is a Christian Church whose beliefs and practices of Christian ecclesiology, Christian liturgy, liturgy, and Christian theology, theology emphasize "ritual, priestly authority, ndsacraments," and a standard liturgy. Although ...

and old port and all that went with that life – pheasant shooting, fox-hunting and so on."

India and East Africa: 1899–1909

Talbot's accounts of the following years are unreliable, tainted by his own fictionalised claims about his activities. In March 1899 he sailed aboard the ''Caledonia'' toBombay

Mumbai ( ; ), also known as Bombay ( ; its official name until 1995), is the capital city of the Indian States and union territories of India, state of Maharashtra. Mumbai is the financial centre, financial capital and the list of cities i ...

in British India

The provinces of India, earlier presidencies of British India and still earlier, presidency towns, were the administrative divisions of British governance in South Asia. Collectively, they have been called British India. In one form or another ...

, where he had secured an administrative job in a famine relief program based in the native state

In biochemistry, the native state of a protein or nucleic acid is its properly Protein folding, folded and/or assembled form, which is operative and functional. The native state of a biomolecule may possess all four levels of biomolecular structu ...

of Baroda. There he purchased a horse and became a fan of pig-sticking, a form of boar hunting.

After suffering a bout of malaria

Malaria is a Mosquito-borne disease, mosquito-borne infectious disease that affects vertebrates and ''Anopheles'' mosquitoes. Human malaria causes Signs and symptoms, symptoms that typically include fever, Fatigue (medical), fatigue, vomitin ...

he returned to Britain in April 1900. In later years he claimed that during this period he had fought for the British Army in the Second Boer War

The Second Boer War (, , 11 October 189931 May 1902), also known as the Boer War, Transvaal War, Anglo–Boer War, or South African War, was a conflict fought between the British Empire and the two Boer republics (the South African Republic and ...

, although this was untrue, for chronologically it conflicted with his documented activities in Britain; he did however have relatives who fought in the conflict. Another of his later claims was that while visiting Brighton

Brighton ( ) is a seaside resort in the city status in the United Kingdom, city of Brighton and Hove, East Sussex, England, south of London.

Archaeological evidence of settlement in the area dates back to the Bronze Age Britain, Bronze Age, R ...

in summer 1900 he ran into his favourite writer, Rudyard Kipling

Joseph Rudyard Kipling ( ; 30 December 1865 – 18 January 1936)''The Times'', (London) 18 January 1936, p. 12. was an English journalist, novelist, poet, and short-story writer. He was born in British Raj, British India, which inspired much ...

, while walking in the street, and that they had a conversation about India.

Securing a job as a reporter for the ''Daily Mail

The ''Daily Mail'' is a British daily Middle-market newspaper, middle-market Tabloid journalism, tabloid conservative newspaper founded in 1896 and published in London. , it has the List of newspapers in the United Kingdom by circulation, h ...

'', in March 1901 he returned to India aboard the ''Caledonia''. His assignment was to report on the Mahsud uprising against the British administration led by Mulla Pawindah. On this assignment, he accompanied British troops although only reached as far as Peshawar

Peshawar is the capital and List of cities in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa by population, largest city of the Administrative units of Pakistan, Pakistani province of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. It is the sixth most populous city of Pakistan, with a district p ...

, not entering the Khyber Pass

The Khyber Pass (Urdu: درۂ خیبر; ) is a mountain pass in the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province of Pakistan, on the border with the Nangarhar Province of Afghanistan. It connects the town of Landi Kotal to the Valley of Peshawar at Jamrud by tr ...

which he would use as a setting for later stories. While in Rajputana

Rājputana (), meaning Land of the Rajputs, was a region in the Indian subcontinent that included mainly the entire present-day States of India, Indian state of Rajasthan, parts of the neighboring states of Madhya Pradesh and Gujarat, and adjo ...

he had his first experience with an Indian guru, and after his assignment he went tiger hunting. In Bombay in 1901 he met Englishwoman Kathleen Steele, and they had returned to Britain by late 1902, where he gained work for the Walton and Company merchant firm in Holborn

Holborn ( or ), an area in central London, covers the south-eastern part of the London Borough of Camden and a part (St Andrew Holborn (parish), St Andrew Holborn Below the Bars) of the Wards of the City of London, Ward of Farringdon Without i ...

. The couple married in Westminster

Westminster is the main settlement of the City of Westminster in Central London, Central London, England. It extends from the River Thames to Oxford Street and has many famous landmarks, including the Palace of Westminster, Buckingham Palace, ...

in January 1903. By this point he had amassed large debts, and with his wife fled to Cape Town

Cape Town is the legislature, legislative capital city, capital of South Africa. It is the country's oldest city and the seat of the Parliament of South Africa. Cape Town is the country's List of municipalities in South Africa, second-largest ...

, South Africa to evade his creditors; in his absence he was declared bankrupt

Bankruptcy is a legal process through which people or other entities who cannot repay debts to creditors may seek relief from some or all of their debts. In most jurisdictions, bankruptcy is imposed by a court order, often initiated by the de ...

. He wife returned to London, and they never saw each other again. From there, he claimed to have boarded a merchant sailing vessel to Australia, where he spent time in Sydney

Sydney is the capital city of the States and territories of Australia, state of New South Wales and the List of cities in Australia by population, most populous city in Australia. Located on Australia's east coast, the metropolis surrounds Syd ...

and Brisbane

Brisbane ( ; ) is the List of Australian capital cities, capital and largest city of the States and territories of Australia, state of Queensland and the list of cities in Australia by population, third-most populous city in Australia, with a ...

before sailing back to Africa and disembarking in Laurenço Marques, Portuguese East Africa.

In February 1904 he arrived in

In February 1904 he arrived in Mombasa

Mombasa ( ; ) is a coastal city in southeastern Kenya along the Indian Ocean. It was the first capital of British East Africa, before Nairobi was elevated to capital status in 1907. It now serves as the capital of Mombasa County. The town is ...

, British East Africa

East Africa Protectorate (also known as British East Africa) was a British protectorate in the African Great Lakes, occupying roughly the same area as present-day Kenya, from the Indian Ocean inland to the border with Uganda in the west. Cont ...

, later claiming that he initially worked as a hunter. He also claimed that while near Shirati, he was shot in the leg with a poison spear by a Masai who was stealing his cattle. He travelled to Muanza in German East Africa, where he was afflicted with blackwater fever. Mundy then worked as an elephant hunter, collecting and selling ivory

Ivory is a hard, white material from the tusks (traditionally from elephants) and Tooth, teeth of animals, that consists mainly of dentine, one of the physical structures of teeth and tusks. The chemical structure of the teeth and tusks of mamm ...

. His later novel, ''The Ivory Trail'', was inspired largely by his own experiences at this time. In later years he alleged that he met Frederick Selous at this juncture, although Mundy's biographer has pointed out that Selous was not in East Africa at this time.

Mundy secured employment as the town clerk of Kisumu

Kisumu ( ) is the third-largest city in Kenya located in the Lake Victoria area in the former Nyanza Province. It is the second-largest city after Kampala in the Lake Victoria Basin. The city has a population of slightly over 600,000. The ...

, a frontier town where he was stationed during a number of indigenous tribal insurgencies against British imperial rule; the Kisii rebelled in the winter of 1904–05, followed by the Sotik and the Nandi in summer 1905. On each occasion the rebels were defeated by the British Army. Christian missionaries pressured Mundy into overseeing a program of providing clothes for the native population, who often went naked; he thought this unnecessary, although designed a goat-skin apron for them to wear. He made the acquaintance of a magico-religious specialist, Oketch, of the Kakamega Kavirondo tribe, who healed him after a hunting accident. He had sexual relationships with a variety of indigenous women, and was dismissed from his job as a result. He informed his wife of these activities, thus suggesting that she sue him for divorce; the divorce was granted in May 1908.

Unemployed, he moved to Nairobi

Nairobi is the Capital city, capital and largest city of Kenya. The city lies in the south-central part of Kenya, at an elevation of . The name is derived from the Maasai language, Maasai phrase , which translates to 'place of cool waters', a ...

, where he met a married woman, Inez Craven (née Broom). Together they eloped, and she divorced her husband in November 1908. The couple moved to an island on Lake Victoria

Lake Victoria is one of the African Great Lakes. With a surface area of approximately , Lake Victoria is Africa's largest lake by area, the world's largest tropics, tropical lake, and the world's second-largest fresh water lake by surface are ...

, where they lived from February to June, although were subsequently arrested under the Distressed British Subjects Act; under this, they faced imprisoned for six months in Mombasa before deportation to Bombay, although this eventuality did not occur. In November, the couple married at Mombasa Registry Office; here, he first used the name of "Talbot Mundy", erroneously claiming to the son of Charles Chetwynd-Talbot, 20th Earl of Shrewsbury. That month, they left Mombasa aboard the ''SS Natal'', stopping in Djibouti

Djibouti, officially the Republic of Djibouti, is a country in the Horn of Africa, bordered by Somalia to the south, Ethiopia to the southwest, Eritrea in the north, and the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden to the east. The country has an area ...

and Port Said

Port Said ( , , ) is a port city that lies in the northeast Egypt extending about along the coast of the Mediterranean Sea, straddling the west bank of the northern mouth of the Suez Canal. The city is the capital city, capital of the Port S ...

on their way to Marseille

Marseille (; ; see #Name, below) is a city in southern France, the Prefectures in France, prefecture of the Departments of France, department of Bouches-du-Rhône and of the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur Regions of France, region. Situated in the ...

, from where they made their way to England. There they visited Mundy's mother in Lee-on-Solent, Hampshire

Hampshire (, ; abbreviated to Hants.) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South East England. It is bordered by Berkshire to the north, Surrey and West Sussex to the east, the Isle of Wight across the Solent to the south, ...

, and she agreed to give Mundy a substantial sum of money; it would be the last time Mundy saw her. Mundy and his wife spent most of the money while staying in London, before leaving from Southampton

Southampton is a port City status in the United Kingdom, city and unitary authority in Hampshire, England. It is located approximately southwest of London, west of Portsmouth, and southeast of Salisbury. Southampton had a population of 253, ...

aboard the ''SS Teutonic'' in September 1909, headed for the United States.

United States and early literary career: 1909–15

Arriving inNew York City

New York, often called New York City (NYC), is the most populous city in the United States, located at the southern tip of New York State on one of the world's largest natural harbors. The city comprises five boroughs, each coextensive w ...

, the couple moved into a hotel room in the Gashouse District. Soon after arrival, Mundy was mugged and suffered a fractured skull, being hospitalised in Bellevue Hospital. Doctors feared that he might not survive the injury, while the perpetrator, Joseph Cavill, was indicted with first degree robbery and sentenced to six months imprisonment. Throughout 1910, Mundy worked in a series of menial jobs, being fired from several of them. His hospitalisation and poverty put great strain on his marriage, as did legal charges filed by the United States Department of Commerce and Labor

The United States Department of Commerce and Labor was a short-lived Cabinet department of the United States government, which was concerned with fostering and supervising big business. It existed from 1903 to 1913. The United States Departmen ...

accusing the couple of entering the country using false information; the charges were soon dismissed.

In 1910, he ran into Jeff Hanley, a reporter who had covered his mugging incident; Hanley was impressed by Mundy's tales of India and Africa, and lent him a typewriter

A typewriter is a Machine, mechanical or electromechanical machine for typing characters. Typically, a typewriter has an array of Button (control), keys, and each one causes a different single character to be produced on paper by striking an i ...

, suggesting that he write some of his stories down for potential publication. Mundy did so, and published his first short story

A short story is a piece of prose fiction. It can typically be read in a single sitting and focuses on a self-contained incident or series of linked incidents, with the intent of evoking a single effect or mood. The short story is one of the old ...

, "A Transaction in Diamonds", in the February 1911 issue of Frank Munsey

Frank Andrew Munsey (August 21, 1854 – December 22, 1925) was an American newspaper and magazine publisher, banker, political financier and author. He was born in Mercer, Maine, Mercer, Maine, but spent most of his life in New York City. The v ...

's magazine, '' The Scrap Book''. His second publication was a non-fiction article, "Pig-sticking in India", which appeared in the April issue of a new pulp magazine

Pulp magazines (also referred to as "the pulps") were inexpensive fiction magazines that were published from 1896 until around 1955. The term "pulp" derives from the Pulp (paper), wood pulp paper on which the magazines were printed, due to their ...

, ''Adventure

An adventure is an exciting experience or undertaking that is typically bold, sometimes risky. Adventures may be activities with danger such as traveling, exploring, skydiving, mountain climbing, scuba diving, river rafting, or other extreme spo ...

'', which specialised in adventure fiction. Although he and ''Adventures editor Arthur Sullivant Hoffman did not initially like each other, In the May 1911 issue of Adventure his short story 'The Phantom Battery' appeared. Mundy continued writing for the magazine, as well as for ''The Scrap Book'', '' Argosy'', and ''Cavalier

The term ''Cavalier'' () was first used by Roundheads as a term of abuse for the wealthier royalist supporters of Charles I of England and his son Charles II of England, Charles II during the English Civil War, the Interregnum (England), Int ...

''. In 1912, Mundy published sixteen short stories and four articles in ''Adventure'', seven of which were under the name "Walter Galt". Biographer Brian Taves suggested that these early short stories are notable "not so much for themselves as for how much they diverged from his later oeuvre", for instance dealing with subjects like boxing

Boxing is a combat sport and martial art. Taking place in a boxing ring, it involves two people – usually wearing protective equipment, such as boxing glove, protective gloves, hand wraps, and mouthguards – throwing Punch (combat), punch ...

that are absent from his later work. In 1912, ''Adventure'' had also established The Adventurer's Club, of which Mundy became a chartered member.

Mundy's story "The Soul of a Regiment" attracted particular praise and critical attention. Revolving around an Egyptian regiment who are taught to play music by their English Sergeant-Instructor in the buildup to the Somaliland Campaign

The Somaliland campaign, also called the Anglo-Somali War or the Dervish rebellion, was a series of military expeditions that took place between 1900 and 1920 in modern-day Somaliland. The British were assisted in their offensives by the Ethiop ...

, it was initially published by ''Adventure'' in February 1912, before becoming the first of Mundy's publications to be republished in Britain, appearing in the March 1912 issue of George Newnes' '' The Grand Magazine''. Soon he would see his short stories published in a range of British publications, including ''The Strand Magazine

''The Strand Magazine'' was a monthly British magazine founded by George Newnes, composed of short fiction and general interest articles. It was published in the United Kingdom from January 1891 to March 1950, running to 711 issues, though the ...

'', '' London Magazine'', and '' Cassell's Magazine of Fiction'' as well as ''The Grand''. 1912 also saw two cinematic adaptations of his short stories, '' For Valour'' and ''The Fire Cop'' – produced by the Edison Company and Selig Polyscope Company

The Selig Polyscope Company was an American motion picture company that was founded in 1896 by William Selig in Chicago, Illinois. The company produced hundreds of early, widely distributed commercial moving pictures, including the first films ...

respectively – with both being fairly faithful to his original stories.

In June 1912, Inez sued for divorce on the grounds of Mundy's adultery; he did not challenge the accusation and the divorce was confirmed in October. As part of the divorce settlement, Mundy was forced to pay $20 a week alimony to Inez for the rest of her life. Mundy moved into an apartment in Greenwich Village

Greenwich Village, or simply the Village, is a neighborhood on the west side of Lower Manhattan in New York City, bounded by 14th Street (Manhattan), 14th Street to the north, Broadway (Manhattan), Broadway to the east, Houston Street to the s ...

, which for a short time he shared with Hoffman's assistant Sinclair Lewis

Harry Sinclair Lewis (February 7, 1885 – January 10, 1951) was an American novelist, short-story writer, and playwright. In 1930 Nobel Prize in Literature, 1930, he became the first author from the United States (and the first from the America ...

. At this point he met the Kentucky-born portrait painter Harriette Rosemary Strafer, and after she agreed to marry him they wed in Stamford, Connecticut

Connecticut ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It borders Rhode Island to the east, Massachusetts to the north, New York (state), New York to the west, and Long Island Sound to the south. ...

in August 1913. Strafer had been a practitioner of a Christian new religious movement, Christian Science

Christian Science is a set of beliefs and practices which are associated with members of the Church of Christ, Scientist. Adherents are commonly known as Christian Scientists or students of Christian Science, and the church is sometimes in ...

, since 1904, and encouraged her new husband to take an interest in the faith; studying the writings of its founder, Mary Baker Eddy

Mary Baker Eddy (née Baker; July 16, 1821 – December 3, 1910) was an American religious leader and author, who in 1879 founded The Church of Christ, Scientist, the ''Mother Church'' of the Christian Science movement. She also founded ''The C ...

, he converted to it in 1914. The couple then moved to the town of Norway

Norway, officially the Kingdom of Norway, is a Nordic countries, Nordic country located on the Scandinavian Peninsula in Northern Europe. The remote Arctic island of Jan Mayen and the archipelago of Svalbard also form part of the Kingdom of ...

in Maine

Maine ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the United States, and the northeasternmost state in the Contiguous United States. It borders New Hampshire to the west, the Gulf of Maine to the southeast, and the Provinces and ...

, where Mundy's friend Hugh Pendexter was already resident. He involved himself in the activities of his new home, becoming chairman of the local agricultural committee and joining the Norway Committee on Public Safety. Following the outbreak of World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, in which Britain went to war against Germany, Mundy sought to attain U.S. citizenship; applying in November 1914, his request was approved in March 1917.

In Norway, Mundy authored his first novel, ''For the Peace of India'', which was set during the Indian Rebellion of 1857

The Indian Rebellion of 1857 was a major uprising in India in 1857–58 against Company rule in India, the rule of the East India Company, British East India Company, which functioned as a sovereign power on behalf of the The Crown, British ...

. It was serialised in ''Adventure'' under the altered title of ''Rung Ho!'' before being published by Charles Scribner in the U.S., and Cassells in the U.K. Critically well received, the book sold well. In August 1914, ''Adventure'' published "The Sword of Iskander", the first of Mundy's eight novelettes revolving around the character of Dick Anthony of Arran, a Scotsman battling the Russians in Iran, which ran until March 1915. It was in his January 1914 short story "A Soldier and a Gentleman" that he introduced the character of Yasmini, a young Hindu

Hindus (; ; also known as Sanātanīs) are people who religiously adhere to Hinduism, also known by its endonym Sanātana Dharma. Jeffery D. Long (2007), A Vision for Hinduism, IB Tauris, , pp. 35–37 Historically, the term has also be ...

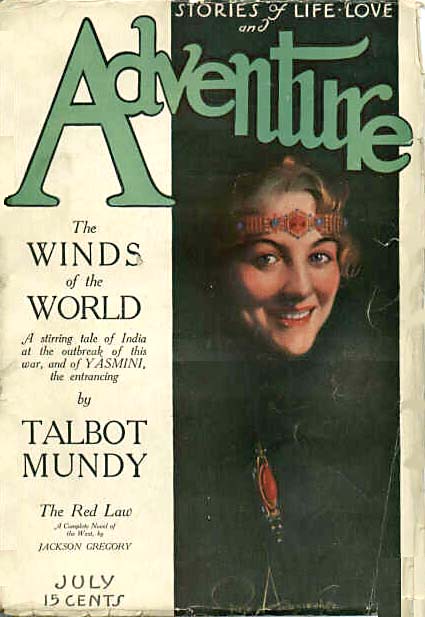

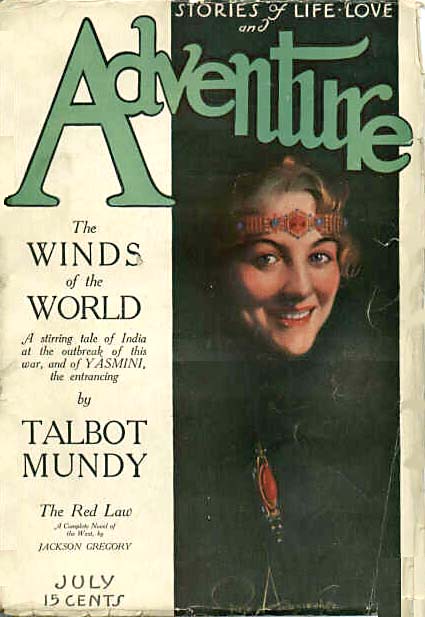

woman who would reappear in many of his later stories. He then began work on a second novel, ''The Winds of the World'', which told the story of a Sikh

Sikhs (singular Sikh: or ; , ) are an ethnoreligious group who adhere to Sikhism, a religion that originated in the late 15th century in the Punjab region of the Indian subcontinent, based on the revelation of Guru Nanak. The term ''Si ...

officer, Risaldar-Major Ranjoor Singh, who sets out to expose a German spy who is attempting to foment an uprising in British India; during the course of the story he introduced Yasmini as a character. Serialised in ''Adventure'' from July to September 1915, it was then published in Britain by Cassell; when Scribner declined to publish it, Mundy acquired a literary agent, Paul Reynolds. Upon publication, it received good reviews.

''King of the Khyber Rifles'': 1916–18

Mundy authored comparatively few short stories in 1916 as he focused on his third novel, '' King of the Khyber Rifles'', which told the story of Captain Athelstan King of the British India Secret Service and his attempt to prevent a German-backedjihad

''Jihad'' (; ) is an Arabic word that means "exerting", "striving", or "struggling", particularly with a praiseworthy aim. In an Islamic context, it encompasses almost any effort to make personal and social life conform with God in Islam, God ...

break out against the British administration in the North-West Frontier. Again, it featured Yasmini as a core character. The novel was serialised in '' Everybody's'' from May 1916 to January 1917, accompanied by illustrations by Joseph Clement Coll, a man whom Mundy praised, declaring that "there never was a better illustrator in the history of the world!". The novel was then published by U.S.-based Bobbs-Merrill in November 1916 and by U.K.-based Constable

A constable is a person holding a particular office, most commonly in law enforcement. The office of constable can vary significantly in different jurisdictions. ''Constable'' is commonly the rank of an officer within a police service. Other peo ...

in January 1917; it received critical acclaim, with critics comparing it to the work of Kipling and H. Rider Haggard.

In 1917 only two of Mundy's short stories appeared in ''Adventure''; the first was a reprint of "The Soul of a Regiment", while the second was a sequel, "The Damned Old Nigger"; in a 1918 readership survey, these were rated as the first and third most popular stories in ''Adventure'', respectively. From October to December 1917 he serialised his fourth novel, ''Hira Singh's Tale'', in ''Adventure'', which was partly based upon real events. The story revolves around a regiment of Sikhs fighting on the Western Front for the British Empire who are then captured by the Germans; transferred to a Turkish prisoner of war camp, they attempt to escape and return overland to India. Casells published a British edition in June 1918, although for American publication in book form it was renamed ''Hira Singh''. Talbot devoted the latter to his friend Elmer Davis, and gifted a copy to the British monarch George V

George V (George Frederick Ernest Albert; 3 June 1865 – 20 January 1936) was King of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and Emperor of India, from 6 May 1910 until Death and state funeral of George V, his death in 1936.

George w ...

, who was Commander-in-Chief of the 14th Ferozepore Sikhs. The book received largely positive reviews in the U.S., although was criticised in the '' Times Literary Supplement''. Mundy felt that many reviewers had failed to understand the main reason for the book; he had meant it to represent a tribute to the Indian soldiers who had died fighting in Europe during World War I.

In autumn 1918, Mundy and his wife moved to Fifth Avenue

Fifth Avenue is a major thoroughfare in the borough (New York City), borough of Manhattan in New York City. The avenue runs south from 143rd Street (Manhattan), West 143rd Street in Harlem to Washington Square Park in Greenwich Village. The se ...

in New York City. That year he serialised ''On the Trail of Tippoo Tib'', part of a series of novelettes which he termed "The Up and Down the Earth Tales". Set in British East Africa prior to the First World War, it dealt with an expedition of three Englishmen and an American who search for a hidden cache of ivory. When published in book form in June, Bobbs-Merrill renamed the story ''The Ivory Trail''. ''The Ivory Trail'' was Mundy's most widely reviewed work, receiving a largely positive reception, and resulting in him being interviewed for the '' New York Evening World''.

Later life

Christian Science and Palestine: 1918–20

In December 1918, Mundy and his wife had visited

In December 1918, Mundy and his wife had visited Indianapolis

Indianapolis ( ), colloquially known as Indy, is the List of capitals in the United States, capital and List of municipalities in Indiana, most populous city of the U.S. state of Indiana and the county seat of Marion County, Indiana, Marion ...

, there meeting with the team at Bobbs-Merrill, and it was here that he encountered Christian Science

Christian Science is a set of beliefs and practices which are associated with members of the Church of Christ, Scientist. Adherents are commonly known as Christian Scientists or students of Christian Science, and the church is sometimes in ...

, a new religious movement

A new religious movement (NRM), also known as a new religion, is a religious or Spirituality, spiritual group that has modern origins and is peripheral to its society's dominant religious culture. NRMs can be novel in origin, or they can be part ...

founded by Mary Baker Eddy

Mary Baker Eddy (née Baker; July 16, 1821 – December 3, 1910) was an American religious leader and author, who in 1879 founded The Church of Christ, Scientist, the ''Mother Church'' of the Christian Science movement. She also founded ''The C ...

in the 19th century. He was convinced to advertise his books in the group's newspaper, the ''Christian Science Monitor

''The Christian Science Monitor'' (''CSM''), commonly known as ''The Monitor'', is a nonprofit news organization that publishes daily articles both in electronic format and a weekly print edition. It was founded in 1908 as a daily newspaper b ...

''.

Becoming increasingly interested in the movement, he became close friends with William Denison McCrackan, who was the associated editor of both the '' Christian Science Journal'' and '' Christian Science Sentinel''. Mundy agreed to become the president of The Anglo-American Society, a Christian Science group devoted to providing aid for Palestine

Palestine, officially the State of Palestine, is a country in West Asia. Recognized by International recognition of Palestine, 147 of the UN's 193 member states, it encompasses the Israeli-occupied West Bank, including East Jerusalem, and th ...

, which had recently been conquered by the British from the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

. He also became vice president of the Society's magazine, ''New Earth News''.

Spending time at the Christian Science White Mountains Camp in Tamworth, New Hampshire, it was there that he wrote ''The Eye of Zeitun''; it included the four protagonists who had appeared in ''The Ivory Trail'' experiencing a new adventure in Armenia, and reflected Turkish persecution of the Armenian people. It was serialised in ''Romance'' from February to March 1920 before being published by Bobbs-Merrill in March under the altered title of ''The Eyes of Zeitoon''. The book received mixed reviews and did not sell well. Although pleased with the work of his agent Paul Reynolds, he switched to Howard Wheeler, with whom he felt more comfortable.

In December 1919, Talbot decided to travel to Palestine, to aid the Society in establishing the '' Jerusalem News'', the first-English language newspaper in the city. Departing the U.S. in January 1920 aboard the '' RMS Adriatic'', he arrived in Southampton, before travelling to London, Rome

Rome (Italian language, Italian and , ) is the capital city and most populated (municipality) of Italy. It is also the administrative centre of the Lazio Regions of Italy, region and of the Metropolitan City of Rome. A special named with 2, ...

, Alexandria

Alexandria ( ; ) is the List of cities and towns in Egypt#Largest cities, second largest city in Egypt and the List of coastal settlements of the Mediterranean Sea, largest city on the Mediterranean coast. It lies at the western edge of the Nile ...

, and then reaching Jerusalem

Jerusalem is a city in the Southern Levant, on a plateau in the Judaean Mountains between the Mediterranean Sea, Mediterranean and the Dead Sea. It is one of the List of oldest continuously inhabited cities, oldest cities in the world, and ...

in February. There he became the newspaper's editorial assistant, being involved in writing articles, reporting on current events, proof reading, and editing. In Jerusalem, he entered a relationship with Sally Ames, a fellow Christian Scientist whom he had first met in the U.S. It was also in the city that he later claimed he had met the English writer G. K. Chesterton on the latter's visit. Talbot witnessed the conflict between Arab and Jewish populations within the city, and was present during the Nebi Musa riots. With Ames he also visited Egypt, there traveling to the Great Pyramid of Giza

The Great Pyramid of Giza is the largest Egyptian pyramid. It served as the tomb of pharaoh Khufu, who ruled during the Fourth Dynasty of Egypt, Fourth Dynasty of the Old Kingdom of Egypt, Old Kingdom. Built , over a period of about 26 years ...

and later alleging that he spent a night alone in its King's Chamber. Having identified itself as a wartime paper, the ''Jerusalem News'' ceased publication after the transition from British military rule to the British civilian rule of Mandatory Palestine

Mandatory Palestine was a British Empire, British geopolitical entity that existed between 1920 and 1948 in the Palestine (region), region of Palestine, and after 1922, under the terms of the League of Nations's Mandate for Palestine.

After ...

.

Creating Jimgrim: 1920–22

Mundy returned to New York City in August, there informing Rosemary that he wanted a divorce, which she refused. Unable to live with her, he moved into an apartment in Huguenot Park,Staten Island

Staten Island ( ) is the southernmost of the boroughs of New York City, five boroughs of New York City, coextensive with Richmond County and situated at the southernmost point of New York (state), New York. The borough is separated from the ad ...

. There he authored ''Guns of the Gods'', a story set in Yasmini's youth; it was serialised in ''Adventure'' from March to May, and published in book form by Bobbs-Merrill in June. The ''Times Literary Supplement'' accused it of having a strong anti-English bias.

It was also on Staten Island that he began drawing upon his experiences of Palestine for a series of novelettes set in the region that featured a new protagonist, James Schuyler Grim, or "Jimgrim". As created by Mundy, Jimgrim was an American who had been recruited by the British intelligence services because of his in-depth knowledge of Arab life. Mundy claimed that Jimgrim was based on a real individual, whose identity he refused to reveal, while later biographer Brian Taves has suggested that the character was heavily influenced by T. E. Lawrence. The first of these Jimgrim stories, "The Adventure of El-Kerak", appeared in ''Adventure'' in November 1921; the second, "Under the

It was also on Staten Island that he began drawing upon his experiences of Palestine for a series of novelettes set in the region that featured a new protagonist, James Schuyler Grim, or "Jimgrim". As created by Mundy, Jimgrim was an American who had been recruited by the British intelligence services because of his in-depth knowledge of Arab life. Mundy claimed that Jimgrim was based on a real individual, whose identity he refused to reveal, while later biographer Brian Taves has suggested that the character was heavily influenced by T. E. Lawrence. The first of these Jimgrim stories, "The Adventure of El-Kerak", appeared in ''Adventure'' in November 1921; the second, "Under the Dome of the Rock

The Dome of the Rock () is an Islamic shrine at the center of the Al-Aqsa mosque compound on the Temple Mount in the Old City (Jerusalem), Old City of Jerusalem. It is the world's oldest surviving work of Islamic architecture, the List_of_the_ol ...

", appeared in December, while the third, "The 'Iblis' at Ludd", appeared in January 1922. In August 1922, Mundy published "A Secret Society", in which he took Jimgrim out of Palestine and sent him to Egypt. This series of novelettes promoted the cause of Arab independence from British imperialism and presented an idealised image of the prominent Arab leader Faisal I of Iraq

Faisal I bin Hussein bin Ali Al-Hashemi (, ''Fayṣal al-Awwal bin Ḥusayn bin ʻAlī al-Hāshimī''; 20 May 1885 – 8 September 1933) was King of Iraq from 23 August 1921 until his death in 1933. A member of the Hashemites, Hashemite family, ...

. These early Jimgrim stories were an immediate success for ''Adventure'', however Bobbs-Merrill were nevertheless not keen on them and urged Mundy to write something else. The company had repeatedly lent money to Mundy, who was now heavily in debt to them.

In October 1921, Mundy left New York and settled in Reno, Nevada

Nevada ( ; ) is a landlocked state in the Western United States. It borders Oregon to the northwest, Idaho to the northeast, California to the west, Arizona to the southeast, and Utah to the east. Nevada is the seventh-most extensive, th ...

, where Ames joined him. He initiated divorce proceedings against Rosemary in a Reno court. The case was eventually heard in August 1923, with Mundy alleging that he wanted a divorce because Rosemary had deserted him. She denied the allegations, and the judge dismissed Talbot's case, adding that from the evidence Rosemary herself would be entitled to sue for divorce, which she nevertheless refused to do. Mundy meanwhile continued writing prolifically, producing 19 novel-length stories from 1921 through to the end of 1923, something that he found particularly tiring.

In November 1922, ''Adventure'' published Mundy's ''The Gray Mahatma'', which would later be republished under the title of ''Caves of Terror''. Taves described ''Caves of Terror'' as "a landmark in Mundy's career", being "one of ismost unusual and extraordinary novels". The work included characters such as King and Yasmini who had been a part of Mundy's early oeuvre, as well as more recently developed characters like Jeff Ramsden from his Jimgrim series.

It revealed Mundy's growing interest in Asian religion and also introduced a number of fantasy elements not present in his earlier work. The readers of ''Adventure'' voted it as their favourite novel of the year. At this time, he also exhibited his growing interest in esoteric

Western esotericism, also known as the Western mystery tradition, is a wide range of loosely related ideas and movements that developed within Western society. These ideas and currents are united since they are largely distinct both from orthod ...

ideas through the letters he published in ''Adventure'', in which he discussed his ideas about the Egyptian pyramids, the Lost Tribes of Israel, and the Ark of the Covenant

The Ark of the Covenant, also known as the Ark of the Testimony or the Ark of God, was a religious storage chest and relic held to be the most sacred object by the Israelites.

Religious tradition describes it as a wooden storage chest decorat ...

.

In 1922, Mundy and Ames moved to Truckee in California

California () is a U.S. state, state in the Western United States that lies on the West Coast of the United States, Pacific Coast. It borders Oregon to the north, Nevada and Arizona to the east, and shares Mexico–United States border, an ...

, although in October he travelled to San Diego

San Diego ( , ) is a city on the Pacific coast of Southern California, adjacent to the Mexico–United States border. With a population of over 1.4 million, it is the List of United States cities by population, eighth-most populous city in t ...

, remaining there for several months.

He had continued writing, producing ''The Nine Unknown'', a Jimgrim novel which again exhibited Mundy's interest in Indian religious ideas. Serialised in ''Adventure'' from March to April 1923, it was published by Bobbs-Merrill in March 1924 and then in Britain by Hutchinson in June. Taves however considered it to be "the most shallow and least satisfying of Mundy's fantasies". Mundy wanted to see the publication of popular editions of his novels, viewing this as a potential source of additional income and a good means of encouraging cinematic adaptations; in 1922 Bobbs-Merrill agreed, resulting in A. L. Burt Company publishing eight Mundy novels in two years. In the United Kingdom, Hutchinson published all but one of Mundy's then-written novels between 1922 and 1925.

Embracing Theosophy: 1922–27

In 1922, Mundy resigned from the Mother Church of Christian Science. He was increasingly interested in

In 1922, Mundy resigned from the Mother Church of Christian Science. He was increasingly interested in Theosophy

Theosophy is a religious movement established in the United States in the late 19th century. Founded primarily by the Russian Helena Blavatsky and based largely on her writings, it draws heavily from both older European philosophies such as Neop ...

, and on 1 January 1923 he joined the Theosophical Society Pasadena, with Ames joining later that month. He expressed the view that reading the works of Theosophy's co-founder Helena Blavatsky

Helena Petrovna Blavatsky (; – 8 May 1891), often known as Madame Blavatsky, was a Russian-born Mysticism, mystic and writer who emigrated to the United States where she co-founded the Theosophical Society in 1875. She gained an internat ...

"stirred in me something deeper and more challenging than I had known was there and capable of being stirred." He developed a close friendship with the groups' leader Katherine Tingley

Katherine Augusta Westcott Tingley (July 6, 1847 – July 11, 1929) was a social worker and prominent Theosophy (Blavatskian), Theosophist. She led the Theosophical Society Pasadena, American Section of the Theosophical Society after W. Q. Judge ...

, who invited him to live in her two-storey home, Wachere Crest, at the Theosophical community of Lomaland in San Diego

San Diego ( , ) is a city on the Pacific coast of Southern California, adjacent to the Mexico–United States border. With a population of over 1.4 million, it is the List of United States cities by population, eighth-most populous city in t ...

. At Lomaland, he immersed himself in the study of Theosophy, attending lectures and plays on the subject, and eventually appearing in some of these plays and giving his own lectures, coming to be recognised as one of the Society's most popular and charismatic public speakers.

In 1923, Mundy became part of Tingley's cabinet, a position normally reserved for Theosophical veterans; he remained an active member of the cabinet until after Tingley's death in 1929. Tingley invited him to contribute to ''The Theosophical Path'', with his first article in this magazine, devoted to his time in Jerusalem, appearing in the February 1923 issue. He would be a regular contributor to the magazine through 1924 and 1925, and would continue to do so with less frequency until 1929. He also wrote a preface for Tingley's 1925 book ''The Wine of Life''. In June 1924, Mundy and Sally relocated to Mérida, Yucatan in Mexico for six weeks. Under Mexican law, this residence allowed Mundy to secure a divorce from his third wife, which he did in July, marrying Ames the following day. Returning to San Diego, Mundy and Ames purchased a house near to Lomaland for $25,000 in late 1924. The house — which required much renovation — was named "Tilgaun" by the couple, who lived there with her son Dick.

At the recommendation of director Fred Niblo, whom Mundy had known in Africa, in early 1923 the producer Thomas H. Ince hired Mundy as a screenwriter. Mundy's first assignment for Ince was to write a novelization

A novelization (or novelisation) is a derivative novel that adapts the story of a work created for another medium, such as a film, TV series, stage play, comic book, or video game. Film novelizations were particularly popular before the advent ...

of the upcoming film, ''Her Reputation''; the book was published by Bobbs-Merrill, and in England by Hutchinson under the title ''The Bubble Reputation''. Mundy later expressed disdain for the novel, with his biographer Peter Berresford Ellis

Peter Berresford Ellis (born 10 March 1943) is a British historian, literary biographer, and novelist who has published over 98 books to date either under his own name or his pseudonyms Peter Tremayne and Peter MacAlan. He has also published 10 ...

describing it as "the worst book that Talbot ever wrote". For Ince, Mundy also produced a novelisation of a Western

Western may refer to:

Places

*Western, Nebraska, a village in the US

*Western, New York, a town in the US

*Western Creek, Tasmania, a locality in Australia

*Western Junction, Tasmania, a locality in Australia

*Western world, countries that id ...

film, ''When Trails Were New'', which dealt with the interactions between Native Americans and European settlers in the Wisconsin

Wisconsin ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Great Lakes region, Great Lakes region of the Upper Midwest of the United States. It borders Minnesota to the west, Iowa to the southwest, Illinois to the south, Lake Michigan to the east, Michig ...

woodlands of 1832. He later criticised the novel, with Taves describing it as "unquestionably one of Mundy's worst stories". Mundy continued to write his own stories; in December 1922, ''Adventure'' published Mundy's ''Benefit of Doubt'', which was followed by a sequel, ''Treason'', in January 1923. These stories involved the character of Athelstan King, and were set in the context of the Malabar rebellion which had taken place in Malabar in 1921. In December 1923, ''Adventure'' published Mundy's next Jimgrim story, ''Mohammed's Tooth'', which would later be republished as ''The Hundred Days''.

Mundy followed this with ''Om: The Secret of Ahbor Valley'', which was serialised in ''Adventure'' from October to November 1924, before publication by Bobbs-Merrill. The characters were based upon individuals that he knew at Lomaland, and the story expounded Theosophical ideas regarding the Masters and the existence of a universal "Ancient Wisdom". ''Adventure'' included a disclaimer at the start of the story stating that they did not endorse the esoteric movement. Ellis described the work as Mundy's "most significant novel", and his "literary masterpiece", while for Taves, it was "his most distinctly literary book, surpassing earlier novels by exhibiting a maturing skill in choice of language, plot structure, theme, depth of character." Mundy received hundreds of letters praising the work, and it also received good critical reviews from press. It proved popular among Theosophists, with Tingley asking Mundy if he would adapt it for one of her theaters. The British edition underwent six reprints in quick succession, while Swedish and German translations were soon commissioned for publication. At the prompting of several letters, Mundy began work on a sequel, ''Ramsden'', which appeared in ''Adventure'' in June 1926 before being published by Bobbs-Merrill under the title of ''The Devils Guard''. Upon publication it received good reviews. A third instalment in the trilogy, ''The Red Flame of Erinpura'', appeared in ''Adventure'' in 1927. Taves later noted that these three works reflected Theosophy's "most direct influence upon Mundy's writing", adding that in looking to Asia not only "for exoticism, but for wisdom and an alternative mode of living superior to Western habits", they "reinvigorated and revitalized fantasy-adventure literature".

Mundy then moved towards

Mundy followed this with ''Om: The Secret of Ahbor Valley'', which was serialised in ''Adventure'' from October to November 1924, before publication by Bobbs-Merrill. The characters were based upon individuals that he knew at Lomaland, and the story expounded Theosophical ideas regarding the Masters and the existence of a universal "Ancient Wisdom". ''Adventure'' included a disclaimer at the start of the story stating that they did not endorse the esoteric movement. Ellis described the work as Mundy's "most significant novel", and his "literary masterpiece", while for Taves, it was "his most distinctly literary book, surpassing earlier novels by exhibiting a maturing skill in choice of language, plot structure, theme, depth of character." Mundy received hundreds of letters praising the work, and it also received good critical reviews from press. It proved popular among Theosophists, with Tingley asking Mundy if he would adapt it for one of her theaters. The British edition underwent six reprints in quick succession, while Swedish and German translations were soon commissioned for publication. At the prompting of several letters, Mundy began work on a sequel, ''Ramsden'', which appeared in ''Adventure'' in June 1926 before being published by Bobbs-Merrill under the title of ''The Devils Guard''. Upon publication it received good reviews. A third instalment in the trilogy, ''The Red Flame of Erinpura'', appeared in ''Adventure'' in 1927. Taves later noted that these three works reflected Theosophy's "most direct influence upon Mundy's writing", adding that in looking to Asia not only "for exoticism, but for wisdom and an alternative mode of living superior to Western habits", they "reinvigorated and revitalized fantasy-adventure literature".

Mundy then moved towards historical fiction

Historical fiction is a literary genre in which a fictional plot takes place in the Setting (narrative), setting of particular real past events, historical events. Although the term is commonly used as a synonym for historical fiction literatur ...

.

His next main project was the "Tros Saga", a series of six novel-length stories which appeared in ''Adventure'' over the course of 1925. Set in Europe during the first century BCE, the eponymous Tros was a Samothracian pirate who combats the Roman military leader Julius Caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar (12 or 13 July 100 BC – 15 March 44 BC) was a Roman general and statesman. A member of the First Triumvirate, Caesar led the Roman armies in the Gallic Wars before defeating his political rival Pompey in Caesar's civil wa ...

, who in Mundy's novels had been responsible for the death of Tros' father. The series further reflected Mundy's Theosophical beliefs by presenting both the Samothracians and the druids

A druid was a member of the high-ranking priestly class in ancient Celtic cultures. The druids were religious leaders as well as legal authorities, adjudicators, lorekeepers, medical professionals and political advisors. Druids left no wr ...

as practitioners of the "Ancient Wisdom" religion that Theosophy propounded. Mundy's negative portrayal of Caesar caused controversy, with various letters being published in ''Adventures opinion section debating the accuracy of Mundy's portrayal, which included contributions from historical specialists in the period. The collected book, reaching 950 pages in length, was published in 1934 by Appleton-Century and Hutchinson, at which it proved both a critical and a commercial success.

Mundy remained with the Roman Empire for a novel focusing on the final months of the Emperor Commodus

Commodus (; ; 31 August 161 – 31 December 192) was Roman emperor from 177 to 192, first serving as nominal co-emperor under his father Marcus Aurelius and then ruling alone from 180. Commodus's sole reign is commonly thought to mark the end o ...

; it was serialised as ''The Falling Star'' by ''Adventure'' in October 1926 and later published in book form by Hutchinson as ''Caesar Dies'' in 1934. From 1925 to 1927 he also wrote ''Queen Cleopatra'', a lengthy novel that both Bobbs-Merrill and Hutchinson wanted edited down before they would publish it. Moving away from the Roman Empire, Mundy wrote ''W.H.: A Portion of the Record of Sir William Halifax'', a novel set in Tudor England which featured William Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 23 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's nation ...

as a supporting character. Mundy had difficulty finding a publisher for ''W.H.'', although it was eventually serialised as ''Ho for London Town!'' in ''Argosy All-Story Weekly'' in February 1929, followed by book publication as ''W.H.'' through Hutchinson in 1831.

Turning his attention to new business ventures, he joined a syndicate, the Sindicato de Desarrollo Liafail, who were planning on drilling for oil in Tijuana

Tijuana is the most populous city of the Mexican state of Baja California, located on the northwestern Pacific Coast of Mexico. Tijuana is the municipal seat of the Tijuana Municipality, the hub of the Tijuana metropolitan area and the most popu ...

, Mexico. Mundy became the syndicate's secretary, while another key member of the group was General Abelardo L. Rodríguez, who was then Governor of Baja California

Baja California, officially the Free and Sovereign State of Baja California, is a state in Mexico. It is the northwesternmost of the 32 federal entities of Mexico. Before becoming a state in 1952, the area was known as the North Territory of B ...

, and they also secured investment from Mexican President Plutarco Elías Calles