Tagantsev Conspiracy on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Tagantsev conspiracy (or the case of the Petrograd Military Organization) was a non-existent

After the initial failure, Yakov Agranov was appointed to lead the case. He arrested more people and took Tagantsev for interrogation after keeping him for 45 days in solitary confinement. Agranov gave an ultimatum; if Tagantsev did not confess, then he and all other hostages would be executed after three hours, however, no one would be harmed if he agreed to cooperate. According to publications by Russian emigrants, the agreement was even signed on paper and personally guaranteed by

After the initial failure, Yakov Agranov was appointed to lead the case. He arrested more people and took Tagantsev for interrogation after keeping him for 45 days in solitary confinement. Agranov gave an ultimatum; if Tagantsev did not confess, then he and all other hostages would be executed after three hours, however, no one would be harmed if he agreed to cooperate. According to publications by Russian emigrants, the agreement was even signed on paper and personally guaranteed by

The most famous victim of the case was the poet

The most famous victim of the case was the poet

Vladimir Tagantsev

on memorial book of persecuted geologists

Extended version in Russian)Diary of Vladimir Tagantsev

interview with Yuri Chernyaev on

summary

{{Authority control False flag operations Political and cultural purges Soviet Union intelligence operations Anti-intellectualism Red Terror

monarchist

Monarchism is the advocacy of the system of monarchy or monarchical rule. A monarchist is an individual who supports this form of government independently of any specific monarch, whereas one who supports a particular monarch is a royalist. C ...

conspiracy fabricated by the Soviet secret police

There were a succession of Soviet secret police agencies over time. The Okhrana was abolished by the Provisional government after the first revolution of 1917, and the first secret police after the October Revolution, created by Vladimir Leni ...

in 1921 to both decimate and terrorize potential Soviet dissidents

Soviet dissidents were people who disagreed with certain features of Soviet ideology or with its entirety and who were willing to speak out against them. The term ''dissident'' was used in the Soviet Union (USSR) in the period from the mid-1960 ...

against the ruling Bolshevik

The Bolsheviks, led by Vladimir Lenin, were a radical Faction (political), faction of the Marxist Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP) which split with the Mensheviks at the 2nd Congress of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party, ...

regime. Alexander N. Yakovlev, ''Century of Violence in Soviet Russia'', Yale University Press

Yale University Press is the university press of Yale University. It was founded in 1908 by George Parmly Day and Clarence Day, grandsons of Benjamin Day, and became a department of Yale University in 1961, but it remains financially and ope ...

(2002), pages 107-108, . As its result, more than 800 people, mostly from scientific and artistic communities in Petrograd (modern-day Saint Petersburg

Saint Petersburg, formerly known as Petrograd and later Leningrad, is the List of cities and towns in Russia by population, second-largest city in Russia after Moscow. It is situated on the Neva, River Neva, at the head of the Gulf of Finland ...

), were arrested on false terrorism charges, out of which 98 were executed and many were sent to labour camps. Among the executed was the poet Nikolay Gumilev

Nikolai Stepanovich Gumilev (also Gumilyov; , ; – August 26, 1921) was a Russian poet, literary critic, traveler, and military officer. He was a co-founder of the Acmeist movement. He was the husband of Anna Akhmatova and the father of Lev ...

, the co-founder of the influential Acmeist movement.

In 1992, all those convicted in the Petrograd Combat Organization (PBO) case were rehabilitated and the case was declared fabricated. However, in the 1990s, documents confirming the existence of the organization were introduced into scientific circulation.

The affair was named after Vladimir Nikolaevich Tagantsev, a geographer and member of the Russian Academy of Sciences

The Russian Academy of Sciences (RAS; ''Rossíyskaya akadémiya naúk'') consists of the national academy of Russia; a network of scientific research institutes from across the Russian Federation; and additional scientific and social units such ...

, who was arrested, tortured, and tricked into disclosing hundreds of names of people who did not like the Bolshevik regime. Among the security officers that manufactured the case was Yakov Agranov, who later became one of the chief organizers of Stalinist show trials and the Great Purge

The Great Purge, or the Great Terror (), also known as the Year of '37 () and the Yezhovshchina ( , ), was a political purge in the Soviet Union that took place from 1936 to 1938. After the Assassination of Sergei Kirov, assassination of ...

in the 1930s. The case was officially declared fabricated and its victims rehabilitated by Russian authorities in 1992.Vitaliy Shentalinsky, ''Crime Without Punishment'', Progress-Pleyada, Moscow, 2007, (Russian

Russian(s) may refer to:

*Russians (), an ethnic group of the East Slavic peoples, primarily living in Russia and neighboring countries

*A citizen of Russia

*Russian language, the most widely spoken of the Slavic languages

*''The Russians'', a b ...

: Виталий Шенталинский, "Преступление без наказания"), pages 197–288.

Background

On December 5, 1920, all departments of the Soviet secret policeCheka

The All-Russian Extraordinary Commission ( rus, Всероссийская чрезвычайная комиссия, r=Vserossiyskaya chrezvychaynaya komissiya, p=fsʲɪrɐˈsʲijskəjə tɕrʲɪzvɨˈtɕæjnəjə kɐˈmʲisʲɪjə, links=yes), ...

received a top secret order from Feliks Dzerzhinsky to start creating false flag

A false flag operation is an act committed with the intent of disguising the actual source of responsibility and pinning blame on another party. The term "false flag" originated in the 16th century as an expression meaning an intentional misrep ...

White Army

The White Army, also known as the White Guard, the White Guardsmen, or simply the Whites, was a common collective name for the armed formations of the White movement and Anti-Sovietism, anti-Bolshevik governments during the Russian Civil War. T ...

organizations, "underground and terrorist groups" to facilitate finding "foreign agents on our territory". This was planned partially as a provocation, in order to identify potentially disloyal citizens who might wish to join the Bolsheviks' enemies.

A few months later, in February 1921, the Kronstadt rebellion

The Kronstadt rebellion () was a 1921 insurrection of Soviet sailors, Marines, naval infantry, and civilians against the Bolsheviks, Bolshevik government in the Russian port city of Kronstadt. Located on Kotlin Island in the Gulf of Finland, ...

began. This was a left-wing uprising against the Bolshevik regime by soldiers and sailors. Additionally, the Bolsheviks understood that the majority of intelligentsia

The intelligentsia is a status class composed of the university-educated people of a society who engage in the complex mental labours by which they critique, shape, and lead in the politics, policies, and culture of their society; as such, the i ...

did not support them. On March 8, the Council of People's Commissars

The Council of People's Commissars (CPC) (), commonly known as the ''Sovnarkom'' (), were the highest executive (government), executive authorities of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic (RSFSR), the Soviet Union (USSR), and the Sovi ...

(Sovnarkom) send a letter to People's Commissariat for Education

The People's Commissariat for Education (or Narkompros; , directly translated as the "People's Commissariat for Enlightenment") was the Soviet agency charged with the administration of public education and most other issues related to culture. In 1 ...

(Narkompros) asking to identify a group of unreliable intellectuals who could be a target of future repressions.

On June 4, Bolshevik leader Vladimir Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov ( 187021 January 1924), better known as Vladimir Lenin, was a Russian revolutionary, politician and political theorist. He was the first head of government of Soviet Russia from 1917 until Death and state funeral of ...

received a telegram from Leonid Krasin

Leonid Borisovich Krasin (; – 24 November 1926) was a Russians, Russian Soviet Union, Soviet politician, engineer, social entrepreneur, Bolshevik revolutionary and a Soviet diplomat. In 1924 he became the first List of ambassadors of Russia to ...

about a convention of monarchists, cadets

A cadet is a student or trainee within various organisations, primarily in military contexts where individuals undergo training to become commissioned officers. However, several civilian organisations, including civil aviation groups, maritime o ...

and right-wing members of the Socialist-Revolutionary Party

The Socialist Revolutionary Party (SR; ,, ) was a major socialist political party in the late Russian Empire, during both phases of the Russian Revolution, and in early Soviet Russia. The party members were known as Esers ().

The SRs were ag ...

in Paris who anticipated an uprising against Bolsheviks in Petrograd. Lenin sent a telegram to Cheka co-founder Józef Unszlicht

Józef Unszlicht or Iosif Stanislavovich Unshlikht (; nicknames "Jurowski", "Leon"; 31 December 1879 – 29 July 1938) was a Polish and Russian revolutionary activist, a Soviet government official and one of the founders of the Cheka.

Biography ...

stating that he did not trust the Cheka in Petrograd any longer. In the telegram, he issued an order to urgently send "the most experienced Chekists to Piter" and find the conspirators. This was a signal for the Cheka in Petrograd to fabricate the case.

The case

On May 31, Yuri German, a former officer ofImperial Russian Army

The Imperial Russian Army () was the army of the Russian Empire, active from 1721 until the Russian Revolution of 1917. It was organized into a standing army and a state militia. The standing army consisted of Regular army, regular troops and ...

and a Finnish spy, was killed while crossing the Finnish border. He had a notebook with numerous addresses, one of which belonged to professor Vladimir Tagantsev, who was previously identified by Cheka agents as an "disloyal person". Tagantsev and other people whose addresses were found in the notebook were arrested. During the next month the investigators of Cheka worked hard to manufacture the case, but without much success. The arrested refused to admit any guilt. After intense interrogation, Tagantsev tried to hang himself on June 21. In addition, it was difficult to connect together so many completely unrelated people.

On June 25, two investigators of Petrograd Cheka, Gubin and Popov, prepared a report, according to which the "organization included only Tagantsev and a few couriers and supporters," the conspirators planned "to establish common language between intelligentsia and masses," the "terror was not their intention," and German delivered news about current events to Tagantsev from abroad. According to report, "the organization of Tagantsev had no connection and received no support from the Finnish or other counter-intelligence organizations." The report also noted that "Tagantsev is a cabinet scientist who thought about his organization theoretically" and "was incapable of doing practical work." After this report, names of Gubin and Popov disappeared from the case, meaning they have been replaced by other investigators.

After the initial failure, Yakov Agranov was appointed to lead the case. He arrested more people and took Tagantsev for interrogation after keeping him for 45 days in solitary confinement. Agranov gave an ultimatum; if Tagantsev did not confess, then he and all other hostages would be executed after three hours, however, no one would be harmed if he agreed to cooperate. According to publications by Russian emigrants, the agreement was even signed on paper and personally guaranteed by

After the initial failure, Yakov Agranov was appointed to lead the case. He arrested more people and took Tagantsev for interrogation after keeping him for 45 days in solitary confinement. Agranov gave an ultimatum; if Tagantsev did not confess, then he and all other hostages would be executed after three hours, however, no one would be harmed if he agreed to cooperate. According to publications by Russian emigrants, the agreement was even signed on paper and personally guaranteed by Vyacheslav Menzhinsky

Vyacheslav Rudolfovich Menzhinsky (, ; – 10 May 1934) was a Soviet revolutionary and politician who served as chairman of the OGPU, the secret police of the Soviet Union, from 1926 to 1934.

Born to Polish parents in Saint Petersburg, Menzhins ...

. After signing the agreement, Tagantsev called names of several hundred people who criticized the Bolshevik regime. All of them were arrested on July 31 and during the first days of August.

According to official version invented by Agranov, the leaders of conspiracy included Tagantsev, Finnish spy German, and former colonel of Russian army Vycheslav Shvedov who acted under pseudonym "Vyacheslavsky" and shot two Chekists during his arrest. To make the conspiracy bigger, they included many completely unrelated people, including former aristocrats, contrabandists, suspicious people and wives of those who were already arrested. The newspaper ''The Petrograd Pravda'' published a report by the Petrograd Cheka that the military organization of Tagantsev planned to burn plants, kill people and commit other terrorism acts using weapons and dynamite.

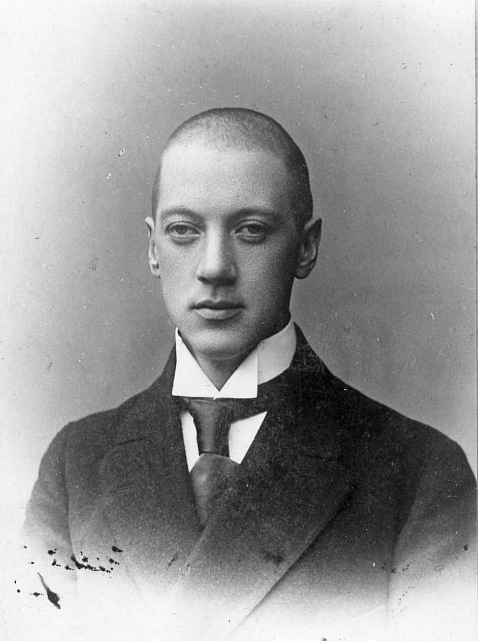

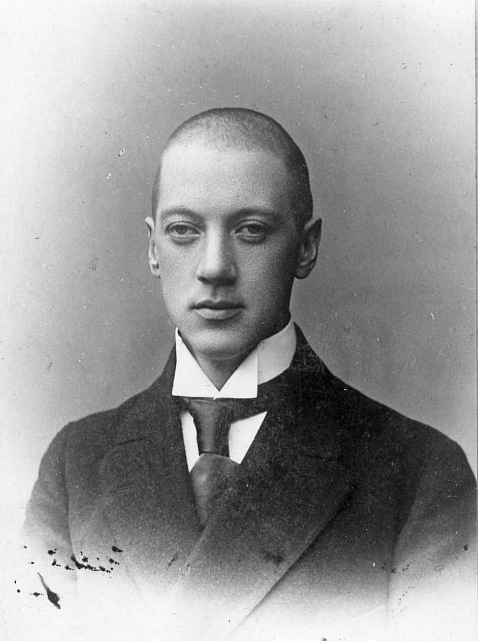

The most famous victim of the case was the poet

The most famous victim of the case was the poet Nikolay Gumilev

Nikolai Stepanovich Gumilev (also Gumilyov; , ; – August 26, 1921) was a Russian poet, literary critic, traveler, and military officer. He was a co-founder of the Acmeist movement. He was the husband of Anna Akhmatova and the father of Lev ...

. Gumilev was arrested by Cheka on August 3. He admitted that he thought about joining the Kronstadt rebellion if it were to spread to Petrograd and talked about this with Vyacheslavsky. Gumilev was executed by a firing squad, together with 60 other people on August 24 in the Kovalevsky Forest. Thirty-seven others were shot on October 3.Shentalinsky, page 278.Vadim J. Birstein, ''The Perversion Of Knowledge: The True Story of Soviet Science'', Westview Press (2004) , pages 28-33. Agranov commented about the operation: "Seventy percent of the Petrograd intelligentsia had one leg in the enemy camp. We had to burn that leg."Vitaliy Shentalinsky, page 214.

Aftermath

The action reportedly failed to terrify the population. According to academicianVladimir Vernadsky

Vladimir Ivanovich Vernadsky (), also spelt Volodymyr Ivanovych Vernadsky (; – 6 January 1945), was a Russian, Ukrainian, and Soviet mineralogist and geochemist who is considered one of the founders of geochemistry, biogeochemistry, and radio ...

, the case "had a shocking effect and produced not a feeling of fear, but of hatred and contempt" against the Bolsheviks. After the Tagantsev case Lenin decided that it would be easier to exile undesired intellectuals.

See also

* Prompartiya *Active measures

Active measures () is a term used to describe political warfare conducted by the Soviet Union and the Russian Federation. The term, which dates back to the 1920s, includes operations such as espionage, propaganda, sabotage and assassination, b ...

*Red terror

The Red Terror () was a campaign of political repression and Mass killing, executions in Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic, Soviet Russia which was carried out by the Bolsheviks, chiefly through the Cheka, the Bolshevik secret police ...

*Operation Trust

Operation Trust () was a counterintelligence operation of the State Political Directorate (GPU) of the Soviet Union. The operation, which was set up by GPU's predecessor Cheka, ran from 1921 to 1927, set up a fake anti-Bolshevik resistance organi ...

* Syndicate-2

References

External links

Vladimir Tagantsev

on memorial book of persecuted geologists

Extended version in Russian)

interview with Yuri Chernyaev on

RFERL

Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty (RFE/RL) is a media organization broadcasting news and analyses in 27 languages to 23 countries across Eastern Europe, Central Asia, the Caucasus, and the Middle East. Headquartered in Prague since 1995, RFE/RL ...

, and itsummary

{{Authority control False flag operations Political and cultural purges Soviet Union intelligence operations Anti-intellectualism Red Terror