Syama Prasad Mukherjee on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Syama Prasad Mookerjee (6 July 1901 – 23 June 1953) was an Indian barrister, educationist, politician, activist, social worker, and a minister in the state and national governments. Noted for his opposition to Quit India movement within the independence movement in India, he later served as India's first Minister for Industry and Supply (currently known as Minister of Commerce and Industries) in Prime Minister

Mukherjee joined the

Mukherjee joined the

Prime Minister

Prime Minister

Mukherjee was arrested upon entering Kashmir on 11 May 1953. He and two of his arrested companions were first taken to Central Jail of

Mukherjee was arrested upon entering Kashmir on 11 May 1953. He and two of his arrested companions were first taken to Central Jail of

On 22 April 2010, the

On 22 April 2010, the  In 2012, a flyover at Mathikere in

In 2012, a flyover at Mathikere in

Excerpts from convocation address at Benares Hindu University (1 December 1940)

{{DEFAULTSORT:Mukherjee, Syama Prasad 1901 births 1953 deaths India MPs 1952–1957 20th-century Indian lawyers Bengali Hindus Bengali lawyers Bengali activists Alumni of the Inns of Court School of Law Presidency University, Kolkata alumni First Nehru ministry Hindu martyrs Indian political party founders Indian barristers Indian activists Politicians from Kolkata Vice-chancellors of the University of Calcutta Indian National Congress politicians from West Bengal Hindu Mahasabha politicians Bharatiya Jana Sangh politicians Members of the Constituent Assembly of India Lok Sabha members from West Bengal Indian people who died in prison custody Presidents of The Asiatic Society Scholars from Kolkata University of Calcutta alumni Commerce and industry ministers of India Founders of Indian schools and colleges Bengal MLAs 1937–1945 Bengal MLAs 1946–1947 West Bengal MLAs 1947–1951

Jawaharlal Nehru

Jawaharlal Nehru (14 November 1889 – 27 May 1964) was an Indian anti-colonial nationalist, secular humanist, social democrat, and statesman who was a central figure in India during the middle of the 20th century. Nehru was a pr ...

's cabinet after breaking up with the Hindu Mahasabha

Akhil Bharatiya Hindu Mahasabha (), simply known as Hindu Mahasabha, is a Hindu nationalism, Hindu nationalist political party in India.

Founded in 1915 by Madan Mohan Malviya, the Mahasabha functioned mainly as a pressure group advocating th ...

. After falling out with Nehru, protesting against the Liaquat–Nehru Pact, Mukherjee resigned from Nehru's cabinet. With the help of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh

The Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS,, ) is an Indian right-wing politics, right-wing, Hindutva, Hindu nationalist volunteer paramilitary organisation. It is the progenitor and leader of a large body of organisations called the Sangh Parivar ( ...

, he founded the Bharatiya Jana Sangh

The Akhil Bharatiya Jana Sangh ( BJS or JS, short name: Jan Sangh) was a Hindutva political party active in India. It was established on 21 October 1951 in Delhi by three founding members: Shyama Prasad Mukherjee, Balraj Madhok and Deendayal ...

, the predecessor to the Bharatiya Janata Party

The Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP; , ) is a political party in India and one of the two major List of political parties in India, Indian political parties alongside the Indian National Congress. BJP emerged out from Syama Prasad Mukherjee's ...

, in 1951.

He was also the president of Akhil Bharatiya Hindu Mahasabha from 1943 to 1946. He was arrested by the Jammu and Kashmir Police in 1953 when he tried to cross the border of the state. He was provisionally diagnosed with a heart attack

A myocardial infarction (MI), commonly known as a heart attack, occurs when Ischemia, blood flow decreases or stops in one of the coronary arteries of the heart, causing infarction (tissue death) to the heart muscle. The most common symptom ...

and shifted to a hospital but died a day later. Since the Bharatiya Janata Party is the successor to the Bharatiya Jana Sangh

The Akhil Bharatiya Jana Sangh ( BJS or JS, short name: Jan Sangh) was a Hindutva political party active in India. It was established on 21 October 1951 in Delhi by three founding members: Shyama Prasad Mukherjee, Balraj Madhok and Deendayal ...

, Mookerjee is also regarded as the founder of the Bharatiya Janata Party

The Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP; , ) is a political party in India and one of the two major List of political parties in India, Indian political parties alongside the Indian National Congress. BJP emerged out from Syama Prasad Mukherjee's ...

(BJP) by its members.

Early life and academic career

Syama Mukherjee was born during theBritish Raj

The British Raj ( ; from Hindustani language, Hindustani , 'reign', 'rule' or 'government') was the colonial rule of the British The Crown, Crown on the Indian subcontinent,

*

* lasting from 1858 to 1947.

*

* It is also called Crown rule ...

on 6 July 1901 in Calcutta, now located in the West Bengal

West Bengal (; Bengali language, Bengali: , , abbr. WB) is a States and union territories of India, state in the East India, eastern portion of India. It is situated along the Bay of Bengal, along with a population of over 91 million inhabi ...

state of India. His grandfather Ganga Prasad Mukherjee was born in Jirat

Jirat is a census town located in Hooghly district, Hooghly District in the Indian States and territories of India, State of West Bengal.

Geography

Location

Jirat is situated under Balagarh (community development block), Balagarh Block. Ba ...

and was the first in the family who migrated to and settled in Calcutta.

Syama Prasad's father was Ashutosh Mukherjee

Sir Ashutosh Mukherjee (anglicised, originally Asutosh Mukhopadhyay, also anglicised to Asutosh Mookerjee) (29 June 1864 – 25 May 1924) was a Bengali mathematician, lawyer, jurist, judge, educator, and institution builder. A unique figure i ...

, a judge of the High Court of Calcutta, Bengal Presidency

The Bengal Presidency, officially the Presidency of Fort William in Bengal until 1937, later the Bengal Province, was the largest of all three presidencies of British India during Company rule in India, Company rule and later a Provinces o ...

, and was also the Vice-Chancellor

A vice-chancellor (commonly called a VC) serves as the chief executive of a university in the United Kingdom, New Zealand, Australia, Nepal, India, Bangladesh, Malaysia, Nigeria, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, South Africa, Kenya, other Commonwealth of Nati ...

of the University of Calcutta

The University of Calcutta, informally known as Calcutta University (), is a Public university, public State university (India), state university located in Kolkata, Calcutta (Kolkata), West Bengal, India. It has 151 affiliated undergraduate c ...

. His mother was Jogamaya Devi Mukherjee. was a very meritorious student and he came to Calcutta to study in Medical College

A medical association or medical college is a trade association that brings together practitioners of a particular geographical area (a country, region, province). In common-law countries, they are often grouped by medical specialties ( cardiolog ...

with the help of the wealthy people of Jirat. Later he settled down in the Bhawanipore area of Calcutta.Ghatak, Atulchandra, ''Ashutosher Chatrajiban Ed. 8th'', 1954, p 1, Chakraborty Chatterjee & Co. Ltd.

Syama Prasad enrolled in Bhawanipur's Mitra Institution in 1906 and his behaviour in school was later described favourably by his teachers. In 1914, he passed his matriculation

Matriculation is the formal process of entering a university, or of becoming eligible to enter by fulfilling certain academic requirements such as a matriculation examination.

Australia

In Australia, the term ''matriculation'' is seldom used no ...

examination and was admitted into Presidency College. He stood seventeenth in the Inter Arts Examination in 1916 and graduated in English, securing the first position in first class in 1921. He was married to Sudha Devi on 16 April 1922. Mukherjee also completed an MA in Bengali, being graded as first class in 1923 and also became a fellow of the Senate

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior (Latin: ''senex'' meaning "the el ...

of the University of Calcutta

The University of Calcutta, informally known as Calcutta University (), is a Public university, public State university (India), state university located in Kolkata, Calcutta (Kolkata), West Bengal, India. It has 151 affiliated undergraduate c ...

in 1923. He completed his LLB in 1924.

He enrolled as an advocate in Calcutta High Court in 1924, the same year in which his father had died. Subsequently, he left for England in 1926 to study at Lincoln's Inn

The Honourable Society of Lincoln's Inn, commonly known as Lincoln's Inn, is one of the four Inns of Court (professional associations for Barrister, barristers and judges) in London. To be called to the bar in order to practise as a barrister ...

and was called to the English Bar in the same year. In 1934, at the age of 33, he became the youngest Vice-Chancellor of the University of Calcutta; he held the office until 1938. During his term as Vice-Chancellor, Rabindranath Tagore

Rabindranath Thakur (; anglicised as Rabindranath Tagore ; 7 May 1861 – 7 August 1941) was a Bengalis, Bengali polymath who worked as a poet, writer, playwright, composer, philosopher, social reformer, and painter of the Bengal Renai ...

delivered the University Convocation Address in Bengali for the first time, and the Indian vernacular was introduced as a subject for the highest examination. On 10 September 1938, the Senate of Calcutta University resolved to confer honorary D.Litt. on the Ex-Vice Chancellor in its opinion "by reason of eminent position and attainments, a fit and proper person to receive such a degree." Mukherjee received the D.Litt from Calcutta University on 26 November 1938. He was also the 15th President of the Association of Indian Universities during 1941-42.

Political career before independence

He started his political career in 1929 when he entered the Bengal Legislative Council as anIndian National Congress

The Indian National Congress (INC), colloquially the Congress Party, or simply the Congress, is a political parties in India, political party in India with deep roots in most regions of India. Founded on 28 December 1885, it was the first mo ...

(INC) candidate representing Calcutta University. However, he resigned the next year when the INC decided to boycott the legislature. Subsequently, he contested the election

An election is a formal group decision-making process whereby a population chooses an individual or multiple individuals to hold Public administration, public office.

Elections have been the usual mechanism by which modern representative d ...

as an independent candidate

An independent politician or non-affiliated politician is a politician not affiliated with any political party or bureaucratic association. There are numerous reasons why someone may stand for office as an independent.

Some politicians have polit ...

and was elected in the same year. In 1937

Events

January

* January 1 – Anastasio Somoza García becomes President of Nicaragua.

* January 5 – Water levels begin to rise in the Ohio River in the United States, leading to the Ohio River flood of 1937, which continues into Feb ...

, he was elected as an independent candidate in the elections which brought the Krishak Praja Party

The Krishak Sramik Party (, ''Farmer Labourer Party'') was a major anti-feudal political party in the British Indian province of Bengal and later in the Dominion of Pakistan's East Bengal and East Pakistan provinces. It was founded in 1929 as th ...

to power.

He served as the Finance Minister of Bengal Province in 1941–42 under A.K. Fazlul Haq's Progressive Coalition government which was formed on 12 December 1941 after the resignations of the Congress government. During his tenure, his statements against the government were censored and his movements were restricted. He was also prevented from visiting the Midnapore district

Midnapore (Pron: mad̪aːniːpur), or sometimes Medinipur, is a former district in the Indian state of West Bengal, headquartered in Midnapore. On 1 January 2002, the district was bifurcated into two separate districts namely Purba Medinipur ...

in 1942 when severe floods caused a heavy loss of life and property. He resigned on 20 November 1942 accusing the British government of trying to hold on to India at any cost and criticised its repressive policies against the Quit India Movement. After resigning, he mobilised to support and organised relief with the help of the Mahabodhi Society

The Maha Bodhi Society is a South Asian Buddhism, Buddhist society presently based in Kolkata, India. Founded by the Sri Lankan Buddhist leader Anagarika Dharmapala and the British journalist and poet Sir Edwin Arnold, its first office was in Bodh ...

, Ramakrishna Mission

Ramakrishna Math and Ramakrishna Mission (RKM) is a spiritual and philanthropic organisation headquartered in Belur Math, West Bengal. The mission is named after the Indian Hindu spiritual guru and mystic Ramakrishna. The mission was founde ...

and Marwari Relief Society. In 1946

1946 (Roman numerals, MCMXLVI) was a common year starting on Tuesday of the Gregorian calendar, the 1946th year of the Common Era (CE) and ''Anno Domini'' (AD) designations, the 946th year of the 2nd millennium, the 46th year of the 20th centur ...

, he was again elected as an independent candidate from Calcutta University. He was elected as a member of the Constituent Assembly of India

Constituent Assembly of India was partly elected and partly nominated body to frame the Constitution of India. It was elected by the Provincial assemblies of British India following the Provincial Assembly elections held in 1946 and nominated ...

in the same year.

Hindu Mahasabha and Bengali Hindu Homeland Movement

Mukherjee joined the

Mukherjee joined the Hindu Mahasabha

Akhil Bharatiya Hindu Mahasabha (), simply known as Hindu Mahasabha, is a Hindu nationalism, Hindu nationalist political party in India.

Founded in 1915 by Madan Mohan Malviya, the Mahasabha functioned mainly as a pressure group advocating th ...

in Bengal in 1939 and became its acting president

An acting president is a person who temporarily fills the role of a country's president when the incumbent president is unavailable (such as by illness or visiting abroad) or when the post is vacant (such as for death

Death is the en ...

that same year. He was appointed as the working president of the organisation in 1940. In February 1941, Mukherjee told a Hindu

Hindus (; ; also known as Sanātanīs) are people who religiously adhere to Hinduism, also known by its endonym Sanātana Dharma. Jeffery D. Long (2007), A Vision for Hinduism, IB Tauris, , pp. 35–37 Historically, the term has also be ...

rally that if Muslims wanted to live in Pakistan they should "pack their bag and baggage and leave India ... owherever they like".Legislative Council Proceedings LCP 1941, Vol. LIX, No. 6, p 216 Yet, the Hindu Mahasabha also formed provincial coalition governments with the All-India Muslim League

The All-India Muslim League (AIML) was a political party founded in 1906 in Dhaka, British India with the goal of securing Muslims, Muslim interests in South Asia. Although initially espousing a united India with interfaith unity, the Muslim L ...

in Sindh

Sindh ( ; ; , ; abbr. SD, historically romanized as Sind (caliphal province), Sind or Scinde) is a Administrative units of Pakistan, province of Pakistan. Located in the Geography of Pakistan, southeastern region of the country, Sindh is t ...

and the North-West Frontier Province

The North-West Frontier Province (NWFP; ) was a province of British India from 1901 to 1947, of the Dominion of Pakistan from 1947 to 1955, and of the Pakistan, Islamic Republic of Pakistan from 1970 to 2010. It was established on 9 November ...

while Mukherjee was its leader. He was elected as the President of Akhil Bharatiya Hindu Mahasabha in 1943. He remained in this position till 1946, with Laxman Bhopatkar becoming the new president in the same year.

Mukherjee demanded the partition of Bengal in 1946 to prevent the inclusion of its Hindu-majority areas in a Muslim-dominated East Pakistan

East Pakistan was the eastern province of Pakistan between 1955 and 1971, restructured and renamed from the province of East Bengal and covering the territory of the modern country of Bangladesh. Its land borders were with India and Burma, wit ...

. A meeting held by the Mahasabha on 15 April 1947 in Tarakeswar authorised him to take steps for ensuring the partition of Bengal. In May 1947, he wrote a letter to Lord Mountbatten

Admiral of the Fleet (Royal Navy), Admiral of the Fleet Louis Francis Albert Victor Nicholas Mountbatten, 1st Earl Mountbatten of Burma (born Prince Louis of Battenberg; 25 June 1900 – 27 August 1979), commonly known as Lord Mountbatten, was ...

telling him that Bengal must be partitioned even if India was not. He also opposed a failed bid for a united but independent Bengal made in 1947 by Sarat Bose, the brother of Subhas Chandra Bose

Subhas Chandra Bose (23 January 1897 – 18 August 1945) was an Indian independence movement, Indian nationalist whose defiance of British raj, British authority in India made him a hero among many Indians, but his wartime alliances with ...

, and Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy

Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy (8 September 18925 December 1963) was an East Pakistani barrister, politician and statesman who served as the Prime Minister of Pakistan from 1956 to 1957 and before that as the Prime Minister of Bengal from 1946 to ...

, a Bengali Muslim

Bengali Muslims (; ) 'Mussalman'' also used in this work./ref> are adherents of Islam who ethnically, linguistically and genealogically identify as Bengalis. Comprising over 70% of the global Bengali population, they are the second-largest ...

politician. His views were strongly affected by the Noakhali genocide in East Bengal

East Bengal (; ''Purbô Bangla/Purbôbongo'') was the eastern province of the Dominion of Pakistan, which covered the territory of modern-day Bangladesh. It consisted of the eastern portion of the Bengal region, and existed from 1947 until 195 ...

, where mobs belonging to the Muslim League massacred Hindus.

It was Mukherjee who launched the Bengali Hindu Homeland Movement. It refers to the movement of the Bengali Hindu people for the Partition of Bengal in 1947 to create a homeland aka West Bengal for themselves within the Indian Union, in the wake of the Muslim League's proposal and campaign to include the entire province of Bengal within Pakistan, which was to be a homeland for the Muslims of British India.

Opposition to Quit India Movement

Following the Hindu Mahasabha's official decision to boycott the Quit India movement and theRashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh

The Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS,, ) is an Indian right-wing politics, right-wing, Hindutva, Hindu nationalist volunteer paramilitary organisation. It is the progenitor and leader of a large body of organisations called the Sangh Parivar ( ...

's decision of non-participation in the movement.

Mukherjee wrote a letter to Sir John Herbert, Governor of Bengal

In 1644, Gabriel Boughton procured privileges for the East India Company which permitted them to build a factory at Hooghly district, Hughli, without fortifications. Various chief agents, Governors and presidents were appointed to look after co ...

as to how they should respond to "Quit India" movement. In this letter, dated 26 July 1942 he wrote:

Let me now refer to the situation that may be created in the province as a result of any widespread movement launched by the Congress. Anybody, who during the war, plans to stir up mass feeling, resulting in internal disturbances or insecurity, must be resisted by any Government that may function for the time beingMukherjee in this letter reiterated that the Fazlul Haq-led Bengal Government, along with its alliance partner Hindu Mahasabha would make every possible effort to defeat the Quit India Movement in the province of Bengal and made a concrete proposal in regard to this:

The question is how to combat this movement (Quit India) in Bengal? The administration of the province should be carried on in such a manner that despite the best efforts of the Congress, this movement will fail to take root in the province. It should be possible for us, especially responsible Ministers, to be able to tell the public that the freedom for which the Congress has started the movement, already belongs to the representatives of the people. In some spheres, it might be limited during an emergency. Indians have to trust the British, not for the sake of Britain, not for any advantage that the British might gain, but for the maintenance of the defense and freedom of the province itself. You, as Governor, will function as the constitutional head of the province and will be guided entirely on the advice of your Minister.The Indian historian R.C. Majumdar noted this fact and stated:

Shyam Prasad ended the letter with a discussion of the mass movement organised by Congress. He expressed the apprehension that the movement would create internal disorder and endanger internal security during the war by exciting popular feeling and he opined that any government in power has to suppress it, but that according to him could not be done only by persecution... In that letter, he mentioned item-wise the steps to be taken for dealing with the situation...During Mukherjee's resignation speech, however, he characterised the policies of the British government towards the movement as "repressive".

Political career after independence

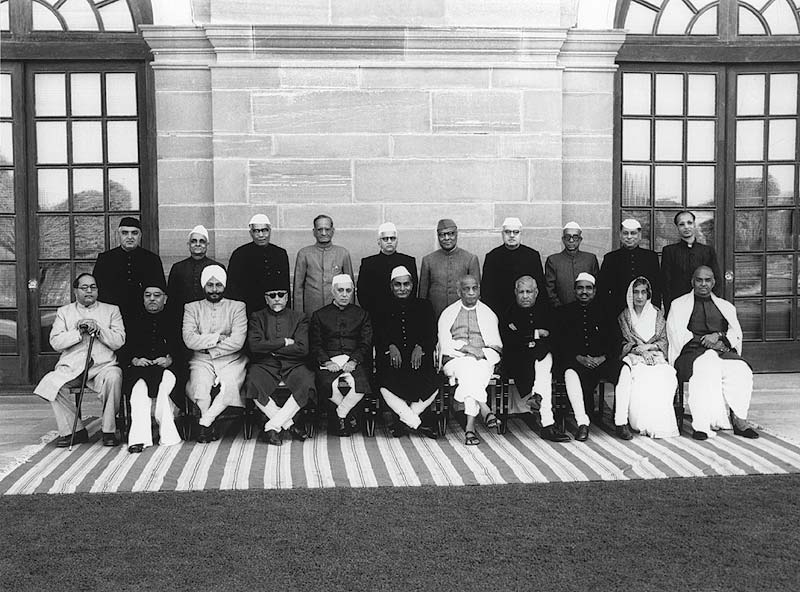

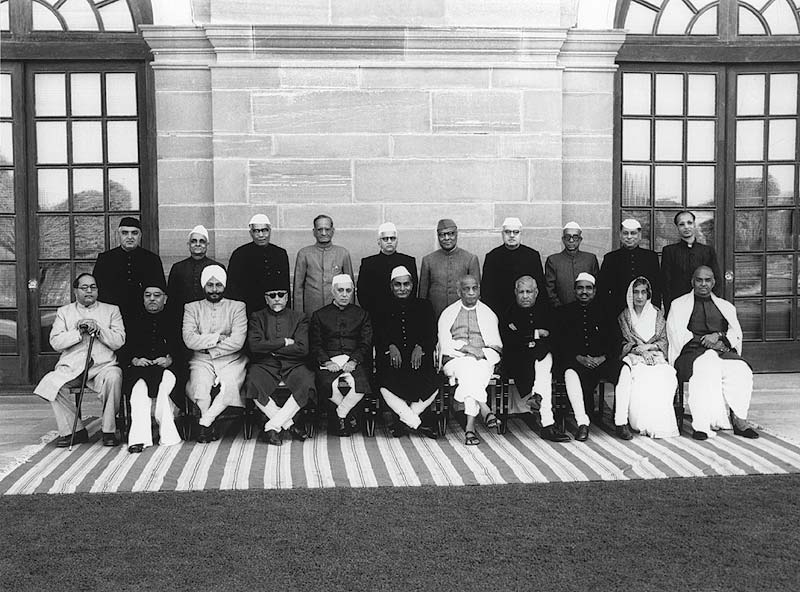

Prime Minister

Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru

Jawaharlal Nehru (14 November 1889 – 27 May 1964) was an Indian anti-colonial nationalist, secular humanist, social democrat, and statesman who was a central figure in India during the middle of the 20th century. Nehru was a pr ...

inducted Mukherjee into the Interim Central Government as a Minister for Industry and Supply on 15 August 1947.

Mukherjee condemned the assassination of Mahatma Gandhi

Mahatma Gandhi was assassinated on 30 January 1948 at age 78 in the compound of The Birla House (now Gandhi Smriti), a large mansion in central New Delhi. His assassin was Nathuram Godse, from Pune, Maharashtra, a Hindu nationalist, with ...

as the "most stunning blow that could fall on India. That he who had made India free and self-reliant, a friend of all and enemy of none, loved and respected by millions, should fall at the hands of an assassin, one of his community and countrymen, is a matter of the deepest shame and tragedy." He began to have differences with Hindu Mahasabha after Gandhi's killing, in which the Mahasabha was blamed by Vallabhbhai Patel

Vallabhbhai Jhaverbhai Patel (; ''Vallabhbhāī Jhāverbhāī Paṭel''; 31 October 1875 – 15 December 1950), commonly known as Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel, was an Indian independence activist and statesman who served as the first Deputy Prime ...

for creating the atmosphere that led to the killing. Mukherjee suggested the organisation suspend its political activities. Shortly after it did, in December 1948, he left. One of his reasons was the rejection of his proposal to allow non-Hindus to become members. Mukherjee resigned along with K.C. Neogy from the Cabinet on 8 April 1950 over a disagreement about the 1950 Delhi Pact with Pakistani Prime Minister Liaquat Ali Khan

Liaquat Ali Khan (1 October 189516 October 1951) was a Pakistani lawyer, politician and statesman who served as the first prime minister of Pakistan

The prime minister of Pakistan (, Roman Urdu, romanized: Wazīr ē Aʿẓam , ) is the he ...

.

Mukherjee was firmly against their joint pact to establish minority commissions and guarantee minority rights in both countries as he thought it left Hindus in East Bengal to the mercy of Pakistan. While addressing a rally in Calcutta on 21 May, he stated that an exchange of population and property at the governmental level on a regional basis between East Bengal and the states of Tripura

Tripura () is a States and union territories of India, state in northeastern India. The List of states and union territories of India by area, third-smallest state in the country, it covers ; and the seventh-least populous state with a populat ...

, Assam

Assam (, , ) is a state in Northeast India, northeastern India, south of the eastern Himalayas along the Brahmaputra Valley, Brahmaputra and Barak River valleys. Assam covers an area of . It is the second largest state in Northeast India, nor ...

, West Bengal

West Bengal (; Bengali language, Bengali: , , abbr. WB) is a States and union territories of India, state in the East India, eastern portion of India. It is situated along the Bay of Bengal, along with a population of over 91 million inhabi ...

and Bihar

Bihar ( ) is a states and union territories of India, state in Eastern India. It is the list of states and union territories of India by population, second largest state by population, the List of states and union territories of India by are ...

was the only option in the current situation.

Mukherjee founded the Bharatiya Jana Sangh on 21 October 1951 in Delhi, becoming its first president. In the 1952 elections, the Bharatiya Jana Sangh

The Akhil Bharatiya Jana Sangh ( BJS or JS, short name: Jan Sangh) was a Hindutva political party active in India. It was established on 21 October 1951 in Delhi by three founding members: Shyama Prasad Mukherjee, Balraj Madhok and Deendayal ...

(BJS) won three seats in the Parliament of India

The Parliament of India (ISO 15919, ISO: ) is the supreme legislative body of the Government of India, Government of the Republic of India. It is a bicameralism, bicameral legislature composed of the Rajya Sabha (Council of States) and the Lok ...

, including Mukherjee's. He had formed the National Democratic Party within the Parliament. It consisted of 32 members

Member may refer to:

* Military jury, referred to as "Members" in military jargon

* Element (mathematics), an object that belongs to a mathematical set

* In object-oriented programming, a member of a class

** Field (computer science), entries in ...

of the Lok Sabha and 10 members

Member may refer to:

* Military jury, referred to as "Members" in military jargon

* Element (mathematics), an object that belongs to a mathematical set

* In object-oriented programming, a member of a class

** Field (computer science), entries in ...

of the Rajya Sabha

Rajya Sabha (Council of States) is the upper house of the Parliament of India and functions as the institutional representation of India’s federal units — the states and union territories.https://rajyasabha.nic.in/ It is a key component o ...

; however, it was not recognised by the speaker as an opposition party. The BJS was created with the objective of nation-building

Nation-building is constructing or structuring a national identity using the power of the state. Nation-building aims at the unification of the people within the state so that it remains politically stable and viable. According to Harris Mylonas, ...

and nationalising all non-Hindus by "inculcating Indian Culture" in them. The party was ideologically close to the RSS and widely considered the proponent of Hindu nationalism

Hindu nationalism has been collectively referred to as the expression of political thought, based on the native social and cultural traditions of the Indian subcontinent. "Hindu nationalism" is a simplistic translation of . It is better descri ...

.

Opinion on special status of Jammu and Kashmir

After having supported Article 370 during the parliamentary discussions over the legislation, Mukherjee became opposed to the legislation after falling out with Nehru. He fought against it inside and outside the parliament with one of the goals of Bharatiya Jana Sangh being its abrogation. He raised his voice against the provision in his Lok Sabha speech on 26 June 1952. He termed the arrangements under the article as theBalkanization

Balkanization or Balkanisation is the process involving the fragmentation of an area, country, or region into multiple smaller and hostile units. It is usually caused by differences in ethnicity, culture, religion, and geopolitical interests.

...

of India and the three-nation theory of Sheikh Abdullah

Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah (5 December 1905 – 8 September 1982) was an Indian politician who played a central role in the politics of Jammu and Kashmir. Abdullah was the founding leader and President of the All Jammu and Kashmir Muslim Confer ...

. The state was granted its flag along with a prime minister whose permission was required for anyone to enter the state. In opposition to this, Mukherjee once said ''"Ek desh mein do Vidhan, do Pradhan aur Do Nishan nahi chalenge"'' (A single country can't have two constitutions

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organization or other type of entity, and commonly determines how that entity is to be governed.

When these princ ...

, two prime ministers

A prime minister or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. A prime minister is not the head of state, but rat ...

, and two national emblems

These are lists of national symbols:

*List of national animals

*List of national anthems

*List of national birds

*List of national dances

*Armorial of sovereign states, List of national emblems

*Gallery of sovereign state flags, List of national fl ...

). Bharatiya Jana Sangh along with Hindu Mahasabha and Jammu Praja Parishad launched a massive Satyagraha to get the provisions removed. In his letter to Nehru dated 3 February 1953, he wrote that the issue of accession of Jammu and Kashmir to India should not be delayed, to which Nehru responded by referring to international complications the issue could create.

Mukherjee went to visit Kashmir in 1953 and observed a hunger strike to protest the law that prohibited Indian citizens from settling within the state and mandating that they carry ID cards. Mukherjee wanted to go to Jammu and Kashmir but, because of the prevailing permit system, he was not given permission. He was arrested on 11 May at Lakhanpur while crossing the border into Kashmir illegally. Although the ID card rule was revoked owing to his efforts, he died as a detainee on 23 June 1953.

On 5 August 2019, when the Government of India proposed a constitutional Amendment to repeal Article 370, many BJP members described the event as realisation of Syama Prasad Mukherjee's dream.

Personal life

Syama Prasad had three brothers who were; Rama Prasad who was born in 1896, Uma Prasad who was born in 1902 and Bama Prasad Mukherjee who was born in 1906. Rama Prasad became a judge in the High Court of Calcutta, while Uma became famed as a trekker and a travel writer. He also had three sisters; Kamala who was born in 1895, Amala who was born in 1905 and Ramala in 1908. He was married in 1922 to Sudha Devi for 11 years and had five children – the last one, a four-month-old son, died fromdiphtheria

Diphtheria is an infection caused by the bacteria, bacterium ''Corynebacterium diphtheriae''. Most infections are asymptomatic or have a mild Course (medicine), clinical course, but in some outbreaks, the mortality rate approaches 10%. Signs a ...

. His wife died of double pneumonia shortly afterward in 1933 or 1934. Syama Prasad refused to remarry after her death. He had two sons, Anutosh and Debatosh, and two daughters, Sabita and Arati. His grandniece Kamala Sinha

Kamala (Kamla) Sinha (30 September 1932 – 31 December 2014) was an Indian politician and diplomat. She was twice elected to the Rajya Sabha from 1990 to 2000, and later served as Ambassador to Suriname and Barbados. She was also Union Council ...

served as the Minister of State for External Affairs in the I. K. Gujral ministry.

Syama Prasad was also affiliated with the Buddhist Mahabodhi Society

The Maha Bodhi Society is a South Asian Buddhism, Buddhist society presently based in Kolkata, India. Founded by the Sri Lankan Buddhist leader Anagarika Dharmapala and the British journalist and poet Sir Edwin Arnold, its first office was in Bodh ...

. In 1942, he succeeded M.N. Mukherjee to become the president of the organisation. The relics of Gautam Buddha's two disciples Sariputra and Maudgalyayana

Maudgalyāyana (), also known as Mahāmaudgalyāyana or by his birth name Kolita, was one of Gautama Buddha, the Buddha's closest disciples. Described as a contemporary of disciples such as Subhuti, Śāriputra ('), and Mahākāśyapa (), he i ...

, discovered in the Great Stupa at Sanchi

Sanchi Stupa is a Buddhist art, Buddhist complex, famous for its Great Stupa, on a hilltop at Sanchi Town in Raisen District of the States and territories of India, State of Madhya Pradesh, India. It is located, about 23 kilometers from Raisen ...

by Sir Alexander Cunningham

Major General Sir Alexander Cunningham (23 January 1814 – 28 November 1893) was a British Army engineer with the Bengal Sappers who later took an interest in the history and archaeology of India. In 1861, he was appointed to the newly crea ...

in 1851 and kept at the British Museum

The British Museum is a Museum, public museum dedicated to human history, art and culture located in the Bloomsbury area of London. Its permanent collection of eight million works is the largest in the world. It documents the story of human cu ...

, were brought back to India by HMIS Tir. A ceremony attended by politicians and leaders of many foreign countries was held on the next day at Calcutta Maidan. They were handed over by Nehru to Mukherjee, who later took these relics to Cambodia

Cambodia, officially the Kingdom of Cambodia, is a country in Southeast Asia on the Mainland Southeast Asia, Indochinese Peninsula. It is bordered by Thailand to the northwest, Laos to the north, and Vietnam to the east, and has a coastline ...

, Burma

Myanmar, officially the Republic of the Union of Myanmar; and also referred to as Burma (the official English name until 1989), is a country in northwest Southeast Asia. It is the largest country by area in Mainland Southeast Asia and ha ...

, Thailand

Thailand, officially the Kingdom of Thailand and historically known as Siam (the official name until 1939), is a country in Southeast Asia on the Mainland Southeast Asia, Indochinese Peninsula. With a population of almost 66 million, it spa ...

and Vietnam

Vietnam, officially the Socialist Republic of Vietnam (SRV), is a country at the eastern edge of mainland Southeast Asia, with an area of about and a population of over 100 million, making it the world's List of countries and depende ...

. Upon his return to India, he placed the relics inside the Sanchi Stupa in November 1952.

Death

Mukherjee was arrested upon entering Kashmir on 11 May 1953. He and two of his arrested companions were first taken to Central Jail of

Mukherjee was arrested upon entering Kashmir on 11 May 1953. He and two of his arrested companions were first taken to Central Jail of Srinagar

Srinagar (; ) is a city in Indian-administered Jammu and Kashmir in the disputed Kashmir region.The application of the term "administered" to the various regions of Kashmir and a mention of the Kashmir dispute is supported by the tertiary ...

. Later they were transferred to a cottage

A cottage, during Feudalism in England, England's feudal period, was the holding by a cottager (known as a cotter or ''bordar'') of a small house with enough garden to feed a family and in return for the cottage, the cottager had to provide ...

outside the city. Mukherjee's condition started deteriorating and he started feeling pain in the back and high temperature on the night between 19 and 20 June. He was diagnosed with dry pleurisy

Pleurisy, also known as pleuritis, is inflammation of the membranes that surround the lungs and line the chest cavity (Pulmonary pleurae, pleurae). This can result in a sharp chest pain while breathing. Occasionally the pain may be a constant d ...

from which he had also suffered in 1937 and 1944. The doctor prescribed him a streptomycin

Streptomycin is an antibiotic medication used to treat a number of bacterial infections, including tuberculosis, Mycobacterium avium complex, ''Mycobacterium avium'' complex, endocarditis, brucellosis, Burkholderia infection, ''Burkholderia'' i ...

injection and powders, however, Mukherjee informed him that his family physician had told him that streptomycin did not suit his system. The doctor, however, told him that new information about the drug had come to light and assured him that he would be fine. On 22 June, he felt pain in the heart region, started perspiring and started feeling like he was fainting. He was later shifted to a hospital and provisionally diagnosed with a heart attack

A myocardial infarction (MI), commonly known as a heart attack, occurs when Ischemia, blood flow decreases or stops in one of the coronary arteries of the heart, causing infarction (tissue death) to the heart muscle. The most common symptom ...

. He died a day later. The state government declared that he had died on 23 June at 3:40 a.m. due to a heart attack.

His death in custody raised wide suspicion across the country and demands for an independent inquiry were raised, including earnest requests from his mother, Jogamaya Devi, to Nehru. The prime minister declared that he had asked several persons who were privy to the facts and, according to him, there was no mystery behind Mukherjee's death. Devi did not accept Nehru's reply and requested an impartial inquiry. Nehru, however, ignored the letter and no inquiry commission was set up.

Atal Bihari Vajpayee

Atal Bihari Vajpayee (25 December 1924 – 16 August 2018) was an Indian poet, writer and statesman who served as the prime minister of India, first for a term of 13 days in 1996, then for a period of 13 months from 1998 ...

claimed in 2004 that the arrest of Mukherjee in Jammu and Kashmir was a "Nehru conspiracy" and that the death of Mukherjee has remained "even now a mystery". The BJP in 2011 called for an inquiry to probe Mukherjee's death.

Legacy

One of the main thoroughfares inCalcutta

Kolkata, also known as Calcutta (List of renamed places in India#West Bengal, its official name until 2001), is the capital and largest city of the Indian States and union territories of India, state of West Bengal. It lies on the eastern ba ...

was renamed Syama Prasad Mukherjee Road on 3 July 1953 a few days after his death. Syamaprasad College founded by him in 1945 in Kolkata

Kolkata, also known as Calcutta ( its official name until 2001), is the capital and largest city of the Indian state of West Bengal. It lies on the eastern bank of the Hooghly River, west of the border with Bangladesh. It is the primary ...

is named after him. Shyama Prasad Mukherji College of University of Delhi

The Delhi University (DU, ISO 15919, ISO: ), also and officially known as the University of Delhi, is a collegiate university, collegiate research university, research Central university (India), central university located in Delhi, India. It ...

was established in 1969 in his memory. On 7 August 1998, the Ahmedabad Municipal Corporation named a bridge after Mukherjee. Delhi

Delhi, officially the National Capital Territory (NCT) of Delhi, is a city and a union territory of India containing New Delhi, the capital of India. Straddling the Yamuna river, but spread chiefly to the west, or beyond its Bank (geography ...

has a major road named after Mukherjee called Shyama Prasad Mukherjee Marg. Kolkata, too, has a major road called Shyama Prasad Mukherjee Road. In 2001, the main research funding institute of the Government of India, CSIR, instituted a new fellowship named after him.

On 22 April 2010, the

On 22 April 2010, the Municipal Corporation of Delhi

Municipal Corporation of Delhi (MCD; ISO: ''Dillī Nagara Nigama'') is the municipal corporation that governs most of Delhi, India. The MCD is among the largest municipal bodies in the world providing civic services to a population of about 20 ...

's (MCD) newly constructed Rs. 650-crore building, the tallest building in Delhi, was named the Doctor Syama Prasad Mukherjee Civic Centre. It was inaugurated by Home Minister

An interior minister (sometimes called a minister of internal affairs or minister of home affairs) is a cabinet official position that is responsible for internal affairs, such as public security, civil registration and identification, emergenc ...

P. Chidambaram. The building, which is estimated to cater to 20,000 visitors per day, will also house different wings and offices of the MCD. The MCD also built the Syama Prasad Swimming Pool Complex which hosted aquatic events during the 2010 Commonwealth Games

The 2010 Commonwealth Games, officially known as the XIX Commonwealth Games and commonly known as Delhi 2010, were an international multi-sport event for the members of the Commonwealth that was held in Delhi, India, from 3 to 14 October 201 ...

held in New Delhi.

In 2012, a flyover at Mathikere in

In 2012, a flyover at Mathikere in Bangalore

Bengaluru, also known as Bangalore (List of renamed places in India#Karnataka, its official name until 1 November 2014), is the Capital city, capital and largest city of the southern States and union territories of India, Indian state of Kar ...

City Limits was inaugurated and named the Dr Syama Prasad Mukherjee Flyover. The International Institute of Information Technology, Naya Raipur

International Institute of Information Technology, Naya Raipur (IIIT-NR), officially Dr. Shyama Prasad Mukherjee International Institute of Information Technology, Naya Raipur, is a state funded institute in Naya Raipur, Chhattisgarh, India. Th ...

is named after him.

In 2014, a multipurpose indoor stadium built on the Goa University

Goa University is a public state university headquartered in the city of Panaji, in the Indian state of Goa.

The traditions of Goa University date back to the 17th century,Prôa, Miguel Pires. "Escolas Superiores" Portuguesas Antes de 1950 ...

campus in Goa

Goa (; ; ) is a state on the southwestern coast of India within the Konkan region, geographically separated from the Deccan highlands by the Western Ghats. It is bound by the Indian states of Maharashtra to the north, and Karnataka to the ...

was named after Mukherjee.

The government of India approved the Shyama Prasad Mukherji Rurban Mission (SPMRM) with an outlay of on 16 September 2015. The Mission was launched by the Prime Minister on 21 February 2016 at Kurubhata, Murmunda Rurban Cluster, Rajnandgaon

Rajnandgaon is a city in Rajnandgaon District, in the state of Chhattisgarh, India. the population of the city was 163,122. Rajnandgaon district came into existence on 26January 1973, as a result of the division of Durg district.

History

Or ...

, Chhattisgarh

Chhattisgarh (; ) is a landlocked States and union territories of India, state in Central India. It is the List of states and union territories of India by area, ninth largest state by area, and with a population of roughly 30 million, the List ...

. In April 2017, Ranchi College was upgraded to Shyama Prasad Mukherjee University. In September 2017, Kolar, a town in Bhopal

Bhopal (; ISO 15919, ISO: Bhōpāl, ) is the capital (political), capital city of the Indian state of Madhya Pradesh and the administrative headquarters of both Bhopal district and Bhopal division. It is known as the ''City of Lakes,'' due to ...

, Madhya Pradesh

Madhya Pradesh (; ; ) is a state in central India. Its capital is Bhopal and the largest city is Indore, Indore. Other major cities includes Gwalior, Jabalpur, and Sagar, Madhya Pradesh, Sagar. Madhya Pradesh is the List of states and union te ...

, was renamed Shyama Prasad Mukherji Nagar by the state's Chief Minister Shivraj Singh Chauhan.

Gajendra Chauhan played the role of Mukherjee in the movie ''1946 Calcutta Killings''.

On 12 January 2020, the Kolkata Port Trust

The Syama Prasad Mookerjee Port (SPMP or SMP, Kolkata), formerly the Kolkata Port, is the only riverine major port in India, in the city of Kolkata, West Bengal, around from the sea. It is the oldest operating port in India and was construc ...

was renamed Syama Prasad Mukherjee Port by Prime Minister Narendra Modi

Narendra Damodardas Modi (born 17 September 1950) is an Indian politician who has served as the Prime Minister of India, prime minister of India since 2014. Modi was the chief minister of Gujarat from 2001 to 2014 and is the Member of Par ...

.

The Chenani-Nashri Tunnel on NH44 in Jammu and Kashmir was renamed after Mukherjee by the Indian government in 2020.

See also

*List of unsolved deaths

This list of unsolved deaths includes notable cases where:

* The cause of death could not be officially determined following an investigation

* The person's identity could not be established after they were found dead

* The cause is known, but th ...

Notes

References

Citations

Sources

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *Further reading

* *External links

Excerpts from convocation address at Benares Hindu University (1 December 1940)

{{DEFAULTSORT:Mukherjee, Syama Prasad 1901 births 1953 deaths India MPs 1952–1957 20th-century Indian lawyers Bengali Hindus Bengali lawyers Bengali activists Alumni of the Inns of Court School of Law Presidency University, Kolkata alumni First Nehru ministry Hindu martyrs Indian political party founders Indian barristers Indian activists Politicians from Kolkata Vice-chancellors of the University of Calcutta Indian National Congress politicians from West Bengal Hindu Mahasabha politicians Bharatiya Jana Sangh politicians Members of the Constituent Assembly of India Lok Sabha members from West Bengal Indian people who died in prison custody Presidents of The Asiatic Society Scholars from Kolkata University of Calcutta alumni Commerce and industry ministers of India Founders of Indian schools and colleges Bengal MLAs 1937–1945 Bengal MLAs 1946–1947 West Bengal MLAs 1947–1951