Swiss Reformation on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Protestant Reformation in Switzerland was promoted initially by

The Protestant Reformation in Switzerland was promoted initially by

The main proponent of the Reformation in Switzerland was

The main proponent of the Reformation in Switzerland was  Over the next few years, the cities of St. Gallen,

Over the next few years, the cities of St. Gallen,

After Zwingli's death,

After Zwingli's death,

The success of the

The success of the  Two years later, the

Two years later, the

While the official Church remained passive during the beginnings of the Reformation, the Swiss Catholic cantons took measures early on to keep the new movement at bay. They assumed judicial and financial powers over the clergy, laid down firm rules of conduct for the priests, outlawed

While the official Church remained passive during the beginnings of the Reformation, the Swiss Catholic cantons took measures early on to keep the new movement at bay. They assumed judicial and financial powers over the clergy, laid down firm rules of conduct for the priests, outlawed  The Catholic cantons also maintained their domination of the Catholic Church after the

The Catholic cantons also maintained their domination of the Catholic Church after the

Mercenaries of the Swiss cantons participated in the

Mercenaries of the Swiss cantons participated in the

During the

During the

Historians count 13 (

Historians count 13 (

Renaissance and Reformation

'.

Reformation in Switzerland

by Markus Jud. In English, also available in French and German.

by "Presence Switzerland", an official body of the Swiss Confederation. (In English, available also i

) *

in Geneva in 1602.

(English transcription).

in German. {{DEFAULTSORT:Reformation in Switzerland 16th-century establishments in the Old Swiss Confederacy History of Switzerland by period

The Protestant Reformation in Switzerland was promoted initially by

The Protestant Reformation in Switzerland was promoted initially by Huldrych Zwingli

Huldrych or Ulrich Zwingli (1 January 1484 – 11 October 1531) was a Swiss Christian theologian, musician, and leader of the Reformation in Switzerland. Born during a time of emerging Swiss patriotism and increasing criticism of the Swis ...

, who gained the support of the magistrate, Mark Reust, and the population of Zürich

Zurich (; ) is the list of cities in Switzerland, largest city in Switzerland and the capital of the canton of Zurich. It is in north-central Switzerland, at the northwestern tip of Lake Zurich. , the municipality had 448,664 inhabitants. The ...

in the 1520s. It led to significant changes in civil life and state matters in Zürich and spread to several other cantons

A canton is a type of administrative division of a country. In general, cantons are relatively small in terms of area and population when compared with other administrative divisions such as counties, departments, or provinces. Internationally, th ...

of the Old Swiss Confederacy

The Old Swiss Confederacy, also known as Switzerland or the Swiss Confederacy, was a loose confederation of independent small states (, German or ), initially within the Holy Roman Empire. It is the precursor of the modern state of Switzerlan ...

. Seven cantons remained Catholic

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

, however, which led to intercantonal wars known as the Wars of Kappel. After the victory of the Catholic cantons in 1531, they proceeded to institute Counter-Reformation

The Counter-Reformation (), also sometimes called the Catholic Revival, was the period of Catholic resurgence that was initiated in response to, and as an alternative to or from similar insights as, the Protestant Reformations at the time. It w ...

policies in some regions. The schism and distrust between the Catholic and the Protestant

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that emphasizes Justification (theology), justification of sinners Sola fide, through faith alone, the teaching that Salvation in Christianity, salvation comes by unmerited Grace in Christianity, divin ...

cantons defined their interior politics and paralysed any common foreign policy

Foreign policy, also known as external policy, is the set of strategies and actions a State (polity), state employs in its interactions with other states, unions, and international entities. It encompasses a wide range of objectives, includ ...

until well into the 18th century.

Despite their religious differences and an exclusively Catholic defence alliance of the seven cantons (''Goldener Bund''), no other major armed conflicts directly between the cantons occurred. Soldiers from both sides fought in the French Wars of Religion

The French Wars of Religion were a series of civil wars between French Catholic Church, Catholics and Protestantism, Protestants (called Huguenots) from 1562 to 1598. Between two and four million people died from violence, famine or disease di ...

.

During the Thirty Years' War

The Thirty Years' War, fought primarily in Central Europe between 1618 and 1648, was one of the most destructive conflicts in History of Europe, European history. An estimated 4.5 to 8 million soldiers and civilians died from battle, famine ...

, the thirteen cantons

The early modern period, early modern history of the Old Swiss Confederacy (''Eidgenossenschaft'', also known as the "Swiss Republic" or ''Republica Helvetiorum'') and its constituent Thirteen Cantons encompasses the time of the Thirty Years' W ...

managed to maintain their neutrality, partly because all major powers in Europe depended on Swiss mercenaries

The Swiss mercenaries were a powerful infantry force constituting professional soldiers originating from the cantons of the Old Swiss Confederacy. They were notable for their service in foreign armies, especially among the military forces of th ...

and would not let Switzerland fall into the hands of one of their rivals. The Three Leagues (''Drei Bünde'') of the Grisons

The Grisons (; ) or Graubünden (),Names include:

* ;

*Romansh language, Romansh:

**

**

**

**

**

**;

* ;

* ;

* .

See also list of European regions with alternative names#G, other names. more formally the Canton of the Grisons or the Canton ...

were not yet a member of the Confederacy but were involved in the war from 1620 onward, which led to their loss of the Valtellina

Valtellina or the Valtelline (occasionally spelled as two words in English: Val Telline; (); or ; ; ) is a valley in the Lombardy region of northern Italy, bordering Switzerland. Today it is known for its ski centre, hot spring spas, bresa ...

from 1623 to 1639.

Development of Protestantism

After the violent conflicts of the late 15th century, the Swiss cantons had had a generation of relative political stability. As part of their struggle for independence, they had already in the 15th century sought to limit the influence of the Church on their political sovereignty. Manymonasteries

A monastery is a building or complex of buildings comprising the domestic quarters and workplaces of monastics, monks or nuns, whether living in communities or alone ( hermits). A monastery generally includes a place reserved for prayer which m ...

had already come under secular supervision, and the administration of schools was in the hands of the cantons, although the teachers generally still were priests.

Nevertheless, many of the problems of the Church also existed in the Swiss Confederacy. Many a cleric, as well as the Church as a whole, enjoyed a luxurious lifestyle in stark contrast to the conditions of the large majority of the population; this luxury was financed by high church taxes and abundant sale of indulgence

In the teaching of the Catholic Church, an indulgence (, from , 'permit') is "a way to reduce the amount of punishment one has to undergo for (forgiven) sins". The ''Catechism of the Catholic Church'' describes an indulgence as "a remission bef ...

s. Many priests were poorly educated, and spiritual Church doctrines were often disregarded. Many priests did not live in celibacy but in concubinage

Concubinage is an interpersonal relationship, interpersonal and Intimate relationship, sexual relationship between two people in which the couple does not want to, or cannot, enter into a full marriage. Concubinage and marriage are often regarde ...

. The new reformatory ideas thus fell on fertile ground.

The main proponent of the Reformation in Switzerland was

The main proponent of the Reformation in Switzerland was Huldrych Zwingli

Huldrych or Ulrich Zwingli (1 January 1484 – 11 October 1531) was a Swiss Christian theologian, musician, and leader of the Reformation in Switzerland. Born during a time of emerging Swiss patriotism and increasing criticism of the Swis ...

, whose actions during the Affair of the Sausages

The Affair of the Sausages (1522) was the event that sparked the Reformation in Zürich. Huldrych Zwingli, pastor of Grossmünster in Zurich, Switzerland, spearheaded the event by publicly speaking in favor of eating sausage during the Lenten fast ...

are now considered to be the start of the Reformation in Switzerland. His own studies, in the renaissance humanist tradition, had led him to preach against injustices and hierarchies in the Church already in 1516 while he was still a priest in Einsiedeln

Einsiedeln () is a municipalities of Switzerland, municipality and Districts of Switzerland#Schwyz, district in the canton of Schwyz in Switzerland known for its monastery, the Benedictine Einsiedeln Abbey, established in the 10th century.

Histor ...

. When he was called to Zürich

Zurich (; ) is the list of cities in Switzerland, largest city in Switzerland and the capital of the canton of Zurich. It is in north-central Switzerland, at the northwestern tip of Lake Zurich. , the municipality had 448,664 inhabitants. The ...

, he expanded his criticism also onto political topics and in particular condemned the mercenary

A mercenary is a private individual who joins an armed conflict for personal profit, is otherwise an outsider to the conflict, and is not a member of any other official military. Mercenaries fight for money or other forms of payment rather t ...

business. His ideas were received favorably, especially by entrepreneurs, businessmen, and the guild

A guild ( ) is an association of artisans and merchants who oversee the practice of their craft/trade in a particular territory. The earliest types of guild formed as organizations of tradespeople belonging to a professional association. They so ...

s. The first disputation of Zürich of 1523 was the breakthrough: the city council decided to implement his reformatory plans and to convert to Protestantism.

In the following two years, profound changes took place in Zürich. The Church was thoroughly secularised. Priests were relieved from celibacy and the opulent decorations in the churches were thrown out. The state assumed the administration of Church properties, financing the social works (which up to then were managed entirely by the Church), and also paid the priests. The last abbess of the Fraumünster

The Fraumünster (; lit. in ) is a church in Zürich which was built on the remains of a former abbey for aristocratic women which was founded in 853 by Louis the German for his daughter Hildegard. He endowed the Benedictine convent with the l ...

, Katharina von Zimmern

Katharina von Zimmern (1478 – 17 August 1547), also known as the imperial abbess of Zürich and Katharina von Reischach, was the last abbess of the Fraumünster Abbey in Zürich.

Early life

Katharina von Zimmern was born in 1478 in Mes ...

, turned over the convent including all of its rights and possessions to the city authorities on 30 November 1524. She even married the next year.

Over the next few years, the cities of St. Gallen,

Over the next few years, the cities of St. Gallen, Schaffhausen

Schaffhausen (; ; ; ; ), historically known in English as Shaffhouse, is a list of towns in Switzerland, town with historic roots, a municipalities of Switzerland, municipality in northern Switzerland, and the capital of the canton of Schaffh ...

, Basel

Basel ( ; ), also known as Basle ( ), ; ; ; . is a city in northwestern Switzerland on the river Rhine (at the transition from the High Rhine, High to the Upper Rhine). Basel is Switzerland's List of cities in Switzerland, third-most-populo ...

, Bienne

Biel/Bienne (official bilingual wording; German: ''Biel'' ; French: ''Bienne'' ; locally ; ; ; ) is a bilingual city in the canton of Bern in Switzerland. With over 55,000 residents, it is the country's tenth-largest city by population. Th ...

, Mulhouse, and Bern

Bern (), or Berne (), ; ; ; . is the ''de facto'' Capital city, capital of Switzerland, referred to as the "federal city".; ; ; . According to the Swiss constitution, the Swiss Confederation intentionally has no "capital", but Bern has gov ...

all followed the example set by Zürich. Bern was the first to follow Zürich, in 1528, when the aftermath of the Bern Disputation

The Bern Disputation was a debate over the theology of the Swiss Reformation that occurred in Bern from 6 to 26 January 1528 that ended in Bern becoming the second Swiss canton to officially become Protestant.

Background

As the reformation in ...

officially pronounced Bern as the second Protestant Swiss canton. Their subject territories were converted to Protestantism by decree. In Basel, reformer Johannes Oecolampadius

Johannes Oecolampadius (also ''Œcolampadius'', in German also Oekolampadius, Oekolampad; 1482 – 24 November 1531) was a German Protestant reformer in the Calvinist tradition from the Electoral Palatinate. He was the leader of the Protestant ...

was active, in St. Gallen, the Reformation was adopted by the mayor Joachim Vadian. In Glarus

Glarus (; ; ; ; ) is the capital of the canton of Glarus in Switzerland. Since 1 January 2011, the municipality of Glarus incorporates the former municipalities of Ennenda, Netstal and Riedern.Appenzell

Appenzell () was a cantons of Switzerland, canton in the northeast of Switzerland, and entirely surrounded by the canton of St. Gallen, in existence from 1403 to 1597.

Appenzell became independent of the Abbey of Saint Gall in 1403 and entered ...

, and in the Grisons

The Grisons (; ) or Graubünden (),Names include:

* ;

*Romansh language, Romansh:

**

**

**

**

**

**;

* ;

* ;

* .

See also list of European regions with alternative names#G, other names. more formally the Canton of the Grisons or the Canton ...

, which all three had a more republican structure, individual communes decided for or against the Reformation. In the French-speaking parts, reformers like William Farel had been preaching the new faith under Bernese protection since the 1520s, but only in 1536, just before John Calvin

John Calvin (; ; ; 10 July 150927 May 1564) was a French Christian theology, theologian, pastor and Protestant Reformers, reformer in Geneva during the Protestant Reformation. He was a principal figure in the development of the system of C ...

arrived there, did the city of Geneva

Geneva ( , ; ) ; ; . is the List of cities in Switzerland, second-most populous city in Switzerland and the most populous in French-speaking Romandy. Situated in the southwest of the country, where the Rhône exits Lake Geneva, it is the ca ...

convert to Protestantism. The same year, Bern conquered the hitherto Savoyard Vaud

Vaud ( ; , ), more formally Canton of Vaud, is one of the Cantons of Switzerland, 26 cantons forming the Switzerland, Swiss Confederation. It is composed of Subdivisions of the canton of Vaud, ten districts; its capital city is Lausanne. Its coat ...

and also instituted Protestantism there.

Despite their conversion to Protestantism, the citizens of Geneva were not ready to adopt Calvin's new strict Church order and banned him and Farel from the city in 1538. Three years later, following the election of a new city council, Calvin was called back. Step by step he implemented his strict program. A counter-revolt in 1555 failed, and many established families left the city.

In search of a common theology

Zwingli, who had studied in Basel at the same time asErasmus

Desiderius Erasmus Roterodamus ( ; ; 28 October c. 1466 – 12 July 1536), commonly known in English as Erasmus of Rotterdam or simply Erasmus, was a Dutch Christian humanist, Catholic priest and Catholic theology, theologian, educationalist ...

, had arrived at a more radical renewal than Luther and his ideas differed from the latter in several points. A reconciliation attempt at the Marburg Colloquy

The Marburg Colloquy was a meeting at Marburg Castle, Marburg, Hesse, Germany, which attempted to solve a disputation between Martin Luther and Ulrich Zwingli over the Real Presence of Christ in the Eucharist. It took place between 1 October and ...

in 1529 failed. Although the two charismatic leaders found a consensus on fourteen points, they kept differing on the last one on the Eucharist

The Eucharist ( ; from , ), also called Holy Communion, the Blessed Sacrament or the Lord's Supper, is a Christianity, Christian Rite (Christianity), rite, considered a sacrament in most churches and an Ordinance (Christianity), ordinance in ...

: Luther maintained that through sacramental union

Sacramental union (Latin: ''unio sacramentalis''; Martin Luther's German: ''Sacramentliche Einigkeit'';''Weimar Ausgabe'' 26, 442.23; ''Luther's Works'' 37, 299-300. German: ''sakramentalische Vereinigung'') is the Lutheran theological doctrine o ...

the bread and wine in the Lord's Supper became truly the flesh and blood of Christ, whereas Zwingli considered the bread and wine only symbols. This schism

A schism ( , , or, less commonly, ) is a division between people, usually belonging to an organization, movement, or religious denomination. The word is most frequently applied to a split in what had previously been a single religious body, suc ...

and the defeat of Zürich in the Second War of Kappel

The Second War of Kappel () was an armed conflict in 1531 between the Catholic and the Protestant cantons of the Old Swiss Confederacy during the Reformation in Switzerland.

Background

The peace concluded after the First War of Kappel two yea ...

in 1531, where Zwingli was killed on the battlefield, were a serious setback, for Zwinglianism.

After Zwingli's death,

After Zwingli's death, Heinrich Bullinger

Heinrich Bullinger (18 July 1504 – 17 September 1575) was a Swiss Reformer and theologian, the successor of Huldrych Zwingli as head of the Church of Zürich and a pastor at the Grossmünster. One of the most important leaders of the Swiss Re ...

took over his post in Zürich. Reformers in Switzerland continued for the next decades to reform the Church and to improve its acceptance by the common people. Bullinger in particular also tried bridging the differences between Zwinglianism and Calvinism

Reformed Christianity, also called Calvinism, is a major branch of Protestantism that began during the 16th-century Protestant Reformation. In the modern day, it is largely represented by the Continental Reformed Christian, Presbyteri ...

. He was instrumental in establishing the ''Consensus Tigurinus'' of 1549 with John Calvin and the '' Confessio Helvetica posterior'' of 1566, which finally included all Protestant cantons and associates of the confederacy. The ''Confessio'' was also accepted in other European Protestant regions in Bohemia

Bohemia ( ; ; ) is the westernmost and largest historical region of the Czech Republic. In a narrow, geographic sense, it roughly encompasses the territories of present-day Czechia that fall within the Elbe River's drainage basin, but historic ...

, Hungary, Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It extends from the Baltic Sea in the north to the Sudetes and Carpathian Mountains in the south, bordered by Lithuania and Russia to the northeast, Belarus and Ukrai ...

, the Netherlands

, Terminology of the Low Countries, informally Holland, is a country in Northwestern Europe, with Caribbean Netherlands, overseas territories in the Caribbean. It is the largest of the four constituent countries of the Kingdom of the Nether ...

, and Scotland

Scotland is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It contains nearly one-third of the United Kingdom's land area, consisting of the northern part of the island of Great Britain and more than 790 adjac ...

, and together with the Heidelberg Catechism

The Heidelberg Catechism (1563), one of the Three Forms of Unity, is a Reformed catechism taking the form of a series of questions and answers, for use in teaching Reformed Christian doctrine. It was published in 1563 in Heidelberg, Germany. Its ...

of 1563, where Bullinger also played an important role, and the Canons of Dordrecht

The Canons of Dort, or Canons of Dordrecht, formally titled ''The Decision of the Synod of Dort on the Five Main Points of Doctrine in Dispute in the Netherlands'', is an exposition of orthodox Reformed soteriology against Arminianism, by the Na ...

of 1619 it would become the theological foundation of Protestantism of the Calvinist strain.

The ''Consensus Tigurinus

The ''Consensus Tigurinus'' or Consensus of Zurich was a Protestant document written in 1549 by John Calvin and Heinrich Bullinger.

The document was intended to bring unity to the Protestant churches on their doctrines of the sacraments, parti ...

'' (Zurich Consensus) formalized the Calvinist-Bullingerian doctrine of the pneumatic presence taught in the Reformed Churches, which asserts that when communicants receive the bread and wine, they also receive the body of Christ and the blood of Christ by faith. It declared that the eucharist was not just symbolic of the meal, but they also rejected the Lutheran position that the body and blood of Christ is in union with the elements., J. C. McLelland, "Meta-Zwingli or Anti-Zwingli? Bullinger and Calvin in Eucharistic Concord" It was this Calvinist-Bullingerian doctrine of a real spiritual presence of Christ in the Eucharist that became the doctrine of the Reformed Churches, while Zwingli's view was rejected by the Reformed Churches (though it was later adopted by other traditions, such as the Plymouth Brethren

The Plymouth Brethren or Assemblies of Brethren are a low church and Nonconformist (Protestantism), Nonconformist Christian movement whose history can be traced back to Dublin, Ireland, in the mid to late 1820s, where it originated from Anglica ...

). With this rapprochement, Calvin established his role in the Swiss Reformed Church

The Protestant Church in Switzerland (PCS), formerly named Federation of Swiss Protestant Churches until 31 December 2019, is a federation of 25 member churches – 24 cantonal churches and the Evangelical-Methodist Church of Switzerland. The P ...

es and eventually in the wider world.,J. C. McLelland, "Meta-Zwingli or Anti-Zwingli? Bullinger and Calvin in Eucharistic Concord" This is reflected in the Second Helvetic Confession

The Helvetic Confessions are two documents expressing the common belief of Reformed Christianity, Reformed churches, especially in Switzerland, whose primary author was the Swiss Reformed theologian Heinrich Bullinger. The First Helvetic Confessi ...

(1566), the confession of faith of the Protestant Church of Switzerland, which states: "The Supper is not a mere commemoration of Christ’s benefits…but rather a mystical and spiritual participation in the body and blood of the Lord."

Religious civil war

The success of the

The success of the Reformation in Zürich

The Reformation in Zürich was promoted initially by Huldrych Zwingli, who gained the support of the magistrates of the city of Zürich and the princess abbess Katharina von Zimmern of the Fraumünster Abbey, and the population of the city of Hist ...

and its rapid territorial expansion definitely made this religious renewal a political issue and a major source of conflict between the thirteen cantons. The alpine cantons of Uri

Uri may refer to:

Places

* Canton of Uri, a canton in Switzerland

* Úri, a village and commune in Hungary

* Uri, Iran, a village in East Azerbaijan Province

* Uri, Jammu and Kashmir, a town in India

* Uri (island), off Malakula Island in V ...

, Schwyz

Schwyz (; ; ) is a town and the capital of the canton of Schwyz in Switzerland.

The Federal Charter of 1291 or ''Bundesbrief'', the charter that eventually led to the foundation of Switzerland, can be seen at the ''Bundesbriefmuseum''.

The of ...

, Unterwalden

Unterwalden, translated from the Latin ''inter silvas'' ("between the forests"), is the old name of a forest-canton of the Old Swiss Confederacy in central Switzerland, south of Lake Lucerne, consisting of two valleys or '' Talschaften'', now tw ...

, Lucerne

Lucerne ( ) or Luzern ()Other languages: ; ; ; . is a city in central Switzerland, in the Languages of Switzerland, German-speaking portion of the country. Lucerne is the capital of the canton of Lucerne and part of the Lucerne (district), di ...

, and Zug

Zug (Standard German: , Alemannic German: ; ; ; ; )Named in the 16th century. is the largest List of cities in Switzerland, town and capital of the Swiss canton of Zug. Zug is renowned as a hub for some of the wealthiest individuals in the wor ...

remained staunchly Catholic. Their opposition was not uniquely a question of faith; economic reasons also played a role. Besides on agriculture, their economy depended to a large degree on the mercenary

A mercenary is a private individual who joins an armed conflict for personal profit, is otherwise an outsider to the conflict, and is not a member of any other official military. Mercenaries fight for money or other forms of payment rather t ...

services and the financial recompensations for the same. They could not afford to lose this source of income, which was a major target of reformatory criticism. In contrast, the cities' economies were more diversified, including strong crafts and guilds as well as a budding industrial sector. Fribourg

or is the capital of the Cantons of Switzerland, Swiss canton of Canton of Fribourg, Fribourg and district of Sarine (district), La Sarine. Located on both sides of the river Saane/Sarine, on the Swiss Plateau, it is a major economic, adminis ...

and Solothurn

Solothurn ( ; ; ; ; ) is a town, a municipality, and the capital of the canton of Solothurn in Switzerland. It is located in the north-west of Switzerland on the banks of the Aare and on the foot of the Weissenstein Jura mountains.

The town is ...

also remained Catholic.

The five alpine cantons perceived the Reformation as a threat early on; already in 1524 they formed the "League of the Five Cantons" (''Bund der fünf Orte'') to combat the spreading of the new faith. Both sides tried to strengthen their positions by concluding defensive alliances with third parties: the Protestant cantons formed a city alliance, including the Protestant cities of Konstanz

Konstanz ( , , , ), traditionally known as Constance in English, is a college town, university city with approximately 83,000 inhabitants located at the western end of Lake Constance in the Baden-Württemberg state of south Germany. The city ho ...

and Strasbourg

Strasbourg ( , ; ; ) is the Prefectures in France, prefecture and largest city of the Grand Est Regions of France, region of Geography of France, eastern France, in the historic region of Alsace. It is the prefecture of the Bas-Rhin Departmen ...

(''Christliches Burgrecht''), translated variously as Cristian Civic Union, Christian Co-burghery, Christian Confederation and Christian Federation (in Latin Zwingli called it Civitas Christiana or Christian State); the Catholic ones entered a pact with Ferdinand of Austria.

In the tense atmosphere, small incidents could easily escalate. Conflicts arose especially over the situation in the common territories, where the administration changed bi-annually among cantons and thus switched between Catholic and Protestant rules. Several mediation attempts failed such as the disputation of Baden

Baden (; ) is a historical territory in southern Germany. In earlier times it was considered to be on both sides of the Upper Rhine, but since the Napoleonic Wars, it has been considered only East of the Rhine.

History

The margraves of Ba ...

in 1526.

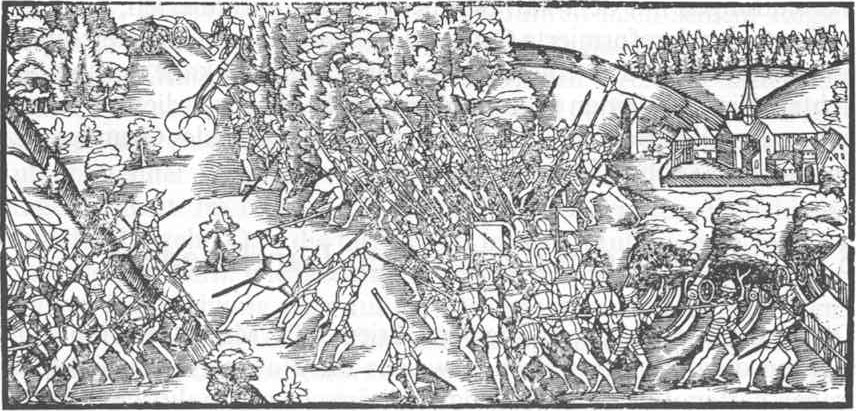

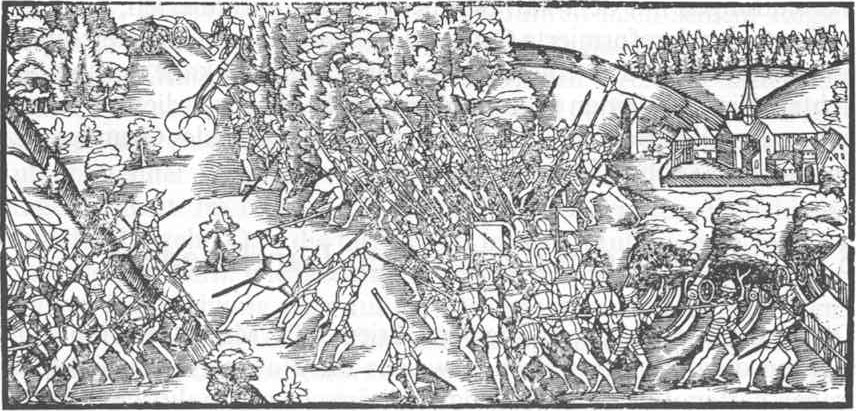

After numerous minor incidents and provocations from both sides, a Protestant pastor was burned on the stake in Schwyz in 1529, and in retaliation Zürich declared war. By mediation of the other cantons, open war (known as the First War of Kappel) was barely avoided, but the peace agreement (''Erster Landfriede'') was not exactly favourable for the Catholic party, who had to dissolve its alliance with the Austrian Habsburg

The House of Habsburg (; ), also known as the House of Austria, was one of the most powerful dynasties in the history of Europe and Western civilization. They were best known for their inbreeding and for ruling vast realms throughout Europe d ...

s. The tensions remained essentially unresolved.

Two years later, the

Two years later, the second war of Kappel

The Second War of Kappel () was an armed conflict in 1531 between the Catholic and the Protestant cantons of the Old Swiss Confederacy during the Reformation in Switzerland.

Background

The peace concluded after the First War of Kappel two yea ...

broke out. Zürich was taking the refusal of the Catholic cantons to help the Grisons

The Grisons (; ) or Graubünden (),Names include:

* ;

*Romansh language, Romansh:

**

**

**

**

**

**;

* ;

* ;

* .

See also list of European regions with alternative names#G, other names. more formally the Canton of the Grisons or the Canton ...

in the Musso war as a pretext, but on 11 October 1531, the Catholic cantons decisively defeated the forces of Zürich in the battle of Kappel am Albis

Kappel am Albis is a Municipalities of Switzerland, municipality in the district of Affoltern (district), Affoltern in the Cantons of Switzerland, canton of Zurich (canton), Zürich in Switzerland.

Its name of Kappel () is specified by "on the Al ...

. Zwingli was killed on the battlefield. The Protestant cantons had to agree to a peace treaty, the so-called ''Zweiter Kappeler Landfriede'', which forced the dissolution of the Protestant alliance (''Christliches Burgrecht''). It gave Catholicism the priority in the common territories, but allowed communes that had already converted to remain Protestant. Only strategically important places such as the Freiamt or those along the route from Schwyz to the Rhine valley at Sargans

Sargans is a Municipalities of Switzerland, municipality in the ''Wahlkreis'' (constituency) of Sarganserland (Wahlkreis), Sarganserland in the Cantons of Switzerland, canton of St. Gallen (canton), St. Gallen in Switzerland.

Sargans is known for ...

(and thus to the Alpine passes in the Grisons) were forcibly re-Catholicised. In their own territories, the cantons remained free to implement one or the other religion. The peace thus prescribed the ''Cuius regio, eius religio

() is a Latin phrase which literally means "whose realm, his religion" – meaning that the religion of the ruler was to dictate the religion of those ruled. This legal principle marked a major development in the collective (if not individual) ...

''-principle that would also be adopted in the peace of Augsburg

The Peace of Augsburg (), also called the Augsburg Settlement, was a treaty between Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor, and the Schmalkaldic League, signed on 25 September 1555 in the German city of Augsburg. It officially ended the religious struggl ...

in the Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire, also known as the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation after 1512, was a polity in Central and Western Europe, usually headed by the Holy Roman Emperor. It developed in the Early Middle Ages, and lasted for a millennium ...

in 1555. Politically, this gave the Catholic cantons a majority in the ''Tagsatzung

The Federal Diet of Switzerland (, ; ; ) was the legislative and executive council of the Old Swiss Confederacy and existed in various forms from the beginnings of Swiss independence until the formation of the Swiss federal state in 1848.

T ...

'', the federal diet of the confederacy.

When their Protestant city alliance was dissolved, Zürich and the southern German cities joined the Schmalkaldic League

The Schmalkaldic League (; ; or ) was a military alliance of Lutheranism, Lutheran Prince of the Holy Roman Empire, principalities and cities within the Holy Roman Empire during the mid-16th century. It received its name from the town of Schm ...

, but in the German religious wars of 1546/47, Zürich and the other Swiss Protestant cantons remained strictly neutral. With the victory of Charles V Charles V may refer to:

Kings and Emperors

* Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor (1500–1558)

* Charles V of Naples (1661–1700), better known as Charles II of Spain

* Charles V of France (1338–1380), called the Wise

Others

* Charles V, Duke ...

the previously close relations to the Swabia

Swabia ; , colloquially ''Schwabenland'' or ''Ländle''; archaic English also Suabia or Svebia is a cultural, historic and linguistic region in southwestern Germany.

The name is ultimately derived from the medieval Duchy of Swabia, one of ...

n Protestant cities in the Holy Roman Empire were severed: many cities, like Konstanz, were re-Catholicised and many were placed under a strictly aristocratic rule.

Counter-Reformation

While the official Church remained passive during the beginnings of the Reformation, the Swiss Catholic cantons took measures early on to keep the new movement at bay. They assumed judicial and financial powers over the clergy, laid down firm rules of conduct for the priests, outlawed

While the official Church remained passive during the beginnings of the Reformation, the Swiss Catholic cantons took measures early on to keep the new movement at bay. They assumed judicial and financial powers over the clergy, laid down firm rules of conduct for the priests, outlawed concubinage

Concubinage is an interpersonal relationship, interpersonal and Intimate relationship, sexual relationship between two people in which the couple does not want to, or cannot, enter into a full marriage. Concubinage and marriage are often regarde ...

, and reserved the right to nominate priests in the first place, who previously had been assigned by the bishopric

In church governance, a diocese or bishopric is the ecclesiastical district under the jurisdiction of a bishop.

History

In the later organization of the Roman Empire, the increasingly subdivided provinces were administratively associate ...

s. They also banned printing, distributing, and possessing Reformist tracts; and banned the study of Hebrew

Hebrew (; ''ʿÎbrit'') is a Northwest Semitic languages, Northwest Semitic language within the Afroasiatic languages, Afroasiatic language family. A regional dialect of the Canaanite languages, it was natively spoken by the Israelites and ...

and Greek

Greek may refer to:

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor of all kno ...

(to put an end to the independent study of biblical sources). Overall, these measures were successful: not only did they prevent the spreading of the Reformation into the Catholic cantons but also they made the Church dependent on the state and generally strengthened the power of the civil authorities.

The Catholic cantons also maintained their domination of the Catholic Church after the

The Catholic cantons also maintained their domination of the Catholic Church after the Council of Trent

The Council of Trent (), held between 1545 and 1563 in Trent (or Trento), now in northern Italy, was the 19th ecumenical council of the Catholic Church. Prompted by the Protestant Reformation at the time, it has been described as the "most ...

(1545 to 1563), although they had accepted its positions. They opposed Cardinal Borromeo's plans for the creation of a new bishopric in central Switzerland. However, they did participate in the education program of Trent. In 1574, the first Jesuit

The Society of Jesus (; abbreviation: S.J. or SJ), also known as the Jesuit Order or the Jesuits ( ; ), is a religious order (Catholic), religious order of clerics regular of pontifical right for men in the Catholic Church headquartered in Rom ...

school was founded in Lucerne

Lucerne ( ) or Luzern ()Other languages: ; ; ; . is a city in central Switzerland, in the Languages of Switzerland, German-speaking portion of the country. Lucerne is the capital of the canton of Lucerne and part of the Lucerne (district), di ...

. Others soon followed, and in 1579, a Catholic university for Swiss priests, the ''Collegio helvetico'', was founded in Milan

Milan ( , , ; ) is a city in northern Italy, regional capital of Lombardy, the largest city in Italy by urban area and the List of cities in Italy, second-most-populous city proper in Italy after Rome. The city proper has a population of nea ...

. In 1586, a nunciature was opened in Lucerne. The Capuchins were also called to help; a Capuchin cloister was founded in 1581 in Altdorf.

Parallel to these efforts to reform the Catholic Church, the Catholic cantons also proceeded to re-Catholicize regions that had converted to Protestantism. Besides reconversions in the common territories, the Catholic cantons in 1560 first tried to undo the Reformation in Glarus

Glarus (; ; ; ; ) is the capital of the canton of Glarus in Switzerland. Since 1 January 2011, the municipality of Glarus incorporates the former municipalities of Ennenda, Netstal and Riedern.Duchy of Savoy

The Duchy of Savoy (; ) was a territorial entity of the Savoyard state that existed from 1416 until 1847 and was a possession of the House of Savoy.

It was created when Sigismund, Holy Roman Emperor, raised the County of Savoy into a duchy f ...

, and had the support of Aegidius Tschudi

Aegidius Tschudi (Glarus, 5 February 1505Glarus, 28 February 1572) was a Swiss historian, statesman and soldier, an eminent member of the Tschudi family of Glarus, Switzerland. His best-known work is the '' Chronicon Helveticum'', a history of ...

, the ''Landammann

''Landammann'' (plural ''Landammänner''), is the German title used by the chief magistrate in certain Cantons of Switzerland and at times featured in the Head of state's style at the confederal level.

Old Swiss Confederacy

''Landammann'' or ''A ...

'' (chief magistrate) of Glarus. But due to lack of money, they could not intervene in Glarus by force. In 1564, they settled for a treaty which prescribed the separation of religions in Glarus. There were henceforth ''two'' legislative assemblies (''Landsgemeinde

The ''Landsgemeinde'' ("cantonal assembly"; , plural ''Landsgemeinden'') is a public, non-secret ballot voting system operating by majority rule. Still in use – in a few places – at the subnational political level in Switzerland, it was fo ...

'') in the canton, a Catholic and a Protestant one, and Glarus would send one Catholic and one Protestant representative each to the ''Tagsatzung''.

The Bishop of Basel

The Diocese of Basel (; ) is a Latin Church, Latin Catholic diocese in Switzerland.

Historically, the bishops of Basel were also secular rulers of the Prince-Bishopric of Basel (). Today the diocese of Basel includes the Swiss Cantons of Switze ...

, Jakob Christoph Blarer von Wartensee

Jakob Christoph Blarer von Wartensee (11 May 1542 – 18 April 1608) was a Bishop of Basel and a leader in the Counter-Reformation in the region around Basel, in Switzerland.

Early history

He was born at Rosenberg Castle, the son of William, Pr ...

, moved his seat to Porrentruy

Porrentruy (; ; ) is a Swiss municipality and seat of the district of the same name located in the canton of Jura.

Porrentruy is home to National League team, HC Ajoie.

History

The first trace of human presence in Porrentruy is a Mesolit ...

in the Jura mountains

The Jura Mountains ( ) are a sub-alpine mountain range a short distance north of the Western Alps and mainly demarcate a long part of the French–Swiss border. While the Jura range proper (" folded Jura", ) is located in France and Switzerla ...

in 1529, when Basel became Protestant. In 1581, the bishopric regained the Birs valley lying southwest of Basel. In Appenzell

Appenzell () was a cantons of Switzerland, canton in the northeast of Switzerland, and entirely surrounded by the canton of St. Gallen, in existence from 1403 to 1597.

Appenzell became independent of the Abbey of Saint Gall in 1403 and entered ...

, where both confessions coexisted more or less peacefully, the counter-reformatory activities beginning with the arrival of the Capuchin friars

The Order of Friars Minor Capuchin (; Post-nominal letters, postnominal abbr. OFMCap) is a religious order (Catholic), religious order of Franciscans, Franciscan friars within the Catholic Church, one of three "Religious institute#Nomenclature, F ...

resulted in a split of the canton in 1597 into the Catholic Appenzell Innerrhoden

Canton of Appenzell Innerrhoden ( ; ; ; ), in English sometimes Appenzell Inner-Rhodes, is one of the 26 cantons forming the Swiss Confederation. It is composed of five districts. The seat of the government and parliament is Appenzell. It is ...

and the Protestant Ausserrhoden, which both had one vote in the ''Tagsatzung''.

Developments in the west

The Dukes of Savoy had tried already for centuries to gain sovereignty over the city ofGeneva

Geneva ( , ; ) ; ; . is the List of cities in Switzerland, second-most populous city in Switzerland and the most populous in French-speaking Romandy. Situated in the southwest of the country, where the Rhône exits Lake Geneva, it is the ca ...

, surrounded by Savoyard territory, for the Vaud

Vaud ( ; , ), more formally Canton of Vaud, is one of the Cantons of Switzerland, 26 cantons forming the Switzerland, Swiss Confederation. It is composed of Subdivisions of the canton of Vaud, ten districts; its capital city is Lausanne. Its coat ...

in the north of Lake Geneva

Lake Geneva is a deep lake on the north side of the Alps, shared between Switzerland and France. It is one of the List of largest lakes of Europe, largest lakes in Western Europe and the largest on the course of the Rhône. Sixty percent () ...

belonged to the duchy. The Reformation prompted the conflicts to escalate once more. Geneva exiled its bishop, who was backed by Savoy, in 1533 to Annecy

Annecy ( , ; , also ) is the Prefectures in France, prefecture and List of communes in France with over 20,000 inhabitants, largest city of the Haute-Savoie Departments of France, department in the Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes Regions of France, regi ...

. Bern and the Valais

Valais ( , ; ), more formally, the Canton of Valais or Wallis, is one of the cantons of Switzerland, 26 cantons forming the Switzerland, Swiss Confederation. It is composed of thirteen districts and its capital and largest city is Sion, Switzer ...

took advantage of the duke's involvement in northern Italy

Italy, officially the Italian Republic, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe, Western Europe. It consists of Italian Peninsula, a peninsula that extends into the Mediterranean Sea, with the Alps on its northern land b ...

and his opposition to France. When Francesco II Sforza died in Milan

Milan ( , , ; ) is a city in northern Italy, regional capital of Lombardy, the largest city in Italy by urban area and the List of cities in Italy, second-most-populous city proper in Italy after Rome. The city proper has a population of nea ...

in 1534, the duke's troops were bound by the French engagement there, and Bern promptly conquered the Vaud and, together with the Valais, also territories south of Lake Geneva

Lake Geneva is a deep lake on the north side of the Alps, shared between Switzerland and France. It is one of the List of largest lakes of Europe, largest lakes in Western Europe and the largest on the course of the Rhône. Sixty percent () ...

in 1536.

The alliance of 1560 of the Catholic cantons with Savoy encouraged duke Emmanuel Philibert to raise claims on the territories his father Charles III

Charles III (Charles Philip Arthur George; born 14 November 1948) is King of the United Kingdom and the 14 other Commonwealth realms.

Charles was born at Buckingham Palace during the reign of his maternal grandfather, King George VI, and ...

had lost in 1536. After the treaty of Lausanne

Lausanne ( , ; ; ) is the capital and largest List of towns in Switzerland, city of the Swiss French-speaking Cantons of Switzerland, canton of Vaud, in Switzerland. It is a hilly city situated on the shores of Lake Geneva, about halfway bet ...

of 1564, Bern had to return the Chablais

The Chablais (; ; ) was a province of the Duchy of Savoy. Its capital was Thonon-les-Bains.

The Chablais was elevated to a duchy in 1311 by Henry VII, Holy Roman Emperor.

This region is currently divided into three territories, the '' Chablais s ...

south of Lake Geneva

Lake Geneva is a deep lake on the north side of the Alps, shared between Switzerland and France. It is one of the List of largest lakes of Europe, largest lakes in Western Europe and the largest on the course of the Rhône. Sixty percent () ...

and the Pays de Gex (between Geneva and Nyon

Nyon (; historically German language, German: or and Italian language, Italian: , ) is a Municipalities of Switzerland, municipality in Nyon District in the Cantons of Switzerland, canton of Vaud in Switzerland. It is located some 25 kilometer ...

) to Savoy in 1567, and the Valais returned the territories west of Saint Gingolph two years later in the treaty of Thonon

Thonon-les-Bains (; ), often simply referred to as Thonon, is a subprefecture of the Haute-Savoie department in the Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes region in Eastern France. In 2018, the commune had a population of 35,241. Thonon-les-Bains is part of a ...

. Geneva was thus a Protestant enclave

An enclave is a territory that is entirely surrounded by the territory of only one other state or entity. An enclave can be an independent territory or part of a larger one. Enclaves may also exist within territorial waters. ''Enclave'' is so ...

within the Catholic territories of Savoy again and as a result intensified its relations with the Swiss confederacy and Bern and Zürich in particular. Its plea for full acceptance into the confederation—the city was an associate state only—was rejected by the Catholic majority of cantons.

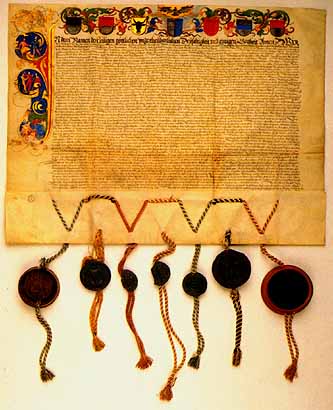

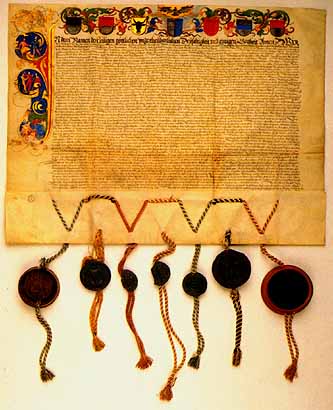

Mercenaries of the Swiss cantons participated in the

Mercenaries of the Swiss cantons participated in the French wars of religion

The French Wars of Religion were a series of civil wars between French Catholic Church, Catholics and Protestantism, Protestants (called Huguenots) from 1562 to 1598. Between two and four million people died from violence, famine or disease di ...

on all sides. Those from Protestant cantons fought on the sides of the Huguenots

The Huguenots ( , ; ) are a Religious denomination, religious group of French people, French Protestants who held to the Reformed (Calvinist) tradition of Protestantism. The term, which may be derived from the name of a Swiss political leader, ...

, supporting Henry of Navarre, while the Catholic troops fought for king Henry III of France

Henry III (; ; ; 19 September 1551 – 2 August 1589) was King of France from 1574 until his assassination in 1589, as well as King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania from 1573 to 1575.

As the fourth son of King Henry II of France, he ...

. In 1586, the seven Catholic cantons (the five alpine cantons, plus Fribourg and Solothurn) formed an exclusively Catholic alliance called the "Golden League" (''Goldener Bund'', named after the golden initials on the document) and sided with the Guises, who were also supported by Spain. In 1589, Henry III was assassinated and Henry of Navarre succeeded him as Henry IV of France

Henry IV (; 13 December 1553 – 14 May 1610), also known by the epithets Good King Henry (''le Bon Roi Henri'') or Henry the Great (''Henri le Grand''), was King of Navarre (as Henry III) from 1572 and King of France from 1589 to 16 ...

, and thus the Protestant mercenaries now fought for the king.

Since 1586, the duke of Savoy, Charles Emmanuel I, had placed Geneva under an embargo. With the new situation of 1589, the city now got support not only from Bern but also from the French king, and it went to war. The war between Geneva and Savoy continued even after the Peace of Vervins and the Edict of Nantes

The Edict of Nantes () was an edict signed in April 1598 by Henry IV of France, King Henry IV and granted the minority Calvinism, Calvinist Protestants of France, also known as Huguenots, substantial rights in the nation, which was predominantl ...

in 1598, which ended the wars in France proper. In the night from 11 to 12 December 1602, the duke's troops unsuccessfully tried to storm the city, which definitely maintained its independence from Savoy in the peace of Saint Julien, concluded in the following summer. The rebuttal of this attack, '' L'Escalade'', is still commemorated in Geneva today.

Also in 1586, a Catholic ''coup d'état'' in Mulhouse

Mulhouse (; ; Alsatian language, Alsatian: ''Mìlhüsa'' ; , meaning "Mill (grinding), mill house") is a France, French city of the European Collectivity of Alsace (Haut-Rhin department, in the Grand Est region of France). It is near the Fran ...

, an associate of the confederacy, prompted the military intervention of the Protestant cantons, which quickly restored the old Protestant order. Strasbourg

Strasbourg ( , ; ; ) is the Prefectures in France, prefecture and largest city of the Grand Est Regions of France, region of Geography of France, eastern France, in the historic region of Alsace. It is the prefecture of the Bas-Rhin Departmen ...

, another Protestant city, wanted to join the confederacy in 1588, but like Geneva some twenty years earlier, it was rejected by the Catholic cantons. In the Valais

Valais ( , ; ), more formally, the Canton of Valais or Wallis, is one of the cantons of Switzerland, 26 cantons forming the Switzerland, Swiss Confederation. It is composed of thirteen districts and its capital and largest city is Sion, Switzer ...

, the Reformation had had some success especially in the lower part of the Rhône

The Rhône ( , ; Occitan language, Occitan: ''Ròse''; Franco-Provençal, Arpitan: ''Rôno'') is a major river in France and Switzerland, rising in the Alps and flowing west and south through Lake Geneva and Southeastern France before dischargi ...

valley. However, in 1603 the Catholic cantons intervened, and with their support re-Catholicisation succeeded and the Protestant families had to emigrate.

Thirty Years' War

During the

During the Thirty Years' War

The Thirty Years' War, fought primarily in Central Europe between 1618 and 1648, was one of the most destructive conflicts in History of Europe, European history. An estimated 4.5 to 8 million soldiers and civilians died from battle, famine ...

, Switzerland was a relative "oasis of peace and prosperity" ( Grimmelshausen) in war-torn Europe. The cantons had concluded numerous mercenary

A mercenary is a private individual who joins an armed conflict for personal profit, is otherwise an outsider to the conflict, and is not a member of any other official military. Mercenaries fight for money or other forms of payment rather t ...

contracts and defence alliances with partners on all sides. Some of these contracts neutralized each other, which allowed the confederation to remain neutral. Politically, the neighbouring powers all tried to take influence, by way of mercenary commanders such as Jörg Jenatsch or Johann Rudolf Wettstein.

Despite the cantons' religious differences, the ''Tagsatzung

The Federal Diet of Switzerland (, ; ; ) was the legislative and executive council of the Old Swiss Confederacy and existed in various forms from the beginnings of Swiss independence until the formation of the Swiss federal state in 1848.

T ...

'' developed a strong consensus against any direct military involvement. The confederacy did not allow any foreign army to cross its territory: the alpine passes remained closed for Spain, just as an alliance offer of the Swedish King Gustav Adolph was rejected. The sole exception was the permission for the French army of Henri de Rohan to march through the Protestant cantons to the Grisons. A common defence was mounted only in 1647 when the Swedish armies reached Lake Constance

Lake Constance (, ) refers to three bodies of water on the Rhine at the northern foot of the Alps: Upper Lake Constance (''Obersee''), Lower Lake Constance (''Untersee''), and a connecting stretch of the Rhine, called the Seerhein (). These ...

again.

The Grisons

The Grisons (; ) or Graubünden (),Names include:

* ;

*Romansh language, Romansh:

**

**

**

**

**

**;

* ;

* ;

* .

See also list of European regions with alternative names#G, other names. more formally the Canton of the Grisons or the Canton ...

had no such luck. The Three Leagues

The Three Leagues, sometimes referred to as Raetia, was the 1471 alliance between the League of God's House, the League of the Ten Jurisdictions, and the Grey League. Its members were all Swiss Associates, associates of the Old Swiss Confederacy, ...

were a loose federation of 48 individual communes that were largely independent; their common assembly held no real powers. While this had helped avoid major religious wars during and following the Reformation, feuds between leading clans (e.g. between the ''von Planta'' and the ''von Salis'') were common. When such a feud spilled over into the Valtellina

Valtellina or the Valtelline (occasionally spelled as two words in English: Val Telline; (); or ; ; ) is a valley in the Lombardy region of northern Italy, bordering Switzerland. Today it is known for its ski centre, hot spring spas, bresa ...

in 1619, a subject territory of the Three Leagues, the population there responded in kind, killing the Protestant rulers in 1620 and calling Habsburg

The House of Habsburg (; ), also known as the House of Austria, was one of the most powerful dynasties in the history of Europe and Western civilization. They were best known for their inbreeding and for ruling vast realms throughout Europe d ...

Spain for help. For the next twenty years, the Grisons was ravaged by a war known as the Confusion of the Leagues. For the Habsburgs, the Grisons was a strategically important connection between Milan

Milan ( , , ; ) is a city in northern Italy, regional capital of Lombardy, the largest city in Italy by urban area and the List of cities in Italy, second-most-populous city proper in Italy after Rome. The city proper has a population of nea ...

and Austria

Austria, formally the Republic of Austria, is a landlocked country in Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine Federal states of Austria, states, of which the capital Vienna is the List of largest cities in Aust ...

. The Valtellina became Spanish, and other parts in the north-east of the Grisons were occupied and re-Catholicised by Austria.

France intervened a first time in 1624, but succeeded to drive the Spanish out of the Grisons only in 1636. However, Henri de Rohan's French army had to withdraw following the political intrigues of Jürg Jenatsch, who managed to play the French off against the Spaniards. Until 1639, the Three Leagues had re-acquired their whole territory, buying back the parts occupied by Austria. They even were restituted their subject territories in the south (Valtellina, Bormio

Bormio (, , ) is a town and ''comune'' with a population of about 4,100 located in the Province of Sondrio, Lombardy region of the Alps in northern Italy.

The centre of the upper Valtellina valley, it is a popular winter sports resort. It was the ...

, and Chiavenna), yet these had to remain Catholic under the protection of Milan.

The mayor of Basel, Johann Rudolf Wettstein, lobbied for a formal recognition of the Swiss confederacy

The Old Swiss Confederacy, also known as Switzerland or the Swiss Confederacy, was a loose confederation of independent small states (, German or ), initially within the Holy Roman Empire. It is the precursor of the modern state of Switzerlan ...

as an independent state in the peace of Westphalia

The Peace of Westphalia (, ) is the collective name for two peace treaties signed in October 1648 in the Westphalian cities of Osnabrück and Münster. They ended the Thirty Years' War (1618–1648) and brought peace to the Holy Roman Empire ...

. Although ''de facto'' independent since the end of the Swabian War

The Swabian War of 1499 ( (spelling depending on dialect), called or ("Swiss War") in Germany and ("War of the Engadin" in Austria) was the last major armed conflict between the Old Swiss Confederacy and the House of Habsburg. What had begun ...

in 1499, the confederacy was still officially a part of the Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire, also known as the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation after 1512, was a polity in Central and Western Europe, usually headed by the Holy Roman Emperor. It developed in the Early Middle Ages, and lasted for a millennium ...

. With the support of Henri II d'Orléans, who was also prince of Neuchâtel

Neuchâtel (, ; ; ) is a list of towns in Switzerland, town, a Municipalities of Switzerland, municipality, and the capital (political), capital of the cantons of Switzerland, Swiss canton of Neuchâtel (canton), Neuchâtel on Lake Neuchâtel ...

and the head of the French delegation, he succeeded to get the formal exemption from the empire for all cantons and associates of the confederacy.

Social developments

Historians count 13 (

Historians count 13 (Geneva

Geneva ( , ; ) ; ; . is the List of cities in Switzerland, second-most populous city in Switzerland and the most populous in French-speaking Romandy. Situated in the southwest of the country, where the Rhône exits Lake Geneva, it is the ca ...

) or 14 (St Gallen

St. Gallen is a Swiss city and the capital of the canton of St. Gallen. It evolved from the hermitage of Saint Gall, founded in the 7th century. Today, it is a large urban agglomeration (with around 167,000 inhabitants in 2019) and rep ...

) plague surges in Switzerland between 1500 and 1640, accounting for 31 plague years, and since 1580, smallpox

Smallpox was an infectious disease caused by Variola virus (often called Smallpox virus), which belongs to the genus '' Orthopoxvirus''. The last naturally occurring case was diagnosed in October 1977, and the World Health Organization (W ...

outbreaks with an especially high mortality rate (80–90 %) amongst children under the age of five occurred every four to five years. Nevertheless, the population in Switzerland grew in the 16th century from about 800,000 to roughly 1.1 million, i.e. by more than 35%.

Absolutism on the rise

This population growth caused significant changes in apre-industrial society

Pre-industrial society refers to social attributes and forms of political and cultural organization that were prevalent before the advent of the Industrial Revolution, which occurred from 1750 to 1850. ''Pre-industrial'' refers to a time befor ...

that could no longer significantly expand its territory. The dependence of the confederation on imports increased, and prices soared. In the countryside, settlements of estates increasingly led to smaller and smaller properties insufficient to sustain a family, and a new class of daytalers (''Tauner'') grew disproportionally. In the cities, too, the number of poor rose. At the same time, rural subject territories became more and more (financially) dependent on the cities. The political power was concentrated in a few rich families, that over time came to consider their offices as hereditary and tried to limit them to their own exclusive circle. This solicited the response of both peasants and free citizens, who resented such curtailing of their democratic rights, and around 1523/25, also fuelled by the reformatory spirit, revolts broke out in many cantons, both rural and urban. The main objective of the insurgents was the restitution of common rights of old, not the institution of a new order. Although commonly called the Peasants' War, the movement also included the free citizens, who saw their rights restricted in the cities, too. Contrary to the development in the Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire, also known as the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation after 1512, was a polity in Central and Western Europe, usually headed by the Holy Roman Emperor. It developed in the Early Middle Ages, and lasted for a millennium ...

, where the hostilities escalated and the rebellion was put down by force, there were only isolated armed conflicts in the confederation. The authorities, already involved in reformatory or counter-reformatory activities, managed to subdue these uprisings only by granting concessions. Yet the absolutist tendencies kept slowly transforming the democrat cantons into oligarchies

Oligarchy (; ) is a form of government in which power rests with a small number of people. Members of this group, called oligarchs, generally hold usually hard, but sometimes soft power through nobility, fame, wealth, or education; or thr ...

. By 1650, the absolutist order was firmly established and would prevail for another 150 years as the Ancien Régime

''Ancien'' may refer to

* the French word for " ancient, old"

** Société des anciens textes français

* the French for "former, senior"

** Virelai ancien

** Ancien Régime

** Ancien Régime in France

{{disambig ...

.

Persecution of heretics

The generally widespread intolerance of the time, as witnessed by theInquisition

The Inquisition was a Catholic Inquisitorial system#History, judicial procedure where the Ecclesiastical court, ecclesiastical judges could initiate, investigate and try cases in their jurisdiction. Popularly it became the name for various med ...

, amplified by the conflicts between Protestants and Catholics, left no place for dissenters. Anabaptist

Anabaptism (from Neo-Latin , from the Greek language, Greek : 're-' and 'baptism'; , earlier also )Since the middle of the 20th century, the German-speaking world no longer uses the term (translation: "Re-baptizers"), considering it biased. ...

s, who took the idea of deriving new societal rules from the direct study of Biblical sources even further than the Protestant reformers only into conflict not only with the established Churches over the question of baptism

Baptism (from ) is a Christians, Christian sacrament of initiation almost invariably with the use of water. It may be performed by aspersion, sprinkling or affusion, pouring water on the head, or by immersion baptism, immersing in water eit ...

but also with the civil authorities because, not having found any Biblical justification, they refused to pay taxes or to accept any authority. Both Catholic and Protestant cantons persecuted them with all their might. Following the forced drowning

Drowning is a type of Asphyxia, suffocation induced by the submersion of the mouth and nose in a liquid. Submersion injury refers to both drowning and near-miss incidents. Most instances of fatal drowning occur alone or in situations where othe ...

of Felix Manz in the Limmat

The Limmat is a river in Switzerland. The river commences at the outfall of Lake Zurich, in the southern part of the city of Zurich. From Zurich it flows in a northwesterly direction, continuing a further 35 km until it reaches the river A ...

in Zürich in 1527, many Anabaptists emigrated to Moravia

Moravia ( ; ) is a historical region in the eastern Czech Republic, roughly encompassing its territory within the Danube River's drainage basin. It is one of three historical Czech lands, with Bohemia and Czech Silesia.

The medieval and early ...

. Antitrinitarian

Nontrinitarianism is a form of Christianity that rejects the orthodox Christian theology of the Trinity—the belief that God is three distinct hypostases or persons who are coeternal, coequal, and indivisibly united in one being, or essence ...

s fared no better; Miguel Servet was burned at the stake

Death by burning is an list of execution methods, execution, murder, or suicide method involving combustion or exposure to extreme heat. It has a long history as a form of public capital punishment, and many societies have employed it as a puni ...

in Geneva on 27 October 1553.

There was no individual freedom of religion

Freedom of religion or religious liberty, also known as freedom of religion or belief (FoRB), is a principle that supports the freedom of an individual or community, in public or private, to manifest religion or belief in teaching, practice ...

in Switzerland—or indeed all of Europe—at that time anyway. The maxim of ''cuius regio, eius religio

() is a Latin phrase which literally means "whose realm, his religion" – meaning that the religion of the ruler was to dictate the religion of those ruled. This legal principle marked a major development in the collective (if not individual) ...

'' ("whose region, his religion") meant that subjects had to adopt the faith of their rulers. Dissenters who didn't want to convert typically had to (but also were allowed to) emigrate elsewhere, into a region where their faith ''was'' the state religion. The Bullinger family, for instance, had to move from Bremgarten in the Freiamt, which was re-Catholicised after the second war of Kappel, to the Protestant city of Zürich.

The 16th century also saw the height of witch-hunt

A witch hunt, or a witch purge, is a search for people who have been labeled witches or a search for evidence of witchcraft. Practicing evil spells or Incantation, incantations was proscribed and punishable in early human civilizations in the ...

s in Europe, and Switzerland was no exception. Beginning about 1530, culminating around 1600, and then slowly diminishing, numerous witch trial

A witch hunt, or a witch purge, is a search for people who have been labeled witches or a search for evidence of witchcraft. Practicing evil spells or Incantation, incantations was proscribed and punishable in early human civilizations in the ...

s were held in both Protestant and Catholic cantons. These often ended with death sentences (usually burning) for the accused, who typically were elderly women, crippled persons, or other social outcasts.

Science and arts: the Renaissance in Switzerland

Humanism

Humanism is a philosophy, philosophical stance that emphasizes the individual and social potential, and Agency (philosophy), agency of human beings, whom it considers the starting point for serious moral and philosophical inquiry.

The me ...

and the Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) is a Periodization, period of history and a European cultural movement covering the 15th and 16th centuries. It marked the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and was characterized by an effort to revive and sur ...

led to new advances in science and the arts. Paracelsus

Paracelsus (; ; 1493 – 24 September 1541), born Theophrastus von Hohenheim (full name Philippus Aureolus Theophrastus Bombastus von Hohenheim), was a Swiss physician, alchemist, lay theologian, and philosopher of the German Renaissance.

H ...

taught at the University of Basel

The University of Basel (Latin: ''Universitas Basiliensis''; German: ''Universität Basel'') is a public research university in Basel, Switzerland. Founded on 4 April 1460, it is Switzerland's oldest university and among the world's oldest univ ...

. Hans Holbein ''the Younger'' worked until 1526 in Basel; his high renaissance style had a profound influence on Swiss painters. Conrad Gessner in Zürich did studies in systematic botany

Botany, also called plant science, is the branch of natural science and biology studying plants, especially Plant anatomy, their anatomy, Plant taxonomy, taxonomy, and Plant ecology, ecology. A botanist or plant scientist is a scientist who s ...

, and the geographic maps and city views produced e.g. by Matthäus Merian Matthäus is a given name or surname. Notable people with the name include:

;Surname

* Lothar Matthäus, (born 1961), German former football player and manager

;Given name

* Matthäus Aurogallus, Professor of Hebrew at the University of Wittenberg ...

show the beginning of a scientific cartography

Cartography (; from , 'papyrus, sheet of paper, map'; and , 'write') is the study and practice of making and using maps. Combining science, aesthetics and technique, cartography builds on the premise that reality (or an imagined reality) can ...

. In 1601, an early version of the theodolite

A theodolite () is a precision optical instrument for measuring angles between designated visible points in the horizontal and vertical planes. The traditional use has been for land surveying, but it is also used extensively for building and ...

was invented in Zürich and promptly used to triangulate the city. Basel and Geneva became important printing centres, with an output equal to that of e.g. Strasbourg or Lyon. Their printing reformatory tracts greatly furthered the dissemination of these ideas. First newspapers appeared towards the end of the 16th century, but disappeared soon again due to the censorship of the absolutist authorities. In architecture, there was a strong Italian and especially florentine influence, visible in many a rich magistrate's town house. Famed baroque

The Baroque ( , , ) is a Western Style (visual arts), style of Baroque architecture, architecture, Baroque music, music, Baroque dance, dance, Baroque painting, painting, Baroque sculpture, sculpture, poetry, and other arts that flourished from ...

architect Francesco Borromini

Francesco Borromini (, ), byname of Francesco Castelli (; 25 September 1599 – 2 August 1667), was an Italian architect born in the modern Switzerland, Swiss canton of Ticino

was born 1599 in the Ticino

Ticino ( ), sometimes Tessin (), officially the Republic and Canton of Ticino or less formally the Canton of Ticino, is one of the Canton of Switzerland, 26 cantons forming the Switzerland, Swiss Confederation. It is composed of eight districts ...

.

Many Huguenot

The Huguenots ( , ; ) are a Religious denomination, religious group of French people, French Protestants who held to the Reformed (Calvinist) tradition of Protestantism. The term, which may be derived from the name of a Swiss political leader, ...

s and other Protestant refugees from all over Europe fled to Basel, Geneva, and Neuchâtel. Geneva under Calvin and his successor Theodore Beza

Theodore Beza (; or ''de Besze''; 24 June 1519 – 13 October 1605) was a French Calvinist Protestant theologian, reformer and scholar who played an important role in the Protestant Reformation. He was a disciple of John Calvin and lived most ...

demanded their naturalisation and strict adherence to the Calvinist doctrine, whereas Basel, where the university had re-opened in 1532, became a center of intellectual freedom. Many of these immigrants were skilled craftsmen or businessmen and contributed greatly to the development of banking and the watch industry.

See also

* First War of Villmergen * History of the Grisons *Swiss Reformed Church

The Protestant Church in Switzerland (PCS), formerly named Federation of Swiss Protestant Churches until 31 December 2019, is a federation of 25 member churches – 24 cantonal churches and the Evangelical-Methodist Church of Switzerland. The P ...

* Toggenburg War (or Second War of Villmergen)

* Otto Zeinenger

Notes and references

The main sources used are * . *Im Hof, U.: ''Geschichte der Schweiz'', 7th ed.Kohlhammer Verlag

W. Kohlhammer Verlag GmbH, or Kohlhammer Verlag, is a German publishing house headquartered in Stuttgart.

History

Kohlhammer Verlag was founded in Stuttgart on 30 April 1866 by . Kohlhammer had taken over the businesses of his late father-in-la ...

, 1974/2001. .

*Schwabe & Co.: ''Geschichte der Schweiz und der Schweizer'', Schwabe & Co 1986/2004. .

Other sources:

Further reading

*Gordon, Bruce. ''The Swiss Reformation''. University of Manchester Press, 2002. . *Miller, Andrew. ''Miller's Church History''. 1880. Chapter 41. *Gilbert, W.:Renaissance and Reformation

'.

University of Kansas

The University of Kansas (KU) is a public research university with its main campus in Lawrence, Kansas, United States. Two branch campuses are in the Kansas City metropolitan area on the Kansas side: the university's medical school and hospital ...

, Lawrence, Kansas: Carrie, 1998.

*Luck, James M.: ''A History of Switzerland / The First 100,000 Years: Before the Beginnings to the Days of the Present'', Society for the Promotion of Science & Scholarship, Palo Alto 1986. .

*Marabello, Thomas Quinn (2021) "The 500th Anniversary of the Swiss Reformation: How Zwingli changed and continues to impact Switzerland today," ''Swiss American Historical Society Review'', Vol. 57: No. 1. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/sahs_review/vol57/iss1/3

*Ranan, David. ''Double Cross – The Code of the Catholic Church''. Theo Press Ltd, 2006.

*Burnett, Amy Nelson and Campi, Emidio (eds.). ''A Companion to the Swiss Reformation'', Leiden – Boston: Brill, 2016.

*Guerra, C, Harich-Schwarzbauer, H, and Hindermann, Judith ''Johannes Atrocianus – Text, Übersetzung, Kommentar''. Hildesheim: Georg Olms Verlag, 2018.

External links

Reformation in Switzerland

by Markus Jud. In English, also available in French and German.

by "Presence Switzerland", an official body of the Swiss Confederation. (In English, available also i

) *

in Geneva in 1602.

(English transcription).

in German. {{DEFAULTSORT:Reformation in Switzerland 16th-century establishments in the Old Swiss Confederacy History of Switzerland by period