Sverdlov (other) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Yakov Mikhailovich Sverdlov ( – 16 March 1919) was a Russian revolutionary and Soviet politician. A key

Sverdlov was born in

Sverdlov was born in  Sverdlov became a major activist and speaker in Nizhny Novgorod. In 1906, Sverdlov was arrested and held in the Yekaterinburg prison until his release. During his time in prison, Sverdlov continued to educate himself and others, reading Lenin,

Sverdlov became a major activist and speaker in Nizhny Novgorod. In 1906, Sverdlov was arrested and held in the Yekaterinburg prison until his release. During his time in prison, Sverdlov continued to educate himself and others, reading Lenin,

Following the assassination of

Following the assassination of

Sverdlov was married to a meteorologist, Klavdia Novgorodtseva (1876–1960), who had joined the Bolsheviks in

Sverdlov was married to a meteorologist, Klavdia Novgorodtseva (1876–1960), who had joined the Bolsheviks in

* In a speech on 18 March 1919 Vladimir Lenin praised Sverdlov and his contributions to the revolution. He called Sverdlov "the most perfectly complete type of professional revolutionary."

* The Central School for Soviet and Party Work, housed in the former Merchants House, Moscow was renamed the

* In a speech on 18 March 1919 Vladimir Lenin praised Sverdlov and his contributions to the revolution. He called Sverdlov "the most perfectly complete type of professional revolutionary."

* The Central School for Soviet and Party Work, housed in the former Merchants House, Moscow was renamed the

Leon Trotsky: Jacob Sverdlov – 1925 memorial essay

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Sverdlov, Yakov 1885 births 1919 deaths Politicians from Nizhny Novgorod People from Nizhegorodsky Uyezd Jewish Russian politicians Russian Social Democratic Labour Party members Old Bolsheviks Heads of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union Members of the Orgburo of the 7th Congress of the Russian Communist Party (Bolsheviks) Members of the Secretariat of the 7th Congress of the Russian Communist Party (Bolsheviks) Members of the Bureau of the 7th Congress of the Russian Communist Party (Bolsheviks) Members of the Central Committee of the 6th Conference of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (Bolsheviks) Members of the Central Committee of the 7th Conference of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (Bolsheviks) Members of the Central Committee of the 6th Congress of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (Bolsheviks) Members of the Central Committee of the 7th Congress of the Russian Communist Party (Bolsheviks) People of the Russian Revolution of 1905 Jewish socialists Jewish Soviet politicians Russian communists People of the Russian Revolution People of the Russian Civil War Heads of state of Russia Anti-monarchists Perpetrators of the Red Terror (Russia) Regicides of Nicholas II Russian revolutionaries Deaths from the Spanish flu pandemic Infectious disease deaths in Russia Burials at the Kremlin Wall Necropolis

Bolshevik

The Bolsheviks, led by Vladimir Lenin, were a radical Faction (political), faction of the Marxist Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP) which split with the Mensheviks at the 2nd Congress of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party, ...

organizer of the October Revolution

The October Revolution, also known as the Great October Socialist Revolution (in Historiography in the Soviet Union, Soviet historiography), October coup, Bolshevik coup, or Bolshevik revolution, was the second of Russian Revolution, two r ...

of 1917, Sverdlov served as chairman

The chair, also chairman, chairwoman, or chairperson, is the presiding officer of an organized group such as a board, committee, or deliberative assembly. The person holding the office, who is typically elected or appointed by members of the gro ...

of the Secretariat

Secretariat may refer to:

* Secretariat (administrative office)

* Secretariat (horse)

Secretariat (March 30, 1970 – October 4, 1989), also known as Big Red, was a champion American thoroughbred horse racing, racehorse who was the ninth winn ...

of the Russian Communist Party Communist Party of Russia might refer to:

* Russian Social Democratic Labour Party, founded in 1898 – the forerunner of the Russian Communist Party (Bolsheviks)

* Communist Party of the Soviet Union, formally established in 1912 and known origina ...

from 1918 until his death in 1919, and as chairman

The chair, also chairman, chairwoman, or chairperson, is the presiding officer of an organized group such as a board, committee, or deliberative assembly. The person holding the office, who is typically elected or appointed by members of the gro ...

of the All-Russian Central Executive Committee

The All-Russian Central Executive Committee () was (June – November 1917) a permanent body formed by the First All-Russian Congress of Soviets of Workers' and Soldiers' Deputies (held from June 16 to July 7, 1917 in Petrograd), then became the ...

(head of state) from 1917 until his death in 1919.

Born in Nizhny Novgorod

Nizhny Novgorod ( ; rus, links=no, Нижний Новгород, a=Ru-Nizhny Novgorod.ogg, p=ˈnʲiʐnʲɪj ˈnovɡərət, t=Lower Newtown; colloquially shortened to Nizhny) is a city and the administrative centre of Nizhny Novgorod Oblast an ...

to a Jewish

Jews (, , ), or the Jewish people, are an ethnoreligious group and nation, originating from the Israelites of History of ancient Israel and Judah, ancient Israel and Judah. They also traditionally adhere to Judaism. Jewish ethnicity, rel ...

family active in revolutionary politics, Sverdlov joined the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party

The Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP), also known as the Russian Social Democratic Workers' Party (RSDWP) or the Russian Social Democratic Party (RSDP), was a socialist political party founded in 1898 in Minsk, Russian Empire. The ...

in 1902 and supported Vladimir Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov ( 187021 January 1924), better known as Vladimir Lenin, was a Russian revolutionary, politician and political theorist. He was the first head of government of Soviet Russia from 1917 until Death and state funeral of ...

's Bolshevik faction from 1903. He was active in the Urals

The Ural Mountains ( ),; , ; , or simply the Urals, are a mountain range in Eurasia that runs north–south mostly through Russia, from the coast of the Arctic Ocean to the river Ural (river), Ural and northwestern Kazakhstan.

during the failed Revolution of 1905

The Russian Revolution of 1905, also known as the First Russian Revolution, was a revolution in the Russian Empire which began on 22 January 1905 and led to the establishment of a constitutional monarchy under the Russian Constitution of 1906, t ...

, and over the next decade was subjected to constant imprisonment and exile. After the 1917 February Revolution

The February Revolution (), known in Soviet historiography as the February Bourgeois Democratic Revolution and sometimes as the March Revolution or February Coup was the first of Russian Revolution, two revolutions which took place in Russia ...

overthrew the monarchy, Sverdlov returned to Petrograd

Saint Petersburg, formerly known as Petrograd and later Leningrad, is the second-largest city in Russia after Moscow. It is situated on the River Neva, at the head of the Gulf of Finland on the Baltic Sea. The city had a population of 5,601, ...

and was appointed a secretary of the party's central committee. In this capacity, he played a key role in planning the October Revolution, in which the Bolsheviks came to power. Sverdlov became one of most powerful figures in the Soviet regime, with Lenin, Leon Trotsky

Lev Davidovich Bronstein ( – 21 August 1940), better known as Leon Trotsky,; ; also transliterated ''Lyev'', ''Trotski'', ''Trockij'' and ''Trotzky'' was a Russian revolutionary, Soviet politician, and political theorist. He was a key figure ...

, and Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Dzhugashvili; 5 March 1953) was a Soviet politician and revolutionary who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until Death and state funeral of Joseph Stalin, his death in 1953. He held power as General Secret ...

.

In November 1917, Sverdlov was elected chairman of the All-Russian Central Executive Committee, the ''de facto'' head of state. He worked to consolidate Bolshevik control of the new regime and supported the Red Terror

The Red Terror () was a campaign of political repression and Mass killing, executions in Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic, Soviet Russia which was carried out by the Bolsheviks, chiefly through the Cheka, the Bolshevik secret police ...

campaign and decossackization

De-Cossackization () was the Bolshevik policy of systematic repression against the Cossacks in the former Russian Empire between 1919 and 1933, especially the Don and Kuban Cossacks in Russia, aimed at the elimination of the Cossacks as a dist ...

policies. He played major roles in the dissolution of the Constituent Assembly

A constituent assembly (also known as a constitutional convention, constitutional congress, or constitutional assembly) is a body assembled for the purpose of drafting or revising a constitution. Members of a constituent assembly may be elected b ...

in January 1918, in persuading party members to support the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk

The Treaty of Brest-Litovsk was a separate peace treaty signed on 3 March 1918 between Soviet Russia and the Central Powers (Germany, Austria-Hungary, the Ottoman Empire, and Bulgaria), by which Russia withdrew from World War I. The treaty, whi ...

signed with the Central Powers

The Central Powers, also known as the Central Empires,; ; , ; were one of the two main coalitions that fought in World War I (1914–1918). It consisted of the German Empire, Austria-Hungary, the Ottoman Empire, and the Kingdom of Bulga ...

that March, and in authorising the execution of the Romanov family

The abdicated Russian Imperial Romanov family (Tsar Nicholas II of Russia, his wife Alexandra Feodorovna (Alix of Hesse), Alexandra Feodorovna, and their five children: Grand Duchess Olga Nikolaevna of Russia, Olga, Grand Duchess Tatiana Nikola ...

that July. He also served briefly as acting head of government after Lenin was injured in an assassination attempt in August.

In March 1919, Sverdlov died at age 33 of the Spanish flu

The 1918–1920 flu pandemic, also known as the Great Influenza epidemic or by the common misnomer Spanish flu, was an exceptionally deadly global influenza pandemic caused by the H1N1 subtype of the influenza A virus. The earliest docum ...

, and was buried in the Kremlin Wall Necropolis

The Kremlin Wall Necropolis is the former national cemetery of the Soviet Union, located in Red Square in Moscow beside the Moscow Kremlin Wall, Kremlin Wall. Burials there began in November 1917, when 240 pro-Bolsheviks who died during the Mosc ...

. The city of Yekaterinburg

Yekaterinburg (, ; ), alternatively Romanization of Russian, romanized as Ekaterinburg and formerly known as Sverdlovsk ( ; 1924–1991), is a city and the administrative centre of Sverdlovsk Oblast and the Ural Federal District, Russia. The ci ...

(Sverdlovsk) and Theatre Square in Moscow were renamed in his honour. Some historians regard his untimely death as a key factor which enabled the rise of Stalin after Lenin's death in 1924, as Sverdlov was a natural candidate for the post of General Secretary held by Stalin from 1922.

Early life

Sverdlov was born in

Sverdlov was born in Nizhny Novgorod

Nizhny Novgorod ( ; rus, links=no, Нижний Новгород, a=Ru-Nizhny Novgorod.ogg, p=ˈnʲiʐnʲɪj ˈnovɡərət, t=Lower Newtown; colloquially shortened to Nizhny) is a city and the administrative centre of Nizhny Novgorod Oblast an ...

as Yakov-Aaron Mikhailovich Sverdlov to Jewish

Jews (, , ), or the Jewish people, are an ethnoreligious group and nation, originating from the Israelites of History of ancient Israel and Judah, ancient Israel and Judah. They also traditionally adhere to Judaism. Jewish ethnicity, rel ...

parents, Mikhail Izrailevich Sverdlov and Elizaveta Solomonova. His father was a politically active engraver who produced forged

Forging is a manufacturing process involving the shaping of metal using localized compression (physics), compressive forces. The blows are delivered with a hammer (often a power hammer) or a die (manufacturing), die. Forging is often classif ...

documents and stored arms for the revolutionary underground. The Sverdlov family had six children: two daughters (Sophia and Sara) and four sons (Zinovy, Yakov, Veniamin, and Lev). After his wife's death in 1900, Mikhail converted with his family to the Russian Orthodox Church

The Russian Orthodox Church (ROC; ;), also officially known as the Moscow Patriarchate (), is an autocephaly, autocephalous Eastern Orthodox Church, Eastern Orthodox Christian church. It has 194 dioceses inside Russia. The Primate (bishop), p ...

, married Maria Aleksandrovna Kormiltseva, and had two more sons, Herman and Alexander. Sverdlov's father was sympathetic to his children's socialist tendencies and 5 out of his 6 children would become involved in revolutionary politics at some point. Mikhail watched as his household slowly became a revolutionary hotspot, where the Novgorod Social Democrats would meet, write pamphlets, and even forge stamps for false passports. Yakov's eldest brother Zinovy was adopted by Maxim Gorky

Alexei Maximovich Peshkov (; – 18 June 1936), popularly known as Maxim Gorky (; ), was a Russian and Soviet writer and proponent of socialism. He was nominated five times for the Nobel Prize in Literature. Before his success as an aut ...

, who was a frequent guest at the house. Zinovy was the only Sverdlov to reject revolutionary politics and had little to no contact with Yakov after the revolution.

Yakov excelled at school, and after 4 years in gymnasium left to become a pharmacist's apprentice and a "professional revolutionary," Sverdlov joined while a teenager the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party

The Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP), also known as the Russian Social Democratic Workers' Party (RSDWP) or the Russian Social Democratic Party (RSDP), was a socialist political party founded in 1898 in Minsk, Russian Empire. The ...

in 1902, and then later the Bolshevik faction, supporting Vladimir Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov ( 187021 January 1924), better known as Vladimir Lenin, was a Russian revolutionary, politician and political theorist. He was the first head of government of Soviet Russia from 1917 until Death and state funeral of ...

.

In his youth, Sverdlov became friends with a fellow revolutionary Vladimir Lubotsky (later known as Zagorsky). He was involved in the 1905 revolution

The Russian Revolution of 1905, also known as the First Russian Revolution, was a revolution in the Russian Empire which began on 22 January 1905 and led to the establishment of a constitutional monarchy under the Russian Constitution of 1906, t ...

while living in the Ural Mountains

The Ural Mountains ( ),; , ; , or simply the Urals, are a mountain range in Eurasia that runs north–south mostly through Russia, from the coast of the Arctic Ocean to the river Ural (river), Ural and northwestern Kazakhstan.

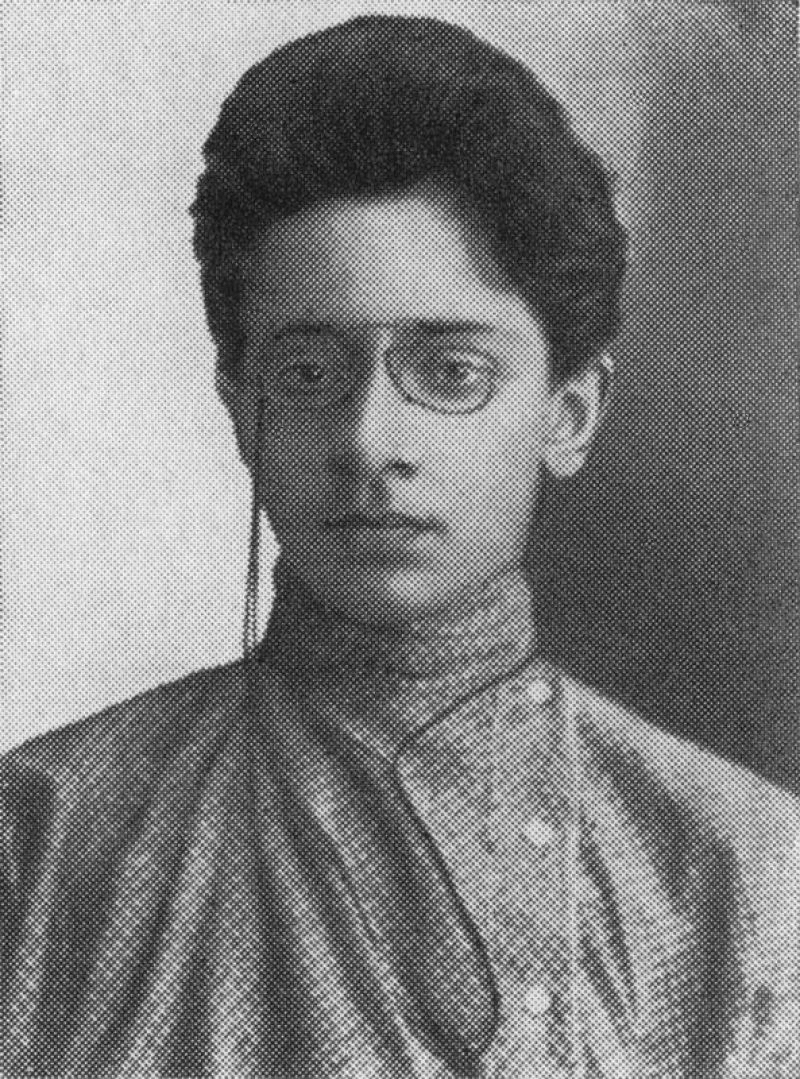

. Though never actually attending college, Sverdlov adopted the garb of the radical students at the time – "With his medium height, unruly brown hair, glasses continually perched on his nose, and Tolstoy shirt worn under his jacket, Sverdlov looked like a student, and for us...a student meant a revolutionary."

Sverdlov became a major activist and speaker in Nizhny Novgorod. In 1906, Sverdlov was arrested and held in the Yekaterinburg prison until his release. During his time in prison, Sverdlov continued to educate himself and others, reading Lenin,

Sverdlov became a major activist and speaker in Nizhny Novgorod. In 1906, Sverdlov was arrested and held in the Yekaterinburg prison until his release. During his time in prison, Sverdlov continued to educate himself and others, reading Lenin, Marx

Karl Marx (; 5 May 1818 – 14 March 1883) was a German philosopher, political theorist, economist, journalist, and revolutionary socialist. He is best-known for the 1848 pamphlet '' The Communist Manifesto'' (written with Friedrich Engels) ...

, Kautsky, Heine

Heine is both a surname and a given name of German origin. People with that name include:

People with the surname

* Albert Heine (1867–1949), German actor

* Alice Heine (1858–1925), American-born princess of Monaco

* Armand Heine (1818–1883) ...

, and more. Sverdlov attempted to live by the motto: "I put books to the test of life, and life to the test of books." For most of the time from his arrest in June 1906 until 1917 he was either imprisoned or exiled. In March 1911, Sverdlov was held in the Saint Petersburg House of Pretrial Detention.

During the period 1914–1916 he was in internal exile in Turukhansk

Turukhansk () is a rural locality (a '' selo'') and the administrative center of Turukhansky District of Krasnoyarsk Krai, Russia, located north of Krasnoyarsk, at the confluence of the Yenisey and Nizhnyaya Tunguska Rivers. Until 1924, the t ...

, Siberia

Siberia ( ; , ) is an extensive geographical region comprising all of North Asia, from the Ural Mountains in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east. It has formed a part of the sovereign territory of Russia and its predecessor states ...

, along with Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Dzhugashvili; 5 March 1953) was a Soviet politician and revolutionary who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until Death and state funeral of Joseph Stalin, his death in 1953. He held power as General Secret ...

(then known as Dzhugashvili). Both had been betrayed by the Okhrana

The Department for the Protection of Public Safety and Order (), usually called the Guard Department () and commonly abbreviated in modern English sources as the Okhrana ( rus , Охрана, p=ɐˈxranə, a=Ru-охрана.ogg, t= The Guard) w ...

agent Roman Malinovsky

Roman Vatslavovich Malinovsky (; 18 March 1876 – 5 November 1918) was a prominent Bolshevik politician before the Russian revolution, while at the same time working as the best-paid agent for the Okhrana, the Tsarist secret police. They codena ...

. Of Stalin, Sverdlov wrote "The comrade I was with turned out to be such a person, socially, that we didn't talk or see each other. It was terrible." Sverdlov, like Stalin, was co-opted ''in absentia'' to the 1912 Prague Conference

The Prague Conference, officially the 6th All-Russian Conference of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party, was held in Prague, Austria-Hungary (Present-Day Czechia), on 5–17 January 1912. Sixteen Bolsheviks and two Mensheviks attended, alt ...

. In 1914, Sverdlov moved to a different village, moving in with his friend Filipp Goloshchyokin

Filipp Isayevich Goloshchyokin () (born Shaya Itsikovich Goloshchyokin) () ( – October 28, 1941) was a Jewish-Russian Bolshevik revolutionary, Soviet politician, and party functionary.

A member of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party s ...

, known as Georges. In early 1917, Sverdlov received news of the Putilov strike of 1917 in Petrograd. Alongside Goloshchyokin, he set out at once, arriving in Petrograd on 29 March 1917.

Party leader

After the 1917February Revolution

The February Revolution (), known in Soviet historiography as the February Bourgeois Democratic Revolution and sometimes as the March Revolution or February Coup was the first of Russian Revolution, two revolutions which took place in Russia ...

Sverdlov returned to Petrograd

Saint Petersburg, formerly known as Petrograd and later Leningrad, is the second-largest city in Russia after Moscow. It is situated on the River Neva, at the head of the Gulf of Finland on the Baltic Sea. The city had a population of 5,601, ...

from exile as head of the Urals Delegation and found his way into Lenin's inner circle. He first met Lenin in April 1917, and was elected as one of five members of the Central Committee's Secretariat

Secretariat may refer to:

* Secretariat (administrative office)

* Secretariat (horse)

Secretariat (March 30, 1970 – October 4, 1989), also known as Big Red, was a champion American thoroughbred horse racing, racehorse who was the ninth winn ...

in August 1917, after which he usurped Elena Stasova

Elena Dmitriyevna Stasova (; 15 October Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.html" ;"title="nowiki/>Old Style and New Style dates">O.S. 3 October1873 – 31 December 1966) was a Russian Soviet people">Soviet revolutionary, Old Bolshevik and an early le ...

as the body's leading figure. In March 1918, he was elected Chairman of the Secretariat. According to Podvoisky, the chairperson of the Military Revolutionary Committee

The Military Revolutionary Committee (Milrevcom; , ) was the name for military organs created by the Bolsheviks under the soviets in preparation for the October Revolution (October 1917 – March 1918).

, "The person who did more than anyone to help Lenin with the practicalities of translating convictions into votes was Sverdlov." As chairman of the Central Committee, Yakov played an important role in planning the October Revolution

The October Revolution, also known as the Great October Socialist Revolution (in Historiography in the Soviet Union, Soviet historiography), October coup, Bolshevik coup, or Bolshevik revolution, was the second of Russian Revolution, two r ...

and helped make the decision to stage an armed uprising. In November as the Bolsheviks debated whether to postpone or hold elections

An election is a formal group decision-making process whereby a population chooses an individual or multiple individuals to hold public office.

Elections have been the usual mechanism by which modern representative democracy has operated ...

, Sverdlov advocated for immediate elections as promised. When the results came back showing that the Socialist Revolutionaries

The Socialist Revolutionary Party (SR; ,, ) was a major socialist political party in the late Russian Empire, during both phases of the Russian Revolution, and in early Soviet Russia. The party members were known as Esers ().

The SRs were agr ...

had won, Sverdlov, Lenin, and Bukharin

Nikolai Ivanovich Bukharin (; rus, Николай Иванович Бухарин, p=nʲɪkɐˈlaj ɪˈvanəvʲɪdʑ bʊˈxarʲɪn; – 15 March 1938) was a Russian revolutionary, Soviet politician, and Marxist theorist. A prominent Bolshevik ...

dissolved the assembly, leading to a civil war.

Sverdlov is sometimes regarded as the first head of state of the Soviet Union, although it was not established until 1922, three years after his death. Sverdlov had a prodigious memory and was able to retain the names and details of fellow revolutionaries in exile. He promoted his friend and suite-mate Varlam Avanesov to second-in-command at the Central Executive Committee, and would later become a top official of the secret police. He also installed Vladimir Volodarsky as commissar of print, propaganda, and agitation until his assassination in 1918. His organizational capability was well-regarded, and during his chairmanship, thousands of local party committees were initiated. One of his comrades recalled that,

ecould tell you everything you needed to know about a comrade: where he was working, what kind of person he was, what he was good at, and what job he should be assigned to in the interests of the cause and for his benefit. Moreover, Sverdlov had a very precise impression of all the comrades: they were so firmly stamped in his memory that he could tell you all about the company each one kept. It is hard to believe, but true.Sverdlov was elected chairman of the

All-Russian Central Executive Committee

The All-Russian Central Executive Committee () was (June – November 1917) a permanent body formed by the First All-Russian Congress of Soviets of Workers' and Soldiers' Deputies (held from June 16 to July 7, 1917 in Petrograd), then became the ...

in November 1917, of which his wife was also a part, becoming therefore ''de jure'' head of state of the Russian SFSR

The Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic (Russian SFSR or RSFSR), previously known as the Russian Socialist Federative Soviet Republic and the Russian Soviet Republic, and unofficially as Soviet Russia,Declaration of Rights of the labo ...

until his death. He played important roles in the decision in January 1918 to end the Russian Constituent Assembly

The All Russian Constituent Assembly () was a constituent assembly convened in Russia after the February Revolution of 1917. It met for 13 hours, from 4 p.m. to 5 a.m., , whereupon it was dissolved by the Bolshevik-led All-Russian Central Ex ...

and the subsequent signing on 3 March of the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk

The Treaty of Brest-Litovsk was a separate peace treaty signed on 3 March 1918 between Soviet Russia and the Central Powers (Germany, Austria-Hungary, the Ottoman Empire, and Bulgaria), by which Russia withdrew from World War I. The treaty, whi ...

. In March 1918 Sverdlov along with most prominent Bolsheviks fled Petrograd and moved the government headquarters to Moscow – the Sverdlovs moved into a room in the Kremlin.

In March 1918, Sverdlov and the Central Executive Committee discussed how to best remove the "ulcers that socialism has inherited from capitalism" and Yakov advocated for a concentrated effort to turn the poorest peasants in the villages against their kulak

Kulak ( ; rus, кула́к, r=kulák, p=kʊˈɫak, a=Ru-кулак.ogg; plural: кулаки́, ''kulakí'', 'fist' or 'tight-fisted'), also kurkul () or golchomag (, plural: ), was the term which was used to describe peasants who owned over ...

brethren. Alongside Bukharin, the party began a campaign of "concentrated violence" against many members of the landowning, capitalist, and tradesman classes of Russian society.

Romanov family

A number of sources claim that Sverdlov, alongside Lenin and Goloshchyokin, played a major role in the execution of Tsar Nicholas II and his family on 17 July 1918. A book written in 1990 by the Moscow playwrightEdvard Radzinsky

Edvard Stanislavovich Radzinsky (; born September 23, 1936) is a Russian historian, playwright, television personality, and screenwriter. He authored more than forty history books that are popular in Russia.

Biography

Edvard Stanislavovich Rad ...

claims that Sverdlov ordered their execution on 16 July 1918. This book and other Radzinsky books were characterized as " folk history" by journalists and academic historians. However Yuri Slezkine in his book ''The Jewish Century'' expressed a slightly different opinion: "Early in the Civil War, in June 1918, Lenin ordered the killing of Nicholas II and his family. Among the men entrusted with carrying out the orders were Sverdlov, Filipp Goloshchyokin

Filipp Isayevich Goloshchyokin () (born Shaya Itsikovich Goloshchyokin) () ( – October 28, 1941) was a Jewish-Russian Bolshevik revolutionary, Soviet politician, and party functionary.

A member of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party s ...

and Yakov Yurovsky

Yakov Mikhailovich Yurovsky (, ; Unless otherwise noted, all dates used in this article are of the Gregorian Calendar, as opposed to the Julian Calendar which was used in Russia prior to . – 2 August 1938) was a Russian Bolshevik revoluti ...

".

The 1922 book by a White Army

The White Army, also known as the White Guard, the White Guardsmen, or simply the Whites, was a common collective name for the armed formations of the White movement and Anti-Sovietism, anti-Bolshevik governments during the Russian Civil War. T ...

general, Mikhail Diterikhs

Mikhail Konstantinovich Diterikhs (, ; May 17, 1874 – September 9, 1937) served as a general in the Imperial Russian Army and subsequently became a key figure in the monarchist White movement in Siberia and the Russian Far East area during the R ...

, ''The Murder of the Tsar's Family and members of the House of Romanov in the Urals'', sought to portray the murder of the royal family as a Jewish plot against Russia. It referred to Sverdlov by his Jewish nickname "Yankel" and to Goloshchekin as "Isaac". This book in turn was based on an account by one Nikolai Sokolov, special investigator for the Omsk

Omsk (; , ) is the administrative center and largest types of inhabited localities in Russia, city of Omsk Oblast, Russia. It is situated in southwestern Siberia and has a population of over one million. Omsk is the third List of cities and tow ...

regional court, whom Diterikhs assigned with the task of investigating the disappearance of the Romanovs while serving as regional governor under the White regime during the Russian Civil War

The Russian Civil War () was a multi-party civil war in the former Russian Empire sparked by the 1917 overthrowing of the Russian Provisional Government in the October Revolution, as many factions vied to determine Russia's political future. I ...

. The investigating magistrate in Ekaterinburg in 1918 saw the signed telegraphic instructions to execute the Imperial Family came from Sverdlov. These details were published in 1966.

According to Leon Trotsky

Lev Davidovich Bronstein ( – 21 August 1940), better known as Leon Trotsky,; ; also transliterated ''Lyev'', ''Trotski'', ''Trockij'' and ''Trotzky'' was a Russian revolutionary, Soviet politician, and political theorist. He was a key figure ...

's diaries, after returning from the front (of the Russian Civil War) he had the following dialogue with Sverdlov:

Red Terror and decossackization

Following the assassination of

Following the assassination of Moisei Uritsky

Moisei Solomonovich Uritsky (; ; – 30 August 1918), also known by his pen-name Boretsky () was a Bolshevik revolutionary leader in Russia. After the October Revolution, he was the chief of the Cheka secret police of the Petrograd Soviet. ...

and the assassination attempt

This is a list of survivors of assassination attempts. For successful assassination attempts, see List of assassinations.

Non-heads of state

Heads of state and government

Gallery

File:Arrestation Gregori.jpg, Arrest of Louis Gregori, th ...

on Lenin in August 1918, Sverdlov drafted a document that called for "merciless mass terror against all the enemies of the revolution." Under his and Lenin's leadership, the Central Executive Committee adopted Sverdlov's resolution calling for "mass red terror against the bourgeoisie and its agents." During Lenin's recovery Sverdlov moved into Lenin's office in the Kremlin and took over some of Lenin's official obligations, including chairing the meetings of the Council of People's Commissars

The Council of People's Commissars (CPC) (), commonly known as the ''Sovnarkom'' (), were the highest executive (government), executive authorities of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic (RSFSR), the Soviet Union (USSR), and the Sovi ...

. He oversaw the interrogation of Lenin's would-be assassin, Fanny Kaplan

Fanny Efimovna Kaplan (; real name Feiga Haimovna Roytblat; ; February 10, 1890 – September 3, 1918) was a Russian Socialist-Revolutionary who attempted to assassinate Vladimir Lenin. She was arrested and executed by the Cheka in 1918.

Born i ...

, and even moved Kaplan from the Cheka

The All-Russian Extraordinary Commission ( rus, Всероссийская чрезвычайная комиссия, r=Vserossiyskaya chrezvychaynaya komissiya, p=fsʲɪrɐˈsʲijskəjə tɕrʲɪzvɨˈtɕæjnəjə kɐˈmʲisʲɪjə, links=yes), ...

headquarters

Headquarters (often referred to as HQ) notes the location where most or all of the important functions of an organization are coordinated. The term is used in a wide variety of situations, including private sector corporations, non-profits, mil ...

to be held in a basement room underneath Sverdlov's apartment. Sverdlov's deputy Avanesov gave the order for Kaplan's execution and Sverdlov himself personally ordered that the body be "destroyed without a trace."

Sverdlov supported the Red Terror campaign, specifically when it came to the policy of decossackization

De-Cossackization () was the Bolshevik policy of systematic repression against the Cossacks in the former Russian Empire between 1919 and 1933, especially the Don and Kuban Cossacks in Russia, aimed at the elimination of the Cossacks as a dist ...

that was started in 1917 as a part of the Russian Civil War. This policy resulted in the deaths of thousands of Cossacks, while the Soviet government confiscated land and food produced by the Cossack population. Sverdlov wrote that "not a single crime against the revolutionary military spirit will remain unpunished," and that the release of Cossack prisoners was unacceptable. This policy was temporarily suspended in March 1919 while Sverdlov was in Ukraine

Ukraine is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the List of European countries by area, second-largest country in Europe after Russia, which Russia–Ukraine border, borders it to the east and northeast. Ukraine also borders Belarus to the nor ...

overseeing the election of the Ukrainian Communist Party

The Ukrainian Communist Party () was an oppositional political party in Soviet Ukraine, from 1920 until 1925. Its followers were known as Ukapists (укапісти, ''ukapisty''), from the initials UKP.

USDLP independents

The UKP was an offsho ...

's central committee.

Personality

For the first 16 months after the Bolshevik revolution, Sverdlov was the third most powerful figure in the Soviet regime, after Lenin and Trotsky.Anatoly Lunacharsky

Anatoly Vasilyevich Lunacharsky (, born ''Anatoly Aleksandrovich Antonov''; – 26 December 1933) was a Russian Marxist revolutionary and the first Soviet People's Commissariat for Education, People's Commissar (minister) of Education, as well ...

, the People's Commissar for Education, wrote that Sverdlov (not Stalin) was the effective leader of the Bolshevik party during the July disturbances in 1917, when Lenin was in hiding and Trotsky and others were under arrest. According to Lunacharsky: "His memory contained something like a biographical dictionary of communism. In every aspect of character which had a bearing on their fitness as revolutionaries Sverdlov could judge people with extraordinary accuracy and finesse." According to Trotsky, Lenin assumed that if the two of them were killed, it would fall to Sverdlov and Nikolai Bukharin

Nikolai Ivanovich Bukharin (; rus, Николай Иванович Бухарин, p=nʲɪkɐˈlaj ɪˈvanəvʲɪdʑ bʊˈxarʲɪn; – 15 March 1938) was a Russian revolutionary, Soviet politician, and Marxist theorist. A prominent Bolshevik ...

to take over leadership of the communist party. Though the title did not exist at the time, Sverdlov was the ''de facto'' General Secretary

Secretary is a title often used in organizations to indicate a person having a certain amount of authority, Power (social and political), power, or importance in the organization. Secretaries announce important events and communicate to the org ...

of the Communist Party, the post that Stalin took over three years after Sverdlov's death.

Trotsky wrote that:

Death

There are various theories on how he died and none can be proven officially such as poisoning, beating or flu. He is most commonly attributed to have died of eithertyphus

Typhus, also known as typhus fever, is a group of infectious diseases that include epidemic typhus, scrub typhus, and murine typhus. Common symptoms include fever, headache, and a rash. Typically these begin one to two weeks after exposu ...

or more likely the Spanish flu

The 1918–1920 flu pandemic, also known as the Great Influenza epidemic or by the common misnomer Spanish flu, was an exceptionally deadly global influenza pandemic caused by the H1N1 subtype of the influenza A virus. The earliest docum ...

, after a political visit to Ukraine and Oryol

Oryol ( rus, Орёл, , ɐˈrʲɵl, a=ru-Орёл.ogg, links=y, ), also transliterated as Orel or Oriol, is a Classification of inhabited localities in Russia, city and the administrative center of Oryol Oblast, Russia, situated on the Oka Rive ...

. Kremlin doctors diagnosed him with the Spanish flu. Even as his illness progressed, he continued to perform his duties as chairman of the Central Committee. On 14 March 1919 Sverdlov lost consciousness and on the 16th he died at the age of 33.

He is buried in the Kremlin Wall Necropolis

The Kremlin Wall Necropolis is the former national cemetery of the Soviet Union, located in Red Square in Moscow beside the Moscow Kremlin Wall, Kremlin Wall. Burials there began in November 1917, when 240 pro-Bolsheviks who died during the Mosc ...

in Moscow. Today his grave is one of the twelve individual tombs located between the Lenin Mausoleum and the Kremlin Wall

The Moscow Kremlin Wall is a defensive wall that surrounds the Moscow Kremlin, recognisable by the characteristic notches and its Kremlin towers. The original walls were likely a simple wooden fence with guard towers built in 1156. The Kremlin ...

.

He was succeeded in an interim capacity by Mikhail Vladimirsky

Mikhail Fyodorovich Vladimirsky (; – 2 April 1951) was a Soviet politician and Bolshevik revolutionary who was for a short period of time, the Chairman of the All-Russian Central Executive Committee.

Biography

Mikhail Vladimirsky was bor ...

, and eventually by Mikhail Kalinin

Mikhail Ivanovich Kalinin (, ; 3 June 1946) was a Soviet politician and Russian Old Bolshevik revolutionary who served as the first chairman of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet (head of state) from 1938 until his resignation in 1946. From ...

as Chairman of the Central Executive Committee, and by Elena Stasova

Elena Dmitriyevna Stasova (; 15 October Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.html" ;"title="nowiki/>Old Style and New Style dates">O.S. 3 October1873 – 31 December 1966) was a Russian Soviet people">Soviet revolutionary, Old Bolshevik and an early le ...

as Chairwoman of the Secretariat.

Family

Sverdlov was married to a meteorologist, Klavdia Novgorodtseva (1876–1960), who had joined the Bolsheviks in

Sverdlov was married to a meteorologist, Klavdia Novgorodtseva (1876–1960), who had joined the Bolsheviks in Yekaterinburg

Yekaterinburg (, ; ), alternatively Romanization of Russian, romanized as Ekaterinburg and formerly known as Sverdlovsk ( ; 1924–1991), is a city and the administrative centre of Sverdlovsk Oblast and the Ural Federal District, Russia. The ci ...

, her home town, in 1904, and was arrested for organising an illegal printing press. She and Sverdlov met after her release, and worked together during the 1905 revolution

The Russian Revolution of 1905, also known as the First Russian Revolution, was a revolution in the Russian Empire which began on 22 January 1905 and led to the establishment of a constitutional monarchy under the Russian Constitution of 1906, t ...

. In 1906, she represented the Perm

Perm or PERM may refer to:

Places

* Perm, Russia, a city in Russia

**Permsky District, the district

**Perm Krai, a federal subject of Russia since 2005

**Perm Oblast, a former federal subject of Russia 1938–2005

** Perm Governorate, an administr ...

Bolshevik at the Fourth RSDLP Congress in Stockholm. She was arrested again when she returned to Perm, and spent a year in prison. Released in 1910, she joined Sverdlov in St Petersburg, and was arrested again in 1910, but because of her pregnancy was sent back to Yekaterinburg. When she returned illegally to St Petersburg in 1912, she was arrested, held in a cell with her infant son, and deported to Siberia. In 1915 Klavdia joined Yakov in exile in the village of Monastyrskoe, where together they ran a Bolshevik reading circle in the town, which, though illegal, escaped the notice of the local authorities. After the Bolshevik revolution, she worked with Sverdlov in the party secretariat. From 1920 until she retired in 1946, she worked in education, as a specialist in children's literature.

Sverdlov and Novgorodtseva had had two children: a son Andrei

Andrei, Andrey or Andrej (in Cyrillic script: Андрэй, Андрей or Андреј) is a form of Andreas/Ἀνδρέας in Slavic languages and Romanian. People with the name include:

* Andrei of Polotsk (–1399), Lithuanian nobleman

*An ...

, who joined the NKVD

The People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs (, ), abbreviated as NKVD (; ), was the interior ministry and secret police of the Soviet Union from 1934 to 1946. The agency was formed to succeed the Joint State Political Directorate (OGPU) se ...

and became notorious for persecuting other children of eminent Old Bolsheviks, and daughter Vera, born 1915.

Sverdlov's brother, Venyamin (1886–1939), emigrated to the US to become a banker, returning to Russia in 1917, where he was appointed head of the Road Research Institute. He was arrested on 13 October 1938, accused of belonging to the counter-revolutionary terrorist organisation, and shot on 16 April 1939.

Sverdlov's sister, Sofia (1883–1951), worked as a doctor married a businessman, Leonid Averbakh, and had two children, a son Leopold

Leopold may refer to:

People

* Leopold (given name), including a list of people named Leopold or Léopold

* Leopold (surname)

Fictional characters

* Leopold (''The Simpsons''), Superintendent Chalmers' assistant on ''The Simpsons''

* Leopold B ...

, who was shot in 1937, and a daughter, Ida, who married Genrikh Yagoda

Genrikh Grigoryevich Yagoda (, born Yenokh Gershevich Iyeguda; 7 November 1891 – 15 March 1938) was a Soviet secret police official who served as director of the NKVD, the Soviet Union's security and intelligence agency, from 1934 to 1936. A ...

, the future head of the NKVD

The People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs (, ), abbreviated as NKVD (; ), was the interior ministry and secret police of the Soviet Union from 1934 to 1946. The agency was formed to succeed the Joint State Political Directorate (OGPU) se ...

, and was shot in June 1938. Sofia was arrested in 1937, sentenced to five years exile in Orenburg

Orenburg (, ), formerly known as Chkalov (1938–1957), is the administrative center of Orenburg Oblast, Russia. It lies in Eastern Europe, along the banks of the Ural River, being approximately southeast of Moscow.

Orenburg is close to the ...

, then was arrested again and sentenced to eight years in the gulag

The Gulag was a system of Labor camp, forced labor camps in the Soviet Union. The word ''Gulag'' originally referred only to the division of the Chronology of Soviet secret police agencies, Soviet secret police that was in charge of runnin ...

. She died in a labour camp in Kolyma

Kolyma (, ) or Kolyma Krai () is a historical region in the Russian Far East that includes the basin of Kolyma River and the northern shores of the Sea of Okhotsk, as well as the Kolyma Mountains (the watershed of the two). It is bounded to ...

.

Daniel Swerdlove, the executive producer of the H3 Podcast

The ''H3 Podcast'' is a live commentary podcast hosted by Ethan Klein. The show airs on YouTube and started in 2016.

The ''H3 Podcast'' is among the most listened-to podcasts in the United States. According to the 2023 U.S. Podcast Report by T ...

, is a distant relative of Sverdlov.

Legacy

* In a speech on 18 March 1919 Vladimir Lenin praised Sverdlov and his contributions to the revolution. He called Sverdlov "the most perfectly complete type of professional revolutionary."

* The Central School for Soviet and Party Work, housed in the former Merchants House, Moscow was renamed the

* In a speech on 18 March 1919 Vladimir Lenin praised Sverdlov and his contributions to the revolution. He called Sverdlov "the most perfectly complete type of professional revolutionary."

* The Central School for Soviet and Party Work, housed in the former Merchants House, Moscow was renamed the Sverdlov Communist University

The Sverdlov Communist University (Russian language, Russian: Коммунистический университет имени Я. М. Свердлова) was a school for Soviet activists in Moscow, founded in 1918 as the Central School for Sovi ...

shortly after Sverdlov's death.

* The Imperial Russian Navy

The Imperial Russian Navy () operated as the navy of the Russian Tsardom and later the Russian Empire from 1696 to 1917. Formally established in 1696, it lasted until being dissolved in the wake of the February Revolution and the declaration of ...

destroyer leader (commissioned during 1913) was renamed during 1923.

* The first ship of the s was also named after him.

* Yekaterinburg

Yekaterinburg (, ; ), alternatively Romanization of Russian, romanized as Ekaterinburg and formerly known as Sverdlovsk ( ; 1924–1991), is a city and the administrative centre of Sverdlovsk Oblast and the Ural Federal District, Russia. The ci ...

, dubbed the "third capital of Russia", as it is ranked third by the size of economy, culture, transportation and tourism, was renamed "Sverdlovsk" in 1924 and returned to its former name in 1991.

* In 1938 a number of Ukrainian settlements as well as the Sverdlov mine (part of Sverdlovantratsyt company in 2010s) were merged into the city of Sverdlovsk, which the Ukrainian government renamed Dovzhansk on 12 May 2016, although the renaming could not be enforced due to the Russo-Ukrainian War

The Russo-Ukrainian War began in February 2014 and is ongoing. Following Ukraine's Revolution of Dignity, Russia Russian occupation of Crimea, occupied and Annexation of Crimea by the Russian Federation, annexed Crimea from Ukraine. It then ...

.

* A few locations in the former Soviet Union still bear Sverdlov's name, in the Russian Federation and in Kyrgyzstan

Kyrgyzstan, officially the Kyrgyz Republic, is a landlocked country in Central Asia lying in the Tian Shan and Pamir Mountains, Pamir mountain ranges. Bishkek is the Capital city, capital and List of cities in Kyrgyzstan, largest city. Kyrgyz ...

. Others have been renamed.

See also

* ''Yakov Sverdlov'' (film)Notes

References

Sources

* * * *Slezkine, Yuri (2019). '' The House of Government.'' Princeton University Press.External links

*Leon Trotsky: Jacob Sverdlov – 1925 memorial essay

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Sverdlov, Yakov 1885 births 1919 deaths Politicians from Nizhny Novgorod People from Nizhegorodsky Uyezd Jewish Russian politicians Russian Social Democratic Labour Party members Old Bolsheviks Heads of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union Members of the Orgburo of the 7th Congress of the Russian Communist Party (Bolsheviks) Members of the Secretariat of the 7th Congress of the Russian Communist Party (Bolsheviks) Members of the Bureau of the 7th Congress of the Russian Communist Party (Bolsheviks) Members of the Central Committee of the 6th Conference of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (Bolsheviks) Members of the Central Committee of the 7th Conference of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (Bolsheviks) Members of the Central Committee of the 6th Congress of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (Bolsheviks) Members of the Central Committee of the 7th Congress of the Russian Communist Party (Bolsheviks) People of the Russian Revolution of 1905 Jewish socialists Jewish Soviet politicians Russian communists People of the Russian Revolution People of the Russian Civil War Heads of state of Russia Anti-monarchists Perpetrators of the Red Terror (Russia) Regicides of Nicholas II Russian revolutionaries Deaths from the Spanish flu pandemic Infectious disease deaths in Russia Burials at the Kremlin Wall Necropolis