Sullivan-Clinton Expedition on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The 1779 Sullivan Expedition (also known as the Sullivan-Clinton Expedition, the Sullivan Campaign, and the Sullivan-Clinton Campaign) was a United States military campaign under the command of General John Sullivan during the

On May 30, 1778, a

On May 30, 1778, a

The expedition was one of the largest campaigns of the

The expedition was one of the largest campaigns of the

The fourth brigade, commanded by

The fourth brigade, commanded by

The expedition departed Fort Sullivan on August 26, and cautiously headed up the Chemung River valley. In the early morning of August 29, Sullivan's advance guard discovered a camouflaged, half-mile long breastwork of logs. The breastwork was manned by Butler's Rangers, Brant's Volunteers, a detachment of the 8th Regiment of Foot, and about 350 Seneca, Cayuga and Delaware warriors. Sullivan had Hand's brigade form a line of battle facing the breastwork while Proctor's artillery was positioned on a nearby rise. Poor's New Hampshire Brigade and Clinton's New York Brigade were ordered to circle around to the right and climb the steep hill to the enemy's rear.

Poor and Clinton were given an hour to move into position. When the artillery opened fire the plan was for Hand to feint a frontal attack on the breastwork while Poor and Clinton attacked from behind. Maxwell's brigade was kept in reserve except for the 1st New Jersey which moved to cut off any retreat along the river. The guns, however, opened fire well before Poor and Clinton reached their objective. Their route had taken them through a "morass" that slowed their progress. The British commander, Major John Butler, became aware that his position was in danger of being flanked and began a withdrawal. An attack by a group of Indigenous warriors against the 2nd New Hampshire, which was still struggling to ascend the hill, caused significant casualties and allowed the rest of Butler's forces to escape.

In his report to George Washington, Sullivan reported three dead and 39 wounded. Five of the wounded later succumbed to their injuries bringing the total to eight dead. Butler reported five of his Rangers killed or taken and three wounded as well as five killed and nine wounded among the Iroquois. American sources reported two prisoners taken, and twelve Indigenous dead, including a woman.

The expedition departed Fort Sullivan on August 26, and cautiously headed up the Chemung River valley. In the early morning of August 29, Sullivan's advance guard discovered a camouflaged, half-mile long breastwork of logs. The breastwork was manned by Butler's Rangers, Brant's Volunteers, a detachment of the 8th Regiment of Foot, and about 350 Seneca, Cayuga and Delaware warriors. Sullivan had Hand's brigade form a line of battle facing the breastwork while Proctor's artillery was positioned on a nearby rise. Poor's New Hampshire Brigade and Clinton's New York Brigade were ordered to circle around to the right and climb the steep hill to the enemy's rear.

Poor and Clinton were given an hour to move into position. When the artillery opened fire the plan was for Hand to feint a frontal attack on the breastwork while Poor and Clinton attacked from behind. Maxwell's brigade was kept in reserve except for the 1st New Jersey which moved to cut off any retreat along the river. The guns, however, opened fire well before Poor and Clinton reached their objective. Their route had taken them through a "morass" that slowed their progress. The British commander, Major John Butler, became aware that his position was in danger of being flanked and began a withdrawal. An attack by a group of Indigenous warriors against the 2nd New Hampshire, which was still struggling to ascend the hill, caused significant casualties and allowed the rest of Butler's forces to escape.

In his report to George Washington, Sullivan reported three dead and 39 wounded. Five of the wounded later succumbed to their injuries bringing the total to eight dead. Butler reported five of his Rangers killed or taken and three wounded as well as five killed and nine wounded among the Iroquois. American sources reported two prisoners taken, and twelve Indigenous dead, including a woman.

To celebrate the centennial of the Sullivan expedition, a monument was erected in what is now Newtown Battlefield State Park in 1879. One of the speakers at the dedication ceremony was General

To celebrate the centennial of the Sullivan expedition, a monument was erected in what is now Newtown Battlefield State Park in 1879. One of the speakers at the dedication ceremony was General

Journals of the military expedition of Major General John Sullivan against the Six Nations of Indians in 1779

Sullivan/Clinton Campaign by Robert Spiegelman

{{Authority control 1779 in New York (state) Campaigns of the American Revolutionary War Conflicts in 1779 Iroquois Native American genocide New York (state) in the American Revolution Native American history of New York (state) Native American history of Pennsylvania History of immigration to Canada Province of Quebec (1763–1791) in the American Revolutionary War Forced migrations of Native Americans in the United States Loyalists in the American Revolution from New York (state) Scorched earth operations

American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was the armed conflict that comprised the final eight years of the broader American Revolution, in which Am ...

, lasting from June to October 1779, against the four British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories and Crown Dependencies.

* British national identity, the characteristics of British people and culture ...

-allied nations of the Iroquois

The Iroquois ( ), also known as the Five Nations, and later as the Six Nations from 1722 onwards; alternatively referred to by the Endonym and exonym, endonym Haudenosaunee ( ; ) are an Iroquoian languages, Iroquoian-speaking Confederation#Ind ...

(also known as the Haudenosaunee). The campaign was ordered by George Washington

George Washington (, 1799) was a Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father and the first president of the United States, serving from 1789 to 1797. As commander of the Continental Army, Washington led Patriot (American Revoluti ...

in response to Iroquois and Loyalist attacks on the Wyoming Valley

The Wyoming Valley is a historic industrialized region of Northeastern Pennsylvania. The region is historically notable for its influence in helping fuel the American Industrial Revolution with its many anthracite coal mines. As a metropolitan ar ...

, and Cherry Valley. The campaign had the aim of "the total destruction and devastation of their settlements." Four Continental Army

The Continental Army was the army of the United Colonies representing the Thirteen Colonies and later the United States during the American Revolutionary War. It was formed on June 14, 1775, by a resolution passed by the Second Continental Co ...

brigades carried out a scorched-earth

A scorched-earth policy is a military strategy of destroying everything that allows an enemy military force to be able to fight a war, including the deprivation and destruction of water, food, humans, animals, plants and any kind of tools and i ...

campaign in the territory of the Iroquois Confederacy in what is now central New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

New York may also refer to:

Places United Kingdom

* ...

.

The expedition was largely successful, with 40 Iroquois villages razed and their crops and food stores destroyed. The campaign drove just over 5,000 Iroquois to Fort Niagara

Fort Niagara, also known as Old Fort Niagara, is a fortification originally built by New France to protect its interests in North America, specifically control of access between the Niagara River and Lake Ontario, the easternmost of the Great L ...

seeking British protection, and depopulated the area for post-war settlement. Some scholars argue that it was an attempt to annihilate the Iroquois and describe the campaign as a genocide

Genocide is violence that targets individuals because of their membership of a group and aims at the destruction of a people. Raphael Lemkin, who first coined the term, defined genocide as "the destruction of a nation or of an ethnic group" by ...

although this term is disputed. Today this area is the heartland of Upstate New York

Upstate New York is a geographic region of New York (state), New York that lies north and northwest of the New York metropolitan area, New York City metropolitan area of downstate New York. Upstate includes the middle and upper Hudson Valley, ...

, with thirty-five monoliths marking the path of Sullivan's troops and the locations of the Iroquois villages they razed dotting the region, having been erected by the New York State Education Department in 1929 to commemorate the 150th anniversary of the expedition.

Overview

Led by Major General John Sullivan and Brigadier GeneralJames Clinton

Major general (United States), Major-General James Clinton (August 9, 1736 – September 22, 1812) was a Continental Army officer and politician who fought in the American Revolutionary War.

During the war he, along with John Sullivan (ge ...

, the expedition was conducted during the summer of 1779, beginning on June 18 when the army marched from Easton, Pennsylvania

Easton is a city in and the county seat of Northampton County, Pennsylvania, United States. The city's population was 28,127 as of the 2020 United States census, 2020 census. Easton is located at the confluence of the Lehigh River and the Delawa ...

, to October 3 when it abandoned Fort Sullivan, built at Tioga Tioga may refer to:

United States communities

*Tioga, California, former name of Bennettville, California

*Tioga, Colorado

* Tioga, Florida

* Tioga, Iowa

* Tioga, Louisiana

* Tioga, Michigan

* Tioga, New York, a town in Tioga County

*Tioga County, ...

, to return to George Washington

George Washington (, 1799) was a Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father and the first president of the United States, serving from 1789 to 1797. As commander of the Continental Army, Washington led Patriot (American Revoluti ...

's main camp in New Jersey. While the campaign had only one major battle at Newtown on the Chemung River

The Chemung River ( ) is a tributary of the Susquehanna River, approximately long,U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map, accessed August 8, 2011 in south central New York and northern ...

in western New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

New York may also refer to:

Places United Kingdom

* ...

, the expedition severely damaged the Iroquois nations' economies by destroying their crops, villages, and chattels. The death toll from exposure, starvation and disease the following winter dwarfed the casualties received in the Battle of Newtown, during which Sullivan's army of 3,200 Continental soldiers decisively defeated about 600 Iroquois and Loyalists.

In response to 1778 attacks by Iroquois and Loyalists on American settlements, such as on Cobleskill, German Flatts

German Flatts is a town in Herkimer County, New York, United States. The population was 12,263 at the 2020 census down from 13,258 at the 2010 census.

The town is in the southern part of Herkimer County, on the south side of the Mohawk River, a ...

, the Wyoming Valley and Cherry Valley, as well as Iroquois support of the British during the 1777 Battles of Saratoga

The Battles of Saratoga (September 19 and October 7, 1777) were two battles between the American Continental Army and the British Army fought near Saratoga, New York, concluding the Saratoga campaign in the American Revolutionary War. The seco ...

, Sullivan's army carried out a scorched-earth

A scorched-earth policy is a military strategy of destroying everything that allows an enemy military force to be able to fight a war, including the deprivation and destruction of water, food, humans, animals, plants and any kind of tools and i ...

campaign to put an end to Iroquois attacks. The American force methodically destroyed 40 Iroquois villages throughout the Finger Lakes

The Finger Lakes are a group of eleven long, narrow, roughly north–south lakes located directly south of Lake Ontario in an area called the ''Finger Lakes region'' in New York (state), New York, in the United States. This region straddles th ...

region of western New York. Thousands of Indigenous refugees fled to Fort Niagara on Lake Ontario

Lake Ontario is one of the five Great Lakes of North America. It is bounded on the north, west, and southwest by the Canadian province of Ontario, and on the south and east by the U.S. state of New York (state), New York. The Canada–United Sta ...

at the mouth of the Niagara River

The Niagara River ( ) flows north from Lake Erie to Lake Ontario, forming part of the border between Ontario, Canada, to the west, and New York, United States, to the east. The origin of the river's name is debated. Iroquoian scholar Bruce T ...

. The devastation created great hardship for those who sheltered under British military protection outside Fort Niagara that winter, and many starved or froze to death, despite efforts by the British authorities to supply food and provide shelter using their limited resources.

Background

When the Revolutionary War began, British officials, as well as the colonialContinental Congress

The Continental Congress was a series of legislature, legislative bodies, with some executive function, for the Thirteen Colonies of British America, Great Britain in North America, and the newly declared United States before, during, and after ...

, sought the allegiance (or at least the neutrality) of the Iroquois, Iroquois Confederacy, also known as the Six Nations. The Iroquois eventually divided over what course to pursue. Most Senecas

The Seneca ( ; ) are a group of Indigenous Iroquoian-speaking people who historically lived south of Lake Ontario, one of the five Great Lakes in North America. Their nation was the farthest to the west within the Six Nations or Iroquois Leag ...

, Cayugas

The Cayuga (Cayuga: Gayogo̱hó꞉nǫʼ, "People of the Great Swamp") are one of the five original constituents of the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois), a confederacy of Native Americans in New York. The Cayuga homeland lies in the Finger Lakes region ...

, Onondagas

The Onondaga people (Onontaerrhonon, Onondaga: , "People of the Hills") are one of the five original nations of the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) Confederacy in the Northeastern Woodlands. Their historical homelands are in and around present-day Ono ...

, and Mohawks

The Mohawk, also known by their own name, (), are an Indigenous people of North America and the easternmost nation of the Haudenosaunee, or Iroquois Confederacy (also known as the Five Nations or later the Six Nations).

Mohawk are an Iroquoi ...

chose to ally themselves with the British. Most Oneidas

The Oneida people ( ; autonym: Onʌyoteˀa·ká·, Onyota'a:ka, ''the People of the Upright Stone, or standing stone'', ''Thwahrù·nęʼ'' in Tuscarora) are a Native American tribe and First Nations band. They are one of the five founding nati ...

and Tuscaroras

The Tuscarora (in Tuscarora ''Skarù:ręˀ'') are an indigenous people of the Northeastern Woodlands in Canada and the United States. They are an Iroquoian Native American and First Nations people. The Tuscarora Nation, a federally recognize ...

joined the American revolutionaries, thanks in part to the influence of Presbyterian

Presbyterianism is a historically Reformed Protestant tradition named for its form of church government by representative assemblies of elders, known as "presbyters". Though other Reformed churches are structurally similar, the word ''Pr ...

missionary Samuel Kirkland

Samuel Kirkland (December 1, 1741 – February 28, 1808) was a Presbyterian minister and missionary among the Oneida and Tuscarora peoples of central New York State. He was a long-time friend of the Oneida chief Skenandoa.

Kirkland graduated ...

. For the Iroquois, the American Revolution

The American Revolution (1765–1783) was a colonial rebellion and war of independence in which the Thirteen Colonies broke from British America, British rule to form the United States of America. The revolution culminated in the American ...

became a civil war

A civil war is a war between organized groups within the same Sovereign state, state (or country). The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies.J ...

.

The Iroquois homeland lay on the frontier between the Province of Quebec

Quebec is Canada's largest province by area. Located in Central Canada, the province shares borders with the provinces of Ontario to the west, Newfoundland and Labrador to the northeast, New Brunswick to the southeast and a coastal border ...

and the provinces of New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

New York may also refer to:

Places United Kingdom

* ...

and Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania, officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a U.S. state, state spanning the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern United States, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes region, Great Lakes regions o ...

. Following the October 1777 surrender of British General John Burgoyne's forces after the Battles of Saratoga

The Battles of Saratoga (September 19 and October 7, 1777) were two battles between the American Continental Army and the British Army fought near Saratoga, New York, concluding the Saratoga campaign in the American Revolutionary War. The seco ...

, Loyalists and their Iroquois allies began raiding American frontier settlements, as well as the villages of the Oneida. Working out of Fort Niagara

Fort Niagara, also known as Old Fort Niagara, is a fortification originally built by New France to protect its interests in North America, specifically control of access between the Niagara River and Lake Ontario, the easternmost of the Great L ...

, men such as Loyalist commander Major John Butler, Mohawk military leader Joseph Brant

Thayendanegea or Joseph Brant (March 1743 – November 24, 1807) was a Mohawk military and political leader, based in present-day New York and, later, Brantford, in what is today Ontario, who was closely associated with Great Britain du ...

, and Seneca war chiefs Sayenqueraghta

Sayenqueraghta (1786) was the war chief of the eastern Seneca tribe in the mid-18th century. He was born the son of Cayenquaraghta, a prominent Seneca chief of the Turtle clan in western New York. He lived most of his life at Kanadaseaga, near the ...

and Cornplanter

John Abeel III (–February 18, 1836) known as Gaiänt'wakê (''Gyantwachia'' – "the planter") or Kaiiontwa'kon (''Kaintwakon'' – "By What One Plants") in the Seneca language and thus generally known as Cornplanter, was a Dutch- Seneca ch ...

led the joint British-Indigenous raids.

On May 30, 1778, a

On May 30, 1778, a raid

RAID (; redundant array of inexpensive disks or redundant array of independent disks) is a data storage virtualization technology that combines multiple physical Computer data storage, data storage components into one or more logical units for th ...

on Cobleskill by Brant's Volunteers

Brant's Volunteers, also known as Joseph Brant's Volunteers, were an irregular unit of Loyalist and Indigenous volunteers raised during the American Revolutionary War by Mohawk war leader, Joseph Brant (Mohawk: ''Thayendanegea''). Brant's Volunt ...

resulted in the deaths of 22 regulars and militia. On June 10, 1778, the Board of War of the Continental Congress

The Continental Congress was a series of legislature, legislative bodies, with some executive function, for the Thirteen Colonies of British America, Great Britain in North America, and the newly declared United States before, during, and after ...

concluded that a major Indian war was in the offing. Since a defensive war would prove inadequate, the board called for an expedition of 3,000 men against Fort Detroit

A fortification (also called a fort, fortress, fastness, or stronghold) is a military construction designed for the defense of territories in warfare, and is used to establish rule in a region during peacetime. The term is derived from Lati ...

and a similar thrust into Seneca country to punish the Iroquois. Congress designated Major General Horatio Gates

Horatio Lloyd Gates (July 26, 1727April 10, 1806) was a British-born American army officer who served as a general in the Continental Army during the early years of the American Revolutionary War, Revolutionary War. He took credit for the Ameri ...

to lead the expedition and appropriated funds for the campaign. Despite these efforts, the campaign did not occur until the following year.

On July 3, 1778, Butler, Sayenqueraghta and Cornplanter led a mixed force of Indigenous warriors and Rangers

A ranger is typically someone in a law enforcement or military/paramilitary role specializing in patrolling a given territory, called "ranging" or "scouting". The term most often refers to:

* Park ranger or forest ranger, a person charged with prot ...

in an attack on the Wyoming Valley

The Wyoming Valley is a historic industrialized region of Northeastern Pennsylvania. The region is historically notable for its influence in helping fuel the American Industrial Revolution with its many anthracite coal mines. As a metropolitan ar ...

, a rebel granary and settlement along the north branch of the Susquehanna River

The Susquehanna River ( ; Unami language, Lenape: ) is a major river located in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic region of the United States, crossing three lower Northeastern United States, Northeast states (New York, Pennsylvani ...

in what is now Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania, officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a U.S. state, state spanning the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern United States, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes region, Great Lakes regions o ...

. Roughly 300 of the armed Patriot defenders were killed at the Battle of Wyoming

The Battle of Wyoming, also known as the Wyoming Massacre, was a military engagement during the American Revolutionary War between Patriot militia and a force of Loyalist soldiers and Iroquois warriors. The battle took place in the Wyoming Val ...

, after which houses, barns, and mills were razed throughout the valley.

In September 1778, a response to the Wyoming defeat was undertaken by Colonel Thomas Hartley

Thomas Hartley (September 7, 1748December 21, 1800) was an American lawyer, soldier, and politician from York, Pennsylvania.

Early life and education

Hartley was born in Colebrookdale Township in the Province of Pennsylvania. At 18 years of a ...

who destroyed a number of abandoned Delaware

Delaware ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic and South Atlantic states, South Atlantic regions of the United States. It borders Maryland to its south and west, Pennsylvania to its north, New Jersey ...

and Seneca villages along the Susquehanna River, including Tioga Tioga may refer to:

United States communities

*Tioga, California, former name of Bennettville, California

*Tioga, Colorado

* Tioga, Florida

* Tioga, Iowa

* Tioga, Louisiana

* Tioga, Michigan

* Tioga, New York, a town in Tioga County

*Tioga County, ...

. At the same time, Joseph Brant

Thayendanegea or Joseph Brant (March 1743 – November 24, 1807) was a Mohawk military and political leader, based in present-day New York and, later, Brantford, in what is today Ontario, who was closely associated with Great Britain du ...

led an attack on German Flatts in the Mohawk Valley

The Mohawk Valley region of the U.S. state of New York is the area surrounding the Mohawk River, sandwiched between the Adirondack Mountains and Catskill Mountains, northwest of the Capital District. As of the 2010 United States Census, ...

, destroying numerous houses, barns and mills. In October, further American retaliation was taken by Continental Army units under Lieutenant Colonel William Butler who destroyed

Destroyed may refer to:

* ''Destroyed'' (Sloppy Seconds album), a 1989 album by Sloppy Seconds

* ''Destroyed'' (Moby album), a 2011 album by Moby

See also

* Destruction (disambiguation)

* Ruined (disambiguation)

Ruins are the remains of man-m ...

the substantial Indigenous villages at Unadilla and Onaquaga

Onaquaga (also spelled many other ways) was a large Iroquois village, located on both sides of the Susquehanna River near present-day Windsor, New York. During the American Revolutionary War, the Continental Army destroyed it and nearby Unadi ...

on the Susquehanna River.

On November 11, 1778, Loyalist Captain Walter Butler (the son of John Butler) led two companies of Butler's Rangers, a detachment of the 8th Regiment of Foot

Eighth is ordinal form of the number eight.

Eighth may refer to:

* One eighth, , a fraction, one of eight equal parts of a whole

* Eighth note (quaver), a musical note played for half the value of a quarter note (crotchet)

* Octave, an interval b ...

, about 300 Seneca and Cayuga led by Cornplanter

John Abeel III (–February 18, 1836) known as Gaiänt'wakê (''Gyantwachia'' – "the planter") or Kaiiontwa'kon (''Kaintwakon'' – "By What One Plants") in the Seneca language and thus generally known as Cornplanter, was a Dutch- Seneca ch ...

, and a small group of Mohawks led by Joseph Brant

Thayendanegea or Joseph Brant (March 1743 – November 24, 1807) was a Mohawk military and political leader, based in present-day New York and, later, Brantford, in what is today Ontario, who was closely associated with Great Britain du ...

, on an assault at Cherry Valley in New York. While the rangers and regulars blockaded Fort Alden, the Seneca rampaged through the village, killing and scalping 16 soldiers and 32 civilians, mostly women and children, and taking 80 captives. In less than a year, Butler's Rangers and their Iroquois allies had reduced much of upstate New York and northeastern Pennsylvania to ruins, causing thousands of settlers to flee and depriving the Continental Army of food.

The Cherry Valley massacre

The Cherry Valley massacre was an attack by British and Iroquois forces on a fort and the town of Cherry Valley in central New York on November 11, 1778, during the American Revolutionary War. It has been described as one of the most horrific f ...

convinced the Americans that they needed to take action. In April 1779, Colonel Goose Van Schaick led an expedition of 558 Continental Army troops against the Onondaga people

The Onondaga people (Onontaerrhonon, Onondaga language, Onondaga: , "People of the Hills") are one of the five original nations of the Iroquois, Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) Confederacy in the Northeastern Woodlands. Their historical homelands are in ...

. About 50 houses and a large quantity of corn and beans were burned. Van Schaick reported that they took "thirty three Indians and one white man prisoner, and killed twelve Indians." Despite Van Schaick's superior James Clinton

Major general (United States), Major-General James Clinton (August 9, 1736 – September 22, 1812) was a Continental Army officer and politician who fought in the American Revolutionary War.

During the war he, along with John Sullivan (ge ...

ordering him to prevent his soldiers from assaulting any Onondaga women (noting that "Bad as the savages are, they never violate the chastity of any women"), the Americans committed numerous atrocities during the expedition. American soldiers "killed babies and raped women", and an Onondaga chief recounted to the British in 1782 how the Americans "put to death all the Women and Children, excepting some of the Young Women, whom they carried away for the use of their Soldiers & were afterwards put to death in a more shameful manner".

When the British began to concentrate their military efforts on the southern colonies in 1779, Washington used the opportunity to launch a major offensive against the British-allied Iroquois. His initial impulse was to assign the expedition to Major General Charles Lee, however, Lee as well as Major General Philip Schuyler

Philip John Schuyler (; November 20, 1733 - November 18, 1804) was an American general in the American Revolutionary War, Revolutionary War and a United States Senate, United States Senator from New York (state), New York. He is usually known as ...

and Major General Israel Putnam

Israel Putnam (January 7, 1718 – May 29, 1790), popularly known as "Old Put", was an American military officer and landowner who fought with distinction at the Battle of Bunker Hill during the American Revolutionary War (1775–1783). He als ...

were all disregarded for various reasons. Washington offered command of the expedition to Horatio Gates

Horatio Lloyd Gates (July 26, 1727April 10, 1806) was a British-born American army officer who served as a general in the Continental Army during the early years of the American Revolutionary War, Revolutionary War. He took credit for the Ameri ...

, the "Hero of Saratoga," but Gates turned down the offer, ostensibly for health reasons. Finally, Major General John Sullivan accepted command.

Washington's issued his specific orders in a letter to Sullivan on May 31, 1779:

Expedition

The expedition was one of the largest campaigns of the

The expedition was one of the largest campaigns of the Continental Army

The Continental Army was the army of the United Colonies representing the Thirteen Colonies and later the United States during the American Revolutionary War. It was formed on June 14, 1775, by a resolution passed by the Second Continental Co ...

, involving more than one third of its soldiers. Sullivan was assigned four Continental Army brigades totalling 4,469 men. By the time the expedition set out this number had fallen to just under 4,000 due to disease, desertions and expired enlistments.

In April 1779, Edward Hand's brigade was ordered from Minisink

The Minisink or (more recently) Minisink Valley is a loosely defined geographic region of the Upper Delaware River valley in northwestern New Jersey (Sussex and Warren counties), northeastern Pennsylvania ( Pike and Monroe counties) and New York ...

to the Wyoming Valley to establish a base camp for the expedition. In May 1779, the brigades of Enoch Poor

Enoch Poor (June 21, 1736 (Old Style) – September 8, 1780) was a brigadier general in the Continental Army during the American Revolutionary War. He was a ship builder and merchant from Exeter, New Hampshire.

Biography

Poor was born and raised ...

and William Maxwell assembled at Easton where they were joined by Sullivan and Thomas Proctor's 4th Artillery Regiment. Before they could proceed to Wyoming a road had to be hewn through the wilderness between the Delaware

Delaware ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic and South Atlantic states, South Atlantic regions of the United States. It borders Maryland to its south and west, Pennsylvania to its north, New Jersey ...

and Susquehanna rivers. The road was completed in mid-June and Sullivan's forces arrived at Wyoming on June 23 after a five-day march. A number of smaller units, including three companies of Morgan's Riflemen

Morgan's Riflemen or Morgan's Rifles, previously Morgan's Sharpshooters, and the one named Provisional Rifle Corps, were an elite light infantry unit commanded by General Daniel Morgan in the American Revolutionary War, which served a vital role e ...

, joined the expedition at Wyoming.

Supply shortages delayed Sullivan's departure from Wyoming until July 31 when the expedition set out for Tioga at the confluence of the Chemung and Susquehanna rivers. The expedition proceeded cautiously, slowed by the mountainous terrain and the need to keep abreast of the 134 flatboats

A flatboat (or broadhorn) was a rectangular flat-bottomed boat with square ends used to transport freight and passengers on inland waterways in the United States. The flatboat could be any size, but essentially it was a large, sturdy tub with a ...

carrying Sullivan's artillery and supplies up the Susquehanna. With the expedition were 1,200 pack horses, 700 head of cattle, four brass three-pound cannons, two six-pound cannons, two 5½-inch howitzers

The howitzer () is an artillery weapon that falls between a cannon (or field gun) and a mortar. It is capable of both low angle fire like a field gun and high angle fire like a mortar, given the distinction between low and high angle fire break ...

, and one coehorn

A Coehorn (also spelled ''cohorn'') is a lightweight mortar originally designed by Dutch military engineer Menno van Coehoorn.

Concept and design

Van Coehoorn came to prominence during the 1688–1697 Nine Years War, whose tactics have been s ...

. The expedition arrived at Tioga on August 11 and construction began on a temporary fort that was named Fort Sullivan.

Battle of Chemung

After arriving at Tioga, Sullivan dispatched a small party to reconnoitre Chemung, aDelaware

Delaware ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic and South Atlantic states, South Atlantic regions of the United States. It borders Maryland to its south and west, Pennsylvania to its north, New Jersey ...

village upstream, where he believed Indigenous and Loyalist forces were gathering. When the scouts returned they reported the presence of a large number of "both white people and Indians" in "great confusion" but were unable to tell if the enemy were preparing to fight or depart. Sullivan decided an immediate attack was warranted. Leaving behind a garrison of 250 at Tioga, Sullivan's forces marched overnight and arrived at Chemung at dawn on August 13. They discovered that the village had been hastily abandoned. While Poor's soldiers torched the village and destroyed the crops in the surrounding fields, Hand's brigade searched for traces of the escaped villagers. About a mile west of the village, a detachment of the 11th Pennsylvania Regiment

The 11th Pennsylvania Regiment or Old Eleventh was authorized on 16 September 1776 for service with the Continental Army. On 25 October, Richard Humpton was named colonel. In December 1776, the regiment was assigned to George Washington's main ...

was ambushed by 30 Delaware led by Roland Montour. The Continentals were able to counterattack and force the Delaware to retreat but suffered six killed and 12 wounded. Later a detachment of the 1st New Hampshire Regiment

The 1st New Hampshire Regiment was an infantry unit that came into existence on 22 May 1775 at the beginning of the American Revolutionary War. John Stark was the regiment's first commander. The unit fought at Chelsea Creek and Bunker Hill in ...

was fired upon while destroying crops on the opposite side of the river, killing one and wounding four. Sullivan's forces withdrew from Chemung that afternoon and returned to the encampment at Tioga after nightfall.

Clinton's brigade

The fourth brigade, commanded by

The fourth brigade, commanded by James Clinton

Major general (United States), Major-General James Clinton (August 9, 1736 – September 22, 1812) was a Continental Army officer and politician who fought in the American Revolutionary War.

During the war he, along with John Sullivan (ge ...

, assembled at Canojaharie on the Mohawk River

The Mohawk River is a U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map accessed October 3, 2011 river in the U.S. state of New York (state), New York. It is the largest tributary of the Hudson R ...

. A road was cut through the forest from the Mohawk River to Otsego Lake, the source of the Susquehanna River. For six days in June, wagons trundled back and forth carrying supplies and 208 flatboats to the head of the lake. The supplies were then loaded onto the boats and ferried across. Clinton established his headquarters at the south end of the lake in early July and waited for Sullivan's order to march.

Clinton received the order to start for Tioga on August 9. Due to low water levels on the Susquehanna, Clinton had ordered the construction of a dam that had raised the water level on Otsego Lake by . The boats, laden with supplies, were hauled to the shallows below the dam. The dam was breached and the boats were able to float downriver, paced by Clinton's soldiers marching along both banks.

Clinton reached Unadilla on August 12, and Oquaga two days later. Both villages had been destroyed by William Butler a year earlier. After a two-day rest, Clinton's brigade continued downriver, burning abandoned hamlets and scattered farms. On August 19, they reached the mouth of Choconut Creek where a large detachment from Poor's and Hand's brigades was waiting to escort them to Tioga. Clinton entered Sullivan's camp on August 22.

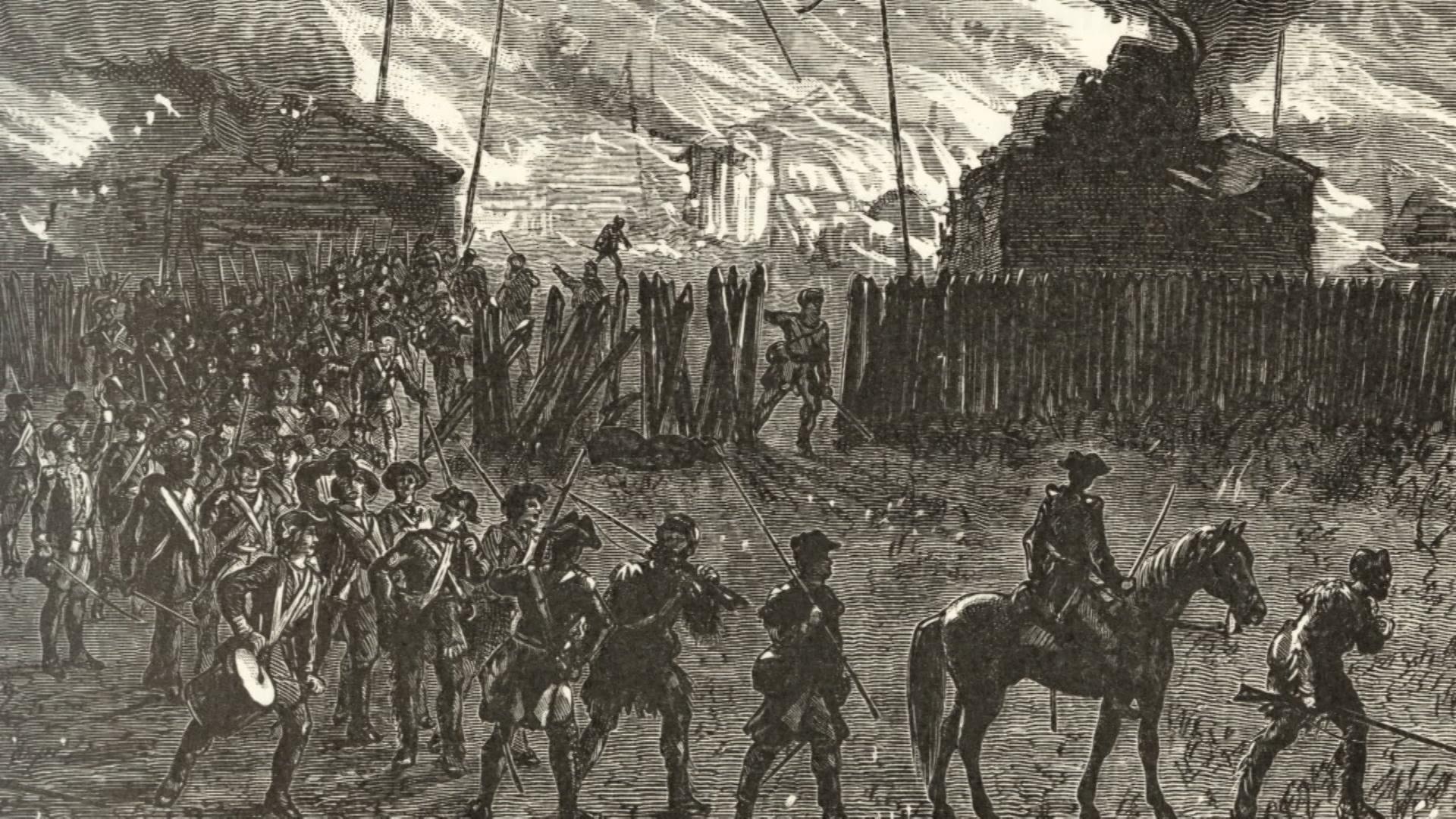

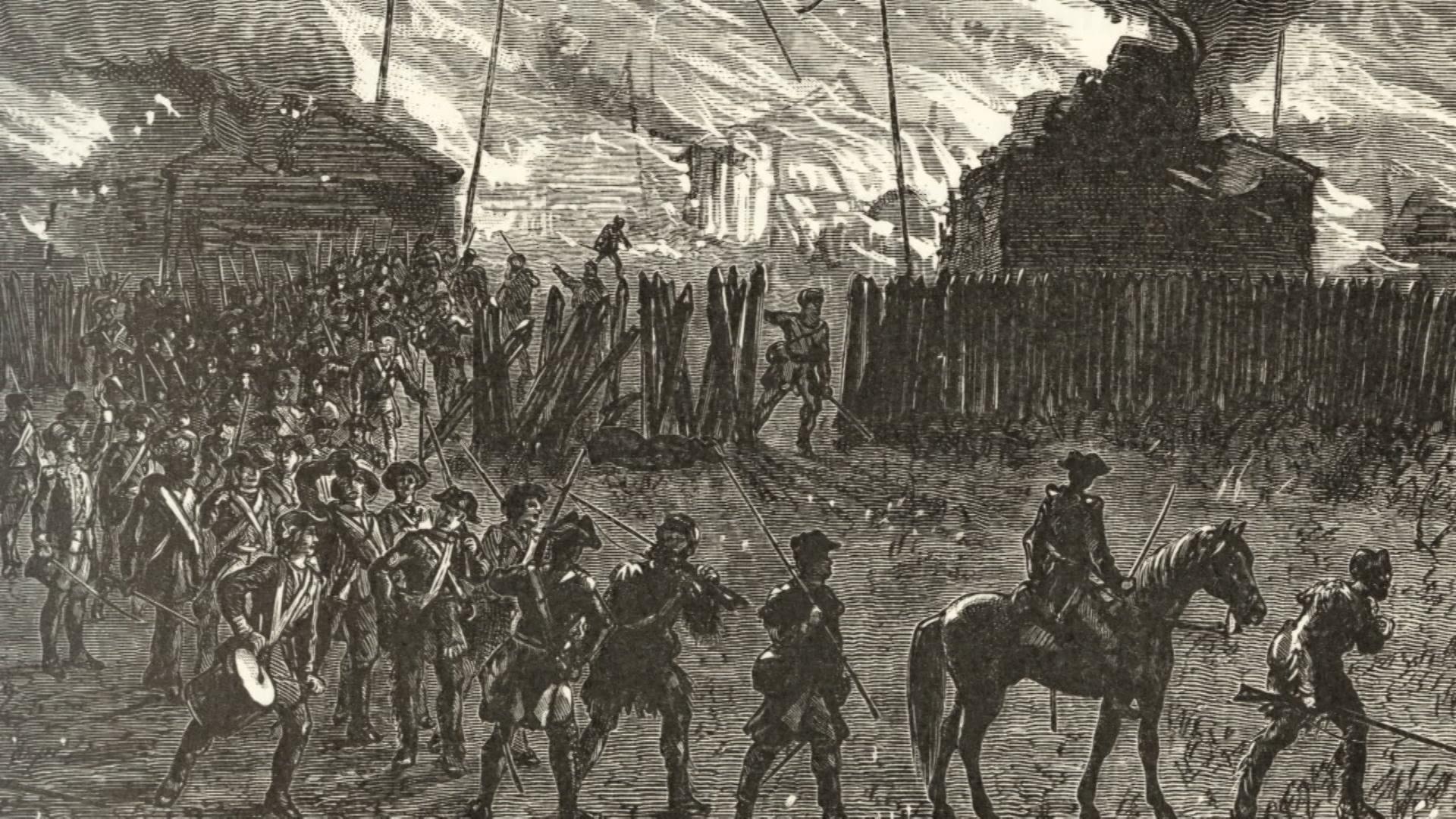

Battle of Newtown

The expedition departed Fort Sullivan on August 26, and cautiously headed up the Chemung River valley. In the early morning of August 29, Sullivan's advance guard discovered a camouflaged, half-mile long breastwork of logs. The breastwork was manned by Butler's Rangers, Brant's Volunteers, a detachment of the 8th Regiment of Foot, and about 350 Seneca, Cayuga and Delaware warriors. Sullivan had Hand's brigade form a line of battle facing the breastwork while Proctor's artillery was positioned on a nearby rise. Poor's New Hampshire Brigade and Clinton's New York Brigade were ordered to circle around to the right and climb the steep hill to the enemy's rear.

Poor and Clinton were given an hour to move into position. When the artillery opened fire the plan was for Hand to feint a frontal attack on the breastwork while Poor and Clinton attacked from behind. Maxwell's brigade was kept in reserve except for the 1st New Jersey which moved to cut off any retreat along the river. The guns, however, opened fire well before Poor and Clinton reached their objective. Their route had taken them through a "morass" that slowed their progress. The British commander, Major John Butler, became aware that his position was in danger of being flanked and began a withdrawal. An attack by a group of Indigenous warriors against the 2nd New Hampshire, which was still struggling to ascend the hill, caused significant casualties and allowed the rest of Butler's forces to escape.

In his report to George Washington, Sullivan reported three dead and 39 wounded. Five of the wounded later succumbed to their injuries bringing the total to eight dead. Butler reported five of his Rangers killed or taken and three wounded as well as five killed and nine wounded among the Iroquois. American sources reported two prisoners taken, and twelve Indigenous dead, including a woman.

The expedition departed Fort Sullivan on August 26, and cautiously headed up the Chemung River valley. In the early morning of August 29, Sullivan's advance guard discovered a camouflaged, half-mile long breastwork of logs. The breastwork was manned by Butler's Rangers, Brant's Volunteers, a detachment of the 8th Regiment of Foot, and about 350 Seneca, Cayuga and Delaware warriors. Sullivan had Hand's brigade form a line of battle facing the breastwork while Proctor's artillery was positioned on a nearby rise. Poor's New Hampshire Brigade and Clinton's New York Brigade were ordered to circle around to the right and climb the steep hill to the enemy's rear.

Poor and Clinton were given an hour to move into position. When the artillery opened fire the plan was for Hand to feint a frontal attack on the breastwork while Poor and Clinton attacked from behind. Maxwell's brigade was kept in reserve except for the 1st New Jersey which moved to cut off any retreat along the river. The guns, however, opened fire well before Poor and Clinton reached their objective. Their route had taken them through a "morass" that slowed their progress. The British commander, Major John Butler, became aware that his position was in danger of being flanked and began a withdrawal. An attack by a group of Indigenous warriors against the 2nd New Hampshire, which was still struggling to ascend the hill, caused significant casualties and allowed the rest of Butler's forces to escape.

In his report to George Washington, Sullivan reported three dead and 39 wounded. Five of the wounded later succumbed to their injuries bringing the total to eight dead. Butler reported five of his Rangers killed or taken and three wounded as well as five killed and nine wounded among the Iroquois. American sources reported two prisoners taken, and twelve Indigenous dead, including a woman.

Boyd and Parker ambush

Sullivan's force destroyed Newtown and several other abandoned Delaware villages along the Chemung River, then turned north towards Seneca Lake. After burning Queanettquaga (Catherine's Town), the home ofCatherine Montour

Catharine Montour, also known as Queen Catharine (died after 1791), was a prominent Iroquois leader living in ''Queanettquaga,'' a Seneca village of ''Sheaquaga'', informally called Catharine's Town, in western New York. She has often been confuse ...

, the expedition headed up the east side of the lake and then west to Kanadaseaga

Kanadaseaga (aka Kanadesaga or Kanatasaka or Kanadasaga or Canasadego or Ganûndase?'ge? or Seneca Castle or Canadasaga), was a major village, perhaps a capital, of the Seneca nation of the Iroquois Confederacy in west-central New York State, Uni ...

, setting every structure on fire, destroying food stores and the crops in the fields, cutting down orchards, and fulfilling Washington's directive to cause "the total destruction and devastation of their settlements."

Following the destruction of Kanadaseaga, Sullivan's forces continued west towards the Genesee River

The Genesee River ( ) is a tributary of Lake Ontario flowing northward through the Twin Tiers of Pennsylvania and New York (state), New York in the United States. The river contains several waterfalls in New York at Letchworth State Park and Roch ...

and Chenussio, also known as Little Beard's Town. On September 12, after marching from Honeoye Lake

Honeoye Lake ( ) is one of the Finger Lakes located in Ontario County, New York, Ontario County, New York (state), New York. Most of the lake is within the town of Richmond, New York, Richmond but a smaller southwestern part is in the town of C ...

, Sullivan's forces camped between Hemlock Lake

Hemlock Lake is one of the minor Finger Lakes. It is mostly located in Livingston County, New York, south of Rochester, New York, Rochester, with a portion overlapping into Ontario County, New York, Ontario County. Hemlock is a translation of t ...

and Conesus Lake

Conesus Lake is located in Livingston County, New York. Conesus Lake is one of New York's twelve Finger Lakes. It is located off Interstate 390 about south of Interstate 90.

Description

Conesus Lake is long, with a maximum depth of . I ...

. From there Sullivan dispatched Lieutenant Thomas Boyd of Morgan's Rifle Corps to reconnoiter Chenussio. Boyd took with him 26 riflemen including Sergeant Michael Parker, and Thaosagwat, an Oneida guide also known as Han Yost. The following morning Boyd's patrol reached an abandoned village which he believed was Chenussio. Meanwhile, about 200 Butler's Rangers led by John Butler and Seneca warriors led by Cornplanter and Little Beard, were preparing to ambush the vanguard of Sullivan's army as it emerged from the marshy area south of Conesus Lake, unaware that Boyd's patrol had unknowingly passed them in the night.

As Boyd's patrol kept watch for signs of enemy activity, four Seneca on horseback entered the village. One was killed but three escaped. Afraid that the gunfire would draw more of the enemy to the village, Boyd ordered a return to Sullivan's position. On the trail they spotted several more Seneca who fled. Thaosagwat warned Boyd not to give chase but the warning was ignored, and the patrol stumbled into the ambush. Surrounded and outnumbered, fourteen of Boyd's men were killed while Boyd, Parker and Thaosagwat were captured. Thaosagwat was immediately executed by Little Beard while Boyd and Parker were later tortured to death. The mutilated bodies of Boyd and Parker were discovered when Sullivan's forces entered Chenussio on September 14.

Return to Tioga

After destroying Chenussio's 128 houses with its gardens and cornfields, Sullivan retraced his steps, aware that provisions were growing short, and mistakenly believing there were no other Seneca villages west of the Genesee River. At the north end of Seneca Lake he met with a delegation of Oneida that brought a message from the Cayuga claiming neutrality. Ignoring their plea, Sullivan ordered William Butler with 600 men to cross over toCayuga Lake

Cayuga Lake (, or ) is the longest of central New York's glacial Finger Lakes, and is the second largest in surface area (marginally smaller than Seneca Lake) and second largest in volume. It is just under long. Its average width is , and i ...

and lay waste to the Cayuga villages on the eastern shore. Henry Dearborn and the 3rd New Hampshire were tasked with destroying the villages on the western shore of the lake while William Smith and the 5th New Jersey would burn any villages on the western shore of Seneca Lake.

Over the next five days, Bulter's and Dearborn's men leveled the two large Cayuga villages of Goiogouen

Goiogouen (also spelled Gayagaanhe and known as Cayuga Castle), was a major village of the Cayuga nation of Iroquois Indians in west-central New York State. It was located on the eastern shore of Cayuga Lake on the north side of the Great Gully ...

and Chonodote

Chonodote was an 18th-century village of the Cayuga nation of Iroquois Indians in what is now upstate New York, US. It was located about four and a half miles south of Goiogouen, on the east side of Cayuga Lake. Earlier, during the 17th centur ...

, as well as smaller villages and hamlets. Coreorgonel

Coreorgonel was an 18th-century Native American village in what is now Tompkins County, New York. The name has been translated as "Where we keep the pipe of peace."

In the mid 18th century, a group of Tutelo, a Siouan-speaking people, migrated no ...

, a village of Tutelo

The Tutelo (also Totero, Totteroy, Tutera; Yesan in Tutelo) were Native American people living above the Fall Line in present-day Virginia and West Virginia. They spoke a dialect of the Siouan Tutelo language thought to be similar to that of th ...

who had been adopted by the Cayuga, was also destroyed.

Exhausted from carrying the expedition's supplies, many of Sullivan's pack horses reached the end of their endurance on the return to Tioga. Just north of what is now Elmira, New York

Elmira () is a Administrative divisions of New York#City, city in and the county seat of Chemung County, New York, United States. It is the principal city of the Elmira, New York, metropolitan statistical area, which encompasses Chemung County. ...

, Sullivan ordered most of them euthanized. A few years later, the skulls of these horses were lined along the trail as a warning to potential settlers. The area became known as "The Valley of Horses Heads" and is now known as the town and village of Horseheads.

Sullivan, with the main body of his forces, returned to the Chemung River on September 24 and waited for Dearborn and Butler to arrive. Dearborn's detachment reached Sullivan's camp two days later while Butler's did not arrive until September 28. Sullivan's army returned to Tioga on September 30. Fort Sullivan was demolished on October 3, and the following day Sullivan's army boarded the flatboats for a three-day journey down the Susquehanna to Wyoming. Two days after arriving at Wyoming, Sullivan received orders to bring his army to West Point.

Overall, 40 villages, numerous isolated houses and 160,000 bushels of corn, as well as orchards and a vast quantity of vegetables were destroyed. Including deaths from illness, only 40 men had been lost.

Brodhead's expedition

Further to the west, a concurrent expedition was undertaken by ColonelDaniel Brodhead

Brigadier General Daniel Brodhead (October 17, 1736 – November 15, 1809) was an Continental Army officer and politician who served in the American Revolutionary War.

Early life

Brodhead was born in Marbletown, Province of New York, the so ...

. Brodhead, who had been given command of the Western Department in March 1779, was a strong advocate of launching an offensive against the western Seneca. Washington's strategy for the "chastisement of the savages" initially included an operation from Fort Pitt, but in April 1779, he had ordered the expedition cancelled due to supply issues. Brodhead, however, indicated that he had sufficient men and provisions to mount an attack, and on July 21, Washington gave permission for the expedition to proceed.

Brodhead departed Fort Pitt on August 11, 1779, with a contingent of 605 "rank and file" from the 8th Pennsylvania Regiment, the 9th Virginia Regiment and the Maryland Rifle Corps, as well as militia, volunteers and allied Delaware

Delaware ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic and South Atlantic states, South Atlantic regions of the United States. It borders Maryland to its south and west, Pennsylvania to its north, New Jersey ...

warriors.“To George Washington from Colonel Daniel Brodhead, 16 September 1779,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-22-02-0360 The expedition proceeded northwards up the valley of the Allegheny River

The Allegheny River ( ; ; ) is a tributary of the Ohio River that is located in western Pennsylvania and New York (state), New York in the United States. It runs from its headwaters just below the middle of Pennsylvania's northern border, nor ...

into Seneca territory in what is now northwestern Pennsylvania.

Several days into the march, Brodhead's vanguard of 15 Continentals and eight Delaware encountered seven canoes with between 30 and 40 Seneca warriors heading down the Allegheny. The Seneca are reported to have beached their canoes and prepared to fight. In the ensuing skirmish five of the warriors were killed and the rest were driven off. Two Continentals and one of the Delaware suffered slight wounds. According to Seneca oral tradition, however, the "warriors" were a hunting party that had already beached their canoes when they were surprised by the Americans.

Sullivan's forces entered the abandoned settlement of Buckaloon at the mouth of Brokenstraw Creek

Brokenstraw Creek is a tributary of the Allegheny River in Warren County, Pennsylvania in the United States.Gertler, Edward. ''Keystone Canoeing'', Seneca Press, 2004.

Brokenstraw Creek is made up of two smaller streams: The "Little Brokenst ...

then proceeded eight miles further up the Allegheny to Conawago which appeared to have been abandoned several months previously. The expedition then continued twenty miles upstream to Yoghroonwago, a cluster of eight hamlets. The Seneca who lived at Yoghroonwago had fled their homes as Brodhead approached leaving many of their possessions behind. Over the next three days, Brodhead's men plundered and burned 130 houses, captured horses and cattle, and destroyed 500 acres of corn.

Although there had been earlier discussion about Brodhead linking up with Sullivan at Chenussio for an attack against Fort Niagara

Fort Niagara, also known as Old Fort Niagara, is a fortification originally built by New France to protect its interests in North America, specifically control of access between the Niagara River and Lake Ontario, the easternmost of the Great L ...

, Brodhead turned back after razing Yoghroonwago. From the mouth of French Creek, Brodhead sent a detachment upstream to destroy the settlement of Mahusqueehikoken. Like Yoghroonwago, Mahusqueehikoken had been hastily abandoned before Broadhead's forces arrived. The expedition returned to Fort Pitt on September 14 after covering 450 miles in 35 days.

Tiononderoga

The final operation of the campaign occurred in late September. From Kanadaseaga, Sullivan sent ColonelPeter Gansevoort

Peter Gansevoort (July 17, 1749 – July 2, 1812) was a Colonel in the Continental Army during the American Revolutionary War. He is best known for leading the resistance to Barry St. Leger's Siege of Fort Stanwix in 1777. Gansevoort was also ...

with 100 men to the Mohawk Valley

The Mohawk Valley region of the U.S. state of New York is the area surrounding the Mohawk River, sandwiched between the Adirondack Mountains and Catskill Mountains, northwest of the Capital District. As of the 2010 United States Census, ...

. Gansevoort was ordered to destroy the Mohawk settlement of Tiononderoga and capture the inhabitants. Sullivan believed that Tiononderoga, located beside Fort Hunter at the mouth of Schoharie Creek, was "constantly employed in giving intelligence to the enemy." Gansevoort reached Fort Stanwix

Fort Stanwix was a colonial fort whose construction commenced on August 26, 1758, under the direction of British General John Stanwix, at the location of present-day Rome, New York, but was not completed until about 1762. The bastion fort was bui ...

on September 25, and four days later surprised and captured the occupants of Tiononderoga's four houses. Gansevoort wrote, "It is remarked that the Indians live much better than most of the Mohawk River farmers, their houses very well furnished with all necessary household utensils, great plenty of grain, several horses, cows, and wagons".

A group of local colonists, homeless after earlier Indigenous raids, successfully petitioned Gansevoort to turn the houses over to them. Gansevoort's actions were criticized by Philip Schuyler

Philip John Schuyler (; November 20, 1733 - November 18, 1804) was an American general in the American Revolutionary War, Revolutionary War and a United States Senate, United States Senator from New York (state), New York. He is usually known as ...

, Commissioner for Indian Affairs and member of the Continental Congress

The Continental Congress was a series of legislature, legislative bodies, with some executive function, for the Thirteen Colonies of British America, Great Britain in North America, and the newly declared United States before, during, and after ...

, because the captured Mohawks were strictly neutral. The Mohawks were held prisoner at Albany until released on Washington's orders in late October.

British reaction

Canadian historian Gavin Watt described the British reaction to the invasion of the Iroquois homeland as "incredibly weak and ill-timed." Following France's declaration of war against Britain in June 1778, GovernorFrederick Haldimand

Sir Frederick Haldimand, KB (born François Louis Frédéric Haldimand; 11 August 1718 – 5 June 1791) was a Swiss military officer best known for his service in the British Army in North America during the Seven Years' War and the America ...

of Quebec became preoccupied with the possibility of a Franco-American invasion. As a result he focused on reinforcing the defences of the St. Lawrence River

The St. Lawrence River (, ) is a large international river in the middle latitudes of North America connecting the Great Lakes to the North Atlantic Ocean. Its waters flow in a northeasterly direction from Lake Ontario to the Gulf of St. Lawren ...

valley rather than supporting Britain's Iroquois allies by establishing a long-promised post at Oswego on Lake Ontario or increasing troop strength at Fort Niagara.

By the spring of 1779 the British had become aware that the Americans were planning a major offensive although the target was unclear. Reports had reached Quebec about the construction of a large number of bateaux

A bateau or batteau is a shallow-draft, flat-bottomed boat which was used extensively across North America, especially in the colonial period and in the fur trade. It was traditionally pointed at both ends but came in a wide variety of sizes. T ...

at Stillwater on the Hudson River

The Hudson River, historically the North River, is a river that flows from north to south largely through eastern New York (state), New York state. It originates in the Adirondack Mountains at Henderson Lake (New York), Henderson Lake in the ...

which suggested an attack on Montreal

Montreal is the List of towns in Quebec, largest city in the Provinces and territories of Canada, province of Quebec, the List of the largest municipalities in Canada by population, second-largest in Canada, and the List of North American cit ...

. Haldimand also received information that American troops were gathering at Albany and Schenectady

Schenectady ( ) is a City (New York), city in Schenectady County, New York, United States, of which it is the county seat. As of the United States Census 2020, 2020 census, the city's population of 67,047 made it the state's ninth-most populo ...

with the goal of establishing a military presence at Oswego.

Lord Germain, Secretary of State for the Colonies, expressed his belief that the building of bateaux at Stillwater indicated that the Americans intended to move forces up the Mohawk River to Fort Stanwix, and from there would move against Fort Niagara or Fort Detroit

A fortification (also called a fort, fortress, fastness, or stronghold) is a military construction designed for the defense of territories in warfare, and is used to establish rule in a region during peacetime. The term is derived from Lati ...

. Sir Henry Clinton, the commander-in-chief of British forces in America, was convinced that the Americans were planning to capture Fort Detroit and that a feint up Susquehanna River valley would be used to draw the attention of Butler's Rangers and the allied Iroquois.

In May 1779, Major Butler, accompanied by five companies of Butler's Rangers and a detachment of the 8th Regiment of Foot

Eighth is ordinal form of the number eight.

Eighth may refer to:

* One eighth, , a fraction, one of eight equal parts of a whole

* Eighth note (quaver), a musical note played for half the value of a quarter note (crotchet)

* Octave, an interval b ...

, established a forward operating base at Kanadaseaga

Kanadaseaga (aka Kanadesaga or Kanatasaka or Kanadasaga or Canasadego or Ganûndase?'ge? or Seneca Castle or Canadasaga), was a major village, perhaps a capital, of the Seneca nation of the Iroquois Confederacy in west-central New York State, Uni ...

located near the northern end of Seneca Lake. At Kanadaseaga, Butler received reports from Indigenous scouts and American deserters of the gathering of troops and the stockpiling of supplies at Canajoharie and Wyoming. He passed on this information to the British commander of Fort Niagara, Lieutenant Colonel Mason Bolton, who forwarded it to Haldimand. Butler later reported that there was no doubt that the "rebels" were coming up the Susquehanna with the ultimate goal of attacking Fort Niagara. Haldimand, however, was skeptical about the accuracy of such reports:

On July 20, Joseph Brant led his volunteers and a detachment of Butler's Rangers against the settlement of Minisink

The Minisink or (more recently) Minisink Valley is a loosely defined geographic region of the Upper Delaware River valley in northwestern New Jersey (Sussex and Warren counties), northeastern Pennsylvania ( Pike and Monroe counties) and New York ...

in the upper Delaware River

The Delaware River is a major river in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States and is the longest free-flowing (undammed) river in the Eastern United States. From the meeting of its branches in Hancock, New York, the river flows for a ...

valley. Ten houses, eleven barns, a church, and a gristmill were destroyed in the raid. Most of the settlers escaped to main fort but four men were killed and three were taken prisoner. Two days later, a force of 120 militiamen led by Colonel John Hathorn tried to intercept Brant's force at Minisink Ford. Before an ambush could be set, an accidental rifle discharge alerted Brant to the trap. Brant was able to gain the high ground behind Hathorn and in the ensuing battle 46 militiamen were killed. Brant reported three of his men killed and of the ten wounded, four were unlikely to survive.

On July 28, Captain John McDonell attacked Fort Freeland on the West Branch of the Susquehanna with his company of Butler's Rangers, a detachment of the 8th Regiment of Foot, and 120 Seneca led by Cornplanter. The fort's small garrison quickly surrendered, and a relief force that arrived shortly afterwards was routed. After interrogating the fort's commander, McDonell wrote to Butler that he had no doubt of the American intention to attack the "Indian Country" from Wyoming. He wrote that Sullivan and Maxwell had joined Hand at Wyoming with artillery, boats and pack horses. Butler passed this information to Quebec adding that Clinton was at Lake Otsego and would rendezvous with Sullivan at Tioga. In response, Haldimand wrote directly to Butler in August reaffirming his belief that Fort Detroit was the target and that the American forces on the Susquehanna were a feint.

In mid-August, Butler accompanied by about 300 Seneca and Cayuga Cayuga often refers to:

* Cayuga people, a native tribe to North America, part of the Iroquois Confederacy

* Cayuga language, the language of the Cayuga

Cayuga may also refer to:

Places Canada

*Cayuga, Ontario

United States

* Cayuga, Illinois

...

warriors led by Sayenqueraghta, Cornplanter

John Abeel III (–February 18, 1836) known as Gaiänt'wakê (''Gyantwachia'' – "the planter") or Kaiiontwa'kon (''Kaintwakon'' – "By What One Plants") in the Seneca language and thus generally known as Cornplanter, was a Dutch- Seneca ch ...

, and Fish Carrier moved south to the Chemung River where they were joined by Joseph Brant and Brant's Volunteers

Brant's Volunteers, also known as Joseph Brant's Volunteers, were an irregular unit of Loyalist and Indigenous volunteers raised during the American Revolutionary War by Mohawk war leader, Joseph Brant (Mohawk: ''Thayendanegea''). Brant's Volunt ...

, as well as a number of Delaware. Butler and Brant believed that harassment raids would be more effective than making a stand, however, they were overruled by Sayenqueraghta, Cornplanter and the Delaware. Following the Battle of Newtown, Butler retreated to Kanadaseaga and then to Chenussio. After the Boyd and Parker Ambush, he withdrew further west to Buffalo Creek.

In early September, Haldimand reluctantly decided to send reinforcements. He ordered Sir John Johnson

Brigadier-general (United Kingdom), Brigadier-General Sir John Johnson, 2nd Baronet (5 November 1741 – 4 January 1830) was an American-born military officer, politician and landowner who fought as a Loyalist (American Revolution), Loyalist dur ...

to take command of a 400-man relief expedition that would proceed from Lachine up the St Lawrence River to Carleton Island

Carleton Island is located in the St Lawrence River in upstate New York. One of the Thousand Islands, it is part of the Town of Cape Vincent, in Jefferson County.

History

Originally held by the Iroquois, one of the first Europeans to take noti ...

. The expedition consisted of soldiers from Johnson's King's Royal Regiment of New York

The King's Royal Regiment of New York, also known as Johnson's Royal Regiment of New York, King's Royal Regiment, King's Royal Yorkers, and Royal Greens, were one of the first Loyalist regiments, raised on June 19, 1776, in British Canada, durin ...

(KRRNY), detachments of the 34th Regiment of Foot

The 34th Regiment of Foot was an infantry regiment of the British Army, raised in 1702. Under the Childers Reforms it amalgamated with the 55th (Westmorland) Regiment of Foot to form the Border Regiment in 1881.

History Early history

The regime ...

and the 47th Regiment of Foot

The 47th (Lancashire) Regiment of Foot was an infantry regiment of the British Army, raised in Scotland in 1741. It served in North America during the Seven Years' War and American Revolutionary War and also fought during the Napoleonic Wars and ...

, a company of German Jäger (infantry)

(; ; , ) is a German military term referring to specific light infantry units.

In German-speaking states during the early modern era, the term ''jäger'' came to denote light infantrymen whose civilian occupations (mostly hunters and fores ...

, and Leake's Independent Company. They were joined by Mohawk, Abenaki

The Abenaki ( Abenaki: ''Wαpánahki'') are Indigenous people of the Northeastern Woodlands of Canada and the United States. They are an Algonquian-speaking people and part of the Wabanaki Confederacy. The Eastern Abenaki language was pred ...

and Wendat

The Huron-Wendat Nation (or Huron-Wendat First Nation) is an Iroquoian-speaking nation that was established in the 17th century. In the French language, used by most members of the First Nation, they are known as the . The French gave the nickn ...

warriors from the Seven Nations of Canada

The Seven Nations of Canada (called Tsiata Nihononhwentsiá:ke in the Mohawk language) was a historic confederation of First Nations living in and around the Saint Lawrence River valley beginning in the eighteenth century. They were allied to New ...

. The expedition departed Lachine on September 13 and reached Carleton Island on September 26. At Carleton Island, Johnson learned that Sullivan was withdrawing back to Tioga. He briefly considered an attack against Fort Sullivan, but abandoned the idea in favour of an attack against the Oneida. This plan was also abandoned when it was learned that the Oneida had been forewarned. Finally, Johnson received orders to have the KRRNY, Leake's and the 34th garrison Carleton Island while the Jägers were to be sent to Niagara and the 47th to Detroit.

Aftermath

Sullivan received the thanks of Congress on October 14, 1779. On November 6, 1779 he informed George Washington that he intended to resign from the Continental Army, writing "My Health is too much impair’d." Sullivan elaborated further in a letter to Congress dated November 9, 1779: "My Heal⟨th⟩ is so much impair’d by a violent bilious disorder, which seize⟨d⟩ me in the commencement, and continued during the whole of the western expedition." Congress accepted Sullivan's resignation on November 30, 1779. On September 21, 1779, there were 5036 Indigenous refugees atFort Niagara

Fort Niagara, also known as Old Fort Niagara, is a fortification originally built by New France to protect its interests in North America, specifically control of access between the Niagara River and Lake Ontario, the easternmost of the Great L ...

. This number decreased to 3,678 by October 2, and by November 21, roughly 2,600 refugees still remained at Fort Niagara. Two Seneca villages west of the Genesee River had escaped destruction and absorbed some of the refugees. A small number relocated to Carleton Island at the eastern end of Lake Ontario. Some refugees returned to their razed villages, and some moved into hunting camps. After wintering at Fort Niagara, most of the remaining Seneca and Cayuga resettled at Buffalo Creek at the eastern end of Lake Erie

Lake Erie ( ) is the fourth-largest lake by surface area of the five Great Lakes in North America and the eleventh-largest globally. It is the southernmost, shallowest, and smallest by volume of the Great Lakes and also has the shortest avera ...

.

The winter of 1780 was especially hard with frequent storms and bitter cold. New York Harbour froze completely, and British soldiers were able to march across the ice from Manhattan to Staten Island. At Fort Niagara, the Iroquois refugees who had taken shelter there suffered greatly. The snow fell several feet deep and the temperature remained well below freezing for many weeks. Deer and other game died in large numbers. An unknown number of refugees died from hypothermia, starvation, or disease.

Francis Goring, an employee of the trading firm Taylor & Forsyth, described the conditions at Fort Niagara in an October 1780 letter to his uncle:

In February 1780, Philip Schuyler

Philip John Schuyler (; November 20, 1733 - November 18, 1804) was an American general in the American Revolutionary War, Revolutionary War and a United States Senate, United States Senator from New York (state), New York. He is usually known as ...

, a member of the Continental Congress, sent four pro-rebellion Iroquois messengers to Fort Niagara. Little Abraham

Little Abraham or Tyorhansera was a Mohawk Chief who was best known for his neutral stance regarding the Revolutionary War. This was because he believed that neither side was trustworthy.

Little Abraham’s date of birth is unknown, but he died ...

, a neutral Mohawk leader, told his listeners that the Continental Congress was ready to offer peace if the refugees were to return to their own country and embrace neutrality. The Seneca war chief Sayenqueraghta was indignant. Mohawk war leader Aaron Hill accused the four of being deceitful spies. Guy Johnson

Guy Johnson ( – 5 March 1788) was a British Indian Department officer, judge and politician. He served on the side of the British during the American Revolutionary War, having migrated to the Province of New York as a young man and worked ...

, the Superintendent of the British Indian Department

The Indian Department was established in 1755 to oversee relations between the British Empire and the First Nations in Canada, First Nations of North America. The imperial government ceded control of the Indian Department to the Province of Cana ...

, ordered the messengers imprisoned in Fort Niagara's "black hole," an unheated, unlit stone cell. Little Abraham died as a result of his harsh confinement.

The year 1780 coincided with the sudden appearance of a massive number of periodical cicadas

The term periodical cicada is commonly used to refer to any of the seven species of the genus ''Magicicada'' of eastern North America, the 13- and 17-year cicadas. They are called periodical because nearly all individuals in a local population a ...

(a large insect species which emerge from underground only once every seventeen years to breed) in the region of the conflicts. The sudden arrival of such a large quantity of the insects provided a source of sustenance for the Onondaga people who were experiencing severe food insecurity following the Sullivan campaigns and the subsequent brutal winter. The seemingly miraculous arrival of the cicadas (specifically, Brood VII also known as the Onondaga brood) is commemorated by the Onondaga as though it were an intervention by the Creator to ensure their survival after such a traumatizing, catastrophic event.

294 formerly rebel Onondagas, Tuscaroras, and Oneidas arrived at Fort Niagara in early July 1780 and declared their support for the British.

The Sullivan expedition did not end Iroquois participation in the Revolutionary War. Although the destruction of their villages and crops forced the Iroquois to take refuge at Fort Niagara and put considerable strain on British resources, it also triggered devastating revenge attacks. John Butler reported that 59 war parties set out from Fort Niagara between February and September 1780. A raid on Harpersfield in April 1780 led by Joseph Brant killed three and took 11 prisoners. In May 1780, Iroquois warriors accompanied Sir John Johnson

Brigadier-general (United Kingdom), Brigadier-General Sir John Johnson, 2nd Baronet (5 November 1741 – 4 January 1830) was an American-born military officer, politician and landowner who fought as a Loyalist (American Revolution), Loyalist dur ...

and the King's Royal Regiment of New York

The King's Royal Regiment of New York, also known as Johnson's Royal Regiment of New York, King's Royal Regiment, King's Royal Yorkers, and Royal Greens, were one of the first Loyalist regiments, raised on June 19, 1776, in British Canada, durin ...

in a raid that destroyed every building in Caughnawaga except for the church. In October, Johnson led a second expedition against the Schoharie and Mohawk valleys in which 200 dwellings were burned and 150,000 tons of grain destroyed. 265 Iroquois warriors including Brant, Cornplanter and Sayenqueraghta participated in this expedition during which 40 patriot militia were killed at the Battle of Stone Arabia. In total, the Mohawk and Schoharie valleys saw 330 men, women and children killed or taken prisoner, six forts and several mills destroyed, and over 700 houses and barns burned in 1780.

According to Barbara Graymont, author of The ''Iroquois in the American Revolution'', "the campaign of 1780 was an eloquent testimony to the ineffectiveness of Sullivan's expedition in quelling the Indian threat to the frontier." Military historian Joseph Fischer describes the Sullivan Expedition expedition as a "well-executed failure." In his conclusion to his journal of the campaign, Major Jeremiah Fogg noted: "The nests are destroyed, but the birds are still on the wing."

The Iroquois were ignored in the peace negotiations between the United States and Britain that led to the 1783 Treaty of Paris. Beginning in 1784, the United States negotiated a series of treaties with the Iroquois that led to the cession of most of their traditional territory. In the October 1784 Treaty of Fort Stanwix

The Treaty of Fort Stanwix was a treaty signed between representatives from the Iroquois and Great Britain (accompanied by negotiators from New Jersey, Virginia and Province of Pennsylvania, Pennsylvania) in 1768 at Fort Stanwix. It was negotia ...

, the Iroquois delegates relinquished their claims to the Ohio Country, and ceded a strip of land along the east side of the Niagara River as well as all of their territory west of mouth of Buffalo Creek. The Six Nations in council at Buffalo Creek, however, refused to ratify the treaty, denying that their delegates had the authority to surrender such large tracts of land.

In October 1784, Sir Frederick Haldimand, the governor of the province of Quebec, signed a decree that granted to the Iroquois in compensation for their alliance with British forces during the war. This tract of land, known as the Haldimand Tract, extended for six miles (9.7 km) to each side of the Grand River, from its source to Lake Erie. In 1785, Joseph Brant led about 1,450 to the Haldimand Tract. Others, primarily Mohawk, settled with John Deseronto

Captain John Deserontyon (alt. Captain John, Deseronto, (Odeserundiye)), U.E.L (c. 1740s - 1811) was a Mohawk war chief allied with the British during the American Revolutionary War. He led his people to Upper Canada after the war, settling on ...

on the Bay of Quinte. A significant number of Seneca, Cayuga and Onondaga remained at Buffalo Creek.

In 1788, at the First Treaty of Buffalo Creek

The First Treaty of Buffalo Creek signed on July 8, 1788 Phelps and Gorham purchased title to lands east from the Genesee River in New York to the Preemption Line.

See also

* Treaty of Canandaigua

* Treaty of Big Tree

The Treaty of Big Tre ...

, a syndicate of land speculators led by Oliver Phelps and Nathaniel Gorham

Nathaniel Gorham (May 27, 1738 – June 11, 1796; sometimes spelled ''Nathanial'') was an American Founding Father, merchant, and politician from Massachusetts. He was a delegate from the Bay Colony to the Continental Congress and for six months ...

purchased from the Seneca their territory between the Genessee River and Seneca Lake. The following year the Cayuga ceded to New York most of their traditional territory except for roughly 64,000 acres at the north end of Cayuga Lake. The November 1794 Treaty of Canandaigua

The Treaty of Canandaigua (or Konondaigua, as spelled in the treaty itself), also known as the Pickering Treaty and the Calico Treaty, is a treaty signed after the American Revolutionary War between the Grand Council of the Six Nations and Presi ...

established perpetual “peace and friendship” between the Iroquois and the United States, and acknowledged the sovereignty of the Iroquois within their lands. The 1797 Treaty of Big Tree

The Treaty of Big Tree was a formal treaty signed in 1797 between the Seneca Nation and the United States, in which the Seneca relinquished their rights to nearly all of their traditional homeland in New York State—nearly 3.5 million acres. I ...

saw the Seneca relinquish their rights to most of their remaining territory west of the Genesee River. 12 parcels of land were reserved for the Seneca including tracts at Buffalo Creek, Tonawanda, Allegany, and Cattaraugus.