Justice Betrayed: Post-1945 Responses to Genocide

" In David A. Blumenthal and Timothy L. H. McCormack (eds).

The Legacy of Nuremberg: Civilising Influence or Institutionalised Vengeance? (International Humanitarian Law).

''

80

Suharto officially became president in 1967, while Sukarno was placed under

Name

The name ''Sukarno'' comes from the mythological chief hero of the ''Steven Drakeley, University of Western Sydney He is sometimes referred to in foreign accounts as Achmed Sukarno, or some variation thereof. A source from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs revealed that "Achmed" (later, written as "Ahmad" or "Ahmed" by Arab states and other foreign state press) was coined by M. Zein Hassan, an Indonesian student at

Early life and family

The son of a Muslim Javanese primary school teacher, a ''Education

After graduating from a native primary school in 1912, he was sent to the ''Europeesche Lagere School'' (a Dutch primary school) inArchitectural career

After graduation in 1926, Sukarno and his university friend Anwari established the architectural firm Soekarno & Anwari in Bandung, which provided planning and contractor services. Among Sukarno's architectural works are the renovated building of the Preanger Hotel (1929), where he acted as assistant to famous Dutch architect Charles Prosper Wolff Schoemaker. Sukarno also designed many private houses on today's Jalan Gatot Subroto, Jalan Palasari, and Jalan Dewi Sartika in Bandung. Later on, as president, Sukarno remained engaged in architecture, designing the Proclamation Monument and adjacent ''Gedung Pola'' in Jakarta; the Youth Monument (''Tugu Muda'') inEarly struggle

Sukarno was first exposed to nationalist ideas while living under Tjokroaminoto. Later, while a student in Bandung, he immersed himself inInvolvement in the Indonesian National Party

On 4 July 1927, Sukarno with his friends from the ''Algemeene Studieclub'' established a pro-independence party, the

On 4 July 1927, Sukarno with his friends from the ''Algemeene Studieclub'' established a pro-independence party, the Arrest, trial, and imprisonment

Arrest and trial

PNI activities came to the attention of the colonial government, and Sukarno's speeches and meetings were often infiltrated and disrupted by agents of the colonial secret police ( ''Politieke Inlichtingendienst''). Eventually, Sukarno and other key PNI leaders were arrested on 29 December 1929 by Dutch colonial authorities in a series of raids throughout Java. Sukarno himself was arrested while on a visit to

PNI activities came to the attention of the colonial government, and Sukarno's speeches and meetings were often infiltrated and disrupted by agents of the colonial secret police ( ''Politieke Inlichtingendienst''). Eventually, Sukarno and other key PNI leaders were arrested on 29 December 1929 by Dutch colonial authorities in a series of raids throughout Java. Sukarno himself was arrested while on a visit to Imprisonment

In December 1930, Sukarno was sentenced to four years in prison, which were served in Sukamiskin prison in Bandung. His speech, however, received extensive coverage by the press, and due to strong pressure from the liberal elements in both theExile to Flores and Bengkulu

This time, to prevent providing Sukarno with a platform to make political speeches, the hardline governor-generalWorld War II and the Japanese occupation

Background and invasion

In early 1929, during theCooperation with the Japanese

The Japanese had their own files on Sukarno, and the Japanese commander in Sumatra approached him with respect, wanting to use him to organize and pacify the Indonesians. Sukarno, on the other hand, wanted to use the Japanese to gain independence for Indonesia: "The Lord be praised, God showed me the way; in that valley of the Ngarai I said: Yes, Independent Indonesia can only be achieved with Dai Nippon...For the first time in all my life, I saw myself in the mirror of Asia." In July 1942, Sukarno was sent back to Jakarta, where he re-united with other nationalist leaders recently released by the Japanese, including Hatta. There, he met the Japanese commander General

The Japanese had their own files on Sukarno, and the Japanese commander in Sumatra approached him with respect, wanting to use him to organize and pacify the Indonesians. Sukarno, on the other hand, wanted to use the Japanese to gain independence for Indonesia: "The Lord be praised, God showed me the way; in that valley of the Ngarai I said: Yes, Independent Indonesia can only be achieved with Dai Nippon...For the first time in all my life, I saw myself in the mirror of Asia." In July 1942, Sukarno was sent back to Jakarta, where he re-united with other nationalist leaders recently released by the Japanese, including Hatta. There, he met the Japanese commander General Investigating Committee for Preparatory Work for Independence

On 29 April 1945, when the

On 29 April 1945, when the Preparatory Committee for Indonesian Independence

On 7 August 1945, the Japanese allowed the formation of a smaller Preparatory Committee for Indonesian Independence (, PPKI), a 21-person committee tasked with creating the specific governmental structure of the future Indonesian state. On 9 August, the top leaders of PPKI (Sukarno, Hatta and Radjiman Wediodiningrat, KRT Radjiman Wediodiningrat), were summoned by the commander-in-chief of Japan's Southern Expeditionary Forces, Field Marshal Hisaichi Terauchi, to Da Lat, 100 km from Saigon. Terauchi gave Sukarno the freedom to proceed with preparation for Indonesian independence, free of Japanese interference. After much wining and dining, Sukarno's entourage was flown back to Jakarta on 14 August. Unbeknownst to the guests, Atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, atomic bombs had been dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and the Japanese were preparing for Surrender of Japan, surrender.Japanese surrender

The following day, on 15 August, the Japanese declared their acceptance of the Potsdam Declaration terms and unconditionally surrendered to the Allies. On the afternoon of that day, Sukarno received this information from leaders of youth groups and members of PETA Chairul Saleh, Soekarni, and Wikana, who had been listening to Western radio broadcasts. They urged Sukarno to declare Indonesian independence immediately, while the Japanese were in confusion and before the arrival of Allied forces. Faced with this quick turn of events, Sukarno procrastinated. He feared a bloodbath due to hostile response from the Japanese to such a move and was concerned with prospects of future Allied retribution.Kidnapping incident

On the early morning of 16 August, the three youth leaders, impatient with Sukarno's indecision, kidnapped him from his house and brought him to a small house in Rengasdengklok, Karawang, owned by a Chinese family and occupied by PETA. There they gained Sukarno's commitment to declare independence the next day. That night, the youths drove Sukarno back to the house of Admiral Tadashi Maeda, the Japanese naval liaison officer in the Menteng area of Jakarta, who sympathised with Indonesian independence. There, he and his assistant Sajoeti Melik prepared the text of the Proclamation of Indonesian Independence.Indonesian National Revolution

Proclamation of Indonesian Independence

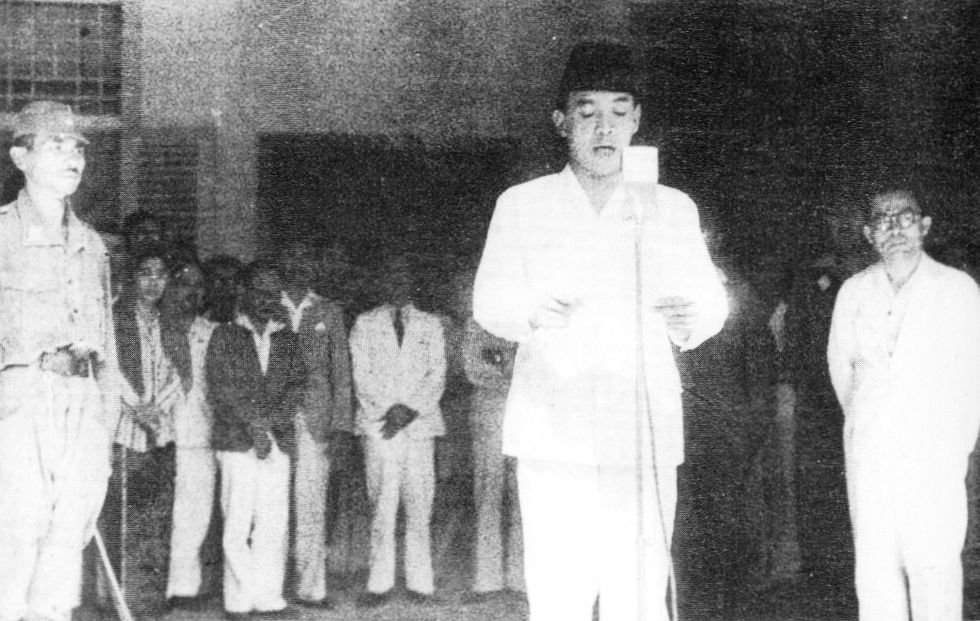

In the early morning of 17 August 1945, Sukarno returned to his house at Jalan Pegangsaan Timur No. 56, where Hatta joined him. Throughout the morning, impromptu leaflets printed by PETA and youth elements informed the population of the impending proclamation. Finally, at 10 am, Sukarno and Hatta stepped to the front porch, where Sukarno declared the Indonesian Declaration of Independence, independence of the Republic of Indonesia in front of a crowd of 500 people. This most historic of buildings was later ordered to be demolished by Sukarno himself, without any apparent reason.

On the following day, 18 August, the PPKI declared the basic governmental structure of the new Republic of Indonesia:

# Preparatory Committee for Indonesian Independence#Actions of the PPKI, Electing Sukarno and Hatta as president and vice-president, respectively.

# Putting into effect the 1945 Indonesian Constitution of Indonesia, constitution, which by this time excluded any reference to Islamic law.

# Establishing a Central Indonesian National Committee (, KNIP) to assist the president before an election of a parliament.

Sukarno's vision for the 1945 Indonesian Constitution of Indonesia, constitution comprised the Pancasila Indonesia, Pancasila (''five principles''). Sukarno's political philosophy was mainly a fusion of elements of Marxism, nationalism and Islam. This is reflected in a proposition of his version of Pancasila he proposed to the BPUPK in a speech on 1 June 1945.

Sukarno argued that all of the principles of the nation could be summarised in the phrase ''gotong royong.'' The Indonesian parliament, founded on the basis of this original (and subsequently revised) constitution, proved all but ungovernable. This was due to irreconcilable differences between various social, political, religious and ethnic factions.

In the early morning of 17 August 1945, Sukarno returned to his house at Jalan Pegangsaan Timur No. 56, where Hatta joined him. Throughout the morning, impromptu leaflets printed by PETA and youth elements informed the population of the impending proclamation. Finally, at 10 am, Sukarno and Hatta stepped to the front porch, where Sukarno declared the Indonesian Declaration of Independence, independence of the Republic of Indonesia in front of a crowd of 500 people. This most historic of buildings was later ordered to be demolished by Sukarno himself, without any apparent reason.

On the following day, 18 August, the PPKI declared the basic governmental structure of the new Republic of Indonesia:

# Preparatory Committee for Indonesian Independence#Actions of the PPKI, Electing Sukarno and Hatta as president and vice-president, respectively.

# Putting into effect the 1945 Indonesian Constitution of Indonesia, constitution, which by this time excluded any reference to Islamic law.

# Establishing a Central Indonesian National Committee (, KNIP) to assist the president before an election of a parliament.

Sukarno's vision for the 1945 Indonesian Constitution of Indonesia, constitution comprised the Pancasila Indonesia, Pancasila (''five principles''). Sukarno's political philosophy was mainly a fusion of elements of Marxism, nationalism and Islam. This is reflected in a proposition of his version of Pancasila he proposed to the BPUPK in a speech on 1 June 1945.

Sukarno argued that all of the principles of the nation could be summarised in the phrase ''gotong royong.'' The Indonesian parliament, founded on the basis of this original (and subsequently revised) constitution, proved all but ungovernable. This was due to irreconcilable differences between various social, political, religious and ethnic factions.

Revolution and ''Bersiap''

In the days following the proclamation, the news of Indonesian independence was spread by radio, newspaper, leaflets, and word of mouth despite attempts by the Japanese soldiers to suppress the news. On 19 September, Sukarno addressed a crowd of one million people at the Ikada Field of Jakarta (now part of Merdeka Square, Jakarta, Merdeka Square) to commemorate one month of independence, indicating the strong level of popular support for the new Republic, at least on Java and Sumatra. In these two islands, the Sukarno government quickly established governmental control while the remaining Japanese mostly retreated to their barracks awaiting the arrival of Allied forces. This period was marked by constant attacks by armed groups on anyone who was perceived to oppose Indonesian independence. The most serious cases were the Social Revolutions in Aceh and North Sumatra, North Sumatera, where large numbers of Acehnese and Malay aristocrats were killed, and the "Three Regions Affair" in the northwestern coast of Central Java. These bloody incidents continued until late 1945 to early 1946, and began to peter out as republican authorities began to exert and consolidate control. Sukarno's government initially postponed the formation of a national army, for fear of antagonizing the Allied occupation forces and their doubt over whether they would have been able to form an adequate military apparatus to maintain control of seized territory. The members of various militia groups formed during Japanese occupation such as the disbanded PETA and ''Heiho'', at that time were encouraged to join the BKR - (The People's Security Organization), itself a subordinate of the "War Victims Assistance Organization". It was only in October 1945 that the BKR was reformed into the TKR – (People's Security Army) in response to the increasing Allied and Dutch presence in Indonesia. The TKR armed themselves mostly by attacking Japanese troops and confiscating their weapons. Due to the sudden transfer of Java and Sumatra from General Douglas MacArthur's American-controlled Southwest Pacific Command to Lord Louis Mountbatten's British-controlled Southeast Asian Command, the first Allied soldiers (1st Battalion of Seaforth Highlanders) did not arrive in Jakarta until late September 1945. British forces began to occupy major Indonesian cities in October 1945. The commander of the British 23rd Division, Lieutenant General Sir Philip Christison, set up command in the former governor-general's palace in Jakarta. Christison stated that he intended to free all Allied prisoners-of-war and to allow the return of Indonesia to its pre-war status, as a colony of the Netherlands. The republican government were willing to cooperate with the release and repatriation of Allied civilians and military POWs, setting up the Committee for the Repatriation of Japanese and Allied Prisoners of War and Internees (, POPDA) for this purpose. POPDA, in cooperation with the British, repatriated more than 70,000 Japanese and Allied POWs and internees by the end of 1946. However, due to the relative weakness of the military of the Republic of Indonesia, Sukarno sought independence by gaining international recognition for his new country rather than engage in battle with British and Dutch military forces. Sukarno was aware that his history as a Japanese Collaboration, collaborator and his leadership in the Japanese-approved during the occupation would make the Western countries distrustful of him. To help gain international recognition as well as to accommodate domestic demands for representation, Sukarno "allowed" the formation of a parliamentary system of government, whereby a Prime Minister of Indonesia, prime minister controlled day-to-day affairs of the government, while Sukarno as president remained as a figurehead. The prime minister and his cabinet would be responsible to the Central Indonesian National Committee instead of the president. On 14 November 1945, Sukarno appointed

Sukarno was aware that his history as a Japanese Collaboration, collaborator and his leadership in the Japanese-approved during the occupation would make the Western countries distrustful of him. To help gain international recognition as well as to accommodate domestic demands for representation, Sukarno "allowed" the formation of a parliamentary system of government, whereby a Prime Minister of Indonesia, prime minister controlled day-to-day affairs of the government, while Sukarno as president remained as a figurehead. The prime minister and his cabinet would be responsible to the Central Indonesian National Committee instead of the president. On 14 November 1945, Sukarno appointed Linggadjati Agreement and Operation Product

Linggadjati Agreement

Sukarno's decision to negotiate with the Dutch was met with strong opposition by various Indonesian factions. Tan Malaka, a Indonesian Communist Party, communist politician, organized these groups into a united front called the ''Persatoean Perdjoangan'' (PP). PP offered a "Minimum Program" which called for complete independence, nationalisation of all foreign properties, and rejection of all negotiations until all foreign troops are withdrawn. These programmes received widespread popular support, including from armed forces commander General Sudirman. On 4 July 1946, military units linked with PP kidnapped Prime Minister Sjahrir who was visiting Yogyakarta. Sjahrir was leading the negotiation with the Dutch. Sukarno, after successfully influencing Sudirman, managed to secure the release of Sjahrir and the arrest of Tan Malaka and other PP leaders. Disapproval of Linggadjati terms within the KNIP led Sukarno to issue a decree doubling KNIP membership by including many pro-agreement appointed members. As a consequence, KNIP ratified the Linggadjati Agreement in March 1947.

Sukarno's decision to negotiate with the Dutch was met with strong opposition by various Indonesian factions. Tan Malaka, a Indonesian Communist Party, communist politician, organized these groups into a united front called the ''Persatoean Perdjoangan'' (PP). PP offered a "Minimum Program" which called for complete independence, nationalisation of all foreign properties, and rejection of all negotiations until all foreign troops are withdrawn. These programmes received widespread popular support, including from armed forces commander General Sudirman. On 4 July 1946, military units linked with PP kidnapped Prime Minister Sjahrir who was visiting Yogyakarta. Sjahrir was leading the negotiation with the Dutch. Sukarno, after successfully influencing Sudirman, managed to secure the release of Sjahrir and the arrest of Tan Malaka and other PP leaders. Disapproval of Linggadjati terms within the KNIP led Sukarno to issue a decree doubling KNIP membership by including many pro-agreement appointed members. As a consequence, KNIP ratified the Linggadjati Agreement in March 1947.

Operation Product

On 21 July 1947, the Linggadjati Agreement was broken by the Dutch, who launched Operatie Product, a massive military invasion into republican-held territories. Although the newly reconstituted Indonesian National Armed Forces, TNI was unable to offer significant military resistance, the blatant violation by the Dutch of an internationally brokered agreement outraged world opinion. International pressure forced the Dutch to halt their invasion force in August 1947. Sjahrir, who had been replaced as prime minister by Amir Sjarifuddin, flew to New York City to appeal the Indonesian case in front of the United Nations. The UN Security Council issued a resolution calling for an immediate ceasefire and appointed a Good Offices Committee (GOC) to oversee the ceasefire. The GOC, based in Jakarta, consisted of delegations from Australia (led by Richard Kirby (arbitrator), Richard Kirby, chosen by Indonesia), Belgium (led by Paul van Zeeland, chosen by the Netherlands), and the United States (led by Frank Porter Graham, neutral). The republic was now under firm Dutch military stranglehold, with the Dutch military occupying West Java, and the northern coast of Central Java and East Java, along with the key productive areas of Sumatra. Additionally, the Dutch navy blockaded republican areas from supplies of vital food, medicine, and weapons. As a consequence, Prime Minister Amir Sjarifuddin had little choice but to sign the Renville Agreement on 17 January 1948, which acknowledged Dutch control over areas taken during Operatie Product, while the republicans pledged to withdraw all forces that remained on the other side of the ceasefire line ("Van Mook Line"). Meanwhile, the Dutch begin to organize Puppet government, puppet states in the areas under their occupation, to counter republican influence utilising ethnic diversity of Indonesia.Renville agreement and Madiun affair

The signing of the highly disadvantageous Renville Agreement caused even greater instability within the republican political structure. In Dutch-occupied West Java, Darul Islam (Indonesia), Darul Islam guerrilla warfare, guerrillas under Sekarmadji Maridjan Kartosuwirjo maintained their anti-Dutch resistance and repealed any loyalty to the Republic; they caused a bloody insurgency in West Java and other areas in the first decades of independence. Prime Minister Sjarifuddin, who signed the agreement, was forced to resign in January 1948 and was replaced by Hatta. Hatta's cabinet's policy of rationalising the armed forces by demobilising large numbers of armed groups that proliferated the republican areas also caused severe disaffection. Leftist political elements, led by resurgent Indonesian Communist Party (PKI) under Musso took advantage of public disaffections by launching a rebellion in Madiun, East Java, on 18 September 1948. Bloody fighting continued during late-September until the end of October 1948, when the last communist bands were defeated, and Musso shot dead. The communists had overestimated their potential to oppose the strong appeal of Sukarno amongst the population.Operation Kraai and exile

Invasion and exile

On 19 December 1948, to take advantage of the republic's weak position following the communist rebellion, the Dutch launched Operation Kraai, a second military invasion designed to crush the Republic once and for all. The invasion was initiated with an airborne assault on the republican capital Yogyakarta. Sukarno ordered the armed forces under Sudirman to launch a guerrilla campaign in the countryside, while he and other key leaders such as Hatta and Sjahrir allowed themselves to be taken prisoner by the Dutch. To ensure continuity of government, Sukarno sent a telegram to Sjarifuddin, providing him with the mandate to lead an Emergency Government of the Republic of Indonesia (PDRI), based on the unoccupied hinterlands of West Sumatra, a position he kept until Sukarno was released in June 1949. The Dutch sent Sukarno and other captured republican leaders to captivity in Parapat, in Dutch-occupied part of North Sumatra and later to the island of Bangka Island, Bangka.

On 19 December 1948, to take advantage of the republic's weak position following the communist rebellion, the Dutch launched Operation Kraai, a second military invasion designed to crush the Republic once and for all. The invasion was initiated with an airborne assault on the republican capital Yogyakarta. Sukarno ordered the armed forces under Sudirman to launch a guerrilla campaign in the countryside, while he and other key leaders such as Hatta and Sjahrir allowed themselves to be taken prisoner by the Dutch. To ensure continuity of government, Sukarno sent a telegram to Sjarifuddin, providing him with the mandate to lead an Emergency Government of the Republic of Indonesia (PDRI), based on the unoccupied hinterlands of West Sumatra, a position he kept until Sukarno was released in June 1949. The Dutch sent Sukarno and other captured republican leaders to captivity in Parapat, in Dutch-occupied part of North Sumatra and later to the island of Bangka Island, Bangka.

Aftermath

The second Dutch invasion caused even more international outrage. The United States, impressed by Indonesia's ability to defeat the 1948 communist challenge without outside help, threatened to cut off Marshall Aid funds to the Netherlands if military operations in Indonesia continued. TNI did not disintegrate and continued to wage guerrilla resistance against the Dutch, most notably the assault on Dutch-held Yogyakarta led by Lieutenant ColonelPresident of the United States of Indonesia

At this time, as part of a compromise with the Dutch, Indonesia adopted a new Federal Constitution of 1949, federal constitution that made the country a federal state called the Republic of United States of Indonesia ( Indonesian: ''Republik Indonesia Serikat, RIS''), consisting of the Republic of Indonesia whose borders were determined by the "Van Mook Line", along with the six states and nine autonomous territories created by the Dutch. During the first half of 1950, these states gradually dissolved themselves as the Dutch military that previously propped them up was withdrawn. In August 1950, with the last state, the State of East Indonesia dissolving itself, Sukarno declared a Unitary Republic of Indonesia based on the newly formulated Provisional Constitution of 1950, provisional constitution of 1950.Liberal Democracy period (1950–1959)

Both the Federal Constitution of 1949 and the Provisional Constitution of 1950 were parliamentary in nature, where executive authority lay with the prime minister, and which, on paper, limited presidential power. However, even with his formally reduced role, he commanded a good deal of moral authority as Father of the Nation.Instability and rebellions

The first years of parliamentary democracy proved to be very unstable for Indonesia. Cabinets fell in rapid succession due to the sharp differences between the various political parties within the House of Representatives (Indonesia), newly-appointed parliament (, DPR). There were severe disagreements concerning the future path of the Indonesian state, between nationalists who wanted a secular state (led by Indonesian National Party, PNI, first established by Sukarno), Islamists who wanted an Islamic state (led by the Masyumi Party), and communists who wanted a communist state (led by the PKI, which only in 1951 again became allowed to operate). On the economic front, there was severe dissatisfaction with continuing economic domination by large Dutch corporations and the ethnic Chinese.Darul Islam rebels

The Darul Islam rebels under Sekarmadji Maridjan Kartosuwiryo, Kartosuwirjo in West Java refused to acknowledge Sukarno's authority and declared an NII (Negara Islam Indonesia - Islamic State of Indonesia) in August 1949. Rebellions in support of Darul Islam also broke out in South Sulawesi in 1951, and in Aceh in 1953. Meanwhile, pro-federalist members of the disbanded Royal Dutch East Indies Army, KNIL launched failed rebellions in Bandung (APRA coup d'état, APRA rebellion of 1950), in Makassar Uprising, Makassar in 1950, and Ambon (Republic of South Maluku revolt of 1950).Division in the military

Additionally, the military was torn by hostilities between officers originating from the colonial-era KNIL, who wished for a small and elite professional military, and the overwhelming majority of soldiers who started their careers in the Japanese-formed PETA, who were afraid of being discharged and were more known for nationalist-zeal over professionalism.

On 17 October 1952, the leaders of the former-KNIL faction, Army Chief Colonel Abdul Haris Nasution and Armed Forces Chief-of-Staff Tahi Bonar Simatupang mobilised their troops in a show of force. Protesting against attempts by the DPR to interfere in military business on behalf of the former PETA faction of the military, Nasution and Simatupang had their troops surround the Merdeka Palace and point their tank turrets at the building. Their demand for Sukarno was that the current DPR be dismissed. For this cause, Nasution and Simatupang also mobilised civilian protesters. Sukarno came out of the palace and convinced both the soldiers and the civilians to go home. Nasution and Simatupang were later dismissed. Nasution, however, would be re-appointed as Army Chief after reconciling with Sukarno in 1955.

Additionally, the military was torn by hostilities between officers originating from the colonial-era KNIL, who wished for a small and elite professional military, and the overwhelming majority of soldiers who started their careers in the Japanese-formed PETA, who were afraid of being discharged and were more known for nationalist-zeal over professionalism.

On 17 October 1952, the leaders of the former-KNIL faction, Army Chief Colonel Abdul Haris Nasution and Armed Forces Chief-of-Staff Tahi Bonar Simatupang mobilised their troops in a show of force. Protesting against attempts by the DPR to interfere in military business on behalf of the former PETA faction of the military, Nasution and Simatupang had their troops surround the Merdeka Palace and point their tank turrets at the building. Their demand for Sukarno was that the current DPR be dismissed. For this cause, Nasution and Simatupang also mobilised civilian protesters. Sukarno came out of the palace and convinced both the soldiers and the civilians to go home. Nasution and Simatupang were later dismissed. Nasution, however, would be re-appointed as Army Chief after reconciling with Sukarno in 1955.

Legislative elections

The 1955 Indonesian legislative election, 1955 elections produced a new House of Representatives (Indonesia), parliament and a Constitutional Assembly of Indonesia, constitutional assembly. The election results showed equal support for the antagonistic powers of the PNI, Masyumi, Nahdlatul Ulama, and PKI parties. With no faction controlling a clear majority, domestic political instability continued unabated. Talks in the Constitutional Assembly to write a new constitution met with deadlock over the issue of whether to include Islamic law.

Sukarno came to resent his figurehead position and the increasing disorder of the country's political life. Claiming that Western-style parliamentary democracy was unsuitable for Indonesia, he called for a system of "guided democracy," which he claimed was based on indigenous principles of governance. Sukarno argued that at the village level, important questions were decided by lengthy deliberation designed to achieve a Consensus decision-making, consensus, under the guidance of village elders. He believed it should be the model for the entire nation, with the president taking the role assumed by village elders. He proposed a government based not only on political parties but on "functional groups" composed of the nation's essential elements, which would together form a National Council, through which a national consensus could express itself under presidential guidance.

Vice President Hatta was strongly opposed to Sukarno's guided democracy concept. Citing this and other irreconcilable differences, Hatta resigned from his position in December 1956. His retirement sent a shockwave across Indonesia, particularly among the non-Javanese, who viewed Hatta as their representative in a Javanese-dominated government.

The 1955 Indonesian legislative election, 1955 elections produced a new House of Representatives (Indonesia), parliament and a Constitutional Assembly of Indonesia, constitutional assembly. The election results showed equal support for the antagonistic powers of the PNI, Masyumi, Nahdlatul Ulama, and PKI parties. With no faction controlling a clear majority, domestic political instability continued unabated. Talks in the Constitutional Assembly to write a new constitution met with deadlock over the issue of whether to include Islamic law.

Sukarno came to resent his figurehead position and the increasing disorder of the country's political life. Claiming that Western-style parliamentary democracy was unsuitable for Indonesia, he called for a system of "guided democracy," which he claimed was based on indigenous principles of governance. Sukarno argued that at the village level, important questions were decided by lengthy deliberation designed to achieve a Consensus decision-making, consensus, under the guidance of village elders. He believed it should be the model for the entire nation, with the president taking the role assumed by village elders. He proposed a government based not only on political parties but on "functional groups" composed of the nation's essential elements, which would together form a National Council, through which a national consensus could express itself under presidential guidance.

Vice President Hatta was strongly opposed to Sukarno's guided democracy concept. Citing this and other irreconcilable differences, Hatta resigned from his position in December 1956. His retirement sent a shockwave across Indonesia, particularly among the non-Javanese, who viewed Hatta as their representative in a Javanese-dominated government.

Military takeovers and martial law

Regional military takeovers

From December 1956 to January 1957, regional military commanders in the provinces of North, Central, and South Sumatra took over local government control. They declared a series of military councils which were to run their respective areas and refused to accept orders from Jakarta. A similar regional military movement took control of North Sulawesi in March 1957. They demanded the elimination of communist influence in government, an equal share in government revenues, and reinstatement of the former Sukarno-Hatta duumvirate.Declaration of martial law

Faced with this serious challenge to the unity of the republic, Sukarno declared martial law (''Staat van Oorlog en Beleg'') on 14 March 1957. He appointed a non-partisan prime minister Djuanda Kartawidjaja, while the military was in the hands of his loyal General Nasution. Nasution increasingly shared Sukarno's views on the negative impact of western democracy on Indonesia, and he saw a more significant role for the military in political life. As a reconciliatory move, Sukarno invited the leaders of the regional councils to Jakarta on 10–14 September 1957, to attend a National Conference (''Musjawarah Nasional''), which failed to bring a solution to the crisis. On 30 November 1957, an assassination attempt was made on Sukarno by way of a grenade attack while he was visiting a school function in Cikini, Central Jakarta. Six children were killed, but Sukarno did not suffer any serious wounds. The perpetrators were members of the Darul Islam group, under the order of its leader Sekarmadji Maridjan Kartosuwirjo. By December 1957, Sukarno began to take serious steps to enforce his authority over the country. On that month, he nationalised 246 Dutch companies which had been dominating the Indonesian economy, most notably the Netherlands Trading Society, Royal Dutch Shell subsidiary ''Bataafsche Petroleum Maatschappij'', Escomptobank, and the "big five" Dutch trading corporations (''NV Borneo Sumatra Maatschappij / Borsumij'', ''NV Internationale Crediet- en Handelsvereeneging "Rotterdam" / Internatio'', ''NV Jacobson van den Berg & Co'', ''NV Lindeteves-Stokvis'', and ''NV Geo Wehry & Co''), and expelled 40,000 Indo people, Dutch citizens remaining in Indonesia while confiscating their properties, purportedly due to the failure by the Dutch government to continue negotiations on the fate of Netherlands New Guinea as was promised in the 1949 Round Table Conference. Sukarno's policy of economic nationalism was strengthened by the issuance of Presidential Directive No. 10 of 1959, which banned commercial activities by foreign nationals in rural areas. This rule targeted ethnic Chinese, who dominated both the rural and urban retail economy, although at this time few of them had Indonesian citizenship. This policy resulted in massive relocation of the rural ethnic-Chinese population to urban areas, and approximately 100,000 chose to return to China. To face the dissident regional commanders, Sukarno and Army Chief Nasution decided to take drastic steps following the failure of ''Musjawarah Nasional''. By utilizing regional officers that remained loyal to Jakarta, Nasution organized a series of "regional coups" which ousted the dissident commanders in North Sumatra (Colonel Maludin Simbolon) and South Sumatra (Colonel Barlian) by December 1957. This returned government control over key cities of Medan and Palembang. In February 1958, the remaining dissident commanders in Central Sumatra (Colonel Ahmad Hussein) and North Sulawesi (Colonel Ventje Sumual) formed the Revolutionary Government of the Republic of Indonesia, PRRI-Permesta Movement aimed at overthrowing the Jakarta government. They were joined by many civilian politicians from the Masyumi Party, such as Sjafruddin Prawiranegara, who were opposed to the growing influence of communists. Due to their anti-communist rhetoric, the rebels received money, weapons, and manpower from the Central Intelligence Agency, CIA in a campaign known as Archipelago. This support ended when Allen Lawrence Pope, an American pilot, was shot down after a bombing raid on government-held Ambon, Maluku, Ambon in April 1958. In April 1958, the central government responded by launching airborne and seaborne military invasions on Padang and Manado, the rebel capitals. By the end of 1958, the rebels had been militarily defeated, and the last remaining rebel guerrilla bands surrendered in August 1961.Guided Democracy period (1959–1966)

The impressive military victories over the PRRI-Permesta rebels and the popular nationalisation of Dutch companies left Sukarno in a firm position. On 5 July 1959, Sukarno reinstated the 1945 constitution by President Sukarno's 1959 Decree, presidential decree. It established a presidential system which he believed would make it easier to implement the principles of guided democracy. He called the system or , but it was actually rule by decree, government by decree. Sukarno envisioned an Indonesian-style socialist society, adherent to the principle of USDEK: # (Constitution of 1945) # (Indonesian Socialism) # (Guided Democracy) # (Command economy, Commanded Economy). # (Indonesia's Identity) After establishing guided democracy, Sukarno along with Maladi met Devi Dja, an Indonesian-born dancer who changed her citizenship to the United States, in mid-1959, and convinced her to return as an Indonesian citizen, which Dja refused and credited him as an extreme nationalist person. In March 1960, Sukarno disbanded parliament and replaced it with a new parliament where half the members were appointed by the president (''Dewan Perwakilan Rakjat - Gotong Rojong'' / DPR-GR). In September 1960, he established a People's Consultative Assembly, Provisional People's Consultative Assembly (''Madjelis Permusjawaratan Rakjat Sementara''/MPRS) as the highest legislative authority according to the 1945 constitution. MPRS members consisted of members of DPR-GR and members of "functional groups" appointed by the president. With the backing of the military, Sukarno disbanded the Islamic party Masyumi and Sutan Sjahrir's party Socialist Party of Indonesia, PSI, accusing them of involvement with PRRI-Permesta affair. The military arrested and imprisoned many of Sukarno's political opponents, from socialist Sjahrir to Islamic politicians Mohammad Natsir and Hamka. Using martial law powers, the government closed down newspapers that were critical of Sukarno's policies.

During this period, there were several assassination attempts on Sukarno's life. On 9 March 1960, Daniel Alexander Maukar, Daniel Maukar, an Indonesian airforce lieutenant who sympathised with the Permesta rebellion, strafed the Merdeka Palace and Bogor Palace with his MiG-17 fighter jet, attempting to kill the president; he was not injured. In May 1962, Darul Islam agents shot at the president during Eid al-Adha prayers on the grounds of the palace. Sukarno again escaped injury.

On the security front, the military started a series of effective campaigns which ended the long-festering Darul Islam rebellion in West Java (1962), Aceh (1962), and South Sulawesi (1965). Kartosuwirjo, the leader of Darul Islam, was captured and executed in September 1962.

To counterbalance the power of the military, Sukarno started to rely on the support of the PKI. In 1960, he declared his government to be based on Nasakom, a union of the three ideological strands present in Indonesian society: ''nasionalisme'' (nationalism), ''agama'' (religions), and ''komunisme'' (communism). Accordingly, Sukarno started admitting more communists into his government, while developing a strong relationship with the PKI chairman Dipa Nusantara Aidit.

In order to increase Indonesia's prestige, Sukarno supported and won the bid for the 1962 Asian Games held in Jakarta. Many sporting facilities such as the Senayan sports complex (including the 100,000-seat Bung Karno Stadium) were built to accommodate the games. There was political tension when the Indonesians refused the entry of delegations from Israel and Taiwan. After the International Olympic Committee imposed sanctions on Indonesia due to this exclusion policy, Sukarno retaliated by organizing a "non-imperialist" competitor event to the Olympic Games, called the ''Games of New Emerging Forces'' (GANEFO). GANEFO was successfully held in Jakarta in November 1963 and was attended by 2,700 athletes from 51 countries.

As part of his prestige-building program, Sukarno ordered the construction of large monumental buildings such as National Monument (Indonesia), National Monument (''Monumen Nasional''), Istiqlal Mosque, Jakarta, CONEFO Building (now the DPR/MPR Building, Parliament Building), Hotel Indonesia, and the Sarinah shopping centre to transform Jakarta from a former colonial backwater to a modern city. The modern Jakarta boulevards of Jalan Thamrin, Jalan Sudirman, and Jalan Gatot Subroto were planned and constructed under Sukarno.

With the backing of the military, Sukarno disbanded the Islamic party Masyumi and Sutan Sjahrir's party Socialist Party of Indonesia, PSI, accusing them of involvement with PRRI-Permesta affair. The military arrested and imprisoned many of Sukarno's political opponents, from socialist Sjahrir to Islamic politicians Mohammad Natsir and Hamka. Using martial law powers, the government closed down newspapers that were critical of Sukarno's policies.

During this period, there were several assassination attempts on Sukarno's life. On 9 March 1960, Daniel Alexander Maukar, Daniel Maukar, an Indonesian airforce lieutenant who sympathised with the Permesta rebellion, strafed the Merdeka Palace and Bogor Palace with his MiG-17 fighter jet, attempting to kill the president; he was not injured. In May 1962, Darul Islam agents shot at the president during Eid al-Adha prayers on the grounds of the palace. Sukarno again escaped injury.

On the security front, the military started a series of effective campaigns which ended the long-festering Darul Islam rebellion in West Java (1962), Aceh (1962), and South Sulawesi (1965). Kartosuwirjo, the leader of Darul Islam, was captured and executed in September 1962.

To counterbalance the power of the military, Sukarno started to rely on the support of the PKI. In 1960, he declared his government to be based on Nasakom, a union of the three ideological strands present in Indonesian society: ''nasionalisme'' (nationalism), ''agama'' (religions), and ''komunisme'' (communism). Accordingly, Sukarno started admitting more communists into his government, while developing a strong relationship with the PKI chairman Dipa Nusantara Aidit.

In order to increase Indonesia's prestige, Sukarno supported and won the bid for the 1962 Asian Games held in Jakarta. Many sporting facilities such as the Senayan sports complex (including the 100,000-seat Bung Karno Stadium) were built to accommodate the games. There was political tension when the Indonesians refused the entry of delegations from Israel and Taiwan. After the International Olympic Committee imposed sanctions on Indonesia due to this exclusion policy, Sukarno retaliated by organizing a "non-imperialist" competitor event to the Olympic Games, called the ''Games of New Emerging Forces'' (GANEFO). GANEFO was successfully held in Jakarta in November 1963 and was attended by 2,700 athletes from 51 countries.

As part of his prestige-building program, Sukarno ordered the construction of large monumental buildings such as National Monument (Indonesia), National Monument (''Monumen Nasional''), Istiqlal Mosque, Jakarta, CONEFO Building (now the DPR/MPR Building, Parliament Building), Hotel Indonesia, and the Sarinah shopping centre to transform Jakarta from a former colonial backwater to a modern city. The modern Jakarta boulevards of Jalan Thamrin, Jalan Sudirman, and Jalan Gatot Subroto were planned and constructed under Sukarno.

Foreign policy

Bandung Conference

On the international front, Sukarno organized the Bandung Conference in 1955, with the goal of uniting the developing Asian and African countries into theCold War

As Sukarno's domestic authority was secured, he began to pay more attention to the world stage. He embarked on a series of aggressive and assertive policies based onPapua conflict

In 1960 Sukarno began an aggressive foreign policy to secure Indonesian territorial claims. In August of that year, he broke off diplomatic relations with the Netherlands over the continuing failure to commence talks on the future of Netherlands New Guinea, as was agreed at the Dutch-Indonesian Round Table Conference of 1949. In April 1961, the Dutch announced the formation of a ''Nieuw Guinea Raad'', intending to create an independent Papua New Guinea, Papuan state. Sukarno declared a state of military confrontation in his ''Operation Trikora, Tri Komando Rakjat'' (TRIKORA) speech in Yogyakarta, on 19 December 1961. He then directed military incursions into the half-island, which he referred to as West Irian. By the end of 1962, 3,000 Indonesian soldiers were present throughout West Irian/West Papua.

On 28 August 1961, Elizabeth II invited Sukarno for a state visit to London which was scheduled in May 1962. But on 19 September, Juliana of the Netherlands, who heard the news, felt unhappy due to the breakdown of Indonesia's diplomatic relations with the Netherlands after the West Irian dispute. Upon hearing the news, she stated that negotiations with Indonesia regarding West Irian would not take place and did not allow Elizabeth, who was still her distant niece, to invite Sukarno, which resulted in a worsening of Indonesia's diplomatic relations with the

In 1960 Sukarno began an aggressive foreign policy to secure Indonesian territorial claims. In August of that year, he broke off diplomatic relations with the Netherlands over the continuing failure to commence talks on the future of Netherlands New Guinea, as was agreed at the Dutch-Indonesian Round Table Conference of 1949. In April 1961, the Dutch announced the formation of a ''Nieuw Guinea Raad'', intending to create an independent Papua New Guinea, Papuan state. Sukarno declared a state of military confrontation in his ''Operation Trikora, Tri Komando Rakjat'' (TRIKORA) speech in Yogyakarta, on 19 December 1961. He then directed military incursions into the half-island, which he referred to as West Irian. By the end of 1962, 3,000 Indonesian soldiers were present throughout West Irian/West Papua.

On 28 August 1961, Elizabeth II invited Sukarno for a state visit to London which was scheduled in May 1962. But on 19 September, Juliana of the Netherlands, who heard the news, felt unhappy due to the breakdown of Indonesia's diplomatic relations with the Netherlands after the West Irian dispute. Upon hearing the news, she stated that negotiations with Indonesia regarding West Irian would not take place and did not allow Elizabeth, who was still her distant niece, to invite Sukarno, which resulted in a worsening of Indonesia's diplomatic relations with the ''Konfrontasi''

After securing control over West Irian/West Papua, Sukarno then opposed the British-supported establishment of the Malaysia, Federation of Malaysia in 1963, claiming that it was a neo-colonial plot by the British to undermine Indonesia. Despite Sukarno's political overtures, which found some support when leftist political elements in British Borneo territories Sarawak and Brunei opposed the Federation plan and aligned themselves with Sukarno, Malaysia was established in September 1963. This was followed by the Indonesia–Malaysia confrontation (''Konfrontasi''), proclaimed by Sukarno in his ''Dwi Komando Rakjat'' (DWIKORA) speech in Jakarta on 3 May 1964. Sukarno's proclaimed objective was not, as some alleged, to annex Sabah and Sarawak into Indonesia, but to establish a "State of North Kalimantan" under the control of the North Kalimantan Communist Party. From 1964 until early 1966, a limited number of Indonesian soldiers, civilians, and Malaysian communist guerrillas were sent into North Borneo and the Malay Peninsula. These forces fought against British and Commonwealth soldiers deployed to protect the nascent state of Malaysia. Indonesian agents also exploded several bombs in Singapore. Domestically, Sukarno fomented anti-British sentiment, and the British Embassy was burned down. In 1964, all British companies operating in the country, including Indonesian operations of the Chartered Bank and Unilever, were nationalised. The confrontation came to a climax during August 1964, when Sukarno authorised landings of Indonesian troops at Landing at Pontian, Pontian and Landing at Labis, Labis on the Malaysian mainland, and all-out war seemed inevitable as tensions escalated. However, the situation calmed by mid-September at the culmination of the Sunda Straits Crisis, and after the disastrous Battle of Plaman Mapu in April 1965, Indonesian raids into Sarawak became fewer and weaker.

In 1964, Sukarno commenced an anti-American campaign, which was motivated by his shift towards the communist bloc and less friendly relations with the Presidency of Lyndon B. Johnson, Lyndon Johnson administration. American interests and businesses in Indonesia were denounced by government officials and attacked by PKI-led mobs. American movies were banned, American books and Beatles albums were burned, and the Indonesian band Koes Plus was jailed for playing American-style rock and roll music. As a result, USA aid to Indonesia was halted, to which Sukarno made his famous remark "Go to hell with your aid". Sukarno withdrew Indonesia from the United Nations on 7 January 1965 when, with U.S. backing, Malaysia took a seat on the UN Security Council.

After securing control over West Irian/West Papua, Sukarno then opposed the British-supported establishment of the Malaysia, Federation of Malaysia in 1963, claiming that it was a neo-colonial plot by the British to undermine Indonesia. Despite Sukarno's political overtures, which found some support when leftist political elements in British Borneo territories Sarawak and Brunei opposed the Federation plan and aligned themselves with Sukarno, Malaysia was established in September 1963. This was followed by the Indonesia–Malaysia confrontation (''Konfrontasi''), proclaimed by Sukarno in his ''Dwi Komando Rakjat'' (DWIKORA) speech in Jakarta on 3 May 1964. Sukarno's proclaimed objective was not, as some alleged, to annex Sabah and Sarawak into Indonesia, but to establish a "State of North Kalimantan" under the control of the North Kalimantan Communist Party. From 1964 until early 1966, a limited number of Indonesian soldiers, civilians, and Malaysian communist guerrillas were sent into North Borneo and the Malay Peninsula. These forces fought against British and Commonwealth soldiers deployed to protect the nascent state of Malaysia. Indonesian agents also exploded several bombs in Singapore. Domestically, Sukarno fomented anti-British sentiment, and the British Embassy was burned down. In 1964, all British companies operating in the country, including Indonesian operations of the Chartered Bank and Unilever, were nationalised. The confrontation came to a climax during August 1964, when Sukarno authorised landings of Indonesian troops at Landing at Pontian, Pontian and Landing at Labis, Labis on the Malaysian mainland, and all-out war seemed inevitable as tensions escalated. However, the situation calmed by mid-September at the culmination of the Sunda Straits Crisis, and after the disastrous Battle of Plaman Mapu in April 1965, Indonesian raids into Sarawak became fewer and weaker.

In 1964, Sukarno commenced an anti-American campaign, which was motivated by his shift towards the communist bloc and less friendly relations with the Presidency of Lyndon B. Johnson, Lyndon Johnson administration. American interests and businesses in Indonesia were denounced by government officials and attacked by PKI-led mobs. American movies were banned, American books and Beatles albums were burned, and the Indonesian band Koes Plus was jailed for playing American-style rock and roll music. As a result, USA aid to Indonesia was halted, to which Sukarno made his famous remark "Go to hell with your aid". Sukarno withdrew Indonesia from the United Nations on 7 January 1965 when, with U.S. backing, Malaysia took a seat on the UN Security Council.

Conference of the New Emerging Forces

As the NAM countries were splitting into different factions, and as fewer countries were willing to support his anti-Western foreign policies, Sukarno began to abandon his non-alignment rhetoric. Sukarno formed a new alliance with China, North Korea, North Vietnam, and Kingdom of Cambodia (1953–1970), Cambodia which he called the "Beijing-Pyongyang-Hanoi-Phnom Penh-Jakarta Axis". After withdrawing Indonesia from the "imperialist-dominated" United Nations in January 1965, Sukarno sought to establish a competitor organisation to the UN called the CONEFO, Conference of the New Emerging Forces (CONEFO) with support from the People's Republic of China, which at that time was China and the United Nations, not yet a member of United Nations. With the government heavily indebted to the Soviet Union, Indonesia became increasingly dependent on China for support.Hughes (2002), p. 21 Sukarno spoke increasingly of a Beijing-Jakarta axis, which would be the core of a new anti-imperialist world organization, the CONEFO.Domestic policy

President for life and personality cult

Domestically, Sukarno continued to consolidate his control. On 18 May 1963, the MPRS 1963 Indonesian presidential election, elected Sukarno president for life. His ideological writings on Manipol-USDEK and Nasakom became mandatory subjects in schools and universities, while his speeches were to be memorised and discussed by all students. All newspapers, the only radio station (Radio Republik Indonesia, RRI, government-run), and the only television station (TVRI, also government-run) were made into "tools of the revolution" and functioned to spread Sukarno's messages. Sukarno developed a personality cult, with the capital of newly acquired Western New Guinea, West Irian renamed to Jayapura, Sukarnapura and the highest peak in the country was renamed from Carstensz Pyramid to Puncak Jaya, Puntjak Sukarno (Sukarno Peak).Rise of the PKI

Despite these appearances of unchallenged control, Sukarno's guided democracy stood on fragile grounds due to the inherent conflict between its two underlying support pillars, the military and the communists. The military, nationalists, and the Islamic groups were shocked by the rapid growth of the communist party under Sukarno's protection. They feared an imminent establishment of a communist state in Indonesia. By 1965, the PKI had three million members and were particularly strong in Central Java and Bali. The PKI had become the strongest party in Indonesia. The military and nationalists were growing wary of Sukarno's close alliance with communist China, which they thought compromised Indonesia's sovereignty. Elements of the military disagreed with Sukarno's policy of confrontation with Malaysia, which in their view only benefited communists, and sent several officers (including future armed forces Chief L. B. Moerdani, Leonardus Benjamin Moerdani) to spread secret peace-feelers to the Malaysian government. The Islamic clerics, who were mostly landowners, felt threatened by PKI's land confiscation actions () in the countryside and by the communist campaign against the "seven village devils", a term used for landlords or better-off farmers (similar to the anti-kulak campaign in Stalinism, Stalinist era). Both groups harboured deep disdain for PKI in particular due to memories of the bloody Madiun Affair, 1948 communist rebellion. As the mediator of the three groups under the NASAKOM system, Sukarno displayed greater sympathies to the communists. The PKI had been very careful to support all of Sukarno's policies. Meanwhile, Sukarno saw the PKI as the best-organized and ideologically solid party in Indonesia, and a useful conduit to gain more military and financial aid from Eastern Bloc, Communist Bloc countries. Sukarno also sympathised with the communists' revolutionary ideals, which were similar to his own. To weaken the influence of the military, Sukarno rescinded martial law (which gave wide-ranging powers to the military) in 1963. In September 1962, he "promoted" the powerful General Nasution to the less-influential position of armed forces chief, while the influential position of army chief was given to Sukarno's loyalist Ahmad Yani. Meanwhile, the position of air force chief was given to Omar Dhani, who was an open communist sympathiser. In May 1964, Sukarno banned the activities of (Manikebu), an association of artists and writers which included prominent Indonesian writers such as Hans Bague Jassin and Wiratmo Soekito, who were also dismissed from their jobs. Manikebu was considered a rival by the communist writer's association (Lekra), led by Pramoedya Ananta Toer. In December 1964, Sukarno disbanded the (BPS, "Association for Promoting Sukarnoism"), an organization that sought to oppose communism by invoking Sukarno's own Pancasila formulation. In January 1965, Sukarno, under pressure from the PKI, banned the Murba Party. Murba was a pro-Soviet Union party whose ideology was antagonistic to the PKI's pro-Chinese People's Republic view of Marxism. Tensions between the military and communists increased in April 1965, when PKI chairman Aidit called for the formation of a "Fifth Force (Indonesia), fifth armed force" consisting of armed peasants and labourers. Sukarno approved this idea and publicly called for the immediate formation of such a force on 17 May 1965. However, Army Chief Ahmad Yani and Defense Minister Nasution procrastinated in implementing this idea, as this was tantamount to allowing the PKI to establish its own armed forces. Soon afterwards, on 29 May, the "Gilchrist Document, Gilchrist Letter" appeared. The letter was supposedly written by the British ambassador Andrew Gilchrist to the Foreign Office in London, mentioning a joint American and British attempt on subversion in Indonesia with the help of "local army friends." This letter, produced by Subandrio, aroused Sukarno's fear of a military plot to overthrow him, a fear which he repeatedly mentioned during the next few months. The Czechoslovakian agent Ladislav Bittman, who defected in 1968, claimed that his agency (StB) forged the letter on request from PKI via the Soviet Union to smear anti-communist generals. On his independence day speech of 17 August 1965, Sukarno declared his intention to commit Indonesia to an anti-imperialist alliance with China and other communist regimes and warned the army not to interfere. He also stated his support for the establishment of a "fifth force" of armed peasants and labourers.Economic decline

While Sukarno devoted his energy to domestic and international politics, the economy of Indonesia was neglected and deteriorated rapidly. The government printed money to finance its military expenditures, resulting in hyperinflation exceeding 600% per annum in 1964–1965. Smuggling and the collapse of export plantation sectors deprived the government of much-needed foreign exchange income. Consequently, the government was unable to service massive foreign debts it had accumulated from both Western and Communist bloc countries. Most of the government budget was spent on the military, resulting in deterioration of infrastructures such as roads, railways, ports, and other public facilities. Deteriorating transportation infrastructure and poor harvests caused food shortages in many places. The small industrial sector languished and only produced at 20% capacity due to lack of investment. Sukarno himself was contemptuous of macroeconomics and was unable and unwilling to provide practical solutions to the poor economic condition of the country. Instead, he produced more ideological conceptions such as ''Trisakti'': political sovereignty, economic self-sufficiency, and cultural independence. He advocated Indonesians "standing on their own feet" (''Berdikari'') and achieving economic self-sufficiency, free from foreign influence. Towards the end of his rule, Sukarno's lack of interest in economics created a distance between himself and the Indonesian people, who were suffering economically.Removal from power and death

30 September Movement

Kidnappings and murders

On the dawn of 1 October 1965, six of Indonesia's most senior army generals were kidnapping, kidnapped and murdered by a movement calling themselves the "The end of the movement

Major General Suharto, commander of the military's strategic reserve command, took control of the army the following morning. Suharto ordered troops to take over the RRI radio station and Merdeka Square itself. On the afternoon of that day, Suharto issued an ultimatum to the Halim Perdanakusuma International Airport, Halim Air Force Base, where the G30S had based themselves and where Sukarno (the reasons for his presence are unclear and were subject of claim and counter-claim), Air Marshal Omar Dhani, and PKI Chairman Aidit had gathered. By the following day, it was clear that the incompetently organized and poorly coordinated coup had failed. Sukarno took up residence in the Bogor Palace, while Dhani fled to East Java and Aidit to Central Java.Ricklefs (1991), pp. 281–282. By 2 October, Suharto's soldiers occupied Halim Air Force Base, after a short gunfight. Sukarno's obedience to Suharto's 1 October ultimatum to leave Halim is seen as changing all power relationships. Sukarno's fragile balance of power between the military, political Islam, communists and nationalists that underlay his " Guided Democracy" was now collapsing. On 3 October, the corpses of the kidnapped generals were discovered near the Halim Air Force Base, and on 5 October they were buried in a public ceremony led by Suharto.Aftermath of the movement

In early October 1965, a military propaganda campaign began to sweep the country, successfully convincing both Indonesian and international audiences that it was a communist coup, and that the murders were cowardly atrocities against Indonesian heroes since those who were shot were veteran military officers.Vickers (2005), p. 157. PKI's denials of involvement had little effect.Ricklefs (1991), p. 287. Following the discovery and public burial of the generals' corpses on 5 October, the army along with Islamic organizations Muhammadiyah and Nahdlatul Ulama led a campaign to purge Indonesian society, government and armed forces of the communist party and other leftist organizations. Leading PKI members were immediately arrested, some summarily executed. Aidit was captured and killed in November 1965. Indonesian killings of 1965–66, The purge spread across the country with the worst massacres in Java and Bali. In some areas, the army organized civilian groups and local militias, in other areas communal vigilante action preceded the army. The most widely accepted estimates are that at least half a million were killed. It is thought that as many as 1.5 million were imprisoned at one stage or another. As a result of the purge, one of Sukarno's three pillars of support, the PKI, had been effectively eliminated by the other two, the military and political Islam. The killings and the failure of his tenuous "revolution" distressed Sukarno, and he tried unsuccessfully to protect the PKI by referring to the generals' killings as ("ripple in the sea of the revolution"). He tried to maintain his influence by appealing in a January 1966 broadcast for the country to follow him. Subandrio sought to create a Sukarnoist column (), which was undermined by Suharto's pledge of loyalty to Sukarno and the concurrent instruction for all those loyal to Sukarno to announce their support for the army.Transition to the New Order

Cabinet reshuffle

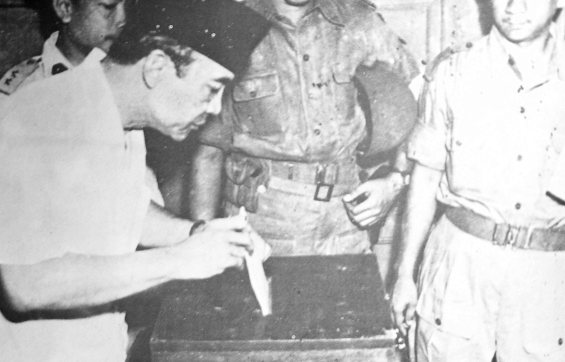

On 1 October 1965, Sukarno appointed General Pranoto Reksosamudro as army chief to replace the deceased Yani, but he was forced to give this position to Suharto two weeks later. In February 1966, Sukarno reshuffled his cabinet, sacking Nasution as defense minister and abolishing his position of armed forces chief of staff, but Nasution refused to step down. Beginning in January 1966, university students started demonstrating against Sukarno, demanding the disbandment of PKI and for the government to control spiralling inflation. In February 1966, student demonstrators in front of Merdeka Palace were shot at by Presidential Guards, killing the student Arief Rachman Hakim, who was quickly turned into a martyr by student demonstrators.''Supersemar''

A meeting of Sukarno's full cabinet was held at the Merdeka Palace on 11 March 1966. As students were demonstrating against the administration, unidentified troops began to assemble outside. Sukarno, Subandrio and another minister immediately left the meeting and went to the Bogor Palace by helicopter. Three pro-Suharto generals (Basuki Rahmat, Amir Machmud, and Mohammad Jusuf) were dispatched to the Bogor Palace, and they met with Sukarno, who signed for them a Presidential Order known as ''Supersemar''. Through the order, Sukarno assigned Suharto to "take all measures considered necessary to guarantee security, calm and stability of the government and the revolution and to guarantee the personal safety and authority [of Sukarno]". The authorship of the document, and whether Sukarno was forced to sign, perhaps even at gunpoint, is a point of historical debate. The effect of the order, however, was the transfer of most presidential authority to Suharto. After obtaining the Presidential Order, Suharto had the PKI declared illegal, and the party was abolished. He also arrested many high-ranking officials that were loyal to Sukarno on the charge of being PKI members and/or sympathizers, further reducing Sukarno's political power and influence.House arrest and death

On 22 June 1966, Sukarno made his ''Nawaksara'' speech in front of the MPRS, now purged of communist and pro-Sukarno elements, in an unsuccessful last-ditch attempt to defend himself and his guided democracy system. In August 1966, over Sukarno's objections, Indonesia ended its confrontation with Malaysia and rejoined the United Nations. Following another unsuccessful accountability speech (''Nawaksara'' Addendum) on 10 January 1967, Sukarno relinquished his executive powers to Suharto on 20 February 1967 while remaining nominally as titular president. He was finally stripped of his president for life title by the MPRS on 12 March 1967 in a session chaired by his former ally, Nasution. On the same day, the MPR named Suharto acting president.Ricklefs (1991), p. 295. Sukarno was put underPolitical rehabilitation

On 9 September 2024, the People's Consultative Assembly, MPR officially revoked MPR Resolution No. XXXIII/MPRS/1967 that was used as an instrument to revoke Sukarno from presidency and barred him from politics. Since there was no trial to prove that Sukarno is responsible to G30S/PKI, MPR revoked the resolution and resolved to restore his reputation posthumously.Personal life

Marriages

Sukarno was of Javanese and Balinese people, Balinese descent. He married Siti Oetari in 1921, and divorced her in 1923 to marry Inggit Garnasih, whom he divorced in about 1943 to marry Fatmawati. In 1953, Sukarno married Hartini, a 30-year-old widow from Salatiga, whom he met during a reception. Fatmawati was outraged by this fourth marriage and left Sukarno and their children, although they never officially divorced. In 1958, Sukarno married Maharani Wisma Susana Siregar, an independence veteran from Liverpool who was 23 years his junior, and divorced in 1962. he was introduced to the then 19-year-old Japanese hostess Naoko Nemoto, whom he married in 1962 and renamed Dewi Sukarno, Ratna Dewi Sukarno. Sukarno also had five other spouses: Sakiko Kanase (1958–1959), Kartini Manoppo (1959–1968), Haryati (1963–1966), Yurike Sanger (1964–1968), and Heldy Djafar (1966–1969). Sukarno was known for his relationships with several women such as Gusti Nurul, Baby Huwae, Nurbani Yusuf, and Amelia De La Rama. In 1964, he married Rama in Jakarta and remained with her until his death in 1970. The marriage was kept as a secret until Rama mentioned it during an interview in 1979.Children

Before his marriage to Fatmawati, Sukarno was married and had a daughter, Rukmini Sukarno, Rukmini, who later became an opera singer in Italy. Megawati Sukarnoputri, who served as the fifth president of Indonesia, is his daughter by his wife Fatmawati. Her younger brother Guruh Sukarnoputra (born 1953) has inherited Sukarno's artistic bent and is a choreographer and songwriter, who made a movie (''For You, My Indonesia'') about Indonesian culture. He is also a member of the Indonesian People's Representative Council for Megawati's Indonesian Democratic Party of Struggle. His siblings Guntur Sukarnoputra, Rachmawati Sukarnoputri, and Sukmawati Sukarnoputri have all been active in politics. Sukarno had a daughter named Kartika by Dewi Sukarno. In 2006, Kartika Sukarno married Frits Seegers, the Netherlands-born chief executive officer of the Barclays Global Retail and Commercial Bank. Other children include Taufan and Bayu by his wife Hartini, a son named Totok Suryawan Sukarnoputra (born 1967, in Germany), by his wife Kartini Manoppo, and a daughter, Siti Aisyah Margaret Rose, by his wife Maharani Wisma Susana Siregar.Honours

Sukarno was awarded twenty-six honorary doctorates from various international universities including Columbia University, the University of Michigan, the University of Berlin, the Al-Azhar University, the University of Belgrade, the Lomonosov University and many more, and also from domestic universities including Gadjah Mada University, the University of Indonesia, the Bandung Institute of Technology, Hasanuddin University, and Padjadjaran University. He was often referred to by the Indonesian government at the time as 'Dr. Ir. Soekarno,' combined with his degree in civil engineering (Ingenieur, Ir.) from Bandung Institute of Technology.

Sukarno was awarded twenty-six honorary doctorates from various international universities including Columbia University, the University of Michigan, the University of Berlin, the Al-Azhar University, the University of Belgrade, the Lomonosov University and many more, and also from domestic universities including Gadjah Mada University, the University of Indonesia, the Bandung Institute of Technology, Hasanuddin University, and Padjadjaran University. He was often referred to by the Indonesian government at the time as 'Dr. Ir. Soekarno,' combined with his degree in civil engineering (Ingenieur, Ir.) from Bandung Institute of Technology.

National honours

* The Sacred Star ()

*

The Sacred Star ()

*  Guerrilla Star ()

*

Guerrilla Star ()

*  Garuda Star ()

* Indonesian Armed Forces 8 Years of Service Star ()

* Independence Freedom Fighters Medal ()

Garuda Star ()

* Indonesian Armed Forces 8 Years of Service Star ()

* Independence Freedom Fighters Medal ()

Foreign honours

: * Collar of the Order of the Supreme Sun (1961) : * Grand Cross of the Order of the Condor of the Andes

:

*

Grand Cross of the Order of the Condor of the Andes

:

*  Order of Georgi Dimitrov

:

*

Order of Georgi Dimitrov

:

*  Grand Cordon of the Order of the Throne (1960)

:

*

Grand Cordon of the Order of the Throne (1960)

:

*  Resistance Medal, 1st Class

:

*

Resistance Medal, 1st Class

:

*  Great Star of the Order of the Yugoslav Star

Great Star of the Order of the Yugoslav Star

In popular culture

Books

* ''Kuantar Ke Gerbang'', an Indonesian novel by Ramadhan KH, tells the story of the romantic relationship between Sukarno and Inggit Garnasih, his second wife. * ''Sukarno: An Autobiography'' by Cindy Adams (Bobbs-Merrill, 1965): "Autobiography" written by the American writer with the cooperation of Sukarno. Translated into Indonesian by Abdul Bar Salim as ''Bung Karno: Penjambung Lidah Rakjat Indonesia'' (Gunung Agung, 1966). * ''My Friend the Dictator'' by Cindy Adams (Bobbs-Merrill, 1967): A contemporary account of the writing of the autobiography. * ''Nationalism, Islam and Marxism'', On his political concept "Nasakom"; collection of articles, 1926. Translated by Karel H. Warouw and Peter D. Weldon (Modern Indonesia Project, Ithaca, New York, 1970). * ''Indonesia vs Fasisme'', Analysis on Indonesian nationalism versus fascism; collection of articles, 1941 (Pen. Media Pressindo, Yogyakarta, 2000).Songs

* A song titled ''Untuk Paduka Jang Mulia Presiden Sukarno'' (To His Excellency President Sukarno) was written in early 60s by Soetedjo and popularised by Lilis Suryani, a famous Indonesian female soloist. The lyrics are full of expression of praise and gratitude to the then president for life.Movies

* Filipino people, Filipino actor Mike Emperio portrayed Sukarno in the 1982 movie ''The Year of Living Dangerously (film), The Year of Living Dangerously'', directed by Peter Weir based on a The Year of Living Dangerously (novel), novel of same name by Christopher Koch. * Indonesian sociologist and writer Umar Kayam portrayed Sukarno in the 1984 movie ''Pengkhianatan G30S/PKI'' and the 1988 movie ''Djakarta 66'', both directed by Arifin C. Noer. * Indonesian actor Frans Tumbuan portrayed Sukarno in the 1997 movie ''Blanco, The Colour of Love'' (compacted from its original TV serial version, ''Api Cinta Antonio Blanco'') about Spanish painter Antonio Blanco (painter), Antonio Blanco who settled and resided in Bali,See also

* Asian-African Conference * History of Indonesia * Withdrawal from the United Nations#Indonesian withdrawal, Withdrawal of Indonesia from UN * Cold War in Asia#IndonesiaNotes

References

Further reading

* Bob Hering, 2001, ''Soekarno, architect of a nation, 1901–1970'', KIT Publishers Amsterdam, , KITLV Leiden, * Jones, Matthew. "US relations with Indonesia, the Kennedy-Johnson transition, and the Vietnam connection, 1963–1965". ''Diplomatic History'' 26.2 (2002): 249–281online

* Brands, H.W. "The limits of Manipulation: How the United States didn't topple Koesno Sosrodihardjo". ''Journal of American History'' 76.3 (1989): 785–808

online

* Hughes, John (2002), ''The End of Sukarno – A Coup that Misfired: A Purge that Ran Wild'', Archipelago Press, * Oei Tjoe Tat, 1995, Memoar Oei Tjoe Tat: Pembantu Presiden Soekarno (The memoir of Oei Tjoe Tat, assistant to President Sukarno), Hasta Mitra, (banned in Indonesia) * Lambert J. Giebels, 1999, ''Soekarno. Nederlandsch onderdaan. Biografie 1901–1950''. Biography part 1, Bert Bakker Amsterdam, * Lambert J. Giebels, 2001, ''Soekarno. President, 1950–1970'', Biography part 2, Bert Bakker Amsterdam, geb., pbk. * Lambert J. Giebels, 2005, ''De stille genocide: de fatale gebeurtenissen rond de val van de Indonesische president Soekarno'', * * Quah, Say Jye. 2025. "doi:10.1111/ajps.12963, An anatomy of worldmaking: Sukarno and anticolonialism from post-Bandung Indonesia". ''American Journal of Political Science''. * * Panitia Nasional Penyelenggara Peringatan HUT Kemerdekaan RI ke-XXX (National Committee on 30th Indonesian Independence Anniversary), 1979, ''30 Tahun Indonesia Merdeka (I: 1945–1949)'' (30 Years of Independent Indonesia (Part I:1945–1949)), Tira Pustaka, Jakarta

External links

WWW-VL WWW-VL History: Indonesia

xtensive list of online reading on Sukarno

The Official U.S. position on released CIA documents

* {{Authority control Sukarno, 1901 births 1970 deaths 20th-century rebels Articles containing video clips Balinese people Bandung Institute of Technology alumni BPUPK Collars of the Order of the White Lion Deaths from kidney failure in Indonesia Political prisoners in the Netherlands Grand Crosses Special Class of the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany Heads of government who were later imprisoned Indonesian independence activists Indonesian Muslims Indonesian National Awakening Indonesian nationalists Indonesian revolutionaries Indonesian socialists Indonesian people who died in prison custody Javanese people Leaders ousted by a coup Recipients of the Lenin Peace Prize Members of the Central Advisory Council Muslim socialists National Heroes of Indonesia People from Blitar People from Surabaya People of the Indonesian National Revolution Politicians from East Java People from Grobogan Regency PPKI Prisoners who died in Indonesian detention Presidents for life Presidents of Indonesia Recipients of the Order of the Companions of O. R. Tambo Politicians from Central Java Recipients of the Order of the Sacred Treasure, 4th class Family of Sukarno