Subjective experience on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

In

In

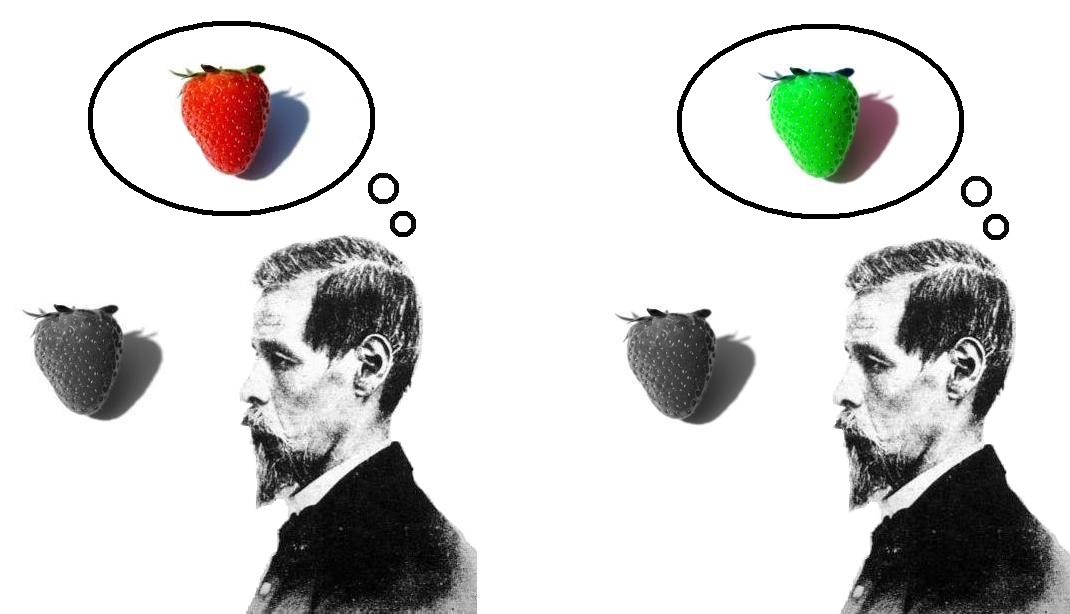

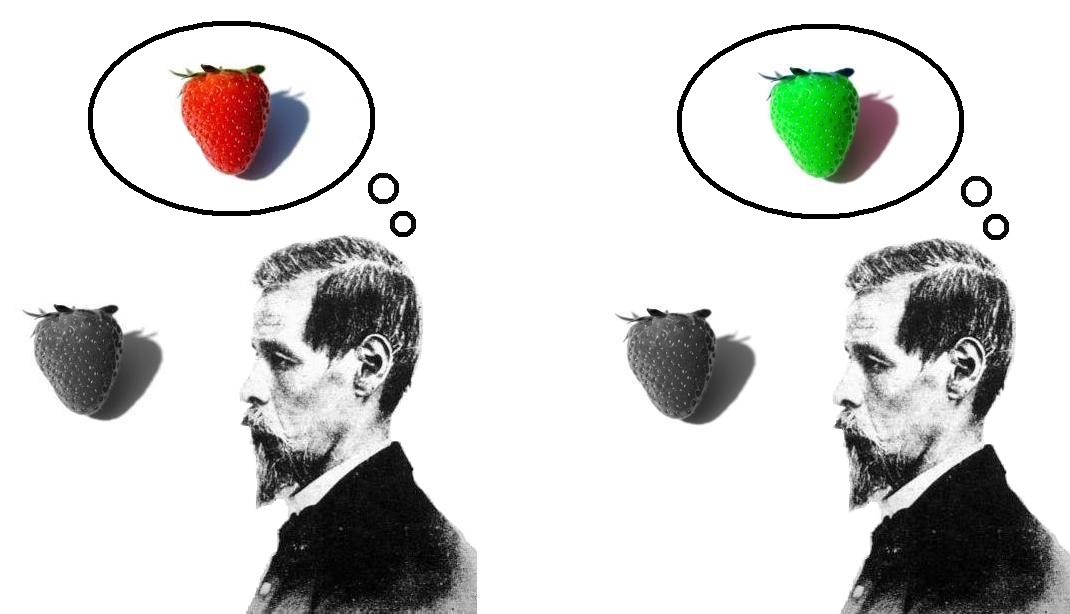

The inverted spectrum thought experiment, originally developed by

The inverted spectrum thought experiment, originally developed by

American philosopher Thomas Nagel's paper '' What Is it Like to Be a Bat?'' is often cited in debates about qualia, though it does not use the word "qualia". Nagel argues that consciousness has an essentially subjective character, a what-it-is-like aspect. He states that "an organism has conscious mental states if and only if there is something that it is like to ''be'' that organism – something it is like ''for'' the organism." Nagel suggests that this subjective aspect may never be sufficiently accounted for by the objective methods of reductionistic science. He claims that "if we acknowledge that a physical theory of mind must account for the subjective character of experience, we must admit that no presently available conception gives us a clue about how this could be done." Furthermore, "it seems unlikely that any physical theory of mind can be contemplated until more thought has been given to the general problem of subjective and objective."

American philosopher Thomas Nagel's paper '' What Is it Like to Be a Bat?'' is often cited in debates about qualia, though it does not use the word "qualia". Nagel argues that consciousness has an essentially subjective character, a what-it-is-like aspect. He states that "an organism has conscious mental states if and only if there is something that it is like to ''be'' that organism – something it is like ''for'' the organism." Nagel suggests that this subjective aspect may never be sufficiently accounted for by the objective methods of reductionistic science. He claims that "if we acknowledge that a physical theory of mind must account for the subjective character of experience, we must admit that no presently available conception gives us a clue about how this could be done." Furthermore, "it seems unlikely that any physical theory of mind can be contemplated until more thought has been given to the general problem of subjective and objective."

Vilayanur S. Ramachandran and William Hirstein proposed three laws of qualia (with a fourth later added), which are "functional criteria that need to be fulfilled in order for certain neural events to be associated with qualia" by philosophers of the mind:

These authors approach qualia from an empirical perspective and not as a logical or philosophical problem. They wonder how qualia evolved, and in doing so consider a skeptical point of view in which, since the objective scientific description of the world is complete without qualia, it is nonsense to ask why they evolved or what they are for. However they decide against this skeptical view.

Based on the parsimony principle of Occam's razor, one could accept epiphenomenalism and deny qualia, since they are not necessary for a description of the functioning of the brain. However, they argue that Occam's razor is not useful for scientific discovery. For example, the discovery of relativity in physics was not the product of accepting Occam's razor but rather of rejecting it and asking the question of whether a deeper generalization, not required by the currently available data, was true and would allow for unexpected predictions. Most scientific discoveries arise, these authors argue, from ontologically promiscuous conjectures that do not come from current data.

The authors then point out that skepticism might be justified in the philosophical field, but that science is the wrong place for skepticism, such as asking if "your red is not my green" or if we can be logically certain that we are not dreaming. Science, these authors assert, deals with what is probably true, beyond reasonable doubt, not with what can be known with complete and absolute certainty. The authors say that most neuroscientists and even most psychologists dispute the very existence of the problem of qualia.

Vilayanur S. Ramachandran and William Hirstein proposed three laws of qualia (with a fourth later added), which are "functional criteria that need to be fulfilled in order for certain neural events to be associated with qualia" by philosophers of the mind:

These authors approach qualia from an empirical perspective and not as a logical or philosophical problem. They wonder how qualia evolved, and in doing so consider a skeptical point of view in which, since the objective scientific description of the world is complete without qualia, it is nonsense to ask why they evolved or what they are for. However they decide against this skeptical view.

Based on the parsimony principle of Occam's razor, one could accept epiphenomenalism and deny qualia, since they are not necessary for a description of the functioning of the brain. However, they argue that Occam's razor is not useful for scientific discovery. For example, the discovery of relativity in physics was not the product of accepting Occam's razor but rather of rejecting it and asking the question of whether a deeper generalization, not required by the currently available data, was true and would allow for unexpected predictions. Most scientific discoveries arise, these authors argue, from ontologically promiscuous conjectures that do not come from current data.

The authors then point out that skepticism might be justified in the philosophical field, but that science is the wrong place for skepticism, such as asking if "your red is not my green" or if we can be logically certain that we are not dreaming. Science, these authors assert, deals with what is probably true, beyond reasonable doubt, not with what can be known with complete and absolute certainty. The authors say that most neuroscientists and even most psychologists dispute the very existence of the problem of qualia.

Michael Tye believes there are no qualia, no "veils of perception" between us and the referents of our thought. He describes our experience of an object in the world as "transparent", meaning that no matter what private understandings and/or misunderstandings we may have of something, it is still there before us in reality. The idea that qualia intervene between ourselves and their origins he regards as a "massive error. That is just not credible. It seems totally implausible ..that visual experience is systematically misleading in this way." He continues: "the only objects of which you are aware are the external ones making up the scene before your eyes."

From this he concludes "that there are no such qualities of experiences. They are qualities of external surfaces (and volumes and films), if they are qualities of anything." Thus he believes we can take our experiences at face value since there is no fear of losing contact with the realness of physical objects.

In Tye's thought there is no question of qualia without information being contained within them; it is always "an awareness that" and always "representational". He characterizes the perception of children as a misperception of referents that are undoubtedly as present for them as they are for grown-ups. As he puts it, they may not know that "the house is dilapidated", but there is no doubt about their seeing the house. After-images are dismissed as presenting no problem for the ''transparency theory'' because, as he puts it, after-images being illusory, there is nothing that one sees.

Tye proposes that phenomenal experience has five basic elements, for which he has coined the acronym PANIC – Poised, Abstract, Nonconceptual, Intentional Content.

*''"Poised"'' - the phenomenal experience is always present to the understanding, whether or not the agent is able to apply a concept to it.

* ''"Abstract"'' - it is unclear whether you are in touch with a concrete object (for example, someone may feel a pain in an amputated limb).

*''"Nonconceptual"'' - phenomenon can exist although one does not have the concept by which to recognize it.

*''"Intentional (Content)"'' - it represents something, whether or not the observer is taking advantage of that fact.

Tye adds that the experience is like a map in that, in most cases, it goes beyond the shapes, edges, volumes, etc. in the world – you may not be reading the a map but, as with an actual map there is a reliable match with what it is mapping. This is why Tye calls his theory ''representationalism,'' makes it plain that Tye believes that he has retained a direct contact with what produces the phenomena and is therefore not hampered by any trace of a "veil of perception".

Michael Tye believes there are no qualia, no "veils of perception" between us and the referents of our thought. He describes our experience of an object in the world as "transparent", meaning that no matter what private understandings and/or misunderstandings we may have of something, it is still there before us in reality. The idea that qualia intervene between ourselves and their origins he regards as a "massive error. That is just not credible. It seems totally implausible ..that visual experience is systematically misleading in this way." He continues: "the only objects of which you are aware are the external ones making up the scene before your eyes."

From this he concludes "that there are no such qualities of experiences. They are qualities of external surfaces (and volumes and films), if they are qualities of anything." Thus he believes we can take our experiences at face value since there is no fear of losing contact with the realness of physical objects.

In Tye's thought there is no question of qualia without information being contained within them; it is always "an awareness that" and always "representational". He characterizes the perception of children as a misperception of referents that are undoubtedly as present for them as they are for grown-ups. As he puts it, they may not know that "the house is dilapidated", but there is no doubt about their seeing the house. After-images are dismissed as presenting no problem for the ''transparency theory'' because, as he puts it, after-images being illusory, there is nothing that one sees.

Tye proposes that phenomenal experience has five basic elements, for which he has coined the acronym PANIC – Poised, Abstract, Nonconceptual, Intentional Content.

*''"Poised"'' - the phenomenal experience is always present to the understanding, whether or not the agent is able to apply a concept to it.

* ''"Abstract"'' - it is unclear whether you are in touch with a concrete object (for example, someone may feel a pain in an amputated limb).

*''"Nonconceptual"'' - phenomenon can exist although one does not have the concept by which to recognize it.

*''"Intentional (Content)"'' - it represents something, whether or not the observer is taking advantage of that fact.

Tye adds that the experience is like a map in that, in most cases, it goes beyond the shapes, edges, volumes, etc. in the world – you may not be reading the a map but, as with an actual map there is a reliable match with what it is mapping. This is why Tye calls his theory ''representationalism,'' makes it plain that Tye believes that he has retained a direct contact with what produces the phenomena and is therefore not hampered by any trace of a "veil of perception".

In Chapter 1 of '' Philosophy and the Mirror of Nature'', Richard Rorty suggests that the concept of a quale is the result of a reification fallacy.

In attempting to answer the question "why is the phenomenal immaterial?", he notes that there is nothing to suggest that the phenomenal and the physical are anything more than two different ways of talking about the states or properties of people. Even if the appearance/reality distinction does not exist for phenomenal properties, the fact that self-attributions of such properties are typically considered incorrigible could simply reflect an epistemic distinction (he also hints at the idea that this incorrigibility could be a mere linguistic convention, which he develops more fully in Chapter 2). If this is the case, then Rorty claims that the problem of consciousness is not actually a real metaphysical problem:

In Chapter 1 of '' Philosophy and the Mirror of Nature'', Richard Rorty suggests that the concept of a quale is the result of a reification fallacy.

In attempting to answer the question "why is the phenomenal immaterial?", he notes that there is nothing to suggest that the phenomenal and the physical are anything more than two different ways of talking about the states or properties of people. Even if the appearance/reality distinction does not exist for phenomenal properties, the fact that self-attributions of such properties are typically considered incorrigible could simply reflect an epistemic distinction (he also hints at the idea that this incorrigibility could be a mere linguistic convention, which he develops more fully in Chapter 2). If this is the case, then Rorty claims that the problem of consciousness is not actually a real metaphysical problem:

philosophy of mind

Philosophy of mind is a branch of philosophy that deals with the nature of the mind and its relation to the Body (biology), body and the Reality, external world.

The mind–body problem is a paradigmatic issue in philosophy of mind, although a ...

, qualia (; singular: quale ) are defined as instances of subjective, conscious experience. The term ''qualia'' derives from the Latin

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins (Italic tribe), Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area aroun ...

neuter plural form (''qualia'') of the Latin adjective '' quālis'' () meaning "of what sort" or "of what kind" in relation to a specific instance, such as "what it is like to taste a specific this particular apple now".

Examples of qualia include the perceived sensation of ''pain'' of a headache, the ''taste'' of wine, and the ''redness'' of an evening sky. As qualitative characteristics of sensations, qualia stand in contrast to propositional attitude

A propositional attitude is a mental state held by an agent or organism toward a proposition. In philosophy, propositional attitudes can be considered to be neurally realized, causally efficacious, content-bearing internal states (personal princip ...

s, where the focus is on beliefs about experience rather than what it is directly like to be experiencing.

C.S. Peirce introduced the term ''quale'' in philosophy in 1866, and in 1929 C. I. Lewis was the first to use the term "qualia" in its generally agreed upon modern sense. Frank Jackson later defined qualia as "...certain features of the bodily sensations especially, but also of certain perceptual experiences, which no amount of purely physical information includes". Philosopher

Philosophy ('love of wisdom' in Ancient Greek) is a systematic study of general and fundamental questions concerning topics like existence, reason, knowledge, Value (ethics and social sciences), value, mind, and language. It is a rational an ...

and cognitive scientist Daniel Dennett suggested that ''qualia'' was "an unfamiliar term for something that could not be more familiar to each of us: the ways things seem to us".

The nature and existence of qualia under various definitions remain controversial. Much of the debate over the importance of qualia hinges on the definition of the term, and various philosophers emphasize or deny the existence of certain features of qualia. Some philosophers of mind, like Daniel Dennett, argue that qualia do not exist. Other philosophers, as well as neuroscientists and neurologists, believe qualia exist and that the desire by some philosophers to disregard qualia is based on an erroneous interpretation of what constitutes science.

Definitions

Many definitions of qualia have been proposed. One of the simpler, broader definitions is: "The 'what it is like' character of mental states. The way it feels to have mental states such as pain, seeing red, smelling a rose, etc." Leibniz's passage in his Monadology in 1714 described the explanatory gap as follows:It must be confessed, moreover, that perception, and that which depends on it, are inexplicable by mechanical causes, that is, by figures and motions. And, supposing that there were a mechanism so constructed as to think, feel and have perception, we might enter it as into a mill. And this granted, we should only find on visiting it, pieces which push one against another, but never anything by which to explain a perception. This must be sought, therefore, in the simple substance, and not in the composite or in the machine.

Charles Sanders Peirce

Charles Sanders Peirce ( ; September 10, 1839 – April 19, 1914) was an American scientist, mathematician, logician, and philosopher who is sometimes known as "the father of pragmatism". According to philosopher Paul Weiss (philosopher), Paul ...

introduced the term ''quale'' in philosophy in 1866, and in 1929 C.I. Lewis was the first to use the term "qualia" in its generally agreed upon modern sense.

Frank Jackson later defined qualia as "...certain features of the bodily sensations especially, but also of certain perceptual experiences, which no amount of purely physical information includes".

Daniel Dennett suggested that ''qualia'' was "an unfamiliar term for something that could not be more familiar to each of us: the ways things seem to us". He identifies four properties that are commonly ascribed to qualia. According to these, ''qualia'' are:

# '' ineffable'' – they cannot be communicated, or apprehended by any means other than direct experience.

# '' intrinsic'' – they are non-relational properties, which do not change depending on the experience's relation to other things.

# '' private'' – all interpersonal comparisons of qualia are systematically impossible.

# ''directly or immediately apprehensible by consciousness

Consciousness, at its simplest, is awareness of a state or object, either internal to oneself or in one's external environment. However, its nature has led to millennia of analyses, explanations, and debate among philosophers, scientists, an ...

'' – to experience a quale is to know one experiences a quale, and to know all there is to know about that quale.

If qualia of this sort exist, then a normally sighted person who sees red would be unable to describe the experience of this perception

Perception () is the organization, identification, and interpretation of sensory information in order to represent and understand the presented information or environment. All perception involves signals that go through the nervous syste ...

in such a way that a listener who has never experienced color will be able to know everything there is to know about that experience. Though it is possible to make an analogy, such as "red looks hot", or to provide a description of the conditions under which the experience occurs, such as "it's the color you see when light of 700- nm wavelength is directed at you", supporters of this definition of qualia contend that such descriptions cannot provide a complete description of the experience.

Another way of defining qualia is as "raw feels". A ''raw feel'' is a perception in and of itself, considered entirely in isolation from any effect it might have on behavior and behavioral disposition. In contrast, a ''cooked feel'' is that perception seen in terms of its effects. For example, the perception of the taste of wine is an ineffable, raw feel, while the behavioral reaction one has to the warmth or bitterness caused by that taste of wine would be a cooked feel. Cooked feels are not qualia.

Arguably, the idea of hedonistic utilitarianism, where the ethical value of things is determined from the amount of subjective pleasure or pain they cause, is dependent on the existence of qualia.

Arguments regarding the existence of qualia

Since, by definition, qualia cannot be fully conveyed verbally, they also cannot be demonstrated directly in an argument – a more nuanced approach is needed. Arguments for qualia generally come in the form ofthought experiment

A thought experiment is an imaginary scenario that is meant to elucidate or test an argument or theory. It is often an experiment that would be hard, impossible, or unethical to actually perform. It can also be an abstract hypothetical that is ...

s designed to lead one to the conclusion that qualia exist.

Modern philosophy

Inverted spectrum argument

The inverted spectrum thought experiment, originally developed by

The inverted spectrum thought experiment, originally developed by John Locke

John Locke (; 29 August 1632 (Old Style and New Style dates, O.S.) – 28 October 1704 (Old Style and New Style dates, O.S.)) was an English philosopher and physician, widely regarded as one of the most influential of the Enlightenment thi ...

, invites us to imagine two individuals who perceive colors differently: where one person sees red, the other sees green, and vice versa. Despite this difference in their subjective experiences, they behave and communicate as if their perceptions are the same, and no physical or behavioral test can reveal the inversion. Critics of functionalism, and of physicalism more broadly, argue that if we can imagine this happening without contradiction, it follows that we are imagining a change in a property that determines the way things look to us, but that has no physical basis.

The idea that an inverted spectrum would be undetectable in practice is also open to criticism on more scientific grounds, by C. L. Hardin, among others. As Alex Byrne puts it:

According to David Chalmers, all "functionally isomorphic

In mathematics, an isomorphism is a structure-preserving mapping or morphism between two structures of the same type that can be reversed by an inverse mapping. Two mathematical structures are isomorphic if an isomorphism exists between the ...

" systems (those with the same "fine-grained functional organization", i.e., the same information processing) will have qualitatively identical conscious experiences. He calls this the principle of ''organizational invariance''. For example, it implies that a silicon chip that is functionally isomorphic to a brain will have the same perception of the color red, given the same sensory inputs. He proposed the thought experiment of the "dancing qualia" to demonstrate it. It is a ''reductio ad absurdum

In logic, (Latin for "reduction to absurdity"), also known as (Latin for "argument to absurdity") or ''apagogical argument'', is the form of argument that attempts to establish a claim by showing that the opposite scenario would lead to absur ...

'' argument that starts by supposing that two such systems can have different qualia in the same situation. It involves a switch that enables to connect the main part of the brain with any of these two subsystems. For example, one subsystem can be a chunk of brain that causes to see an object as red, and the other one a silicon chip that causes to see an object as blue. Since both perform the same function within the brain, the subject would be unable to notice any change during the switch. Chalmers argues that this would be highly implausible if the qualia were truly switching between red and blue, hence the contradiction. Therefore, he concludes that the dancing qualia is impossible in practice, and the functionally isomorphic digital system would not only experience qualia, but it would have conscious experiences that are qualitatively identical to those of the biological system (e.g., seeing the same color). He also proposed a similar thought experiment, named the fading qualia, that argues that it is not possible for the qualia to fade when each biological neuron is replaced by a functional equivalent.

Analytic philosophy

"What's it like to be?" argument

American philosopher Thomas Nagel's paper '' What Is it Like to Be a Bat?'' is often cited in debates about qualia, though it does not use the word "qualia". Nagel argues that consciousness has an essentially subjective character, a what-it-is-like aspect. He states that "an organism has conscious mental states if and only if there is something that it is like to ''be'' that organism – something it is like ''for'' the organism." Nagel suggests that this subjective aspect may never be sufficiently accounted for by the objective methods of reductionistic science. He claims that "if we acknowledge that a physical theory of mind must account for the subjective character of experience, we must admit that no presently available conception gives us a clue about how this could be done." Furthermore, "it seems unlikely that any physical theory of mind can be contemplated until more thought has been given to the general problem of subjective and objective."

American philosopher Thomas Nagel's paper '' What Is it Like to Be a Bat?'' is often cited in debates about qualia, though it does not use the word "qualia". Nagel argues that consciousness has an essentially subjective character, a what-it-is-like aspect. He states that "an organism has conscious mental states if and only if there is something that it is like to ''be'' that organism – something it is like ''for'' the organism." Nagel suggests that this subjective aspect may never be sufficiently accounted for by the objective methods of reductionistic science. He claims that "if we acknowledge that a physical theory of mind must account for the subjective character of experience, we must admit that no presently available conception gives us a clue about how this could be done." Furthermore, "it seems unlikely that any physical theory of mind can be contemplated until more thought has been given to the general problem of subjective and objective."

Zombie argument

Saul Kripke argues that one key consequence of the claim that such things as raw feels, or qualia, can be meaningfully discussed is that it leads to the logical possibility of two entities exhibiting identical behavior in all ways despite one of them entirely lacking qualia. While few claim that such an entity, called a philosophical zombie, actually exists, the possibility is raised as a refutation of physicalism, and in defense of the hard problem of consciousness (the problem of accounting for, in physical terms, subjective, intrinsic, first-person experiences). The argument holds that it is conceivable for a person to have a duplicate, identical in every physical way, but lacking consciousness, called a "philosophical zombie." It would appear exactly the same as the original person, in both behavior and speech, just without subjective phenomenology. For these zombies to exist, qualia must not arise from any specific part or parts of the brain, for if it did there would be no difference between "normal humans" and philosophical zombies: The zombie/normal-human distinction can only be valid if subjective consciousness is separate from the physical brain. According to Chalmers, the simplest form of the argument goes as follows: #It is conceivable that there be zombies #If it is conceivable that there be zombies, it is metaphysically possible that there be zombies. #If it is metaphysically possible that there be zombies, then consciousness is non-physical. #Consciousness is nonphysical. Former AI researcher Marvin Minsky sees the argument as circular. He says the proposition of something physically identical to a human but withoutsubjective experience

In philosophy of mind, qualia (; singular: quale ) are defined as instances of Subjectivity, subjective, consciousness, conscious experience. The term ''qualia'' derives from the Latin neuter plural form (''qualia'') of the Latin adjective '':wi ...

assumes that the physical characteristics of humans cannot produce consciousness, which is exactly what the argument claims to prove. In other words, it tries to prove consciousness is nonphysical by assuming consciousness is nonphysical.

Explanatory gap argument

Joseph Levine's paper ''Conceivability, Identity, and the Explanatory Gap'' takes up where the criticisms of conceivability arguments (such as the inverted spectrum argument and the zombie argument) leave off. Levine agrees that conceivability is a flawed means of establishing metaphysical realities, but points out that even if we come to the ''metaphysical'' conclusion that qualia are physical, there is still an ''explanatory'' problem. However, such anepistemological

Epistemology is the branch of philosophy that examines the nature, origin, and limits of knowledge. Also called "the theory of knowledge", it explores different types of knowledge, such as propositional knowledge about facts, practical knowled ...

or explanatory problem might indicate an underlying metaphysical issue, as even if not proven by conceivability arguments, the non-physicality of qualia is far from ruled out.

Knowledge argument

In 1982, F. C. Jackson offered what he calls the "knowledge argument" for qualia. It goes as follows: Jackson claimed that she does. Thisthought experiment

A thought experiment is an imaginary scenario that is meant to elucidate or test an argument or theory. It is often an experiment that would be hard, impossible, or unethical to actually perform. It can also be an abstract hypothetical that is ...

has two purposes. First, it is intended to show that qualia exist. If we accept the thought experiment, we believe that upon leaving the room Mary gains something: the knowledge of a particular thing that she did not possess before. That knowledge, Jackson argues, is knowledge of the quale that corresponds to the experience of seeing red, and it must thus be conceded that qualia are real properties, since there is a difference between a person who has access to a particular quale and one who does not.

The second purpose of this argument is to refute the physicalist account of the mind. Specifically, the knowledge argument is an attack on the physicalist claim about the completeness of physical truths. The challenge posed to physicalism by the knowledge argument runs as follows:

#While in the room, Mary has acquired all the physical facts there are about color sensations, including the sensation of seeing red.

#When Mary exits the room and sees a ripe red tomato, she learns a new fact about the sensation of seeing red, namely its subjective character.

#Therefore, there are non-physical facts about color sensations. rom 1, 2#If there are non-physical facts about color sensations, then color sensations are non-physical events.

#Therefore, color sensations are non-physical events. rom 3, 4#If color sensations are non-physical events, then physicalism is false.

#Therefore, physicalism is false. rom 5, 6Some critics argue that Mary's confinement to a monochromatic environment wouldn't prevent her from forming color experiences or that she might deduce what colors look like from her complete physical knowledge. Others suggest that the thought experiment's conceivability might conflict with current or future scientific understanding of vision, but defenders maintain that its purpose is to challenge materialism conceptually, not scientifically.

Early in his career Jackson argued that qualia are epiphenomenal, meaning they have no causal influence on the physical world. The issue with this view is that if qualia are non-physical, it becomes unclear how they can have any effect on the brain or behavior. Jackson later rejected epiphenomenalism, arguing that knowledge about qualia is impossible if they are epiphenomenal. He concluded that there must be an issue with the knowledge argument, eventually embracing a representationalist account, arguing that sensory experiences can be understood in physical terms.

Proponents of qualia

Analytic philosophy

David Chalmers

David Chalmers formulated the '' hard problem of consciousness'', which raised the issue of qualia to a new level of importance and acceptance in the field of thephilosophy of mind

Philosophy of mind is a branch of philosophy that deals with the nature of the mind and its relation to the Body (biology), body and the Reality, external world.

The mind–body problem is a paradigmatic issue in philosophy of mind, although a ...

. In 1995 Chalmers argued for what he called "the principle of organizational invariance": if a system such as one of appropriately configured computer hardware reproduces the functional organization of the brain, it will also reproduce the qualia associated with the brain.

E. J. Lowe

E. J. Lowe denies that indirect realism, wherein which we have access only to sensory features internal to the brain, necessarily implies a Cartesian dualism. He agrees withBertrand Russell

Bertrand Arthur William Russell, 3rd Earl Russell, (18 May 1872 – 2 February 1970) was a British philosopher, logician, mathematician, and public intellectual. He had influence on mathematics, logic, set theory, and various areas of analytic ...

that the way images are received by our retinas, our "retinal images", are connected to "patterns of neural activity in the cortex". He defends a version of the ''causal theory of perception'' in which a causal path can be traced between the external object and the perception of it. He is careful to deny that we do any inferring from the sensory field; he believes this allows us to build an access to knowledge on that causal connection. In a later work he moves closer to the non-epistemic argument in that he postulates "a wholly non-conceptual component of perceptual experience".

J. B. Maund

John Barry Maund, an Australian philosopher of perception, argues that qualia can be described on two levels, a fact that he refers to as "dual coding". Maund extended his argument with reference to color. Color he sees as a dispositional property, not an objective one. Colors are "virtual properties", which means they are ''as if'' things possessed them. Although the naïve view attributes them to objects, they are intrinsic, non-relational, inner experiences. This allows for the different perceptions between person and person, and also leaves aside the claim that external objects are colored.Moreland Perkins

In his book ''Sensing the World,'' Moreland Perkins argues that qualia need not be identified as their objective sources: a smell, for instance, bears no direct resemblance to the molecular shape that gives rise to it, nor is a toothache actually in the tooth. Like Hobbes he views the process of sensing as complete in itself; as he puts it, it is not like "kicking a football" where an external object is required – it is more like "kicking a kick". This explanation evades the '' Homunculus Objection,'' as adhered to by Gilbert Ryle, among others. Ryle was unable to entertain this possibility, protesting that "in effect it explained the having of sensations as the not having of sensations". However, A. J. Ayer called this objection "very weak" as it betrayed an inability to detach the notion of eyes, or indeed any sensory organ, from the neural sensory experience.Howard Robinson and William Robinson

Philosopher Howard Robinson argued against reducing sensory experiences to physical explanations. He defended the theory of sense data, maintaining that sensory experiences involve qualia. As a dualist, Robinson held that mind and matter have distinct metaphysical natures. He maintained that the knowledge argument shows that physicalism fails to account for the qualitative nature of qualia. Similarly, William Robinson, in ''Understanding Phenomenal Consciousness'', advocates for dualism and rejects the idea of reducing phenomenal experience to neural processes. His theory of Qualitative Event Realism proposes that phenomenal consciousness consists of immaterial events caused by brain activity but not reducible to it. He seeks to conciliate dualism with scientific methodology, aiming for a future unified theory that respects both phenomenal qualities and scientific explanations.Neuroscience

Gerald Edelman

In his book ''Bright Air, Brilliant Fire'', neuroscientist and Nobel laureate in Physiology / Medicine Gerald Edelman says "that tdefinitely does not seem feasible ..to ignore completely the reality of qualia". As he sees it, it is impossible to explain color, sensations, and similar experiences "to a 'qualia-free' observer" by description alone. Edelman argues that proposing such a theory of consciousness is proposing "a theory based on a kind of God's-eye view of consciousness" and that any scientific theory requires the assumption "that observers have sensation as well as perception." He concludes by stating that assuming a theory that requires neither could exist "is to indulge the errors of theories that attempt syntactical formulations mapped onto objectivist interpretations – theories that ignore embodiment as a source of meaning. There is no qualia-free scientific observer."Antonio Damasio

Neurologist Antonio Damasio, in his book ''The Feeling Of What Happens'', defines qualia as "the simple sensory qualities to be found in the blueness of the sky or the tone of sound produced by a cello, and the fundamental components of the images in the movie metaphor are thus made of qualia." Damasio points out that "in all likelihood, I will never know your thoughts unless you tell me, and you will never know mine until I tell you." The reason he gives for this is that "the mind and its consciousness are first and foremost private phenomena" that are personal, private experiences that should be investigated as such. While he believes that trying to study these experiences "by the study of their behavioral correlates is wrong," he does think they can be studied as "the idea that subjective experiences are not scientifically accessible is nonsense." In his view the way to do this is for "enough observers oundertake rigorous observations according to the same experimental design; and ..that those observations be checked for consistency across observers and that they yield some form of measurement." He also thinks that "subjective observations ..can inspire objective experiments" and "be explained in terms of the available scientific knowledge". In his mind:Rodolfo Llinás

Neurologist Rodolfo Llinás states in his book '' I of the Vortex'' that qualia, from a neurological perspective, are essential for an organism's survival and played a key role in the evolution of nervous systems, including in simple creatures like ants or cockroaches. Llinás contends that qualia are a product of neuronal oscillation and citesanesthesia

Anesthesia (American English) or anaesthesia (British English) is a state of controlled, temporary loss of sensation or awareness that is induced for medical or veterinary purposes. It may include some or all of analgesia (relief from or prev ...

experiments, showing that qualia can be "turned off" by altering brain oscillations while other connections remain intact.

Vilayanur Ramachandran

Critics of qualia

Daniel Dennett

In '' Consciousness Explained'' and ''Quining Qualia,'' Daniel Dennett argues against qualia by claiming that the "knowledge argument" breaks down if one tries to apply it practically. In a series of thought experiments, which he calls '' intuition pumps,'' he brings qualia into the world ofneurosurgery

Neurosurgery or neurological surgery, known in common parlance as brain surgery, is the specialty (medicine), medical specialty that focuses on the surgical treatment or rehabilitation of disorders which affect any portion of the nervous system ...

, clinical psychology, and psychological experimentation. He argues that, once the concept of qualia is so imported, we can either make no use of it, or the questions introduced by it are unanswerable precisely because of the special properties defining qualia.

In Dennett's updated version of the inverted spectrum thought experiment, which he calls ''alternative neurosurgery'', you again awake to find that your qualia have been inverted – grass appears red, the sky appears orange, etc. According to the original account, you should be immediately aware that something has gone horribly wrong. Dennett argues, however, that it is impossible to know whether the diabolical neurosurgeons have indeed inverted your qualia (e.g. by tampering with your optic nerve), or have simply inverted your connection to memories of past qualia. Since both operations would produce the same result, you would have no means on your own to tell which operation has actually been conducted, and you are thus in the odd position of not knowing whether there has been a change in your "immediately apprehensible" qualia.

Dennett argues that for qualia to be taken seriously as a component of experience – for them to make sense as a discrete concept – it must be possible to show that:

Dennett attempts to show that we cannot satisfy (a) either through introspection or through observation, and that qualia's very definition undermines its chances of satisfying (b).

Supporters of qualia point out that in order for you to notice a change in qualia, you must compare your current qualia with your memories of past qualia. Arguably, such a comparison would involve immediate assessment of your current qualia and your memories of past qualia, but not of the past qualia themselves. Furthermore, modern functional brain imaging has increasingly suggested that the memory of an experience is processed in similar ways, and in similar zones of the brain, as the original perception.

This may mean that there would be asymmetric outcomes between altering the mechanism of perception of qualia and altering the memory of that qualia. If the diabolical neurosurgery altered the immediate perception of qualia, the inversion might not be noticed directly, since the brain zones which re-process the memories would invert the remembered qualia. On the other hand, alteration of the qualia memories themselves would be processed without inversion, and thus you would perceive them as an inversion. Thus, you might know immediately if memory of your qualia had been altered, but might not know if immediate qualia were inverted or whether the diabolical neurosurgeons had done a sham procedure.

Dennett responds to the '' Mary the color scientist'' thought experiment by arguing that Mary would not, in fact, learn something new if she stepped out of her black and white room to see the color red. Dennett asserts that if she already truly knew "everything about color", that knowledge would include a deep understanding of why and how human neurology causes us to sense the quale of color. Mary would therefore already know exactly what to expect upon seeing red, before ever leaving the room.

Dennett argues that the misleading aspect of the story is that Mary is supposed to not merely be knowledgeable about color but to actually know ''all'' the physical facts about it, which would be a knowledge so deep that it exceeds what can be imagined, and twists our intuitions. If Mary really does know everything physical there is to know about the experience of color, then this effectively grants her almost omniscient powers of knowledge. Using this, she will be able to deduce her own reaction, and figure out exactly what the experience of seeing red will feel like.

Dennett finds that many people find it difficult to see this, so he uses the case of RoboMary to further illustrate what it would be like for Mary to possess such a vast knowledge of the physical workings of the human brain and color vision. RoboMary is an intelligent robot who, instead of having color cameras as eyes, has a software lock such that they are only able to perceive black and white and shades in-between.

RoboMary can examine the computer brain of similar non-color-locked robots when they see red, and see exactly how they react and what kinds of impulses occur. RoboMary can also construct a simulation of her own brain, unlock the simulation's color-lock and, with reference to the other robots, simulate exactly how this simulation of herself reacts to seeing red. RoboMary naturally has control over all of her internal states except for the color-lock. With the knowledge of her simulation's internal states upon seeing red, RoboMary can put her own internal states directly into the states they would be in upon seeing red. In this way, without ever actually seeing red through her cameras, she will know exactly what it is like to see red.

Dennett uses this example as an attempt to show us that Mary's all-encompassing physical knowledge makes her own internal states as transparent as those of a robot or computer, and it is as straightforward for her to figure out exactly how it feels to see red.

Perhaps Mary's failure to learn exactly what seeing red feels like is simply a failure of language, or a failure of our ability to describe experiences. An alien race with a different method of communication or description might be perfectly able to teach their version of Mary exactly how seeing the color red would feel. Perhaps it is simply a uniquely human failing to communicate first-person experiences from a third-person perspective. Dennett suggests that the description might even be possible using English. He uses a simpler version of the Mary thought experiment to show how this might work. What if Mary was in a room without triangles and was prevented from seeing or making any triangles? An English-language description of just a few words would be sufficient for her to imagine what it is like to see a triangle – she can simply and directly visualize a triangle in her mind. Similarly, Dennett proposes, it is perfectly, logically, possible that the quale of what it is like to see red could eventually be described in an English-language description of millions or billions of words.

In ''Are we explaining consciousness yet?,'' Dennett approves of an account of qualia defined as the deep, rich collection of individual neural responses that are too fine-grained for language to capture. For instance, a person might have an alarming reaction to yellow because of a yellow car that hit her previously, and someone else might have a nostalgic reaction to a comfort food. These effects are too individual-specific to be captured by English words. "If one dubs this inevitable residue ''qualia'', then qualia are guaranteed to exist, but they are just more of the same, dispositional properties that have not yet been entered in the catalog".

Paul Churchland

According to Paul Churchland, Mary might be considered akin to a feral child who suffered extreme isolation during childhood. Technically when Mary leaves the room, she would not have the ability to see or know what the color red is, as a brain has to learn and develop how to see colors. Patterns need to form in the V4 section of thevisual cortex

The visual cortex of the brain is the area of the cerebral cortex that processes visual information. It is located in the occipital lobe. Sensory input originating from the eyes travels through the lateral geniculate nucleus in the thalam ...

, which occurs via exposure to wavelengths of light. This exposure needs to occur during the early stages of brain

The brain is an organ (biology), organ that serves as the center of the nervous system in all vertebrate and most invertebrate animals. It consists of nervous tissue and is typically located in the head (cephalization), usually near organs for ...

development. In Mary's case, the identifications and categorizations of color

Color (or colour in English in the Commonwealth of Nations, Commonwealth English; American and British English spelling differences#-our, -or, see spelling differences) is the visual perception based on the electromagnetic spectrum. Though co ...

will only be in respect to representations of black and white.

Gary Drescher

In his book ''Good and Real,'' Gary Drescher compares qualia with " gensyms" (generated symbols) inCommon Lisp

Common Lisp (CL) is a dialect of the Lisp programming language, published in American National Standards Institute (ANSI) standard document ''ANSI INCITS 226-1994 (S2018)'' (formerly ''X3.226-1994 (R1999)''). The Common Lisp HyperSpec, a hyperli ...

. These are objects that Lisp treats as having no properties or components, which can only be identified as equal or not equal to other objects. Drescher explains, "we have no introspective access to whatever internal properties make the ''red'' gensym recognizably distinct from the ''green'' ..even though we know the sensation when we experience it." Under this interpretation of qualia, Drescher responds to the Mary thought experiment by noting that "knowing about red-related cognitive structures and the dispositions they engender – even if that knowledge were implausibly detailed and exhaustive – would not necessarily give someone who lacks prior color-experience the slightest clue whether the card now being shown is of the color called red." However, this does not imply that our experience of red is non-mechanical, as "gensyms are a routine feature of computer-programming languages".

David Lewis

David K. Lewis introduced a hypothesis about types of knowledge and their transmission in qualia cases. Lewis agrees that Mary cannot learn what red looks like through her monochrome physicalist studies, but he proposes that this does not matter. Learning transmits information, but experiencing qualia does not transmit information: it communicates abilities. When Mary sees red, she does not acquire any new information; she instead gains new abilities. Now she can remember what red looks like, imagine what other red things might look like and recognize further instances of redness. Lewis states that Jackson's thought experiment uses the ''phenomenal information hypothesis'' – that is, that the new knowledge that Mary gains upon seeing red is phenomenal information. Lewis then proposes a different ''ability hypothesis'' that differentiates between two types of knowledge: knowledge "that" (''information'') and knowledge "how" (''abilities''). Normally the two are entangled; ordinary learning is also an experience of the subject concerned, and people learn both information (for instance, that Freud was a psychologist) and gain ability (to recognize images of Freud). However, in the thought experiment, Mary can use ordinary learning only to gain "that" knowledge. She is prevented from using experience to gain the "how" knowledge that would allow her to remember, imagine and recognize the color red. We have the intuition that Mary has been deprived of some vital data to do with the experience of redness. It is also uncontroversial that some things cannot be learned inside the room; for example, Mary cannot learn how to ski within the room. Lewis has articulated that information and ability are potentially different things. In this way, ''physicalism'' is still compatible with the conclusion that Mary gains new knowledge. It is also useful for considering other instances of qualia – "being a bat" is an ability, so it is "how" knowledge.Marvin Minsky

Artificial intelligence

Artificial intelligence (AI) is the capability of computer, computational systems to perform tasks typically associated with human intelligence, such as learning, reasoning, problem-solving, perception, and decision-making. It is a field of re ...

researcher Marvin Minsky thinks the problems posed by qualia are essentially issues of complexity, or rather of mistaking complexity for simplicity.

Michael Tye

Roger Scruton

Roger Scruton, while skeptical that neurobiology can tell us much about consciousness, believes qualia is an incoherent concept, and that Wittgenstein's private language argument effectively disproves it. Scruton writes, In his book ''On Human Nature'', Scruton poses a potential line of criticism to this, which is that while Wittgenstein's private language argument does disprove the concept of reference to qualia, or the idea that we can talk, even to ourselves, of their nature; it does not disprove their existence altogether. Scruton believes that this is a valid criticism, and this is why he stops short of actually saying that qualia do not exist, and instead merely suggests that we should abandon the concept. However, he quotes Wittgenstein in response: "Whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must be silent."Richard Rorty

In Chapter 1 of '' Philosophy and the Mirror of Nature'', Richard Rorty suggests that the concept of a quale is the result of a reification fallacy.

In attempting to answer the question "why is the phenomenal immaterial?", he notes that there is nothing to suggest that the phenomenal and the physical are anything more than two different ways of talking about the states or properties of people. Even if the appearance/reality distinction does not exist for phenomenal properties, the fact that self-attributions of such properties are typically considered incorrigible could simply reflect an epistemic distinction (he also hints at the idea that this incorrigibility could be a mere linguistic convention, which he develops more fully in Chapter 2). If this is the case, then Rorty claims that the problem of consciousness is not actually a real metaphysical problem:

In Chapter 1 of '' Philosophy and the Mirror of Nature'', Richard Rorty suggests that the concept of a quale is the result of a reification fallacy.

In attempting to answer the question "why is the phenomenal immaterial?", he notes that there is nothing to suggest that the phenomenal and the physical are anything more than two different ways of talking about the states or properties of people. Even if the appearance/reality distinction does not exist for phenomenal properties, the fact that self-attributions of such properties are typically considered incorrigible could simply reflect an epistemic distinction (he also hints at the idea that this incorrigibility could be a mere linguistic convention, which he develops more fully in Chapter 2). If this is the case, then Rorty claims that the problem of consciousness is not actually a real metaphysical problem:

" e purportedly metaphysical "problem of consciousness" is no more and no less than the epistemological "problem of privileged access," and that once this is seen questions about dualism versus materialism lose their interest."Rorty suggests that the only answer that one can give as to why qualia are ontologically distinct from physical processes is that the lack of an appearance/reality distinction is an essential feature of their being (i.e. it is an essential feature of a quale that it be incorrigibly known), but he immediately notes that in making this move, qualia have been implicitly hypostatized such that they can take on the property of being pure appearances. In other words, they have been turned into non-physical, property-bearing particulars, meaning they are no longer properties of the person who has them, but rather particulars that exist ''in addition to'' that person:

"The neo-dualist who identifies a pain with how it feels to be in pain is hypostatizing a property—painfulness—into a special sort of particular, a particular of that sort whose ''esse is percipi'' and whose reality is exhausted in our initial acquaintance with it. The neo-dualist is no longer talking about how people feel but about feelings as little self-subsistent entities, floating free of people in the way in which universals float free of the instantiations."He thus criticizes philosophers who accuse materialists of not taking qualia seriously when they talk about the neural workings of the brain, since their reified notion of a quale is completely different than what materialists have in mind:

"Thus when neo-dualists say that how pains ''feel'' are essential to what pains ''are'', and then criticize Smart for thinking of the causal role of certain neurons as what is essential to pain, they are changing the subject. Smart is talking about what is essential to people being in pain, whereas neo-dualists like Kripke are talking about what is essential for something's being ''a pain''."

See also

References

Citations

Other references

* * * Qualia and the sensation of time. * * Biological perspective. * * ''A Field Guide to the Philosophy of Mind'' ** ** * ''Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

The ''Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy'' (''SEP'') is a freely available online philosophy resource published and maintained by Stanford University, encompassing both an online encyclopedia of philosophy and peer-reviewed original publication ...

''

**

**

**

{{Authority control

Abstraction

Cognition

Concepts in epistemology

Concepts in metaphilosophy

Concepts in metaphysics

Concepts in the philosophy of mind

Concepts in the philosophy of science

Consciousness

Mental processes

Metaphysics of mind

Ontology

Philosophy of perception

Subjective experience

Theory of mind

Thought

Unsolved problems in neuroscience