Stratocracy on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

A stratocracy is a

A stratocracy is a

The

The

The closest modern equivalent to a stratocracy, the

The closest modern equivalent to a stratocracy, the

The political scientist

The political scientist

* The country of Amestris in the ''Fullmetal Alchemist'' manga and Fullmetal Alchemist (TV series), anime series is a nominal parliamentary republic without elections, where parliament has been used as a façade to distract from the authoritarian regime, as the government is almost completely centralized by the military, and the majority of government positions are occupied by military personnel.

* Bowser (character), Bowser from the ''Super Mario'' video game franchise is the supreme leader of a stratocratic empire in which he has many other generals working under his militaristic rules such as Kamek, Private Goomp, Sergeant Guy, Corporal Paraplonk and many others.

* The Cardassian Union of the ''Star Trek'' universe can be described as a stratocracy, with a constitutionally and socially sanctioned, as well as a politically dominant military that nonetheless has immense Totalitarianism, totalitarian characteristics.

* In Bryan Konietzko and Michael Dante DiMartino's ''Avatar: The Last Airbender'', the Earth Kingdom is very divided and during the Hundred Year War relies on an unofficial Confederation, confederal stratocratic rule of small towns to maintain control from the Fire Nation's military, without the Earth Monarch's assistance.

* Both Eldia and Marley from the Japanese manga and anime series ''Attack on Titan'' are stratocratic nations ruled by military governments. After a coup d'état, the government of Eldia was displaced in favor of a military-led system with a puppet monarchy as its public front.

* The Galactic Empire (Star Wars), Galactic Empire from the original ''Star Wars'' trilogy can be described as a stratocracy. Although ruled by the Sith through its Emperor, Sheev Palpatine, known secretly as Darth Sidious, the functioning of the entire government was controlled by the military and explicitly sanctioned by its leaders. All sectors were controlled by a Moff or Grand Moff who were also high-ranking military officers.

* The Global Defense Initiative from the ''Command & Conquer'' franchise is another example: initially being a United Nations task force to combat the Brotherhood of Nod and research the alien substance Tiberium, later expanding to a worldwide government led by military leaders after the collapse of society due to Tiberium's devastating effects on Earth.

* Blizzard Entertainment's ''World of Warcraft'' features an antagonistic group of Orc (Warcraft), Orcish clans, which joined in the formation of ''The Iron Horde'', a militaristic clan governed by warlords.

* In Robert A. Heinlein's ''Starship Troopers'', the Terran Federation (Starship Troopers), Terran Federation was set up by a group of military veterans in Aberdeen, Scotland when governments collapsed following a world war. While national service is voluntary, earning citizenship in the Federation requires civilians to "enroll in the Federal Service of the Terran Federation for a term of not less than two years and as much longer as may be required by the needs of the Service." While Federal Service is not exclusively military service, that appears to be the dominant form. It is believed that only those willing to sacrifice their lives on the state's behalf are fit to govern. While the government is a representative democracy, the franchise is only granted to people who have completed service, mostly in the military, due to this law (active military can neither vote nor serve in political/non-military offices).

* The Turians, Turian Hierarchy of ''Mass Effect'' is another example of a fictional stratocracy, where the civilian and military populations cannot be distinguished, and the government and the military are the same, and strongly meritocratic, with designated responsibilities for everyone.

* The five members of Greater Turkiye in the manga and anime ''Altair: A Record of Battles'' are called stratocracies, with them being based on the

* The country of Amestris in the ''Fullmetal Alchemist'' manga and Fullmetal Alchemist (TV series), anime series is a nominal parliamentary republic without elections, where parliament has been used as a façade to distract from the authoritarian regime, as the government is almost completely centralized by the military, and the majority of government positions are occupied by military personnel.

* Bowser (character), Bowser from the ''Super Mario'' video game franchise is the supreme leader of a stratocratic empire in which he has many other generals working under his militaristic rules such as Kamek, Private Goomp, Sergeant Guy, Corporal Paraplonk and many others.

* The Cardassian Union of the ''Star Trek'' universe can be described as a stratocracy, with a constitutionally and socially sanctioned, as well as a politically dominant military that nonetheless has immense Totalitarianism, totalitarian characteristics.

* In Bryan Konietzko and Michael Dante DiMartino's ''Avatar: The Last Airbender'', the Earth Kingdom is very divided and during the Hundred Year War relies on an unofficial Confederation, confederal stratocratic rule of small towns to maintain control from the Fire Nation's military, without the Earth Monarch's assistance.

* Both Eldia and Marley from the Japanese manga and anime series ''Attack on Titan'' are stratocratic nations ruled by military governments. After a coup d'état, the government of Eldia was displaced in favor of a military-led system with a puppet monarchy as its public front.

* The Galactic Empire (Star Wars), Galactic Empire from the original ''Star Wars'' trilogy can be described as a stratocracy. Although ruled by the Sith through its Emperor, Sheev Palpatine, known secretly as Darth Sidious, the functioning of the entire government was controlled by the military and explicitly sanctioned by its leaders. All sectors were controlled by a Moff or Grand Moff who were also high-ranking military officers.

* The Global Defense Initiative from the ''Command & Conquer'' franchise is another example: initially being a United Nations task force to combat the Brotherhood of Nod and research the alien substance Tiberium, later expanding to a worldwide government led by military leaders after the collapse of society due to Tiberium's devastating effects on Earth.

* Blizzard Entertainment's ''World of Warcraft'' features an antagonistic group of Orc (Warcraft), Orcish clans, which joined in the formation of ''The Iron Horde'', a militaristic clan governed by warlords.

* In Robert A. Heinlein's ''Starship Troopers'', the Terran Federation (Starship Troopers), Terran Federation was set up by a group of military veterans in Aberdeen, Scotland when governments collapsed following a world war. While national service is voluntary, earning citizenship in the Federation requires civilians to "enroll in the Federal Service of the Terran Federation for a term of not less than two years and as much longer as may be required by the needs of the Service." While Federal Service is not exclusively military service, that appears to be the dominant form. It is believed that only those willing to sacrifice their lives on the state's behalf are fit to govern. While the government is a representative democracy, the franchise is only granted to people who have completed service, mostly in the military, due to this law (active military can neither vote nor serve in political/non-military offices).

* The Turians, Turian Hierarchy of ''Mass Effect'' is another example of a fictional stratocracy, where the civilian and military populations cannot be distinguished, and the government and the military are the same, and strongly meritocratic, with designated responsibilities for everyone.

* The five members of Greater Turkiye in the manga and anime ''Altair: A Record of Battles'' are called stratocracies, with them being based on the

A stratocracy is a

A stratocracy is a form of government

A government is the system or group of people governing an organized community, generally a state.

In the case of its broad associative definition, government normally consists of legislature, executive, and judiciary. Government is a m ...

headed by military chiefs. The branches of government

The separation of powers principle functionally differentiates several types of state power (usually law-making, adjudication, and execution) and requires these operations of government to be conceptually and institutionally distinguishable ...

are administered by military forces, the government is legal under the laws of the jurisdiction at issue, and is usually carried out by military workers.

Etymology

The word "stratocracy" comes .Description of stratocracy

The word stratocracy first appeared in 1652 from thepolitical theorist

A political theorist is someone who engages in constructing or evaluating political theory, including political philosophy. Theorists may be academics or independent scholars.

Ancient

* Aristotle

* Chanakya

* Cicero

* Confucius

* Mencius

* ...

Robert Filmer

Sir Robert Filmer (c. 1588 – 26 May 1653) was an English political theorist who defended the divine right of kings. His best known work, '' Patriarcha'', published posthumously in 1680, was the target of numerous Whig attempts at rebuttal ...

, being preceded in 1649 by used by Claudius Salmasius

Claude Saumaise (15 April 1588 – 3 September 1653), also known by the Latin name Claudius Salmasius, was a French classical scholar.

Life

Salmasius was born at Semur-en-Auxois in Burgundy (region), Burgundy. When Salmasius was sixteen, his fath ...

in reference to the newly declared Commonwealth of England

The Commonwealth of England was the political structure during the period from 1649 to 1660 when Kingdom of England, England and Wales, later along with Kingdom of Ireland, Ireland and Kingdom of Scotland, Scotland, were governed as a republi ...

. John Bouvier and Daniel Gleason describe a stratocracy as one where citizens with mandatory or voluntary military service, or veterans who have been honorably discharged, have the right to elect or govern. The military's administrative, judicial

The judiciary (also known as the judicial system, judicature, judicial branch, judiciative branch, and court or judiciary system) is the system of courts that adjudicates legal disputes/disagreements and interprets, defends, and applies the law ...

, and/or legislative

A legislature (, ) is a deliberative assembly with the legal authority to make laws for a political entity such as a country, nation or city on behalf of the people therein. They are often contrasted with the executive and judicial powers ...

powers are supported by law, the constitution, and the society. It does not necessarily need to be autocratic

Autocracy is a form of government in which absolute power is held by the head of state and Head of government, government, known as an autocrat. It includes some forms of monarchy and all forms of dictatorship, while it is contrasted with demo ...

or oligarchic

Oligarchy (; ) is a form of government in which power rests with a small number of people. Members of this group, called oligarchs, generally hold usually hard, but sometimes soft power through nobility, fame, wealth, or education; or throug ...

by nature in order to preserve its right to rule. The political scientist Samuel Finer

Samuel Edward Finer FBA (22 September 1915 – 9 June 1993) was a British political scientist and historian specializing in comparative politics, who was instrumental in advancing political studies as an academic subject in the United King ...

distinguished between stratocracies, where the army takes decisions and rules directly, and military regimes or dictatorships, where the army does not rule itself but instead is tasked with the primary responsibility of enforcing and defending the rule of civil leaders who set the policies of the state and control the activities of the military. Peter Lyon wrote that through history stratocracies have been relatively rare, and that in the latter half of the twentieth century there has been a noticeable increase in the number of stratocratic states due to the "rapid collapse of the West European thalassocracies

A thalassocracy or thalattocracy, sometimes also maritime empire, is a state with primarily maritime realms, an empire at sea, or a seaborne empire. Traditional thalassocracies seldom dominate interiors, even in their home territories. Examples o ...

".

Notable examples of stratocracies

Historical stratocracies

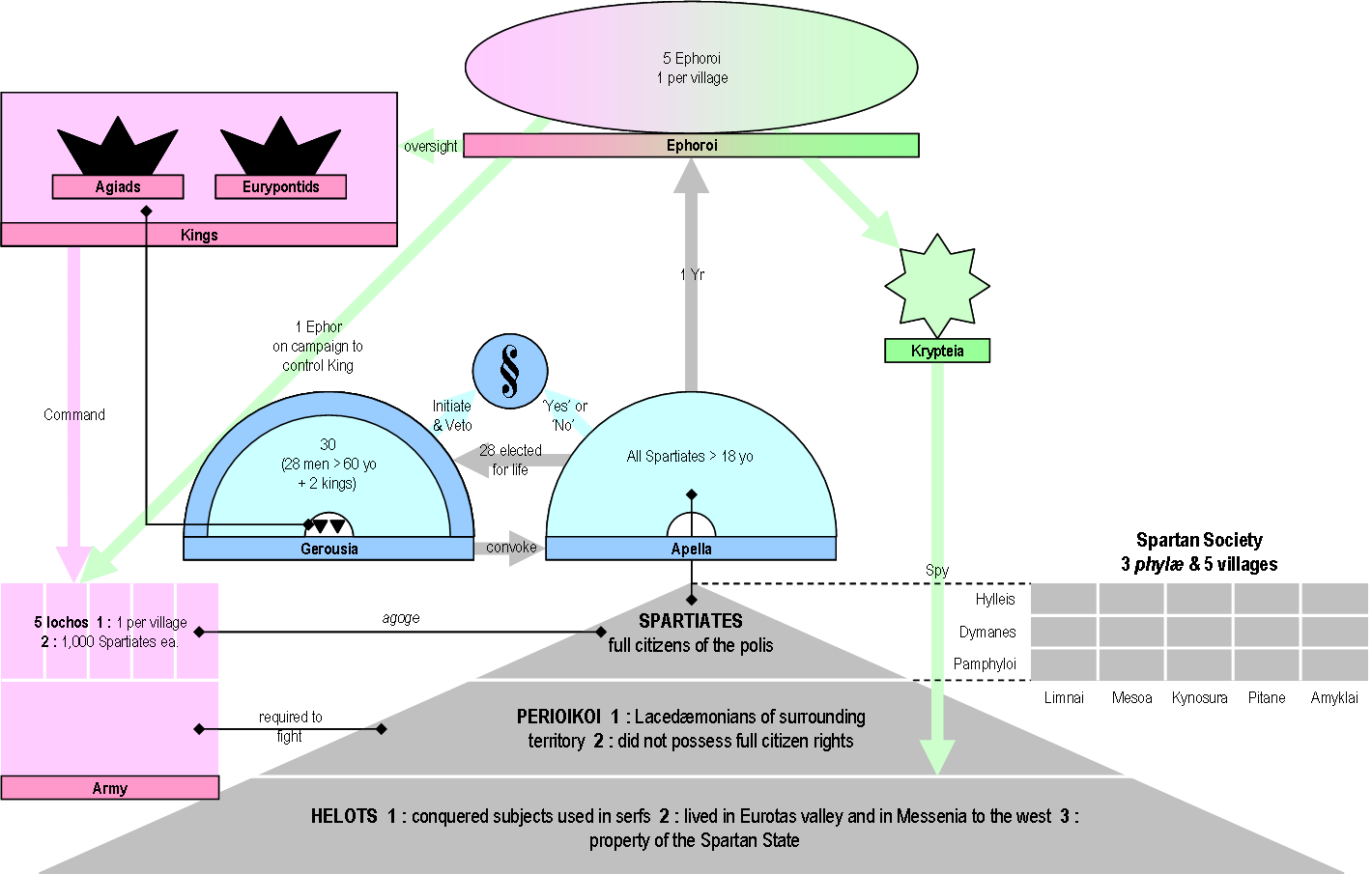

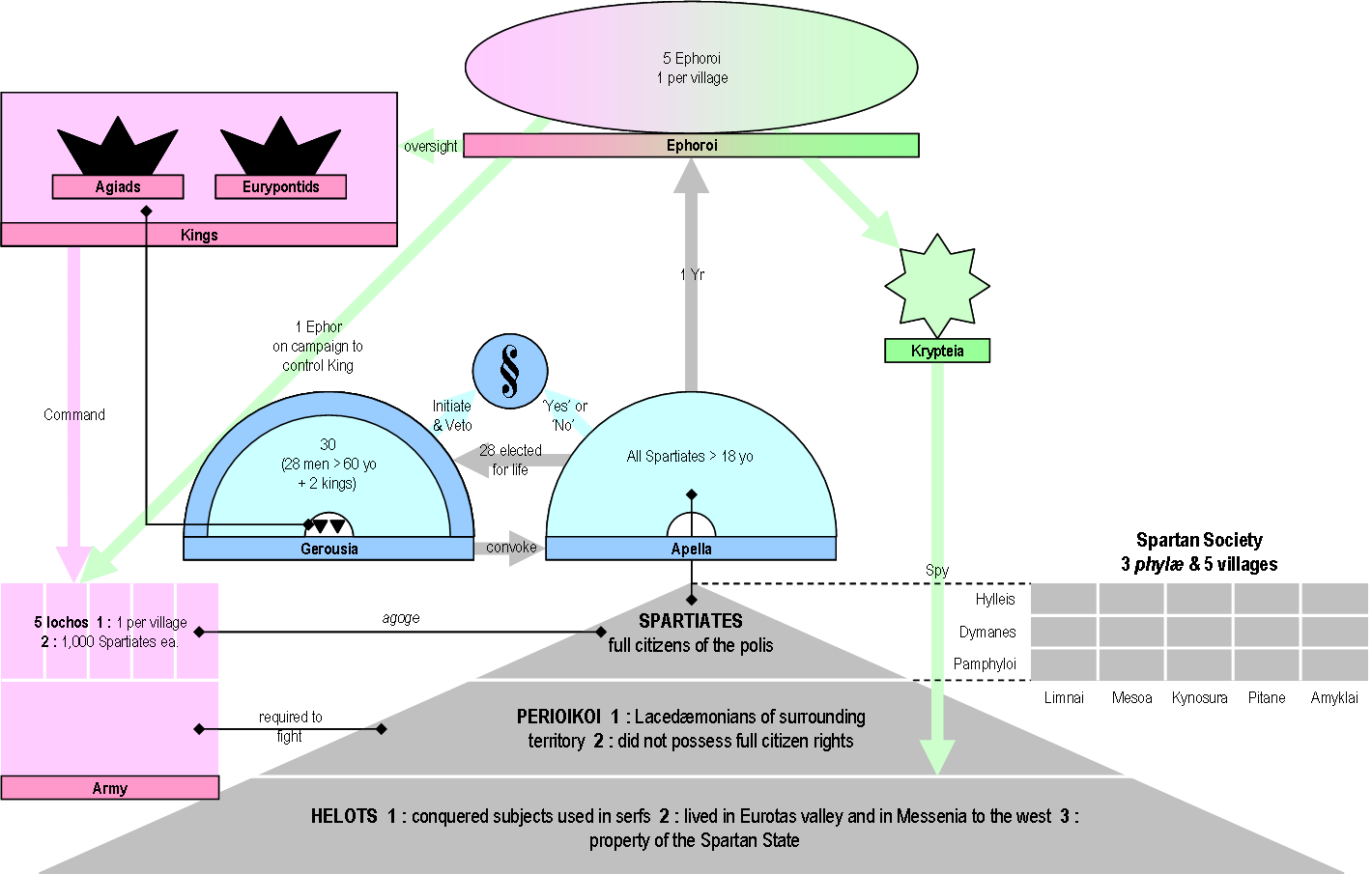

Sparta

The

The Diarchy

Diarchy (from Greek , ''di-'', "double", and , ''-arkhía'', "ruled"),Occasionally spelled ''dyarchy'', as in the ''Encyclopaedia Britannica'' article on the colonial British institution duarchy, or duumvirate. is a form of government charac ...

of Sparta

Sparta was a prominent city-state in Laconia in ancient Greece. In antiquity, the city-state was known as Lacedaemon (), while the name Sparta referred to its main settlement in the Evrotas Valley, valley of Evrotas (river), Evrotas rive ...

was a stratocratic kingdom. From a young age, male Spartans

Sparta was a prominent city-state in Laconia in ancient Greece. In antiquity, the city-state was known as Lacedaemon (), while the name Sparta referred to its main settlement in the valley of Evrotas river in Laconia, in southeastern P ...

were put through the agoge

The ( in Attic Greek, or , in Doric Greek) was the training program prerequisite for Spartiate (citizen) status. Spartiate-class boys entered it at age seven, and would stop being a student of the agoge at age 21. It was considered violent by ...

, necessary for full-citizenship, which was a rigorous education and training program to prepare them to be warriors. Aristotle

Aristotle (; 384–322 BC) was an Ancient Greek philosophy, Ancient Greek philosopher and polymath. His writings cover a broad range of subjects spanning the natural sciences, philosophy, linguistics, economics, politics, psychology, a ...

describes the kingship at Sparta as "a kind of unlimited and perpetual generalship" (Pol. iii. 1285a), while Isocrates

Isocrates (; ; 436–338 BC) was an ancient Greek rhetorician, one of the ten Attic orators. Among the most influential Greek rhetoricians of his time, Isocrates made many contributions to rhetoric and education through his teaching and writte ...

refers to the Spartans as "subject to an oligarchy

Oligarchy (; ) is a form of government in which power rests with a small number of people. Members of this group, called oligarchs, generally hold usually hard, but sometimes soft power through nobility, fame, wealth, or education; or t ...

at home, to a kingship on campaign" (iii. 24).

Rome

One of the most notable and long-lived examples of a stratocratic state isAncient Rome

In modern historiography, ancient Rome is the Roman people, Roman civilisation from the founding of Rome, founding of the Italian city of Rome in the 8th century BC to the Fall of the Western Roman Empire, collapse of the Western Roman Em ...

, though the stratocratic system developed over time. Following the deposition of the last Roman king

The king of Rome () was the ruler of the Roman Kingdom, a legendary period of Roman history that functioned as an elective monarchy. According to legend, the first king of Rome was Romulus, who founded the city in 753 BC upon the Palatine H ...

Lucius Tarquinius Superbus

Lucius Tarquinius Superbus (died 495 BC) was the legendary seventh and final king of Rome, reigning 25 years until the popular uprising that led to the establishment of the Roman Republic.Livy, ''ab urbe condita libri'', wikisource:From_the_ ...

, Rome became an oligarchic Republic. However, with the gradual expansion of the empire and conflicts with its rival Carthage

Carthage was an ancient city in Northern Africa, on the eastern side of the Lake of Tunis in what is now Tunisia. Carthage was one of the most important trading hubs of the Ancient Mediterranean and one of the most affluent cities of the classic ...

, culminating in the Punic Wars

The Punic Wars were a series of wars fought between the Roman Republic and the Ancient Carthage, Carthaginian Empire during the period 264 to 146BC. Three such wars took place, involving a total of forty-three years of warfare on both land and ...

, the Roman political and military system experienced drastic changes. Following the so-called "Marian reforms

The Marian reforms were putative changes to the composition and operation of the Roman army during the late Roman Republic usually attributed to Gaius Marius (a general who was consul in 107, 104–100, and 86 BC). The most important of ...

", de facto political power became concentrated under military leadership, as the loyalty of the legionaries shifted from the Senate to its generals.

Under the First Triumvirate

The First Triumvirate was an informal political alliance among three prominent politicians in the late Roman Republic: Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus, Marcus Licinius Crassus, and Gaius Julius Caesar. The republican constitution had many veto points. ...

and during the subsequent civil wars, militarism influenced the formation of the Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ruled the Mediterranean and much of Europe, Western Asia and North Africa. The Roman people, Romans conquered most of this during the Roman Republic, Republic, and it was ruled by emperors following Octavian's assumption of ...

, the head of which was acclaimed as "Imperator

The title of ''imperator'' ( ) originally meant the rough equivalent of ''commander'' under the Roman Republic. Later, it became a part of the titulature of the Roman Emperors as their praenomen. The Roman emperors generally based their autho ...

", previously an honorary title for distinguished military commanders. The Roman army

The Roman army () served ancient Rome and the Roman people, enduring through the Roman Kingdom (753–509 BC), the Roman Republic (509–27 BC), and the Roman Empire (27 BC–AD 1453), including the Western Roman Empire (collapsed Fall of the W ...

either approved of or acquiesced in the accession of every Roman emperor, with the Praetorian Guard

The Praetorian Guard (Latin language, Latin: ''cohortes praetoriae'') was the imperial guard of the Imperial Roman army that served various roles for the Roman emperor including being a bodyguard unit, counterintelligence, crowd control and ga ...

having a decisive role in Imperial succession until Emperor Constantine abolished it. Militarization of the Empire increased over time and emperors were increasingly beholden to their armies and fleets, yet how active emperors were in actually commanding in the field in military campaigns varied from emperor to emperor, even from dynasty to dynasty. The vital political importance of the army persisted up until the destruction of the Eastern (Byzantine) Empire with the fall of Constantinople

The Fall of Constantinople, also known as the Conquest of Constantinople, was the capture of Constantinople, the capital of the Byzantine Empire by the Ottoman Empire. The city was captured on 29 May 1453 as part of the culmination of a 55-da ...

in 1453.

Goryeo

From 1170 to 1270, the kingdom ofGoryeo

Goryeo (; ) was a Korean state founded in 918, during a time of national division called the Later Three Kingdoms period, that unified and ruled the Korea, Korean Peninsula until the establishment of Joseon in 1392. Goryeo achieved what has b ...

was under effective military rule, with puppet kings on the throne serving mainly as figureheads. The majority of this period was spent under the rule of the Choe family, who set up a parallel system of private administrative systems from their military forces.

Cossacks

Cossacks

The Cossacks are a predominantly East Slavic languages, East Slavic Eastern Christian people originating in the Pontic–Caspian steppe of eastern Ukraine and southern Russia. Cossacks played an important role in defending the southern borde ...

were predominantly East Slavic people who became known as members of democratic, semi-military and semi-naval communities, predominantly located in Ukraine

Ukraine is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the List of European countries by area, second-largest country in Europe after Russia, which Russia–Ukraine border, borders it to the east and northeast. Ukraine also borders Belarus to the nor ...

and in Southern Russia

Southern Russia or the South of Russia ( rus, Юг России, p=juk rɐˈsʲiɪ) is a Colloquialism, colloquial term for the southernmost geographic portion of European Russia. The term is generally used to refer to the region of Russia's So ...

. They inhabited sparsely populated areas and islands in the lower Dnieper

The Dnieper or Dnepr ( ), also called Dnipro ( ), is one of the major transboundary rivers of Europe, rising in the Valdai Hills near Smolensk, Russia, before flowing through Belarus and Ukraine to the Black Sea. Approximately long, with ...

, Don, Terek, and Ural river basins, and played an important role in the historical and cultural development of both Russia

Russia, or the Russian Federation, is a country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia. It is the list of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the world, and extends across Time in Russia, eleven time zones, sharing Borders ...

and Ukraine. The Zaporozhian Sich

The Zaporozhian Sich (, , ; also ) was a semi-autonomous polity and proto-state of Zaporozhian Cossacks that existed between the 16th to 18th centuries, for the latter part of that period as an autonomous stratocratic state within the Cossa ...

was a Cossack semi-autonomous polity and proto-state that existed between the 16th and 18th centuries, and existed as an independent stratocratic state as the Cossack Hetmanate

The Cossack Hetmanate (; Cossack Hetmanate#Name, see other names), officially the Zaporozhian Host (; ), was a Ukrainian Cossacks, Cossack state. Its territory was located mostly in central Ukraine, as well as in parts of Belarus and southwest ...

for over a hundred years.

Military frontier of the Habsburg monarchy

TheMilitary Frontier

The Military Frontier (; sh-Cyrl-Latn, Војна крајина, Vojna krajina, sh-Cyrl-Latn, Војна граница, Vojna granica, label=none; ; ) was a borderland of the Habsburg monarchy and later the Austrian and Austro-Hungari ...

was a borderland of the Habsburg monarchy

The Habsburg monarchy, also known as Habsburg Empire, or Habsburg Realm (), was the collection of empires, kingdoms, duchies, counties and other polities (composite monarchy) that were ruled by the House of Habsburg. From the 18th century it is ...

(which became the Austrian Empire

The Austrian Empire, officially known as the Empire of Austria, was a Multinational state, multinational European Great Powers, great power from 1804 to 1867, created by proclamation out of the Habsburg monarchy, realms of the Habsburgs. Duri ...

and later the Austro-Hungarian Empire

Austria-Hungary, also referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the Dual Monarchy or the Habsburg Monarchy, was a multi-national constitutional monarchy in Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. A military and diplomatic alliance, it consist ...

). The military frontier acted as the '' cordon sanitaire'' against incursions from the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

. Located in the southern part of Hungarian crown land, the frontier was separated from local jurisdiction and was under direct Viennese Viennese may refer to:

* Vienna, the capital of Austria

* Viennese people, List of people from Vienna

* Viennese German, the German dialect spoken in Vienna

* Viennese classicism

* Viennese coffee house, an eating establishment and part of Viennese ...

central military administration from the 1500s to 1872. Unlike the rest of the Catholic dominated territory of the empire, the frontier area had relatively freer religious laws in order to attract settlements into the area.

Modern stratocracies

The closest modern equivalent to a stratocracy, the

The closest modern equivalent to a stratocracy, the State Peace and Development Council

The State Peace and Development Council ( ; abbreviated SPDC or , ) was the official name of the Military dictatorship, military government of Burma (Myanmar) which, in 1997, succeeded the State Law and Order Restoration Council (; abbrevi ...

of Myanmar

Myanmar, officially the Republic of the Union of Myanmar; and also referred to as Burma (the official English name until 1989), is a country in northwest Southeast Asia. It is the largest country by area in Mainland Southeast Asia and has ...

(Burma), which ruled from 1997 to 2011, arguably differed from most other military dictatorships in that it completely abolished the civilian constitution and legislature. A new constitution that came into effect in 2010 cemented the Tatmadaw

The Tatmadaw, also known as the Sit-Tat, is the armed forces of Myanmar (formerly Burma). It is administered by the Ministry of Defence and composed of the Myanmar Army, the Myanmar Navy and the Myanmar Air Force. Auxiliary services include ...

's hold on power through mechanisms such as reserving 25% of the seats in the legislature

A legislature (, ) is a deliberative assembly with the legal authority to make laws for a political entity such as a country, nation or city on behalf of the people therein. They are often contrasted with the executive and judicial power ...

for military personnel. The civilian constitutional government was dissolved again in the 2021 Myanmar coup d'état

A coup d'état in Myanmar began on the morning of 1 February 2021, when Elections in Myanmar, democratically elected members of the country's ruling party, the National League for Democracy (NLD), were deposed by the Tatmadaw, Myanmar's milita ...

, with power being transferred back to the Tatmadaw through the State Administration Council

The State Administration Council (; abbreviated SAC or နစက) is the military junta currently governing Myanmar, established by Commander-in-Chief of Defence Services Min Aung Hlaing following the 2021 Myanmar coup d'état, February 2021 c ...

.

The United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Northwestern Europe, off the coast of European mainland, the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

overseas territory

A territory is an area of land, sea, or space, belonging or connected to a particular country, person, or animal.

In international politics, a territory is usually a geographic area which has not been granted the powers of self-government, ...

, the Sovereign Base Areas of Akrotiri and Dhekelia

Akrotiri and Dhekelia (), officially the Sovereign Base Areas of Akrotiri and Dhekelia (SBA), is a British Overseas Territory made of two non-contiguous areas on the island of Cyprus. The areas, which include British military bases and instal ...

on the island of Cyprus, provides another example of a stratocracy: British Forces Cyprus governs the territory, with Air vice-marshal

Air vice-marshal (Air Vce Mshl or AVM) is an air officer rank used by some air forces, with origins from the Royal Air Force. The rank is also used by the air forces of many countries which have historical British influence and it is sometime ...

Peter J. M. Squires serving as administrator from 2022. The territory is subject to unique laws different from both those of the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Northwestern Europe, off the coast of European mainland, the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

and those of Cyprus

Cyprus (), officially the Republic of Cyprus, is an island country in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. Situated in West Asia, its cultural identity and geopolitical orientation are overwhelmingly Southeast European. Cyprus is the List of isl ...

.

States argued to be stratocratic

United States

The political scientist

The political scientist Harold Lasswell

Harold Dwight Lasswell (February 13, 1902 – December 18, 1978) was an American political scientist and communications theorist. He earned his bachelor's degree in philosophy and economics and his Ph.D. from the University of Chicago. He was a ...

wrote in 1941 of his concerns that the world was moving towards "a world of 'garrison states with the United States of America

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 contiguo ...

being one of the countries moving in that direction. This was supported by the historian Richard Kohn in 1975 commenting on the US's creation of a military state during its early independence, and by the political scientist Samuel Fitch in 1985. The historian Eric Hobsbawm

Eric John Ernest Hobsbawm (; 9 June 1917 – 1 October 2012) was a British historian of the rise of industrial capitalism, socialism and nationalism. His best-known works include his tetralogy about what he called the "long 19th century" (''Th ...

has used the existence and power of the military-industrial complex in the US as evidence of it being a stratocratic state. The expansion and prioritisation of the military during the administrations of Reagan and H. W. Bush have also been described as signs of stratocracy in the US. The futurist

Futurists (also known as futurologists, prospectivists, foresight practitioners and horizon scanners) are people whose specialty or interest is futures studies or futurology or the attempt to systematically explore predictions and possibilities ...

Paul Saffo and the researcher Robert Marzec have argued that the post 9/11 projection of the United States was trending towards stratocracy.

USSR

The philosopher and economistCornelius Castoriadis

Cornelius Castoriadis (; 11 March 1922 – 26 December 1997) was a Greeks in France, Greek-FrenchMemos 2014, p. 18: "he was ... granted full French citizenship in 1970." philosopher, sociologist, social critic, economist, psychoanalyst, au ...

wrote in his 1980 text, ''Facing the War'', that Russia had become the primary world military power. To sustain this, in the context of the visible economic inferiority of the Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

in the civilian sector, he proposed that the society may no longer be dominated by the one-party state

A one-party state, single-party state, one-party system or single-party system is a governance structure in which only a single political party controls the ruling system. In a one-party state, all opposition parties are either outlawed or en ...

bureaucracy of the Communist Party but by a "stratocracy" describing it as a separate and dominant military sector with expansionist designs on the world. He further argued that this meant there was no internal class dynamic that could lead to social revolution within Russian society and that change could only occur through foreign intervention. Timothy Luke agreed that under the secretaryship of Mikhail Gorbachev

Mikhail Sergeyevich Gorbachev (2 March 1931 – 30 August 2022) was a Soviet and Russian politician who served as the last leader of the Soviet Union from 1985 to dissolution of the Soviet Union, the country's dissolution in 1991. He served a ...

this was the USSR moving towards a stratocratic state.

African states

Various countries in post-colonialAfrica

Africa is the world's second-largest and second-most populous continent after Asia. At about 30.3 million km2 (11.7 million square miles) including adjacent islands, it covers 20% of Earth's land area and 6% of its total surfac ...

have been described as stratocracies. The Republic of Egypt under the leadership of Nasser

Gamal Abdel Nasser Hussein (15 January 1918 – 28 September 1970) was an Egyptian military officer and revolutionary who served as the second president of Egypt from 1954 until his death in 1970. Nasser led the Egyptian revolution of 1952 a ...

was described by the political theorist P. J. Vatikiotis as a stratocratic state.; ; ; The recent Egyptian governments since the Arab Spring

The Arab Spring () was a series of Nonviolent resistance, anti-government protests, Rebellion, uprisings, and Insurgency, armed rebellions that spread across much of the Arab world in the early 2010s. It began Tunisian revolution, in Tunisia ...

, including that of Abdel Fattah el-Sisi

Abdel Fattah Saeed Hussein Khalil El-Sisi (born 19 November 1954) is an Egyptian politician and retired military officer who has been serving as the sixth and current president of Egypt since 2014.

After the 2011 Egyptian revolution and 201 ...

, have also been called stratocratic. David George commented in a 1988 paper that the military dictatorship of Idi Amin

Idi Amin Dada Oumee (, ; 30 May 192816 August 2003) was a Ugandan military officer and politician who served as the third president of Uganda from 1971 until Uganda–Tanzania War, his overthrow in 1979. He ruled as a Military dictatorship, ...

in Uganda

Uganda, officially the Republic of Uganda, is a landlocked country in East Africa. It is bordered to the east by Kenya, to the north by South Sudan, to the west by the Democratic Republic of the Congo, to the south-west by Rwanda, and to the ...

and the apartheid regime in South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the Southern Africa, southernmost country in Africa. Its Provinces of South Africa, nine provinces are bounded to the south by of coastline that stretches along the Atlantic O ...

should be considered stratocracies. Various previous Nigerian governments have been described as stratocratic in research, including the government under Olusegun Obasanjo

Chief Olusegun Matthew Okikiola Ogunboye Aremu Obasanjo (; ; born 5 March 1937) is a Nigerian former army general, politician and statesman who served as Nigeria's head of state from 1976 to 1979 and later as its president from 1999 to 200 ...

, and the Armed Forces Ruling Council led by Ibrahim Babangida

Ibrahim Badamasi Babangida (born 17 August 1941) is a Nigerian statesman and military dictator who ruled as military president of Nigeria from 1985 when he orchestrated a coup d'état against his military and political arch-rival Muhammadu ...

. Under the 1978 constitution of eSwatini

Eswatini, formally the Kingdom of Eswatini, also known by its former official names Swaziland and the Kingdom of Swaziland, is a landlocked country in Southern Africa. It is bordered by South Africa on all sides except the northeast, where i ...

Sobhuza II

Sobhuza II (; also known as Nkhotfotjeni, Mona; 22 July 1899 – 21 August 1982) was ''Ngwenyama'' (King) of Swaziland (now Eswatini) for 82 years and 254 days, the longest verifiable reign of any monarch in recorded history.

Sobhuza was bo ...

appointed the Swazi army commander as the country's prime minister, and the second-in-command of the army as the head of the civil service board. This fusing of military and civil power continued in subsequent appointments, with many of the appointees viewing their civil roles as secondary to their military positions. Ghana

Ghana, officially the Republic of Ghana, is a country in West Africa. It is situated along the Gulf of Guinea and the Atlantic Ocean to the south, and shares borders with Côte d’Ivoire to the west, Burkina Faso to the north, and Togo to t ...

under Jerry Rawlings

Jerry John Rawlings (born Jerry Rawlings John; 22 June 194712 November 2020) was a Ghanaian military officer, aviator, and politician who led the country briefly in 1979 and then from 1981 to 2001. He led a military junta until 1993 and then se ...

has also been described as being stratocratic in nature. Karl Marx's term of barracks socialism was retermed by the political scientist Michel Martin in their description of socialist stratocracies in the Middle East

The Middle East (term originally coined in English language) is a geopolitical region encompassing the Arabian Peninsula, the Levant, Turkey, Egypt, Iran, and Iraq.

The term came into widespread usage by the United Kingdom and western Eur ...

, Latin America

Latin America is the cultural region of the Americas where Romance languages are predominantly spoken, primarily Spanish language, Spanish and Portuguese language, Portuguese. Latin America is defined according to cultural identity, not geogr ...

, and Africa

Africa is the world's second-largest and second-most populous continent after Asia. At about 30.3 million km2 (11.7 million square miles) including adjacent islands, it covers 20% of Earth's land area and 6% of its total surfac ...

, including specifically the People's Republic of Benin

The People's Republic of Benin (; sometimes translated literally as the Benin Popular Republic or Popular Republic of Benin) was a socialist state located in the Gulf of Guinea on the African continent, which became present-day Benin in 1990 ...

. Martin also believes the praetorianism of francophone African republics can be called stratocratic, including the Côte d'Ivoire

Ivory Coast, also known as Côte d'Ivoire and officially the Republic of Côte d'Ivoire, is a country on the southern coast of West Africa. Its capital city of Yamoussoukro is located in the centre of the country, while its largest city and ...

and the Central African Republic

The Central African Republic (CAR) is a landlocked country in Central Africa. It is bordered by Chad to Central African Republic–Chad border, the north, Sudan to Central African Republic–Sudan border, the northeast, South Sudan to Central ...

.

Other

The French historian François Raguenet wrote in 1691 of the stratocracy ofOliver Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell (25 April 15993 September 1658) was an English statesman, politician and soldier, widely regarded as one of the most important figures in British history. He came to prominence during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms, initially ...

in the Protectorate

A protectorate, in the context of international relations, is a State (polity), state that is under protection by another state for defence against aggression and other violations of law. It is a dependent territory that enjoys autonomy over ...

, and commented that he believed William III of England

William III (William Henry; ; 4 November 1650 – 8 March 1702), also known as William of Orange, was the sovereign Prince of Orange from birth, Stadtholder of County of Holland, Holland, County of Zeeland, Zeeland, Lordship of Utrecht, Utrec ...

was seeking to revive the stratocracy in England.

The Prussia

Prussia (; ; Old Prussian: ''Prūsija'') was a Germans, German state centred on the North European Plain that originated from the 1525 secularization of the Prussia (region), Prussian part of the State of the Teutonic Order. For centuries, ...

n military writer Georg Henirich von Berenhorst wrote in hindsight that ever since the reign of the '' soldier king'', Prussia always remained "not a country with an army, but an army with a country" (a quote often misattributed to Voltaire

François-Marie Arouet (; 21 November 169430 May 1778), known by his ''Pen name, nom de plume'' Voltaire (, ; ), was a French Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment writer, philosopher (''philosophe''), satirist, and historian. Famous for his wit ...

and Honoré Gabriel Riqueti, comte de Mirabeau

Honoré Gabriel Riqueti, Count of Mirabeau (; 9 March 17492 April 1791) was a French writer, orator, statesman and a prominent figure of the early stages of the French Revolution.

A member of the nobility, Mirabeau had been involved in numerous ...

). It has been argued the subsequent dominance of the Kingdom of Prussia

The Kingdom of Prussia (, ) was a German state that existed from 1701 to 1918.Marriott, J. A. R., and Charles Grant Robertson. ''The Evolution of Prussia, the Making of an Empire''. Rev. ed. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1946. It played a signif ...

in the North German Confederation

The North German Confederation () was initially a German military alliance established in August 1866 under the leadership of the Kingdom of Prussia, which was transformed in the subsequent year into a confederated state (a ''de facto'' feder ...

and German Empire

The German Empire (),; ; World Book, Inc. ''The World Book dictionary, Volume 1''. World Book, Inc., 2003. p. 572. States that Deutsches Reich translates as "German Realm" and was a former official name of Germany. also referred to as Imperia ...

and the expansive militarism

Militarism is the belief or the desire of a government or a people that a state should maintain a strong military capability and to use it aggressively to expand national interests and/or values. It may also imply the glorification of the mili ...

in their administrations and policies, saw a continuance of the stratocratic Prussian government.

British commentators such as Sir Richard Burton described the pre-Tanzimat

The (, , lit. 'Reorganization') was a period of liberal reforms in the Ottoman Empire that began with the Edict of Gülhane of 1839 and ended with the First Constitutional Era in 1876. Driven by reformist statesmen such as Mustafa Reşid Pash ...

Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

as a stratocratic state.

The Warlord Era

The Warlord Era was the period in the history of the Republic of China between 1916 and 1928, when control of the country was divided between rival Warlord, military cliques of the Beiyang Army and other regional factions. It began after the de ...

of China is viewed as period of stratocratic struggles with the researcher Peng Xiuliang pointing to the actions and policies of Wang Shizhen, a general and politician of the Republic of China (1912–1949), Republic of China, as an example of the stratocratic forces within the Chinese government of the time.

History of Poland during World War I, Occupied Poland in World War I was put under the (general military governments) of Germany and Austria-Hungary. This government was a stratocratic system where the military was responsible for the political administration of Poland.

Various military juntas of Military junta#Americas, Central and South America have also been described as stratocracies.

Since 1967, the Israeli-occupied territories, Israeli occupation of the Israeli occupation of the West Bank, West Bank, East Jerusalem (both taken from Jordan), Israeli occupation of the Sinai Peninsula, Sinai Peninsula, Israeli occupation of the Gaza Strip, Gaza Strip (taken from United Arab Republic, Egypt) and the Golan Heights (taken from Syria) after the Six-Day War can be argued to have been under stratocratic rule. While the West Bank and Gaza were governed by the Israeli Military Governorate and Israeli Civil Administration, Civil Administration which was later given to the Palestinian National Authority that governs the Palestinian territories, only Jerusalem Law, East Jerusalem and the Golan Heights Law, Golan Heights were annexed into Israeli territory from 1980 which is still internationally unrecognized and once referred to these territories by the United Nations as ''occupied Arab territories''.

Fictional stratocracies

Stratocratic forms of government have been popular in fictional stories.Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

.

See also

* Junta (governing body) * Militarism * Political strongman * Military government: ** Military dictatorship ** Military junta ** Military occupationReferences

Bibliography

* * * * * * * * * * * * {{refend Authoritarianism Forms of government Militarism Military sociology