Stewart Menzies on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Major General Sir Stewart Graham Menzies, (; 30 January 1890 – 29 May 1968) was Chief of

During the

During the

When the

When the

MI6

The Secret Intelligence Service (SIS), commonly known as MI6 ( Military Intelligence, Section 6), is the foreign intelligence service of the United Kingdom, tasked mainly with the covert overseas collection and analysis of human intelligenc ...

, the British Secret Intelligence Service (SIS), from 1939 to 1952, during and after the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

.

Early life, family

Stewart Graham Menzies was born in England in 1890 into a wealthy family as the second son of John Graham Menzies and Susannah West Wilson, daughter of ship-owner Arthur Wilson of Tranby Croft. His grandfather, Graham Menzies, was awhisky

Whisky or whiskey is a type of liquor made from Fermentation in food processing, fermented grain mashing, mash. Various grains (which may be Malting, malted) are used for different varieties, including barley, Maize, corn, rye, and wheat. Whisky ...

distiller

Distillation, also classical distillation, is the process of separating the component substances of a liquid mixture of two or more chemically discrete substances; the separation process is realized by way of the selective boiling of the mixt ...

who helped establish a cartel

A cartel is a group of independent market participants who collaborate with each other as well as agreeing not to compete with each other in order to improve their profits and dominate the market. A cartel is an organization formed by producers ...

and made huge profits. His parents became friends of King Edward VII. Menzies was a nephew of Scottish Liberal Party politician and member of the House of Commons Robert Stewart Menzies. But Menzies' father was dissolute, never established a worthwhile career, and wasted his share of the family fortune; he died of tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB), also known colloquially as the "white death", or historically as consumption, is a contagious disease usually caused by ''Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can al ...

in 1911 in his early 50s, leaving only a minimal estate.

Menzies was educated at Eton College

Eton College ( ) is a Public school (United Kingdom), public school providing boarding school, boarding education for boys aged 13–18, in the small town of Eton, Berkshire, Eton, in Berkshire, in the United Kingdom. It has educated Prime Mini ...

, becoming president of the student society Pop, and left in 1909. He excelled in sports, hunting and cross-country running. He won prizes for his studies of languages, and was considered an all-around excellent student.

Early military career

Life Guards

From Eton he joined theGrenadier Guards

The Grenadier Guards (GREN GDS) is the most senior infantry regiment of the British Army, being at the top of the Infantry Order of Precedence. It can trace its lineage back to 1656 when Lord Wentworth's Regiment was raised in Bruges to protect ...

as a second lieutenant. After a year with this regiment, he transferred to the Second Life Guards. He was promoted to lieutenant and appointed adjutant

Adjutant is a military appointment given to an Officer (armed forces), officer who assists the commanding officer with unit administration, mostly the management of “human resources” in an army unit. The term is used in French-speaking armed ...

by 1913.

First World War action

During the

During the First World War

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

Menzies served in Belgium. He was wounded at Zandvoorde in October 1914, and fought gallantly in the First Battle of Ypres

The First Battle of Ypres (, , – was a battle of the First World War, fought on the Western Front (World War I), Western Front around Ypres, in West Flanders, Belgium. The battle was part of the First Battle of Flanders, in which German A ...

in November 1914. Menzies was promoted to captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader or highest rank officer of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police depa ...

on 14 November, and received the DSO in person from King George V

George V (George Frederick Ernest Albert; 3 June 1865 – 20 January 1936) was King of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and Emperor of India, from 6 May 1910 until his death in 1936.

George was born during the reign of his pa ...

on 2 December.''C: The Secret Life of Sir Stewart Graham Menzies, Spymaster to Winston Churchill'', by Anthony Cave Brown, 1987, Macmillan, New York, , pp. 60–81

Menzies' regiment was decimated during fighting in 1915, suffering very heavy casualties in the Second Battle of Ypres. Menzies was seriously injured in a gas attack in 1915, and was honourably discharged from active combat service.

Intelligence service

He then joined thecounterintelligence

Counterintelligence (counter-intelligence) or counterespionage (counter-espionage) is any activity aimed at protecting an agency's Intelligence agency, intelligence program from an opposition's intelligence service. It includes gathering informati ...

section of Field Marshal Douglas Haig

Field marshal (United Kingdom), Field Marshal Douglas Haig, 1st Earl Haig (; 19 June 1861 – 29 January 1928) was a senior Officer (armed forces), officer of the British Army. During the First World War he commanded the British Expeditionary F ...

, the British commander. In late 1917, he reported to senior British leadership that Haig's intelligence chief Brigadier John Charteris was fudging intelligence estimates, which soon led to Charteris' removal. This whistle-blowing was apparently done very discreetly. Menzies was promoted to brevet major before the end of the war.

MI6

Following the end of the war, Menzies entered MI6 (also known as SIS). He was a member of the British delegation to the 1919 Versailles Peace Conference. Soon after the war, Menzies was promoted to lieutenant-colonel of the Imperial General Staff, General Staff Officer, first grade. Within MI6, he became assistant director for special intelligence. AdmiralHugh Sinclair

Admiral Sir Hugh Francis Paget Sinclair, (18 August 1873 – 4 November 1939), known as Quex Sinclair, was a British intelligence officer. He was Director of British Naval Intelligence between 1919 and 1921, and he subsequently helped to se ...

became director-general of MI6 in 1924, and he made Menzies his deputy by 1929, with Menzies being promoted to full colonel

Colonel ( ; abbreviated as Col., Col, or COL) is a senior military Officer (armed forces), officer rank used in many countries. It is also used in some police forces and paramilitary organizations.

In the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries, a colon ...

soon afterwards.

In 1924, Menzies was allegedly involved—alongside Sidney Reilly and Desmond Morton—in the forging of the Zinoviev letter.Page 121, Michael Kettle, ''Sidney Reilly: The True Story of the World's Greatest Spy'', 1986, St. Martin's Press, . This forgery is considered to have been instrumental in the Conservative Party's victory in the United Kingdom general election of 1924, which ended the country's first Labour government.''Telegraph'', 5 February 1999.

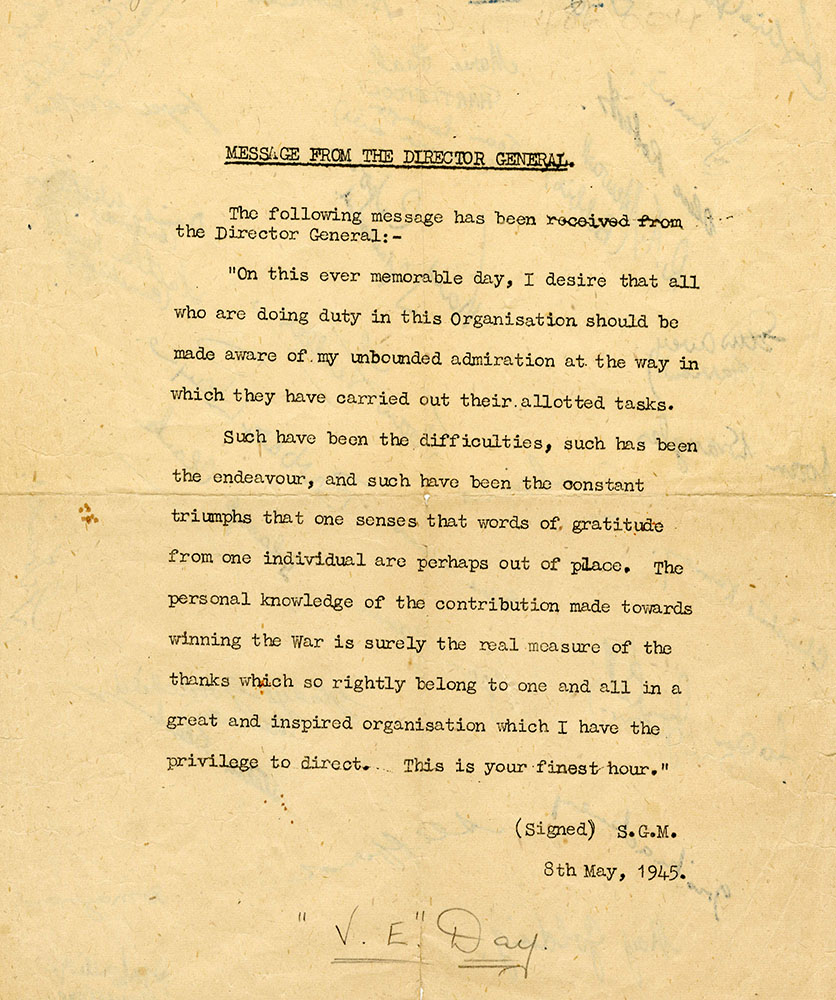

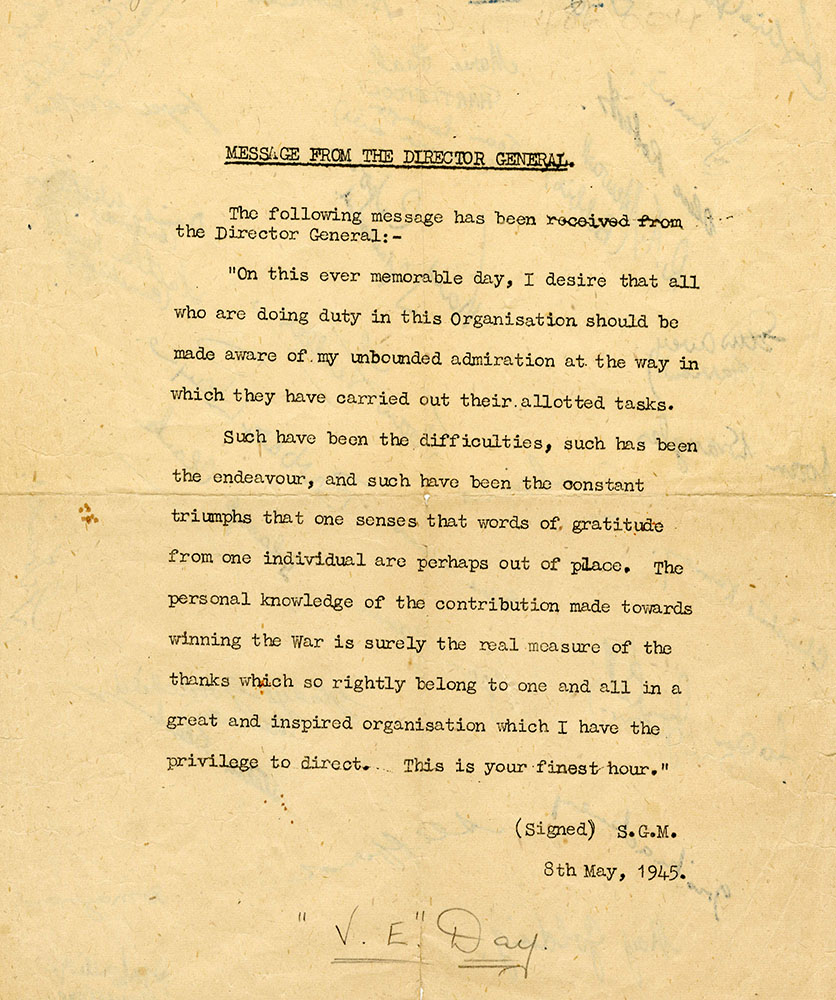

Chief of MI6

In 1939, when Admiral Sinclair died, Menzies was appointed Chief ofSecret Intelligence Service

The Secret Intelligence Service (SIS), commonly known as MI6 (MI numbers, Military Intelligence, Section 6), is the foreign intelligence service of the United Kingdom, tasked mainly with the covert overseas collection and analysis of Human i ...

(the SIS). He expanded wartime intelligence and counterintelligence departments and supervised codebreaking

Cryptanalysis (from the Greek ''kryptós'', "hidden", and ''analýein'', "to analyze") refers to the process of analyzing information systems in order to understand hidden aspects of the systems. Cryptanalysis is used to breach cryptographic secu ...

efforts at Bletchley Park

Bletchley Park is an English country house and Bletchley Park estate, estate in Bletchley, Milton Keynes (Buckinghamshire), that became the principal centre of Allies of World War II, Allied World War II cryptography, code-breaking during the S ...

.

Second World War

When the

When the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

began, SIS expanded greatly. Menzies insisted on wartime control of codebreaking, and this gave him immense power and influence, which he used judiciously. By distributing the Ultra material collected by the Government Code and Cypher School

The Government Code and Cypher School (GC&CS) was a British signals intelligence agency set up in 1919. During the First World War, the British Army and Royal Navy had separate signals intelligence agencies, MI1b and NID25 (initially known as R ...

, MI6 became an important branch of the government for the first time. Extensive breaches of Nazi

Nazism (), formally named National Socialism (NS; , ), is the far-right politics, far-right Totalitarianism, totalitarian socio-political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in Germany. During H ...

Enigma signals

A signal is both the process and the result of Signal transmission, transmission of data over some transmission media, media accomplished by embedding some variation. Signals are important in multiple subject fields including signal processin ...

gave Menzies and his team enormous insight into Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (20 April 1889 – 30 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was the dictator of Nazi Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his suicide in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the lea ...

's strategy, and this was kept a closely held secret, not only during the war, but until as late as 1974. ( Frederick Winterbotham's 1974 book ''The Ultra Secret'' lifted the cloak of secrecy at last.) The Nazis had suspicions, but believed Enigma to be unbreakable, and never knew during the war that the Allies were reading a high proportion of their wireless

Wireless communication (or just wireless, when the context allows) is the transfer of information (''telecommunication'') between two or more points without the use of an electrical conductor, optical fiber or other continuous guided transm ...

traffic.

Menzies kept Prime Minister Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 1874 – 24 January 1965) was a British statesman, military officer, and writer who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1940 to 1945 (Winston Churchill in the Second World War, ...

supplied daily with important Ultra decrypts, and the two worked together to ensure that financial resources were devoted toward research and upgrading technology at Bletchley Park, to keep pace with Nazi coding refinements, as well as directing talented workers to the massive effort, which employed nearly 10,000 workers by 1945. Bletchley's efforts were decisive in the battle against Nazi submarine warfare

Submarine warfare is one of the four divisions of underwater warfare, the others being anti-submarine warfare, Naval mine, mine warfare and Naval mine, mine countermeasures.

Submarine warfare consists primarily of Diesel engine, diesel and nu ...

, which was severely threatening trans-Atlantic shipping, particularly in the first half of 1943. Britain, which was cut off from Europe after mid-1940, was almost completely dependent on North American supplies for survival. The access to Ultra was also vitally important in the battle for Normandy

Normandy (; or ) is a geographical and cultural region in northwestern Europe, roughly coextensive with the historical Duchy of Normandy.

Normandy comprises Normandy (administrative region), mainland Normandy (a part of France) and insular N ...

, leading up to D-Day

The Normandy landings were the landing operations and associated airborne operations on 6 June 1944 of the Allied invasion of Normandy in Operation Overlord during the Second World War. Codenamed Operation Neptune and often referred to as ...

in June 1944, and afterward.

Menzies has been suspected as being involved with the assassination, on 24 December 1942, of François Darlan, the Vichy

Vichy (, ; ) is a city in the central French department of Allier. Located on the Allier river, it is a major spa and resort town and during World War II was the capital of Vichy France. As of 2021, Vichy has a population of 25,789.

Known f ...

military commander who defected to the Allies in Algeria

Algeria, officially the People's Democratic Republic of Algeria, is a country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It is bordered to Algeria–Tunisia border, the northeast by Tunisia; to Algeria–Libya border, the east by Libya; to Alger ...

. British historian David Reynolds noted in his book, ''In Command of History'', that Menzies—who rarely left London during the war—was in Algiers

Algiers is the capital city of Algeria as well as the capital of the Algiers Province; it extends over many Communes of Algeria, communes without having its own separate governing body. With 2,988,145 residents in 2008Census 14 April 2008: Offi ...

around the period he was killed, making SOE (Special Operations Executive

Special Operations Executive (SOE) was a British organisation formed in 1940 to conduct espionage, sabotage and reconnaissance in German-occupied Europe and to aid local Resistance during World War II, resistance movements during World War II. ...

) involvement seem likely.

Menzies, who was promoted to major-general in January 1944, also supported efforts to contact anti-Nazi

Nazism (), formally named National Socialism (NS; , ), is the far-right politics, far-right Totalitarianism, totalitarian socio-political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in Germany. During H ...

resistance, including Wilhelm Canaris

Wilhelm Franz Canaris (1 January 1887 – 9 April 1945) was a admiral (Germany), German admiral and the chief of the ''Abwehr'' (the German military intelligence, military-intelligence service) from 1935 to 1944. Initially a supporter of Ad ...

, the anti-Hitler head of Abwehr

The (German language, German for ''resistance'' or ''defence'', though the word usually means ''counterintelligence'' in a military context) ) was the German military intelligence , military-intelligence service for the ''Reichswehr'' and the ...

, in Germany. Prime Minister Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 1874 – 24 January 1965) was a British statesman, military officer, and writer who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1940 to 1945 (Winston Churchill in the Second World War, ...

was kept informed of these efforts throughout the war, and information from and about the Nazi resistance was exploited tactically. Menzies coordinated his operations with Special Operations Executive (SOE) (although he reputedly considered them "amateurs"), British Security Coordination (BSC), Office of Strategic Services

The Office of Strategic Services (OSS) was the first intelligence agency of the United States, formed during World War II. The OSS was formed as an agency of the Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) to coordinate espionage activities behind enemy lines ...

(OSS) and the Free French Forces

__NOTOC__

The French Liberation Army ( ; AFL) was the reunified French Army that arose from the merging of the Armée d'Afrique with the prior Free French Forces (; FFL) during World War II. The military force of Free France, it participated ...

. He was awarded the Order of the Yugoslav Crown.

After the Second World War

After the war, Menzies reorganised the SIS for theCold War

The Cold War was a period of global Geopolitics, geopolitical rivalry between the United States (US) and the Soviet Union (USSR) and their respective allies, the capitalist Western Bloc and communist Eastern Bloc, which lasted from 1947 unt ...

. He absorbed most of SOE. He was sometimes at odds with the Labour governments. He also had to weather a scandal inside SIS after revelations that SIS officer Kim Philby

Harold Adrian Russell "Kim" Philby (1 January 191211 May 1988) was a British intelligence officer and a double agent for the Soviet Union. In 1963, he was revealed to be a member of the Cambridge Five, a spy ring that had divulged British secr ...

was a Soviet spy.

Menzies was already the head of the service when Kim Philby joined in 1941. Nonetheless, Menzies deserved some of the blame for Soviet agents having penetrated MI6, according to Anthony Cave Brown in his book ''C: The Secret Life of Sir Stewart Graham Menzies, Spymaster to Winston Churchill''. Cave Brown insists that Menzies's primary criteria were whether the applicants were upper-class former officers and recommended by another government department, or else were known to him personally. In his ''New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''NYT'') is an American daily newspaper based in New York City. ''The New York Times'' covers domestic, national, and international news, and publishes opinion pieces, investigative reports, and reviews. As one of ...

'' review of Brown's book, novelist Ken Follett makes this conclusion: "Mr Philby outwitted Menzies because Mr Philby was intelligent and professional and cool, where Menzies was an amiable upper-class sportsman who was out of his depth. And British intelligence, except for the code breakers, was like Menzies—amateur, anti-intellectual and wholly outclassed."

After 43 continuous years of service in the British Army, Menzies retired to Bridges Court in Luckington in rural Wiltshire

Wiltshire (; abbreviated to Wilts) is a ceremonial county in South West England. It borders Gloucestershire to the north, Oxfordshire to the north-east, Berkshire to the east, Hampshire to the south-east, Dorset to the south, and Somerset to ...

at 62 in mid-1952. His success at SIS was not limited to adeptness at bureaucratic intrigue, a virtual necessity in his position; Menzies' efforts as chief had a major role in winning the Second World War, and certainly earned Churchill's trust, as evidenced by nearly 1,500 meetings with the prime minister during its duration.''C: The Secret Life of Sir Stewart Graham Menzies, Spymaster to Winston Churchill'', by Anthony Cave Brown, 1987

Marriages

Menzies' first marriage was in 1918 to Lady Avice Ela Muriel Sackville, younger daughter of Gilbert Sackville, 8th Earl De La Warr and Lady Muriel Agnes Brassey, daughter of Thomas Brassey, 1st Earl Brassey. They were divorced in 1931.Mosley, Charles, editor. Burke's Peerage, Baronetage & Knightage, 107th edition, 3 volumes. Wilmington, Delaware, U.S.: Burke's Peerage (Genealogical Books) Ltd, 2003. He next married Pamela Thetis Garton (née Beckett), on 13 December 1932, fourth daughter of Rupert Evelyn Beckett by his wife Muriel Helen Florence Paget, daughter of Lord Berkeley Charles Sydney Paget, himself a younger son of the 2nd Marquess of Anglesey. Garton was an invalid for many years, suffering from clinical depression andanorexia nervosa

Anorexia nervosa (AN), often referred to simply as anorexia, is an eating disorder characterized by Calorie restriction, food restriction, body image disturbance, fear of gaining weight, and an overpowering desire to be thin.

Individuals wit ...

. She had Menzies' only child.

His third marriage was in 1952 to Audrey Clara Lilian Latham, formerly wife of Sir Henry Birkin, 2nd Bt., Lord Edward Hay, and Niall Chaplin, and daughter of Sir Thomas Paul Latham, 1st Bt. Stewart and Audrey were both over age 50 at the time of their marriage, her fourth. Each had separate estates (his in Wiltshire

Wiltshire (; abbreviated to Wilts) is a ceremonial county in South West England. It borders Gloucestershire to the north, Oxfordshire to the north-east, Berkshire to the east, Hampshire to the south-east, Dorset to the south, and Somerset to ...

, west of London, hers in Essex

Essex ( ) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in the East of England, and one of the home counties. It is bordered by Cambridgeshire and Suffolk to the north, the North Sea to the east, Kent across the Thames Estuary to the ...

, east of London), and they for the most part lived separately, but they met in London for dinner each Wednesday.Cave Brown

Anthony Cave Brown also reported that Menzies had a long-standing affair with one of his secretaries, which he ended upon retirement (and presumably remarriage) in 1952; the secretary apparently tried to kill herself at that time.

Menzies died on 29 May 1968.

Honours and awards

Notes

References

* Anthony Cave Brown, ''Bodyguard of Lies'', 1975. * Anthony Cave Brown, ''"C": The Secret Servant: The Life of Sir Stewart Menzies, Spymaster to Winston Churchill'' (Macmillan Publishing Co., 1987) * Ken Follett, "The Oldest Boy of British Intelligence", ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''NYT'') is an American daily newspaper based in New York City. ''The New York Times'' covers domestic, national, and international news, and publishes opinion pieces, investigative reports, and reviews. As one of ...

'', 27 December 1987. Three page review of Brown's biography and Mahl's book.

*

* Thomas E. Mahl, ''Desperate Deception: British Covert Operations in the United States, 1939–44'', (Brassey's Inc., 1999) .

*

{{DEFAULTSORT:Menzies, Stewart

1890 births

1968 deaths

British anti-communists

British Army major generals

British Army personnel of World War I

British Army generals of World War II

British Life Guards officers

Cold War MI6 chiefs

Cold War spies

Companions of the Distinguished Service Order

Knights Commander of the Order of St Michael and St George

Knights Commander of the Order of the Bath

People educated at Eton College

Bletchley Park people

Recipients of the Military Cross

Recipients of the Order of the Yugoslav Crown

Military personnel from London

Grenadier Guards officers

World War II spies for the United Kingdom