Staten Island Peace Conference on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Staten Island Peace Conference was a brief informal diplomatic conference held between representatives of the

The Staten Island Peace Conference was a brief informal diplomatic conference held between representatives of the

After the fleet arrived in July 1776, Admiral Howe made several attempts to open communications with

After the fleet arrived in July 1776, Admiral Howe made several attempts to open communications with

The house of Christopher Billop, on Staten Island, was selected to be the meeting place. It had been occupied by British troops for use as a barracks and was in filthy condition, but one room was cleaned and prepared for the meeting.Morris, p. 144 The arrangements included one British officer to be left on the American side as a hostage during the meeting. The congressional delegation, rather than leaving him behind the American lines, invited him to accompany them. On arrival, the delegation was escorted past a line of Hessian soldiers and into the house, where, according to Adams, a repast of claret, ham, mutton, and tongue was served.Isaacson, p. 319

The meeting lasted three hours, but the two sides were unable to find any common ground. The Americans insisted that any negotiations required the British recognition of their recently declared independence. Lord Howe stated that he did not have the authority to meet that demand.Morris, p. 145 When asked by Edward Rutledge whether he had the authority to repeal the Prohibitory Act, which authorized a naval blockade of the colonies, as had been claimed by Sullivan, Howe demurred and claimed that Sullivan was mistaken. Howe's authority included the ability to suspend its execution if the colonies agreed to make fixed contributions, instead of the taxes that Parliament had levied on them. None of that could be done unless the colonies first agreed to end hostilities.Gruber, p. 119

For most of the meeting, both sides were cordial. However, when Lord Howe expressed that he would feel America's loss "like the loss of a brother," Franklin informed him that "we will do our utmost endeavors to save your lordship that mortification."Isaacson, pp. 319–320

Lord Howe unhappily stated that he could not view the American delegates as anything but British subjects. Adams replied, "Your lordship may consider me in what light you please,... except that of a British subject." Lord Howe then spoke past Adams to Franklin and Rutledge: "Mr. Adams appears to be a decided character."

The house of Christopher Billop, on Staten Island, was selected to be the meeting place. It had been occupied by British troops for use as a barracks and was in filthy condition, but one room was cleaned and prepared for the meeting.Morris, p. 144 The arrangements included one British officer to be left on the American side as a hostage during the meeting. The congressional delegation, rather than leaving him behind the American lines, invited him to accompany them. On arrival, the delegation was escorted past a line of Hessian soldiers and into the house, where, according to Adams, a repast of claret, ham, mutton, and tongue was served.Isaacson, p. 319

The meeting lasted three hours, but the two sides were unable to find any common ground. The Americans insisted that any negotiations required the British recognition of their recently declared independence. Lord Howe stated that he did not have the authority to meet that demand.Morris, p. 145 When asked by Edward Rutledge whether he had the authority to repeal the Prohibitory Act, which authorized a naval blockade of the colonies, as had been claimed by Sullivan, Howe demurred and claimed that Sullivan was mistaken. Howe's authority included the ability to suspend its execution if the colonies agreed to make fixed contributions, instead of the taxes that Parliament had levied on them. None of that could be done unless the colonies first agreed to end hostilities.Gruber, p. 119

For most of the meeting, both sides were cordial. However, when Lord Howe expressed that he would feel America's loss "like the loss of a brother," Franklin informed him that "we will do our utmost endeavors to save your lordship that mortification."Isaacson, pp. 319–320

Lord Howe unhappily stated that he could not view the American delegates as anything but British subjects. Adams replied, "Your lordship may consider me in what light you please,... except that of a British subject." Lord Howe then spoke past Adams to Franklin and Rutledge: "Mr. Adams appears to be a decided character."

The Congressmen returned to Philadelphia and reported that Lord Howe "has no propositions to make us" and that "America is to expect nothing but total unconditional submission." John Adams learned many years later that his name was on a list of people who were specifically excluded from any pardon offers the Howes might make. Congress published the committee's report without comment. Because Lord Howe did not also publish an account of the meeting, the meeting's outcome was perceived by many as a sign of British weakness, but many Loyalists and some British observers suspected that the Congressional report had misrepresented the meeting.

One British commentator wrote of the meeting: "They met, they talked, they parted. And now nothing remains but to fight it out." Lord Howe reported the failure of the conference to his brother, and both made preparations to continue the campaign for New York City. Four days after the conference, British troops landed on Manhattan and occupied New York City.

Parliamentary debate over the terms of the diplomatic mission and its actions prompted some opposition Whig members essentially to boycott parliamentary proceedings. The next major peace effort occurred in 1778, when the British sent

The Congressmen returned to Philadelphia and reported that Lord Howe "has no propositions to make us" and that "America is to expect nothing but total unconditional submission." John Adams learned many years later that his name was on a list of people who were specifically excluded from any pardon offers the Howes might make. Congress published the committee's report without comment. Because Lord Howe did not also publish an account of the meeting, the meeting's outcome was perceived by many as a sign of British weakness, but many Loyalists and some British observers suspected that the Congressional report had misrepresented the meeting.

One British commentator wrote of the meeting: "They met, they talked, they parted. And now nothing remains but to fight it out." Lord Howe reported the failure of the conference to his brother, and both made preparations to continue the campaign for New York City. Four days after the conference, British troops landed on Manhattan and occupied New York City.

Parliamentary debate over the terms of the diplomatic mission and its actions prompted some opposition Whig members essentially to boycott parliamentary proceedings. The next major peace effort occurred in 1778, when the British sent

The Staten Island Peace Conference was a brief informal diplomatic conference held between representatives of the

The Staten Island Peace Conference was a brief informal diplomatic conference held between representatives of the British Crown

The Crown is a political concept used in Commonwealth realms. Depending on the context used, it generally refers to the entirety of the State (polity), state (or in federal realms, the relevant level of government in that state), the executive ...

and its rebellious North American colonies in the hope of bringing a rapid end to the nascent American Revolution

The American Revolution (1765–1783) was a colonial rebellion and war of independence in which the Thirteen Colonies broke from British America, British rule to form the United States of America. The revolution culminated in the American ...

. The conference took place on September 11, 1776, a few days after the British had captured Long Island and less than three months after the formal American Declaration of Independence

The Declaration of Independence, formally The unanimous Declaration of the thirteen States of America in the original printing, is the founding document of the United States. On July 4, 1776, it was adopted unanimously by the Second Continen ...

. The conference was held at Billop Manor, the residence of loyalist

Loyalism, in the United Kingdom, its overseas territories and its former colonies, refers to the allegiance to the British crown or the United Kingdom. In North America, the most common usage of the term refers to loyalty to the British Cr ...

Colonel Christopher Billop, on Staten Island, New York

Staten Island ( ) is the southernmost of the boroughs of New York City, five boroughs of New York City, coextensive with Richmond County and situated at the southernmost point of New York (state), New York. The borough is separated from the ad ...

. The participants were the British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories and Crown Dependencies.

* British national identity, the characteristics of British people and culture ...

Admiral Lord Richard Howe, and members of the Second Continental Congress

The Second Continental Congress (1775–1781) was the meetings of delegates from the Thirteen Colonies that united in support of the American Revolution and American Revolutionary War, Revolutionary War, which established American independence ...

John Adams

John Adams (October 30, 1735 – July 4, 1826) was a Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father and the second president of the United States from 1797 to 1801. Before Presidency of John Adams, his presidency, he was a leader of ...

, Benjamin Franklin

Benjamin Franklin (April 17, 1790) was an American polymath: a writer, scientist, inventor, statesman, diplomat, printer, publisher and Political philosophy, political philosopher.#britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Wood, 2021 Among the m ...

, and Edward Rutledge.

Upon being placed in command of British land forces in the Colonies, Lord Howe had sought authority to resolve the conflict peacefully. However, his power to negotiate was by design extremely limited, which left the Congressional delegation pessimistic over a summary resolution. The Americans insisted on recognition of their recently declared independence, which Howe was unable to grant. After just three hours, the delegates retired, and the British resumed their military campaign

A military campaign is large-scale long-duration significant military strategy plan incorporating a series of interrelated military operations or battles forming a distinct part of a larger conflict often called a war. The term derives from th ...

to control New York City

New York, often called New York City (NYC), is the most populous city in the United States, located at the southern tip of New York State on one of the world's largest natural harbors. The city comprises five boroughs, each coextensive w ...

.

Background

When British authorities were planning how to deal with their rebellious North American colonies in late 1775 and early 1776, they decided to send a large military expedition to occupyNew York City

New York, often called New York City (NYC), is the most populous city in the United States, located at the southern tip of New York State on one of the world's largest natural harbors. The city comprises five boroughs, each coextensive w ...

. Two brothers, Admiral Lord Richard Howe and General William Howe, were given command of the naval and land aspects of the operation respectively. Since they believed that it might still be possible to end the dispute without further violence, the Howe brothers insisted on being granted diplomatic powers in addition to their military roles.

Admiral Howe had previously discussed colonial grievances informally with Benjamin Franklin

Benjamin Franklin (April 17, 1790) was an American polymath: a writer, scientist, inventor, statesman, diplomat, printer, publisher and Political philosophy, political philosopher.#britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Wood, 2021 Among the m ...

in 1774 and 1775, without resolution. General Howe believed that the problem of colonial taxation could be resolved with the retention of the supremacy of Parliament.Fischer, p. 74

At first, King George III

George III (George William Frederick; 4 June 173829 January 1820) was King of Great Britain and King of Ireland, Ireland from 25 October 1760 until his death in 1820. The Acts of Union 1800 unified Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain and ...

reluctantly agreed to grant the Howes limited powers, but Lord George Germain took a harder line by insisting for the Howes not to be given any powers that might be seen as giving in to the colonial demands for relief from taxation without representation or the so-called Intolerable Acts

The Intolerable Acts, sometimes referred to as the Insufferable Acts or Coercive Acts, were a series of five punitive laws passed by the British Parliament in 1774 after the Boston Tea Party. The laws aimed to punish Massachusetts colonists fo ...

. As a consequence, the Howes were granted the ability only to issue pardons and amnesties, not to make any substantive concessions.Fischer, p. 73 The commissioners were also mandated to seek dissolution of the Continental Congress

The Continental Congress was a series of legislature, legislative bodies, with some executive function, for the Thirteen Colonies of British America, Great Britain in North America, and the newly declared United States before, during, and after ...

, the re-establishment of the prewar colonial assemblies, the acceptance of the terms of Lord North's Conciliatory Resolution

The Conciliatory Resolution was a resolution proposed by Lord North and passed by the British Parliament in February 1775, in an attempt to reach a peaceful settlement with the Thirteen Colonies about two months prior to the outbreak of the Americ ...

regarding self-taxation, and the promise of a further discussion of colonial grievances. No concessions could be made unless hostilities were ended, and colonial assemblies made specific admissions of parliamentary supremacy.

After the fleet arrived in July 1776, Admiral Howe made several attempts to open communications with

After the fleet arrived in July 1776, Admiral Howe made several attempts to open communications with Continental Army

The Continental Army was the army of the United Colonies representing the Thirteen Colonies and later the United States during the American Revolutionary War. It was formed on June 14, 1775, by a resolution passed by the Second Continental Co ...

General George Washington

George Washington (, 1799) was a Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father and the first president of the United States, serving from 1789 to 1797. As commander of the Continental Army, Washington led Patriot (American Revoluti ...

. Two attempts to deliver letters to Washington were rebuffed because Howe had refused to recognize Washington's title. Washington, however, agreed to meet in person with one of Howe's adjutants, Colonel James Patterson. In the meeting on July 20, Washington learned that the Howes' diplomatic powers were essentially limited to the granting of pardons; Washington responded that the Americans had not committed any faults and so did not need pardons.

Lord Howe then sent a letter to Benjamin Franklin that detailed a proposal for a truce and offers of pardons. After Franklin read the letter in Congress on July 30, he wrote back to the Admiral, "Directing pardons to be offered to the colonies, who are the very parties injured,... can have no other effect than that of increasing our resentments. It is impossible we should think of submission to a government that has with the most wanton barbarity and cruelty burnt our defenseless town,... excited the savages to massacre our peaceful farmers, and our slaves to murder their masters, and is even now bringing foreign mercenaries

Foreign may refer to:

Government

* Foreign policy, how a country interacts with other countries

* Ministry of Foreign Affairs, in many countries

** Foreign Office, a department of the UK government

** Foreign office and foreign minister

* United S ...

to deluge our settlements with blood."Isaacson, p. 317 He also pointed out that "you once gave me expectations that reconciliation might take place." Howe was apparently somewhat taken aback by Franklin's forceful response.

During the Battle of Long Island

The Battle of Long Island, also known as the Battle of Brooklyn and the Battle of Brooklyn Heights, was an action of the American Revolutionary War fought on August 27, 1776, at and near the western edge of Long Island in present-day Brooklyn ...

on August 27, 1776, British forces successfully occupied western Long Island

Long Island is a densely populated continental island in southeastern New York (state), New York state, extending into the Atlantic Ocean. It constitutes a significant share of the New York metropolitan area in both population and land are ...

(modern Brooklyn

Brooklyn is a Boroughs of New York City, borough of New York City located at the westernmost end of Long Island in the New York (state), State of New York. Formerly an independent city, the borough is coextensive with Kings County, one of twelv ...

), which compelled Washington to withdraw his army to Manhattan

Manhattan ( ) is the most densely populated and geographically smallest of the Boroughs of New York City, five boroughs of New York City. Coextensive with New York County, Manhattan is the County statistics of the United States#Smallest, larg ...

. General Howe then paused to consolidate his gains, and the brothers decided to make a diplomatic overture. During the battle, they had captured several high-ranking Continental Army officers, including Major General John Sullivan. The Howes managed to convince Sullivan that a conference with members of the Continental Congress might yield fruit and released him on parole to deliver a message to the Congress in Philadelphia

Philadelphia ( ), colloquially referred to as Philly, is the List of municipalities in Pennsylvania, most populous city in the U.S. state of Pennsylvania and the List of United States cities by population, sixth-most populous city in the Unit ...

that proposed an informal meeting to discuss ending the armed conflict between Britain and its rebellious colonies. After Sullivan's speech to Congress, John Adams

John Adams (October 30, 1735 – July 4, 1826) was a Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father and the second president of the United States from 1797 to 1801. Before Presidency of John Adams, his presidency, he was a leader of ...

cynically commented on this diplomatic attempt by calling Sullivan a "decoy-duck" and accusing the British of sending Sullivan "to seduce us into a renunciation of our independence." Others noted that it appeared to be an attempt to blame Congress for prolonging the war.

Congress, however, agreed to send three of its members (Adams, Benjamin Franklin, and Edward Rutledge) to a conference with Lord Howe. They were instructed "to ask a few Questions and take owe'sAnswers" but had no further authority.Gruber, p. 118 When Howe learned of the committee's limited authority, he briefly considered calling the meeting off but decided to proceed after he had discussed with his brother. None of the commissioners believed that the conference would amount to anything.Trevelyan, p. 261

Lord Howe initially sought to meet with the men as private citizens since British policy did not recognize the Congress as a legitimate authority. For the conference to take place, he agreed to the American demand to be recognized as official representatives of the Congress.

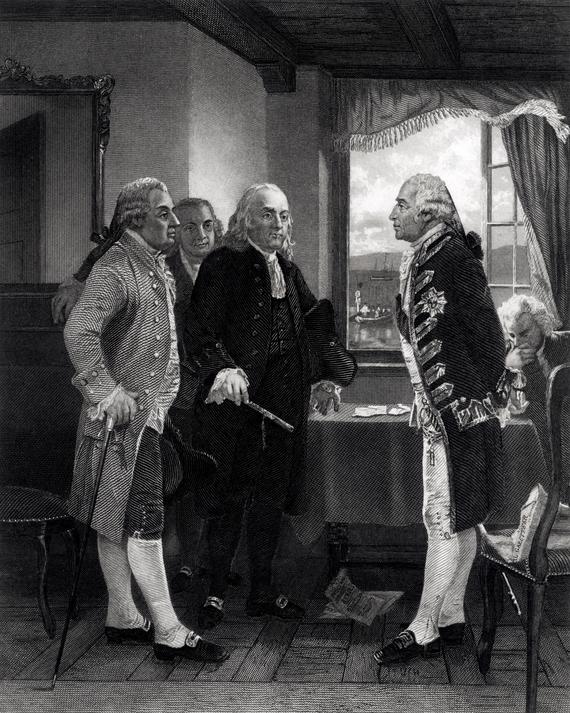

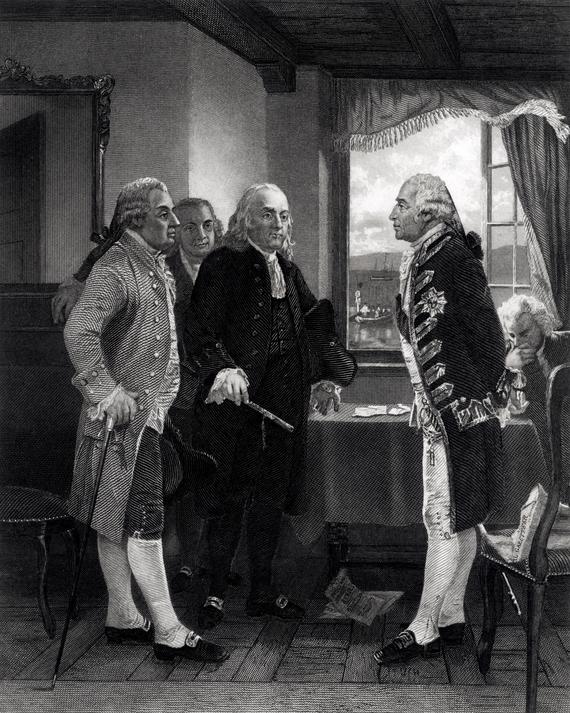

Meeting

The house of Christopher Billop, on Staten Island, was selected to be the meeting place. It had been occupied by British troops for use as a barracks and was in filthy condition, but one room was cleaned and prepared for the meeting.Morris, p. 144 The arrangements included one British officer to be left on the American side as a hostage during the meeting. The congressional delegation, rather than leaving him behind the American lines, invited him to accompany them. On arrival, the delegation was escorted past a line of Hessian soldiers and into the house, where, according to Adams, a repast of claret, ham, mutton, and tongue was served.Isaacson, p. 319

The meeting lasted three hours, but the two sides were unable to find any common ground. The Americans insisted that any negotiations required the British recognition of their recently declared independence. Lord Howe stated that he did not have the authority to meet that demand.Morris, p. 145 When asked by Edward Rutledge whether he had the authority to repeal the Prohibitory Act, which authorized a naval blockade of the colonies, as had been claimed by Sullivan, Howe demurred and claimed that Sullivan was mistaken. Howe's authority included the ability to suspend its execution if the colonies agreed to make fixed contributions, instead of the taxes that Parliament had levied on them. None of that could be done unless the colonies first agreed to end hostilities.Gruber, p. 119

For most of the meeting, both sides were cordial. However, when Lord Howe expressed that he would feel America's loss "like the loss of a brother," Franklin informed him that "we will do our utmost endeavors to save your lordship that mortification."Isaacson, pp. 319–320

Lord Howe unhappily stated that he could not view the American delegates as anything but British subjects. Adams replied, "Your lordship may consider me in what light you please,... except that of a British subject." Lord Howe then spoke past Adams to Franklin and Rutledge: "Mr. Adams appears to be a decided character."

The house of Christopher Billop, on Staten Island, was selected to be the meeting place. It had been occupied by British troops for use as a barracks and was in filthy condition, but one room was cleaned and prepared for the meeting.Morris, p. 144 The arrangements included one British officer to be left on the American side as a hostage during the meeting. The congressional delegation, rather than leaving him behind the American lines, invited him to accompany them. On arrival, the delegation was escorted past a line of Hessian soldiers and into the house, where, according to Adams, a repast of claret, ham, mutton, and tongue was served.Isaacson, p. 319

The meeting lasted three hours, but the two sides were unable to find any common ground. The Americans insisted that any negotiations required the British recognition of their recently declared independence. Lord Howe stated that he did not have the authority to meet that demand.Morris, p. 145 When asked by Edward Rutledge whether he had the authority to repeal the Prohibitory Act, which authorized a naval blockade of the colonies, as had been claimed by Sullivan, Howe demurred and claimed that Sullivan was mistaken. Howe's authority included the ability to suspend its execution if the colonies agreed to make fixed contributions, instead of the taxes that Parliament had levied on them. None of that could be done unless the colonies first agreed to end hostilities.Gruber, p. 119

For most of the meeting, both sides were cordial. However, when Lord Howe expressed that he would feel America's loss "like the loss of a brother," Franklin informed him that "we will do our utmost endeavors to save your lordship that mortification."Isaacson, pp. 319–320

Lord Howe unhappily stated that he could not view the American delegates as anything but British subjects. Adams replied, "Your lordship may consider me in what light you please,... except that of a British subject." Lord Howe then spoke past Adams to Franklin and Rutledge: "Mr. Adams appears to be a decided character."

Aftermath

The Congressmen returned to Philadelphia and reported that Lord Howe "has no propositions to make us" and that "America is to expect nothing but total unconditional submission." John Adams learned many years later that his name was on a list of people who were specifically excluded from any pardon offers the Howes might make. Congress published the committee's report without comment. Because Lord Howe did not also publish an account of the meeting, the meeting's outcome was perceived by many as a sign of British weakness, but many Loyalists and some British observers suspected that the Congressional report had misrepresented the meeting.

One British commentator wrote of the meeting: "They met, they talked, they parted. And now nothing remains but to fight it out." Lord Howe reported the failure of the conference to his brother, and both made preparations to continue the campaign for New York City. Four days after the conference, British troops landed on Manhattan and occupied New York City.

Parliamentary debate over the terms of the diplomatic mission and its actions prompted some opposition Whig members essentially to boycott parliamentary proceedings. The next major peace effort occurred in 1778, when the British sent

The Congressmen returned to Philadelphia and reported that Lord Howe "has no propositions to make us" and that "America is to expect nothing but total unconditional submission." John Adams learned many years later that his name was on a list of people who were specifically excluded from any pardon offers the Howes might make. Congress published the committee's report without comment. Because Lord Howe did not also publish an account of the meeting, the meeting's outcome was perceived by many as a sign of British weakness, but many Loyalists and some British observers suspected that the Congressional report had misrepresented the meeting.

One British commentator wrote of the meeting: "They met, they talked, they parted. And now nothing remains but to fight it out." Lord Howe reported the failure of the conference to his brother, and both made preparations to continue the campaign for New York City. Four days after the conference, British troops landed on Manhattan and occupied New York City.

Parliamentary debate over the terms of the diplomatic mission and its actions prompted some opposition Whig members essentially to boycott parliamentary proceedings. The next major peace effort occurred in 1778, when the British sent commissioners

A commissioner (commonly abbreviated as Comm'r) is, in principle, a member of a commission or an individual who has been given a Wiktionary: commission, commission (official charge or authority to do something).

In practice, the title of commissi ...

led by the Earl of Carlisle to occupied Philadelphia. They were authorized to treat with Congress as a body and offered self-government that was roughly equivalent to dominion

A dominion was any of several largely self-governance, self-governing countries of the British Empire, once known collectively as the ''British Commonwealth of Nations''. Progressing from colonies, their degrees of self-governing colony, colon ...

status. The effort was undermined by the planned withdrawal of British troops from Philadelphia and by American demands that the commissioners were not authorized to grant.

The house in which the conference took place is now preserved as a museum within Conference House Park, a city park. It is a National Historic Landmark

A National Historic Landmark (NHL) is a National Register of Historic Places property types, building, district, object, site, or structure that is officially recognized by the Federal government of the United States, United States government f ...

, and is listed on the National Register of Historic Places

The National Register of Historic Places (NRHP) is the Federal government of the United States, United States federal government's official United States National Register of Historic Places listings, list of sites, buildings, structures, Hist ...

.National Register Information System

The National Register Information System (NRIS) is a database of properties that have been listed on the United States National Register of Historic Places. The database includes more than 84,000 entries of historic sites that are currently listed ...

References

Notes Sources * * * * * * * * * * * * * Further reading * {{Coord, 40, 30, 10.3, N, 74, 15, 13.6, W, display=title, region:US-NY_type:landmark 1776 in the United States 1776 in international relations 18th-century diplomatic conferences American Revolution Diplomacy during the American Revolutionary War Diplomatic conferences in the United States New York (state) in the American Revolution History of Staten Island 1776 in New York (state) 1776 conferences United States diplomacy