State Funeral Of Horatio Nelson on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The breakdown of the year-long peace that followed the

The breakdown of the year-long peace that followed the

It was announced on 27 December that the state funeral would take place on 9 January 1806, and would be preceded by a

It was announced on 27 December that the state funeral would take place on 9 January 1806, and would be preceded by a

Before dawn the next morning, Thursday 9 January, crowds began to gather along the processional route, some having waited outside all night to secure a good view. The owners of many of the overlooking houses had rented out their rooms at exorbitant prices to wealthier onlookers;Adkin 2005, p. 550 one room in

Before dawn the next morning, Thursday 9 January, crowds began to gather along the processional route, some having waited outside all night to secure a good view. The owners of many of the overlooking houses had rented out their rooms at exorbitant prices to wealthier onlookers;Adkin 2005, p. 550 one room in

Extensive work had been undertaken inside St Paul's Cathedral in preparation for the funeral. Large wooden galleries had been constructed surrounding the crossing under the dome, to seat around 9,000 people, a larger congregation than at any previous state funeral. Another gallery was built below the organ for the large choir of about 80 singers, drawn from the choirs of St Paul's, Westminster Abbey and the

Extensive work had been undertaken inside St Paul's Cathedral in preparation for the funeral. Large wooden galleries had been constructed surrounding the crossing under the dome, to seat around 9,000 people, a larger congregation than at any previous state funeral. Another gallery was built below the organ for the large choir of about 80 singers, drawn from the choirs of St Paul's, Westminster Abbey and the

Vice-Admiral

Vice admiral is a senior naval flag officer rank, usually equivalent to lieutenant general and air marshal. A vice admiral is typically senior to a rear admiral and junior to an admiral.

Australia

In the Royal Australian Navy, the rank of vic ...

Horatio Nelson, 1st Viscount Nelson

Horatio Nelson, 1st Viscount Nelson, 1st Duke of Bronte ( – 21 October 1805) was a Royal Navy officer whose leadership, grasp of strategy and unconventional tactics brought about a number of decisive British naval victories during the French ...

, was given a state funeral

A state funeral is a public funeral ceremony, observing the strict rules of protocol, held to honour people of national significance. State funerals usually include much pomp and ceremony as well as religious overtones and distinctive elements o ...

in London

London is the Capital city, capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of both England and the United Kingdom, with a population of in . London metropolitan area, Its wider metropolitan area is the largest in Wester ...

on 9 January 1806. It was the first to be held at St Paul's Cathedral

St Paul's Cathedral, formally the Cathedral Church of St Paul the Apostle, is an Anglican cathedral in London, England, the seat of the Bishop of London. The cathedral serves as the mother church of the Diocese of London in the Church of Engl ...

and was the grandest of any non-royal person to that date. Nelson was shot and killed on 21 October 1805, aged 47, aboard his flagship

A flagship is a vessel used by the commanding officer of a group of navy, naval ships, characteristically a flag officer entitled by custom to fly a distinguishing flag. Used more loosely, it is the lead ship in a fleet of vessels, typically ...

, , during the Battle of Trafalgar

The Battle of Trafalgar was a naval engagement that took place on 21 October 1805 between the Royal Navy and a combined fleet of the French Navy, French and Spanish Navy, Spanish navies during the War of the Third Coalition. As part of Na ...

, part of the Napoleonic Wars

{{Infobox military conflict

, conflict = Napoleonic Wars

, partof = the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars

, image = Napoleonic Wars (revision).jpg

, caption = Left to right, top to bottom:Battl ...

. The successful outcome of the battle against a larger Franco-Spanish fleet, secured British naval supremacy and ended the threat of a French invasion of the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Northwestern Europe, off the coast of European mainland, the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

. Nelson's previous victories meant that he was revered as a national hero and news of his death was met with near universal shock and mourning. The scale of his funeral was not only an expression of public sentiment, but also an attempt by the British Government

His Majesty's Government, abbreviated to HM Government or otherwise UK Government, is the central government, central executive authority of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland.

to improve the perception of its prosecution of the war.

Background

The breakdown of the year-long peace that followed the

The breakdown of the year-long peace that followed the Treaty of Amiens

The Treaty of Amiens (, ) temporarily ended hostilities between France, the Spanish Empire, and the United Kingdom at the end of the War of the Second Coalition. It marked the end of the French Revolutionary Wars; after a short peace it set t ...

led to the United Kingdom declaring war on France in May 1803, a conflict that would become known as the War of the Third Coalition

The War of the Third Coalition () was a European conflict lasting from 1805 to 1806 and was the first conflict of the Napoleonic Wars. During the war, First French Empire, France and French client republic, its client states under Napoleon I an ...

. Nelson was tasked with reestablishing a naval blockade

A blockade is the act of actively preventing a country or region from receiving or sending out food, supplies, weapons, or communications, and sometimes people, by military force.

A blockade differs from an embargo or sanction, which are ...

of the French fleet at Toulon

Toulon (, , ; , , ) is a city in the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region of southeastern France. Located on the French Riviera and the historical Provence, it is the prefecture of the Var (department), Var department.

The Commune of Toulon h ...

. In the meantime, Napoleon planned an invasion of the United Kingdom, assembling a large number of boats and an army at the Channel ports

The Channel Ports are seaports in southern England and northern France, which allow for short crossings of the English Channel. There is no formal definition, but there is a general understanding of the term. Some ferry companies divide their rout ...

and devising a plan to lure the British fleet away. Accordingly, in March 1805, Pierre-Charles Villeneuve

Pierre-Charles-Jean-Baptiste-Silvestre de Villeneuve (; 31 December 1763 – 22 April 1806) was a French Navy officer who served during the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars. He was in command of a French and Spanish fleet which was ...

, the French commander, evaded the blockade and headed for the West Indies

The West Indies is an island subregion of the Americas, surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean and the Caribbean Sea, which comprises 13 independent island country, island countries and 19 dependent territory, dependencies in thr ...

with Nelson in pursuit. Returning again, Villeneuve decided not to risk Napoleon's plan for the combined French and Spanish fleet to dominate the English Channel and instead put into Cadiz with Nelson's fleet blocking outside. In a final attempt to break out, the opposing fleets met off Cape Trafalgar

Cape Trafalgar (; ) is a headland in the Province of Cádiz in the southwest of Spain. The 1805 naval Battle of Trafalgar, in which the Royal Navy commanded by Admiral Horatio Nelson decisively defeated Napoleon's combined Spanish and French f ...

on 21 October 1805, where the outnumbered British inflicted a devastating defeat on the Franco-Spanish.Haythornethwaite 1990, p. 22 However, at the height of the action, Nelson was shot by a French sharpshooter

A sharpshooter is one who is highly proficient at firing firearms or other projectile weapons accurately. Military units composed of sharpshooters were important factors in 19th-century combat. Along with " marksman" and "expert", "sharpshooter" ...

and died of his wound before the end of the battle. By this time, Napoleon had already decided to abandon the invasion, but Trafalgar ensured that it could not be attempted at any later date.

Return to England

Nelson died at around 4:30 pm on 21 October 1805 during the final stages of the battle. As he lay dying, he had asked the captain of the ''Victory'',Thomas Hardy

Thomas Hardy (2 June 1840 – 11 January 1928) was an English novelist and poet. A Literary realism, Victorian realist in the tradition of George Eliot, he was influenced both in his novels and in his poetry by Romanticism, including the poetry ...

, not to have him thrown overboard, as it was customary in combat for the dead of whatever rank to be quickly dropped over the ship's side without ceremony. Nelson's deputy, Vice-Admiral Cuthbert Collingwood

Vice Admiral Cuthbert Collingwood, 1st Baron Collingwood (26 September 1748 – 7 March 1810) was an admiral of the Royal Navy. Collingwood was born in Newcastle upon Tyne and later lived in Morpeth, Northumberland. He entered the Royal Navy at ...

, wanted to return Nelson's body to Britain by the quickest means possible and nominated the fast frigate

A frigate () is a type of warship. In different eras, the roles and capabilities of ships classified as frigates have varied.

The name frigate in the 17th to early 18th centuries was given to any full-rigged ship built for speed and maneuvera ...

, for the task. However, the crew of ''Victory'' were aghast at the idea of surrendering their admiral to another ship and through their boatswain

A boatswain ( , ), bo's'n, bos'n, or bosun, also known as a deck boss, or a qualified member of the deck department, or the third hand on a fishing vessel, is the most senior Naval rating, rate of the deck department and is responsible for the ...

's mate, lobbied Collingwood to be allowed to bring Nelson home in his own flagship, which was finally agreed.

''Victorys surgeon, William Beatty, had to devise a way of preserving the corpse for the lengthy voyage to England. The usual method was to seal the corpse in a lead coffin, but there was insufficient lead on board to make one. Beatty therefore obtained the largest water cask

A barrel or cask is a hollow cylindrical container with a bulging center, longer than it is wide. They are traditionally made of wooden staves and bound by wooden or metal hoops. The word vat is often used for large containers for liquids ...

on the ship, known as a "leaguer", for the purpose. Standing on its end, it was lashed to the base of the main mast on the middle gun deck. Nelson's queue was removed and later sent to his mistress

Mistress is the feminine form of the English word "master" (''master'' + ''-ess'') and may refer to:

Romance and relationships

* Mistress (lover), a female lover of a married man

** Royal mistress

* Maîtresse-en-titre, official mistress of a ...

, Emma, Lady Hamilton

Dame Emma Hamilton (born Amy Lyon; 26 April 176515 January 1815), known upon moving to London as Emma Hart, and upon marriage as Lady Hamilton, was an English maid, model, dancer and actress. She began her career in London's demi-monde, beco ...

. Dr Beatty performed a brief autopsy, with the aim of determining the path of the fatal bullet. Dressed only in his long shirt, Nelson's body was lowered into the cask head first; it was then filled with brandy

Brandy is a liquor produced by distilling wine. Brandy generally contains 35–60% alcohol by volume (70–120 US proof) and is typically consumed as an after-dinner digestif. Some brandies are aged in wooden casks. Others are coloured ...

, in preference to naval rum because of its higher alcohol content

Alcohol by volume (abbreviated as alc/vol or ABV) is a common measure of the amount of Alcohol (drug), alcohol contained in a given alcoholic beverage. It is defined as the volume the ethanol in the liquid would take if separated from the rest ...

. A Royal Marine

The Royal Marines provide the United Kingdom's amphibious warfare, amphibious special operations capable commando force, one of the :Fighting Arms of the Royal Navy, five fighting arms of the Royal Navy, a Company (military unit), company str ...

sentry was posted to keep watch.

During the battle, ''Victory'' had suffered severe damage to both her hull and rigging. The hull was leaking heavily and required continuous pumping. The mizzen mast

The mast of a sailing ship, sailing vessel is a tall spar (sailing), spar, or arrangement of spars, erected more or less vertically on the median plane, median line of a ship or boat. Its purposes include carrying sails, spars, and derricks, givi ...

had been lost completely, while the main mast

The mast of a sailing vessel is a tall spar, or arrangement of spars, erected more or less vertically on the median line of a ship or boat. Its purposes include carrying sails, spars, and derricks, giving necessary height to a navigation light, ...

and fore mast

The mast of a sailing vessel is a tall spar, or arrangement of spars, erected more or less vertically on the median line of a ship or boat. Its purposes include carrying sails, spars, and derricks, giving necessary height to a navigation light, ...

had both been shot through and had to be supported by spars lashed to them. The ship began to make her way to Gibraltar

Gibraltar ( , ) is a British Overseas Territories, British Overseas Territory and British overseas cities, city located at the southern tip of the Iberian Peninsula, on the Bay of Gibraltar, near the exit of the Mediterranean Sea into the A ...

, but on the evening of 23 October, a gale with heavy squalls came in from the southwest, and the next morning, she had to be taken in tow by . On 25 October, the towing line parted in the continuing heavy weather, and another tow, this time from , was not undertaken until the following day. ''Victory'' arrived at Gibraltar on 28 October and began temporary repairs. During preparations for the voyage to England, the ship's purser obtained further supplies of brandy, as well as quantities of spirits of wine

''Aqua vitae'' (Latin for "water of life") or aqua vita is an archaic name for a strong aqueous solution of ethanol. These terms could also be applied to weak ethanol without Rectified spirit, rectification. Usage was widespread during the Mi ...

, which was a purer form of alcohol. The level of brandy was found to have dropped considerably in the cask, and it was refilled with spirits of wine. The voyage between Gibraltar and Portsmouth

Portsmouth ( ) is a port city status in the United Kingdom, city and unitary authority in Hampshire, England. Most of Portsmouth is located on Portsea Island, off the south coast of England in the Solent, making Portsmouth the only city in En ...

began on 3 November, but because of further storms, ''Victory'' didn't arrive until 4 December, during which time, the cask had to be refilled twice with a mixture of brandy and spirits.

While awaiting orders in the Solent

The Solent ( ) is a strait between the Isle of Wight and mainland Great Britain; the major historic ports of Southampton and Portsmouth lie inland of its shores. It is about long and varies in width between , although the Hurst Spit whic ...

, a lead coffin was brought on board. Once the ''Victory'' had set sail again on 11 December bound for the Thames Estuary

The Thames Estuary is where the River Thames meets the waters of the North Sea, in the south-east of Great Britain.

Limits

An estuary can be defined according to different criteria (e.g. tidal, geographical, navigational or in terms of salinit ...

, the cask was opened and Dr Beatty performed a more thorough autopsy, noting that "...all the vital parts were so perfectly healthy, and so small, that they resembled more those of a youth, than a man who had attained his forty-seventh year". Beatty concluded that death had been due to "a wound of the left pulmonary artery

A pulmonary artery is an artery in the pulmonary circulation that carries deoxygenated blood from the right side of the heart to the lungs. The largest pulmonary artery is the ''main pulmonary artery'' or ''pulmonary trunk'' from the heart, and ...

", but that damage to the spine would have ultimately been fatal within "two or three days, though his existence would have been miserable to himself, and highly distressing to the feelings of all around him". The artist Arthur William Devis

Arthur William Devis (10 August 1762 – 11 February 1822) was an English painter of history paintings and portraits. He painted portraits and historical subjects, sixty-five of which he exhibited (1779–1821) at the Royal Academy. Among his mo ...

had boarded the ship at Portsmouth and was present at the autopsy; the sketches that he made of Nelson's preserved corpse were later used in his famous painting, ''The Death of Nelson, 21 October 1805

''The'' is a grammatical article in English, denoting nouns that are already or about to be mentioned, under discussion, implied or otherwise presumed familiar to listeners, readers, or speakers. It is the definite article in English. ''The' ...

''. Following the autopsy, the body was dressed in cotton and then swathed in bandages from head to foot, before being sealed in the lead coffin. ''Victory'' was again beset with poor weather and unfavourable winds, causing her to put in at Dover

Dover ( ) is a town and major ferry port in Kent, southeast England. It faces France across the Strait of Dover, the narrowest part of the English Channel at from Cap Gris Nez in France. It lies southeast of Canterbury and east of Maidstone. ...

until 16 December, finally arriving off the Nore

The Nore is a long sandbank, bank of sand and silt running along the south-centre of the final narrowing of the Thames Estuary, England. Its south-west is the very narrow Nore Sand. Just short of the Nore's easternmost point where it fades int ...

on 23 December. Here the lead coffin was opened, the body redressed in uniform "small clothes" and a night cap, before being placed in the wooden coffin made from the mainmast of ''Orient'', the French flagship at the Battle of the Nile

The Battle of the Nile (also known as the Battle of Aboukir Bay; ) was fought between the Royal Navy and the French Navy at Abu Qir Bay, Aboukir Bay in Ottoman Egypt, Egypt between 1–3 August 1798. It was the climax of the Mediterranean ca ...

in 1798; it had been presented to Nelson by Captain Benjamin Hallowell Carew

Admiral Sir Benjamin Hallowell Carew (born Benjamin Hallowell; ?1 January 1761 – 2 September 1834) was a senior officer in the Royal Navy. He was one of the select group of officers, referred to by Lord Nelson as his " Band of Brothers", who s ...

after the battle. Nelson's coffin was then transferred to the Commissioner of Chatham Dockyard

Chatham Dockyard was a Royal Navy Dockyard located on the River Medway in Kent. Established in Chatham, Kent, Chatham in the mid-16th century, the dockyard subsequently expanded into neighbouring Gillingham, Kent, Gillingham; at its most extens ...

's yacht, ''Chatham'', where it was placed in an elaborately carved and gilded outer coffin, bearing his styles and titles, that had been made in London. With the ensign-draped coffin on deck, ''Chatham'' made her way upstream to Greenwich

Greenwich ( , , ) is an List of areas of London, area in south-east London, England, within the Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county of Greater London, east-south-east of Charing Cross.

Greenwich is notable for its maritime hi ...

. In salute, passing ships dipped their colours, riverside churches tolled their bells and the batteries at Tilbury

Tilbury is a port town in the borough of Thurrock, Essex, England. The present town was established as separate settlement in the late 19th century, on land that was mainly part of Chadwell St Mary. It contains a Tilbury Fort, 16th century fort ...

and New Tavern Forts fired minute guns.

Preparation

The news of the victory at Trafalgar and of Nelson's death arrived in London at 1 am on the morning of 6 November, having been rushed there by the commander of theschooner

A schooner ( ) is a type of sailing ship, sailing vessel defined by its Rig (sailing), rig: fore-and-aft rigged on all of two or more Mast (sailing), masts and, in the case of a two-masted schooner, the foremast generally being shorter than t ...

. Nelson had been a popular hero since the battle of Cape St Vincent in 1797. Public grief at his loss was mixed with a sense that Britain had been saved from imminent invasion. Prime Minister William Pitt the Younger

William Pitt (28 May 1759 – 23 January 1806) was a British statesman who served as the last prime minister of Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain from 1783 until the Acts of Union 1800, and then first Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, p ...

was in poor health and had just received news of the total defeat of Britain's coalition partner, the Austrian Empire

The Austrian Empire, officially known as the Empire of Austria, was a Multinational state, multinational European Great Powers, great power from 1804 to 1867, created by proclamation out of the Habsburg monarchy, realms of the Habsburgs. Duri ...

, at the Battle of Ulm

The Battle of Ulm on 16–19 October 1805 was a series of skirmishes, at the end of the Ulm Campaign, which allowed Napoleon I to trap an entire Austrian army under the command of Karl Freiherr Mack von Leiberich with minimal losses and to f ...

. For those serving in Pitt's unpopular second ministry, Trafalgar seemed to present an opportunity to improve the public perception of their handling of the war. Public sentiment certainly favoured a grand public funeral; ''The Sun'' newspaper called for one to be organised by the College of Heralds

The College of Arms, or Heralds' College, is a royal corporation consisting of professional Officer of Arms, officers of arms, with jurisdiction over England, Wales, Northern Ireland and some Commonwealth realms. The heralds are appointed by the ...

, with a great procession of admirals, veterans, soldiers and civic dignitaries.

Pitt accordingly summoned Sir Isaac Heard

Sir Isaac Heard ( 1730 – 29 April 1822) was a British officer of arms who served as appointed Garter Principal King of Arms, from 1784 until his death in 1822 the senior Officer of Arms of the College of Arms in London. In this role, he o ...

, the Garter Principal King of Arms

Garter Principal King of Arms (also Garter King of Arms or simply Garter) is the senior king of arms and officer of arms of the College of Arms, the heraldic authority with jurisdiction over England, Wales and Northern Ireland. The position has ...

and together with three senior ministers, began preparations, which included bestowing an earldom on Nelson's brother, William Nelson and proposing a new order of chivalry

An order of chivalry, order of knighthood, chivalric order, or equestrian order is a society, fellowship and college of knights, typically founded during or inspired by the original Catholic military orders of the Crusades ( 1099–1291) and ...

. Horatio Nelson himself had requested a private funeral at Burnham Thorpe

Burnham Thorpe is a village and civil parish in the English county of Norfolk. It is famous for being the birthplace of Vice Admiral Horatio Nelson, victor at the Battle of Trafalgar and one of Britain's greatest heroes. At the time of his bi ...

where his parents were buried, with the caveat; "unless His Majesty signify it to be his pleasure that my body shall be interred elsewhere".

Although Westminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey, formally titled the Collegiate Church of Saint Peter at Westminster, is an Anglican church in the City of Westminster, London, England. Since 1066, it has been the location of the coronations of 40 English and British m ...

had traditionally been the resting place of national worthies, by the start of the 19th-century there was very little space left for the sort of grand monument to Nelson envisaged by the government. In 1793, the Dean and Chapter of St Paul's had finally been coerced into accepting secular monuments into the cathedral, which they had previously opposed on theological grounds. Accordingly, Lord Hawkesbury, the Home Secretary

The secretary of state for the Home Department, more commonly known as the home secretary, is a senior minister of the Crown in the Government of the United Kingdom and the head of the Home Office. The position is a Great Office of State, maki ...

, wrote to the king suggesting St Paul's as an appropriate venue for the funeral:

The king replied with his approval on 11 November. Shortly afterwards, the unpopular Prince of Wales

Prince of Wales (, ; ) is a title traditionally given to the male heir apparent to the History of the English monarchy, English, and later, the British throne. The title originated with the Welsh rulers of Kingdom of Gwynedd, Gwynedd who, from ...

(later King George IV

George IV (George Augustus Frederick; 12 August 1762 – 26 June 1830) was King of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and King of Hanover from 29 January 1820 until his death in 1830. At the time of his accession to the throne, h ...

), announced that he would be the chief mourner, which William Nelson assented to, but the government were appalled at the suggestion and referred the matter to the king, who ruled that a naval officer should fill the role. The two most senior officers were the First Lord of the Admiralty

First Lord of the Admiralty, or formally the Office of the First Lord of the Admiralty, was the title of the political head of the English and later British Royal Navy. He was the government's senior adviser on all naval affairs, responsible f ...

, Lord Barham

Admiral Charles Middleton, 1st Baron Barham, PC (14 October 172617 June 1813) was a Royal Navy officer and politician. As a junior officer he saw action during the Seven Years' War. Middleton was given command of a guardship at the Nore, a Roy ...

and Sir Peter Parker and it was Parker who was finally appointed.

This was to be the first state funeral for a non-royal person since that of John Churchill, 1st Duke of Marlborough

General (United Kingdom), General John Churchill, 1st Duke of Marlborough, 1st Prince of Mindelheim, 1st Count of Nellenburg, Prince of the Holy Roman Empire, (26 May 1650 – 16 June 1722 Old Style and New Style dates, O.S.) was a Briti ...

in 1722, but the heralds also sought precedents in the earlier funerals of George Monck, 1st Duke of Albemarle

George Monck, 1st Duke of Albemarle (6 December 1608 3 January 1670) was an English military officer and politician who fought on both sides during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms. A prominent military figure under the Commonwealth, his support ...

in 1670 and Edward Montagu, 1st Earl of Sandwich

Edward Montagu, 1st Earl of Sandwich, (27 July 1625 – 28 May 1672), was an English military officer, politician and diplomat from Barnwell, Northamptonshire. During the First English Civil War, he served with the Parliamentarian army, and was ...

in 1672, the latter perhaps providing the model for a grand waterbourne procession on the Thames. It would be the first funeral of national importance at the cathedral since that of Sir Philip Sidney

Sir Philip Sidney (30 November 1554 – 17 October 1586) was an English poet, courtier, scholar and soldier who is remembered as one of the most prominent figures of the Elizabethan era, Elizabethan age.

His works include a sonnet sequence, ' ...

in Old St Paul's Cathedral

Old St Paul's Cathedral was the cathedral of the City of London that, until the Great Fire of London, Great Fire of 1666, stood on the site of the present St Paul's Cathedral. Built from 1087 to 1314 and dedicated to Paul of Tarsus, Saint Paul ...

in 1586 and the first true ''state'' funeral to take place there. The scale and grandeur of the ceremonial easily exceeded all those preceding events.

Lying in state

It was announced on 27 December that the state funeral would take place on 9 January 1806, and would be preceded by a

It was announced on 27 December that the state funeral would take place on 9 January 1806, and would be preceded by a lying-in-state

Lying in state is the tradition in which the body of a deceased official, such as a head of state, is placed in a state building, either outside or inside a coffin, to allow the public to pay their respects. It traditionally takes place in a m ...

for three days at the Royal Hospital for Seamen at Greenwich

Greenwich Hospital was a permanent home for retired sailors of the Royal Navy, which operated from 1692 to 1869. Its buildings, initially Greenwich Palace, in Greenwich, London, were later used by the Royal Naval College, Greenwich and the U ...

, which was a grand retirement home for needy naval veterans. Since Nelson's coffin had arrived at Greenwich, it had been locked in the Record Room at the hospital. On Saturday 4 January, the coffin was moved to the adjacent Painted Hall where the lying-in-state was to take place, and there was a private viewing for the Prince of Wales that afternoon. At 11 o'clock on the following morning, the gates were opened for public viewing. Far more people arrived than could be ushered past the coffin, despite efforts to rush mourners through. By the third day, control of the large crowd outside became such a problem that a detachment of Life Guards was summoned to restore order. When public viewing ended on 7 January, an estimated 15,000 people had filed past the coffin, which was only a fraction of those who had waited outside the hospital gates. The last mourners to be allowed in was a party of 46 seamen and 14 Royal Marines from the ''Victory'', who were loudly applauded by the crowds still hoping in vain to be admitted.

River procession

On the morning of Wednesday, 8 January, boats and barges began to gather at Greenwich Hospital wharf for the river procession that would convey Nelson's coffin upriver to Westminster. Life Guards and the GreenwichVolunteer

Volunteering is an elective and freely chosen act of an individual or group giving their time and labor, often for community service. Many volunteers are specifically trained in the areas they work, such as medicine, education, or emergency ...

s were required to keep the large crowd of onlookers in order, despite the bitter southwesterly wind, which also caused difficulties for the watermen. At 12.30, the coffin was brought in procession through a guard of the Deptford Volunteers to the King's Stairs and loaded aboard the funeral barge, which had originally been built for King Charles II. It was covered in black velvet, and embellished with black feathers and heraldic devices. The Clarenceaux King of Arms

Clarenceux King of Arms, historically often spelled Clarencieux (both pronounced ), is an officer of arms at the College of Arms in London. Clarenceux is the senior of the two provincial kings of arms and his jurisdiction is that part of Engla ...

and several naval officers accompanied the coffin. The funeral barge was rowed by sailors from the ''Victory'', the other state barges were crewed by selected Greenwich Pensioners. The first state barge carried the standard and guidon supported by naval officers and heralds, while the second carried Nelson's banner and great banner and heraldic emblems. Following the funeral barge was the fourth state barge, which carried the chief mourner, Admiral Parker, together with the six assistant mourners, all senior naval officers. Following the state barges were the royal barge with officials representing the king, a barge for the lords commissioners of the Admiralty

The Board of Admiralty (1628–1964) was established in 1628 when Charles I put the office of Lord High Admiral into commission. As that position was not always occupied, the purpose was to enable management of the day-to-day operational requi ...

, one for the Lord Mayor of London

The Lord Mayor of London is the Mayors in England, mayor of the City of London, England, and the Leader of the council, leader of the City of London Corporation. Within the City, the Lord Mayor is accorded Order of precedence, precedence over a ...

and the City of London Corporation

The City of London Corporation, officially and legally the Mayor and Commonalty and Citizens of the City of London, is the local authority of the City of London, the historic centre of London and the location of much of the United Kingdom's f ...

, one for the Thames Navigation Commission

The Thames Navigation Commission managed the River Thames in southern England from 1751 to 1866. In particular, they were responsible for installing or renovating many of the Canal lock, locks on the river in the 18th and early 19th centuries

H ...

and eight representing the City livery companies. Accompanying these barges were dozens of other small vessels, some official and others filled with onlookers.

Minute guns were fired by the River Fencibles from their gunboats throughout the proceedings and when the procession reached the Tower of London

The Tower of London, officially His Majesty's Royal Palace and Fortress of the Tower of London, is a historic citadel and castle on the north bank of the River Thames in central London, England. It lies within the London Borough of Tower Hamle ...

at 2:45, the great guns on the wharf also joined the minute gun salute. All along the Thames, the banks were packed with spectators, who also crowded the decks and rigging of all the ships moored in the river. Westminster was finally reached at 3:30, the wind and squally showers having made hard work for the oarsmen. Nelson's coffin and the funeral party disembarked at Whitehall Stairs, the remaining dignitaries proceeded further upstream to Palace Yard Stairs where carriages were waiting to return them to London. The coffin was carried in procession by eight ''Victory'' seamen along Whitehall

Whitehall is a road and area in the City of Westminster, Central London, England. The road forms the first part of the A roads in Zone 3 of the Great Britain numbering scheme, A3212 road from Trafalgar Square to Chelsea, London, Chelsea. It ...

to The Admiralty

The Admiralty was a department of the Government of the United Kingdom that was responsible for the command of the Royal Navy.

Historically, its titular head was the Lord High Admiral – one of the Great Officers of State. For much of its h ...

, where it lay overnight in the Captain's Room.

Procession to St Paul's

Before dawn the next morning, Thursday 9 January, crowds began to gather along the processional route, some having waited outside all night to secure a good view. The owners of many of the overlooking houses had rented out their rooms at exorbitant prices to wealthier onlookers;Adkin 2005, p. 550 one room in

Before dawn the next morning, Thursday 9 January, crowds began to gather along the processional route, some having waited outside all night to secure a good view. The owners of many of the overlooking houses had rented out their rooms at exorbitant prices to wealthier onlookers;Adkin 2005, p. 550 one room in Fleet Street

Fleet Street is a street in Central London, England. It runs west to east from Temple Bar, London, Temple Bar at the boundary of the City of London, Cities of London and City of Westminster, Westminster to Ludgate Circus at the site of the Lo ...

was offered for 20 guinea

Guinea, officially the Republic of Guinea, is a coastal country in West Africa. It borders the Atlantic Ocean to the west, Guinea-Bissau to the northwest, Senegal to the north, Mali to the northeast, Côte d'Ivoire to the southeast, and Sier ...

s (£21). The route from Constitution Hill to St Paul's was lined by soldiers of the various Volunteer Corps of London and its suburbs. The military contingent, consisting of four infantry battalions and elements of another four, three cavalry regiments and eleven horse artillery

Horse artillery was a type of light, fast-moving, and fast-firing field artillery that consisted of light cannons or howitzers attached to light but sturdy two-wheeled carriages called caissons or limbers, with the individual crewmen riding on h ...

guns, were all commanded by General Sir David Dundas; they formed up in St James's Park

St James's Park is a urban park in the City of Westminster, central London. A Royal Park, it is at the southernmost end of the St James's area, which was named after a once isolated medieval hospital dedicated to St James the Less, now the ...

and Horse Guards Parade

Horse Guards Parade is a large Military parade, parade ground off Whitehall in central London (at British national grid reference system, grid reference ). It is the site of the annual ceremonies of Trooping the Colour, which commemorates the K ...

. Also included were 48 crewmen from the ''Victory'', 48 Greenwich Pensioners and the Royal Watermen. Meanwhile, a total of 189 carriage

A carriage is a two- or four-wheeled horse-drawn vehicle for passengers. In Europe they were a common mode of transport for the wealthy during the Roman Empire, and then again from around 1600 until they were replaced by the motor car around 1 ...

s carrying members of the royal family, relatives, official mourners and heralds were assembled in Hyde Park.

In Admiralty Yard, Nelson's coffin was loaded onto an elaborate funeral car, designed by Reverend M'Quin; the front and back of the car represented the bow and stern of HMS ''Victory'', with the coffin between them. The rest of the car was ornamented allegorical figures, heraldic emblems, ostrich feathers and the name "Trafalgar" boldly displayed. A naval ensign

Ensign most often refers to:

* Ensign (flag), a flag flown on a vessel to indicate nationality

* Ensign (rank), a navy (and former army) officer rank

Ensign or The Ensign may also refer to:

Places

* Ensign, Alberta, Alberta, Canada

* Ensign, Ka ...

flew at half mast above. As the funeral car emerged through the Admiralty gates, the embroidered velvet pall

Pall may refer to:

* Pall (funeral), a cloth used to cover a coffin

* Pall (heraldry), a Y-shaped heraldic charge

* Pall (liturgy), a piece of stiffened linen used to cover the chalice at the Eucharist

* Pall Corporation, a global business

* Pall. ...

which had covered the coffin was pulled aside "at the earnest request" of the large crowd so that they see the coffin itself. The procession moved off shortly after midday and followed a route from Whitehall to Charing Cross

Charing Cross ( ) is a junction in Westminster, London, England, where six routes meet. Since the early 19th century, Charing Cross has been the notional "centre of London" and became the point from which distances from London are measured. ...

and then along The Strand to Temple Bar, the boundary of the City of London

The City of London, also known as ''the City'', is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county and Districts of England, local government district with City status in the United Kingdom, city status in England. It is the Old town, his ...

. Here the procession was joined by the Lord Mayor of London

The Lord Mayor of London is the Mayors in England, mayor of the City of London, England, and the Leader of the council, leader of the City of London Corporation. Within the City, the Lord Mayor is accorded Order of precedence, precedence over a ...

on horseback and a further six carriages of City dignitaries.Fairburn 1806, p. 90 A contemporary account records the reaction of the people along the route:

The Highlanders with their bagpipes leading the procession arrived at St Paul's at 1:45, the funeral car arriving about 15 minutes later.

Funeral service

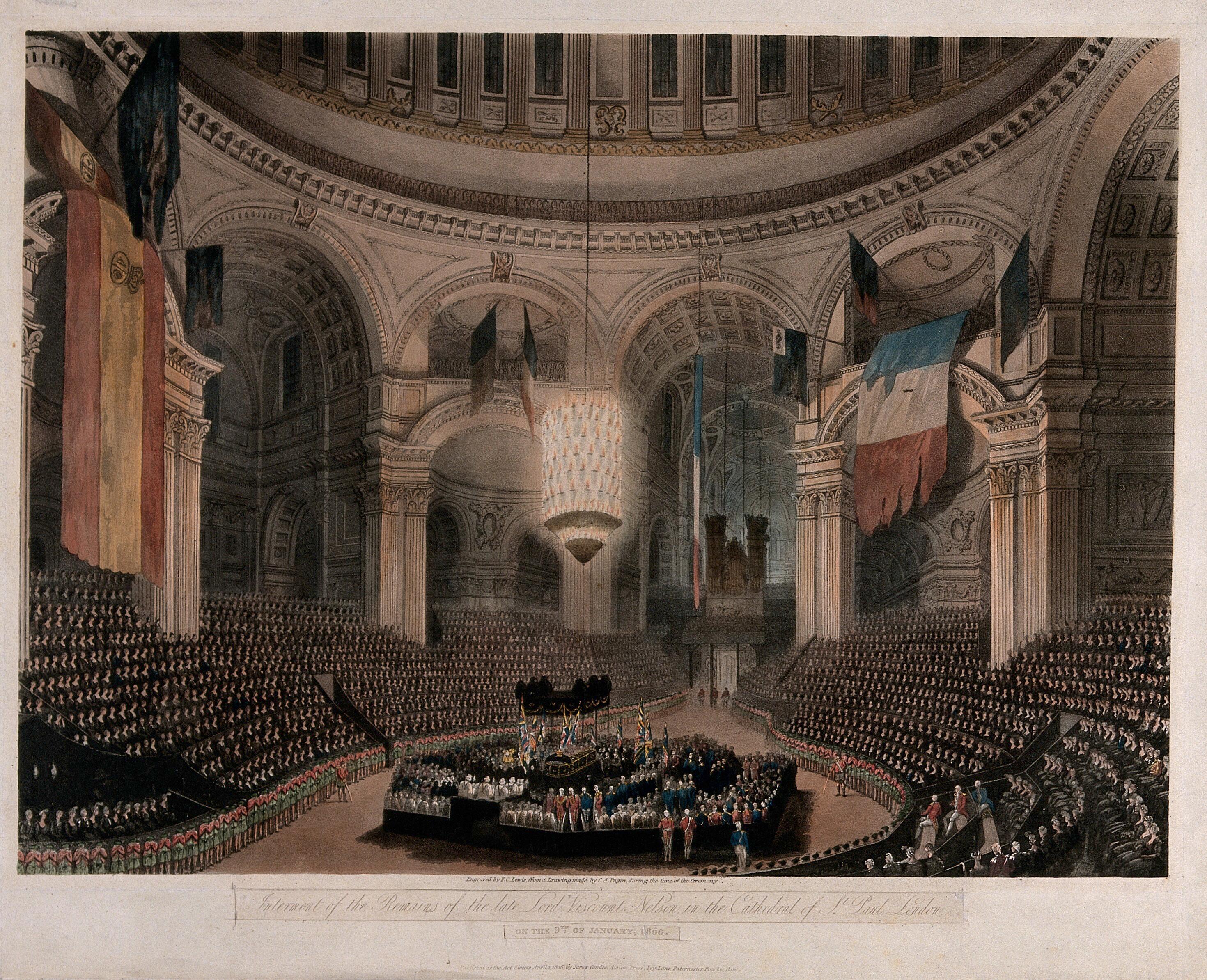

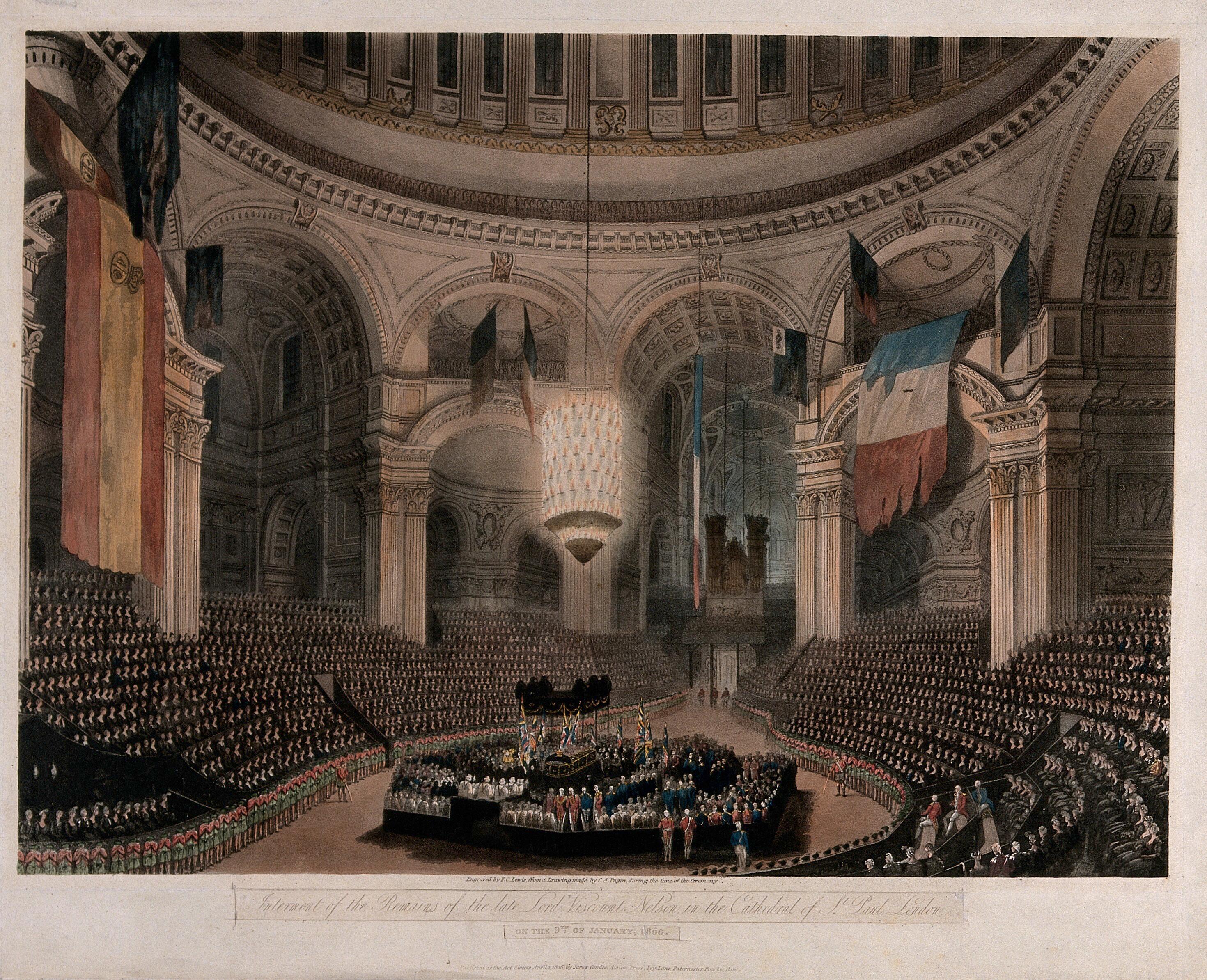

Extensive work had been undertaken inside St Paul's Cathedral in preparation for the funeral. Large wooden galleries had been constructed surrounding the crossing under the dome, to seat around 9,000 people, a larger congregation than at any previous state funeral. Another gallery was built below the organ for the large choir of about 80 singers, drawn from the choirs of St Paul's, Westminster Abbey and the

Extensive work had been undertaken inside St Paul's Cathedral in preparation for the funeral. Large wooden galleries had been constructed surrounding the crossing under the dome, to seat around 9,000 people, a larger congregation than at any previous state funeral. Another gallery was built below the organ for the large choir of about 80 singers, drawn from the choirs of St Paul's, Westminster Abbey and the Chapel Royal

A chapel royal is an establishment in the British and Canadian royal households serving the spiritual needs of the sovereign and the royal family.

Historically, the chapel royal was a body of priests and singers that travelled with the monarc ...

. Because the lengthy service would continue long after the early winter sunset, an immense chandelier

A chandelier () is an ornamental lighting device, typically with spreading branched supports for multiple lights, designed to be hung from the ceiling. Chandeliers are often ornate, and they were originally designed to hold candles, but now inca ...

had been suspended above the crossing, which was to be the focus of the liturgy. Large naval ensigns captured from French and Spanish ships at Trafalgar were hung between the piers Piers may refer to:

* Pier, a raised structure over a body of water

* Pier (architecture), an architectural support

* Piers (name), a given name and surname (including lists of people with the name)

* Piers baronets, two titles, in the baronetages ...

.

Nelson's coffin did not enter the cathedral until about 3 o'clock, because of the time taken for the distinguished mourners at the rear of the procession to leave their carriages and take their positions inside. The Duke of Clarence

Duke of Clarence was a substantive title created three times in the Peerage of England. The title Duke of Clarence and St Andrews has also been created in the Peerage of Great Britain, and Duke of Clarence and Avondale and Prince Leopold, Duke ...

, later King William IV

William IV (William Henry; 21 August 1765 – 20 June 1837) was King of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and King of Hanover from 26 June 1830 until his death in 1837. The third son of George III, William succeeded hi ...

, broke protocol and stopped outside to converse with the sailors of the ''Victory''. The liturgy combined Evensong

Evensong is a church service traditionally held near sunset focused on singing psalms and other biblical canticles. It is loosely based on the canonical hours of vespers and compline. Old English speakers translated the Latin word as , which ...

with the funeral service from the Book of Common Prayer

The ''Book of Common Prayer'' (BCP) is the title given to a number of related prayer books used in the Anglican Communion and by other Christianity, Christian churches historically related to Anglicanism. The Book of Common Prayer (1549), fi ...

and lasted more than two and a half hours. It commenced with Nelson's coffin being brought on a bier

A bier is a stand on which a corpse, coffin, or casket containing a corpse is placed to lie in state or to be carried to its final disposition.''The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language'' (American Heritage Publishing Co., In ...

with a canopy carried by six vice admiral

Vice admiral is a senior naval flag officer rank, usually equivalent to lieutenant general and air marshal. A vice admiral is typically senior to a rear admiral and junior to an admiral.

Australia

In the Royal Australian Navy, the rank of Vice ...

s in procession through the nave to the choir

A choir ( ), also known as a chorale or chorus (from Latin ''chorus'', meaning 'a dance in a circle') is a musical ensemble of singers. Choral music, in turn, is the music written specifically for such an ensemble to perform or in other words ...

, while the first of William Croft's Funeral Sentences was sung. At the climax of the service, the coffin was brought to the crossing under the dome, while the organ played a dirge composed by the organist, Thomas Attwood. The choir then sang an adaptation of George Frederick Handel

George Frideric (or Frederick) Handel ( ; baptised , ; 23 February 1685 – 14 April 1759) was a German-British Baroque composer well-known for his operas, oratorios, anthems, concerti grossi, and organ concerti.

Born in Halle, Germany, Han ...

's funeral anthem, ''His body is buried in peace''. As the coffin was lowered into the crypt by a hidden mechanism, the sailors from the ''Victory'' were supposed to cast the ship's ensign into the opening, but instead, tore the flag into pieces to keep as souvenirs. The service concluded with the traditional proclamation of Nelson's styles and titles by the Garter King at Arms. The service finished before six o'clock, but the cathedral was not cleared until nine.

Aftermath

In the crypt of St Paul's, Nelson's body was interred below an elaborate black marblesarcophagus

A sarcophagus (: sarcophagi or sarcophaguses) is a coffin, most commonly carved in stone, and usually displayed above ground, though it may also be buried. The word ''sarcophagus'' comes from the Greek language, Greek wikt:σάρξ, σάρξ ...

, which had originally been commissioned for Cardinal Thomas Wolsey

Thomas Wolsey ( ; – 29 November 1530) was an English statesman and Catholic cardinal (catholic), cardinal. When Henry VIII became King of England in 1509, Wolsey became the king's Lord High Almoner, almoner. Wolsey's affairs prospered and ...

, then appropriated by King Henry VIII

Henry VIII (28 June 149128 January 1547) was King of England from 22 April 1509 until his death in 1547. Henry is known for his Wives of Henry VIII, six marriages and his efforts to have his first marriage (to Catherine of Aragon) annulled. ...

for himself, but not used. There was a public outcry when it emerged that the four verger

A verger (or virger, so called after the staff of the office, or wandsman in British English though archaic) is a person usually a layperson, who assists in the ordering of religious services, particularly in Anglican churches.

Etymology

...

s at St Paul's were charging the public a shilling

The shilling is a historical coin, and the name of a unit of modern currency, currencies formerly used in the United Kingdom, Australia, New Zealand, other British Commonwealth countries and Ireland, where they were generally equivalent to 1 ...

each to view Nelson's tomb, pocketing as much as £300 a day between them. The funeral car was taken to St James's Palace

St James's Palace is the most senior royal palace in London, England. The palace gives its name to the Court of St James's, which is the monarch's royal court, and is located in the City of Westminster. Although no longer the principal residence ...

, where it attracted such large crowds that had to be moved to Greenwich Hospital.

Three weeks later, Parliament voted the funds for a monument to Nelson to be erected in the nave of St Paul's. This formed part of a series of some thirty monuments to Napoleonic-era naval and military officers at St Pauls which had been funded by Parliament in an apparent effort to emulate the Panthéon

The Panthéon (, ), is a monument in the 5th arrondissement of Paris, France. It stands in the Latin Quarter, Paris, Latin Quarter (Quartier latin), atop the , in the centre of the , which was named after it. The edifice was built between 1758 ...

in Paris. The completed monument by John Flaxman

John Flaxman (6 July 1755 – 7 December 1826) was a British sculptor and draughtsman, and a leading figure in British and European Neoclassicism. Early in his career, he worked as a modeller for Josiah Wedgwood's pottery. He spent several yea ...

was unveiled in 1818 and consisted of a larger than life statue of Nelson leaning on an anchor and a coiled rope, above a figure of Britannia

The image of Britannia () is the national personification of United Kingdom, Britain as a helmeted female warrior holding a trident and shield. An image first used by the Romans in classical antiquity, the Latin was the name variously appli ...

who is pointing out the admiral to two boy sailors. The inscription on the pedestal

A pedestal or plinth is a support at the bottom of a statue, vase, column, or certain altars. Smaller pedestals, especially if round in shape, may be called socles. In civil engineering, it is also called ''basement''. The minimum height o ...

mentions Nelson's "splendid and unparalleled achievements" and his "life spent in the service of his country, and terminated in the moment of victory by a glorious death".Cannadine 2005, pp. 116-118

References

Books

* * * * * * * *Articles

* * * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Nelson Horatio Nelson 1806 in London State funerals in the United Kingdom January 1806 Funerals of British people Deaths and funerals of royalty and nobility State funerals