St Bartholomew's Church, Tong on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Collegiate Church of St Bartholomew, Tong (also known as St Bartholomew's Church) is a 15th-century church in the village of

No church at Tong is mentioned in

No church at Tong is mentioned in

The present church was founded by the widowed Isabel Lingen as a

The present church was founded by the widowed Isabel Lingen as a

/ref> This was an expensive process, with the royal licence alone, granted by Henry IV at

Monasticon Anglicanum, volume 6.3, p. 1402.

/ref> The number of priests who would constitute the college was left helpfully vague: "five

''Documents'', p. 179.

/ref> (''tresdecem pauperum debilium''). At the same time, Dame Isabel had

''Documents'', p. 183.

/ref> In traditional theology, a chantry mass was distinguished as exemplifying the "special fruit" made available through Christ's sacrifice and applicable at the will and intention of the priest. This made possible remission of temporal punishment, or time spent in

The statutes list the constituents of the college. The five priests were to be

The statutes list the constituents of the college. The five priests were to be

''Documents'', p. 189.

/ref> The warden was to be the nominee of Isabel while she lived. After her death he was to elected unanimously from among the chaplains, without

Monasticon Anglicanum, volume 6.3, p. 1407.

/ref> or All of the canonical hours were to be celebrated according to the Sarum rite, from the heart and with a clear voice – ''corde et voco distincte''. The bell for MatinsThe Matins for the dead, as recited in chantries, was generally known as Dirige was rung at or before daybreak. Like all the hours, Matins might be said or sung, as directed by the warden, although music was obligatory on Sundays and other festivals so long as there were enough assistants. Immediately afterwards a mass according to the

All of the canonical hours were to be celebrated according to the Sarum rite, from the heart and with a clear voice – ''corde et voco distincte''. The bell for MatinsThe Matins for the dead, as recited in chantries, was generally known as Dirige was rung at or before daybreak. Like all the hours, Matins might be said or sung, as directed by the warden, although music was obligatory on Sundays and other festivals so long as there were enough assistants. Immediately afterwards a mass according to the

''Documents'', p. 203.

/ref> one of the founding saints of Brittany. For Isabel's parents, Ralph Lingen and Margery, it was

Priory of St Leonard, Brewood, note anchor 24.

/ref> The chaplains were exhorted to wear decent dress even when off the premises and it was recommended that they adopt uniform clothing, to be supplied annually, when meeting outsiders.

Tong College's statutes envisaged it having to work within the financial bounds of its original endowments: at Tong itself,

Tong College's statutes envisaged it having to work within the financial bounds of its original endowments: at Tong itself,

/ref> The king points out the great damage done to the national economy by constant remittances to foreign monasteries. A considerable part of the rents and dues was already committed. Lapley had been made to contribute 12 marks annually towards the huge dowry granted by Henry IV to

/ref> and at the inquiry preceding dissolution in 1546. Aged chaplains were allowed to remain at the college even if they had means of their own. The lord of the manor and the head of the Fraternity of All Saints, a religious guild, took over responsibility for the almshouses. The college warden was to hand over £20 a year to the guild wardens towards the support of the inmates, an amount still recorded in 1535.

Although there were bequests to procure masses, the only permanent chantry established at Tong after the foundation was that of Sir Henry Vernon. He made his will on 18 January 1515 and it was proved by his executors on 5 May that year. They were his sons, Richard and Arthur, a priest, as well as Thomas Rawson, a chaplain of the college.

Sir Henry Vernon instructed that he be buried in a previously designated place at Tong and that the remains of his wife, Anne Talbot, daughter of

Although there were bequests to procure masses, the only permanent chantry established at Tong after the foundation was that of Sir Henry Vernon. He made his will on 18 January 1515 and it was proved by his executors on 5 May that year. They were his sons, Richard and Arthur, a priest, as well as Thomas Rawson, a chaplain of the college.

Sir Henry Vernon instructed that he be buried in a previously designated place at Tong and that the remains of his wife, Anne Talbot, daughter of

''Documents'', p. 231.

/ref> It was stamped by William Clerk, a clerk to the Privy Seal under

''Documents'', p. 228.

/ref> who was close to the powerful and Protestant John Dudley, Viscount Lisle;

The college buildings, constructed in the 15th century, remained with the Woolrich family until after the death of James Woolrich in 1648, when they were sold by his heirs to William Pierrepont,Auden, J. E

The college buildings, constructed in the 15th century, remained with the Woolrich family until after the death of James Woolrich in 1648, when they were sold by his heirs to William Pierrepont,Auden, J. E

College of Tong, p. 205.

/ref> who had acquired the lordship of Tong through marriage. As the advowson, patronage and tithes of the church had all belonged to the college, when William Pierrepont died in 1678 he was able to leave to his youngest son, Gervase "the College, Rectory, Glebe lands and Tithes in the parish of Tong, in the County of Salop."Auden, J. E

''Documents'', p. 241.

/ref> In 1697 Gervase assigned an annuity of £12 to provide for the six widows occupying the almshouses near the west end of the church. A map of 1739 shows that the college buildings still covered a large area just south of the churchyard. It seems that a rapid deterioration occurred around mid-century. As late as 1757, William Cole, a noted

After the dissolution of the college, the church continued as the focal point of the small village of Tong, as it always had. For about a century, the advowson of the church belonged to the Wolryche family and it seems that they took the opportunity to install at least one family member: a John Wolryche is recorded as curate in 1561. For more than four decades of the Wolryche period the curacy was held by George Meeson, who appears in diocesan records as early as 1597. Meeson was buried at Tong on 25 March 1642, although his successor, William Southall, had been completing the parish register under the title of rector for a year by then.Tong Parish Register, p. 9.

After the dissolution of the college, the church continued as the focal point of the small village of Tong, as it always had. For about a century, the advowson of the church belonged to the Wolryche family and it seems that they took the opportunity to install at least one family member: a John Wolryche is recorded as curate in 1561. For more than four decades of the Wolryche period the curacy was held by George Meeson, who appears in diocesan records as early as 1597. Meeson was buried at Tong on 25 March 1642, although his successor, William Southall, had been completing the parish register under the title of rector for a year by then.Tong Parish Register, p. 9.

/ref> Sir Thomas Harries, whose family were lords of

''Ecclesiastical History'', p. 295.

/ref> An entry for 4 March 1660, just before the Restoration, shows that Hilton baptised Elizabeth Nichols in the

volume 2, p. 256.

/ref> although he quoted an anonymous correspondent of The Gentleman's Magazine for 1800 to show that it had been alive, if not understood, in the late 18th century.

St Bartholomew's, Tong, Shropshire

{{DEFAULTSORT:Tong, Saint Bartholomew's Church Buildings and structures in Shropshire Church of England church buildings in Shropshire Ewan Christian buildings Former collegiate churches in England Gothic architecture in England Grade I listed churches in Shropshire

Tong Tong may refer to:

Chinese

*Tang dynasty, a dynasty in Chinese history when transliterated from Cantonese

*Tong (organization), a type of social organization found in Chinese immigrant communities

*''tong'', pronunciation of several Chinese char ...

, Shropshire

Shropshire (; abbreviated SalopAlso used officially as the name of the county from 1974–1980. The demonym for inhabitants of the county "Salopian" derives from this name.) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in the West M ...

, England, notable for its architecture and fittings, including its fan vault

A fan vault is a form of vault used in the Gothic style, in which the ribs are all of the same curve and spaced equidistantly, in a manner resembling a fan. The initiation and propagation of this design element is strongly associated with E ...

ing in a side chapel, rare in Shropshire, and its numerous tombs. It was built on the site of a former parish church

A parish church (or parochial church) in Christianity is the Church (building), church which acts as the religious centre of a parish. In many parts of the world, especially in rural areas, the parish church may play a significant role in com ...

and was constructed as a collegiate church

In Christianity, a collegiate church is a church where the daily office of worship is maintained by a college of canons, a non-monastic or "secular" community of clergy, organised as a self-governing corporate body, headed by a dignitary bearing ...

and chantry

A chantry is an ecclesiastical term that may have either of two related meanings:

# a chantry service, a set of Christian liturgical celebrations for the dead (made up of the Requiem Mass and the Office of the Dead), or

# a chantry chapel, a b ...

on the initiative of Isabel Lingen, who acquired the advowson

Advowson () or patronage is the right in English law of a patron (avowee) to present to the diocesan bishop (or in some cases the ordinary if not the same person) a nominee for appointment to a vacant ecclesiastical benefice or church living, a ...

from Shrewsbury Abbey

The Abbey Church of the Holy Cross (commonly known as Shrewsbury Abbey) is an ancient foundation in Shrewsbury, the county town of Shropshire, England.

The Abbey was founded in 1083 as a Benedictine monastery by the Normans, Norman Earl of Shre ...

and additional endowments through royal support. Patronage remained with the lords of the manor

Lord of the manor is a title that, in Anglo-Saxon England and Norman England, referred to the landholder of a historical rural estate. The titles date to the English Feudalism, feudal (specifically English feudal barony, baronial) system. The ...

of Tong, who resided at nearby Tong Castle

Tong Castle was a very large mostly Gothic country house in Shropshire whose site is between Wolverhampton and Telford, set within a park landscaped by Capability Brown,Wolverhampton's Listed Buildings on the site of a medieval castle of the sa ...

, a short distance to the south-west, and the tombs and memorials mostly represent these families, particularly the Vernons

Ladbrokes Coral is a British gambling company. Its product offering includes sports betting, online casino, online poker, and online bingo. The Ladbrokes portion of the group was established in 1886, and Coral in 1926. In November 2016, the ...

of Haddon Hall

Haddon Hall is an English country house on the River Wye, Derbyshire, River Wye near Bakewell, Derbyshire, a former seat of the Duke of Rutland, Dukes of Rutland. It is the home of Lord Edward Manners (brother of David Manners, 11th Duke of Rut ...

, who held the lordship for more than a century. Later patrons, mostly of landed gentry

The landed gentry, or the gentry (sometimes collectively known as the squirearchy), is a largely historical Irish and British social class of landowners who could live entirely from rental income, or at least had a country estate. It is t ...

origin, added further memorials, including the Stanley Monument which is inscribed with epitaphs said to be specially written by William Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 23 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's nation ...

.

The church was the site of a minor skirmish during the English Civil War

The English Civil War or Great Rebellion was a series of civil wars and political machinations between Cavaliers, Royalists and Roundhead, Parliamentarians in the Kingdom of England from 1642 to 1651. Part of the wider 1639 to 1653 Wars of th ...

and also hosts the grave of ''Little Nell'' from Charles Dickens

Charles John Huffam Dickens (; 7 February 1812 – 9 June 1870) was an English novelist, journalist, short story writer and Social criticism, social critic. He created some of literature's best-known fictional characters, and is regarded by ...

' The Old Curiosity Shop

''The Old Curiosity Shop'' is the fourth novel by English author Charles Dickens; being one of his two novels (the other being ''Barnaby Rudge'') published along with short stories in his weekly serial ''Master Humphrey's Clock'', from 1840 t ...

, despite the character being entirely fictitious. The building is grade I listed

In the United Kingdom, a listed building is a structure of particular architectural or historic interest deserving of special protection. Such buildings are placed on one of the four statutory lists maintained by Historic England in England, Hi ...

and had its lead roof replenished with steel during 2017 to deter thieves. Due to its many monuments inside the church and ornate architecture, it is sometimes labelled as ''The Westminster Abbey of The Midlands'', often featuring as one of the best churches in The Midlands

The Midlands is the central region of England, to the south of Northern England, to the north of southern England, to the east of Wales, and to the west of the North Sea. The Midlands comprises the ceremonial counties of Derbyshire, Herefords ...

and in England.

Earlier churches at Tong

No church at Tong is mentioned in

No church at Tong is mentioned in Domesday Book

Domesday Book ( ; the Middle English spelling of "Doomsday Book") is a manuscript record of the Great Survey of much of England and parts of Wales completed in 1086 at the behest of William the Conqueror. The manuscript was originally known by ...

. At that point Roger de Montgomery

Roger de Montgomery (died 1094), also known as Roger the Great, was the first Earl of Shrewsbury, and Earl of Arundel, in Sussex. His father was Roger de Montgomery, seigneur of Montgomery, a member of the House of Montgomery, and was probab ...

, Earl of Shrewsbury, held the manor both as tenant-in-chief

In medieval and early modern Europe, a tenant-in-chief (or vassal-in-chief) was a person who held his lands under various forms of feudal land tenure directly from the king or territorial prince to whom he did homage, as opposed to holding them ...

and as manorial lord. The cartulary

A cartulary or chartulary (; Latin: ''cartularium'' or ''chartularium''), also called ''pancarta'' or ''codex diplomaticus'', is a medieval manuscript volume or roll ('' rotulus'') containing transcriptions of original documents relating to the fo ...

of Shrewsbury Abbey

The Abbey Church of the Holy Cross (commonly known as Shrewsbury Abbey) is an ancient foundation in Shrewsbury, the county town of Shropshire, England.

The Abbey was founded in 1083 as a Benedictine monastery by the Normans, Norman Earl of Shre ...

shows that Earl Roger granted it the advowson of the church at Tong and a pension of half a mark

Mark may refer to:

In the Bible

* Mark the Evangelist (5–68), traditionally ascribed author of the Gospel of Mark

* Gospel of Mark, one of the four canonical gospels and one of the three synoptic gospels

Currencies

* Mark (currency), a currenc ...

from its income, so the church must have been built between Domesday in 1087 and his death in 1094. After Robert of Bellême, 3rd Earl of Shrewsbury

Robert de Bellême ( – after 1130), seigneur de Bellême (or Belèsme), seigneur de Montgomery, viscount of the Hiémois, 3rd Earl of Shrewsbury and Count of Ponthieu, was an Anglo-Norman nobleman, and one of the most prominent figures ...

forfeited his family's lands through revolt, Tong and nearby Donington were granted by Henry I Henry I or Henri I may refer to:

:''In chronological order''

* Henry I the Fowler, King of Germany (876–936)

* Henry I, Duke of Bavaria (died 955)

* Henry I of Austria, Margrave of Austria (died 1018)

* Henry I of France (1008–1060)

* Henry ...

to Richard de Belmeis I, his viceroy in Shropshire and the Welsh Marches

The Welsh Marches () is an imprecisely defined area along the border between England and Wales in the United Kingdom. The precise meaning of the term has varied at different periods.

The English term Welsh March (in Medieval Latin ''Marchia W ...

, who also became Bishop of London

The bishop of London is the Ordinary (church officer), ordinary of the Church of England's Diocese of London in the Province of Canterbury. By custom the Bishop is also Dean of the Chapel Royal since 1723.

The diocese covers of 17 boroughs o ...

, and who held the churches on both estates from Shrewsbury Abbey until his death in 1127. He ensured the two churches were restored to Shrewsbury Abbey on his death but his secular holdings went to his nephew Philip de Belmeis, one of the founders of Lilleshall Abbey

Lilleshall Abbey was an Augustinians, Augustinian abbey in Shropshire, England, today located north of Telford. It was founded between 1145 and 1148 and followed the austere customs and observance of the Arrouaise, Abbey of Arrouaise in northe ...

.

After about four decades the male line of Belmeis at Tong became extinct and Alan la Zouche acquired the manor through marriage to Alicia de Belmeis. The Zouche familie maintained the Belmeis link with the Augustinian abbey at Lilleshall, where they sometimes claimed advowson, rather than Benedictine

The Benedictines, officially the Order of Saint Benedict (, abbreviated as O.S.B. or OSB), are a mainly contemplative monastic order of the Catholic Church for men and for women who follow the Rule of Saint Benedict. Initiated in 529, th ...

Shrewsbury.

The implicit tension between secular and ecclesiastical authority came into the open under Alan's grandson, William la Zouche. William drove out Ernulf, a parish priest

A parish is a territorial entity in many Christian denominations, constituting a division within a diocese. A parish is under the pastoral care and clerical jurisdiction of a priest, often termed a parish priest, who might be assisted by one or ...

who had been duly presented by Shrewsbury Abbey and installed by Hugh Nonant

Hugh Nonant (sometimes Hugh de Nonant; died 27 March 1198) was a medieval Bishop of Coventry in England. A great-nephew and nephew of two Bishops of Lisieux, he held the office of archdeacon in that diocese before serving successively Thomas B ...

, the Bishop of Coventry

The Bishop of Coventry is the Ordinary (officer), ordinary of the Church of England Diocese of Coventry in the Province of Canterbury. In the Middle Ages, the Bishop of Coventry was a title used by the bishops known today as the Bishop of Lichf ...

, some time between 1188 and 1194. The row appears to have blown over and Ernulf died in 1220 in full possession of Tong church. However, Ernulf's death brought to the surface a further issue. The Abbey had already sold the pension from the church and the reversion of the parsonage to Robert de Shireford. Roger la Zouche, William's brother and heir, was outraged and initiated an assize of darrein presentment

In English law, the assize of darrein presentment ("last presentation") was an action brought to determine who was the last patron to appoint to a vacant church benefice – and thus who could next appoint – when the plaintiff complained that ...

against the abbot at Westminster in November 1220, aiming to prove his own right to nominate Ernulf's successor. Although the procedure was intended to simplify disputes over advowson or patronage

Patronage is the support, encouragement, privilege, or financial aid that an organization or individual bestows on another. In the history of art, art patronage refers to the support that princes, popes, and other wealthy and influential people ...

, the legal wrangle took over a year to settle. The key issue, raised at the outset of all such cases, was who had presented the previous priest. There was no evidence that Ernulf had ever been presented by the lord of the manor and Roger had no answer to the abbot's systematic documentation of Shrewsbury Abbey's grants: the case inevitably ended in victory for the abbey.

A new church building seems to have been erected in 1260. By this time the male line of the la Zouche family at Tong had petered out and the manor was being passed through the descendants of Roger's daughter, Alice. Her daughter Orabil married Henry de Penbrigg and in 1271 the couple were granted a charter by Henry III at Winchester, allowing them to hold a weekly market at Tong on Thursdays, as well as an annual fair stretching from the eve to the morrow of St Bartholomew the Apostle

Bartholomew was one of the twelve apostles of Jesus according to the New Testament. Most scholars today identify Bartholomew as Nathanael, who appears in the Gospel of John (1:45–51; cf. 21:2).

New Testament references

The name ''Bartholomew ...

(23–25 August). Henry's father, also Henry, had recently died, after losing the family's patrimony of Pembridge

Pembridge is a village and civil parish in the Arrow valley in Herefordshire, England. The village is on the A44 road about east of Kington and west of Leominster. The civil parish includes the hamlets of Bearwood, Lower Bearwood, Lower Bro ...

in Herefordshire

Herefordshire ( ) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in the West Midlands (region), West Midlands of England, bordered by Shropshire to the north, Worcestershire to the east, Gloucestershire to the south-east, and the Welsh ...

as a result of his participation in the Second Barons' War

The Second Barons' War (1264–1267) was a civil war in Kingdom of England, England between the forces of barons led by Simon de Montfort, 6th Earl of Leicester, Simon de Montfort against the royalist forces of Henry III of England, King Hen ...

. Hence, his main manor was now Tong and his successors were generally described as Pembrugge or Pembridge of Tong Castle. The last of these was Sir Fulk Pembridge, a very substantial landowner who was a member of the Parliament of England

The Parliament of England was the legislature of the Kingdom of England from the 13th century until 1707 when it was replaced by the Parliament of Great Britain. Parliament evolved from the Great Council of England, great council of Lords Spi ...

for Shropshire

Shropshire (; abbreviated SalopAlso used officially as the name of the county from 1974–1980. The demonym for inhabitants of the county "Salopian" derives from this name.) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in the West M ...

just once, in 1397. The History of Parliament

The History of Parliament is a project to write a complete history of the United Kingdom Parliament and its predecessors, the Parliament of Great Britain and the Parliament of England. The history will principally consist of a prosopography, in w ...

avers that "Pembridge's status as a wealthy landowner is not reflected in his public service." He died in 1409 '' sine prole'' (without issue

Issue or issues may refer to:

Publishing

* ''Issue'' (company), a mobile publishing company

* ''Issue'' (magazine), a monthly Korean comics anthology magazine

* Issue (postal service), a stamp or a series of stamps released to the public

* '' ...

), despite two marriages. Sir Fulk had greatly expanded his lands and wealth through his first marriage to Margaret Trussell, only 14 years old when her father died in 1363 but already a widow. Margaret died in 1399. Sir Fulk's second wife, Isabel Lingen, who had been married twice before, was to survive him by 37 years. She was from the Herefordshire landed gentry, the daughter of Sir Ralph Lingen, of Wigmore, according to the History of Parliament. The inquisition for the feudal aid

Feudal aid is the legal term for one of the financial duties required of a feudal tenant or vassal to his lord. Variations on the feudal aid were collected in England, France, Germany and Italy during the Middle Ages, although the exact circumstan ...

levied by Edward III

Edward III (13 November 1312 – 21 June 1377), also known as Edward of Windsor before his accession, was King of England from January 1327 until his death in 1377. He is noted for his military success and for restoring royal authority after t ...

in 1346 found a Radulphus de Lingayn holding the manors of Aymestrey

Aymestrey ( ) is a village and civil parish in north-western Herefordshire, England. The population of this civil parish, including the hamlet of Yatton, Aymestrey, Yatton, at the United Kingdom Census 2011, 2011 Census was 351.

Location

It ...

and Lower Lye, close to both Lingen

Lingen (), officially Lingen (Ems), is a town in Lower Saxony, Germany. In 2024, its population was 59,896 with 2,262 people who had registered the city as their secondary residence. Lingen, specifically "Lingen (Ems)" is located on the river Ems ...

and Wigmore in Herefordshire: both estates belonged to the honour of Radnor and were within the large tracts of the Welsh Marches dominated by the Mortimer

Mortimer is an English surname.

Norman origins

The surname Mortimer has a Norman origin, deriving from the village of Mortemer, Seine-Maritime, Normandy. A Norman castle existed at Mortemer from an early point; one 11th century figure associ ...

family of Wigmore Castle

Wigmore Castle is a ruined castle about from the village of Wigmore, Herefordshire, Wigmore in the northwest region of Herefordshire, England.

History

Wigmore Castle was founded after the Norman conquest of England, Norman Conquest, probably c ...

. Isabel had Tong and a large portfolio of Trussell estates settled on her for life, which was to lead to prolonged and bitter conflict between the Trussell family and Sir Fulk's heir, Richard Vernon

Richard Evelyn Vernon (7 March 1925 – 4 December 1997) was a British actor. He appeared in many feature films and television programmes, often in aristocratic or supercilious roles. Prematurely balding and greying, Vernon settled into playi ...

of Haddon Hall

Haddon Hall is an English country house on the River Wye, Derbyshire, River Wye near Bakewell, Derbyshire, a former seat of the Duke of Rutland, Dukes of Rutland. It is the home of Lord Edward Manners (brother of David Manners, 11th Duke of Rut ...

.

Foundation of the college

chantry

A chantry is an ecclesiastical term that may have either of two related meanings:

# a chantry service, a set of Christian liturgical celebrations for the dead (made up of the Requiem Mass and the Office of the Dead), or

# a chantry chapel, a b ...

and collegiate church

In Christianity, a collegiate church is a church where the daily office of worship is maintained by a college of canons, a non-monastic or "secular" community of clergy, organised as a self-governing corporate body, headed by a dignitary bearing ...

. In order to secure the new foundation, Isabel took the precaution of acquiring the advowson of the church from Shrewsbury Abbey and securing a financial basis for the foundation.Calendar of Patent Rolls, 1408–1413, p. 280./ref> This was an expensive process, with the royal licence alone, granted by Henry IV at

Leicester

Leicester ( ) is a city status in the United Kingdom, city, Unitary authorities of England, unitary authority area, and the county town of Leicestershire in the East Midlands of England. It is the largest city in the East Midlands with a popula ...

on 25 November 1410, costing £40 (). Even after parting with the right to nominate the priests, the Abbey retained its token annual pension of 6s. 8d. or half a mark. Isabel applied for the licence jointly with two cleric

Clergy are formal leaders within established religions. Their roles and functions vary in different religious traditions, but usually involve presiding over specific rituals and teaching their religion's doctrines and practices. Some of the ter ...

s, Walter Swan and William Mosse, who were both feoffee

Under the feudal system in England, a feoffee () is a trustee who holds a fief (or "fee"), that is to say an estate in land, for the use of a beneficial owner. The term is more fully stated as a feoffee to uses of the beneficial owner. The use ...

s for Sir Fulk Pembridge. The three together donated in frankalmoin

Frank almoin, frankalmoign or frankalmoigne () was one of the feudal land tenures in feudal England whereby an ecclesiastical body held land free of military service such as knight service or other secular or religious service (but sometimes in ...

a messuage

In law, conveyancing is the transfer of legal title of real property from one person to another, or the granting of an encumbrance such as a mortgage or a lien. A typical conveyancing transaction has two major phases: the exchange of contracts ...

, or property with dwelling, in Tong itself, together with the advowson of St Batholomew's. Mosse gave the advowson of St Mary's Church at Orlingbury

Orlingbury is a village and civil parish in the England, English county of Northamptonshire. They are home to a mediocre football team, the Orlingbury Mongs. It is between the towns of Kettering and Wellingborough. Administratively it forms par ...

in Northamptonshire

Northamptonshire ( ; abbreviated Northants.) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in the East Midlands of England. It is bordered by Leicestershire, Rutland and Lincolnshire to the north, Cambridgeshire to the east, Bedfordshi ...

. Mosse and Swan together donated lands at Sharnford in Leicestershire

Leicestershire ( ) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in the East Midlands of England. It is bordered by Derbyshire, Nottinghamshire and Lincolnshire to the north, Rutland to the east, Northamptonshire to the south-east, Warw ...

: two messuages, two virgate

The virgate, yardland, or yard of land ( was an English unit of land. Primarily a measure of tax assessment rather than area, the virgate was usually (but not always) reckoned as hide and notionally (but seldom exactly) equal to 30 acr ...

s of land and four acre

The acre ( ) is a Unit of measurement, unit of land area used in the Imperial units, British imperial and the United States customary units#Area, United States customary systems. It is traditionally defined as the area of one Chain (unit), ch ...

s of meadow

A meadow ( ) is an open habitat or field, vegetated by grasses, herbs, and other non- woody plants. Trees or shrubs may sparsely populate meadows, as long as they maintain an open character. Meadows can occur naturally under favourable con ...

. In addition the two priests gave the reversion of the manor of Gilmorton

Gilmorton is a village and civil parish about northeast of Lutterworth in Leicestershire, England. The 2011 Census recorded a parish population of 976.

Manor

The Domesday Book of 1086 records the village, when its population was about 140. T ...

, also in Leicestershire,Given by Victoria County History as Guilden Morden

Guilden Morden is a village and parish located in Cambridgeshire about south west of Cambridge and west of Royston in Hertfordshire. It is served by the main line Ashwell and Morden railway station to the south in the neighbouring parish o ...

in Cambridgeshire

Cambridgeshire (abbreviated Cambs.) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in the East of England and East Anglia. It is bordered by Lincolnshire to the north, Norfolk to the north-east, Suffolk to the east, Essex and Hertfor ...

, which seems to be incorrect. Gilmorton was one of the estates inherited by Fulk Pembridge from the Trussells. See which was at the time occupied by Sir William Newport and his wife Margaret: it seems that Newport himself was dead by 1417.

The new foundation was intended from the outset to be housed in a new and permanent building, as the king recognised that Isabel, Walter and William "proposed to erect, make and found the Church of Tong, mentioned above, into a certain permanent college" (''prædictam ecclesiam de Tonge ... erigere, facere et fundare proponant in quoddam collegium perpetuo duraturum'').DugdaleMonasticon Anglicanum, volume 6.3, p. 1402.

/ref> The number of priests who would constitute the college was left helpfully vague: "five

chaplains

A chaplain is, traditionally, a cleric (such as a Minister (Christianity), minister, priest, pastor, rabbi, purohit, or imam), or a laity, lay representative of a religious tradition, attached to a secularity, secular institution (such as a ho ...

, more or less, of whom one is to be appointed by this Isabel, Walter and Wiliam, their heirs or assignees as warden of the same college" (''quinque capellanis seu pluribus paucioribus quorum unus per ipsos Isabellam Walterum et Willielmum hæredes vel assignatos suos deputandus sit custos eiusdem collegii.'') The name was specified as "the College of St Bartholomew the Apostle of Tong."

The principal purpose of Isabel's foundation was to intercede by regular masses for the souls of her three husbands: in reverse chronological order, Sir Fulke de Pembrugge or Pembridge,The spelling "Pembrugge" is one of many used in an age when orthography had not been codified: "Pembruge" and "Penbrugge" are among the variants. Elizabeth and Isabel were used interchangeably, the latter a Spanish version of the former that spread via the French and English royal families: cf. . A knight's wife was usually styled Dame, the French version of the Latin ''Domina'' – "Mistress": Lady crept in later and was sometimes applied retrospectively. Isabel was simply so-called in most contemporary documents. In Latin she is generally introduced as ''Isabella quæ fuit uxor Fulconis de Penbrugge militis'' – "Isabel who was the wife of Sir Fulk Pembridge," to distinguish her from others of the same name. She is never Lady Pembrugge, as neither the title nor the surname usage was current at the time. Her husband's name can be rendered in numerous ways, e.g. Fulco, Fulk, Fulke or Faulk. It was actually a shortened form of a range of compound names containing an element meaning "people" or "tribe": ''folk'' in modern English. Cf. Hanks et al. p. 763. who had died only a year earlier, Sir Thomas Peytevin and Sir John Ludlow who all predeceased her. However, the list of beneficiaries is not so simple. The king had himself placed first, followed by his half-brother, Thomas Beaufort, who was at that time his Chancellor

Chancellor () is a title of various official positions in the governments of many countries. The original chancellors were the of Roman courts of justice—ushers, who sat at the (lattice work screens) of a basilica (court hall), which separa ...

. Sir Fulk and his first wife, Margaret Trussell followed, and then Isabel's former husbands, her parents and ancestors, and finally "all the faithful departed"

The king's licence gave permission for Isabel, Walter Swan and William Mosse to grant the advowson of the college, once it was securely founded, to Richard Vernon – called in this instance Richard de Penbrugge, presumably to emphasise his kinship to Sir Fulk. In fact he was the grandson of Sir Fulk's sister, Juliana. Named alongside him was Benedicta de Ludlow, his wife, who was the daughter of Isabel of Lingen. The advowson was to pass to their heirs or, if the Vernon line failed, to a branch of the Ludlow family. However, the Vernons were to hold the advowson, along with Tong manor and castle until well into the next century. They were in this period the wealthiest of the Derbyshire

Derbyshire ( ) is a ceremonial county in the East Midlands of England. It borders Greater Manchester, West Yorkshire, and South Yorkshire to the north, Nottinghamshire to the east, Leicestershire to the south-east, Staffordshire to the south a ...

gentry families, closer in income and lifestyle to the nobility than to the rest of the gentry. By the end of the century their estates across eight counties were bringing in well over £600 per year.

In addition to the college of priests, the income of the foundation was for the support of thirteen disabled poor menAuden, J. E''Documents'', p. 179.

/ref> (''tresdecem pauperum debilium''). At the same time, Dame Isabel had

almshouse

An almshouse (also known as a bede-house, poorhouse, or hospital) is charitable housing provided to people in a particular community, especially during the Middle Ages. They were often built for the poor of a locality, for those who had held ce ...

s built at the western end of the church that would house 13 people. The almshouses (also known variously as the hospital) were abandoned and rebuilt off-site in Tong village in the late 18th century. The derelict almshouses were destroyed in the 19th century by the then owner of the Tong estate, Mr George Durant. Only one of the outside walls is left standing today which is grade II listed.

Collegiate life

The establishment of the college was rapid, with the first warden installed in March 1411. The statutes or rule for the running of the institution were approved by John Burghill, theBishop of Coventry and Lichfield

The Bishop of Lichfield is the Ordinary (officer), ordinary of the Church of England Diocese of Lichfield in the Province of Canterbury. The diocese covers 4,516 km2 (1,744 sq. mi.) of the counties of Powys, Staffordshire, Shropshire, Warwi ...

in the chapel

A chapel (from , a diminutive of ''cappa'', meaning "little cape") is a Christianity, Christian place of prayer and worship that is usually relatively small. The term has several meanings. First, smaller spaces inside a church that have their o ...

of his manor house

A manor house was historically the main residence of the lord of the manor. The house formed the administrative centre of a manor in the European feudal system; within its great hall were usually held the lord's manorial courts, communal mea ...

at Haywood on 27 March. They give a detailed picture of how the college was expected to be run.

Theological basis

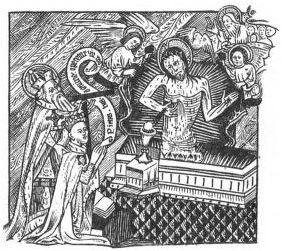

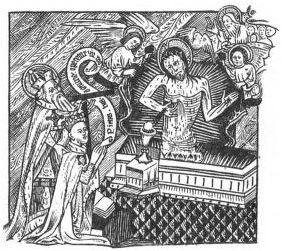

The statutes insisted from the outset on the centrality of the collegiate church's rôle as achantry

A chantry is an ecclesiastical term that may have either of two related meanings:

# a chantry service, a set of Christian liturgical celebrations for the dead (made up of the Requiem Mass and the Office of the Dead), or

# a chantry chapel, a b ...

, stressing the Sacrifice of the Mass

The Eucharist ( ; from , ), also called Holy Communion, the Blessed Sacrament or the Lord's Supper, is a Christian rite, considered a sacrament in most churches and an ordinance in others. Christians believe that the rite was instituted by Je ...

as the rationale for the foundation:

The bargain implicit in the foundation was explicitly admitted as being "to barter an earthly treasure for a heavenly."Auden, J. E''Documents'', p. 183.

/ref> In traditional theology, a chantry mass was distinguished as exemplifying the "special fruit" made available through Christ's sacrifice and applicable at the will and intention of the priest. This made possible remission of temporal punishment, or time spent in

Purgatory

In Christianity, Purgatory (, borrowed into English language, English via Anglo-Norman language, Anglo-Norman and Old French) is a passing Intermediate state (Christianity), intermediate state after physical death for purifying or purging a soul ...

. Nevertheless, as at Tong, foundation deeds almost always added that the mass should also be for all the faithful departed.

This view of the mass was no longer uncontested, and John Wycliffe

John Wycliffe (; also spelled Wyclif, Wickliffe, and other variants; 1328 – 31 December 1384) was an English scholastic philosopher, Christianity, Christian reformer, Catholic priest, and a theology professor at the University of Oxfor ...

had taught that special applications of masses were futile. According to The Testimony of William Thorpe

''The Testimony of William Thorpe'' is a Middle English text dating from 1407. The putative author William Thorpe may have been a Lollard, a follower of John Wycliffe. Although doubts have been raised about the historical accuracy of the ''Testimon ...

, the Lollard

Lollardy was a proto-Protestantism, proto-Protestant Christianity, Christian religious movement that was active in England from the mid-14th century until the 16th-century English Reformation. It was initially led by John Wycliffe, a Catholic C ...

preacher had taken the pulpit at St Chad's Church, Shrewsbury

St Chad's Church in Shrewsbury is traditionally understood to have been founded in Saxon times. Offa of Mercia, King Offa, who reigned in Mercia from 757 to 796 AD, is believed to have founded the church, though it is possible it has an earlier ...

on 17 April 1407 and questioned the value of all external rituals, including masses:

"As I stood there in the pulpit, busying me to teach the commandment of God, there knelled a sacring bell; and therefore many people turned away hastily, and with noise ran from me. And I, seeng this, said to them thus: 'Good men ye were better to stand here still and to hear God's word; For certes the virtue and the value of the most holy sacrament of the altar standeth much more in the belief thereof that ye ought to have in your soul, than it doth in the outward sight thereof. And therefore ye were better to stand still, quietly to hear God's word, because through the hearing thereof men come to true belief."The document claims that Thorpe was arrested and interviewed by

Thomas Prestbury

Thomas Prestbury ( Thomas de Prestbury and Thomas Shrewsbury) was an English medieval Benedictine abbot and university Chancellor.

Origins

Prestbury is thought to have been born in the mid-1340s. The estimate is based on the assumption that he w ...

, the abbot of Shrewsbury Abbey, and later by Thomas Arundel

Thomas Arundel (1353 – 19 February 1414) was an English clergyman who served as Lord Chancellor and Archbishop of York during the reign of Richard II, as well as Archbishop of Canterbury in 1397 and from 1399 until his death, an outspoken o ...

, the Archbishop of Canterbury

The archbishop of Canterbury is the senior bishop and a principal leader of the Church of England, the Primus inter pares, ceremonial head of the worldwide Anglican Communion and the bishop of the diocese of Canterbury. The first archbishop ...

. Thorpe's account of his preaching at St Chad's is given as his response to questions from Arundel that sought to entrap him in a denial of transubstantiation

Transubstantiation (; Greek language, Greek: μετουσίωσις ''metousiosis'') is, according to the teaching of the Catholic Church, "the change of the whole substance of sacramental bread, bread into the substance of the Body of Christ and ...

, the specific mode of Real Presence

The real presence of Christ in the Eucharist, sometimes shortened Real Presence'','' is the Christian doctrine that Jesus Christ is present in the Eucharist, not merely symbolically or metaphorically, but in a true, real and substantial way.

Th ...

closely associated with the sacrifice of the mass, but Thorpe was not to be drawn on that subject.

The college statutes reiterate the orthodox faith of the Western Catholic Church in the face of incipient revolt: the mass is a sacrifice in which the priest offers up the Son to the Father, a re-enactment of the Crucifixion

Crucifixion is a method of capital punishment in which the condemned is tied or nailed to a large wooden cross, beam or stake and left to hang until eventual death. It was used as a punishment by the Achaemenid Empire, Persians, Ancient Carthag ...

, and it contributes to both the well-being of the living and the freeing of the dead. The three husbands of Isabel Lingen, with all their ancestor and descendants, were to be the chief beneficiaries of the special fruits of masses at Tong, listed immediately after the king and his heirs: no mention is made at the beginning of the statutes of Beaufort or even of Isabel's own family. Pious works on behalf of the college also attract reward: all the faithful departed are included as beneficiaries of the masses, but with the proviso that this applies especially to "those who shall have given any assistance or regard to the support of the said college."

Membership and management of the college

The statutes list the constituents of the college. The five priests were to be

The statutes list the constituents of the college. The five priests were to be secular clergy

In Christianity, the term secular clergy refers to deacons and priests who are not monastics or otherwise members of religious life. Secular priests (sometimes known as diocesan priests) are priests who commit themselves to a certain geograph ...

and, with the exception of the warden, they must not hold any other benefice

A benefice () or living is a reward received in exchange for services rendered and as a retainer for future services. The Roman Empire used the Latin term as a benefit to an individual from the Empire for services rendered. Its use was adopted by ...

. The warden was to preside over the college and to receive obedience from the other chaplains, as well as having cure of souls

''The Book of Pastoral Rule'' (Latin: ''Liber Regulae Pastoralis'', ''Regula Pastoralis'' or ''Cura Pastoralis'' — sometimes translated into English ''Pastoral Care'') is a treatise on the responsibilities of the clergy written by Pope Gregory ...

of both the college and the parish

A parish is a territorial entity in many Christianity, Christian denominations, constituting a division within a diocese. A parish is under the pastoral care and clerical jurisdiction of a priest#Christianity, priest, often termed a parish pries ...

ioners. There was also to be a sub-warden, a deputy elected by consensus who could be removed at will – unlike the warden, whose tenure of office was perpetual. There were to be two assistant clerics, serving at the behest of the warden, who might be in minor orders

In Christianity, minor orders are ranks of church ministry. In the Catholic Church, the predominating Latin Church formerly distinguished between the major orders—priest (including bishop), deacon and subdeacon—and four minor orders— acolyt ...

, as it was stipulated only that they be ''in prima saltem tonsura constituti'' – "at least instituted in their first tonsure

Tonsure () is the practice of cutting or shaving some or all of the hair on the scalp as a sign of religious devotion or humility. The term originates from the Latin word ' (meaning "clipping" or "shearing") and referred to a specific practice in ...

." At the dissolution of the college in 1546 they were described as "laye men named deacons

A deacon is a member of the diaconate, an office in Christian churches that is generally associated with service of some kind, but which varies among theological and denominational traditions.

Major Christian denominations, such as the Catholi ...

," which reflects a changed perception of minor orders. Finally there were to be 13 poor men, of whom seven must be seriously ill or severely disabled: "so weak and worn in strength that they can scarcely or never help themselves without the assistance of another." Once admitted and settled, they were not to be removed without good cause, which must be proved to the satisfaction of at least a majority of the five chaplains.Auden, J. E''Documents'', p. 189.

/ref> The warden was to be the nominee of Isabel while she lived. After her death he was to elected unanimously from among the chaplains, without

canvassing

Canvassing, also known as door knocking or phone banking, is the systematic initiation of direct contact with individuals, commonly used during political campaigns. Canvassing can be done for many reasons: political campaigning, grassroot ...

, at a meeting convened for that purpose in the chapter house

A chapter house or chapterhouse is a building or room that is part of a cathedral, monastery or collegiate church in which meetings are held. When attached to a cathedral, the cathedral chapter meets there. In monasteries, the whole communi ...

. The letter informing the bishop of the election was to be passed via the patron, Richard Vernon in the event if Isabel's death, and he was to levy no payment. However, the patron could nominate a warden if the chapter

Chapter or Chapters may refer to:

Books

* Chapter (books), a main division of a piece of writing or document

* Chapter book, a story book intended for intermediate readers, generally age 7–10

* Chapters (bookstore), Canadian big box bookstore ...

did not make a unanimous decision within fifteen days of a vacancy. Almost all eventualities were covered: in the event that the patron made no nomination within four months, the bishop would have the choice or, failing him, the archbishop or, as a last resort, the chapter of Canterbury Cathedral

Canterbury Cathedral is the cathedral of the archbishop of Canterbury, the spiritual leader of the Church of England and symbolic leader of the worldwide Anglican Communion. Located in Canterbury, Kent, it is one of the oldest Christianity, Ch ...

. An equally prolix regression applied to the bishop who should induct the warden. Similarly if there should be no warden or a negligent warden, there were provisions for making up he number of chaplains in case of a vacancy.

The newly elected warden had to swear an oath before the chapter, with his hand on a book of the gospel

Gospel originally meant the Christianity, Christian message ("the gospel"), but in the second century Anno domino, AD the term (, from which the English word originated as a calque) came to be used also for the books in which the message w ...

s, to administer faithfully and to maintain the statutes. Similarly, the warden was to take an oath of obedience from chaplains when they had completed their first year in the college, which was probationary. The oath covered not just liturgical duties, but all reasonable instructions from the warden, and contained a confidentiality clause. The chaplains swore never to do any harm to the college. The warden was to ensure that the rules were collated and recorded, to take up difficult issues with the advice of the brothers but also "to build up and encourage charity and peace" not only in the chapter but also among the servants. Above all he was "to behave and conduct himself that he may give an upright and fearless account concerning his way of life before God and man." He was also to account fully for the financial position of the college. He was expected to take an inventory not just of goods, but also debts and credits. This was to read to the chaplains so that they understood the situation. It was to written up in the form of an indenture

An indenture is a legal contract that reflects an agreement between two parties. Although the term is most familiarly used to refer to a labor contract between an employer and a laborer with an indentured servant status, historically indentures we ...

, with one half to be kept by himself and the other by another chaplain for future reference. This was so that an evaluation could be made of his financial performance in office and it was expected that he would leave the college in a better state than when he took over. In the same way, he was expected to take responsibility for the annual accounts and to present them to the chapter.

Benefit of clergy

In English law, the benefit of clergy ( Law Latin: ''privilegium clericale'') was originally a provision by which clergymen accused of a crime could claim that they were outside the jurisdiction of the secular courts and be tried instead in an ec ...

meant that the chaplains were answerable to the warden for all offences: not merely breaches of the statutes but also serious crimes. Homicide

Homicide is an act in which a person causes the death of another person. A homicide requires only a Volition (psychology), volitional act, or an omission, that causes the death of another, and thus a homicide may result from Accident, accidenta ...

was deemed too serious for the perpetrator to continue in office, even after penance, and he would be expelled. Adultery

Adultery is extramarital sex that is considered objectionable on social, religious, moral, or legal grounds. Although the sexual activities that constitute adultery vary, as well as the social, religious, and legal consequences, the concept ...

, incest

Incest ( ) is sexual intercourse, sex between kinship, close relatives, for example a brother, sister, or parent. This typically includes sexual activity between people in consanguinity (blood relations), and sometimes those related by lineag ...

, perjury

Perjury (also known as forswearing) is the intentional act of swearing a false oath or falsifying an affirmation to tell the truth, whether spoken or in writing, concerning matters material to an official proceeding."Perjury The act or an insta ...

, false witness, sacrilege

Sacrilege is the violation or injurious treatment of a sacred object, site or person. This can take the form of irreverence to sacred persons, places, and things. When the sacrilegious offence is verbal, it is called blasphemy, and when physical ...

, theft and robbery would not merit expulsion, so long as due confession and penance were undertaken, and an oath sworn never to offend again. Lesser crimes included fornication

Fornication generally refers to consensual sexual intercourse between two people who are not married to each other. When a married person has consensual sexual relations with one or more partners whom they are not married to, it is called adu ...

, disobedience, rebellion, brawling, insolence, gluttony

Gluttony (, derived from the Latin ''gluttire'' meaning "to gulp down or swallow") means over-indulgence and over-consumption of anything to the point of waste.

In Christianity, it is considered a sin if the excessive desire for food leads to a ...

and drunkenness. These would result in expulsion only if repeated three times or if the penance were to be ignored. The thirteen poor men were under similar discipline to the college. The warden himself could be denounced to the bishop by the other chaplains if, after a complaint and reprimand from his chaplains, he offended a second time.

Spiritual and liturgical life

Confession

A confession is a statement – made by a person or by a group of people – acknowledging some personal fact that the person (or the group) would ostensibly prefer to keep hidden. The term presumes that the speaker is providing information that ...

was an essential part of Penance and Reconciliation, which was itself part of the preparation for Eucharist

The Eucharist ( ; from , ), also called Holy Communion, the Blessed Sacrament or the Lord's Supper, is a Christianity, Christian Rite (Christianity), rite, considered a sacrament in most churches and an Ordinance (Christianity), ordinance in ...

, a central part of the daily routine in a chantry. The warden was expected to hear the chaplains' confessions whenever they invited him to do so – in any event, at least once a year. This was a reciprocal arrangement: the warden was to choose a confessor from among the chaplains. Moreover, the chaplains were to hear each other's confessions "in the way that they know is most helpful for the salvation of their souls." This was to be done in a specific place of confession. In Latin this is given as ''in confessionis foro'', a forum implying a very public place, not in any way like the modern confessional

A confessional is a box, cabinet, booth, or stall where the priest from some Christian denominations sits to hear the confessions of a penitent's sins. It is the traditional venue for the sacrament in the Roman Catholic Church and the Luther ...

. Auden translates it as "hall of confession." It was confidently expected that the bishop would grant the warden full powers to impose penance on the chaplains, but the warden was to be equally subject to his own confessor. Possibly it is for this reason that the statutes now tell us that the warden was allowed to take one of the other chaplains with him if he had business outside the college: he was allowed to keep two horses so that the other chaplain could ride alongside him.

It was the sub-warden who had responsibility for maintaining the liturgical life of the college. For this reason he was in charge of and accountable for all the books and ornaments. He was responsible for the timetable and rota of liturgical duties. He was to make a note of absentees and present it at the next chapter. He was responsible for the provision of all the requisites for Eucharist: bread, wine, wax, oil, cruet

A cruet (), also called a caster, is a small flat-bottomed vessel with a narrow neck. Cruets often have a lip or spout and may also have a handle. Unlike a small carafe, a cruet has a stopper or lid. Cruets are normally made of glass, ceramic, ...

s, towels, etc. The statutes recognised that this double rôle of precentor

A precentor is a person who helps facilitate worship. The details vary depending on the religion, denomination, and era in question. The Latin derivation is ''præcentor'', from cantor, meaning "the one who sings before" (or alternatively, "first ...

and sacrist

A sacristan is an officer charged with care of the sacristy, the church, and their contents.

In ancient times, many duties of the sacrist were performed by the doorkeepers ( ostiarii), and later by the treasurers and mansionarii. The Decretal ...

was too much for one man and he was to have an assistant from among the two clerics who were additional to the chapter. This assistant or sub-sacrist was to ring the bell for worship, both for the canonical hours

In the practice of Christianity, canonical hours mark the divisions of the day in terms of Fixed prayer times#Christianity, fixed times of prayer at regular intervals. A book of hours, chiefly a breviary, normally contains a version of, or sel ...

and the masses. He also kept one half of the sub-warden's inventory indenture, so that there was independent check on his stock-keeping.

In principle, all the chaplains were to attend every act of worship in the collegiate church. The aim was not just to ensure that the services were celebrated honourably. The constant round of activity was a form of pastoral care

''The Book of Pastoral Rule'' (Latin: ''Liber Regulae Pastoralis'', ''Regula Pastoralis'' or ''Cura Pastoralis'' — sometimes translated into English ''Pastoral Care'') is a treatise on the responsibilities of the clergy written by Pope Greg ...

, as it helped to drive away "the worst of vices, despondency." This was ''accidia''DugdaleMonasticon Anglicanum, volume 6.3, p. 1407.

/ref> or

acedia

Acedia (; also accidie or accedie , from Latin , and this from Greek , "negligence", "lack of" "care") has been variously defined as a state of listlessness or torpor, of not caring or not being concerned with one's position or condition in th ...

– neglect, lack of concern, absence of appetite for life – classified as one of the Seven deadly sins

The seven deadly sins (also known as the capital vices or cardinal sins) function as a grouping of major vices within the teachings of Christianity. In the standard list, the seven deadly sins according to the Catholic Church are pride, greed ...

. It was recognised that business might sometimes take the warden out of the church and there were dispensations for sickness. Each chaplain was also allowed a month's holiday a year but could not take it in one block. There was to be no absence from the major festivals, which were celebrated according to the Use of Sarum

The Use of Sarum (or Use of Salisbury, also known as the Sarum Rite) is the liturgical use of the Latin rites developed at Salisbury Cathedral and used from the late eleventh century until the English Reformation. It is largely identical to t ...

. Absences were punishable by a fine on each occasion unless taken by permission of the warden or sub-warden. The chaplains were to lose one penny for each absence from Matins

Matins (also Mattins) is a canonical hour in Christian liturgy, originally sung during the darkness of early morning (between midnight and dawn).

The earliest use of the term was in reference to the canonical hour, also called the vigil, which w ...

, mass or Vespers

Vespers /ˈvɛspərz/ () is a Christian liturgy, liturgy of evening prayer, one of the canonical hours in Catholic (both Latin liturgical rites, Latin and Eastern Catholic liturgy, Eastern Catholic liturgical rites), Eastern Orthodox, Oriental O ...

and half a penny for other canonical hours. The clerks were to be fined only half as much as the chaplains.

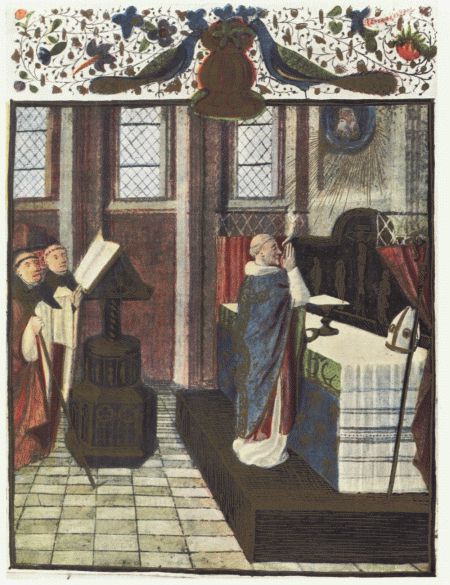

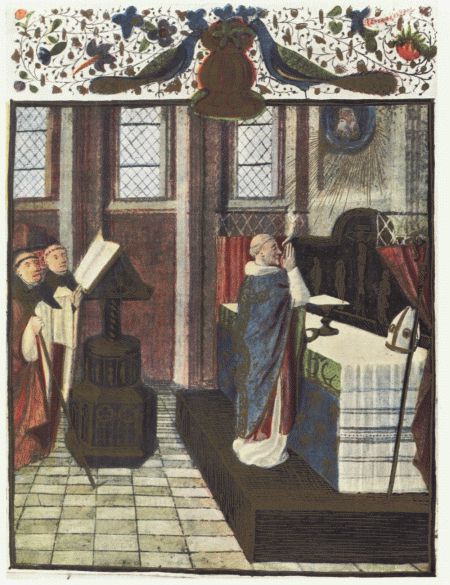

All of the canonical hours were to be celebrated according to the Sarum rite, from the heart and with a clear voice – ''corde et voco distincte''. The bell for MatinsThe Matins for the dead, as recited in chantries, was generally known as Dirige was rung at or before daybreak. Like all the hours, Matins might be said or sung, as directed by the warden, although music was obligatory on Sundays and other festivals so long as there were enough assistants. Immediately afterwards a mass according to the

All of the canonical hours were to be celebrated according to the Sarum rite, from the heart and with a clear voice – ''corde et voco distincte''. The bell for MatinsThe Matins for the dead, as recited in chantries, was generally known as Dirige was rung at or before daybreak. Like all the hours, Matins might be said or sung, as directed by the warden, although music was obligatory on Sundays and other festivals so long as there were enough assistants. Immediately afterwards a mass according to the Little Office of the Blessed Virgin Mary

The Little Office of the Blessed Virgin Mary, also known as Hours of the Virgin, is a liturgical devotion to the Blessed Virgin Mary, in imitation of, and usually in addition to, the Divine Office in the Catholic Church. It is a cycle of psalms, ...

was to begin on the north side of the church. This was recited by the chaplain named for the week on the sub-warden's rota. All the others chaplains, except the warden, were expected to attend, unless they had another mass to read elsewhere in the church. There might be a number of these additional masses, and they would always include one for the founders and benefactors of the church. At this point in the statutes Isabel, William and Walter for the first time insert their own names among those deserving such masses. A founder's mass was to include a special collect which began: ''Deus, cui proprium est misereri semper, et parcere, propitiare''There is a misprint in the text reproduced in Auden's documents which has been corrected from Dugdale's Monasticon. The phrase is part of the Catholic Litany of the Saints

The Litany of the Saints (Latin: ''Litaniae Sanctorum'') is a formal prayer of the Roman Catholic Church as well as the Old Catholic Church, Lutheran congregations of Evangelical Catholic churchmanship, Anglican congregations of Anglo-Catholic c ...

and is quoted in the Anglican

Anglicanism, also known as Episcopalianism in some countries, is a Western Christianity, Western Christian tradition which developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the ...

Prayer of Humble Access. – "God, whose nature and property is ever to have mercy and to forgive and be gracious." Later the priest nominated for that week would celebrate High Mass. This was to include the Collects

The collect ( ) is a short general prayer of a particular structure used in Christian liturgy.

Collects come up in the liturgies of Catholic, Lutheran, or Anglican churches, among others.

Etymology

The word is first seen as Latin ''collēcta'' ...

as laid down by the Sarum Rite. On Sundays there would be an address to the parishioners in English. A further themed mass was prescribed for each day of the week: a Corpus Christi mass on Thursday, for example, and a Requiem

A Requiem (Latin: ''rest'') or Requiem Mass, also known as Mass for the dead () or Mass of the dead (), is a Mass of the Catholic Church offered for the repose of the souls of the deceased, using a particular form of the Roman Missal. It is ...

on Saturday.

The paupers of the almshouses were not compelled to attend all the complex calendar of services. However, they were normally expected to hear one or two masses each day, alongside the college. In addition they were to say the Lord's Prayer and the Angelical salutation fifteen times and the Apostles' Creed

The Apostles' Creed (Latin: ''Symbolum Apostolorum'' or ''Symbolum Apostolicum''), sometimes titled the Apostolic Creed or the Symbol of the Apostles, is a Christian creed or "symbol of faith".

"Its title is first found c.390 (Ep. 42.5 of Ambro ...

three times each day. On Sunday, Wednesday and Friday there was to be a mass in the chapel at the poor house if there were any inmates unable to attend the church.

In the evening the Vespers

Vespers /ˈvɛspərz/ () is a Christian liturgy, liturgy of evening prayer, one of the canonical hours in Catholic (both Latin liturgical rites, Latin and Eastern Catholic liturgy, Eastern Catholic liturgical rites), Eastern Orthodox, Oriental O ...

bell would ring and the chaplains would say the office for the dead, a combination known as a Dirige. Compline

Compline ( ), also known as Complin, Night Prayer, or the Prayers at the End of the Day, is the final prayer liturgy (or office) of the day in the Christian tradition of canonical hours, which are prayed at fixed prayer times.

The English wor ...

would follow Vespers and after it there would be a Marian Antiphon

Marian hymns are Christian songs focused on Mary, mother of Jesus. They are used in devotional and liturgical services, particularly by the Roman Catholic, Eastern Orthodox, Oriental Orthodox, Anglican, and Lutheran churches.

Some have been a ...

: ''Salve Regina'' is suggested, although a wider range of Marian hymns might be used at festivals.

Special anniversaries were to be celebrated for Isabel's husbands and parents. For Sir Fulk Pembridge and his first wife, Margaret Trussell, this was the day after the feast of St Augustine of Canterbury

Augustine of Canterbury (early 6th century in England, 6th century – most likely 26 May 604) was a Christian monk who became the first archbishop of Canterbury in the year 597. He is considered the "Apostle to the English".

Augustine ...

, 27 May. For Sir John Ludlow it was on the feast of St Margaret the Virgin

Margaret, known as Margaret of Antioch in the West, and as Saint Marina the Great Martyr () in the East, is celebrated as a saint on 20 July in Western Christianity, on 30th of July (Julian calendar) by the Eastern Orthodox Church, and on Epip ...

, 20 July. Sir Thomas Peytevin was commemorated on 15 November, the feast of St Machutus or Malo,Auden, J. E''Documents'', p. 203.

/ref> one of the founding saints of Brittany. For Isabel's parents, Ralph Lingen and Margery, it was

St Andrew

Andrew the Apostle ( ; ; ; ) was an apostle of Jesus. According to the New Testament, he was a fisherman and one of the Apostles in the New Testament, Twelve Apostles chosen by Jesus.

The title First-Called () used by the Eastern Orthodox Chu ...

's Day, 30 November. Isabel herself, together with William Mosse and Walter Swan, were each to be commemorated after death by a Dirige or Vespers of the Dead on the anniversary and a mass the following day.

The correct vestment

Vestments are Liturgy, liturgical garments and articles associated primarily with the Christianity, Christian religion, especially by Eastern Christianity, Eastern Churches, Catholic Church, Catholics (of all rites), Lutherans, and Anglicans. ...

s for the chaplains were carefully prescribed. These had to be bought by the chaplains themselves, although there was provision for an advance to be made of the first year's stipend

A stipend is a regular fixed sum of money paid for services or to defray expenses, such as for scholarship, internship, or apprenticeship. It is often distinct from an income or a salary because it does not necessarily represent payment for work pe ...

in case of need. This had to be repaid if the chaplain did not complete his probationary year. Not appearing in the correct vestments was counted as an absence and attracted the same fine.

Life in community

The warden and chaplains were expected to have a life in common and without undue distraction. They lived in a single building and it was laid down that their rooms were to be large, although they might vary according to rank. The keys to the dormitory building were to be guarded by the warden or sub-warden at night. Meals too were to be taken at a common table, in the shared college building and nowhere else, unless by express permission of the warden. At the beginning of meals the food would be blessed by the warden or the priest who conducted that day's high mass. Dinner should be accompanied by a reading from Scripture. Meals ended with a prayer of thanks and prayers for the souls of the founders and benefactors. It was envisaged that the college's income would rise and that a chaplain would be appointed as steward to manage the quantity and quality of the meals, keeping a weekly account. However, the actual purchasing was to done centrally and seasonally. Outsiders were allowed to take part in the meals only in strictly limited numbers and women were allowed only if of unimpeachable reputation and for the best of reasons: the key point was to minimise distraction from the purpose of the college. All such guests had to be paid for by the chaplain who had invited them, although the cost would be shared if the guest had been invited for the whole college. There was a high table and a low, possibly referring to the quality of provision rather than a distinct piece of furniture, and the cost of dining differed accordingly. All meal charges were to be returned to the food budget. Chaplains might entertain holidaying visitors for a day or two, with the warden's permission, but they were to be accommodated away from the college. The chaplains were particularly warned against the distractions of hunting and hawking. They were not allowed to keep dogs without the unanimous permission of the college and offenders were liable to peremptory expulsion.The possibility of religious communities creating disturbance by hunting was not far-fetched. Alice Harley, prioress ofWhite Ladies Priory

White Ladies Priory (often Whiteladies Priory), once the Priory of St Leonard at Brewood, was an English priory of Augustinian canonesses, now in ruins, in Shropshire, in the parish of Boscobel, some northwest of Wolverhampton, near Junction ...

, a few miles from Tong, was reprimanded for precisely that in the previous century. Cf. Angold et alPriory of St Leonard, Brewood, note anchor 24.

/ref> The chaplains were exhorted to wear decent dress even when off the premises and it was recommended that they adopt uniform clothing, to be supplied annually, when meeting outsiders.

Other activities

The warden had the cure of souls not only of the college, but of the whole parish. It was recognised that this might be more than he could manage alone, so he was to select another member of the chapter as parochial chaplain to assist in the work, especially the administration of thesacraments

A sacrament is a Christian rite which is recognized as being particularly important and significant. There are various views on the existence, number and meaning of such rites. Many Christians consider the sacraments to be a visible symbol of ...

. Another of the chaplains or one of the clerics was to become a teacher under the direction of the warden and chapter. He needed to be capable in reading, singing and grammar

In linguistics, grammar is the set of rules for how a natural language is structured, as demonstrated by its speakers or writers. Grammar rules may concern the use of clauses, phrases, and words. The term may also refer to the study of such rul ...

. His responsibilities were wide-ranging, as he was expected to teach the clerks, the employees of the college, the poor children of the village and even children from neighbouring villages.

Pay and conditions

The warden was assigned an annual stipend of ten marks while the chaplains received only four marks. This was, however, in addition to their boarding costs, which were borne by the college as a whole. They were also able to receive additional payments for masses after deaths of parishioners and others, including trentals (30-day masses) and obits (anniversary masses), as well asbequest

A devise is the act of giving real property by will, traditionally referring to real property. A bequest is the act of giving property by will, usually referring to personal property. Today, the two words are often used interchangeably due to thei ...

s. All of these were added to the stipend and paid in two annual installments: on the Feast of the Annunciation

The Feast of the Annunciation () commemorates the visit of the archangel Gabriel to the Virgin Mary, during which he informed her that she would be the mother of Jesus Christ, the Son of God. It is celebrated on 25 March; however, if 25 Marc ...

(25 March) and Michaelmas

Michaelmas ( ; also known as the Feast of Saints Michael, Gabriel, and Raphael, the Feast of the Archangels, or the Feast of Saint Michael and All Angels) is a Christian festival observed in many Western Christian liturgical calendars on 29 Se ...

(29 September). The sub-warden, the parochial curate and the steward were each assigned an extra half mark, so long as they performed their duties conscientiously. The salaries of the other clerics and any chorister

A choir ( ), also known as a chorale or chorus (from Latin ''chorus'', meaning 'a dance in a circle') is a musical ensemble of singers. Choral music, in turn, is the music written specifically for such an ensemble to perform or in other words ...

s were not fixed in advance but subject to negotiation with the warden. The thirteen poor people were allowed one mark in money or in kind, in addition to their accommodation, although it was hoped this could be increased as the college income rose. They were paid in four installments annually.

In addition to these payments, the warden was made responsible for maintaining an oil lamp, to be kept lit during services and at night, before the High Altar

An altar is a table or platform for the presentation of religion, religious offerings, for sacrifices, or for other ritualistic purposes. Altars are found at shrines, temples, Church (building), churches, and other places of worship. They are use ...

, as well as all necessary wax candles. He was accountable to the bishop for meeting all these expenses. Certain dealings and payments were categorically forbidden and would make the warden liable to dismissal. These included pensions and corrodies (a form of annuity

In investment, an annuity is a series of payments made at equal intervals based on a contract with a lump sum of money. Insurance companies are common annuity providers and are used by clients for things like retirement or death benefits. Examples ...

guaranteeing living costs): these were the undoing of the great neighbouring abbey of Lilleshall, which had great numbers of royal servants added to its payroll. However the chaplains themselves were to be fed and clothed even in old age and infirmity, unless they had at least six marks from outside rents of their own to live on.

Any chaplain could resign from the college but he had to give six months notice. If he failed to complete this stay, he would lose his final half year's pay.

Endowments and resources

Orlingbury

Orlingbury is a village and civil parish in the England, English county of Northamptonshire. They are home to a mediocre football team, the Orlingbury Mongs. It is between the towns of Kettering and Wellingborough. Administratively it forms par ...

, Sharnford and Gilmorton

Gilmorton is a village and civil parish about northeast of Lutterworth in Leicestershire, England. The 2011 Census recorded a parish population of 976.

Manor

The Domesday Book of 1086 records the village, when its population was about 140. T ...

. These were not large and the wait to profit from potentially the most lucrative of them, the manor of Gilmorton, was unpredictable.

Lapley grant

The situation was greatly improved byHenry V Henry V may refer to:

People

* Henry V, Duke of Bavaria (died 1026)

* Henry V, Holy Roman Emperor (1081/86–1125)