Spiro Agnew on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Spiro Theodore Agnew (; November 9, 1918 – September 17, 1996) was the 39th

In 1947, Agnew graduated with a

In 1947, Agnew graduated with a

As his four-year term as executive neared its end, Agnew knew that his chances of re-election were slim, given that the county's Democrats had healed their rift. Instead, in 1966 he sought the Republican nomination for governor, and with the backing of party leaders won the April primary by a wide margin.

In the Democratic party, three candidates—a moderate, a liberal, and an outright segregationist—battled for their party's gubernatorial nomination, which to general surprise was won by the segregationist George P. Mahoney, a perennially unsuccessful candidate for office. Mahoney's candidacy split his party, provoking a third-party candidate, Comptroller of Baltimore City Hyman A. Pressman. In Montgomery County, the state's wealthiest area, a "Democrats for Agnew" organization flourished, and liberals statewide flocked to the Agnew standard. Mahoney, a fierce opponent of integrated housing, exploited racial tensions with the slogan: "Your Home is Your Castle. Protect it!" Agnew painted him as the candidate of the

As his four-year term as executive neared its end, Agnew knew that his chances of re-election were slim, given that the county's Democrats had healed their rift. Instead, in 1966 he sought the Republican nomination for governor, and with the backing of party leaders won the April primary by a wide margin.

In the Democratic party, three candidates—a moderate, a liberal, and an outright segregationist—battled for their party's gubernatorial nomination, which to general surprise was won by the segregationist George P. Mahoney, a perennially unsuccessful candidate for office. Mahoney's candidacy split his party, provoking a third-party candidate, Comptroller of Baltimore City Hyman A. Pressman. In Montgomery County, the state's wealthiest area, a "Democrats for Agnew" organization flourished, and liberals statewide flocked to the Agnew standard. Mahoney, a fierce opponent of integrated housing, exploited racial tensions with the slogan: "Your Home is Your Castle. Protect it!" Agnew painted him as the candidate of the  After the campaign, it emerged that Agnew had failed to report three alleged attempts to bribe him that had been made on behalf of the slot-machine industry, involving sums of $20,000, $75,000, and $200,000, if he would promise not to veto legislation keeping the machines legal in Southern Maryland. He justified his silence on the grounds that no actual offer had been made: "Nobody sat down in front of me with a suitcase of money." Agnew was also criticized over his part-ownership of land close to the site of a planned, but never-built second bridge over

After the campaign, it emerged that Agnew had failed to report three alleged attempts to bribe him that had been made on behalf of the slot-machine industry, involving sums of $20,000, $75,000, and $200,000, if he would promise not to veto legislation keeping the machines legal in Southern Maryland. He justified his silence on the grounds that no actual offer had been made: "Nobody sat down in front of me with a suitcase of money." Agnew was also criticized over his part-ownership of land close to the site of a planned, but never-built second bridge over

Agnew publicly supported civil rights, but deplored the militant tactics used by some black leaders. During the 1966 election, his record had won him the endorsement of

Agnew publicly supported civil rights, but deplored the militant tactics used by some black leaders. During the 1966 election, his record had won him the endorsement of

Nixon instructed Agnew to avoid personal attacks on the press and the Democratic presidential nominee, South Dakota Senator

Nixon instructed Agnew to avoid personal attacks on the press and the Democratic presidential nominee, South Dakota Senator

In 1980, Agnew published a memoir, ''Go Quietly ... or Else''. In it, he protested his total innocence of the charges that had brought his resignation. His assertions of innocence were undermined when his former lawyer George White testified that his client had admitted statehouse bribery to him, saying it had been going on "for a thousand years". Agnew also made a new claim: that he resigned because he had been warned by White House Chief of Staff

In 1980, Agnew published a memoir, ''Go Quietly ... or Else''. In it, he protested his total innocence of the charges that had brought his resignation. His assertions of innocence were undermined when his former lawyer George White testified that his client had admitted statehouse bribery to him, saying it had been going on "for a thousand years". Agnew also made a new claim: that he resigned because he had been warned by White House Chief of Staff

FBI files on Spiro Agnew

Papers of Spiro T. Agnew at the University of Maryland Libraries

Prosecution's summary of the evidence against Agnew

* , - , - , - , - {{DEFAULTSORT:Agnew, Spiro 1918 births 1996 deaths 1968 United States vice-presidential candidates 1972 United States vice-presidential candidates 20th-century American memoirists 20th-century American novelists 20th-century Maryland politicians 20th-century vice presidents of the United States American government officials convicted of crimes American people convicted of tax crimes American people of Greek descent American politicians convicted of bribery American anti-Zionists Baltimore County executives Burials at Dulaney Valley Memorial Gardens Deaths from leukemia in Maryland Deaths from acute leukemia Disbarred Maryland lawyers Episcopalians from Maryland Republican Party governors of Maryland Greek Protestants Johns Hopkins University alumni Lawyers from Baltimore Maryland politicians convicted of crimes Military personnel from Baltimore Nixon administration cabinet members Nixon administration controversies People from Rancho Mirage, California People from Towson, Maryland Politicians from Baltimore County, Maryland Politicians from Baltimore Republican Party (United States) vice presidential nominees Republican Party vice presidents of the United States Richard Nixon 1968 presidential campaign Richard Nixon 1972 presidential campaign United States Army officers United States Army personnel of World War II University of Baltimore School of Law alumni Vice presidents of the United States Right-wing populists in the United States

vice president of the United States

The vice president of the United States (VPOTUS) is the second-highest ranking office in the Executive branch of the United States government, executive branch of the U.S. federal government, after the president of the United States, and ranks f ...

, serving from 1969 until his resignation in 1973. He is the second of two vice presidents to resign, the first being John C. Calhoun in 1832.

Agnew was born in Baltimore

Baltimore is the most populous city in the U.S. state of Maryland. With a population of 585,708 at the 2020 census and estimated at 568,271 in 2024, it is the 30th-most populous U.S. city. The Baltimore metropolitan area is the 20th-large ...

to a Greek

Greek may refer to:

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor of all kno ...

immigrant father and an American mother. He attended Johns Hopkins University

The Johns Hopkins University (often abbreviated as Johns Hopkins, Hopkins, or JHU) is a private university, private research university in Baltimore, Maryland, United States. Founded in 1876 based on the European research institution model, J ...

and graduated from the University of Baltimore School of Law. He was a campaign aide for U.S. Representative James Devereux in the 1950s, and was appointed to the Baltimore County Board of Zoning Appeals in 1957. In 1962, he was elected Baltimore county executive. In 1966, Agnew was elected governor of Maryland, defeating his Democratic opponent George P. Mahoney and independent candidate Hyman A. Pressman.

At the 1968 Republican National Convention, Richard Nixon

Richard Milhous Nixon (January 9, 1913April 22, 1994) was the 37th president of the United States, serving from 1969 until Resignation of Richard Nixon, his resignation in 1974. A member of the Republican Party (United States), Republican ...

asked Agnew to place his name in nomination, and named him as running mate. Agnew's centrist reputation interested Nixon; the law and order stance he had taken in the wake of civil unrest that year appealed to aides such as Pat Buchanan

Patrick Joseph Buchanan ( ; born November 2, 1938) is an American paleoconservative author, political commentator, and politician. He was an assistant and special consultant to U.S. presidents Richard Nixon, Gerald Ford, and Ronald Reagan. He ...

. Agnew made a number of gaffes during the campaign, but his rhetoric pleased many Republicans, and he may have made the difference in several key states. Nixon and Agnew defeated the Democratic ticket of incumbent vice president Hubert Humphrey and his running mate, Senator Edmund Muskie

Edmund Sixtus Muskie (March 28, 1914March 26, 1996) was an American statesman and political leader who served as the 58th United States Secretary of State under President Jimmy Carter from 1980 to 1981, a United States Senator from Maine from 1 ...

, and American Independent Party

The American Independent Party (AIP) is an American political party that was established in 1967. The American Independent Party is best known for its nomination of Democratic then-former Governor George Wallace of Alabama, who carried five s ...

candidates George Wallace

George Corley Wallace Jr. (August 25, 1919 – September 13, 1998) was an American politician who was the 45th and longest-serving governor of Alabama (1963–1967; 1971–1979; 1983–1987), and the List of longest-serving governors of U.S. s ...

and Curtis LeMay

Curtis Emerson LeMay (November 15, 1906 – October 1, 1990) was a United States Air Force, US Air Force General (United States), general who was a key American military commander during the Cold War. He served as Chief of Staff of the United St ...

. As vice president, Agnew was often called upon to attack the administration's enemies. In the years of his vice presidency, Agnew moved to the right, appealing to conservatives who were suspicious of moderate stances taken by Nixon. In the presidential election of 1972, Nixon and Agnew were re-elected for a second term, defeating Senator George McGovern

George Stanley McGovern (July 19, 1922 – October 21, 2012) was an American politician, diplomat, and historian who was a U.S. representative and three-term U.S. senator from South Dakota, and the Democratic Party (United States), Democ ...

and his running mate Sargent Shriver in one of the largest landslides in American history.

In 1973, Agnew was investigated by the United States Attorney for the District of Maryland on suspicion of criminal conspiracy

In criminal law, a conspiracy is an agreement between two or more people to commit a crime at some time in the future. Criminal law in some countries or for some conspiracies may require that at least one overt act be undertaken in furtherance ...

, bribery

Bribery is the corrupt solicitation, payment, or Offer and acceptance, acceptance of a private favor (a bribe) in exchange for official action. The purpose of a bribe is to influence the actions of the recipient, a person in charge of an official ...

, extortion

Extortion is the practice of obtaining benefit (e.g., money or goods) through coercion. In most jurisdictions it is likely to constitute a criminal offence. Robbery is the simplest and most common form of extortion, although making unfounded ...

, and tax fraud

Tax evasion or tax fraud is an illegal attempt to defeat the imposition of taxes by individuals, corporations, trust (property), trusts, and others. Tax evasion often entails the deliberate misrepresentation of the taxpayer's affairs to the tax au ...

. Agnew took kickbacks from contractors during his time as Baltimore county executive and governor of Maryland

The governor of the State of Maryland is the head of government of Maryland, and is the commander-in-chief of the state's National Guard units. The governor is the highest-ranking official in the state and has a broad range of appointive powers ...

. The payments had continued into his time as vice president, but had nothing to do with the Watergate scandal

The Watergate scandal was a major political scandal in the United States involving the Presidency of Richard Nixon, administration of President Richard Nixon. The scandal began in 1972 and ultimately led to Resignation of Richard Nixon, Nix ...

, in which he was not implicated. After months of maintaining his innocence, Agnew pleaded no contest to a single felony charge of tax evasion

Tax evasion or tax fraud is an illegal attempt to defeat the imposition of taxes by individuals, corporations, trusts, and others. Tax evasion often entails the deliberate misrepresentation of the taxpayer's affairs to the tax authorities to red ...

and resigned from office. Nixon replaced him with House Republican leader Gerald Ford

Gerald Rudolph Ford Jr. (born Leslie Lynch King Jr.; July 14, 1913December 26, 2006) was the 38th president of the United States, serving from 1974 to 1977. A member of the Republican Party (United States), Republican Party, Ford assumed the p ...

. Agnew spent the remainder of his life quietly, rarely making public appearances and blaming Zionists for forcing him out of office. He wrote a novel and a memoir, both of which defended his actions. Agnew died at home in 1996 at age 77 of undiagnosed acute leukemia.

Early life

Family background

Spiro Agnew's father was born Theophrastos Anagnostopoulos in about 1877, in the Greek town ofGargalianoi

Gargalianoi () is a town and a former municipality in Messenia, Peloponnese, Greece. Since the 2011 local government reform it is part of the municipality Trifylia, of which it is a municipal unit. The municipal unit has an area of 122.680 ...

, Messenia

Messenia or Messinia ( ; ) is a regional unit (''perifereiaki enotita'') in the southwestern part of the Peloponnese region, in Greece. Until the implementation of the Kallikratis plan on 1 January 2011, Messenia was a prefecture (''nomos' ...

. The family may have been involved in olive growing and been impoverished during a crisis in the industry in the 1890s. Anagnostopoulos emigrated to the United States in 1897 (some accounts say 1902) and settled in Schenectady, New York

Schenectady ( ) is a City (New York), city in Schenectady County, New York, United States, of which it is the county seat. As of the United States Census 2020, 2020 census, the city's population of 67,047 made it the state's ninth-most populo ...

, where he changed his name to Theodore Agnew and opened a diner

A diner is a type of restaurant found across the United States and Canada, as well as parts of Western Europe and Australia. Diners offer a wide range of cuisine, mostly American cuisine, a casual atmosphere, and, characteristically, a comb ...

. A passionate self-educator, Agnew maintained a lifelong interest in philosophy; one family member recalled that "if he wasn't reading something to improve his mind, he wouldn't read." Around 1908, he moved to Baltimore, where he purchased a restaurant. Here he met William Pollard, who was the city's federal meat inspector. The two became friends; Pollard and his wife Margaret were regular customers of the restaurant. After Pollard died in April 1917, Agnew and Margaret Pollard began a courtship which led to their marriage on December 12, 1917. Spiro Agnew was born 11 months later, on November 9, 1918.

Margaret Pollard, born Margaret Marian Akers in Bristol, Virginia

Bristol is an independent city (United States), independent city in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Virginia. As of the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, the population was 17,219. It is the Twin cities (geographical proxi ...

, in 1883, was the youngest in a family of 10 children. As a young adult she moved to Washington, D.C., and found employment in various government offices before marrying Pollard and moving to Baltimore. The Pollards had one son, Roy, who was 10 years old when Pollard died. After the marriage to Agnew in 1917 and Spiro's birth the following year, the new family settled in a small apartment at 226 West Madison Street, near downtown Baltimore.

Childhood, education, early career, and marriage

In accordance with his mother's wishes, the infant Spiro was baptized as anEpiscopalian

Anglicanism, also known as Episcopalianism in some countries, is a Western Christian tradition which developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the context of the Protes ...

, rather than into the Greek Orthodox Church

Greek Orthodox Church (, , ) is a term that can refer to any one of three classes of Christian Churches, each associated in some way with Christianity in Greece, Greek Christianity, Antiochian Greek Christians, Levantine Arabic-speaking Christian ...

of his father. Nevertheless, Theodore was the dominant figure within the family, and a strong influence on his son. When in 1969, after his vice presidential inauguration, Baltimore's Greek community endowed a scholarship in Theodore Agnew's name, Spiro Agnew told the gathering: "I am proud to say that I grew up in the light of my father. My beliefs are his."

During the early 1920s, the Agnews prospered. Theodore acquired a larger restaurant, the Piccadilly, and moved the family to a house in the Forest Park northwest section of the city, where Spiro attended Garrison Junior High School and later Forest Park High School. This period of affluence ended with the crash of 1929, and the restaurant closed. In 1931, the family's savings were wiped out when a local bank failed, forcing them to sell the house and move to a small apartment. Agnew later recalled how his father responded to these misfortunes: "He just shrugged it off and went to work with his hands without complaint." Theodore Agnew sold fruit and vegetables from a roadside stall, while the youthful Spiro helped the family's budget with part-time jobs, delivering groceries and distributing leaflets. As he grew up, Spiro was increasingly influenced by his peers, and began to distance himself from his Greek background. He refused his father's offer to pay for Greek language lessons, and preferred to be known by a nickname, "Ted".

In February 1937, Agnew entered Johns Hopkins University at their new Homewood campus in north Baltimore as a chemistry major. After a few months, he found the pressure of the academic work increasingly stressful, and was distracted by the family's continuing financial problems and worries about the international situation, in which war seemed likely. In 1939 he decided that his future lay in law rather than chemistry, left Johns Hopkins and began night classes at the University of Baltimore School of Law. To support himself, he took a day job as an insurance clerk with the Maryland Casualty Company at their Rotunda building on 40th Street in Roland Park.

During the three years Agnew spent at the company he rose to the position of assistant underwriter. At the office, he met a young filing clerk, Elinor Judefind, known as "Judy". She had grown up in the same part of the city as Agnew, but the two had not previously met. They began dating, became engaged, and were married in Baltimore on May 27, 1942. They had four children; Pamela Lee, James Rand, Susan Scott, and Elinor Kimberly.

War and after

World War II (1941–1945)

By the time of the marriage, Agnew had been drafted into the United States Army. Shortly after theattack on Pearl Harbor

The attack on Pearl HarborAlso known as the Battle of Pearl Harbor was a surprise military strike by the Empire of Japan on the United States Pacific Fleet at Naval Station Pearl Harbor, its naval base at Pearl Harbor on Oahu, Territory of ...

in December 1941, he began basic training

Military recruit training, commonly known as basic training or boot camp, refers to the initial instruction of new military personnel. It is a physically and psychologically intensive process, which resocializes its subjects for the unique dema ...

at Camp Croft in South Carolina

South Carolina ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It borders North Carolina to the north and northeast, the Atlantic Ocean to the southeast, and Georgia (U.S. state), Georg ...

. There, he met people from a variety of backgrounds: "I had led a very sheltered life—I became unsheltered very quickly." Eventually, Agnew was sent to the Officer Candidate School

An officer candidate school (OCS) is a military school which trains civilians and Enlisted rank, enlisted personnel in order for them to gain a Commission (document), commission as Commissioned officer, officers in the armed forces of a country. H ...

at Fort Knox

Fort Knox is a United States Army installation in Kentucky, south of Louisville and north of Elizabethtown, Kentucky, Elizabethtown. It is adjacent to the United States Bullion Depository (also known as Fort Knox), which is used to house a larg ...

in Kentucky

Kentucky (, ), officially the Commonwealth of Kentucky, is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It borders Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio to the north, West Virginia to the ...

, and on May 24, 1942—three days before his wedding—he was commissioned as a second lieutenant.

After a two-day honeymoon, Agnew returned to Fort Knox. He served there, or at nearby Fort Campbell

Fort Campbell is a United States Army installation located astride the Kentucky–Tennessee border between Hopkinsville, Kentucky and Clarksville, Tennessee (post address is located in Kentucky). Fort Campbell is home to the 101st Airborne Div ...

, for nearly two years in a variety of administrative roles, before being sent to England in March 1944 as part of the pre-D-Day

The Normandy landings were the landing operations and associated airborne operations on 6 June 1944 of the Allied invasion of Normandy in Operation Overlord during the Second World War. Codenamed Operation Neptune and often referred to as ...

build-up. He remained on standby in Birmingham

Birmingham ( ) is a City status in the United Kingdom, city and metropolitan borough in the metropolitan county of West Midlands (county), West Midlands, within the wider West Midlands (region), West Midlands region, in England. It is the Lis ...

until late in the year, when he was posted to the 54th Armored Infantry Battalion in France as a replacement officer. After briefly serving as a rifle platoon leader, Agnew commanded the battalion's service company. The battalion became part of Combat Command "B" of the 10th Armored Division, which saw action in the Battle of the Bulge

The Battle of the Bulge, also known as the Ardennes Offensive or Unternehmen Die Wacht am Rhein, Wacht am Rhein, was the last major German Offensive (military), offensive Military campaign, campaign on the Western Front (World War II), Western ...

, including the Siege of Bastogne

The siege of Bastogne () was an engagement in December 1944 between American and German forces at the Belgian town of Bastogne, as part of the larger Battle of the Bulge. The goal of the German offensive was the harbor at Antwerp. In order to re ...

—in all, "thirty-nine days in the hole of the doughnut", as one of Agnew's men put it. Thereafter, the 54th Battalion fought its way into Germany, seeing action at Mannheim

Mannheim (; Palatine German language, Palatine German: or ), officially the University City of Mannheim (), is the List of cities in Baden-Württemberg by population, second-largest city in Baden-Württemberg after Stuttgart, the States of Ger ...

, Heidelberg

Heidelberg (; ; ) is the List of cities in Baden-Württemberg by population, fifth-largest city in the States of Germany, German state of Baden-Württemberg, and with a population of about 163,000, of which roughly a quarter consists of studen ...

, and Crailsheim

Crailsheim () is a town in the States of Germany, German state of Baden-Württemberg. Incorporated in 1338, it lies east of Schwäbisch Hall and southwest of Ansbach in the Schwäbisch Hall (district), Schwäbisch Hall district. The city's mai ...

, before reaching Garmisch-Partenkirchen

Garmisch-Partenkirchen (; ) is an Northern Limestone Alps, Alpine mountain resort, ski town in Bavaria, southern Germany. It is the seat of government of the Garmisch-Partenkirchen (district), district of Garmisch-Partenkirchen (abbreviated ...

in Bavaria as the war concluded. Agnew returned home for discharge in November 1945, having been awarded the Combat Infantryman Badge

The Combat Infantryman Badge (CIB) is a United States Army military decoration. The badge is awarded to infantrymen and Special Forces (United States Army), Special Forces soldiers in the rank of Colonel (United States), colonel and below, wh ...

and the Bronze Star

The Bronze Star Medal (BSM) is a United States Armed Forces decoration awarded to members of the United States Armed Forces for either heroic achievement, heroic service, meritorious achievement, or meritorious service in a combat zone.

Wh ...

.

Postwar years (1945–1956)

On return to civilian life, Agnew resumed his legal studies, and secured a job as alaw clerk

A law clerk, judicial clerk, or judicial assistant is a person, often a lawyer, who provides direct counsel and assistance to a lawyer or judge by Legal research, researching issues and drafting legal opinions for cases before the court. Judicial ...

with the Baltimore

Baltimore is the most populous city in the U.S. state of Maryland. With a population of 585,708 at the 2020 census and estimated at 568,271 in 2024, it is the 30th-most populous U.S. city. The Baltimore metropolitan area is the 20th-large ...

firm of Smith and Barrett. Until that time, Agnew had been largely non-political; his nominal allegiance had been to the Democratic Party, following his father's beliefs. The firm's senior partner, Lester Barrett, advised Agnew that if he wanted a career in politics, he should become a Republican. There were already many ambitious young Democrats in Baltimore and its suburbs, whereas competent, personable Republicans were scarcer. Agnew took Barrett's advice; on moving with family to the suburb of Lutherville in 1947, Agnew registered as a Republican, though he did not immediately become involved in politics.

In 1947, Agnew graduated with a

In 1947, Agnew graduated with a Bachelor of Laws

A Bachelor of Laws (; LLB) is an undergraduate law degree offered in most common law countries as the primary law degree and serves as the first professional qualification for legal practitioners. This degree requires the study of core legal subje ...

and passed the bar examination

A bar examination is an examination administered by the bar association of a jurisdiction that a lawyer must pass in order to be admitted to the bar of that jurisdiction.

Australia

Administering bar exams is the responsibility of the bar associat ...

in Maryland

Maryland ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. It borders the states of Virginia to its south, West Virginia to its west, Pennsylvania to its north, and Delaware to its east ...

. He started a law practice in downtown Baltimore, but was not successful, and took a job as an insurance investigator. A year later, Agnew moved to Schreiber's, a supermarket chain

A supermarket is a self-service Retail#Types of outlets, shop offering a wide variety of food, Drink, beverages and Household goods, household products, organized into sections. Strictly speaking, a supermarket is larger and has a wider selecti ...

, where his role was store detective. He remained there for four years, a period briefly interrupted in 1951 by a recall to the Army after the outbreak of the Korean War

The Korean War (25 June 1950 – 27 July 1953) was an armed conflict on the Korean Peninsula fought between North Korea (Democratic People's Republic of Korea; DPRK) and South Korea (Republic of Korea; ROK) and their allies. North Korea was s ...

. Agnew resigned from Schreiber's in 1952, and resumed his legal practice, specializing in labor law

Labour laws (also spelled as labor laws), labour code or employment laws are those that mediate the relationship between workers, employing entities, trade unions, and the government. Collective labour law relates to the tripartite relationship be ...

.

In 1955, Barrett was appointed a judge in Towson, the county seat

A county seat is an administrative center, seat of government, or capital city of a county or parish (administrative division), civil parish. The term is in use in five countries: Canada, China, Hungary, Romania, and the United States. An equiva ...

of Baltimore. Agnew moved his office there; at the same time, he moved his family from Lutherville to Loch Raven. There, he led a typical suburban lifestyle, serving as president of the local school district's Parent-Teacher Association, joining Kiwanis

Kiwanis International ( ) is an international service club founded in 1915 in Detroit, Michigan. It is headquartered in Indianapolis, Indiana, United States, and is found in more than 80 nations and geographic areas. In 1987, the organization ...

, and participating in a range of social and community activities. Historian William Manchester

William Raymond Manchester (April 1, 1922 – June 1, 2004) was an American author, biographer, and historian. He was the author of 18 books which have been translated into over 20 languages. He was awarded the National Humanities Medal and the ...

summed up Agnew in those days: "His favorite musician was Lawrence Welk

Lawrence Welk (March 11, 1903 – May 17, 1992) was an American accordionist, bandleader, and television impresario, who hosted ''The Lawrence Welk Show'' from 1951 to 1982. The program was known for its light and family-friendly style, and the ...

. His leisure interests were all : watching the Baltimore Colts

The Baltimore Colts were a professional American football team that played in Baltimore from 1953 to 1983, when owner Robert Irsay moved the franchise to Indianapolis. The team was named for Baltimore's history of horse breeding and racing. It w ...

on television, listening to Mantovani, and reading the sort of prose the ''Reader's Digest

''Reader's Digest'' is an American general-interest family magazine, published ten times a year. Formerly based in Chappaqua, New York, it is now headquartered in midtown Manhattan. The magazine was founded in 1922 by DeWitt Wallace and his wi ...

'' liked to condense. He was a lover of order and an almost compulsive conformist."

Beginnings in public life

Political awakening

In the 1950s, Agnew volunteered for the congressional campaigns of U.S. Representative James Devereux. Agnew made his first bid for political office in 1956, when he sought to be a Republican candidate for Baltimore County Council. He was turned down by local party leaders, but nevertheless campaigned vigorously for the Republican ticket. The election resulted in an unexpected Republican majority on the council, and in recognition for his party work, Agnew was appointed for a one-year term to the county Zoning Board of Appeals at a salary of $3,600 per year. Thisquasi-judicial

A quasi-judicial body is a non-judicial body which can interpret law. It is an entity such as an arbitration panel or tribunal board, which can be a public administrative agency (not part of the judicial branch of government) but also a contra ...

post provided an important supplement to his legal practice, and Agnew welcomed the prestige connected with the appointment. In April 1958, he was reappointed to the Board for a full three-year term and became its chairman.

In the November 1960 elections, Agnew decided to seek election to the county circuit court

Circuit courts are court systems in several common law jurisdictions. It may refer to:

* Courts that literally sit 'on circuit', i.e., judges move around a region or country to different towns or cities where they will hear cases;

* Courts that s ...

, against the local tradition that sitting judges seeking re-election were not opposed. He was unsuccessful, finishing last of five candidates. This failed attempt raised his profile, and he was regarded by his Democratic opponents as a Republican on the rise. The 1960 elections saw the Democrats win control of the county council, and one of their first actions was to remove Agnew from the Zoning Appeals Board. According to Agnew's biographer, Jules Witcover, "The publicity generated by the Democrats' crude dismissal of Agnew cast him as the honest servant wronged by the machine." Seeking to capitalize on this mood, Agnew asked to be nominated as the Republican candidate in the 1962 U.S. congressional elections, in Maryland's 2nd congressional district. The party chose the more experienced J. Fife Symington, but wanted to take advantage of Agnew's local support. He accepted their invitation to run for county executive, the county's chief executive officer; Democrats had held the executive's post and its predecessor, chairman of the board of county commissioners, since 1895.

Agnew's chances in 1962 were boosted by a feud in the Democratic ranks, as the retired former county executive, Michael Birmingham, fell out with his successor and defeated him in the Democratic primary. By contrast with his elderly opponent, Agnew was able to campaign as a "White Knight" promising change; his program included an anti-discrimination bill requiring public amenities such as parks, bars and restaurants be open to all races, policies that neither Birmingham nor any Maryland Democrat could have introduced at that time without angering supporters. In the November election, despite an intervention by Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson

Lyndon Baines Johnson (; August 27, 1908January 22, 1973), also known as LBJ, was the 36th president of the United States, serving from 1963 to 1969. He became president after the assassination of John F. Kennedy, under whom he had served a ...

on Birmingham's behalf, Agnew beat his opponent by 78,487 votes to 60,993. When Symington lost to Democrat Clarence Long in his congressional race, Agnew became the highest-ranking Republican in Maryland.

County executive

Agnew's four-year term as county executive saw a moderately progressive administration, which included the building of new schools, increases to teachers' salaries, reorganization of the police department, and improvements to the water and sewer systems. His anti-discrimination bill passed, and gave him a reputation as a liberal, but its impact was limited in a county where the population was 97 percent white. His relations with the increasingly militant civil rights movement were sometimes troubled. In a number of desegregation disputes involving private property, Agnew appeared to prioritize law and order, showing a particular aversion to any kind of demonstration. His reaction to the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing in Alabama, in which four children died, was to refuse to attend a memorial service at a Baltimore church, and to denounce a planned demonstration in support of the victims. As county executive, Agnew was sometimes criticized for being too close to rich and influential businessmen, and was accused of cronyism after bypassing the normal bidding procedures and designating three of his Republican friends as the county's insurance brokers of record, ensuring them large commissions. Agnew's standard reaction to such criticisms was to display moral indignation, denounce his opponents' "outrageous distortions", deny any wrongdoing and insist on his personal integrity; tactics which, Cohen and Witcover note, were to be seen again as he defended himself against the corruption allegations that ended his vice presidency. In the 1964 presidential election, Agnew was opposed to the Republican frontrunner, the conservativeBarry Goldwater

Barry Morris Goldwater (January 2, 1909 – May 29, 1998) was an American politician and major general in the United States Air Force, Air Force Reserve who served as a United States senator from 1953 to 1965 and 1969 to 1987, and was the Re ...

, initially supporting the moderate California senator Thomas Kuchel, a candidacy that, Witcover remarks, "died stillborn". After the failure of moderate Pennsylvania Governor William Scranton

William Warren Scranton (July 19, 1917 – July 28, 2013) was an American Republican Party (United States), Republican Party politician and diplomat. Scranton served as the 38th governor of Pennsylvania from 1963 to 1967, and as United States Am ...

's candidacy at the party convention, Agnew gave his reluctant support to Goldwater, but privately opined that the choice of so extremist a candidate had cost the Republicans any chance of victory.

Governor of Maryland (1967–1969)

Election 1966

Ku Klux Klan

The Ku Klux Klan (), commonly shortened to KKK or Klan, is an American Protestant-led Christian terrorism, Christian extremist, white supremacist, Right-wing terrorism, far-right hate group. It was founded in 1865 during Reconstruction era, ...

, and said voters must choose "between the bright, pure, courageous flame of righteousness and the fiery cross". In the November election Agnew, helped by 70 percent of the black vote, beat Mahoney by 455,318 votes (49.5 percent) to 373,543, with Pressman taking 90,899 votes.

Chesapeake Bay

The Chesapeake Bay ( ) is the largest estuary in the United States. The bay is located in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic region and is primarily separated from the Atlantic Ocean by the Delmarva Peninsula, including parts of the Ea ...

. Opponents claimed a conflict of interest, since some of Agnew's partners in the venture were simultaneously involved in business deals with the county. Agnew denied any conflict or impropriety, saying that the property involved was outside Baltimore County and his jurisdiction. Nevertheless, he sold his interest.

In office

Agnew's term as governor was marked by an agenda which included tax reform, clean water regulations, and the repeal of laws against interracial marriage. Community health programs were expanded, as were higher educational and employment opportunities for those on low incomes. Steps were taken towards ending segregation in schools. Agnew's fair housing legislation was limited, applying only to new projects above a certain size. These were the first such laws passed south of theMason–Dixon line

The Mason–Dixon line, sometimes referred to as Mason and Dixon's Line, is a demarcation line separating four U.S. states: Pennsylvania, Maryland, Delaware and West Virginia. It was Surveying, surveyed between 1763 and 1767 by Charles Mason ...

. Agnew's attempt to adopt a new state constitution was rejected by the voters in a referendum.

For the most part, Agnew remained somewhat aloof from the state legislature, preferring the company of businessmen. Some of these had been associates in his county executive days, such as Lester Matz and Walter Jones, who had been among the first to encourage him to seek the governorship. Agnew's close ties to the business community were noted by officials in the state capital of Annapolis

Annapolis ( ) is the capital of the U.S. state of Maryland. It is the county seat of Anne Arundel County and its only incorporated city. Situated on the Chesapeake Bay at the mouth of the Severn River, south of Baltimore and about east o ...

: "There always seemed to be people around him who were in business." Some suspected that, while not himself corrupt, he "allowed himself to be used by the people around him."

Agnew publicly supported civil rights, but deplored the militant tactics used by some black leaders. During the 1966 election, his record had won him the endorsement of

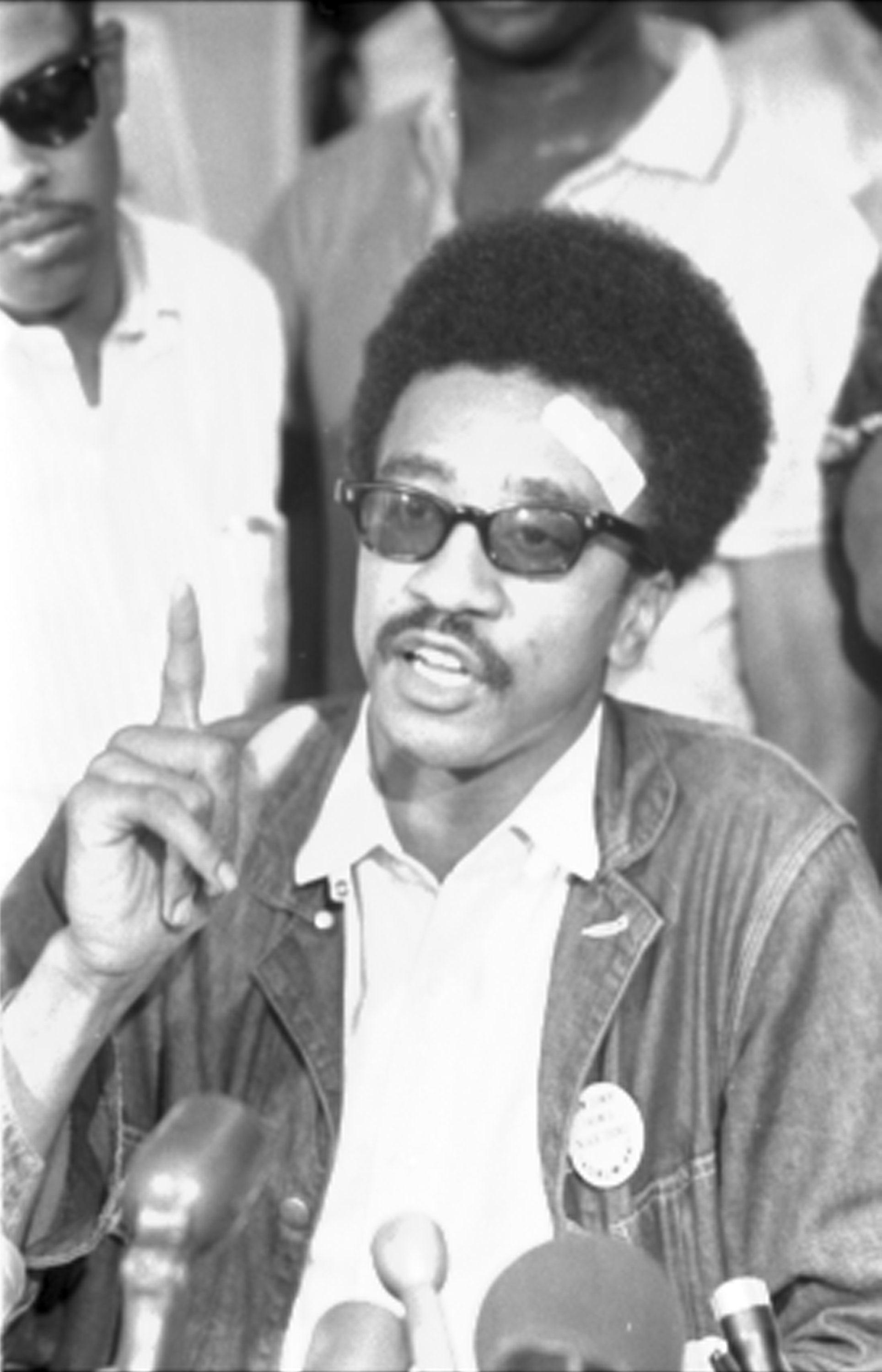

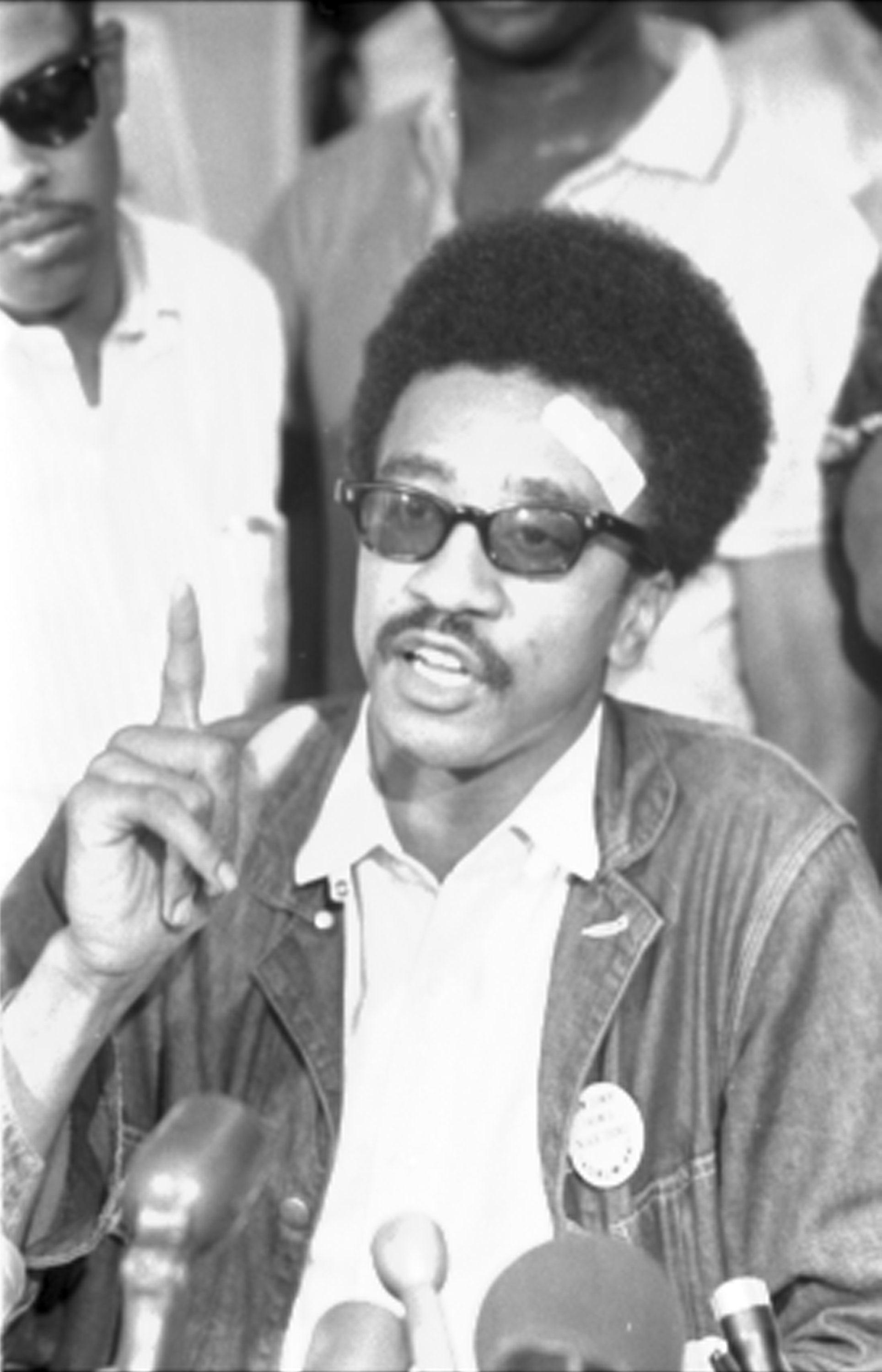

Agnew publicly supported civil rights, but deplored the militant tactics used by some black leaders. During the 1966 election, his record had won him the endorsement of Roy Wilkins

Roy Ottoway Wilkins (August 30, 1901 – September 8, 1981) was an American civil rights leader from the 1930s to the 1970s. Wilkins' most notable role was his leadership of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), ...

, leader of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) is an American civil rights organization formed in 1909 as an interracial endeavor to advance justice for African Americans by a group including W. E. B. Du&nbs ...

(NAACP). In mid-1967, racial tension was rising nationally, fueled by black discontent and an increasingly assertive civil rights leadership. Several cities exploded in violence, and there were riots in Cambridge, Maryland, after an incendiary speech there on July 24, 1967, by radical student leader H. Rap Brown. Agnew's principal concern was to maintain law and order, and he denounced Brown as a professional agitator, saying, "I hope they put him away and throw away the key." When the Kerner Commission

The National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders, known as the Kerner Commission after its chair, Governor of Illinois, Governor Otto Kerner Jr. of Illinois, was an 11-member Presidential Commission (United States), Presidential Commission es ...

, appointed by President Johnson to investigate the causes of the unrest, reported that the principal factor was institutional white racism, Agnew dismissed these findings, blaming the "permissive climate and misguided compassion" and adding: "It is not the centuries of racism and deprivation that have built to an explosive crescendo, but ... that lawbreaking has become a socially acceptable and occasionally stylish form of dissent". In March 1968, when faced with a student boycott at Bowie State College, a historically black institution, Agnew again blamed outside agitators and refused to negotiate with the students. When a student committee came to Annapolis and demanded a meeting, Agnew closed the college and ordered more than 200 arrests.

Following the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. on April 4, 1968, there was widespread rioting and disorder across the US. The trouble reached Baltimore on April 6, and for the next three days and nights the city burned. Agnew declared a state of emergency and called out the National Guard

National guard is the name used by a wide variety of current and historical uniformed organizations in different countries. The original National Guard was formed during the French Revolution around a cadre of defectors from the French Guards.

...

. When order was restored there were six dead, more than 4,000 were under arrest, the fire department had responded to 1,200 fires, and there had been widespread looting. On April 11, Agnew summoned more than 100 moderate black leaders to the state capitol, where instead of the expected constructive dialogue he delivered a speech roundly castigating them for their failure to control more radical elements, and accused them of a cowardly retreat or even complicity. One of the delegates, the Rev. Sidney Daniels, rebuked the governor: "Talk to us like we are ladies and gentlemen", he said, before walking out. Others followed him; the remnant was treated to further accusations as Agnew rejected all socio-economic explanations for the disturbances. Many white suburbanites applauded Agnew's speech: over 90 percent of the 9,000 responses by phone, letter or telegram supported him, and he won tributes from leading Republican conservatives such as Jack Williams, governor of Arizona, and former senator William Knowland

William Fife Knowland (June 26, 1908 – February 23, 1974) was an American politician and newspaper publisher. A member of the Republican Party, he served as a United States Senator from California from 1945 to 1959. He was Senate Majority L ...

of California. To members of the black community the April 11 meeting was a turning point. Having previously welcomed Agnew's stance on civil rights, they now felt betrayed, one state senator observing: "He has sold us out ... he thinks like George Wallace

George Corley Wallace Jr. (August 25, 1919 – September 13, 1998) was an American politician who was the 45th and longest-serving governor of Alabama (1963–1967; 1971–1979; 1983–1987), and the List of longest-serving governors of U.S. s ...

, he talks like George Wallace".

Vice presidential candidate (1968)

Background: Rockefeller and Nixon

At least until the April 1968 disturbances, Agnew's image was that of a liberal Republican. Since 1964 he had supported the presidential ambitions of GovernorNelson Rockefeller

Nelson Aldrich "Rocky" Rockefeller (July 8, 1908 – January 26, 1979) was the 41st vice president of the United States, serving from 1974 to 1977 under President Gerald Ford. He was also the 49th governor of New York, serving from 1959 to 197 ...

of New York, and early in 1968, with that year's elections looming, he became chairman of the "Rockefeller for President" citizens' committee. When in a televised speech on March 21, 1968, Rockefeller shocked his supporters with an apparently unequivocal withdrawal from the race, Agnew was dismayed and humiliated; despite his very public role in the Rockefeller campaign, he had received no advance warning of the decision. He took this as a personal insult and as a blow to his credibility.

Within days of Rockefeller's announcement, Agnew was being wooed by supporters of the former vice president Richard Nixon, whose campaign for the Republican nomination was well under way. Agnew had no antagonism towards Nixon, and in the wake of Rockefeller's withdrawal had indicated that Nixon might be his "second choice". When the two met in New York on March 29 they found an easy rapport. Agnew's words and actions after the April disturbances in Baltimore delighted conservative members of the Nixon camp such as Pat Buchanan, and also impressed Nixon. When on April 30 Rockefeller re-entered the race, Agnew's reaction was cool. He commended the governor as potentially a "formidable candidate" but did not commit his support: "A lot of things have happened since his withdrawal ... I think I've got to take another look at this situation".

In mid-May, Nixon, interviewed by David Broder of ''The Washington Post

''The Washington Post'', locally known as ''The'' ''Post'' and, informally, ''WaPo'' or ''WP'', is an American daily newspaper published in Washington, D.C., the national capital. It is the most widely circulated newspaper in the Washington m ...

'', mentioned the Maryland governor as a possible running mate. As Agnew continued to meet with Nixon and with the candidate's senior aides, there was a growing impression that he was moving into the Nixon camp. At the same time, Agnew denied any political ambitions beyond serving his full four-year term as governor.

Republican National Convention

As Nixon prepared for the August 1968 Republican National Convention inMiami Beach

Miami Beach is a coastal resort city in Miami-Dade County, Florida, United States. It is part of the Miami metropolitan area of South Florida. The municipality is located on natural and human-made barrier islands between the Atlantic Ocean an ...

, he discussed possible running mates with his staff. Among these were Ronald Reagan

Ronald Wilson Reagan (February 6, 1911 – June 5, 2004) was an American politician and actor who served as the 40th president of the United States from 1981 to 1989. He was a member of the Republican Party (United States), Republican Party a ...

, the conservative Governor of California

The governor of California is the head of government of the U.S. state of California. The Governor (United States), governor is the commander-in-chief of the California National Guard and the California State Guard.

Established in the Constit ...

; and the more liberal Mayor of New York City

The mayor of New York City, officially mayor of the City of New York, is head of the executive branch of the government of New York City and the chief executive of New York City. The Mayoralty in the United States, mayor's office administers all ...

, John Lindsay

John Vliet Lindsay (; November 24, 1921 – December 19, 2000) was an American politician and lawyer. During his political career, Lindsay was a U.S. congressman, the mayor of New York City, and a candidate for U.S. president. He was also a regu ...

. Nixon felt that these high-profile names could split the party, with Lindsay in particular unacceptable to Southern conservatives, and looked for a less divisive figure. He did not indicate a preferred choice, and Agnew's name was not raised at this stage. Agnew was intending to go to the convention with his Maryland delegation as a favorite son, uncommitted to any of the main candidates.

At the convention, held August 5–8, Agnew abandoned his favorite son status, placing Nixon's name in nomination. Nixon narrowly secured the nomination on the first ballot. In the discussions that followed about a running mate, Nixon kept his counsel while various party factions thought they could influence his choice: Strom Thurmond

James Strom Thurmond Sr. (December 5, 1902 – June 26, 2003) was an American politician who represented South Carolina in the United States Senate from 1954 to 2003. Before his 49 years as a senator, he served as the 103rd governor of South ...

, the senator from South Carolina, told a party meeting that he held a veto on the vice presidency. It was evident that Nixon wanted a centrist, though there was little enthusiasm when he first proposed Agnew, and other possibilities were discussed. Agnew was seen as a candidate who could appeal to Rockefeller Republicans, was acceptable to Southern Conservatives, and had a solid law-and-order record. Some party insiders thought that Nixon had privately settled on Agnew early on, and that the consideration of other candidates was little more than a charade. On August 8, after a final meeting of advisers and party leaders, Nixon declared that Agnew was his choice, and shortly afterwards announced his decision to the press. Delegates formally nominated Agnew for the vice presidency later that day, before adjourning.

In his acceptance speech, Agnew told the convention he had "a deep sense of the improbability of this moment". Agnew was not yet a national figure, and a widespread reaction to the nomination was "Spiro who?" In Atlanta

Atlanta ( ) is the List of capitals in the United States, capital and List of municipalities in Georgia (U.S. state), most populous city in the U.S. state of Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia. It is the county seat, seat of Fulton County, Georg ...

, three pedestrians gave their reactions to the name when interviewed on television: "It's some kind of disease"; "It's some kind of egg"; "He's a Greek that owns that shipbuilding firm."

Campaign

In 1968, the Nixon–Agnew ticket faced two principal opponents. The Democrats, at a convention marred by violent demonstrations, had nominated Vice President Hubert Humphrey and Maine SenatorEdmund Muskie

Edmund Sixtus Muskie (March 28, 1914March 26, 1996) was an American statesman and political leader who served as the 58th United States Secretary of State under President Jimmy Carter from 1980 to 1981, a United States Senator from Maine from 1 ...

as their standard-bearers. The segregationist former Governor of Alabama

A governor is an administrative leader and head of a polity or political region, in some cases, such as governors-general, as the head of a state's official representative. Depending on the type of political region or polity, a ''governor'' ma ...

, George Wallace

George Corley Wallace Jr. (August 25, 1919 – September 13, 1998) was an American politician who was the 45th and longest-serving governor of Alabama (1963–1967; 1971–1979; 1983–1987), and the List of longest-serving governors of U.S. s ...

, ran as a third-party candidate and was expected to do well in the Deep South

The Deep South or the Lower South is a cultural and geographic subregion of the Southern United States. The term is used to describe the states which were most economically dependent on Plantation complexes in the Southern United States, plant ...

. Nixon, mindful of the restrictions he had labored under as Dwight Eisenhower

Dwight David "Ike" Eisenhower (born David Dwight Eisenhower; October 14, 1890 – March 28, 1969) was the 34th president of the United States, serving from 1953 to 1961. During World War II, he was Supreme Commander of the Allied Expeditionar ...

's running mate in 1952 and 1956, was determined to give Agnew a much freer rein and to make it clear his running mate had his support. Agnew could also usefully play an "attack dog" role, as Nixon had in 1952.

Initially, Agnew played the centrist, pointing to his civil rights record in Maryland. As the campaign developed, he quickly adopted a more belligerent approach, with strong law-and-order rhetoric, a style which alarmed the party's Northern liberals but played well in the South. John Mitchell, Nixon's campaign manager, was impressed, some other party leaders less so; Senator Thruston Morton described Agnew as an "asshole".

Throughout September, Agnew was in the news, generally as a result of what one reporter called his "offensive and sometimes dangerous banality". He used the derogatory term "Polack" to describe Polish-Americans, referred to a Japanese-American reporter as "the fat Jap", and appeared to dismiss poor socio-economic conditions by stating that "if you've seen one slum you've seen them all." He attacked Humphrey as soft on communism, an appeaser like Britain's prewar prime minister Neville Chamberlain

Arthur Neville Chamberlain (; 18 March 18699 November 1940) was a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from May 1937 to May 1940 and Leader of the Conservative Party (UK), Leader of the Conservative Party from ...

. Agnew was mocked by his Democratic opponents; a Humphrey commercial displayed the message "Agnew for Vice President?" against a soundtrack of prolonged hysterical laughter that degenerated into a painful cough, before a final message: "This would be funny if it weren't so serious..." Agnew's comments outraged many, but Nixon did not rein him in; such right-wing populism had a strong appeal in the Southern states and was an effective counter to Wallace. Agnew's rhetoric was also popular in some Northern areas, and helped to galvanize "white backlash" into something less racially defined, more attuned to the suburban ethic defined by historian Peter B. Levy as "orderliness, personal responsibility, the sanctity of hard work, the nuclear family, and law and order".

In late October, Agnew survived an exposé in ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''NYT'') is an American daily newspaper based in New York City. ''The New York Times'' covers domestic, national, and international news, and publishes opinion pieces, investigative reports, and reviews. As one of ...

'' that questioned his financial dealings in Maryland, with Nixon denouncing the paper for "the lowest kind of gutter politics". In the election on November 5, the Republicans were victorious, with a narrow popular vote plurality – 500,000 out of a total of 73 million votes cast. The Electoral College result was more decisive: Nixon 301, Humphrey 191 and Wallace 46. The Republicans narrowly lost Maryland, but Agnew was credited by pollster Louis Harris

Louis Harris (January 6, 1921 – December 17, 2016) was an American opinion polling entrepreneur, journalist, and author. He ran one of the best-known polling organizations of his time, Louis Harris and Associates, which conducted The H ...

with helping his party to victory in several border

Borders are generally defined as geography, geographical boundaries, imposed either by features such as oceans and terrain, or by polity, political entities such as governments, sovereign states, federated states, and other administrative divisio ...

and Upper South

The Upland South and Upper South are two overlapping cultural and geographic subregions in the inland part of the Southern United States. They differ from the Deep South and Atlantic coastal plain by terrain, history, economics, demographics, ...

states that might easily have fallen to Wallace—South Carolina, North Carolina, Virginia, Tennessee and Kentucky—and with bolstering Nixon's support in suburbs nationally. Had Nixon lost those five states, he would have had only the minimum number of electoral votes needed, 270, and any defection by an elector would have thrown the election to the Democrat-controlled House of Representatives.

Vice presidency (1969–1973)

Transition and early days

Immediately after the 1968 election, Agnew was still uncertain what Nixon would expect of him as vice president. He met with Nixon several days after the election inKey Biscayne, Florida

Key Biscayne is a village in Miami-Dade County, Florida, United States. Located on the island of Key Biscayne, the village is part of the Miami metropolitan area of South Florida. The population was 14,809 at the 2020 United States census, 20 ...

. Nixon, vice president himself for eight years under Eisenhower, wanted to spare Agnew the boredom and lack of a role he had sometimes experienced in that office. Nixon initially gave Agnew an office in the West Wing of the White House, a first for a vice president, although in December 1969 it was given to deputy assistant Alexander Butterfield and Agnew had to move to an office in the Executive Office Building. When they stood before the press after the meeting, Nixon pledged that Agnew would not have to undertake the ceremonial roles usually undertaken by the holders of the vice presidency, but would have "new duties beyond what any vice president has previously assumed". Nixon told the press that he planned to make full use of Agnew's experience as county executive and as governor in dealing with matters of federal-state relations and in urban affairs.

Nixon established transition headquarters in New York, but Agnew was not invited to meet with him there until November 27, when the two met for an hour. When Agnew spoke to reporters afterwards, he stated that he felt "exhilarated" with his new responsibilities, but did not explain what those were. During the transition period, Agnew traveled extensively, enjoying his new status. He vacationed on St. Croix, where he played a round of golf with Humphrey and Muskie. He went to Memphis for the 1968 Liberty Bowl, and to New York to attend the wedding of Nixon's daughter Julie to David Eisenhower

Dwight David Eisenhower II (born March 31, 1948) is an American author, public policy fellow, lecturer at the University of Pennsylvania, and eponym of the U.S. presidential retreat Camp David. He is the grandson of President Dwight D. Eisenhowe ...

. Agnew was a fan of the Baltimore Colts; in January, he was the guest of team owner Carroll Rosenbloom at Super Bowl III

Super Bowl III was an American football championship game played on January 12, 1969, at the Miami Orange Bowl, Orange Bowl in Miami, Miami, Florida. It was the third AFL–NFL Championship Game in professional American football, and the fi ...

, and watched Joe Namath

Joseph William Namath (; ; born May 31, 1943), nicknamed "Broadway Joe", is an American former professional American football, football quarterback who played in the American Football League (AFL) and National Football League (NFL) for 13 seaso ...

and the New York Jets

The New York Jets are a professional American football team based in the New York metropolitan area. The Jets compete in the National Football League (NFL) as a member of the American Football Conference (AFC) AFC East, East division. The team p ...

upset the Colts, 16–7. There was as yet no official residence for the vice president, and Spiro and Judy Agnew secured a suite at the Sheraton Hotel in Washington formerly occupied by Johnson

Johnson may refer to:

People and fictional characters

*Johnson (surname), a common surname in English

* Johnson (given name), a list of people

* List of people with surname Johnson, including fictional characters

*Johnson (composer) (1953–2011) ...

while vice president. Only one of their children, Kim, the youngest daughter, moved there with them, the others remaining in Maryland.

During the transition, Agnew hired a staff, choosing several aides who had worked with him as county executive and as governor. He hired Charles Stanley Blair as chief of staff; Blair had been a member of the House of Delegates and served as Maryland Secretary of State under Agnew. Arthur Sohmer, Agnew's long-time campaign manager, became his political advisor, and Herb Thompson, a former journalist, became press secretary.

Agnew was sworn in along with Nixon on January 20, 1969; as was customary, he sat down immediately after being sworn in, and did not make a speech. Soon after the inauguration, Nixon appointed Agnew as head of the Office of Intergovernmental Relations, to head government commissions such as the National Space Council and assigned him to work with state governors to bring down crime. It became clear that Agnew would not be in the inner circle of advisors. The new president preferred to deal directly with only a trusted handful, and was annoyed when Agnew tried to call him about matters Nixon deemed trivial. After Agnew shared his opinions on a foreign policy matter in a cabinet meeting, an angry Nixon sent Bob Haldeman to warn Agnew to keep his opinions to himself. Nixon complained that Agnew had no idea how the vice presidency worked, but did not meet with Agnew to share his own experience of the office. Herb Klein, director of communications in the Nixon White House, later wrote that Agnew had allowed himself to be pushed around by senior aides such as Haldeman and John Mitchell, and that Nixon's "inconsistent" treatment of Agnew had left the vice president exposed.

Agnew's pride had been stung by the negative news coverage of him during the campaign, and he sought to bolster his reputation by assiduous performance of his duties. It had become usual for the vice president to preside over the Senate only if he might be needed to break a tie, but Agnew opened every session for the first two months of his term, and spent more time presiding, in his first year, than any vice president since Alben Barkley

Alben William Barkley (; November 24, 1877 – April 30, 1956) was the 35th vice president of the United States serving from 1949 to 1953 under President Harry S. Truman. In 1905, he was elected to local offices and in 1912 as a U.S. rep ...

, who held that role under Harry S. Truman

Harry S. Truman (May 8, 1884December 26, 1972) was the 33rd president of the United States, serving from 1945 to 1953. As the 34th vice president in 1945, he assumed the presidency upon the death of Franklin D. Roosevelt that year. Subsequen ...

. The first postwar vice president not to have previously been a senator, he took lessons in Senate procedures from the Parliamentarian and from a Republican committee staffer. He lunched with small groups of senators, and was initially successful in building good relations. Although silenced on foreign policy matters, he attended White House staff meetings and spoke on urban affairs; when Nixon was present, he often presented the perspective of the governors. Agnew earned praise from the other members when he presided over a meeting of the White House Domestic Council in Nixon's absence but, like Nixon during Eisenhower's illnesses, did not sit in the president's chair. Nevertheless, many of the commission assignments Nixon gave Agnew were sinecure

A sinecure ( or ; from the Latin , 'without', and , 'care') is a position with a salary or otherwise generating income that requires or involves little or no responsibility, labour, or active service. The term originated in the medieval church, ...

s, with the vice president only formally the head.

"Nixon's Nixon": attacking the left

The public image of Agnew as an uncompromising critic of the violent protests that had marked 1968 persisted into his vice presidency. At first, he tried to take a more conciliatory tone, in line with Nixon's own speeches after taking office. Still, he urged a firm line against violence, stating in a speech in Honolulu on May 2, 1969, that "we have a new breed of self-appointed vigilantes arising—the counterdemonstrators—taking the law into their own hands because officials fail to call law enforcement authorities. We have a vast faceless majority of the American public in quiet fury over the situation—''and with good reason''." On October 14, 1969, the day before the anti-war Moratorium, North Vietnamese premier Pham Van Dong released a letter supporting demonstrations in the United States. Nixon resented this, but on the advice of his aides, thought it best to say nothing, and instead had Agnew give a press conference at the White House, calling upon the Moratorium protesters to disavow the support of the North Vietnamese. Agnew handled the task well, and Nixon tasked Agnew with attacking the Democrats generally, while remaining above the fray himself. This was analogous to the role Nixon had performed as vice president in the Eisenhower White House; thus Agnew was dubbed "Nixon's Nixon". Agnew had finally found a role in the Nixon administration, one he enjoyed. Nixon had Agnew deliver a series of speeches attacking their political opponents. In New Orleans on October 19, Agnew blamed liberal elites for condoning violence by demonstrators: "a spirit of national masochism prevails, encouraged by an effete corps of impudent snobs who characterize themselves as intellectuals". The following day, inJackson, Mississippi

Jackson is the List of capitals in the United States, capital and List of municipalities in Mississippi, most populous city of the U.S. state of Mississippi. The city sits on the Pearl River (Mississippi–Louisiana), Pearl River and is locate ...

, Agnew told a Republican dinner, "for too long the South has been the punching bag for those who characterize themselves as liberal intellectuals ... their course is a course that will ultimately weaken and erode the very fiber of America." Denying Republicans had a Southern Strategy, Agnew stressed that the administration and Southern whites had much in common, including the disapproval of the elites. Levy argued that such remarks were designed to attract Southern whites to the Republican Party to help secure the re-election of Nixon and Agnew in 1972, and that Agnew's rhetoric "could have served as the blueprint for the culture wars of the next twenty-to-thirty years, including the claim that Democrats were soft on crime, unpatriotic, and favored flag burning rather than flag waving". The attendees at the speeches were enthusiastic, but other Republicans, especially from the cities, complained to the Republican National Committee

The Republican National Committee (RNC) is the primary committee of the Republican Party of the United States. Its members are chosen by the state delegations at the national convention every four years. It is responsible for developing and pr ...

that Agnew's attacks were overbroad.

In the wake of these remarks, Nixon delivered his Silent Majority

The silent majority is an unspecified large group of people in a country or group who do not express their opinions publicly. The term was popularized by U.S. President Richard Nixon in a televised address on November 3, 1969, in which he said, "A ...

speech on November 3, 1969, calling on "the great silent majority of my fellow Americans" to support the administration's policy in Vietnam. The speech was well received by the public, but less so by the press, who strongly attacked Nixon's allegations that only a minority of Americans opposed the war. Nixon speechwriter Pat Buchanan penned a speech in response, to be delivered by Agnew on November 13 in Des Moines, Iowa

Des Moines is the List of capitals in the United States, capital and List of cities in Iowa, most populous city in the U.S. state of Iowa. It is the county seat of Polk County, Iowa, Polk County with parts extending into Warren County, Iowa, Wa ...

. The White House worked to assure the maximum exposure for Agnew's speech, and the networks covered it live, making it a nationwide address, a rarity for vice presidents. According to Witcover, "Agnew made the most of it".

Historically, the press had enjoyed considerable prestige and respect to that point, though some Republicans complained of bias. But in his Des Moines speech, Agnew attacked the media, complaining that immediately after Nixon's speech, "his words and policies were subjected to instant analysis and querulous criticism ... by a small band of network commentators and self-appointed analysts, the majority of whom expressed in one way or another their hostility to what he had to say ... It was obvious that their minds were made up in advance." Agnew continued, "I am asking whether a form of censorship already exists when the news that forty million Americans receive each night is determined by a handful of men ... and filtered through a handful of commentators who admit their own set of biases".

Agnew thus put into words feelings that many Republicans and conservatives had long felt about the news media. Television network executives and commentators responded with outrage. Julian Goodman, president of NBC

The National Broadcasting Company (NBC) is an American commercial broadcast television and radio network serving as the flagship property of the NBC Entertainment division of NBCUniversal, a subsidiary of Comcast. It is one of NBCUniversal's ...

, stated that Agnew had made an "appeal to prejudice ... it is regrettable that the Vice President of the United States should deny to TV freedom of the press". Frank Stanton, head of CBS, accused Agnew of trying to intimidate the news media, and his news anchor, Walter Cronkite

Walter Leland Cronkite Jr. (November 4, 1916 – July 17, 2009) was an American broadcast journalist who served as anchorman for the ''CBS Evening News'' from 1962 to 1981. During the 1960s and 1970s, he was often cited as "the most trust ...

, agreed. The speech was praised by conservatives from both parties, and gave Agnew a following among the right. Agnew deemed the Des Moines speech one of his finest moments.

On November 20 in Montgomery, Alabama

Montgomery is the List of capitals in the United States, capital city of the U.S. state of Alabama. Named for Continental Army major general Richard Montgomery, it stands beside the Alabama River on the Gulf Coastal Plain. The population was 2 ...

, Agnew reinforced his earlier speech with an attack on ''The New York Times'' and ''The Washington Post'', again originated by Buchanan. Both papers had enthusiastically endorsed Agnew's candidacy for governor in 1966 but had castigated him as unfit for the vice presidency two years later. The ''Post'' in particular had been hostile to Nixon since the Hiss

Hiss or Hissing may refer to:

* Hiss (electromagnetic), a wave generated in the plasma of the Earth's ionosphere or magnetosphere

* Hiss (surname)

* ''Hissing'' (manhwa), a Korean manhwa series by Kang EunYoung

* Noise (electronics) or electro ...

case in the 1940s. Agnew accused the papers of sharing a narrow viewpoint alien to most Americans. Agnew alleged that the newspapers were trying to circumscribe his First Amendment right to speak of what he believed, while demanding unfettered freedom for themselves, and warned, "the day when the network commentators and even the gentlemen of ''The New York Times'' enjoyed a form of diplomatic immunity from comment and criticism of what they said is over."

After Montgomery, Nixon sought a détente with the media, and Agnew's attacks ended. Agnew's approval rating soared to 64 percent in late November, and the ''Times'' called him "a formidable political asset" to the administration. The speeches gave Agnew a power base among conservatives, and boosted his presidential chances for the 1976 election.

1970: Protesters and midterm elections

Agnew's attacks on the administration's opponents, and the flair with which he made his addresses, made him popular as a speaker at Republican fundraising events. He traveled over on behalf of the Republican National Committee in early 1970, speaking at a number of Lincoln Day events, and supplanted Reagan as the party's leading fundraiser. Agnew's involvement had Nixon's strong support. In his Chicago speech, the vice president attacked "supercilious sophisticates", while in Atlanta, he promised to continue speaking out lest he break faith with "the Silent Majority, the everyday law-abiding American who believes his country needs a strong voice to articulate his dissatisfaction with those who seek to destroy our heritage of liberty and our system of justice". Agnew continued to try to increase his influence with Nixon, against the opposition of Haldeman, who was consolidating his power as the second most powerful person in the administration. Agnew was successful in being heard at an April 22, 1970, meeting of theNational Security Council

A national security council (NSC) is usually an executive branch governmental body responsible for coordinating policy on national security issues and advising chief executives on matters related to national security. An NSC is often headed by a n ...

. An impediment to Nixon's plan for Vietnamization

Vietnamization was a failed foreign policy of the Richard Nixon administration to end U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War through a program to "expand, equip, and train South Vietnamese forces and assign to them an ever-increasing combat role, a ...

of the war in Southeast Asia was increasing Viet Cong

The Viet Cong (VC) was an epithet and umbrella term to refer to the communist-driven armed movement and united front organization in South Vietnam. It was formally organized as and led by the National Liberation Front of South Vietnam, and ...

control of parts of Cambodia, beyond the reach of South Vietnamese troops and used as sanctuaries. Feeling that Nixon was getting overly dovish advice from Secretary of State William P. Rogers and Secretary of Defense Melvin Laird, Agnew stated that if the sanctuaries were a threat, they should be attacked and neutralized. Nixon chose to attack the Viet Cong positions in Cambodia, a decision that had Agnew's support, and that he remained convinced was correct after his resignation.

The continuing student protests against the war brought Agnew's scorn. In a speech on April 28 in Hollywood, Florida, Agnew stated that responsibility of the unrest lay with those who failed to guide them, and suggested that the alumni of Yale University

Yale University is a Private university, private Ivy League research university in New Haven, Connecticut, United States. Founded in 1701, Yale is the List of Colonial Colleges, third-oldest institution of higher education in the United Stat ...

fire its president, Kingman Brewster. The Cambodia incursion brought more demonstrations on campus, and on May 3, Agnew went on ''Face the Nation

''Face the Nation'' is a weekly news and Sunday morning talk show, morning public affairs program airing Sundays on the CBS radio and Television broadcasting, television network. Created by Frank Stanton (executive), Frank Stanton in 1954, ''Fa ...

'' to defend the policy. Reminded that Nixon, in his inaugural address, had called for the lowering of voices in political discourse, Agnew commented, "When a fire takes place, a man doesn't run into the room and whisper ... he yells, 'Fire!' and I am yelling 'Fire!' because I think 'Fire!' needs to be called here". The Kent State shootings

The Kent State shootings (also known as the Kent State massacre or May 4 massacre"These would be the first of many probes into what soon became known as the Kent State Massacre. Like the Boston Massacre almost exactly two hundred years before (Ma ...

took place the following day, but Agnew did not tone down his attacks on demonstrators, alleging that he was responding to "a general malaise that argues for violent confrontation instead of debate". Nixon had Haldeman tell Agnew to avoid remarks about students; Agnew strongly disagreed and stated that he would only refrain if Nixon directly ordered it.

Nixon's agenda had been impeded by the fact that Congress was controlled by Democrats and he hoped to take control of the Senate in the 1970 midterm elections. Worried that Agnew was too divisive a figure, Nixon and his aides initially planned to restrict Agnew's role to fundraising and the giving of a standard stump speech that would avoid personal attacks. The president believed that appealing to white, middle- and lower-class voters on social issues would lead to Republican victories in November. He planned not to do any active campaigning, but to remain above the fray and let Agnew campaign as spokesman for the Silent Majority.

On September 10 in Springfield, Illinois

Springfield is the List of capitals in the United States, capital city of the U.S. state of Illinois. Its population was 114,394 at the 2020 United States census, which makes it the state's List of cities in Illinois, seventh-most populous cit ...