Sperm Whale on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The sperm whale or cachalot (''Physeter macrocephalus'') is the largest of the

The sperm whale's unique body is unlikely to be confused with any other species. The sperm whale's distinctive shape comes from its very large, block-shaped head, which can be one-quarter to one-third of the animal's length. The S-shaped blowhole is located very close to the front of the head and shifted to the whale's left. This gives rise to a distinctive bushy, forward-angled spray.

The sperm whale's flukes (tail lobes) are triangular and very thick. Proportionally, they are larger than that of any other cetacean, and are very flexible. The whale lifts its flukes high out of the water as it begins a feeding dive. It has a series of ridges on the back's caudal third instead of a

The sperm whale's unique body is unlikely to be confused with any other species. The sperm whale's distinctive shape comes from its very large, block-shaped head, which can be one-quarter to one-third of the animal's length. The S-shaped blowhole is located very close to the front of the head and shifted to the whale's left. This gives rise to a distinctive bushy, forward-angled spray.

The sperm whale's flukes (tail lobes) are triangular and very thick. Proportionally, they are larger than that of any other cetacean, and are very flexible. The whale lifts its flukes high out of the water as it begins a feeding dive. It has a series of ridges on the back's caudal third instead of a

The ribs are bound to the spine by flexible cartilage, which allows the ribcage to collapse rather than snap under high pressure. While sperm whales are well adapted to diving, repeated dives to great depths have long-term effects. Bones show the same avascular necrosis that signals

The ribs are bound to the spine by flexible cartilage, which allows the ribcage to collapse rather than snap under high pressure. While sperm whales are well adapted to diving, repeated dives to great depths have long-term effects. Bones show the same avascular necrosis that signals  Like that of all cetaceans, the spine of the sperm whale has reduced

Like that of all cetaceans, the spine of the sperm whale has reduced  Like many cetaceans, the sperm whale has a vestigial pelvis that is not connected to the spine.

Like that of other

Like many cetaceans, the sperm whale has a vestigial pelvis that is not connected to the spine.

Like that of other

The sperm whale's lower jaw is very narrow and underslung. In: The sperm whale has 18 to 26 teeth on each side of its lower jaw which fit into sockets in the upper jaw. The teeth are cone-shaped and weigh up to each. The teeth are functional, but do not appear to be necessary for capturing or eating squid, as well-fed animals have been found without teeth or even with deformed jaws. One hypothesis is that the teeth are used in aggression between males. Mature males often show scars which seem to be caused by the teeth. Rudimentary teeth are also present in the upper jaw, but these rarely emerge into the mouth. Analyzing the teeth is the preferred method for determining a whale's age. Like tree rings, the teeth build distinct layers of

The sperm whale's lower jaw is very narrow and underslung. In: The sperm whale has 18 to 26 teeth on each side of its lower jaw which fit into sockets in the upper jaw. The teeth are cone-shaped and weigh up to each. The teeth are functional, but do not appear to be necessary for capturing or eating squid, as well-fed animals have been found without teeth or even with deformed jaws. One hypothesis is that the teeth are used in aggression between males. Mature males often show scars which seem to be caused by the teeth. Rudimentary teeth are also present in the upper jaw, but these rarely emerge into the mouth. Analyzing the teeth is the preferred method for determining a whale's age. Like tree rings, the teeth build distinct layers of

The sperm whale

The sperm whale

Ghostarchive

and th

Wayback Machine

Most squid beaks are vomited by the whale, but some occasionally make it to the hindgut. Such beaks precipitate the formation of In 1959, the heart of a 22 metric-ton (24 short-ton) male taken by whalers was measured to be , about 0.5% of its total mass. The circulatory system has a number of specific adaptations for the aquatic environment. The diameter of the

In 1959, the heart of a 22 metric-ton (24 short-ton) male taken by whalers was measured to be , about 0.5% of its total mass. The circulatory system has a number of specific adaptations for the aquatic environment. The diameter of the

File:Sperm whale phonic lips (NASA).jpg, The phonic lips.

File:Sperm whale exposed frontal sac.jpg, The frontal sac, exposed. Its surface is covered with fluid-filled knobs.

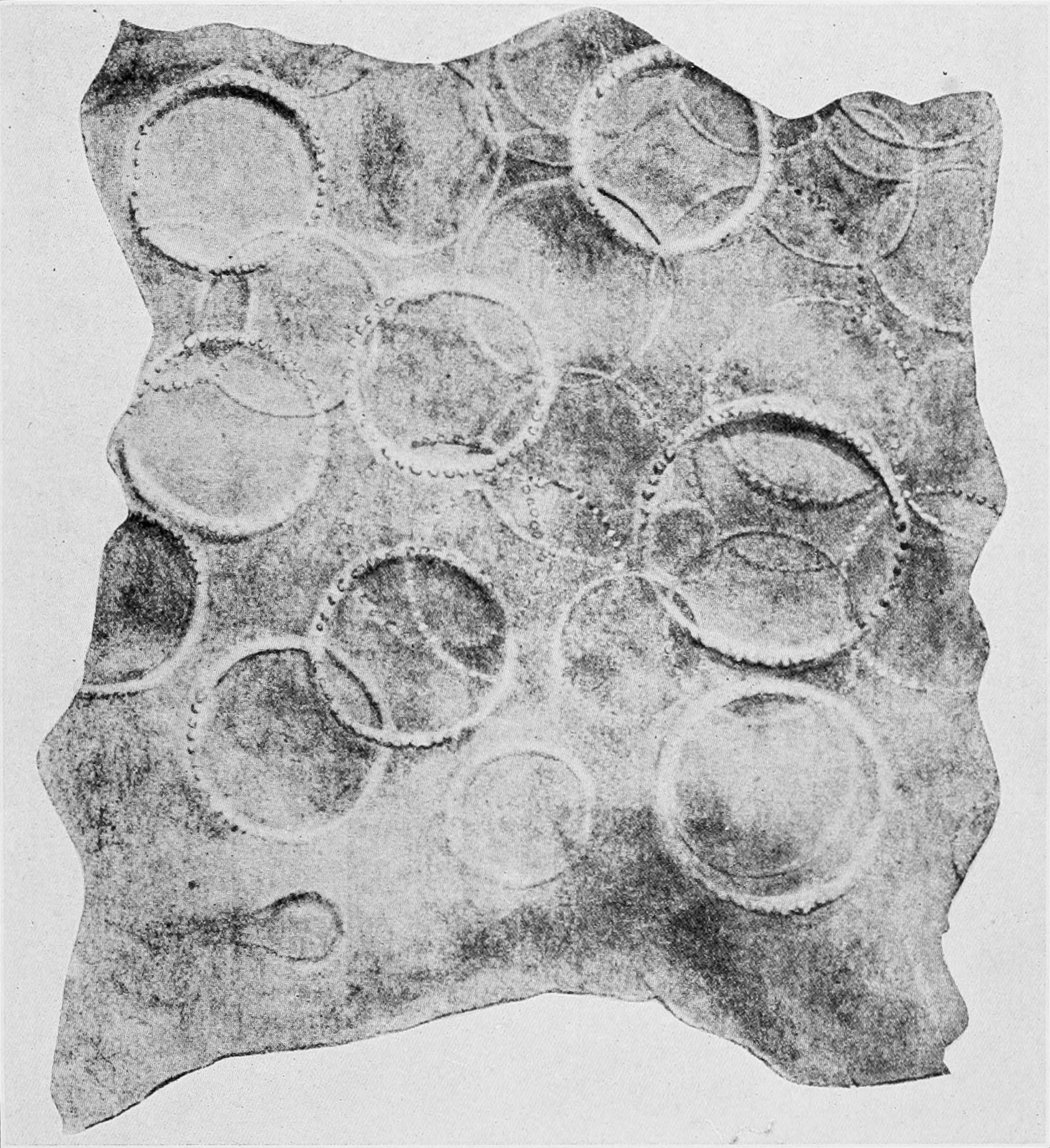

File:Sperm whale frontal sac surface close-up.jpg, A piece of the posterior wall of the frontal sac. The grooves between the knobs trap a consistent film of air, making it an excellent sound mirror.

Sperm whales usually dive between , and sometimes , in search of food. Such dives can last more than an hour. They feed on several species, notably the giant squid, but also the colossal squid,

Sperm whales usually dive between , and sometimes , in search of food. Such dives can last more than an hour. They feed on several species, notably the giant squid, but also the colossal squid,  The sharp beak of a consumed squid lodged in the whale's intestine may lead to the production of

The sharp beak of a consumed squid lodged in the whale's intestine may lead to the production of

Like elephants, females and their young live in matriarchal groups called pods, while bulls live apart. Bulls sometimes form loose bachelor groups with other males of similar age and size. As they grow older, they typically live solitary lives, only returning to the pod to socialize or to breed. Bulls have beached themselves together, suggesting a degree of cooperation which is not yet fully understood. The whales rarely, if ever, leave their group.

A ''social unit'' is a group of sperm whales who live and travel together over a period of years. Individuals rarely, if ever, join or leave a social unit. There is a huge variance in the size of social units. They are most commonly between six and nine individuals in size but can have more than twenty. Unlike

Like elephants, females and their young live in matriarchal groups called pods, while bulls live apart. Bulls sometimes form loose bachelor groups with other males of similar age and size. As they grow older, they typically live solitary lives, only returning to the pod to socialize or to breed. Bulls have beached themselves together, suggesting a degree of cooperation which is not yet fully understood. The whales rarely, if ever, leave their group.

A ''social unit'' is a group of sperm whales who live and travel together over a period of years. Individuals rarely, if ever, join or leave a social unit. There is a huge variance in the size of social units. They are most commonly between six and nine individuals in size but can have more than twenty. Unlike

The sperm whale's ivory-like teeth were often sought by 18th- and 19th-century whalers, who used them to produce inked carvings known as ''

The sperm whale's ivory-like teeth were often sought by 18th- and 19th-century whalers, who used them to produce inked carvings known as '' Sperm whales increase levels of primary production and carbon export by depositing iron-rich faeces into surface waters of the Southern Ocean. The iron-rich faeces cause phytoplankton to grow and take up more carbon from the atmosphere. When the phytoplankton dies, it sinks to the deep ocean and takes the atmospheric carbon with it. By reducing the abundance of sperm whales in the Southern Ocean, whaling has resulted in an extra 2 million tonnes of carbon remaining in the atmosphere each year.

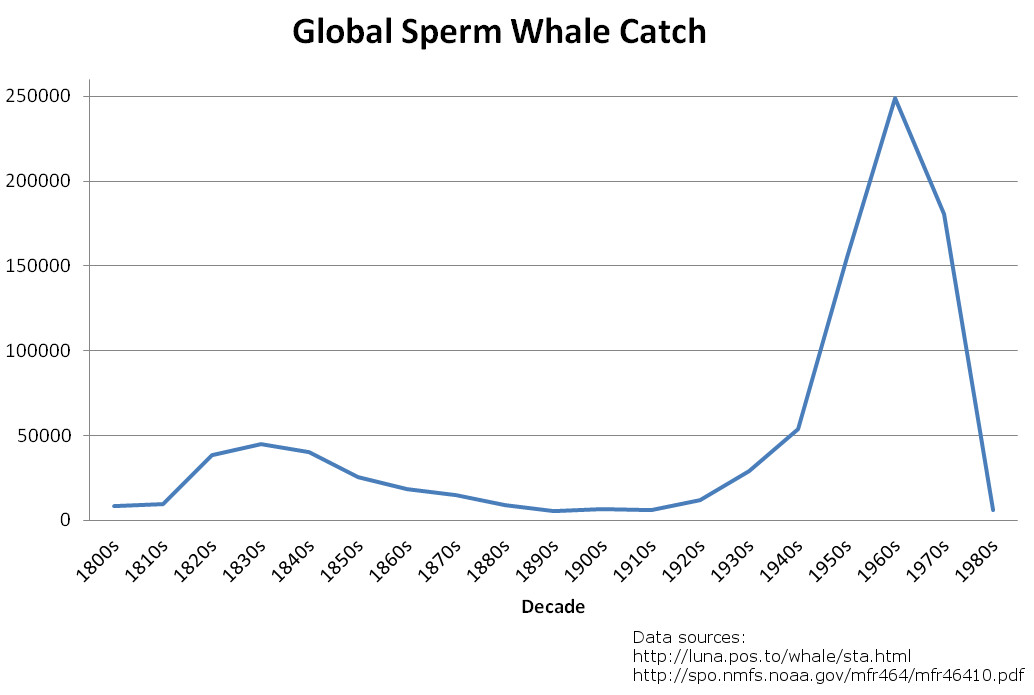

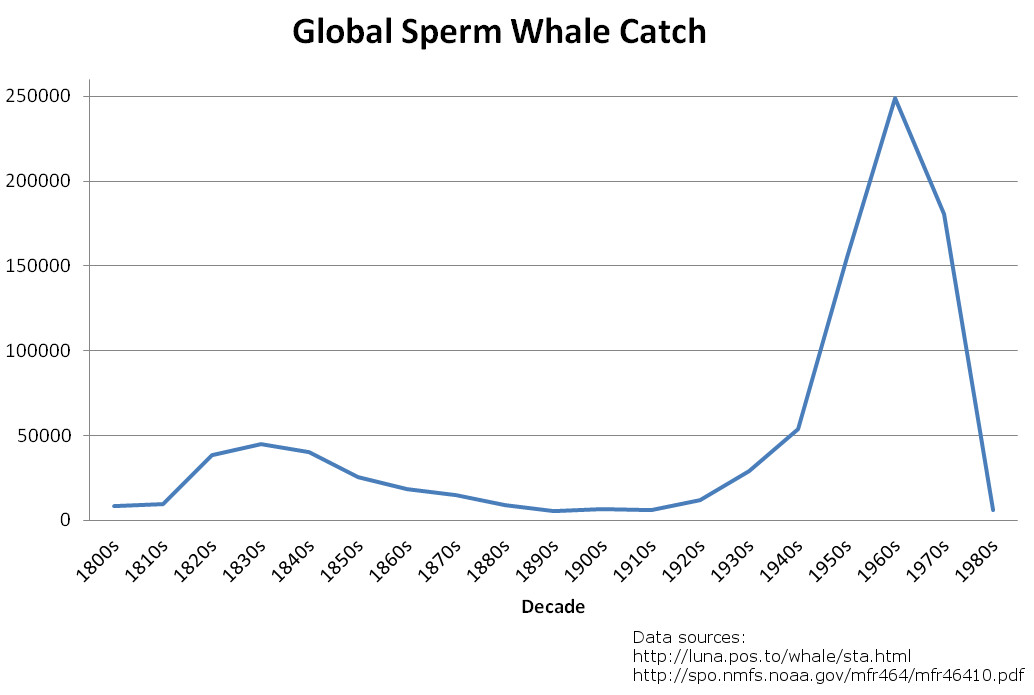

Remaining sperm whale populations are large enough that the species' conservation status is rated as vulnerable rather than endangered. However, the recovery from centuries of commercial whaling is a slow process, particularly in the South Pacific, where the toll on breeding-age males was severe.

Sperm whales increase levels of primary production and carbon export by depositing iron-rich faeces into surface waters of the Southern Ocean. The iron-rich faeces cause phytoplankton to grow and take up more carbon from the atmosphere. When the phytoplankton dies, it sinks to the deep ocean and takes the atmospheric carbon with it. By reducing the abundance of sperm whales in the Southern Ocean, whaling has resulted in an extra 2 million tonnes of carbon remaining in the atmosphere each year.

Remaining sperm whale populations are large enough that the species' conservation status is rated as vulnerable rather than endangered. However, the recovery from centuries of commercial whaling is a slow process, particularly in the South Pacific, where the toll on breeding-age males was severe.

of the Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals (CMS). As amended by the Conference of the Parties in 1985, 1988, 1991, 1994, 1997, 1999, 2002, 2005 and 2008. Effective: 5 March 2009. and Appendix II of the Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals (CMS). It is listed on Appendix I as this species has been categorized as being in danger of extinction throughout all or a significant proportion of their range and CMS Parties strive towards strictly protecting these animals, conserving or restoring the places where they live, mitigating obstacles to migration and controlling other factors that might endanger them. It is listed on Appendix II as it has an unfavourable conservation status or would benefit significantly from international co-operation organised by tailored agreements. It is also covered by the Agreement on the Conservation of Cetaceans in the Black Sea, Mediterranean Sea and Contiguous Atlantic Area (ACCOBAMS) and the Memorandum of Understanding for the Conservation of Cetaceans and Their Habitats in the Pacific Islands Region (Pacific Cetaceans MOU). The species is protected under Appendix I of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES). This makes commercial international trade (including in parts and derivatives) prohibited, with all other international trade strictly regulated through a system of permits and certificates.

The Dominica Sperm Whale Project

a long-term scientific research program focusing on the behaviour of sperm whale units.

22 July 2007

Society for Marine Mammalogy Sperm Whale Fact Sheet

70South

��information on the sperm whale

"Physty"-stranded sperm whale nursed back to health and released in 1981ARKive

��Photographs, video.

Whale Trackers

��An online documentary film exploring the sperm whales in the Mediterranean Sea.

Website of the Memorandum of Understanding for the Conservation of Cetaceans and Their Habitats in the Pacific Islands RegionOfficial website of the Agreement on the Conservation of Cetaceans in the Black Sea, Mediterranean Sea and Contiguous Atlantic Area

Retroposon analysis of major cetacean lineages: The monophyly of toothed whales and the paraphyly of river dolphins

19 June 2001

Sperm whales quickly learned to avoid humans who were hunting them in the 19th century, scientists say

toothed whale

The toothed whales (also called odontocetes, systematic name Odontoceti) are a parvorder of cetaceans that includes dolphins, porpoises, and all other whales with teeth, such as beaked whales and the sperm whales. 73 species of toothed wha ...

s and the largest toothed predator

Predation is a biological interaction in which one organism, the predator, kills and eats another organism, its prey. It is one of a family of common List of feeding behaviours, feeding behaviours that includes parasitism and micropredation ...

. It is the only living member of the genus

Genus (; : genera ) is a taxonomic rank above species and below family (taxonomy), family as used in the biological classification of extant taxon, living and fossil organisms as well as Virus classification#ICTV classification, viruses. In bino ...

'' Physeter'' and one of three extant species

A species () is often defined as the largest group of organisms in which any two individuals of the appropriate sexes or mating types can produce fertile offspring, typically by sexual reproduction. It is the basic unit of Taxonomy (biology), ...

in the sperm whale superfamily Physeteroidea

Physeteroidea is a superfamily (taxonomy), superfamily that includes three extant taxon, extant species of whales: the sperm whale, in the genus ''Physeter'', and the pygmy sperm whale and dwarf sperm whale, in the genus ''Kogia''. In the past, t ...

, along with the pygmy sperm whale

The pygmy sperm whale (''Kogia breviceps'') is one of two extant species in the family Kogiidae in the Physeteroidea, sperm whale superfamily. They are not often sighted at sea, and most of what is known about them comes from the examination of ...

and dwarf sperm whale

The dwarf sperm whale (''Kogia sima'') is a sperm whale that inhabits temperate and tropical oceans worldwide, in particular continental shelves and slopes. It was first described by biologist Richard Owen in 1866, based on illustrations by na ...

of the genus '' Kogia''.

The sperm whale is a pelagic

The pelagic zone consists of the water column of the open ocean and can be further divided into regions by depth. The word ''pelagic'' is derived . The pelagic zone can be thought of as an imaginary cylinder or water column between the sur ...

mammal

A mammal () is a vertebrate animal of the Class (biology), class Mammalia (). Mammals are characterised by the presence of milk-producing mammary glands for feeding their young, a broad neocortex region of the brain, fur or hair, and three ...

with a worldwide range, and will migrate seasonally for feeding and breeding. Females and young males live together in groups, while mature males (bulls) live solitary lives outside of the mating season. The females cooperate to protect and nurse

Nursing is a health care profession that "integrates the art and science of caring and focuses on the protection, promotion, and optimization of health and human functioning; prevention of illness and injury; facilitation of healing; and alle ...

their young. Females give birth every four to twenty years, and care for the calves for more than a decade. A mature, healthy sperm whale has no natural predators, although calves and weakened adults are sometimes killed by pods of killer whale

The orca (''Orcinus orca''), or killer whale, is a toothed whale and the largest member of the oceanic dolphin family. The only extant species in the genus '' Orcinus'', it is recognizable by its black-and-white-patterned body. A cosmopolit ...

s (orcas).

Mature males average in length, with the head representing up to one-third of the animal's length. Plunging to , it is the third deepest diving mammal, exceeded only by the southern elephant seal

The southern elephant seal (''Mirounga leonina'') is one of two species of elephant seals. It is the largest member of the clade Pinnipedia and the order Carnivora, as well as the largest extant marine mammal that is not a cetacean. It gets its ...

and Cuvier's beaked whale

Cuvier's beaked whale, goose-beaked whale, or ziphius (''Ziphius cavirostris'') is the most widely distributed of all beaked whales in the family Beaked whale, Ziphiidae. It is smaller than most baleen whales—and indeed the larger Toothed whal ...

. The sperm whale uses echolocation and vocalization with source level as loud as 236 decibel

The decibel (symbol: dB) is a relative unit of measurement equal to one tenth of a bel (B). It expresses the ratio of two values of a Power, root-power, and field quantities, power or root-power quantity on a logarithmic scale. Two signals whos ...

s (re 1 μPa m) underwater, the loudest of any animal. It has the largest brain on Earth, more than five times heavier than a human's. Sperm whales can live 70 years or more.

Sperm whales' heads are filled with a waxy substance called "spermaceti

Spermaceti (see also: Sperm oil) is a waxy substance found in the head cavities of the sperm whale (and, in smaller quantities, in the oils of other whales). Spermaceti is created in the spermaceti organ inside the whale's head. This organ may ...

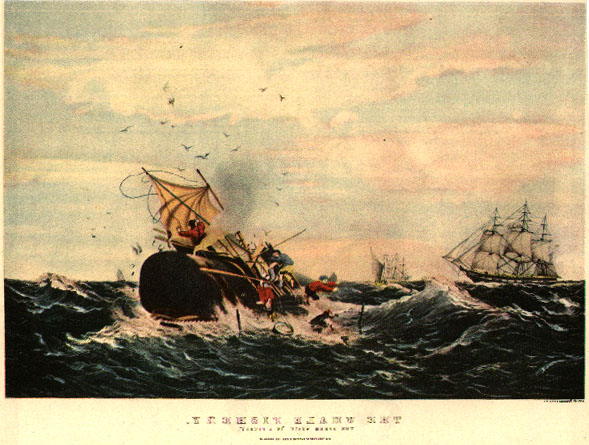

" (sperm oil), from which the whale derives its name. Spermaceti was a prime target of the whaling

Whaling is the hunting of whales for their products such as meat and blubber, which can be turned into a type of oil that was important in the Industrial Revolution. Whaling was practiced as an organized industry as early as 875 AD. By the 16t ...

industry and was sought after for use in oil lamps, lubricants, and candles. Ambergris

Ambergris ( or ; ; ), ''ambergrease'', or grey amber is a solid, waxy, flammable substance of a dull grey or blackish colour produced in the digestive system of sperm whales. Freshly produced ambergris has a marine, fecal odor. It acquires a sw ...

, a solid waxy waste product sometimes present in its digestive system, is still highly valued as a fixative in perfumes, among other uses. Beachcombers look out for ambergris as flotsam. Sperm whaling was a major industry in the 19th century, depicted in the novel ''Moby-Dick

''Moby-Dick; or, The Whale'' is an 1851 Epic (genre), epic novel by American writer Herman Melville. The book is centered on the sailor Ishmael (Moby-Dick), Ishmael's narrative of the maniacal quest of Captain Ahab, Ahab, captain of the whaler ...

''. The species is protected by the International Whaling Commission

The International Whaling Commission (IWC) is a specialised regional fishery management organisation, established under the terms of the 1946 International Convention for the Regulation of Whaling (ICRW) to "provide for the proper conservation ...

moratorium, and is listed as vulnerable by the International Union for Conservation of Nature

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) is an international organization working in the field of nature conservation and sustainable use of natural resources. Founded in 1948, IUCN has become the global authority on the stat ...

.

Taxonomy and naming

Etymology

The name "sperm whale" is a clipping of "spermaceti whale".Spermaceti

Spermaceti (see also: Sperm oil) is a waxy substance found in the head cavities of the sperm whale (and, in smaller quantities, in the oils of other whales). Spermaceti is created in the spermaceti organ inside the whale's head. This organ may ...

, originally mistakenly identified as the whales' semen

Semen, also known as seminal fluid, is a bodily fluid that contains spermatozoon, spermatozoa which is secreted by the male gonads (sexual glands) and other sexual organs of male or hermaphrodite, hermaphroditic animals. In humans and placen ...

, is the semi-liquid, waxy substance found within the whale's head.

(''See " Spermaceti organ and melon" below.'')

The sperm whale is also known as the "cachalot", which is thought to derive from the archaic French for 'tooth' or 'big teeth', as preserved for example in the word in the Gascon dialect (a word of either Romance

or Basque

Basque may refer to:

* Basques, an ethnic group of Spain and France

* Basque language, their language

Places

* Basque Country (greater region), the homeland of the Basque people with parts in both Spain and France

* Basque Country (autonomous co ...

origin).

The etymological dictionary of Corominas says the origin is uncertain, but it suggests that it comes from the Vulgar Latin

Vulgar Latin, also known as Colloquial, Popular, Spoken or Vernacular Latin, is the range of non-formal Register (sociolinguistics), registers of Latin spoken from the Crisis of the Roman Republic, Late Roman Republic onward. ''Vulgar Latin'' a ...

'sword hilts'. The word ''cachalot'' came to English via French from Spanish or Portuguese , perhaps from Galician/Portuguese 'big head'.

The term is retained in the Russian word for the animal, (), as well as in many other languages.

The scientific genus name ''Physeter'' comes from the Greek

Greek may refer to:

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor of all kno ...

(), meaning 'blowpipe, blowhole (of a whale)', or – as a ''pars pro toto

; ; ), is a figure of speech where the name of a ''portion'' of an object, place, or concept is used or taken to represent its entirety. It is distinct from a merism, which is a reference to a whole by an enumeration of parts; and metonymy, where ...

'' – 'whale'.

The specific name ''macrocephalus'' is Latinized from the Greek ( 'big-headed'), from () + ().

Its synonymous specific name ''catodon'' means 'down-tooth', from the Greek elements ('below') and ('tooth'); so named because it has visible teeth only in its lower jaw. (''See " Jaws and teeth" below.'')

Another synonym ''australasianus'' ('Australasia

Australasia is a subregion of Oceania, comprising Australia, New Zealand (overlapping with Polynesia), and sometimes including New Guinea and surrounding islands (overlapping with Melanesia). The term is used in a number of different context ...

n') was applied to sperm whales in the Southern Hemisphere.

Taxonomy

The sperm whale belongs to theorder

Order, ORDER or Orders may refer to:

* A socio-political or established or existing order, e.g. World order, Ancien Regime, Pax Britannica

* Categorization, the process in which ideas and objects are recognized, differentiated, and understood

...

Cetartiodactyla

Artiodactyls are placental mammals belonging to the order (biology), order Artiodactyla ( , ). Typically, they are ungulates which bear weight equally on two (an even number) of their five toes (the third and fourth, often in the form of a hoof ...

, the order containing all cetaceans

Cetacea (; , ) is an infraorder of aquatic mammals belonging to the order Artiodactyla that includes whales, dolphins and porpoises. Key characteristics are their fully aquatic lifestyle, streamlined body shape, often large size and exclusively c ...

and even-toed ungulates. It is a member of the unranked clade Cetacea

Cetacea (; , ) is an infraorder of aquatic mammals belonging to the order Artiodactyla that includes whales, dolphins and porpoises. Key characteristics are their fully aquatic lifestyle, streamlined body shape, often large size and exclusively c ...

, with all the whales, dolphins, and porpoises, and further classified into Odontoceti

The toothed whales (also called odontocetes, systematic name Odontoceti) are a parvorder of cetaceans that includes dolphins, porpoises, and all other whales with teeth, such as beaked whales and the sperm whales. 73 species of toothed whales ar ...

, containing all the toothed whales and dolphins. It is the sole extant species of its genus, '' Physeter'', in the family Physeteridae

Physeteroidea is a superfamily that includes three extant species of whales: the sperm whale, in the genus '' Physeter'', and the pygmy sperm whale and dwarf sperm whale, in the genus ''Kogia''. In the past, these genera have sometimes been unit ...

. Two species of the related extant genus '' Kogia'', the pygmy sperm whale

The pygmy sperm whale (''Kogia breviceps'') is one of two extant species in the family Kogiidae in the Physeteroidea, sperm whale superfamily. They are not often sighted at sea, and most of what is known about them comes from the examination of ...

''Kogia breviceps'' and the dwarf sperm whale

The dwarf sperm whale (''Kogia sima'') is a sperm whale that inhabits temperate and tropical oceans worldwide, in particular continental shelves and slopes. It was first described by biologist Richard Owen in 1866, based on illustrations by na ...

''K. sima'', are placed either in this family or in the family Kogiidae

Kogiidae is a family comprising at least two extant species of Cetacea, the pygmy (''Kogia breviceps)'' and dwarf (''K. sima)'' sperm whales. As their common names suggest, they somewhat resemble sperm whales, with squared heads and small lower ...

. In some taxonomic schemes the families Kogiidae

Kogiidae is a family comprising at least two extant species of Cetacea, the pygmy (''Kogia breviceps)'' and dwarf (''K. sima)'' sperm whales. As their common names suggest, they somewhat resemble sperm whales, with squared heads and small lower ...

and Physeteridae

Physeteroidea is a superfamily that includes three extant species of whales: the sperm whale, in the genus '' Physeter'', and the pygmy sperm whale and dwarf sperm whale, in the genus ''Kogia''. In the past, these genera have sometimes been unit ...

are combined as the superfamily Physeteroidea

Physeteroidea is a superfamily (taxonomy), superfamily that includes three extant taxon, extant species of whales: the sperm whale, in the genus ''Physeter'', and the pygmy sperm whale and dwarf sperm whale, in the genus ''Kogia''. In the past, t ...

(see the separate entry on the sperm whale family

Physeteroidea is a superfamily (taxonomy), superfamily that includes three extant taxon, extant species of whales: the sperm whale, in the genus ''Physeter'', and the pygmy sperm whale and dwarf sperm whale, in the genus ''Kogia''. In the past, t ...

).

Swedish ichthyologist Peter Artedi

Peter Artedi or Petrus Arctaedius (27 February 170528 September 1735) was a Swedish naturalist and collaborator of Carolus Linnaeus. He is sometimes known as the "father of ichthyology" for his pioneering work in classifying the fishes into gro ...

described it as ''Physeter catodon'' in his 1738 work ''Genera piscium'', from the report of a beached specimen in Orkney in 1693 and two beached in the Netherlands in 1598 and 1601. The 1598 specimen was near Berkhey.

The sperm whale is one of the species originally described by Carl Linnaeus

Carl Linnaeus (23 May 1707 – 10 January 1778), also known after ennoblement in 1761 as Carl von Linné,#Blunt, Blunt (2004), p. 171. was a Swedish biologist and physician who formalised binomial nomenclature, the modern system of naming o ...

in his landmark 1758 10th edition of ''Systema Naturae''. He recognised four species in the genus ''Physeter''. Experts soon realised that just one such species exists, although there has been debate about whether this should be named ''P. catodon'' or ''P. macrocephalus'', two of the names used by Linnaeus. Both names are still used, although most recent authors now accept ''macrocephalus'' as the valid name, limiting ''catodon'' status to a lesser synonym. Until 1974, the species was generally known as ''P. catodon''. In that year, however, Dutch zoologists Antonius M. Husson and Lipke Holthuis

Lipke Bijdeley Holthuis (21 April 1921 – 7 March 2008) was a Dutch carcinologist, considered one of the "undisputed greats" of carcinology, and "the greatest carcinologist of our time".

Holthuis was born in Probolinggo, East Java and obtained ...

proposed that the correct name should be ''P. macrocephalus'', the second name in the genus ''Physeter'' published by Linnaeus concurrently with ''P. catodon''.

This proposition was based on the grounds that the names were synonyms published simultaneously, and, therefore, the ICZN Principle of the First Reviser should apply. In this instance, it led to the choice of ''P. macrocephalus'' over ''P. catodon'', a view re-stated in Holthuis, 1987. This has been adopted by most subsequent authors, although Schevill (1986 and 1987) argued that ''macrocephalus'' was published with an inaccurate description and that therefore only the species ''catodon'' was valid, rendering the principle of "First Reviser" inapplicable. The most recent version of ITIS

The Integrated Taxonomic Information System (ITIS) is an American partnership of federal agencies designed to provide consistent and reliable information on the taxonomy of biological species. ITIS was originally formed in 1996 as an interagenc ...

has altered its usage from ''P. catodon'' to ''P. macrocephalus'', following L. B. Holthuis and more recent (2008) discussions with relevant experts. Furthermore, The Taxonomy Committee of the Society for Marine Mammalogy

The Society for Marine Mammalogy was founded in 1981 and is the largest international association of marine mammal scientists in the world.

Mission

The mission of the Society for Marine Mammalogy (SMM) is to promote the global advancement of mari ...

, the largest international association of marine mammal scientists in the world, officially uses ''Physeter macrocephalus'' when publishing their definitive list of marine mammal species.

Biology

External appearance

The sperm whale is the largest toothed whale and is among the mostsexually dimorphic

Sexual dimorphism is the condition where sexes of the same species exhibit different Morphology (biology), morphological characteristics, including characteristics not directly involved in reproduction. The condition occurs in most dioecy, di ...

of all cetacean

Cetacea (; , ) is an infraorder of aquatic mammals belonging to the order Artiodactyla that includes whales, dolphins and porpoises. Key characteristics are their fully aquatic lifestyle, streamlined body shape, often large size and exclusively c ...

s. Both sexes are about the same size at birth, but mature males are typically 30% to 50% longer and three times as massive as females.

Newborn sperm whales are usually between long. Female sperm whales are sexually mature at in length, whilst males are sexually mature at . Female sperm whales are physically mature at about in length and generally do not achieve lengths greater than . The largest female sperm whale measured up to long, and an individual of such size would have weighed about . Male sperm whales are physically mature at about in length, and larger males can generally achieve . A male sperm whale measuring in length is estimated to have weighed . By contrast, the second largest toothed whale ( Baird's beaked whale) measures up to and weighs up to .

There are occasional reports of individual sperm whales achieving even greater lengths, with some historical claims reaching or exceeding . One example is the whale that sank the ''Essex

Essex ( ) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in the East of England, and one of the home counties. It is bordered by Cambridgeshire and Suffolk to the north, the North Sea to the east, Kent across the Thames Estuary to the ...

'' (one of the incidents behind ''Moby-Dick

''Moby-Dick; or, The Whale'' is an 1851 Epic (genre), epic novel by American writer Herman Melville. The book is centered on the sailor Ishmael (Moby-Dick), Ishmael's narrative of the maniacal quest of Captain Ahab, Ahab, captain of the whaler ...

''), which was claimed to be . However, there is disagreement as to the accuracy of some of these claims, which are often considered exaggerations or as being measured along the curves of the body.

An individual measuring was reported from a Soviet whaling fleet near the Kuril Islands

The Kuril Islands or Kurile Islands are a volcanic archipelago administered as part of Sakhalin Oblast in the Russian Far East. The islands stretch approximately northeast from Hokkaido in Japan to Kamchatka Peninsula in Russia, separating the ...

in 1950 and is cited by some authors as the largest accurately measured. It has been estimated to weigh . In a review of size variation in marine megafauna, McClain and colleagues noted that the International Whaling Commission's data contained eight individuals larger than . The authors supported a male from the South Pacific in 1933 as the largest recorded. However, sizes like these are rare, with 95% of recorded sperm whales below 15.85 metres (52.0 ft).

In 1853, one sperm whale was reported at in length, with a head measuring . Large lower jawbones are held in the British Natural History Museum

A natural history museum or museum of natural history is a scientific institution with natural history scientific collection, collections that include current and historical records of animals, plants, Fungus, fungi, ecosystems, geology, paleo ...

and the Oxford University Museum of Natural History

The Oxford University Museum of Natural History (OUMNH) is a museum displaying many of the University of Oxford's natural history specimens, located on Parks Road in Oxford, England. It also contains a lecture theatre which is used by the univers ...

, measuring and , respectively.

The average size of sperm whales has decreased over the years, probably due to pressure from whaling. Another view holds that exploitation by overwhaling had virtually no effect on the size of the bull sperm whales, and their size may have actually increased in current times on the basis of density dependent effects. Old males taken at Solander Islands were recorded to be extremely large and unusually rich in blubbers.

The sperm whale's unique body is unlikely to be confused with any other species. The sperm whale's distinctive shape comes from its very large, block-shaped head, which can be one-quarter to one-third of the animal's length. The S-shaped blowhole is located very close to the front of the head and shifted to the whale's left. This gives rise to a distinctive bushy, forward-angled spray.

The sperm whale's flukes (tail lobes) are triangular and very thick. Proportionally, they are larger than that of any other cetacean, and are very flexible. The whale lifts its flukes high out of the water as it begins a feeding dive. It has a series of ridges on the back's caudal third instead of a

The sperm whale's unique body is unlikely to be confused with any other species. The sperm whale's distinctive shape comes from its very large, block-shaped head, which can be one-quarter to one-third of the animal's length. The S-shaped blowhole is located very close to the front of the head and shifted to the whale's left. This gives rise to a distinctive bushy, forward-angled spray.

The sperm whale's flukes (tail lobes) are triangular and very thick. Proportionally, they are larger than that of any other cetacean, and are very flexible. The whale lifts its flukes high out of the water as it begins a feeding dive. It has a series of ridges on the back's caudal third instead of a dorsal fin

A dorsal fin is a fin on the back of most marine and freshwater vertebrates. Dorsal fins have evolved independently several times through convergent evolution adapting to marine environments, so the fins are not all homologous. They are found ...

. The largest ridge was called the 'hump' by whalers, and can be mistaken for a dorsal fin because of its shape and size.

In contrast to the smooth skin of most large whales, its back skin is usually wrinkly and has been likened to a prune

A prune is a dried plum, most commonly from the European plum (''Prunus domestica'') tree. Not all plum species or varieties can be dried into prunes. Use of the term ''prune'' for fresh plums is obsolete except when applied to varieties of ...

by whale-watching enthusiasts. Albino

Albinism is the congenital absence of melanin in an animal or plant resulting in white hair, feathers, scales and skin and reddish pink or blue eyes. Individuals with the condition are referred to as albinos.

Varied use and interpretation of ...

s have been reported.

Skeleton

The ribs are bound to the spine by flexible cartilage, which allows the ribcage to collapse rather than snap under high pressure. While sperm whales are well adapted to diving, repeated dives to great depths have long-term effects. Bones show the same avascular necrosis that signals

The ribs are bound to the spine by flexible cartilage, which allows the ribcage to collapse rather than snap under high pressure. While sperm whales are well adapted to diving, repeated dives to great depths have long-term effects. Bones show the same avascular necrosis that signals decompression sickness

Decompression sickness (DCS; also called divers' disease, the bends, aerobullosis, and caisson disease) is a medical condition caused by dissolved gases emerging from Solution (chemistry), solution as bubbles inside the body tissues during D ...

in humans. Older skeletons showed the most extensive damage, whereas calves showed no damage. This damage may indicate that sperm whales are susceptible to decompression sickness, and sudden surfacing could be lethal to them.

Like that of all cetaceans, the spine of the sperm whale has reduced

Like that of all cetaceans, the spine of the sperm whale has reduced zygapophysial joint

The facet joints (also zygapophysial joints, zygapophyseal, apophyseal, or Z-joints) are a set of synovial, plane joints between the articular processes of two adjacent vertebrae. There are two facet joints in each spinal motion segment and ...

s, of which the remnants are modified and are positioned higher on the vertebral dorsal spinous process, hugging it laterally, to prevent extensive lateral bending and facilitate more dorso-ventral bending. These evolutionary modifications make the spine more flexible but weaker than the spines of terrestrial vertebrates.

Like many cetaceans, the sperm whale has a vestigial pelvis that is not connected to the spine.

Like that of other

Like many cetaceans, the sperm whale has a vestigial pelvis that is not connected to the spine.

Like that of other toothed whale

The toothed whales (also called odontocetes, systematic name Odontoceti) are a parvorder of cetaceans that includes dolphins, porpoises, and all other whales with teeth, such as beaked whales and the sperm whales. 73 species of toothed wha ...

s, the skull of the sperm whale is asymmetrical so as to aid echolocation. Sound waves that strike the whale from different directions will not be channeled in the same way. Within the basin of the cranium, the openings of the bony narial tubes (from which the nasal passages spring) are skewed towards the left side of the skull.

Jaws and teeth

The sperm whale's lower jaw is very narrow and underslung. In: The sperm whale has 18 to 26 teeth on each side of its lower jaw which fit into sockets in the upper jaw. The teeth are cone-shaped and weigh up to each. The teeth are functional, but do not appear to be necessary for capturing or eating squid, as well-fed animals have been found without teeth or even with deformed jaws. One hypothesis is that the teeth are used in aggression between males. Mature males often show scars which seem to be caused by the teeth. Rudimentary teeth are also present in the upper jaw, but these rarely emerge into the mouth. Analyzing the teeth is the preferred method for determining a whale's age. Like tree rings, the teeth build distinct layers of

The sperm whale's lower jaw is very narrow and underslung. In: The sperm whale has 18 to 26 teeth on each side of its lower jaw which fit into sockets in the upper jaw. The teeth are cone-shaped and weigh up to each. The teeth are functional, but do not appear to be necessary for capturing or eating squid, as well-fed animals have been found without teeth or even with deformed jaws. One hypothesis is that the teeth are used in aggression between males. Mature males often show scars which seem to be caused by the teeth. Rudimentary teeth are also present in the upper jaw, but these rarely emerge into the mouth. Analyzing the teeth is the preferred method for determining a whale's age. Like tree rings, the teeth build distinct layers of cementum

Cementum is a specialized calcified substance covering the root of a tooth. The cementum is the part of the periodontium that attaches the teeth to the alveolar bone by anchoring the periodontal ligament.

Structure

The cells of cementum are ...

and dentine as they grow.

Brain

The sperm whale

The sperm whale brain

The brain is an organ (biology), organ that serves as the center of the nervous system in all vertebrate and most invertebrate animals. It consists of nervous tissue and is typically located in the head (cephalization), usually near organs for ...

is the largest known of any modern or extinct animal, weighing on average about (with the smallest known weighing and the largest known weighing ), more than five times heavier than a human brain

The human brain is the central organ (anatomy), organ of the nervous system, and with the spinal cord, comprises the central nervous system. It consists of the cerebrum, the brainstem and the cerebellum. The brain controls most of the activi ...

, and has a volume of about 8,000 cm3. Although larger brains generally correlate with higher intelligence, it is not the only factor. Elephants and dolphins also have larger brains than humans. The sperm whale has a lower encephalization quotient

Encephalization quotient (EQ), encephalization level (EL), or just encephalization is a relative brain size measure that is defined as the ratio between observed and predicted brain mass for an animal of a given size, based on nonlinear regre ...

than many other whale and dolphin

A dolphin is an aquatic mammal in the cetacean clade Odontoceti (toothed whale). Dolphins belong to the families Delphinidae (the oceanic dolphins), Platanistidae (the Indian river dolphins), Iniidae (the New World river dolphins), Pontopori ...

species, lower than that of non-human anthropoid apes, and much lower than that of humans.

The sperm whale's cerebrum

The cerebrum (: cerebra), telencephalon or endbrain is the largest part of the brain, containing the cerebral cortex (of the two cerebral hemispheres) as well as several subcortical structures, including the hippocampus, basal ganglia, and olfac ...

is the largest in all mammalia, both in absolute and relative terms. The olfactory system

The olfactory system, is the sensory nervous system, sensory system used for the sense of smell (olfaction). Olfaction is one of the special senses directly associated with specific organs. Most mammals and reptiles have a main olfactory system ...

is reduced, suggesting that the sperm whale has a poor sense of taste and smell. By contrast, the auditory system is enlarged. The pyramidal tract

The pyramidal tracts include both the corticobulbar tract and the corticospinal tract. These are aggregations of efferent nerve fibers from the upper motor neurons that travel from the cerebral cortex and terminate either in the brainstem (''cort ...

is poorly developed, reflecting the reduction of its limbs.

Biological systems

The sperm whale respiratory system has adapted to cope with drastic pressure changes when diving. The flexible ribcage allows lung collapse, reducingnitrogen

Nitrogen is a chemical element; it has Symbol (chemistry), symbol N and atomic number 7. Nitrogen is a Nonmetal (chemistry), nonmetal and the lightest member of pnictogen, group 15 of the periodic table, often called the Pnictogen, pnictogens. ...

intake, and metabolism

Metabolism (, from ''metabolē'', "change") is the set of life-sustaining chemical reactions in organisms. The three main functions of metabolism are: the conversion of the energy in food to energy available to run cellular processes; the co ...

can decrease to conserve oxygen

Oxygen is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol, symbol O and atomic number 8. It is a member of the chalcogen group (periodic table), group in the periodic table, a highly reactivity (chemistry), reactive nonmetal (chemistry), non ...

. Between dives, the sperm whale surfaces to breathe for about eight minutes before diving again. Odontoceti

The toothed whales (also called odontocetes, systematic name Odontoceti) are a parvorder of cetaceans that includes dolphins, porpoises, and all other whales with teeth, such as beaked whales and the sperm whales. 73 species of toothed whales ar ...

(toothed whales) breathe air at the surface through a single, S-shaped blowhole, which is extremely skewed to the left. Sperm whales spout (breathe) 3–5 times per minute at rest, increasing to 6–7 times per minute after a dive. The blow is a noisy, single stream that rises up to or more above the surface and points forward and left at a 45° angle. On average, females and juveniles blow every 12.5 seconds before dives, while large males blow every 17.5 seconds before dives. A sperm whale killed south of Durban, South Africa, after a 1-hour, 50-minute dive was found with two dogfish ('' Scymnodon'' sp.), usually found at the sea floor

The seabed (also known as the seafloor, sea floor, ocean floor, and ocean bottom) is the bottom of the ocean. All floors of the ocean are known as seabeds.

The structure of the seabed of the global ocean is governed by plate tectonics. Most of ...

, in its belly.

The sperm whale has the longest intestinal system in the world, exceeding 300 m in larger specimens. The sperm whale has a four-chambered stomach that is similar to ruminant

Ruminants are herbivorous grazing or browsing artiodactyls belonging to the suborder Ruminantia that are able to acquire nutrients from plant-based food by fermenting it in a specialized stomach prior to digestion, principally through microb ...

s. The first secretes no gastric juices and has very thick muscular walls to crush the food (since whales cannot chew) and resist the claw and sucker attacks of swallowed squid. The second chamber is larger and is where digestion takes place. Undigested squid beaks accumulate in the second chamber – as many as 18,000 have been found in some dissected specimens.Archived aGhostarchive

and th

Wayback Machine

Most squid beaks are vomited by the whale, but some occasionally make it to the hindgut. Such beaks precipitate the formation of

ambergris

Ambergris ( or ; ; ), ''ambergrease'', or grey amber is a solid, waxy, flammable substance of a dull grey or blackish colour produced in the digestive system of sperm whales. Freshly produced ambergris has a marine, fecal odor. It acquires a sw ...

.

aortic arch

The aortic arch, arch of the aorta, or transverse aortic arch () is the part of the aorta between the ascending and descending aorta. The arch travels backward, so that it ultimately runs to the left of the trachea.

Structure

The aorta begins ...

increases as it leaves the heart. This bulbous expansion acts as a windkessel, ensuring a steady blood flow as the heart rate slows during diving. The arteries that leave the aortic arch are positioned symmetrically. There is no costocervical artery. There is no direct connection between the internal carotid artery and the vessels of the brain. Their circulatory system has adapted to dive at great depths, as much as for up to 120 minutes. More typical dives are around and 35 minutes in duration. Myoglobin

Myoglobin (symbol Mb or MB) is an iron- and oxygen-binding protein found in the cardiac and skeletal muscle, skeletal Muscle, muscle tissue of vertebrates in general and in almost all mammals. Myoglobin is distantly related to hemoglobin. Compar ...

, which stores oxygen in muscle tissue, is much more abundant than in terrestrial animals. The blood

Blood is a body fluid in the circulatory system of humans and other vertebrates that delivers necessary substances such as nutrients and oxygen to the cells, and transports metabolic waste products away from those same cells.

Blood is com ...

has a high density of red blood cell

Red blood cells (RBCs), referred to as erythrocytes (, with -''cyte'' translated as 'cell' in modern usage) in academia and medical publishing, also known as red cells, erythroid cells, and rarely haematids, are the most common type of blood cel ...

s, which contain oxygen-carrying haemoglobin

Hemoglobin (haemoglobin, Hb or Hgb) is a protein containing iron that facilitates the transportation of oxygen in red blood cells. Almost all vertebrates contain hemoglobin, with the sole exception of the fish family Channichthyidae. Hemoglobi ...

. The oxygenated blood can be directed towards only the brain and other essential organs when oxygen levels deplete. The spermaceti organ

The spermaceti organ is an organ present in the heads of toothed whales of the superfamily Physeteroidea, in particular the sperm whale. The organ contains a waxy liquid called spermaceti and is thought to be involved in the generation of sound ...

may also play a role by adjusting buoyancy

Buoyancy (), or upthrust, is the force exerted by a fluid opposing the weight of a partially or fully immersed object (which may be also be a parcel of fluid). In a column of fluid, pressure increases with depth as a result of the weight of t ...

(see below

Below may refer to:

*Earth

*Ground (disambiguation)

*Soil

*Floor

* Bottom (disambiguation)

*Less than

*Temperatures below freezing

*Hell or underworld

People with the surname

* Ernst von Below (1863–1955), German World War I general

* Fred Belo ...

). The arterial retia mirabilia are more extensive and larger than those of any other cetacean.

Senses

Spermaceti organ and melon

Atop the whale's skull is positioned a large complex of organs filled with a liquid mixture of fats and waxes calledspermaceti

Spermaceti (see also: Sperm oil) is a waxy substance found in the head cavities of the sperm whale (and, in smaller quantities, in the oils of other whales). Spermaceti is created in the spermaceti organ inside the whale's head. This organ may ...

. The purpose of this complex is to generate powerful and focused clicking sounds, the existence of which was proven by Valentine Worthington and William Schevill when a recording was produced on a research vessel in May 1959. The sperm whale uses these sounds for echolocation and communication.

The spermaceti organ is like a large barrel of spermaceti. Its surrounding wall, known as the ''case'', is extremely tough and fibrous. The case can hold within it up to 1,900 litre

The litre ( Commonwealth spelling) or liter ( American spelling) (SI symbols L and l, other symbol used: ℓ) is a metric unit of volume. It is equal to 1 cubic decimetre (dm3), 1000 cubic centimetres (cm3) or 0.001 cubic metres (m3). A ...

s of spermaceti. It is proportionately larger in males. This oil is a mixture of triglyceride

A triglyceride (from '' tri-'' and '' glyceride''; also TG, triacylglycerol, TAG, or triacylglyceride) is an ester derived from glycerol and three fatty acids.

Triglycerides are the main constituents of body fat in humans and other vertebrates ...

s and wax ester

A wax ester (WE) is an ester of a fatty acid and a fatty alcohol. Wax esters are the main components of three commercially important waxes: carnauba wax, candelilla wax, and beeswax..

Wax esters are formed by combining one fatty acid with one ...

s. It has been suggested that it is homologous to the dorsal bursa organ found in dolphins. The proportion of wax esters in the spermaceti organ increases with the age of the whale: 38–51% in calves, 58–87% in adult females, and 71–94% in adult males. The spermaceti at the core of the organ has a higher wax content than the outer areas. The speed of sound in spermaceti is 2,684 m/s (at 40 kHz, 36 °C), making it nearly twice as fast as in the oil in a dolphin's melon

A melon is any of various plants of the family Cucurbitaceae with sweet, edible, and fleshy fruit. It can also specifically refer to ''Cucumis melo'', commonly known as the "true melon" or simply "melon". The term "melon" can apply to both the p ...

.

Below the spermaceti organ lies the "junk" which consists of compartments of spermaceti separated by cartilage. It is analogous to the melon

A melon is any of various plants of the family Cucurbitaceae with sweet, edible, and fleshy fruit. It can also specifically refer to ''Cucumis melo'', commonly known as the "true melon" or simply "melon". The term "melon" can apply to both the p ...

found in other toothed whales. The structure of the junk redistributes physical stress across the skull and may have evolved to protect the head during ramming.

Running through the head are two air passages. The left passage runs alongside the spermaceti organ and goes directly to the blowhole, whilst the right passage runs underneath the spermaceti organ and passes air through a pair of phonic lips and into the distal sac at the very front of the nose. The distal sac is connected to the blowhole and the terminus of the left passage. When the whale is submerged, it can close the blowhole, and air that passes through the phonic lips can circulate back to the lungs. The sperm whale, unlike other odontocetes, has only one pair of phonic lips, whereas all other toothed whales have two, and it is located at the front of the nose instead of behind the melon.

At the posterior end of this spermaceti complex is the frontal sac, which covers the concave surface of the cranium. The posterior wall of the frontal sac is covered with fluid-filled knobs, which are about 4–13 mm in diameter and separated by narrow grooves. The anterior wall is smooth. The knobbly surface reflects sound waves that come through the spermaceti organ from the phonic lips. The grooves between the knobs trap a film of air that is consistent whatever the orientation or depth of the whale, making it an excellent sound mirror.

The spermaceti organs may also help adjust the whale's buoyancy

Buoyancy (), or upthrust, is the force exerted by a fluid opposing the weight of a partially or fully immersed object (which may be also be a parcel of fluid). In a column of fluid, pressure increases with depth as a result of the weight of t ...

. It is hypothesized that before the whale dives, cold water enters the organ, and it is likely that the blood vessels constrict, reducing blood flow, and, hence, temperature. The wax therefore solidifies and reduces in volume. The increase in specific density

Relative density, also called specific gravity, is a dimensionless quantity defined as the ratio of the density (mass of a unit volume) of a substance to the density of a given reference material. Specific gravity for solids and liquids is nea ...

generates a down force of about and allows the whale to dive with less effort. During the hunt, oxygen consumption, together with blood vessel dilation, produces heat and melts the spermaceti, increasing its buoyancy and enabling easy surfacing. However, more recent work has found many problems with this theory including the lack of anatomical structures for the actual heat exchange. Another issue is that if the spermaceti does indeed cool and solidify, it would affect the whale's echolocation ability just when it needs it to hunt in the depths.

Herman Melville

Herman Melville (Name change, born Melvill; August 1, 1819 – September 28, 1891) was an American novelist, short story writer, and poet of the American Renaissance (literature), American Renaissance period. Among his best-known works ar ...

's fictional story ''Moby-Dick

''Moby-Dick; or, The Whale'' is an 1851 Epic (genre), epic novel by American writer Herman Melville. The book is centered on the sailor Ishmael (Moby-Dick), Ishmael's narrative of the maniacal quest of Captain Ahab, Ahab, captain of the whaler ...

'' suggests that the "case" containing the spermaceti serves as a battering ram for use in fights between males. A few famous instances include the well-documented sinking of the ships ''Essex

Essex ( ) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in the East of England, and one of the home counties. It is bordered by Cambridgeshire and Suffolk to the north, the North Sea to the east, Kent across the Thames Estuary to the ...

'' and '' Ann Alexander'' by attackers estimated to weigh only one-fifth as much as the ships.

Eyes and vision

The sperm whale's eye does not differ greatly from those of othertoothed whale

The toothed whales (also called odontocetes, systematic name Odontoceti) are a parvorder of cetaceans that includes dolphins, porpoises, and all other whales with teeth, such as beaked whales and the sperm whales. 73 species of toothed wha ...

s except in size. It is the largest among the toothed whales, weighing about 170 g. It is overall ellipsoid in shape, compressed along the visual axis, measuring about 7×7×3 cm. The cornea

The cornea is the transparency (optics), transparent front part of the eyeball which covers the Iris (anatomy), iris, pupil, and Anterior chamber of eyeball, anterior chamber. Along with the anterior chamber and Lens (anatomy), lens, the cornea ...

is elliptical and the lens is spherical. The sclera

The sclera, also known as the white of the eye or, in older literature, as the tunica albuginea oculi, is the opaque, fibrous, protective outer layer of the eye containing mainly collagen and some crucial elastic fiber.

In the development of t ...

is very hard and thick, roughly 1 cm anteriorly and 3 cm posteriorly. There are no ciliary muscle

The ciliary muscle is an intrinsic muscle of the eye formed as a ring of smooth muscleSchachar, Ronald A. (2012). "Anatomy and Physiology." (Chapter 4) . in the eye's middle layer, the uvea ( vascular layer). It controls accommodation for vie ...

s. The choroid

The choroid, also known as the choroidea or choroid coat, is a part of the uvea, the vascular layer of the eye. It contains connective tissues, and lies between the retina and the sclera. The human choroid is thickest at the far extreme rear o ...

is very thick and contains a fibrous ''tapetum lucidum

The ; ; : tapeta lucida) is a layer of tissue in the eye of many vertebrates and some other animals. Lying immediately behind the retina, it is a retroreflector. It Reflection (physics), reflects visible light back through the retina, increas ...

''. Like other toothed whales, the sperm whale can retract and protrude its eyes, thanks to a 2-cm-thick retractor muscle attached around the eye at the equator, but are unable to roll the eyes in their sockets.

According to Fristrup and Harbison (2002),

sperm whale's eyes afford good vision and sensitivity to light. They conjectured that sperm whales use vision to hunt squid, either by detecting silhouettes from below or by detecting bioluminescence. If sperm whales detect silhouettes, Fristrup and Harbison suggested that they hunt upside down, allowing them to use the forward parts of the ventral visual field

The visual field is "that portion of space in which objects are visible at the same moment during steady fixation of the gaze in one direction"; in ophthalmology and neurology the emphasis is mostly on the structure inside the visual field and it i ...

s for binocular vision Binocular vision is seeing with two eyes. The Field_of_view, field of view that can be surveyed with two eyes is greater than with one eye. To the extent that the visual fields of the two eyes overlap, #Depth, binocular depth can be perceived. Th ...

.

Sleeping

For some time researchers have been aware that pods of sperm whales may sleep for short periods, assuming a vertical position with their heads just below or at the surface, or head down. A 2008 study published in ''Current Biology

''Current Biology'' is a biweekly peer-reviewed scientific journal that covers all areas of biology, especially molecular biology, cell biology, genetics, neurobiology, ecology, and evolutionary biology. The journal includes research artic ...

'' recorded evidence that whales may sleep with both sides of the brain. It appears that some whales may fall into a deep sleep for about 7 percent of the time, most often between 6 p.m. and midnight.

Genetics

Sperm whales have 21 pairs of chromosomes ( 2n=42). The genome of live whales can be examined by recovering shed skin.Vocalization complex

After Valentine Worthington and William E. Schevill confirmed the existence of sperm whale vocalization, further studies found that sperm whales are capable of emitting sounds at a source level of 230decibel

The decibel (symbol: dB) is a relative unit of measurement equal to one tenth of a bel (B). It expresses the ratio of two values of a Power, root-power, and field quantities, power or root-power quantity on a logarithmic scale. Two signals whos ...

s–making the sperm whale the loudest animal in the world.

Mechanism

When echolocating, the sperm whale emits a directionally focused beam of broadband clicks. Clicks are generated by forcing air through a pair of phonic lips (also known as "monkey lips" or "") at the front end of the nose, just below the blowhole. The sound then travels backwards along the length of the nose through the spermaceti organ. Most of the sound energy is then reflected off the frontal sac at the cranium and into the melon, whose lens-like structure focuses it. Some of the sound will reflect back into the spermaceti organ and back towards the front of the whale's nose, where it will be reflected through the spermaceti organ a third time. This back and forth reflection which happens on the scale of a few milliseconds creates a multi-pulse click structure. This multi-pulse click structure allows researchers to measure the whale's spermaceti organ using only the sound of its clicks. Because the interval between pulses of a sperm whale's click is related to the length of the sound producing organ, an individual whale's click is unique to that individual. However, if the whale matures and the size of thespermaceti

Spermaceti (see also: Sperm oil) is a waxy substance found in the head cavities of the sperm whale (and, in smaller quantities, in the oils of other whales). Spermaceti is created in the spermaceti organ inside the whale's head. This organ may ...

organ increases, the tone of the whale's click will also change. The lower jaw is the primary reception path for the echoes. A continuous fat-filled canal transmits received sounds to the inner ear.

The source of the air forced through the phonic lips is the right nasal passage. While the left nasal passage opens to the blow hole, the right nasal passage has evolved to supply air to the phonic lips. It is thought that the nostrils of the land-based ancestor of the sperm whale migrated through evolution to their current functions, the left nostril becoming the blowhole and the right nostril becoming the phonic lips.

Air that passes through the phonic lips passes into the distal sac, then back down through the left nasal passage. This recycling of air allows the whale to continuously generate clicks for as long as it is submerged.

Vocalization types

The sperm whale's vocalizations are all based on clicking, described in four types: the usual echolocation, creaks, codas, and slow clicks. The usual echolocation click type is used in searching for prey. A creak is a rapid series of high-frequency clicks that sounds somewhat like a creaky door hinge. It is typically used when homing in on prey. Slow clicks are heard only in the presence of males (it is not certain whether females occasionally make them). Males make a lot of slow clicks in breeding grounds (74% of the time), both near the surface and at depth, which suggests they are primarily mating signals. Outside breeding grounds, slow clicks are rarely heard, and usually near the surface.Codas

The most distinctive vocalizations are codas, which are short rhythmic sequences of clicks, mostly numbering 3–12 clicks, in stereotyped patterns. They are classified using variations in the number of clicks, rhythm, and tempo. Codas are the result of vocal learning within a stable social group, and are made in the context of the whales' social unit. "The foundation of sperm whale society is the matrilineally based social unit of ten or so females and their offspring. The members of the unit travel together, suckle each others' infants, and babysit them while mothers make long deep dives to feed." Over 70% of a sperm whale's time is spent independently foraging; codas "could help whales reunite and reaffirm their social ties in between long foraging dives". While nonidentity codas are commonly used in multiple different clans, some codas express clan identity, and denote different patterns of travel, foraging, and socializing or avoidance among clans. In particular, whales will not group with whales of another clan even though they share the same geographical area. Statistically, as the clans' ranges become more overlapped, the distinction in clan identity coda usage becomes more pronounced. Distinctive codas identify seven clans described among the approximately 150,000 female sperm whales in the Pacific Ocean, and there are another four clans in the Atlantic. As "arbitrary traits that function as reliable indicators of cultural group membership", clan identity codas act as symbolic markers that modulate interactions between individuals. Individual identity in sperm whale vocalizations is an ongoing scientific issue, however. A distinction needs to be made between cues and signals. Human acoustic tools can distinguish individual whales by analyzing micro-characteristics of their vocalizations, and the whales can probably do the same. This does not prove that the whales deliberately use some vocalizations to signal individual identity in the manner of the signature whistles that bottlenose dolphins use as individual labels.Ecology

Distribution

Sperm whales are among the mostcosmopolitan species

In biogeography, a cosmopolitan distribution is the range of a taxon that extends across most or all of the surface of the Earth, in appropriate habitats; most cosmopolitan species are known to be highly adaptable to a range of climatic and en ...

. They prefer ice-free waters over deep. Although both sexes range through temperate and tropical oceans and seas, only adult males populate higher latitude

In geography, latitude is a geographic coordinate system, geographic coordinate that specifies the north-south position of a point on the surface of the Earth or another celestial body. Latitude is given as an angle that ranges from −90° at t ...

s. Among several regions, such as along coastal waters of southern Australia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a country comprising mainland Australia, the mainland of the Australia (continent), Australian continent, the island of Tasmania and list of islands of Australia, numerous smaller isl ...

, sperm whales have been considered to be locally extinct.

They are relatively abundant from the poles to the equator and are found in all the oceans. They inhabit the Mediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea ( ) is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the east by the Levant in West Asia, on the north by Anatolia in West Asia and Southern Eur ...

, but not the Black Sea

The Black Sea is a marginal sea, marginal Mediterranean sea (oceanography), mediterranean sea lying between Europe and Asia, east of the Balkans, south of the East European Plain, west of the Caucasus, and north of Anatolia. It is bound ...

, while their presence in the Red Sea

The Red Sea is a sea inlet of the Indian Ocean, lying between Africa and Asia. Its connection to the ocean is in the south, through the Bab-el-Mandeb Strait and the Gulf of Aden. To its north lie the Sinai Peninsula, the Gulf of Aqaba, and th ...

is uncertain. The shallow entrances to both the Black Sea and the Red Sea may account for their absence. The Black Sea's lower layers are also anoxic

Anoxia means a total depletion in the level of oxygen, an extreme form of hypoxia or "low oxygen". The terms anoxia and hypoxia are used in various contexts:

* Anoxic waters, sea water, fresh water or groundwater that are depleted of dissolved ox ...

and contain high concentrations of sulphur

Sulfur (American spelling and the preferred IUPAC name) or sulphur (English in the Commonwealth of Nations, Commonwealth spelling) is a chemical element; it has Symbol (chemistry), symbol S and atomic number 16. It is abundance of the chemical ...

compounds such as hydrogen sulphide

Hydrogen sulfide is a chemical compound with the formula . It is a colorless chalcogen-hydride gas, and is toxic, corrosive, and flammable. Trace amounts in ambient atmosphere have a characteristic foul odor of rotten eggs. Swedish chemist Ca ...

. The first ever sighting off the coast of Pakistan

Pakistan, officially the Islamic Republic of Pakistan, is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by population, fifth-most populous country, with a population of over 241.5 million, having the Islam by country# ...

was made in 2017. The first ever record off the west coast of the Korean Peninsula (Yellow Sea

The Yellow Sea, also known as the North Sea, is a marginal sea of the Western Pacific Ocean located between mainland China and the Korean Peninsula, and can be considered the northwestern part of the East China Sea.

Names

It is one of four ...

) was made in 2005. followed by one near Ganghwa Island

Ganghwa Island (), also Ganghwado, is an island in Ganghwa County, Incheon, South Korea. It is in the Yellow Sea and in an estuary of the Han River.

The island is separated from Gimpo (on the South Korean mainland) by a narrow channel spanned ...

in 2009.

Populations are denser close to continental shelves

A continental shelf is a portion of a continent that is submerged under an area of relatively shallow water, known as a shelf sea. Much of these shelves were exposed by drops in sea level during glacial periods. The shelf surrounding an island ...

and canyons. Sperm whales are usually found in deep, off-shore waters, but may be seen closer to shore, in areas where the continental shelf is small and drops quickly to depths of . Coastal areas with significant sperm whale populations include the Azores

The Azores ( , , ; , ), officially the Autonomous Region of the Azores (), is one of the two autonomous regions of Portugal (along with Madeira). It is an archipelago composed of nine volcanic islands in the Macaronesia region of the North Atl ...

and Dominica

Dominica, officially the Commonwealth of Dominica, is an island country in the Caribbean. It is part of the Windward Islands chain in the Lesser Antilles archipelago in the Caribbean Sea. The capital, Roseau, is located on the western side of t ...

. In east Asian waters, whales are also observed regularly in coastal waters in places such as the Commander

Commander (commonly abbreviated as Cmdr.) is a common naval officer rank as well as a job title in many army, armies. Commander is also used as a rank or title in other formal organizations, including several police forces. In several countri ...

and Kuril Islands

The Kuril Islands or Kurile Islands are a volcanic archipelago administered as part of Sakhalin Oblast in the Russian Far East. The islands stretch approximately northeast from Hokkaido in Japan to Kamchatka Peninsula in Russia, separating the ...

, Shiretoko Peninsula which is one of few locations where sperm whales can be observed from shores, off Kinkasan, vicinity to Tokyo Bay

is a bay located in the southern Kantō region of Japan spanning the coasts of Tokyo, Kanagawa Prefecture, and Chiba Prefecture, on the southern coast of the island of Honshu. Tokyo Bay is connected to the Pacific Ocean by the Uraga Channel. Th ...

and the Bōsō Peninsula to the Izu and the Izu Islands

The are a group of volcanic islands stretching south and east from the Izu Peninsula of Honshū, Japan. Administratively, they form two towns and six villages; all part of Tokyo Prefecture. The largest is Izu Ōshima, usually called simply Ōsh ...

, the Volcano Islands

The or are a group of three Japanese-governed islands in Micronesia. They lie south of the Ogasawara Islands and belong to the municipality of Ogasawara, Tokyo, Tokyo Metropolis, Japan. The islands are all active volcanoes lying ato ...

, Yakushima

is one of the Ōsumi Islands in Kagoshima Prefecture, Japan. The island, in area, has a population of 13,178. It is accessible by hydrofoil ferry, car ferry, or by air to Yakushima Airport.

Administratively, the island consists of the town ...

and the Tokara Islands

The is an archipelago in the Nansei Islands, and are part of the Satsunan Islands, which is in turn part of the Ryukyu Archipelago. The chain consists of twelve small islands located between Yakushima and Amami-Oshima. The islands have a total ...

to the Ryukyu Islands

The , also known as the or the , are a chain of Japanese islands that stretch southwest from Kyushu to Geography of Taiwan, Taiwan: the Ryukyu Islands are divided into the Satsunan Islands (Ōsumi Islands, Ōsumi, Tokara Islands, Tokara and A ...

, Taiwan

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is a country in East Asia. The main geography of Taiwan, island of Taiwan, also known as ''Formosa'', lies between the East China Sea, East and South China Seas in the northwestern Pacific Ocea ...

, the Northern Mariana Islands

The Northern Mariana Islands, officially the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands (CNMI), is an Territories of the United States, unincorporated territory and Commonwealth (U.S. insular area), commonwealth of the United States consistin ...

, and so forth. Historical catch records suggest there could have been smaller aggression grounds in the Sea of Japan

The Sea of Japan is the marginal sea between the Japanese archipelago, Sakhalin, the Korean Peninsula, and the mainland of the Russian Far East. The Japanese archipelago separates the sea from the Pacific Ocean. Like the Mediterranean Sea, it ...

as well. Along the Korean Peninsula

Korea is a peninsular region in East Asia consisting of the Korean Peninsula, Jeju Island, and smaller islands. Since the end of World War II in 1945, it has been politically divided at or near the 38th parallel between North Korea (Dem ...

, the first confirmed observation within the Sea of Japan, eight animals off Guryongpo, was made in 2004 since after the last catches of five whales off Ulsan

Ulsan (; ), officially the Ulsan Metropolitan City, is South Korea's seventh-largest metropolitan city and the eighth-largest city overall, with a population of over 1.1 million inhabitants. It is located in the south-east of the country, neighbo ...

in 1911, while nine whales were observed in the East China Sea side of the peninsula in 1999.

Grown males are known to enter surprisingly shallow bays to rest (whales will be in a state of rest during these occasions). Unique, coastal groups have been reported from various areas around the globe, such as near Scotland

Scotland is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It contains nearly one-third of the United Kingdom's land area, consisting of the northern part of the island of Great Britain and more than 790 adjac ...

's coastal waters, and the Shiretoko Peninsula, off Kaikōura, in Davao Gulf. Such coastal groups were more abundant in pre-whaling days.

Genetic analysis indicates that the world population of sperm whales originated in the Pacific Ocean from a population of about 10,000 animals around 100,000 years ago, when expanding ice caps blocked off their access to other seas. In particular, colonization of the Atlantic was revealed to have occurred multiple times during this expansion of their range.

Diet

octopus

An octopus (: octopuses or octopodes) is a soft-bodied, eight-limbed mollusc of the order Octopoda (, ). The order consists of some 300 species and is grouped within the class Cephalopoda with squids, cuttlefish, and nautiloids. Like oth ...

es, and fish such as demersal

The demersal zone is the part of the sea or ocean (or deep lake) consisting of the part of the water column near to (and significantly affected by) the seabed and the benthos. The demersal zone is just above the benthic zone and forms a layer o ...

rays and shark

Sharks are a group of elasmobranch cartilaginous fish characterized by a ribless endoskeleton, dermal denticles, five to seven gill slits on each side, and pectoral fins that are not fused to the head. Modern sharks are classified within the ...

s, but their diet is mainly medium-sized squid

A squid (: squid) is a mollusc with an elongated soft body, large eyes, eight cephalopod limb, arms, and two tentacles in the orders Myopsida, Oegopsida, and Bathyteuthida (though many other molluscs within the broader Neocoleoidea are also ...

. Sperm whales may also possibly prey upon swordfish

The swordfish (''Xiphias gladius''), also known as the broadbill in some countries, are large, highly migratory predatory fish characterized by a long, flat, pointed bill. They are the sole member of the Family (biology), family Xiphiidae. They ...

on rare occasions. Some prey may be taken accidentally while eating other items. Most of what is known about deep-sea squid has been learned from specimens in captured sperm whale stomachs, although more recent studies analysed faeces

Feces (also known as faeces American and British English spelling differences#ae and oe, or fæces; : faex) are the solid or semi-solid remains of food that was not digested in the small intestine, and has been broken down by bacteria in the ...

.