Sparkling Water on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Carbonated water is

Carbonated water is

Many

Many  In 1767 Priestley discovered a method of infusing water with carbon dioxide by pouring water back and forth above a beer vat at a local brewery in

In 1767 Priestley discovered a method of infusing water with carbon dioxide by pouring water back and forth above a beer vat at a local brewery in

New York Times. Retrieved 10 January 2015 The air blanketing the fermenting beer—called 'fixed air'—was known to kill mice suspended in it. Priestley found water thus treated had a pleasant taste, and he offered it to friends as a cool, refreshing drink. In 1772, Priestley published a paper titled ''Impregnating Water with Fixed Air'' in which he describes dripping "oil of vitriol" (

The soda siphon, or seltzer bottle—a glass or metal pressure vessel with a release valve and spout for dispensing pressurized soda water—was a common sight in bars and in early- to mid-20th-century homes where it became a symbol of middle-class affluence.

The gas pressure in a siphon drives soda water up through a tube inside the siphon when a valve lever at the top is depressed. Commercial soda siphons came pre-charged with water and gas and were returned to the retailer for exchange when empty. A deposit scheme ensured they were not otherwise thrown away.

Home soda siphons can carbonate flatwater through the use of a small disposable steel bulb containing carbon dioxide. The bulb is pressed into the valve assembly at the top of the siphon, the gas injected, then the bulb withdrawn.

The soda siphon, or seltzer bottle—a glass or metal pressure vessel with a release valve and spout for dispensing pressurized soda water—was a common sight in bars and in early- to mid-20th-century homes where it became a symbol of middle-class affluence.

The gas pressure in a siphon drives soda water up through a tube inside the siphon when a valve lever at the top is depressed. Commercial soda siphons came pre-charged with water and gas and were returned to the retailer for exchange when empty. A deposit scheme ensured they were not otherwise thrown away.

Home soda siphons can carbonate flatwater through the use of a small disposable steel bulb containing carbon dioxide. The bulb is pressed into the valve assembly at the top of the siphon, the gas injected, then the bulb withdrawn.

The gasogene (or gazogene, or seltzogene) is a late

The gasogene (or gazogene, or seltzogene) is a late

In 1872, soft drink maker Hiram Codd of

In 1872, soft drink maker Hiram Codd of

Carbonated water is

Carbonated water is water

Water is an inorganic compound with the chemical formula . It is a transparent, tasteless, odorless, and Color of water, nearly colorless chemical substance. It is the main constituent of Earth's hydrosphere and the fluids of all known liv ...

containing dissolved carbon dioxide

Carbon dioxide is a chemical compound with the chemical formula . It is made up of molecules that each have one carbon atom covalent bond, covalently double bonded to two oxygen atoms. It is found in a gas state at room temperature and at norma ...

gas, either artificially injected under pressure, or occurring due to natural geological processes. Carbonation

Carbonation is the chemical reaction of carbon dioxide to give carbonates, bicarbonates, and carbonic acid. In chemistry, the term is sometimes used in place of carboxylation, which refers to the formation of carboxylic acids.

In inorganic che ...

causes small bubbles to form, giving the water

Water is an inorganic compound with the chemical formula . It is a transparent, tasteless, odorless, and Color of water, nearly colorless chemical substance. It is the main constituent of Earth's hydrosphere and the fluids of all known liv ...

an effervescent quality. Common forms include sparkling natural mineral water

Mineral water is water from a mineral spring that contains various minerals, such as salts and sulfur compounds. It is usually still, but may be sparkling ( carbonated/ effervescent).

Traditionally, mineral waters were used or consumed at t ...

, club soda

Club soda is a form of carbonated water manufactured in North America, commonly used as a drink mixer. Sodium bicarbonate, potassium sulfate, potassium bicarbonate, potassium citrate, or sodium citrate is added to artificially replicate constitu ...

, and commercially produced sparkling water.

Club soda, sparkling mineral water, and some other sparkling waters contain added or dissolved mineral

In geology and mineralogy, a mineral or mineral species is, broadly speaking, a solid substance with a fairly well-defined chemical composition and a specific crystal structure that occurs naturally in pure form.John P. Rafferty, ed. (2011): Mi ...

s such as potassium bicarbonate

Potassium bicarbonate ( IUPAC name: potassium hydrogencarbonate, also known as potassium acid carbonate) is the inorganic compound with the chemical formula KHCO3. It is a white solid.

Production and reactivity

It is manufactured by treating an ...

, sodium bicarbonate

Sodium bicarbonate ( IUPAC name: sodium hydrogencarbonate), commonly known as baking soda or bicarbonate of soda (or simply “bicarb” especially in the UK) is a chemical compound with the formula NaHCO3. It is a salt composed of a sodium cat ...

, sodium citrate Sodium citrate may refer to any of the sodium salts of citric acid (though most commonly the third):

* Monosodium citrate

* Disodium citrate

* Trisodium citrate

The three forms of salt are collectively known by the E number E331.

Applications

...

, or potassium sulfate

Potassium sulfate (US) or potassium sulphate (UK), also called sulphate of potash (SOP), arcanite, or archaically potash of sulfur, is the inorganic compound with formula K2SO4, a white water-soluble solid. It is commonly used in fertilizers, prov ...

. These occur naturally in some mineral waters but are also commonly added artificially to manufactured waters to mimic a natural flavor profile and offset the acidity of introducing carbon dioxide gas giving one a fizzy sensation. Various carbonated waters are sold in bottles and cans, with some also produced on demand by commercial carbonation systems in bars and restaurants, or made at home using a carbon dioxide cartridge.

It is thought that the first person to aerate

Aeration (also called aerification or aeriation) is the process by which air is circulated through, mixed with or dissolved in a liquid or other substances that act as a fluid (such as soil). Aeration processes create additional surface area in t ...

water with carbon dioxide was William Brownrigg

William Brownrigg ( – 6 January 1800) was an English physician and scientist who practised at Whitehaven in Cumberland. While there, Brownrigg carried out experiments that earned him the Copley Medal in 1766 for his work on carbonic acid gas. H ...

in the 1740s. Joseph Priestley

Joseph Priestley (; 24 March 1733 – 6 February 1804) was an English chemist, Unitarian, Natural philosophy, natural philosopher, English Separatist, separatist theologian, Linguist, grammarian, multi-subject educator and Classical libera ...

invented carbonated water, independently and by accident, in 1767 when he discovered a method of infusing water with carbon dioxide after having suspended a bowl of water above a beer vat at a brewery

A brewery or brewing company is a business that makes and sells beer. The place at which beer is commercially made is either called a brewery or a beerhouse, where distinct sets of brewing equipment are called plant. The commercial brewing of b ...

in Leeds, Yorkshire

Leeds is a city in West Yorkshire, England. It is the largest settlement in Yorkshire and the administrative centre of the City of Leeds Metropolitan Borough, which is the second most populous district in the United Kingdom. It is built aro ...

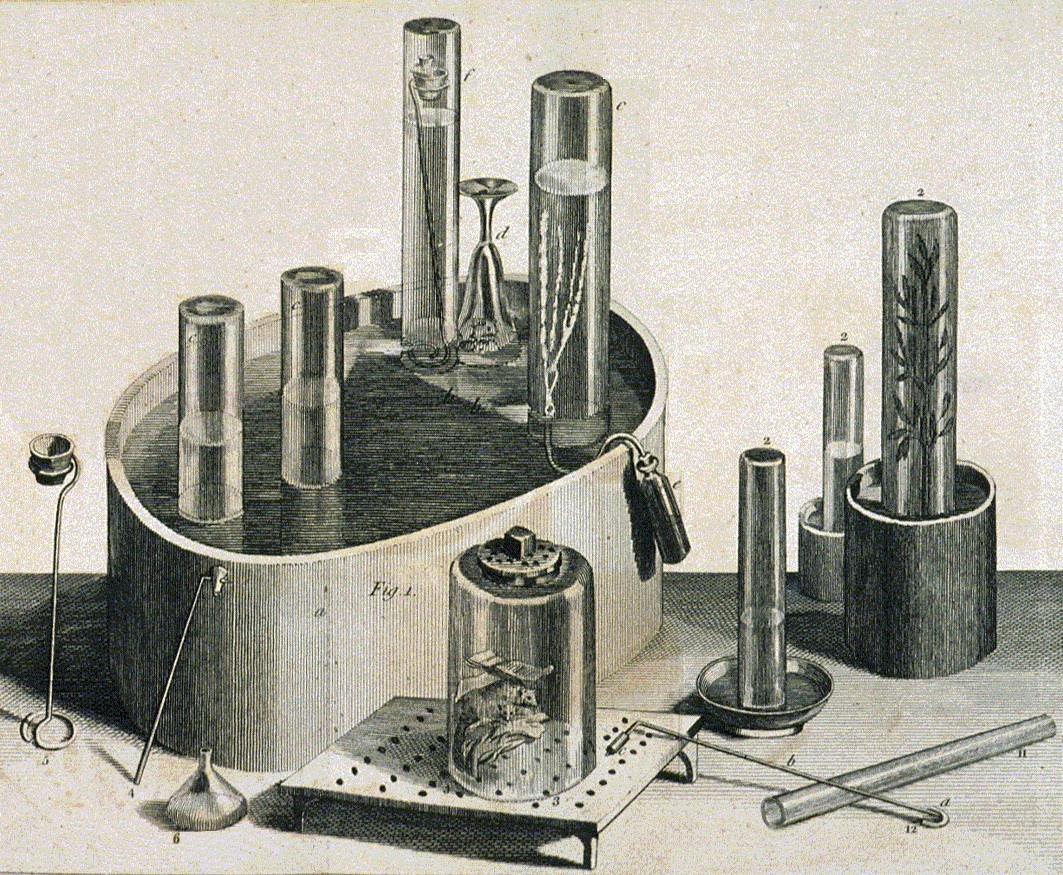

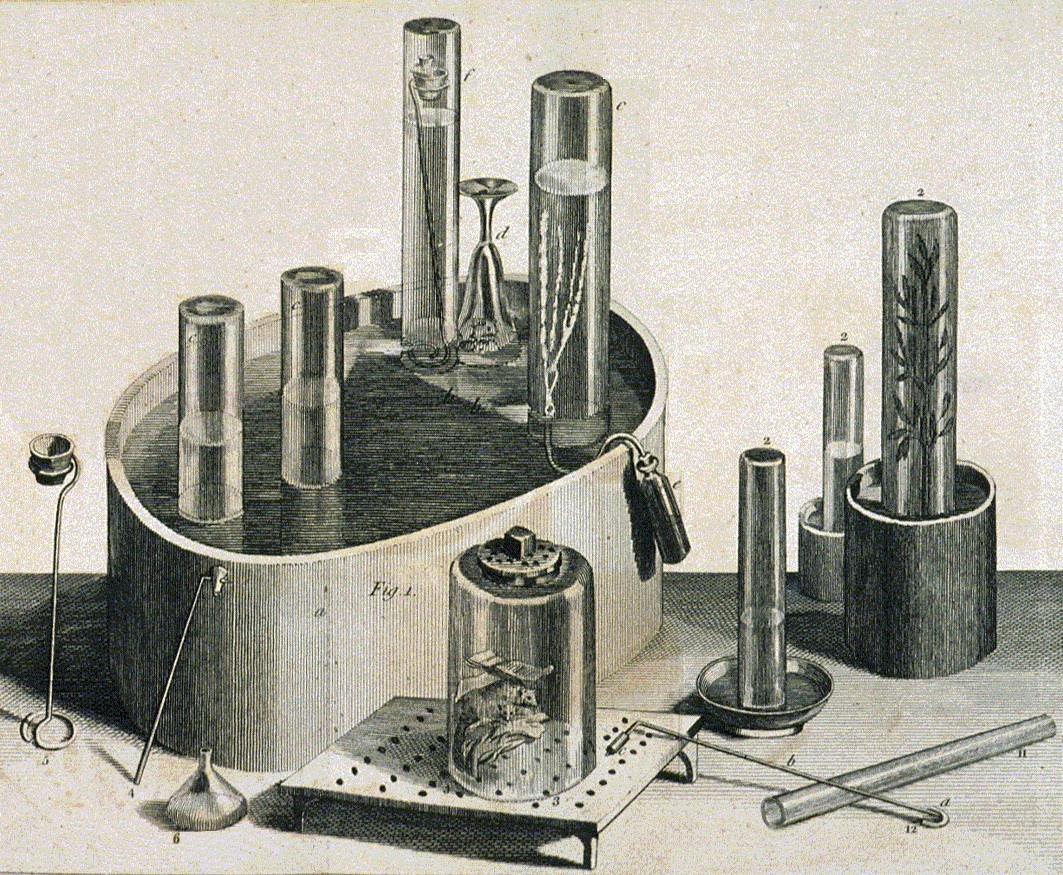

. He wrote of the "peculiar satisfaction" he found in drinking it, and in 1772 he published a paper entitled ''Impregnating Water with Fixed Air''. Priestley's apparatus, almost identical to that used by Henry Cavendish

Henry Cavendish ( ; 10 October 1731 – 24 February 1810) was an English experimental and theoretical chemist and physicist. He is noted for his discovery of hydrogen, which he termed "inflammable air". He described the density of inflammable a ...

five years earlier, which featured a bladder

The bladder () is a hollow organ in humans and other vertebrates that stores urine from the kidneys. In placental mammals, urine enters the bladder via the ureters and exits via the urethra during urination. In humans, the bladder is a distens ...

between the generator and the absorption tank to regulate the flow of carbon dioxide

Carbon dioxide is a chemical compound with the chemical formula . It is made up of molecules that each have one carbon atom covalent bond, covalently double bonded to two oxygen atoms. It is found in a gas state at room temperature and at norma ...

, was soon joined by a wide range of others. However, it was not until 1781 that companies specialized in producing artificial mineral water were established and began producing carbonated water on a large scale. The first factory was built by Thomas Henry of Manchester

Manchester () is a city and the metropolitan borough of Greater Manchester, England. It had an estimated population of in . Greater Manchester is the third-most populous metropolitan area in the United Kingdom, with a population of 2.92&nbs ...

, England. Henry replaced the bladder in Priestley's system with large bellows

A bellows or pair of bellows is a device constructed to furnish a strong blast of air. The simplest type consists of a flexible bag comprising a pair of rigid boards with handles joined by flexible leather sides enclosing an approximately airtig ...

.

While Priestley's discovery ultimately led to the creation of the soft drink

A soft drink (see #Terminology, § Terminology for other names) is a class of non-alcoholic drink, usually (but not necessarily) Carbonated water, carbonated, and typically including added Sweetness, sweetener. Flavors used to be Natural flav ...

industry—which began in 1783 when Johann Jacob Schweppe

Johann Jacob Schweppe ( , ; 16 March 1740 – 18 November 1821) was a German watchmaker and amateur scientist who developed the first practical process to manufacture bottled carbonated mineral water and began selling the world's first bottled so ...

founded Schweppes

Schweppes ( , ) is a soft drink brand founded in the Republic of Geneva in 1783 by the German watchmaker and amateur scientist Johann Jacob Schweppe; it is now made, bottled, and distributed worldwide by multiple international conglomerates, de ...

to sell bottled soda water—he did not benefit financially from his invention. Priestley received scientific recognition when the Council of the Royal Society

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, re ...

"were moved to reward its discoverer with the Copley Medal

The Copley Medal is the most prestigious award of the Royal Society of the United Kingdom, conferred "for sustained, outstanding achievements in any field of science". The award alternates between the physical sciences or mathematics and the bio ...

" at the anniversary meeting of the Royal Society on 30 November 1773.

Composition

Natural and manufactured carbonated waters may contain a small amount ofsodium chloride

Sodium chloride , commonly known as Salt#Edible salt, edible salt, is an ionic compound with the chemical formula NaCl, representing a 1:1 ratio of sodium and chloride ions. It is transparent or translucent, brittle, hygroscopic, and occurs a ...

, sodium citrate Sodium citrate may refer to any of the sodium salts of citric acid (though most commonly the third):

* Monosodium citrate

* Disodium citrate

* Trisodium citrate

The three forms of salt are collectively known by the E number E331.

Applications

...

, sodium bicarbonate

Sodium bicarbonate ( IUPAC name: sodium hydrogencarbonate), commonly known as baking soda or bicarbonate of soda (or simply “bicarb” especially in the UK) is a chemical compound with the formula NaHCO3. It is a salt composed of a sodium cat ...

, potassium bicarbonate

Potassium bicarbonate ( IUPAC name: potassium hydrogencarbonate, also known as potassium acid carbonate) is the inorganic compound with the chemical formula KHCO3. It is a white solid.

Production and reactivity

It is manufactured by treating an ...

, potassium citrate

Potassium citrate (also known as tripotassium citrate) is a potassium salt of citric acid with the molecular formula K3C6H5O7. It is a white, hygroscopic crystalline powder. It is odorless with a saline taste. It contains 38.28% potassium by mass ...

, potassium sulfate

Potassium sulfate (US) or potassium sulphate (UK), also called sulphate of potash (SOP), arcanite, or archaically potash of sulfur, is the inorganic compound with formula K2SO4, a white water-soluble solid. It is commonly used in fertilizers, prov ...

, or disodium phosphate

Disodium phosphate (DSP), or disodium hydrogen phosphate, or sodium phosphate dibasic, is an inorganic compound with the chemical formula . It is one of several sodium phosphates. The salt is known in anhydrous form as well as hydrates , where ...

, depending on the product. These occur naturally in mineral water

Mineral water is water from a mineral spring that contains various minerals, such as salts and sulfur compounds. It is usually still, but may be sparkling ( carbonated/ effervescent).

Traditionally, mineral waters were used or consumed at t ...

s but are added artificially to commercially produced waters to mimic a natural flavor profile and offset the acidity of introducing carbon dioxide gas (which creates low 5–6 pH carbonic acid

Carbonic acid is a chemical compound with the chemical formula . The molecule rapidly converts to water and carbon dioxide in the presence of water. However, in the absence of water, it is quite stable at room temperature. The interconversion ...

solution when dissolved in water).

Artesian well

An artesian well is a well that brings groundwater to the surface without pumping because it is under pressure within a body of rock or sediment known as an aquifer. When trapped water in an aquifer is surrounded by layers of Permeability (ea ...

s in such places as Mihalkovo in the Bulgarian Rhodope Mountains

The Rhodopes (; , ; , ''Rodopi''; ) are a mountain range in Southeastern Europe, and the largest by area in Bulgaria, with over 83% of its area in the southern part of the country and the remainder in Greece. Golyam Perelik is its highest peak ...

, Medžitlija

Medžitlija (, ) is a village in the Municipalities of North Macedonia, municipality of Bitola Municipality, Bitola, North Macedonia, along the border with Greece. It was previously part of the former municipality of Bistrica, Bitola, Bistrica. The ...

in North Macedonia

North Macedonia, officially the Republic of North Macedonia, is a landlocked country in Southeast Europe. It shares land borders with Greece to the south, Albania to the west, Bulgaria to the east, Kosovo to the northwest and Serbia to the n ...

, and most notably in Selters in the German Taunus

The Taunus () is a mountain range in Hesse and Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany, located north west of Frankfurt and north of Wiesbaden. The tallest peak in the range is '' Großer Feldberg'' at 878 m; other notable peaks are '' Kleiner Feldberg' ...

mountains, produce naturally effervescent mineral waters.

Health effects

By itself, carbonated water appears to have little to no impact on health. Carbonated water, such as club soda or sparkling water, is defined in US law as a food ofminimal nutritional value

Minimal may refer to:

* Minimal (music genre), art music that employs limited or minimal musical materials

* Minimal (song), "Minimal" (song), 2006 song by Pet Shop Boys

* Minimal (supermarket) or miniMAL, a former supermarket chain in Germany and ...

, even if minerals, vitamin

Vitamins are Organic compound, organic molecules (or a set of closely related molecules called vitamer, vitamers) that are essential to an organism in small quantities for proper metabolism, metabolic function. Nutrient#Essential nutrients, ...

s, or artificial sweeteners

A sugar substitute or artificial sweetener, is a food additive that provides a sweetness like that of sugar while containing significantly less food energy than sugar-based sweeteners, making it a zero-calorie () or low-calorie sweetener. Arti ...

have been added to it.

Carbonated water does not appear to have an effect on gastroesophageal reflux disease

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) or gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD) is a chronic upper gastrointestinal disease in which stomach content persistently and regularly flows up into the esophagus, resulting in symptoms and/or ...

. There is tentative evidence that carbonated water may help with constipation

Constipation is a bowel dysfunction that makes bowel movements infrequent or hard to pass. The Human feces, stool is often hard and dry. Other symptoms may include abdominal pain, bloating, and feeling as if one has not completely passed the ...

among people who have had a stroke

Stroke is a medical condition in which poor cerebral circulation, blood flow to a part of the brain causes cell death. There are two main types of stroke: brain ischemia, ischemic, due to lack of blood flow, and intracranial hemorrhage, hemor ...

.

Acid erosion

While carbonated water is somewhat acidic, this acidity can be partially neutralized bysaliva

Saliva (commonly referred as spit or drool) is an extracellular fluid produced and secreted by salivary glands in the mouth. In humans, saliva is around 99% water, plus electrolytes, mucus, white blood cells, epithelial cells (from which ...

. A study found that sparkling mineral water

Mineral water is water from a mineral spring that contains various minerals, such as salts and sulfur compounds. It is usually still, but may be sparkling ( carbonated/ effervescent).

Traditionally, mineral waters were used or consumed at t ...

is slightly more erosive to teeth than non-carbonated water but is about 1% as corrosive as soft drinks are.

Chemistry and physical properties

Carbon dioxide

Carbon dioxide is a chemical compound with the chemical formula . It is made up of molecules that each have one carbon atom covalent bond, covalently double bonded to two oxygen atoms. It is found in a gas state at room temperature and at norma ...

gas dissolved in water creates a small amount of carbonic acid

Carbonic acid is a chemical compound with the chemical formula . The molecule rapidly converts to water and carbon dioxide in the presence of water. However, in the absence of water, it is quite stable at room temperature. The interconversion ...

():

:

with the concentration of carbonic acid being about 0.17% that of .

The acid

An acid is a molecule or ion capable of either donating a proton (i.e. Hydron, hydrogen cation, H+), known as a Brønsted–Lowry acid–base theory, Brønsted–Lowry acid, or forming a covalent bond with an electron pair, known as a Lewis ...

gives carbonated water a slightly tart flavor. Its pH level of between 5 and 6 is approximately in between apple juice and orange juice

Orange juice is a liquid extract of the orange (fruit), orange tree fruit, produced by squeezing or reaming oranges. It comes in several different varieties, including blood orange, navel oranges, valencia orange, clementine, and tangerine. As ...

in acidity, but much less acidic than the acid in the stomach. A normal, healthy human body maintains pH equilibrium via acid–base homeostasis

Acid–base homeostasis is the homeostasis, homeostatic regulation of the pH of the Body fluid, body's extracellular fluid (ECF). The proper #Acid–base balance, balance between the acids and Base (chemistry), bases (i.e. the pH) in the ECF is cr ...

and will not be materially adversely affected by consumption of plain carbonated water. Carbon dioxide in the blood is expelled through the lungs. Alkaline

In chemistry, an alkali (; from the Arabic word , ) is a basic salt of an alkali metal or an alkaline earth metal. An alkali can also be defined as a base that dissolves in water. A solution of a soluble base has a pH greater than 7.0. The ...

salts

In chemistry, a salt or ionic compound is a chemical compound consisting of an assembly of positively charged ions ( cations) and negatively charged ions (anions), which results in a compound with no net electric charge (electrically neutral). ...

, such as sodium bicarbonate

Sodium bicarbonate ( IUPAC name: sodium hydrogencarbonate), commonly known as baking soda or bicarbonate of soda (or simply “bicarb” especially in the UK) is a chemical compound with the formula NaHCO3. It is a salt composed of a sodium cat ...

, potassium bicarbonate

Potassium bicarbonate ( IUPAC name: potassium hydrogencarbonate, also known as potassium acid carbonate) is the inorganic compound with the chemical formula KHCO3. It is a white solid.

Production and reactivity

It is manufactured by treating an ...

, or potassium citrate

Potassium citrate (also known as tripotassium citrate) is a potassium salt of citric acid with the molecular formula K3C6H5O7. It is a white, hygroscopic crystalline powder. It is odorless with a saline taste. It contains 38.28% potassium by mass ...

, will increase pH.

The amount of a gas that can be dissolved in water is described by Henry's Law

In physical chemistry, Henry's law is a gas law that states that the amount of dissolved gas in a liquid is directly proportional at equilibrium to its partial pressure above the liquid. The proportionality factor is called Henry's law constant ...

. The coefficient depends on the temperature. In the carbonization process, water is chilled, optimally to just above freezing, to maximize the amount of carbon dioxide that can be dissolved in it. Higher gas pressure and lower temperature cause more gas to dissolve in the liquid. When the temperature is raised or the pressure is reduced (as happens when a container of carbonated water is opened), carbon dioxide effervesces, thereby escaping from the solution.

The density of carbonated water is slightly greater than that of pure water. The volume of a quantity of carbonated water can be calculated by taking the volume of the water and adding 0.8 cubic centimetres for each gram of .

History

Many

Many alcoholic drink

Drinks containing alcohol (drug), alcohol are typically divided into three classes—beers, wines, and Distilled beverage, spirits—with alcohol content typically between 3% and 50%. Drinks with less than 0.5% are sometimes considered Non-al ...

s, such as beer

Beer is an alcoholic beverage produced by the brewing and fermentation of starches from cereal grain—most commonly malted barley, although wheat, maize (corn), rice, and oats are also used. The grain is mashed to convert starch in the ...

, champagne

Champagne (; ) is a sparkling wine originated and produced in the Champagne wine region of France under the rules of the appellation, which demand specific vineyard practices, sourcing of grapes exclusively from designated places within it, spe ...

, cider

Cider ( ) is an alcoholic beverage made from the Fermented drink, fermented Apple juice, juice of apples. Cider is widely available in the United Kingdom (particularly in the West Country) and Ireland. The United Kingdom has the world's highest ...

, and spritzer

A spritzer () is a tall, chilled drink, usually made with white wine and carbonated water or sparkling mineral water. Fermented simple syrup can be used instead of white wine to keep it sweet but flavor neutral.

Origin

''Spritzer'' is deriv ...

, were naturally carbonated through the fermentation process. In 1662 Christopher Merret

Christopher Merret FRSFRCP(16 February 1614/1615 – 19 August 1695), also spelt Merrett, was an English physician and scientist. He was the first to document the deliberate addition of sugar for the production of sparkling wine

Sparkli ...

created 'sparkling wine'. William Brownrigg

William Brownrigg ( – 6 January 1800) was an English physician and scientist who practised at Whitehaven in Cumberland. While there, Brownrigg carried out experiments that earned him the Copley Medal in 1766 for his work on carbonic acid gas. H ...

was apparently the first to produce artificial carbonated water, in the early 1740s, by using carbon dioxide taken from mines. In 1750 the Frenchman Gabriel François Venel also produced artificial carbonated water, though he misunderstood the nature of the gas that caused the carbonation. In 1764, Irish chemist Dr. Macbride infused water with carbon dioxide as part of a series of experiments on fermentation and putrefaction. In 1766 Henry Cavendish

Henry Cavendish ( ; 10 October 1731 – 24 February 1810) was an English experimental and theoretical chemist and physicist. He is noted for his discovery of hydrogen, which he termed "inflammable air". He described the density of inflammable a ...

devised an aerating apparatus that would inspire Joseph Priestley

Joseph Priestley (; 24 March 1733 – 6 February 1804) was an English chemist, Unitarian, Natural philosophy, natural philosopher, English Separatist, separatist theologian, Linguist, grammarian, multi-subject educator and Classical libera ...

to carry out his own experiments with regard to carbonated waters. Cavendish was also aware of Brownrigg's observations at this time and published a paper on his own experiments on a nearby source of mineral water at the beginning of January in the next year.

In 1767 Priestley discovered a method of infusing water with carbon dioxide by pouring water back and forth above a beer vat at a local brewery in

In 1767 Priestley discovered a method of infusing water with carbon dioxide by pouring water back and forth above a beer vat at a local brewery in Leeds

Leeds is a city in West Yorkshire, England. It is the largest settlement in Yorkshire and the administrative centre of the City of Leeds Metropolitan Borough, which is the second most populous district in the United Kingdom. It is built aro ...

, England."The Man Who Discovered Oxygen and Gave the World Soda Water"New York Times. Retrieved 10 January 2015 The air blanketing the fermenting beer—called 'fixed air'—was known to kill mice suspended in it. Priestley found water thus treated had a pleasant taste, and he offered it to friends as a cool, refreshing drink. In 1772, Priestley published a paper titled ''Impregnating Water with Fixed Air'' in which he describes dripping "oil of vitriol" (

sulfuric acid

Sulfuric acid (American spelling and the preferred IUPAC name) or sulphuric acid (English in the Commonwealth of Nations, Commonwealth spelling), known in antiquity as oil of vitriol, is a mineral acid composed of the elements sulfur, oxygen, ...

) onto chalk

Chalk is a soft, white, porous, sedimentary carbonate rock. It is a form of limestone composed of the mineral calcite and originally formed deep under the sea by the compression of microscopic plankton that had settled to the sea floor. Ch ...

to produce carbon dioxide gas, and encouraging the gas to dissolve into an agitated bowl of water. Priestley referred to his invention of this treated water as being his "happiest" discovery.

Priestley's apparatus, which was very similar to that invented by Henry Cavendish five years earlier, featured a bladder between the generator and the absorption tank to regulate the flow of carbon dioxide, and was soon joined by a wide range of others, but it was not until 1781 that companies specialized in producing artificial mineral water were established and began producing carbonated water on a large scale. The first factory was built by Thomas Henry of Manchester

Manchester () is a city and the metropolitan borough of Greater Manchester, England. It had an estimated population of in . Greater Manchester is the third-most populous metropolitan area in the United Kingdom, with a population of 2.92&nbs ...

, England. Henry replaced the bladder in Priestley's system with large bellows. J. J. Schweppe developed a process to manufacture bottled carbonated mineral water based on the discovery of Priestley, founding the Schweppes

Schweppes ( , ) is a soft drink brand founded in the Republic of Geneva in 1783 by the German watchmaker and amateur scientist Johann Jacob Schweppe; it is now made, bottled, and distributed worldwide by multiple international conglomerates, de ...

Company in Geneva in 1783. Schweppes regarded Priestley as "the father of our industry". In 1792, Schweppe moved to London to develop the business there. In 1799 Augustine Thwaites founded Thwaites' Soda Water in Dublin. A ''London Globe'' article claims that this company was the first to patent and sell "Soda Water" under that name. The article says that in the hot summer of 1777 in London "aerated waters" (that is, carbonated) were selling well but there was as yet no mention of "soda water", though the first effervescent drinks were probably made using " soda powders" containing bicarbonate of soda and tartaric acid

Tartaric acid is a white, crystalline organic acid that occurs naturally in many fruits, most notably in grapes but also in tamarinds, bananas, avocados, and citrus. Its salt (chemistry), salt, potassium bitartrate, commonly known as cream of ta ...

. The name soda water arose from the fact that soda (sodium carbonate

Sodium carbonate (also known as washing soda, soda ash, sal soda, and soda crystals) is the inorganic compound with the formula and its various hydrates. All forms are white, odourless, water-soluble salts that yield alkaline solutions in water ...

or bicarbonate

In inorganic chemistry, bicarbonate (IUPAC-recommended nomenclature: hydrogencarbonate) is an intermediate form in the deprotonation of carbonic acid. It is a polyatomic anion with the chemical formula .

Bicarbonate serves a crucial bioche ...

) was often added to adjust the taste and pH.

Modern carbonated water is made by injecting pressurized carbon dioxide

Carbon dioxide is a chemical compound with the chemical formula . It is made up of molecules that each have one carbon atom covalent bond, covalently double bonded to two oxygen atoms. It is found in a gas state at room temperature and at norma ...

into water. The pressure increases the solubility

In chemistry, solubility is the ability of a chemical substance, substance, the solute, to form a solution (chemistry), solution with another substance, the solvent. Insolubility is the opposite property, the inability of the solute to form su ...

and allows more carbon dioxide to dissolve than would be possible under standard atmospheric pressure

The standard atmosphere (symbol: atm) is a unit of pressure defined as Pa. It is sometimes used as a ''reference pressure'' or ''standard pressure''. It is approximately equal to Earth's average atmospheric pressure at sea level.

History

The ...

. When the bottle is opened, the pressure is released, allowing gas to exit the solution, forming the characteristic bubbles.

Modern sources of are from industrial processes, such as burning of fossil fuels like coal and methane at power plants, or steam reforming

Steam reforming or steam methane reforming (SMR) is a method for producing syngas (hydrogen and carbon monoxide) by reaction of hydrocarbons with water. Commonly, natural gas is the feedstock. The main purpose of this technology is often hydrogen ...

of methane for hydrogen production

Hydrogen gas is produced by several industrial methods. Nearly all of the world's current supply of hydrogen is created from fossil fuels. Article in press. Most hydrogen is ''gray hydrogen'' made through steam methane reforming. In this process, ...

.

Etymology

In the United States, plain carbonated water was generally known either as ''soda water'', due to the sodium salts it contained, or ''seltzer water'', deriving from the German town Selters renowned for itsmineral springs

Mineral springs are naturally occurring springs that produce hard water, water that contains dissolved minerals. Salts, sulfur compounds, and gases are among the substances that can be dissolved in the spring water during its passage underg ...

.

Sodium salts were added to plain water both as flavoring (to mimic famed mineral water

Mineral water is water from a mineral spring that contains various minerals, such as salts and sulfur compounds. It is usually still, but may be sparkling ( carbonated/ effervescent).

Traditionally, mineral waters were used or consumed at t ...

s, such as naturally effervescent '' Selters'', ''Vichy water'' and '' Saratoga Water'') and acidity regulators (to offset the acidic 5-6 pH carbonic acid

Carbonic acid is a chemical compound with the chemical formula . The molecule rapidly converts to water and carbon dioxide in the presence of water. However, in the absence of water, it is quite stable at room temperature. The interconversion ...

created when carbon dioxide is dissolved in water).

In the 1950s the term club soda

Club soda is a form of carbonated water manufactured in North America, commonly used as a drink mixer. Sodium bicarbonate, potassium sulfate, potassium bicarbonate, potassium citrate, or sodium citrate is added to artificially replicate constitu ...

began to be popularized.

Generally, ''seltzer water'' has no added sodium salts, while ''club soda'' still retains some sodium salts.

Products for carbonating water

Home

Soda siphons

The soda siphon, or seltzer bottle—a glass or metal pressure vessel with a release valve and spout for dispensing pressurized soda water—was a common sight in bars and in early- to mid-20th-century homes where it became a symbol of middle-class affluence.

The gas pressure in a siphon drives soda water up through a tube inside the siphon when a valve lever at the top is depressed. Commercial soda siphons came pre-charged with water and gas and were returned to the retailer for exchange when empty. A deposit scheme ensured they were not otherwise thrown away.

Home soda siphons can carbonate flatwater through the use of a small disposable steel bulb containing carbon dioxide. The bulb is pressed into the valve assembly at the top of the siphon, the gas injected, then the bulb withdrawn.

The soda siphon, or seltzer bottle—a glass or metal pressure vessel with a release valve and spout for dispensing pressurized soda water—was a common sight in bars and in early- to mid-20th-century homes where it became a symbol of middle-class affluence.

The gas pressure in a siphon drives soda water up through a tube inside the siphon when a valve lever at the top is depressed. Commercial soda siphons came pre-charged with water and gas and were returned to the retailer for exchange when empty. A deposit scheme ensured they were not otherwise thrown away.

Home soda siphons can carbonate flatwater through the use of a small disposable steel bulb containing carbon dioxide. The bulb is pressed into the valve assembly at the top of the siphon, the gas injected, then the bulb withdrawn.

Gasogene

The gasogene (or gazogene, or seltzogene) is a late

The gasogene (or gazogene, or seltzogene) is a late Victorian

Victorian or Victorians may refer to:

19th century

* Victorian era, British history during Queen Victoria's 19th-century reign

** Victorian architecture

** Victorian house

** Victorian decorative arts

** Victorian fashion

** Victorian literatur ...

device for producing carbonated water. It consists of two linked glass globes: the lower contained water or other drink to be made sparkling, the upper a mixture of tartaric acid

Tartaric acid is a white, crystalline organic acid that occurs naturally in many fruits, most notably in grapes but also in tamarinds, bananas, avocados, and citrus. Its salt (chemistry), salt, potassium bitartrate, commonly known as cream of ta ...

and sodium bicarbonate

Sodium bicarbonate ( IUPAC name: sodium hydrogencarbonate), commonly known as baking soda or bicarbonate of soda (or simply “bicarb” especially in the UK) is a chemical compound with the formula NaHCO3. It is a salt composed of a sodium cat ...

that reacts to produce carbon dioxide

Carbon dioxide is a chemical compound with the chemical formula . It is made up of molecules that each have one carbon atom covalent bond, covalently double bonded to two oxygen atoms. It is found in a gas state at room temperature and at norma ...

. The produced gas pushes the liquid in the lower container up a tube and out of the device. The globes are surrounded by a wicker

Wicker is a method of weaving used to make products such as furniture and baskets, as well as a descriptor to classify such products. It is the oldest furniture making method known to history, dating as far back as . Wicker was first documented ...

or wire protective mesh, as they have a tendency to explode.

Codd-neck bottles

In 1872, soft drink maker Hiram Codd of

In 1872, soft drink maker Hiram Codd of Camberwell

Camberwell ( ) is an List of areas of London, area of South London, England, in the London Borough of Southwark, southeast of Charing Cross.

Camberwell was first a village associated with the church of St Giles' Church, Camberwell, St Giles ...

, London, designed and patented the Codd-neck bottle

A Codd-neck bottle (more commonly known as a Codd bottle or a marble bottle) is a type of bottle used for carbonated drinks. It has a closing design based on a glass marble which is held against a rubber seal, which sits within a recess in the li ...

, designed specifically for carbonated

Carbonation is the chemical reaction of carbon dioxide to give carbonates, bicarbonates, and carbonic acid. In chemistry, the term is sometimes used in place of carboxylation, which refers to the formation of carboxylic acids.

In inorganic che ...

drinks. The ''Codd-neck bottle'' encloses a marble

Marble is a metamorphic rock consisting of carbonate minerals (most commonly calcite (CaCO3) or Dolomite (mineral), dolomite (CaMg(CO3)2) that have recrystallized under the influence of heat and pressure. It has a crystalline texture, and is ty ...

and a rubber

Rubber, also called India rubber, latex, Amazonian rubber, ''caucho'', or ''caoutchouc'', as initially produced, consists of polymers of the organic compound isoprene, with minor impurities of other organic compounds.

Types of polyisoprene ...

washer/gasket in the neck. The bottles were filled upside down, and pressure of the gas

Gas is a state of matter that has neither a fixed volume nor a fixed shape and is a compressible fluid. A ''pure gas'' is made up of individual atoms (e.g. a noble gas like neon) or molecules of either a single type of atom ( elements such as ...

in the bottle forced the marble against the washer, sealing in the carbonation. The bottle was pinched into a special shape to provide a chamber into which the marble was pushed to open the bottle. This prevented the marble from blocking the neck as the drink was poured.

Soon after its introduction, the bottle became extremely popular with the soft drink and brewing

Brewing is the production of beer by steeping a starch source (commonly cereal grains, the most popular of which is barley) in water and #Fermenting, fermenting the resulting sweet liquid with Yeast#Beer, yeast. It may be done in a brewery ...

industries mainly in the UK and the rest of Europe, Asia, and Australasia, though some alcohol

Alcohol may refer to:

Common uses

* Alcohol (chemistry), a class of compounds

* Ethanol, one of several alcohols, commonly known as alcohol in everyday life

** Alcohol (drug), intoxicant found in alcoholic beverages

** Alcoholic beverage, an alco ...

drinkers disdained the use of the bottle. R. White's, the biggest soft drinks company in London and south-east England when the bottle was introduced, was among the companies that sold their drinks in Codd's glass bottles. One etymology

Etymology ( ) is the study of the origin and evolution of words—including their constituent units of sound and meaning—across time. In the 21st century a subfield within linguistics, etymology has become a more rigorously scientific study. ...

of the term ''codswallop

{{Short pages monitor