Spanish Civil War And Foreign Involvement on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The international response to the

The British government proclaimed neutrality, and its foreign policy was to prevent a major war by appeasement of Italy and Germany. British leaders believed that the Spanish Republican government was the puppet of extreme-left socialists and communists. Accordingly, the British Cabinet adopted a policy of benevolent neutrality towards the military insurgents, a covert aim being to avoid any direct or indirect help to the Republic. Public opinion was divided, with a clear majority demanding another major war be avoided. A large part of the

The British government proclaimed neutrality, and its foreign policy was to prevent a major war by appeasement of Italy and Germany. British leaders believed that the Spanish Republican government was the puppet of extreme-left socialists and communists. Accordingly, the British Cabinet adopted a policy of benevolent neutrality towards the military insurgents, a covert aim being to avoid any direct or indirect help to the Republic. Public opinion was divided, with a clear majority demanding another major war be avoided. A large part of the

When the Spanish Civil War erupted, US Secretary of State

When the Spanish Civil War erupted, US Secretary of State

The Italians provided the "

The Italians provided the "

Upon the outbreak of the civil war, Portuguese Prime Minister

Upon the outbreak of the civil war, Portuguese Prime Minister

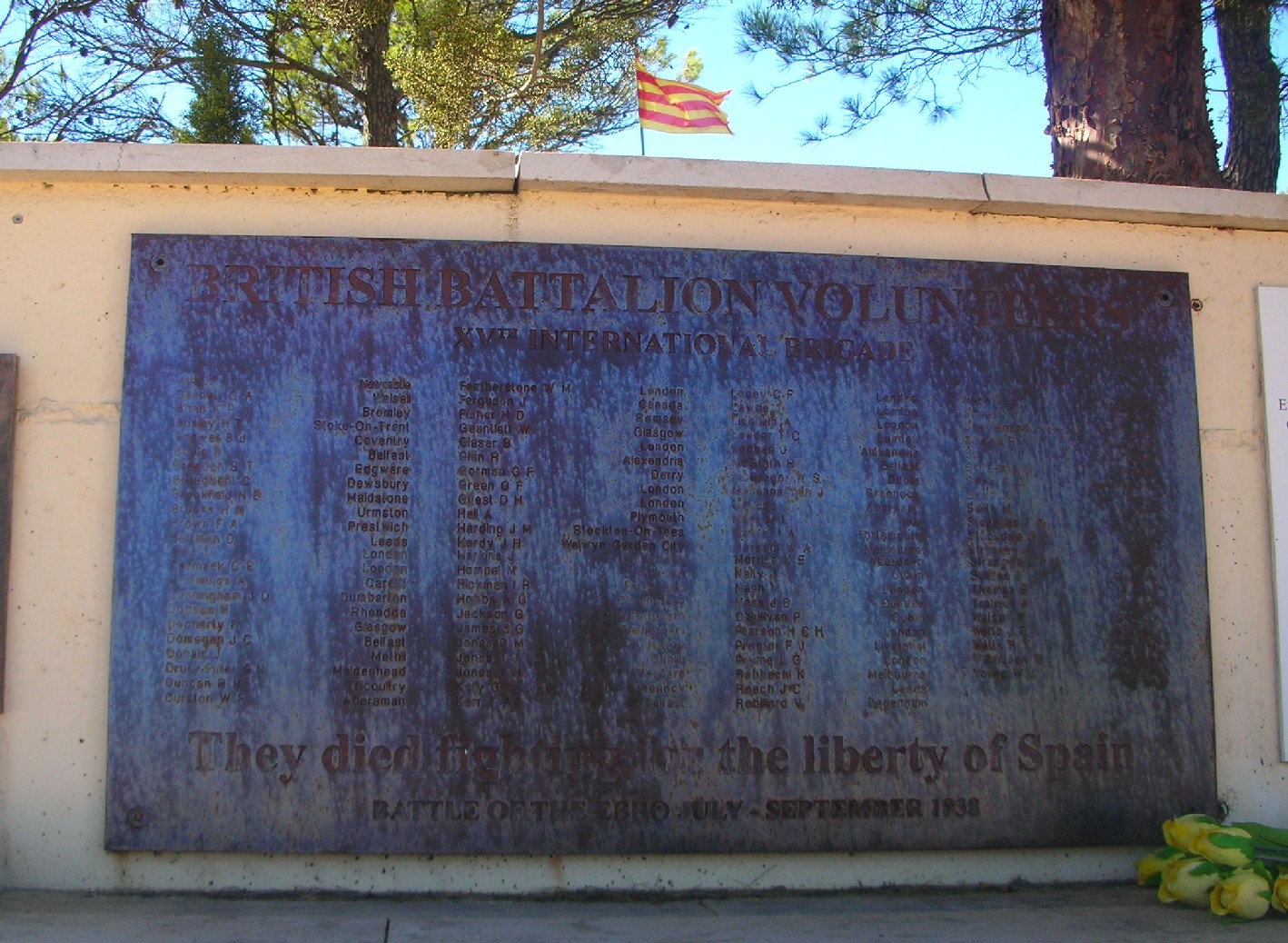

Volunteers from many countries fought in Spain, most of them for the Republicans. About 32,000 fought in the

Volunteers from many countries fought in Spain, most of them for the Republicans. About 32,000 fought in the

Probably 32,000 foreigners fought in the communist

Probably 32,000 foreigners fought in the communist

Spanish Civil War

The Spanish Civil War () was a military conflict fought from 1936 to 1939 between the Republican faction (Spanish Civil War), Republicans and the Nationalist faction (Spanish Civil War), Nationalists. Republicans were loyal to the Left-wing p ...

included many non-Spaniards

Spaniards, or Spanish people, are a Romance-speaking ethnic group native to the Iberian Peninsula, primarily associated with the modern nation-state of Spain. Genetically and ethnolinguistically, Spaniards belong to the broader Southern a ...

participating in combat and advisory positions. The governments of Italy, Germany and, to a lesser extent, Portugal contributed money, munitions, manpower and support to the Nationalist

Nationalism is an idea or movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the State (polity), state. As a movement, it presupposes the existence and tends to promote the interests of a particular nation,Anthony D. Smith, Smith, A ...

forces, led by Francisco Franco

Francisco Franco Bahamonde (born Francisco Paulino Hermenegildo Teódulo Franco Bahamonde; 4 December 1892 – 20 November 1975) was a Spanish general and dictator who led the Nationalist faction (Spanish Civil War), Nationalist forces i ...

. Some nations that declared neutrality favored the nationalists indirectly. The governments of the Soviet Union and, to a lesser extent, Mexico, aided the Republicans

Republican can refer to:

Political ideology

* An advocate of a republic, a type of government that is not a monarchy or dictatorship, and is usually associated with the rule of law.

** Republicanism, the ideology in support of republics or agains ...

, also called Loyalists, of the Second Spanish Republic

The Spanish Republic (), commonly known as the Second Spanish Republic (), was the form of democratic government in Spain from 1931 to 1939. The Republic was proclaimed on 14 April 1931 after the deposition of Alfonso XIII, King Alfonso XIII. ...

. The aid came even after all the European powers had signed a Non-Intervention Agreement

During the Spanish Civil War, most European countries followed a policy of non-intervention to avoid potential escalation or expansion of the war to other states. This policy led to the signing of the Non-Intervention Agreement in August 1936 a ...

in 1936. Although individual sympathy for the plight of the Spanish Republic was widespread in the liberal democracies, pacifism and the fear of a second world war prevented them from selling or giving arms. However, Nationalist pleas were answered within days by Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (20 April 1889 – 30 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was the dictator of Nazi Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his suicide in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the lea ...

and Benito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who, upon assuming office as Prime Minister of Italy, Prime Minister, became the dictator of Fascist Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 un ...

. Tens of thousands of individual foreign volunteers travelled to Spain to fight, the majority for the Republican side.

International non-intervention

Non-intervention had been proposed in a joint diplomatic initiative by the governments ofFrance

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

and the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Northwestern Europe, off the coast of European mainland, the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

, which responded to antiwar sentiment. France was also worried that sympathisers of the Nationalists would cause a civil war in France. Non-intervention was part of a policy aimed at preventing a proxy war

In political science, a proxy war is an armed conflict where at least one of the belligerents is directed or supported by an external third-party power. In the term ''proxy war'', a belligerent with external support is the ''proxy''; both bel ...

and the escalation of the war into a second world war.

On 3 August 1936, Charles de Chambrun presented the French government's non-intervention plan, and Galeazzo Ciano

Gian Galeazzo Ciano, 2nd Count of Cortellazzo and Buccari ( , ; 18 March 1903 – 11 January 1944), was an Italian diplomat and politician who served as Italian Minister of Foreign Affairs, Foreign Minister in the government of his father-in-law ...

promised to study it. The British, however, immediately accepted the plan in principle. The next day, it was put to Germany by André François-Poncet

André François-Poncet (13 June 1887 – 8 January 1978) was a French politician and diplomat whose post as ambassador to Germany allowed him to witness first-hand the rise to power of Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party, and the Nazi regime's prep ...

. The German position was that such a declaration was not needed. A similar approach was made to the Soviet Union. On 6 August, Ciano confirmed Italian support in principle. The Soviet government similarly agreed in principle if Portugal was included and Germany and Italy stopped aid immediately. On 7 August, France unilaterally declared its non-intervention. Draft declarations had been put to German and Italian governments. Such a declaration had already been accepted by the United Kingdom, Belgium, the Netherlands, Poland, Czechoslovakia and the Soviet Union and required renouncing all traffic in war matériel

Materiel or matériel (; ) is supplies, equipment, and weapons in military supply-chain management, and typically supplies and equipment in a commercial supply chain context.

Military

In a military context, the term ''materiel'' refers eith ...

, direct or indirect. Portuguese Foreign Minister Armindo Monteiro

Armindo Rodrigues de Sttau Monteiro (16 December 1896 – 15 October 1955), known as Armindo Monteiro, was a Portuguese university professor, businessman, diplomat and politician who exercised important functions during the Estado Novo perio ...

See also :pt:Armindo Rodrigues de Sttau Monteiro was also asked to accept but held his hand. On 9 August, French exports were suspended. Portugal accepted the pact on 13 August unless its border was threatened by the war.

On 15 August, the United Kingdom banned exports of war material to Spain. Italy agreed to the pact and signing on 21 August. That there was a surprising reversal of views has been put down to the growing belief that countries could not or indeed would not abide by the agreement anyway. On 24 August, Germany signed. The Soviet Union was keen not to be left out, and on 23 August, it agreed to the Non-Intervention Agreement, which was followed by a decree from Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Dzhugashvili; 5 March 1953) was a Soviet politician and revolutionary who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until Death and state funeral of Joseph Stalin, his death in 1953. He held power as General Secret ...

banning exports of war matérial to Spain, thereby bringing the Soviets into line with the Western powers.

Non-Intervention Committee

It was then that the Non-Intervention Committee was created to uphold the agreement, but the double dealing of both the Soviet Union and Germany had already become apparent. The ostensible purpose of the committee was to prevent personnel and matériel reaching the warring parties, as with the Non-Intervention Agreement. The committee first met in London on 9 September 1936.Involved were Albania, Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Czechoslovakia, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Norway, Poland, Romania, Turkey, the Soviet Union, the United Kingdom and Yugoslavia. It was chaired by the British W. S. Morrison. France was represented by Charles Corbin, Italy byDino Grandi

Dino Grandi, 1st Conte di Mordano (4 June 1895 – 21 May 1988), was an Italian Fascist politician, minister of justice, minister of foreign affairs and president of Parliament.

Early life

Born at Mordano, province of Bologna, Grandi was ...

and the Soviet Union by Ivan Maisky

Ivan Mikhailovich Maisky (also transliterated as "Maysky"; ) (19 January 1884 – 3 September 1975) was a Soviet diplomat, historian and politician who served as the Soviet Union's ambassador to the United Kingdom

from 1932 to 1943, includi ...

. Germany was represented by Joachim von Ribbentrop

Ulrich Friedrich-Wilhelm Joachim von Ribbentrop (; 30 April 1893 – 16 October 1946) was a German Nazi politician and diplomat who served as Minister for Foreign Affairs (Germany), Minister of Foreign Affairs of Nazi Germany from 1938 to 1945. ...

, and Portugal, whose presence had been a Soviet requirement, was not represented. The second meeting took place on 14 September. It established a subcommittee to be attended by representatives of Belgium, Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia ( ; Czech language, Czech and , ''Česko-Slovensko'') was a landlocked country in Central Europe, created in 1918, when it declared its independence from Austria-Hungary. In 1938, after the Munich Agreement, the Sudetenland beca ...

, France, Germany, Italy, the Soviet Union, Sweden

Sweden, formally the Kingdom of Sweden, is a Nordic countries, Nordic country located on the Scandinavian Peninsula in Northern Europe. It borders Norway to the west and north, and Finland to the east. At , Sweden is the largest Nordic count ...

and the United Kingdom to deal with the day-to-day running of non-intervention. Among them, however, the United Kingdom, France, Germany and Italy dominated, perhaps worryingly so, Soviet non-military aid was revived but not military aid.

Meanwhile, the 1936 meeting of the League of Nations

The League of Nations (LN or LoN; , SdN) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference (1919–1920), Paris Peace ...

began. There, Anthony Eden

Robert Anthony Eden, 1st Earl of Avon (12 June 1897 – 14 January 1977) was a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom and Leader of the Conservative Party from 1955 until his resignation in 1957.

Achi ...

convinced Monteiro to have Portugal join the Non-Intervention Committee. Álvarez del Vayo Álvarez or Álvares may refer to:

People

* Álvarez (surname), Spanish surname

Places

* Alvares (river), a river in northern Spain

* Alvares (ski resort), in Iran

* Alvares, Iran

* Alvares, Portugal

* Álvarez, Santa Fe, a town in the province o ...

spoke out against the Non-Intervention Agreement and claimed that it put the rebel Nationalists on the same footing as the Republican government. The Earl of Plymouth

Earl of Plymouth is a title that has been created three times: twice in the Peerage of England and once in the Peerage of the United Kingdom.

History

The first creation was in 1675 for Charles FitzCharles, one of the dozens of illegitimate ...

replaced Morrison as the British representative. The Conservative member often adjourned meetings to the benefit of the Italians and Germans, and the committee was accused of having an anti-Soviet bias.

On 12 November, plans to post observers to Spanish frontiers and ports to prevent breaches of the agreement were ratified. France and the United Kingdom became divided on whether to recognise Franco's forces as a belligerent

A belligerent is an individual, group, country, or other entity that acts in a hostile manner, such as engaging in combat. The term comes from the Latin ''bellum gerere'' ("to wage war"). Unlike the use of ''belligerent'' as an adjective meanin ...

, as the British wanted, or to fail to do, as the French wanted. That was subsumed by the news that the Italian and German governments had recognised the Nationalists as the true government of Spain. The League of Nations condemned intervention, urged its council's members to support non-intervention and commended mediation. It then closed discussion on Spain and left it to the committee. A mediation plan, however, was soon dropped.

The Soviets met the request to ban volunteers on 27 December, followed by Portugal on 5 January and Germany and Italy on 7 January. On 20 January, Italy put a moratorium on volunteers since it believed that supplies to the Nationalists were now sufficient. Non-intervention would have left both sides with the possibility of defeat, which Germany, Italy and the Soviet Union in particular were keen to avoid.

Control plan

Observers were posted to Spanish ports and borders, and both Ribbentrop and Grandi were told to agree to the plan, significant shipments already having taken place. Portugal would not accept observers but agreed to personnel attached to the British embassy inLisbon

Lisbon ( ; ) is the capital and largest city of Portugal, with an estimated population of 567,131, as of 2023, within its administrative limits and 3,028,000 within the Lisbon Metropolitan Area, metropolis, as of 2025. Lisbon is mainlan ...

. Zones of patrol were assigned to each of the four nations, and an International Board was set up to administer the scheme. There were assurances by Italy that it would not end non-intervention.

In May, the committee noted two attacks on the patrol's ships by Republican aircraft. It iterated calls for the withdrawal of volunteers from Spain, condemned the bombing of open towns and showed approval of humanitarian work. Germany and Italy stated that they would withdraw from the committee and from the patrols without guarantees of no further attacks. Early June saw the return of Germany and Italy to the committee and the patrols. Attacks on the German cruiser ''Leipzig

Leipzig (, ; ; Upper Saxon: ; ) is the most populous city in the States of Germany, German state of Saxony. The city has a population of 628,718 inhabitants as of 2023. It is the List of cities in Germany by population, eighth-largest city in Ge ...

'' on 15 and 18 June made Germany and Italy once again withdraw from patrols but not from the committee. That prompted the Portuguese government to remove British observers on the Spanish-Portuguese border. The United Kingdom and France offered to replace Germany and Italy, which, however, believed that they would be too partial. Germany and Italy requested for land controls to be kept and for belligerent rights to be given to the Nationalists to allow rights of search to be used by both the Republicans and the Nationalists to replace naval patrols. A British plan suggested naval patrols to be replaced by observers in ports and ships, with land control measures being resumed. Belligerent rights would not be granted until substantial progress was made on the volunteer withdrawal.

That culminated in a period during 1937 during which all of the powers were prepared to give up on non-intervention. By the end of July, the committee was in deadlock, and the aims of a successful outcome to the Spanish Civil War was looking unlikely for the Republic. Unrestricted Italian submarine warfare began on 12 August. The British Admiralty

The Admiralty was a Departments of the Government of the United Kingdom, department of the Government of the United Kingdom that was responsible for the command of the Royal Navy.

Historically, its titular head was the Lord High Admiral of the ...

believed that a significant control effort was the best solution to attacks on British shipping. The committee decided that naval patrols did not justify the expense and would be replaced with observers at ports.

The Conference of Nyon was arranged by the British for all parties with a Mediterranean coastline, despite appeals by Italy and Germany for the committee to handle piracy and the other issues that the conference was to discuss. It decided for French and British fleets to patrol the areas of sea west of Malta

Malta, officially the Republic of Malta, is an island country in Southern Europe located in the Mediterranean Sea, between Sicily and North Africa. It consists of an archipelago south of Italy, east of Tunisia, and north of Libya. The two ...

and to attack any suspicious submarines. Also, warships that attacked neutral shipping would be attacked. Eden claimed that non-intervention had stopped a European war. The League of Nations reported on the Spanish situation by noting the "failure of non-intervention". On 6 November, the plan to recognise the Nationalists as belligerents, once significant progress had been made, was finally accepted. The Nationalists accepted on 20 November and the Republicans on 1 December. On 27 June, Maisky agreed to send two commissions to Spain to enumerate foreign volunteer forces and to bring about their withdrawal. The Nationalists, wishing to prevent the fall of the sympathetic British government, led by Neville Chamberlain

Arthur Neville Chamberlain (; 18 March 18699 November 1940) was a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from May 1937 to May 1940 and Leader of the Conservative Party (UK), Leader of the Conservative Party from ...

, were seen to accept the plan.

National non-intervention

United Kingdom and France

British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories and Crown Dependencies.

* British national identity, the characteristics of British people and culture ...

population was strongly anticommunist

Anti-communism is Political movement, political and Ideology, ideological opposition to communism, communist beliefs, groups, and individuals. Organized anti-communism developed after the 1917 October Revolution in Russia, and it reached global ...

and so tended to prefer a Nationalist victory. However, Popular Front elements on the left strongly favoured the Republican cause.

The ambassador to Spain, Sir Henry Chilton

Sir Henry Getty Chilton (15 October 1877 – 20 November 1954) was a British diplomat who was minister to the Vatican and ambassador to Chile, Argentina and Spain during the Spanish Civil War.

Career

He was educated at Wellington College and ...

, believed that a victory for Franco was in Britain's best interests and so worked to support the Nationalists. British Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden

Robert Anthony Eden, 1st Earl of Avon (12 June 1897 – 14 January 1977) was a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom and Leader of the Conservative Party from 1955 until his resignation in 1957.

Achi ...

publicly maintained the official policy of non-intervention but privately expressed his preference for a Nationalist victory. Eden also testified that his government "preferred a Rebel victory to a Republican victory". he even professed an admiration for the self-proclaimed fascist Calvo Sotelo. Admiral Lord Chatfield, the British First Sea Lord

First Sea Lord, officially known as First Sea Lord and Chief of the Naval Staff (1SL/CNS), is the title of a statutory position in the British Armed Forces, held by an Admiral (Royal Navy), admiral or a General (United Kingdom), general of the ...

in charge of the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the naval warfare force of the United Kingdom. It is a component of His Majesty's Naval Service, and its officers hold their commissions from the King of the United Kingdom, King. Although warships were used by Kingdom ...

, was an admirer of Franco, and the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the naval warfare force of the United Kingdom. It is a component of His Majesty's Naval Service, and its officers hold their commissions from the King of the United Kingdom, King. Although warships were used by Kingdom ...

favoured the Nationalists during the conflict. As well as permitting Franco to set up a signals base in Gibraltar

Gibraltar ( , ) is a British Overseas Territories, British Overseas Territory and British overseas cities, city located at the southern tip of the Iberian Peninsula, on the Bay of Gibraltar, near the exit of the Mediterranean Sea into the A ...

, which was a British colony

A Crown colony or royal colony was a colony governed by England, and then Great Britain or the United Kingdom within the English and later British Empire. There was usually a governor to represent the Crown, appointed by the British monarch on ...

, the British allowed the Germans to overfly Gibraltar during the airlift of the Army of Africa to Seville

Seville ( ; , ) is the capital and largest city of the Spain, Spanish autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community of Andalusia and the province of Seville. It is situated on the lower reaches of the Guadalquivir, River Guadalquivir, ...

. The Royal Navy also provided information on Republican shipping to the Nationalists, and was used to prevent the Republican navy shelling the port of Algeciras

Algeciras () is a city and a municipalities in Spain, municipality of Spain belonging to the province of Cádiz, Andalusia. Located in the southern end of the Iberian Peninsula, near the Strait of Gibraltar, it is the largest city on the Bay of G ...

. The German chargé d'affaires reported that the British were supplying ammunition to the Republicans. During the fighting for Bilbao

Bilbao is a city in northern Spain, the largest city in the Provinces of Spain, province of Biscay and in the Basque Country (greater region), Basque Country as a whole. It is also the largest city proper in northern Spain. Bilbao is the List o ...

, the Royal Navy supported the Nationalist line that the River Nervión

Nervión (; ) is a river that runs through the town of Bilbao, Spain into the Cantabrian Sea (Bay of Biscay). Its lowermost course, downstream of its confluence with the Ibaizabal River, is known as the Estuary of Bilbao.

Geography

The riv ...

was mined and told British shipping to keep clear of the area, but it was badly discredited when a British vessel ignored the advice, sailed into the city and found that the river was unmined, just as the Republicans had claimed. However, the British government discouraged activity from its ordinary citizens to support either side.

The British Labour Party

The Labour Party, often referred to as Labour, is a List of political parties in the United Kingdom, political party in the United Kingdom that sits on the Centre-left politics, centre-left of the political spectrum. The party has been describe ...

was strongly for the Republicans, but was heavily outnumbered by British Conservative Party

The Conservative and Unionist Party, commonly the Conservative Party and colloquially known as the Tories, is one of the two main political parties in the United Kingdom, along with the Labour Party. The party sits on the centre-right to right- ...

in the British Parliament

The Parliament of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland is the supreme legislative body of the United Kingdom, and may also legislate for the Crown Dependencies and the British Overseas Territories. It meets at the Palace of ...

.Alpert (1998) p.65 notes that rank-and-file members of the Labour Party may have been opposed to helping the Republic. The left in France wanted direct aid to the Republicans. The Labour Party would reject non-intervention in October 1937. The Trades Union Congress

The Trades Union Congress (TUC) is a national trade union center, national trade union centre, a federation of trade unions that collectively represent most unionised workers in England and Wales. There are 48 affiliated unions with a total of ...

was split since it had a strong anticommunist faction. Both the British and the French governments were committed to avoiding a second world war.

France was reliant on British support in general. French Prime Minister Léon Blum

André Léon Blum (; 9 April 1872 – 30 March 1950) was a French socialist politician and three-time Prime Minister of France. As a Jew, he was heavily influenced by the Dreyfus affair of the late 19th century. He was a disciple of socialist l ...

, the socialist leader of the Popular Front, feared that support for the Republic would lead to a civil war and then to a fascist takeover of France. In Britain, part of the reasoning was based on an exaggerated belief of both German and Italian preparedness for war.

The arms embargo meant that the Republicans' chief foreign source of matériel

Materiel or matériel (; ) is supplies, equipment, and weapons in military supply-chain management, and typically supplies and equipment in a commercial supply chain context.

Military

In a military context, the term ''materiel'' refers eith ...

was the Soviet Union, and the Nationalists received weapons from Italy mainly and Germany. The last Spanish Republican prime minister, Juan Negrín

Juan Negrín López (; 3 February 1892 – 12 November 1956) was a Spanish physician and politician who served as prime minister of the Second Spanish Republic. He was a leader of the Spanish Socialist Workers' Party (, PSOE) and of the le ...

, hoped that a general outbreak of war in Europe would help his cause by compelling Britain and France to help the Republic at last. Ultimately, however, neither Britain nor France intervened to any significant extent. The British supplied food and medicine to the Republic but actively discouraged Blum and his French government from supplying weapons. Claude Bowers

Claude Gernade Bowers (November 20, 1878 – January 21, 1958) was a newspaper columnist and editor, author of best-selling books on American history, Democratic Party politician, and President Franklin D. Roosevelt's ambassador to Spain (1933� ...

, the US ambassador to Spain, was one of the few ambassadors who was friendly to the Republic. He later condemned the Non-Intervention Committee by saying that each of its moves had been made to serve the cause of the rebellion: "This committee was the most cynical and lamentably dishonest group that history has known".

Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 1874 – 24 January 1965) was a British statesman, military officer, and writer who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1940 to 1945 (Winston Churchill in the Second World War, ...

, who initially was an enthusiastic supporter of non-intervention, later described the workings of the committee as "an elaborate system of official humbug".

After the withdrawal of Germany and Italy from patrols, the French considered abandoning border controls or perhaps leaving non-intervention. However, the French were reliant on the British, who wished to continue with the patrols. Britain and France thus continued to labour over non-intervention and judged it effective although some 42 ships were estimated to have escaped inspection between April and the end of July. In trying to protect non-intervention in the Anglo-Italian meetings, which he grudgingly did, Eden would end up resigning from his post in the British Foreign Office

The Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) is the ministry of foreign affairs and a ministerial department of the government of the United Kingdom.

The office was created on 2 September 2020 through the merger of the Foreign an ...

. On 17 March 1938, Blum reopened the French border to arms traffic, and Soviet arms flowed in to the Republicans in Barcelona.

Britain and France officially recognized the Nationalist government on 27 February 1939. The leader of the Labour Party, Clement Attlee

Clement Richard Attlee, 1st Earl Attlee (3 January 18838 October 1967) was a British statesman who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1945 to 1951 and Leader of the Labour Party (UK), Leader of the Labour Party from 1935 to 1955. At ...

, criticised the way it had been agreed by calling it "a gross betrayal ... two and a half years of hypocritical pretense of non-intervention".

United States

Cordell Hull

Cordell Hull (October 2, 1871July 23, 1955) was an American politician from Tennessee and the longest-serving U.S. Secretary of State, holding the position for 11 years (1933–1944) in the administration of President Franklin Delano Roosevel ...

followed American neutrality laws and moved quickly to ban arms sales to both sides. On 5 August 1936, the United States had made it known that it would follow a policy of non-intervention but failed to announce it officially. Five days later, the Glenn L. Martin Company

The Glenn L. Martin Company, also known as The Martin Company from 1917 to 1961, was an American aircraft and aerospace industry, aerospace manufacturing company founded by aviation pioneer Glenn L. Martin. The Martin Company produced many impo ...

enquired whether the government would allow the sale of eight bombers to the Republicans; the response was negative. The United States also confirmed that it would not take part in several mediation attempts, including by the Organization of American States

The Organization of American States (OAS or OEA; ; ; ) is an international organization founded on 30 April 1948 to promote cooperation among its member states within the Americas.

Headquartered in Washington, D.C., United States, the OAS is ...

. US President Franklin Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), also known as FDR, was the 32nd president of the United States, serving from 1933 until his death in 1945. He is the longest-serving U.S. president, and the only one to have served ...

initially ruled out US interference publicly with these words: "here should be

Here may refer to:

Music

* ''Here'' (Adrian Belew album), 1994

* ''Here'' (Alicia Keys album), 2016

* ''Here'' (Cal Tjader album), 1979

* ''Here'' (Edward Sharpe album), 2012

* ''Here'' (Idina Menzel album), 2004

* ''Here'' (Merzbow album), ...

no expectation that the United States would ever again send troops or warships or floods of munitions and money to Europe". However, he privately supported the Republicans and was concerned that a Nationalist victory would lead to more German influence in Latin America

Latin America is the cultural region of the Americas where Romance languages are predominantly spoken, primarily Spanish language, Spanish and Portuguese language, Portuguese. Latin America is defined according to cultural identity, not geogr ...

.

On 6 January 1937, the first opportunity after the winter break, both houses of the US Congress

The United States Congress is the legislature, legislative branch of the federal government of the United States. It is a Bicameralism, bicameral legislature, including a Lower house, lower body, the United States House of Representatives, ...

passed a resolution banning the export of arms to Spain.It passed by 81–0 in the US Senate

The United States Senate is a chamber of the bicameral United States Congress; it is the upper house, with the U.S. House of Representatives being the lower house. Together, the Senate and House have the authority under Article One of the ...

and 406–1 in the US House of Representatives

The United States House of Representatives is a chamber of the bicameral United States Congress; it is the lower house, with the U.S. Senate being the upper house. Together, the House and Senate have the authority under Article One of th ...

. Those against the bill, including American socialists, communists, and even many liberals, suggested that the export of arms to Germany and Italy should be halted as well under the Neutrality Act of 1935 since foreign intervention was a state of war in Spain. Hull continued to doubt the extent of German and Italian operations, despite evidence to the contrary. In 1938, as the tide had turned against the Loyalists, Roosevelt attempted to bypass the embargo and ship American aircraft to the Republic via France.

The embargo did not apply to nonmilitary supplies, such as oil, gas, or trucks. The US government could thus ship food to Spain as a humanitarian cause, which benefited mostly the Loyalists. The Republicans spent almost $1 million a month on tires, cars, and machine tools from American companies between 1937 and 1938.

Some American businesses supported Franco. The automakers Ford

Ford commonly refers to:

* Ford Motor Company, an automobile manufacturer founded by Henry Ford

* Ford (crossing), a shallow crossing on a river

Ford may also refer to:

Ford Motor Company

* Henry Ford, founder of the Ford Motor Company

* Ford F ...

, Studebaker

Studebaker was an American wagon and automobile manufacturer based in South Bend, Indiana, with a building at 1600 Broadway, Times Square, Midtown Manhattan, New York City. Founded in 1852 and incorporated in 1868 as the Studebaker Brothers Man ...

, and General Motors

General Motors Company (GM) is an American Multinational corporation, multinational Automotive industry, automotive manufacturing company headquartered in Detroit, Michigan, United States. The company is most known for owning and manufacturing f ...

sold a total of 12,000 trucks to the Nationalists. The American-owned Vacuum Oil Company

Vacuum Oil Company was an American petroleum, oil company. After being taken over by the original Standard Oil Company and then becoming independent again, in 1931 Vacuum Oil merged with the Mobil, Standard Oil Company of New York to form Socony ...

in Tangier

Tangier ( ; , , ) is a city in northwestern Morocco, on the coasts of the Mediterranean Sea and the Atlantic Ocean. The city is the capital city, capital of the Tanger-Tetouan-Al Hoceima region, as well as the Tangier-Assilah Prefecture of Moroc ...

refused to sell to Republican ships at the outbreak of the war. The Texas Oil Company

Texaco, Inc. ("The Texas Company") is an American oil brand owned and operated by Chevron Corporation. Its flagship product is its fuel "Texaco with Techron". It also owned the Havoline motor oil brand. Texaco was an independent company until its ...

rerouted oil tankers headed for the Republic to the Nationalist-controlled port of Tenerife

Tenerife ( ; ; formerly spelled ''Teneriffe'') is the largest and most populous island of the Canary Islands, an Autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community of Spain. With a land area of and a population of 965,575 inhabitants as of A ...

and illegally supplied gasoline on credit to Franco. Despite being fined $20,000, the company continued its credit arrangement until the war ended. After the war had ended, José María Doussinague

José María Doussinague y Teixidor (19 January 1894- 11 August 1967) was a Spanish diplomat. He was ambassador to Chile and served as general director of foreign policy at the ministry for foreign affairs during the Francoist dictatorship

Fr ...

, an undersecretary at the Spanish Foreign Ministry, stated that "without American petroleum and American trucks, and American credit, we could never have won the Civil War".

After the war, several American politicians and statesmen identified the US policy of isolation as disastrous. That narrative changed during the Cold War

The Cold War was a period of global Geopolitics, geopolitical rivalry between the United States (US) and the Soviet Union (USSR) and their respective allies, the capitalist Western Bloc and communist Eastern Bloc, which lasted from 1947 unt ...

, when Franco was viewed as an ally against the Soviet Union.

Support for Nationalists

Italy

The Italians provided the "

The Italians provided the "Corps of Volunteer Troops

The Corps of Volunteer Troops () was a Fascist Italian expeditionary force of military volunteers, which was sent to Spain to support the Nationalist forces under General Francisco Franco against the Spanish Republic during the Spanish Civil ...

" (''Corpo Truppe Volontarie''). The use of the troops supported political goals of the German and Italian fascist leaderships, tested new tactics and provided combat experience so that troops would be prepared for any future war.

The involvement in the war helped to increase Mussolini's popularity. The Italian military aid to Nationalists against the anticlerical and anti-Catholic atrocities committed by the Republicans was exploited by Italian propaganda targeting Catholics. On July 27, 1936, the first squadron of Italian airplanes, sent by Mussolini, arrived in Spain. The maximum number of Italians in Spain fighting for the Nationalists, was 50,000 in 1937.

The government of Fascist Italy

Fascist Italy () is a term which is used in historiography to describe the Kingdom of Italy between 1922 and 1943, when Benito Mussolini and the National Fascist Party controlled the country, transforming it into a totalitarian dictatorship. Th ...

participated in the conflict by a body of volunteers from the ranks of the Italian Royal Army (''Regio Esercito

The Royal Italian Army () (RE) was the land force of the Kingdom of Italy, established with the proclamation of the Kingdom of Italy. During the 19th century Italy started to unify into one country, and in 1861 Manfredo Fanti signed a decree c ...

''), Royal Air Force (''Regia Aeronautica

The Royal Italian Air Force (''Regia Aeronautica Italiana'') (RAI) was the air force of the Kingdom of Italy. It was established as a service independent of the Regio Esercito, Royal Italian Army from 1923 until 1946. In 1946, the monarchy was ...

'') and the Royal Navy (''Regia Marina

The , ) (RM) or Royal Italian Navy was the navy of the Kingdom of Italy () from 1861 to 1946. In 1946, with the birth of the Italian Republic (''Repubblica Italiana''), the changed its name to '' Marina Militare'' ("Military Navy").

Origin ...

''), which were formed into an expeditionary force, the Corps of Volunteer Troops (''Corpo Truppe Volontarie

The Corps of Volunteer Troops () was a Fascist Italian expeditionary force of military volunteers, which was sent to Spain to support the Nationalist forces under General Francisco Franco against the Spanish Republic during the Spanish Civil ...

'', CTV). Italians also served in the Spanish-Italian Flechas Brigades and Divisions. The airborne component of Aeronautica pilots and ground crew were known as "Aviation Legion" (''Aviazione Legionaria

The Legionary Air Force (, ) was an expeditionary corps from the Italian Royal Air Force that was set up in 1936. It was sent to provide logistical and tactical support to the Nationalist faction after the Spanish coup of July 1936, which mar ...

'') and the contingent of submariners as Submarine Legion ('' Sottomarini Legionari''). About 6,000 Italians are estimated to have died in the conflict. ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''NYT'') is an American daily newspaper based in New York City. ''The New York Times'' covers domestic, national, and international news, and publishes opinion pieces, investigative reports, and reviews. As one of ...

'' correspondent in Seville

Seville ( ; , ) is the capital and largest city of the Spain, Spanish autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community of Andalusia and the province of Seville. It is situated on the lower reaches of the Guadalquivir, River Guadalquivir, ...

, Frank L. Kluckhohn, reported on 18 August that "the presence of the Italian destroyer ''Antonio da Noli'' here means that an ally has come to help the insurgents".

Mussolini sent massive material aid to Italian forces in Spain that included:

*one cruiser, four destroyers and two submarines;

*763 aircraft, including 64 Savoia-Marchetti SM.81 bombers, at least 90 Savoia-Marchetti SM.79

The Savoia-Marchetti SM.79 ''Sparviero'' (Italian for sparrowhawk) is a three-engined medium bomber developed and manufactured by the Italian aviation company Savoia-Marchetti. It may be the best-known Italian aeroplane of the Second World War. ...

bombers, 13 Br.20 bombers, 16 Ca.310 bombers, 44 assault planes, at least 20 seaplanes, more than 300 Fiat CR.32 fighters, 70 Romeo 37 fighters, 28 Romeo 41 fighters and 10 other fighter planes and 68 reconnaissance planes;

*1,801 artillery pieces, 1,426 heavy and medium mortars, 6,791 trucks and 157 tanks;

*320,000,000 small arms cartridges, 7,514,537 artillery rounds, 1,414 aircraft motors, 1,672 tons of aircraft bombs and 240,747 rifles.

Also, 91 Italian warships and submarines participated during and after the war, sank about 72,800 tons of shipping and lost 38 sailors killed in action. Italy presented a bill for £80,000,000 ($400,000,000) in 1939 prices to the Francoists.

Italian pilots flew 135,265 hours during the war, partook in 5,318 air raids, hit 224 Republican and other ships, engaged in 266 aerial combats reported to have shot down 903 Republican and allied planes and lost around 180 pilots and aircrew killed in action.

Italian-Americans

Italian Americans () are Americans who have full or partial Italian ancestry. The largest concentrations of Italian Americans are in the urban Northeast and industrial Midwestern metropolitan areas, with significant communities also residing ...

such as Vincent Patriarca, along with others in the Italian diaspora

The Italian diaspora (, ) is the large-scale emigration of Italians from Italy.

There were two major Italian diasporas in Italian history. The first diaspora began around 1880, two decades after the Risorgimento, Unification of Italy, and ended ...

, also served in the Aviation Legion during the Italian military intervention.

Germany

Despite the German signing of a non-intervention agreement in September 1936, various forms of aid and military support were given byNazi Germany

Nazi Germany, officially known as the German Reich and later the Greater German Reich, was the German Reich, German state between 1933 and 1945, when Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party controlled the country, transforming it into a Totalit ...

in support of the Nationalists, including the formation of the Condor Legion

The Condor Legion () was a unit of military personnel from the air force and army of Nazi Germany’s Wehrmacht which served with the Nationalist faction during the Spanish Civil War. The legion developed methods of strategic bombing that were ...

as a land and air force, with German efforts to fly the Army of Africa to Mainland Spain

Peninsular Spain is the part of the territory of Spain located within the Iberian Peninsula, thus excluding other parts of Spain: the Canary Islands, the Balearic Islands, Ceuta, Melilla, and several islets and crags off the coast of Morocco kno ...

proving successful in the early stages of the war. Operations gradually expanded to include strike targets, and there was a German contribution to many of the war's battles. The bombing of Guernica

On 26 April 1937, the Basque town of Guernica (''Gernika'' in Basque) was aerially bombed during the Spanish Civil War. It was carried out at the behest of Francisco Franco's rebel Nationalist faction by its allies, the Nazi German Luftwaffe ...

, on 26 April 1937, would be the most controversial event of German involvement, with perhaps 200 to 300 civilians killed. German involvement also included Operation Ursula, a U-boat

U-boats are Submarine#Military, naval submarines operated by Germany, including during the World War I, First and Second World Wars. The term is an Anglicization#Loanwords, anglicized form of the German word , a shortening of (), though the G ...

undertaking and contributions from the Kriegsmarine

The (, ) was the navy of Nazi Germany from 1935 to 1945. It superseded the Imperial German Navy of the German Empire (1871–1918) and the inter-war (1919–1935) of the Weimar Republic. The was one of three official military branch, branche ...

.

The Condor Legion spearheaded many Nationalist victories, particularly in the air dominance from 1937 onward; 300 victories were claimed, as opposed to some 900 claimed by Italian forces. Spain provided a proving ground for German tank tactics as well as aircraft tactics, the latter being only moderately successful. Ultimately, the air superiority, which allowed certain parts of the Legion to excel, would not be replicated because of the unsuccessful 1940 Battle of Britain

The Battle of Britain () was a military campaign of the Second World War, in which the Royal Air Force (RAF) and the Fleet Air Arm (FAA) of the Royal Navy defended the United Kingdom (UK) against large-scale attacks by Nazi Germany's air force ...

. The training provided to Nationalist forces by the Germans would prove at least as valuable as direct actions. Perhaps 56,000 Nationalist soldiers were trained by various German detachments in Spain, which were technically proficient and covered infantry, tanks and anti-tank units; air and anti-aircraft forces; and those trained in naval warfare.

It has been estimated that there were around 16,000 German citizens who fought in the conflict, mostly as pilots, ground crew, artillery and tank crew and military advisers and instructors. About 10,000 Germans were in Spain at the peak, with perhaps as many as 300 of whom being killed in action. German aid to the Nationalists amounted to approximately £43,000,000 ($215,000,000) in 1939 prices. gives a figure of 500 million Reichsmarks. That was broken down in expenditure to 15.5% for salaries and expenses, 21.9% for direct delivery of supplies to Spain and 62.6% for the Condor Legion. No detailed list of German supplies furnished to Spain has been found.

Portugal

António de Oliveira Salazar

António de Oliveira Salazar (28 April 1889 – 27 July 1970) was a Portuguese statesman, academic, and economist who served as Portugal's President of the Council of Ministers of Portugal, President of the Council of Ministers from 1932 to 1 ...

was officially neutral but favoured the Nationalists. Salazar's '' Estado Novo'' held tense relations with the Republic since it held Portuguese dissidents to his regime. Portugal played a critical role in supplying the Nationalists with ammunition and logistical resources.

Direct military involvement involved "semi-official" endorsement by Salazar of a volunteer force of 8,000 to 12,000; the "Viriatos

Viriatos, named after the Lusitanian leader Viriathus, was the generic name given to Portuguese volunteers who fought with the Nationalists in the Spanish Civil War.

" (named after the ''Viriatos Legion'') fought for Franco although never as a national unit. For the whole war, Portugal was instrumental in providing the Nationalists with a vital logistical organisation and by reassuring Franco and his allies that no interference would hinder the supply traffic directed to the Nationalists that crossed the borders of the Iberian countries. The Nationalists even referred to Lisbon as "the port of Castile". In 1938, with Franco's victory increasingly certain, Portugal recognised Franco's regime and soon after the war signed a treaty of friendship and non-aggression pact, the Iberian Pact

The Iberian Pact (''Pacto Ibérico'') or Peninsular Pact, formally the Portuguese–Spanish Treaty of Friendship and Non-Aggression, was a non-aggression pact that was signed at Lisbon, just a few days before the end of the Spanish Civil War, on ...

. Portugal played an important diplomatic role in supporting Franco, including by insisting to the British government that Franco sought to replicate Salazar's ''Estado Novo'', not Mussolini's Fascist Italy or Hitler's Nazi Germany.

Vatican

Among many influential Catholics in Spain, mainly conservative traditionalists and monarchists, the religious persecution was squarely blamed on the Republic. The ensuing outrage was used after the 1936 coup by the propaganda of the rebel faction and readily extended itself. The Catholic Church took the side of the rebels and defined the religious Spaniards who had been persecuted in Republican areas as "martyrs of the faith". It selectively ignored the many believing Catholic Spaniards who remained loyal to the Republic and even those who were later killed during the persecution and the massacres of Republicans. The devout Catholics who supported the Republic included high-ranking officers of theSpanish Republican Army

The Spanish Republican Army () was the main branch of the Spanish Republican Armed Forces, Armed Forces of the Second Spanish Republic between 1931 and 1939.

It became known as People's Army of the Republic (''Ejército Popular de la República'' ...

such as the Republican General Vicente Rojo Lluch

Vicente Rojo Lluch (8 October 1894 – 15 June 1966) was Chief of the General Staff of the Spanish Armed Forces during the Spanish Civil War. He is considered to have been one of the best commanders of the civil war.

Early life

He was the ...

and the Catholic Basque nationalists

Basque nationalism ( ; ; ) is a form of nationalism that asserts that Basques, an ethnic group Indigenous peoples of Europe, indigenous to the western Pyrenees, are a nation and promotes the political unity of the Basques, today scattered bet ...

, who opposed the rebels.

Initially, the Vatican refrained from declaring too openly its support of the rebel side in the war, but it had long allowed high ecclesiastical figures in Spain to do so and to define the conflict as a "Crusade". Throughout the war, however, Francoist propaganda and influential Spanish Catholics labelled the secular Republic as "the enemy of God and the Church" and denounced it by holding it responsible for anticlerical activities, such as shutting down Catholic schools, killing of priests and nuns by exalted mobs and desecrating religious buildings.

Forsaken by the Western European powers, the Republicans depended mainly on Soviet military assistance, which played into the hands of the Nationalists, who portrayed the Republic as a "Marxist" and godless state in Francoist propaganda. Its only other official support was from the anti-Catholic and nominally-revolutionary Mexico

Mexico, officially the United Mexican States, is a country in North America. It is the northernmost country in Latin America, and borders the United States to the north, and Guatemala and Belize to the southeast; while having maritime boundar ...

. By means of its extensive diplomatic network, the Holy See

The Holy See (, ; ), also called the See of Rome, the Petrine See or the Apostolic See, is the central governing body of the Catholic Church and Vatican City. It encompasses the office of the pope as the Bishops in the Catholic Church, bishop ...

used its influence to lobby for the rebels. During an International Art Exhibition in Paris

Paris () is the Capital city, capital and List of communes in France with over 20,000 inhabitants, largest city of France. With an estimated population of 2,048,472 residents in January 2025 in an area of more than , Paris is the List of ci ...

in 1937 in which both the Nationalist and the Republican governments were present, the Holy See allowed the Nationalist pavilion to display its exhibition under the Vatican flag

The flag of Vatican City is the national flag of Vatican City. It was adopted in 1929, the year Pope Pius XI signed the Lateran Treaty with Italy, creating the new independent state of Vatican City.

The flag is a vertical bicolour of yellow and ...

although the Nationalist flag was still not officially recognised. By 1938, Vatican City had already officially recognised the Nationalists, one of the first countries to do so.

Regarding the position of the Holy See during and after the war, Manuel Montero

Manuel "Pantera" Montero (born November 20, 1991, in Buenos Aires)Manuel player prof ...

, a lecturer at the University of the Basque Country

The University of the Basque Country (, ''EHU''; , ''UPV''; officially EHU) is a Spanish public university of the Basque Country (autonomous community), Basque Autonomous Community.

Heir of the University of Deusto, University of Bilbao, initial ...

, commented on 6 May 2007:

Nationalist foreign volunteers

*Volunteer troops from other countries fought with the Nationalists but are not as well known as the Republican volunteers because only a few fought as national units. Among the latter was the 500-strong FrenchJeanne d'Arc

Joan of Arc ( ; ; – 30 May 1431) is a patron saint of France, honored as a defender of the French nation for her role in the siege of Orléans and her insistence on the Coronation of the French monarch, coronation of Charles VII o ...

company of the Spanish Foreign Legion

For centuries, Spain recruited foreign soldiers to its army, forming the foreign regiments () such as the Regiment of Hibernia (formed in 1709 from Irishmen who fled their own country in the wake of the Flight of the Earls and the penal ...

, which was formed mostly from members of the far-right Croix de Feu

The Croix-de-Feu (, ''Cross of Fire'') was a nationalist French league of the interwar period, led by Colonel François de la Rocque (1885–1946). After it was dissolved, as were all other leagues during the Popular Front period (1936–38) ...

.

*Another 11,100 volunteers from countries as diverse as Spanish Guinea

Spanish Guinea () was a set of Insular Region (Equatorial Guinea), insular and Río Muni, continental territories controlled by Spain from 1778 in the Gulf of Guinea and on the Bight of Bonny, in Central Africa. It gained independence in 1968 a ...

, the Philippines

The Philippines, officially the Republic of the Philippines, is an Archipelagic state, archipelagic country in Southeast Asia. Located in the western Pacific Ocean, it consists of List of islands of the Philippines, 7,641 islands, with a tot ...

, the United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

, Brazil

Brazil, officially the Federative Republic of Brazil, is the largest country in South America. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by area, fifth-largest country by area and the List of countries and dependencies by population ...

, Colombia

Colombia, officially the Republic of Colombia, is a country primarily located in South America with Insular region of Colombia, insular regions in North America. The Colombian mainland is bordered by the Caribbean Sea to the north, Venezuel ...

, Uruguay

Uruguay, officially the Oriental Republic of Uruguay, is a country in South America. It shares borders with Argentina to its west and southwest and Brazil to its north and northeast, while bordering the Río de la Plata to the south and the A ...

, Haiti

Haiti, officially the Republic of Haiti, is a country on the island of Hispaniola in the Caribbean Sea, east of Cuba and Jamaica, and south of the Bahamas. It occupies the western three-eighths of the island, which it shares with the Dominican ...

, Mexico

Mexico, officially the United Mexican States, is a country in North America. It is the northernmost country in Latin America, and borders the United States to the north, and Guatemala and Belize to the southeast; while having maritime boundar ...

, Venezuela

Venezuela, officially the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela, is a country on the northern coast of South America, consisting of a continental landmass and many Federal Dependencies of Venezuela, islands and islets in the Caribbean Sea. It com ...

, Puerto Rico

; abbreviated PR), officially the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico, is a Government of Puerto Rico, self-governing Caribbean Geography of Puerto Rico, archipelago and island organized as an Territories of the United States, unincorporated territo ...

, Peru

Peru, officially the Republic of Peru, is a country in western South America. It is bordered in the north by Ecuador and Colombia, in the east by Brazil, in the southeast by Bolivia, in the south by Chile, and in the south and west by the Pac ...

, Paraguay

Paraguay, officially the Republic of Paraguay, is a landlocked country in South America. It is bordered by Argentina to the Argentina–Paraguay border, south and southwest, Brazil to the Brazil–Paraguay border, east and northeast, and Boli ...

, Dominican Republic

The Dominican Republic is a country located on the island of Hispaniola in the Greater Antilles of the Caribbean Sea in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean. It shares a Maritime boundary, maritime border with Puerto Rico to the east and ...

, Nicaragua

Nicaragua, officially the Republic of Nicaragua, is the geographically largest Sovereign state, country in Central America, comprising . With a population of 7,142,529 as of 2024, it is the third-most populous country in Central America aft ...

, El Salvador

El Salvador, officially the Republic of El Salvador, is a country in Central America. It is bordered on the northeast by Honduras, on the northwest by Guatemala, and on the south by the Pacific Ocean. El Salvador's capital and largest city is S ...

, Honduras

Honduras, officially the Republic of Honduras, is a country in Central America. It is bordered to the west by Guatemala, to the southwest by El Salvador, to the southeast by Nicaragua, to the south by the Pacific Ocean at the Gulf of Fonseca, ...

, Ghana

Ghana, officially the Republic of Ghana, is a country in West Africa. It is situated along the Gulf of Guinea and the Atlantic Ocean to the south, and shares borders with Côte d’Ivoire to the west, Burkina Faso to the north, and Togo to t ...

, Bolivia

Bolivia, officially the Plurinational State of Bolivia, is a landlocked country located in central South America. The country features diverse geography, including vast Amazonian plains, tropical lowlands, mountains, the Gran Chaco Province, w ...

, Ecuador

Ecuador, officially the Republic of Ecuador, is a country in northwestern South America, bordered by Colombia on the north, Peru on the east and south, and the Pacific Ocean on the west. It also includes the Galápagos Province which contain ...

, Panama

Panama, officially the Republic of Panama, is a country in Latin America at the southern end of Central America, bordering South America. It is bordered by Costa Rica to the west, Colombia to the southeast, the Caribbean Sea to the north, and ...

, Chile

Chile, officially the Republic of Chile, is a country in western South America. It is the southernmost country in the world and the closest to Antarctica, stretching along a narrow strip of land between the Andes, Andes Mountains and the Paci ...

, Guatemala

Guatemala, officially the Republic of Guatemala, is a country in Central America. It is bordered to the north and west by Mexico, to the northeast by Belize, to the east by Honduras, and to the southeast by El Salvador. It is hydrologically b ...

, French Guiana

French Guiana, or Guyane in French, is an Overseas departments and regions of France, overseas department and region of France located on the northern coast of South America in the Guianas and the West Indies. Bordered by Suriname to the west ...

, Hungary

Hungary is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning much of the Pannonian Basin, Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the south, Croatia and ...

, Romania

Romania is a country located at the crossroads of Central Europe, Central, Eastern Europe, Eastern and Southeast Europe. It borders Ukraine to the north and east, Hungary to the west, Serbia to the southwest, Bulgaria to the south, Moldova to ...

, Greece

Greece, officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. Located on the southern tip of the Balkan peninsula, it shares land borders with Albania to the northwest, North Macedonia and Bulgaria to the north, and Turkey to th ...

, Costa Rica

Costa Rica, officially the Republic of Costa Rica, is a country in Central America. It borders Nicaragua to the north, the Caribbean Sea to the northeast, Panama to the southeast, and the Pacific Ocean to the southwest, as well as Maritime bo ...

, Suriname

Suriname, officially the Republic of Suriname, is a country in northern South America, also considered as part of the Caribbean and the West Indies. It is a developing country with a Human Development Index, high level of human development; i ...

, Turkey

Turkey, officially the Republic of Türkiye, is a country mainly located in Anatolia in West Asia, with a relatively small part called East Thrace in Southeast Europe. It borders the Black Sea to the north; Georgia (country), Georgia, Armen ...

, The Netherlands

, Terminology of the Low Countries, informally Holland, is a country in Northwestern Europe, with Caribbean Netherlands, overseas territories in the Caribbean. It is the largest of the four constituent countries of the Kingdom of the Nether ...

, New Zealand

New Zealand () is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and List of islands of New Zealand, over 600 smaller islands. It is the List of isla ...

and Australia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a country comprising mainland Australia, the mainland of the Australia (continent), Australian continent, the island of Tasmania and list of islands of Australia, numerous smaller isl ...

fought for the Nationalists. In 1937, Franco turned down separate offers of national legions from Belgium

Belgium, officially the Kingdom of Belgium, is a country in Northwestern Europe. Situated in a coastal lowland region known as the Low Countries, it is bordered by the Netherlands to the north, Germany to the east, Luxembourg to the southeas ...

and Greece

Greece, officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. Located on the southern tip of the Balkan peninsula, it shares land borders with Albania to the northwest, North Macedonia and Bulgaria to the north, and Turkey to th ...

, which had been made by foreign sympathisers. Exiled White Russians, including veterans already fighting for Franco, made multiple attempts at creating a separate Russian unit; however, all these motions were reviewed and ultimately rejected.

Ion Moța

Ion I. Moța (5 July 1902 – 13 January 1937) was the deputy leader of the Romanian fascist Legionary Movement (Iron Guard), killed in battle during the Spanish Civil War.

Biography

Son of the nationalist Orthodox priest Ioan Moța, who edit ...

, the Romanian deputy leader of the Legion of the Archangel Michael (or the Iron Guard

The Iron Guard () was a Romanian militant revolutionary nationalism, revolutionary Clerical fascism, religious fascist Political movement, movement and political party founded in 1927 by Corneliu Zelea Codreanu as the Legion of the Archangel M ...

), led a group of seven Legionaries who visited Spain in December 1936 to ally their movement to the Nationalists by presenting a ceremonial sword to survivors of the Siege of Alcazar. In Spain, the Legionaires decided, against the orders that had been given to them in Bucharest

Bucharest ( , ; ) is the capital and largest city of Romania. The metropolis stands on the River Dâmbovița (river), Dâmbovița in south-eastern Romania. Its population is officially estimated at 1.76 million residents within a greater Buc ...

, to join the Spanish Foreign Legion. Within days of joining, Moța and Vasile Marin, another prominent Legionary, were killed on the Madrid Front at Majadahonda

Majadahonda () is a municipality in Spain, situated northwest of Madrid, in the Community of Madrid.

It lies alongside the motorway A6 Madrid- A Coruña.

The Puerta de Hierro university (public) hospital was relocated to Majadahonda from the ...

. After the extravagant and widely publicised funerals of Ion Moța and Vasile Marin, they became a prominent part of the Legion's mythology.

Several hundred Finns volunteered for the war. The volunteers had usually been involved in fascist activism in Finland: Y. P. I. Kaila had been involved in the Mäntsälä rebellion

Mäntsälä () is a municipalities of Finland, municipality in the provinces of Finland, province of Southern Finland, and is part of the Uusimaa regions of Finland, region. It has a population of

() and covers an area of of

which

is water. ...

and joined the Spanish Foreign Legion, as did Kalevi Heikkinen who had been part of the fascist Lapua Movement

The Lapua Movement (, ) was a radical Finnish nationalist, fascist, pro- German and anti-communist political movement founded in and named after the town of Lapua. Led by Vihtori Kosola, it turned towards far-right politics after its founding ...

with Edvard Karvonen. Karvonen opted to join the Condor Legion

The Condor Legion () was a unit of military personnel from the air force and army of Nazi Germany’s Wehrmacht which served with the Nationalist faction during the Spanish Civil War. The legion developed methods of strategic bombing that were ...

in Germany. Some Nationalist volunteers later joined the Finnish SS Battalion like Kaila and Olavi Karpalo. Carl von Haartman

Carl "Goggi" von Haartman (6 July 1897, Helsinki, Finland – 27 August 1980, El Alamillo, Spain) was a Finnish lieutenant colonel, writer, film actor, and film director.

In the late 1920s, Haartman lived in the United States and worked in ...

who was a famous film director also volunteered for the Nationalists.

In Greece

Greece, officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. Located on the southern tip of the Balkan peninsula, it shares land borders with Albania to the northwest, North Macedonia and Bulgaria to the north, and Turkey to th ...

, the dictatorship of Ioannis Metaxas prohibited any Greek involvement in foreign wars. Nevertheless, three Greeks

Greeks or Hellenes (; , ) are an ethnic group and nation native to Greece, Greek Cypriots, Cyprus, Greeks in Albania, southern Albania, Greeks in Turkey#History, Anatolia, parts of Greeks in Italy, Italy and Egyptian Greeks, Egypt, and to a l ...

are known to have enlisted in Francoist military forces, joining the Spanish Foreign Legion

For centuries, Spain recruited foreign soldiers to its army, forming the foreign regiments () such as the Regiment of Hibernia (formed in 1709 from Irishmen who fled their own country in the wake of the Flight of the Earls and the penal ...

. Additionally, two Greeks born in Spain (one the son of a former Greek consul in Mallorca) were also recruited by Francoist agents for espionage.

The Norwegian writer Per Imerslund

Nils Per Imerslund (9 May 1912 – 7 December 1943), born in Kristiania, Norway, was one of the most prominent figures of the Nazi scene in pre-World War II Norway. He first gained prominence at home and abroad with the publication in 1936 of his ...

fought with the Falange militia in the war in 1937.

Outside of Ireland (see below), fighting for the Nationalist cause seems not to have held much appeal in the English-speaking world, according to historian Hugh Thomas. British journalist Peter Kemp was among the few who did, serving as an officer with a Carlist

Carlism (; ; ; ) is a Traditionalism (Spain), Traditionalist and Legitimist political movement in Spain aimed at establishing an alternative branch of the Bourbon dynasty, one descended from Infante Carlos María Isidro of Spain, Don Carlos, ...

battalion for the Nationalists and was wounded. Thomas Krock, son of the famed American journalist Arthur Krock

Arthur Bernard Krock (November 16, 1886 – April 12, 1974) was a Pulitzer Prize-winning American journalist. He became known as the "Dean of Washington newsmen" in a career that spanned the tenure of 11 United States presidents.

Early life and ...

, was among the few Americans who fought for the Nationalists.

A landlord

A landlord is the owner of property such as a house, apartment, condominium, land, or real estate that is rented or leased to an individual or business, known as a tenant (also called a ''lessee'' or ''renter''). The term landlord appli ...

from Söke

Söke is a municipality and district of Aydın Province, Turkey. Its area is 1,064 km2, and its population is 123,301 (2022). It is the largest district of Aydın Province by area. Söke is 54 km (34 miles) south-west of the city of Ayd� ...

, Turkey

Turkey, officially the Republic of Türkiye, is a country mainly located in Anatolia in West Asia, with a relatively small part called East Thrace in Southeast Europe. It borders the Black Sea to the north; Georgia (country), Georgia, Armen ...

named Fahri Tanman volunteered for the nationalist forces.

International

Anticlericalism and the murder of 4,000 clergy and many more nuns by the Republicans made many Catholic writers and intellectuals cast their lot with Franco, includingEvelyn Waugh

Arthur Evelyn St. John Waugh (; 28 October 1903 – 10 April 1966) was an English writer of novels, biographies, and travel books; he was also a prolific journalist and book reviewer. His most famous works include the early satires ''Decli ...

, Carl Schmitt

Carl Schmitt (11 July 1888 – 7 April 1985) was a German jurist, author, and political theorist.

Schmitt wrote extensively about the effective wielding of political power. An authoritarian conservative theorist, he was noted as a critic of ...

, Hilaire Belloc

Joseph Hilaire Pierre René Belloc ( ; ; 27 July 187016 July 1953) was a French-English writer, politician, and historian. Belloc was also an orator, poet, sailor, satirist, writer of letters, soldier, and political activist. His Catholic fait ...

, Roy Campbell, Giovanni Papini

Giovanni Papini (9 January 18818 July 1956) was an Italian journalist, essayist, novelist, short story writer, poet, literary critic, and Italian philosophy, philosopher. A controversial literary figure of the early and mid-twentieth century, he ...

, Paul Claudel

Paul Claudel (; 6 August 1868 – 23 February 1955) was a French poet, dramatist and diplomat, and the younger brother of the sculptor Camille Claudel. He was most famous for his verse dramas, which often convey his devout Catholicism.

Early lif ...

, J. R. R. Tolkien

John Ronald Reuel Tolkien (, 3 January 1892 – 2 September 1973) was an English writer and philologist. He was the author of the high fantasy works ''The Hobbit'' and ''The Lord of the Rings''.

From 1925 to 1945, Tolkien was the Rawlinson ...

and those associated with the Action Française

''Action Française'' (, AF; ) is a French far-right monarchist and nationalist political movement. The name was also given to a journal associated with the movement, '' L'Action Française'', sold by its own youth organization, the Camelot ...

. Others, such as Jacques Maritain

Jacques Maritain (; 18 November 1882 – 28 April 1973) was a French Catholic philosopher. Raised as a Protestant, he was agnostic before converting to Catholicism in 1906. An author of more than 60 books, he helped to revive Thomas Aqui ...

, François Mauriac

François Charles Mauriac (; ; 11 October 1885 – 1 September 1970) was a French novelist, dramatist, critic, poet, and journalist, a member of the'' Académie française'' (from 1933), and laureate of the 1952 Nobel Prize in Literature, Nobel Pr ...

and Georges Bernanos

Louis Émile Clément Georges Bernanos (; 20 February 1888 – 5 July 1948) was a French author, and a soldier in World War I. A Catholic with monarchist leanings, he was critical of elitist thought and was opposed to what he identified as d ...

, initially supported Franco but later grew disenchanted with both sides.

Many artists with right-wing sympathies, such as Ezra Pound

Ezra Weston Loomis Pound (30 October 1885 – 1 November 1972) was an List of poets from the United States, American poet and critic, a major figure in the early modernist poetry movement, and a Collaboration with Nazi Germany and Fascist Ita ...

, Gertrude Stein

Gertrude Stein (February 3, 1874 – July 27, 1946) was an American novelist, poet, playwright, and art collector. Born in Allegheny, Pennsylvania (now part of Pittsburgh), and raised in Oakland, California, Stein moved to Paris in 1903, and ...

, Wyndham Lewis

Percy Wyndham Lewis (18 November 1882 – 7 March 1957) was a British writer, painter and critic. He was a co-founder of the Vorticist movement in art and edited ''Blast (British magazine), Blast'', the literary magazine of the Vorticists.

His ...

, Robert Brasillach

Robert Brasillach (; 31 March 1909 – 6 February 1945) was a French author and journalist. He was the editor of '' Je suis partout'', a nationalist newspaper which advocated fascist movements and supported Jacques Doriot. After the liberation o ...

and Pierre Drieu La Rochelle

Pierre Eugène Drieu La Rochelle (; 3 January 1893 – 15 March 1945) was a French writer of novels, short stories, and political essays. He was born, lived and died in Paris. Drieu La Rochelle became a proponent of French fascism in the 1930 ...

voiced support for the Nationalists. Brasillach collaborated with Maurice Bardèche

Maurice Bardèche (1 October 1907 – 30 July 1998) was a French art critic and journalist, better known as one of the leading exponents of neo-fascism and Holocaust denial in post–World War II Europe.

Bardèche was also the brother-in-law ...

on his own ''Histoire de la Guerre d'Espagne'', and the protagonist in Drieu La Rochelle's novel ''Gille'' travels to Spain to fight for the Falange. Lewis's ''The Revenge for Love'' (begun 1934) details the anarchist-communist conflict in the years preceding the war; though it is not a Spanish Civil War novel, it is often mistaken for one.

Even though the Mexican government supported the Republicans, most of the Mexican population, such as the peasant Cristeros

The Cristero War (), also known as the Cristero Rebellion or , was a widespread struggle in central and western Mexico from 3 August 1926 to 21 June 1929 in response to the implementation of secularist and anticlerical articles of the 1917 Con ...

, preferred Franco and the Nationalists. Mexico had suffered from the 1926–1929 Cristero War

The Cristero War (), also known as the Cristero Rebellion or , was a widespread struggle in central and western Mexico from 3 August 1926 to 21 June 1929 in response to the implementation of secularism, secularist and anti-clericalism, anticler ...

in which President Plutarco Elías Calles

Plutarco Elías Calles (born Francisco Plutarco Elías Campuzano; 25 September 1877 – 19 October 1945) was a Mexican politician and military officer who served as the 47th President of Mexico from 1924 to 1928. After the assassination of Ál ...

tried to enforce militant state atheism

State atheism or atheist state is the incorporation of hard atheism or non-theism into Forms of government, political regimes. It is considered the opposite of theocracy and may also refer to large-scale secularization attempts by governments ...

; it led to the deaths of many people as well as the suppression of popular religious Mexican celebrations.Irish volunteers

Around 700 ofEoin O'Duffy

Eoin O'Duffy (born Owen Duffy; 28 January 1890 – 30 November 1944) was an Irish revolutionary, soldier, police commissioner, politician and fascist. O'Duffy was the leader of the Monaghan Brigade of the Irish Republican Army (IRA) and a promin ...