Southern Literature on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Southern United States literature consists of

Southern United States literature consists of

"Southern Literature: Women Writers"

. Accessed Feb. 4, 2007. However, in recent decades, the scholarship of the New Southern Studies has decentralized these conventional tropes in favor of a more geographically, politically, and ideologically expansive "South" or "Souths".Jon Smith and Deborah Coh

"Look Away! The U.S. South in New World Studies"

/ref>

* The ''

Beginnings of Southern Literature

* ''The History of Southern Literature'' by Louis Rubin. Louisiana State University Press, 1991. * Louis D. Rubin Jr., "From Combray to Ithaca; or, The 'Southernness' of Southern Literature," in The Mockingbird in the Gum Tree (Louisiana State University Press, 1991) * (Explores the overall issues surrounding what makes for southern literature) * * * * * * . (Explanation of what constitutes "good" southern writing) * Patricia Yeager (2000).

Dirt and Desire: Reconstructing Southern Women's Writing, 1930-1990

'. University of Chicago Press. .

''Turning South Again: Re-Thinking Modernism/Re-Reading Booker T''.

Duke University Press. . *

Article exploring 2002 changes in southern literature. * ''The New Dictionary of Cultural Literacy, Third Edition: What Every American Needs to Know'' Edited by James Trefil, Joseph F. Kett, and E. D. Hirsch. Houghton Mifflin, 2002. * * * Tara McPherson (2003).

Reconstructing Dixie: Race, Gender, and Nostalgia in the Imagined South

'. Duke University Press. . *

Genres of Southern Literature

by Lucinda MacKethan. Southern Spaces, Feb. 2004. * Jon Smith; Deborah Cohn, eds. (2004).

Look Away! The U.S. South in New World Studies

'. Duke University Press. . * Leigh Anne Duck (2006).

The Nation's Region: Southern Modernism, Segregation, and U.S. Nationalism

'. University of Georgia Press. . * Riché Richardson (2007).

Black Masculinity and the U.S. South: From Uncle Tom to Gangsta

'. University of Georgia Press. . *Anderson, Eric Gary.

On Native Ground: Indigenous Presences and Countercolonial Strategies in Southern Narratives of Captivity, Removal, and Repossession

''Southern Spaces.'' August 9, 2007. *Leigh Anne Duck (July 2008). " Southern Nonidentity." ''Safundi: The Journal of South African and American Studies'', 9 (3): 319–330. *Harilaos Stecopoulos (2008).

Reconstructing the World: Southern Fictions and U.S. Imperialisms, 1898-1976

'. Cornell University Press. . * * Scott Romine (2008).

The Real South: Southern Narrative in the Age of Cultural Reproduction

'. Louisiana State University Press. . *Jennifer Rae Greeson (2010).

Our South: Geographic Fantasy and the Rise of National Literature

'. Harvard University Press. . * Thadious M. Davis (2011).

Southscapes: Geographies of Race, Region, and Literature

'. University of North Carolina Press. . * Deborah Barker; Kathryn McKee, eds. (2011).

American Cinema and the Southern Imaginary

'. University of Georgia Press. . * * Melanie Benson Taylor (2012).

Reconstructing the Native South: American Indian Literature and the Lost Cause

'. University of Georgia Press. . * Jay Watson (2012).

Reading for the Body: The Recalcitrant Materiality of Southern Fiction, 1893-1985

'. University of Georgia Press. . * * Keith Cartwright (2013).

Sacral Grooves, Limbo Gateways: Travels in Deep Southern Time, Circum-Caribbean Space, Afro-Creole Authority

'. University of Georgia Press. . * Matthew Pratt Guterl (2013).

American Mediterranean: Southern Slaveholders in the Age of Emancipation

'. Harvard University Press. . * Claudia Milian (2013).

Latining America: Black-Brown Passages and the Coloring of Latino/a Studies

'. University of Georgia Press. . * Jon Smith (2013).

Finding Purple America: The South and the Future of American Cultural Studies

'. University of Georgia Press. . * * * Eric Gary Anderson; Taylor Hagood; Daniel Cross Turner, eds. (2015)

''Undead Souths: The Gothic and Beyond in Southern Literature and Culture''

Louisiana State University Press. . * Martyn Bone; Brian Ward; William A. Link, eds. (2015). ''Creating and Consuming the American South''. University Press of Florida. . * * * Jennifer Rae Greeson; Scott Romine, eds. (2016).

Keywords for Southern Studies

'. University of Georgia Press. .

Library of Southern Literature, University of North Carolina

American Southern literature pre-1929.

* (A checklist of scholarship on writers associated with the American South; directory arranged by period: colonial, contemporary, etc. Sponsored by Mississippi Quarterly. Ceased publication. )

Southern Poetry from Holman Prison Death Row Inmate Darrell Grayson

*

Poets in Place

" at ''Southern Spaces''. *

History of Southern Literature online publishing.

Since 1995 the American South has relied on the Dead Mule School of Southern Literature for quality fiction, poetry and more. {{DEFAULTSORT:Southern Literature Culture of the Southern United States American literary movements

Southern United States literature consists of

Southern United States literature consists of American literature

American literature is literature written or produced in the United States of America and in the British colonies that preceded it. The American literary tradition is part of the broader tradition of English-language literature, but also ...

written about the Southern United States

The Southern United States (sometimes Dixie, also referred to as the Southern States, the American South, the Southland, Dixieland, or simply the South) is List of regions of the United States, census regions defined by the United States Cens ...

or by writers from the region. Literature written about the American South first began during the colonial era, and developed significantly during and after the period of slavery in the United States

The legal institution of human chattel slavery, comprising the enslavement primarily of List of ethnic groups of Africa, Africans and African Americans, was prevalent in the United States of America from its founding in 1776 until 1865 ...

. Traditional historiography of Southern United States literature emphasized a unifying history of the region; the significance of family in the South's culture, a sense of community and the role of the individual, justice, the dominance of Christianity

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion, which states that Jesus in Christianity, Jesus is the Son of God (Christianity), Son of God and Resurrection of Jesus, rose from the dead after his Crucifixion of Jesus, crucifixion, whose ...

and the positive and negative impacts of religion, racial tensions, social class

A social class or social stratum is a grouping of people into a set of Dominance hierarchy, hierarchical social categories, the most common being the working class and the Bourgeoisie, capitalist class. Membership of a social class can for exam ...

and the usage of local dialects.Patricia Evan"Southern Literature: Women Writers"

. Accessed Feb. 4, 2007. However, in recent decades, the scholarship of the New Southern Studies has decentralized these conventional tropes in favor of a more geographically, politically, and ideologically expansive "South" or "Souths".Jon Smith and Deborah Coh

"Look Away! The U.S. South in New World Studies"

/ref>

Overview

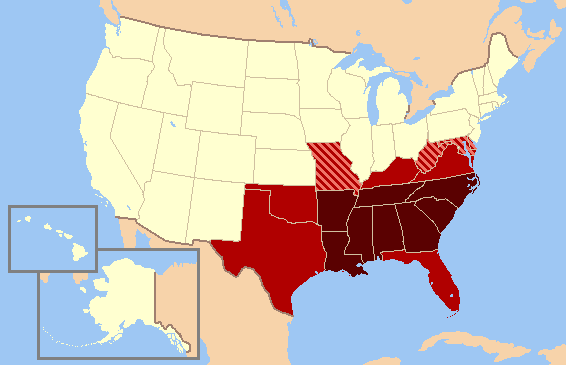

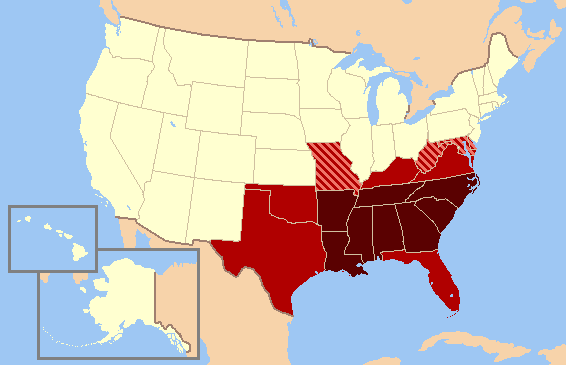

In its simplest form, Southern literature consists of writing about theAmerican South

The Southern United States (sometimes Dixie, also referred to as the Southern States, the American South, the Southland, Dixieland, or simply the South) is census regions United States Census Bureau. It is between the Atlantic Ocean and the ...

. Often, "the South" is defined, for historical as well as geographical reasons, as the states of South Carolina

South Carolina ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It borders North Carolina to the north and northeast, the Atlantic Ocean to the southeast, and Georgia (U.S. state), Georg ...

, Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the South Caucasus

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the southeastern United States

Georgia may also refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Georgia (name), a list of pe ...

, Florida

Florida ( ; ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It borders the Gulf of Mexico to the west, Alabama to the northwest, Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia to the north, the Atlantic ...

, Alabama

Alabama ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern and Deep South, Deep Southern regions of the United States. It borders Tennessee to the north, Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia to the east, Florida and the Gu ...

, North Carolina

North Carolina ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It is bordered by Virginia to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the east, South Carolina to the south, Georgia (U.S. stat ...

, Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern and Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic regions of the United States between the East Coast of the United States ...

, Tennessee

Tennessee (, ), officially the State of Tennessee, is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It borders Kentucky to the north, Virginia to the northeast, North Carolina t ...

, Mississippi

Mississippi ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern and Deep South regions of the United States. It borders Tennessee to the north, Alabama to the east, the Gulf of Mexico to the south, Louisiana to the s ...

, Louisiana

Louisiana ( ; ; ) is a state in the Deep South and South Central regions of the United States. It borders Texas to the west, Arkansas to the north, and Mississippi to the east. Of the 50 U.S. states, it ranks 31st in area and 25 ...

, Texas

Texas ( , ; or ) is the most populous U.S. state, state in the South Central United States, South Central region of the United States. It borders Louisiana to the east, Arkansas to the northeast, Oklahoma to the north, New Mexico to the we ...

, Oklahoma

Oklahoma ( ; Choctaw language, Choctaw: , ) is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the South Central United States, South Central region of the United States. It borders Texas to the south and west, Kansas to the north, Missouri to the northea ...

, Kentucky

Kentucky (, ), officially the Commonwealth of Kentucky, is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It borders Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio to the north, West Virginia to the ...

, West Virginia

West Virginia is a mountainous U.S. state, state in the Southern United States, Southern and Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic regions of the United States.The United States Census Bureau, Census Bureau and the Association of American ...

and Arkansas

Arkansas ( ) is a landlocked state in the West South Central region of the Southern United States. It borders Missouri to the north, Tennessee and Mississippi to the east, Louisiana to the south, Texas to the southwest, and Oklahoma ...

. Pre-Civil War definitions of the South often included Missouri

Missouri (''see #Etymology and pronunciation, pronunciation'') is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. Ranking List of U.S. states and territories by area, 21st in land area, it border ...

, Maryland

Maryland ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. It borders the states of Virginia to its south, West Virginia to its west, Pennsylvania to its north, and Delaware to its east ...

, and Delaware

Delaware ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic and South Atlantic states, South Atlantic regions of the United States. It borders Maryland to its south and west, Pennsylvania to its north, New Jersey ...

as well. However, "the South" is also a social, political, economic, and cultural construct that transcends these geographical boundaries.

Southern literature has been described by scholars as occupying a liminal space within wider American culture. After the American Revolution

The American Revolution (1765–1783) was a colonial rebellion and war of independence in which the Thirteen Colonies broke from British America, British rule to form the United States of America. The revolution culminated in the American ...

, writers in the U.S. from outside the South frequently othered Southern culture, in particular slavery

Slavery is the ownership of a person as property, especially in regards to their labour. Slavery typically involves compulsory work, with the slave's location of work and residence dictated by the party that holds them in bondage. Enslavemen ...

, as a method of " tandingapart from the imperial world order". These negative portrayals of the American South eventually diminished after the abolition of slavery in the U.S., particularly during a period after the Spanish–American War

The Spanish–American War (April 21 – August 13, 1898) was fought between Restoration (Spain), Spain and the United States in 1898. It began with the sinking of the USS Maine (1889), USS ''Maine'' in Havana Harbor in Cuba, and resulted in the ...

when many Americans began to re-evaluate their anti-imperialistic views and support for imperialism

Imperialism is the maintaining and extending of Power (international relations), power over foreign nations, particularly through expansionism, employing both hard power (military and economic power) and soft power (diplomatic power and cultura ...

grew. Changing historiographical trends have placed racism in the American South as emblematic of, rather than an exception to, U.S. racism as a whole.

In addition to the geographical component of Southern literature, certain themes have appeared because of the similar histories of the Southern states in regard to American slavery, the Civil War

A civil war is a war between organized groups within the same Sovereign state, state (or country). The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies.J ...

, and the reconstruction era

The Reconstruction era was a period in History of the United States, US history that followed the American Civil War (1861-65) and was dominated by the legal, social, and political challenges of the Abolitionism in the United States, abol ...

. The conservative culture in the American South has also produced a strong focus within Southern literature on the significance of family, religion, community in one's personal and social life, the use of Southern dialects, and a strong sense of "place." The South's troubled history with racial

Race is a categorization of humans based on shared physical or social qualities into groups generally viewed as distinct within a given society. The term came into common usage during the 16th century, when it was used to refer to groups of va ...

issues also continually appears in its literature.

Despite these common themes, there is debate as to what makes a literary work "Southern." For example, Mark Twain

Samuel Langhorne Clemens (November 30, 1835 – April 21, 1910), known by the pen name Mark Twain, was an American writer, humorist, and essayist. He was praised as the "greatest humorist the United States has produced," with William Fau ...

, a Missourian, defined the characteristics that many people associate with Southern writing in his novel

A novel is an extended work of narrative fiction usually written in prose and published as a book. The word derives from the for 'new', 'news', or 'short story (of something new)', itself from the , a singular noun use of the neuter plural of ...

''Adventures of Huckleberry Finn

''Adventures of Huckleberry Finn'' is a picaresque novel by American author Mark Twain that was first published in the United Kingdom in December 1884 and in the United States in February 1885.

Commonly named among the Great American Novels, th ...

''. Truman Capote

Truman Garcia Capote ( ; born Truman Streckfus Persons; September 30, 1924 – August 25, 1984) was an American novelist, screenwriter, playwright, and actor. Several of his short stories, novels, and plays have been praised as literary classics ...

, born and raised in the Deep South

The Deep South or the Lower South is a cultural and geographic subregion of the Southern United States. The term is used to describe the states which were most economically dependent on Plantation complexes in the Southern United States, plant ...

, is best known for his novel ''In Cold Blood'', a piece with none of the characteristics associated with "southern writing." Other Southern writers, such as popular authors Anne Rice and John Grisham

John Ray Grisham Jr. (; born February 8, 1955) is an American novelist, lawyer, and former politician, known for his best-selling legal thrillers. According to the Academy of Achievement, American Academy of Achievement, Grisham has written 37 ...

, rarely write about traditional Southern literary issues. John Berendt, who wrote the popular '' Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil'', is not a Southerner. In addition, some famous Southern writers moved to the Northern U.S. So while geography is a factor, the geographical location of the author is not ''the'' defining factor in Southern writing. Some suggest that "Southern" authors write in their individual way due to the impact of the strict cultural decorum in the South and the need to break away from it.

History

Early and antebellum literature

The earliest literature written in what would become the American South dates back to the colonial era, in particularVirginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern and Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic regions of the United States between the East Coast of the United States ...

; the explorer John Smith wrote an account of the founding of the colonial settlement of Jamestown in the early 17th century, while planter William Byrd II kept a diary of his day-to-day affairs during the early 18th century. Both sets of recollections are critical documents in early Southern history.

After the American Revolution

The American Revolution (1765–1783) was a colonial rebellion and war of independence in which the Thirteen Colonies broke from British America, British rule to form the United States of America. The revolution culminated in the American ...

, in the early 19th century, the expansion of Southern plantations fueled by slave labor began to distinguish Southern society and culture more clearly from the other states of the young nations. During this antebellum period

The ''Antebellum'' South era (from ) was a period in the history of the Southern United States that extended from the conclusion of the War of 1812 to the start of the American Civil War in 1861. This era was marked by the prevalent practi ...

, South Carolina

South Carolina ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It borders North Carolina to the north and northeast, the Atlantic Ocean to the southeast, and Georgia (U.S. state), Georg ...

, and particularly the city of Charleston, rivaled and perhaps surpassed Virginia as a literary community. Writing in Charleston, the lawyer and essayist Hugh Swinton Legare, the poets Paul Hamilton Hayne and Henry Timrod, and the novelist William Gilmore Simms composed some of the most important works in antebellum Southern literature. In Virginia, John Pendleton Kennedy gave an account of Virginia plantation life in his 1832 book ''Swallow Barn.''

Simms was a particularly significant figure, perhaps the most prominent Southern author before the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and the Confederate States of A ...

. His novels of frontier life and the American revolution celebrated the history of South Carolina. Like James Fenimore Cooper, Simms was strongly influenced by Scottish author Walter Scott

Sir Walter Scott, 1st Baronet (15 August 1771 – 21 September 1832), was a Scottish novelist, poet and historian. Many of his works remain classics of European literature, European and Scottish literature, notably the novels ''Ivanhoe'' (18 ...

, and his works bore the imprint of Scott's romanticism

Romanticism (also known as the Romantic movement or Romantic era) was an artistic and intellectual movement that originated in Europe towards the end of the 18th century. The purpose of the movement was to advocate for the importance of subjec ...

. In '' The Yemassee'', ''The Kinsmen'', and the anti-''Uncle Tom's Cabin'' novel '' The Sword and the Distaff'', Simms presented idealized portraits of slavery and Southern life. While popular and well regarded in South Carolina—and highly praised by such critics as Edgar Allan Poe

Edgar Allan Poe (; January 19, 1809 – October 7, 1849) was an American writer, poet, editor, and literary critic who is best known for his poetry and short stories, particularly his tales involving mystery and the macabre. He is widely re ...

—Simms never gained a large national audience.

In Virginia, George Tucker produced in 1824 the first fiction of Virginia colonial life with ''The Valley of Shenandoah''. He followed in 1827 with one of the country's first science fictions, '' A Voyage to the Moon: With Some Account of the Manners and Customs, Science and Philosophy, of the People of Morosofia, and Other Lunarians''. Tucker was the first Professor of Moral Philosophy at the University of Virginia. In 1836 Tucker published the first comprehensive biography of Thomas Jefferson - ''The Life of Thomas Jefferson, Third President of the United States''. Some critics also regard Poe as a Southern author—he was raised in Richmond, attended the University of Virginia, and edited the '' Southern Literary Messenger'' from 1835 to 1837. Yet in his poetry and fiction Poe rarely took up distinctly Southern themes or subjects; his status as a "Southern" writer remains ambiguous.

In the Chesapeake region, meanwhile, antebellum authors of enduring interest include John Pendleton Kennedy, whose novel '' Swallow Barn'' offered a colorful sketch of Virginia plantation life; and Nathaniel Beverley Tucker, whose 1836 work '' The Partisan Leader'' foretold the secession of the Southern states, and imagined a guerrilla war in Virginia between federal and secessionist armies.

Not all noteworthy Southern authors during this period were white. Frederick Douglass

Frederick Douglass (born Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey, February 14, 1818 – February 20, 1895) was an American social reformer, Abolitionism in the United States, abolitionist, orator, writer, and statesman. He was the most impor ...

's ''Narrative

A narrative, story, or tale is any account of a series of related events or experiences, whether non-fictional (memoir, biography, news report, documentary, travel literature, travelogue, etc.) or fictional (fairy tale, fable, legend, thriller ...

'' is perhaps the most famous first-person account of black slavery in the antebellum South. Harriet Jacobs, meanwhile, recounted her experiences in bondage in North Carolina in Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl. And another Southern-born ex-slave, William Wells Brown, wrote ''Clotel; or, The President's Daughter''—widely believed to be the first novel ever published by an African-American

African Americans, also known as Black Americans and formerly also called Afro-Americans, are an American racial and ethnic group that consists of Americans who have total or partial ancestry from any of the Black racial groups of Africa. ...

. The book depicts the life of its title character, a daughter of Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (, 1743July 4, 1826) was an American Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father and the third president of the United States from 1801 to 1809. He was the primary author of the United States Declaration of Indepe ...

and his black mistress, and her struggles under slavery.

The "Lost Cause" years

In the second half of the 19th century, the South lost the Civil War and suffered through what many white Southerners considered a harsh occupation (calledReconstruction

Reconstruction may refer to:

Politics, history, and sociology

*Reconstruction (law), the transfer of a company's (or several companies') business to a new company

*''Perestroika'' (Russian for "reconstruction"), a late 20th century Soviet Union ...

). In place of the anti-Tom literature came poetry and novels about the "Lost Cause of the Confederacy

The Lost Cause of the Confederacy, known simply as the Lost Cause, is an American pseudohistory, pseudohistorical and historical negationist myth that argues the cause of the Confederate States of America, Confederate States during the America ...

." This nostalgic literature began to appear almost immediately after the war ended; '' The Conquered Banner'' was published on June 24, 1865. These writers idealized the defeated South and its lost culture. Prominent writers with this point of view included poets Henry Timrod, Daniel B. Lucas, and Abram Joseph Ryan

Abram Joseph Ryan (born Matthew Abraham Ryan; February 5, 1838 – April 22, 1886) was an Catholic Church in the United States, American Catholic poet, priest, journalist, orator, and former Congregation of the Mission, Vincentian. Historians disa ...

, and fiction writer Thomas Nelson Page. Others, like African American

African Americans, also known as Black Americans and formerly also called Afro-Americans, are an Race and ethnicity in the United States, American racial and ethnic group that consists of Americans who have total or partial ancestry from an ...

writer Charles W. Chesnutt, dismissed this nostalgia by pointing out the racism

Racism is the belief that groups of humans possess different behavioral traits corresponding to inherited attributes and can be divided based on the superiority of one Race (human categorization), race or ethnicity over another. It may also me ...

and exploitation of blacks that happened during this time period in the South.

in 1856 George Tucker completed his final multivolume work in his ''History of the United States, From Their Colonization to the End of the 26th Congress, in 1841''.

In 1884, Mark Twain

Samuel Langhorne Clemens (November 30, 1835 – April 21, 1910), known by the pen name Mark Twain, was an American writer, humorist, and essayist. He was praised as the "greatest humorist the United States has produced," with William Fau ...

published what is arguably the most influential Southern novel of the 19th century, ''Adventures of Huckleberry Finn

''Adventures of Huckleberry Finn'' is a picaresque novel by American author Mark Twain that was first published in the United Kingdom in December 1884 and in the United States in February 1885.

Commonly named among the Great American Novels, th ...

''. Ernest Hemingway

Ernest Miller Hemingway ( ; July 21, 1899 – July 2, 1961) was an American novelist, short-story writer and journalist. Known for an economical, understated style that influenced later 20th-century writers, he has been romanticized fo ...

said of the novel, "All modern American literature comes from one book by Mark Twain called ''Huckleberry Finn''." This statement applies even more to Southern literature because of the novel's frank dealings with issues such as race and violence.

Kate Chopin was another central figure in post-Civil War Southern literature. Focusing her writing largely on the French Creole communities of Louisiana, Chopin established her literary reputation with the short story collections '' Bayou Folk'' (1894) and '' A Night in Acadie'' (1897). These stories offered not only a sociological portrait of a specific Southern culture but also furthered the legacy of the American short story as a uniquely vital and complex narrative genre. But it was with the publication of her second and final novel '' The Awakening'' (1899) that she gained notoriety of a different sort. The novel shocked audiences with its frank and unsentimental portrayal of female sexuality and psychology. It paved the way for the Southern novel as both a serious genre (based in the realism that had dominated the Western novel since Balzac) and one that tackled the complex and untidy emotional lives of its characters. Today she is widely regarded as not only one of the most important female writers in American literature, but one of the most important chroniclers of the post-Civil War South and one of the first writers to treat the female experience with complexity and without condescension.

During the first half of the 20th century, the lawyer, politician, minister, orator, actor, and author Thomas Dixon, Jr., wrote a number of novels, plays, sermons, and non-fiction pieces which were very popular with the general public all over the USA. Dixon's greatest fame came from a trilogy of novels about Reconstruction

Reconstruction may refer to:

Politics, history, and sociology

*Reconstruction (law), the transfer of a company's (or several companies') business to a new company

*''Perestroika'' (Russian for "reconstruction"), a late 20th century Soviet Union ...

, one of which was entitled '' The Clansman'' (1905), a book and then a wildly successful play, which would eventually become the inspiration for D. W. Griffith's highly controversial 1915 film ''The Birth of a Nation

''The Birth of a Nation'' is a 1915 American Silent film, silent Epic film, epic Drama (film and television), drama film directed by D. W. Griffith and starring Lillian Gish. The screenplay is adapted from Thomas Dixon Jr.'s 1905 novel and ...

''. Overall Dixon wrote 22 novels, numerous plays and film scripts, Christian sermons, and some non-fiction works.

The Southern Renaissance

In the 1920s and 1930s, a renaissance in Southern literature began with the appearance of writers such asWilliam Faulkner

William Cuthbert Faulkner (; September 25, 1897 – July 6, 1962) was an American writer. He is best known for William Faulkner bibliography, his novels and short stories set in the fictional Yoknapatawpha County, Mississippi, a stand-in fo ...

, Katherine Anne Porter

Katherine Anne Porter (May 15, 1890 – September 18, 1980) was an American journalist, essayist, short story writer, novelist, poet, and political activist. Her 1962 novel '' Ship of Fools'' was the best-selling novel in the United States that y ...

, Caroline Gordon, Allen Tate, Thomas Wolfe

Thomas Clayton Wolfe (October 3, 1900 – September 15, 1938) was an American novelist and short story writer. He is known largely for his first novel, '' Look Homeward, Angel'' (1929), and for the short fiction that appeared during the last ye ...

, Robert Penn Warren

Robert Penn Warren (April 24, 1905 – September 15, 1989) was an American poet, novelist, literary critic and professor at Yale University. He was one of the founders of New Criticism. He was also a charter member of the Fellowship of Southern ...

, and Tennessee Williams

Thomas Lanier Williams III (March 26, 1911 – February 25, 1983), known by his pen name Tennessee Williams, was an American playwright and screenwriter. Along with contemporaries Eugene O'Neill and Arthur Miller, he is considered among the three ...

, among others. Because of the distance the Southern Renaissance authors had from the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and the Confederate States of A ...

and slavery

Slavery is the ownership of a person as property, especially in regards to their labour. Slavery typically involves compulsory work, with the slave's location of work and residence dictated by the party that holds them in bondage. Enslavemen ...

, they were more objective in their writings about the South. During the 1920s, Southern poetry thrived under the Vanderbilt "Fugitives

A fugitive or runaway is a person who is fleeing from custody, whether it be from jail, a government arrest, government or non-government questioning, vigilante violence, or outraged private individuals. A fugitive from justice, also known ...

". In nonfiction, H.L. Mencken's popularity increased nationwide as he shocked and astounded readers with his satiric writing highlighting the inability of the South to produce anything of cultural value. In reaction to Mencken's essay, "The Sahara of the Bozart," the Southern Agrarians (also based mostly around Vanderbilt) called for a return to the South's agrarian past and bemoaned the rise of Southern industrialism and urbanization. They noted that creativity and industrialism were not compatible and desired the return to a lifestyle that would afford the Southerner leisure (a quality the Agrarians most felt conducive to creativity). Writers like Faulkner, who won the Nobel Prize in Literature

The Nobel Prize in Literature, here meaning ''for'' Literature (), is a Swedish literature prize that is awarded annually, since 1901, to an author from any country who has, in the words of the will of Swedish industrialist Alfred Nobel, "in ...

for 1949, also brought new techniques such as stream of consciousness

In literary criticism, stream of consciousness is a narrative mode or method that attempts "to depict the multitudinous thoughts and feelings which pass through the mind" of a narrator. It is usually in the form of an interior monologue which ...

and complex narrative techniques to their writings. For instance, his novel '' As I Lay Dying'' is told by changing narrators ranging from the deceased Addie to her young son.

The late 1930s also saw the publication of one of the best-known Southern novels, ''Gone with the Wind Gone with the Wind most often refers to:

* Gone with the Wind (novel), ''Gone with the Wind'' (novel), a 1936 novel by Margaret Mitchell

* Gone with the Wind (film), ''Gone with the Wind'' (film), the 1939 adaptation of the novel

Gone with the Wind ...

'' by Margaret Mitchell

Margaret Munnerlyn Mitchell (November 8, 1900 – August 16, 1949) was an American novelist and journalist. Mitchell wrote only one novel that was published during her lifetime, the American Civil War-era novel ''Gone With the Wind (novel), Gone ...

. The novel

A novel is an extended work of narrative fiction usually written in prose and published as a book. The word derives from the for 'new', 'news', or 'short story (of something new)', itself from the , a singular noun use of the neuter plural of ...

, published in 1936, quickly became a bestseller. It won the 1937 Pulitzer Prize, and in 1939 an equally famous movie

A film, also known as a movie or motion picture, is a work of visual art that simulates experiences and otherwise communicates ideas, stories, perceptions, emotions, or atmosphere through the use of moving images that are generally, sinc ...

of the novel premiered. In the eyes of some modern scholars, Mitchell's novel consolidated white supremacist Lost Cause ideologies (see Lost Cause of the Confederacy

The Lost Cause of the Confederacy, known simply as the Lost Cause, is an American pseudohistory, pseudohistorical and historical negationist myth that argues the cause of the Confederate States of America, Confederate States during the America ...

) to construct a bucolic plantation South in which slavery was a benign, or even benevolent, institution. Under this view, she presents white southerners as victims of a rapacious Northern industrial capitalism and depicts black southerners as either lazy, stupid, and over sexualized, or as docile, childlike, and resolutely loyal to their white masters. Southern literature has always drawn audiences outside the South and outside the United States, and ''Gone with the Wind'' has continued to popularize harmful stereotypes of southern history and culture for audiences around the world. Despite this criticism, ''Gone with the Wind'' has enjoyed an enduring legacy as the most popular American novel ever written, an incredible achievement for a female writer. Since publication, ''Gone with the Wind'' has become a staple in many Southern homes.

Post World War II Southern literature

Southern literature following the Second World War grew thematically as it embraced the social and cultural changes in the South resulting from the Civil Rights Movement. In addition, more non-Christian, homosexual, female and African-American writers began to be accepted as part of Southern literature, including African Americans such as Zora Neale Hurston andSterling Allen Brown

Sterling Allen Brown (May 1, 1901 – January 13, 1989) was an American professor, folklorist, poet, and literary critic. He chiefly studied black culture of the Southern United States and was a professor at Howard University for most of his ca ...

, along with women such as Eudora Welty, Flannery O'Connor, Ellen Glasgow

Ellen Anderson Gholson Glasgow (April 22, 1873 – November 21, 1945) was an American novelist who won the Pulitzer Prize for the Novel in 1942 for her novel In This Our Life (novel), ''In This Our Life''. She published 20 novels, as well as shor ...

, Carson McCullers

Carson McCullers (February 19, 1917 – September 29, 1967) was an American novelist, short-story writer, playwright, essayist, and poet. Her first novel, ''The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter'' (1940), explores the spiritual isolation of misfits ...

, Katherine Anne Porter

Katherine Anne Porter (May 15, 1890 – September 18, 1980) was an American journalist, essayist, short story writer, novelist, poet, and political activist. Her 1962 novel '' Ship of Fools'' was the best-selling novel in the United States that y ...

, and Shirley Ann Grau, among many others. Other well-known Southern writers of this period include Reynolds Price, James Dickey

James Lafayette Dickey (February 2, 1923 January 19, 1997) was an American poet, novelist, critic, and lecturer. He was appointed the 18th United States Poet Laureate in 1966. His other accolades included the National Book Award for Poetry a ...

, William Price Fox, Davis Grubb

Davis Alexander Grubb (July 23, 1919 – July 24, 1980) was an American novelist and short story writer, best known for his 1953 novel ''The Night of the Hunter (novel), The Night of the Hunter'', which was

The Night of the Hunter (film), adapt ...

, Walker Percy, and William Styron. One of the most highly praised Southern novels of the 20th century, ''To Kill a Mockingbird

''To Kill a Mockingbird'' is a 1960 Southern Gothic novel by American author Harper Lee. It became instantly successful after its release; in the United States, it is widely read in high schools and middle schools. ''To Kill a Mockingbird'' ...

'' by Harper Lee

Nelle Harper Lee (April 28, 1926 – February 19, 2016) was an American novelist whose 1960 novel ''To Kill a Mockingbird'' won the 1961 Pulitzer Prize and became a classic of modern American literature. She assisted her close friend Truman ...

, won the Pulitzer Prize

The Pulitzer Prizes () are 23 annual awards given by Columbia University in New York City for achievements in the United States in "journalism, arts and letters". They were established in 1917 by the will of Joseph Pulitzer, who had made his fo ...

when it was published in 1960. New Orleans native and Harper Lee's friend, Truman Capote

Truman Garcia Capote ( ; born Truman Streckfus Persons; September 30, 1924 – August 25, 1984) was an American novelist, screenwriter, playwright, and actor. Several of his short stories, novels, and plays have been praised as literary classics ...

also found great success in the middle 20th century with '' Breakfast at Tiffany's'' and later '' In Cold Blood''. Another famous novel of the 1960s is '' A Confederacy of Dunces'', written by New Orleans

New Orleans (commonly known as NOLA or The Big Easy among other nicknames) is a Consolidated city-county, consolidated city-parish located along the Mississippi River in the U.S. state of Louisiana. With a population of 383,997 at the 2020 ...

native John Kennedy Toole in the 1960s but not published until 1980. It won the Pulitzer Prize

The Pulitzer Prizes () are 23 annual awards given by Columbia University in New York City for achievements in the United States in "journalism, arts and letters". They were established in 1917 by the will of Joseph Pulitzer, who had made his fo ...

in 1981 and has since become a cult classic

A cult following is a group of Fan (person), fans who are highly dedicated to a person, idea, object, movement, or work, often an artist, in particular a performing artist, or an artwork in some List of art media, medium. The latter is often cal ...

.

Southern poetry bloomed in the decades following the Second World War in large part thanks to the writing and efforts of Robert Penn Warren

Robert Penn Warren (April 24, 1905 – September 15, 1989) was an American poet, novelist, literary critic and professor at Yale University. He was one of the founders of New Criticism. He was also a charter member of the Fellowship of Southern ...

and James Dickey

James Lafayette Dickey (February 2, 1923 January 19, 1997) was an American poet, novelist, critic, and lecturer. He was appointed the 18th United States Poet Laureate in 1966. His other accolades included the National Book Award for Poetry a ...

. Where earlier work primarily championed a white, agrarian past, the efforts of such poets as Dave Smith, Charles Wright, Ellen Bryant Voigt, Yusef Komunyakaa, Jim Seay, Frank Stanford, Kate Daniels, James Applewhite, Betty Adcock, Rodney Jones, and former U.S. Poet Laureate Natasha Trethewey have opened up the subject matter and form of Southern poetry.

Contemporary Southern literature

Today, in the early twenty-first century, the American South is undergoing a number of cultural and social changes, including rapid industrialization/deindustrialization

Deindustrialization is a process of social and economic change caused by the removal or reduction of industrial capacity or activity in a country or region, especially of heavy industry or manufacturing industry.

There are different interpr ...

, climate change, and an influx of immigrants. As a result, the exact definition of what constitutes Southern literature is changing. While some critics specify that the previous definitions of Southern literature still hold, with some of them suggesting, only somewhat in jest, that all Southern literature must still contain a dead mule within its pages, most scholars of the twenty-first century South highlight the proliferation of depictions of "Souths": urban, undead, queer, activist, televisual, cinematic, and particularly multiethnic (particularly Latinos, Native American, and African American

African Americans, also known as Black Americans and formerly also called Afro-Americans, are an Race and ethnicity in the United States, American racial and ethnic group that consists of Americans who have total or partial ancestry from an ...

). Not only do these critics argue that the very fabric of the South has changed so much that the old assumptions about southern literature no longer hold, but they argue that the U.S. South has always been a construct.

Among today's prominent southern writers are Tim Gautreaux

Timothy Martin Gautreaux (born 1947 in Morgan City, Louisiana) is an American novelist and short story writer.

His writing has appeared in ''The New Yorker'', '' Best American Short Stories'', '' The Atlantic'', '' Harper's'', and '' GQ''. His ...

, William Gay, Padgett Powell, Pat Conroy

Donald Patrick Conroy (October 26, 1945 – March 4, 2016) was an American author who wrote several acclaimed novels and memoirs; his books ''The Water Is Wide (book), The Water is Wide'', ''The Lords of Discipline'', ''The Prince of Tides (no ...

, Fannie Flagg, Randall Kenan, Ernest Gaines, John Grisham

John Ray Grisham Jr. (; born February 8, 1955) is an American novelist, lawyer, and former politician, known for his best-selling legal thrillers. According to the Academy of Achievement, American Academy of Achievement, Grisham has written 37 ...

, Mary Hood, Lee Smith, Tom Robbins, Tom Wolfe

Thomas Kennerly Wolfe Jr. (March 2, 1930 – May 14, 2018)Some sources say 1931; ''The New York Times'' and Reuters both initially reported 1931 in their obituaries before changing to 1930. See and was an American author and journalist widely ...

, Wendell Berry, Cormac McCarthy

Cormac McCarthy (born Charles Joseph McCarthy Jr.; July 20, 1933 – June 13, 2023) was an American author who wrote twelve novels, two plays, five screenplays, and three short stories, spanning the Western, post-apocalyptic, and Southern Got ...

, Ron Rash

Ron Rash (born September 25, 1953) is an American poet, short story writer and novelist and the Parris Distinguished Professor in Appalachian Cultural Studies at Western Carolina University.

Early life

Rash was born on September 25, 1953, in Ch ...

, Barry Hannah, Donna Tartt, Anne Rice, Edward P. Jones, Barbara Kingsolver, Margaret Maron, Anne Tyler, Larry Brown, Horton Foote

Albert Horton Foote Jr. (March 14, 1916March 4, 2009) was an American playwright and screenwriter. He received Academy Awards for ''To Kill a Mockingbird'', which was adapted from the 1960 novel of the same name by Harper Lee, and the film, '' ...

, Allan Gurganus, George Singleton, Clyde Edgerton, Daniel Wallace, Kaye Gibbons, Winston Groom, Lewis Nordan, Richard Ford

Richard Ford (born February 16, 1944) is an American novelist and short story author, and writer of a series of novels featuring the character Frank Bascombe.

Ford's first collection of short stories, ''Rock Springs (short stories), Rock Springs ...

, Ferrol Sams, Natasha Trethewey, Claudia Emerson, Dave Smith, Olympia Vernon, Jill McCorkle, Andrew Hudgins, Maurice Manning, and Jesmyn Ward.

Selected journals

* '' Black Warrior Review'' — Published by University of Alabama * '' Georgia Review'' — Published by University of Georgia * '' Gulf Coast: A Journal of Literature and Fine Arts'' — Published at the University of Houston. * '' Jabberwock Review'' — published byMississippi State University

Mississippi State University for Agriculture and Applied Science, commonly known as Mississippi State University (MSU), is a Public university, public land-grant university, land-grant research university in Mississippi State, Mississippi, Un ...

* '' Southern Literary Journal and Monthly Magazine'' — (1835–1837)

* '' Sewanee Review'' — America's oldest continuously published literary quarterly (published at the University of the South)

* '' Shenandoah'' — Published by Washington and Lee University

Washington and Lee University (Washington and Lee or W&L) is a Private college, private Liberal arts colleges in the United States, liberal arts college in Lexington, Virginia, United States. Established in 1749 as Augusta Academy, it is among ...

* '' Southern Literary Journal'' — (1964–present)

* '' Mississippi Quarterly'' — A refereed, scholarly journal dedicated to the life and culture of the American South, past and present* The ''

Oxford American

The ''Oxford American'' is a quarterly magazine that focuses on the American South.

First publication

The magazine was founded in late 1989 in Oxford, Mississippi, by Marc Smirnoff (born July 11, 1963).

The name "Oxford American" is a play on ' ...

'' — A quarterly journal of fiction, nonfiction, poetry, photography, and music from and about the South.

* '' The Southern Review'' — The famous literary journal focusing on southern literature.

* '' storySouth'' — A journal of new writings from the American South. Features fiction, poetry, nonfiction, and more.

* '' Southern Cultures'' — Peer-reviewed quarterly of the history, arts, and cultures of the US South, published since 1993, from the UNC Center for the Study of the American South.

* '' Southern Spaces'' — Peer-Reviewed Internet journal examining the spaces and places of the American South.

Notable works

Around 2000 "the 'James Agee Film Project' conducted a poll of book editors, publishers, scholars and reviewers, asking which of the thousands of Southern prose works published during the past century should be considered 'the most remarkable works of modern Southern Literature." Results of the poll yielded the following titles:See also

* Literature of Southern states:Alabama

Alabama ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern and Deep South, Deep Southern regions of the United States. It borders Tennessee to the north, Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia to the east, Florida and the Gu ...

; Arkansas

Arkansas ( ) is a landlocked state in the West South Central region of the Southern United States. It borders Missouri to the north, Tennessee and Mississippi to the east, Louisiana to the south, Texas to the southwest, and Oklahoma ...

; Florida

Florida ( ; ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It borders the Gulf of Mexico to the west, Alabama to the northwest, Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia to the north, the Atlantic ...

; Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the South Caucasus

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the southeastern United States

Georgia may also refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Georgia (name), a list of pe ...

; Kentucky

Kentucky (, ), officially the Commonwealth of Kentucky, is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It borders Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio to the north, West Virginia to the ...

; Louisiana

Louisiana ( ; ; ) is a state in the Deep South and South Central regions of the United States. It borders Texas to the west, Arkansas to the north, and Mississippi to the east. Of the 50 U.S. states, it ranks 31st in area and 25 ...

; Maryland

Maryland ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. It borders the states of Virginia to its south, West Virginia to its west, Pennsylvania to its north, and Delaware to its east ...

; Mississippi

Mississippi ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern and Deep South regions of the United States. It borders Tennessee to the north, Alabama to the east, the Gulf of Mexico to the south, Louisiana to the s ...

, North Carolina

North Carolina ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It is bordered by Virginia to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the east, South Carolina to the south, Georgia (U.S. stat ...

; South Carolina

South Carolina ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It borders North Carolina to the north and northeast, the Atlantic Ocean to the southeast, and Georgia (U.S. state), Georg ...

; Tennessee

Tennessee (, ), officially the State of Tennessee, is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It borders Kentucky to the north, Virginia to the northeast, North Carolina t ...

; Texas

Texas ( , ; or ) is the most populous U.S. state, state in the South Central United States, South Central region of the United States. It borders Louisiana to the east, Arkansas to the northeast, Oklahoma to the north, New Mexico to the we ...

; Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern and Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic regions of the United States between the East Coast of the United States ...

; West Virginia

West Virginia is a mountainous U.S. state, state in the Southern United States, Southern and Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic regions of the United States.The United States Census Bureau, Census Bureau and the Association of American ...

* American literary regionalism

* Southern Gothic

* Southern noir

* Fellowship of Southern Writers

* African-American literature

African American literature is the body of literature produced in the United States by writers of African descent. Phillis Wheatley was an enslaved African woman who became the first African American to publish a book of poetry, which was publis ...

* Louisiana State University Press

References

Bibliography

*published in 20th c.

* 1909-1913 (16 volumes) * * * * Marion Montgomery, "The Sense of Violation: Notes toward a Definition of 'Southern' Fiction," The Georgia Review, 19 (1965) * * * Flannery O'Connor, "Some Aspects of the Grotesque in Southern Fiction," in Mystery and Manners, ed. Sally and Robert Fitzgerald (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1969) * * * * *Michael O'Brien (1979). ''The Idea of the American South, 1920-1941''. Johns Hopkins University Press. * . Fulltext articles via the university's "Documenting the American South" website: *Beginnings of Southern Literature

* ''The History of Southern Literature'' by Louis Rubin. Louisiana State University Press, 1991. * Louis D. Rubin Jr., "From Combray to Ithaca; or, The 'Southernness' of Southern Literature," in The Mockingbird in the Gum Tree (Louisiana State University Press, 1991) * (Explores the overall issues surrounding what makes for southern literature) * * * * * * . (Explanation of what constitutes "good" southern writing) * Patricia Yeager (2000).

Dirt and Desire: Reconstructing Southern Women's Writing, 1930-1990

'. University of Chicago Press. .

published in 21st c.

* Houston A. Baker (2001)''Turning South Again: Re-Thinking Modernism/Re-Reading Booker T''.

Duke University Press. . *

Article exploring 2002 changes in southern literature. * ''The New Dictionary of Cultural Literacy, Third Edition: What Every American Needs to Know'' Edited by James Trefil, Joseph F. Kett, and E. D. Hirsch. Houghton Mifflin, 2002. * * * Tara McPherson (2003).

Reconstructing Dixie: Race, Gender, and Nostalgia in the Imagined South

'. Duke University Press. . *

Genres of Southern Literature

by Lucinda MacKethan. Southern Spaces, Feb. 2004. * Jon Smith; Deborah Cohn, eds. (2004).

Look Away! The U.S. South in New World Studies

'. Duke University Press. . * Leigh Anne Duck (2006).

The Nation's Region: Southern Modernism, Segregation, and U.S. Nationalism

'. University of Georgia Press. . * Riché Richardson (2007).

Black Masculinity and the U.S. South: From Uncle Tom to Gangsta

'. University of Georgia Press. . *Anderson, Eric Gary.

On Native Ground: Indigenous Presences and Countercolonial Strategies in Southern Narratives of Captivity, Removal, and Repossession

''Southern Spaces.'' August 9, 2007. *Leigh Anne Duck (July 2008). " Southern Nonidentity." ''Safundi: The Journal of South African and American Studies'', 9 (3): 319–330. *Harilaos Stecopoulos (2008).

Reconstructing the World: Southern Fictions and U.S. Imperialisms, 1898-1976

'. Cornell University Press. . * * Scott Romine (2008).

The Real South: Southern Narrative in the Age of Cultural Reproduction

'. Louisiana State University Press. . *Jennifer Rae Greeson (2010).

Our South: Geographic Fantasy and the Rise of National Literature

'. Harvard University Press. . * Thadious M. Davis (2011).

Southscapes: Geographies of Race, Region, and Literature

'. University of North Carolina Press. . * Deborah Barker; Kathryn McKee, eds. (2011).

American Cinema and the Southern Imaginary

'. University of Georgia Press. . * * Melanie Benson Taylor (2012).

Reconstructing the Native South: American Indian Literature and the Lost Cause

'. University of Georgia Press. . * Jay Watson (2012).

Reading for the Body: The Recalcitrant Materiality of Southern Fiction, 1893-1985

'. University of Georgia Press. . * * Keith Cartwright (2013).

Sacral Grooves, Limbo Gateways: Travels in Deep Southern Time, Circum-Caribbean Space, Afro-Creole Authority

'. University of Georgia Press. . * Matthew Pratt Guterl (2013).

American Mediterranean: Southern Slaveholders in the Age of Emancipation

'. Harvard University Press. . * Claudia Milian (2013).

Latining America: Black-Brown Passages and the Coloring of Latino/a Studies

'. University of Georgia Press. . * Jon Smith (2013).

Finding Purple America: The South and the Future of American Cultural Studies

'. University of Georgia Press. . * * * Eric Gary Anderson; Taylor Hagood; Daniel Cross Turner, eds. (2015)

''Undead Souths: The Gothic and Beyond in Southern Literature and Culture''

Louisiana State University Press. . * Martyn Bone; Brian Ward; William A. Link, eds. (2015). ''Creating and Consuming the American South''. University Press of Florida. . * * * Jennifer Rae Greeson; Scott Romine, eds. (2016).

Keywords for Southern Studies

'. University of Georgia Press. .

External links

Library of Southern Literature, University of North Carolina

American Southern literature pre-1929.

* (A checklist of scholarship on writers associated with the American South; directory arranged by period: colonial, contemporary, etc. Sponsored by Mississippi Quarterly. Ceased publication. )

Southern Poetry from Holman Prison Death Row Inmate Darrell Grayson

*

Poets in Place

" at ''Southern Spaces''. *

History of Southern Literature online publishing.

Since 1995 the American South has relied on the Dead Mule School of Southern Literature for quality fiction, poetry and more. {{DEFAULTSORT:Southern Literature Culture of the Southern United States American literary movements