Southern Indian Ocean on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Indian Ocean is the third-largest of the world's five

Several features make the Indian Ocean unique. It constitutes the core of the large-scale Tropical Warm Pool which, when interacting with the atmosphere, affects the climate both regionally and globally. Asia blocks heat export and prevents the ventilation of the Indian Ocean

Several features make the Indian Ocean unique. It constitutes the core of the large-scale Tropical Warm Pool which, when interacting with the atmosphere, affects the climate both regionally and globally. Asia blocks heat export and prevents the ventilation of the Indian Ocean

* Madagascar and the islands of the western Indian Ocean (Comoros, Réunion, Mauritius, Rodrigues, the Seychelles, and Socotra), includes 13,000 (11,600 endemic) species of plants; 313 (183) birds; reptiles 381 (367); 164 (97) freshwater fishes; 250 (249) amphibians; and 200 (192) mammals.

The origin of this diversity is debated; the break-up of Gondwana can explain vicariance older than 100 mya, but the diversity on the younger, smaller islands must have required a Cenozoic dispersal from the rims of the Indian Ocean to the islands. A "reverse colonisation", from islands to continents, apparently occurred more recently; the

* Madagascar and the islands of the western Indian Ocean (Comoros, Réunion, Mauritius, Rodrigues, the Seychelles, and Socotra), includes 13,000 (11,600 endemic) species of plants; 313 (183) birds; reptiles 381 (367); 164 (97) freshwater fishes; 250 (249) amphibians; and 200 (192) mammals.

The origin of this diversity is debated; the break-up of Gondwana can explain vicariance older than 100 mya, but the diversity on the younger, smaller islands must have required a Cenozoic dispersal from the rims of the Indian Ocean to the islands. A "reverse colonisation", from islands to continents, apparently occurred more recently; the

Pleistocene fossils of ''

Pleistocene fossils of '' At least eleven prehistoric tsunamis have struck the Indian Ocean coast of Indonesia between 7400 and 2900 years ago. Analysing sand beds in caves in the Aceh region, scientists concluded that the intervals between these tsunamis have varied from series of minor tsunamis over a century to dormant periods of more than 2000 years preceding megathrusts in the Sunda Trench. Although the risk for future tsunamis is high, a major megathrust such as the one in 2004 is likely to be followed by a long dormant period.

A group of scientists have argued that two large-scale impact events have occurred in the Indian Ocean: the Burckle Crater in the southern Indian Ocean in 2800 BCE and the Kanmare and Tabban craters in the

At least eleven prehistoric tsunamis have struck the Indian Ocean coast of Indonesia between 7400 and 2900 years ago. Analysing sand beds in caves in the Aceh region, scientists concluded that the intervals between these tsunamis have varied from series of minor tsunamis over a century to dormant periods of more than 2000 years preceding megathrusts in the Sunda Trench. Although the risk for future tsunamis is high, a major megathrust such as the one in 2004 is likely to be followed by a long dormant period.

A group of scientists have argued that two large-scale impact events have occurred in the Indian Ocean: the Burckle Crater in the southern Indian Ocean in 2800 BCE and the Kanmare and Tabban craters in the

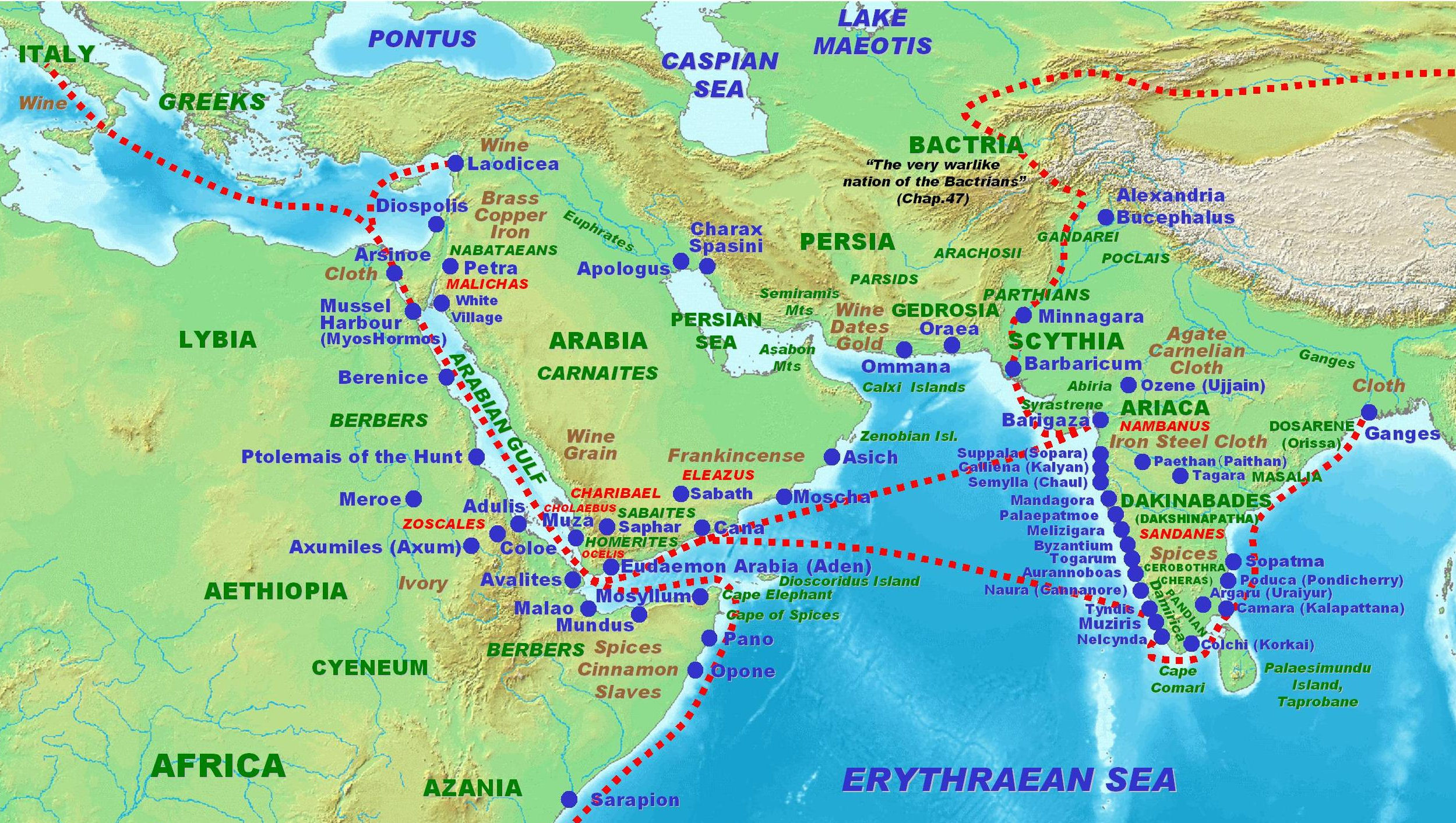

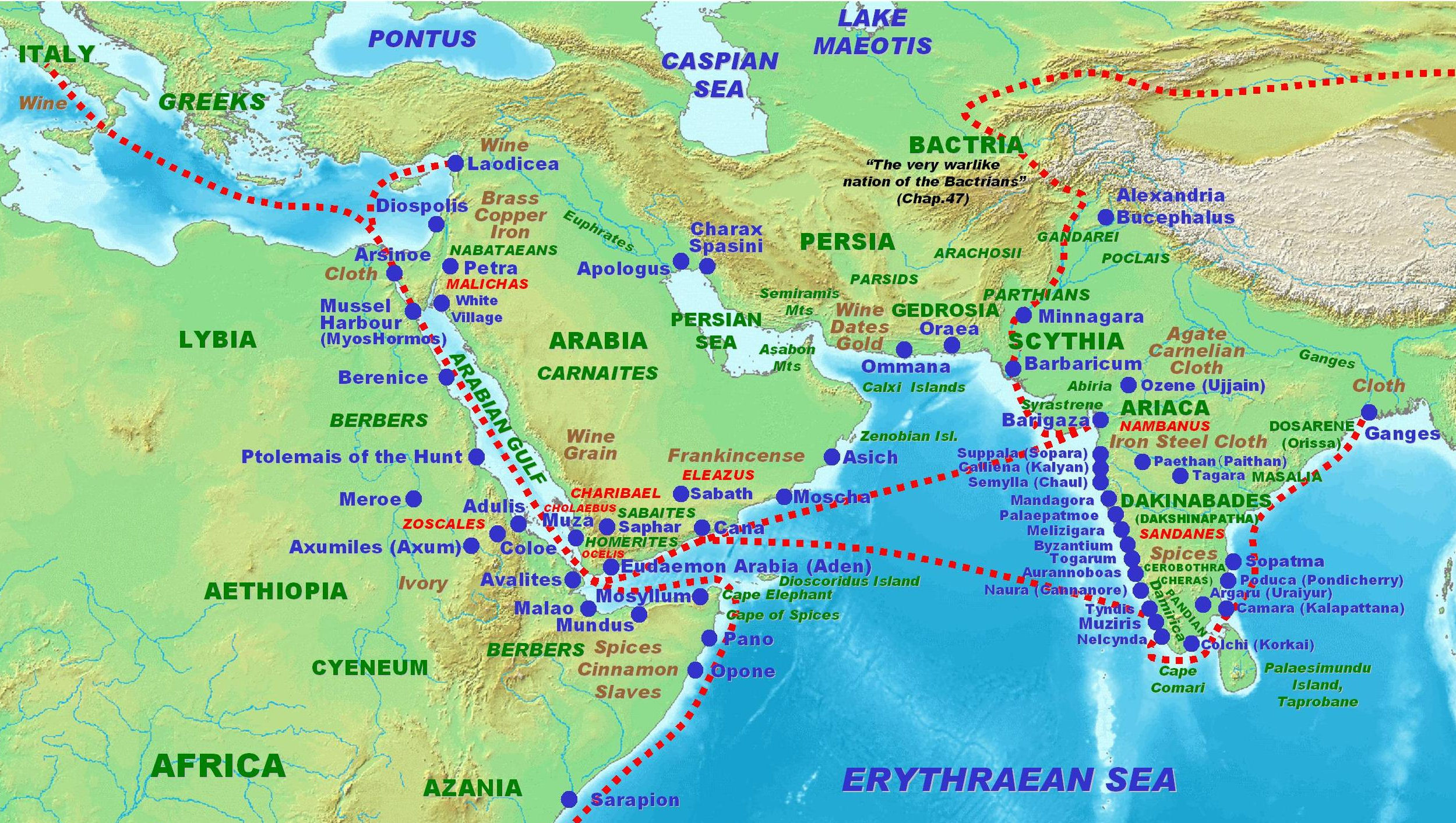

The Red Sea, one of the main trade routes in Antiquity, was explored by

The Red Sea, one of the main trade routes in Antiquity, was explored by  ''

''

Unlike the Pacific Ocean where the civilization of the

Unlike the Pacific Ocean where the civilization of the

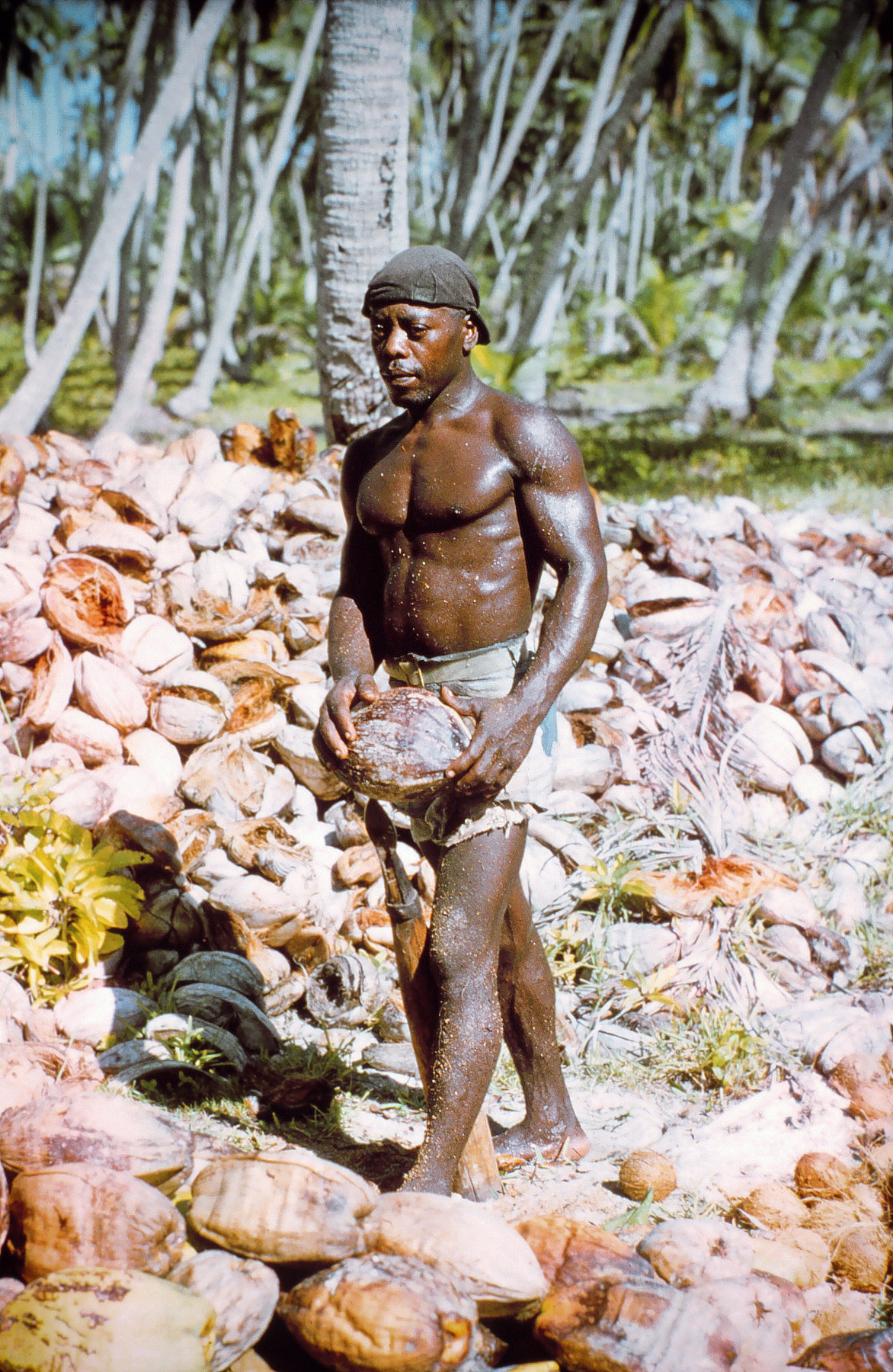

Throughout the colonial era, islands such as

Throughout the colonial era, islands such as

The sea lanes in the Indian Ocean are considered among the most strategically important in the world with more than 80 percent of the world's seaborne trade in oil transits through the Indian Ocean and its vital chokepoints, with 40 percent passing through the Strait of Hormuz, 35 percent through the Strait of Malacca and 8 percent through the Bab el-Mandab Strait.

The Indian Ocean provides major sea routes connecting the Middle East, Africa, and East Asia with Europe and the Americas. It carries a particularly heavy traffic of petroleum and petroleum products from the oil fields of the Persian Gulf and Indonesia. Large reserves of hydrocarbons are being tapped in the offshore areas of Saudi Arabia, Iran, India, and Western Australia. An estimated 40% of the world's offshore oil production comes from the Indian Ocean. Beach sands rich in heavy minerals, and offshore placer deposits are actively exploited by bordering countries, particularly India, Pakistan, South Africa, Indonesia, Sri Lanka, and Thailand.

In particular, the maritime part of the

The sea lanes in the Indian Ocean are considered among the most strategically important in the world with more than 80 percent of the world's seaborne trade in oil transits through the Indian Ocean and its vital chokepoints, with 40 percent passing through the Strait of Hormuz, 35 percent through the Strait of Malacca and 8 percent through the Bab el-Mandab Strait.

The Indian Ocean provides major sea routes connecting the Middle East, Africa, and East Asia with Europe and the Americas. It carries a particularly heavy traffic of petroleum and petroleum products from the oil fields of the Persian Gulf and Indonesia. Large reserves of hydrocarbons are being tapped in the offshore areas of Saudi Arabia, Iran, India, and Western Australia. An estimated 40% of the world's offshore oil production comes from the Indian Ocean. Beach sands rich in heavy minerals, and offshore placer deposits are actively exploited by bordering countries, particularly India, Pakistan, South Africa, Indonesia, Sri Lanka, and Thailand.

In particular, the maritime part of the

ocean

The ocean is the body of salt water that covers approximately 70.8% of Earth. The ocean is conventionally divided into large bodies of water, which are also referred to as ''oceans'' (the Pacific, Atlantic, Indian Ocean, Indian, Southern Ocean ...

ic divisions, covering or approximately 20% of the water area of Earth's surface

Earth is the third planet from the Sun and the only astronomical object known to Planetary habitability, harbor life. This is enabled by Earth being an ocean world, the only one in the Solar System sustaining liquid surface water. Almost all ...

. It is bounded by Asia to the north, Africa to the west and Australia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a country comprising mainland Australia, the mainland of the Australia (continent), Australian continent, the island of Tasmania and list of islands of Australia, numerous smaller isl ...

to the east. To the south it is bounded by the Southern Ocean

The Southern Ocean, also known as the Antarctic Ocean, comprises the southernmost waters of the world ocean, generally taken to be south of 60th parallel south, 60° S latitude and encircling Antarctica. With a size of , it is the seco ...

or Antarctica

Antarctica () is Earth's southernmost and least-populated continent. Situated almost entirely south of the Antarctic Circle and surrounded by the Southern Ocean (also known as the Antarctic Ocean), it contains the geographic South Pole. ...

, depending on the definition in use. The Indian Ocean has large marginal or regional seas, including the Andaman Sea

The Andaman Sea (historically also known as the Burma Sea) is a marginal sea of the northeastern Indian Ocean bounded by the coastlines of Myanmar and Thailand along the Gulf of Martaban and the west side of the Malay Peninsula, and separated f ...

, the Arabian Sea

The Arabian Sea () is a region of sea in the northern Indian Ocean, bounded on the west by the Arabian Peninsula, Gulf of Aden and Guardafui Channel, on the northwest by Gulf of Oman and Iran, on the north by Pakistan, on the east by India, and ...

, the Bay of Bengal

The Bay of Bengal is the northeastern part of the Indian Ocean. Geographically it is positioned between the Indian subcontinent and the Mainland Southeast Asia, Indochinese peninsula, located below the Bengal region.

Many South Asian and Southe ...

, and the Laccadive Sea

The Laccadive Sea ( ), also known as the Lakshadweep Sea, is a body of water bordering India (including its Lakshadweep islands), the Maldives, and Sri Lanka. It is located to the southwest of Karnataka, to the west of Kerala and to the south of ...

.

Geologically, the Indian Ocean is the youngest of the oceans, and it has distinct features such as narrow continental shelves

A continental shelf is a portion of a continent that is submerged under an area of relatively shallow water, known as a shelf sea. Much of these shelves were exposed by drops in sea level during glacial periods. The shelf surrounding an island ...

. Its average depth is 3,741 m. It is the warmest ocean, with a significant impact on global climate

Climate is the long-term weather pattern in a region, typically averaged over 30 years. More rigorously, it is the mean and Statistical dispersion, variability of Meteorology, meteorological variables over a time spanning from months to milli ...

due to its interaction with the atmosphere. Its waters are affected by the Indian Ocean Walker circulation

The Walker circulation, also known as the Walker cell, is a conceptual model of the air flow in the tropics in the lower atmosphere (troposphere). According to this model, parcels of air follow a closed circulation in the zonal and vertical dir ...

, resulting in unique oceanic currents and upwelling patterns. The Indian Ocean is ecologically diverse, with important ecosystems such as coral reefs, mangroves, and sea grass beds. It hosts a significant portion of the world's tuna catch and is home to endangered marine species. The climate around the Indian Ocean is characterized by monsoon

A monsoon () is traditionally a seasonal reversing wind accompanied by corresponding changes in precipitation but is now used to describe seasonal changes in Atmosphere of Earth, atmospheric circulation and precipitation associated with annu ...

s.

The Indian Ocean has been a hub of cultural and commercial exchange since ancient times. It played a key role in early human migrations and the spread of civilizations. In modern times, it remains crucial for global trade, especially in oil and hydrocarbons. Environmental and geopolitical concerns in the region include climate change

Present-day climate change includes both global warming—the ongoing increase in Global surface temperature, global average temperature—and its wider effects on Earth's climate system. Climate variability and change, Climate change in ...

, overfishing

Overfishing is the removal of a species of fish (i.e. fishing) from a body of water at a rate greater than that the species can replenish its population naturally (i.e. the overexploitation of the fishery's existing Fish stocks, fish stock), resu ...

, pollution

Pollution is the introduction of contaminants into the natural environment that cause harm. Pollution can take the form of any substance (solid, liquid, or gas) or energy (such as radioactivity, heat, sound, or light). Pollutants, the component ...

, piracy, and disputes over island territories.

Etymology

The Indian Ocean has been known by its present name since at least 1515, when the Latin form ''Oceanus Orientalis Indicus'' () is attested, named after India, which projects into it. It was earlier known as the ''Eastern Ocean'', a term that was still in use during the mid-18th century, as opposed to the ''Western Ocean'' (Atlantic

The Atlantic Ocean is the second largest of the world's five oceanic divisions, with an area of about . It covers approximately 17% of Earth's surface and about 24% of its water surface area. During the Age of Discovery, it was known for se ...

) before the Pacific

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean, or, depending on the definition, to Antarctica in the south, and is bounded by the cont ...

was surmised. In modern times, the name Afro-Asian Ocean has occasionally been used.

The Hindi

Modern Standard Hindi (, ), commonly referred to as Hindi, is the Standard language, standardised variety of the Hindustani language written in the Devanagari script. It is an official language of India, official language of the Government ...

name for the Ocean is (; ). Conversely, Chinese explorers

Chinese may refer to:

* Something related to China

* Chinese people, people identified with China, through nationality, citizenship, and/or ethnicity

**Han Chinese, East Asian ethnic group native to China.

**''Zhonghua minzu'', the supra-ethnic ...

(e.g., Zheng He

Zheng He (also romanized Cheng Ho; 1371–1433/1435) was a Chinese eunuch, admiral and diplomat from the early Ming dynasty, who is often regarded as the greatest admiral in History of China, Chinese history. Born into a Muslims, Muslim famil ...

during the Ming dynasty

The Ming dynasty, officially the Great Ming, was an Dynasties of China, imperial dynasty of China that ruled from 1368 to 1644, following the collapse of the Mongol Empire, Mongol-led Yuan dynasty. The Ming was the last imperial dynasty of ...

) who traveled to the Indian Ocean during the 15th century called it the Western Oceans. In Ancient Greek geography

;Pre-Hellenistic Classical Greece

*Homer

*Anaximander (died )

*Hecataeus of Miletus (died )

*Massaliote Periplus (6th century BC)

*Scylax of Caryanda (6th century BC)

*Herodotus (died )

;Hellenistic period

*Pytheas (died )

*''Periplus of Pseudo- ...

, the Indian Ocean region known to the Greeks was called the Erythraean Sea.

Geography

Extent and data

The borders of the Indian Ocean, as delineated by theInternational Hydrographic Organization

The International Hydrographic Organization (IHO) (French: ''Organisation Hydrographique Internationale'') is an intergovernmental organization representing hydrography. the IHO comprised 102 member states.

A principal aim of the IHO is to ...

in 1953, included the Southern Ocean

The Southern Ocean, also known as the Antarctic Ocean, comprises the southernmost waters of the world ocean, generally taken to be south of 60th parallel south, 60° S latitude and encircling Antarctica. With a size of , it is the seco ...

but not the marginal seas along the northern rim. In 2002 the IHO delimited the Southern Ocean separately, which removed waters south of 60°S from the Indian Ocean but included the northern marginal seas. Meridionally, the Indian Ocean is delimited from the Atlantic Ocean by the 20° east meridian, running south from Cape Agulhas

Cape Agulhas (; , "Cape of Needles") is a rocky headland in Western Cape, South Africa. It is the geographic southern tip of Africa and the beginning of the traditional dividing line between the Atlantic and Indian oceans according to the In ...

, South Africa, and from the Pacific Ocean by the meridian of 146°49'E, running south from South East Cape on the island of Tasmania

Tasmania (; palawa kani: ''Lutruwita'') is an island States and territories of Australia, state of Australia. It is located to the south of the Mainland Australia, Australian mainland, and is separated from it by the Bass Strait. The sta ...

in Australia. The northernmost extent of the Indian Ocean (including marginal seas) is approximately 30°N in the Persian Gulf

The Persian Gulf, sometimes called the Arabian Gulf, is a Mediterranean seas, mediterranean sea in West Asia. The body of water is an extension of the Arabian Sea and the larger Indian Ocean located between Iran and the Arabian Peninsula.Un ...

.

The Indian Ocean covers , including the Red Sea

The Red Sea is a sea inlet of the Indian Ocean, lying between Africa and Asia. Its connection to the ocean is in the south, through the Bab-el-Mandeb Strait and the Gulf of Aden. To its north lie the Sinai Peninsula, the Gulf of Aqaba, and th ...

and the Persian Gulf but excluding the Southern Ocean, or 19.5% of the world's oceans. Its volume is or 19.8% of the world's oceans' volume; it has an average depth of and a maximum depth of .

All of the Indian Ocean is in the Eastern Hemisphere

The Eastern Hemisphere is the half of the planet Earth which is east of the prime meridian (which crosses Greenwich, London, United Kingdom) and west of the antimeridian (which crosses the Pacific Ocean and relatively little land from pole to p ...

. The centre of the Eastern Hemisphere, the 90th meridian east, passes through the Ninety East Ridge.

Within these waters are a number of islands. These include those controlled by surrounding countries, and independent island states and territories. Of the non-coastal islands, there are two broad clusters: one around Madagascar, and one south of India. A few other oceanic islands are scattered elsewhere.

Coasts and shelves

In contrast to the Atlantic and Pacific, the Indian Ocean is enclosed by major landmasses and an archipelago on three sides and does not stretch from pole to pole, and can be likened to an embayed ocean. It is centered on the Indian Peninsula. Although this subcontinent has played a significant role in its history, the Indian Ocean has foremostly been a cosmopolitan stage, interlinking diverse regions by innovations, trade, and religion since early in human history. Theactive margin

A convergent boundary (also known as a destructive boundary) is an area on Earth where two or more lithospheric plates collide. One plate eventually slides beneath the other, a process known as subduction. The subduction zone can be defined by a ...

s of the Indian Ocean have an average width (horizontal distance from land to shelf break) of with a maximum width of . The passive margin

A passive margin is the transition between Lithosphere#Oceanic lithosphere, oceanic and Lithosphere#Continental lithosphere, continental lithosphere that is not an active plate continental margin, margin. A passive margin forms by sedimentatio ...

s have an average width of .

The average width of the slopes

In mathematics, the slope or gradient of a Line (mathematics), line is a number that describes the direction (geometry), direction of the line on a plane (geometry), plane. Often denoted by the letter ''m'', slope is calculated as the ratio of t ...

(horizontal distance from shelf break to foot of slope) of the continental shelves are for active and passive margins respectively, with a maximum width of .

In correspondence of the Shelf break, also known as Hinge zone, the Bouguer gravity ranges from 0 to 30 mGals that is unusual for a continental region of around 16 km thick sediments. It has been hypothesized that the "Hinge zone may represent the relict of continental and proto-oceanic crustal boundary formed during the rifting of India from Antarctica

Antarctica () is Earth's southernmost and least-populated continent. Situated almost entirely south of the Antarctic Circle and surrounded by the Southern Ocean (also known as the Antarctic Ocean), it contains the geographic South Pole. ...

."

Australia, Indonesia, and India are the three countries with the longest shorelines and exclusive economic zone

An exclusive economic zone (EEZ), as prescribed by the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, is an area of the sea in which a sovereign state has exclusive rights regarding the exploration and use of marine natural resource, reso ...

s. The continental shelf makes up 15% of the Indian Ocean.

More than two billion people live in countries bordering the Indian Ocean, compared to 1.7 billion for the Atlantic and 2.7 billion for the Pacific (some countries border more than one ocean).

Rivers

The Indian Oceandrainage basin

A drainage basin is an area of land in which all flowing surface water converges to a single point, such as a river mouth, or flows into another body of water, such as a lake or ocean. A basin is separated from adjacent basins by a perimeter, ...

covers , virtually identical to that of the Pacific Ocean and half that of the Atlantic basin, or 30% of its ocean surface (compared to 15% for the Pacific). The Indian Ocean drainage basin is divided into roughly 800 individual basins, half that of the Pacific, of which 50% are located in Asia, 30% in Africa, and 20% in Australasia. The rivers of the Indian Ocean are shorter on average () than those of the other major oceans. The largest rivers are ( order 5) the Zambezi

The Zambezi (also spelled Zambeze and Zambesi) is the fourth-longest river in Africa, the longest east-flowing river in Africa and the largest flowing into the Indian Ocean from Africa. Its drainage basin covers , slightly less than half of t ...

, Ganges

The Ganges ( ; in India: Ganga, ; in Bangladesh: Padma, ). "The Ganges Basin, known in India as the Ganga and in Bangladesh as the Padma, is an international which goes through India, Bangladesh, Nepal and China." is a trans-boundary rive ...

-Brahmaputra

The Brahmaputra is a trans-boundary river which flows through Southwestern China, Northeastern India, and Bangladesh. It is known as Brahmaputra or Luit in Assamese, Yarlung Tsangpo in Tibetan, the Siang/Dihang River in Arunachali, and ...

, Indus

The Indus ( ) is a transboundary river of Asia and a trans- Himalayan river of South and Central Asia. The river rises in mountain springs northeast of Mount Kailash in the Western Tibet region of China, flows northwest through the dis ...

, Jubba, and Murray rivers and (order 4) the Shatt al-Arab

The Shatt al-Arab () is a river about in length that is formed at the confluence of the Euphrates and Tigris rivers in the town of al-Qurnah in the Basra Governorate of southern Iraq. The southern end of the river constitutes the Iran– ...

, Wadi Ad Dawasir (a dried-out river system on the Arabian Peninsula) and Limpopo

Limpopo () is the northernmost Provinces of South Africa, province of South Africa. It is named after the Limpopo River, which forms the province's western and northern borders. The term Limpopo is derived from Rivombo (Livombo/Lebombo), a ...

rivers. After the breakup of East Gondwana

Gondwana ( ; ) was a large landmass, sometimes referred to as a supercontinent. The remnants of Gondwana make up around two-thirds of today's continental area, including South America, Africa, Antarctica, Australia (continent), Australia, Zea ...

and the formation of the Himalayas, the Ganges-Brahmaputra rivers flow into the world's largest delta known as the Bengal delta

The Ganges Delta (also known the Ganges-Brahmaputra Delta, the Sundarbans Delta or the Bengal Delta) is a river delta predominantly covering the Bengal region of the Indian subcontinent, consisting of Bangladesh and the Indian state of West B ...

or Sunderbans

Sundarbans (; pronounced ) is a mangrove forest area in the Ganges Delta formed by the confluence of the Ganges, Brahmaputra and Meghna Rivers in the Bay of Bengal. It spans the area from the Hooghly River in India's state of West Bengal ...

.

Marginal seas

Marginal seas, gulfs, bays and straits of the Indian Ocean include: Along the east coast of Africa, theMozambique Channel

The Mozambique Channel (, , ) is an arm of the Indian Ocean located between the Southeast African countries of Madagascar and Mozambique. The channel is about long and across at its narrowest point, and reaches a depth of about off the coa ...

separates Madagascar

Madagascar, officially the Republic of Madagascar, is an island country that includes the island of Madagascar and numerous smaller peripheral islands. Lying off the southeastern coast of Africa, it is the world's List of islands by area, f ...

from mainland Africa, while the Sea of Zanj

The Sea of Zanj (; ) is a former name for the portion of the western Indian Ocean adjacent to the region in the African Great Lakes referred to by medieval Arab geographers as Zanj.

is located north of Madagascar.

On the northern coast of the Arabian Sea

The Arabian Sea () is a region of sea in the northern Indian Ocean, bounded on the west by the Arabian Peninsula, Gulf of Aden and Guardafui Channel, on the northwest by Gulf of Oman and Iran, on the north by Pakistan, on the east by India, and ...

, Gulf of Aden

The Gulf of Aden (; ) is a deepwater gulf of the Indian Ocean between Yemen to the north, the Arabian Sea to the east, Djibouti to the west, and the Guardafui Channel, the Socotra Archipelago, Puntland in Somalia and Somaliland to the south. ...

is connected to the Red Sea

The Red Sea is a sea inlet of the Indian Ocean, lying between Africa and Asia. Its connection to the ocean is in the south, through the Bab-el-Mandeb Strait and the Gulf of Aden. To its north lie the Sinai Peninsula, the Gulf of Aqaba, and th ...

by the strait of Bab-el-Mandeb

The Bab-el-Mandeb (), the Gate of Grief or the Gate of Tears, is a strait between Yemen on the Arabian Peninsula and Djibouti and Eritrea in the Horn of Africa. It connects the Red Sea to the Gulf of Aden and by extension the Indian Ocean.

...

. In the Gulf of Aden, the Gulf of Tadjoura

The Gulf of Tadjoura (; ) is a gulf or basin of the Indian Ocean in the Horn of Africa. It lies south of the straits of Bab-el-Mandeb, or the entrance to the Red Sea, at . The gulf has many fishing grounds, extensive coral reefs, and abundant ...

is located in Djibouti and the Guardafui Channel

The Guardafui Channel (, ) is an oceanic strait off the tip of the Horn of Africa that lies between the Puntland region of Somalia and the Socotra governorate of Yemen to the west of the Arabian Sea. It connects the Gulf of Aden to the north ...

separates Socotra island from the Horn of Africa. The northern end of the Red Sea terminates in the Gulf of Aqaba

The Gulf of Aqaba () or Gulf of Eilat () is a large gulf at the northern tip of the Red Sea, east of the Sinai Peninsula and west of the Arabian Peninsula. Its coastline is divided among four countries: Egypt, Israel, Jordan, and Saudi Arabia.

...

and Gulf of Suez

The Gulf of Suez (; formerly , ', "Sea of Calm") is a gulf at the northern end of the Red Sea, to the west of the Sinai Peninsula. Situated to the east of the Sinai Peninsula is the smaller Gulf of Aqaba. The gulf was formed within a relative ...

. The Indian Ocean is artificially connected to the Mediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea ( ) is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the east by the Levant in West Asia, on the north by Anatolia in West Asia and Southern Eur ...

without ship lock through the Suez Canal

The Suez Canal (; , ') is an artificial sea-level waterway in Egypt, Indo-Mediterranean, connecting the Mediterranean Sea to the Red Sea through the Isthmus of Suez and dividing Africa and Asia (and by extension, the Sinai Peninsula from the rest ...

, which is accessible via the Red Sea. The Arabian Sea is connected to the Persian Gulf

The Persian Gulf, sometimes called the Arabian Gulf, is a Mediterranean seas, mediterranean sea in West Asia. The body of water is an extension of the Arabian Sea and the larger Indian Ocean located between Iran and the Arabian Peninsula.Un ...

by the Gulf of Oman

The Gulf of Oman or Sea of Oman ( ''khalīj ʿumān''; ''daryâ-ye omân''), also known as Gulf of Makran or Sea of Makran ( ''khalīj makrān''; ''daryâ-ye makrān''), is a gulf in the Indian Ocean that connects the Arabian Sea with th ...

and the Strait of Hormuz

The Strait of Hormuz ( ''Tangeh-ye Hormoz'' , ''Maḍīq Hurmuz'') is a strait between the Persian Gulf and the Gulf of Oman. It provides the only sea passage from the Persian Gulf to the open ocean and is one of the world's most strategica ...

. In the Persian Gulf, the Gulf of Bahrain

The Gulf of Bahrain () is an inlet of the Persian Gulf on the east coast of Saudi Arabia, separated from the main body of water by the peninsula of Qatar. It surrounds the islands of Bahrain. The King Fahd Causeway crosses the western section of ...

separates Qatar from the Arabic Peninsula.

Along the west coast of India, the Gulf of Kutch

The Gulf of Kutch is located between the peninsula regions of Kutch and Saurashtra, bounded in the state of Gujarat that borders Pakistan. It opens towards the Arabian Sea facing the Gulf of Oman.

It is about 50 km wide at the entrance b ...

and Gulf of Khambat are located in Gujarat in the northern end while the Laccadive Sea

The Laccadive Sea ( ), also known as the Lakshadweep Sea, is a body of water bordering India (including its Lakshadweep islands), the Maldives, and Sri Lanka. It is located to the southwest of Karnataka, to the west of Kerala and to the south of ...

separates the Maldives from the southern tip of India. The Bay of Bengal

The Bay of Bengal is the northeastern part of the Indian Ocean. Geographically it is positioned between the Indian subcontinent and the Mainland Southeast Asia, Indochinese peninsula, located below the Bengal region.

Many South Asian and Southe ...

is off the east coast of India. The Gulf of Mannar

The Gulf of Mannar ( ) (; ) is a large shallow bay forming part of the Laccadive Sea in the Indian Ocean with an average depth of .Palk Strait

Palk Strait is a strait between the Indian state of Tamil Nadu and Northern Province of Sri Lanka. It connects the Palk Bay in the Bay of Bengal in the north with the Gulf of Mannar in the Laccadive sea in the south. It stretches for about ...

separate Sri Lanka from India, while Adam's Bridge

Adam's Bridge, also known as Rama's Bridge or ''Rama Setu'', is a chain of natural limestone shoals between Pamban Island, also known as Rameswaram Island, off the southeastern coast of Tamil Nadu, India, and Mannar Island, off the northwe ...

separates the two. The Andaman Sea

The Andaman Sea (historically also known as the Burma Sea) is a marginal sea of the northeastern Indian Ocean bounded by the coastlines of Myanmar and Thailand along the Gulf of Martaban and the west side of the Malay Peninsula, and separated f ...

is located between the Bay of Bengal and the Andaman Islands.

In Indonesia, the so-called Indonesian Seaway is composed of the Malacca

Malacca (), officially the Historic State of Malacca (), is a States and federal territories of Malaysia, state in Malaysia located in the Peninsular Malaysia#Other features, southern region of the Malay Peninsula, facing the Strait of Malacca ...

, Sunda and Torres Strait

The Torres Strait (), also known as Zenadh Kes ( Kalaw Lagaw Ya#Phonology 2, �zen̪ad̪ kes, is a strait between Australia and the Melanesian island of New Guinea. It is wide at its narrowest extent. To the south is Cape York Peninsula, ...

s.

The Gulf of Carpentaria

The Gulf of Carpentaria is a sea off the northern coast of Australia. It is enclosed on three sides by northern Australia and bounded on the north by the eastern Arafura Sea, which separates Australia and New Guinea. The northern boundary ...

is located on the Australian north coast while the Great Australian Bight

The Great Australian Bight is a large oceanic bight (geography), bight, or open bay, off the central and western portions of the southern Coast, coastline of mainland Australia.

There are two definitions for its extent—one by the Internation ...

constitutes a large part of its southern coast.

# Arabian Sea

The Arabian Sea () is a region of sea in the northern Indian Ocean, bounded on the west by the Arabian Peninsula, Gulf of Aden and Guardafui Channel, on the northwest by Gulf of Oman and Iran, on the north by Pakistan, on the east by India, and ...

– 3.862 million km2

# Bay of Bengal

The Bay of Bengal is the northeastern part of the Indian Ocean. Geographically it is positioned between the Indian subcontinent and the Mainland Southeast Asia, Indochinese peninsula, located below the Bengal region.

Many South Asian and Southe ...

– 2.172 million km2

# Andaman Sea

The Andaman Sea (historically also known as the Burma Sea) is a marginal sea of the northeastern Indian Ocean bounded by the coastlines of Myanmar and Thailand along the Gulf of Martaban and the west side of the Malay Peninsula, and separated f ...

– 797,700 km2

# Laccadive Sea

The Laccadive Sea ( ), also known as the Lakshadweep Sea, is a body of water bordering India (including its Lakshadweep islands), the Maldives, and Sri Lanka. It is located to the southwest of Karnataka, to the west of Kerala and to the south of ...

– 786,000 km2

# Mozambique Channel

The Mozambique Channel (, , ) is an arm of the Indian Ocean located between the Southeast African countries of Madagascar and Mozambique. The channel is about long and across at its narrowest point, and reaches a depth of about off the coa ...

– 700,000 km2

# Timor Sea

The Timor Sea (, , or ) is a relatively shallow sea in the Indian Ocean bounded to the north by the island of Timor with Timor-Leste to the north, Indonesia to the northwest, Arafura Sea to the east, and to the south by Australia. The Sunda Tr ...

– 610,000 km2

# Red Sea

The Red Sea is a sea inlet of the Indian Ocean, lying between Africa and Asia. Its connection to the ocean is in the south, through the Bab-el-Mandeb Strait and the Gulf of Aden. To its north lie the Sinai Peninsula, the Gulf of Aqaba, and th ...

– 438,000 km2

# Gulf of Aden

The Gulf of Aden (; ) is a deepwater gulf of the Indian Ocean between Yemen to the north, the Arabian Sea to the east, Djibouti to the west, and the Guardafui Channel, the Socotra Archipelago, Puntland in Somalia and Somaliland to the south. ...

– 410,000 km2

# Persian Gulf

The Persian Gulf, sometimes called the Arabian Gulf, is a Mediterranean seas, mediterranean sea in West Asia. The body of water is an extension of the Arabian Sea and the larger Indian Ocean located between Iran and the Arabian Peninsula.Un ...

– 251,000 km2

# Flores Sea

The Flores Sea covers of water in Indonesia. The sea is bounded on the north by the island of Celebes and on the south by Sunda Islands, the Sunda Islands of Flores and Sumbawa.

Geography

The seas that border the Flores Sea are the Bali Sea ...

– 240,000 km2

# Molucca Sea

The Molucca Sea (Indonesian language, Indonesian: ''Laut Maluku'') is located in the western Pacific Ocean, around the vicinity of Indonesia, specifically bordered by the Indonesian Islands of Sulawesi, Celebes (Sulawesi) to the west, Halmahera t ...

– 200,000 km2

# Gulf of Oman

The Gulf of Oman or Sea of Oman ( ''khalīj ʿumān''; ''daryâ-ye omân''), also known as Gulf of Makran or Sea of Makran ( ''khalīj makrān''; ''daryâ-ye makrān''), is a gulf in the Indian Ocean that connects the Arabian Sea with th ...

– 181,000 km2

# Great Australian Bight

The Great Australian Bight is a large oceanic bight (geography), bight, or open bay, off the central and western portions of the southern Coast, coastline of mainland Australia.

There are two definitions for its extent—one by the Internation ...

– 45,926 km2

# Gulf of Aqaba

The Gulf of Aqaba () or Gulf of Eilat () is a large gulf at the northern tip of the Red Sea, east of the Sinai Peninsula and west of the Arabian Peninsula. Its coastline is divided among four countries: Egypt, Israel, Jordan, and Saudi Arabia.

...

– 239 km2

# Gulf of Khambhat

The Gulf of Khambhat, also known as the Gulf of Cambay, is a bay on the Arabian Sea coast of India, bordering the state of Gujarat just north of Mumbai and Diu Island. The Gulf of Khambhat is about long, about wide in the north and up to wi ...

# Gulf of Kutch

The Gulf of Kutch is located between the peninsula regions of Kutch and Saurashtra, bounded in the state of Gujarat that borders Pakistan. It opens towards the Arabian Sea facing the Gulf of Oman.

It is about 50 km wide at the entrance b ...

# Gulf of Suez

The Gulf of Suez (; formerly , ', "Sea of Calm") is a gulf at the northern end of the Red Sea, to the west of the Sinai Peninsula. Situated to the east of the Sinai Peninsula is the smaller Gulf of Aqaba. The gulf was formed within a relative ...

# Dubai Canal

# Strait of Hormuz

The Strait of Hormuz ( ''Tangeh-ye Hormoz'' , ''Maḍīq Hurmuz'') is a strait between the Persian Gulf and the Gulf of Oman. It provides the only sea passage from the Persian Gulf to the open ocean and is one of the world's most strategica ...

Climate

Several features make the Indian Ocean unique. It constitutes the core of the large-scale Tropical Warm Pool which, when interacting with the atmosphere, affects the climate both regionally and globally. Asia blocks heat export and prevents the ventilation of the Indian Ocean

Several features make the Indian Ocean unique. It constitutes the core of the large-scale Tropical Warm Pool which, when interacting with the atmosphere, affects the climate both regionally and globally. Asia blocks heat export and prevents the ventilation of the Indian Ocean thermocline

A thermocline (also known as the thermal layer or the metalimnion in lakes) is

a distinct layer based on temperature within a large body of fluid (e.g. water, as in an ocean or lake; or air, e.g. an atmosphere) with a high gradient of distinct te ...

. That continent also drives the Indian Ocean monsoon

A monsoon () is traditionally a seasonal reversing wind accompanied by corresponding changes in precipitation but is now used to describe seasonal changes in Atmosphere of Earth, atmospheric circulation and precipitation associated with annu ...

, the strongest on Earth, which causes large-scale seasonal variations in ocean currents, including the reversal of the Somali Current and Indian Monsoon Current. Because of the Indian Ocean Walker circulation

The Walker circulation, also known as the Walker cell, is a conceptual model of the air flow in the tropics in the lower atmosphere (troposphere). According to this model, parcels of air follow a closed circulation in the zonal and vertical dir ...

there are no continuous equatorial easterlies. Upwelling

Upwelling is an physical oceanography, oceanographic phenomenon that involves wind-driven motion of dense, cooler, and usually nutrient-rich water from deep water towards the ocean surface. It replaces the warmer and usually nutrient-depleted sur ...

occurs near the Horn of Africa

The Horn of Africa (HoA), also known as the Somali Peninsula, is a large peninsula and geopolitical region in East Africa.Robert Stock, ''Africa South of the Sahara, Second Edition: A Geographical Interpretation'', (The Guilford Press; 2004), ...

and the Arabian Peninsula

The Arabian Peninsula (, , or , , ) or Arabia, is a peninsula in West Asia, situated north-east of Africa on the Arabian plate. At , comparable in size to India, the Arabian Peninsula is the largest peninsula in the world.

Geographically, the ...

in the Northern Hemisphere

The Northern Hemisphere is the half of Earth that is north of the equator. For other planets in the Solar System, north is defined by humans as being in the same celestial sphere, celestial hemisphere relative to the invariable plane of the Solar ...

and north of the trade winds in the Southern Hemisphere. The Indonesian Throughflow

The Indonesian Throughflow (ITF; ) is an ocean current with importance for global climate as is the low-latitude movement of warm, relative freshwater from the north Pacific to the Indian Ocean. It thus serves as a main upper branch of the glob ...

is a unique Equatorial connection to the Pacific.

The climate north of the equator

The equator is the circle of latitude that divides Earth into the Northern Hemisphere, Northern and Southern Hemisphere, Southern Hemispheres of Earth, hemispheres. It is an imaginary line located at 0 degrees latitude, about in circumferen ...

is affected by a monsoon

A monsoon () is traditionally a seasonal reversing wind accompanied by corresponding changes in precipitation but is now used to describe seasonal changes in Atmosphere of Earth, atmospheric circulation and precipitation associated with annu ...

climate. Strong north-east winds blow from October until April; from May until October south and west winds prevail. In the Arabian Sea, the violent Monsoon brings rain to the Indian subcontinent. In the southern hemisphere, the winds are generally milder, but summer storms near Mauritius can be severe. When the monsoon winds change, cyclones sometimes strike the shores of the Arabian Sea

The Arabian Sea () is a region of sea in the northern Indian Ocean, bounded on the west by the Arabian Peninsula, Gulf of Aden and Guardafui Channel, on the northwest by Gulf of Oman and Iran, on the north by Pakistan, on the east by India, and ...

and the Bay of Bengal

The Bay of Bengal is the northeastern part of the Indian Ocean. Geographically it is positioned between the Indian subcontinent and the Mainland Southeast Asia, Indochinese peninsula, located below the Bengal region.

Many South Asian and Southe ...

. Some 80% of the total annual rainfall in India occurs during summer and the region is so dependent on this rainfall that many civilisations perished when the Monsoon failed in the past. The huge variability in the Indian Summer Monsoon has also occurred pre-historically, with a strong, wet phase 33,500–32,500 BP; a weak, dry phase 26,000–23,500 BC; and a very weak phase 17,000–15,000 BP,

corresponding to a series of dramatic global events: Bølling–Allerød warming, Heinrich, and Younger Dryas

The Younger Dryas (YD, Greenland Stadial GS-1) was a period in Earth's geologic history that occurred circa 12,900 to 11,700 years Before Present (BP). It is primarily known for the sudden or "abrupt" cooling in the Northern Hemisphere, when the ...

.

The Indian Ocean is the warmest ocean in the world. Long-term ocean temperature records show a rapid, continuous warming in the Indian Ocean, at about (compared to for the warm pool region) during 1901–2012. Research indicates that human induced greenhouse warming, and changes in the frequency and magnitude of El Niño

EL, El or el may refer to:

Arts and entertainment Fictional entities

* El, a character from the manga series ''Shugo Chara!'' by Peach-Pit

* Eleven (''Stranger Things'') (El), a fictional character in the TV series ''Stranger Things''

* El, fami ...

(or the Indian Ocean Dipole

The Indian Ocean Dipole (IOD), is an irregular oscillation of sea surface temperatures in which the western Indian Ocean becomes alternately warmer (positive phase) and then colder (negative phase) than the eastern part of the ocean.

Phenomen ...

), events are a trigger to this strong warming in the Indian Ocean. While the Indian Ocean warmed at a rate of 1.2 °C per century during 1950–2020, climate models predict accelerated warming, at a rate of 1.7 °C–3.8 °C per century during 2020–2100. Though the warming is basin-wide, maximum warming is in the northwestern Indian Ocean including the Arabian Sea, and reduced warming off the Sumatra and Java coasts in the southeast Indian Ocean. Global warming is projected to push the tropical Indian Ocean into a basin-wide near-permanent heatwave state by the end of the 21st century, where marine heatwaves are projected to increase from 20 days per year (during 1970–2000) to 220–250 days per year.

South of the Equator (20–5°S), the Indian Ocean is gaining heat from June to October, during the austral winter, while it is losing heat from November to March, during the austral summer.

In 1999, the Indian Ocean Experiment showed that fossil fuel and biomass burning in South and Southeast Asia caused air pollution (also known as the Asian brown cloud) that reach as far as the Intertropical Convergence Zone

The Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ , or ICZ), known by sailors as the doldrums or the calms because of its monotonous windless weather, is the area where the northeast and the southeast trade winds converge. It encircles Earth near the t ...

. This pollution has implications on both a local and global scale.

Oceanography

Forty percent of the sediment of the Indian Ocean is found in the Indus and Ganges fans. The oceanic basins adjacent to the continental slopes mostly contain terrigenous sediments. The ocean south of thepolar front

In meteorology, the polar front is the weather front boundary between the polar cell and the Ferrel cell around the 60° latitude, near the polar regions, in both hemispheres. At this boundary a sharp gradient in temperature occurs between thes ...

(roughly 50° south latitude) is high in biologic productivity and dominated by non-stratified sediment composed mostly of siliceous

Silicon dioxide, also known as silica, is an oxide of silicon with the chemical formula , commonly found in nature as quartz. In many parts of the world, silica is the major constituent of sand. Silica is one of the most complex and abundant ...

oozes. Near the three major mid-ocean ridges the ocean floor is relatively young and therefore bare of sediment, except for the Southwest Indian Ridge due to its ultra-slow spreading rate.

The ocean's currents

Currents, Current or The Current may refer to:

Science and technology

* Current (fluid), the flow of a liquid or a gas

** Air current, a flow of air

** Ocean current, a current in the ocean

*** Rip current, a kind of water current

** Current (hy ...

are mainly controlled by the monsoon. Two large gyre

In oceanography, a gyre () is any large system of ocean surface currents moving in a circular fashion driven by wind movements. Gyres are caused by the Coriolis effect; planetary vorticity, horizontal friction and vertical friction determine the ...

s, one in the northern hemisphere flowing clockwise and one south of the equator moving anticlockwise (including the Agulhas Current and Agulhas Return Current

The Agulhas Return Current (ARC) is an ocean current in the South Indian Ocean. The ARC contributes to the water exchange between oceans by forming a link between the South Atlantic Current and the South Indian Ocean Current. It can reach veloc ...

), constitute the dominant flow pattern. During the winter monsoon (November–February), however, circulation is reversed north of 30°S and winds are weakened during winter and the transitional periods between the monsoons.

The Indian Ocean contains the largest submarine fans of the world, the Bengal Fan and Indus Fan, and the largest areas of slope terraces and rift valley

A rift valley is a linear shaped lowland between several highlands or mountain ranges produced by the action of a geologic rift. Rifts are formed as a result of the pulling apart of the lithosphere due to extensional tectonics. The linear ...

s.

The inflow of deep water into the Indian Ocean is 11 Sv, most of which comes from the Circumpolar Deep Water (CDW). The CDW enters the Indian Ocean through the Crozet and Madagascar

Madagascar, officially the Republic of Madagascar, is an island country that includes the island of Madagascar and numerous smaller peripheral islands. Lying off the southeastern coast of Africa, it is the world's List of islands by area, f ...

basins and crosses the Southwest Indian Ridge at 30°S. In the Mascarene Basin

The Mascarene Basin is an oceanic basin in the western Indian Ocean. It was formed as the tectonic plate of the Indian subcontinent pulled away from the Madagascar Plate about 66–90 Mya, following the breaking up of the Gondwana supercon ...

the CDW becomes a deep western boundary current

Boundary currents are ocean currents with dynamics determined by the presence of a coastline, and fall into two distinct categories: western boundary currents and eastern boundary currents.

Eastern boundary currents

Eastern boundary currents are ...

before it is met by a re-circulated branch of itself, the North Indian Deep Water. This mixed water partly flows north into the Somali Basin whilst most of it flows clockwise in the Mascarene Basin where an oscillating flow is produced by Rossby waves

Rossby waves, also known as planetary waves, are a type of inertial wave naturally occurring in rotating fluids. They were first identified by Sweden-born American meteorologist Carl-Gustaf Arvid Rossby in the Earth's atmosphere in 1939. They ar ...

.

Water circulation in the Indian Ocean is dominated by the Subtropical Anticyclonic Gyre, the eastern extension of which is blocked by the Southeast Indian Ridge and the 90°E Ridge. Madagascar and the Southwest Indian Ridge separate three cells south of Madagascar and off South Africa. North Atlantic Deep Water

North Atlantic Deep Water (NADW) is a deep water mass formed in the North Atlantic Ocean. Thermohaline circulation (properly described as meridional overturning circulation) of the world's oceans involves the flow of warm surface waters from the ...

reaches into the Indian Ocean south of Africa at a depth of and flows north along the eastern continental slope of Africa. Deeper than NADW, Antarctic Bottom Water

The Antarctic bottom water (AABW) is a type of water mass in the Southern Ocean surrounding Antarctica with temperatures ranging from −0.8 to 2 °C (35 °F) and absolute salinities from 34.6 to 35.0 g/kg. As the densest water mass of ...

flows from Enderby Basin to Agulhas Basin across deep channels (<) in the Southwest Indian Ridge, from where it continues into the Mozambique Channel

The Mozambique Channel (, , ) is an arm of the Indian Ocean located between the Southeast African countries of Madagascar and Mozambique. The channel is about long and across at its narrowest point, and reaches a depth of about off the coa ...

and Prince Edward fracture zone.

North of 20° south latitude the minimum surface temperature is , exceeding to the east. Southward of 40° south latitude, temperatures drop quickly.

The Bay of Bengal

The Bay of Bengal is the northeastern part of the Indian Ocean. Geographically it is positioned between the Indian subcontinent and the Mainland Southeast Asia, Indochinese peninsula, located below the Bengal region.

Many South Asian and Southe ...

contributes more than half () of the runoff water to the Indian Ocean. Mainly in summer, this runoff flows into the Arabian Sea but also south across the Equator where it mixes with fresher seawater from the Indonesian Throughflow

The Indonesian Throughflow (ITF; ) is an ocean current with importance for global climate as is the low-latitude movement of warm, relative freshwater from the north Pacific to the Indian Ocean. It thus serves as a main upper branch of the glob ...

. This mixed freshwater joins the South Equatorial Current

The South Equatorial Current are ocean currents in the Pacific, Atlantic, and Indian Ocean that flow east-to-west between the equator and about 20 degrees south. In the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans, it extends across the equator to about 5 degre ...

in the southern tropical Indian Ocean.

Sea surface salinity is highest (more than 36 PSU) in the Arabian Sea because evaporation exceeds precipitation there. In the Southeast Arabian Sea salinity drops to less than 34 PSU. It is the lowest (c. 33 PSU) in the Bay of Bengal because of river runoff and precipitation. The Indonesian Throughflow and precipitation results in lower salinity (34 PSU) along the Sumatran west coast. Monsoonal variation results in eastward transportation of saltier water from the Arabian Sea to the Bay of Bengal from June to September and in westerly transport by the East India Coastal Current to the Arabian Sea from January to April.

An Indian Ocean garbage patch was discovered in 2010 covering at least . Riding the southern Indian Ocean Gyre

The Indian Ocean gyre, located in the Indian Ocean, is one of the five major oceanic gyres, large systems of rotating ocean currents, which together form the backbone of the global conveyor belt. The Indian Ocean gyre is composed of two major cu ...

, this vortex of plastic garbage constantly circulates the ocean from Australia to Africa, down the Mozambique Channel

The Mozambique Channel (, , ) is an arm of the Indian Ocean located between the Southeast African countries of Madagascar and Mozambique. The channel is about long and across at its narrowest point, and reaches a depth of about off the coa ...

, and back to Australia in a period of six years, except for debris that gets indefinitely stuck in the centre of the gyre.

The garbage patch in the Indian Ocean will, according to a 2012 study, decrease in size after several decades to vanish completely over centuries. Over several millennia, however, the global system of garbage patches will accumulate in the North Pacific.

There are two amphidromes of opposite rotation in the Indian Ocean, probably caused by Rossby wave

Rossby waves, also known as planetary waves, are a type of inertial wave naturally occurring in rotating fluids. They were first identified by Sweden-born American meteorologist Carl-Gustaf Arvid Rossby in the Earth's atmosphere in 1939. They ...

propagation.

Iceberg

An iceberg is a piece of fresh water ice more than long that has broken off a glacier or an ice shelf and is floating freely in open water. Smaller chunks of floating glacially derived ice are called "growlers" or "bergy bits". Much of an i ...

s drift as far north as 55° south latitude, similar to the Pacific but less than in the Atlantic where icebergs reach up to 45°S. The volume of iceberg loss in the Indian Ocean between 2004 and 2012 was 24 Gt.

Since the 1960s, anthropogenic warming of the global ocean combined with contributions of freshwater from retreating land ice causes a global rise in sea level. Sea level also increases in the Indian Ocean, except in the south tropical Indian Ocean where it decreases, a pattern most likely caused by rising levels of greenhouse gas

Greenhouse gases (GHGs) are the gases in the atmosphere that raise the surface temperature of planets such as the Earth. Unlike other gases, greenhouse gases absorb the radiations that a planet emits, resulting in the greenhouse effect. T ...

es.

Marine life

Among the tropical oceans, the western Indian Ocean hosts one of the largest concentrations ofphytoplankton

Phytoplankton () are the autotrophic (self-feeding) components of the plankton community and a key part of ocean and freshwater Aquatic ecosystem, ecosystems. The name comes from the Greek language, Greek words (), meaning 'plant', and (), mea ...

blooms in summer, due to the strong monsoon

A monsoon () is traditionally a seasonal reversing wind accompanied by corresponding changes in precipitation but is now used to describe seasonal changes in Atmosphere of Earth, atmospheric circulation and precipitation associated with annu ...

winds. The monsoonal wind forcing leads to a strong coastal and open ocean upwelling

Upwelling is an physical oceanography, oceanographic phenomenon that involves wind-driven motion of dense, cooler, and usually nutrient-rich water from deep water towards the ocean surface. It replaces the warmer and usually nutrient-depleted sur ...

, which introduces nutrients into the upper zones where sufficient light is available for photosynthesis

Photosynthesis ( ) is a system of biological processes by which photosynthetic organisms, such as most plants, algae, and cyanobacteria, convert light energy, typically from sunlight, into the chemical energy necessary to fuel their metabo ...

and phytoplankton production. These phytoplankton blooms support the marine ecosystem, as the base of the marine food web, and eventually the larger fish species. The Indian Ocean accounts for the second-largest share of the most economically valuable tuna

A tuna (: tunas or tuna) is a saltwater fish that belongs to the tribe Thunnini, a subgrouping of the Scombridae ( mackerel) family. The Thunnini comprise 15 species across five genera, the sizes of which vary greatly, ranging from the bul ...

catch. Its fish are of great and growing importance to the bordering countries for domestic consumption and export. Fishing fleets from Russia, Japan, South Korea

South Korea, officially the Republic of Korea (ROK), is a country in East Asia. It constitutes the southern half of the Korea, Korean Peninsula and borders North Korea along the Korean Demilitarized Zone, with the Yellow Sea to the west and t ...

, and Taiwan

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is a country in East Asia. The main geography of Taiwan, island of Taiwan, also known as ''Formosa'', lies between the East China Sea, East and South China Seas in the northwestern Pacific Ocea ...

also exploit the Indian Ocean, mainly for shrimp

A shrimp (: shrimp (American English, US) or shrimps (British English, UK)) is a crustacean with an elongated body and a primarily Aquatic locomotion, swimming mode of locomotion – typically Decapods belonging to the Caridea or Dendrobranchi ...

and tuna.

Research indicates that increasing ocean temperatures are taking a toll on the marine ecosystem. A study on the phytoplankton changes in the Indian Ocean indicates a decline of up to 20% in the marine plankton in the Indian Ocean, during the past six decades. The tuna catch rates have also declined 50–90% during the past half-century, mostly due to increased industrial fisheries, with the ocean warming

Ocean heat content (OHC) or ocean heat uptake (OHU) is the energy absorbed and stored by oceans, and is thus an important indicator of Climate change, global warming. Ocean heat content is calculated by measuring ocean temperature at many differe ...

adding further stress to the fish species.

Endangered and vulnerable marine mammals and turtles:

80% of the Indian Ocean is open ocean and includes nine large marine ecosystems: the Agulhas Current, Somali Coastal Current, Red Sea

The Red Sea is a sea inlet of the Indian Ocean, lying between Africa and Asia. Its connection to the ocean is in the south, through the Bab-el-Mandeb Strait and the Gulf of Aden. To its north lie the Sinai Peninsula, the Gulf of Aqaba, and th ...

, Arabian Sea

The Arabian Sea () is a region of sea in the northern Indian Ocean, bounded on the west by the Arabian Peninsula, Gulf of Aden and Guardafui Channel, on the northwest by Gulf of Oman and Iran, on the north by Pakistan, on the east by India, and ...

, Bay of Bengal

The Bay of Bengal is the northeastern part of the Indian Ocean. Geographically it is positioned between the Indian subcontinent and the Mainland Southeast Asia, Indochinese peninsula, located below the Bengal region.

Many South Asian and Southe ...

, Gulf of Thailand

The Gulf of Thailand (), historically known as the Gulf of Siam (), is a shallow inlet adjacent to the southwestern South China Sea, bounded between the southwestern shores of the Indochinese Peninsula and the northern half of the Malay Peninsula. ...

, West Central Australian Shelf, Northwest Australian Shelf and Southwest Australian Shelf. Coral reefs cover c. . The coasts of the Indian Ocean includes beaches and intertidal zones covering and 246 larger estuaries

An estuary is a partially enclosed coastal body of brackish water with one or more rivers or streams flowing into it, and with a free connection to the open sea. Estuaries form a transition zone between river environments and maritime environm ...

. Upwelling

Upwelling is an physical oceanography, oceanographic phenomenon that involves wind-driven motion of dense, cooler, and usually nutrient-rich water from deep water towards the ocean surface. It replaces the warmer and usually nutrient-depleted sur ...

areas are small but important. The hypersaline saltern

A saltern is an area or installation for making salt. Salterns include modern salt-making works (saltworks), as well as hypersaline waters that usually contain high concentrations of Halophile, halophilic microorganisms, primarily haloarchaea but ...

s in India covers between and species adapted for this environment, such as '' Artemia salina'' and ''Dunaliella salina

''Dunaliella salina'' is a type of halophile unicellular green algae especially found in hypersaline environments, such as salt lakes and salt evaporation ponds. Known for its antioxidant activity because of its ability to create a large amoun ...

'', are important to bird life.

Coral reefs, sea grass beds, and mangrove forests are the most productive ecosystems of the Indian Ocean — coastal areas produce 20 tones of fish per square kilometre. These areas, however, are also being urbanised with populations often exceeding several thousand people per square kilometre and fishing techniques become more effective and often destructive beyond sustainable levels while the increase in sea surface temperature

Sea surface temperature (or ocean surface temperature) is the ocean temperature, temperature of ocean water close to the surface. The exact meaning of ''surface'' varies in the literature and in practice. It is usually between and below the sea ...

spreads coral bleaching.

Mangrove

A mangrove is a shrub or tree that grows mainly in coastal saline water, saline or brackish water. Mangroves grow in an equatorial climate, typically along coastlines and tidal rivers. They have particular adaptations to take in extra oxygen a ...

s covers in the Indian Ocean region, or almost half of the world's mangrove habitat, of which is located in Indonesia, or 50% of mangroves in the Indian Ocean. Mangroves originated in the Indian Ocean region and have adapted to a wide range of its habitats but it is also where it suffers its biggest loss of habitat.

In 2016, six new animal species were identified at hydrothermal vents

Hydrothermal vents are fissures on the seabed from which geothermally heated water discharges. They are commonly found near volcanically active places, areas where tectonic plates are moving apart at mid-ocean ridges, ocean basins, and hots ...

in the Southwest Indian Ridge: a "Hoff" crab, a "giant peltospirid" snail, a whelk-like snail, a limpet, a scaleworm and a polychaete worm.

The West Indian Ocean coelacanth

The West Indian Ocean coelacanth (''Latimeria chalumnae'') (sometimes known as gombessa, African coelacanth, or simply coelacanth) is a crossopterygian, one of two extant species of coelacanth, a rare order of vertebrates more closely related to ...

was discovered in the Indian Ocean off South Africa in the 1930s and in the late 1990s another species, the Indonesian coelacanth

The Indonesian coelacanth (''Latimeria menadoensis'', Indonesian: ''raja laut''), also called Sulawesi coelacanth, is one of two living species of coelacanth, identifiable by its brown color. ''Latimeria menadoensis'' is a lobe-finned fish belong ...

, was discovered off Sulawesi Island, Indonesia. Most extant coelacanths have been found in the Comoros. Although both species represent an order of lobe-finned fishes

Sarcopterygii (; )—sometimes considered synonymous with Crossopterygii ()—is a clade (traditionally a class (biology), class or subclass) of vertebrate animals which includes a group of bony fish commonly referred to as lobe-finned fish. The ...

known from the Early Devonian (410 ) and thought extinct 66 mya, they are morphologically distinct from their Devonian ancestors. Over millions of years, coelacanths evolved to inhabit different environments — lungs adapted for shallow, brackish waters evolved into gills adapted for deep marine waters.

Biodiversity

Of Earth's 36biodiversity hotspot

A biodiversity hotspot is a ecoregion, biogeographic region with significant levels of biodiversity that is threatened by human habitation. Norman Myers wrote about the concept in two articles in ''The Environmentalist'' in 1988 and 1990, after ...

s nine (or 25%) are located on the margins of the Indian Ocean.

* Madagascar and the islands of the western Indian Ocean (Comoros, Réunion, Mauritius, Rodrigues, the Seychelles, and Socotra), includes 13,000 (11,600 endemic) species of plants; 313 (183) birds; reptiles 381 (367); 164 (97) freshwater fishes; 250 (249) amphibians; and 200 (192) mammals.

The origin of this diversity is debated; the break-up of Gondwana can explain vicariance older than 100 mya, but the diversity on the younger, smaller islands must have required a Cenozoic dispersal from the rims of the Indian Ocean to the islands. A "reverse colonisation", from islands to continents, apparently occurred more recently; the

* Madagascar and the islands of the western Indian Ocean (Comoros, Réunion, Mauritius, Rodrigues, the Seychelles, and Socotra), includes 13,000 (11,600 endemic) species of plants; 313 (183) birds; reptiles 381 (367); 164 (97) freshwater fishes; 250 (249) amphibians; and 200 (192) mammals.

The origin of this diversity is debated; the break-up of Gondwana can explain vicariance older than 100 mya, but the diversity on the younger, smaller islands must have required a Cenozoic dispersal from the rims of the Indian Ocean to the islands. A "reverse colonisation", from islands to continents, apparently occurred more recently; the chameleon

Chameleons or chamaeleons (Family (biology), family Chamaeleonidae) are a distinctive and highly specialized clade of Old World lizards with 200 species described as of June 2015. The members of this Family (biology), family are best known for ...

s, for example, first diversified on Madagascar and then colonised Africa. Several species on the islands of the Indian Ocean are textbook cases of evolutionary processes; the dung beetle

Dung beetles are beetles that feed on feces. All species of dung beetle belong to the superfamily Scarabaeoidea, most of them to the subfamilies Scarabaeinae and Aphodiinae of the family Scarabaeidae (scarab beetles). As most species of Scara ...

s, day geckos, and lemur

Lemurs ( ; from Latin ) are Strepsirrhini, wet-nosed primates of the Superfamily (biology), superfamily Lemuroidea ( ), divided into 8 Family (biology), families and consisting of 15 genera and around 100 existing species. They are Endemism, ...

s are all examples of adaptive radiation

In evolutionary biology, adaptive radiation is a process in which organisms diversify rapidly from an ancestral species into a multitude of new forms, particularly when a change in the environment makes new resources available, alters biotic int ...

.

Many bones (250 bones per square metre) of recently extinct vertebrates have been found in the Mare aux Songes

The Mare aux Songes (English: "pond of taro"; ) swamp is a lagerstätte located close to the sea in south eastern Mauritius. Many subfossils of recently extinct animals have accumulated in the swamp, which was once a lake, and some of the first sub ...

swamp in Mauritius, including bones of the Dodo

The dodo (''Raphus cucullatus'') is an extinction, extinct flightless bird that was endemism, endemic to the island of Mauritius, which is east of Madagascar in the Indian Ocean. The dodo's closest relative was the also-extinct and flightles ...

bird (''Raphus cucullatus'') and '' Cylindraspis'' giant tortoise. An analysis of these remains suggests a process of aridification began in the southwest Indian Ocean began around 4,000 years ago.

* Maputaland-Pondoland-Albany (MPA); 8,100 (1,900 endemic) species of plants; 541 (0) birds; 205 (36) reptiles; 73 (20) freshwater fishes; 73 (11) amphibians; and 197 (3) mammals.

Mammalian megafauna once widespread in the MPA was driven to near extinction in the early 20th century. Some species have been successfully recovered since then — the population of white rhinoceros

The white rhinoceros, also known as the white rhino or square-lipped rhinoceros (''Ceratotherium simum''), is the largest extant species of rhinoceros and the most Sociality, social of all rhino species, characterized by its wide mouth adapted f ...

(''Ceratotherium simum simum'') increased from less than 20 individuals in 1895 to more than 17,000 as of 2013. Other species still depend on fenced areas and management programs, including black rhinoceros

The black rhinoceros (''Diceros bicornis''), also called the black rhino or the hooked-lip rhinoceros, is a species of rhinoceros native to East Africa, East and Southern Africa, including Angola, Botswana, Eswatini, Kenya, Lesotho, Malawi, Moza ...

(''Diceros bicornis minor''), African wild dog

The African wild dog (''Lycaon pictus''), also called painted dog and Cape hunting dog, is a wild canine native to sub-Saharan Africa. It is the largest wild canine in Africa, and the only extant member of the genus '' Lycaon'', which is disti ...

(''Lycaon pictus''), cheetah (''Acynonix jubatus''), elephant (''Loxodonta africana''), and lion (''Panthera leo'').

* Coastal forests of eastern Africa; 4,000 (1,750 endemic) species of plants; 636 (12) birds; 250 (54) reptiles; 219 (32) freshwater fishes; 95 (10) amphibians; and 236 (7) mammals.

This biodiversity hotspot (and namesake ecoregion and "Endemic Bird Area") is a patchwork of small forested areas, often with a unique assemblage of species within each, located within from the coast and covering a total area of c. . It also encompasses coastal islands, including Zanzibar and Pemba, and Mafia.

* Horn of Africa

The Horn of Africa (HoA), also known as the Somali Peninsula, is a large peninsula and geopolitical region in East Africa.Robert Stock, ''Africa South of the Sahara, Second Edition: A Geographical Interpretation'', (The Guilford Press; 2004), ...

; 5,000 (2,750 endemic) species of plants; 704 (25) birds; 284 (93) reptiles; 100 (10) freshwater fishes; 30 (6) amphibians; and 189 (18) mammals.

This area, one of the only two hotspots that are entirely arid, includes the Ethiopian Highlands

The Ethiopian Highlands (also called the Abyssinian Highlands) is a rugged mass of mountains in Ethiopia in Northeast Africa. It forms the largest continuous area of its elevation in the continent, with little of its surface falling below , whil ...

, the East African Rift valley, the Socotra

Socotra, locally known as Saqatri, is a Yemeni island in the Indian Ocean. Situated between the Guardafui Channel and the Arabian Sea, it lies near major shipping routes. Socotra is the largest of the six islands in the Socotra archipelago as ...

islands, as well as some small islands in the Red Sea and areas on the southern Arabic Peninsula. Endemic and threatened mammals include the dibatag

The dibatag (''Ammodorcas clarkei''), or Clarke's gazelle, is a medium-sized slender antelope native to Ethiopia and Somalia. Though not a true gazelle, it is similarly marked, with long legs and neck. It is often confused with the gerenuk du ...

(''Ammodorcas clarkei'') and Speke's gazelle

Speke's gazelle (''Gazella spekei'') is the smallest of the gazelle species. It is confined to the Horn of Africa, where it inhabits stony brush, grass steppes, and semi deserts. This species has been sometimes regarded as a subspecies of the Dor ...

(''Gazella spekei''); the Somali wild ass

The Somali wild ass (''Equus africanus somaliensis'') is a subspecies of the African wild ass.

It is found in Somalia, the Southern Red Sea region of Eritrea, and the Afar Region of Ethiopia. The legs of the Somali wild ass are striped, resemb ...

(''Equus africanus somaliensis'') and hamadryas baboon

The hamadryas baboon (''Papio hamadryas'' ; gawina;Aerts 2019 , Ar Robbaḥ) is a species of baboon within the Old World monkey family. It is the northernmost of all the baboons, being native to the Horn of Africa and the southwestern region o ...

(''Papio hamadryas''). It also contains many reptiles.

In Somalia, the centre of the hotspot, the landscape is dominated by Acacia

''Acacia'', commonly known as wattles or acacias, is a genus of about of shrubs and trees in the subfamily Mimosoideae of the pea family Fabaceae. Initially, it comprised a group of plant species native to Africa, South America, and Austral ...

-Commiphora

''Commiphora'' is the most species-rich genus of flowering plants in the frankincense and myrrh family, Burseraceae. The genus contains approximately 190 species of shrubs and trees, which are distributed throughout the (sub-) tropical regions of A ...

deciduous bushland, but also includes the Yeheb nut

''Cordeauxia edulis'' is a plant in the family ''Fabaceae'' and the monotypic, sole species in the genus ''Cordeauxia''. Known by the common name yeheb bush, it is one of the economically most important wild plants of the Horn of Africa, but it ...

(''Cordeauxia edulus'') and species discovered more recently such as the Somali cyclamen (''Cyclamen somalense''), the only cyclamen outside the Mediterranean. Warsangli linnet (''Carduelis johannis'') is an endemic bird found only in northern Somalia. An unstable political situation and mismanagement has resulted in overgrazing

Overgrazing occurs when plants are exposed to intensive grazing for extended periods of time, or without sufficient recovery periods. It can be caused by either livestock in poorly managed agricultural applications, game reserves, or nature ...

which has produced one of the most degraded hotspots where only c. 5% of the original habitat remains.

* The Western Ghats–Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka, officially the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka, also known historically as Ceylon, is an island country in South Asia. It lies in the Indian Ocean, southwest of the Bay of Bengal, separated from the Indian subcontinent, ...

; 5,916 (3,049 endemic) species of plants; 457 (35) birds; 265 (176) reptiles; 191 (139) freshwater fishes; 204 (156) amphibians; and 143 (27) mammals.

Encompassing the west coast of India and Sri Lanka, until c. 10,000 years ago a land bridge connected Sri Lanka to the Indian Subcontinent, hence this region shares a common community of species.

* Indo-Burma; 13.500 (7,000 endemic) species of plants; 1,277 (73) birds; 518 (204) reptiles; 1,262 (553) freshwater fishes; 328 (193) amphibians; and 401 (100) mammals.

Indo-Burma encompasses a series of mountain ranges, five of Asia's largest river systems, and a wide range of habitats. The region has a long and complex geological history, and long periods rising sea levels

The sea level has been rising from the end of the last ice age, which was around 20,000 years ago. Between 1901 and 2018, the average sea level rose by , with an increase of per year since the 1970s. This was faster than the sea level had e ...

and glaciations have isolated ecosystems and thus promoted a high degree of endemism and speciation

Speciation is the evolutionary process by which populations evolve to become distinct species. The biologist Orator F. Cook coined the term in 1906 for cladogenesis, the splitting of lineages, as opposed to anagenesis, phyletic evolution within ...

. The region includes two centres of endemism: the Annamite Mountains and the northern highlands on the China-Vietnam border.

Several distinct floristic region

A phytochorion, in phytogeography, is a geographic area with a relatively uniform composition of plant species. Adjacent phytochoria do not usually have a sharp boundary, but rather a soft one, a transitional area in which many species from both re ...

s, the Indian, Malesian, Sino-Himalayan, and Indochinese regions, meet in a unique way in Indo-Burma and the hotspot contains an estimated 15,000–25,000 species of vascular plants, many of them endemic.

* Sundaland

Sundaland (also called Sundaica or the Sundaic region) is a biogeographical region of Southeast Asia corresponding to a larger landmass that was exposed throughout the last 2.6 million years during periods when sea levels were lower. It inc ...

; 25,000 (15,000 endemic) species of plants; 771 (146) birds; 449 (244) reptiles; 950 (350) freshwater fishes; 258 (210) amphibians; and 397 (219) mammals.

Sundaland encompasses 17,000 islands of which Borneo and Sumatra are the largest. Endangered mammals include the Bornean and Sumatran orangutan

The Sumatran orangutan (''Pongo abelii'') is one of the three species of orangutans. Critically endangered, and found only in the north of the Indonesian island of Sumatra, it is rarer than the Bornean orangutan but more common than the recently ...

s, the proboscis monkey

The proboscis monkey or long-nosed monkey (''Nasalis larvatus'') is an arboreal Old World monkey with an unusually large nose (or proboscis), a reddish-brown skin color and a long tail. It is endemic to the southeast Asian island of Borneo an ...

, and the Javan and Sumatran rhinoceros

The Sumatran rhinoceros (''Dicerorhinus sumatrensis''), also known as the Sumatran rhino, hairy rhinoceros or Asian two-horned rhinoceros, is a rare member of the family Rhinocerotidae and one of five extant species of rhinoceros; it is the o ...

es.

* Wallacea

Wallacea is a biogeography, biogeographical designation for a group of mainly list of islands of Indonesia, Indonesian islands separated by deep-water straits from the Asian and Australia (continent), Australian continental shelf, continental ...

; 10,000 (1,500 endemic) species of plants; 650 (265) birds; 222 (99) reptiles; 250 (50) freshwater fishes; 49 (33) amphibians; and 244 (144) mammals.

* Southwest Australia