Sol T. Plaatje on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

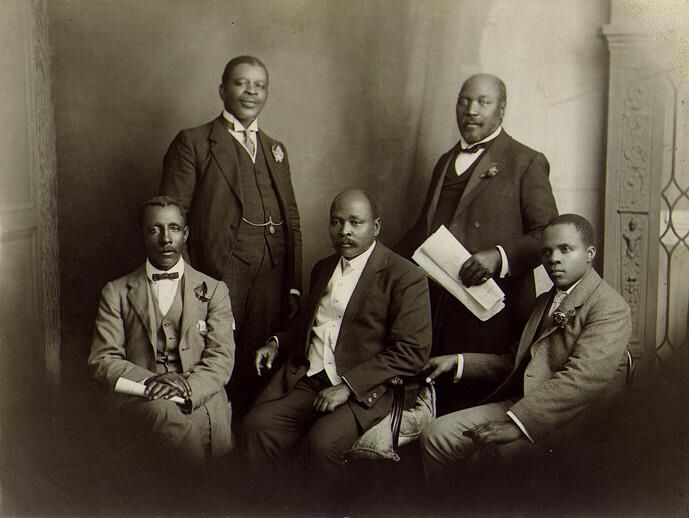

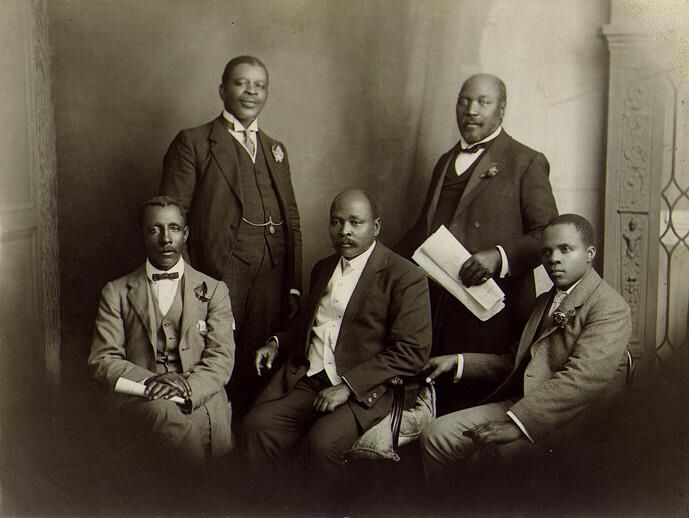

Solomon Tshekisho Plaatje (9 October 1876 – 19 June 1932) was a South African intellectual, journalist,

retrieved 25 July 2013.

As an activist and politician, he spent much of his life in the struggle for the enfranchisement and liberation of African people. He was a founder member and first General Secretary of the South African Native National Congress (SANNC), which became the

As an activist and politician, he spent much of his life in the struggle for the enfranchisement and liberation of African people. He was a founder member and first General Secretary of the South African Native National Congress (SANNC), which became the

retrieved 26 July 2013. * 1992: the house at 32 Angel Street in Kimberley, where Plaatje spent his last years, was declared a national monument (now a provincial heritage site). It continues as the Sol Plaatje Museum and Library, run by the Sol Plaatje Educational Trust, with donor funding. In the 2000s the Sol Plaatje Educational Trust has published Plaatje biographies by Maureen Rall and

linguist

Linguistics is the scientific study of language. The areas of linguistic analysis are syntax (rules governing the structure of sentences), semantics (meaning), Morphology (linguistics), morphology (structure of words), phonetics (speech sounds ...

, politician, translator and writer. Plaatje was a founding member and first General Secretary of the South African Native National Congress

The African National Congress (ANC) is a political party in South Africa. It originated as a liberation movement known for its opposition to apartheid and has governed the country since 1994, when the first post-apartheid election resulted ...

(SANNC), which became the African National Congress

The African National Congress (ANC) is a political party in South Africa. It originated as a liberation movement known for its opposition to apartheid and has governed the country since 1994, when the 1994 South African general election, fir ...

(ANC). The Sol Plaatje Local Municipality

Sol Plaatje Municipality (; ) is a local municipality within the Frances Baard District Municipality, in the Northern Cape province of South Africa. It is named after Sol T. Plaatje. It includes the diamond mining city of Kimberley.

Main place ...

, which includes the city of Kimberley

Kimberly or Kimberley may refer to:

Places and historical events

Australia

Queensland

* Kimberley, Queensland, a coastal locality in the Shire of Douglas

South Australia

* County of Kimberley, a cadastral unit in South Australia

Ta ...

, is named after him, as is the Sol Plaatje University

Sol Plaatje University is a Public university, public university located in Kimberley, Northern Cape, Kimberley, South Africa. Established in 2014, it is the first and only university located in the Northern Cape province.

History

The idea of ...

in that city, which opened its doors in 2014.Address by the President of South Africa during the announcement of new Interim Councils and names of the New Universities, 25 July 2013retrieved 25 July 2013.

Early life

Plaatje was born in Doornfontein nearBoshof

Boshof is a farming town in the west of the Free State province, South Africa.

The town is 55 km north-east of Kimberley on the R64 road. Established in March 1856 on the farm Vanwyksvlei, which had been named after a Griqua who sowed his ...

, Orange Free State

The Orange Free State ( ; ) was an independent Boer-ruled sovereign republic under British suzerainty in Southern Africa during the second half of the 19th century, which ceased to exist after it was defeated and surrendered to the British Em ...

(now Free State Province

The Free State ( ; ; ; ; ), formerly known as the Orange Free State, is a province of South Africa. Its capital is Bloemfontein, which is also South Africa's judicial capital. Its historical origins lie in the Boer republic called the Orang ...

, South Africa), the sixth of eight sons. His grandfather's name was Selogilwe Mogodi (1836-1881) but his employer, the Boer farmer Groenewald, nicknamed him Plaatje ('Picture') in 1856 and the family started using this as a surname. His parents Johannes and Martha were members of the Tswana

Tswana may refer to:

* Tswana people, the Bantu languages, Bantu speaking people in Botswana, South Africa, Namibia, Zimbabwe, Zambia, and other Southern Africa regions

* Tswana language, the language spoken by the (Ba)Tswana people

* Tswanaland, ...

nation. They were Christians and worked for missionaries at mission stations in South Africa. When Solomon was four, the family moved to Pniel near Kimberley in the Cape Colony

The Cape Colony (), also known as the Cape of Good Hope, was a British Empire, British colony in present-day South Africa named after the Cape of Good Hope. It existed from 1795 to 1802, and again from 1806 to 1910, when it united with three ...

to work for a German missionary, Ernst Westphal (the grandfather of the linguist Ernst Westphal) and his wife Wilhelmine. There he received a mission-education. When he outpaced fellow learners he was given additional private tuition by Mrs. Westphal, who also taught him to play the piano and violin and gave him singing lessons. In February 1892, aged 15, he became a pupil-teacher, a post he held for two years.

After leaving school, he moved to Kimberley in 1894 where he became a telegraph

Telegraphy is the long-distance transmission of messages where the sender uses symbolic codes, known to the recipient, rather than a physical exchange of an object bearing the message. Thus flag semaphore is a method of telegraphy, whereas ...

messenger for the Post Office. He subsequently passed the clerical examination (the highest in the colony) with higher marks than any other candidate in Dutch

Dutch or Nederlands commonly refers to:

* Something of, from, or related to the Netherlands

** Dutch people as an ethnic group ()

** Dutch nationality law, history and regulations of Dutch citizenship ()

** Dutch language ()

* In specific terms, i ...

and typing

Typing is the process of writing or inputting text by pressing keys on a typewriter, computer keyboard, mobile phone, or calculator. It can be distinguished from other means of text input, such as handwriting recognition, handwriting and speech ...

(reported by Neil Parsons in his foreword to ''Native Life in South Africa, Before and Since the European War and the Boer Rebellion''). At that time, the Cape Colony had qualified franchise for all men 21 or over, the qualification being that they be able to read and write English or Dutch and earn over 50 pounds a year. Thus, when he turned 21 in 1897, he was able to vote, a right he would later lose when the Cape Colony

The Cape Colony (), also known as the Cape of Good Hope, was a British Empire, British colony in present-day South Africa named after the Cape of Good Hope. It existed from 1795 to 1802, and again from 1806 to 1910, when it united with three ...

was merged with other Southern African colonies into the Union of South Africa

The Union of South Africa (; , ) was the historical predecessor to the present-day South Africa, Republic of South Africa. It came into existence on 31 May 1910 with the unification of the British Cape Colony, Cape, Colony of Natal, Natal, Tra ...

.

Shortly thereafter, he became a court interpreter for the British colonial authorities in Mafeking when the settlement was under siege

''Under Siege'' is a 1992 action thriller film directed by Andrew Davis and written by J. F. Lawton. It stars Steven Seagal (who also produced the film), Tommy Lee Jones, Gary Busey, and Erika Eleniak. Seagal plays Casey Ryback, a former ...

and kept a diary of his experiences which were published posthumously.

After the Second Boer War

The Second Boer War (, , 11 October 189931 May 1902), also known as the Boer War, Transvaal War, Anglo–Boer War, or South African War, was a conflict fought between the British Empire and the two Boer republics (the South African Republic and ...

ended, he was optimistic that the British government would ensure that all males in South Africa would continue to be granted qualified franchise, but they instead handed over the majority of political power to the new South African government

The Government of South Africa, or South African Government, is the national government of the Republic of South Africa, a parliamentary republic with a three-tier system of government and an independent judiciary, operating in a parliamentary ...

, which restricted voting rights to white South Africans

White South Africans are South Africans of European descent. In linguistic, cultural, and historical terms, they are generally divided into the Afrikaans-speaking descendants of the Dutch East India Company's original colonists, known as Afr ...

only. Plaatje criticised the British government for this decision in an unpublished 1909 manuscript entitled ''Sekgoma – the Black Dreyfus.''

Career

As an activist and politician, he spent much of his life in the struggle for the enfranchisement and liberation of African people. He was a founder member and first General Secretary of the South African Native National Congress (SANNC), which became the

As an activist and politician, he spent much of his life in the struggle for the enfranchisement and liberation of African people. He was a founder member and first General Secretary of the South African Native National Congress (SANNC), which became the African National Congress

The African National Congress (ANC) is a political party in South Africa. It originated as a liberation movement known for its opposition to apartheid and has governed the country since 1994, when the 1994 South African general election, fir ...

(ANC) ten years later in 1922. As a member of an SANNC deputation, he traveled to England to protest against the Natives Land Act, 1913

The Natives Land Act, 1913 (subsequently renamed Bantu Land Act, 1913 and Black Land Act, 1913; Act No. 27 of 1913) was an Act of the Parliament of South Africa that was aimed at regulating the acquisition of land. It largely prohibited the sal ...

, and later to Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its Provinces and territories of Canada, ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, making it the world's List of coun ...

and the United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

where he met Marcus Garvey

Marcus Mosiah Garvey Jr. (17 August 188710 June 1940) was a Jamaican political activist. He was the founder and first President-General of the Universal Negro Improvement Association and African Communities League (UNIA-ACL) (commonly known a ...

and W. E. B. Du Bois

William Edward Burghardt Du Bois ( ; February 23, 1868 – August 27, 1963) was an American sociologist, socialist, historian, and Pan-Africanist civil rights activist.

Born in Great Barrington, Massachusetts, Du Bois grew up in a relativel ...

.

While he grew up speaking the Tswana language

Tswana, also known by its Endonym and exonym, native name Setswana, is a Bantu language indigenous to Southern Africa and spoken by about 8.2 million people. It is closely related to the Northern Sotho language, Northern Sotho and Sotho lan ...

, Plaatje would become a polyglot

Multilingualism is the use of more than one language, either by an individual speaker or by a group of speakers. When the languages are just two, it is usually called bilingualism. It is believed that multilingual speakers outnumber monolin ...

. Fluent in at least seven languages, he worked as a court interpreter during the Siege of Mafeking

The siege of Mafeking was a 217-day siege battle for the town of Mafeking (now called Mahikeng) in South Africa during the Second Boer War from October 1899 to May 1900. The siege received considerable attention as Lord Edward Cecil, the son o ...

, and translated works of William Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 23 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's nation ...

into Tswana

Tswana may refer to:

* Tswana people, the Bantu languages, Bantu speaking people in Botswana, South Africa, Namibia, Zimbabwe, Zambia, and other Southern Africa regions

* Tswana language, the language spoken by the (Ba)Tswana people

* Tswanaland, ...

. His talent for language would lead to a career in journalism and writing. He was editor and part-owner of ''Kuranta ya Becoana'' (''Bechuana Gazette'') in Mahikeng

Mahikeng ( Tswana for "Place of Rocks"), formerly known as Mafikeng and alternatively known as Mafeking (, ), is the capital city of the North West province of South Africa.

Close to South Africa's border with Botswana, Mafikeng is northeast ...

, and in Kimberley

Kimberly or Kimberley may refer to:

Places and historical events

Australia

Queensland

* Kimberley, Queensland, a coastal locality in the Shire of Douglas

South Australia

* County of Kimberley, a cadastral unit in South Australia

Ta ...

''Tsala ya Becoana'' (''Bechuana Friend'') and ''Tsala ya Batho'' (''The Friend of the People'').

Plaatje was the first black South African to write a novel in English – ''Mhudi

''Mhudi: An Epic of South African Native Life a Hundred Years Ago'' is a South African novel by Sol Plaatje, first published in 1930. The novel has been republished many times, including in the influential Heinemann African Writers Series.

The ...

''. He wrote the novel in 1919, but it was only published in 1930 (in 1928 the Zulu writer R. R. R. Dhlomo published an English-language novel, entitled ''An African Tragedy'', at the missionary Lovedale Press, in Alice

Alice may refer to:

* Alice (name), most often a feminine given name, but also used as a surname

Literature

* Alice (''Alice's Adventures in Wonderland''), a character in books by Lewis Carroll

* ''Alice'' series, children's and teen books by ...

; this makes Dhlomo's novel the first published black South African novel in English, even though Plaatje's ''Mhudi'' had been written first). He also wrote ''Native Life in South Africa'', which Neil Parsons describes as "one of the most remarkable books on Africa by one of the continent's most remarkable writers", and ''Boer War Diary'' that was first published 40 years after his death.

Performing

Plaatje made three visits to Britain. There he met many people of similar views. One was the cinema and theatrical impresarioGeorge Lattimore

George William Lattimore (1887 – after 1931) was an American lawyer, sports manager, manager of the Southern Syncopated Orchestra, and a theatrical and cinema impresario.

Early life

George Lattimore was born in New York City on March 27, 18 ...

who in 1923 was promoting with Pathé

Pathé SAS (; styled as PATHÉ!) is a French major film production and distribution company, owning a number of cinema chains through its subsidiary Pathé Cinémas and television networks across Europe.

It is the name of a network of Fren ...

, ''Cradle of the World'', the "most marvellous and thrilling travel film ever screened". In a letter to the pan-Africanist W. E. B. Du Bois

William Edward Burghardt Du Bois ( ; February 23, 1868 – August 27, 1963) was an American sociologist, socialist, historian, and Pan-Africanist civil rights activist.

Born in Great Barrington, Massachusetts, Du Bois grew up in a relativel ...

, Lattimore reported that he was having a "successful run" at the Philharmonic Hall in London. The show, which had the character of a revue, included live music and singing. Plaatje was recruited by Lattimore to take the role of an African tribesman.

Importantly, according to the SOAS University of London, this short-lived acting reflects a period of Plaatje's life where he was "desperately in need of money". Considering "Cradle of the World" and its simplistic depictions of indigenous culture, it is likely that Plaatje only would have participated if he desperately needed too. Plaatje, descended from the BaRong people of the Tswana-speaking nation; but was born and raised in a Lutheran Mission within the Orange Free State.

His recording of "Nkosi Sikelel' iAfrika

"" (, ) is a Christian hymn composed in 1897 by Enoch Sontonga, a Xhosa people, Xhosa clergyman at a Methodism, Methodist mission school near Johannesburg.

The song became a pan-African liberation song and versions of it were later adopted as ...

" with Sylvia Colenso at the piano is believed to be the earliest extant recording of what would become the national anthem of South Africa.

Personal life

Plaatje was a committed Christian, and organised a fellowship group called the Christian Brotherhood at Kimberley. He was married to Elizabeth Lilith M'belle. They had six children – Frederick York St Leger, Halley, Richard, Violet, Olive and Johannes Gutenberg. Plaatje's "Native Life" by some scholars has containing a described as paternalistic attitude towards women. One such chapter is 'Our Indebtedness to white women', which reflects notions of domesticity prevalent at the time. Nonetheless, challenging this view is TheBritish Newspaper Archive

The British Newspaper Archive website provides access to searchable digitized archives of British and Irish newspapers. It was launched in November 2011.

History

The British Library's Newspapers section was based in Colindale in north London ...

's digitalisation of 'The International Woman Suffrage News'.

In July 1923, a 'Sol Plaatje, Esq' donated 4 shillings and 3 pence towards for the international suffragette cause. Notably, 1923 was a particularly bad time financially, yet Plaatje made this donation. While it is not clear why he made this donation, it does raise a few important questions regarding the tone in which "Our Indebtedness to White Women" forms.

What is clear is that white Women played various but important roles in his life. Firstly, Mrs Wilhelmine Westphal, who, upon her husband's increasing role in the Mission's governance, took a larger role in young Plaatje's tutoring. Secondly, Georgiana Solomon

Georgiana Margaret Solomon (née Thomson; born 18 August 1844 – 24 June 1933) was a British educator and campaigner, involved with a wide range of causes in Britain and South Africa. She and her only surviving daughter, Daisy Solomon, were suf ...

and Jane Cobden

Emma Jane Catherine Cobden (28 April 1851 – 7 July 1947) was a British Liberal politician who was active in many radical causes. A daughter of the Victorian reformer and statesman Richard Cobden, she was an early proponent of women's r ...

, interceded on Plaatje's behalf within the So-called Aborigines' Protection Society

The Aborigines' Protection Society (APS) was an international human rights organisation founded in 1837,

...

, to try and win him an audience, which triggered their expulsion. Thirdly, when he was writing "Native Life", Landlady Alice Timerberlake English Heritage. "Solomon T. Plaatje." Accessed February 2, 2024.https://www.english-heritage.org.uk/visit/blue-plaques/solomon-plaatje/. did not chase the cash-strapped Plaatje for rent, allowing him to prioritise raising funds to publish "Native Life". Returning back to Plaatje's donation, Mrs G. M. Solomon appears on the same donation sheet.

Plaatje died of ...

pneumonia

Pneumonia is an Inflammation, inflammatory condition of the lung primarily affecting the small air sacs known as Pulmonary alveolus, alveoli. Symptoms typically include some combination of Cough#Classification, productive or dry cough, ches ...

at Pimville, Johannesburg

Johannesburg ( , , ; Zulu language, Zulu and Xhosa language, Xhosa: eGoli ) (colloquially known as Jozi, Joburg, Jo'burg or "The City of Gold") is the most populous city in South Africa. With 5,538,596 people in the City of Johannesburg alon ...

on 19 June 1932 aged 55, and was buried in Kimberley. Over a thousand people attended the funeral.

Recognition and legacy

* 1935: three years after his death, a tombstone was erected over Plaatje's grave with the inscription: "''I Khutse Morolong: Modiredi Wa Afrika – Rest in Peace Morolong, You Servant of Africa''". Decades passed before Plaatje began to receive the recognition he deserved. "Much of what he strove for came to nought," writes his biographer Brian Willan; "his political career was gradually forgotten, his manuscripts were lost or destroyed, his published books largely unread. His novel ''Mhudi'' formed part of no literary tradition, and was long regarded as little more than a curiosity." * 1970s: interest was stirred in Plaatje's journalistic and literary legacy through the work ofJohn Comaroff

John L. Comaroff (born 1 January 1945) is a retired professor of African and African American Studies and of anthropology. He is recognized for his study of African and African-American society. Comaroff and his wife, anthropologist Jean Com ...

(who edited for publication ''The Boer War Diary of Sol T. Plaatje'', and by Tim Couzens and Stephen Gray (who focused attention on Sol Plaatje's novel, ''Mhudi'')

* 1978: ''Mhudi'' was re-published under the editorial guidance of Stephen Gray

* 1982: Plaatje's ''Native Life in South Africa: Before and Since the European War and the Boer Rebellion'' (1916) was re-published by Ravan Press.

* 1982: the African Writers Association instituted a Sol Plaatje Prose Award (alongside the H. I. E. and R. R. R. Dhlomo Drama Award and the S. E. K. Mqhayi Poetry Award).

* 1984: Brian Willan published his biography, ''Sol Plaatje: South African Nationalist, 1876–1932''.

* 1991: The Sol Plaatje Educational Trust and Museum, housed in Plaatje's Kimberley home at 32 Angel Street, was opened, actively furthering his written legacy.Department of Basic Education: Sol Plaatje House: explanation written by Dr Karen Haire for the Sol Plaatje Educational Trust, 32 Angel Street, Kimberley, 8301retrieved 26 July 2013. * 1992: the house at 32 Angel Street in Kimberley, where Plaatje spent his last years, was declared a national monument (now a provincial heritage site). It continues as the Sol Plaatje Museum and Library, run by the Sol Plaatje Educational Trust, with donor funding. In the 2000s the Sol Plaatje Educational Trust has published Plaatje biographies by Maureen Rall and

Sabata-Mpho Mokae

Sabata-Mpho Mokae is an academic, novelist and translator from South Africa who writes in Setswana and English. He is the author of a biography: ''The Story of Sol T. Plaatje,'' published in 2010 by the Sol Plaatje Educational Trust, in which the ...

.

* circa 1995: the Sol Plaatje Municipality (Kimberley

Kimberly or Kimberley may refer to:

Places and historical events

Australia

Queensland

* Kimberley, Queensland, a coastal locality in the Shire of Douglas

South Australia

* County of Kimberley, a cadastral unit in South Australia

Ta ...

) in South Africa's Northern Cape Province

The Northern Cape ( ; ; ) is the largest and most sparsely populated province of South Africa. It was created in 1994 when the Cape Province was split up. Its capital is Kimberley. It includes the Kalahari Gemsbok National Park, part of the Kga ...

was named in Plaatje's honour.

* 1996: ''Sol Plaatje: Selected writings'', ed. Brian Willan, is published by the University of Witwatersrand

The University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg (), commonly known as Wits University or Wits, is a multi-campus public research university situated in the northern areas of central Johannesburg, South Africa. The university has its roots in ...

Press.

* 1998: an honorary doctorate was posthumously conferred on Plaatje by the University of the North-West

The North-West University (NWU) is a public research university located on three campuses in Potchefstroom, Mahikeng and Vanderbijlpark in South Africa. The university came into existence through the merger in 2004 of the Potchefstroom Univers ...

, with several of his descendants present.

* 1998: Plaatje's grave in West End Cemetery, Kimberley, was declared a national monument (now a provincial heritage site). It was only the second grave in South African history to be awarded national monument status.

* 2000: The Diamond Fields Advertiser launches the Sol T Plaatje Memorial Award to honour the top Setswana and top English matriculant each year in the Northern Cape. The first recipients are Claire Reddie (English) and Neo Molefi (Setswana).

* 2000: the Department of Education building in Pretoria was renamed Sol Plaatje House, on 15 June 2000, "in honour of this political giant and consummate educator."

* 2000: the South African Post Office issued a series of stamps featuring writers of the Boer War

The Second Boer War (, , 11 October 189931 May 1902), also known as the Boer War, Transvaal War, Anglo–Boer War, or South African War, was a conflict fought between the British Empire and the two Boer republics (the South African Republic an ...

, with Plaatje appearing on the 1.30 Rand

The RAND Corporation, doing business as RAND, is an American nonprofit global policy think tank, research institute, and public sector consulting firm. RAND engages in research and development (R&D) in several fields and industries. Since the ...

stamp. The series also includes Sir Arthur Conan Doyle

Sir Arthur Ignatius Conan Doyle (22 May 1859 – 7 July 1930) was a British writer and physician. He created the character Sherlock Holmes in 1887 for ''A Study in Scarlet'', the first of four novels and fifty-six short stories about Hol ...

, Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 1874 – 24 January 1965) was a British statesman, military officer, and writer who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1940 to 1945 (Winston Churchill in the Second World War, ...

, Johanna Brandt

Johanna Brandt (18 November 1876 in Heidelberg, South African Republic – 13 January 1964 in Newlands, Cape Town) was a South African propagandist of Afrikaner nationalism, spy during the Boer War, prophet and writer on health subjects.

Biog ...

and the Anglo-Boer War Medal.

* 2000: the African National Congress initiated the Sol Plaatje Award, one of a number of annual achievement awards. The Sol Plaatje Award recognises the best performing ANC branch.

* 2002: the Sol Plaatje Media Leadership Institute was established within Rhodes University's Department of Journalism and Media Studies.

* 2004: Order of Luthuli

The Order of Luthuli is a South African honour. It was instituted on 30 November 2003 and is awarded by the President of South Africa for contributions to the struggle for democracy, human rights, nation-building, justice, or peace and conflict ...

in gold

* 2005: the Saulspoort Dam was renamed Sol Plaatje Dam, although not in honour of Sol Plaatje the man but in remembrance of 41 Sol Plaatje Municipal workers drowned in a bus disaster there on 1 May 2003.

* 2007: the Sol Plaatje Prize for Translation was instituted by the English Academy of South Africa, awarded bi-annually for translation of prose or poetry into English from any of the other South African official languages.

* 2009: the Sol Plaatje Power Station at the Sol Plaatje Dam near Bethlehem, Free State

Bethlehem is a city in the eastern Free State province of South Africa that is situated on the Liebenbergs River (also called Liebenbergs Vlei) along a fertile valley just north of the Rooiberg Mountains on the N5 road. It is the fastest growi ...

was commissioned – the first commercial small hydro power station constructed in South Africa in 22 years.

* 2009: Sol Plaatje was honoured in the Posthumous Literary Award given by the South African Literary Awards

The South African Literary Awards (SALA) have been awarded annually since 2005 to exceptional South African writers. Founded by the wRiteassociates, in partnership with the national Department of Arts and Culture (DAC), the awards "pay tribute t ...

.

* 2010: the first Plaatje Festival, held in Mahikeng

Mahikeng ( Tswana for "Place of Rocks"), formerly known as Mafikeng and alternatively known as Mafeking (, ), is the capital city of the North West province of South Africa.

Close to South Africa's border with Botswana, Mafikeng is northeast ...

, hosted by the North West Province Departments of Sport, Arts and Culture and of Education, on 5 and 6 November 2010. It brought together Plaatje and Molema descendants, poets, journalists, scholars, language practitioners, educators, and learners, who "paid tribute to this brilliant Setswana man of letters."

* 2010: a statue of Sol Plaatje, seated and writing at a desk, was unveiled in Kimberley by South African President Jacob Zuma

Jacob Gedleyihlekisa Zuma (; born 12 April 1942) is a South African politician who served as the fourth president of South Africa from 2009 to 2018. He is also referred to by his initials JZ and clan names Nxamalala and Msholozi. Zuma was a for ...

on 9 January 2010, the 98th anniversary of the founding of the African National Congress

The African National Congress (ANC) is a political party in South Africa. It originated as a liberation movement known for its opposition to apartheid and has governed the country since 1994, when the 1994 South African general election, fir ...

. By sculptor Johan Moolman, it was erected at Kimberley's Civic Centre, formerly the Malay Camp, and situated approximately where Plaatje had his printing press in 1910 – 13.

* 2011: the European Union Sol Plaatje Poetry Competition was inaugurated, honouring "the spirit of the legendary intellectual giant, Sol Plaatje, the activist, linguist and translator, novelist, journalist and leader." Winners' work has been published in an annual anthology since the competition's inauguration.

* 2012: Seetsele Modiri Molema's ''Lover of his people: a biography of Sol Plaatje'' was published. Translated and edited by D. S. Matjila and Karen Haire, the manuscript, ''Sol T. Plaatje: Morata Wabo'', dating from the 1960s, was the first Plaatje biography written in his mother tongue, Setswana

Tswana, also known by its native name Setswana, is a Bantu language indigenous to Southern Africa and spoken by about 8.2 million people. It is closely related to the Northern Sotho and Southern Sotho languages, as well as the Kgalaga ...

, and the only book-length biography written by someone who actually knew Plaatje.

* 2013: the naming of the Sol Plaatje University

Sol Plaatje University is a Public university, public university located in Kimberley, Northern Cape, Kimberley, South Africa. Established in 2014, it is the first and only university located in the Northern Cape province.

History

The idea of ...

in Kimberley, which opened in 2014, was announced by President Jacob Zuma

Jacob Gedleyihlekisa Zuma (; born 12 April 1942) is a South African politician who served as the fourth president of South Africa from 2009 to 2018. He is also referred to by his initials JZ and clan names Nxamalala and Msholozi. Zuma was a for ...

on 25 July 2013.

* 2013: the renaming of UNISA's Florida Campus Library as the Sol Plaatje Library, unveiled on 30 July 2013.

* Schools in Kimberley

Kimberly or Kimberley may refer to:

Places and historical events

Australia

Queensland

* Kimberley, Queensland, a coastal locality in the Shire of Douglas

South Australia

* County of Kimberley, a cadastral unit in South Australia

Ta ...

and Mahikeng

Mahikeng ( Tswana for "Place of Rocks"), formerly known as Mafikeng and alternatively known as Mafeking (, ), is the capital city of the North West province of South Africa.

Close to South Africa's border with Botswana, Mafikeng is northeast ...

are named after Sol Plaatje.

* 2015: Anglo-Boer War Museum opens a new addition to the museum named; The Sol Plaatje Hall, ddedicated to the role of black and coloured people on both the British and Boer sides during the Second Boer War

The Second Boer War (, , 11 October 189931 May 1902), also known as the Boer War, Transvaal War, Anglo–Boer War, or South African War, was a conflict fought between the British Empire and the two Boer republics (the South African Republic and ...

.

* 2016: ''Sol Plaatje's Native Life in South Africa: Past and Present'' by Brian Willan, Janet Remmington and Bhekizizwe Peterson is published by Wits University

The University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg (), commonly known as Wits University or Wits, is a multi-campus public research university situated in the northern areas of central Johannesburg, South Africa. The university has its roots in ...

Press and goes on to win 'Best Non-Fiction Edited Volume' in the 2018 NIHSS Awards.

* 2018: ''Sol Plaatje: A life of Solomon Tshekisho Plaatje 1876 – 1932'' by Brian Willan is published by Jacana Media and goes on to win 'Best Non-Fiction Biography' in the 2020 NIHSS Awards.

* 2020: ''Sol Plaatje’s Mhudi: History, Criticism, Celebration'', a collection of essays edited by Sabata-Mpho Mokae

Sabata-Mpho Mokae is an academic, novelist and translator from South Africa who writes in Setswana and English. He is the author of a biography: ''The Story of Sol T. Plaatje,'' published in 2010 by the Sol Plaatje Educational Trust, in which the ...

and Brian Willan is published by Jacana Media.

Original writing

* with John L. Comaroff * ''The Essential Interpreter'' (circa 1909): an essay * * * * * ''Bantu Folk-Tales and Poems'' * ed. Brian WillanTranslations of Shakespeare

* ''Dikhontsho tsa bo-Juliuse Kesara'' – ''Julius Caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar (12 or 13 July 100 BC – 15 March 44 BC) was a Roman general and statesman. A member of the First Triumvirate, Caesar led the Roman armies in the Gallic Wars before defeating his political rival Pompey in Caesar's civil wa ...

''

* ''Diphosho-phosho'' – ''The Comedy of Errors

''The Comedy of Errors'' is one of William Shakespeare's early plays. It is his shortest and one of his most farcical comedies, with a major part of the humour coming from slapstick and mistaken identity, in addition to puns and word play ...

''

Both of these were called "remarkably good" translations in a 1949 study.

Notes

References

Other relevant literature

* * *Couzens, Tim. 1987. "Sol T. Plaatje and the First South African Epic". ''English in Africa'' 14: 41–65. * * * * Matjila, D. S. and K. Haire. 2004. Echoes of and affinities with Bogosi (kingship) in the works of Sol T. Plaatje. ''South African Journal of African Languages'', Volume 34, 2014, Issue 1 * * * * * * * *Further reading

* * * * * * * (US edition published 2019.)External links

* * * at the Anglo-Boer War Museum/War Museum of the Boer Republics. * * * Audio Recordings: ** ** Audio from South African Music Archive Project. * Archive papers comprising biographical material, papers, notes, correspondence and photographs of Solomon Tshekisho Plaatje: ** ** Digitised material from the collection. {{DEFAULTSORT:Plaatje, Sol 1876 births 1932 deaths People from Tokologo Local Municipality South African Tswana people South African Christians African National Congress politicians South African newspaper editors Deaths from pneumonia in South Africa Proverb scholars Tswana-language writers Translators of William Shakespeare Recipients of the Order of Luthuli 20th-century South African journalists