socialistic on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Socialism is a

Socialist models and ideas espousing common or public ownership have existed since antiquity. The economy of the 3rd century BCE

Socialist models and ideas espousing common or public ownership have existed since antiquity. The economy of the 3rd century BCE

The Paris Commune was a government that ruled Paris from 18 March (formally, from 28 March) to 28 May 1871. The Commune was the result of an uprising in Paris after France was defeated in the Franco-Prussian War. The Commune elections were held on 26 March. They elected a Commune council of 92 members, one member for each 20,000 residents.

Because the Commune was able to meet on fewer than 60 days in total, only a few decrees were actually implemented. These included the

The Paris Commune was a government that ruled Paris from 18 March (formally, from 28 March) to 28 May 1871. The Commune was the result of an uprising in Paris after France was defeated in the Franco-Prussian War. The Commune elections were held on 26 March. They elected a Commune council of 92 members, one member for each 20,000 residents.

Because the Commune was able to meet on fewer than 60 days in total, only a few decrees were actually implemented. These included the

In 1864, the First International was founded in London. It united diverse revolutionary currents, including socialists such as the French followers of Proudhon, Blanquists, Philadelphes, English

In 1864, the First International was founded in London. It united diverse revolutionary currents, including socialists such as the French followers of Proudhon, Blanquists, Philadelphes, English

"Michael Bakunin – A Biographical Sketch"

/ref>

at ''

By 1917, the patriotism of

By 1917, the patriotism of

left-wing

Left-wing politics describes the range of political ideologies that support and seek to achieve social equality and egalitarianism, often in opposition to social hierarchy. Left-wing politics typically involve a concern for those in so ...

economic philosophy

An economic ideology is a set of views forming the basis of an ideology on how the economy should run. It differentiates itself from economic theory in being normative rather than just explanatory in its approach, whereas the aim of economic the ...

and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership

Social ownership is the appropriation of the surplus product, produced by the means of production, or the wealth that comes from it, to society as a whole. It is the defining characteristic of a socialist economic system. It can take the form ...

of the means of production

The means of production is a term which describes land, Work (human activity), labor and capital (economics), capital that can be used to produce products (such as goods or Service (economics), services); however, the term can also refer to anyth ...

as opposed to private ownership

Private property is a legal designation for the ownership of property by non-governmental legal entities. Private property is distinguishable from public property and personal property, which is owned by a state entity, and from collective or c ...

. As a term, it describes the economic

An economy is an area of the production, distribution and trade, as well as consumption of goods and services. In general, it is defined as a social domain that emphasize the practices, discourses, and material expressions associated with t ...

, political

Politics (from , ) is the set of activities that are associated with making decisions in groups, or other forms of power relations among individuals, such as the distribution of resources or status. The branch of social science that studi ...

and social

Social organisms, including human(s), live collectively in interacting populations. This interaction is considered social whether they are aware of it or not, and whether the exchange is voluntary or not.

Etymology

The word "social" derives from ...

theories and movements associated with the implementation of such systems. Social ownership can be state/public, community

A community is a social unit (a group of living things) with commonality such as place, norms, religion, values, customs, or identity. Communities may share a sense of place situated in a given geographical area (e.g. a country, villag ...

, collective, cooperative

A cooperative (also known as co-operative, co-op, or coop) is "an autonomous association of persons united voluntarily to meet their common economic, social and cultural needs and aspirations through a jointly owned and democratically-contro ...

, or employee

Employment is a relationship between two parties regulating the provision of paid labour services. Usually based on a contract, one party, the employer, which might be a corporation, a not-for-profit organization, a co-operative, or any o ...

. While no single definition encapsulates the many types of socialism

Types of socialism include a range of economic and social systems characterised by social ownership and democratic controlArnold, N. Scott (1998). ''The Philosophy and Economics of Market Socialism: A Critical Study''. Oxford University Press. p ...

, social ownership is the one common element. Different types of socialism vary based on the role of markets and planning in resource allocation, on the structure of management in organizations, and from below or from above approaches, with some socialists favouring a party, state, or technocratic-driven approach. Socialists disagree on whether government, particularly existing government, is the correct vehicle for change.

Socialist systems are divided into non-market and market forms. Non-market socialism substitutes factor market

In economics, a factor market is a market where factors of production are bought and sold. Factor markets allocate factors of production, including land, labour and capital, and distribute income to the owners of productive resources, such as wag ...

s and often money

Money is any item or verifiable record that is generally accepted as payment for goods and services and repayment of debts, such as taxes, in a particular country or socio-economic context. The primary functions which distinguish money ar ...

with integrated economic planning and engineering or technical criteria based on calculation performed in-kind, thereby producing a different economic mechanism that functions according to different economic laws and dynamics than those of capitalism

Capitalism is an economic system based on the private ownership of the means of production and their operation for profit. Central characteristics of capitalism include capital accumulation, competitive markets, price system, private ...

. A non-market socialist system seeks to eliminate the perceived inefficiencies, irrationalities, unpredictability, and crises

A crisis (plural, : crises; adjectival form, : critical) is either any event or period that will (or might) lead to an unstable and dangerous situation affecting an individual, group, or all of society. Crises are negative changes in the human ...

that socialists traditionally associate with capital accumulation

Capital accumulation is the dynamic that motivates the pursuit of profit, involving the investment of money or any financial asset with the goal of increasing the initial monetary value of said asset as a financial return whether in the fo ...

and the profit

Profit may refer to:

Business and law

* Profit (accounting), the difference between the purchase price and the costs of bringing to market

* Profit (economics), normal profit and economic profit

* Profit (real property), a nonpossessory inter ...

system in capitalism. By contrast, market socialism

Market socialism is a type of economic system involving the public, cooperative, or social ownership of the means of production in the framework of a market economy, or one that contains a mix of worker-owned, nationalized, and privately owne ...

retains the use of monetary prices, factor markets and in some cases the profit motive

In economics, the profit motive is the motivation of firms that operate so as to maximize their profits. Mainstream microeconomic theory posits that the ultimate goal of a business is "to make money" - not in the sense of increasing the firm's ...

, with respect to the operation of socially owned enterprises and the allocation of capital goods between them. Profits generated by these firms would be controlled directly by the workforce of each firm or accrue to society at large in the form of a social dividend

The social dividend is the return on the capital assets and natural resources owned by society in a socialist economy. The concept notably appears as a key characteristic of market socialism, where it takes the form of a dividend payment to eac ...

. Anarchism and libertarian socialism

Libertarian socialism, also known by various other names, is a left-wing,Diemer, Ulli (1997)"What Is Libertarian Socialism?" The Anarchist Library. Retrieved 4 August 2019. anti-authoritarian, anti-statist and libertarianLong, Roderick T. (2 ...

oppose the use of the state as a means to establish socialism, favouring decentralisation

Decentralization or decentralisation is the process by which the activities of an organization, particularly those regarding planning and decision making, are distributed or delegated away from a central, authoritative location or group.

Conce ...

above all, whether to establish non-market socialism or market socialism.

Socialist politics has been both internationalist and nationalist; organised through political parties and opposed to party politics; at times overlapping with trade unions and at other times independent and critical of them, and present in both industrialised and developing nations. Social democracy

Social democracy is a political, social, and economic philosophy within socialism that supports political and economic democracy. As a policy regime, it is described by academics as advocating economic and social interventions to prom ...

originated within the socialist movement, supporting economic

An economy is an area of the production, distribution and trade, as well as consumption of goods and services. In general, it is defined as a social domain that emphasize the practices, discourses, and material expressions associated with t ...

and social interventions to promote social justice

Social justice is justice in terms of the distribution of wealth, Equal opportunity, opportunities, and Social privilege, privileges within a society. In Western Civilization, Western and Culture of Asia, Asian cultures, the concept of social ...

. While retaining socialism as a long-term goal, since the post-war period it has come to embrace a Keynesian

Keynesian economics ( ; sometimes Keynesianism, named after British economist John Maynard Keynes) are the various macroeconomic theories and models of how aggregate demand (total spending in the economy) strongly influences economic output ...

mixed economy

A mixed economy is variously defined as an economic system blending elements of a market economy with elements of a planned economy, markets with state interventionism, or private enterprise with public enterprise. Common to all mixed econo ...

within a predominantly developed capitalist market economy

A market economy is an economic system in which the decisions regarding investment, production and distribution to the consumers are guided by the price signals created by the forces of supply and demand, where all suppliers and consumers ar ...

and liberal democratic

Liberal democracy is the combination of a liberal political ideology that operates under an indirect democratic form of government. It is characterized by elections between multiple distinct political parties, a separation of powers into di ...

polity that expands state intervention to include income redistribution

Redistribution of income and wealth is the transfer of income and wealth (including physical property) from some individuals to others through a social mechanism such as taxation, welfare, public services, land reform, monetary policies, conf ...

, regulation

Regulation is the management of complex systems according to a set of rules and trends. In systems theory, these types of rules exist in various fields of biology

Biology is the scientific study of life. It is a natural science with a ...

, and a welfare state

A welfare state is a form of government in which the state (or a well-established network of social institutions) protects and promotes the economic and social well-being of its citizens, based upon the principles of equal opportunity, equitab ...

. Economic democracy proposes a sort of market socialism, with more democratic control of companies, currencies, investments and natural resources.

The socialist political movement includes a set of political philosophies that originated in the revolutionary movements of the mid-to-late 18th century and out of concern for the social problems that were associated with capitalism. By the late 19th century, after the work of Karl Marx

Karl Heinrich Marx (; 5 May 1818 – 14 March 1883) was a German philosopher, economist, historian, sociologist, political theorist, journalist, critic of political economy, and socialist revolutionary. His best-known titles are the 1848 ...

and his collaborator Friedrich Engels

Friedrich Engels ( ,"Engels"

'' opposition to capitalism Anti-capitalism is a political ideology and movement encompassing a variety of attitudes and ideas that oppose capitalism. In this sense, anti-capitalists are those who wish to replace capitalism with another type of economic system, such as so ...

and advocacy for a '' opposition to capitalism Anti-capitalism is a political ideology and movement encompassing a variety of attitudes and ideas that oppose capitalism. In this sense, anti-capitalists are those who wish to replace capitalism with another type of economic system, such as so ...

post-capitalist

Post-capitalism is a state in which the economic systems of the world can no longer be described as forms of capitalism. Various individuals and political ideologies have speculated on what would define such a world. According to classical Mar ...

system based on some form of social ownership of the means of production. By the early 1920s, communism

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society ...

and social democracy had become the two dominant political tendencies within the international socialist movement, with socialism itself becoming the most influential secular movement of the 20th century. Socialist parties and ideas remain a political force with varying degrees of power and influence on all continents, heading national governments in many countries around the world. Today, many socialists have also adopted the causes of other social movements such as feminism

Feminism is a range of socio-political movements and ideologies that aim to define and establish the political, economic, personal, and social equality of the sexes. Feminism incorporates the position that society prioritizes the male po ...

, environmentalism

Environmentalism or environmental rights is a broad Philosophy of life, philosophy, ideology, and social movement regarding concerns for environmental protection and improvement of the health of the environment (biophysical), environment, par ...

, and progressivism

Progressivism holds that it is possible to improve human societies through political action. As a political movement, progressivism seeks to advance the human condition through social reform based on purported advancements in science, tec ...

.

While the emergence of the Soviet Union as the world's first nominally socialist state

A socialist state, socialist republic, or socialist country, sometimes referred to as a workers' state or workers' republic, is a sovereign state constitutionally dedicated to the establishment of socialism. The term ''communist state'' is ofte ...

led to socialism's widespread association with the Soviet economic model

Soviet-type economic planning (STP) is the specific model of centralized planning employed by Marxist–Leninist socialist states modeled on the economy of the Soviet Union (USSR).

The post-''perestroika'' analysis of the system of the Sov ...

, several scholars posit that in practice, the model functioned as a form of state capitalism

State capitalism is an economic system in which the state undertakes business and commercial (i.e. for-profit) economic activity and where the means of production are nationalized as state-owned enterprises (including the processes of capit ...

. See also Several academics, political commentators, and scholars have distinguished between authoritarian socialist and democratic socialist

Democratic socialism is a left-wing political philosophy that supports political democracy and some form of a socially owned economy, with a particular emphasis on economic democracy, workplace democracy, and workers' self-management withi ...

states, with the first representing the Eastern Bloc

The Eastern Bloc, also known as the Communist Bloc and the Soviet Bloc, was the group of socialist states of Central and Eastern Europe, East Asia, Southeast Asia, Africa, and Latin America under the influence of the Soviet Union that existed du ...

and the latter representing Western Bloc

The Western Bloc, also known as the Free Bloc, the Capitalist Bloc, the American Bloc, and the NATO Bloc, was a coalition of countries that were officially allied with the United States during the Cold War of 1947–1991. It was spearheaded b ...

countries which have been democratically governed by socialist parties such as Britain, France, Sweden, and Western countries in general, among others. However, following the end of the Cold War, many of these countries have moved away from socialism as a neoliberal

Neoliberalism (also neo-liberalism) is a term used to signify the late 20th century political reappearance of 19th-century ideas associated with free-market capitalism after it fell into decline following the Second World War. A prominent fa ...

consensus replaced the social democratic consensus in the advanced capitalist world.

Etymology

For Andrew Vincent, " e word 'socialism' finds its root in the Latin , which means to combine or to share. The related, more technical term in Roman and then medieval law was . This latter word could mean companionship and fellowship as well as the more legalistic idea of a consensual contract between freemen". Initial use of ''socialism'' was claimed by Pierre Leroux, who alleged he first used the term in the Parisian journal in 1832. Leroux was a follower ofHenri de Saint-Simon

Claude Henri de Rouvroy, comte de Saint-Simon (17 October 1760 – 19 May 1825), often referred to as Henri de Saint-Simon (), was a French political, economic and socialist theorist and businessman whose thought had a substantial influence on p ...

, one of the founders of what would later be labelled utopian socialism

Utopian socialism is the term often used to describe the first current of modern socialism and socialist thought as exemplified by the work of Henri de Saint-Simon, Charles Fourier, Étienne Cabet, and Robert Owen. Utopian socialism is ofte ...

. Socialism contrasted with the liberal doctrine of individualism

Individualism is the moral stance, political philosophy, ideology and social outlook that emphasizes the intrinsic worth of the individual. Individualists promote the exercise of one's goals and desires and to value independence and self-relia ...

that emphasized the moral worth of the individual whilst stressing that people act or should act as if they are in isolation from one another. The original utopian socialists condemned this doctrine of individualism for failing to address social concerns during the Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution was the transition to new manufacturing processes in Great Britain, continental Europe, and the United States, that occurred during the period from around 1760 to about 1820–1840. This transition included going f ...

, including poverty

Poverty is the state of having few material possessions or little income. Poverty can have diverse < ...

, oppression

Oppression is malicious or unjust treatment or exercise of power, often under the guise of governmental authority or cultural opprobrium. Oppression may be overt or covert, depending on how it is practiced. Oppression refers to discrimination w ...

, and vast wealth inequality

The distribution of wealth is a comparison of the wealth of various members or groups in a society. It shows one aspect of economic inequality or heterogeneity in economics, economic heterogeneity.

The distribution of wealth differs from the i ...

. They viewed their society as harming community life by basing society on competition. They presented socialism as an alternative to liberal individualism based on the shared ownership of resources. Saint-Simon proposed economic planning, scientific administration and the application of scientific understanding to the organisation of society. By contrast, Robert Owen

Robert Owen (; 14 May 1771 – 17 November 1858) was a Welsh textile manufacturer, philanthropist and social reformer, and a founder of utopian socialism and the cooperative movement. He strove to improve factory working conditions, promoted e ...

proposed to organise production and ownership via cooperative

A cooperative (also known as co-operative, co-op, or coop) is "an autonomous association of persons united voluntarily to meet their common economic, social and cultural needs and aspirations through a jointly owned and democratically-contro ...

s. ''Socialism'' is also attributed in France to Marie Roch Louis Reybaud

Marie Roch Louis Reybaud (15 August 1799 – 26 or 28 October 1879) was a French writer, political economist and politician. He was born in Marseille.

After travelling in the Levant and in India, he settled in Paris in 1829. Besides writing for ...

while in Britain it is attributed to Owen, who became one of the fathers of the cooperative movement.

The definition and usage of ''socialism'' settled by the 1860s, replacing ''associationist'', ''co-operative'', and ''mutualist'' that had been used as synonyms while ''communism'' fell out of use during this period. An early distinction between ''communism

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society ...

'' and ''socialism'' was that the latter aimed to only socialise production while the former aimed to socialise both production and consumption (in the form of free access to final goods). By 1888, Marxists

Marxism is a left-wing to far-left method of socioeconomic analysis that uses a materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to understand class relations and social conflict and a dialecti ...

employed ''socialism'' in place of ''communism'' as the latter had come to be considered an old-fashioned synonym for ''socialism''. It was not until after the Bolshevik Revolution

The October Revolution,. officially known as the Great October Socialist Revolution. in the Soviet Union, also known as the Bolshevik Revolution, was a revolution in Russia led by the Bolshevik Party of Vladimir Lenin that was a key mome ...

that ''socialism'' was appropriated by Vladimir Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov. ( 1870 – 21 January 1924), better known as Vladimir Lenin,. was a Russian revolutionary, politician, and political theorist. He served as the first and founding head of government of Soviet Russia from 1917 to 1 ...

to mean a stage between capitalism

Capitalism is an economic system based on the private ownership of the means of production and their operation for profit. Central characteristics of capitalism include capital accumulation, competitive markets, price system, private ...

and communism. He used it to defend the Bolshevik program from Marxist criticism that Russia's productive forces

Productive forces, productive powers, or forces of production (German: ''Produktivkräfte'') is a central idea in Marxism and historical materialism.

In Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels' own critique of political economy, it refers to the combinat ...

were not sufficiently developed for communism. The distinction between ''communism'' and ''socialism'' became salient in 1918 after the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party

The Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP; in , ''Rossiyskaya sotsial-demokraticheskaya rabochaya partiya (RSDRP)''), also known as the Russian Social Democratic Workers' Party or the Russian Social Democratic Party, was a socialist po ...

renamed itself to the All-Russian Communist Party

"Hymn of the Bolshevik Party"

, headquarters = 4 Staraya Square, Moscow

, general_secretary = Vladimir Lenin (first)Mikhail Gorbachev (last)

, founded =

, banned =

, founder = Vladimir Lenin

, newspaper ...

, interpreting ''communism'' specifically to mean socialists who supported the politics and theories of Bolshevism

Bolshevism (from Bolshevik) is a revolutionary socialist current of Soviet Marxist–Leninist political thought and political regime associated with the formation of a rigidly centralized, cohesive and disciplined party of social revolution, ...

, Leninism

Leninism is a political ideology developed by Russian Marxist revolutionary Vladimir Lenin that proposes the establishment of the dictatorship of the proletariat led by a revolutionary vanguard party as the political prelude to the establishme ...

and later that of Marxism–Leninism

Marxism–Leninism is a List of communist ideologies, communist ideology which was the main communist movement throughout the 20th century. Developed by the Bolsheviks, it was the state ideology of the Soviet Union, its Soviet satellite state ...

, although communist parties

A communist party is a political party that seeks to realize the Socioeconomics, socio-economic goals of communism. The term ''communist party'' was popularized by the title of ''The Communist Manifesto, The Manifesto of the Communist Party'' ( ...

continued to describe themselves as socialists dedicated to socialism. According to ''The Oxford Handbook of Karl Marx'', "Marx used many terms to refer to a post-capitalist society—positive humanism, socialism, Communism, realm of free individuality, free association of producers, etc. He used these terms completely interchangeably. The notion that 'socialism' and 'Communism' are distinct historical stages is alien to his work and only entered the lexicon of Marxism after his death".

In Christian Europe, communists were believed to have adopted atheism

Atheism, in the broadest sense, is an absence of belief in the existence of deities. Less broadly, atheism is a rejection of the belief that any deities exist. In an even narrower sense, atheism is specifically the position that there no ...

. In Protestant England, ''communism'' was too close to the Roman Catholic

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*''Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a letter ...

communion rite, hence ''socialist'' was the preferred term. Engels wrote that in 1848, when ''The Communist Manifesto

''The Communist Manifesto'', originally the ''Manifesto of the Communist Party'' (german: Manifest der Kommunistischen Partei), is a political pamphlet written by German philosophers Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. Commissioned by the Comm ...

'' was published, socialism was respectable in Europe while communism was not. The Owenites in England and the Fourierists

Fourierism () is the systematic set of economic, political, and social beliefs first espoused by French intellectual Charles Fourier (1772–1837). Based upon a belief in the inevitability of communal associations of people who worked and lived to ...

in France were considered respectable socialists while working-class movements that "proclaimed the necessity of total social change" denoted themselves ''communists''. This branch of socialism produced the communist work of Étienne Cabet

Étienne Cabet (; January 1, 1788 – November 9, 1856) was a French philosophy, French philosopher and utopian socialist who founded the Icarians, Icarian movement. Cabet became the most popular socialist advocate of his day, with a special appe ...

in France and Wilhelm Weitling in Germany. British moral philosopher John Stuart Mill discussed a form of economic socialism within a liberal context that would later be known as liberal socialism

Liberal socialism is a political philosophy that incorporates liberal principles to socialism. This synthesis sees liberalism as the political theory that takes the inner freedom of the human spirit as a given and adopts liberty as the goal, ...

. In later editions of his ''Principles of Political Economy

''Principles of Political Economy'' (1848) by John Stuart Mill was one of the most important economics or political economy textbooks of the mid-nineteenth century. It was revised until its seventh edition in 1871, shortly before Mill's deat ...

'' (1848), Mill posited that "as far as economic theory was concerned, there is nothing in principle in economic theory that precludes an economic order based on socialist policies" and promoted substituting capitalist businesses with worker cooperative

A worker cooperative is a cooperative owned and self-managed by its workers. This control may mean a firm where every worker-owner participates in decision-making in a democratic fashion, or it may refer to one in which management is elected by ...

s. While democrats looked to the Revolutions of 1848

The Revolutions of 1848, known in some countries as the Springtime of the Peoples or the Springtime of Nations, were a series of political upheavals throughout Europe starting in 1848. It remains the most widespread revolutionary wave in Euro ...

as a democratic revolution

Democratic Revolution () is a Chilean centre-left to left-wing political party, founded in 2012 by some of the leaders of the 2011 Chilean student protests, most notably the current Deputy Giorgio Jackson, who is also the most popular public fi ...

which in the long run ensured liberty, equality, and fraternity, Marxists denounced it as a betrayal of working-class

The working class (or labouring class) comprises those engaged in manual-labour occupations or industrial work, who are remunerated via waged or salaried contracts. Working-class occupations (see also " Designation of workers by collar colo ...

ideals by a bourgeoisie indifferent to the proletariat

The proletariat (; ) is the social class of wage-earners, those members of a society whose only possession of significant economic value is their labour power (their capacity to work). A member of such a class is a proletarian. Marxist philo ...

.

History

Early socialism

Socialist models and ideas espousing common or public ownership have existed since antiquity. The economy of the 3rd century BCE

Socialist models and ideas espousing common or public ownership have existed since antiquity. The economy of the 3rd century BCE Mauryan Empire

The Maurya Empire, or the Mauryan Empire, was a geographically extensive Iron Age historical power in the Indian subcontinent based in Magadha, having been founded by Chandragupta Maurya in 322 BCE, and existing in loose-knit fashion until 1 ...

of India, an absolute monarchy, has been described by some scholars as "a socialized monarchy" and "a sort of state socialism" due to "nationalisation of industries". Other scholars have suggested that elements of socialist thought were present in the politics of classical Greek philosophers

Ancient Greek philosophy arose in the 6th century BC, marking the end of the Greek Dark Ages. Greek philosophy continued throughout the Hellenistic period and the period in which Greece and most Greek-inhabited lands were part of the Roman Empire ...

Plato

Plato ( ; grc-gre, Πλάτων ; 428/427 or 424/423 – 348/347 BC) was a Greek philosopher born in Athens during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. He founded the Platonist school of thought and the Academy, the first institutio ...

and Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical Greece, Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatet ...

. Mazdak the Younger (died c. 524 or 528 CE), a Persian communal proto-socialist, instituted communal possessions and advocated the public good. Abu Dharr al-Ghifari

Abu Dharr Al-Ghifari Al-Kinani (, '), also spelled Abu Tharr or Abu Zar, born Jundab ibn Junādah (), was the fourth or fifth person converting to Islam, and from the Muhajirun. He belonged to the Banu Ghifar, the Kinanah tribe. No date of bir ...

, a Companion

Companion may refer to:

Relationships Currently

* Any of several interpersonal relationships such as friend or acquaintance

* A domestic partner, akin to a spouse

* Sober companion, an addiction treatment coach

* Companion (caregiving), a caregive ...

of Muhammad

Muhammad ( ar, مُحَمَّد; 570 – 8 June 632 CE) was an Arab religious, social, and political leader and the founder of Islam. According to Islamic doctrine, he was a prophet divinely inspired to preach and confirm the monot ...

, is credited by multiple authors as a principal antecedent of Islamic socialism

Islamic socialism is a political philosophy that incorporates Islamic principles into socialism. As a term, it was coined by various Muslim leaders to describe a more spiritual form of socialism. Islamic socialists believe that the teachin ...

. The teachings of Jesus

Jesus, likely from he, יֵשׁוּעַ, translit=Yēšūaʿ, label=Hebrew/Aramaic ( AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesus Christ or Jesus of Nazareth (among other names and titles), was a first-century Jewish preacher and religiou ...

are frequently described as socialist, especially by Christian socialists. records that in the early church

Early Christianity (up to the First Council of Nicaea in 325) spread from the Levant, across the Roman Empire, and beyond. Originally, this progression was closely connected to already established Jewish centers in the Holy Land and the Je ...

in Jerusalem

Jerusalem (; he, יְרוּשָׁלַיִם ; ar, القُدس ) (combining the Biblical and common usage Arabic names); grc, Ἱερουσαλήμ/Ἰεροσόλυμα, Hierousalḗm/Hierosóluma; hy, Երուսաղեմ, Erusałēm. i ...

" one claimed that any of their possessions was their own", although the pattern soon disappears from church history

__NOTOC__

Church history or ecclesiastical history as an academic discipline studies the history of Christianity and the way the Christian Church has developed since its inception.

Henry Melvill Gwatkin defined church history as "the spiritual ...

except within monasticism. Christian socialism

Christian socialism is a religious and political philosophy that blends Christianity and socialism, endorsing left-wing politics and socialist economics on the basis of the Bible and the teachings of Jesus. Many Christian socialists believe cap ...

was one of the founding threads of the British Labour Party and is claimed to begin with the uprising

Rebellion, uprising, or insurrection is a refusal of obedience or order. It refers to the open resistance against the orders of an established authority.

A rebellion originates from a sentiment of indignation and disapproval of a situation and ...

of Wat Tyler

Wat Tyler (c. 1320/4 January 1341 – 15 June 1381) was a leader of the 1381 Peasants' Revolt in England. He led a group of rebels from Canterbury to London to oppose the institution of a poll tax and to demand economic and social reforms. Wh ...

and John Ball in the 14th century CE. After the French Revolution

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in November 1799. Many of its ideas are conside ...

, activists and theorists such as François-Noël Babeuf

François-Noël Babeuf (; 23 November 1760 – 27 May 1797), also known as Gracchus Babeuf, was a French proto-communist, revolutionary, and journalist of the French Revolutionary period. His newspaper ''Le tribun du peuple'' (''The Tribune o ...

, Étienne-Gabriel Morelly, Philippe Buonarroti and Auguste Blanqui

Louis Auguste Blanqui (; 8 February 1805 – 1 January 1881) was a French socialist and political activist, notable for his revolutionary theory of Blanquism.

Biography Early life, political activity and first imprisonment (1805–1848)

...

influenced the early French labour and socialist movements.Thomas Kurian (ed). ''The Encyclopedia of Political Science'' CQ Press. Washington D.c. 2011. p. 1555 In Britain, Thomas Paine

Thomas Paine (born Thomas Pain; – In the contemporary record as noted by Conway, Paine's birth date is given as January 29, 1736–37. Common practice was to use a dash or a slash to separate the old-style year from the new-style year. In th ...

proposed a detailed plan to tax property owners to pay for the needs of the poor in '' Agrarian Justice'' while Charles Hall wrote ''The Effects of Civilization on the People in European States'', denouncing capitalism's effects on the poor of his time. This work influenced the utopian schemes of Thomas Spence.

The first self-conscious socialist movements developed in the 1820s and 1830s. Groups such as the Fourierists

Fourierism () is the systematic set of economic, political, and social beliefs first espoused by French intellectual Charles Fourier (1772–1837). Based upon a belief in the inevitability of communal associations of people who worked and lived to ...

, Owenites and Saint-Simonians

Claude Henri de Rouvroy, comte de Saint-Simon (17 October 1760 – 19 May 1825), often referred to as Henri de Saint-Simon (), was a French political, economic and socialist theorist and businessman whose thought had a substantial influence on p ...

provided a series of analyses and interpretations of society. Especially the Owenites overlapped with other working-class movements such as the Chartists

Chartism was a working-class movement for political reform in the United Kingdom that erupted from 1838 to 1857 and was strongest in 1839, 1842 and 1848. It took its name from the People's Charter of 1838 and was a national protest movement, w ...

in the United Kingdom. The Chartists gathered significant numbers around the People's Charter of 1838

Chartism was a working-class movement for political reform in the United Kingdom that erupted from 1838 to 1857 and was strongest in 1839, 1842 and 1848. It took its name from the People's Charter of 1838 and was a national protest movement, w ...

which sought democratic reforms focused on the extension of suffrage to all male adults. Leaders in the movement called for a more equitable distribution of income and better living conditions for the working classes. The first trade unions and consumer cooperative

A consumers' co-operative is an enterprise owned by consumers and managed democratically and that aims at fulfilling the needs and aspirations of its members. Such co-operatives operate within the market system, independently of the state, as a ...

societies followed the Chartist movement. Pierre-Joseph Proudhon

Pierre-Joseph Proudhon (, , ; 15 January 1809, Besançon – 19 January 1865, Paris) was a French socialist,Landauer, Carl; Landauer, Hilde Stein; Valkenier, Elizabeth Kridl (1979) 959 "The Three Anticapitalistic Movements". ''European So ...

proposed his philosophy of mutualism in which "everyone had an equal claim, either alone or as part of a small cooperative, to possess and use land and other resources as needed to make a living". Other currents inspired Christian socialism

Christian socialism is a religious and political philosophy that blends Christianity and socialism, endorsing left-wing politics and socialist economics on the basis of the Bible and the teachings of Jesus. Many Christian socialists believe cap ...

"often in Britain and then usually coming out of left liberal politics and a romantic anti-industrialism" which produced theorists such as Edward Bellamy

Edward Bellamy (March 26, 1850 – May 22, 1898) was an American author, journalist, and political activist most famous for his utopian novel ''Looking Backward''. Bellamy's vision of a harmonious future world inspired the formation of numerou ...

, Charles Kingsley

Charles Kingsley (12 June 1819 – 23 January 1875) was a broad church priest of the Church of England, a university professor, social reformer, historian, novelist and poet. He is particularly associated with Christian socialism, the workin ...

and Frederick Denison Maurice

John Frederick Denison Maurice (29 August 1805 – 1 April 1872), known as F. D. Maurice, was an English Anglican theologian, a prolific author, and one of the founders of Christian socialism. Since World War II, interest in Maurice has ex ...

.

The first advocates of socialism favoured social levelling in order to create a meritocratic

Meritocracy (''merit'', from Latin , and ''-cracy'', from Ancient Greek 'strength, power') is the notion of a political system in which economic goods and/or political power are vested in individual people based on talent, effort, and achiev ...

or technocratic society based on individual talent. Henri de Saint-Simon

Claude Henri de Rouvroy, comte de Saint-Simon (17 October 1760 – 19 May 1825), often referred to as Henri de Saint-Simon (), was a French political, economic and socialist theorist and businessman whose thought had a substantial influence on p ...

was fascinated by the potential of science and technology and advocated a socialist society that would eliminate the disorderly aspects of capitalism based on equal opportunities. He sought a society in which each person was ranked according to his or her capacities and rewarded according to his or her work. His key focus was on administrative efficiency and industrialism and a belief that science was essential to progress. This was accompanied by a desire for a rationally organised economy based on planning and geared towards large-scale scientific and material progress.

West European social critics, including Louis Blanc

Louis Jean Joseph Charles Blanc (; ; 29 October 1811 – 6 December 1882) was a French politician and historian. A Socialism, socialist who favored reforms, he called for the creation of cooperatives in order to job guarantee, guarantee employment ...

, Charles Fourier

François Marie Charles Fourier (;; 7 April 1772 – 10 October 1837) was a French philosopher, an influential early socialist thinker and one of the founders of utopian socialism. Some of Fourier's social and moral views, held to be radical i ...

, Charles Hall, Robert Owen

Robert Owen (; 14 May 1771 – 17 November 1858) was a Welsh textile manufacturer, philanthropist and social reformer, and a founder of utopian socialism and the cooperative movement. He strove to improve factory working conditions, promoted e ...

, Pierre-Joseph Proudhon and Saint-Simon were the first modern socialists who criticised the poverty and inequality of the Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution was the transition to new manufacturing processes in Great Britain, continental Europe, and the United States, that occurred during the period from around 1760 to about 1820–1840. This transition included going f ...

. They advocated reform, Owen advocating the transformation of society to small communities without private property. Owen's contribution to modern socialism was his claim that individual actions and characteristics were largely determined by their social environment. On the other hand, Fourier advocated Phalanstères (communities that respected individual desires, including sexual preference

Sexual orientation is an enduring pattern of romantic or sexual attraction (or a combination of these) to persons of the opposite sex or gender, the same sex or gender, or to both sexes or more than one gender. These attractions are generally su ...

s), affinities and creativity and saw that work has to be made enjoyable for people. Owen and Fourier's ideas were practiced in intentional communities around Europe and North America in the mid-19th century.

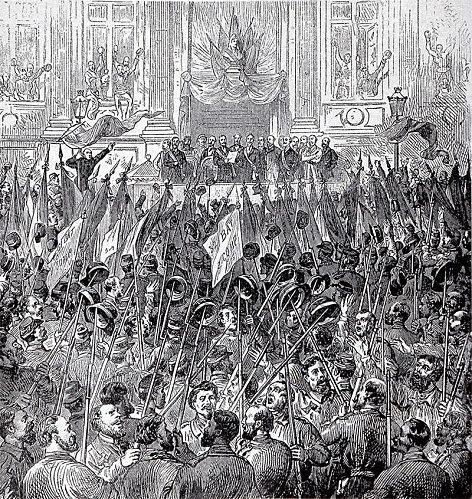

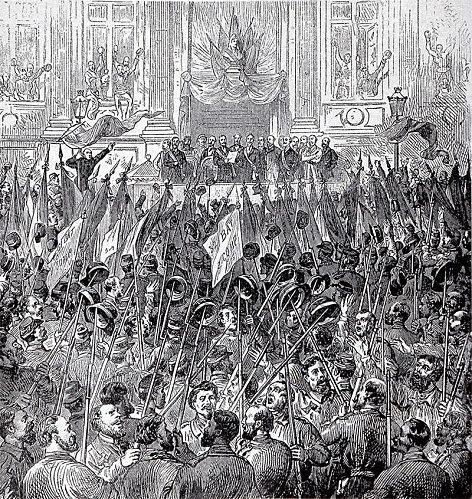

Paris Commune

The Paris Commune was a government that ruled Paris from 18 March (formally, from 28 March) to 28 May 1871. The Commune was the result of an uprising in Paris after France was defeated in the Franco-Prussian War. The Commune elections were held on 26 March. They elected a Commune council of 92 members, one member for each 20,000 residents.

Because the Commune was able to meet on fewer than 60 days in total, only a few decrees were actually implemented. These included the

The Paris Commune was a government that ruled Paris from 18 March (formally, from 28 March) to 28 May 1871. The Commune was the result of an uprising in Paris after France was defeated in the Franco-Prussian War. The Commune elections were held on 26 March. They elected a Commune council of 92 members, one member for each 20,000 residents.

Because the Commune was able to meet on fewer than 60 days in total, only a few decrees were actually implemented. These included the separation of church and state

The separation of church and state is a philosophical and jurisprudential concept for defining political distance in the relationship between religious organizations and the state. Conceptually, the term refers to the creation of a secular sta ...

; the remission of rents owed for the period of the siege (during which payment had been suspended); the abolition of night work in the hundreds of Paris bakeries; the granting of pensions to the unmarried companions and children of National Guards killed on active service; and the free return of all workmen's tools and household items valued up to 20 francs that had been pledged during the siege.

First International

In 1864, the First International was founded in London. It united diverse revolutionary currents, including socialists such as the French followers of Proudhon, Blanquists, Philadelphes, English

In 1864, the First International was founded in London. It united diverse revolutionary currents, including socialists such as the French followers of Proudhon, Blanquists, Philadelphes, English trade union

A trade union (labor union in American English), often simply referred to as a union, is an organization of workers intent on "maintaining or improving the conditions of their employment", ch. I such as attaining better wages and benefits (s ...

ists and social democrats

Social democracy is a political, social, and economic philosophy within socialism that supports political and economic democracy. As a policy regime, it is described by academics as advocating economic and social interventions to promote s ...

. In 1865 and 1866, it held a preliminary conference and had its first congress in Geneva

Geneva ( ; french: Genève ) frp, Genèva ; german: link=no, Genf ; it, Ginevra ; rm, Genevra is the second-most populous city in Switzerland (after Zürich) and the most populous city of Romandy, the French-speaking part of Switzerland. Situ ...

, respectively. Due to their wide variety of philosophies, conflict immediately erupted. The first objections to Marx came from the mutualists who opposed state socialism

State socialism is a political and economic ideology within the socialist movement that advocates state ownership of the means of production. This is intended either as a temporary measure, or as a characteristic of socialism in the transition ...

. Shortly after Mikhail Bakunin

Mikhail Alexandrovich Bakunin (; 1814–1876) was a Russian revolutionary anarchist, socialist and founder of collectivist anarchism. He is considered among the most influential figures of anarchism and a major founder of the revolutionary ...

and his followers joined in 1868, the First International became polarised into camps headed by Marx and Bakunin. The clearest differences between the groups emerged over their proposed strategies for achieving their visions. The First International became the first major international forum for the promulgation of socialist ideas.

Bakunin's followers were called collectivists and sought to collectivise ownership of the means of production while retaining payment proportional to the amount and kind of labour of each individual. Like Proudhonists, they asserted the right of each individual to the product of his labour and to be remunerated for his particular contribution to production. By contrast, anarcho-communists

Anarcho-communism, also known as anarchist communism, (or, colloquially, ''ancom'' or ''ancomm'') is a political philosophy and anarchist school of thought that advocates communism. It calls for the abolition of private property but retains re ...

sought collective ownership of both the means and the products of labour. As Errico Malatesta

Errico Malatesta (4 December 1853 – 22 July 1932) was an Italian anarchist propagandist and revolutionary socialist. He edited several radical newspapers and spent much of his life exiled and imprisoned, having been jailed and expelled fro ...

put it, "instead of running the risk of making a confusion in trying to distinguish what you and I each do, let us all work and put everything in common. In this way each will give to society all that his strength permits until enough is produced for every one; and each will take all that he needs, limiting his needs only in those things of which there is not yet plenty for every one". Anarcho-communism as a coherent economic-political philosophy was first formulated in the Italian section of the First International by Malatesta, Carlo Cafiero, Emilio Covelli, Andrea Costa

Andrea is a given name which is common worldwide for both males and females, cognate to Andreas, Andrej and Andrew.

Origin of the name

The name derives from the Greek word ἀνήρ (''anēr''), genitive ἀνδρός (''andrós''), that r ...

and other ex-Mazzinian

Giuseppe Mazzini (, , ; 22 June 1805 – 10 March 1872) was an Italian politician, journalist, and activist for the unification of Italy (Risorgimento) and spearhead of the Italian revolutionary movement. His efforts helped bring about the i ...

republicans.Nunzio Pernicone, "Italian Anarchism 1864–1892", pp. 111–113, AK Press 2009. Out of respect for Bakunin, they did not make their differences with collectivist anarchism explicit until after his death.James Guillaume"Michael Bakunin – A Biographical Sketch"

/ref>

Syndicalism

Syndicalism is a Revolutionary politics, revolutionary current within the Left-wing politics, left-wing of the Labour movement, labor movement that seeks to unionize workers Industrial unionism, according to industry and advance their demands t ...

emerged in France inspired in part by Proudhon and later by Pelloutier and Georges Sorel

Georges Eugène Sorel (; ; 2 November 1847 – 29 August 1922) was a French social thinker, political theorist, historian, and later journalist. He has inspired theories and movements grouped under the name of Sorelianism. His social and p ...

."Socialism"at ''

Encyclopedia Britannica

An encyclopedia (American English) or encyclopædia (British English) is a reference work or compendium providing summaries of knowledge either general or special to a particular field or discipline. Encyclopedias are divided into articles ...

''. It developed at the end of the 19th century out of the French trade-union movement (''syndicat'' is the French word for trade union). It was a significant force in Italy and Spain in the early 20th century until it was crushed by the fascist

Fascism is a far-right, authoritarian, ultra-nationalist political ideology and movement,: "extreme militaristic nationalism, contempt for electoral democracy and political and cultural liberalism, a belief in natural social hierarchy and the ...

regimes in those countries. In the United States, syndicalism appeared in the guise of the Industrial Workers of the World

The Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), members of which are commonly termed "Wobblies", is an international labor union that was founded in Chicago in 1905. The origin of the nickname "Wobblies" is uncertain. IWW ideology combines gener ...

, or "Wobblies", founded in 1905. Syndicalism is an economic system that organises industries into confederations (syndicates) and the economy is managed by negotiation between specialists and worker representatives of each field, comprising multiple non-competitive categorised units. Syndicalism is a form of communism and economic corporatism

Corporatism is a collectivist political ideology which advocates the organization of society by corporate groups, such as agricultural, labour, military, business, scientific, or guild associations, on the basis of their common interests. Th ...

, but also refers to the political movement and tactics used to bring about this type of system. An influential anarchist movement based on syndicalist ideas is anarcho-syndicalism

Anarcho-syndicalism is a political philosophy and anarchist school of thought that views revolutionary industrial unionism or syndicalism as a method for workers in capitalist society to gain control of an economy and thus control influence i ...

. The International Workers Association is an international anarcho-syndicalist federation of various labour unions.

The Fabian Society

The Fabian Society is a British socialist organisation whose purpose is to advance the principles of social democracy and democratic socialism via gradualist and reformist effort in democracies, rather than by revolutionary overthrow. The F ...

is a British socialist organisation established to advance socialism via gradualist and reformist

Reformism is a political doctrine advocating the reform of an existing system or institution instead of its abolition and replacement.

Within the socialist movement, reformism is the view that gradual changes through existing institutions can ...

means. The society laid many foundations of the Labour Party and subsequently affected the policies of states emerging from the decolonisation

Decolonization or decolonisation is the undoing of colonialism, the latter being the process whereby imperial nations establish and dominate foreign territories, often overseas. Some scholars of decolonization focus especially on independence m ...

of the British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading post ...

, most notably India and Singapore. Originally, the Fabian Society was committed to the establishment of a socialist economy

Socialist economics comprises the economic theories, practices and norms of hypothetical and existing socialist economic systems. A socialist economic system is characterized by social ownership and operation of the means of production that may ...

, alongside a commitment to British imperialism

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts est ...

as a progressive and modernising force.''Discovering Imperialism: Social Democracy to World War I'', 25 November 2011. (p. 249): "the pro-imperialist majority, led by Sidney Webb and George Bernard Shaw, advanced an intellectual justification for central control by the British Empire, arguing that existing institutions should simply work more 'efficiently'." Later, the society functioned primarily as a think tank

A think tank, or policy institute, is a research institute that performs research and advocacy concerning topics such as social policy, political strategy, economics, military, technology, and culture. Most think tanks are non-governmental ...

and is one of fifteen socialist societies affiliated with the Labour Party. Similar societies exist in Australia (the Australian Fabian Society), in Canada (the Douglas-Coldwell Foundation and the now disbanded League for Social Reconstruction

The League for Social Reconstruction (LSR) was a circle of Canadian socialists officially formed in 1932. The group advocated for social and economic reformation as well as political education. The formation of the LSR was provoked by events such ...

) and in New Zealand.

Guild socialism is a political movement advocating workers' control

Workers' control is participation in the management of factories and other commercial enterprises by the people who work there. It has been variously advocated by anarchists, socialists, communists, social democrats, distributists and Christia ...

of industry through the medium of trade-related guild

A guild ( ) is an association of artisans and merchants who oversee the practice of their craft/trade in a particular area. The earliest types of guild formed as organizations of tradesmen belonging to a professional association. They sometimes ...

s "in an implied contractual relationship with the public". It originated in the United Kingdom and was at its most influential in the first quarter of the 20th century. Inspired by medieval guilds, theorists such as Samuel George Hobson

Samuel George Hobson, often known as S. G. Hobson (4 February 1870 – 4 January 1940), was a theorist of guild socialism.

Born in Bessbrook, County Armagh, Hobson was given a Quaker education in Saffron Walden and then Sidcot, Somerset. Movi ...

and G. D. H. Cole advocated the public ownership of industries and their workforces' organisation into guilds, each of which under the democratic control of its trade union. Guild socialists were less inclined than Fabians to invest power in a state. At some point, like the American Knights of Labor

Knights of Labor (K of L), officially Noble and Holy Order of the Knights of Labor, was an American labor federation active in the late 19th century, especially the 1880s. It operated in the United States as well in Canada, and had chapters also ...

, guild socialism wanted to abolish the wage system.

Second International

As the ideas of Marx and Engels gained acceptance, particularly in central Europe, socialists sought to unite in an international organisation. In 1889 (the centennial of the French Revolution), the Second International was founded, with 384 delegates from twenty countries representing about 300 labour and socialist organisations. Engels was elected honorary president at the third congress in 1893. Anarchists were banned, mainly due to pressure from Marxists. It has been argued that at some point the Second International turned "into a battleground over the issue oflibertarian

Libertarianism (from french: libertaire, "libertarian"; from la, libertas, "freedom") is a political philosophy that upholds liberty as a core value. Libertarians seek to maximize autonomy and political freedom, and minimize the state's e ...

versus authoritarian socialism. Not only did they effectively present themselves as champions of minority rights; they also provoked the German Marxists into demonstrating a dictatorial intolerance which was a factor in preventing the British labour movement from following the Marxist direction indicated by such leaders as H. M. Hyndman".

Reformism arose as an alternative to revolution. Eduard Bernstein

Eduard Bernstein (; 6 January 1850 – 18 December 1932) was a German Social democracy, social democratic Marxist theorist and politician. A member of the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD), Bernstein had held close association to Karl ...

was a leading social democrat

Social democracy is a political, social, and economic philosophy within socialism that supports political and economic democracy. As a policy regime, it is described by academics as advocating economic and social interventions to promote soc ...

in Germany who proposed the concept of evolutionary socialism. Revolutionary socialists quickly targeted reformism: Rosa Luxemburg

Rosa Luxemburg (; ; pl, Róża Luksemburg or ; 5 March 1871 – 15 January 1919) was a Polish and naturalised-German revolutionary socialism, revolutionary socialist, Marxism, Marxist philosopher and anti-war movement, anti-war activist. Succ ...

condemned Bernstein's '' Evolutionary Socialism'' in her 1900 essay ''Social Reform or Revolution

''Social Reform or Revolution?'' (german: Sozialreform oder Revolution?) is an 1899 pamphlet by Polish-German Marxist theorist Rosa Luxemburg. Luxemburg argues that trade unions, reformist political parties and the expansion of social democracy� ...

?'' Revolutionary socialism

Revolutionary socialism is a political philosophy, doctrine, and tradition within socialism that stresses the idea that a social revolution is necessary to bring about structural changes in society. More specifically, it is the view that revolut ...

encompasses multiple social and political movements that may define "revolution" differently. The Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD) became the largest and most powerful socialist party in Europe, despite working illegally until the anti-socialist laws were dropped in 1890. In the 1893 elections, it gained 1,787,000 votes, a quarter of the total votes cast, according to Engels. In 1895, the year of his death, Engels emphasised ''The Communist Manifesto

''The Communist Manifesto'', originally the ''Manifesto of the Communist Party'' (german: Manifest der Kommunistischen Partei), is a political pamphlet written by German philosophers Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. Commissioned by the Comm ...

'' emphasis on winning, as a first step, the "battle of democracy".

In South America, the Socialist Party of Argentina

The Socialist Party ( es, Partido Socialista, PS) is a centre-left political party in Argentina. Founded in 1896, it is one of the oldest still-active parties in Argentina, alongside the Radical Civic Union.

The party has been an opponent o ...

was established in the 1890s led by Juan B. Justo

Juan Bautista Justo (June 28, 1865, in Buenos Aires – January 8, 1928, in Buenos Aires) was an Argentine physician, journalist, politician, and writer. After finishing medical school he joined the Civic Union of the Youth, later participating i ...

and Nicolás Repetto

Nicolás Repetto (21 October 1871 – 29 November 1965) was an Argentine physician and leader of the Socialist Party of Argentina.

Biography

Nicolás Repetto was born in Buenos Aires in 1871 and enrolled at the prestigious Colegio Nacional de Bu ...

, among others. It was the first mass party

A political party is an organization that coordinates candidates to compete in a particular country's elections. It is common for the members of a party to hold similar ideas about politics, and parties may promote specific political ideology ...

in the country and in Latin America. The party affiliated itself with the Second International.

Early 20th century

For four months in 1904,Australian Labor Party

The Australian Labor Party (ALP), also simply known as Labor, is the major centre-left political party in Australia, one of two major parties in Australian politics, along with the centre-right Liberal Party of Australia. The party forms ...

leader Chris Watson

John Christian Watson (born Johan Cristian Tanck; 9 April 186718 November 1941) was an Australian politician who served as the third prime minister of Australia, in office from 27 April to 18 August 1904. He served as the inaugural federal lea ...

was the Prime Minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister is ...

of the country. Watson thus became the head of the world's first socialist or social democratic parliamentary government. Australian historian Geoffrey Blainey

Geoffrey Norman Blainey (born 11 March 1930) is an Australian historian, academic, best selling author and commentator. He is noted for having written authoritative texts on the economic and social history of Australia, including '' The Tyranny ...

argues that the Labor Party was not socialist at all in the 1890s, and that socialist and collectivist elements only made their way in the party's platform in the early 20th century.

In 1909, the first Kibbutz

A kibbutz ( he, קִבּוּץ / , lit. "gathering, clustering"; plural: kibbutzim / ) is an intentional community in Israel that was traditionally based on agriculture. The first kibbutz, established in 1909, was Degania. Today, farming h ...

was established in Palestine by Russian Jewish Immigrants. The Kibbutz Movement

The Kibbutz Movement ( he, התנועה הקיבוצית, ''HaTnu'a HaKibbutzit'') is the largest settlement movement for kibbutzim in Israel. It was formed in 1999 by a partial merger of the United Kibbutz Movement and Kibbutz Artzi and is made ...

expanded through the 20th century following a doctrine of Zionist

Zionism ( he, צִיּוֹנוּת ''Tsiyyonut'' after '' Zion'') is a nationalist movement that espouses the establishment of, and support for a homeland for the Jewish people centered in the area roughly corresponding to what is known in J ...

socialism. The British Labour Party first won seats in the House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of parliament. ...

in 1902.

By 1917, the patriotism of

By 1917, the patriotism of World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

changed into political radicalism

Radical politics denotes the intent to transform or replace the principles of a society or political system, often through social change, structural change, revolution or radical reform. The process of adopting radical views is termed radica ...

in Australia, most of Europe and the United States. Other socialist parties from around the world who were beginning to gain importance in their national politics in the early 20th century included the Italian Socialist Party

The Italian Socialist Party (, PSI) was a socialist and later social-democratic political party in Italy, whose history stretched for longer than a century, making it one of the longest-living parties of the country.

Founded in Genoa in 1892 ...

, the French Section of the Workers' International

The French Section of the Workers' International (french: Section française de l'Internationale ouvrière, SFIO) was a political party in France that was founded in 1905 and succeeded in 1969 by the modern-day Socialist Party. The SFIO was fou ...

, the Spanish Socialist Workers' Party

The Spanish Socialist Workers' Party ( es, Partido Socialista Obrero Español ; PSOE ) is a social-democraticThe PSOE is described as a social-democratic party by numerous sources:

*

*

*

* political party in Spain. The PSOE has been in go ...

, the Swedish Social Democratic Party, the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party

The Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP; in , ''Rossiyskaya sotsial-demokraticheskaya rabochaya partiya (RSDRP)''), also known as the Russian Social Democratic Workers' Party or the Russian Social Democratic Party, was a socialist po ...

and the Socialist Party

Socialist Party is the name of many different political parties around the world. All of these parties claim to uphold some form of socialism, though they may have very different interpretations of what "socialism" means. Statistically, most of t ...

in Argentina, the Socialist Workers' Party in Chile and the Socialist Party of America

The Socialist Party of America (SPA) was a socialist political party in the United States formed in 1901 by a merger between the three-year-old Social Democratic Party of America and disaffected elements of the Socialist Labor Party of Ameri ...

in the United States.

Russian Revolution

In February 1917, a revolution occurred in Russia. Workers, soldiers and peasants establishedsoviets

Soviet people ( rus, сове́тский наро́д, r=sovyétsky naród), or citizens of the USSR ( rus, гра́ждане СССР, grázhdanye SSSR), was an umbrella demonym for the population of the Soviet Union.

Nationality policy in th ...

(councils), the monarchy fell and a provisional government

A provisional government, also called an interim government, an emergency government, or a transitional government, is an emergency governmental authority set up to manage a political transition generally in the cases of a newly formed state or f ...

convened pending the election of a constituent assembly

A constituent assembly (also known as a constitutional convention, constitutional congress, or constitutional assembly) is a body assembled for the purpose of drafting or revising a constitution. Members of a constituent assembly may be elected ...

. In April of that year, Vladimir Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov. ( 1870 – 21 January 1924), better known as Vladimir Lenin,. was a Russian revolutionary, politician, and political theorist. He served as the first and founding head of government of Soviet Russia from 1917 to 1 ...

, leader of the Bolshevik

The Bolsheviks (russian: Большевики́, from большинство́ ''bol'shinstvó'', 'majority'),; derived from ''bol'shinstvó'' (большинство́), "majority", literally meaning "one of the majority". also known in English ...

faction of socialists in Russia and known for his profound and controversial expansions of Marxism

Marxism is a left-wing to far-left method of socioeconomic analysis that uses a materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to understand class relations and social conflict and a dialec ...

, was allowed to cross Germany to return from exile in Switzerland.

Lenin had published essays

An essay is, generally, a piece of writing that gives the author's own argument, but the definition is vague, overlapping with those of a letter, a paper, an article, a pamphlet, and a short story. Essays have been sub-classified as forma ...

on his analysis of imperialism

Imperialism is the state policy, practice, or advocacy of extending power and dominion, especially by direct territorial acquisition or by gaining political and economic control of other areas, often through employing hard power ( economic and ...

, the monopoly and globalisation phase of capitalism, as well as analyses on social conditions. He observed that as capitalism had further developed in Europe and America, the workers remained unable to gain class consciousness

In Marxism, class consciousness is the set of beliefs that a person holds regarding their social class or economic rank in society, the structure of their class, and their class interests. According to Karl Marx, it is an awareness that is key to ...

so long as they were too busy working to pay their expenses. He therefore proposed that the social revolution would require the leadership of a vanguard party

Vanguardism in the context of Leninist revolutionary struggle, relates to a strategy whereby the most class-conscious and politically "advanced" sections of the proletariat or working class, described as the revolutionary vanguard, form or ...

of class-conscious revolutionaries from the educated and politically active part of the population.

Upon arriving in Petrograd

Saint Petersburg ( rus, links=no, Санкт-Петербург, a=Ru-Sankt Peterburg Leningrad Petrograd Piter.ogg, r=Sankt-Peterburg, p=ˈsankt pʲɪtʲɪrˈburk), formerly known as Petrograd (1914–1924) and later Leningrad (1924–1991), i ...

, Lenin declared that the revolution in Russia had only begun, and that the next step was for the workers' soviet

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...

s to take full authority. He issued a thesis

A thesis ( : theses), or dissertation (abbreviated diss.), is a document submitted in support of candidature for an academic degree or professional qualification presenting the author's research and findings.International Standard ISO 7144 ...

outlining the Bolshevik programme, including rejection of any legitimacy in the provisional government and advocacy for state power to be administered through the soviets. The Bolsheviks became the most influential force. On 7 November, the capitol of the provisional government was stormed by Bolshevik Red Guards in what later was officially known in the Soviet Union as the Great October Socialist Revolution. The provisional government ended and the Russian Socialist Federative Soviet Republic

The Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic, Russian SFSR or RSFSR ( rus, Российская Советская Федеративная Социалистическая Республика, Rossíyskaya Sovétskaya Federatívnaya Soci ...

—the world's first constitutionally socialist state—was established. On 25 January 1918, Lenin declared "Long live the world socialist revolution!" at the Petrograd Soviet

The Petrograd Soviet of Workers' and Soldiers' Deputies (russian: Петроградский совет рабочих и солдатских депутатов, ''Petrogradskiy soviet rabochikh i soldatskikh deputatov'') was a city council of P ...

and proposed an immediate armistice on all fronts and transferred the land of the landed proprietors, the crown and the monasteries to the peasant committees without compensation.

The day after assuming executive power on 25 January, Lenin wrote ''Draft Regulations on Workers' Control'', which granted workers control of businesses with more than five workers and office employees and access to all books, documents and stocks and whose decisions were to be "binding upon the owners of the enterprises". Governing through the elected soviets and in alliance with the peasant-based Left Socialist-Revolutionaries

The Party of Left Socialist-Revolutionaries (russian: Партия левых социалистов-революционеров-интернационалистов) was a revolutionary socialist political party formed during the Russian Revo ...

, the Bolshevik government began nationalising banks and industry; and disavowed the national debts of the deposed Romanov

The House of Romanov (also transcribed Romanoff; rus, �