Smallpox Epidemics In The Americas on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The history of smallpox extends into pre-history. Genetic evidence suggests that the smallpox virus emerged 3,000 to 4,000 years ago. Prior to that, similar ancestral viruses circulated, but possibly only in other mammals, and possibly with different symptoms. Only a few written reports dating from about 500–1000 CE are considered reliable historical descriptions of smallpox, so understanding of the disease prior to that has relied on genetics and archaeology. However, during the second millennium, especially starting in the 16th century, reliable written reports become more common. The earliest physical evidence of smallpox is found in the Egyptian mummies of people who died some 3,000 years ago. Smallpox has had a major impact on world history, not least because indigenous populations of regions where smallpox was non-native, such as

One of the oldest records of what may have been an encounter with smallpox in Africa is associated with the elephant war circa AD 568 CE, when after fighting a siege in Mecca, Ethiopian troops contracted the disease which they carried with them back to Africa.

Arab ports in Coastal towns in Africa likely contributed to the importation of smallpox into Africa, as early as the 13th century, though no records exist until the 16th century. Upon invasion of these towns by tribes in the interior of Africa, a severe epidemic affected all African inhabitants while sparing the Portuguese. Densely populated areas of Africa connected to the Mediterranean, Nubia and Ethiopia by caravan route likely were affected by smallpox since the 11th century, though written records do not appear until the introduction of the slave trade in the 16th century.

The

One of the oldest records of what may have been an encounter with smallpox in Africa is associated with the elephant war circa AD 568 CE, when after fighting a siege in Mecca, Ethiopian troops contracted the disease which they carried with them back to Africa.

Arab ports in Coastal towns in Africa likely contributed to the importation of smallpox into Africa, as early as the 13th century, though no records exist until the 16th century. Upon invasion of these towns by tribes in the interior of Africa, a severe epidemic affected all African inhabitants while sparing the Portuguese. Densely populated areas of Africa connected to the Mediterranean, Nubia and Ethiopia by caravan route likely were affected by smallpox since the 11th century, though written records do not appear until the introduction of the slave trade in the 16th century.

The

Historia de Chile desde su descubrimiento hasta el año 1575

. Cervantesvirtual.com. Retrieved on 2011-12-06. In 1633 in

Smallpox epidemic ravages Native Americans on the northwest coast of North America in the 1770s

. Historyink.com. Retrieved on 2011-12-06. The smallpox epidemic of 1780–1782 brought devastation and drastic depopulation among the Those who were infected with the disease were detained in quarantine facilities in the hopes of protecting others from getting sick. These quarantine facilities, or pesthouses, were mostly located on Southampton Street. As the outbreak worsened, men were also moved to hospitals on Gallop's Island. Women and children were primarily sent to Southampton Street. Smallpox patients were not allowed in regular hospital facilities throughout the city, for fear the sickness would spread among the already sick.

A reflection of the previous outbreak that occurred in New York, the poor and homeless were blamed for the sickness's spread. In response to this belief, the city instructed teams of physicians to vaccinate anyone living in inexpensive housing.

In an effort to control the outbreak, the Boston Board of Health began voluntary vaccination programs. Individuals could receive free vaccines at their

workplaces or at different stations set up throughout the city. By the end of 1901, some 40,000 of the city's residents had received a smallpox vaccine. However, despite the city's efforts, the epidemic continued to grow. In January 1902, a door-to-door vaccination program was initiated. Health officials were instructed to compel individuals to receive vaccination, pay a $5 fine, or face 15 days in prison. This door-to-door program was met by some resistance as some individuals feared the vaccines to be unsafe and ineffective. Others felt compulsory vaccination in itself was a problem that violated an individual's civil liberties.

This program of compulsory vaccination eventually led to the famous '' Jacobson v. Massachusetts'' case. The case was the result of a

Those who were infected with the disease were detained in quarantine facilities in the hopes of protecting others from getting sick. These quarantine facilities, or pesthouses, were mostly located on Southampton Street. As the outbreak worsened, men were also moved to hospitals on Gallop's Island. Women and children were primarily sent to Southampton Street. Smallpox patients were not allowed in regular hospital facilities throughout the city, for fear the sickness would spread among the already sick.

A reflection of the previous outbreak that occurred in New York, the poor and homeless were blamed for the sickness's spread. In response to this belief, the city instructed teams of physicians to vaccinate anyone living in inexpensive housing.

In an effort to control the outbreak, the Boston Board of Health began voluntary vaccination programs. Individuals could receive free vaccines at their

workplaces or at different stations set up throughout the city. By the end of 1901, some 40,000 of the city's residents had received a smallpox vaccine. However, despite the city's efforts, the epidemic continued to grow. In January 1902, a door-to-door vaccination program was initiated. Health officials were instructed to compel individuals to receive vaccination, pay a $5 fine, or face 15 days in prison. This door-to-door program was met by some resistance as some individuals feared the vaccines to be unsafe and ineffective. Others felt compulsory vaccination in itself was a problem that violated an individual's civil liberties.

This program of compulsory vaccination eventually led to the famous '' Jacobson v. Massachusetts'' case. The case was the result of a

In 1713, Lady Mary Wortley Montagu's brother died of smallpox; she too contracted the virus two years later at the age of twenty-six, leaving her badly scarred. When her husband was made ambassador to

In 1713, Lady Mary Wortley Montagu's brother died of smallpox; she too contracted the virus two years later at the age of twenty-six, leaving her badly scarred. When her husband was made ambassador to

online

* Hopkins, Donald R. ''The Greatest Killer: Smallpox in History'' (U of Chicago Press, 2002) * Patterson, Kristine B. and Thomas Runge, "Smallpox and the native American." ''American journal of the medical sciences'' 323.4 (2002): 216–22

online

* Thèves, Catherine, Eric Crubézy, and Philippe Biagini. "History of smallpox and its spread in human populations." ''Paleomicrobiology of Humans'' (2016): 161–72

online

*

Inoculation for the Small-Pox defended

750 article from ''

"Why Blame Smallpox?: The Death of the Inca Huayna Capac and the Demographic Destruction of Tawantinsuyu (Ancient Peru)"

Revisionist argument regarding smallpox in 16th-century Peru

History of Smallpox in South Asia

{{DEFAULTSORT:History Of Smallpox

the Americas

The Americas, sometimes collectively called America, are a landmass comprising the totality of North America and South America.'' Webster's New World College Dictionary'', 2010 by Wiley Publishing, Inc., Cleveland, Ohio. When viewed as a sin ...

and Australia, were rapidly and greatly reduced by smallpox (along with other introduced diseases) during periods of initial foreign contact, which helped pave the way for conquest and colonization. During the 18th century, the disease killed an estimated 400,000 Europeans each year, including five reigning monarch

A monarch () is a head of stateWebster's II New College Dictionary. "Monarch". Houghton Mifflin. Boston. 2001. p. 707. Life tenure, for life or until abdication, and therefore the head of state of a monarchy. A monarch may exercise the highest ...

s, and was responsible for a third of all blindness. Between 20 and 60% of all those infected—and over 80% of infected children—died from the disease.

During the 20th century, it is estimated that smallpox was responsible for 250–500 million deaths. In the early 1950s, an estimated 50 million cases of smallpox occurred in the world each year. As recently as 1967, the World Health Organization

The World Health Organization (WHO) is a list of specialized agencies of the United Nations, specialized agency of the United Nations which coordinates responses to international public health issues and emergencies. It is headquartered in Gen ...

estimated that 15 million people contracted the disease and that two million died in that year. After successful vaccination

Vaccination is the administration of a vaccine to help the immune system develop immunity from a disease. Vaccines contain a microorganism or virus in a weakened, live or killed state, or proteins or toxins from the organism. In stimulating ...

campaigns throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, the WHO certified the global eradication of smallpox in May 1980. Smallpox is one of two infectious disease

An infection is the invasion of tissue (biology), tissues by pathogens, their multiplication, and the reaction of host (biology), host tissues to the infectious agent and the toxins they produce. An infectious disease, also known as a transmis ...

s to have been eradicated, the other being rinderpest

Rinderpest (also cattle plague or steppe murrain) was an infectious viral disease of cattle, domestic water buffalo, and many other species of even-toed ungulates, including gaurs, African Buffalo, buffaloes, large antelope, deer, giraffes, wilde ...

, which was declared eradicated in 2011.

Eurasian epidemics

It has been suggested that smallpox was a major component of thePlague of Athens

The Plague of Athens (, ) was an epidemic that devastated the city-state of Athens in ancient Greece during the second year (430 BC) of the Peloponnesian War when an Athenian victory still seemed within reach. The plague killed an estimated 75, ...

that occurred in 430 BCE, during the Peloponnesian War

The Second Peloponnesian War (431–404 BC), often called simply the Peloponnesian War (), was an Ancient Greece, ancient Greek war fought between Classical Athens, Athens and Sparta and their respective allies for the hegemony of the Ancien ...

s, and was described by Thucydides

Thucydides ( ; ; BC) was an Classical Athens, Athenian historian and general. His ''History of the Peloponnesian War'' recounts Peloponnesian War, the fifth-century BC war between Sparta and Athens until the year 411 BC. Thucydides has been d ...

.

Galen

Aelius Galenus or Claudius Galenus (; September 129 – AD), often Anglicization, anglicized as Galen () or Galen of Pergamon, was a Ancient Rome, Roman and Greeks, Greek physician, surgeon, and Philosophy, philosopher. Considered to be one o ...

's description of the Antonine Plague, which swept through the Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ruled the Mediterranean and much of Europe, Western Asia and North Africa. The Roman people, Romans conquered most of this during the Roman Republic, Republic, and it was ruled by emperors following Octavian's assumption of ...

in 165–180 CE, indicates that it was probably caused by smallpox. Returning soldiers picked up the disease in Seleucia

Seleucia (; ), also known as or or Seleucia ad Tigrim, was a major Mesopotamian city, located on the west bank of the Tigris River within the present-day Baghdad Governorate in Iraq. It was founded around 305 BC by Seleucus I Nicator as th ...

(in modern Iraq), and brought it home with them to Syria and Italy. It raged for fifteen years and greatly weakened the Roman empire, killing up to one-third of the population in some areas. Total deaths have been estimated at 5 million.

A second major outbreak of disease in the Roman Empire, known as the Plague of Cyprian

The Plague of Cyprian was a pandemic which afflicted the Roman Empire from about AD 249 to 262, or 251/2 to 270. The plague is thought to have caused widespread manpower shortages for food production and the Roman army, severely weakening the em ...

(251–266 CE), was also either smallpox or measles

Measles (probably from Middle Dutch or Middle High German ''masel(e)'', meaning "blemish, blood blister") is a highly contagious, Vaccine-preventable diseases, vaccine-preventable infectious disease caused by Measles morbillivirus, measles v ...

. The Roman empire stopped growing as a consequence on these two plagues, according to historians such as Theodore Mommsen

Christian Matthias Theodor Mommsen (; ; 30 November 1817 – 1 November 1903) was a Germans, German classics, classical scholar, historian, jurist, journalist, politician and archaeologist. He is widely regarded as one of the greatest classicis ...

. Although some historians believe that many historical epidemic

An epidemic (from Greek ἐπί ''epi'' "upon or above" and δῆμος ''demos'' "people") is the rapid spread of disease to a large number of hosts in a given population within a short period of time. For example, in meningococcal infection ...

s and pandemic

A pandemic ( ) is an epidemic of an infectious disease that has a sudden increase in cases and spreads across a large region, for instance multiple continents or worldwide, affecting a substantial number of individuals. Widespread endemic (epi ...

s were early outbreaks of smallpox, contemporary records are not detailed enough to make a definite diagnosis. Originally published as ''Princes and Peasants: Smallpox in History'' (1983), The discovery of smallpox-related osteomyelitis

Osteomyelitis (OM) is the infectious inflammation of bone marrow. Symptoms may include pain in a specific bone with overlying redness, fever, and weakness. The feet, spine, and hips are the most commonly involved bones in adults.

The cause is ...

on a skeleton buried at Corinium

Corinium Dobunnorum was the Romano-British settlement at Cirencester in the present-day English county of Gloucestershire. Its 2nd-century walls enclosed the second-largest area of a city in Roman Britain. It was the tribal capital of the Do ...

in the late 3rd century confirms the presence of the disease in the Roman world around this time, though not its ubiquity.

Written sometime before 400 AD, the Indian medical book ''Sushruta Samhita

The ''Sushruta Samhita'' (, ) is an ancient Sanskrit text on medicine and one of the most important such treatises on this subject to survive from the ancient world. The ''Compendium of Sushruta, Suśruta'' is one of the foundational texts of ...

'' recorded a disease marked by pustule

A skin condition, also known as cutaneous condition, is any medical condition that affects the integumentary system—the organ system that encloses the body and includes skin, nails, and related muscle and glands. The major function of this ...

s and boils, saying "the pustules are red, yellow, and white and they are accompanied by burning pain … the skin seems studded with grains of rice." The Indian epidemic was thought to be punishment from a god, and the survivors created a goddess, Sitala, as the anthropomorphic personification of the disease. Smallpox was thus regarded as possession by Sitala. In Hinduism

Hinduism () is an Hypernymy and hyponymy, umbrella term for a range of Indian religions, Indian List of religions and spiritual traditions#Indian religions, religious and spiritual traditions (Sampradaya, ''sampradaya''s) that are unified ...

the goddess Sitala both causes and cures high fever, rashes, hot flashes and pustules. All of these are symptoms of smallpox.

Most of the details about the epidemics are lost, probably due to the scarcity of surviving written records from the Early Middle Ages

The Early Middle Ages (or early medieval period), sometimes controversially referred to as the Dark Ages (historiography), Dark Ages, is typically regarded by historians as lasting from the late 5th to the 10th century. They marked the start o ...

. The first incontrovertible description of smallpox in Western Europe

Western Europe is the western region of Europe. The region's extent varies depending on context.

The concept of "the West" appeared in Europe in juxtaposition to "the East" and originally applied to the Western half of the ancient Mediterranean ...

occurred in 581 AD, when Bishop Gregory of Tours

Gregory of Tours (born ; 30 November – 17 November 594 AD) was a Gallo-Roman historian and Bishop of Tours during the Merovingian period and is known as the "father of French history". He was a prelate in the Merovingian kingdom, encom ...

provided an eyewitness account describing the characteristic symptoms of smallpox. Waves of epidemics wiped out large rural populations.

In 710 AD, smallpox was re-introduced into Europe via Iberia by the Umayyad conquest of Hispania

The Muslim conquest of the Iberian Peninsula (; 711–720s), also known as the Arab conquest of Spain, was the Umayyad Caliphate, Umayyad conquest of the Visigothic Kingdom, Visigothic Kingdom of Hispania in the early 8th century. The conquest re ...

.

The Japanese smallpox epidemic of 735–737 is believed to have killed as much as one-third of Japan's population.

There is evidence that smallpox reached the Philippines

The Philippines, officially the Republic of the Philippines, is an Archipelagic state, archipelagic country in Southeast Asia. Located in the western Pacific Ocean, it consists of List of islands of the Philippines, 7,641 islands, with a tot ...

from the 4th century onwards possibly from indirect trade with Indians.Victor T. King, 1998, ''Environmental Challenges in South-East Asia'', London/New York, Routledge, pp. 78–79.

During the 18th century, there were many major outbreaks of smallpox, driven possibly by increasing contact with European colonists and traders. There were epidemics, for instance, in the Sultanate of Banjar (South Kalimantan), in 1734, 1750–51, 1764–65 and 1778–79; in the Sultanate of Tidore

The Sultanate of Tidore (Jawi script, Jawi: ; sometimes ) was a sultanate in Southeast Asia, centered on Tidore in the Maluku Islands (presently in North Maluku, Indonesia). It was also known as Duko, its ruler carrying the title Kië ma-kolano ( ...

(Moluccas ) during the 1720s, and in southern Sumatra

Sumatra () is one of the Sunda Islands of western Indonesia. It is the largest island that is fully within Indonesian territory, as well as the list of islands by area, sixth-largest island in the world at 482,286.55 km2 (182,812 mi. ...

during the 1750s, the 1770s and in 1786.

The clearest description of smallpox from pre-modern times was given in the 9th century by the Persian physician, Muhammad ibn Zakariya ar-Razi, known in the West as "Rhazes", who was the first to differentiate smallpox from measles

Measles (probably from Middle Dutch or Middle High German ''masel(e)'', meaning "blemish, blood blister") is a highly contagious, Vaccine-preventable diseases, vaccine-preventable infectious disease caused by Measles morbillivirus, measles v ...

and chickenpox

Chickenpox, also known as varicella ( ), is a highly contagious disease caused by varicella zoster virus (VZV), a member of the herpesvirus family. The disease results in a characteristic skin rash that forms small, itchy blisters, which ...

in his ''Kitab fi al-jadari wa-al-hasbah'' (''The Book of Smallpox and Measles'').

Smallpox was a leading cause of death in the 18th century. Every seventh child born in Russia

Russia, or the Russian Federation, is a country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia. It is the list of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the world, and extends across Time in Russia, eleven time zones, sharing Borders ...

died from smallpox. It killed an estimated 400,000 Europeans each year in the 18th century, including five reigning European monarchs. Most people became infected during their lifetimes, and about 30% of people infected with smallpox died from the disease, presenting a severe selection pressure on the resistant survivors.

In northern Japan, Ainu population decreased drastically in the 19th century, due in large part to infectious diseases like smallpox brought by Japanese settlers pouring into Hokkaido

is the list of islands of Japan by area, second-largest island of Japan and comprises the largest and northernmost prefectures of Japan, prefecture, making up its own list of regions of Japan, region. The Tsugaru Strait separates Hokkaidō fr ...

.

The Franco-Prussian War

The Franco-Prussian War or Franco-German War, often referred to in France as the War of 1870, was a conflict between the Second French Empire and the North German Confederation led by the Kingdom of Prussia. Lasting from 19 July 1870 to 28 Janua ...

triggered a smallpox pandemic of 1870–1875 that claimed 500,000 lives; while vaccination was mandatory in the Prussian army, many French soldiers were not vaccinated. Smallpox outbreaks among French prisoners of war spread to the German civilian population and other parts of Europe. Ultimately, this public health disaster inspired stricter legislation in Germany and England, though not in France.

In 1849 nearly 13% of all Calcutta

Kolkata, also known as Calcutta (List of renamed places in India#West Bengal, its official name until 2001), is the capital and largest city of the Indian States and union territories of India, state of West Bengal. It lies on the eastern ba ...

deaths were due to smallpox. Between 1868 and 1907, there were approximately 4.7 million deaths from smallpox in India

India, officially the Republic of India, is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area; the List of countries by population (United Nations), most populous country since ...

. Between 1926 and 1930, there were 979,738 cases of smallpox with a mortality of 42.3%.

African epidemics

One of the oldest records of what may have been an encounter with smallpox in Africa is associated with the elephant war circa AD 568 CE, when after fighting a siege in Mecca, Ethiopian troops contracted the disease which they carried with them back to Africa.

Arab ports in Coastal towns in Africa likely contributed to the importation of smallpox into Africa, as early as the 13th century, though no records exist until the 16th century. Upon invasion of these towns by tribes in the interior of Africa, a severe epidemic affected all African inhabitants while sparing the Portuguese. Densely populated areas of Africa connected to the Mediterranean, Nubia and Ethiopia by caravan route likely were affected by smallpox since the 11th century, though written records do not appear until the introduction of the slave trade in the 16th century.

The

One of the oldest records of what may have been an encounter with smallpox in Africa is associated with the elephant war circa AD 568 CE, when after fighting a siege in Mecca, Ethiopian troops contracted the disease which they carried with them back to Africa.

Arab ports in Coastal towns in Africa likely contributed to the importation of smallpox into Africa, as early as the 13th century, though no records exist until the 16th century. Upon invasion of these towns by tribes in the interior of Africa, a severe epidemic affected all African inhabitants while sparing the Portuguese. Densely populated areas of Africa connected to the Mediterranean, Nubia and Ethiopia by caravan route likely were affected by smallpox since the 11th century, though written records do not appear until the introduction of the slave trade in the 16th century.

The enslavement

Slavery is the ownership of a person as property, especially in regards to their labour. Slavery typically involves compulsory work, with the slave's location of work and residence dictated by the party that holds them in bondage. Enslavemen ...

of Africans continued to spread smallpox to the entire continent, with raiders pushing farther inland along caravan routes in search of people to enslave. The effects of smallpox could be seen along caravan routes, and those who were not affected along the routes were still likely to become infected either waiting to be put onboard or on board ships.

Smallpox in Angola was likely introduced shortly after Portuguese settlement of the area in 1484. The 1864 epidemic killed 25,000 inhabitants, one third of the total population in that same area. In 1713, an outbreak occurred in South Africa after a ship from India docked at Cape Town, bringing infected laundry ashore. Many of the settler European population suffered, and whole clans of the Khoisan

Khoisan ( ) or () is an Hypernymy and hyponymy, umbrella term for the various Indigenous peoples of Africa, indigenous peoples of Southern Africa who traditionally speak non-Bantu languages, combining the Khoekhoen and the San people, Sān peo ...

people were wiped out. A second outbreak occurred in 1755, again affecting both the white

White is the lightest color and is achromatic (having no chroma). It is the color of objects such as snow, chalk, and milk, and is the opposite of black. White objects fully (or almost fully) reflect and scatter all the visible wa ...

population and the Khoisan. The disease spread further, completely eradicating several Khosian clans, all the way to the Kalahari desert. A third outbreak in 1767 similarly affected the Khoisan and Bantu peoples. But the European colonial settlers

A settler or a colonist is a person who establishes or joins a permanent presence that is separate to existing communities. The entity that a settler establishes is a Human settlement, settlement. A settler is called a pioneer if they are among ...

were not affected nearly to the extent that they were in the first two outbreaks, it has been speculated this is because of variolation

Variolation was the method of inoculation first used to immunize individuals against smallpox (''Variola'') with material taken from a patient or a recently variolated individual, in the hope that a mild, but protective, infection would result. On ...

. Continued enslavement

Slavery is the ownership of a person as property, especially in regards to their labour. Slavery typically involves compulsory work, with the slave's location of work and residence dictated by the party that holds them in bondage. Enslavemen ...

operations brought smallpox to Cape Town again in 1840, taking the lives of 2500 people, and then to Uganda in the 1840s. It is estimated that up to eighty percent of the Griqua tribe was exterminated by smallpox in 1831, and whole tribes were being wiped out in Kenya up until 1899. Along the Zaire river basin were areas where no one survived the epidemics, leaving the land devoid of human life. In Ethiopia and the Sudan, six epidemics are recorded for the 19th century: 1811–1813, 1838–1839, 1865–1866, 1878–1879, 1885–1887, and 1889–1890.

Epidemics in the Americas

After first contacts withEuropeans

Europeans are the focus of European ethnology, the field of anthropology related to the various ethnic groups that reside in the states of Europe. Groups may be defined by common ancestry, language, faith, historical continuity, etc. There are ...

and Africans

The ethnic groups of Africa number in the thousands, with each ethnicity generally having their own language (or dialect of a language) and culture. The ethnolinguistic groups include various Afroasiatic, Khoisan, Niger-Congo, and Nilo-Sahara ...

, some believe that the death of 90–95% of the native population of the New World

The term "New World" is used to describe the majority of lands of Earth's Western Hemisphere, particularly the Americas, and sometimes Oceania."America." ''The Oxford Companion to the English Language'' (). McArthur, Tom, ed., 1992. New York: ...

was caused by Old World

The "Old World" () is a term for Afro-Eurasia coined by Europeans after 1493, when they became aware of the existence of the Americas. It is used to contrast the continents of Africa, Europe, and Asia in the Eastern Hemisphere, previously ...

diseases. It is suspected that smallpox was the chief culprit and responsible for killing nearly all of the native inhabitants of the Americas. For more than 200 years, this disease affected all new world populations, mostly without intentional European transmission, from contact in the early 16th century until possibly as late as the French and Indian Wars (1754–1767).

In 1519 Hernán Cortés

Hernán Cortés de Monroy y Pizarro Altamirano, 1st Marquis of the Valley of Oaxaca (December 1485 – December 2, 1547) was a Spanish ''conquistador'' who led an expedition that caused the fall of the Aztec Empire and brought large portions o ...

landed on the shores of what is now Mexico

Mexico, officially the United Mexican States, is a country in North America. It is the northernmost country in Latin America, and borders the United States to the north, and Guatemala and Belize to the southeast; while having maritime boundar ...

and what was then the Aztec Empire

The Aztec Empire, also known as the Triple Alliance (, Help:IPA/Nahuatl, �jéːʃkaːn̥ t͡ɬaʔtoːˈlóːjaːn̥ or the Tenochca Empire, was an alliance of three Nahuas, Nahua altepetl, city-states: , , and . These three city-states rul ...

. In 1520 another group of Spanish arrived in Mexico from Hispaniola

Hispaniola (, also ) is an island between Geography of Cuba, Cuba and Geography of Puerto Rico, Puerto Rico in the Greater Antilles of the Caribbean. Hispaniola is the most populous island in the West Indies, and the second-largest by List of C ...

, bringing with them the smallpox which had already been ravaging that island for two years. When Cortés heard about the other group, he went and defeated them. In this contact, one of Cortés's men contracted the disease. When Cortés returned to Tenochtitlan

, also known as Mexico-Tenochtitlan, was a large Mexican in what is now the historic center of Mexico City. The exact date of the founding of the city is unclear, but the date 13 March 1325 was chosen in 1925 to celebrate the 600th annivers ...

, he brought the disease with him.

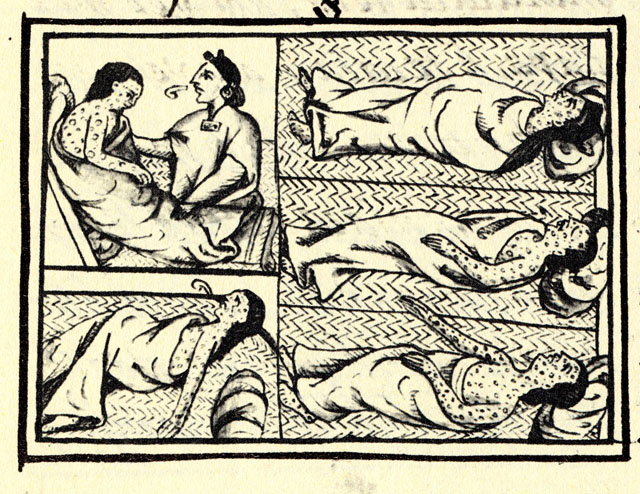

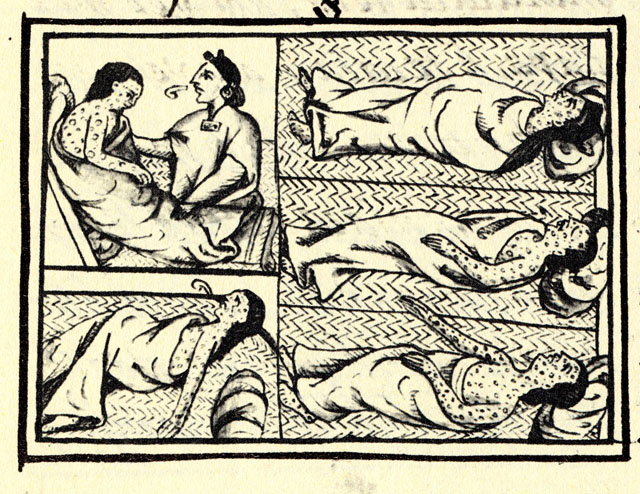

Soon, the Aztecs rose up in rebellion against Cortés and his men. Outnumbered, the Spanish were forced to flee. In the fighting, the Spanish soldier carrying smallpox died. Cortés would not return to the capital until August 1521. In the meantime smallpox devastated the Aztec population. It killed most of the Aztec army and 25% of the overall population. The Spanish Franciscan Motolinia left this description: "As the Indians did not know the remedy of the disease…they died in heaps, like bedbugs. In many places it happened that everyone in a house died and, as it was impossible to bury the great number of dead, they pulled down the houses over them so that their homes become their tombs." On Cortés's return, he found the Aztec army's chain of command in ruins. The soldiers who still lived were weak from the disease. Cortés then easily defeated the Aztecs and entered Tenochtitlán. The Spaniards said that they could not walk through the streets without stepping on the bodies of smallpox victims.

The effects of smallpox on Tahuantinsuyu (or the Inca

The Inca Empire, officially known as the Realm of the Four Parts (, ), was the largest empire in pre-Columbian America. The administrative, political, and military center of the empire was in the city of Cusco. The History of the Incas, Inca ...

empire) were even more devastating. Beginning in Colombia

Colombia, officially the Republic of Colombia, is a country primarily located in South America with Insular region of Colombia, insular regions in North America. The Colombian mainland is bordered by the Caribbean Sea to the north, Venezuel ...

, smallpox spread rapidly before the Spanish invaders first arrived in the empire. The spread was probably aided by the efficient Inca road system. Within months, the disease had killed the Incan Emperor Huayna Capac

Huayna Capac (; Cuzco Quechua: ''Wayna Qhapaq'' ) (before 14931527) was the third Sapa Inca of Tawantinsuyu, the Inca Empire. He was the son of and successor to Túpac Inca Yupanqui,Sarmiento de Gamboa, Pedro; 2015, originally published in Sp ...

, his successor, and most of the other leaders. Two of his surviving sons warred for power and, after a bloody and costly war, Atahualpa

Atahualpa (), also Atawallpa or Ataw Wallpa ( Quechua) ( 150226 July 1533), was the last effective Inca emperor, reigning from April 1532 until his capture and execution in July of the following year, as part of the Spanish conquest of the In ...

become the new emperor. As Atahualpa was returning to the capital Cuzco

Cusco or Cuzco (; or , ) is a city in southeastern Peru, near the Sacred Valley of the Andes mountain range and the Huatanay river. It is the capital of the eponymous province and department.

The city was the capital of the Inca Empire unti ...

, Francisco Pizarro

Francisco Pizarro, Marquess of the Atabillos (; ; – 26 June 1541) was a Spanish ''conquistador'', best known for his expeditions that led to the Spanish conquest of the Inca Empire.

Born in Trujillo, Cáceres, Trujillo, Spain, to a poor fam ...

arrived and through a series of deceits captured the young leader and his best general. Within a few years smallpox claimed between 60% and 90% of the Inca population, with other waves of European disease weakening them further. A handful of historians argue that a disease called Bartonellosis might have been responsible for some outbreaks of illness, but this opinion is in the scholarly minority. The effects of Bartonellosis were depicted in the ceramics of the Moche people of ancient Peru

Peru, officially the Republic of Peru, is a country in western South America. It is bordered in the north by Ecuador and Colombia, in the east by Brazil, in the southeast by Bolivia, in the south by Chile, and in the south and west by the Pac ...

.

Even after the two largest empires of the Americas were defeated by the virus and disease, smallpox continued its march of death. In 1561, smallpox reached Chile

Chile, officially the Republic of Chile, is a country in western South America. It is the southernmost country in the world and the closest to Antarctica, stretching along a narrow strip of land between the Andes, Andes Mountains and the Paci ...

by sea, when a ship carrying the new governor Francisco de Villagra landed at La Serena. Chile had previously been isolated by the Atacama Desert

The Atacama Desert () is a desert plateau located on the Pacific Ocean, Pacific coast of South America, in the north of Chile. Stretching over a strip of land west of the Andes Mountains, it covers an area of , which increases to if the barre ...

and Andes Mountains

The Andes ( ), Andes Mountains or Andean Mountain Range (; ) are the longest continental mountain range in the world, forming a continuous highland along the western edge of South America. The range is long and wide (widest between 18°S ...

from Peru, but at the end of 1561 and in early 1562, it ravaged the Chilean native population. Chronicles and records of the time left no accurate data on mortality but more recent estimates are that the natives lost 20 to 25 percent of their population. The Spanish historian Marmolejo said that gold mines had to shut down when all their Indian labor died. Mapuche

The Mapuche ( , ) also known as Araucanians are a group of Indigenous peoples of the Americas, Indigenous inhabitants of south-central Chile and southwestern Argentina, including parts of Patagonia. The collective term refers to a wide-ranging e ...

fighting Spain in Araucanía regarded the epidemic as a magical attempt by Francisco de Villagra to exterminate them because he could not defeat them in the Arauco War

The Arauco War was a long-running conflict between colonial Spaniards and the Mapuche people, mostly fought in the Araucanía region of Chile. The conflict began at first as a reaction to the Spanish conquerors attempting to establish cities a ...

.Alonso de Góngora MarmolejHistoria de Chile desde su descubrimiento hasta el año 1575

. Cervantesvirtual.com. Retrieved on 2011-12-06. In 1633 in

Plymouth, Massachusetts

Plymouth ( ; historically also spelled as Plimouth and Plimoth) is a town in and the county seat of Plymouth County, Massachusetts, United States. Located in Greater Boston, the town holds a place of great prominence in American history, folklor ...

, the Native Americans were struck by the virus. As it had done elsewhere, the virus wiped out entire population groups of Native Americans. It reached Mohawks

The Mohawk, also known by their own name, (), are an Indigenous people of North America and the easternmost nation of the Haudenosaunee, or Iroquois Confederacy (also known as the Five Nations or later the Six Nations).

Mohawk are an Iroquoi ...

in 1634, the Lake Ontario

Lake Ontario is one of the five Great Lakes of North America. It is bounded on the north, west, and southwest by the Canadian province of Ontario, and on the south and east by the U.S. state of New York (state), New York. The Canada–United Sta ...

area in 1636, and the lands of the Iroquois

The Iroquois ( ), also known as the Five Nations, and later as the Six Nations from 1722 onwards; alternatively referred to by the Endonym and exonym, endonym Haudenosaunee ( ; ) are an Iroquoian languages, Iroquoian-speaking Confederation#Ind ...

by 1679.

A particularly virulent sequence of smallpox outbreaks took place in Boston, Massachusetts

Boston is the capital and most populous city in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Massachusetts in the United States. The city serves as the cultural and Financial centre, financial center of New England, a region of the Northeas ...

. From 1636 to 1698, Boston endured six epidemics. In 1721, the most severe epidemic occurred. The entire population fled the city, bringing the virus to the rest of the Thirteen Colonies

The Thirteen Colonies were the British colonies on the Atlantic coast of North America which broke away from the British Crown in the American Revolutionary War (1775–1783), and joined to form the United States of America.

The Thirteen C ...

.

During the siege of Fort Pitt, as recorded in his journal by sundries trader and militia Captain, William Trent, on June 24, 1763, dignitaries from the Delaware tribe met with Fort Pitt officials, warned them of "great numbers of Indians" coming to attack the fort, and pleaded with them to leave the fort while there was still time. The commander of the fort refused to abandon the fort. Instead, the British gave as gifts two blankets, one silk handkerchief and one linen from the smallpox hospital, to two Delaware Indian delegates. The dignitaries were met again later and they seemingly hadn't contracted smallpox. A relatively small outbreak of smallpox had begun spreading earlier that spring, with a hundred dying from it among Native American tribes in the Ohio Valley and Great Lakes area through 1763 and 1764. The effectiveness of the biological warfare itself remains unknown, and the method used is inefficient compared to respiratory transmission and these attempts to spread the disease are difficult to differentiate from epidemics occurring from previous contacts with colonists, as smallpox outbreaks happened every dozen or so years.

In the late 1770s, during the American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was the armed conflict that comprised the final eight years of the broader American Revolution, in which Am ...

, smallpox returned once more and killed thousands. Peter Kalm in his ''Travels in North America'', described how in that period, the dying Indian villages became overrun with wolves

The wolf (''Canis lupus''; : wolves), also known as the grey wolf or gray wolf, is a canine native to Eurasia and North America. More than thirty subspecies of ''Canis lupus'' have been recognized, including the dog and dingo, though gr ...

feasting on the corpses and weakened survivors. During the 1770s, smallpox killed at least 30% of the Northwestern Native Americans, killing tens of thousands.SmallpoxThe Canadian Encyclopedia

''The Canadian Encyclopedia'' (TCE; ) is the national encyclopedia of Canada, published online by the Toronto-based historical organization Historica Canada, with financial support by the federal Department of Canadian Heritage and Society of Com ...

Lange, Greg. (2003-01-23Smallpox epidemic ravages Native Americans on the northwest coast of North America in the 1770s

. Historyink.com. Retrieved on 2011-12-06. The smallpox epidemic of 1780–1782 brought devastation and drastic depopulation among the

Plains Indians

Plains Indians or Indigenous peoples of the Great Plains and Canadian Prairies are the Native American tribes and First Nations peoples who have historically lived on the Interior Plains (the Great Plains and Canadian Prairies) of North ...

. This epidemic is a classic instance of European immunity and non-European vulnerability. It is probable that the Indians contracted the disease from the 'Snake Indians' on the Mississippi

Mississippi ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern and Deep South regions of the United States. It borders Tennessee to the north, Alabama to the east, the Gulf of Mexico to the south, Louisiana to the s ...

. From there it spread eastward and northward to the Saskatchewan River. According to David Thompson's account, the first to hear of the disease were fur traders from the Hudson's House on October 15, 1781. A week later, reports were made to William Walker and William Tomison, who were in charge of the Hudson and Cumberland Hudson's Bay Company

The Hudson's Bay Company (HBC), originally the Governor and Company of Adventurers of England Trading Into Hudson’s Bay, is a Canadian holding company of department stores, and the oldest corporation in North America. It was the owner of the ...

posts. By February, the disease spread as far as the Basquia Tribe. Smallpox attacked whole tribes and left few survivors. E. E. Rich described the epidemic by saying that "Families lay unburied in their tents while the few survivors fled, to spread the disease." After reading Tomison's journals, Houston and Houston calculated that, of the Indians who traded at the Hudson and Cumberland houses, 95% died of smallpox. Paul Hackett adds to the mortality numbers suggesting that perhaps up to one-half to three-quarters of the Ojibway

The Ojibwe (; Ojibwe writing systems#Ojibwe syllabics, syll.: ᐅᒋᐺ; plural: ''Ojibweg'' ᐅᒋᐺᒃ) are an Anishinaabe people whose homeland (''Ojibwewaki'' ᐅᒋᐺᐘᑭ) covers much of the Great Lakes region and the Great Plains, n ...

situated west of the Grand Portage died from the disease. The Cree

The Cree, or nehinaw (, ), are a Indigenous peoples of the Americas, North American Indigenous people, numbering more than 350,000 in Canada, where they form one of the country's largest First Nations in Canada, First Nations. They live prim ...

also suffered a casualty rate of approximately 75% with similar effects found in the Lowland Cree. By 1785 the Sioux Indians of the great plains had also been affected. Not only did smallpox devastate the Indian population, it did so in an unforgiving way. William Walker described the epidemic stating that "the Indians reall Dying by this Distemper … lying Dead about the Barren Ground like a rotten sheep, their Tents left standing & the Wild beast Devouring them."

In 1799, the physician Valentine Seaman administered the first smallpox vaccine in the United States. He gave his children a smallpox vaccination using a serum acquired from Edward Jenner

Edward Jenner (17 May 1749 – 26 January 1823) was an English physician and scientist who pioneered the concept of vaccines and created the smallpox vaccine, the world's first vaccine. The terms ''vaccine'' and ''vaccination'' are derived f ...

, the British physician who invented the vaccine from fluid taken from cowpox lesions. Though vaccines were misunderstood and mistrusted at the time, Seaman advocated their use and, in 1802, coordinated a free vaccination program for the poor in New York City.

By 1832, the federal government of the United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

established a smallpox vaccination program for Native Americans.

In 1900 starting in New York City, smallpox reared its head once again and started a sociopolitical battle with lines drawn between the rich and poor, white and black. In populations of railroad and migrant workers who traveled from city to city the disease had reached an endemic low boil. This fact did not bother the government at the time, nor did it spur them to action. Despite the general acceptance of the germ theory of disease

The germ theory of disease is the currently accepted scientific theory for many diseases. It states that microorganisms known as pathogens or "germs" can cause disease. These small organisms, which are too small to be seen without magnification, ...

, pioneered by John Snow

John Snow (15 March 1813 – 16 June 1858) was an English physician and a leader in the development of anaesthesia and medical hygiene. He is considered one of the founders of modern epidemiology and early germ theory, in part because of hi ...

in 1849, smallpox was still thought to be mostly a malady that followed the less-distinct guidelines of a "filth" disease, and therefore would only affect the "lower classes".

The last major smallpox epidemic in the United States occurred in Boston

Boston is the capital and most populous city in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Massachusetts in the United States. The city serves as the cultural and Financial centre, financial center of New England, a region of the Northeas ...

, Massachusetts

Massachusetts ( ; ), officially the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It borders the Atlantic Ocean and the Gulf of Maine to its east, Connecticut and Rhode ...

throughout a three-year period, between 1901 and 1903. During this three-year period, 1596 cases of the disease occurred throughout the city. Of those cases, nearly 300 people died. As a whole, the epidemic had a 17% fatality rate.

Those who were infected with the disease were detained in quarantine facilities in the hopes of protecting others from getting sick. These quarantine facilities, or pesthouses, were mostly located on Southampton Street. As the outbreak worsened, men were also moved to hospitals on Gallop's Island. Women and children were primarily sent to Southampton Street. Smallpox patients were not allowed in regular hospital facilities throughout the city, for fear the sickness would spread among the already sick.

A reflection of the previous outbreak that occurred in New York, the poor and homeless were blamed for the sickness's spread. In response to this belief, the city instructed teams of physicians to vaccinate anyone living in inexpensive housing.

In an effort to control the outbreak, the Boston Board of Health began voluntary vaccination programs. Individuals could receive free vaccines at their

workplaces or at different stations set up throughout the city. By the end of 1901, some 40,000 of the city's residents had received a smallpox vaccine. However, despite the city's efforts, the epidemic continued to grow. In January 1902, a door-to-door vaccination program was initiated. Health officials were instructed to compel individuals to receive vaccination, pay a $5 fine, or face 15 days in prison. This door-to-door program was met by some resistance as some individuals feared the vaccines to be unsafe and ineffective. Others felt compulsory vaccination in itself was a problem that violated an individual's civil liberties.

This program of compulsory vaccination eventually led to the famous '' Jacobson v. Massachusetts'' case. The case was the result of a

Those who were infected with the disease were detained in quarantine facilities in the hopes of protecting others from getting sick. These quarantine facilities, or pesthouses, were mostly located on Southampton Street. As the outbreak worsened, men were also moved to hospitals on Gallop's Island. Women and children were primarily sent to Southampton Street. Smallpox patients were not allowed in regular hospital facilities throughout the city, for fear the sickness would spread among the already sick.

A reflection of the previous outbreak that occurred in New York, the poor and homeless were blamed for the sickness's spread. In response to this belief, the city instructed teams of physicians to vaccinate anyone living in inexpensive housing.

In an effort to control the outbreak, the Boston Board of Health began voluntary vaccination programs. Individuals could receive free vaccines at their

workplaces or at different stations set up throughout the city. By the end of 1901, some 40,000 of the city's residents had received a smallpox vaccine. However, despite the city's efforts, the epidemic continued to grow. In January 1902, a door-to-door vaccination program was initiated. Health officials were instructed to compel individuals to receive vaccination, pay a $5 fine, or face 15 days in prison. This door-to-door program was met by some resistance as some individuals feared the vaccines to be unsafe and ineffective. Others felt compulsory vaccination in itself was a problem that violated an individual's civil liberties.

This program of compulsory vaccination eventually led to the famous '' Jacobson v. Massachusetts'' case. The case was the result of a Cambridge

Cambridge ( ) is a List of cities in the United Kingdom, city and non-metropolitan district in the county of Cambridgeshire, England. It is the county town of Cambridgeshire and is located on the River Cam, north of London. As of the 2021 Unit ...

resident's refusal to be vaccinated. Henning Jacobson, a Swedish immigrant, refused vaccination out of fear it would cause him illness. He claimed a previous smallpox vaccine had made him sick as a child. Rather than pay the five dollar fine, he challenged the state's authority on forcing people to receive vaccination. His case was lost at the state level, but Jacobson appealed the ruling, and so, the case was taken up by the Supreme Court. In 1905 the Supreme Court

In most legal jurisdictions, a supreme court, also known as a court of last resort, apex court, high (or final) court of appeal, and court of final appeal, is the highest court within the hierarchy of courts. Broadly speaking, the decisions of ...

upheld the Massachusetts law: it was ruled Jacobson could not refuse the mandatory vaccination.

In Canada, between 1702 and 1703, nearly a quarter of the population of Quebec city died due to a smallpox epidemic.

Pacific epidemics

Australia

Smallpox was brought to Australia in the 18th century. The first recorded outbreak, in April 1789, about 16 months after the arrival of theFirst Fleet

The First Fleet were eleven British ships which transported a group of settlers to mainland Australia, marking the beginning of the History of Australia (1788–1850), European colonisation of Australia. It consisted of two Royal Navy vessel ...

, devastated the Aboriginal population. Governor Arthur Phillip

Arthur Phillip (11 October 1738 – 31 August 1814) was a British Royal Navy officer who served as the first Governor of New South Wales, governor of the Colony of New South Wales.

Phillip was educated at Royal Hospital School, Gree ...

said that about half of the Aboriginal people living around Sydney Cove

Sydney Cove (Eora language, Eora: ) is a bay on the southern shore of Sydney Harbour, one of several harbours in Port Jackson, on the coast of Sydney, New South Wales. Sydney Cove is a focal point for community celebrations, due to its central ...

died during the outbreak. Some later estimates have been higher, though precise figures are hard to determine, and Professors Carmody and Hunter argued in 2014 that the figure was more like 30%. There is an ongoing debate, with links to the "History wars", concerning two main rival theories about how smallpox first entered the continent. (Another hypothesis suggested that the French brought it in 1788, but the timeline does not fit.) The central hypotheses of these theories suggest that smallpox was transmitted to Indigenous Australians

Indigenous Australians are people with familial heritage from, or recognised membership of, the various ethnic groups living within the territory of contemporary Australia prior to History of Australia (1788–1850), British colonisation. The ...

by either:

* the First Fleet of British settlers to arrive in the Colony of New South Wales

The Colony of New South Wales was a colony of the British Empire from 1788 to 1901, when it became a State of the Commonwealth of Australia. At its greatest extent, the colony of New South Wales included the present-day Australian states of New ...

, who arrived in January 1788 (whether deliberately or accidentally); or

* Makassan mariners visiting northern Australia.

In 1914, Dr J. H. L. Cumpston, director of the Australian Quarantine Service tentatively put forward the hypothesis that smallpox arrived with British settlers.Cumpston, JHL "The History of Small-Pox in Australia 1788–1908", Government Printer (1914) Melb. Cumpston's theory was most forcefully reiterated by the economic historian Noel Butlin, in his book ''Our Original Aggression'' (1983). Likewise David Day, in ''Claiming a Continent: A New History of Australia'' (2001), suggested that members of Sydney's garrison of Royal Marines

The Royal Marines provide the United Kingdom's amphibious warfare, amphibious special operations capable commando force, one of the :Fighting Arms of the Royal Navy, five fighting arms of the Royal Navy, a Company (military unit), company str ...

may have attempted to use smallpox as a biological weapon in 1789. However, in 2002, historian John Connor stated that Day's theory was "unsustainable". That same year, theories that smallpox was introduced with settlers, deliberately or otherwise, were contested in a full-length book by historian Judy Campbell: ''Invisible Invaders: Smallpox and Other Diseases in Aboriginal Australia 1780–1880'' (2002). Campbell consulted, during the writing of her book, Frank Fenner, who had overseen the final stages of a successful campaign by the World Health Organization

The World Health Organization (WHO) is a list of specialized agencies of the United Nations, specialized agency of the United Nations which coordinates responses to international public health issues and emergencies. It is headquartered in Gen ...

(WHO) to eradicate smallpox. Campbell argued that scientific evidence concerning the viability of variolous matter (used for inoculation) did not support the possibility of the disease being brought to Australia on the long voyage from Europe. Campbell also noted that there was no evidence of Aboriginal people ever having been exposed to the variolous matter, merely speculation that they may have been. Later authors, such as Christopher Warren, and Craig Mear continued to argue that smallpox emanated from the importation of variolous matter on the First Fleet. Warren (2007) suggested that Campbell had erred in assuming that high temperatures would have sterilised the British supply of smallpox. H. A. Willis (2010), in a survey of the literature discussed above, endorsed Campbell's argument. In response, Warren (2011) suggested that Willis had not taken into account research on how heat affects the smallpox virus, cited by the WHO

The World Health Organization (WHO) is a specialized agency of the United Nations which coordinates responses to international public health issues and emergencies. It is headquartered in Geneva, Switzerland, and has 6 regional offices and 15 ...

. Willis (2011) replied that his position was supported by a closer reading of Frank Fenner's report to the WHO (1988) and invited readers to consult that report online.

The rival hypothesis, that the 1789 outbreak was introduced to Australia by visitors from Makassar

Makassar ( ), formerly Ujung Pandang ( ), is the capital of the Indonesian Provinces of Indonesia, province of South Sulawesi. It is the largest city in the region of Eastern Indonesia and the country's fifth-largest urban center after Jakarta, ...

, came to prominence in 2002, with Judy Campbell's book ''Invisible Invaders''. Campbell expanded upon the opinion of C. C. Macknight (1986), an authority on the interaction between indigenous Australians and Makassans. Citing the scientific opinion of Fenner (who wrote the foreword to her book) and historical documents, Campbell argued that the 1789 outbreak was introduced to Australia by Makassans, from where it spread overland.Campbell, Judy; 2002, ''Invisible Invaders: Smallpox and Other Diseases in Aboriginal Australia 1780–1880'', Carlton, Melbourne University Press, pp. 60–62, 80–81, 194–96, 201, 216–17 Nevertheless, Michael Bennett in a 2009 article in ''Bulletin of the History of Medicine'', argued that imported "variolous matter" may have been the source of the 1789 epidemic in Australia. In 2011, Macknight re-entered the debate, declaring: "The overwhelming probability must be that it mallpoxwas introduced, like the later epidemics, by akassantrepangers on the north coast and spread across the continent to arrive in Sydney quite independently of the new settlement there". Warren (2013) disputed this, on the grounds that: there was no suitable smallpox in Makassar before 1789; there were no trade routes suitable for transmission to Port Jackson

Port Jackson, commonly known as Sydney Harbour, is a natural harbour on the east coast of Australia, around which Sydney was built. It consists of the waters of Sydney Harbour, Middle Harbour, North Harbour and the Lane Cove and Parramatta ...

; the theory of a Makassan source for smallpox in 1789 was contradicted by Aboriginal oral tradition

Oral tradition, or oral lore, is a form of human communication in which knowledge, art, ideas and culture are received, preserved, and transmitted orally from one generation to another.Jan Vansina, Vansina, Jan: ''Oral Tradition as History'' (19 ...

; and, the earliest point at which there was evidence of smallpox entering Australia with Makassan visitors was around 1824. Public health

Public health is "the science and art of preventing disease, prolonging life and promoting health through the organized efforts and informed choices of society, organizations, public and private, communities and individuals". Analyzing the de ...

expert Mark Wenitong, a Kabi Kabi man, and John Maynard, Emeritus professor of Aboriginal History at the University of Newcastle agree that this is highly unlikely, with the added obstacle of very low population density between the north coast and Sydney Cove.

A quite separate third theory, endorsed by the pathologist Dr G.E. Ford, with support from the academics Curson, Wright and Hunter, holds that the deadly disease was not smallpox but the far more infectious chickenpox, to which the Eora Aboriginal peoples had no resistance.

John Carmody, then at the University of Sydney

The University of Sydney (USYD) is a public university, public research university in Sydney, Australia. Founded in 1850, it is the oldest university in both Australia and Oceania. One of Australia's six sandstone universities, it was one of the ...

School of Medical Sciences, suggested in 2010 that the epidemic was far more likely to have been chickenpox

Chickenpox, also known as varicella ( ), is a highly contagious disease caused by varicella zoster virus (VZV), a member of the herpesvirus family. The disease results in a characteristic skin rash that forms small, itchy blisters, which ...

, as none of the European colonists were threatened by it, as he would have expected to happen. However Wenitong and Maynard continue to believe that there is strong evidence that it was smallpox.

Another major outbreak was observed in 1828–30, near Bathurst, New South Wales

Bathurst () is a city in the Central Tablelands of New South Wales, Australia. Bathurst is about 200 kilometres (120 mi) west-northwest of Sydney and is the seat of the Bathurst Region, Bathurst Regional Council. Founded in 1815, Bathurst is ...

. A third epidemic occurred in the Northern Territory

The Northern Territory (abbreviated as NT; known formally as the Northern Territory of Australia and informally as the Territory) is an states and territories of Australia, Australian internal territory in the central and central-northern regi ...

and northern Western Australia from the mid-1860s, until at least 1870.

Polynesia

Elsewhere in the Pacific, smallpox killed many indigenous Polynesians. Nevertheless,Alfred Crosby

Alfred Worcester Crosby Jr. (January 15, 1931 – March 14, 2018) was a professor of History, Geography, and American Studies at the University of Texas at Austin, and University of Helsinki. He was the author of books including '' The Columbian ...

, in his major work, '' Ecological Imperialism: The Biological Expansion of Europe, 900-1900'' (1986) showed that in 1840 a ship with smallpox on it was successfully quarantined, preventing an epidemic amongst Māori of New Zealand

New Zealand () is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and List of islands of New Zealand, over 600 smaller islands. It is the List of isla ...

. The only major outbreak in New Zealand was a 1913 epidemic, which affected Māori in northern New Zealand and nearly wiped out the Rapa Nui

Easter Island (, ; , ) is an island and special territory of Chile in the southeastern Pacific Ocean, at the southeasternmost point of the Polynesian Triangle in Oceania. The island is renowned for its nearly 1,000 extant monumental statues, ...

of Easter Island

Easter Island (, ; , ) is an island and special territory of Chile in the southeastern Pacific Ocean, at the southeasternmost point of the Polynesian Triangle in Oceania. The island is renowned for its nearly 1,000 extant monumental statues, ...

(''Rapa Nui''), was reported by Te Rangi Hiroa (Dr Peter Buck) to a medical congress in Melbourne in 1914.

Micronesia

The whaler ship ''Delta'' brought smallpox to the Micronesian island ofPohnpei

Pohnpei (formerly known as Ponape or Ascension, from Pohnpeian: "upon (''pohn'') a stone altar (''pei'')") is an island of the Senyavin Islands which are part of the larger Caroline Islands group. It belongs to Pohnpei State, one of the fou ...

on 28 February 1854. The Pohnpeians

The Micronesians or Micronesian peoples are various closely related ethnic groups native to Micronesia, a region of Oceania in the Pacific Ocean. They are a part of the Austronesian ethnolinguistic group, which has an Urheimat in Taiwan.

Ethno ...

reacted by first feasting their offended spirits and then resorted hiding. The disease eventually wiped out more than half the island's population. The deaths of chiefs threw Pohnpeian society into disarray, and the people started blaming the God of the Christian missionaries. The Christian missionaries themselves saw the epidemic as God's punishment for the people and offered the natives inoculations, though often withheld such treatment from the priests. The epidemic abated in October 1854.

Eradication

Early in history, it was observed that those who had contracted smallpox once were never struck by the disease again. Thought to have been discovered by accident, it became known that those who contracted smallpox through a break in the skin in which smallpox matter was inserted received a less severe reaction than those who contracted it naturally. This realization led to the practice of purposely infecting people with matter from smallpox scabs in order to protect them later from a more severe reaction. This practice, known today asvariolation

Variolation was the method of inoculation first used to immunize individuals against smallpox (''Variola'') with material taken from a patient or a recently variolated individual, in the hope that a mild, but protective, infection would result. On ...

, was first practiced in China in the 10th century. Methods of carrying out the procedure varied depending upon location. Variolation was the sole method of protection against smallpox other than quarantine until Edward Jenner's discovery of the inoculating abilities of cowpox

Cowpox is an infectious disease caused by Cowpox virus (CPXV). It presents with large blisters in the skin, a fever and swollen glands, historically typically following contact with an infected cow, though in the last several decades more often ...

against the smallpox virus in 1796. Efforts to protect populations against smallpox by way of vaccination followed for centuries after Jenner's discovery. It is thought that smallpox has been eradicated since 1979.

Variolation

The word variolation is synonymous with inoculation, insertion, en-grafting, or transplantation. The term is used to define insertion of smallpox matter, and distinguishes this procedure from vaccination, where cowpox matter was used to obtain a much milder reaction among patients.Asia

The practice ofvariolation

Variolation was the method of inoculation first used to immunize individuals against smallpox (''Variola'') with material taken from a patient or a recently variolated individual, in the hope that a mild, but protective, infection would result. On ...

(also known as inoculation

Inoculation is the act of implanting a pathogen or other microbe or virus into a person or other organism. It is a method of artificially inducing immunity against various infectious diseases. The term "inoculation" is also used more generally ...

) first came out of East Asia. First writings documenting variolation in China appear around 1500. Scabs from smallpox victims who had the disease in its mild form would be selected, and the powder was kept close to body temperature by means of keeping it close to the chest, killing the majority of the virus and resulting in a more mild case of smallpox. Scabs were generally used when a month old, but could be used more quickly in hot weather (15–20 days), and slower in winter (50 days). The process was carried out by taking eight smallpox scabs and crushing them in a mortar with two grains of '' Uvularia grandiflora'' in a mortar. The powder was administered nasally through a silver tube that was curved at its point, through the right nostril for boys and the left nostril for girls. A week after the procedure, those variolated would start to produce symptoms of smallpox, and recovery was guaranteed. In India, where the European colonizers came across variolation in the 17th century, a large, sharp needle was dipped into the pus collected from mature smallpox sores. Several punctures with this needle were made either below the deltoid muscle or in the forehead, and then were covered with a paste made from boiled rice. Variolation spread farther from India to other countries in south west Asia, and then to the Balkans.

Mauritius

In 1792 a slave-ship arrived on the French Indian Ocean island of Île de France (Mauritius) from South India, bringing with it smallpox. As the epidemic spread, a heated debate ensued over the practice of inoculation. The island was in the throes of revolutionary politics and the community of French colonists were acutely aware of their new rights as ‘citizens’. In the course of the smallpox epidemic, many of the political tensions the period came to focus on the question of inoculation, and were played out on the bodies of slaves. Whilst some citizens asserted their right, as property owners, to inoculate the slaves, others, equally vehemently, objected to the practice and asserted their right to protect their slaves from infection. Eighteenth-century colonial medicine was largely geared to keeping the bodies of slaves and workers productive and useful, but formal medicine never had a monopoly. Slaves on Île de France brought with them a rich array of medical beliefs and practices from Africa, India, and Madagascar. We have little direct historical evidence for these, but we do know that many slaves came from areas in which forms of smallpox inoculation were known and practiced.Europe

In 1713, Lady Mary Wortley Montagu's brother died of smallpox; she too contracted the virus two years later at the age of twenty-six, leaving her badly scarred. When her husband was made ambassador to

In 1713, Lady Mary Wortley Montagu's brother died of smallpox; she too contracted the virus two years later at the age of twenty-six, leaving her badly scarred. When her husband was made ambassador to Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

, she accompanied him to Constantinople. It was here that Lady Mary first came upon variolation. Two Greek women made it their business to engraft people with pox that left them un-scarred and unable to catch the pox again. In a letter, she wrote that she intended to have her own son undergo the process and would try to bring variolation into fashion in England.Halsal, Paul. "Modern History Sourcebook: Lady Mary Wortley Montagu (1689–1762): Smallpox Vaccination in Turkey." Fordham University. Accessed October 29, 2012. www.fordham.edu/halsall/mod/montagu-smallpox.asp Her son underwent the procedure, which was performed by Charles Maitland, and survived with no ill effects. When an epidemic broke out in London following her return, Lady Mary wanted to protect her daughter from the virus by having her variolated as well. Maitland performed the procedure, which was a success. The story made it to the newspapers and was a topic for discussion in London salons. Princess Caroline of Wales wanted her children variolated as well but first wanted more validation of the operation. She had both an orphanage and several convicts variolated before she was convinced. When the operation, performed by the King's surgeon, Claudius Amyand, and overseen by Maitland,Glynn, Ian and Jennifer Glynn. ''The Life and Death of Smallpox.'' New York: Cambridge University Press, 2004. was a success, variolation got the royal seal of approval and the practice became widespread. When the practice of variolation set off local epidemics

An epidemic (from Ancient Greek, Greek ἐπί ''epi'' "upon or above" and δῆμος ''demos'' "people") is the rapid spread of disease to a large number of Host (biology), hosts in a given population within a short period of time. For example ...

and caused death in two cases, public reaction was severe. Minister Edmund Massey, in 1772, called variolation dangerous and sinful, saying that people should handle the disease as the biblical figure Job did with his own tribulations, without interfering with God's test for mankind. Lady Mary still worked at promoting variolation but its practice waned until 1743.

Robert and Daniel Sutton further revived the practice of variolation in England by advertising their perfect variolation record, maintained by selecting patients who were healthy when variolated and were cared for during the procedure in the Sutton's own hygienic hospital. Other changes that the Suttons made to carrying out the variolation process include reducing and later abolishing the preparatory period before variolation was carried out, making more shallow incisions to distribute the smallpox matter, using smallpox matter collected on the fourth day of the disease, where the pus taken was still clear, and recommending that those inoculated get fresh air during recovery. The introduction of the shallower incision reduced both complications associated with the procedure and the severity of the reaction.Hopkins, Donald R. ''The Greatest Killer: Smallpox in History.'' Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2002. The prescription of fresh air caused controversy about Sutton's method and how effective it was in reality when those inoculated could walk about and spread the disease to those that had never before experienced smallpox. It was the Suttons who introduced the idea of mass variolation of an area when an epidemic broke out as means of protection to the inhabitants in that location.

News of variolation spread to the royal families of Europe. Several royal families had themselves variolated by English physicians claiming to be specialists. Recipients include the family of Louis XV

Louis XV (15 February 1710 – 10 May 1774), known as Louis the Beloved (), was King of France from 1 September 1715 until his death in 1774. He succeeded his great-grandfather Louis XIV at the age of five. Until he reached maturity (then defi ...

following his own death of smallpox, and Catherine the Great

Catherine II. (born Princess Sophie of Anhalt-Zerbst; 2 May 172917 November 1796), most commonly known as Catherine the Great, was the reigning empress of Russia from 1762 to 1796. She came to power after overthrowing her husband, Peter I ...

, whose husband had been horribly disfigured by the disease. Catherine the Great was variolated by Thomas Dimsdale, who followed Sutton's method of inoculation.

In France, the practice was sanctioned until an epidemic was traced back to an inoculation

Inoculation is the act of implanting a pathogen or other microbe or virus into a person or other organism. It is a method of artificially inducing immunity against various infectious diseases. The term "inoculation" is also used more generally ...

. After this instance, variolation was banned within city limits. These conditions caused physicians to move just outside the cities and continue to practice variolation in the suburbs.

=Edward Jenner

=

Edward Jenner

Edward Jenner (17 May 1749 – 26 January 1823) was an English physician and scientist who pioneered the concept of vaccines and created the smallpox vaccine, the world's first vaccine. The terms ''vaccine'' and ''vaccination'' are derived f ...

was variolated in 1756 at age eight in an inoculation barn in Wotton-under-Edge

Wotton-under-Edge is a market town and civil parish in the Stroud district of Gloucestershire, England. Near the southern fringe of the Cotswolds

The Cotswolds ( ) is a region of central South West England, along a range of rolling hills ...

, England. At this time, in preparation for variolation children were bled repeatedly and were given very little to eat and only given a diet drink made to sweeten their blood. This greatly weakened the children before the actual procedure was given. Jenner's own inoculation was administered by a Mr. Holbrow, an apothecary. The procedure involved scratching the arm with the tip of a knife, placing several smallpox

Smallpox was an infectious disease caused by Variola virus (often called Smallpox virus), which belongs to the genus '' Orthopoxvirus''. The last naturally occurring case was diagnosed in October 1977, and the World Health Organization (W ...

scabs in the cuts and then bandaging the arm. After receiving the procedure, the children stayed in the barn for several weeks to recover. First symptoms occurred after one week and usually cleared up three days later. On average, it took a month to fully recover from the encounter with smallpox combined with weakness from the preceding starvation.

At the age of thirteen, Jenner was sent to study medicine in Chipping Sodbury

Chipping Sodbury is a market town and civil parish in the unitary authority area of South Gloucestershire, in the county of Gloucestershire, England. It is situated 13 miles (21 km) north-east of Bristol and directly east of Yate. The town ...

with Daniel Ludlow, a surgeon and apothecary, from 1762 to 1770The UCLA Louise M. Darling Biomedical Library History and Special Collections Division. "Smallpox: an online exhibit". Accessed October 29, 2012. Unitproj.library.ucla.edu/biomed/his/smallpox/jenner.html who had a strong sense of cleanliness which Jenner learned from him. During his apprenticeship, Jenner heard that upon contracting cowpox

Cowpox is an infectious disease caused by Cowpox virus (CPXV). It presents with large blisters in the skin, a fever and swollen glands, historically typically following contact with an infected cow, though in the last several decades more often ...

, the recipient became immune to smallpox for the remainder of their life. However, this theory was dismissed because of several cases proving that the opposite was true.

After learning all he could from Ludlow, Jenner apprenticed with John Hunter in London from 1770 to 1773. Hunter was a correspondent of Ludlow's, and it is likely that Ludlow recommended Jenner to apprentice with Hunter. Hunter believed in deviating from the accepted treatment and trying new methods if the traditional methods failed. This was considered unconventional medicine at the time and had a pivotal role in Jenner's development as a scientist.