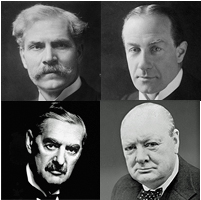

Sir Kingsley Wood on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Sir Howard Kingsley Wood (19 August 1881 – 21 September 1943) was a British

As minister in charge of the

As minister in charge of the  When

When

Conservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy and ideology that seeks to promote and preserve traditional institutions, customs, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civiliza ...

politician. The son of a Wesleyan Methodist The Wesleyan Church is a Methodist Christian denomination aligned with the holiness movement.

Wesleyan Church may also refer to:

* Wesleyan Methodist Church of Australia, the Australian branch of the Wesleyan Church

Denominations

* Allegheny We ...

minister, he qualified as a solicitor, and successfully specialised in industrial insurance. He became a member of the London County Council

The London County Council (LCC) was the principal local government body for the County of London throughout its existence from 1889 to 1965, and the first London-wide general municipal authority to be directly elected. It covered the area today ...

and then a Member of Parliament.

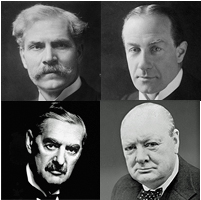

Wood served as junior minister to Neville Chamberlain

Arthur Neville Chamberlain (; 18 March 18699 November 1940) was a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from May 1937 to May 1940 and Leader of the Conservative Party (UK), Leader of the Conservative Party from ...

at the Ministry of Health, establishing a close personal and political alliance. His first cabinet post was Postmaster General

A Postmaster General, in Anglosphere countries, is the chief executive officer of the postal service of that country, a ministerial office responsible for overseeing all other postmasters.

History

The practice of having a government official ...

, in which he transformed the British Post Office

A post office is a public facility and a retailer that provides mail services, such as accepting letter (message), letters and parcel (package), parcels, providing post office boxes, and selling postage stamps, packaging, and stationery. Post o ...

from a bureaucracy to a business. As Secretary of State for Air

The Secretary of State for Air was a secretary of state position in the British government that existed from 1919 to 1964. The person holding this position was in charge of the Air Ministry. The Secretary of State for Air was supported by ...

in the months before the Second World War he oversaw a huge increase in the production of warplanes to bring Britain up to parity with Germany. When Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 1874 – 24 January 1965) was a British statesman, military officer, and writer who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1940 to 1945 (Winston Churchill in the Second World War, ...

became Prime Minister in 1940, Wood was made Chancellor of the Exchequer

The chancellor of the exchequer, often abbreviated to chancellor, is a senior minister of the Crown within the Government of the United Kingdom, and the head of HM Treasury, His Majesty's Treasury. As one of the four Great Offices of State, t ...

, in which post he adopted policies propounded by John Maynard Keynes

John Maynard Keynes, 1st Baron Keynes ( ; 5 June 1883 – 21 April 1946), was an English economist and philosopher whose ideas fundamentally changed the theory and practice of macroeconomics and the economic policies of governments. Originall ...

, changing the role of HM Treasury

His Majesty's Treasury (HM Treasury or HMT), and informally referred to as the Treasury, is the Government of the United Kingdom’s economic and finance ministry. The Treasury is responsible for public spending, financial services policy, Tax ...

from custodian of government income and expenditure to steering the entire British economy.

One of Wood's last innovations was the creation of Pay As You Earn, under which income tax is deducted from employees' current pay, rather than being collected retrospectively. This system remains in force in Britain. Wood died suddenly on the day on which the new system was to be announced to Parliament.

Early years

Wood was born inHull

Hull may refer to:

Structures

* The hull of an armored fighting vehicle, housing the chassis

* Fuselage, of an aircraft

* Hull (botany), the outer covering of seeds

* Hull (watercraft), the body or frame of a sea-going craft

* Submarine hull

Ma ...

, eldest of three children of the Rev. Arthur Wood, a Wesleyan Methodist The Wesleyan Church is a Methodist Christian denomination aligned with the holiness movement.

Wesleyan Church may also refer to:

* Wesleyan Methodist Church of Australia, the Australian branch of the Wesleyan Church

Denominations

* Allegheny We ...

minister, and his wife, Harriett Siddons, ''née'' Howard. His father was appointed to be minister of Wesley's Chapel

Wesley's Chapel (originally the City Road Chapel) is a Methodist Church of Great Britain, Methodist church situated in the St Luke's, London, St Luke's area in the south of the London Borough of Islington. Opened in 1778, it was built under the ...

in London, where Wood grew up, attending nearby Central Foundation Boys' School

Central Foundation Boys' School is a voluntary aided school, voluntary-aided comprehensive secondary school in the London Borough of Islington. It was founded at a meeting in 1865 and opened the following year in Bath Street, before moving to it ...

.Jenkins, p. 394 He was articled

Apprenticeship is a system for training a potential new practitioners of a trade or profession with on-the-job training and often some accompanying study. Apprenticeships may also enable practitioners to gain a license to practice in a regulate ...

to a solicitor

A solicitor is a lawyer who traditionally deals with most of the legal matters in some jurisdictions. A person must have legally defined qualifications, which vary from one jurisdiction to another, to be described as a solicitor and enabled to p ...

, qualifying in 1903 with honours in his law examinations.

In 1905 Wood married Agnes Lilian Fawcett (d. 1955); there were no biological children of the marriage, but the couple adopted a daughter. Wood established his own law firm in the City of London

The City of London, also known as ''the City'', is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county and Districts of England, local government district with City status in the United Kingdom, city status in England. It is the Old town, his ...

, specialising in industrial insurance law. He represented the industrial insurance companies in their negotiations with the Liberal

Liberal or liberalism may refer to:

Politics

* Generally, a supporter of the political philosophy liberalism. Liberals may be politically left or right but tend to be centrist.

* An adherent of a Liberal Party (See also Liberal parties by country ...

government before the introduction of Lloyd George

David Lloyd George, 1st Earl Lloyd-George of Dwyfor (17 January 1863 – 26 March 1945) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1916 to 1922. A Liberal Party (United Kingdom), Liberal Party politician from Wales, he was known for leadi ...

's National Insurance Bill in 1911, gaining valuable concessions for his clients.

Wood was first elected to office as a member of the London County Council

The London County Council (LCC) was the principal local government body for the County of London throughout its existence from 1889 to 1965, and the first London-wide general municipal authority to be directly elected. It covered the area today ...

(LCC) at a by-election on 22 November 1911, representing the Borough of Woolwich for the Municipal Reform Party

The Municipal Reform Party was a local party allied to the parliamentary Conservative Party in the County of London. The party contested elections to both the London County Council and metropolitan borough councils of the county from 1906 to 194 ...

. His importance in the field of insurance grew over the next few years; his biographer Roy Jenkins

Roy Harris Jenkins, Baron Jenkins of Hillhead (11 November 1920 – 5 January 2003) was a British politician and writer who served as the sixth President of the European Commission from 1977 to 1981. At various times a Member of Parliamen ...

has called him "the legal panjandrum of industrial insurance". He chaired the London Old Age Pension Authority in 1915 and the London Insurance Committee from 1917 to 1918, was a member of the National Insurance Advisory Committee from 1911 to 1919, chairman of the Faculty of Insurance from 1916 to 1919 and president of the faculty in 1920, 1922 and 1923. At the LCC he was a member of the council committees on insurance

Insurance is a means of protection from financial loss in which, in exchange for a fee, a party agrees to compensate another party in the event of a certain loss, damage, or injury. It is a form of risk management, primarily used to protect ...

, pensions

A pension (; ) is a fund into which amounts are paid regularly during an individual's working career, and from which periodic payments are made to support the person's retirement from work. A pension may be either a "defined benefit plan", wher ...

and housing

Housing refers to a property containing one or more Shelter (building), shelter as a living space. Housing spaces are inhabited either by individuals or a collective group of people. Housing is also referred to as a human need and right to ...

. He was knighted

A knight is a person granted an honorary title of a knighthood by a head of state (including the pope) or representative for service to the monarch, the church, or the country, especially in a military capacity.

The concept of a knighthood ...

in 1918 at the unusually early age of 36. It was not then, as it later became, the practice to state in honours lists the reason for the conferring of an honour, but Jenkins writes that Wood's knighthood was essentially for his work in the insurance field.

Member of Parliament

Wood was elected toParliament

In modern politics and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: Representation (politics), representing the Election#Suffrage, electorate, making laws, and overseeing ...

as a Conservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy and ideology that seeks to promote and preserve traditional institutions, customs, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civiliza ...

in the "khaki election

In Westminster systems of government, a khaki election is any national election which is heavily influenced by wartime or postwar sentiment. In the British general election of 1900, the Conservative Party government of Lord Salisbury was return ...

" of 1918. His constituency, Woolwich West, was marginal

Marginal may refer to:

* Marginal (album), ''Marginal'' (album), the third album of the Belgian rock band Dead Man Ray, released in 2001

* Marginal (manga), ''Marginal'' (manga)

* ''El Marginal'', Argentine TV series

* Marginal seat or marginal c ...

, but he represented it for the rest of his life. Before being elected, he had attracted notice by advocating the establishment of a Ministry of Health; after the election he was appointed Parliamentary Private Secretary (an unpaid assistant to a minister, a traditional first rung on the political ladder) to the first Minister of Health, Christopher Addison

Christopher Addison, 1st Viscount Addison (19 June 1869 – 11 December 1951), was a British medical doctor and politician. A member of the Liberal and Labour parties, he served as Minister of Munitions during the First World War and was late ...

.

After the collapse of the coalition government

A coalition government, or coalition cabinet, is a government by political parties that enter into a power-sharing arrangement of the executive. Coalition governments usually occur when no single party has achieved an absolute majority after an ...

in 1922, Wood was offered no post in the Conservative government Conservative or Tory government may refer to:

Canada

In Canadian politics, a Conservative government may refer to the following governments administered by the Conservative Party of Canada or one of its historical predecessors:

* 1st Canadian Min ...

formed by Bonar Law

Andrew Bonar Law (; 16 September 1858 – 30 October 1923) was a British statesman and politician who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from October 1922 to May 1923.

Law was born in the British colony of New Brunswick (now a Canadi ...

. As a backbencher, Wood successfully introduced the Summer Time Bill of 1924. This measure, passed in the teeth of opposition from the agricultural lobby, provided for a permanent annual summer time

Daylight saving time (DST), also referred to as daylight savings time, daylight time (United States and Canada), or summer time (United Kingdom, European Union, and others), is the practice of advancing clocks to make better use of the long ...

period of six months from the first Sunday in April to the first Sunday in October.

When Baldwin

Baldwin may refer to:

People

* Baldwin (name), including a list of people and fictional characters with the surname

Places Canada

* Baldwin, York Regional Municipality, Ontario

* Baldwin, Ontario, in Sudbury District

* Baldwin's Mills, ...

succeeded Law in 1924, Wood was appointed Parliamentary Secretary to the Ministry of Health The Parliamentary Secretary to the Ministry of Health was a junior ministerial office in the United Kingdom Government.

The Ministry of Health was created in 1919 as a reconstruction of the Local Government Board. Local government functions were ev ...

, as junior minister to Neville Chamberlain

Arthur Neville Chamberlain (; 18 March 18699 November 1940) was a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from May 1937 to May 1940 and Leader of the Conservative Party (UK), Leader of the Conservative Party from ...

. The two served at the Ministry of Health from 11 November 1924 to 4 June 1929, becoming friends and firm political allies. They worked closely together on local government reform, including a radical updating of local taxation, the "rates

Rate or rates may refer to:

Finance

* Rate (company), an American residential mortgage company formerly known as Guaranteed Rate

* Rates (tax), a type of taxation system in the United Kingdom used to fund local government

* Exchange rate, rate ...

", based on property values. Wood's political standing was marked by his appointment as a civil commissioner during the general strike

A general strike is a strike action in which participants cease all economic activity, such as working, to strengthen the bargaining position of a trade union or achieve a common social or political goal. They are organised by large coalitions ...

of 1926, and, unusually for a junior minister, as a privy councillor in 1928.Jenkins, p. 395 In 1930 he was elected as the first chairman of the executive committee of the National Union of Conservative and Unionist Associations

The National Conservative Convention (NCC), is the most senior body of the Conservative Party's voluntary wing. The National Convention effectively serves as the Party's internal Parliament, and is made up of its 800 highest-ranking Party Office ...

.

When the National Government was formed by Ramsay MacDonald

James Ramsay MacDonald (; 12 October 18669 November 1937) was a British statesman and politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom. The first two of his governments belonged to the Labour Party (UK), Labour Party, where he led ...

in 1931, Wood was made Parliamentary Secretary to the Board of Education

The Parliamentary Secretary to the Board of Education was a junior ministerial office in the United Kingdom Government. The Board of Education Act 1899 abolished the Committee of the Privy Council which had been responsible for education matters ...

. After the general election of November 1931 he was promoted to the office of Postmaster General

A Postmaster General, in Anglosphere countries, is the chief executive officer of the postal service of that country, a ministerial office responsible for overseeing all other postmasters.

History

The practice of having a government official ...

. The position did not entail automatic membership of the cabinet, but Wood was made a cabinet member in 1933.

Ministerial service

As minister in charge of the

As minister in charge of the General Post Office

The General Post Office (GPO) was the state postal system and telecommunications carrier of the United Kingdom until 1969. Established in England in the 17th century, the GPO was a state monopoly covering the dispatch of items from a specific ...

(GPO), Wood inherited an old-fashioned organisation, not equipped to meet the needs of the 1930s. In particular its management of the national telephone system, a GPO monopoly, was widely criticised. Wood considered reconstituting the whole of the GPO, changing it from a government department to what would later be called a quango, and he set up an independent committee to advise him on this. The committee recommended that the GPO should remain a department of state, but adopt a more commercial approach.

Under Wood the GPO introduced reply paid arrangements for businesses, and set up a national teleprinter

A teleprinter (teletypewriter, teletype or TTY) is an electromechanical device that can be used to send and receive typed messages through various communications channels, in both point-to-point (telecommunications), point-to-point and point- ...

service. For the telephone service, still mostly dependent on manual operators, the GPO introduced a programme of building new automated exchanges. For the postal service, the GPO built up a large fleet of motor vehicles to speed delivery, with 3,000 vans and 1,200 motor-cycles. Wood was a strong believer in publicity; he set up an advertising campaign for the telephone system which dramatically increased the number of subscribers, and he established the GPO Film Unit

The GPO Film Unit was a subdivision of the UK General Post Office. The unit was established in 1933, taking on responsibilities of the Empire Marketing Board Film Unit. Headed by John Grierson, it was set up to produce sponsored documentary film ...

which gained a high aesthetic reputation as well as raising the GPO's profile.Jenkins, p. 396 Most importantly, Wood transformed the senior management of the GPO and negotiated a practical financial deal with HM Treasury

His Majesty's Treasury (HM Treasury or HMT), and informally referred to as the Treasury, is the Government of the United Kingdom’s economic and finance ministry. The Treasury is responsible for public spending, financial services policy, Tax ...

. The civil service post of Secretary to the Post Office was replaced by a director general with an expert board of management. The old financial rules, by which all the GPO's surplus revenue was surrendered to the Treasury had long prevented reinvestment in the business; Wood negotiated a new arrangement under which the GPO would pay an agreed annual sum to the Treasury and keep the remainder of its revenue for investment.

When MacDonald was succeeded as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom

The prime minister of the United Kingdom is the head of government of the United Kingdom. The prime minister Advice (constitutional law), advises the Monarchy of the United Kingdom, sovereign on the exercise of much of the Royal prerogative ...

by Baldwin in 1935, Wood was appointed Minister of Health

A health minister is the member of a country's government typically responsible for protecting and promoting public health and providing welfare spending and other social security services.

Some governments have separate ministers for mental heal ...

. Despite its title, the Ministry was at that time at least as concerned with housing as with health. Under Wood, his biographer G. C. Peden

George C. Peden (born 1943) is an emeritus professor of history at Stirling University, Scotland.

Career

Peden was born in Dundee and educated at Grove Academy, Broughty Ferry.

He has written about the British Treasury; Keynesian economics; ...

writes, "the slum clearance

Slum clearance, slum eviction or slum removal is an urban renewal strategy used to transform low-income settlements with poor reputation into another type of development or housing. This has long been a strategy for redeveloping urban communities; ...

programme was pursued with energy, and overcrowding was greatly reduced. There was also a marked improvement in maternal mortality, mainly due to the discovery of antibiotics

An antibiotic is a type of antimicrobial substance active against bacteria. It is the most important type of antibacterial agent for fighting pathogenic bacteria, bacterial infections, and antibiotic medications are widely used in the therapy ...

able to counteract septicaemia

Sepsis is a potentially life-threatening condition that arises when the body's response to infection causes injury to its own tissues and organs.

This initial stage of sepsis is followed by suppression of the immune system. Common signs and s ...

, but also because a full-time, salaried midwifery service was created under the Midwives Act of 1936." Jenkins comments that the housing boom of the 1930s was one of the two main contributors to such economic recovery as there was after the Great Depression

The Great Depression was a severe global economic downturn from 1929 to 1939. The period was characterized by high rates of unemployment and poverty, drastic reductions in industrial production and international trade, and widespread bank and ...

.

When

When Anthony Eden

Robert Anthony Eden, 1st Earl of Avon (12 June 1897 – 14 January 1977) was a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom and Leader of the Conservative Party from 1955 until his resignation in 1957.

Achi ...

resigned from Chamberlain's government in March 1938, Wood moved to be Secretary of State for Air

The Secretary of State for Air was a secretary of state position in the British government that existed from 1919 to 1964. The person holding this position was in charge of the Air Ministry. The Secretary of State for Air was supported by ...

in the ensuing reshuffle. The UK was then producing 80 new warplanes a month. Within two years under Wood the figure had risen to 546 a month. By the outbreak of the Second World War, Britain was producing as many new warplanes as Germany. Wood's tenure as Secretary of State for Air coincided with the Phoney War

The Phoney War (; ; ) was an eight-month period at the outset of World War II during which there were virtually no Allied military land operations on the Western Front from roughly September 1939 to May 1940. World War II began on 3 Septembe ...

, and during this time he limited RAF activity to dropping propaganda leaflets rather than strategic bombing

Strategic bombing is a systematically organized and executed military attack from the air which can utilize strategic bombers, long- or medium-range missiles, or nuclear-armed fighter-bomber aircraft to attack targets deemed vital to the enemy' ...

. When Leo Amery

Leopold Charles Maurice Stennett Amery (22 November 1873 – 16 September 1955), also known as L. S. Amery, was a British Conservative Party (UK), Conservative Party politician and journalist. During his career, he was known for his interest in ...

urged him to destroy the Black Forest

The Black Forest ( ) is a large forested mountain range in the States of Germany, state of Baden-Württemberg in southwest Germany, bounded by the Rhine Valley to the west and south and close to the borders with France and Switzerland. It is th ...

with incendiary bombs in reaction to the invasion of Poland

The invasion of Poland, also known as the September Campaign, Polish Campaign, and Polish Defensive War of 1939 (1 September – 6 October 1939), was a joint attack on the Second Polish Republic, Republic of Poland by Nazi Germany, the Slovak R ...

, he is said to have replied "Are you aware it is private property

Private property is a legal designation for the ownership of property by non-governmental Capacity (law), legal entities. Private property is distinguishable from public property, which is owned by a state entity, and from Collective ownership ...

?... Why, you will be asking me bomb Essen

Essen () is the central and, after Dortmund, second-largest city of the Ruhr, the largest urban area in Germany. Its population of makes it the fourth-largest city of North Rhine-Westphalia after Cologne, Düsseldorf and Dortmund, as well as ...

next!" By early 1940, Wood was worn out by his efforts, and Chamberlain moved him to the non-departmental office of Lord Privy Seal

The Lord Privy Seal (or, more formally, the Lord Keeper of the Privy Seal) is the fifth of the Great Officers of State (United Kingdom), Great Officers of State in the United Kingdom, ranking beneath the Lord President of the Council and abov ...

, switching the incumbent, Sir Samuel Hoare, to the Air Ministry in Wood's place. Wood's job was to chair both the Home Policy Committee of the cabinet, which considered "all social service and other domestic questions and reviews proposals for legislation" and the Food Policy Committee, overseeing "the problems of food policy

Food policy is the area of public policy concerning how food is produced, processed, distributed, purchased, or provided. Food policies are designed to influence the operation of the food and agriculture system balanced with ensuring human health ...

and home agriculture". He held this position for only a few weeks; the downfall of Chamberlain affected Wood in an unexpected way.

In May 1940, as a trusted friend, Wood told Chamberlain "affectionately but firmly" that after the debacle of the British defeat in Norway and the ensuing Commons debate, his position as Prime Minister was impossible and he must resign.Jenkins, p. 587 He also advised Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 1874 – 24 January 1965) was a British statesman, military officer, and writer who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1940 to 1945 (Winston Churchill in the Second World War, ...

to ignore pressure from those who wanted Lord Halifax

Edward Frederick Lindley Wood, 1st Earl of Halifax (16 April 1881 – 23 December 1959), known as the Lord Irwin from 1925 until 1934 and the Viscount Halifax from 1934 until 1944, was a British Conservative politician of the 1930s. He h ...

, not Churchill, as Chamberlain's successor. Chamberlain agreed to resign on 9 May, but considered going back on his decision the next day as the German attack on the Western Front had begun; Wood told him that he had to go through with his resignation.Jenkins, p. 587 Both men acted on Wood's advice. Churchill became Prime Minister on 10 May 1940; Wood was appointed Chancellor of the Exchequer

The chancellor of the exchequer, often abbreviated to chancellor, is a senior minister of the Crown within the Government of the United Kingdom, and the head of HM Treasury, His Majesty's Treasury. As one of the four Great Offices of State, t ...

on 12 May.

Chancellorship of the Exchequer and death

One of the reasons for Wood's appointment to the Treasury seems to have been Churchill's urgent desire to be rid of the incumbentChancellor of the Exchequer

The chancellor of the exchequer, often abbreviated to chancellor, is a senior minister of the Crown within the Government of the United Kingdom, and the head of HM Treasury, His Majesty's Treasury. As one of the four Great Offices of State, t ...

, Sir John Simon

John Allsebrook Simon, 1st Viscount Simon, (28 February 1873 – 11 January 1954) was a British politician who held senior Cabinet posts from the beginning of the First World War to the end of the Second World War. He is one of three people to ...

, whom Churchill detested. Another may have been Wood's record of working well with politicians from other parties. In peacetime, the Chancellor of the Exchequer is often the most important member of the cabinet after the Prime Minister, but the exigencies of the war reduced the Chancellor's precedence. The Treasury temporarily ceased to be the core department of government. In Peden's words, "Non-military aspects of policy, including economic policy

''Economic Policy'' is a quarterly peer-reviewed academic journal published by Oxford University Press, Oxford Academic on behalf of the Centre for Economic Policy Research, the Center for Economic Studies (University of Munich), and the Paris Scho ...

, were co-ordinated by a cabinet committee … The Treasury's main jobs were to finance the war with as little inflation

In economics, inflation is an increase in the average price of goods and services in terms of money. This increase is measured using a price index, typically a consumer price index (CPI). When the general price level rises, each unit of curre ...

as possible, to conduct external financial policy so as to secure overseas supplies on the best possible terms, and to take part in planning for the post-war period."

Wood was Chancellor, as Jenkins notes, "for the forty key months of the Second World War". He presented four budgets to Parliament

In modern politics and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: Representation (politics), representing the Election#Suffrage, electorate, making laws, and overseeing ...

. His first, in July 1940, passed with little notice, and brought into effect some minor changes planned by his predecessor. Of more long-lasting impact was his creation in the same month of a council of economic advisers, the most notable of whom, John Maynard Keynes

John Maynard Keynes, 1st Baron Keynes ( ; 5 June 1883 – 21 April 1946), was an English economist and philosopher whose ideas fundamentally changed the theory and practice of macroeconomics and the economic policies of governments. Originall ...

, was quickly recruited as a full-time adviser at the Treasury. Jenkins detects Keynes's influence in Wood's second budget, in April 1941.Jenkins, p. 399 It brought in a top income tax rate of 19s 6d (97½ pence in decimal currency

Decimalisation or decimalization (see spelling differences) is the conversion of a system of currency or of weights and measures to units related by powers of 10.

Most countries have decimalised their currencies, converting them from non-decimal ...

) and added two million to the number of income tax payers; for the first time in Britain's history the majority of the population was liable to income tax

An income tax is a tax imposed on individuals or entities (taxpayers) in respect of the income or profits earned by them (commonly called taxable income). Income tax generally is computed as the product of a tax rate times the taxable income. Tax ...

. Keynes convinced Wood that he should abandon the orthodox Treasury doctrine that Chancellors' budgets were purely to regulate governmental revenue and expenditure; Wood, despite some misgivings on Churchill's part, adopted Keynes's conception of using national income accounting to control the economy.

With the hugely increased public expenditure necessitated by the war – it increased sixfold between 1938 and 1943 – inflation was always a danger. Wood sought to head off inflationary wage claims by subsidising essential rationed goods, while imposing heavy taxes on goods classed as non-essential. The last change he pioneered as Chancellor was the system of Pay As You Earn (PAYE), by which income tax is deducted from current pay rather than paid retrospectively on past years' earnings. He did not live to see it come into effect; he died suddenly at his London home on the morning of the day on which he was due to announce PAYE in the House of Commons.Jenkins, p. 400 He was 62.

Wood was referred to in the book ''Guilty Men

''Guilty Men'' is a British polemical book written under the pseudonym "Cato" that was published in July 1940, after the failure of British forces to prevent the defeat and occupation of Norway and France by Nazi Germany. It attacked fifteen publ ...

'' by Michael Foot

Michael Mackintosh Foot (23 July 19133 March 2010) was a British politician who was Leader of the Labour Party (UK), Leader of the Labour Party and Leader of the Opposition (United Kingdom), Leader of the Opposition from 1980 to 1983. Foot beg ...

, Frank Owen and Peter Howard (writing under the pseudonym "Cato"), published in 1940 as an attack on public figures for their failure to re-arm and their appeasement

Appeasement, in an International relations, international context, is a diplomacy, diplomatic negotiation policy of making political, material, or territorial concessions to an aggressive power (international relations), power with intention t ...

of Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany, officially known as the German Reich and later the Greater German Reich, was the German Reich, German state between 1933 and 1945, when Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party controlled the country, transforming it into a Totalit ...

.

Notes

References

* * *External links

* * {{DEFAULTSORT:Wood, Kingsley 1881 births 1943 deaths Secretaries of State for Air (UK) Chancellors of the Exchequer of the United Kingdom Conservative Party (UK) MPs for English constituencies English Methodists Knights Bachelor Lords Privy Seal Members of London County Council Members of the Privy Council of the United Kingdom Ministers in the Churchill wartime government, 1940–1945 People educated at Central Foundation Boys' School Politicians from Kingston upon Hull UK MPs 1918–1922 UK MPs 1922–1923 UK MPs 1923–1924 UK MPs 1924–1929 UK MPs 1929–1931 UK MPs 1931–1935 UK MPs 1935–1945 Postmasters general of the United Kingdom Ministers in the Chamberlain wartime government, 1939–1940 Ministers in the Chamberlain peacetime government, 1937–1939