Sir Henry Irving on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

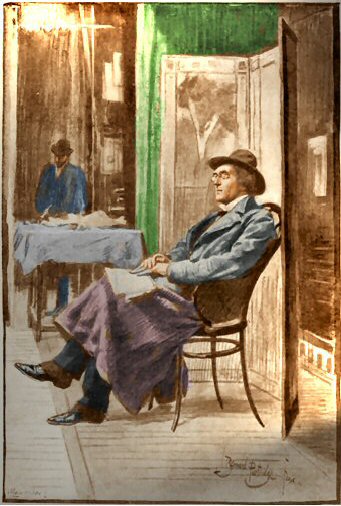

Sir Henry Irving (6 February 1838 – 13 October 1905), christened John Henry Brodribb, sometimes known as J. H. Irving, was an English stage actor in the

His elder son, Harry Brodribb Irving (1870–1919), usually known as "H B Irving", became a famous actor and later a theatre manager. His younger son, Laurence Irving (1871–1914), became a

His elder son, Harry Brodribb Irving (1870–1919), usually known as "H B Irving", became a famous actor and later a theatre manager. His younger son, Laurence Irving (1871–1914), became a

After a few years schooling, while living at Halsetown, near

After a few years schooling, while living at Halsetown, near

After the production of Tennyson's ''The Cup'' and revivals of ''Othello'' (in which Irving played

After the production of Tennyson's ''The Cup'' and revivals of ''Othello'' (in which Irving played

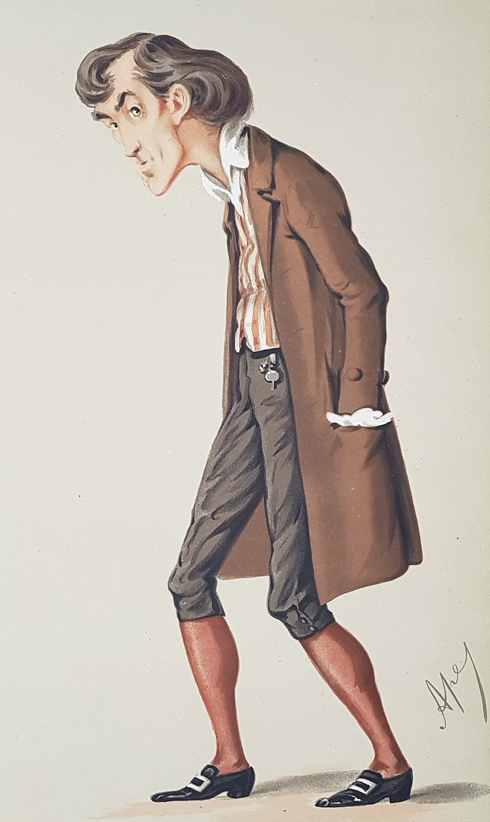

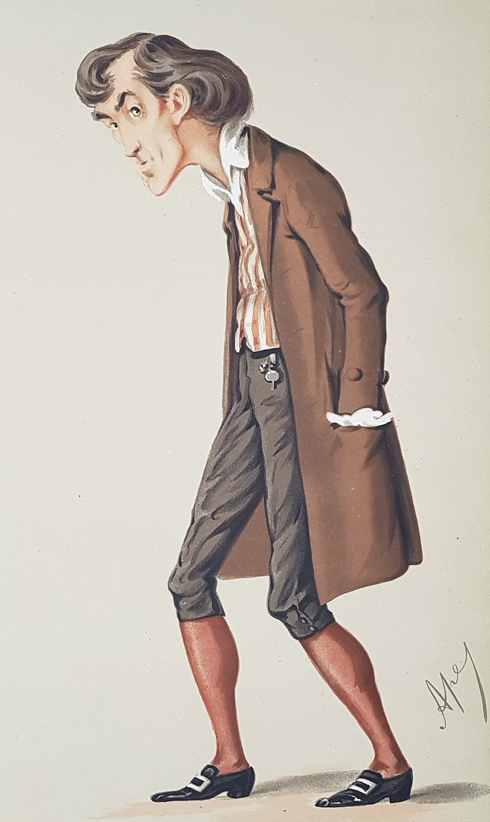

His acting divided critics; opinions differed as to the extent to which his mannerisms of voice and deportment interfered with or assisted the expression of his ideas. Irving's idiosyncratic style of acting and its effect on amateur players were mildly satirised in ''

His acting divided critics; opinions differed as to the extent to which his mannerisms of voice and deportment interfered with or assisted the expression of his ideas. Irving's idiosyncratic style of acting and its effect on amateur players were mildly satirised in ''

He has acted with Irving, he's acted with"Ralph Fiennes / Theatre Royal Bath season announced for 2025 including new David Hare play ''Grace Pervades'' & ''As You Like It'' starring Gloria Obianyo & Harriet Walter"

West End Theatre, 26 March 2024

''Personal Reminiscences of Henry Irving: Volume 1''

an

''Volume 2''

London : W. Heinemann, 1906. Scanned books via

Henry Irving, Actor and Manager: A Critical Study

London:Field & Tuer. * Beerbohm, Max. 1928. 'Henry Irving' in ''A Variety of Things.'' New York, Knopf. *Holroyd, Michael. 2008. ''A Strange Eventful History'', Farrar Straus Giroux, *Irving, Laurence. 1989. ''Henry Irving: The Actor and His World''. Lively Arts. * *

The Irving SocietyThe Henry Irving FoundationInformation about Irving at the PeoplePlay UK websiteNY Times article that includes information about Irving's American tour and the lease of the Lyceum to the American company at the same timeMy First "Reading" by Henry Irving, an article written by Irving about a personal experienceHenry Irving ''North American Theatre Online''

with bio and pics

Henry Irving-Ellen Terry tour correspondence, 1884-1896

held by the Billy Rose Theatre Division,

Irving Disher Collection

Rare Books, Special Collections, and Preservation, River Campus Libraries,

Victorian era

In the history of the United Kingdom and the British Empire, the Victorian era was the reign of Queen Victoria, from 20 June 1837 until her death on 22 January 1901. Slightly different definitions are sometimes used. The era followed the ...

, known as an actor-manager because he took complete responsibility (supervision of sets, lighting, direction, casting, as well as playing the leading roles) for season after season at the West End's Lyceum Theatre, establishing himself and his company as representative of English classical theatre. In 1895 he became the first actor to be awarded a knighthood, indicating full acceptance into the higher circles of British society.

Life and career

Irving was born to aworking-class

The working class is a subset of employees who are compensated with wage or salary-based contracts, whose exact membership varies from definition to definition. Members of the working class rely primarily upon earnings from wage labour. Most c ...

family in Keinton Mandeville

Keinton Mandeville, commonly referred to as Keinton, is a village and civil parish in Somerset, England, situated on top of Combe Hill, west of Castle Cary. The village has a population of 1,215. It is located next to Barton St David.

The villa ...

in the county of Somerset

Somerset ( , ), Archaism, archaically Somersetshire ( , , ) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South West England. It is bordered by the Bristol Channel, Gloucestershire, and Bristol to the north, Wiltshire to the east ...

. W.H. Davies, the poet, was a cousin. Irving spent his childhood living with his aunt, Mrs Penberthy, at Halsetown in Cornwall

Cornwall (; or ) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South West England. It is also one of the Celtic nations and the homeland of the Cornish people. The county is bordered by the Atlantic Ocean to the north and west, ...

. He competed in a recitation contest at a local Methodist

Methodism, also called the Methodist movement, is a Protestant Christianity, Christian Christian tradition, tradition whose origins, doctrine and practice derive from the life and teachings of John Wesley. George Whitefield and John's brother ...

chapel where he was beaten by William Curnow, later the editor of ''The Sydney Morning Herald

''The Sydney Morning Herald'' (''SMH'') is a daily Tabloid (newspaper format), tabloid newspaper published in Sydney, Australia, and owned by Nine Entertainment. Founded in 1831 as the ''Sydney Herald'', the ''Herald'' is the oldest continuous ...

''. He attended City Commercial School for two years before going to work in the office of a law firm at age 13. When he saw Samuel Phelps play Hamlet

''The Tragedy of Hamlet, Prince of Denmark'', often shortened to ''Hamlet'' (), is a Shakespearean tragedy, tragedy written by William Shakespeare sometime between 1599 and 1601. It is Shakespeare's longest play. Set in Denmark, the play (the ...

soon after this, he sought lessons, letters of introduction, and work in the Lyceum Theatre in Sunderland

Sunderland () is a port City status in the United Kingdom, city and metropolitan borough in Tyne and Wear, England. It is a port at the mouth of the River Wear on the North Sea, approximately south-east of Newcastle upon Tyne. It is the most p ...

in 1856, labouring against great odds until his 1871 success in '' The Bells'' in London

London is the Capital city, capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of both England and the United Kingdom, with a population of in . London metropolitan area, Its wider metropolitan area is the largest in Wester ...

set him apart from all the rest.

He married Florence O'Callaghan on 15 July 1869 at St. Marylebone, London, but his personal life took second place to his professional life. On the opening night of ''The Bells'', 25 November 1871, Florence, who was pregnant with their second child, criticised his profession: "Are you going on making a fool of yourself like this all your life?" Irving exited their carriage at Hyde Park Corner, walked off into the night, and chose never to see her again. He maintained a discreet distance from his children as well but became closer to them as they grew older. Florence Irving never divorced Irving, and once he had been knighted she styled herself "Lady Irving"; Irving never remarried.

His elder son, Harry Brodribb Irving (1870–1919), usually known as "H B Irving", became a famous actor and later a theatre manager. His younger son, Laurence Irving (1871–1914), became a

His elder son, Harry Brodribb Irving (1870–1919), usually known as "H B Irving", became a famous actor and later a theatre manager. His younger son, Laurence Irving (1871–1914), became a dramatist

A playwright or dramatist is a person who writes plays, which are a form of drama that primarily consists of dialogue between characters and is intended for theatrical performance rather than just

reading. Ben Jonson coined the term "playwri ...

and later drowned, with his wife Mabel Hackney, in the sinking of the '' Empress of Ireland''. H B married Dorothea Baird and they had a son, Laurence Irving (1897–1988), who became a well-known Hollywood

Hollywood usually refers to:

* Hollywood, Los Angeles, a neighborhood in California

* Hollywood, a metonym for the cinema of the United States

Hollywood may also refer to:

Places United States

* Hollywood District (disambiguation)

* Hollywood ...

art director and his grandfather's biographer, and a daughter, Elizabeth Irving (1904 – 2003) an actress and the founder of Keep Britain Tidy.

In November 1882 Irving became a Freemason

Freemasonry (sometimes spelled Free-Masonry) consists of fraternal groups that trace their origins to the medieval guilds of stonemasons. Freemasonry is the oldest secular fraternity in the world and among the oldest still-existing organizati ...

, being initiated into the prestigious Jerusalem Lodge No 197 in London. In 1887 he became a founder member and first Treasurer of the Savage Club Lodge No 2190, a Lodge associated with London's Savage Club.

He eventually took over the management of the Lyceum Theatre and brought actress Ellen Terry into partnership with him as Ophelia

Ophelia () is a character in William Shakespeare's drama ''Hamlet'' (1599–1601). She is a young noblewoman of Denmark, the daughter of Polonius, sister of Laertes and potential wife of Prince Hamlet. Due to Hamlet's actions, Ophelia ultima ...

to his Hamlet, Lady Macbeth to his Macbeth

''The Tragedy of Macbeth'', often shortened to ''Macbeth'' (), is a tragedy by William Shakespeare, estimated to have been first performed in 1606. It dramatises the physically violent and damaging psychological effects of political ambiti ...

, Portia to his Shylock, Beatrice to his Benedick, etc. Before joining the Lyceum, Terry had fled her first marriage and conceived two out-of-wedlock children with architect-designer Edward William Godwin, but regardless of how much and how often her behavior defied the strict morality expected by her Victorian audiences, she somehow remained popular. It could be said that Irving found his family in his professional company, which included his ardent supporter and manager Bram Stoker

Abraham Stoker (8 November 1847 – 20 April 1912), better known by his pen name Bram Stoker, was an Irish novelist who wrote the 1897 Gothic horror novel ''Dracula''. The book is widely considered a milestone in Vampire fiction, and one of t ...

and Terry's two illegitimate children, Teddy and Edy.

Whether Irving's long, spectacularly successful relationship with leading lady Ellen Terry was romantic as well as professional has been the subject of much historical speculation. Most of their correspondence was lost or burned by her descendants. According to Michael Holroyd's book about Irving and Terry, ''A Strange Eventful History'':

Terry's son Teddy, later known as Edward Gordon Craig, spent much of his childhood (from 1879, when he was 8, until 1897) indulged by Irving backstage at the Lyceum. Craig, who came to be regarded as something of a visionary for the theatre of the future, wrote an especially vivid, book-length tribute to Irving. ("Let me state at once, in clearest unmistakable terms, that I have never known of, or seen, or heard, a greater actor than was Irving.") George Bernard Shaw

George Bernard Shaw (26 July 1856 – 2 November 1950), known at his insistence as Bernard Shaw, was an Irish playwright, critic, polemicist and political activist. His influence on Western theatre, culture and politics extended from the 188 ...

, at the time a theatre critic who was jealous of Irving's connection to Ellen Terry (whom Shaw himself wanted in his plays), conceded Irving's genius after Irving died.

Early career

After a few years schooling, while living at Halsetown, near

After a few years schooling, while living at Halsetown, near St Ives, Cornwall

St Ives (, meaning "Ia of Cornwall, St Ia's cove") is a seaside town, civil parish and port in Cornwall, England, United Kingdom. The town lies north of Penzance and west of Camborne on the coast of the Celtic Sea. In former times, it was comm ...

, Irving became a clerk to a firm of East India

East India is a region consisting of the Indian states of Bihar, Jharkhand, Odisha

and West Bengal and also the union territory of the Andaman and Nicobar Islands.

The states of Bihar and West Bengal lie on the Indo-Gangetic plain. Jharkhan ...

merchants in London, but he soon gave up a commercial career for acting. On 29 September 1856, he made his first appearance at Sunderland as Gaston, Duke of Orleans, in Bulwer Lytton's play, ''Richelieu'', billed as Henry Irving. This name he eventually assumed by royal license. When the inexperienced Irving got stage fright and was hissed off the stage the actor Samuel Johnson

Samuel Johnson ( – 13 December 1784), often called Dr Johnson, was an English writer who made lasting contributions as a poet, playwright, essayist, moralist, literary critic, sermonist, biographer, editor, and lexicographer. The ''Oxford ...

was among those who supported him with practical advice. Later in life, Irving gave them all regular work when he formed his own Company at the Lyceum Theatre.

For 10 years, he went through arduous training in various stock

Stocks (also capital stock, or sometimes interchangeably, shares) consist of all the Share (finance), shares by which ownership of a corporation or company is divided. A single share of the stock means fractional ownership of the corporatio ...

companies in Scotland

Scotland is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It contains nearly one-third of the United Kingdom's land area, consisting of the northern part of the island of Great Britain and more than 790 adjac ...

and the north of England, taking more than 500 parts.

He gained recognition by degrees, and in 1866 Ruth Herbert engaged him as her leading man and sometime stage director at the St. James's Theatre

The St James's Theatre was in King Street, St James's, King Street, St James's, London. It opened in 1835 and was demolished in 1957. The theatre was conceived by and built for a popular singer, John Braham (tenor), John Braham; it lost mone ...

, London, where she first played Doricourt in ''The Belle's Stratagem''. One piece that he directed there was W. S. Gilbert

Sir William Schwenck Gilbert (18 November 1836 – 29 May 1911) was an English dramatist, librettist, poet and illustrator best known for his collaboration with composer Arthur Sullivan, which produced fourteen comic operas. The most fam ...

's first successful solo play, ''Dulcamara, or the Little Duck and the Great Quack

''Dulcamara, or the Little Duck and the Great Quack'', is one of the earliest plays written by W.S. Gilbert, his first solo stage success. The work is a musical burlesque of Donizetti's ''L'Elisir d'Amore'', and the music was arranged by Mr. Va ...

'' (1866) The next year he joined the company of the newly opened Queen's Theatre, where he acted with Charles Wyndham, J. L. Toole, Lionel Brough, John Clayton John Clayton may refer to:

Arts and entertainment Writing

*John Clayton (architect) (died 1861), English architect and writer

*John Clayton (sportswriter) (1954–2022), American sportswriter and reporter

*John Bell Clayton and Martha Clayton, Joh ...

, Mr. and Mrs. Alfred Wigan

Alfred Sydney Wigan (24 March 1814Some sources say 24 March 1818 – 29 November 1878) was an English actor-manager who took part in the first Royal Command Performance before Queen Victoria on 28 December 1848.Gillan, DonA History of the R ...

, Ellen Terry and Nellie Farren

Ellen "Nellie" Farren (16 April 1848 – 28 April 1904"Death of Nellie Far ...

. This was followed by short engagements at the Haymarket Theatre

The Theatre Royal Haymarket (also known as Haymarket Theatre or the Little Theatre) is a West End theatre in Haymarket, London, Haymarket in the City of Westminster which dates back to 1720, making it the third-oldest London playhouse still in ...

, Drury Lane, and the Gaiety Theatre. In the spring of 1869, Irving was one of the original twelve members of The Lambs of London—assembled by John Hare as a social club for actors—and would be made an Honorary Lifetime member in 1883. He finally made his first conspicuous success as Digby Grant in James Albery

James Albery (4 May 1838 – 15 August 1889) was an English dramatist.

Life and career

Albery was born in London. On leaving school he entered an architect's office and started to write plays. His farce ''A Pretty Piece of Chiselling'' wa ...

's ''Two Roses'', which was produced at the Vaudeville Theatre

The Vaudeville Theatre is a West End theatre on the Strand in the City of Westminster. Opening in 1870, the theatre staged mostly vaudeville shows and musical revues in its early days. The theatre was rebuilt twice, although each new buildin ...

on 4 June 1870 and ran for a very successful 300 nights.

In 1871, Irving began his association with the Lyceum Theatre by an engagement under Bateman's management. The fortunes of the house were at a low ebb when the tide was turned by Irving's sudden success as Mathias in '' The Bells,'' a version of Erckmann-Chatrian

Erckmann-Chatrian was the name used by French authors Émile Erckmann (1822–1899) and Alexandre Chatrian (1826–1890), nearly all of whose works were jointly written.Mary Ellen Snodgrass, ''Encyclopedia of Gothic Literature''. New York, Facts ...

's '' Le Juif polonais'' by Leopold Lewis

Leopold David Lewis (19 November 1828 – 23 February 1890), was an English dramatist.

Lewis was born in London in 1828, the son of Elizabeth and David Leopold Lewis, a surgeon, and was educated at the King's College School, and upon gradua ...

, a property that Irving had found for himself. The play ran for 150 nights, established Irving at the forefront of the British drama, and would prove a popular vehicle for Irving for the rest of his professional life.

With Bateman, Irving was seen in W. G. Wills

William Gorman Wills (28 January 182813 December 1891), usually known as W. G. Wills, was an Irish dramatist, novelist and painter.

Early life and career

Wills was born at Blackwell lodge in Kilmurry, near Thomastown, County Kilkenny, Thomasto ...

' ''Charles I'' and ''Eugene Aram'', in ''Richelieu'', and 1874 in ''Hamlet

''The Tragedy of Hamlet, Prince of Denmark'', often shortened to ''Hamlet'' (), is a Shakespearean tragedy, tragedy written by William Shakespeare sometime between 1599 and 1601. It is Shakespeare's longest play. Set in Denmark, the play (the ...

''. The unconventionality of this last performance, during a run of 200 nights, aroused keen discussion and singled him out as the most interesting English actor of his day. In 1875, again with Bateman, he was seen as the title character in ''Macbeth

''The Tragedy of Macbeth'', often shortened to ''Macbeth'' (), is a tragedy by William Shakespeare, estimated to have been first performed in 1606. It dramatises the physically violent and damaging psychological effects of political ambiti ...

''; in 1876 as Othello

''The Tragedy of Othello, the Moor of Venice'', often shortened to ''Othello'' (), is a tragedy written by William Shakespeare around 1603. Set in Venice and Cyprus, the play depicts the Moorish military commander Othello as he is manipulat ...

, and as Philip in Alfred Lord Tennyson

Alfred Tennyson, 1st Baron Tennyson (; 6 August 1809 – 6 October 1892) was an English poet. He was the Poet Laureate during much of Queen Victoria's reign. In 1829, Tennyson was awarded the Chancellor's Gold Medal at Cambridge for one of ...

's ''Queen Mary''; in 1877 in ''Richard III

Richard III (2 October 1452 – 22 August 1485) was King of England from 26 June 1483 until his death in 1485. He was the last king of the Plantagenet dynasty and its cadet branch the House of York. His defeat and death at the Battle of Boswor ...

''; and ''The Lyons Mail

''The Lyons Mail'' is a 1931 British historical mystery adventure film directed by Arthur Maude and starring John Martin Harvey, Norah Baring, and Ben Webster. It was based on the 1877 play '' The Lyons Mail'' by Charles Reade which in turn was ...

''. During this time he became lifelong friends with Bram Stoker, who praised him in his review of ''Hamlet'' and thereafter joined Irving as the manager of the company.

Peak years

In 1878, Irving entered into a partnership with actress Ellen Terry and re-opened the Lyceum under his management. With Terry as Ophelia and Portia, he revived ''Hamlet

''The Tragedy of Hamlet, Prince of Denmark'', often shortened to ''Hamlet'' (), is a Shakespearean tragedy, tragedy written by William Shakespeare sometime between 1599 and 1601. It is Shakespeare's longest play. Set in Denmark, the play (the ...

'' and produced ''The Merchant of Venice

''The Merchant of Venice'' is a play by William Shakespeare, believed to have been written between 1596 and 1598. A merchant in Venice named Antonio defaults on a large loan taken out on behalf of his dear friend, Bassanio, and provided by a ...

'' (1879). His Shylock was as much discussed as his Hamlet had been, the dignity with which he invested the vengeful Jew

Jews (, , ), or the Jewish people, are an ethnoreligious group and nation, originating from the Israelites of ancient Israel and Judah. They also traditionally adhere to Judaism. Jewish ethnicity, religion, and community are highly inte ...

ish merchant marking a departure from the traditional interpretation of the role.

After the production of Tennyson's ''The Cup'' and revivals of ''Othello'' (in which Irving played

After the production of Tennyson's ''The Cup'' and revivals of ''Othello'' (in which Irving played Iago

Iago () is a fictional character in Shakespeare's '' Othello'' (c. 1601–1604). Iago is the play's main antagonist and Othello's standard-bearer. He is the husband of Emilia who is in turn the attendant of Othello's wife Desdemona. Iago ha ...

to Edwin Booth

Edwin Thomas Booth (November 13, 1833 – June 7, 1893) was an American stage actor and theatrical manager who toured throughout the United States and the major capitals of Europe, performing Shakespearean plays. In 1869, he founded Booth's Th ...

's title character) and ''Romeo and Juliet

''The Tragedy of Romeo and Juliet'', often shortened to ''Romeo and Juliet'', is a Shakespearean tragedy, tragedy written by William Shakespeare about the romance between two young Italians from feuding families. It was among Shakespeare's ...

'', there began a period at the Lyceum which had a potent effect on the English stage.

''Much Ado About Nothing

''Much Ado About Nothing'' is a Shakespearean comedy, comedy by William Shakespeare thought to have been written in 1598 and 1599.See textual notes to ''Much Ado About Nothing'' in ''The Norton Shakespeare'' (W. W. Norton & Company, 1997 ) p. ...

'' (1882) was followed by ''Twelfth Night

''Twelfth Night, or What You Will'' is a romantic comedy by William Shakespeare, believed to have been written around 1601–1602 as a Twelfth Night entertainment for the close of the Christmas season. The play centres on the twins Viola an ...

'' (1884); an adaptation of Goldsmith

A goldsmith is a Metalworking, metalworker who specializes in working with gold and other precious metals. Modern goldsmiths mainly specialize in jewelry-making but historically, they have also made cutlery, silverware, platter (dishware), plat ...

's '' Vicar of Wakefield'' by W. G. Wills (1885); ''Faust'' (1885); ''Macbeth'' (1888, with incidental music

Incidental music is music in a play, television program, radio program, video game, or some other presentation form that is not primarily musical. The term is less frequently applied to film music, with such music being referred to instead as th ...

by Arthur Sullivan

Sir Arthur Seymour Sullivan (13 May 1842 – 22 November 1900) was an English composer. He is best known for 14 comic opera, operatic Gilbert and Sullivan, collaborations with the dramatist W. S. Gilbert, including ''H.M.S. Pinaf ...

); ''The Dead Heart'', by Watts Phillips (1889); ''Ravenswood'' by Herman, and Merivales' dramatic version of Scott

Scott may refer to:

Places

Canada

* Scott, Quebec, municipality in the Nouvelle-Beauce regional municipality in Quebec

* Scott, Saskatchewan, a town in the Rural Municipality of Tramping Lake No. 380

* Rural Municipality of Scott No. 98, Sas ...

's '' Bride of Lammermoor'' (1890). Portrayals in 1892 of the characters of Wolsey in ''Henry VIII

Henry VIII (28 June 149128 January 1547) was King of England from 22 April 1509 until his death in 1547. Henry is known for his Wives of Henry VIII, six marriages and his efforts to have his first marriage (to Catherine of Aragon) annulled. ...

'' and of the title character in ''King Lear

''The Tragedy of King Lear'', often shortened to ''King Lear'', is a Shakespearean tragedy, tragedy written by William Shakespeare. It is loosely based on the mythological Leir of Britain. King Lear, in preparation for his old age, divides his ...

'' were followed in 1893 by a performance of Becket

''Becket or The Honour of God'' (), often shortened to ''Becket'', is a 1959 stage play written in French by Jean Anouilh. It is a depiction of the conflict between Thomas Becket and King Henry II of England leading to Becket's assassination in ...

in Tennyson

Alfred Tennyson, 1st Baron Tennyson (; 6 August 1809 – 6 October 1892) was an English poet. He was the Poet Laureate of the United Kingdom, Poet Laureate during much of Queen Victoria's reign. In 1829, Tennyson was awarded the Chancellor's ...

's play of the same name. During these years, too, Irving, with the whole Lyceum company, paid several successful visits to the United States and Canada, which were repeated in succeeding years. As Terry aged, there seemed to be fewer opportunities for her in his company; that was one reason she eventually left, moving on to less steady but beloved stage work, including solo performances of Shakespeare's women.

Safety theatres

In 1887, theExeter Theatre Royal fire

On 5 September 1887, a fire broke out in the backstage area of the Theatre Royal, Exeter, Theatre Royal in Exeter, England, during the production of ''The Romany Rye (play), The Romany Rye''. The fire caused panic throughout the theatre, with 18 ...

claimed the lives of 186 people, injuring dozens more, during a performance of ''The Romany Rye

''The Romany Rye'' is a novel by George Borrow, written in 1857 as a sequel to '' Lavengro'' (1851).

The novel

Largely thought to be at least partly autobiographical, ''The Romany Rye'' follows from ''Lavengro'' (1851). The title can be trans ...

'' being staged by fellow actor-manager Wilson Barrett

Wilson Barrett (born William Henry Barrett; 18 February 1846 – 22 July 1904) was an English manager, actor, and playwright. With his company, Barrett is credited with attracting the largest crowds of English theatregoers ever because of his suc ...

at the Theatre Royal, Exeter

The Theatre Royal, Exeter was the name of several theatres situated in the city centre of Exeter, Devon, England in the United Kingdom.

Early theatres and fires

The name "Theatre Royal" was first applied in Exeter by the mid-1830s to what ha ...

.

Irving was one of the first high-profile people to donate to the relief fund for survivors and orphans, sending £100.

The fire caused Irving to become involved in ensuring better safety for theatres, and he developed the "Irving Safety Theatre" principles, working with eminent architect Alfred Darbyshire

Alfred Darbyshire (20 June 183 – 5 July 1908) was a British architect.

Education and career

Alfred Darbyshire was born on 20 June 1839 in Salford, Greater Manchester, Salford, Lancashire, to William Darbyshire, the manager of a dyeworks, and ...

. These principles included making the theatre site isolated, dividing the auditorium from the back of the house, a minimum height above street level for any part of the audience, providing two separate exits for every section of the audience, improving stage construction including a smoke flue, and fire-resistant construction throughout.

The first theatre built to these principles was the rebuilt New Theatre Royal in Exeter.

Influence on Bram Stoker's ''Dracula''

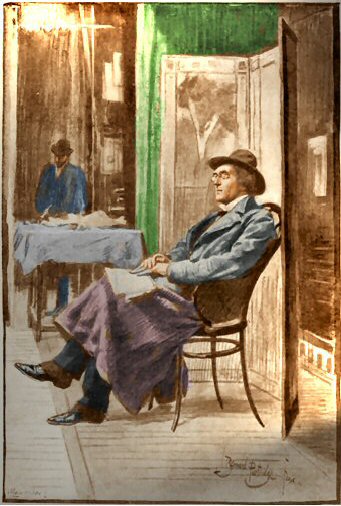

From 1878,Bram Stoker

Abraham Stoker (8 November 1847 – 20 April 1912), better known by his pen name Bram Stoker, was an Irish novelist who wrote the 1897 Gothic horror novel ''Dracula''. The book is widely considered a milestone in Vampire fiction, and one of t ...

worked for Irving as a business manager at the Lyceum. Stoker idolised Irving to the point that "As one contemporary remarked, 'To Bram, Irving is as a god, and can do no wrong.' In the considered judgment of one biographer, Stoker's friendship with Irving was 'the most important love relationship of his adult life.'" Irving, however, "… was a self-absorbed and profoundly manipulative man. He enjoyed cultivating rivalries between his followers, and to remain in his circle required constant, careful courting of his notoriously fickle affections." When Stoker began writing ''Dracula

''Dracula'' is an 1897 Gothic fiction, Gothic horror fiction, horror novel by Irish author Bram Stoker. The narrative is Epistolary novel, related through letters, diary entries, and newspaper articles. It has no single protagonist and opens ...

'', Irving was the chief inspiration for the title character

The title character in a narrative work is one who is named or referred to in the title of the work. In a performed work such as a play or film, the performer who plays the title character is said to have the title role of the piëce. The title o ...

. In his 2002 paper for ''The American Historical Review

''The American Historical Review'' is a quarterly academic history journal published by Oxford University Press on behalf of the American Historical Association, for which it is an official publication. It targets readers interested in all period ...

'', "Buffalo Bill Meets Dracula: William F. Cody, Bram Stoker, and the Frontiers of Racial Decay", historian Louis S. Warren writes:

Later years

The chief remaining novelties at the Lyceum during Irving's term as sole manager (at the beginning of 1899 the theatre passed into the hands of a limited-liability company) wereArthur Conan Doyle

Sir Arthur Ignatius Conan Doyle (22 May 1859 – 7 July 1930) was a British writer and physician. He created the character Sherlock Holmes in 1887 for ''A Study in Scarlet'', the first of four novels and fifty-six short stories about Hol ...

's ''Waterloo'' (1894); J. Comyns Carr

Joseph William Comyns Carr (1 March 1849 – 12 December 1916), often referred to as J. Comyns Carr, was an English drama and art critic, gallery director, author, poet, playwright and theatre manager.

Beginning his career as an art critic, Car ...

's ''King Arthur'' in 1895; ''Cymbeline

''Cymbeline'' (), also known as ''The Tragedie of Cymbeline'' or ''Cymbeline, King of Britain'', is a play by William Shakespeare set in British Iron Age, Ancient Britain () and based on legends that formed part of the Matter of Britain concer ...

'', in which Irving played Iachimo, in 1896; Sardou's ''Madame Sans-Gene'' in 1897; and ''Peter the Great'', a play by Laurence Irving, the actor's second son, in 1898.

Irving received a death threat in 1899 from fellow actor (and murderer of William Terriss

William Terriss (20 February 1847 – 16 December 1897), born as William Charles James Lewin, was an English actor, known for his swashbuckling hero roles, such as Robin Hood, as well as parts in classic dramas and comedies. He was also a nota ...

) Richard Archer Prince. Terriss had been stabbed at the stage door of the Adelphi Theatre

The Adelphi Theatre is a West End theatre, located on the Strand in the City of Westminster, central London. The present building is the fourth on the site. The theatre has specialised in comedy and musical theatre, and today it is a receiv ...

in December 1897 and in the wake of his death, Prince was committed to Broadmoor Criminal Lunatic Asylum

Broadmoor Hospital is a high-security psychiatric hospital in Crowthorne, Berkshire, England.

It is the oldest of England's three high-security psychiatric hospitals, the other two being Ashworth Hospital near Liverpool and Rampton Secure Ho ...

. Irving was critical of the unusually lenient sentence, remarking "Terriss was an actor, so his murderer will not be executed." Two years later, Prince had found Irving's home address and threatened to murder him "when he gets out". Irving was advised to submit the letter to the Home Office to ensure Prince's continued incarceration, which Irving declined to do.

In 1898 Irving was Rede Lecturer at the University of Cambridge

The University of Cambridge is a Public university, public collegiate university, collegiate research university in Cambridge, England. Founded in 1209, the University of Cambridge is the List of oldest universities in continuous operation, wo ...

. The new regime at the Lyceum was signalled by the production of Sardou's ''Robespierre

Maximilien François Marie Isidore de Robespierre (; ; 6 May 1758 – 28 July 1794) was a French lawyer and statesman, widely recognised as one of the most influential and controversial figures of the French Revolution. Robespierre fer ...

'' in 1899, in which Irving reappeared after a serious illness, and in 1901 by an elaborate revival of ''Coriolanus

''Coriolanus'' ( or ) is a tragedy by William Shakespeare, believed to have been written between 1605 and 1608. The play is based on the life of the legendary Roman leader Gnaeus Marcius Coriolanus. Shakespeare worked on it during the same ...

''. Irving's only subsequent production in London was as Sardou's ''Dante

Dante Alighieri (; most likely baptized Durante di Alighiero degli Alighieri; – September 14, 1321), widely known mononymously as Dante, was an Italian Italian poetry, poet, writer, and philosopher. His ''Divine Comedy'', originally called ...

'' (1903) at the Drury Lane.

Death

On 13 October 1905, at 67 years old, Irving had completed a performance and suffered astroke

Stroke is a medical condition in which poor cerebral circulation, blood flow to a part of the brain causes cell death. There are two main types of stroke: brain ischemia, ischemic, due to lack of blood flow, and intracranial hemorrhage, hemor ...

after returning to his lodging at the lobby of the Midland Hotel, Bradford

The Midland Hotel is a 90- bedroom three-star Victorian hotel in Bradford city centre, owned and managed by Britannia Hotels.

The architect was Charles Trubshaw, who was contracted to design many railway stations for Midland Railway Company. ...

, where he died before medical attention could arrive. A more dramatic, but untrue story, would later be written by Thomas Anstey Guthrie

Sir Thomas Anstey Guthrie (8 August 1856 – 10 March 1934) was an English writer (writing as F. Anstey or F. T. Anstey), most noted for his comic novel '' Vice Versa'' about a boarding-school boy and his father exchanging identities. His repu ...

in his 'Long Retrospect': "Within three months, on 13 October 1905, Henry Irving, when appearing as Becket at the Bradford Theatre, was seized with syncope just after uttering Becket's dying words 'Into thy hands, O Lord, into thy hands', and though he lived for an hour or so longer he never spoke again." (Thomas Anstey Guthrie. "Long Retrospect")

Another witness at the play, Bram Stoker

Abraham Stoker (8 November 1847 – 20 April 1912), better known by his pen name Bram Stoker, was an Irish novelist who wrote the 1897 Gothic horror novel ''Dracula''. The book is widely considered a milestone in Vampire fiction, and one of t ...

(known for being the author of ''Dracula''), told reporters later that "We chatted for awhile after the play, and I left him, although not notably strong, not in any way cast down and not more exhausted than had been usual for some time. A little more than three-quarters of an hour afterward I was sent for by the man who attended Sir Henry from the theatre, who told me that he had fainted or collapsed on entering the Midland Hotel. Hurrying down, I found Sir Henry lying in the passage— dead." Stoker added, "Had he died on the stage, as might have happened, it would have given the shock and bitter memory to many tender hearts." Guthrie's confusion may have come from the fact that the character Becket's last words in the play are "O Lord, into thy hands," but, as a correspondent noted, "Then the curtain falls, and within a very short time, having just reached his hotel, the great actor breathed his last."

The chair that he was sitting in before he died is now at the Garrick Club

The Garrick Club is a private members' club in London, founded in 1831 as a club for "actors and men of refinement to meet on equal terms". It is one of the oldest members' clubs in the world. Its 1,500 members include many actors, writers, ...

. He was cremated and his ashes buried in Westminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey, formally titled the Collegiate Church of Saint Peter at Westminster, is an Anglican church in the City of Westminster, London, England. Since 1066, it has been the location of the coronations of 40 English and British m ...

, thereby becoming the first person to be cremated before interment at Westminster.

There is a statue of him near the National Portrait Gallery National Portrait Gallery may refer to:

* National Portrait Gallery (Australia), in Canberra

* National Portrait Gallery (Sweden), in Mariefred

*National Portrait Gallery (United States), in Washington, D.C.

*National Portrait Gallery, London

...

in London. That statue, as well as the influence of Irving himself, plays an important part in the Robertson Davies

William Robertson Davies (28 August 1913 – 2 December 1995) was a Canadian novelist, playwright, critic, journalist, and professor. He was one of Canada's best known and most popular authors and one of its most distinguished " men of letters" ...

novel '' World of Wonders''. The Irving Memorial Garden was opened on 19 July 1951 by Laurence Olivier

Laurence Kerr Olivier, Baron Olivier ( ; 22 May 1907 – 11 July 1989) was an English actor and director. He and his contemporaries Ralph Richardson and John Gielgud made up a trio of male actors who dominated the British stage of the m ...

.

Legacy

Both on and off the stage, Irving always maintained a high ideal of his profession, and in 1895 he received aknighthood

A knight is a person granted an honorary title of a knighthood by a head of state (including the pope) or representative for service to the monarch, the church, or the country, especially in a military capacity.

The concept of a knighthood ...

(first offered in 1883), the first ever accorded an actor. He was also the recipient of honorary degrees from the universities of Dublin

Dublin is the capital and largest city of Republic of Ireland, Ireland. Situated on Dublin Bay at the mouth of the River Liffey, it is in the Provinces of Ireland, province of Leinster, and is bordered on the south by the Dublin Mountains, pa ...

(LL.D

A Doctor of Laws (LL.D.) is a doctoral degree in legal studies. The abbreviation LL.D. stands for ''Legum Doctor'', with the double “L” in the abbreviation referring to the early practice in the University of Cambridge to teach both canon law ...

1892), Cambridge

Cambridge ( ) is a List of cities in the United Kingdom, city and non-metropolitan district in the county of Cambridgeshire, England. It is the county town of Cambridgeshire and is located on the River Cam, north of London. As of the 2021 Unit ...

( Litt.D 1898), and Glasgow

Glasgow is the Cities of Scotland, most populous city in Scotland, located on the banks of the River Clyde in Strathclyde, west central Scotland. It is the List of cities in the United Kingdom, third-most-populous city in the United Kingdom ...

(LL.D

A Doctor of Laws (LL.D.) is a doctoral degree in legal studies. The abbreviation LL.D. stands for ''Legum Doctor'', with the double “L” in the abbreviation referring to the early practice in the University of Cambridge to teach both canon law ...

1899). He also received the Komthur Cross, 2nd class, of the Saxe-Ernestine House Order

The Saxe-Ernestine House Order ()Hausorden

Herzogliche Haus Sachsen-Coburg und Gotha was a ...

of Herzogliche Haus Sachsen-Coburg und Gotha was a ...

Saxe-Coburg-Gotha

Saxe-Coburg and Gotha (), or Saxe-Coburg-Gotha ( ), was an Ernestine duchy in Thuringia ruled by a branch of the House of Wettin, consisting of territories in the present-day states of Thuringia and Bavaria in Germany. It lasted from 1826 to ...

and Saxe-Meiningen

Saxe-Meiningen ( ; ) was one of the Saxon duchies held by the Ernestine duchies, Ernestine line of the House of Wettin, located in the southwest of the present-day Germany, German state of Thuringia.

Established in 1681, by partition of the Ern ...

.

His acting divided critics; opinions differed as to the extent to which his mannerisms of voice and deportment interfered with or assisted the expression of his ideas. Irving's idiosyncratic style of acting and its effect on amateur players were mildly satirised in ''

His acting divided critics; opinions differed as to the extent to which his mannerisms of voice and deportment interfered with or assisted the expression of his ideas. Irving's idiosyncratic style of acting and its effect on amateur players were mildly satirised in ''The Diary of a Nobody

''The Diary of a Nobody'' is an 1892 English comic novel written by the brothers George and Weedon Grossmith, with illustrations by the latter. It originated as an intermittent serial in '' Punch'' magazine in 1888–89 and first appeared in ...

''. Mr. Pooter's son brings Mr. Burwin-Fosselton of the Holloway Comedians to supper, a young man who entirely monopolised the conversation, and:

"...who not only looked rather like Mr Irving but seemed to imagine he ''was'' the celebrated actor... he began doing the Irving business all through supper. He sank so low down in his chair that his chin was almost on a level with the table, and twice he kicked Carrie under the table, upset his wine, and flashed a knife uncomfortably near Gowing's face."In

T. S. Eliot

Thomas Stearns Eliot (26 September 18884 January 1965) was a poet, essayist and playwright.Bush, Ronald. "T. S. Eliot's Life and Career", in John A Garraty and Mark C. Carnes (eds), ''American National Biography''. New York: Oxford University ...

's poem, " Gus: The Theatre Cat" (), the title character's old age and theatrical distinction are expressed in the couplet:

For he once was a Star of the highest degree--He has acted with Irving, he's acted with

Tree

In botany, a tree is a perennial plant with an elongated stem, or trunk, usually supporting branches and leaves. In some usages, the definition of a tree may be narrower, e.g., including only woody plants with secondary growth, only ...

.

These verses appear in the lyrics of the homonymous song in Andrew Lloyd Webber

Andrew Lloyd Webber, Baron Lloyd-Webber (born 22 March 1948) is an English composer and impresario of musical theatre. Several of his musicals have run for more than a decade both in the West End theatre, West End and on Broadway theatre, Broad ...

's 1981 musical ''Cats

The cat (''Felis catus''), also referred to as the domestic cat or house cat, is a small domesticated carnivorous mammal. It is the only domesticated species of the family Felidae. Advances in archaeology and genetics have shown that the ...

''.

In the 1963 West End musical

West End theatre is mainstream professional theatre staged in the large theatres in and near the West End of London.Christopher Innes"West End"in ''The Cambridge Guide to Theatre'' (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998), pp. 1194–1195, ...

comedy '' Half a Sixpence'' the actor Chitterlow does an impression of Irving in '' The Bells''. Percy French

William Percy French (1 May 1854 – 24 January 1920) was an Irish songwriter, author, poet, entertainer and painter.

Life

French was born at Clooneyquinn House, near Tulsk, County Roscommon, the son of an Anglo-Irish landlord, Christopher F ...

's burlesque heroic poem " Abdul Abulbul Amir" lists among the mock-heroic attributes of Abdul's adversary, the Russian Count Ivan Skavinsky Skavar, that "he could imitate Irving". In the 1995 film '' A Midwinter's Tale'' by Kenneth Branagh

Sir Kenneth Charles Branagh ( ; born 10 December 1960) is a British actor and filmmaker. Born in Belfast and raised primarily in Reading, Berkshire, Branagh trained at RADA in London and served as its president from 2015 to 2024. List of award ...

, two actors discuss Irving, and one of them, Richard Briers

Richard David Briers (14 January 1934 – 17 February 2013) was an English actor whose five-decade career encompassed film, radio, stage and television.

Briers first came to prominence as George Starling in '' Marriage Lines'' (1961–66), but ...

does an imitation of his speech. In the play ''The Woman in Black

''The Woman in Black'' is a 1983 gothic horror novel by English writer Susan Hill, about a mysterious spectre that haunts a small English town. A television film based on it, also called '' The Woman in Black'', was produced in 1989, with a s ...

'', set in the Victorian era, the actor playing Kipps tells Kipps 'We'll make an Irving of you yet,' in Act 1, as Kipps is not a very good actor due to his inexperience. In the political sitcom ''Yes, Prime Minister

''Yes Minister'' is a British political satire sitcom written by Antony Jay and Jonathan Lynn. Comprising three seven-episode series, it was first transmitted on BBC2 from 1980 to 1984. A sequel, ''Yes, Prime Minister'', ran for 16 episodes f ...

'' (sequel to ''Yes Minister

''Yes Minister'' is a British political satire sitcom written by Antony Jay and Jonathan Lynn. Comprising three seven-episode series, it was first transmitted on BBC2 from 1980 to 1984. A sequel, ''Yes, Prime Minister'', ran for 16 episodes f ...

''), in the episode "The Patron of the Arts", first aired on 14 January 1988, the Prime Minister is asked what was the last play he'd seen and replies "Hamlet." When asked "Whose?" – specifically, who played Hamlet, not who wrote it – he is unable to remember and is prompted with the suggestion "Henry Irving?" to audience laughter. A play by David Hare, to premiere in 2025 and starring Ralph Fiennes

Ralph Nathaniel Twisleton-Wykeham-Fiennes (; born 22 December 1962) is an English actor, film producer, and director. He has received List of awards and nominations received by Ralph Fiennes, various accolades, including a British Academy Film ...

as Irving, ''Grace Pervades'', explores the life of Irving, Terry and Terry's children, Edith Craig

Edith Ailsa Geraldine Craig ( Edith Godwin; 9 December 1869 – 27 March 1947), known as Edy Craig, was a prolific theatre director, producer, costume designer and early pioneer of the women's suffrage movement in England. She was the daughte ...

and Edward Gordon Craig.West End Theatre, 26 March 2024

Biography

In 1906,Bram Stoker

Abraham Stoker (8 November 1847 – 20 April 1912), better known by his pen name Bram Stoker, was an Irish novelist who wrote the 1897 Gothic horror novel ''Dracula''. The book is widely considered a milestone in Vampire fiction, and one of t ...

published a two-volume biography about Irving called '' Personal Reminiscences of Henry Irving''.Stoker, Bram (1906). Personal Reminiscences of Henry Irving. A complete PDF version of the book can be downloaded from Bram Stoker Online. Retrieved from .

See also

* Irving FamilyNotes

References

Further reading

* Stoker, Bram''Personal Reminiscences of Henry Irving: Volume 1''

an

''Volume 2''

London : W. Heinemann, 1906. Scanned books via

Internet Archive

The Internet Archive is an American 501(c)(3) organization, non-profit organization founded in 1996 by Brewster Kahle that runs a digital library website, archive.org. It provides free access to collections of digitized media including web ...

.

* Archer, William 1885Henry Irving, Actor and Manager: A Critical Study

London:Field & Tuer. * Beerbohm, Max. 1928. 'Henry Irving' in ''A Variety of Things.'' New York, Knopf. *Holroyd, Michael. 2008. ''A Strange Eventful History'', Farrar Straus Giroux, *Irving, Laurence. 1989. ''Henry Irving: The Actor and His World''. Lively Arts. * *

External links

The Irving Society

with bio and pics

Henry Irving-Ellen Terry tour correspondence, 1884-1896

held by the Billy Rose Theatre Division,

New York Public Library for the Performing Arts

The New York Public Library for the Performing Arts, Dorothy and Lewis B. Cullman Center, is located at 40 Lincoln Center Plaza, in the Lincoln Center complex on the Upper West Side in Manhattan, New York City. Situated between the Metropolitan O ...

*

*

Irving Disher Collection

Rare Books, Special Collections, and Preservation, River Campus Libraries,

University of Rochester

The University of Rochester is a private university, private research university in Rochester, New York, United States. It was founded in 1850 and moved into its current campus, next to the Genesee River in 1930. With approximately 30,000 full ...

{{DEFAULTSORT:Irving, Henry

1838 births

1905 deaths

English male stage actors

English male Shakespearean actors

19th-century English male actors

20th-century English male actors

19th-century theatre

Actor-managers

Knights Bachelor

Actors awarded knighthoods

English people of Cornish descent

People from South Somerset (district)

Burials at Westminster Abbey

Freemasons of the United Grand Lodge of England

19th-century English theatre managers

20th-century theatre managers

Members of The Lambs Club