Sir Charles Warren on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Sir Charles Warren (7 February 1840 – 21 January 1927) was a British Army officer of the

Warren was appointed a

Warren was appointed a

Underground Jerusalem

' (1876) *

The Temple or the Tomb

' (1880) * *

Plans, elevations, sections, &c., shewing the results of the excavations at Jerusalem

' (1884) *

On the Veldt in the Seventies

' (1902) *

The Ancient Cubit and Our Weights and Measures

' (1903) *

The Early Weights and Measures of Mankind

' (1914)

Palestine Exploration Fund page on Warren

*

Portraits of Warren in the National Portrait Gallery

{{DEFAULTSORT:Warren, Charles 19th-century police officers British Army generals British colonial army officers 1840 births 1927 deaths British archaeologists British surveyors British Army personnel of the Second Boer War Commissioners of Police of the Metropolis Commissioners of the Bechuanaland Protectorate Royal Engineers officers Fellows of the Royal Society People from Bangor, Gwynedd People educated at Bridgnorth Endowed School People educated at Cheltenham College People educated at Wem Grammar School Graduates of the Royal Military College, Sandhurst Graduates of the Royal Military Academy, Woolwich Knights Grand Cross of the Order of St Michael and St George Knights Commander of the Order of the Bath Recipients of the Order of the Medjidie, 3rd class The Scout Association People associated with Scouting Biblical archaeologists Freemasons of the United Grand Lodge of England British military personnel of the Bechuanaland Expedition 1880s in Bechuanaland Protectorate 19th-century British military personnel British expatriates in the Ottoman Empire History of Jerusalem Burials in Kent Military personnel from Gwynedd Palestinologists

Royal Engineers

The Corps of Royal Engineers, usually called the Royal Engineers (RE), and commonly known as the ''Sappers'', is the engineering arm of the British Army. It provides military engineering and other technical support to the British Armed Forces ...

. He was one of the earliest European archaeologists of the Biblical Holy Land

The term "Holy Land" is used to collectively denote areas of the Southern Levant that hold great significance in the Abrahamic religions, primarily because of their association with people and events featured in the Bible. It is traditionall ...

, and particularly of the Temple Mount

The Temple Mount (), also known as the Noble Sanctuary (Arabic: الحرم الشريف, 'Haram al-Sharif'), and sometimes as Jerusalem's holy esplanade, is a hill in the Old City of Jerusalem, Old City of Jerusalem that has been venerated as a ...

. Much of his military service was spent in British South Africa. Previously he was Commissioner of Police of the Metropolis, the head of the London Metropolitan Police, from 1886 to 1888 during the Jack the Ripper

Jack the Ripper was an unidentified serial killer who was active in and around the impoverished Whitechapel district of London, England, in 1888. In both criminal case files and the contemporaneous journalistic accounts, the killer was also ...

murders. His command in combat during the Second Boer War

The Second Boer War (, , 11 October 189931 May 1902), also known as the Boer War, Transvaal War, Anglo–Boer War, or South African War, was a conflict fought between the British Empire and the two Boer republics (the South African Republic and ...

was criticised, but he achieved considerable success during his long life in his military and civil posts.

Education and early military career

Warren was born in Bangor,Gwynedd

Gwynedd () is a county in the north-west of Wales. It borders Anglesey across the Menai Strait to the north, Conwy, Denbighshire, and Powys to the east, Ceredigion over the Dyfi estuary to the south, and the Irish Sea to the west. The ci ...

, Wales

Wales ( ) is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is bordered by the Irish Sea to the north and west, England to the England–Wales border, east, the Bristol Channel to the south, and the Celtic ...

, the son of Major-General Sir Charles Warren. He was educated at Bridgnorth Grammar School

Bridgnorth Endowed School is a coeducational secondary school with Academy (English school), academy status, located in the market town of Bridgnorth in the rural county of Shropshire, England. Founded in 1503, The Endowed School is a state sch ...

and Wem Grammar School in Shropshire

Shropshire (; abbreviated SalopAlso used officially as the name of the county from 1974–1980. The demonym for inhabitants of the county "Salopian" derives from this name.) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in the West M ...

. He also attended Cheltenham College

Cheltenham College is a public school ( fee-charging boarding and day school for pupils aged 13–18) in Cheltenham, Gloucestershire, England. The school opened in 1841 as a Church of England foundation and is known for its outstanding linguis ...

for one term in 1854, from which he went to the Royal Military College, Sandhurst

The Royal Military College (RMC) was a United Kingdom, British military academy for training infantry and cavalry Officer (armed forces), officers of the British Army, British and British Indian Army, Indian Armies. It was founded in 1801 at Gre ...

and then the Royal Military Academy at Woolwich

Woolwich () is a town in South London, southeast London, England, within the Royal Borough of Greenwich.

The district's location on the River Thames led to its status as an important naval, military and industrial area; a role that was mainta ...

(1855–57). On 27 December 1857, he was commissioned a second lieutenant in the Royal Engineers

The Corps of Royal Engineers, usually called the Royal Engineers (RE), and commonly known as the ''Sappers'', is the engineering arm of the British Army. It provides military engineering and other technical support to the British Armed Forces ...

. On 1 September 1864, he married Fanny Margaretta Haydon (died 1919); they had two sons and two daughters. Warren was a devout Anglican

Anglicanism, also known as Episcopalianism in some countries, is a Western Christianity, Western Christian tradition which developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the ...

and an enthusiastic Freemason

Freemasonry (sometimes spelled Free-Masonry) consists of fraternal groups that trace their origins to the medieval guilds of stonemasons. Freemasonry is the oldest secular fraternity in the world and among the oldest still-existing organizati ...

, becoming the third District Grand Master of the Eastern Archipelago in Singapore and the founding Master of the Quatuor Coronati Lodge.

Military and politics

From 1861 to 1865, Warren worked on surveyingGibraltar

Gibraltar ( , ) is a British Overseas Territories, British Overseas Territory and British overseas cities, city located at the southern tip of the Iberian Peninsula, on the Bay of Gibraltar, near the exit of the Mediterranean Sea into the A ...

. During this time he surveyed the Rock of Gibraltar

The Rock of Gibraltar (from the Arabic name Jabal Ṭāriq , meaning "Mountain of Tariq ibn Ziyad, Tariq") is a monolithic limestone mountain high dominating the western entrance to the Mediterranean Sea. It is situated near the end of a nar ...

using trigonometry and with the support of Major-General Frome, he created two long scale detailed models of Gibraltar. One of these was kept at Woolwich

Woolwich () is a town in South London, southeast London, England, within the Royal Borough of Greenwich.

The district's location on the River Thames led to its status as an important naval, military and industrial area; a role that was mainta ...

, but the other, which survives, is on display at Gibraltar Museum. These models not only depicted the shape of The Rock and harbour but also every road and building on the surface. From 1865 to 1867, he was an assistant instructor in surveying at the School of Military Engineering in Chatham. He was promoted captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader or highest rank officer of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police depa ...

for this work.

Western Palestine-Jerusalem

In 1867, Warren was recruited by thePalestine Exploration Fund

The Palestine Exploration Fund is a British society based in London. It was founded in 1865, shortly after the completion of the Ordnance Survey of Jerusalem by Royal Engineers of the War Department. The Fund is the oldest known organization i ...

to conduct Biblical archaeology

Biblical archaeology is an academic school and a subset of Biblical studies and Levantine archaeology. Biblical archaeology studies archaeological sites from the Ancient Near East and especially the Holy Land (also known as Land of Israel and ...

"reconnaissance" with a view of further research and excavation to be undertaken later in Ottoman Syria

Ottoman Syria () is a historiographical term used to describe the group of divisions of the Ottoman Empire within the region of the Levant, usually defined as being east of the Mediterranean Sea, west of the Euphrates River, north of the Ara ...

, but more specifically the Holy Land

The term "Holy Land" is used to collectively denote areas of the Southern Levant that hold great significance in the Abrahamic religions, primarily because of their association with people and events featured in the Bible. It is traditionall ...

or Biblical Palestine. During the PEF Survey of Palestine

The PEF Survey of Palestine was a series of surveys carried out by the Palestine Exploration Fund (PEF) between 1872 and 1877 for the completed Survey of Western Palestine (SWP) and in 1880 for the soon abandoned Survey of Eastern Palestine. The ...

he conducted one of the first major excavations at the Temple Mount

A number of archaeological excavations at the Temple Mount—a celebrated and contentious religious site in the Old City of Jerusalem—have taken place over the last 150 years. Excavations in the area represent one of the more sensitive areas ...

in Jerusalem, thereby ushering in a new age of Biblical archaeology. His most significant discovery was a water shaft, now known as Warren's Shaft, and a series of tunnels underneath the Temple Mount.

Warren and his team also improved the topographic map of Jerusalem and made the first excavations of Tell es-Sultan

Tell es-Sultan (, ''lit.'' Sultan's Hill), also known as Tel Jericho or Ancient Jericho, is an archaeological site and a UNESCO World Heritage Site in Palestine, in the city of Jericho, consisting of the remains of the oldest fortified city in th ...

, site of biblical city of Jericho

Jericho ( ; , ) is a city in the West Bank, Palestine, and the capital of the Jericho Governorate. Jericho is located in the Jordan Valley, with the Jordan River to the east and Jerusalem to the west. It had a population of 20,907 in 2017.

F ...

. Some of the sites listed on Warren's topographic map, particularly that of Acra (where he places it in the Upper City, contrary to Josephus

Flavius Josephus (; , ; ), born Yosef ben Mattityahu (), was a Roman–Jewish historian and military leader. Best known for writing '' The Jewish War'', he was born in Jerusalem—then part of the Roman province of Judea—to a father of pr ...

who places it in the Lower City), have since been corrected and updated.

In 1870, Warren returned to Britain, where he began writing a book about archaeology. His findings from the expedition would be published later as "The survey of Western Palestine-Jerusalem" (1884), written with C.R. Conder. Other books by Warren about the area include "The Recovery of Jerusalem" (1871), "Underground Jerusalem" (1876) and "The Land of Promise" (1875).

Warren's most significant contribution is his exploration of a subterranean shaft in Jerusalem and which is now named after him, ''viz''., Warren's Shaft. A 2013 publication, ''The Walls of the Temple Mount'', provided more specifics about Warren's work, as summarised in a book review."... he concentrated on excavating shafts down beneath the ground to the level of the lower parts of the external Temple Mount walls, recording the different types of stonework he encountered at different levels and other features, such as Robinson’s Arch on the western side and the Herodian street below it. ... in 1884 the PEF published a large portfolio of 50 of Warren’s maps, plans and drawings titled Plans, Elevations, Sections, etc., Shewing the Results of the Excavations at Jerusalem, 1867–70 (now known as the 'Warren Atlas')."

South Africa

He served briefly atDover

Dover ( ) is a town and major ferry port in Kent, southeast England. It faces France across the Strait of Dover, the narrowest part of the English Channel at from Cap Gris Nez in France. It lies southeast of Canterbury and east of Maidstone. ...

and then at the School of Gunnery at Shoeburyness (1871–73). In 1876, the Colonial Office

The Colonial Office was a government department of the Kingdom of Great Britain and later of the United Kingdom, first created in 1768 from the Southern Department to deal with colonial affairs in North America (particularly the Thirteen Colo ...

appointed him special commissioner to survey the boundary between Griqualand West

Griqualand West is an area of central South Africa with an area of 40,000 km2 that now forms part of the Northern Cape Province. It was inhabited by the Griqua people – a semi-nomadic, Afrikaans-speaking nation of mixed-race origin, w ...

and the Orange Free State

The Orange Free State ( ; ) was an independent Boer-ruled sovereign republic under British suzerainty in Southern Africa during the second half of the 19th century, which ceased to exist after it was defeated and surrendered to the British Em ...

. For this work, he was made a Companion of the Order of St Michael and St George

The Most Distinguished Order of Saint Michael and Saint George is a British order of chivalry founded on 28 April 1818 by George, Prince of Wales (the future King George IV), while he was acting as prince regent for his father, King George I ...

(CMG) in 1877. In the Transkei War (1877–78), he commanded the Diamond Fields Horse and was badly wounded at Perie Bush. For this service, he was mentioned in despatches

To be mentioned in dispatches (or despatches) describes a member of the armed forces whose name appears in an official report written by a superior officer and sent to the high command, in which their gallant or meritorious action in the face of t ...

and promoted to brevet lieutenant colonel. He was then appointed special commissioner to investigate "native questions" in Bechuanaland and commanded the Northern Border Expedition troops in quelling the rebellion there. In 1879, he became Administrator of Griqualand West. The town Warrenton in the Northern Cape Province of South Africa is named after him.

Palmer expedition investigation

In 1880, Warren returned to England to become Chief Instructor in Surveying at the School of Military Engineering. He held this post until 1884, but it was interrupted in 1882, when the Admiralty sent him to Sinai to discover what had happened to ProfessorEdward Henry Palmer

Edward Henry Palmer (7 August 184010 August 1882), known as E. H. Palmer, was an England, English oriental studies, orientalist and explorer.

Biography

Youth and education

Palmer was born in Green Street, Cambridge, the son of a private scho ...

's archaeological expedition. He discovered that the expedition members had been robbed and murdered, located their remains, and brought their killers to justice. For this, he was created a Knight Commander of the Order of St Michael and St George

The Most Distinguished Order of Saint Michael and Saint George is a British order of chivalry founded on 28 April 1818 by George, Prince of Wales (the future King George IV), while he was acting as prince regent for his father, King George III ...

(KCMG) on 24 May 1883 and was also awarded an Order of the Medjidie, Third Class by the Egyptian government. In 1883, he was also made a Knight of Justice of the Order of St. John of Jerusalem, and in June 1884 he was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society

Fellowship of the Royal Society (FRS, ForMemRS and HonFRS) is an award granted by the Fellows of the Royal Society of London to individuals who have made a "substantial contribution to the improvement of natural science, natural knowledge, incl ...

(FRS).

Bechuanaland and election

In December 1884, by now a lieutenant-colonel, Warren was sent as HM Special Commissioner to command a military expedition to Bechuanaland, to assert British sovereignty in the face of encroachments from Germany and the Transvaal, and to suppress theBoer

Boers ( ; ; ) are the descendants of the proto Afrikaans-speaking Free Burghers of the eastern Cape frontier in Southern Africa during the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries. From 1652 to 1795, the Dutch East India Company controlled the Dutch ...

freebooter states of Stellaland and Goshen, which were backed by the Transvaal and were stealing land and cattle from the local Tswana

Tswana may refer to:

* Tswana people, the Bantu languages, Bantu speaking people in Botswana, South Africa, Namibia, Zimbabwe, Zambia, and other Southern Africa regions

* Tswana language, the language spoken by the (Ba)Tswana people

* Tswanaland, ...

tribes.

Becoming known as the Warren Expedition, the force of 4,000 British and local troops headed north from Cape Town

Cape Town is the legislature, legislative capital city, capital of South Africa. It is the country's oldest city and the seat of the Parliament of South Africa. Cape Town is the country's List of municipalities in South Africa, second-largest ...

, accompanied by the first three observation balloons ever used by the British Army in the field. The expedition achieved its aims without bloodshed, and Warren was recalled in September 1885 and appointed a Knight Grand Cross of the Order of St Michael and St George (GCMG) on 4 October 1885. In November-December the same year he stood in the general election

A general election is an electoral process to choose most or all members of a governing body at the same time. They are distinct from By-election, by-elections, which fill individual seats that have become vacant between general elections. Gener ...

for election to Parliament

In modern politics and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: Representation (politics), representing the Election#Suffrage, electorate, making laws, and overseeing ...

as an independent Liberal candidate in the Sheffield Hallam constituency with a radical manifesto. He lost by 690 votes.

Commissioner of Police

Appointment

In 1885, Warren was appointed commander at Suakin in 1886. A few weeks after he arrived, however, he was appointed Commissioner of Police of the Metropolis following Sir Edmund Henderson's resignation. The exact rationale for his selection is still unknown. Up to that time, and for some time into the 20th century, the heads of Scotland Yard were selected from the ranks of the military. In Warren's case, he may have been selected in part by his involvement in discovering the fate of Professor Palmer's expedition into the Sinai in 1883. If so there may have been a serious error regarding his "police work" in that case, as it was a military investigation and not a civil style police operation. The Metropolitan Police was in a bad state when Warren took over, suffering from Henderson's inactivity over the past few years. Economic conditions in London were bad, leading to demonstrations. He was concerned for his men's welfare, but much of this went unheeded. His men found him rather aloof, although he generally had good relations with his superintendents. At Queen Victoria's Golden Jubilee in 1887, the police received considerable adverse publicity after Miss Elizabeth Cass, an apparently respectable young seamstress, was (possibly) mistakenly arrested for soliciting, and was vocally supported by her employer in the courts.Friction

To make matters worse, Colonel Warren, a Liberal, did not get along withConservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy and ideology that seeks to promote and preserve traditional institutions, customs, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civiliza ...

Home Secretary

The secretary of state for the Home Department, more commonly known as the home secretary, is a senior minister of the Crown in the Government of the United Kingdom and the head of the Home Office. The position is a Great Office of State, maki ...

Henry Matthews, appointed a few months after he became Commissioner. Matthews supported the desire of the Assistant Commissioner (Crime), James Monro, to remain effectively independent of the Commissioner and also supported the Receiver, the force's chief financial officer, who continually clashed with Warren. Home Office

The Home Office (HO), also known (especially in official papers and when referred to in Parliament) as the Home Department, is the United Kingdom's interior ministry. It is responsible for public safety and policing, border security, immigr ...

Permanent Secretary

A permanent secretary is the most senior Civil Service (United Kingdom), civil servant of a department or Ministry (government department), ministry charged with running the department or ministry's day-to-day activities. Permanent secretaries are ...

Godfrey Lushington did not get on with Warren either. Warren was pilloried in the press for his extravagant dress uniform, his concern for the quality of his men's boots (a sensible concern considering they walked up to 20 miles a day, but one which was derided as a military obsession with kit), and his reintroduction of drill

A drill is a tool used for making round holes or driving fasteners. It is fitted with a drill bit for making holes, or a screwdriver bit for securing fasteners. Historically, they were powered by hand, and later mains power, but cordless b ...

. The radical press completely turned against him after Bloody Sunday on 13 November 1887, when a demonstration in Trafalgar Square

Trafalgar Square ( ) is a public square in the City of Westminster in Central London. It was established in the early-19th century around the area formerly known as Charing Cross. Its name commemorates the Battle of Trafalgar, the Royal Navy, ...

was broken up by 4,000 police officers on foot, 300 infantry

Infantry, or infantryman are a type of soldier who specialize in ground combat, typically fighting dismounted. Historically the term was used to describe foot soldiers, i.e. those who march and fight on foot. In modern usage, the term broadl ...

men and 600 mounted police and Life Guards.

Warren was appointed a

Warren was appointed a Knight Commander of the Order of the Bath

The Most Honourable Order of the Bath is a British order of chivalry founded by King George I of Great Britain, George I on 18 May 1725. Recipients of the Order are usually senior British Armed Forces, military officers or senior Civil Service ...

(KCB) on 7 January 1888. Later that year he renamed the four District Superintendents (ranking between the Superintendents and the Assistant Commissioners and each in charge of a group of divisions

Division may refer to:

Mathematics

*Division (mathematics), the inverse of multiplication

* Division algorithm, a method for computing the result of mathematical division Military

*Division (military), a formation typically consisting of 10,000 t ...

) Chief Constables, adding a Chief Constable at the head of the Met's Criminal Investigation Department

The Criminal Investigation Department (CID) is the branch of a police force to which most plainclothes criminal investigation, detectives belong in the United Kingdom and many Commonwealth of Nations, Commonwealth nations. A force's CID is disti ...

(CID) in 1889. Monro insisted that the first holder of the latter post should be a friend of his, Melville Macnaghten, but Warren opposed his appointment on the grounds that during a riot in Bengal

Bengal ( ) is a Historical geography, historical geographical, ethnolinguistic and cultural term referring to a region in the Eastern South Asia, eastern part of the Indian subcontinent at the apex of the Bay of Bengal. The region of Benga ...

Macnaghten had been "beaten by Hindoos", as he put it. This grew into a major row between Warren and Monro, with both men offering their resignation to the Home Secretary. Matthews accepted Monro's resignation, but simply moved him to the Home Office and allowed him to keep command of Special Branch

Special Branch is a label customarily used to identify units responsible for matters of national security and Intelligence (information gathering), intelligence in Policing in the United Kingdom, British, Commonwealth of Nations, Commonwealth, ...

, which was his particular interest. Robert Anderson was appointed Assistant Commissioner (Crime) and Superintendent Adolphus Williamson was appointed Chief Constable (CID). Both men were encouraged to liaise with Monro behind Warren's back.

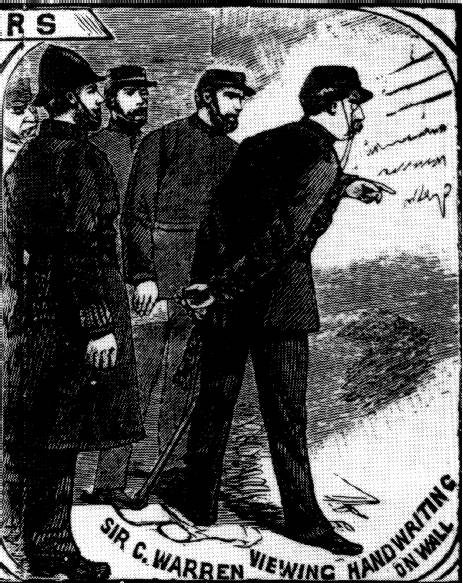

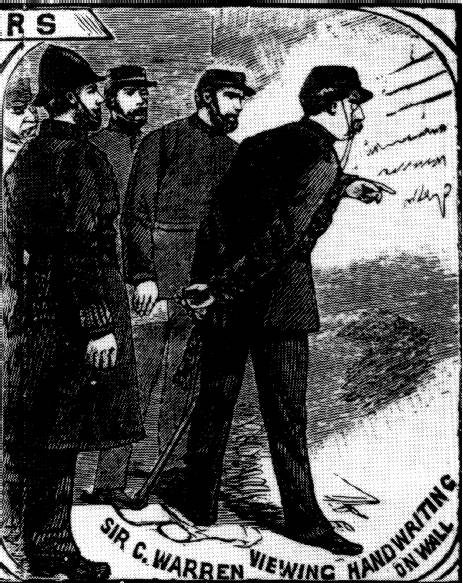

Jack the Ripper

Colonel Warren's biggest difficulty was theJack the Ripper

Jack the Ripper was an unidentified serial killer who was active in and around the impoverished Whitechapel district of London, England, in 1888. In both criminal case files and the contemporaneous journalistic accounts, the killer was also ...

case. In his book, ''Abberline: The Man Who Hunted Jack the Ripper'', author Peter Thurgood indicates that Warren was criticised during the investigation. He was blamed for failing to track down the killer, accused of failing to offer a reward for information (although that plan was actually rejected by the Home Office

The Home Office (HO), also known (especially in official papers and when referred to in Parliament) as the Home Department, is the United Kingdom's interior ministry. It is responsible for public safety and policing, border security, immigr ...

), accused of assigning an inadequate number of investigators (patently untrue) and favouring uniformed constables instead of detectives (probably untrue). In response, Warren wrote an article outlining his views and the facts for '' Murray's Magazine''; the article also indicated that he favoured vigilante activity in finding the Ripper. He was censured by the Home Office for revealing the workings of the police department and for writing an article without permission.

As recently as 2015, a book about the Ripper case by Bruce Robinson castigated Warren as a "lousy cop" and suggested that a "huge establishment cover-up" and a Masonic conspiracy had been involved. In its book review, ''The Guardian

''The Guardian'' is a British daily newspaper. It was founded in Manchester in 1821 as ''The Manchester Guardian'' and changed its name in 1959, followed by a move to London. Along with its sister paper, ''The Guardian Weekly'', ''The Guardi ...

'' stated that "most historians put the police's failure to catch the Ripper down to incompetence" but did not specifically name Warren in this context.

Warren finally had enough of criticism and resigned – coincidentally right before the murder of Mary Jane Kelly on 9 November 1888. But he agreed to stay on until his successor was in place and continued in post until 1 December. He then returned to his army career. Nearly every superintendent on the force visited him at home to express their regret over his resignation. One attendee praised Warren for his thoughtfulness and his caring for the men in his command.

Later military career and Boer War

Warren returned to military duties and in 1889 was sent to command thegarrison

A garrison is any body of troops stationed in a particular location, originally to guard it. The term now often applies to certain facilities that constitute a military base or fortified military headquarters.

A garrison is usually in a city ...

in Singapore

Singapore, officially the Republic of Singapore, is an island country and city-state in Southeast Asia. The country's territory comprises one main island, 63 satellite islands and islets, and one outlying islet. It is about one degree ...

, with a simultaneous promotion to the rank of Major-General in 1893 remaining in Singapore until 1895. After returning to England, he commanded the Thames District from 1895 to 1898, when he was promoted to lieutenant general

Lieutenant general (Lt Gen, LTG and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. The rank traces its origins to the Middle Ages, where the title of lieutenant general was held by the second-in-command on the battlefield, who was norma ...

in 1897 and was moved to the Reserve List.

Royal Engineer Yacht Club

Watermanship being one of the many skills required of the Sapper led to the formation of a sailing club at the School of Military Engineering in 1812 and later to the development of cutter rowing teams. Construction of a canal linking the Thames and Medway rivers in 1824 gave the Royal Engineers an inland waterway to practice these skills, with the officer responsible for the canal drawn from the Corps of Royal Engineers. In 1899 as General Officer Commanding the Thames and Medway Canal, General Sir Charles Warren presented a challenge shield for a championship cutter race on the RiverMedway

Medway is a Unitary authorities of England, unitary authority area with Borough status in the United Kingdom, borough status in the ceremonial county of Kent in South East England. It was formed in 1998 by merging the boroughs of City of Roche ...

against the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the naval warfare force of the United Kingdom. It is a component of His Majesty's Naval Service, and its officers hold their commissions from the King of the United Kingdom, King. Although warships were used by Kingdom ...

. The Sapper teams were drawn from members of the Submarine Mining School, but when the service was disbanded in 1905, the tradition of cutter rowing was continued by the fieldwork squads. The REYC continues to compete against the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the naval warfare force of the United Kingdom. It is a component of His Majesty's Naval Service, and its officers hold their commissions from the King of the United Kingdom, King. Although warships were used by Kingdom ...

Sailing Association annually to this day. The club developed and became the Royal Engineer Yacht Club in 1846, making it one of the most senior yacht clubs in the United Kingdom. The REYC continues to this day, operating three club yachts and competing on behalf of the Corps at races around the world. The club is one of the oldest sports clubs in the British Army.

Second Boer War

On the outbreak of theBoer War

The Second Boer War (, , 11 October 189931 May 1902), also known as the Boer War, Transvaal War, Anglo–Boer War, or South African War, was a conflict fought between the British Empire and the two Boer republics (the South African Republic an ...

in 1899, he returned to the colours to command the 5th Division of the South African Field Force. The decision to give command to Warren was surprising. By then, Warren was 59 years old, was said to have a "disagreeable temper", had little recent experience leading troops in battle and did not get along with his superior, General Sir Redvers Buller.

In January 1900, Warren bungled the second attempted relief of Ladysmith, which was a west flanking movement over the Tugela River

The Tugela River (; ) is the largest river in KwaZulu-Natal Province, South Africa. With a total length of , and a drop of 1370 metres in the lower 480 km, it is one of the most important rivers of the country.

The river originates in M ...

. At the Battle of Spion Kop

The Battle of Spion Kop (; ) was a military engagement between British forces and two Boer Republics, the South African Republic and the Orange Free State, during the campaign by the British to relieve the besieged city Ladysmith during the ...

, on 23–24 January 1900, he had operational command, and his failures of judgment, delay and indecision despite his superior forces culminated in the disaster. Farwell highlighted Warren's fixation with the army's oxen and his view that Hlangwane Hill was the key to Colenso. Farwell suggested Warren was "perhaps the worst" of the British generals in the Boer War and certainly the most "preposterous".Farwell, p.159 He was described by Redvers Buller in a letter to his wife as "a duffer", responsible for losing him "a great chance".

Warren was recalled to Britain in August 1900 and never again commanded troops in the field. He was, however, appointed Honorary Colonel of the 1st Gloucestershire Royal Engineers (Volunteers) in November 1901, promoted general

A general officer is an Officer (armed forces), officer of high rank in the army, armies, and in some nations' air force, air and space forces, marines or naval infantry.

In some usages, the term "general officer" refers to a rank above colone ...

in 1904 and became Colonel-Commandant of the Royal Engineers in 1905. A book by South African author Owen Coetzer attempted "in a small way to vindicate him" for his Boer War actions.

Retirement years

From 1908, Warren became involved with Baden-Powell in the creation of theBoy Scout

A Scout, Boy Scout, Girl Scout or, in some countries, a Pathfinder is a participant in the Scout Movement, usually aged 10–18 years, who engage in learning scoutcraft and outdoor and other special interest activities. Some Scout organizatio ...

movement. He was also involved with another group, the Church Lads' Brigade and 1st St Lawrence Scout Group, then called 1st Ramsgate – Sir Charles Warren's Own Scouts

He had previously authored several books on Biblical archaeology, particularly Jerusalem, and also wrote "''On Veldt in the Seventies''", and "''The Ancient Cubit and Our Weights and Measures''". He died of pneumonia

Pneumonia is an Inflammation, inflammatory condition of the lung primarily affecting the small air sacs known as Pulmonary alveolus, alveoli. Symptoms typically include some combination of Cough#Classification, productive or dry cough, ches ...

, brought on by a bout of influenza

Influenza, commonly known as the flu, is an infectious disease caused by influenza viruses. Symptoms range from mild to severe and often include fever, runny nose, sore throat, muscle pain, headache, coughing, and fatigue. These sympto ...

, at his home in Weston-super-Mare

Weston-super-Mare ( ) is a seaside town and civil parish in the North Somerset unitary district, in the county of Somerset, England. It lies by the Bristol Channel south-west of Bristol between Worlebury Hill and Bleadon Hill. Its population ...

, Somerset

Somerset ( , ), Archaism, archaically Somersetshire ( , , ) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South West England. It is bordered by the Bristol Channel, Gloucestershire, and Bristol to the north, Wiltshire to the east ...

, was given a military funeral in Canterbury

Canterbury (, ) is a City status in the United Kingdom, city and UNESCO World Heritage Site, in the county of Kent, England; it was a county borough until 1974. It lies on the River Stour, Kent, River Stour. The city has a mild oceanic climat ...

, and was buried in the churchyard at Westbere, Kent

Kent is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South East England. It is bordered by Essex across the Thames Estuary to the north, the Strait of Dover to the south-east, East Sussex to the south-west, Surrey to the west, and Gr ...

, next to his wife. A biography of him was published in 1941 by his son-in-law the Revd Watkin Wynn Williams.Watkin W. Williams, ''The Life of General Sir Charles Warren'' (Oxford : Basil Blackwell, 1941)

Fictional portrayals

Warren was played by Basil Henson in the 1973 miniseries ''Jack the Ripper

Jack the Ripper was an unidentified serial killer who was active in and around the impoverished Whitechapel district of London, England, in 1888. In both criminal case files and the contemporaneous journalistic accounts, the killer was also ...

''. He was played by Anthony Quayle in the 1979 film '' Murder by Decree'', which features the characters of Sherlock Holmes

Sherlock Holmes () is a Detective fiction, fictional detective created by British author Arthur Conan Doyle. Referring to himself as a "Private investigator, consulting detective" in his stories, Holmes is known for his proficiency with obser ...

and Doctor Watson

Dr. John H. Watson is a fictional character in the Sherlock Holmes stories by Arthur Conan Doyle, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. Along with Sherlock Holmes, Dr. Watson first appeared in the novel ''A Study in Scarlet'' (1887). "The Adventure of Shosc ...

in a dramatisation of a conspiracy theory

A conspiracy theory is an explanation for an event or situation that asserts the existence of a conspiracy (generally by powerful sinister groups, often political in motivation), when other explanations are more probable.Additional sources:

* ...

concerning the Ripper case. In the 1988 made-for-TV mini-series ''Jack the Ripper

Jack the Ripper was an unidentified serial killer who was active in and around the impoverished Whitechapel district of London, England, in 1888. In both criminal case files and the contemporaneous journalistic accounts, the killer was also ...

'', which followed the same conspiracy theory as ''Murder by Decree'', he was played by Hugh Fraser. The mini-series shows his final act as commissioner ordering lead detective Fred Abberline to suppress his findings on the investigation in order to protect the royal family from scandal. In the 2001 film '' From Hell'' he was played by Ian Richardson.

Bibliography

* *Underground Jerusalem

' (1876) *

The Temple or the Tomb

' (1880) * *

Plans, elevations, sections, &c., shewing the results of the excavations at Jerusalem

' (1884) *

On the Veldt in the Seventies

' (1902) *

The Ancient Cubit and Our Weights and Measures

' (1903) *

The Early Weights and Measures of Mankind

' (1914)

References

Sources

*Austin, Ron. ''The Australian Illustrated Encyclopedia of the Zulu and Boer Wars'', Slouch Hat Publication, McCrae, 1999. *Bloomfield, Jeffrey, ''The Making of the Commissioner: 1886'', R.W. Stone, Q.P.M. (ed.), The Criminologist, Vol. 12, No. b3, p. 139–155; reprinted, Paul Begg (Exec. ed.), The Ripperologist, No. 47, July 2003, pp. 6–15. *Coetzer, Owen. ''The Anglo-Boer War: The Road to Infamy, 1899–1900'', Arms and Armour, 1996. * Farwell, Byron, ''The Great Boer War'', Allen Lane, London, 1976 (plus subsequent publications) *Fido, Martin and Keith Skinner, ''The Official Encyclopedia of Scotland Yard'' (Virgin Books, London: 1999) * *Kruger, Rayne. ''Goodbye Dolly Gray: The Story of the Boer War'', 1959 *''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

The ''Dictionary of National Biography'' (''DNB'') is a standard work of reference on notable figures from History of the British Isles, British history, published since 1885. The updated ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'' (''ODNB'') ...

''

*Pakenham, T. ''The Boer War'' (1979)

Further reading

*External links

Palestine Exploration Fund page on Warren

*

Portraits of Warren in the National Portrait Gallery

{{DEFAULTSORT:Warren, Charles 19th-century police officers British Army generals British colonial army officers 1840 births 1927 deaths British archaeologists British surveyors British Army personnel of the Second Boer War Commissioners of Police of the Metropolis Commissioners of the Bechuanaland Protectorate Royal Engineers officers Fellows of the Royal Society People from Bangor, Gwynedd People educated at Bridgnorth Endowed School People educated at Cheltenham College People educated at Wem Grammar School Graduates of the Royal Military College, Sandhurst Graduates of the Royal Military Academy, Woolwich Knights Grand Cross of the Order of St Michael and St George Knights Commander of the Order of the Bath Recipients of the Order of the Medjidie, 3rd class The Scout Association People associated with Scouting Biblical archaeologists Freemasons of the United Grand Lodge of England British military personnel of the Bechuanaland Expedition 1880s in Bechuanaland Protectorate 19th-century British military personnel British expatriates in the Ottoman Empire History of Jerusalem Burials in Kent Military personnel from Gwynedd Palestinologists