Sir Alan Cobham on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Sir Alan John Cobham,

On 25 November 1926, Cobham attempted but failed to be the first person to deliver mail to New York City by air from the east, planning to fly mail from the White Star ocean liner RMS ''Homeric'' in a

On 25 November 1926, Cobham attempted but failed to be the first person to deliver mail to New York City by air from the east, planning to fly mail from the White Star ocean liner RMS ''Homeric'' in a  Cobham was one of the founding directors, of

Cobham was one of the founding directors, of

exhibition about Cobham

In 2016 the RAF exhibited hi

Flying Circus

In 2016 he was inducted into the Airlift/Tanker Association Hall of Fame.

Biography

at Cobham Plc {{DEFAULTSORT:Cobham, Alan 1894 births British aviation pioneers People educated at Wilson's School, Wallington Royal Flying Corps officers 1973 deaths English aviators Knights Commander of the Order of the British Empire Recipients of the Air Force Cross (United Kingdom) English test pilots Britannia Trophy winners British Army personnel of World War I Croydon Airport

KBE

KBE may refer to:

* Knight Commander of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire, post-nominal letters

* Knowledge-based engineering

Knowledge-based engineering (KBE) is the application of knowledge-based systems technology to the domain o ...

, AFC (6 May 1894 – 21 October 1973) was an English

English usually refers to:

* English language

* English people

English may also refer to:

Culture, language and peoples

* ''English'', an adjective for something of, from, or related to England

* ''English'', an Amish ter ...

aviation pioneer.

Early life

As a child he attendedWilson's School

Wilson's School is a state boys' grammar school with academy status in the London Borough of Sutton, England.

It was founded as Wilson's Grammar School in Camberwell in 1615 by Edward Wilson, making it one of the country's oldest state schoo ...

, which was then in Camberwell

Camberwell ( ) is an List of areas of London, area of South London, England, in the London Borough of Southwark, southeast of Charing Cross.

Camberwell was first a village associated with the church of St Giles' Church, Camberwell, St Giles ...

, London

London is the Capital city, capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of both England and the United Kingdom, with a population of in . London metropolitan area, Its wider metropolitan area is the largest in Wester ...

. The school was relocated to the former site of Croydon Airport in 1975.

After National Service and a short career at the Bar, Michael Cobham followed him into the Flight Refuelling business, and for many years was in charge of it.

Career

Alan Cobham began work as a teenage commercial apprentice in the City of London. He enjoyed the outdoors, and after completing his apprenticeship spent a year working on his uncle's farm, hoping to make a career in estate management. After a brief return to London commercial work, in August 1914 he joined the British Army, and was directed to theRoyal Army Veterinary Corps

The Royal Army Veterinary Corps (RAVC), known as the Army Veterinary Corps (AVC) until it gained the royal prefix on 27 November 1918, is an administrative and operational branch of the British Army responsible for the provision, training and c ...

due to his farming experience. He served on the Western Front from 1914 to 1917. He dealt mainly with injured horses, and attained the rank of Staff Veterinary Sergeant. After transfer to the Royal Flying Corps

The Royal Flying Corps (RFC) was the air arm of the British Army before and during the First World War until it merged with the Royal Naval Air Service on 1 April 1918 to form the Royal Air Force. During the early part of the war, the RFC sup ...

and then the Royal Air Force

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the Air force, air and space force of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories and Crown Dependencies. It was formed towards the end of the World War I, First World War on 1 April 1918, on the merger of t ...

, he became a Pilot Officer flying instructor.

After the war Cobham became a test pilot for the de Havilland

The de Havilland Aircraft Company Limited (pronounced , ) was a British aviation manufacturer established in late 1920 by Geoffrey de Havilland at Stag Lane Aerodrome Edgware on the outskirts of North London. Operations were later moved to ...

aircraft company, and was the first pilot for the newly formed de Havilland Aeroplane Hire Service. In 1921 he made a 5,000-mile air tour of Europe

Europe is a continent located entirely in the Northern Hemisphere and mostly in the Eastern Hemisphere. It is bordered by the Arctic Ocean to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the west, the Mediterranean Sea to the south, and Asia to the east ...

, visiting 17 cities in three weeks. Between 16 November 1925 and 13 March 1926, he made a trip from London to Cape Town and return in his de Havilland DH.50

The de Havilland DH.50 was a 1920s British large single-engined biplane transport built by de Havilland at Stag Lane Aerodrome, Edgware, and licence-built in Australia, Belgium, and Czechoslovakia.

History

In the early 1920s, Geoffrey de Hav ...

, in which he had replaced the original Siddeley Puma

The Siddeley Puma is a British aero engine developed towards the end of World War I and produced by Siddeley-Deasy. The first Puma engines left the production lines of Siddeley-Deasy in Coventry in August 1917, production continued until Decem ...

engine with a more powerful, air-cooled Jaguar. On 30 June 1926, he set off on a flight from Britain (from the River Medway) to Australia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a country comprising mainland Australia, the mainland of the Australia (continent), Australian continent, the island of Tasmania and list of islands of Australia, numerous smaller isl ...

, where 60,000 people swarmed across the grassy fields of Essendon Airport

Essendon Fields Airport , colloquially known by its former name Essendon Airport, is a public airport serving scheduled commercial, corporate-jet, charter and general aviation flights. It is located next to the intersection of the Tullamarin ...

, Melbourne

Melbourne ( , ; Boonwurrung language, Boonwurrung/ or ) is the List of Australian capital cities, capital and List of cities in Australia by population, most populous city of the States and territories of Australia, Australian state of Victori ...

, when he landed his de Havilland DH.50

The de Havilland DH.50 was a 1920s British large single-engined biplane transport built by de Havilland at Stag Lane Aerodrome, Edgware, and licence-built in Australia, Belgium, and Czechoslovakia.

History

In the early 1920s, Geoffrey de Hav ...

floatplane

A floatplane is a type of seaplane with one or more slender floats mounted under the fuselage to provide buoyancy. By contrast, a flying boat uses its fuselage for buoyancy. Either type of seaplane may also have landing gear suitable for land, ...

(it had been converted to a wheeled undercarriage earlier, at Darwin). During the flight to Australia, Cobham's engineer of the D.H.50 aircraft, Arthur B. Elliot, was shot and killed after they left Baghdad on 5 July 1926. The return flight was undertaken over the same route. Cobham was knighted the same year.

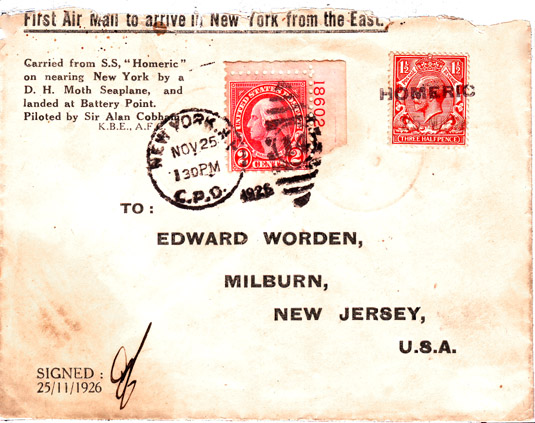

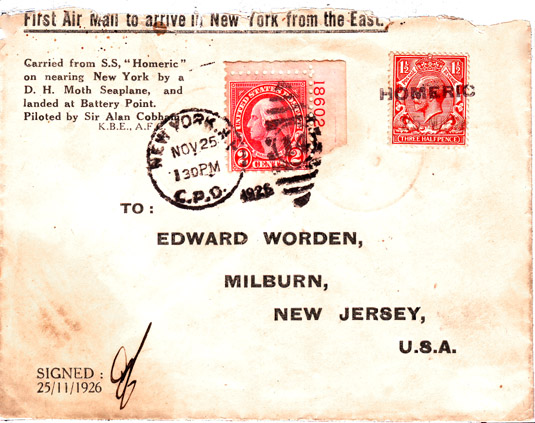

On 25 November 1926, Cobham attempted but failed to be the first person to deliver mail to New York City by air from the east, planning to fly mail from the White Star ocean liner RMS ''Homeric'' in a

On 25 November 1926, Cobham attempted but failed to be the first person to deliver mail to New York City by air from the east, planning to fly mail from the White Star ocean liner RMS ''Homeric'' in a de Havilland DH.60 Moth

The de Havilland DH.60 Moth is a 1920s British two-seat touring and training aircraft that was developed into a series of aircraft by the de Havilland Aircraft Company.

Development

The DH.60 was developed from the larger DH.51 biplane. T ...

floatplane when the ship was about 12 hours from New York harbour on a westbound crossing from Southampton. After the Moth was lowered from the ship, however, Cobham was unable to take off owing to rough water and had to be towed into port by the ship. The same year Cobham was awarded the gold medal by the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale

The World Air Sports Federation (; FAI) is the world governing body for air sports, and also stewards definitions regarding human spaceflight. It was founded on 14 October 1905, and is headquartered in Lausanne, Switzerland. It maintains worl ...

.

Cobham starred as himself in the 1927 British war film '' The Flight Commander'' directed by Maurice Elvey

Maurice Elvey (11 November 1887 – 28 August 1967) was one of the most prolific film directors in British history. He directed nearly 200 films between 1913 and 1957. During the silent film era he directed as many as twenty films per year. He a ...

. In 1927–28 he flew a Short Singapore

The Short Singapore was a British multi-engined biplane flying boat built after the First World War. The design was developed into two four-engined versions: the prototype Singapore II and production Singapore III. The latter became the Royal ...

flying boat

A flying boat is a type of seaplane with a hull, allowing it to land on water. It differs from a floatplane in having a fuselage that is purpose-designed for flotation, while floatplanes rely on fuselage-mounted floats for buoyancy.

Though ...

around the continent of Africa

Africa is the world's second-largest and second-most populous continent after Asia. At about 30.3 million km2 (11.7 million square miles) including adjacent islands, it covers 20% of Earth's land area and 6% of its total surfac ...

landing only in British territory. Cobham wrote his own contemporary accounts of his flights, and recalls them in his biography. The films ''With Cobham to the Cape'' (1926), ''Round Africa with Cobham'' (1928) and ''With Cobham to Kivu'' (1932) contain valuable footage of the flights. Recent commentaries contextualize his flights across the British Empire in the wider events and culture of the time.

In 1929 Cobham mounted his first tour of Britain, called the Municipal Aerodrome Campaign. This was an ambitious plan to encourage town councils to build local airports in the hope of drumming up business for his activities as an aviation consultant. Each event would start with free flights to local dignitaries followed by free flights for local schoolchildren, the latter funded by Sir Charles Wakefield, the founder of Castrol

Castrol Limited is a British oil company that markets industrial and automotive lubricants, offering a wide range of oil, greases and similar products for most lubrication applications. The company was originally named CC Wakefield; the nam ...

, who paid the fares for ten thousand such flights. The day would finish with as many paid-for pleasure flights as could be managed for the public, the income from which would pay his expenses and make him a profit. The tour visited 110 venues between May and October 1929 using a ten-passenger de Havilland DH.61 Giant Moth G-AAEV named Youth of Britain. Cobham declared the tour to have been a great success.

In 1932 he started the National Aviation Day displays – a combination of barnstorming

Barnstorming was a form of entertainment in which stunt pilots performed tricks individually or in groups that were called flying circuses. Devised to "impress people with the skill of pilots and the sturdiness of planes," it became popular in t ...

and joyriding. This consisted of a team of up to fourteen aircraft, ranging from single-seaters to modern airliners, and many skilled pilots. It toured the country, calling at hundreds of sites, some of them regular airfields and some just fields cleared for the occasion. Generally known as "Cobham's Flying Circus

Barnstorming was a form of entertainment in which stunt pilots performed tricks individually or in groups that were called flying circuses. Devised to "impress people with the skill of pilots and the sturdiness of planes," it became popular in t ...

", it was hugely popular, giving thousands of people their first experience of flying, and bringing "air-mindedness" to the population. In 1933 there were two simultaneous tours throughout the season, named Number 1 and Number 2. In 1935 there again were two, but only from 1 July, named Astra and Ferry. These continued until the end of the 1935 season. In the British winter of 1932–33, Cobham took his aerial circus to South Africa (with the mistaken view that it would be the first of its kind there). He closed the circus within weeks of a mid-air disaster in which two of his planes collided over Blackpool

Blackpool is a seaside town in Lancashire, England. It is located on the Irish Sea coast of the Fylde peninsula, approximately north of Liverpool and west of Preston, Lancashire, Preston. It is the main settlement in the Borough of Blackpool ...

on 7 September 1935. The pilot of an Avro

Avro (an initialism of the founder's name) was a British aircraft manufacturer. Its designs include the Avro 504, used as a trainer in the First World War, the Avro Lancaster, one of the pre-eminent bombers of the Second World War, and the d ...

biplane, South African war veteran, Captain Hugh P Stewart and Blackpool sisters, Lilian and Doris Barnes were killed.

Cobham was one of the founding directors, of

Cobham was one of the founding directors, of Airspeed Ltd.

Airspeed Limited was established in 1931 to build aeroplanes in York, England, by A. H. Tiltman and Nevil Shute Norway (the aeronautical engineer and novelist, who used his forenames as his pen-name). The other directors were A. E. Hewitt, ...

, the aircraft manufacturing company started by Nevil Shute Norway

Nevil Shute Norway (17 January 189912 January 1960) was an English novelist and aeronautical engineer who spent his later years in Australia. He used his full name in his engineering career and Nevil Shute as his pen name to protect his enginee ...

and Hessell Tiltman

Alfred Hessell Tiltman FRAeS (1891 – 28 October 1975), known as Hessell Tiltman, was a notable and talented British aircraft designer, and co-founder of Airspeed Ltd.

He graduated in engineering from London University, then served an apprentic ...

. Tiltman had been discharged by the Airship Guarantee Company (a subsidiary of Vickers) after the R101

R101 was one of a pair of British rigid airships completed in 1929 as part of the Imperial Airship Scheme, a British government programme to develop civil airships capable of service on long-distance routes within the British Empire. It was d ...

disaster also caused the grounding of the more successful R100

His Majesty's Airship R100 was a privately designed and built British rigid airship made as part of a two-ship competition to develop a commercial airship service for use on British Empire routes as part of the Imperial Airship Scheme. The o ...

. Cobham was an early and enthusiastic recruit. His early orders for two "Off Plan" Airspeed Ferry

The Airspeed AS.4 Ferry was three-engined ten-seat biplane airliner designed and built by the British aircraft manufacturer Airspeed Limited. It was the company's first powered aircraft to be produced.

It was proposed for development in April ...

s for his National Aviation Day Limited company, were a major boost to the fledgling company.

Cobham's early experiments with in-flight refuelling were based on a specially adapted Airspeed Courier

The Airspeed AS.5 Courier was a British six-seat single-engined light aircraft, designed and produced by the British aircraft manufacturer Airspeed Limited at Portsmouth. It was the first British aircraft fitted with a retractable undercarri ...

. This craft was eventually modified by Airspeed to Cobham's specification, for a non-stop flight from London to India, using in-flight refuelling to extend the aeroplane's flight duration.

In 1935 he founded a small airline, Cobham Air Routes Ltd, that flew from London Croydon Airport

Croydon Airport was the UK's only international airport during the interwar period. It opened in 1920, located near Croydon, then part of Surrey. Built in a Neoclassical architecture, Neoclassical style, it was developed as Britain's main airp ...

to the Channel Islands

The Channel Islands are an archipelago in the English Channel, off the French coast of Normandy. They are divided into two Crown Dependencies: the Jersey, Bailiwick of Jersey, which is the largest of the islands; and the Bailiwick of Guernsey, ...

. Months later, after a crash that killed one of his pilots, he sold it to Olley Air Service

Morton Air Services was one of the earliest post-World War II private, independentindependent from government-owned corporations British airlines formed in 1945. It mainly operated regional short-haul scheduled services within the British Isles an ...

Ltd and turned to the development of inflight refueling

Aerial refueling (American English, en-us), or aerial refuelling (British English, en-gb), also referred to as air refueling, in-flight refueling (IFR), air-to-air refueling (AAR), and tanking, is the process of transferring aviation fuel from ...

. Trials stopped at the outbreak of World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

until interest was successfully revived by the RAF and United States Army Air Forces

The United States Army Air Forces (USAAF or AAF) was the major land-based aerial warfare service component of the United States Army and ''de facto'' aerial warfare service branch of the United States during and immediately after World War II ...

in the last year of the war.

He once remarked: "It's a full time job being Alan Cobham!"

Personal life

In the summer of 1922 he married Gladys Lloyd, and they subsequently had two sons; Geoffrey (b.1925) and Michael (b.1927). Lady Cobham died in 1961 at the age of 63. He retired to theBritish Virgin Islands

The British Virgin Islands (BVI), officially the Virgin Islands, are a British Overseas Territories, British Overseas Territory in the Caribbean, to the east of Puerto Rico and the United States Virgin Islands, US Virgin Islands and north-west ...

, but returned to England, where he died in 1973.

Legacy

In 1997, Cobham was inducted into theInternational Air & Space Hall of Fame

The International Air & Space Hall of Fame is an honor roll of people, groups, organizations, or things that have contributed significantly to the advancement of aerospace flight and technology, sponsored by the San Diego Air & Space Museum. Sin ...

at the San Diego Air & Space Museum

The San Diego Air & Space Museum (SDASM) is an aviation and space exploration museum in San Diego, California. It is located in Balboa Park (San Diego), Balboa Park and is housed in the former Ford Building (San Diego), Ford Building, which is li ...

.

The company he formed is still active in the aviation industry as Cobham plc

Cobham Limited is a British aerospace manufacturing company based in Bournemouth, England.

Cobham was originally founded by Sir Alan Cobham as Flight Refuelling Limited (FRL) in 1934. During 1939, British airline Imperial Airways performed ...

.

In 2015 the Royal Air Force Museum in London staged aexhibition about Cobham

In 2016 the RAF exhibited hi

Flying Circus

In 2016 he was inducted into the Airlift/Tanker Association Hall of Fame.

See also

*Aerofilms

Aerofilms Ltd was the UK's first commercial aerial photography company, founded in 1919 by Francis Wills and Claude Graham White. Wills had served as an Observer with the Royal Naval Air Service during World War I, and was the driving force behin ...

, the UK's first commercial aerial photography company.

* Richard Haine alumnus of the Flying Circus

* Round the Bend

''Round the Bend!'' is a satirical British children's television series, which ran on Children's ITV for three series from January 6, 1989, to May 7, 1991. The programme was produced by Hat Trick Productions for Yorkshire Television. After its f ...

, the novel by Nevil Shute

Nevil Shute Norway (17 January 189912 January 1960) was an English novelist and aeronautical engineer who spent his later years in Australia. He used his full name in his engineering career and Nevil Shute as his pen name to protect his enginee ...

, features Cobham's National Aviation Day flying circus

Barnstorming was a form of entertainment in which stunt pilots performed tricks individually or in groups that were called flying circuses. Devised to "impress people with the skill of pilots and the sturdiness of planes," it became popular in t ...

as an integral part of the plot. The principal character Tom Cutter is said to have been modelled upon one of Cobham's pilots, Martin Hearn, who was a pioneer of wing walking stunts and who later ran his own aircraft assembly plant at Hooton Park

Royal Air Force Hooton Park or more simply RAF Hooton Park, on the Wirral Peninsula, Cheshire, is a former Royal Air Force station originally built for the Royal Flying Corps in 1917 as a training aerodrome for pilots in the First World War. D ...

in Cheshire.

* Philip Stenning, hero of Shute's Marazan

''Marazan'' is the first published novel by the British author Nevil Shute. It was originally published in 1926 by Cassell & Co, then republished in 1951 by William Heinemann. The events of the novel occur, in part, around the Isles of Scilly ...

, is a character modelled upon Cobham and others.

References

External links

* . * .Biography

at Cobham Plc {{DEFAULTSORT:Cobham, Alan 1894 births British aviation pioneers People educated at Wilson's School, Wallington Royal Flying Corps officers 1973 deaths English aviators Knights Commander of the Order of the British Empire Recipients of the Air Force Cross (United Kingdom) English test pilots Britannia Trophy winners British Army personnel of World War I Croydon Airport