The Sino-Soviet split was the gradual worsening of relations between the

People's Republic of China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. With population of China, a population exceeding 1.4 billion, it is the list of countries by population (United Nations), second-most populous country after ...

(PRC) and the

Union of Soviet Socialist Republics

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until it dissolved in 1991. During its existence, it was the largest country by are ...

(USSR) during the

Cold War

The Cold War was a period of global Geopolitics, geopolitical rivalry between the United States (US) and the Soviet Union (USSR) and their respective allies, the capitalist Western Bloc and communist Eastern Bloc, which lasted from 1947 unt ...

. This was primarily caused by divergences that arose from their different interpretations and practical applications of

Marxism–Leninism

Marxism–Leninism () is a communist ideology that became the largest faction of the History of communism, communist movement in the world in the years following the October Revolution. It was the predominant ideology of most communist gov ...

, as influenced by their respective

geopolitics

Geopolitics () is the study of the effects of Earth's geography on politics and international relations. Geopolitics usually refers to countries and relations between them, it may also focus on two other kinds of State (polity), states: ''de fac ...

during the Cold War of 1947–1991.

In the late 1950s and early 1960s, Sino-Soviet debates about the interpretation of

orthodox Marxism

Orthodox Marxism is the body of Marxist thought which emerged after the deaths of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels in the late 19th century, expressed in its primary form by Karl Kautsky. Kautsky's views of Marxism dominated the European Marxis ...

became specific disputes about the Soviet Union's policies of national

de-Stalinization

De-Stalinization () comprised a series of political reforms in the Soviet Union after Death and state funeral of Joseph Stalin, the death of long-time leader Joseph Stalin in 1953, and Khrushchev Thaw, the thaw brought about by ascension of Nik ...

and international

peaceful coexistence

Peaceful coexistence () was a theory, developed and applied by the Soviet Union at various points during the Cold War in the context of primarily Marxist–Leninist foreign policy and adopted by Soviet-dependent socialist states, according to wh ...

with the

Western Bloc

The Western Bloc, also known as the Capitalist Bloc, the Freedom Bloc, the Free Bloc, and the American Bloc, was an unofficial coalition of countries that were officially allied with the United States during the Cold War (1947–1991). While ...

, which Chinese leader

Mao Zedong

Mao Zedong pronounced ; traditionally Romanization of Chinese, romanised as Mao Tse-tung. (26December 18939September 1976) was a Chinese politician, revolutionary, and political theorist who founded the People's Republic of China (PRC) in ...

decried as

revisionism. Against that ideological background, China took a belligerent stance towards the

Western world

The Western world, also known as the West, primarily refers to various nations and state (polity), states in Western Europe, Northern America, and Australasia; with some debate as to whether those in Eastern Europe and Latin America also const ...

, and publicly rejected the Soviet Union's policy of peaceful coexistence between the Western Bloc and

Eastern Bloc

The Eastern Bloc, also known as the Communist Bloc (Combloc), the Socialist Bloc, the Workers Bloc, and the Soviet Bloc, was an unofficial coalition of communist states of Central and Eastern Europe, Asia, Africa, and Latin America that were a ...

.

In addition,

Beijing

Beijing, Chinese postal romanization, previously romanized as Peking, is the capital city of China. With more than 22 million residents, it is the world's List of national capitals by population, most populous national capital city as well as ...

resented the Soviet Union's growing

ties with India due to factors such as the

Sino-Indian border dispute

The Sino–Indian border dispute is an ongoing territorial dispute over the sovereignty of two relatively large, and several smaller, separated pieces of territory between China and India. The territorial disputes between the two countries st ...

, while

Moscow

Moscow is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Russia by population, largest city of Russia, standing on the Moskva (river), Moskva River in Central Russia. It has a population estimated at over 13 million residents with ...

feared that Mao was unconcerned about the horrors of

nuclear warfare

Nuclear warfare, also known as atomic warfare, is a War, military conflict or prepared Policy, political strategy that deploys nuclear weaponry. Nuclear weapons are Weapon of mass destruction, weapons of mass destruction; in contrast to conven ...

.

In 1956, Soviet leader

Nikita Khrushchev

Nikita Sergeyevich Khrushchev (– 11 September 1971) was the General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1953 to 1964 and the Premier of the Soviet Union, Chai ...

denounced

Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Dzhugashvili; 5 March 1953) was a Soviet politician and revolutionary who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until Death and state funeral of Joseph Stalin, his death in 1953. He held power as General Secret ...

and

Stalinism

Stalinism (, ) is the Totalitarianism, totalitarian means of governing and Marxism–Leninism, Marxist–Leninist policies implemented in the Soviet Union (USSR) from History of the Soviet Union (1927–1953), 1927 to 1953 by dictator Jose ...

in the speech "

On the Cult of Personality and Its Consequences

"On the Cult of Personality and Its Consequences" () was a report by Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev, First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, made to the 20th Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union on 25 Febr ...

" and began the de-Stalinization of the USSR. Mao and the Chinese leadership were appalled as the PRC and the USSR progressively diverged in their interpretations and applications of Leninist theory. By 1961, their intractable ideological differences provoked the PRC's formal denunciation of

Soviet communism as the work of "revisionist traitors" in the USSR.

The PRC also declared the Soviet Union

social imperialist.

For Eastern Bloc countries, the Sino-Soviet split was a question of who would lead the revolution for

world communism

World communism, also known as global communism or international communism, is a form of communism placing emphasis on an international scope rather than being individual communist states. The long-term goal of world communism is an unlimited ...

, and to whom (China or the USSR) the

vanguard parties of the world would turn for political advice, financial aid, and military assistance. In that vein, both countries competed for the leadership of world communism through the vanguard parties native to the countries in their

spheres of influence

In the field of international relations, a sphere of influence (SOI) is a spatial region or concept division over which a state or organization has a level of cultural, economic, military, or political exclusivity.

While there may be a formal a ...

. The conflict culminated after the

Zhenbao Island incident in 1969, when the Soviet Union planned to launch a large-scale nuclear strike on China including its capital

Beijing

Beijing, Chinese postal romanization, previously romanized as Peking, is the capital city of China. With more than 22 million residents, it is the world's List of national capitals by population, most populous national capital city as well as ...

, but eventually called off the attack potentially due to an intervention from the

United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

.

In the Western world, the Sino-Soviet split transformed the bi-polar cold war into a tri-polar one. The rivalry facilitated Mao's realization of Sino-American rapprochement with the

US president Richard Nixon's visit to China in 1972. In the West, the policies of

triangular diplomacy and

linkage emerged. Like the

Tito–Stalin split, the occurrence of the Sino-Soviet split also weakened the concept of monolithic communism, the Western perception that the communist nations were collectively united and would not have significant ideological clashes. However, the USSR and China both continued to cooperate with

North Vietnam

North Vietnam, officially the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (DRV; ; VNDCCH), was a country in Southeast Asia from 1945 to 1976, with sovereignty fully recognized in 1954 Geneva Conference, 1954. A member of the communist Eastern Bloc, it o ...

during the

Vietnam War

The Vietnam War (1 November 1955 – 30 April 1975) was an armed conflict in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia fought between North Vietnam (Democratic Republic of Vietnam) and South Vietnam (Republic of Vietnam) and their allies. North Vietnam w ...

into the 1970s, despite rivalry elsewhere.

Historically, the Sino-Soviet split facilitated the Marxist–Leninist ''

Realpolitik

''Realpolitik'' ( ; ) is the approach of conducting diplomatic or political policies based primarily on considerations of given circumstances and factors, rather than strictly following ideological, moral, or ethical premises. In this respect, ...

'' with which Mao established the tri-polar geopolitics (PRC–USA–USSR) of the late-period Cold War (1956–1991) to create an anti-Soviet front, which Maoists connected to the

Three Worlds Theory.

According to Lüthi, there is "no documentary evidence that the Chinese or the Soviets thought about their relationship within a triangular framework during the period."

Origins

Reluctant co-belligerents

During the

Second Sino-Japanese War

The Second Sino-Japanese War was fought between the Republic of China (1912–1949), Republic of China and the Empire of Japan between 1937 and 1945, following a period of war localized to Manchuria that started in 1931. It is considered part ...

, the

Chinese Communist Party

The Communist Party of China (CPC), also translated into English as Chinese Communist Party (CCP), is the founding and One-party state, sole ruling party of the People's Republic of China (PRC). Founded in 1921, the CCP emerged victorious in the ...

(CCP) and the nationalist

Kuomintang

The Kuomintang (KMT) is a major political party in the Republic of China (Taiwan). It was the one party state, sole ruling party of the country Republic of China (1912-1949), during its rule from 1927 to 1949 in Mainland China until Retreat ...

party (KMT) set aside their

civil war

A civil war is a war between organized groups within the same Sovereign state, state (or country). The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies.J ...

to expel the

Empire of Japan

The Empire of Japan, also known as the Japanese Empire or Imperial Japan, was the Japanese nation state that existed from the Meiji Restoration on January 3, 1868, until the Constitution of Japan took effect on May 3, 1947. From Japan–Kor ...

from the

Republic of China

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is a country in East Asia. The main geography of Taiwan, island of Taiwan, also known as ''Formosa'', lies between the East China Sea, East and South China Seas in the northwestern Pacific Ocea ...

. To that end, the Soviet leader,

Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Dzhugashvili; 5 March 1953) was a Soviet politician and revolutionary who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until Death and state funeral of Joseph Stalin, his death in 1953. He held power as General Secret ...

, ordered

Mao Zedong

Mao Zedong pronounced ; traditionally Romanization of Chinese, romanised as Mao Tse-tung. (26December 18939September 1976) was a Chinese politician, revolutionary, and political theorist who founded the People's Republic of China (PRC) in ...

, leader of the CCP, to co-operate with

Chiang Kai-shek, leader of the KMT, in fighting the Japanese. Following the

surrender of Japan

The surrender of the Empire of Japan in World War II was Hirohito surrender broadcast, announced by Emperor Hirohito on 15 August and formally Japanese Instrument of Surrender, signed on 2 September 1945, End of World War II in Asia, ending ...

at the end of

World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, both parties resumed their civil war, which the communists

won by 1949.

At World War II's conclusion, Stalin advised Mao not to seize political power at that time, and, instead, to collaborate with Chiang due to the 1945

USSR–KMT Treaty of Friendship and Alliance. Mao obeyed Stalin in communist solidarity. Three months after the Japanese surrender, in November 1945, when Chiang opposed the annexation of

Tannu Uriankhai (Mongolia) to the USSR, Stalin broke the treaty requiring the Red Army's withdrawal from

Manchuria

Manchuria is a historical region in northeast Asia encompassing the entirety of present-day northeast China and parts of the modern-day Russian Far East south of the Uda (Khabarovsk Krai), Uda River and the Tukuringra-Dzhagdy Ranges. The exact ...

(giving Mao regional control) and ordered Soviet commander

Rodion Malinovsky

Rodion Yakovlevich Malinovsky (; ; – 31 March 1967) was a Soviet military commander and Marshal of the Soviet Union. He served as Minister of Defence of the Soviet Union from 1957 to 1967, during which he oversaw the strengthening of the Sov ...

to give the Chinese communists the Japanese leftover weapons.

In the five-year post-World War II period, the United States partly financed Chiang, his nationalist political party, and the

National Revolutionary Army

The National Revolutionary Army (NRA; zh, labels=no, t=國民革命軍) served as the military arm of the Kuomintang, Chinese Nationalist Party (Kuomintang, or KMT) from 1924 until 1947.

From 1928, it functioned as the regular army, de facto ...

. However, Washington put heavy pressure on Chiang to form a joint government with the communists. US envoy

George Marshall

George Catlett Marshall Jr. (31 December 1880 – 16 October 1959) was an American army officer and statesman. He rose through the United States Army to become Chief of Staff of the United States Army, Chief of Staff of the U.S. Army under pres ...

spent 13 months in China trying without success to broker peace. In the concluding three-year period of the Chinese Civil War, the CCP defeated and expelled the KMT from mainland China. Consequently, the

KMT retreated to Taiwan in December 1949.

Chinese communist revolution

As a revolutionary theoretician of

communism

Communism () is a political sociology, sociopolitical, political philosophy, philosophical, and economic ideology, economic ideology within the history of socialism, socialist movement, whose goal is the creation of a communist society, a ...

seeking to realize a

socialist state

A socialist state, socialist republic, or socialist country is a sovereign state constitutionally dedicated to the establishment of socialism. This article is about states that refer to themselves as socialist states, and not specifically ...

in China, Mao developed and adapted the urban ideology of

Orthodox Marxism

Orthodox Marxism is the body of Marxist thought which emerged after the deaths of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels in the late 19th century, expressed in its primary form by Karl Kautsky. Kautsky's views of Marxism dominated the European Marxis ...

for practical application to the agrarian conditions of pre-industrial China and the

Chinese people

The Chinese people, or simply Chinese, are people or ethnic groups identified with Greater China, China, usually through ethnicity, nationality, citizenship, or other affiliation.

Chinese people are known as Zhongguoren () or as Huaren () by ...

. Mao's Sinification of Marxism–Leninism,

Mao Zedong Thought

Maoism, officially Mao Zedong Thought, is a variety of Marxism–Leninism that Mao Zedong developed while trying to realize a socialist revolution in the agricultural, pre-industrial society of the Republic of China and later the People's Re ...

, established political pragmatism as the first priority for realizing the accelerated

modernization

Modernization theory or modernisation theory holds that as societies become more economically modernized, wealthier and more educated, their political institutions become increasingly liberal democratic and rationalist. The "classical" theories ...

of a country and a people, and ideological orthodoxy as the secondary priority because Orthodox Marxism originated for practical application to the socio-economic conditions of industrialized

Western Europe

Western Europe is the western region of Europe. The region's extent varies depending on context.

The concept of "the West" appeared in Europe in juxtaposition to "the East" and originally applied to the Western half of the ancient Mediterranean ...

in the 19th century.

During the Chinese Civil War in 1947, Mao dispatched American journalist

Anna Louise Strong

Anna Louise Strong (November 24, 1885 – March 29, 1970) was an American journalist and activist, best known for her reporting on and support for Communism, communist movements in the Soviet Union and the People's Republic of China.Archives Wes ...

to the West, bearing political documents explaining China's socialist future, and asked that she "show them to Party leaders in the United States and Europe", for their better understanding of the

Chinese Communist Revolution

The Chinese Communist Revolution was a social revolution, social and political revolution in China that began in 1927 and culminated with the proclamation of the People's Republic of China (PRC) in 1949. The revolution was led by the Chinese C ...

, but that it was not "necessary to take them to Moscow."

Mao trusted Strong because of her positive reportage about him, as a theoretician of communism, in the article "The Thought of Mao Tse-Tung", and about the CCP's communist revolution, in the 1948 book ''Dawn Comes Up Like Thunder Out of China: An Intimate Account of the Liberated Areas in China'', which reports that Mao's

intellectual

An intellectual is a person who engages in critical thinking, research, and Human self-reflection, reflection about the nature of reality, especially the nature of society and proposed solutions for its normative problems. Coming from the wor ...

achievement was "to change Marxism from a European

ormto an Asiatic form . . . in ways of which neither Marx nor Lenin could dream."

Treaty of Sino-Soviet friendship

In 1950, Mao and Stalin safeguarded the national interests of China and the Soviet Union with the

Treaty of Friendship, Alliance and Mutual Assistance. The treaty improved the two countries' geopolitical relationship on political, military and economic levels. Stalin's largesse to Mao included a loan for $300 million; military aid, should Japan attack the PRC; and the transfer of the

Chinese Eastern Railway in Manchuria,

Port Arthur and

Dalian

Dalian ( ) is a major sub-provincial port city in Liaoning province, People's Republic of China, and is Liaoning's second largest city (after the provincial capital Shenyang) and the third-most populous city of Northeast China (after Shenyang ...

to Chinese control. In return, the PRC recognized the independence of the

Mongolian People's Republic

The Mongolian People's Republic (MPR) was a socialist state that existed from 1924 to 1992, located in the historical region of Outer Mongolia. Its independence was officially recognized by the Nationalist government of Republic of China (1912� ...

.

Despite the favourable terms, the treaty of socialist friendship included the PRC in the geopolitical

hegemony

Hegemony (, , ) is the political, economic, and military predominance of one State (polity), state over other states, either regional or global.

In Ancient Greece (ca. 8th BC – AD 6th c.), hegemony denoted the politico-military dominance of ...

of the USSR, but unlike the governments of the Soviet satellite states in Eastern Europe, the USSR did not control Mao's government. In six years, the great differences between the Soviet and the Chinese interpretations and applications of Marxism–Leninism voided the Sino-Soviet Treaty of Friendship.

In 1953, guided by Soviet economists, the PRC applied the USSR's model of

planned economy

A planned economy is a type of economic system where investment, production and the allocation of capital goods takes place according to economy-wide economic plans and production plans. A planned economy may use centralized, decentralized, ...

, which gave first priority to the development of

heavy industry

Heavy industry is an industry that involves one or more characteristics such as large and heavy products; large and heavy equipment and facilities (such as heavy equipment, large machine tools, huge buildings and large-scale infrastructure); o ...

, and second priority to the production of consumer goods. Later, ignoring the guidance of technical advisors, Mao launched the

Great Leap Forward

The Great Leap Forward was an industrialization campaign within China from 1958 to 1962, led by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). Party Chairman Mao Zedong launched the campaign to transform the country from an agrarian society into an indu ...

to

transform agrarian China into an industrialized country with disastrous results for people and land. Mao's unrealistic goals for

agricultural production

Agriculture encompasses crop and livestock production, aquaculture, and forestry for food and non-food products. Agriculture was a key factor in the rise of sedentary human civilization, whereby farming of domesticated species created food ...

went unfulfilled because of poor planning and realization, which aggravated rural starvation and increased the number of deaths caused by the

Great Chinese Famine, which resulted from three years of drought and poor weather. An estimated 30 million Chinese people starved to death, more than any other famine in recorded history.

Mao and his government largely downplayed the deaths.

Socialist relations repaired

In 1954, Soviet first secretary

Nikita Khrushchev

Nikita Sergeyevich Khrushchev (– 11 September 1971) was the General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1953 to 1964 and the Premier of the Soviet Union, Chai ...

repaired relations between the USSR and the PRC with trade agreements, a formal acknowledgement of Stalin's economic unfairness to the PRC, fifteen industrial-development projects, and exchanges of technicians (c. 10,000) and political advisors (c. 1,500), whilst Chinese labourers were sent to fill shortages of manual workers in

Siberia

Siberia ( ; , ) is an extensive geographical region comprising all of North Asia, from the Ural Mountains in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east. It has formed a part of the sovereign territory of Russia and its predecessor states ...

. Despite this, Mao and Khrushchev disliked each other, both personally and ideologically.

However, by 1955, consequent to Khrushchev's having repaired Soviet relations with Mao and the Chinese, 60% of the PRC's exports went to the USSR, by way of the

five-year plans of China

The Five-Year Plans () are a series of social and economic development initiatives issued by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) since 1953 in the People's Republic of China. Since 1949, the CCP has shaped the economy of China, Chinese economy thro ...

begun in 1953.

Discontents of de-Stalinization

In early 1956, Sino-Soviet relations began deteriorating, following Khrushchev's

de-Stalinization

De-Stalinization () comprised a series of political reforms in the Soviet Union after Death and state funeral of Joseph Stalin, the death of long-time leader Joseph Stalin in 1953, and Khrushchev Thaw, the thaw brought about by ascension of Nik ...

of the USSR, which he initiated with the speech ''

On the Cult of Personality and its Consequences

"On the Cult of Personality and Its Consequences" () was a report by Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev, First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, made to the 20th Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union on 25 Febr ...

'' that criticized

Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Dzhugashvili; 5 March 1953) was a Soviet politician and revolutionary who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until Death and state funeral of Joseph Stalin, his death in 1953. He held power as General Secret ...

and

Stalinism

Stalinism (, ) is the Totalitarianism, totalitarian means of governing and Marxism–Leninism, Marxist–Leninist policies implemented in the Soviet Union (USSR) from History of the Soviet Union (1927–1953), 1927 to 1953 by dictator Jose ...

– especially the

Great Purge

The Great Purge, or the Great Terror (), also known as the Year of '37 () and the Yezhovshchina ( , ), was a political purge in the Soviet Union that took place from 1936 to 1938. After the Assassination of Sergei Kirov, assassination of ...

of Soviet society, of the rank-and-file of the

Soviet Armed Forces

The Armed Forces of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, also known as the Armed Forces of the Soviet Union, the Red Army (1918–1946) and the Soviet Army (1946–1991), were the armed forces of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republi ...

, and of the

Communist Party of the Soviet Union

The Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU),. Abbreviated in Russian as КПСС, ''KPSS''. at some points known as the Russian Communist Party (RCP), All-Union Communist Party and Bolshevik Party, and sometimes referred to as the Soviet ...

(CPSU). In light of de-Stalinization, the CPSU's changed ideological orientation – from Stalin's confrontation of the West to Khrushchev's

peaceful coexistence

Peaceful coexistence () was a theory, developed and applied by the Soviet Union at various points during the Cold War in the context of primarily Marxist–Leninist foreign policy and adopted by Soviet-dependent socialist states, according to wh ...

with it – posed problems of ideological credibility and political authority for Mao, who had emulated Stalin's style of leadership and practical application of Marxism–Leninism in the development of

socialism with Chinese characteristics

Socialism with Chinese characteristics (; ) is a set of political theories and policies of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) that are seen by their proponents as representing Marxism adapted to Chinese circumstances.

The term was first establ ...

and the PRC as a country.

The

Hungarian Revolution of 1956

The Hungarian Revolution of 1956 (23 October – 4 November 1956; ), also known as the Hungarian Uprising, was an attempted countrywide revolution against the government of the Hungarian People's Republic (1949–1989) and the policies caused by ...

against the rule of Moscow was a severe political concern for Mao, because it had required military intervention to suppress, and its occurrence weakened the political legitimacy of the Communist Party to be in government. In response to that discontent among the European members of the Eastern Bloc, the Chinese Communist Party denounced the USSR's de-Stalinization as

revisionism, and reaffirmed the Stalinist ideology, policies, and practices of Mao's government as the correct course for achieving socialism in China. This event, indicating Sino-Soviet divergences of Marxist–Leninist practice and interpretation, began fracturing "monolithic communism" — the Western perception of absolute ideological unity in the Eastern Bloc.

From Mao's perspective, the success of the Soviet foreign policy of peaceful coexistence with the West would geopolitically isolate the PRC; whilst the Hungarian Revolution indicated the possibility of revolt in the PRC, and in China's sphere of influence. To thwart such discontent, Mao launched in 1956 the

Hundred Flowers Campaign of political liberalization – the freedom of speech to criticize government, the bureaucracy, and the CCP publicly. However, the campaign proved too successful when

blunt criticism of Mao was voiced. Consequent to the relative freedoms of the de-Stalinized USSR, Mao retained the Stalinist model of Marxist–Leninist economy, government, and society.

Ideological differences between Mao and Khrushchev compounded the insecurity of the new communist leader in China. Following the Chinese civil war, Mao was especially sensitive to ideological shifts that might undermine the CCP. In an era saturated by this form of ideological instability, Khrushchev's anti-Stalinism was particularly impactful to Mao. Mao saw himself as a descendent in a long Marxist–Leninist lineage of which Stalin was the most recent figurehead. Chinese leaders began to associate Stalin's successor with anti-party elements within China. Khrushchev was pinned as a revisionist. Popular sentiment within China regarded Khrushchev as a representative of the upper-class, and Chinese Marxist-Leninists viewed the leader as a blight on the communist project. While the two nations had significant ideological similarities, domestic instability drove a wedge between the nations as they began to adopt different visions of communism following the death of Stalin in 1953.

Popular sentiment within China changed as Khrushchev's policies changed. Stalin had accepted that the USSR would carry much of the economic burden of the Korean War, but, when Khrushchev came to power, he created a repayment plan under which the PRC would reimburse the Soviet Union within an eight-year period. However, China was experiencing significant food shortages at this time, and, when grain shipments were routed to the Soviet Union instead of feeding the Chinese public, faith in the Soviets plummeted. These policy changes were interpreted as Khrushchev's abandonment of the communist project and the nations' shared identity as Marxist-Leninists. As a result, Khrushchev became Mao's scapegoat during China's food crisis.

Chinese radicalization and distrust

In the first half of 1958, Chinese domestic politics developed an anti-Soviet tone from the ideological disagreement over de-Stalinization and the radicalization that preceded the

Great Leap Forward

The Great Leap Forward was an industrialization campaign within China from 1958 to 1962, led by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). Party Chairman Mao Zedong launched the campaign to transform the country from an agrarian society into an indu ...

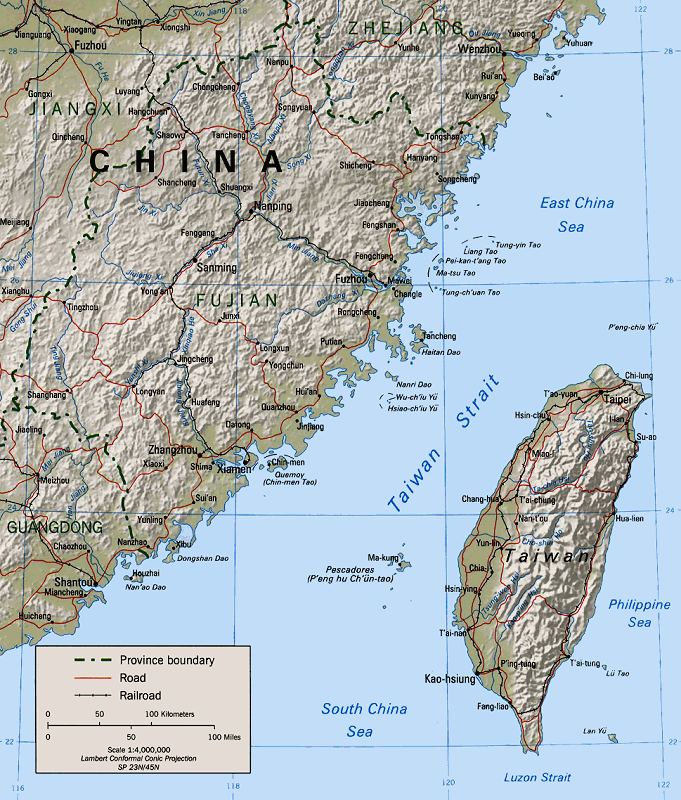

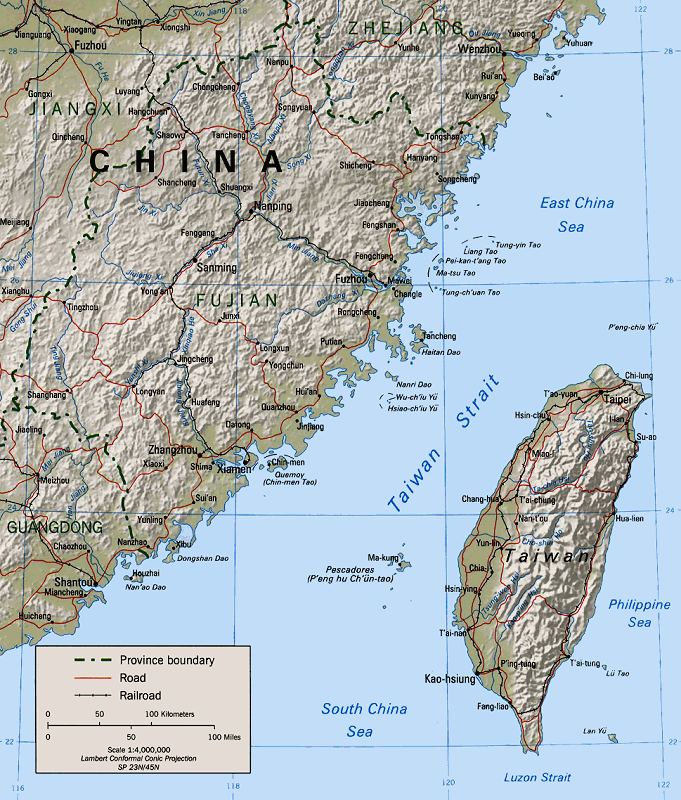

. It coincided with greater Chinese sensitivity over matters of sovereignty and control over foreign policy - particularly where Taiwan was concerned. The result was a growing Chinese reluctance to cooperate with the Soviet Union. The deterioration of the relationship manifested throughout the year.

In April, the Soviets proposed the construction of a joint radio transmitter. China rejected it after counter-proposing that the transmitter be Chinese owned and that Soviet usage be limited to wartime. A similar Soviet proposal in July was also rejected. In June, China requested Soviet assistance to develop nuclear attack submarines. The following month, the Soviets proposed the construction of a joint strategic submarine fleet, but the proposal as delivered failed to mention the type of submarine. The proposal was strongly rejected by Mao under the belief that the Soviet wanted to control China's coast and submarines. Khrushchev secretly visited Beijing in early August in an unsuccessful attempt to salvage the proposal; Mao was in an ideological furor and would not accept. The meeting ended with an agreement to construct the previously rejected radio station with Soviet loans.

Further damage was caused by the

Second Taiwan Strait Crisis

The Second Taiwan Strait Crisis, also known as the 1958 Taiwan Strait Crisis, was a conflict between the People's Republic of China (PRC) and the Taiwan, Republic of China (ROC). The PRC shelled the islands of Kinmen (Quemoy) and the Matsu Is ...

toward the end of August. China did not notify or consult the Soviet Union before initiating the conflict, contradicting China's previous desire to share information for foreign affairs and violating - at least the spirit - the Sino-Soviet friendship treaty. This may have been partially in response to what the Chinese viewed as the timid Soviet response to the West in the

1958 Lebanon crisis and

1958 Iraqi coup d'état

The 14 July Revolution, also known as the 1958 Iraqi military coup, was a ''coup d'état'' that took place on 14 July 1958 in Iraq, resulting in the toppling of Faisal II of Iraq, King Faisal II and the overthrow of the Hashemites, Hashemite- ...

. The Soviets opted to publicly support China at the end of August, but became concerned when the US replied with veiled threats of nuclear war in early September and mixed-messaging from the Chinese. China stated that its goal was the resumption of ambassadorial talks that had started after the

First Taiwan Strait Crisis while simultaneously framing the crisis as the start of a nuclear war with the capitalist bloc.

Chinese nuclear brinkmanship was a threat to peaceful coexistence. The crisis and ongoing nuclear disarmament talks with the US helped to convince the Soviets to renege on its 1957 commitment to deliver a model nuclear bomb to China. By this time, the Soviets had already helped create the foundations of China's nuclear weapons program.

Mao's nuclear-war remarks and two Chinas

Throughout the 1950s, Khrushchev maintained positive Sino-Soviet relations with foreign aid, especially nuclear technology for the Chinese atomic bomb project,

Project 596

Project 596 (Miss Qiu, , as the callsign; Chic-1 by the US intelligence agencies) was the first nuclear weapons Nuclear testing, test conducted by the People's Republic of China, detonated on 16 October 1964, at the Lop Nur test site. It was a ura ...

. However, political tensions persisted because the economic benefits of the USSR's peaceful-coexistence policy voided the belligerent PRC's geopolitical credibility among the nations under Chinese hegemony, especially after a failed PRC–US rapprochement. In the Chinese sphere of influence, that Sino-American diplomatic failure and the presence of

US nuclear weapons in Taiwan justified Mao's confrontational foreign policies with Taiwan (

Republic of China

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is a country in East Asia. The main geography of Taiwan, island of Taiwan, also known as ''Formosa'', lies between the East China Sea, East and South China Seas in the northwestern Pacific Ocea ...

).

According to various sources including official CCP publications, at the

1957 International Meeting of Communist and Workers Parties in Moscow, Mao Zedong made some controversial remarks on nuclear wars, saying that "I'm not afraid of nuclear war. There are 2.7 billion people in the world; it doesn't matter if some are killed. China has a population of 600 million; even if half of them are killed, there are still 300 million people left."

His remarks shocked many people, and according to the recollection of Khrushchev, "the audience was dead silent".

A number of Communist leaders, including

Antonín Novotný

Antonín Josef Novotný (; 10 December 1904 – 28 January 1975) was a Czechoslovak politician who served as the President of Czechoslovakia from 1957 to 1968, and as First Secretary of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia from 1953 to 1968. ...

,

Władysław Gomułka

Władysław Gomułka (; 6 February 1905 – 1 September 1982) was a Polish Communist politician. He was the ''de facto'' leader of Polish People's Republic, post-war Poland from 1947 until 1948, and again from 1956 to 1970.

Born in 1905 in ...

and

Shmuel Mikunis, expressed concerns after the meeting, eventually aligning themselves with the Soviet due to the combativeness of Mao's policies.

Novotný, then

First Secretary of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia

The Communist Party of Czechoslovakia (Czech language, Czech and Slovak language, Slovak: ''Komunistická strana Československa'', KSČ) was a communist and Marxism–Leninism, Marxist–Leninist political party in Czechoslovakia that existed b ...

, complained that "Mao Zedong says he is prepared to lose 300 million people out of a population of 600 million. What about us? We have only twelve million people in

Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia ( ; Czech language, Czech and , ''Česko-Slovensko'') was a landlocked country in Central Europe, created in 1918, when it declared its independence from Austria-Hungary. In 1938, after the Munich Agreement, the Sudetenland beca ...

."

Mao had reportedly said similar things in 1956 when meeting with a delegation of journalists from

Yugoslavia

, common_name = Yugoslavia

, life_span = 1918–19921941–1945: World War II in Yugoslavia#Axis invasion and dismemberment of Yugoslavia, Axis occupation

, p1 = Kingdom of SerbiaSerbia

, flag_p ...

, and in 1958 at the second meeting of the

8th National Congress of the Chinese Communist Party. In 1963, the Chinese government issued a statement, calling the quote of "300 million people" was a slander from the Soviet Union.

In late 1958, the CCP revived Mao's guerrilla-period

cult of personality

A cult of personality, or a cult of the leader,Cas Mudde, Mudde, Cas and Kaltwasser, Cristóbal Rovira (2017) ''Populism: A Very Short Introduction''. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 63. is the result of an effort which is made to create ...

to portray ''Chairman Mao'' as the charismatic, visionary leader solely qualified to control the policy, administration, and popular mobilization required to realize the Great Leap Forward to industrialize China. Moreover, to the Eastern Bloc, Mao portrayed the PRC's warfare with Taiwan and the accelerated modernization of the Great Leap Forward as Stalinist examples of Marxism–Leninism adapted to Chinese conditions. These circumstances allowed ideological Sino-Soviet competition, and Mao publicly criticized Khrushchev's economic and foreign policies as deviations from Marxism–Leninism.

Onset of the disputes

To Mao, the events of the 1958–1959 period indicated that Khrushchev was politically untrustworthy as an orthodox Marxist. In 1959, First Secretary Khrushchev met with US President

Dwight Eisenhower

Dwight David "Ike" Eisenhower (born David Dwight Eisenhower; October 14, 1890 – March 28, 1969) was the 34th president of the United States, serving from 1953 to 1961. During World War II, he was Supreme Commander of the Allied Expeditionar ...

to decrease US-Soviet geopolitical tensions. To that end, the USSR: (i) reneged an agreement for technical aid to develop

Project 596

Project 596 (Miss Qiu, , as the callsign; Chic-1 by the US intelligence agencies) was the first nuclear weapons Nuclear testing, test conducted by the People's Republic of China, detonated on 16 October 1964, at the Lop Nur test site. It was a ura ...

, and (ii) sided with India in the

Sino-Indian War

The Sino–Indian War, also known as the China–India War or the Indo–China War, was an armed conflict between China and India that took place from October to November 1962. It was a military escalation of the Sino–Indian border dispu ...

. Each US-Soviet collaboration offended Mao and he perceived Khrushchev as an opportunist who had become too tolerant of the West. The CCP said that the CPSU concentrated too much on "Soviet–US co-operation for the domination of the world", with geopolitical actions that contradicted Marxism–Leninism.

The final face-to-face meeting between Mao and Khruschev took place on 2 October 1959, when Khrushchev visited Beijing to mark the 10th anniversary of the Chinese Revolution. By this point relations had deteriorated to the level where the Chinese were going out of their way to humiliate the Soviet leader - for example, there was no honour guard to greet him, no Chinese leader gave a speech, and when Khrushchev insisted on giving a speech of his own, no microphone was provided. The speech in question would turn out to contain praise of the US President Eisenhower, whom Khrushchev had recently met, obviously an intentional insult to Communist China. The leaders of the two Socialist states would not meet again for the next 30 years.

Khrushchev's criticism of Albania at the 22nd CPSU Congress

In June 1960, at the zenith of de-Stalinization, the USSR denounced the

People's Republic of Albania

The People's Socialist Republic of Albania, () was the Marxist-Leninist state that existed in Albania from 10 January 1946 to the 29 April 1991. Originally founded as the People's Republic of Albania from 1946 to 1976, it was governed by the P ...

as a politically backward country for retaining Stalinism as government and model of socialism. In turn, Bao Sansan said that the CCP's message to the cadres in China was:

"When Khrushchev stopped Russian aid to Albania, Hoxha said to his people: 'Even if we have to eat the roots of grass to live, we won't take anything from Russia.' China is not guilty of chauvinism

Chauvinism ( ) is the unreasonable belief in the superiority or dominance of one's own group or people, who are seen as strong and virtuous, while others are considered weak, unworthy, or inferior. The ''Encyclopaedia Britannica'' describes it ...

, and immediately sent food to our brother country."

During his opening speech at the CPSU's

22nd Party Congress on 17 October 1961 in Moscow, Khrushchev once again criticized Albania as a politically backward state and the

Albanian Party of Labour as well as its leadership, including

Enver Hoxha

Enver Halil Hoxha ( , ; ; 16 October 190811 April 1985) was an Albanian communist revolutionary and politician who was the leader of People's Socialist Republic of Albania, Albania from 1944 until his death in 1985. He was the Secretary (titl ...

, for refusing to support reforms against Stalin's legacy, in addition to their criticism of

rapprochement with Yugoslavia, leading to the

Soviet–Albanian split. In response to this rebuke, on the 19 October the delegation representing China at the Party Congress led by

Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai

Zhou Enlai ( zh, s=周恩来, p=Zhōu Ēnlái, w=Chou1 Ên1-lai2; 5 March 1898 – 8 January 1976) was a Chinese statesman, diplomat, and revolutionary who served as the first Premier of the People's Republic of China from September 1954 unti ...

sharply criticised Moscow's stance towards Tirana:

"We hold that should a dispute or difference unfortunately arise between fraternal parties or fraternal countries, it should be resolved patiently in the spirit of proletarian internationalism

Proletarian internationalism, sometimes referred to as international socialism, is the perception of all proletarian revolutions as being part of a single global class struggle rather than separate localized events. It is based on the theory th ...

and according to the principles of equality and of unanimity through consultation. Public, one-sided censure of any fraternal party does not help unity and is not helpful in resolving problems. To bring a dispute between fraternal parties or fraternal countries into the open in the face of the enemy cannot be regarded as a serious Marxist–Leninist attitude."

Subsequently, on 21 October, Zhou visited the

Lenin Mausoleum (then still entombing Stalin's body), laying two wreaths at the base of the site, one of which read "Dedicated to the great Marxist, Comrade Stalin". On 23 October, the Chinese delegation left Moscow for Beijing early, before the Congress' conclusion; within days, Khrushchev had Stalin's body removed from the mausoleum.

Mao, Khrushchev, and the US

In 1960, Mao expected Khrushchev to deal aggressively with US President

Dwight D. Eisenhower

Dwight David "Ike" Eisenhower (born David Dwight Eisenhower; October 14, 1890 – March 28, 1969) was the 34th president of the United States, serving from 1953 to 1961. During World War II, he was Supreme Commander of the Allied Expeditionar ...

by holding him to account for the USSR having

shot down a U-2 spy plane, the

CIA's photographing of military bases in the USSR; aerial espionage that the US said had been discontinued. In Paris, at the

Four Powers Summit meeting, Khrushchev demanded and failed to receive Eisenhower's apology for the CIA's continued aerial espionage of the USSR. In China, Mao and the CCP interpreted Eisenhower's refusal to apologize as disrespectful of the national sovereignty of socialist countries, and held political rallies aggressively demanding Khrushchev's military confrontation with US aggressors; without such decisive action, Khrushchev lost face with the PRC.

In the Romanian capital of

Bucharest

Bucharest ( , ; ) is the capital and largest city of Romania. The metropolis stands on the River Dâmbovița (river), Dâmbovița in south-eastern Romania. Its population is officially estimated at 1.76 million residents within a greater Buc ...

, at the

International Meeting of Communist and Workers Parties

The International Meeting of Communist and Workers' Parties (IMCWP) is an annual conference attended by communist and workers' parties from several countries. It originated in 1998 when the Communist Party of Greece (KKE) invited communist an ...

(November 1960), Mao and Khrushchev respectively attacked the Soviet and the Chinese interpretations of

Marxism-Leninism as the wrong road to world socialism in the USSR and in China. Mao said that Khrushchev's emphases on consumer goods and material plenty would make the Soviets ideologically soft and un-revolutionary, to which Khrushchev replied: "If we could promise the people nothing, except revolution, they would scratch their heads and say: 'Isn't it better to have good goulash?

Ho Chi Minh's attempts to defuse the split

In 1960, Ho Chi Minh, uniquely among Marxist-Leninist world leaders, attempted to mediate the growing Sino-Soviet tensions, staking his own personal reputation by doing so. On 14 August 1960, Ho attended a meeting in

Sochi

Sochi ( rus, Сочи, p=ˈsotɕɪ, a=Ru-Сочи.ogg, from – ''seaside'') is the largest Resort town, resort city in Russia. The city is situated on the Sochi (river), Sochi River, along the Black Sea in the North Caucasus of Souther ...

with Khrushchev,

Władysław Gomułka

Władysław Gomułka (; 6 February 1905 – 1 September 1982) was a Polish Communist politician. He was the ''de facto'' leader of Polish People's Republic, post-war Poland from 1947 until 1948, and again from 1956 to 1970.

Born in 1905 in ...

,

Yumjaagiin Tsedenbal, and

Gheorghe Gheorghiu-Dej

Gheorghe Gheorghiu-Dej (; 8 November 1901 – 19 March 1965) was a Romanian politician. He was the first Socialist Republic of Romania, Communist leader of Romania from 1947 to 1965, serving as first secretary of the Romanian Communist Party ...

, the purpose of which was to discuss the growing tensions with China. Khrushchev expressed reservations about Mao's growing nationalism, which he perceived as similar to the racial, pan-Asian nationalist propaganda of

Imperial Japan

The Empire of Japan, also known as the Japanese Empire or Imperial Japan, was the Japanese nation state that existed from the Meiji Restoration on January 3, 1868, until the Constitution of Japan took effect on May 3, 1947. From Japan–Kor ...

. Later, when Ho met with Deng Xiaoping, Deng used the information he had received from Ho to denounce the Soviets and accuse them of spreading

Yellow Peril. Although Ho was able to foster dialogue between the two states, the limited influence of North Vietnam within the Marxist-Leninist world resulted in Ho failing to prevent the split.

Personal attacks and USSR technical support ceased

In the 1960s, public displays of acrimonious quarrels about Marxist–Leninist doctrine characterized relations between hardline Stalinist Chinese and post-Stalinist Soviet Communists. At the

Romanian Communist Party Congress, the CCP's senior officer

Peng Zhen

Peng Zhen (pronounced ; October 12, 1902 – April 26, 1997) was a Chinese politician and leading member of the Chinese Communist Party. He led the party organization in Beijing following the victory of the Communists in the Chinese Civil War i ...

quarrelled with Khrushchev, after the latter had insulted Mao as being a Chinese nationalist, a geopolitical adventurist, and an

ideological deviationist from Marxism–Leninism. In turn, Peng insulted Khrushchev as a

revisionist whose régime showed him to be a "patriarchal, arbitrary, and tyrannical" ruler. In the event, Khrushchev denounced the PRC with 80 pages of criticism to the congress of the PRC.

In response to the insults, Khrushchev withdrew 1,400 Soviet technicians from the PRC, which cancelled some 200 joint scientific projects. According to Chinese records, the Soviet Union suddenly withdrew 1390 technicians and ended 600 contracts with PRC in 1960. In response, Mao justified his belief that Khrushchev had somehow caused China's great economic failures and the famines that occurred in the period of the Great Leap Forward. Nonetheless, the PRC and the USSR remained pragmatic allies, which allowed Mao to alleviate famine in China and to resolve Sino-Indian border disputes. To Mao, Khrushchev had lost political authority and ideological credibility, because his US-Soviet ''

détente'' had resulted in successful military (aerial) espionage against the USSR and public confrontation with an unapologetic capitalist enemy. Khrushchev's miscalculation of person and circumstance voided US-Soviet diplomacy at the

Four Powers Summit in Paris.

Monolithic communism fractured

In late 1961, at the

22nd Congress of the CPSU, the PRC and the USSR revisited their doctrinal disputes about the orthodox interpretation and application of Marxism–Leninism. In December 1961, the USSR broke diplomatic relations with Albania, which escalated the Sino-Soviet disputes from the political-party level to the national-government level.

During the

Yi–Ta incident from March to May 1962, over 60,000 Chinese citizens, mostly ethnic Kazakhs driven in part by uncertainty over the Sino-Soviet split, crossed the border from

Xinjiang

Xinjiang,; , SASM/GNC romanization, SASM/GNC: Chinese postal romanization, previously romanized as Sinkiang, officially the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region (XUAR), is an Autonomous regions of China, autonomous region of the China, People' ...

into

Soviet Kazakhstan. In late 1962, the PRC broke relations with the USSR because Khrushchev did not go to war with the US over the

Cuban Missile Crisis

The Cuban Missile Crisis, also known as the October Crisis () in Cuba, or the Caribbean Crisis (), was a 13-day confrontation between the governments of the United States and the Soviet Union, when American deployments of Nuclear weapons d ...

. Regarding that Soviet loss-of-face, Mao said that "Khrushchev has moved from adventurism to capitulationism" with a negotiated, bilateral, military stand-down. Khrushchev replied that Mao's belligerent foreign policies would lead to an East–West nuclear war. For the Western powers, the averted atomic war threatened by the Cuban Missile Crisis made

nuclear disarmament

Nuclear disarmament is the act of reducing or eliminating nuclear weapons. Its end state can also be a nuclear-weapons-free world, in which nuclear weapons are completely eliminated. The term ''denuclearization'' is also used to describe the pro ...

their political priority. To that end, the US, the UK, and the USSR agreed to the

Partial Nuclear Test Ban Treaty

The Partial Test Ban Treaty (PTBT), formally known as the 1963 Treaty Banning Nuclear Weapon Tests in the Atmosphere, in Outer Space and Under Water, prohibited all nuclear weapons testing, test detonations of nuclear weapons except for those co ...

in 1963, which formally forbade

nuclear-detonation tests in the

Earth's atmosphere

The atmosphere of Earth is composed of a layer of gas mixture that surrounds the Earth's planetary surface (both lands and oceans), known collectively as air, with variable quantities of suspended aerosols and particulates (which create weathe ...

, in

outer space, and

under water – yet did allow the underground testing and detonation of atomic bombs. In that time, the PRC's nuclear-weapons program,

Project 596

Project 596 (Miss Qiu, , as the callsign; Chic-1 by the US intelligence agencies) was the first nuclear weapons Nuclear testing, test conducted by the People's Republic of China, detonated on 16 October 1964, at the Lop Nur test site. It was a ura ...

, was nascent, and Mao perceived the test-ban treaty as the nuclear powers' attempt to thwart the PRC's becoming a nuclear superpower.

Between 6 and 20 July 1963, a series of Soviet-Chinese negotiations were held in Moscow. However, both sides maintained their own ideological views and, therefore, negotiations failed. In March 1964, the

Romanian Workers' Party

The Romanian Communist Party ( ; PCR) was a communist party in Romania. The successor to the pro-Bolshevik wing of the Socialist Party of Romania, it gave an ideological endorsement to a communist revolution that would replace the social syst ...

publicly announced the intention of the Bucharest authorities to mediate the Sino-Soviet conflict. In reality, however, the Romanian mediation approach represented only a pretext for forging a Sino-Romanian rapprochement, without arousing the Soviets' suspicions.

Romania was neutral in the Sino-Soviet split. Its neutrality along with being the small communist country with the most influence in global affairs enabled Romania to be recognized by the world as the "third force" of the communist world. Romania's independence - achieved in the early 1960s through its

freeing from its Soviet satellite status - was tolerated by Moscow because Romania was surrounded by socialist states and because its ruling party was not going to abandon communism.

North Korea

North Korea, officially the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (DPRK), is a country in East Asia. It constitutes the northern half of the Korea, Korean Peninsula and borders China and Russia to the north at the Yalu River, Yalu (Amnok) an ...

under

Kim Il Sung

Kim Il Sung (born Kim Song Ju; 15 April 1912 – 8 July 1994) was a North Korean politician and the founder of North Korea, which he led as its first Supreme Leader (North Korean title), supreme leader from North Korea#Founding, its establishm ...

also remained neutral because of its strategic status after the

Korean War

The Korean War (25 June 1950 – 27 July 1953) was an armed conflict on the Korean Peninsula fought between North Korea (Democratic People's Republic of Korea; DPRK) and South Korea (Republic of Korea; ROK) and their allies. North Korea was s ...

, although it later moved more decisively towards the USSR after

Deng Xiaoping

Deng Xiaoping also Romanization of Chinese, romanised as Teng Hsiao-p'ing; born Xiansheng (). (22 August 190419 February 1997) was a Chinese statesman, revolutionary, and political theorist who served as the paramount leader of the People's R ...

's

reform and opening up.

The

Italian Communist Party

The Italian Communist Party (, PCI) was a communist and democratic socialist political party in Italy. It was established in Livorno as the Communist Party of Italy (, PCd'I) on 21 January 1921, when it seceded from the Italian Socialist Part ...

(PCI), one of the largest and most politically influential communist parties in Western Europe, adopted an ambivalent stance towards Mao's split from the USSR. Although the PCI chastised Mao for breaking the previous global unity of socialist states and criticised the Cultural Revolution brought about by him, it simultaneously applauded and heaped praise on him for the People's Republic of China's enormous assistance to

North Vietnam

North Vietnam, officially the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (DRV; ; VNDCCH), was a country in Southeast Asia from 1945 to 1976, with sovereignty fully recognized in 1954 Geneva Conference, 1954. A member of the communist Eastern Bloc, it o ...

in its war against

South Vietnam

South Vietnam, officially the Republic of Vietnam (RVN; , VNCH), was a country in Southeast Asia that existed from 1955 to 1975. It first garnered Diplomatic recognition, international recognition in 1949 as the State of Vietnam within the ...

and the United States.

As a Marxist–Leninist, Mao was much angered that Khrushchev did not go to war with the US over their failed

Bay of Pigs Invasion

The Bay of Pigs Invasion (, sometimes called or after the Playa Girón) was a failed military landing operation on the southwestern coast of Cuba in April 1961 by the United States of America and the Cuban Democratic Revolutionary Front ...

and the

United States embargo against Cuba

The United States embargo against Cuba is the only active embargo within the United States which has prevented U.S. businesses from conducting trade or commerce with Cuban interests since 1958. Modern Cuba–United States relations, diplomatic ...

of continual economic and agricultural sabotage. For the Eastern Bloc, Mao addressed those Sino-Soviet matters in "Nine Letters" critical of Khrushchev and his leadership of the USSR. Moreover, the break with the USSR allowed Mao to reorient the development of the PRC with formal relations (diplomatic, economic, political) with the countries of Asia, Africa, and Latin America.

Formal and informal statements

In the 1960s, the Sino-Soviet split allowed only written communications between the PRC and the USSR, in which each country supported their geopolitical actions with formal statements of Marxist–Leninist ideology as the true road to

world communism

World communism, also known as global communism or international communism, is a form of communism placing emphasis on an international scope rather than being individual communist states. The long-term goal of world communism is an unlimited ...

, which is the

general line of the party. In June 1963, the PRC published ''The Chinese Communist Party's Proposal Concerning the General Line of the International Communist Movement'', to which the USSR replied with the ''Open Letter of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union''; each ideological stance perpetuated the Sino-Soviet split. In 1964, Mao said that, in light of the Chinese and Soviet differences about the interpretation and practical application of Orthodox Marxism, a counter-revolution had occurred and re-established capitalism in the USSR; consequently, following Soviet suit, the

Warsaw Pact

The Warsaw Pact (WP), formally the Treaty of Friendship, Co-operation and Mutual Assistance (TFCMA), was a Collective security#Collective defense, collective defense treaty signed in Warsaw, Polish People's Republic, Poland, between the Sovi ...

countries broke relations with the PRC.

In late 1964, after Nikita Khrushchev had been deposed, Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai met with the new Soviet leaders, First Secretary

Leonid Brezhnev

Leonid Ilyich Brezhnev (19 December 190610 November 1982) was a Soviet politician who served as the General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1964 until Death and state funeral of Leonid Brezhnev, his death in 1982 as w ...

and Premier

Alexei Kosygin

Alexei Nikolayevich Kosygin (–18 December 1980) was a Soviet people, Soviet statesman during the Cold War. He served as the Premier of the Soviet Union from 1964 to 1980 and, alongside General Secretary Leonid Brezhnev, was one of its most ...

, but their ideological differences proved a diplomatic impasse to renewed economic relations. The Soviet defense minister's statement damaged the prospects of improved Sino-Soviet relations. Historian Daniel Leese noted that improvement of the relations "that had seemed possible after Khrushchev's fall evaporated after the Soviet minister of defense,

Rodion Malinovsky

Rodion Yakovlevich Malinovsky (; ; – 31 March 1967) was a Soviet military commander and Marshal of the Soviet Union. He served as Minister of Defence of the Soviet Union from 1957 to 1967, during which he oversaw the strengthening of the Sov ...

... approached Chinese Marshal

He Long, member of the Chinese delegation to Moscow, and asked when China would finally get rid of Mao like the

CPSU

The Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU),. Abbreviated in Russian as КПСС, ''KPSS''. at some points known as the Russian Communist Party (RCP), All-Union Communist Party and Bolshevik Party, and sometimes referred to as the Soviet ...

had disposed of Khrushchev." Back in China, Zhou reported to Mao that Brezhnev's Soviet government retained the policy of peaceful coexistence which Mao had denounced as "

Khrushchevism without Khrushchev"; despite the change of leadership, the Sino-Soviet split remained open. At the

Glassboro Summit Conference

The Glassboro Summit Conference, usually just called the Glassboro Summit, was the 23–25 June 1967 meeting of the heads of government of the United States and the Soviet Union— President Lyndon B. Johnson and Premier Alexei Kosygin, respecti ...

, between Kosygin and US President

Lyndon B. Johnson

Lyndon Baines Johnson (; August 27, 1908January 22, 1973), also known as LBJ, was the 36th president of the United States, serving from 1963 to 1969. He became president after the assassination of John F. Kennedy, under whom he had served a ...

, the PRC accused the USSR of betraying the peoples of the Eastern bloc countries. The official interpretation, by

Radio Peking, reported that US and Soviet politicians discussed "a great conspiracy, on a worldwide basis ... criminally selling the rights of the revolution of

heVietnam people,

f theArabs, as well as

hose ofAsian, African, and Latin-American peoples, to US imperialists".

Conflict

Cultural Revolution

To regain political supremacy in the PRC, Mao launched the

Cultural Revolution

The Cultural Revolution, formally known as the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution, was a Social movement, sociopolitical movement in the China, People's Republic of China (PRC). It was launched by Mao Zedong in 1966 and lasted until his de ...

in 1966 to counter the Soviet-style bureaucracies (personal-power-centres) that had become established in education, agriculture, and industrial management. Abiding Mao's proclamations for universal ideological orthodoxy, schools and universities closed throughout China when students organized themselves into politically radical

Red Guards

The Red Guards () were a mass, student-led, paramilitary social movement mobilized by Chairman Mao Zedong in 1966 until their abolition in 1968, during the first phase of the Cultural Revolution, which he had instituted.Teiwes

According to a ...

. Lacking a leader, a political purpose, and a social function, the ideologically discrete units of Red Guards soon degenerated into political factions, each of whom claimed to be more Maoist than the other factions.

In establishing the ideological orthodoxy presented in the

Little Red Book

''Quotations from Chairman Mao'' ( zh, s=毛主席语录, t=毛主席語錄, p=Máo Zhǔxí Yǔlù, commonly known as the "红宝书" zh, p=hóng bǎo shū during the Cultural Revolution), colloquially referred to in the English-speaking world ...

(''Quotations from Chairman Mao Tse-tung''), the political violence of the Red Guards provoked civil war in parts of China, known as the

violent struggle, which Mao suppressed with the

People's Liberation Army

The People's Liberation Army (PLA) is the military of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and the People's Republic of China (PRC). It consists of four Military branch, services—People's Liberation Army Ground Force, Ground Force, People's ...

(PLA), who imprisoned the fractious Red Guards. Moreover, when Red Guard factionalism occurred within the PLA – Mao's base of political power – he dissolved the Red Guards, and then reconstituted the CCP with the new generation of Maoists who had endured and survived the Cultural Revolution that

purge

In history, religion and political science, a purge is a position removal or execution of people who are considered undesirable by those in power from a government, another, their team leaders, or society as a whole. A group undertaking such an ...

d the "anti-communist" old generation from the party and from China.

[''The Columbia Encyclopedia'', Fifth Edition. Columbia University Press:1993. p. 696.]

As social engineering, the Cultural Revolution reasserted the political primacy of

Maoism

Maoism, officially Mao Zedong Thought, is a variety of Marxism–Leninism that Mao Zedong developed while trying to realize a socialist revolution in the agricultural, pre-industrial society of the Republic of China (1912–1949), Republic o ...

, but also stressed, strained, and broke the PRC's relations with the USSR and the West. The Soviet Union ridiculed and criticized Mao's Cultural Revolution fiercely, and some publications in USSR and Eastern Bloc also compared Mao meeting Red Guards on

Tiananmen

The Tiananmen , also Tian'anmen, is the entrance gate of the Forbidden City imperial palace complex and Imperial City in the center of Beijing, China. It is widely used as a national symbol.

First built in 1420 during the Ming dynasty, Ti ...

to

Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (20 April 1889 – 30 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was the dictator of Nazi Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his suicide in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the lea ...

giving speeches to his supporters. Geopolitically, despite their querulous "Maoism vs. Marxism–Leninism" disputes about interpretations and practical applications of Marxism–Leninism, the USSR and the PRC advised, aided, and supplied

North Vietnam

North Vietnam, officially the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (DRV; ; VNDCCH), was a country in Southeast Asia from 1945 to 1976, with sovereignty fully recognized in 1954 Geneva Conference, 1954. A member of the communist Eastern Bloc, it o ...

during the

Vietnam War

The Vietnam War (1 November 1955 – 30 April 1975) was an armed conflict in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia fought between North Vietnam (Democratic Republic of Vietnam) and South Vietnam (Republic of Vietnam) and their allies. North Vietnam w ...

, which Mao had defined as a peasant revolution against foreign imperialism. In socialist solidarity, the PRC allowed safe passage for the Soviet Union's ''matériel'' to North Vietnam to prosecute the war against the US-sponsored

Republic of Vietnam

South Vietnam, officially the Republic of Vietnam (RVN; , VNCH), was a country in Southeast Asia that existed from 1955 to 1975. It first garnered international recognition in 1949 as the State of Vietnam within the French Union, with it ...

, until 1968, after the Chinese withdrawal.

Siege of the Soviet embassy in Beijing

In August 1966 the Soviet Ministry of Foreign Affairs sent the first of several notes to the Chinese embassy in Moscow protesting aggressive Chinese behavior near the

Soviet embassy in Beijing. On January 25, 1967, the Chinese visiting the

Lenin Mausoleum on

Moscow

Moscow is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Russia by population, largest city of Russia, standing on the Moskva (river), Moskva River in Central Russia. It has a population estimated at over 13 million residents with ...

Red Square

Red Square ( rus, Красная площадь, Krasnaya ploshchad', p=ˈkrasnəjə ˈploɕːɪtʲ) is one of the oldest and largest town square, squares in Moscow, Russia. It is located in Moscow's historic centre, along the eastern walls of ...

jumped over a barrier and began chanting Mao quotes. Then one Chinese allegedly hit a Soviet woman, and a scuffle took place. After this incident new outrages against the Soviet embassy in Beijing began. The threat of physical danger caused the Soviets to evacuate women and children from their embassy in Beijing in February 1967. Even as the women and children were boarding the plane, they were harassed by hostile

Red Guards

The Red Guards () were a mass, student-led, paramilitary social movement mobilized by Chairman Mao Zedong in 1966 until their abolition in 1968, during the first phase of the Cultural Revolution, which he had instituted.Teiwes

According to a ...

.

Border conflict

In the late 1960s, the continual quarrelling between the CCP and the CPSU about the correct interpretations and applications of Marxism–Leninism escalated to small-scale warfare at the

Sino-Soviet border.

[Lüthi, Lorenz M. ''The Sino-Soviet split: Cold War in the Communist World'' (2008), p. 340.]

In 1966, for diplomatic resolution, the Chinese revisited the national matter of the Sino-Soviet border demarcated in the 19th century, but originally imposed upon the

Qing dynasty

The Qing dynasty ( ), officially the Great Qing, was a Manchu-led Dynasties of China, imperial dynasty of China and an early modern empire in East Asia. The last imperial dynasty in Chinese history, the Qing dynasty was preceded by the ...

by way of unequal treaties that annexed Chinese territory to the

Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire that spanned most of northern Eurasia from its establishment in November 1721 until the proclamation of the Russian Republic in September 1917. At its height in the late 19th century, it covered about , roughl ...

. Despite not asking the return of territory, the PRC asked the USSR to acknowledge formally and publicly that such an historic injustice against China (the 19th-century border) was dishonestly realized with the 1858

Treaty of Aigun

The Treaty of Aigun was an 1858 treaty between the Russian Empire and Yishan, official of the Qing dynasty of China. It established much of the modern border between the Russian Far East and China by ceding much of Manchuria (the ancestral h ...

and the 1860

Convention of Peking. The Soviet government ignored the matter.

In 1968, the

Soviet Army

The Soviet Ground Forces () was the land warfare service branch of the Soviet Armed Forces from 1946 to 1992. It was preceded by the Red Army.

After the Soviet Union ceased to exist in December 1991, the Ground Forces remained under th ...

had massed along the border with the PRC, especially at the

Xinjiang

Xinjiang,; , SASM/GNC romanization, SASM/GNC: Chinese postal romanization, previously romanized as Sinkiang, officially the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region (XUAR), is an Autonomous regions of China, autonomous region of the China, People' ...

frontier, in

north-west China, where the Soviets might readily induce the

Turkic peoples

Turkic peoples are a collection of diverse ethnic groups of West Asia, West, Central Asia, Central, East Asia, East, and North Asia as well as parts of Europe, who speak Turkic languages.. "Turkic peoples, any of various peoples whose members ...

into a separatist insurrection. In 1961, the USSR had stationed 12 divisions of soldiers and 200 aeroplanes at that border. By 1968, the Soviet Armed Forces had stationed six divisions of soldiers in

Outer Mongolia

Outer Mongolia was the name of a territory in the Manchu-led Qing dynasty of China from 1691 to 1911. It corresponds to the modern-day independent state of Mongolia and the Russian republic of Tuva. The historical region gained ''de facto'' ...

and 16 divisions, 1,200 aeroplanes, and 120 medium-range missiles at the Sino-Soviet border to confront 47 light divisions of the Chinese Army. By March 1969, the border confrontations

escalated, including fighting at the

Ussuri River

The Ussuri ( ; ) or Wusuli ( ) is a river that runs through Khabarovsk and Primorsky Krais, Russia and the southeast region of Northeast China in the province of Heilongjiang. It rises in the Sikhote-Alin mountain range, flowing north and for ...

, the

Zhenbao Island incident, and

Tielieketi.

After the border conflict, "spy wars" involving numerous espionage agents occurred on Soviet and Chinese territory through the 1970s. In 1972, the Soviet Union also

renamed placenames in the Russian Far East to the

Russian language

Russian is an East Slavic languages, East Slavic language belonging to the Balto-Slavic languages, Balto-Slavic branch of the Indo-European languages, Indo-European language family. It is one of the four extant East Slavic languages, and is ...

and

Russified toponyms, replacing the native and/or Chinese names.

Nuclear China with the US and the USSR

US strategy on China's nuclear development

In the early 1960s, the United States feared that a "nuclear China" would imbalance the bi-polar Cold War between the US and the USSR. To keep the PRC from achieving the geopolitical status of a nuclear power, the US administrations of both

John F. Kennedy and

Lyndon B. Johnson

Lyndon Baines Johnson (; August 27, 1908January 22, 1973), also known as LBJ, was the 36th president of the United States, serving from 1963 to 1969. He became president after the assassination of John F. Kennedy, under whom he had served a ...

considered ways either to sabotage or to attack directly the

Chinese nuclear program — aided either by

Republic of China

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is a country in East Asia. The main geography of Taiwan, island of Taiwan, also known as ''Formosa'', lies between the East China Sea, East and South China Seas in the northwestern Pacific Ocea ...

based in Taiwan or by the USSR. To avert nuclear war, Khrushchev refused the US offer to participate in a US-Soviet pre-emptive attack against the PRC.

To prevent the Chinese from building a nuclear bomb, the

United States Armed Forces

The United States Armed Forces are the Military, military forces of the United States. U.S. United States Code, federal law names six armed forces: the United States Army, Army, United States Marine Corps, Marine Corps, United States Navy, Na ...

recommended indirect measures, such as diplomacy and propaganda, and direct measures, such as infiltration and sabotage, an invasion by the Chinese Nationalists in Taiwan, maritime blockades, a South Korean invasion of North Korea, conventional air attacks against the nuclear production facilities, and dropping a nuclear bomb against a "selected CHICOM

hinese Communisttarget". On 16 October 1964, the PRC detonated their first nuclear bomb, a uranium-235

implosion-fission device,

["16 October 1964 – First Chinese nuclear test: CTBTO Preparatory Commission"](_blank)

. ''ctbto.org''. Retrieved 1 June 2017. with an explosive yield of 22

kiloton

TNT equivalent is a convention for expressing energy, typically used to describe the energy released in an explosion. A ton of TNT equivalent is a unit of energy defined by convention to be (). It is the approximate energy released in the det ...

s of TNT; and publicly acknowledged the USSR's technical assistance in realizing

Project 596

Project 596 (Miss Qiu, , as the callsign; Chic-1 by the US intelligence agencies) was the first nuclear weapons Nuclear testing, test conducted by the People's Republic of China, detonated on 16 October 1964, at the Lop Nur test site. It was a ura ...

.

Planned Soviet nuclear strike on China

According to declassified sources from both the PRC and the United States, the Soviet Union planned to launch a massive nuclear strike on China after the

Zhenbao Island incident in March 1969.

Soviet diplomat

Arkady Shevchenko

Arkady Nikolayevich Shevchenko (October 11, 1930 – February 28, 1998) was a Soviet Union, Soviet diplomat who was the highest-ranking Soviet official Eastern Bloc emigration and defection, to defect to the Western world, West.

Shevchen ...

also mentioned in his memoir that "the Soviet leadership had come close to using nuclear arms on China" with

Andrei Grechko