Sinibaldo Fieschi on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Pope Innocent IV (; – 7 December 1254), born Sinibaldo Fieschi, was head of the

Born in

Born in

The

The

The warlike tendencies of the Mongols also concerned the Pope, and in 1245, he issued bulls and sent a papal

The warlike tendencies of the Mongols also concerned the Pope, and in 1245, he issued bulls and sent a papal

Pope Innocent IV on Catholic Encyclopedia

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Innocent 04 1190s births 1254 deaths Clergy from Genoa Italian popes University of Parma alumni University of Bologna alumni Bishops of Albenga Christians of the Prussian Crusade Christians of the Second Swedish Crusade Popes 13th-century popes Fieschi family

Catholic Church

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

and ruler of the Papal States

The Papal States ( ; ; ), officially the State of the Church, were a conglomeration of territories on the Italian peninsula under the direct sovereign rule of the pope from 756 to 1870. They were among the major states of Italy from the 8th c ...

from 25 June 1243 to his death in 1254.

Fieschi was born in Genoa and studied at the universities of Parma

Parma (; ) is a city in the northern Italian region of Emilia-Romagna known for its architecture, Giuseppe Verdi, music, art, prosciutto (ham), Parmesan, cheese and surrounding countryside. With a population of 198,986 inhabitants as of 2025, ...

and Bologna

Bologna ( , , ; ; ) is the capital and largest city of the Emilia-Romagna region in northern Italy. It is the List of cities in Italy, seventh most populous city in Italy, with about 400,000 inhabitants and 150 different nationalities. Its M ...

. He was considered in his own day and by posterity as a fine canonist. On the strength of this reputation, he was called to the Roman Curia

The Roman Curia () comprises the administrative institutions of the Holy See and the central body through which the affairs of the Catholic Church are conducted. The Roman Curia is the institution of which the Roman Pontiff ordinarily makes use ...

by Pope Honorius III

Pope Honorius III (c. 1150 – 18 March 1227), born Cencio Savelli, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 18 July 1216 to his death. A canon at the Basilica di Santa Maria Maggiore, he came to hold a number of importa ...

. Pope Gregory IX

Pope Gregory IX (; born Ugolino di Conti; 1145 – 22 August 1241) was head of the Catholic Church and the ruler of the Papal States from 19 March 1227 until his death in 1241. He is known for issuing the '' Decretales'' and instituting the Pa ...

made him a cardinal and appointed him governor of the Ancona in 1235. Fieschi was elected pope in 1243 and took the name Innocent IV. He inherited an ongoing dispute over lands seized by the Holy Roman Emperor, and the following year he traveled to France to escape imperial plots against him in Rome. He returned to Rome in 1250 after the death of the Emperor Frederick II

Frederick II (, , , ; 26 December 1194 – 13 December 1250) was King of Sicily from 1198, King of Germany from 1212, King of Italy and Holy Roman Emperor from 1220 and King of Jerusalem from 1225. He was the son of Emperor Henry VI of the Ho ...

.

On 15 May 1252 he promulgated the bull ''Ad extirpanda

''Ad extirpanda'' ("To eradicate"; named for its Latin incipit) was a papal bull promulgated on Wednesday, May 15, 1252 by Pope Innocent IV which authorized under defined circumstances the use of torture by the Inquisition as a tool for interrog ...

'' authorizing torture against heretics, equated with ordinary criminals.

Early life

Born in

Born in Genoa

Genoa ( ; ; ) is a city in and the capital of the Italian region of Liguria, and the sixth-largest city in Italy. As of 2025, 563,947 people live within the city's administrative limits. While its metropolitan city has 818,651 inhabitan ...

(although some sources say Manarola

Manarola ( in the local dialect) is a small town, a frazione of the comune (municipality) of Riomaggiore, in the province of La Spezia, Liguria, Northern Italy. It is the second-smallest of the famous Cinque Terre towns frequented by tourist ...

) in an unknown year, Sinibaldo was the son of Beatrice Grillo and Ugo Fieschi, Count of Lavagna

Lavagna is a ''comune'' (municipality) in the Metropolitan City of Genoa, in the Italian region of Liguria.

History and culture

The village, unlike nearby Chiavari which has pre-Ancient Rome, Roman evidence, seems to have developed in Ancient ...

. The Fieschi

The House of Fieschi were an old Italian noble family from Genoa, Italy, from whom descend the Fieschi Ravaschieri Princes of Belmonte. Of ancient origin, they took their name from the progenitor ''Ugo Fliscus'', descendants of the counts of Lav ...

were a noble merchant family of Liguria

Liguria (; ; , ) is a Regions of Italy, region of north-western Italy; its Capital city, capital is Genoa. Its territory is crossed by the Alps and the Apennine Mountains, Apennines Mountain chain, mountain range and is roughly coextensive with ...

. Sinibaldo received his education at the universities of Parma

Parma (; ) is a city in the northern Italian region of Emilia-Romagna known for its architecture, Giuseppe Verdi, music, art, prosciutto (ham), Parmesan, cheese and surrounding countryside. With a population of 198,986 inhabitants as of 2025, ...

and Bologna

Bologna ( , , ; ; ) is the capital and largest city of the Emilia-Romagna region in northern Italy. It is the List of cities in Italy, seventh most populous city in Italy, with about 400,000 inhabitants and 150 different nationalities. Its M ...

and may have taught canon law

Canon law (from , , a 'straight measuring rod, ruler') is a set of ordinances and regulations made by ecclesiastical jurisdiction, ecclesiastical authority (church leadership) for the government of a Christian organization or church and its membe ...

, for a time, at Bologna. The fact is disputed, though, as others pointed out, there is no documentary evidence of his teaching position. From 1216 to 1227 he was a canon of the Cathedral of Parma

Parma Cathedral () is a Roman Catholic cathedral in Parma, Emilia-Romagna, dedicated to the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary. It is the episcopal seat of the Diocese of Parma. It is an important Italian Romanesque architecture, Romanesque ...

. He was considered one of the best canonists

Canon law (from , , a 'straight measuring rod, ruler') is a set of ordinances and regulations made by ecclesiastical authority (church leadership) for the government of a Christian organization or church and its members.

Canon law includes the ...

of his time, He wrote the ''Apparatus in quinque libros decretalium'', a commentary on papal decrees. He was called to serve Pope Honorius III

Pope Honorius III (c. 1150 – 18 March 1227), born Cencio Savelli, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 18 July 1216 to his death. A canon at the Basilica di Santa Maria Maggiore, he came to hold a number of importa ...

in the Roman Curia

The Roman Curia () comprises the administrative institutions of the Holy See and the central body through which the affairs of the Catholic Church are conducted. The Roman Curia is the institution of which the Roman Pontiff ordinarily makes use ...

where he rapidly rose through the hierarchy. He was ''Auditor causarum'', from 11 November 1226 to 30 May 1227. He was then quickly promoted to the office of Vice-Chancellor of the Holy Roman Church

Chancellor is an ecclesiastical title used by several quite distinct officials of some Christian churches. In some churches, the chancellor of a diocese is a lawyer who represents the church in legal matters.

Catholic Church

In the Catholic ...

(from 31 May to 23 September 1227), though he retained the office and the title for a time after he was named Cardinal.

Cardinal

While vice-Chancellor, Fieschi was soon createdCardinal-Priest

A cardinal is a senior member of the clergy of the Catholic Church. As titular members of the clergy of the Diocese of Rome, they serve as advisors to the pope, who is the bishop of Rome and the visible head of the worldwide Catholic Church. ...

of San Lorenzo in Lucina

The Minor Basilica of St. Lawrence in Lucina ( or simply ; ) is a Roman Catholic parish, titular church, and minor basilica in central Rome, Italy. The basilica is located in Piazza di San Lorenzo in Lucina in the Rione Colonna, about two blocks ...

on 18 September 1227 by Pope Gregory IX

Pope Gregory IX (; born Ugolino di Conti; 1145 – 22 August 1241) was head of the Catholic Church and the ruler of the Papal States from 19 March 1227 until his death in 1241. He is known for issuing the '' Decretales'' and instituting the Pa ...

(1227–1241). He later served as papal governor of the March of Ancona

The March of Ancona ( or ''Anconetana'') was a frontier march centred on the city of Ancona and later Fermo then Macerata in the Middle Ages. Its name is preserved as an Italian region today, the Marche, and it corresponds to almost the entir ...

, from 17 October 1235 until 1240.

Sources from the 17th century onwards reported that he became Bishop of Albenga

A bishop is an ordained member of the clergy who is entrusted with a position of authority and oversight in a religious institution. In Christianity, bishops are normally responsible for the governance and administration of dioceses. The role ...

in 1235, but later sources disputed this claim. There is no attestation of this in any of the contemporary sources while there is evidence that the see of Albenga was occupied by a certain Bishop Simon from 1230 until 1255.

Innocent's immediate predecessor was Pope Celestine IV

Pope Celestine IV (; c. 1180/1187 − 10 November 1241), born Goffredo da Castiglione, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 25 October 1241 to his death on 10 November 1241.

History

Born in Milan, Goffredo or Godf ...

, elected on 25 October 1241, whose reign lasted only fifteen days. The events of Innocent IV's pontificate are therefore inextricably linked to the policies dominating the reigns of popes Innocent III

Pope Innocent III (; born Lotario dei Conti di Segni; 22 February 1161 – 16 July 1216) was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 8 January 1198 until his death on 16 July 1216.

Pope Innocent was one of the most power ...

, Honorius III

Pope Honorius III (c. 1150 – 18 March 1227), born Cencio Savelli, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 18 July 1216 to his death. A canon at the Basilica di Santa Maria Maggiore, he came to hold a number of importa ...

and Gregory IX

Pope Gregory IX (; born Ugolino di Conti; 1145 – 22 August 1241) was head of the Catholic Church and the ruler of the Papal States from 19 March 1227 until his death in 1241. He is known for issuing the '' Decretales'' and instituting the P ...

.

Gregory IX

Pope Gregory IX (; born Ugolino di Conti; 1145 – 22 August 1241) was head of the Catholic Church and the ruler of the Papal States from 19 March 1227 until his death in 1241. He is known for issuing the '' Decretales'' and instituting the P ...

had demanded the return of lands belonging to the Papal State

The Papal States ( ; ; ), officially the State of the Church, were a conglomeration of territories on the Italian peninsula under the direct Sovereignty, sovereign rule of the pope from 756 to 1870. They were among the major states of Italy fro ...

s which had been seized by the Emperor Frederick II

Frederick II (, , , ; 26 December 1194 – 13 December 1250) was King of Sicily from 1198, King of Germany from 1212, King of Italy and Holy Roman Emperor from 1220 and King of Jerusalem from 1225. He was the son of Emperor Henry VI of the Ho ...

. The Pope had called a general council to seek the deposing of the emperor with the support of Europe's Church leaders. However, hoping to intimidate the Curia, Frederick had seized two cardinals traveling to the council. Being incarcerated, the two missed the conclave

A conclave is a gathering of the College of Cardinals convened to appoint the pope of the Catholic Church. Catholics consider the pope to be the apostolic successor of Saint Peter and the earthly head of the Catholic Church.

Concerns around ...

which quickly elected Celestine IV. The conclave reconvened after Celestine's death split into factions supporting contrasting policies about how to treat the Emperor.

New pope, same emperor

After a year and a half of contentious debate and coercion, thepapal conclave

A conclave is a gathering of the College of Cardinals convened to appoint the pope of the Catholic Church. Catholics consider the pope to be the apostolic successor of Saint Peter and the earthly head of the Catholic Church.

Concerns around ...

finally reached a unanimous decision. The choice fell upon Cardinal Sinibaldo de' Fieschi, who very reluctantly accepted election as Pope on 25 June 1243, taking the name of Innocent IV. As a cardinal, Sinibaldo had been on friendly terms with Frederick, even after the latter's excommunication. The Emperor greatly admired the cardinal's wisdom, having enjoyed discussions with him from time to time.

Following the election, the witty Frederick remarked that he had lost the friendship of a cardinal but gained the enmity of a pope.

His jest notwithstanding, Frederick's letter to the new pontiff was respectful, offering congratulations to the new Pope and wishing him success. It also expressed hope for an amicable settlement of the differences between the empire and the papacy. Negotiations began shortly afterwards but were not successful. Innocent refused to back down from his demands and Frederick refused to acquiesce. The dispute continued mostly about the restitution of Lombardy

The Lombardy Region (; ) is an administrative regions of Italy, region of Italy that covers ; it is located in northern Italy and has a population of about 10 million people, constituting more than one-sixth of Italy's population. Lombardy is ...

to the Patrimony of St Peter.

The Emperor's machinations aroused a good deal of anti-papal feelings in Italy, particularly in the Papal States, and imperial agents encouraged plots against papal rule. Realizing to be increasingly unsafe in Rome

Rome (Italian language, Italian and , ) is the capital city and most populated (municipality) of Italy. It is also the administrative centre of the Lazio Regions of Italy, region and of the Metropolitan City of Rome. A special named with 2, ...

, Innocent IV secretly and hurriedly withdrew, fleeing Rome on 7 June 1244. Traveling in disguise, he made his way to Sutri

Sutri (Latin ''Sutrium'') is an Ancient town, modern ''comune'' and former bishopric (now a Latin titular see) in the province of Viterbo, about from Rome and about south of Viterbo. It is picturesquely situated on a narrow tuff hill, surrounded ...

and then to the port of Civitavecchia

Civitavecchia (, meaning "ancient town") is a city and major Port, sea port on the Tyrrhenian Sea west-northwest of Rome. Its legal status is a ''comune'' (municipality) of Metropolitan City of Rome Capital, Rome, Lazio.

The harbour is formed by ...

, and from there to Genoa

Genoa ( ; ; ) is a city in and the capital of the Italian region of Liguria, and the sixth-largest city in Italy. As of 2025, 563,947 people live within the city's administrative limits. While its metropolitan city has 818,651 inhabitan ...

, his birthplace, where he arrived on 7 July. On 5 October, he fled from there to France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

, where he was joyously welcomed. Making his way to Lyon

Lyon (Franco-Provençal: ''Liyon'') is a city in France. It is located at the confluence of the rivers Rhône and Saône, to the northwest of the French Alps, southeast of Paris, north of Marseille, southwest of Geneva, Switzerland, north ...

, where he arrived on 29 November 1244, Innocent was greeted cordially by the magistrates of the city.

Innocent was now safe and out of the reach of Frederick II. In a sermon on 27 December 1244, he summoned as many bishops as could get to Lyon (140 bishops eventually came) to attend what became the 13th General (Ecumenical) Council of the Church, the first to be held in Lyon. The bishops met for three public sessions: 28 June, 5 July, and 17 July 1245. Their principal purpose was to win over the Emperor Frederick II

Frederick II (, , , ; 26 December 1194 – 13 December 1250) was King of Sicily from 1198, King of Germany from 1212, King of Italy and Holy Roman Emperor from 1220 and King of Jerusalem from 1225. He was the son of Emperor Henry VI of the Ho ...

.

First Council of Lyon

The

The First Council of Lyon

The First Council of Lyon (Lyon I) was the thirteenth ecumenical council, as numbered by the Catholic Church, taking place in 1245. This was the first ecumenical council to be held outside Rome's Lateran Palace after the Great Schism of 1054. ...

of 1245 had the fewest participants of any previous General Council. However, three patriarchs and the Latin emperor of Constantinople

The Latin Emperor was the ruler of the Latin Empire, the historiographical convention for the Crusader realm, established in Constantinople after the Fourth Crusade (1204) and lasting until the city was reconquered by the Byzantine Greeks in 1 ...

attended, along with about 150 bishops, most of them prelates from France and Spain. They came quickly, and Innocent could rely on their help. Bishops from the rest of Europe outside Spain and France feared retribution from Frederick, while many other bishops were prevented from attending either by the invasions of the Mongols

Mongols are an East Asian ethnic group native to Mongolia, China ( Inner Mongolia and other 11 autonomous territories), as well as the republics of Buryatia and Kalmykia in Russia. The Mongols are the principal member of the large family o ...

(Tartars) in the Far East or Muslim incursions in the Middle East

The Middle East (term originally coined in English language) is a geopolitical region encompassing the Arabian Peninsula, the Levant, Turkey, Egypt, Iran, and Iraq.

The term came into widespread usage by the United Kingdom and western Eur ...

. The bishop of Belgorod in Russia, Peter, attended and provided information on the Mongols via the '' Tractatus de ortu Tartarorum''.

During the session, Frederick II's position was defended by Taddeo of Suessa, who renewed in his master's name all the promises made before, but refused to give the guarantees the pope demanded. The council ended on 17 July with the fathers solemnly deposing and excommunicating the Emperor, while absolving all his subjects from their allegiance.

After Lyon

The council's acts inflamed the political conflict across Europe. The tension subsided only with Frederick's death in December 1250: this removed the threat to Innocent's life and allowed his return to Italy. He departed Lyon on 19 April 1251 and arrived in Genoa on 18 May. On 1 July, he was in Milan, accompanied by only three cardinals and theLatin Patriarch of Constantinople

The Latin Patriarchate of Constantinople was an office established as a result of the Fourth Crusade and its conquest of Constantinople in 1204. It was a Roman Catholic replacement for the Eastern Orthodox Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantino ...

. He stayed there until mid-September, when he began an inspection tour of Lombardy, heading for Bologna. On 5 November he reached Perugia. From 1251 to 1253 the Pope stayed at Perugia

Perugia ( , ; ; ) is the capital city of Umbria in central Italy, crossed by the River Tiber. The city is located about north of Rome and southeast of Florence. It covers a high hilltop and part of the valleys around the area. It has 162,467 ...

until it was safe for him to bring the papal court back to Rome. He finally saw Rome again in the first week of October 1253. He left Rome on 27 April 1254, for Assisi and then Anagni. He immediately dealt with the succession to the possessions of Frederick II, both as German Emperor and as King of Sicily. In both instances, Innocent continued Pope Gregory IX's policy of opposition to the Hohenstaufen, supporting whatever opposing party could be found. This policy embroiled Italy in one conflict after another for the next three decades. Innocent IV himself, following the papal army which was seeking to destroy Frederick's son Manfred, died in Naples on 7 December 1254.

While in Perugia, on 15 May 1252, Innocent IV issued the papal bull

A papal bull is a type of public decree, letters patent, or charter issued by the pope of the Catholic Church. It is named after the leaden Seal (emblem), seal (''bulla (seal), bulla'') traditionally appended to authenticate it.

History

Papal ...

''Ad extirpanda

''Ad extirpanda'' ("To eradicate"; named for its Latin incipit) was a papal bull promulgated on Wednesday, May 15, 1252 by Pope Innocent IV which authorized under defined circumstances the use of torture by the Inquisition as a tool for interrog ...

'', composed of thirty-eight 'laws'. He advised civil authorities in Italy to treat heretics as criminals, and authorized torture as long as it was done "without killing them or breaking their arms or legs" to compel disclosures, "as thieves and robbers of material goods are made to accuse their accomplices and confess the crimes they have committed."

Ruler of princes and kings

As Innocent III had before him, Innocent IV saw himself as the Vicar of Christ, whose power was above earthly kings. Innocent, therefore, had no objection to intervening in purely secular matters. He appointed Afonso III administrator of Portugal, and lent his protection toOttokar

Ottokar is the medieval German form of the Germanic name Audovacar.

People with the name Ottokar include:

*Two kings of Bohemia, members of the Přemyslid dynasty

** Ottokar I of Bohemia (–1230)

** Ottokar II of Bohemia (–1278)

*Four Styrian m ...

, the son of the King of Bohemia

Bohemia ( ; ; ) is the westernmost and largest historical region of the Czech Republic. In a narrow, geographic sense, it roughly encompasses the territories of present-day Czechia that fall within the Elbe River's drainage basin, but historic ...

. The Pope even sided with King Henry III against both nobles and bishops of England, despite the king's harassment of Edmund Rich

Edmund of Abingdon (also known as Edmund Rich, St Edmund of Canterbury, Edmund of Pontigny, French: St Edme; c. 11741240) was an Catholic Church in England and Wales, English Catholic prelate who served as List of archbishops of Canterbury, Ar ...

, the Archbishop of Canterbury and Primate of All England, and the royal policy of having the income of a vacant bishopric or benefice delivered to the royal coffers, rather than handed over to a papal Administrator (usually a member of the Curia) or a Papal collector of revenue, or delivered directly to the Pope.

In the case of the Mongols, too, Innocent maintained that he, as Vicar of Christ, could make non-Christians accept his dominion and even exact punishment should they violate the non-God centred commands of the Ten Commandments. This policy was held more in theory than in practice and was eventually repudiated centuries later.

Northern Crusades

Shortly after Innocent IV's election to the papacy, theTeutonic Order

The Teutonic Order is a religious order (Catholic), Catholic religious institution founded as a military order (religious society), military society in Acre, Israel, Acre, Kingdom of Jerusalem. The Order of Brothers of the German House of Sa ...

sought his consent for the suppression of the Prussian rebellion and for their struggle against the Lithuanians. In response the Pope issued on 23 September 1243 the papal bull

A papal bull is a type of public decree, letters patent, or charter issued by the pope of the Catholic Church. It is named after the leaden Seal (emblem), seal (''bulla (seal), bulla'') traditionally appended to authenticate it.

History

Papal ...

'' Qui iustis causis'', authorizing crusades

The Crusades were a series of religious wars initiated, supported, and at times directed by the Papacy during the Middle Ages. The most prominent of these were the campaigns to the Holy Land aimed at reclaiming Jerusalem and its surrounding t ...

in Livonia

Livonia, known in earlier records as Livland, is a historical region on the eastern shores of the Baltic Sea. It is named after the Livonians, who lived on the shores of present-day Latvia.

By the end of the 13th century, the name was extende ...

and Prussia

Prussia (; ; Old Prussian: ''Prūsija'') was a Germans, German state centred on the North European Plain that originated from the 1525 secularization of the Prussia (region), Prussian part of the State of the Teutonic Order. For centuries, ...

. The bull was reissued by Innocent and his successors in October 1243, March 1256, August 1256 and August 1257.

Vicar of Christ

The papal preoccupation with imperial matters and secular princes caused other matters to suffer. On the one hand, the internal governance of thePapal State

The Papal States ( ; ; ), officially the State of the Church, were a conglomeration of territories on the Italian peninsula under the direct Sovereignty, sovereign rule of the pope from 756 to 1870. They were among the major states of Italy fro ...

s was neglected. Taxation increased in proportion to the discontent of the inhabitants.

On the other hand, the spiritual condition of the Church raised concerns. Innocent attempted to give attention to the latter through a number of interventions.

Canonizations

In 1246Edmund Rich

Edmund of Abingdon (also known as Edmund Rich, St Edmund of Canterbury, Edmund of Pontigny, French: St Edme; c. 11741240) was an Catholic Church in England and Wales, English Catholic prelate who served as List of archbishops of Canterbury, Ar ...

, former Archbishop of Canterbury

The archbishop of Canterbury is the senior bishop and a principal leader of the Church of England, the Primus inter pares, ceremonial head of the worldwide Anglican Communion and the bishop of the diocese of Canterbury. The first archbishop ...

(died 1240), was declared a saint. In 1250 Innocent similarly proclaimed the pious Queen Margaret (died 1093), wife of King Malcolm III of Scotland

Malcolm III (; ; –13 November 1093) was List of Scottish monarchs, King of Alba from 1058 to 1093. He was later nicknamed "Canmore" (, , understood as "great chief"). Malcolm's long reign of 35 years preceded the beginning of the Scoto-Norma ...

, a saint. The Dominican priest Peter of Verona

Peter of Verona (1205 – April 6, 1252), also known as Saint Peter Martyr and Saint Peter of Verona, was a 13th-century Italian Catholic priest. He was a Dominican friar and a celebrated preacher. He served as Inquisitor in Lombardy, was ki ...

, martyred by Albigensian

Catharism ( ; from the , "the pure ones") was a Christian quasi- dualist and pseudo-Gnostic movement which thrived in Southern Europe, particularly in northern Italy and southern France, between the 12th and 14th centuries.

Denounced as a he ...

heretics in 1252, was canonized, as was Stanislaus of Szczepanów

Stanislaus of Szczepanów (; 26 July 1030 – 11 April 1079) was a Polish Catholic prelate who served as Bishop of Kraków and was martyred by the Polish King Bolesław II the Bold. He is the patron saint of Poland.

Stanislaus is vener ...

, the Polish Archbishop of Cracow, both in 1253.

The new Orders

In August 1253, after much worry about the order's insistence on absolute poverty, Innocent finally approved the rule of the Second Order of the Franciscans, thePoor Clares

The Poor Clares, officially the Order of Saint Clare (Latin language, Latin: ''Ordo Sanctae Clarae''), originally referred to as the Order of Poor Ladies, and also known as the Clarisses or Clarissines, the Minoresses, the Franciscan Clarist Or ...

nuns, founded by St. Clare of Assisi

Chiara Offreduccio (16 July 1194 – 11 August 1253), known as Clare of Assisi (sometimes spelled ''Clara'', ''Clair'' or ''Claire''; ), is an Italians, Italian saint who was one of the first followers of Francis of Assisi.

Inspired by the te ...

, the friend of St. Francis.

The concept of ''Persona ficta''

Innocent IV is often credited with helping to create the idea oflegal personality

Legal capacity is a quality denoting either the legal aptitude of a person to have rights and liabilities (in this sense also called transaction capacity), or the personhood itself in regard to an entity other than a natural person (in this sen ...

, ''persona ficta'' as it was originally written, which has led to the idea of corporate personhood. At the time, this allowed monasteries, universities and other bodies to act as a single legal entity, facilitating continuity in their corporate existence. Monks and friars pledged individually to poverty could be part nonetheless of an organization that could own infrastructure. Such institutions, as "fictive persons", could not be excommunicated or considered guilty of delict, that is, negligence to action that is not contractually required. This meant that punishment of individuals within an organization would reflect less on the organization itself than if the person running such an organization was said to own it rather than be a constituent of it, and hence the concept was meant to provide institutional stability.

Compromise on the Talmud

Possibly prompted by the persistence of heretical movements such as theAlbigensian

Catharism ( ; from the , "the pure ones") was a Christian quasi- dualist and pseudo-Gnostic movement which thrived in Southern Europe, particularly in northern Italy and southern France, between the 12th and 14th centuries.

Denounced as a he ...

s, an earlier pope, Gregory IX

Pope Gregory IX (; born Ugolino di Conti; 1145 – 22 August 1241) was head of the Catholic Church and the ruler of the Papal States from 19 March 1227 until his death in 1241. He is known for issuing the '' Decretales'' and instituting the P ...

(1227–1241), had issued letters on 9 June 1239, ordering all the bishops of France to confiscate all Talmud

The Talmud (; ) is the central text of Rabbinic Judaism and the primary source of Jewish religious law (''halakha'') and Jewish theology. Until the advent of Haskalah#Effects, modernity, in nearly all Jewish communities, the Talmud was the cen ...

s in the possession of the Jews. Agents were to raid each synagogue on the first Saturday of Lent 1240, and seize the books, placing them in the custody of the Dominicans or the Franciscans. The Bishop of Paris was ordered to see to it that copies of the Pope's mandate reached all the bishops of France, England, Aragon, Navarre, Castile and León, and Portugal. On 20 June 1239, there was another letter, addressed to the Bishop of Paris, the Prior of the Dominicans and the Minister of the Franciscans, calling for the burning of all copies of the Talmud, and any obstructionists were to be visited with ecclesiastical censures. On the same day, the Pope wrote to the King of Portugal ordering him to see to it that all copies of the Talmud be seized and turned over to the Dominicans or Franciscans. On account of these letters, King Louis IX of France

Louis IX (25 April 1214 – 25 August 1270), also known as Saint Louis, was King of France from 1226 until his death in 1270. He is widely recognized as the most distinguished of the Direct Capetians. Following the death of his father, Louis VI ...

held a trial in Paris in 1240, which ultimately found the Talmud guilty of 35 alleged charges; 24 cartloads of copies of the Talmud were burned.

Initially, Innocent IV continued Gregory IX's policy. In a letter of 9 May 1244, he wrote to King Louis IX, ordering the Talmud and any books with Talmudic glosses to be examined by the Regent Doctors of the University of Paris, and if condemned by them, to be burned. However, an argument was presented that this policy was a negation of the Church's traditional stance of tolerance toward Judaism. On 5 July 1247, Pope Innocent wrote to the Bishops of France and of Germany to say that because both ecclesiastics and lay persons were lawlessly plundering the property of the Jews, and falsely stating that at Eastertime they sacrificed and ate the hearts of little children, the bishops should see to it that the Jews not be attacked or molested for these or other reasons. That same year 1247, in a letter of 2 August to Louis IX, the Pope reversed his stance on the Talmud, ordering that the Talmud should be censored rather than burned. Despite opposition from figures such as Odo of Châteauroux, Cardinal Bishop of Tusculum

The Diocese of Frascati (Lat.: ''Tusculana'') is a Latin suburbicarian see of the Diocese of Rome and a diocese of the Catholic Church in Italy, based at Frascati, near Rome. The bishop of Frascati is a Cardinal Bishop; from the Latin name of th ...

and former Chancellor of the University of Paris, Innocent IV's policy was nonetheless continued by subsequent popes.

Relations with the Jews

Innocent claimed that additionally to the duty of the pope to protect all Christians, this also applied to all Jews. As such, he re-issued the '' Sicut Iudaeis'', also in response to allegations of ritual murder against the Jews ofVienne Vienne may refer to:

Places

*Vienne (department), a department of France named after the river Vienne

*Vienne, Isère, a city in the French department of Isère

* Vienne-en-Arthies, a village in the French department of Val-d'Oise

* Vienne-en-Bessi ...

, but he could not stop local persecutions.

In April 1250 (5 Iyar), Innocent IV ordered the Bishop of Córdoba

A bishop is an ordained member of the clergy who is entrusted with a position of Episcopal polity, authority and oversight in a religious institution. In Christianity, bishops are normally responsible for the governance and administration of di ...

to take action against the Jews who were building a synagogue

A synagogue, also called a shul or a temple, is a place of worship for Jews and Samaritans. It is a place for prayer (the main sanctuary and sometimes smaller chapels) where Jews attend religious services or special ceremonies such as wed ...

whose height was not acceptable to the local clergy. Documents from the reign of Pope Innocent IV recorded resentment toward a prominent new congregational synagogue:

The Jews of Cordoba are rashly presuming to build a new synagogue of unnecessary height thereby scandalizing faithful Christians, wherefore ... we command ou... to enforce the authority of your office against the Jews in this regard....

Diplomatic relations

Relations with the Portuguese

Innocent IV was responsible for the eventual deposition of KingSancho II of Portugal

Sancho II (; 8 September 1207 – 4 January 1248), nicknamed Afonso the Cowled or Afonso the Capuched (), alternatively, Afonso the Pious (), was King of Portugal from 1223 to 1248.

Sancho was born in Coimbra, the eldest son of Afonso II of ...

at the request of his brother Afonso (later King Afonso III of Portugal

Afonso IIIrare English alternatives: ''Alphonzo'' or ''Alphonse'', or ''Affonso'' (Archaic Portuguese), ''Alfonso'' or ''Alphonso'' (Portuguese-Galician languages, Portuguese-Galician) or ''Alphonsus'' (Latin). (; 5 May 121016 February 1279), ca ...

). One of the arguments he used against Sancho II in the Bull

A bull is an intact (i.e., not Castration, castrated) adult male of the species ''Bos taurus'' (cattle). More muscular and aggressive than the females of the same species (i.e. cows proper), bulls have long been an important symbol cattle in r ...

''Grandi non immerito'' was Sancho's status as a minor upon inheriting the throne from his father Afonso II.

Contacts with the Mongols

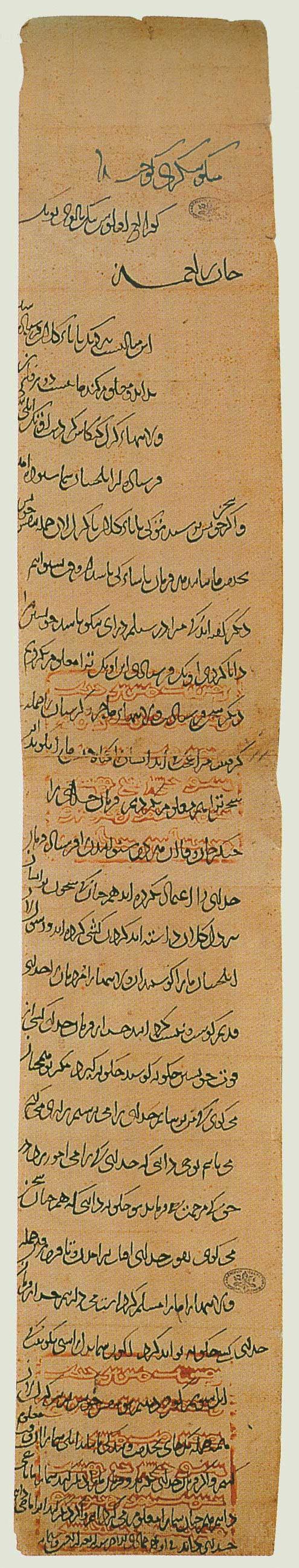

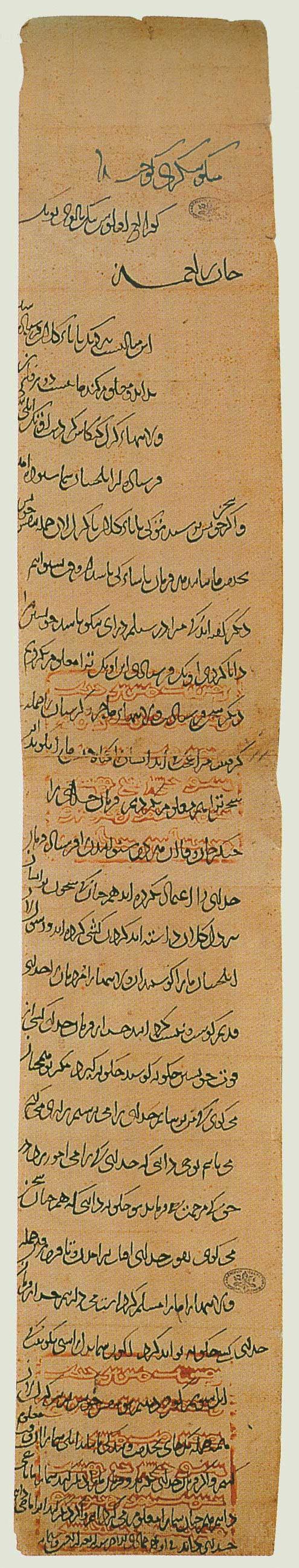

The warlike tendencies of the Mongols also concerned the Pope, and in 1245, he issued bulls and sent a papal

The warlike tendencies of the Mongols also concerned the Pope, and in 1245, he issued bulls and sent a papal nuncio

An apostolic nuncio (; also known as a papal nuncio or simply as a nuncio) is an ecclesiastical diplomat, serving as an envoy or a permanent diplomatic representative of the Holy See to a state or to an international organization. A nuncio is ...

in the person of Giovanni da Pian del Carpine

Giovanni da Pian del Carpine (or Carpini; anglicised as ''John of Plano Carpini''; – 1 August 1252) was a medieval Italian diplomat, Catholic archbishop, explorer and one of the first Europeans to enter the court of the Great Khan of t ...

(accompanied by Benedict the Pole) to the "Emperor of the Tartars". The message

A message is a unit of communication that conveys information from a sender to a receiver. It can be transmitted through various forms, such as spoken or written words, signals, or electronic data, and can range from simple instructions to co ...

asked the Mongol

Mongols are an East Asian ethnic group native to Mongolia, China (Inner Mongolia and other 11 autonomous territories), as well as the republics of Buryatia and Kalmykia in Russia. The Mongols are the principal member of the large family of M ...

ruler to become a Christian and stop his aggression against Europe. The Khan Güyük replied in 1246 in a letter written in Persian

Persian may refer to:

* People and things from Iran, historically called ''Persia'' in the English language

** Persians, the majority ethnic group in Iran, not to be conflated with the Iranic peoples

** Persian language, an Iranian language of the ...

mixed Turkic that is still preserved in the Vatican Library

The Vatican Apostolic Library (, ), more commonly known as the Vatican Library or informally as the Vat, is the library of the Holy See, located in Vatican City, and is the city-state's national library. It was formally established in 1475, alth ...

, demanding the submission of the Pope and the other rulers of Europe.

In 1245 Innocent had sent another mission, through another route, led by Ascelin of Lombardia

Ascelin of Lombardy, also known as Nicolas Ascelin or Ascelin of Cremona, was a 13th-century Dominican friar whom Pope Innocent IV sent as an envoy to the Mongols in March 1245. Ascelin met with the Mongol ruler Baiju, and then returned to Europe ...

, also bearing letters. The mission met with the Mongol ruler Baichu near the Caspian Sea

The Caspian Sea is the world's largest inland body of water, described as the List of lakes by area, world's largest lake and usually referred to as a full-fledged sea. An endorheic basin, it lies between Europe and Asia: east of the Caucasus, ...

in 1247. The reply of Baichu was in accordance with that of Güyük, but it was accompanied by two Mongolian envoys to the Papal seat in Lyon

Lyon (Franco-Provençal: ''Liyon'') is a city in France. It is located at the confluence of the rivers Rhône and Saône, to the northwest of the French Alps, southeast of Paris, north of Marseille, southwest of Geneva, Switzerland, north ...

, Aïbeg and Serkis

Aïbeg and Serkis, also Aibeg and Sergis or Aïbäg and Särgis, were two ambassadors sent by the Mongol ruler Baichu to Pope Innocent IV in 1247–1248. They were the first Mongol envoys to Europe.

Aïbeg ("Moon Prince") is thought to have been ...

. In the letter, Guyuk demanded that the Pope appear in person at the Mongol imperial headquarters, Karakorum

Karakorum (Khalkha Mongolian: Хархорум, ''Kharkhorum''; Mongolian script:, ''Qaraqorum'') was the capital city, capital of the Mongol Empire between 1235 and 1260 and of the Northern Yuan, Northern Yuan dynasty in the late 14th and 1 ...

, so that “we might cause him to hear every command that there is of the jasaq”. In 1248 the envoys met with Innocent, who again issued an appeal to the Mongols to stop their killing of Christians.

Innocent IV would also send other missions to the Mongols in 1245, including that of André de Longjumeau and the possibly aborted mission of Laurent de Portugal.

Later politics

Despite other concerns, the later years of Innocent's life were largely directed to political schemes for encompassing the overthrow ofManfred of Sicily

Manfred (; 123226 February 1266) was the last King of Sicily from the Hohenstaufen dynasty, reigning from 1258 until his death. The natural son of the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II, Manfred became regent over the Kingdom of Sicily on b ...

, the natural son of Frederick II, whom the towns and the nobility had for the most part received as his father's successor. Innocent aimed to incorporate the whole Kingdom of Sicily

The Kingdom of Sicily (; ; ) was a state that existed in Sicily and the southern Italian peninsula, Italian Peninsula as well as, for a time, in Kingdom of Africa, Northern Africa, from its founding by Roger II of Sicily in 1130 until 1816. It was ...

into the Papal States

The Papal States ( ; ; ), officially the State of the Church, were a conglomeration of territories on the Italian peninsula under the direct sovereign rule of the pope from 756 to 1870. They were among the major states of Italy from the 8th c ...

, but he lacked the necessary economic and political power. Therefore, after a failed agreement with Charles of Anjou

Charles I (early 1226/12277 January 1285), commonly called Charles of Anjou or Charles d'Anjou, was King of Sicily from 1266 to 1285. He was a member of the royal Capetian dynasty and the founder of the House of Anjou-Sicily. Between 1246 a ...

, he invested Edmund Crouchback

Edmund, 1st Earl of Lancaster (16 January 12455 June 1296), also known as Edmund Crouchback, was a member of the royal Plantagenet Dynasty and the founder of the first House of Lancaster. He was Earl of Leicester (1265–1296), Lancaster (1267� ...

, the nine-year-old son of King Henry III of England

Henry III (1 October 1207 – 16 November 1272), also known as Henry of Winchester, was King of England, Lord of Ireland, and Duke of Aquitaine from 1216 until his death in 1272. The son of John, King of England, King John and Isabella of Ang ...

, with that kingdom on 14 May 1254.

In the same year, Innocent excommunicated Frederick II's other son, Conrad IV, King of Germany

Conrad (25 April 1228 – 21 May 1254), a member of the Hohenstaufen dynasty, was the only son of Emperor Frederick II from his second marriage with Queen Isabella II of Jerusalem. He inherited the title of King of Jerusalem (as Conrad II) up ...

, but the latter died a few days after the investiture of Edmund. Innocent spent the spring of 1254 in Assisi and then, at the beginning of June, moved to Anagni

Anagni () is an ancient town and ''comune'' in the province of Frosinone, Lazio, in the hills east-southeast of Rome. It is a historical and artistic centre of the Latin Valley.

Geography Overview

Anagni still maintains the appearance of a s ...

, where he awaited Manfred's reaction to the event, especially considering that Conrad's heir, Conradin

Conrad III (25 March 1252 – 29 October 1268), called ''the Younger'' or ''the Boy'', but usually known by the diminutive Conradin (, ), was the last direct heir of the House of Hohenstaufen. He was Duke of Swabia (1254–1268) and nominal King ...

, had been entrusted to Papal tutelage by King Conrad's testament. Manfred submitted, although probably only to gain time and counter the menace from Edmund, and accepted the title of papal vicar

A vicar (; Latin: ''vicarius'') is a representative, deputy or substitute; anyone acting "in the person of" or agent for a superior (compare "vicarious" in the sense of "at second hand"). Linguistically, ''vicar'' is cognate with the English pre ...

for southern Italy. Innocent could therefore enjoy a moment in which he was the acknowledged sovereign, in theory at least, of most of the peninsula. Innocent overplayed his hand, however, by accepting the fealty of the city of Amalfi

Amalfi (, , ) is a town and ''comune'' in the province of Salerno, in the region of Campania, Italy, on the Gulf of Salerno. It lies at the mouth of a deep ravine, at the foot of Monte Cerreto (1,315 metres, 4,314 feet), surrounded by dramatic c ...

directly to the Papacy instead of to the Kingdom of Sicily on 23 October. Manfred immediately, on 26 October, fled from Teano

Teano is a town and ''comune'' in the province of Caserta, Campania, southern Italy, northwest of Caserta on the main line to Rome from Naples. It stands at the southeast foot of an extinct volcano, Rocca Monfina. Its St. Clement's cathedral is ...

, where he had established his headquarters, and headed to Lucera

Lucera (Neapolitan language, Lucerino: ) is an Italian city of 34,243 inhabitants in the province of Foggia in the region of Apulia, and the seat of the Diocese of Lucera-Troia.

Located upon a flat knoll in the Tavoliere delle Puglie, Tavoliere ...

to rejoin his Saracen troops.

Manfred had not lost his nerve, and organized resistance to papal aggression. Supported by his faithful Saracen troops, he began using military force to make rebellious barons and towns submit to his authority as Regent for his nephew.

Final conflict

Realizing that Manfred had no intention of submitting to the Papacy or to anyone else, Innocent and his papal army headed south from his summer residence at Anagni on 8 October, intending to confront Manfred's forces. On 27 October 1254 the Pope entered the city ofNaples

Naples ( ; ; ) is the Regions of Italy, regional capital of Campania and the third-largest city of Italy, after Rome and Milan, with a population of 908,082 within the city's administrative limits as of 2025, while its Metropolitan City of N ...

. It was there, on a sick bed, that Innocent heard of Manfred's victory at Foggia

Foggia (, ; ; ) is a city and ''comune'' (municipality) of Apulia, in Southern Italy, capital of the province of Foggia. In 2013, its population was 153,143. Foggia is the main city of a plain called Tavoliere delle Puglie, Tavoliere, also know ...

on 2 December against the Papal forces, led by the new Papal Legate, Cardinal Guglielmo Fieschi

Guglielmo Fieschi was an Italian cardinal and cardinal-nephew of Pope Innocent IV, his uncle, who elevated him on May 28, 1244.

He was born between 1210 and 1220 in Genoa, but nothing is known about his life before his elevation to the cardinalat ...

, the Pope's nephew. The tidings are said to have precipitated Pope Innocent's death on 7 December 1254 in Naples. From triumph to disaster had taken only a few months.

Shortly after Innocent's election as pope, his nephew Opizzo had been appointed Latin Patriarch of Antioch

Antioch on the Orontes (; , ) "Antioch on Daphne"; or "Antioch the Great"; ; ; ; ; ; ; . was a Hellenistic Greek city founded by Seleucus I Nicator in 300 BC. One of the most important Greek cities of the Hellenistic period, it served as ...

. In December 1251 Innocent IV himself appointed another nephew, Ottobuono, Cardinal Deacon of S. Andriano.Eubel I, pp. 7, 48. Ottobuono was subsequently elected Pope Adrian V

Pope Adrian V (; – 18 August 1276), born Ottobuono de' Fieschi, was the head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 11 July 1276 to his death on 18 August 1276. He was an envoy of Pope Clement IV sent to England in May 1 ...

in 1276.

Upon his death, Innocent IV was succeeded by Pope Alexander IV

Pope Alexander IV (1199 or 1185 – 25 May 1261) was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 12 December 1254 to his death.

Early career

He was born as Rinaldo di Jenne in Jenne, Italy, Jenne (now in the Province of Rome ...

(Rinaldo de' Conti).

See also

*Fieschi family

The House of Fieschi were an old Italian noble family from Genoa, Italy, from whom descend the Fieschi Ravaschieri Princes of Belmonte. Of ancient origin, they took their name from the progenitor ''Ugo Fliscus'', descendants of the counts of L ...

* List of popes

This chronological list of the popes of the Catholic Church corresponds to that given in the under the heading "" (The Roman Supreme Pontiffs), excluding those that are explicitly indicated as antipopes. Published every year by the Roman Curia ...

* Cardinals created by Innocent IV

* The clash between the Church and the Empire

References

Citations

Bibliography

* Accame, Paolo (1923). ''Sinibaldo Fieschi, vescovo di Albenga'' (Albenga 1923). * Baaken, G. (1993). ''Ius imperii ad regnum. Königreich Sizilien, Imperium Romanum und Römisches Papsttum''... (Köln-Weimar-Wien 1993). * * * * * . * Folz, August (1905). ''Kaiser Friedrich II und Papst Innocenz IV. Ihr Kampf in den Jahren 1244 und 1245'' (Strassburg 1905). * *Mann, Horace K. (1928). ''The Lives of the Popes in the Early Middle Ages'', Vol. 14: The popes at the Height of their Temporal Influence: Innocent IV, The Magnificent, 1243–1254. London: Keegan Paul. * Melloni, Alberto (1990). ''Innocenzo IV: la concezione e l'esperienza della cristianità come regimen unius personae'', Genoa: Marietti, 1990. * Paravicini Bagliani, Agostino (1972), ''Cardinali di curia e "familiae" cardinalizie. Dal 1227 al 1254'', Padua 1972. 2 volumes. * Paravicini Bagliani, Agostino (1995). ''La cour des papes au XIIIe siècle'' (Paris: Hachette, 1995). * Paravicini-Bagliani, Agostino (1994). ''The Pope's Body'' (Chicago: University of Chicago Press 2000) talian edition, ''Il corpo del Papa'', 1994 * Paravicini-Bagliani, Agostino (2000). "Innocenzo IV," ''Enciclopedia dei Papi'' (ed. Mario Simonetti et al.) I (Roma 2000), pp. 384–393. * Paravicini-Bagliani, Agostino (2002b). "Innocent IV," in Philippe Levillain (editor), ''The Papacy: An Encyclopedia Volume 2: Gaius-Proxies'' (NY: Routledge 2002), pp. 790–793. * Pavoni, Romeo (1997). "L'ascesa dei Fieschi tra Genova e Federico II," in D. Calcagno (editor), ''I Fieschi tra Papato e Impero, Atti del convegno (Lavagna, 18 dicembre 1994)'' (Lavagna 1997), pp. 3–44. * * Piergiovanni, W. (1967). "Sinibaldo dei Fieschi decretalista. Ricerche sulla vita," ''Studia Gratiana'' 14 (1967), 126–154 ollectanea Stephan Kuttner, IV * Pisanu, L. (1969). ''L'attività politica di Innocenzo IV e I Francescani (1243–1254)'' (Rome 1969). * Podestà, Ferdinando (1928). ''Innocenzo IV'' (Milan 1928). * Prieto, A. Quintana (1987). ''La documentation pontificia de Innocencio IV (1243–1254)'' (Rome 1987) 2 volumes. * Puttkamer, Gerda von (1930). ''Papst Innocenz IV. Versuch einer Gesamptcharakteristik aus seiner Wirkung'' (Münster 1930). * * Weber, Hans (1900). ''Der Kampf zwischen Papst Innocenz IV. und Kaiser Friedrich II, bis zur Flucht des Papstes nach Lyon'' (Berlin: E. Ebering 1900). * Wolter, L. and H. Holstein (1966), ''Lyon I et Lyon II'' (Paris 1966).External links

Pope Innocent IV on Catholic Encyclopedia

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Innocent 04 1190s births 1254 deaths Clergy from Genoa Italian popes University of Parma alumni University of Bologna alumni Bishops of Albenga Christians of the Prussian Crusade Christians of the Second Swedish Crusade Popes 13th-century popes Fieschi family