Short SB.4 Sherpa on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Short SB.4 Sherpa was an experimental aircraft designed and produced by the

Ulster Aviation Society website

/ref>

Turboméca Palas description

Sherpa fuselage exhibited at Norfolk and Suffolk Aviation Museum, Flixton

{{Short Brothers aircraft 1950s British experimental aircraft Short Brothers aircraft

British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories, and Crown Dependencies.

** Britishness, the British identity and common culture

* British English ...

aircraft manufacturer Short Brothers

Short Brothers plc, usually referred to as Shorts or Short, is an aerospace company based in Belfast, Northern Ireland. Shorts was founded in 1908 in London, and was the first company in the world to make production aeroplanes. It was particu ...

. Only a single example was ever produced.

The Sherpa was developed during the 1950s for the purpose of testing a novel wing design, referred to as an aero-isoclinic wing. It was believed that this wing design could possess favourable qualities for producing tailless aircraft

In aeronautics, a tailless aircraft is an aircraft with no other horizontal aerodynamic surface besides its main wing. It may still have a fuselage, vertical tail fin (vertical stabilizer), and/or vertical rudder.

Theoretical advantages of the ...

, and that the Sherpa would validate the characteristics of the wing for such aircraft to be produced in the future. While such a wing had been flown on the earlier Short SB.1, an unpowered glider

Glider may refer to:

Aircraft and transport Aircraft

* Glider (aircraft), heavier-than-air aircraft primarily intended for unpowered flight

** Glider (sailplane), a rigid-winged glider aircraft with an undercarriage, used in the sport of gliding

...

, it was deemed valuable to use a powered aircraft instead. The design of the Sherpa is largely based upon that of the SB.1, to the extent that it incorporated numerous elements of this aircraft.

The Sherpa performed its maiden flight

The maiden flight, also known as first flight, of an aircraft is the first occasion on which it leaves the ground under its own power. The same term is also used for the first launch of rockets.

The maiden flight of a new aircraft type is alwa ...

on 4 October 1953, after which it spent several years performing experimental flights and the occasional aerial display. After gathering sufficient data for Shorts' purposes, the company decided that it did not show sufficient potential as to continue its research into the aero-isoclinic wing. The sole Sherpa was donated to the College of Aeronautics

Vaughn College of Aeronautics and Technology (commonly called Vaughn College) is a private college in East Elmhurst, New York, specialized in aviation and engineering education. It is adjacent to LaGuardia Airport but was founded in Newark, New ...

at Cranfield

Cranfield is a village and civil parish in the west of Bedfordshire, England, situated between Bedford and Milton Keynes. It had a population of 4,909 in 2001. increasing to 5,369 at the 2011 Census. The parish is in Central Bedfordshire un ...

during the late 1950s and flown for numerous years. It was eventually grounded and used as a static laboratory specimen at the Bristol College of Advanced Technology, before being preserved and put on display at the Norfolk and Suffolk Aviation Museum.

Development

The origins of the Short SB.4 Sherpa can be traced back to the 1920s and the activities of ProfessorGeoffrey T.R. Hill

Geoffrey Terence Roland Hill, (1895 – 26 December 1955) was a British aviator and aeronautical engineer.

Early life

Geoffrey Terence Roland Hill was born in 1895, the son of Michael J. M. Hill, Professor of Mathematics at the University Colle ...

, who was pivotal in the design of the Westland-Hill Pterodactyl

Pterodactyl was the name given to a series of experimental tailless aircraft designs developed by G. T. R. Hill in the 1920s and early 1930s. Named after the genus Pterodactylus, a well-known type of Pterosaur commonly known as the pterodactyl, ...

, a pioneering tailless experimental aircraft.Barnes 1967, pp. 439-440. Even prior to the First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fig ...

, Shorts had been involved in tailless aircraft research, but interest in the field reached new heights in the years immediately following the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

. During the late 1940s, the company worked on multiple proposals for tailless aircraft in response to specifications issued by the Air Ministry

The Air Ministry was a department of the Government of the United Kingdom with the responsibility of managing the affairs of the Royal Air Force, that existed from 1918 to 1964. It was under the political authority of the Secretary of State ...

, including Specification X.30/46 and Specification B.35/46, which sought a military assault glider

Glider may refer to:

Aircraft and transport Aircraft

* Glider (aircraft), heavier-than-air aircraft primarily intended for unpowered flight

** Glider (sailplane), a rigid-winged glider aircraft with an undercarriage, used in the sport of gliding

...

and strategic bomber

A strategic bomber is a medium- to long-range penetration bomber aircraft designed to drop large amounts of air-to-ground weaponry onto a distant target for the purposes of debilitating the enemy's capacity to wage war. Unlike tactical bomber ...

respectively.Barnes 1967, pp. 439-441.

In particular, one of the company's aeronautical engineer

Aerospace engineering is the primary field of engineering concerned with the development of aircraft and spacecraft. It has two major and overlapping branches: aeronautical engineering and astronautical engineering. Avionics engineering is si ...

s, David Keith-Lucas

David Keith-Lucas (25 March 1911 – 6 April 1997) was a British aeronautical engineer.

Early life

David Keith-Lucas was one of the sons of Alys Hubbard Lucas and Keith Lucas, who invented the first aeronautical compass. After the death of K ...

, was keen to eliminate the parasitic drag normally incurred by the presence of a conventional tail and fuselage, and thus was a keen proponent of the tailless approach.Barnes 1967, p. 441. He also observed that directional stability was a critical issue without the application of traditional fins and rudder

A rudder is a primary control surface used to steer a ship, boat, submarine, hovercraft, aircraft, or other vehicle that moves through a fluid medium (generally air or water). On an aircraft the rudder is used primarily to counter adverse yaw a ...

s; it was identified that the outermost parts of the wing could be rotated and repositioned to function as elevon

Elevons or tailerons are aircraft control surfaces that combine the functions of the elevator (used for pitch control) and the aileron (used for roll control), hence the name. They are frequently used on tailless aircraft such as flying wings. A ...

s for stability and control purposes. New wing designs that presented a low aspect ratio, such as the delta wing, had been observed to reduce the onset of these issues; Keith-Lucas and Hill, jointly developed what became known as the aero-isoclinic wing.

Having become sufficiently confident in the merits of the aero-isoclinic wing , Shorts opted to produce a new experimental aircraft to incorporate the latest advances and explore its behaviour, thus it constructed the Short SB.1 glider.Barnes 1967, pp. 441-442. This aircraft was designed to be as inexpensive as possible and thus featured extensive wooden construction alongside its innovative wing.Barnes 1967, p. 442. After only a few months of flight, the SB.1 suffered damage in a heavy landing at RAF Aldergrove

Joint Helicopter Command Flying Station Aldergrove or more simply JHC FS Aldergrove is located south of Antrim, Northern Ireland and northwest of Belfast and adjoins Belfast International Airport. It is sometimes referred to simply as Alder ...

on 17 October 1951. Shorts' chief test pilot, Tom Brooke Smith, objected to further flights of the unpowered glider. Accordingly, it was decided that the fuselage, which had been heavily damaged, would be replaced by a modified design that incorporated a pair of Turbomeca Palas

The Turbomeca Palas is a diminutive centrifugal flow turbojet engine used to power light aircraft. An enlargement of the Turbomeca Piméné, the Palas was designed in 1950 by the French manufacturer Société Turbomeca,Gunston 1989, p. 169. ...

turbojet

The turbojet is an airbreathing jet engine which is typically used in aircraft. It consists of a gas turbine with a propelling nozzle. The gas turbine has an air inlet which includes inlet guide vanes, a compressor, a combustion chamber, ...

engines.Barnes 1967, pp. 442-443.

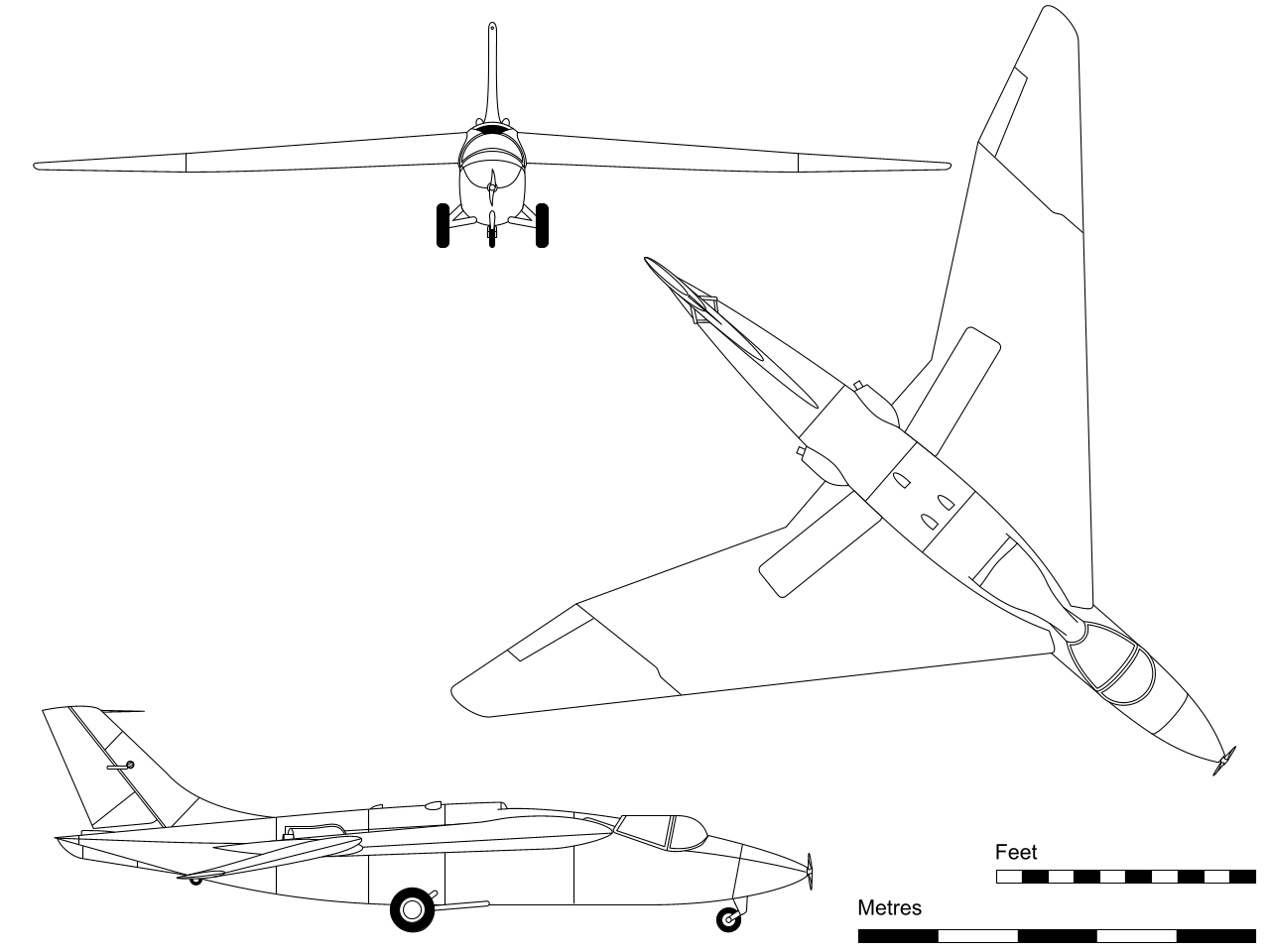

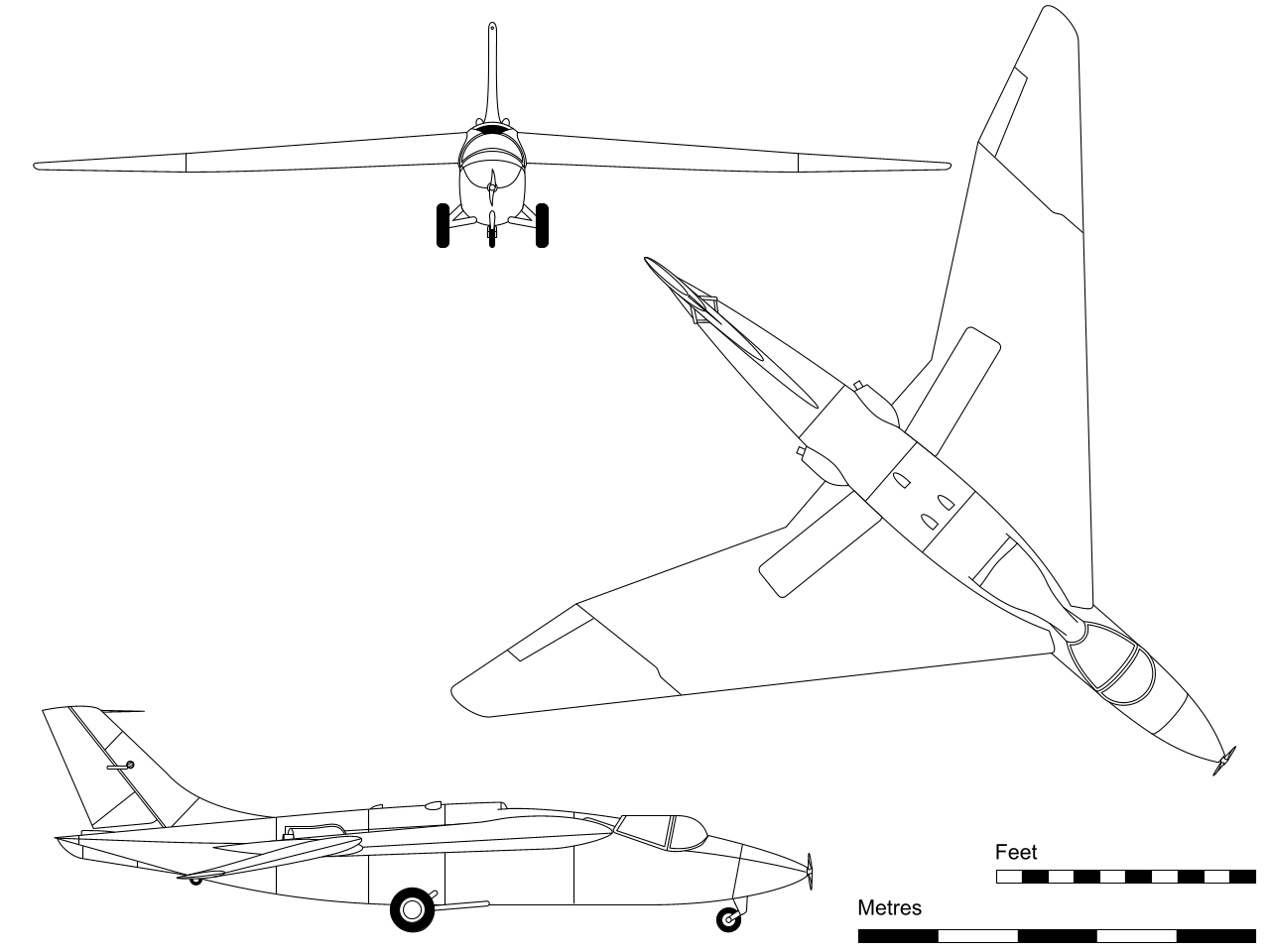

Design

The Short SB.4 Sherpa was an experimental aircraft, featuring an unusual aero-isoclinic wing. This radical wing configuration was designed to maintain a constantangle of incidence

Angle of incidence is a measure of deviation of something from "straight on" and may refer to:

* Angle of incidence (aerodynamics), angle between a wing chord and the longitudinal axis, as distinct from angle of attack

In fluid dynamics, ang ...

regardless of flexing, by placing the torsion box well back in the wing so that the air loads, acting in the region of the quarter-chord

Chord may refer to:

* Chord (music), an aggregate of musical pitches sounded simultaneously

** Guitar chord a chord played on a guitar, which has a particular tuning

* Chord (geometry), a line segment joining two points on a curve

* Chord ( ...

line, have a considerable moment arm

In physics and mechanics, torque is the rotational equivalent of linear force. It is also referred to as the moment of force (also abbreviated to moment). It represents the capability of a force to produce change in the rotational motion of t ...

about it. The torsional instability and tip stalling characteristics of conventional swept wing

A swept wing is a wing that angles either backward or occasionally Forward-swept wing, forward from its root rather than in a straight sideways direction.

Swept wings have been flown since the pioneer days of aviation. Wing sweep at high speeds w ...

s were recognised at the time, together with their tendency to aileron-reversal and flutter

Flutter may refer to:

Technology

* Aeroelastic flutter, a rapid self-feeding motion, potentially destructive, that is excited by aerodynamic forces in aircraft and bridges

* Flutter (American company), a gesture recognition technology company acqu ...

at high speed; the aero-isoclinic wing was designed to specifically prevent these undesirable effects.Barnes 1967, pp. 441-443.

In the Sherpa, the wing, which was used without a tailplane

A tailplane, also known as a horizontal stabiliser, is a small lifting surface located on the tail (empennage) behind the main lifting surfaces of a fixed-wing aircraft as well as other non-fixed-wing aircraft such as helicopters and gyroplan ...

, was fitted with rotating tips comprising approximately one-fifth of the total wing area. Unlike pure wingtip ailerons, these surfaces were a bit more like "wingtip elevon

Elevons or tailerons are aircraft control surfaces that combine the functions of the elevator (used for pitch control) and the aileron (used for roll control), hence the name. They are frequently used on tailless aircraft such as flying wings. A ...

s", as they were rotated together (to act as elevator

An elevator or lift is a cable-assisted, hydraulic cylinder-assisted, or roller-track assisted machine that vertically transports people or freight between floors, levels, or decks of a building, vessel, or other structure. They ar ...

s) or in opposition (when they acted as aileron

An aileron (French for "little wing" or "fin") is a hinged flight control surface usually forming part of the trailing edge of each wing of a fixed-wing aircraft. Ailerons are used in pairs to control the aircraft in roll (or movement arou ...

s). They were hinged at about 30% chord and each carried, on the trailing edge, a small anti-balance tab, the fulcrum of which could be moved by means of an electric actuator. It was expected that the rotary wing tip controls would prove greatly superior to the flap type at transonic

Transonic (or transsonic) flow is air flowing around an object at a speed that generates regions of both subsonic and supersonic airflow around that object. The exact range of speeds depends on the object's critical Mach number, but transoni ...

speeds and provide greater manœuvrability at high altitudes.Barnes 1967, pp. 443-444.

In terms of its construction, the Sherpa was primarily composed of light alloy

An alloy is a mixture of chemical elements of which at least one is a metal. Unlike chemical compounds with metallic bases, an alloy will retain all the properties of a metal in the resulting material, such as electrical conductivity, ductilit ...

s and featured a monocoque

Monocoque ( ), also called structural skin, is a structural system in which loads are supported by an object's external skin, in a manner similar to an egg shell. The word ''monocoque'' is a French term for "single shell".

First used for boats, ...

arrangement. Wing sweep-back on the leading edge was just over 42° to facilitate low-speed research. The Sherpa was provisioned with a conventional tricycle undercarriage

Tricycle gear is a type of aircraft undercarriage, or ''landing gear'', arranged in a tricycle fashion. The tricycle arrangement has a single nose wheel in the front, and two or more main wheels slightly aft of the center of gravity. Tricycle ...

. Two diminutive engines (Turbomeca Palas

The Turbomeca Palas is a diminutive centrifugal flow turbojet engine used to power light aircraft. An enlargement of the Turbomeca Piméné, the Palas was designed in 1950 by the French manufacturer Société Turbomeca,Gunston 1989, p. 169. ...

) were buried in the upper fuselage with a NACA flush inlet on the top of the fuselage and toed-out exhausts located at the wing roots. Fuel was housed within the fuselage in two 250 gallon tanks, which were balanced around the aircraft's center of gravity; electrical power was supplied by a ram air turbine

A ram air turbine (RAT) is a small wind turbine that is connected to a hydraulic pump, or electrical generator, installed in an aircraft and used as a power source. The RAT generates power from the airstream by ram pressure due to the speed of ...

by the engines.Barnes 1967, p. 444. Blackburn

Blackburn () is an industrial town and the administrative centre of the Blackburn with Darwen borough in Lancashire, England. The town is north of the West Pennine Moors on the southern edge of the Ribble Valley, east of Preston and nort ...

, who produced the Palas under licence, hoping to market these engines as a new product line, supplied the powerplants for the Sherpa programme.

Testing

On 4 October 1953, the Sherpa performed itsmaiden flight

The maiden flight, also known as first flight, of an aircraft is the first occasion on which it leaves the ground under its own power. The same term is also used for the first launch of rockets.

The maiden flight of a new aircraft type is alwa ...

, piloted by Shorts' Chief Test Pilot

A test pilot is an aircraft pilot with additional training to fly and evaluate experimental, newly produced and modified aircraft with specific maneuvers, known as flight test techniques.Stinton, Darrol. ''Flying Qualities and Flight Testin ...

, Tom Brooke-Smith. Brooke-Smith had also piloted the earlier experimental glider aircraft, the Short SB.1, upon which the Sherpa was based. Although he sustained injuries in the crash landing of the SB.1, Brooke-Smith had quickly recovered and was able to undertake the test programme of the redesignated SB.4 (registered as ''G-14-1'') throughout 1953–1954. (Incidentally, the Sherpa was named following the conquest of Mount Everest but derived its name specifically from its company designation "Short & Harland Experimental Research Prototype Aircraft.)

During the initial series of flying trials of the Sherpa, performed largely by Brooke-Smith, the aircraft had reportedly proved to be quite satisfactory; its docile handling characteristics led to be being described as being 'one of the most graceful aircraft now flying'. The aircraft was typically flown within a restricted flight envelope, during which it reportedly achieved a "flat-out" speed of at ,Barnes and James 1989, p. 444. which made it amongst the slowest jet-powered aircraft to have ever flown.Gunston 1977, p. 513.

Data from these flights was typically captured by an onboard flight data recorder

A flight recorder is an electronic recording device placed in an aircraft for the purpose of facilitating the investigation of aviation accidents and incidents. The device may often be referred to as a "black box", an outdated name which has b ...

and analysed post-flight to build up a model of how a similar full-sized wing would behave under various conditions, including various altitudes and speeds. Keith-Lucas had aimed to validated the wing as a low weight solution that behaved well across various speeds, including the transsonic range, but the attained test results did not fully validate his hopes.Barnes 1967, pp. 444-445. Aviation author Bill Gunston notes that, despite the Sherpa having attaining its design goals, the concept was considered to be "not fully realised in practice" and the project was eventually wound up without a direct continuation. Shorts did prepare multiple proposals, such as the retrofitting of the Supermarine Swift

The Supermarine Swift is a British single-seat jet propulsion, jet fighter aircraft that was operated by the Royal Air Force (RAF). It was developed and manufactured by Supermarine during the 1940s and 1950s. The Swift featured many of the new ...

fighter with the aero-isoclinic wing, but these were not pursued.Barnes 1967, p. 445.

The Sherpa itself was subsequently donated to the College of Aeronautics

Vaughn College of Aeronautics and Technology (commonly called Vaughn College) is a private college in East Elmhurst, New York, specialized in aviation and engineering education. It is adjacent to LaGuardia Airport but was founded in Newark, New ...

at Cranfield

Cranfield is a village and civil parish in the west of Bedfordshire, England, situated between Bedford and Milton Keynes. It had a population of 4,909 in 2001. increasing to 5,369 at the 2011 Census. The parish is in Central Bedfordshire un ...

, where it continued to fly up until 1958. At this point, engine issues forced the aircraft to be grounded until replacement powerplants could be organised. During 1960, further engines were made available, thus flying of the Sherpa resumed until 1964, when, with its engine life expired, the Sherpa was finally grounded. Following this, it was transported to the Bristol College of Advanced Technology, where the airframe was used as a "laboratory specimen". Its fuselage was on display at the Norfolk and Suffolk Aviation Museum, near Bungay

Bungay () is a market town, civil parish and electoral ward in the English county of Suffolk.OS Explorer Map OL40: The Broads: (1:25 000) : . It lies in the Waveney Valley, west of Beccles on the edge of The Broads, and at the neck of a mean ...

, Suffolk

Suffolk () is a ceremonial county of England in East Anglia. It borders Norfolk to the north, Cambridgeshire to the west and Essex to the south; the North Sea lies to the east. The county town is Ipswich; other important towns include L ...

,Barnes 1967, pp. 445-446. until 17 July 2008, after which it was moved to the Lisburn site of the Ulster Aviation Society.

Aircraft on display

The sole SB.4 is on display at the Ulster Aviation Collection, Long Kesh Airfield, near Belfast/ref>

Specifications

See also

Reference

Citations

Bibliography

* Barnes, C.H. ''Shorts Aircraft since 1900''. London: Putnam, 1967. * Barnes, C.H. with revisions by Derek N. James. ''Shorts Aircraft since 1900''. London: Putnam, 1989 (revised). . * * Buttler, Tony and Jean-Louis Delezenne. ''X-Planes of Europe: Secret Research Aircraft from the Golden Age 1946-1974''. Manchester, UK: Hikoki Publications, 2012. * Gunston, Bill. "Short's Experimental Sherpa." ''Aeroplane Monthly,'' Vol. 5, no. 10. October 1977, pp. 508–515. * "Sherpa - Fore-runner of High Speed, High Altitude Aircraft." ''Shorts Quarterly Review, Vol. 2, No. 3, Autumn 1953.'' *External links

Turboméca Palas description

Sherpa fuselage exhibited at Norfolk and Suffolk Aviation Museum, Flixton

{{Short Brothers aircraft 1950s British experimental aircraft Short Brothers aircraft