Sholto Johnstone Douglas on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Robert Sholto Johnstone Douglas (3 December 1871 – 10 March 1958), known as Sholto Douglas, or more formally as Sholto Johnstone Douglas, was a Scottish

Douglas was born in

Douglas was born in

at panvertu.com, accessed 22 January 2008 Douglas studied art in

On 9 November 1912, under the headline 'Sholto J. Douglas Coming Here', the ''

On 9 November 1912, under the headline 'Sholto J. Douglas Coming Here', the ''

Tudor 5

at william1.co.uk, accessed 22 January 2009

Sholto Johnstone DOUGLAS (1871-1958)

at artprice.com web site

at artnet.com web site

Sholto Johnstone Douglas

at arcadja.com/auctions web site {{DEFAULTSORT:Douglas, Sholto Johnstone 1871 births 1958 deaths Alumni of the Slade School of Fine Art 19th-century Scottish painters Scottish male painters 20th-century Scottish painters Artists from Edinburgh 19th-century Scottish male artists 20th-century Scottish male artists

figurative art

Figurative art, sometimes written as figurativism, describes artwork (particularly paintings and sculptures) that is clearly derived from real object sources and so is, by definition, representational. The term is often in contrast to abstract ...

ist, a painter chiefly of portrait

A portrait is a painting, photograph, sculpture, or other artistic representation of a person, in which the face and its expressions are predominant. The intent is to display the likeness, personality, and even the mood of the person. For this ...

s and landscape

A landscape is the visible features of an area of land, its landforms, and how they integrate with natural or man-made features, often considered in terms of their aesthetic appeal.''New Oxford American Dictionary''. A landscape includes th ...

s.

In 1895, he stood surety

In finance, a surety , surety bond or guaranty involves a promise by one party to assume responsibility for the debt obligation of a borrower if that borrower defaults. Usually, a surety bond or surety is a promise by a surety or guarantor to pa ...

for the bail

Bail is a set of pre-trial restrictions that are imposed on a suspect to ensure that they will not hamper the judicial process. Bail is the conditional release of a defendant with the promise to appear in court when required.

In some countrie ...

of Oscar Wilde

Oscar Fingal O'Flahertie Wills Wilde (16 October 185430 November 1900) was an Irish poet and playwright. After writing in different forms throughout the 1880s, he became one of the most popular playwrights in London in the early 1890s. He is ...

.

Early life

Douglas was born in

Douglas was born in Edinburgh

Edinburgh ( ; gd, Dùn Èideann ) is the capital city of Scotland and one of its 32 Council areas of Scotland, council areas. Historically part of the county of Midlothian (interchangeably Edinburghshire before 1921), it is located in Lothian ...

, a member of the aristocratic Queensberry family, part of the Clan Douglas

Clan Douglas is an ancient clan or noble house from the Scottish Lowlands.

Taking their name from Douglas in Lanarkshire, their leaders gained vast territories throughout the Borders, Angus, Lothian, Moray, and also in France and Sweden. The ...

. He was the son of Arthur Johnstone-Douglas DL JP of Lockerbie (1846–1923) and his wife Jane Maitland Stewart, and the grandson of Robert Johnstone Douglas of Lockerbie, himself the son of Henry Alexander Douglas, a brother of the sixth and seventh Marquesses of Queensberry. His paternal grandmother, Lady Jane Douglas (1811–1881), was herself a daughter of Charles Douglas, 6th Marquess of Queensberry

Charles Douglas, 6th Marquess of Queensberry, (March 1777 – 3 December 1837), known as Sir Charles Douglas, 5th Baronet between 1783 and 1810, was a Scottish peer and member of Clan Douglas.

Early life

Douglas was the eldest son and heir of Si ...

, so she was her husband's first cousin. Douglas's third cousin and contemporary John Douglas, 9th Marquess of Queensberry

John Sholto Douglas, 9th Marquess of Queensberry (20 July 184431 January 1900), was a British nobleman, remembered for his atheism, his outspoken views, his brutish manner, for lending his name to the " Queensberry Rules" that form the basis o ...

(1844–1900) was famous for the rules of the sport of boxing

Boxing (also known as "Western boxing" or "pugilism") is a combat sport in which two people, usually wearing protective gloves and other protective equipment such as hand wraps and mouthguards, throw punches at each other for a predetermine ...

. Another cousin was Lady Florence Dixie

Lady Florence Caroline Dixie (née Douglas; 25 May 18557 November 1905) was a Scottish writer, war correspondent, and feminist. Her account of travelling ''Across Patagonia'', her children's books ''The Young Castaways'' and ''Aniwee; or, The ...

, the war correspondent and big game hunter

Big-game hunting is the hunting of large game animals for meat, commercially valuable by-products (such as horns/ antlers, furs, tusks, bones, body fat/ oil, or special organs and contents), trophy/ taxidermy, or simply just for recre ...

.Sholto Johnstone Douglasat panvertu.com, accessed 22 January 2008 Douglas studied art in

London

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary dow ...

, at the Slade School of Fine Art

The UCL Slade School of Fine Art (informally The Slade) is the art school of University College London (UCL) and is based in London, England. It has been ranked as the UK's top art and design educational institution. The school is organised as ...

and also in Paris

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. ...

and Antwerp.

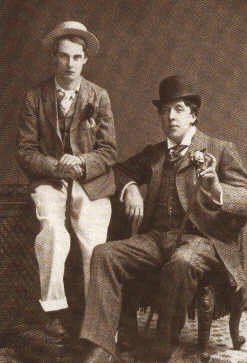

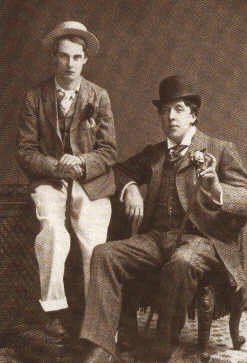

Douglas's cousin Lord Alfred Douglas

Lord Alfred Bruce Douglas (22 October 1870 – 20 March 1945), also known as Bosie Douglas, was an English poet and journalist, and a lover of Oscar Wilde. At Oxford he edited an undergraduate journal, ''The Spirit Lamp'', that carried a homoer ...

, or 'Bosie', was a close friend of the writer Oscar Wilde

Oscar Fingal O'Flahertie Wills Wilde (16 October 185430 November 1900) was an Irish poet and playwright. After writing in different forms throughout the 1880s, he became one of the most popular playwrights in London in the early 1890s. He is ...

. When Wilde sued Bosie's father for libel

Defamation is the act of communicating to a third party false statements about a person, place or thing that results in damage to its reputation. It can be spoken (slander) or written (libel). It constitutes a tort or a crime. The legal defi ...

when accused of "posing as a somdomite" (''sic''), this led to Wilde's downfall and imprisonment. In 1895, when during his trial Wilde was released on bail

Bail is a set of pre-trial restrictions that are imposed on a suspect to ensure that they will not hamper the judicial process. Bail is the conditional release of a defendant with the promise to appear in court when required.

In some countrie ...

, Sholto Johnstone Douglas stood surety

In finance, a surety , surety bond or guaranty involves a promise by one party to assume responsibility for the debt obligation of a borrower if that borrower defaults. Usually, a surety bond or surety is a promise by a surety or guarantor to pa ...

for £500 of the bail money.

In his ''Noel Coward: A Biography'' (1996), Philip Hoare writes of "...late nineteenth-century enthusiasts of boy-love; writers, artists and Catholic converts inclined to intellectual paedophilia, among them Wilde, Frederick Rolfe, Sholto Douglas and Lord Alfred Douglas."

Life and work

As a portrait painter, Douglas belonged to the period ofJohn Singer Sargent

John Singer Sargent (; January 12, 1856 – April 14, 1925) was an American expatriate artist, considered the "leading portrait painter of his generation" for his evocations of Edwardian-era luxury. He created roughly 900 oil paintings and mor ...

and "...led a long life notable for its unassuming expression of civilized values".''Sholto Johnstone Douglas'', obituary in ''The Times

''The Times'' is a British daily national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its current name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its sister paper '' The Sunday Times'' ...

'', March 1958

He was at home in Scotland as a painter and as a sportsman, shooting

Shooting is the act or process of discharging a projectile from a ranged weapon (such as a gun, bow, crossbow, slingshot, or blowpipe). Even the acts of launching flame, artillery, darts, harpoons, grenades, rockets, and guided missiles c ...

, riding and sailing

Sailing employs the wind—acting on sails, wingsails or kites—to propel a craft on the surface of the ''water'' ( sailing ship, sailboat, raft, windsurfer, or kitesurfer), on ''ice'' ( iceboat) or on ''land'' ( land yacht) over a chose ...

. He kept ponies

A pony is a type of small horse ('' Equus ferus caballus''). Depending on the context, a pony may be a horse that is under an approximate or exact height at the withers, or a small horse with a specific conformation and temperament. Compared ...

brought back from a visit to Iceland

Iceland ( is, Ísland; ) is a Nordic island country in the North Atlantic Ocean and in the Arctic Ocean. Iceland is the most sparsely populated country in Europe. Iceland's capital and largest city is Reykjavík, which (along with its ...

. He came to attention at the Royal Academy

The Royal Academy of Arts (RA) is an art institution based in Burlington House on Piccadilly in London. Founded in 1768, it has a unique position as an independent, privately funded institution led by eminent artists and architects. Its purp ...

by being the first artist to hang a painting there of a motor car

A car or automobile is a motor vehicle with wheels. Most definitions of ''cars'' say that they run primarily on roads, seat one to eight people, have four wheels, and mainly transport people instead of goods.

The year 1886 is regarded a ...

, but was best known for his portrait

A portrait is a painting, photograph, sculpture, or other artistic representation of a person, in which the face and its expressions are predominant. The intent is to display the likeness, personality, and even the mood of the person. For this ...

s and his Scottish landscape

A landscape is the visible features of an area of land, its landforms, and how they integrate with natural or man-made features, often considered in terms of their aesthetic appeal.''New Oxford American Dictionary''. A landscape includes th ...

s, which "...portrayed, with a truly poetic sense of atmosphere, the subtle half-tones of his native countryside".

In 1897, Douglas visited Australia and New Zealand

New Zealand ( mi, Aotearoa ) is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and over 700 List of islands of New Zealand, smaller islands. It is the ...

. His uncle John Douglas, a former Premier of Queensland

The premier of Queensland is the head of government in the Australian state of Queensland.

By convention the premier is the leader of the party with a parliamentary majority in the unicameral Legislative Assembly of Queensland. The premier is ap ...

and Governor of New Guinea

New Guinea (; Hiri Motu: ''Niu Gini''; id, Papua, or , historically ) is the world's second-largest island with an area of . Located in Oceania in the southwestern Pacific Ocean, the island is separated from Australia by the wide Torr ...

, arranged for the author R. W. Semon to take Douglas with him on a visit to New Guinea. Semon wrote "This young Scotsman was just then staying with his uncle on Thursday Island

Thursday Island, colloquially known as TI, or in the Kawrareg dialect, Waiben or Waibene, is an island of the Torres Strait Islands, an archipelago of at least 274 small islands in the Torres Strait. TI is located approximately north of Cap ...

, being on his way back to Europe after a voyage to Australia and New Zealand."

In 1900, Douglas painted the author John Buchan

John Buchan, 1st Baron Tweedsmuir (; 26 August 1875 – 11 February 1940) was a Scottish novelist, historian, and Unionist politician who served as Governor General of Canada, the 15th since Canadian Confederation.

After a brief legal career, ...

. His portrait of his friend George Howson

George William Saul Howson MA (8 August 1860 – 7 January 1919) was an English schoolmaster and writer, notable as the reforming headmaster of Gresham's School from 1900 to 1919.

Early life

Howson was one of the four sons of William Howson ...

, headmaster of Gresham's School

Gresham's School is a public school (English independent day and boarding school) in Holt, Norfolk, England, one of the top thirty International Baccalaureate schools in England.

The school was founded in 1555 by Sir John Gresham as a free ...

, hangs at the school.

In 1904, London's ''Temple Bar'' magazine reported

In June 1907, Douglas held an exhibition of his portraits at the Alpine Club

The first alpine club, the Alpine Club, based in the United Kingdom, was founded in London in 1857 as a gentlemen's club. It was once described as:

:"a club of English gentlemen devoted to mountaineering, first of all in the Alps, members of whic ...

in London

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary dow ...

. ''The International Studio'' noted that

In ''Scottish Painting, Past and Present, 1620-1908'' (1908), James Lewis Caw wrote of Douglas's portrait work:

However, Caw says elsewhere in the same book

In 1909, ''The International Studio'' said of a painting

On 9 November 1912, under the headline 'Sholto J. Douglas Coming Here', the ''

On 9 November 1912, under the headline 'Sholto J. Douglas Coming Here', the ''New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid ...

'' reported Douglas's sailing from London for the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., federal district, five ma ...

, having "a number of commissions to paint portraits in New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

New York may also refer to:

Film and television

* '' ...

".

His work also includes many paintings of " dazzle ships" during the First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fig ...

, and the Imperial War Museum

Imperial War Museums (IWM) is a British national museum organisation with branches at five locations in England, three of which are in London. Founded as the Imperial War Museum in 1917, the museum was intended to record the civil and military ...

has fifty-two of these paintings.

In December 1921, the novelist Arnold Bennett

Enoch Arnold Bennett (27 May 1867 – 27 March 1931) was an English author, best known as a novelist. He wrote prolifically: between the 1890s and the 1930s he completed 34 novels, seven volumes of short stories, 13 plays (some in collaboratio ...

noted in his journal that on Boxing Day he had lunched with Douglas and his wife at the Hotel Bristol

The Hotel Bristol is the name of more than 200 hotels around the world. They range from grand European hotels, such as Hôtel Le Bristol Paris and the Hotel Bristol in Warsaw or Vienna to budget hotels, such as the SRO (single room occupancy ...

in Cannes

Cannes ( , , ; oc, Canas) is a city located on the French Riviera. It is a commune located in the Alpes-Maritimes department, and host city of the annual Cannes Film Festival, Midem, and Cannes Lions International Festival of Creativity. The ci ...

to meet the Polish singer Jean de Reszke

Jean de Reszke (14 January 18503 April 1925) was a Polish tenor and opera star. Reszke came from a musically inclined family. His mother gave him his first singing lessons and provided a home that was a recognized music centre. His sister Josep ...

.

From 1926 to 1939, Douglas lived in France and painted many landscapes in Provence

Provence (, , , , ; oc, Provença or ''Prouvènço'' , ) is a geographical region and historical province of southeastern France, which extends from the left bank of the lower Rhône to the west to the France–Italy border, Italian border ...

.

Elsie Bonita Adams has compared Douglas to the character of Eugene Marchbanks in George Bernard Shaw

George Bernard Shaw (26 July 1856 – 2 November 1950), known at his insistence simply as Bernard Shaw, was an Irish playwright, critic, polemicist and political activist. His influence on Western theatre, culture and politics extended from ...

's play Candida (1898):

In March 2005, a portrait by Douglas of the Scottish laird

Laird () is the owner of a large, long-established Scottish estate. In the traditional Scottish order of precedence, a laird ranked below a baron and above a gentleman. This rank was held only by those lairds holding official recognition in a ...

Ian Brodie, 24th Brodie of Brodie, was accepted by the British government from Brodie's heir in lieu of tax.

Marriage and descendants

On 19 April 1913, Douglas married Bettina, the daughter of Harman Grisewood, ofDaylesford, Gloucestershire

Daylesford is a small, privately owned village and former civil parish, now in the parish of Adlestrop, in the Cotswold district, in the county of Gloucestershire, England, on the border with Oxfordshire. It is situated just south of the A436 ...

. They had one son and one daughter:

* Robert Arthur Sholto Johnstone-Douglas (b. 1914)

* Elizabeth Gwendolen Teresa Johnstone-Douglas (1916–2011), who married William Craven, 6th Earl of Craven

William Robert Bradley Craven, 6th Earl of Craven (8 September 1917 – 27 January 1965) was a British peer.

Early life

Craven was born on 8 September 1917 and was the only child of William Craven, 5th Earl of Craven and the former Mary Willia ...

, in 1954.at william1.co.uk, accessed 22 January 2009

Descendants

Through his daughter, he was a grandfather ofThomas Craven, 7th Earl of Craven

Earl of Craven, in the County of York, is a title that has been created twice, once in the Peerage of England and once in the Peerage of the United Kingdom.

History

The first creation came in the Peerage of England in 1664 in favour of the ...

(1957–1983), Simon Craven, 8th Earl of Craven (1961–1990), and Lady Ann Mary Elizabeth Craven (born 1959), the wife of Dr. Lionel Tarassenko

Lionel Tarassenko, (born 17 April 1957) is a British engineer and academic, who is a leading expert in the application of signal processing and machine learning to healthcare. He was previously Head of Department of Engineering Science (Dean of ...

.

See also

*List of British artists

This is a partial list of artists active in Britain, arranged chronologically (artists born in the same year should be arranged alphabetically within that year).

Born before 1700

* Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/8–1543) – German artist and ...

References

External links

Sholto Johnstone DOUGLAS (1871-1958)

at artprice.com web site

at artnet.com web site

Sholto Johnstone Douglas

at arcadja.com/auctions web site {{DEFAULTSORT:Douglas, Sholto Johnstone 1871 births 1958 deaths Alumni of the Slade School of Fine Art 19th-century Scottish painters Scottish male painters 20th-century Scottish painters Artists from Edinburgh 19th-century Scottish male artists 20th-century Scottish male artists