Shirase Nobu on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

was a Japanese army officer and explorer. He led the first Japanese Antarctic Expedition, 1910–12, which reached a southern latitude of 80°5′, and made the first landing on the coast of

In the course of his military duties, Shirase discussed his ambitions to explore the Arctic with a more senior officer,

In the course of his military duties, Shirase discussed his ambitions to explore the Arctic with a more senior officer,

Since his death, Shirase's contribution to Antarctic history has been widely recognised, in Japan and elsewhere. Japan's interest in the Antarctic revived in 1956, when the first Japanese Antarctic Research Expedition (JARE) sailed with the research ship ''Soya'' to East Ongul Island and established the Showa research station. JARE named numerous features in the area, including the Shirase Glacier. In 1961 the

Since his death, Shirase's contribution to Antarctic history has been widely recognised, in Japan and elsewhere. Japan's interest in the Antarctic revived in 1956, when the first Japanese Antarctic Research Expedition (JARE) sailed with the research ship ''Soya'' to East Ongul Island and established the Showa research station. JARE named numerous features in the area, including the Shirase Glacier. In 1961 the

King Edward VII Land

King Edward VII Land or King Edward VII Peninsula is a large, ice-covered peninsula which forms the northwestern extremity of Marie Byrd Land in Antarctica. The peninsula projects into the Ross Sea between Sulzberger Bay and the northeast corner ...

.

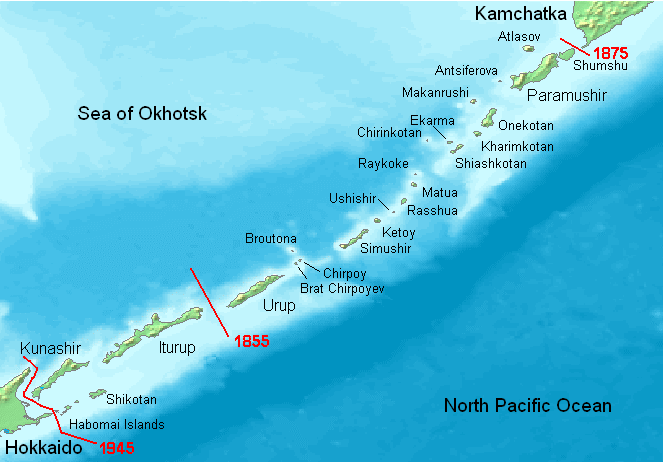

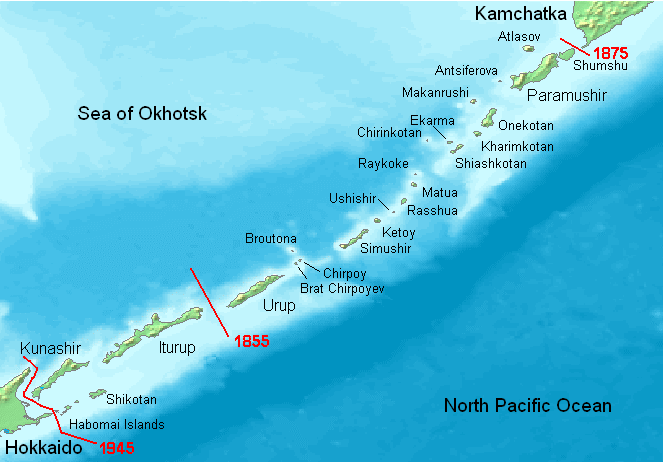

Shirase had harboured polar ambitions since boyhood. By way of preparation, during his military service he participated in an expedition to the northern Kuril Islands

The Kuril Islands or Kurile Islands are a volcanic archipelago administered as part of Sakhalin Oblast in the Russian Far East. The islands stretch approximately northeast from Hokkaido in Japan to Kamchatka Peninsula in Russia, separating the ...

. This venture was poorly organised and ended badly, but nonetheless provided him with useful training for future polar exploration. His longstanding intention was to lead an expedition to the North Pole, but when this mark was claimed by Robert Peary

Robert Edwin Peary Sr. (; May 6, 1856 – February 20, 1920) was an American explorer and officer in the United States Navy who made several expeditions to the Arctic in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. He was long credited as being ...

in 1909, Shirase switched his attention to the south.

Unable to attract government support for his Antarctic venture, Shirase raised the finance privately. In its first season, 1910–11, the expedition failed to make a landing, and was forced to winter in Australia. Its second attempt, in 1911–12, was more successful. Although the expedition's achievements were modest, it demonstrated that the Japanese were competent Antarctic travellers, and Shirase returned to Japan in June 1912 to much local acclaim, although the rest of the world showed little interest in his exploits . Even in Japan his fame was short-lived, and Shirase soon found himself faced with a burden of expedition debt that took him most of the rest of his life to redeem. He died in relative poverty in 1946.

Long after Shirase's death, there was belated recognition in Japan of his pioneering endeavours. Several geographical features in Antarctica were named after him or his expedition; the revived Japanese Antarctic Research Expedition named its third

Third or 3rd may refer to:

Numbers

* 3rd, the ordinal form of the cardinal number 3

* , a fraction of one third

* 1⁄60 of a ''second'', i.e., the third in a series of fractional parts in a sexagesimal number system

Places

* 3rd Street (di ...

and fourth ice-breaking vessels ''Shirase''; his home city of Nikaho erected a statue in 1981, and in 1990 opened a museum dedicated to his memory and the work of his expedition.

Life

Early years

Nobu Shirase was born on 13 June 1861, in the Jorenji temple at Konoura (now part of the city of Nikaho in theAkita Prefecture

is a Prefectures of Japan, prefecture of Japan located in the Tōhoku region of Honshu.Nussbaum, Louis-Frédéric. (2005). "Provinces and prefectures" in ; "Tōhoku" in . Its population is estimated 915,691 as of 1 August 2023 and its geographi ...

), where his father served as a Buddhist priest. At the time of Shirase's birth, Japan was still largely a closed society, isolated from the rest of the world and ruled by the Tokugawa shogunate

The Tokugawa shogunate, also known as the was the military government of Japan during the Edo period from 1603 to 1868.

The Tokugawa shogunate was established by Tokugawa Ieyasu after victory at the Battle of Sekigahara, ending the civil wars ...

which forbade citizens to leave Japan on pain of death. Shirase was seven years old when, following the Boshin civil war of 1868–69, the shogunate was replaced by the Meiji dynasty and the slow process of modernisation began.

Although the concept of geographical exploration was alien in Japan, from an early age Shirase developed a passionate and enduring interest in polar exploration, inspired by the stories he received of the European explorers such as Sir John Franklin

Sir John Franklin (16 April 1786 – 11 June 1847) was a British Royal Navy officer, explorer and colonial administrator. After serving in the Napoleonic Wars and the War of 1812, he led two expeditions into the Canadian Arctic and thro ...

and the search for the Northwest Passage

The Northwest Passage (NWP) is the sea lane between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans through the Arctic Ocean, near the northern coast of North America via waterways through the Arctic Archipelago of Canada. The eastern route along the Arctic ...

. After leaving school in 1879 he began preparation for the priesthood, but this conflicted with his deeper desire to become an explorer. So he left the temple and began training for a career in the Imperial army. In 1881 he was commissioned as a lieutenant

A lieutenant ( , ; abbreviated Lt., Lt, LT, Lieut and similar) is a Junior officer, junior commissioned officer rank in the armed forces of many nations, as well as fire services, emergency medical services, Security agency, security services ...

in the Transport Corps. To prepare himself for future rigours, he adopted a deliberately spartan lifestyle, avoiding drink and tobacco, and forsaking the warmth of the fireside for a regime of hard exercise.

Chishima Expedition 1893–95

In the course of his military duties, Shirase discussed his ambitions to explore the Arctic with a more senior officer,

In the course of his military duties, Shirase discussed his ambitions to explore the Arctic with a more senior officer, Kodama Gentarō

Viscount was a Japanese general in the Imperial Japanese Army and a government minister during the Meiji period. He was instrumental in establishing the modern Imperial Japanese military.

Early life

Kodama was born on March 16, 1852, in Tok ...

, who advised him that he should first try exploring the Kuril Islands

The Kuril Islands or Kurile Islands are a volcanic archipelago administered as part of Sakhalin Oblast in the Russian Far East. The islands stretch approximately northeast from Hokkaido in Japan to Kamchatka Peninsula in Russia, separating the ...

(known in Japan as the Chishima Islands. These islands form a long archipelago that stretches from Hokkaido

is the list of islands of Japan by area, second-largest island of Japan and comprises the largest and northernmost prefectures of Japan, prefecture, making up its own list of regions of Japan, region. The Tsugaru Strait separates Hokkaidō fr ...

in the south to the Russian Kamchatka Peninsula

The Kamchatka Peninsula (, ) is a peninsula in the Russian Far East, with an area of about . The Pacific Ocean and the Sea of Okhotsk make up the peninsula's eastern and western coastlines, respectively.

Immediately offshore along the Pacific ...

in the north. Ownership of the islands had long been in dispute between Japan and Russia, until the Treaty of St. Petersburg, signed in May 1875, awarded the entire chain to Japan which in return gave up its territorial claims on the island of Sakhalin

Sakhalin ( rus, Сахали́н, p=səxɐˈlʲin) is an island in Northeast Asia. Its north coast lies off the southeastern coast of Khabarovsk Krai in Russia, while its southern tip lies north of the Japanese island of Hokkaido. An islan ...

.

An opportunity arose in 1893, when Shirase was able to join an expedition led by Naritada Gunji to the northern islands in the chain. The aim was to establish a permanent Japanese colony on the northernmost island of Shumshu

Shumshu (; ; ) is the easternmost and second-northernmost island of the Kuril Islands chain, which divides the Sea of Okhotsk from the northwest Pacific Ocean. The name of the island is derived from the Ainu language, meaning "good island". It i ...

. The expedition included a diversion to Alaska, on a covert military mission. Poorly organised and ill-equipped, the expedition went badly; during the winter of 1893–94, ten of its members died. Its leader, Gunji, left after a year to fight in the First Sino-Japanese War

The First Sino-Japanese War (25 July 189417 April 1895), or the First China–Japan War, was a conflict between the Qing dynasty of China and the Empire of Japan primarily over influence in Joseon, Korea. In Chinese it is commonly known as th ...

, leaving Shirase and the survivors to face a second winter, during which several more succumbed to privation and scurvy. They were finally relieved in August 1895. Shirase blamed the disaster on poor organisation and leadership, but nevertheless found the experience of Arctic invaluable for his future plans. For the time being he remained in the army, and fought in the Russo-Japanese War

The Russo-Japanese War (8 February 1904 – 5 September 1905) was fought between the Russian Empire and the Empire of Japan over rival imperial ambitions in Manchuria and the Korean Empire. The major land battles of the war were fought on the ...

of 1904–05.

Japanese Antarctic Expedition 1910–12

In 1909, Shirase's long-standing ambitions to lead a North Pole expedition were halted when two Americans,Frederick Cook

Frederick Albert Cook (June 10, 1865 – August 5, 1940) was an American explorer, physician and ethnographer, who is most known for allegedly being the first to reach the North Pole on April 21, 1908. A competing claim was made a year l ...

and Robert Peary

Robert Edwin Peary Sr. (; May 6, 1856 – February 20, 1920) was an American explorer and officer in the United States Navy who made several expeditions to the Arctic in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. He was long credited as being ...

, each claimed independently to have reached the Pole. Although Cook's claim was quickly discounted, Peary's was widely accepted at the time. Having thus been forestalled, Shirase switched his attention instead to the South Pole

The South Pole, also known as the Geographic South Pole or Terrestrial South Pole, is the point in the Southern Hemisphere where the Earth's rotation, Earth's axis of rotation meets its surface. It is called the True South Pole to distinguish ...

. He would have to move quickly, as other expeditions, notably those of Robert Falcon Scott

Captain Robert Falcon Scott (6 June 1868 – ) was a British Royal Navy officer and explorer who led two expeditions to the Antarctic regions: the Discovery Expedition, ''Discovery'' expedition of 1901–04 and the Terra Nova Expedition ...

and Roald Amundsen

Roald Engelbregt Gravning Amundsen (, ; ; 16 July 1872 – ) was a Norwegians, Norwegian explorer of polar regions. He was a key figure of the period known as the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration.

Born in Borge, Østfold, Norway, Am ...

, were in the field. Neither the Japanese government nor the learned societies would support his plans, but in 1910, with help from the influential Count Okuma, he was able to raise funds for an Antarctic expedition, which sailed from Tokyo in the converted fishing vessel '' Kainan Maru'', on 29 November 1910. The plan was to arrive in Antarctica early in 1911, establish winter quarters, and march to the Pole in the 1911–12 season. But Shirase had departed too late; he did not reach Antarctica until March 1911, when the seas had frozen and he was unable to approach land. He was forced to retreat to Sydney, Australia, and winter there. In Australia the expedition received much help and encouragement from the distinguished geologist and Antarctic explorer, Edgeworth David

Sir Tannatt William Edgeworth David (28 January 1858 – 28 August 1934) was a Welsh Australian geologist, Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration, Antarctic explorer, and military veteran. He was knighted for his role in World War 1.

A hou ...

,; ; to whom, as a token of appreciation, Shirase presented his samurai sword.

In November 1911, his expedition refreshed and replenished, Shirase set out for the Antarctic again. He had by this time modified his plans; he recognised that the conquest of the Pole was beyond his reach – Scott and Amundsen were too far ahead of him – and settled for more modest objectives in the fields of science and general exploration. They arrived at the Great Ice Barrier

The Ross Ice Shelf is the largest ice shelf of Antarctica (, an area of roughly and about across: about the size of France). It is several hundred metres thick. The nearly vertical ice front to the open sea is more than long, and between high ...

in the Ross Sea

The Ross Sea is a deep bay of the Southern Ocean in Antarctica, between Victoria Land and Marie Byrd Land and within the Ross Embayment, and is the southernmost sea on Earth. It derives its name from the British explorer James Clark Ross who ...

in January 1912, where they collected meteorological data while Shirase led a sledge journey – the "Dash Patrol" – across an uncharted section of the Barrier, reaching a latitude of 80°5'S. Another party landed on King Edward VII Land

King Edward VII Land or King Edward VII Peninsula is a large, ice-covered peninsula which forms the northwestern extremity of Marie Byrd Land in Antarctica. The peninsula projects into the Ross Sea between Sulzberger Bay and the northeast corner ...

– the first ever to do so from the sea – and explored there, also collecting geological samples. The expedition arrived back in Japan in June 1912 to general acclaim, with no loss of life, no serious injuries and all in good health. Although it had made no major geographical or scientific discoveries, it had proved Japan's ability to organise and execute a polar expedition, the first such by any non-European country. It provided only the fourth instance of travel beyond the 80°S mark, and had surpassed all previous speed records for sledge journeys. Its landing on the King Edward's Land coast was an achievement that had previously defeated both Scott and Ernest Shackleton

Sir Ernest Henry Shackleton (15 February 1874 – 5 January 1922) was an Anglo-Irish Antarctic explorer who led three British expeditions to the Antarctic. He was one of the principal figures of the period known as the Heroic Age of Antarcti ...

, and ''Kainan Maru'' had explored the Antarctic coast further east than any ship up to that time.

Post-expedition, later life and death

Shirase and his companions were treated as heroes on their return, and given a triumphal parade through the streets of Tokyo. Shirase was invited to give a personal account of his experiences to the Imperial family. This, however, proved to be a short-lived period of fame; six weeks after the expedition's return the Emperor Meiji died; the national interest in Antarctica was diverted, and then faded away. Shirase's memoir, published in 1913, has a lukewarm reception, while beyond Japan's boundaries the expedition was either unnoticed or disregarded. Meanwhile, the costs of the expedition had risen considerably as a result of the extra time spent in the south. The government offered no help, and Shirase was faced with responsibility for a large debt. Shirase sold his house to raise funds. For several years, he toured the country giving lectures. In 1921 he returned to the Kuril Islands, hoping to raise further funds through a commercial venture into fur farming. This was only partially successful, and by 1924 he was back in mainland Japan, eking out a living from the land. His former exploits were not quite forgotten; in 1927 he was invited to meet Amundsen, who was visiting Tokyo to publicise details of his forthcoming planned flight over the North Pole. The two had not previously met; when their two expeditions had briefly coincided in the Bay of Whales, in January 1912, Amundsen had been away on his polar journey. As a further sign of increasing recognition, in 1933, when the Japanese Polar Research Institute was founded, Shirase became its honorary president. In that same year, the first English language account of the Japanese Antarctic Expedition was published in the ''Geographical Journal''. Two years later, in 1935, Shirase was able to settle the last of his expedition's outstanding debts. Soon afterwards, the country was embroiled in theSecond Sino-Japanese War

The Second Sino-Japanese War was fought between the Republic of China (1912–1949), Republic of China and the Empire of Japan between 1937 and 1945, following a period of war localized to Manchuria that started in 1931. It is considered part ...

, and all further interest in polar exploration was shelved. Shirase lived through the war years unobtrusively, in a rented room above a fish shop, and died on 4 September 1946 at the age of 85.

Legacy and memorials

New Zealand Antarctic Place-Names Committee New Zealand Antarctic Place-Names Committee (NZ-APC) is an adjudicating committee established to authorize the naming of features in the Ross Dependency on the Antarctic continent. It is composed of the members of the New Zealand Geographic Board pl ...

(NZ-APC) gave the name Shirase Coast to a part of the coastline of King Edward VII Land.

In Sydney, Australia, the Australian Museum

The Australian Museum, originally known as the Colonial Museum or Sydney Museum. is a heritage-listed museum at 1 William Street, Sydney, William Street, Sydney central business district, Sydney CBD, New South Wales. It is the oldest natural ...

now holds the samurai sword presented to Edgeworth David by Shirase just before the expedition began its second voyage to Antarctica in November 1911. The sword was given to the museum in 1979 by David's daughter, and has become a particular point of interest to many Japanese visitors.

In 1981, JARE named its new icebreaker vessel '' Shirase''. This remained in service for 28 years; its replacement, from 2009, was also named '' Shirase''. Also in 1981, Shirase's home town of Nikaho erected a statue close to the explorer's birthplace. The Shirase Antarctic Expedition Party Memorial Museum, dedicated to the explorer's memory, opened in Nikaho in 1990. Each year, on 28 January, the museum holds a special festival, the Walk in the Snow, as a tribute to Shirase's unwavering dedication to the cause of Antarctic exploration.

Notes and references

Citations

Sources

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * Ivanov, Lyubomir; Ivanova, Nusha (2022). Heroic period. In: ''The World of Antarctica''. Generis Publishing. pp. 84-90. {{DEFAULTSORT:Shirase, Nobu Explorers of Antarctica Marie Byrd Land explorers and scientists Japanese polar explorers Japanese explorers Japanese Army officers 1861 births 1946 deaths Military personnel from Akita Prefecture People from Nikaho, Akita