Shigeru Yoshida(mejiro) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

was a Japanese diplomat and politician who served as

Shigeru Yoshida was born on 22 September 1878, in Kanda-Surugadai,

Shigeru Yoshida was born on 22 September 1878, in Kanda-Surugadai,

Following the

Following the

Yoshida's first cabinet was based on a coalition between the Liberal Party and the Japan Progressive Party led by former prime minister Shidehara. The cabinet notably included Shidehara as minister without portfolio and

Yoshida's first cabinet was based on a coalition between the Liberal Party and the Japan Progressive Party led by former prime minister Shidehara. The cabinet notably included Shidehara as minister without portfolio and

In February after the election,

In February after the election,

In April 1950 Yoshida sent Finance Minister Ikeda, together with Ikeda’s secretary

In April 1950 Yoshida sent Finance Minister Ikeda, together with Ikeda’s secretary

Before the signing of the Treaty of San Francisco Ichirō Hatoyama had been released from the purge. Since Yoshida had originally become prime minister as a replacement for Hatoyama, many expected him to step down in Hatoyama's favour, but by this time Yoshida had become a well-established politician in his own right and had no intention to retire. This led to a conflict with Hatoyama.

According to CIA files that were declassified in 2005, there was a 1952 plot to assassinate Yoshida and replace him with Ichirō Hatoyama as prime minister. The plot was led by

Before the signing of the Treaty of San Francisco Ichirō Hatoyama had been released from the purge. Since Yoshida had originally become prime minister as a replacement for Hatoyama, many expected him to step down in Hatoyama's favour, but by this time Yoshida had become a well-established politician in his own right and had no intention to retire. This led to a conflict with Hatoyama.

According to CIA files that were declassified in 2005, there was a 1952 plot to assassinate Yoshida and replace him with Ichirō Hatoyama as prime minister. The plot was led by

online

* * * Rodan, Garry, Hewison, Kevin and Robison, Richard. (1997). ''The Political Economy of South-East Asia: An Introduction.'' Melbourne:

OCLC 464661946

* McGrew, Anthony and Christopher Book.'' (1998) ''Asia-Pacific in the New World Order.'' London:

OCLC 60184921

* * * * * * *

OSS Biographical Report on Yoshida dated January 1945

, - , - , - {{DEFAULTSORT:Yoshida, Shigeru 1878 births 1967 deaths 20th-century prime ministers of Japan Ambassadors of Japan to Italy Ambassadors of Japan to the United Kingdom Ministers for foreign affairs of Japan Honorary Knights Commander of the Royal Victorian Order Japanese anti-communists Japanese prisoners and detainees Japanese Roman Catholics Japanese Christians Liberal Democratic Party (Japan) politicians Democratic Liberal Party (Japan) politicians Liberal Party (Japan, 1945) politicians Members of the House of Peers (Japan) Members of the House of Representatives (Japan) Politicians from Kōchi Prefecture People from Chiyoda, Tokyo People from Yokosuka, Kanagawa People of the Korean War Politicians from Tokyo Prisoners and detainees of Japan University of Tokyo alumni

prime minister of Japan

The is the head of government of Japan. The prime minister chairs the Cabinet of Japan and has the ability to select and dismiss its ministers of state. The prime minister also serves as the commander-in-chief of the Japan Self-Defense Force ...

from 1946 to 1947 and again from 1948 to 1954, serving through most of the country's occupation after World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

. Yoshida played a major role in determining the course of post-war Japan by forging a strong relationship with the United States and pursuing economic recovery.

Born in Tokyo to a former samurai family, Yoshida graduated from Tokyo Imperial University

The University of Tokyo (, abbreviated as in Japanese and UTokyo in English) is a public university, public research university in Bunkyō, Tokyo, Japan. Founded in 1877 as the nation's first modern university by the merger of several Edo peri ...

in 1906 and joined the Ministry of Foreign Affairs

In many countries, the ministry of foreign affairs (abbreviated as MFA or MOFA) is the highest government department exclusively or primarily responsible for the state's foreign policy and relations, diplomacy, bilateral, and multilateral r ...

. He held various assignments abroad, including in China, where he advocated increased Japanese influence. From 1928 to 1930, Yoshida served as vice minister of foreign affairs, then served as ambassador to Italy until 1932. In 1936, he was considered for foreign minister in the cabinet of Kōki Hirota

was a Japanese diplomat and politician who served as prime minister of Japan from 1936 to 1937. Originally his name was . He was executed for war crimes committed during the Second Sino-Japanese War at the Tokyo Trials.

Early life

Hirota was ...

, but he was opposed by the Army

An army, ground force or land force is an armed force that fights primarily on land. In the broadest sense, it is the land-based military branch, service branch or armed service of a nation or country. It may also include aviation assets by ...

, who strongly identified him with liberalism and friendship with Great Britain and the United States. Yoshida served as ambassador to Britain from 1936 to 1938. He largely avoided political participation during the Pacific War

The Pacific War, sometimes called the Asia–Pacific War or the Pacific Theatre, was the Theater (warfare), theatre of World War II fought between the Empire of Japan and the Allies of World War II, Allies in East Asia, East and Southeast As ...

. During the U.S. occupation after the war's end, Yoshida served as foreign minister in the cabinets of Prince Higashikuni and Kijūrō Shidehara

Baron was a Japanese diplomat and politician who served as prime minister of Japan from 1945 to 1946. He was a leading proponent of pacifism in Japan before and after World War II.

Born to a wealthy Osaka family, Shidehara studied law at Tok ...

.

Yoshida became prime minister in 1946, after Ichirō Hatoyama

was a Japanese politician who served as Prime Minister of Japan, prime minister of Japan from 1954 to 1956. During his tenure he oversaw the formation of the Liberal Democratic Party (Japan), Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) and restored official ...

was purged

In history, religion and political science, a purge is a position removal or execution of people who are considered undesirable by those in power from a government, another, their team leaders, or society as a whole. A group undertaking such an ...

by authorities on the verge of taking office; Yoshida served as foreign minister in his own first three cabinets. He oversaw the adoption of the Constitution of Japan

The Constitution of Japan is the supreme law of Japan. Written primarily by American civilian officials during the occupation of Japan after World War II, it was adopted on 3 November 1946 and came into effect on 3 May 1947, succeeding the Meij ...

before losing office after the election of 1947. He returned to the premiership in 1948, and negotiated the Treaty of San Francisco

The , also called the , re-established peaceful relations between Japan and the Allied Powers on behalf of the United Nations by ending the legal state of war, military occupation and providing for redress for hostile actions up to and inclu ...

, which ended the occupation and saw the restoration of sovereignty to Japan, and a security treaty with the U.S. Yoshida pursued a strategy of concentrating on economic reconstruction while relying on an alliance with the United States for defense, a strategy known as the Yoshida Doctrine

The Yoshida Doctrine was a strategy adopted by Japan after its defeat in 1945 under Prime Minister Shigeru Yoshida, the prime minister 1948–1954. He concentrated upon reconstructing Japan's domestic economy while relying heavily on the security ...

. The last years of his premiership were marked by conflict with Hatoyama, who had by then been depurged. This culminated in Yoshida being ousted and replaced by Hatoyama in 1954.

Yoshida's legacy continued to play an important part in Japanese political life, particularly through his two protégés, Hayato Ikeda

was a Japanese politician who served as prime minister of Japan from 1960 to 1964. He is best known for his Income Doubling Plan, which promised to double the size of Japan's economy in 10 years, and for presiding over the 1964 Tokyo Olympics. ...

and Eisaku Satō

was a Japanese politician who served as prime minister of Japan from 1964 to 1972. He is the third longest-serving Japanese prime minister, and is ranked second by longest uninterrupted service. Satō is best remembered for securing the return ...

, who served as prime ministers from 1960 to 1964 and 1964 to 1972 respectively. Yoshida died in 1967 and received a state funeral. His grandson, Tarō Asō

is a Japanese politician who served as Prime Minister of Japan from 2008 to 2009. A member of the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP), he also served as Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of Finance from 2012 to 2021. He was the longest-serving De ...

, served as prime minister from 2008 to 2009.

Early life and education

Shigeru Yoshida was born on 22 September 1878, in Kanda-Surugadai,

Shigeru Yoshida was born on 22 September 1878, in Kanda-Surugadai, Tokyo

Tokyo, officially the Tokyo Metropolis, is the capital of Japan, capital and List of cities in Japan, most populous city in Japan. With a population of over 14 million in the city proper in 2023, it is List of largest cities, one of the most ...

, the fifth son of Tsuna Takeuchi, a former samurai

The samurai () were members of the warrior class in Japan. They were originally provincial warriors who came from wealthy landowning families who could afford to train their men to be mounted archers. In the 8th century AD, the imperial court d ...

of the Tosa domain

The was a Han (Japan), feudal domain under the Tokugawa shogunate of Edo period Japan, controlling all of Tosa Province in what is now Kōchi Prefecture on the island of Shikoku. It was centered around Kōchi Castle, and was ruled throughout its ...

. Tsuna Takeuchi was a close aide to Taisuke Itagaki in the 1880s and would serve in the first National Diet

, transcription_name = ''Kokkai''

, legislature = 215th Session of the National Diet

, coa_pic = Flag of Japan.svg

, house_type = Bicameral

, houses =

, foundation=29 November 1890(), leader1_type ...

elected in 1890

Events

January

* January 1 – The Kingdom of Italy establishes Eritrea as its colony in the Horn of Africa.

* January 2 – Alice Sanger becomes the first female staffer in the White House.

* January 11 – 1890 British Ultimatum: The Uni ...

. The identity of Yoshida's biological mother is not known. It is likely she was a concubine of Takeuchi and possibly a geisha

{{Culture of Japan, Traditions, Geisha

{{nihongo, Geisha{{efn, {{IPAc-en, lang, ˈ, ɡ, eɪ, ., ʃ, ə, {{IPA, ja, ɡei.ɕa, ɡeː-, lang{{cite book, script-title=ja:NHK日本語発音アクセント新辞典, publisher=NHK Publishing, editor= ...

.

Shortly before Yoshida's birth, his biological father was imprisoned for anti-government conspiracy in connection to the Satsuma Rebellion

The Satsuma Rebellion, also known as the , was a revolt of disaffected samurai against the new imperial government of the Empire of Japan, nine years into the Meiji era. Its name comes from the Satsuma Domain, which had been influential in ...

, and his mother gave birth to him at the house of Kenzō Yoshida, a friend of his father. As young samurai, Tsuna and Kenzō had made names for themselves amidst the decades of unrest around the time of Meiji Restoration

The , referred to at the time as the , and also known as the Meiji Renovation, Revolution, Regeneration, Reform, or Renewal, was a political event that restored Imperial House of Japan, imperial rule to Japan in 1868 under Emperor Meiji. Althoug ...

. Since Takeuchi had several sons and his friend Kenzō Yoshida had none, Yoshida was adopted by Kenzō Yoshida and his wife Kotoko in August 1881. Kenzō Yoshida was a former samurai who had traveled to England as a stowaway in his youth. He then established himself in Yokohama

is the List of cities in Japan, second-largest city in Japan by population as well as by area, and the country's most populous Municipalities of Japan, municipality. It is the capital and most populous city in Kanagawa Prefecture, with a popu ...

as a branch manager for Jardine Matheson

Jardine Matheson Holdings Limited (also known as Jardines) is a Hong Kong–based, Bermuda-domiciled British multinational conglomerate. It has a primary listing on the London Stock Exchange and secondary listings on the Singapore Exchange ...

, before becoming a successful businessman in his own right. Kotoko was the granddaughter of the Edo period

The , also known as the , is the period between 1600 or 1603 and 1868 in the history of Japan, when the country was under the rule of the Tokugawa shogunate and some 300 regional ''daimyo'', or feudal lords. Emerging from the chaos of the Sengok ...

Confucian

Confucianism, also known as Ruism or Ru classicism, is a system of thought and behavior originating in ancient China, and is variously described as a tradition, philosophy, religion, theory of government, or way of life. Founded by Confucius ...

scholar Issai Satō.

Yoshida spent his early childhood in Yokohama. After he graduated from elementary school there in 1889, he was enrolled at Koyo Juku, a prestigious rural boarding school. That same year, Kenzō Yoshida died, and Shigeru inherited a substantial fortune from him. Kotoko subsequently raised Shigeru on the family's estate in Ōiso

file:OISO.jpg, 260px, Ōiso Long Beach resort

is a List of towns in Japan, town located in Kanagawa Prefecture, Japan. , the town had an estimated population of 31,262 and a population density of 1820 persons per km². The total area of the town ...

when he was not at school.

Yoshida spent five years at Koyo Juku. In 1894 he went to Tokyo and spent a year studying at Nihon Gakuen, a school run by the famous educator Jugo Sugiura. He then went on to Higher Commercial School, but soon found he was unsuited for business and dropped out. He then briefly studied at Seisoku Academy and the Tokyo Physics School while preparing for higher school examinations, but he fell ill and had to spend a year at home in Ōiso. Returning to Tokyo in 1897, he entered the prestigious Peers' School, the headed by Prince Atsumaro Konoe. Yoshida advanced to the university department at Peers’ School, which Prince Konoe had established to train diplomats. The university department became defunct after Prince Konoe died in 1904, so Yoshida transferred to Tokyo Imperial University

The University of Tokyo (, abbreviated as in Japanese and UTokyo in English) is a public university, public research university in Bunkyō, Tokyo, Japan. Founded in 1877 as the nation's first modern university by the merger of several Edo peri ...

and graduated with a law degree in 1906. He passed the Foreign Service Entry Exam and entered Japan's diplomatic corps that same year, shortly after Japan's victory in the Russo-Japanese War

The Russo-Japanese War (8 February 1904 – 5 September 1905) was fought between the Russian Empire and the Empire of Japan over rival imperial ambitions in Manchuria and the Korean Empire. The major land battles of the war were fought on the ...

.

Diplomatic career

Yoshida's diplomatic career began with a posting inChina

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. With population of China, a population exceeding 1.4 billion, it is the list of countries by population (United Nations), second-most populous country after ...

, first at the Japanese mission in Tianjin

Tianjin is a direct-administered municipality in North China, northern China on the shore of the Bohai Sea. It is one of the National Central City, nine national central cities, with a total population of 13,866,009 inhabitants at the time of the ...

in November 1906, then in Fengtian (now Shenyang) in 1907. In 1909, Yoshida married Yukiko Makino, the eldest daughter of Nobuaki Makino

Count , was a Japanese politician and imperial court official. As Lord Keeper of the Privy Seal of Japan, Makino served as Emperor Hirohito's chief counselor on the monarch's position in Japanese society and policymaking.

After victory in Wor ...

. That same year he was assigned to Italy

Italy, officially the Italian Republic, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe, Western Europe. It consists of Italian Peninsula, a peninsula that extends into the Mediterranean Sea, with the Alps on its northern land b ...

, and in 1912, he was posted to Andong

Andong () is a Administrative divisions of South Korea, city in South Korea, and the capital of North Gyeongsang Province. It is the largest city in the northern part of the province with a population of 167,821 as of October 2010. The Nakdong Ri ...

in Japanese-ruled Korea, where he served concurrently as secretary to the Governor General Masatake Terauchi

''Gensui (Imperial Japanese Army), Gensui'' Count Terauchi Masatake (), Order of the Bath, GCB (5 February 1852 – 3 November 1919), was a Japanese people, Japanese military officer and politician. He was a ''Gensui (Imperial Japanese Army), Ge ...

. When Terauchi was appointed prime minister in 1916, Yoshida turned down an offer to serve as his personal secretary. He was instead assigned to the Japanese embassy in the United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

, but this appointment was cancelled when the Ministry became aware Yoshida had opposed the Twenty-One Demands

The Twenty-One Demands (; ) was a set of demands made during the World War I, First World War by the Empire of Japan under Prime Minister of Japan, Prime Minister Ōkuma Shigenobu to the Government of the Chinese Republic, government of the Re ...

, which he thought undermined the Japanese policy in China by alienating the Western powers and provoking Chinese opposition. Yoshida was instead made chief of the documents section the following year and in 1918 he was appointed consul in Jinan

Jinan is the capital of the province of Shandong in East China. With a population of 9.2 million, it is one of the largest cities in Shandong in terms of population. The area of present-day Jinan has played an important role in the history of ...

, China.

In 1919, he was part of the Japanese delegation to the Paris Peace Conference Agreements and declarations resulting from meetings in Paris include:

Listed by name

Paris Accords

may refer to:

* Paris Accords, the agreements reached at the end of the London and Paris Conferences in 1954 concerning the post-war status of Germ ...

, as secretary to his father-in-law Makino, one of the Japanese plenipotentiaries. When the conference concluded in 1920, he was assigned as first secretary to the Japanese embassy in the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Northwestern Europe, off the coast of European mainland, the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

. In 1922, he returned to China and served as consul in Tianjin until 1925, then as Consul General in Fengtian until 1928.

In March 1928, Yoshida was first appointed minister to Sweden

Sweden, formally the Kingdom of Sweden, is a Nordic countries, Nordic country located on the Scandinavian Peninsula in Northern Europe. It borders Norway to the west and north, and Finland to the east. At , Sweden is the largest Nordic count ...

, Norway

Norway, officially the Kingdom of Norway, is a Nordic countries, Nordic country located on the Scandinavian Peninsula in Northern Europe. The remote Arctic island of Jan Mayen and the archipelago of Svalbard also form part of the Kingdom of ...

, and Denmark

Denmark is a Nordic countries, Nordic country in Northern Europe. It is the metropole and most populous constituent of the Kingdom of Denmark,, . also known as the Danish Realm, a constitutionally unitary state that includes the Autonomous a ...

, but before assuming the post he was appointed vice minister for foreign affairs in July of the same year, after having recommended himself to the Prime Minister Giichi Tanaka. Tanaka served concurrently as minister for foreign affairs. During this time, Yoshida supported increasing Japanese influence in China, and advocated for the independence of Manchuria

Manchuria is a historical region in northeast Asia encompassing the entirety of present-day northeast China and parts of the modern-day Russian Far East south of the Uda (Khabarovsk Krai), Uda River and the Tukuringra-Dzhagdy Ranges. The exact ...

and Mongolia

Mongolia is a landlocked country in East Asia, bordered by Russia to the north and China to the south and southeast. It covers an area of , with a population of 3.5 million, making it the world's List of countries and dependencies by po ...

to weaken the Republic of China. He acquainted Ichiro Hatoyama

, also known mononymously as , is a Japanese former professional baseball outfielder who played for 28 seasons. He played the first nine years of his career with the Orix Buffaloes, Orix BlueWave of Nippon Professional Baseball (NPB), and the ...

, who was chief cabinet secretary under Tanaka. Yoshida remained in his post when Tanaka was replaced as prime minister by Osachi Hamaguchi and as foreign minister by Kijūrō Shidehara

Baron was a Japanese diplomat and politician who served as prime minister of Japan from 1945 to 1946. He was a leading proponent of pacifism in Japan before and after World War II.

Born to a wealthy Osaka family, Shidehara studied law at Tok ...

in July 1929, until he was appointed ambassador to Italy

Italy, officially the Italian Republic, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe, Western Europe. It consists of Italian Peninsula, a peninsula that extends into the Mediterranean Sea, with the Alps on its northern land b ...

in December 1930. He returned to Japan in 1932 and, after having turned down the ambassadorship to the United States, for which he considered himself unsuitable, held a nebulous role as an ambassador-in-waiting. He undertook some foreign tours on behalf of the ministry and notably developed a warm relationship with the American ambassador Joseph Grew. Yoshida formally retired from the ministry in 1935.

In the aftermath of the February 26 incident of 1936, Prince Fumimaro Konoe

was a Japanese politician who served as Prime Minister of Japan from 1937 to 1939 and from 1940 to 1941. He presided over the Japanese invasion of China in 1937 and breakdown in relations with the United States, which shortly after his t ...

contacted Yoshida to request that he'd help persuade Koki Hirota

Koki may refer to:

Places

*Koki (village), a medieval aul in Ingushetia

* Koki, Comoros, a village on the island of Anjouan in the Comoros

*Koki, Senegal, a town in the Louga region of Senegal

* Koki, Estonia, village in Lümanda Parish, Saare ...

accept the premiership. Yoshida assisted Hirota in the cabinet formation and was himself considered for the post of foreign minister. However, he was included on a list of potential cabinet ministers unacceptable to the army presented by the incoming War Minister Hisaichi Terauchi

Count was a '' Gensui'' (or field marshal) in the Imperial Japanese Army, commander of the Southern Expeditionary Army Group during World War II.

Biography Early military career

Terauchi was born in Tokyo Prefecture, and was the eldest son of ...

. This prevented his appointment. Instead he became ambassador to the United Kingdom. After his ambassadorship to the United Kingdom ended in 1938, he retired, again, from the diplomatic service.

During the Pacific War

Although considered a "hawk" on China, Yoshida was firmly against war with the United States and United Kingdom. Despite holding no official positions duringWorld War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, he was active in trying to prevent war with the Allies, and then to try to bring about an early end of the war, allying himself with Prince Fumimaro Konoe

was a Japanese politician who served as Prime Minister of Japan from 1937 to 1939 and from 1940 to 1941. He presided over the Japanese invasion of China in 1937 and breakdown in relations with the United States, which shortly after his t ...

.

Right before the Pacific War

The Pacific War, sometimes called the Asia–Pacific War or the Pacific Theatre, was the Theater (warfare), theatre of World War II fought between the Empire of Japan and the Allies of World War II, Allies in East Asia, East and Southeast As ...

began, Yoshida joined Konoe in unsuccessfully attempting to deescalate the situation. During the war, Yoshida continued to associate with Konoe in trying to get the government to negotiate a peace with the Allies. In April 1945, he was arrested and briefly imprisoned over his association with Prince Konoe.

Post-war period and premiership

Following the

Following the Japanese surrender

The surrender of the Empire of Japan in World War II was announced by Emperor Hirohito on 15 August and formally signed on 2 September 1945, ending the war. By the end of July 1945, the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) was incapable of condu ...

in August 1945, the Allied occupation of the country began. Yoshida was brought out of retirement to serve as foreign minister in the cabinet of Prince Higashikuni after the resignation of Mamoru Shigemitsu

was a Japanese diplomat who served as Minister of Foreign Affairs three times during and after World War II and as Deputy Prime Minister. As a civilian plenipotentiary representing the Japanese government, Shigemitsu cosigned the Japanese In ...

in September 1945. At that point, the main function of the foreign minister was to liaise with the occupation authority: the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers

The Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers (), or SCAP, was the title held by General Douglas MacArthur during the United States-led Allied occupation of Japan following World War II. It issued SCAP Directives (alias SCAPIN, SCAP Index Number) ...

. As such, Yoshida came into regular contact with General Douglas MacArthur

Douglas MacArthur (26 January 18805 April 1964) was an American general who served as a top commander during World War II and the Korean War, achieving the rank of General of the Army (United States), General of the Army. He served with dis ...

. When Prince Higashikuni resigned Yoshida was approached by the Lord Keeper of the Privy Seal Koichi Kido to become prime minister, but he turned him down and suggested Kijuro Shidehara for the post, who was duly appointed. Yoshida remained foreign minister in the Shidehara Cabinet.

The first post-war election in April 1946 brought a plurality of the seats in the Diet to the Liberal Party

The Liberal Party is any of many political parties around the world.

The meaning of ''liberal'' varies around the world, ranging from liberal conservatism on the right to social liberalism on the left. For example, while the political systems ...

led by Yoshida's old friend Ichirō Hatoyama

was a Japanese politician who served as Prime Minister of Japan, prime minister of Japan from 1954 to 1956. During his tenure he oversaw the formation of the Liberal Democratic Party (Japan), Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) and restored official ...

. Hatoyama was expected to become prime minister, but was abruptly purged

In history, religion and political science, a purge is a position removal or execution of people who are considered undesirable by those in power from a government, another, their team leaders, or society as a whole. A group undertaking such an ...

by the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers on the eve of his appointment. Hatoyama approached Yoshida to take his place as prime minister and leader of the Liberal Party, despite Yoshida not even being a member of the party. Although reluctant, Yoshida eventually accepted, becoming prime minister of Japan on 22 May 1946. In the same month he joined the Liberal Party and was first made chairman of the general council before being formally elected party president four months later.

First premiership

Yoshida's first cabinet was based on a coalition between the Liberal Party and the Japan Progressive Party led by former prime minister Shidehara. The cabinet notably included Shidehara as minister without portfolio and

Yoshida's first cabinet was based on a coalition between the Liberal Party and the Japan Progressive Party led by former prime minister Shidehara. The cabinet notably included Shidehara as minister without portfolio and Tanzan Ishibashi

was a Japanese journalist and politician who served as prime minister of Japan from 1956 to 1957.

Born in Tokyo, Ishibashi became a journalist after graduating from Waseda University in 1907. In 1911, he joined the ''Tōyō Keizai Shimpo'' ("Ea ...

as finance minister. Yoshida remained as foreign minister concurrently. The cabinet implemented several reforms based on occupation directives, the scope of which Yoshida personally resisted. Yoshida oversaw the adoption of the post-war Constitution of Japan

The Constitution of Japan is the supreme law of Japan. Written primarily by American civilian officials during the occupation of Japan after World War II, it was adopted on 3 November 1946 and came into effect on 3 May 1947, succeeding the Meij ...

, which was promulgated on 3 November 1946 and came into effect on 3 May 1947. Yoshida, a warm supporter of the imperial institution, did not believe that the revised constitution fundamentally changed the ''kokutai

is a concept in the Japanese language translatable as "system of government", "sovereignty", "national identity, essence and character", "national polity; body politic; national entity; basis for the Emperor's sovereignty; Japanese constitut ...

''.

In terms of economic policy, Yoshida and Finance Minister Ishibashi initiated a "priority production system" (傾斜生産方式, ''keisha seisan hoshiki'') designed to increase production of steel and coal as they were essential for reconstruction. This system was based on the theories of Hiromi Arisawa, an economic expert who advised Yoshida.

The cabinet had to face significant social unrest due to the impoverished situation and labour disputes at the time. These issues came to a head when the labour movement called for a general strike

A general strike is a strike action in which participants cease all economic activity, such as working, to strengthen the bargaining position of a trade union or achieve a common social or political goal. They are organised by large coalitions ...

to take place on 1 February 1947. Yoshida believed that the strike would be an economic catastrophe, which could create the conditions for a communist revolution. The situation was resolved when General MacArthur prohibited the strike before it could take place on January 31. Afterwards, MacArthur communicated to Yoshida that a new election should be called.

Opposition

The election was held in April 1947 election. Yoshida himself stood for election for the first time, choosing for his constituencyKochi Prefecture

Kochi ( , ), formerly known as Cochin ( ), is a major port city along the Malabar Coast of India bordering the Laccadive Sea. It is part of the district of Ernakulam in the state of Kerala. The city is also commonly referred to as Ernakulam ...

, where his family originated. While Yoshida won his election, a plurality of the seats in the House of Representatives went to the Japan Socialist Party

The was a major socialist and progressive political party in Japan which existed from 1945 to 1996. The party was the primary representative of the Japanese left and main opponent of the right-wing Liberal Democratic Party for most of its ex ...

. Yoshida was approached by Tetsu Katayama

was a Japanese politician who served as prime minister of Japan from 1947 to 1948. He was the first socialist to serve as Japanese prime minister, and the last non-member of the Liberal Democratic Party or its forerunners to serve until 1993.

...

and Suehiro Nishio, respectively chairman and secretary general of the Socialist Party, about including the Liberal Party in a grand coalition

A grand coalition is an arrangement in a multi-party parliamentary system in which the two largest political party, political parties of opposing political spectrum, political ideologies unite in a coalition government.

Causes of a grand coali ...

, but he declined because he considered the left-wing of the Socialist Party too close to the communists. The Socialists instead formed a coalition with only the Democratic Party, which had been formed by merging the Progressive Party with defectors led by Hitoshi Ashida

was a Japanese politician who served as Prime Minister of Japan in 1948. He was a prominent figure in the immediate postwar political landscape, but was forced to resign his leadership responsibilities after a corruption scandal (Shōwa Denkō J ...

from the Liberal Party, and the National Cooperative Party

The was a centrist political party in Japan.

History

The party was established on 8 March 1947 as a merger of the Cooperative Democratic Party and the National Party following seven months of talks.Haruhiro Fukui (1985) ''Political parties of ...

. Yoshida was succeeded by Tetsu Katayama

was a Japanese politician who served as prime minister of Japan from 1947 to 1948. He was the first socialist to serve as Japanese prime minister, and the last non-member of the Liberal Democratic Party or its forerunners to serve until 1993.

...

on 24 May 1947.

Yoshida and his party thus entered the opposition. Yoshida used this time to strengthen his party and consolidate his leadership. Shortly after the Katayama Cabinet was replaced by the Ashida Cabinet in March 1948, the Liberal Party formed into the Democratic Liberal Party by merging with a breakaway group led by Shidehara from the Democratic Party.

Second premiership

After the fall of the Ashida Cabinet, Yoshida returned to the post of prime minister on 15 October 1948. He soon called anelection

An election is a formal group decision-making process whereby a population chooses an individual or multiple individuals to hold Public administration, public office.

Elections have been the usual mechanism by which modern representative d ...

which was held in January 1949; his party won in a landslide.

In order to fill the places left by purged politicians, Yoshida had recruited a large number of former bureaucrats to serve as candidates for the party, including Hayato Ikeda

was a Japanese politician who served as prime minister of Japan from 1960 to 1964. He is best known for his Income Doubling Plan, which promised to double the size of Japan's economy in 10 years, and for presiding over the 1964 Tokyo Olympics. ...

, Eisaku Sato and Katsuo Okazaki

was a Japanese diplomat, politician and sportsman. He served as the Japanese foreign minister in the 1950s. He was also the final – and only Japanese – chairman of the Shanghai Municipal Council.

Early life

Okazaki was born on 10 July 189 ...

. Many of these were elected for the first time in the 1949 election. This group would be the core of Yoshida’s own informal faction, known as the ”Yoshida School."

Dodge Line

In February after the election,

In February after the election, Joseph Dodge

Joseph Morrell Dodge (November 18, 1890 – December 2, 1964) was a chairman of the Detroit Bank, now Comerica. He later served as an economic adviser for postwar economic stabilization programs in Germany and Japan, headed the American delegatio ...

arrived in Japan as financial adviser to SCAP with a mission to stabilize the Japanese economy, which was suffering from rampant inflation and other problems. The Dodge Line

The Dodge Line or Dodge Plan was a financial and monetary contraction policy drafted by American economist Joseph Dodge for Japan to gain economic independence and stamp out inflation after World War II. It was announced on March 7, 1949. The D ...

, as the plan advocated by Dodge would be called, prescribed strict austerity measures that significantly curtailed public spending and government subsidies.

Yoshida appointed Hayato Ikeda finance minister later the same month. Although Yoshida and Ikeda had apprehensions about the Dodge Line, they had no choice but to implement occupation policy. The plan was successful in ending hyperinflation, but it also caused severe short-term hardship. The decreased money supply led to a wave of bankruptcies and increased unemployment. Furthermore, spending cuts necessitated mass layoffs in the public sector.

This situation continued until the outbreak of the Korean War

The Korean War (25 June 1950 – 27 July 1953) was an armed conflict on the Korean Peninsula fought between North Korea (Democratic People's Republic of Korea; DPRK) and South Korea (Republic of Korea; ROK) and their allies. North Korea was s ...

in June 1950. The war led to an economic boom stimulated by demand for goods and services from Japan by the American forces in Korea. Yoshida described this as a ”gift from the gods.”

Treaty of San Francisco

In April 1950 Yoshida sent Finance Minister Ikeda, together with Ikeda’s secretary

In April 1950 Yoshida sent Finance Minister Ikeda, together with Ikeda’s secretary Kiichi Miyazawa

was a Japanese politician who served as prime minister of Japan from 1991 to 1993.

Born in Tokyo, Miyazawa graduated from Tokyo Imperial University with a law degree, and in 1942 joined the Ministry of Finance. He was first elected to the Nati ...

and Yoshida’s confidant Jiro Shirasu Jiro may refer to:

* Jiro (given name), including people with the name

* Jiro (musician) (born 1972), Japanese rock musician

*Jiro Ono (chef)

is a Japanese retired sushi chef and owner of Sukiyabashi Jiro, a sushi restaurant in Ginza, Chū� ...

, to Washington. On the pretext of an economic mission, Ikeda conveyed the message that the Japanese government would accept a continued U. S. military presence after the occupation in order to ensure Japan’s security and make an early peace treaty possible. President Truman assigned the responsibility of negotiating a peace treaty to John Foster Dulles

John Foster Dulles (February 25, 1888 – May 24, 1959) was an American politician, lawyer, and diplomat who served as United States secretary of state under President Dwight D. Eisenhower from 1953 until his resignation in 1959. A member of the ...

. Dulles met with Yoshida in Tokyo for the first time in June 1950, only days before the outbreak of the Korean War. They subsequently met several times to negotiate the treaty.

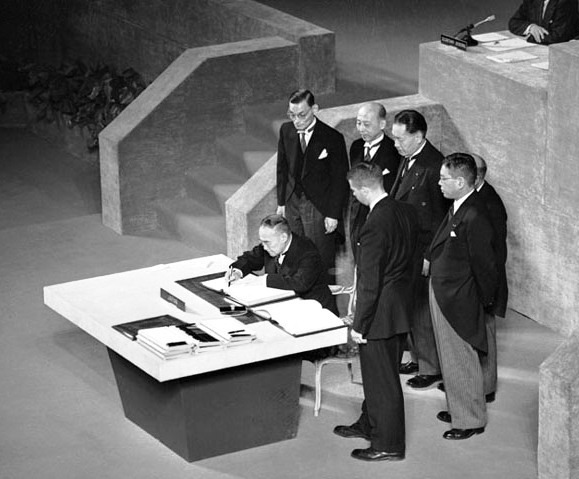

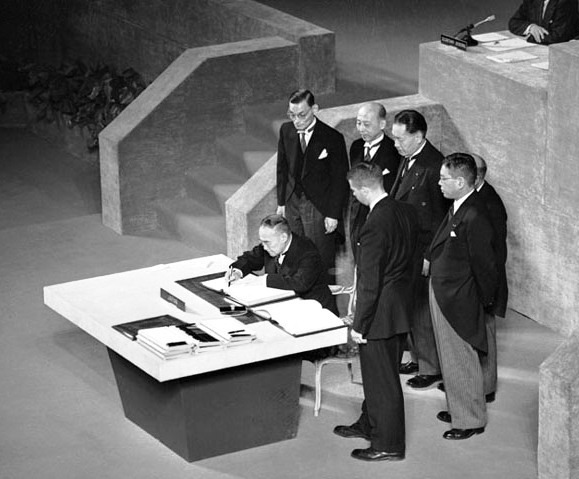

In September 1951, Yoshida signed the Treaty of San Francisco

The , also called the , re-established peaceful relations between Japan and the Allied Powers on behalf of the United Nations by ending the legal state of war, military occupation and providing for redress for hostile actions up to and inclu ...

, a peace treaty with the Allies that would serve as a formal peace agreement and bring about the end of the occupation of Japan when the treaty took effect in April 1952. Yoshida also signed the Security Treaty, which inaugurated the post-war military alliance between Japan and the United States. During a stopover in Hawaii

Hawaii ( ; ) is an island U.S. state, state of the United States, in the Pacific Ocean about southwest of the U.S. mainland. One of the two Non-contiguous United States, non-contiguous U.S. states (along with Alaska), it is the only sta ...

on the way back from San Francisco, he also paid a visit to Pearl Harbor

Pearl Harbor is an American lagoon harbor on the island of Oahu, Hawaii, west of Honolulu. It was often visited by the naval fleet of the United States, before it was acquired from the Hawaiian Kingdom by the U.S. with the signing of the Reci ...

.

Yoshida Doctrine

TheYoshida Doctrine

The Yoshida Doctrine was a strategy adopted by Japan after its defeat in 1945 under Prime Minister Shigeru Yoshida, the prime minister 1948–1954. He concentrated upon reconstructing Japan's domestic economy while relying heavily on the security ...

was a strategy adopted by Japan under Yoshida starting in 1951. He concentrated upon reconstructing Japan's domestic economy while relying heavily on the security alliance with the United States. Firstly, Japan is firmly allied with the United States in the Cold War

The Cold War was a period of global Geopolitics, geopolitical rivalry between the United States (US) and the Soviet Union (USSR) and their respective allies, the capitalist Western Bloc and communist Eastern Bloc, which lasted from 1947 unt ...

against communism. Secondly, Japan relies on American military strength and limits its own defense forces to a minimum. Thirdly, Japan emphasizes economic diplomacy in its world affairs. The Yoshida doctrine was accepted by the United States; the actual term was coined in 1977. The economic dimension was fostered by Hayato Ikeda

was a Japanese politician who served as prime minister of Japan from 1960 to 1964. He is best known for his Income Doubling Plan, which promised to double the size of Japan's economy in 10 years, and for presiding over the 1964 Tokyo Olympics. ...

who served as his finance minister and later was prime minister. The Yoshida Doctrine shaped Japanese foreign policy into the 21st century. Most historians argue the policy was wise and successful, but a minority criticize it as naïve and inappropriate.

Conflict with Hatoyama

Before the signing of the Treaty of San Francisco Ichirō Hatoyama had been released from the purge. Since Yoshida had originally become prime minister as a replacement for Hatoyama, many expected him to step down in Hatoyama's favour, but by this time Yoshida had become a well-established politician in his own right and had no intention to retire. This led to a conflict with Hatoyama.

According to CIA files that were declassified in 2005, there was a 1952 plot to assassinate Yoshida and replace him with Ichirō Hatoyama as prime minister. The plot was led by

Before the signing of the Treaty of San Francisco Ichirō Hatoyama had been released from the purge. Since Yoshida had originally become prime minister as a replacement for Hatoyama, many expected him to step down in Hatoyama's favour, but by this time Yoshida had become a well-established politician in his own right and had no intention to retire. This led to a conflict with Hatoyama.

According to CIA files that were declassified in 2005, there was a 1952 plot to assassinate Yoshida and replace him with Ichirō Hatoyama as prime minister. The plot was led by Takushiro Hattori

was an Imperial Japanese Army officer and government official. During World War II, he alternately served as the chief of the Army General Staff's Operations Section and Secretary to Prime Minister Hideki Tojo. After the war ended, he served as an ...

, who served as an Imperial Japanese Army

The Imperial Japanese Army (IJA; , ''Dai-Nippon Teikoku Rikugun'', "Army of the Greater Japanese Empire") was the principal ground force of the Empire of Japan from 1871 to 1945. It played a central role in Japan’s rapid modernization during th ...

officer, and had the support of 500,000 Japanese people.

Dissatisfaction with his leadership led to the defection of many Diet members from his party to the new Democratic Party, causing his cabinet to resign on December 7, 1954, rather than face a no-confidence vote. He was replaced by Ichirō Hatoyama

was a Japanese politician who served as Prime Minister of Japan, prime minister of Japan from 1954 to 1956. During his tenure he oversaw the formation of the Liberal Democratic Party (Japan), Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) and restored official ...

on December 10, 1954. Yoshida resigned as party president in favour of Taketora Ogata

was a Japanese journalist, Vice President of the Asahi Shimbun newspaper and later a politician. During the war, he joined the Imperial Rule Assistance Association. After the end of the war, he was purged from public service. Later, he became t ...

at the same time. He remained in the Diet until his retirement in 1963.

Later years and legacy

After his resignation he spent most of his time at his villa in Oiso, though he remained a member of the House of Representatives until1963

Events January

* January 1 – Bogle–Chandler case: Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation scientist Dr. Gilbert Bogle and Mrs. Margaret Chandler are found dead (presumed poisoned), in bushland near the Lane Cove ...

. Yoshida served a president of the America-Japan Society from 1960 and as chancellor of Kogakkan University from 1962. He was also president of the Japanese Association of Zoos and Aquariums

The Japanese Association of Zoos and Aquariums (JAZA, in Japanese: , ''Nihon Dōbutsu-en Suizokukan Kyōkai'') is an organisation for the zoo and aquarium community in Japan. As of April 30, 2021, JAZA has 90 member zoos and 50 member aquariums. J ...

.

Shigeru Yoshida died on 20 October 1967 at his home in Oiso. He was baptized on his deathbed, having hidden his Catholicism

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

throughout most of his life. His funeral was held in St. Mary's Cathedral, Tokyo and he was buried at Aoyama Cemetery

is a cemetery in Aoyama, Tokyo, Aoyama, Minato, Tokyo, Minato, Tokyo, Japan, managed by the Tokyo Metropolitan Government. The cemetery is known for its cherry blossoms and is popular during the season of .

History

The cemetery was origin ...

.

His state funeral was held in Nippon Budokan

The , often shortened to simply Budokan, is an indoor arena in Chiyoda, Tokyo, Japan. It was originally built for the inaugural Olympic judo competition in the 1964 Summer Olympics. The Budokan was a popular venue for Japanese professional wres ...

on 31 October 1967 in the presence of the Crown Prince

A crown prince or hereditary prince is the heir apparent to the throne in a royal or imperial monarchy. The female form of the title, crown princess, is held by a woman who is heir apparent or is married to the heir apparent.

''Crown prince ...

and Princess

Princess is a title used by a female member of a regnant monarch's family or by a female ruler of a principality. The male equivalent is a prince (from Latin '' princeps'', meaning principal citizen). Most often, the term has been used for ...

.

Under Yoshida's leadership, Japan began to rebuild its lost industrial infrastructure and placed a premium on unrestrained economic growth. Many of these concepts still impact Japan's political and economic policies. However, since the 1970s environmental movement, the bursting of Japan's economic bubble, and the end of the Cold War, Japan has been struggling to redefine its national goals. Yoshida has long been regarded as prioritising the economy over defense, but recent years have seen a reevaluation of this viewpoint.

In his 1982 book "Leaders", US President Richard Nixon

Richard Milhous Nixon (January 9, 1913April 22, 1994) was the 37th president of the United States, serving from 1969 until Resignation of Richard Nixon, his resignation in 1974. A member of the Republican Party (United States), Republican ...

praised Yoshida as one of the greatest world leaders during his lifetime for his role in Japan's post-WWII economic miracle.

Personal life

In 1909, Yoshida married Makino Yukiko, the eldest daughter ofMakino Nobuaki

Count , was a Japanese politician and imperial court official. As Lord Keeper of the Privy Seal of Japan, Makino served as Emperor Hirohito's chief counselor on the monarch's position in Japanese society and policymaking.

After victory in W ...

.Lockhart, Charles: ''Protecting the Elderly: How Culture Shapes Social Policy'' They had four children: Sakurako, Kenichi, Kazuko, and Masao. Two of Yoshida's grandchildren are Tarō Asō

is a Japanese politician who served as Prime Minister of Japan from 2008 to 2009. A member of the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP), he also served as Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of Finance from 2012 to 2021. He was the longest-serving De ...

, who served as the 92nd prime minister of Japan from 2008 to 2009, and Nobuko Asō, who later married Prince Tomohito of Mikasa

was a member of the Imperial House of Japan and the eldest son of Takahito, Prince Mikasa and Yuriko, Princess Mikasa. He was a first cousin of Emperor Akihito, and was formerly sixth in the line of succession to the Japanese throne and the h ...

, a first cousin of Emperor Akihito

Akihito (born 23 December 1933) is a member of the Imperial House of Japan who reigned as the 125th emperor of Japan from 1989 until 2019 Japanese imperial transition, his abdication in 2019. The era of his rule was named the Heisei era, Hei ...

.

Honours

* Grand Cordon of theOrder of the Rising Sun

The is a Japanese honors system, Japanese order, established in 1875 by Emperor Meiji. The Order was the first national decoration awarded by the Japanese government, created on 10 April 1875 by decree of the Council of State. The badge feat ...

(29 April 1940)''From the corresponding article in the Japanese Wikipedia''

* Grand Cordon of the Order of the Chrysanthemum

is Japan's highest Order (decoration), order. The Grand Cordon of the Order was established in 1876 by Emperor Meiji of Japan; the Collar of the Order was added on 4 January 1888. Unlike European counterparts, the order may be Posthumous award, ...

(29 April 1964)

* Collar of the Order of the Chrysanthemum

is Japan's highest Order (decoration), order. The Grand Cordon of the Order was established in 1876 by Emperor Meiji of Japan; the Collar of the Order was added on 4 January 1888. Unlike European counterparts, the order may be Posthumous award, ...

(20 October 1967; posthumous)

* Junior First Rank

The court ranks of Japan, also known in Japanese language, Japanese as ''ikai'' (位階), are indications of an individual's court rank in Japan based on the system of the Nation, state. ''Ikai'' as a system was the indication of the rank of burea ...

(20 October 1967; posthumous)

* Golden Pheasant Award

The is the highest award for adult leaders in the Scout Association of Japan. It is awarded by the Chief Scout of Japan, awarded for eminent achievement and meritorious service to the Association for a period of at least twenty years. It may be ...

of the Scout Association of Japan

The is the major Scouting organization of Japan. Starting with boys only, the organization was known as Boy Scouts of Japan from 1922 to 1971, and as Boy Scouts of Nippon from 1971 to 1995, when it became coeducational in all sections, leading ...

(1967)

References

Bibliography

* * Edström, Bert. ''Yoshida Shigeru and the Foundation of Japan's Postwar Foreign Policy.'' * * Takashi Hirose ( 広瀬隆); 『私物国家 日本の黒幕の系図』 Tokyo:Kobunsha

is a Japanese publishing company. It publishes literature, manga novels, and women's magazines.

Company history

Kobunsha was established on October 1, 1945, and belongs to the Kodansha group.

The company has published Japanese authors such a ...

(1997) Genealogy14

* Iriye, Akira. "Japan Returns to the World: Yoshida Shigeru and His Legacy." ''The Diplomats, 1939-1979'' (Princeton University Press, 2019) pp. 321–336online

* * * Rodan, Garry, Hewison, Kevin and Robison, Richard. (1997). ''The Political Economy of South-East Asia: An Introduction.'' Melbourne:

Oxford University Press

Oxford University Press (OUP) is the publishing house of the University of Oxford. It is the largest university press in the world. Its first book was printed in Oxford in 1478, with the Press officially granted the legal right to print books ...

. OCLC 464661946

* McGrew, Anthony and Christopher Book.'' (1998) ''Asia-Pacific in the New World Order.'' London:

Routledge

Routledge ( ) is a British multinational corporation, multinational publisher. It was founded in 1836 by George Routledge, and specialises in providing academic books, academic journals, journals and online resources in the fields of the humanit ...

. ; OCLC 60184921

* * * * * * *

External links

* *OSS Biographical Report on Yoshida dated January 1945

, - , - , - {{DEFAULTSORT:Yoshida, Shigeru 1878 births 1967 deaths 20th-century prime ministers of Japan Ambassadors of Japan to Italy Ambassadors of Japan to the United Kingdom Ministers for foreign affairs of Japan Honorary Knights Commander of the Royal Victorian Order Japanese anti-communists Japanese prisoners and detainees Japanese Roman Catholics Japanese Christians Liberal Democratic Party (Japan) politicians Democratic Liberal Party (Japan) politicians Liberal Party (Japan, 1945) politicians Members of the House of Peers (Japan) Members of the House of Representatives (Japan) Politicians from Kōchi Prefecture People from Chiyoda, Tokyo People from Yokosuka, Kanagawa People of the Korean War Politicians from Tokyo Prisoners and detainees of Japan University of Tokyo alumni