Shifting (syntax) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

In

The two constituency-based trees show a flat VP that allows n-ary branching (as opposed to just binary branching). The two dependency-based trees show the same VP. Regardless of whether one chooses the constituency- or the dependency-based analysis, the important thing about these examples is the relative flatness of the structure. This flatness results in a situation where shifting does not necessitate a discontinuity (i.e. no long distance dependency), for there can be no crossing lines in the trees. The following trees further illustrate the point:

::

The two constituency-based trees show a flat VP that allows n-ary branching (as opposed to just binary branching). The two dependency-based trees show the same VP. Regardless of whether one chooses the constituency- or the dependency-based analysis, the important thing about these examples is the relative flatness of the structure. This flatness results in a situation where shifting does not necessitate a discontinuity (i.e. no long distance dependency), for there can be no crossing lines in the trees. The following trees further illustrate the point:

:: Again due to the flatness of structure, shifting does not result in a discontinuity. In this example, both orders are acceptable because there is little difference in the relative weight between the two constituents that switch positions.

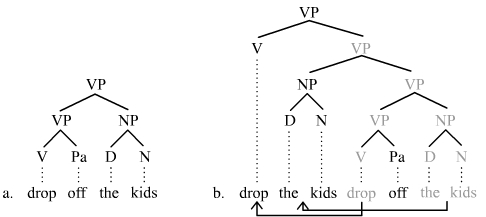

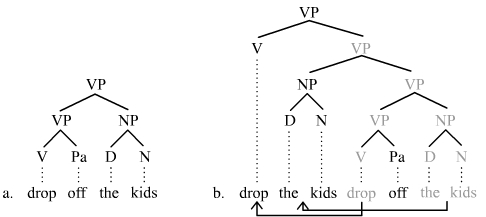

An alternative analysis of shifting is necessary in a constituency grammar that posits strictly binary branching structures. The more layered binary branching structures would result in crossing lines in the tree, which means movement (or copying) is necessary to avoid these crossing lines. The following trees are (merely) representative of the type of analysis that one might assume given strictly binary branching structures:

::

Again due to the flatness of structure, shifting does not result in a discontinuity. In this example, both orders are acceptable because there is little difference in the relative weight between the two constituents that switch positions.

An alternative analysis of shifting is necessary in a constituency grammar that posits strictly binary branching structures. The more layered binary branching structures would result in crossing lines in the tree, which means movement (or copying) is necessary to avoid these crossing lines. The following trees are (merely) representative of the type of analysis that one might assume given strictly binary branching structures:

:: The analysis shown with the trees assumes binary branching and leftward movement only. Given these restrictions, two instances of movement might be necessary to accommodate the surface order seen in tree b. The material in light gray represents copies that must be deleted in the phonological component.

This sort of analysis of shifting has been criticized by

The analysis shown with the trees assumes binary branching and leftward movement only. Given these restrictions, two instances of movement might be necessary to accommodate the surface order seen in tree b. The material in light gray represents copies that must be deleted in the phonological component.

This sort of analysis of shifting has been criticized by

A Dependency Grammar of English: An Introduction and Beyond

Amsterdam: John Benjamins. https://doi.org/10.1075/z.224 {{Syntax Word order Syntax

syntax

In linguistics, syntax ( ) is the study of how words and morphemes combine to form larger units such as phrases and sentences. Central concerns of syntax include word order, grammatical relations, hierarchical sentence structure (constituenc ...

, shifting occurs when two or more constituents appearing on the same side of their common head

A head is the part of an organism which usually includes the ears, brain, forehead, cheeks, chin, eyes, nose, and mouth, each of which aid in various sensory functions such as sight, hearing, smell, and taste. Some very simple ani ...

exchange positions in a sense to obtain non-canonical order. The most widely acknowledged type of shifting is heavy NP shift, but shifting involving a heavy NP is just one manifestation of the shifting mechanism. Shifting occurs in most if not all European languages, and it may in fact be possible in all natural languages including sign languages

Sign languages (also known as signed languages) are languages that use the visual-manual modality to convey meaning, instead of spoken words. Sign languages are expressed through manual articulation in combination with non-manual markers. Sig ...

. Shifting is not inversion, and inversion is not shifting, but the two mechanisms are similar insofar as they are both present in languages like English that have relatively strict word order. The theoretical analysis of shifting varies in part depending on the theory of sentence structure that one adopts. If one assumes relatively flat structures, shifting does not result in a discontinuity. Shifting is often motivated by the relative weight of the constituents involved. The weight of a constituent is determined by a number of factors: e.g., number of words, contrastive focus, and semantic

Semantics is the study of linguistic Meaning (philosophy), meaning. It examines what meaning is, how words get their meaning, and how the meaning of a complex expression depends on its parts. Part of this process involves the distinction betwee ...

content.

Basic examples

Shifting is illustrated with the following pairs of sentences. The first sentence of each pair shows what can be considered canonical order, whereas the second gives an alternative order that results from shifting: ::I gave the books which my uncle left to me as part of his inheritance to her. :: I gave to her the books which my uncle left to me as part of his inheritance. The first sentence with canonical order, where the object noun phrase (NP) precedes the oblique prepositional phrase (PP), is marginal due to the relative 'heaviness' of the NP compared to the PP. The second sentence, which shows shifting, is better because it has the lighter PP preceding the much heavier NP. The following examples illustrate shifting with particle verbs: ::He picked it up. (compare: *He picked up it.) ::He picked up the flashlight. ::John took him on. (compare: *John took on him.) ::John took on the new player. When the object of the particle verb is a pronoun, the pronoun must precede the particle, whereas when the object is an NP, the particle can precede the NP. Each of the two constituents involved is said to shift, whereby this shifting is motivated by the weight of the two relative to each other. In English verb phrases, heavier constituents tend to follow lighter constituents. The following examples illustrate shifting using pronouns, clauses, and PPs: ::She said that to her friends. ::She said to her friends that she had solved the problem. ::They hid that from me. ::They hid from me that I was going to pass the course. When the pronoun appears, it is much lighter than the PP, so it precedes the PP. But if the full clause appears, it is heavier than the PP and can therefore follow it.Further examples

Thesyntactic category

A syntactic category is a syntactic unit that theories of syntax assume. Word classes, largely corresponding to traditional parts of speech (e.g. noun, verb, preposition, etc.), are syntactic categories. In phrase structure grammars, the ''phrasa ...

of the constituents involved in shifting is not limited; they can even be of the same type, e.g.

::It happened on Tuesday due to the weather.

::It happened due to the weather on Tuesday.

::Sam considers him a cheater.

::Sam considers a cheater anyone who used Wikipedia.

In the first pair, the shifted constituents are PPs, and in the second pair, the shifted constituents are NPs. The second pair illustrates again that shifting is often motivated by the relative weight of the constituents involved; the NP ''anyone who used Wikipedia'' is heavier than the NP ''a cheater''.

The examples so far have shifting occurring in verb phrases. Shifting is not restricted to verb phrases. It can also occur, for instance, in NPs:

::the book on the shelf about linguistics

::the book about linguistics on the second shelf down from top

::the picture of him that I found

::the picture that I found of that old friend of mine with funny hair

These examples again illustrate shifting that is motivated by the relative weight of the constituents involved. The heavier of the two constituents prefers to appear further to the right.

The example sentences above all have the shifted constituents appearing after their head

A head is the part of an organism which usually includes the ears, brain, forehead, cheeks, chin, eyes, nose, and mouth, each of which aid in various sensory functions such as sight, hearing, smell, and taste. Some very simple ani ...

(see below). Constituents that precede their head can also shift, e.g.

::Probably Susan left.

::Susan probably left.

::Certainly that happened more than once.

::That certainly happened more than once.

Since the finite verb is viewed as the head of the clause in each case, these data allow an analysis in terms of shifting. The subject and modal adverb have swapped positions. In other languages that have many head-final

In linguistics, head directionality is a proposed Principles and parameters, parameter that classifies languages according to whether they are head-initial (the head (linguistics), head of a phrase precedes its Complement (linguistics), complement ...

structures, shifting in the pre-head domain is a common occurrence.

Theoretical analyses

If one assumes relatively flat structures, the analysis of many canonical instances of shifting is straightforward. Shifting occurs among two or more sister constituents that appear on the same side of their head. The following trees illustrate the basic shifting constellation in a ''phrase structure grammar

The term phrase structure grammar was originally introduced by Noam Chomsky as the term for grammar studied previously by Emil Post and Axel Thue ( Post canonical systems). Some authors, however, reserve the term for more restricted grammars in t ...

'' (= constituency grammar) first and in a dependency grammar

Dependency grammar (DG) is a class of modern Grammar, grammatical theories that are all based on the dependency relation (as opposed to the ''constituency relation'' of Phrase structure grammar, phrase structure) and that can be traced back prima ...

second:

:: The two constituency-based trees show a flat VP that allows n-ary branching (as opposed to just binary branching). The two dependency-based trees show the same VP. Regardless of whether one chooses the constituency- or the dependency-based analysis, the important thing about these examples is the relative flatness of the structure. This flatness results in a situation where shifting does not necessitate a discontinuity (i.e. no long distance dependency), for there can be no crossing lines in the trees. The following trees further illustrate the point:

::

The two constituency-based trees show a flat VP that allows n-ary branching (as opposed to just binary branching). The two dependency-based trees show the same VP. Regardless of whether one chooses the constituency- or the dependency-based analysis, the important thing about these examples is the relative flatness of the structure. This flatness results in a situation where shifting does not necessitate a discontinuity (i.e. no long distance dependency), for there can be no crossing lines in the trees. The following trees further illustrate the point:

:: Again due to the flatness of structure, shifting does not result in a discontinuity. In this example, both orders are acceptable because there is little difference in the relative weight between the two constituents that switch positions.

An alternative analysis of shifting is necessary in a constituency grammar that posits strictly binary branching structures. The more layered binary branching structures would result in crossing lines in the tree, which means movement (or copying) is necessary to avoid these crossing lines. The following trees are (merely) representative of the type of analysis that one might assume given strictly binary branching structures:

::

Again due to the flatness of structure, shifting does not result in a discontinuity. In this example, both orders are acceptable because there is little difference in the relative weight between the two constituents that switch positions.

An alternative analysis of shifting is necessary in a constituency grammar that posits strictly binary branching structures. The more layered binary branching structures would result in crossing lines in the tree, which means movement (or copying) is necessary to avoid these crossing lines. The following trees are (merely) representative of the type of analysis that one might assume given strictly binary branching structures:

:: The analysis shown with the trees assumes binary branching and leftward movement only. Given these restrictions, two instances of movement might be necessary to accommodate the surface order seen in tree b. The material in light gray represents copies that must be deleted in the phonological component.

This sort of analysis of shifting has been criticized by

The analysis shown with the trees assumes binary branching and leftward movement only. Given these restrictions, two instances of movement might be necessary to accommodate the surface order seen in tree b. The material in light gray represents copies that must be deleted in the phonological component.

This sort of analysis of shifting has been criticized by Ray Jackendoff

Ray Jackendoff (born January 23, 1945) is an American linguist. He is professor of philosophy, Seth Merrin Chair in the Humanities and, with Daniel Dennett, co-director of the Center for Cognitive Studies at Tufts University. He has always str ...

, among others.See Jackendoff (1990) and Culicover and Jackendoff (2005) in this regard. Jackendoff and Culicover argue for an analysis like that shown with the flatter trees above, whereby heavy NP shift does not result from movement, but rather from a degree of optionality in the ordering of a verb's complements. The preferred order in English is for the direct object to follow the indirect object in a double-object construction, and for adjuncts to follow objects of all kinds; but if the direct object is "heavy", the opposite order may be preferred (since this leads to a more right-branching tree structure which is easier to process).

A mystery

From a generativist's perspective, a ''mysterious'' property of shifting is that in the case of ditransitive verbs, a shifted direct object prevents extraction of the indirect object viawh-movement

In linguistics, wh-movement (also known as wh-fronting, wh-extraction, or wh-raising) is the formation of syntactic dependencies involving interrogative words. An example in English is the dependency formed between ''what'' and the object position ...

:

:: Who did you give the books written by the venerable Professor Plum to?

:: *Who did you give to the books written by the venerable Professor Plum?

Some generativists use this example to argue against the hypothesis that shifting merely results from choice between alternative complement orders, a hypothesis that does not imply movement. Their analysis in terms of a strictly binary branching tree resulting from leftward movements would in turn be able to explain this restriction. However, there are at least two ways of countering this argument: 1) in case one wants to explain choice, if choice is assumed to be performed between possible orders, the impossible order is not in the linguistic potential and it cannot be chosen; however, 2) in case one wants to explain generation, that is, to explain how a linguistic potential comes to exist in a situation, one can explain this phenomenon in terms of generation and avoidance rules: for instance, one of the reasons for avoiding a wording in potentiality would be an ordering in which a preposition falls before a nominal group by accident as in the example above. In other words, from a functional perspective, we either recognise that these fake clauses are none of the clauses we can choose from (choice of possible clauses) or we say that they are generated and avoided because they might cause listeners to misunderstand what the speaker is saying (generation and avoidance).

Notes

References

*Ross, J. 1967. Constraints on variables in syntax. Ph.D. Dissertation, MIT. *Larson, R. 1988. On the double object construction. Linguistic Inquiry 19, 335–392. *Groß, T. and T. Osborne 2009. Toward a practical dependency grammar theory of discontinuities. SKY Journal of Linguistics 22, 43–90. *Jackendoff, R. 1990. On Larson's treatment of the double object construction. Linguistic Inquiry 21, 427–456. *Kayne, R. 1981. Unambiguous paths. In R. May and J. Koster (eds.), Levels of syntactic representation, 143–183. Dordrecht: Kluwer. *Kayne, R. 1994. The antisymmetry of syntax. Linguistic Inquiry Monograph Twenty-Five. MIT Press. *Cullicover, P. and R. Jackendoff 2005. Simpler Syntax. MIT Press. *Osborne, T. 2019A Dependency Grammar of English: An Introduction and Beyond

Amsterdam: John Benjamins. https://doi.org/10.1075/z.224 {{Syntax Word order Syntax