Sergey Degayev on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

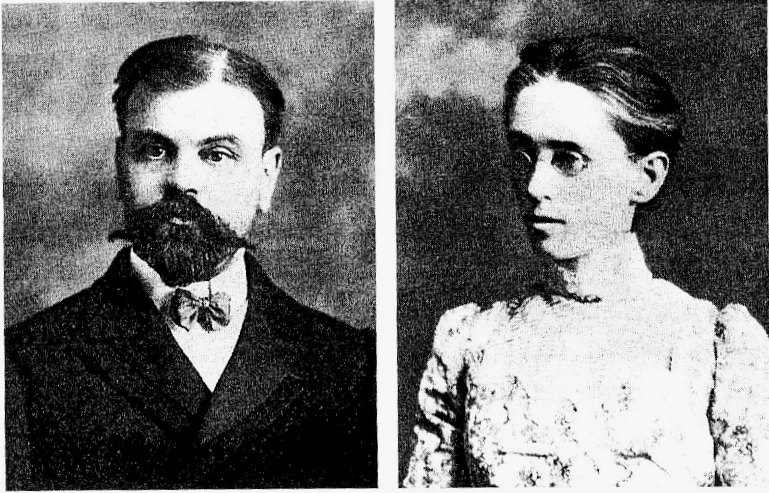

Sergey Petrovich Degayev (also spelled Degaev; ; 1857 in Moscow – 1921 in

Sergey Petrovich Degayev (also spelled Degaev; ; 1857 in Moscow – 1921 in

At the age of nine, Sergey entered a Moscow Cadet school. After graduation, Sergey entered the Mikhailovskaya Artillery Academy in

At the age of nine, Sergey entered a Moscow Cadet school. After graduation, Sergey entered the Mikhailovskaya Artillery Academy in

At that time,

At that time,  Sudeykin was an avid supporter of using

Sudeykin was an avid supporter of using

Some immigrant members of Narodnaya Volya harbored suspicions about Degayev, which were confirmed after Degayev talked with another prominent Narodnaya Volya member,

Some immigrant members of Narodnaya Volya harbored suspicions about Degayev, which were confirmed after Degayev talked with another prominent Narodnaya Volya member,  The conspirators planned to get Sudeykin to visit Degayev's apartment and to kill him there. Degayev insisted that because of Sudeykin's great physical strength and his great ability with guns, their only chance was to shoot Sudeykin unexpectedly. For some reason Sudeykin twice missed his appointed meetings (6 December 1883 and 13 December 1883). To lure Sudeykin to the next meeting Degayev told him a story that he had a woman from Narodnaya Volya staying in his apartment who had planned to assassinate the tsar but who could possibly be persuaded to become an Okhrana agent. Sudeykin came on 16 December accompanied by his nephew, another secret police officer, Nikolay (Koka) Sudovsky. Degayev invited Sudeykin to the bedroom to be introduced to the woman and in the passageway between the dining room and the bedroom, near the watercloset, shot him in the back. Mortally wounded, Sudeykin cried to his nephew: "Koka, take your gun and help me!" But Koka ran out of the apartment. While he was struggling with the locks trying to open the door Konashevich came from behind and with several blows of a crowbar cracked Sudovsky's skull. Unexpectedly Sudeykin was able to stand up and walk to the dining room. There he was shot by Starodvorsky. Degayev (and later Konashevich) ran away from the apartment without waiting for the end of the ordeal. Degayev was sure that his accomplices had been ordered to kill him after Sudeykin was killed. The gunshots and cries were heard all across the building; however, when the concierge reported to the local police they told him that they had instructions not to interfere with the apartment whatever happened there. The apartment was searched only the next day after Sudeykin's servant reported that his master had not returned at the expected hour. Rushing to the apartment police found the dying Koka and dead Sudeykin.

All the posts in the Empire were plastered with posters showing Degayev's photographs and announcing 5000 roubles for information as to his whereabouts and 10,000 roubles for help in catching him. Still the conspirators had a good lead on their hunters and successfully arrived in Paris. At a winter 1884 meeting, Narodnaya Volya, led by V. A. Karaulov, Lev Tikhomirov and German Lopatin, fulfilled its end of the bargain and granted Degayev his life on the condition that he never again appear in the

The conspirators planned to get Sudeykin to visit Degayev's apartment and to kill him there. Degayev insisted that because of Sudeykin's great physical strength and his great ability with guns, their only chance was to shoot Sudeykin unexpectedly. For some reason Sudeykin twice missed his appointed meetings (6 December 1883 and 13 December 1883). To lure Sudeykin to the next meeting Degayev told him a story that he had a woman from Narodnaya Volya staying in his apartment who had planned to assassinate the tsar but who could possibly be persuaded to become an Okhrana agent. Sudeykin came on 16 December accompanied by his nephew, another secret police officer, Nikolay (Koka) Sudovsky. Degayev invited Sudeykin to the bedroom to be introduced to the woman and in the passageway between the dining room and the bedroom, near the watercloset, shot him in the back. Mortally wounded, Sudeykin cried to his nephew: "Koka, take your gun and help me!" But Koka ran out of the apartment. While he was struggling with the locks trying to open the door Konashevich came from behind and with several blows of a crowbar cracked Sudovsky's skull. Unexpectedly Sudeykin was able to stand up and walk to the dining room. There he was shot by Starodvorsky. Degayev (and later Konashevich) ran away from the apartment without waiting for the end of the ordeal. Degayev was sure that his accomplices had been ordered to kill him after Sudeykin was killed. The gunshots and cries were heard all across the building; however, when the concierge reported to the local police they told him that they had instructions not to interfere with the apartment whatever happened there. The apartment was searched only the next day after Sudeykin's servant reported that his master had not returned at the expected hour. Rushing to the apartment police found the dying Koka and dead Sudeykin.

All the posts in the Empire were plastered with posters showing Degayev's photographs and announcing 5000 roubles for information as to his whereabouts and 10,000 roubles for help in catching him. Still the conspirators had a good lead on their hunters and successfully arrived in Paris. At a winter 1884 meeting, Narodnaya Volya, led by V. A. Karaulov, Lev Tikhomirov and German Lopatin, fulfilled its end of the bargain and granted Degayev his life on the condition that he never again appear in the

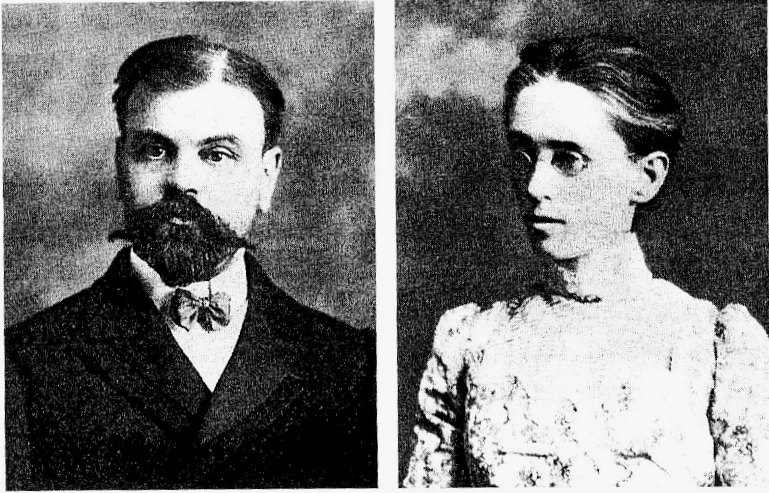

Alexander Pell was immensely popular among his students who referred to him as the "class father" and "Jolly Little Pell" (who could "crack jokes faster than the freshmen could crack nuts"). He was a good researcher, a member of the

Alexander Pell was immensely popular among his students who referred to him as the "class father" and "Jolly Little Pell" (who could "crack jokes faster than the freshmen could crack nuts"). He was a good researcher, a member of the

/ref>

Sergey Petrovich Degayev (also spelled Degaev; ; 1857 in Moscow – 1921 in

Sergey Petrovich Degayev (also spelled Degaev; ; 1857 in Moscow – 1921 in Bryn Mawr, Pennsylvania

Bryn Mawr (, from Welsh language, Welsh for 'big hill') is a census-designated place (CDP) located in Pennsylvania, United States. It is located just west of Philadelphia along Lancaster Avenue, also known as U.S. Route 30 in Pennsylvania, U.S. ...

) was a Russian revolutionary terrorist, Okhrana

The Department for the Protection of Public Safety and Order (), usually called the Guard Department () and commonly abbreviated in modern English sources as the Okhrana ( rus , Охрана, p=ɐˈxranə, a=Ru-охрана.ogg, t= The Guard) w ...

agent, and the murderer of inspector of secret police Georgy Sudeykin

Georgy Porfiryevich Sudeykin (; 11 April 1850 – 16 December 1883 Saint Petersburg) was a Russian Gendarme colonel, the inspector of the ''Saint Petersburg Department for Protection of Communal Security and Order''. He was killed by his own dou ...

. After emigrating to the United States, Degayev took the name Alexander Pell and became a prominent American mathematician, the founder of school of Engineering at the University of South Dakota

The University of South Dakota (USD) is a public research university in Vermillion, South Dakota, United States. Established by the Dakota Territory legislature in 1862, 27 years before the establishment of the state of South Dakota, USD is t ...

. The Dr. Alexander Pell scholarship is named in his honor.

Russian revolutionary and Okhrana agent

Family

Sergey Degayev was born in Moscow to the family of a military physician, state counsellor Peter Degayev. p.5 His maternal grandfather was a prominent Russian writer,Nikolai Polevoy

Nikolai Alekseevich Polevoy (, ― ) was a controversial Russian editor, writer, translator, and historian; his brother was the critic and journalist Ksenofont Polevoy and his sister the writer and publisher of folktales Ekaterina Avdeeva.

Bi ...

. His father died in the 1860s, and Degayev's mother became the head of the family; she was, for her time, a well-educated woman, whose interests included reading and learning foreign languages. When the court sentenced pregnant revolutionary Hesya Helfman

Hesya Mirovna (Meerovna) Helfman (; ; 1855 — ) was a Belarusian-Jewish revolutionary member of ''Narodnaya Volya'', who was implicated in the assassination of Alexander II of Russia. Escaping execution as she was pregnant at the time, she died ...

to death, she tried, unsuccessfully, to adopt the baby, despite a possible conflict with the authorities. p.9

Degayev had three sisters—Marie, Nathalie, and Elizabeth—and a brother Vladimir, who was seven years his junior. While Marie was much older than Sergey, married early and did not play a large role in the life of the family, Nathalie (after marriage Makletsova) and Elizabeth (Liz) were very close to him. Natalie was a musician, while Elizabeth was a poet. Both sisters were involved in the Narodnaya Volya

Narodnaya Volya () was a late 19th-century revolutionary socialist political organization operating in the Russian Empire, which conducted assassinations of government officials in an attempt to overthrow the autocratic Tsarist system. The org ...

revolutionary movement. Vladimir was also deeply involved with Narodnaya Volya. As the oldest son, Sergey had to provide financial support for the family.

Military officer, student and engineer

At the age of nine, Sergey entered a Moscow Cadet school. After graduation, Sergey entered the Mikhailovskaya Artillery Academy in

At the age of nine, Sergey entered a Moscow Cadet school. After graduation, Sergey entered the Mikhailovskaya Artillery Academy in Saint Petersburg

Saint Petersburg, formerly known as Petrograd and later Leningrad, is the List of cities and towns in Russia by population, second-largest city in Russia after Moscow. It is situated on the Neva, River Neva, at the head of the Gulf of Finland ...

. He was accused of organizing anti-government underground "circles" in Saint Petersburg and Kronstadt

Kronstadt (, ) is a Russian administrative divisions of Saint Petersburg, port city in Kronshtadtsky District of the federal cities of Russia, federal city of Saint Petersburg, located on Kotlin Island, west of Saint Petersburg, near the head ...

. The accusations were never proven, but in 1879, Degayev was nevertheless expelled from the Academia. He briefly served as a military officer and was discharged from the Army with the rank of Staff captain

Staff captain is the English translation of a number of military ranks:

Historical use of the rank Czechoslovakia

In the Czechoslovak Army, until 1953, staff captain (, ) was a senior captain rank, ranking between captain and major.

Estonia

T ...

in the same year. p.10

Degayev was enrolled to the Saint Petersburg Institute for Rail Road Engineering in 1880. During his studies, he became acquainted with Andrei Zhelyabov

Andrei Ivanovich Zhelyabov (; – ) was a Russian revolutionary and member of the executive committee of Narodnaya Volya (organization), Narodnaya Volya.

Zhelyabov was born in to a family of Serfdom in Russia, serfs. After graduating from a g ...

and members of his circle; and in 1880, he became a full-fledged member of Narodnaya Volya, a revolutionary organization that turned to terrorist methods. After the 1879 Lipetsk Congress

Lipetsk (, ), also romanized as Lipeck, is a city and the administrative center of Lipetsk Oblast, Russia, located on the banks of the Voronezh River in the Don basin, southeast of Moscow. Population:

History

The name means " Linden cit ...

of Narodnaya Volya, which "sentenced" tsar Alexander II to death, most of the organization's resources were directed to the tsar's assassination. Degayev took an active part in an unsuccessful assassination attempt by digging and mining a tunnel under Malaya Sadovaya Street

Malaya Sadovaya Street (, meaning 'Little Garden Street') is a pedestrian street of cafes, terraces and fountains in the heart of Saint Petersburg, Russia. It runs between Italyanskaya Street (Italian Street) and the Nevsky Prospect. Spanning a ...

in Saint Petersburg. Some sources also suggest that Degayev had a role in the successful assassination of the tsar on 1 March 1881 and even observed the explosion that killed him. pp. 12–30 Degayev was among those arrested in connection with the assassination, but his guilt was not proven; he returned to his institute and received his degree in June 1881.

After graduating Degayev obtained an engineering position in Arkhangelsk

Arkhangelsk (, ) is a types of inhabited localities in Russia, city and the administrative center of Arkhangelsk Oblast, Russia. It lies on both banks of the Northern Dvina near its mouth into the White Sea. The city spreads for over along the ...

. There he met Lyubov Ivanova, a young woman who shared his political views; he fell in love and married her on their trip to Saint Petersburg in November 1881.

Georgy Sudeykin and Vladimir Degayev

At that time,

At that time, Gendarme

A gendarmerie () is a paramilitary or military force with law enforcement duties among the civilian population. The term ''gendarme'' () is derived from the medieval French expression ', which translates to "men-at-arms" (). In France and som ...

Lieutenant Colonel Georgy Sudeykin

Georgy Porfiryevich Sudeykin (; 11 April 1850 – 16 December 1883 Saint Petersburg) was a Russian Gendarme colonel, the inspector of the ''Saint Petersburg Department for Protection of Communal Security and Order''. He was killed by his own dou ...

was among the most dangerous enemies of Narodnaya Volya. He had eliminated the Kiev

Kyiv, also Kiev, is the capital and most populous List of cities in Ukraine, city of Ukraine. Located in the north-central part of the country, it straddles both sides of the Dnieper, Dnieper River. As of 1 January 2022, its population was 2, ...

division of Narodnaya Volya almost entirely and was appointed the Head of the Secret Department of police of Saint Petersburg, responsible for coordination of all the secret agents in the capital of the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire that spanned most of northern Eurasia from its establishment in November 1721 until the proclamation of the Russian Republic in September 1917. At its height in the late 19th century, it covered about , roughl ...

. Later he would be appointed a special position of the ''Inspector of the Secret Police'', a post specially created for him. As the primary hunter of Narodnaya Volya, he was also a main target of their assassination attempts. Sudeykin rarely lived in the same place for more than a few weeks; he used several passports and several uniforms of different governmental departments. He even temporarily lodged his wife and children in a Saint Petersburg prison, given that he felt it was the only safe place in the whole Empire. pp. 33–39

Sudeykin was an avid supporter of using

Sudeykin was an avid supporter of using agent provocateur

An is a person who actively entices another person to commit a crime that would not otherwise have been committed and then reports the person to the authorities. They may target individuals or groups.

In jurisdictions in which conspiracy is a ...

s inside the revolutionary movements not only to catch the active members but also to instigate quarrels and disputes, spread false rumours, and transmit the opinion that all the leading revolutionaries were spies or provocateurs. He was proud of his successes in recruiting his agents among the revolutionaries claiming that every member of an anti-government movement is either corrupt or naive: the corrupt can always be recruited by promise of money or by threats while the naive can always be recruited by appeal to their idealism.

Around November 1881 Vladimir, the younger brother of Degayev, was arrested for his participation in the Narodnaya Volya movement. He was interrogated by Sudeykin, who offered Vladimir freedom in exchange for collaboration with the Okhrana

The Department for the Protection of Public Safety and Order (), usually called the Guard Department () and commonly abbreviated in modern English sources as the Okhrana ( rus , Охрана, p=ɐˈxranə, a=Ru-охрана.ogg, t= The Guard) w ...

. Vladimir managed to inform the Executive Committee of Narodnaya Volya about the offer. Degayev participated in the discussions and proposed a plan: that Vladimir should accept Sudeikin's offer, and after becoming a police informer should arrange a secret meeting with Sudeykin at which Narodnaya Volya would kill Sudeykin. In March 1882 the plan was adopted by the Executive Commission of Narodnaya Volya. Vladimir agreed to work as an Okhrana agent, was released from prison and arranged a few meetings between Sudeykin and Sergey Degaev, who was charged with preparing for the assassination. However, soon most of Petersburg's Narodnaya Volya members were arrested. Sergey Degayev moved to Tiflis

Tbilisi ( ; ka, თბილისი, ), in some languages still known by its pre-1936 name Tiflis ( ), ( ka, ტფილისი, tr ) is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Georgia (country), largest city of Georgia ( ...

to avoid the arrests and work on the Tiflis-Baku

Baku (, ; ) is the Capital city, capital and List of cities in Azerbaijan, largest city of Azerbaijan, as well as the largest city on the Caspian Sea and in the Caucasus region. Baku is below sea level, which makes it the List of capital ci ...

railway. Vladimir Degayev abandoned the plan of killing Sudeykin and was soon removed from the list of Okhrana agents "for inactivity."

Leader of Narodnaya Volya and Okhrana Agent

In summer 1882, Degayev worked inTiflis

Tbilisi ( ; ka, თბილისი, ), in some languages still known by its pre-1936 name Tiflis ( ), ( ka, ტფილისი, tr ) is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Georgia (country), largest city of Georgia ( ...

as a railroad engineer and organized Narodnaya Volya circles among Tiflis military officers. He presented himself as a member of the Executive Committee of Narodnaya Volya although he was not a member at that time. In autumn 1882, most of the Narodnaya Volya members in Tiflis were arrested and Degayev was ordered by the Narodnaya Volya leader Vera Figner

Vera Nikolayevna Figner Filippova (; – 25 June 1942) was a Russian revolutionary and political activist.

Born in Kazan Governorate of the Russian Empire into a noble family of Germans, German and Russians, Russian descent, Figner was a leader ...

to move to Odessa

ODESSA is an American codename (from the German language, German: ''Organisation der ehemaligen SS-Angehörigen'', meaning: Organization of Former SS Members) coined in 1946 to cover Ratlines (World War II aftermath), Nazi underground escape-pl ...

and organize an underground press there. On 18 December 1883 Degayev and the whole of his group was arrested.

After interrogation by Georgy Sudeykin, Degayev agreed to become an Okhrana informant. Almost all information about the deal came from Degayev himself, in an explanation he gave to his sister Natalia and to a Narodnaya Volya "court." According to Degayev, Sudeykin had appealed to his vanity and idealism. Sudeykin promised that in a few years they both would be de facto rulers of the Russian Empire by using the Okhrana to remove Degayev's superiors in Narodnaya Volya and by using Narodnaya Volya to remove Sudeykin's superiors in the Okhrana. He also promised Degayev secret meetings with tsar Alexander III, the police chief Vyacheslav von Plehve

Vyacheslav Konstantinovich von Plehve ( rus, Вячесла́в Константи́нович фон Пле́ве, p=vʲɪtɕɪˈslaf kənstɐnʲˈtʲinəvʲɪtɕ fɐn ˈplʲevʲɪ; – ) was a Russian politician who served as the directo ...

and the influential Ober-Procurator

The Procurator (, tr. ''prokuror'') was an office initially established in 1722 by Peter the Great, the first Emperor of the Russian Empire, as part of the ecclesiastical reforms to bring the Russian Orthodox Church more directly under his contr ...

of the Holy Synod

In several of the autocephalous Eastern Orthodox Churches and Eastern Catholic Churches, the patriarch or head bishop is elected by a group of bishops called the Holy Synod. For instance, the Holy Synod is a ruling body of the Georgian Orthodox ...

Konstantin Pobedonostsev

Konstantin Petrovich Pobedonostsev ( rus, Константи́н Петро́вич Победоно́сцев, p=kənstɐnʲˈtʲin pʲɪˈtrovʲɪtɕ pəbʲɪdɐˈnostsɨf; 30 November 1827 – 23 March 1907) was a Russian jurist and states ...

so that Degayev could present to them his plan of state reforms. According to Degayev, he indeed met Plehve and Pobedonostsev but not the tsar. However, research in the Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

suggested that Degayev started to work as an Okhrana informant a few years earlier purely for financial reasons. Researcher Yu.F. Ovchenko states that Degayev started to work as an Okhrana informant in 1882 after his wife was arrested by Sudeykin. His cooperation with the Okhrana was a condition of Lyubov's release At any rate the agreement with Sudeykin provided a handsome monetary compensation for Degayev: 300 Russian rouble

The ruble or rouble (; Currency symbol, symbol: ₽; ISO 4217, ISO code: RUB) is the currency of the Russia, Russian Federation. Banknotes and coins are issued by the Central Bank of Russia, which is Russia's central bank, monetary authority ind ...

s monthly plus 1000 roubles for each trip abroad. p.84

Sudeykin staged Degayev's escape from prison. Information obtained from Degayev allowed the Okhrana to arrest the leader of Narodnaya Volya Vera Figner

Vera Nikolayevna Figner Filippova (; – 25 June 1942) was a Russian revolutionary and political activist.

Born in Kazan Governorate of the Russian Empire into a noble family of Germans, German and Russians, Russian descent, Figner was a leader ...

, to almost completely destroy the military wing of the organization, to arrest almost all members in the Tiflis, Nikolaev, and Kharkov organizations. After those arrests Degayev became a de facto leader of Narodnaya Volya. p.78 Information obtained from Degayev and from subsequent arrests allowed police to assure the tsar that his coronation

A coronation ceremony marks the formal investiture of a monarch with regal power using a crown. In addition to the crowning, this ceremony may include the presentation of other items of regalia, and other rituals such as the taking of special v ...

ceremony would be safe. Alexander III was crowned on 27 May 1883. pp. 87–91

Inspired by Alexandre Dumas

Alexandre Dumas (born Alexandre Dumas Davy de la Pailleterie, 24 July 1802 – 5 December 1870), also known as Alexandre Dumas , was a French novelist and playwright.

His works have been translated into many languages and he is one of the mos ...

's novel '' The Vicomte of Bragelonne: Ten Years Later'', Sudeykin sent Degayev to Switzerland

Switzerland, officially the Swiss Confederation, is a landlocked country located in west-central Europe. It is bordered by Italy to the south, France to the west, Germany to the north, and Austria and Liechtenstein to the east. Switzerland ...

to lure two remaining Narodnaya Volya leaders, Lev Tikhomirov

Lev Alexandrovich Tikhomirov (; 19 January 1852, Gelendzhik – 10 October 1923, Sergiyev Posad), originally a Russian revolutionary and one of the members of the Executive Committee of the Narodnaya Volya, following his disenchantment with violen ...

and Peter Lavrov, to Russia to be arrested. Tikhomirov and Lavrov suspected foul play and refused to move but kept their suspicions to themselves for a while. p.81 Trying to deflect suspicions from Degayev, Sudeykin decided to sacrifice police informer Fyodor Shkryaba, a member of Narodnaya Volya recruited by the Okhrana who still provided information of low interest to the Okhrana. Sudeykin planted evidence of Shkryaba being an informant and Narodnaya Volya blamed all the recent arrests on Shkryaba. Subsequently Degayev organized the assassination of Shkryaba.

In June 1883 Narodnaya Volya resumed publication of ''Listok Narodnoy Voly'', an underground newspaper, as a demonstration that the organization was alive. Degayev published an article praising pogrom

A pogrom is a violent riot incited with the aim of Massacre, massacring or expelling an ethnic or religious group, particularly Jews. The term entered the English language from Russian to describe late 19th- and early 20th-century Anti-Jewis ...

s against Jews and urging members to incite more pogroms. At the time, Narodnaya Volya had an ambivalent position on antisemitism

Antisemitism or Jew-hatred is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who harbours it is called an antisemite. Whether antisemitism is considered a form of racism depends on the school of thought. Antisemi ...

. Some theoreticians applied Marxist

Marxism is a political philosophy and method of socioeconomic analysis. It uses a dialectical and materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to analyse class relations, social conflic ...

analysis and saw pogroms as a manifestation of the class struggle

In political science, the term class conflict, class struggle, or class war refers to the economic antagonism and political tension that exist among social classes because of clashing interests, competition for limited resources, and inequali ...

between oppressed peasants and oppressive Jewish petite bourgeoisie

''Petite bourgeoisie'' (, ; also anglicised as petty bourgeoisie) is a term that refers to a social class composed of small business owners, shopkeepers, small-scale merchants, semi- autonomous peasants, and artisans. They are named as s ...

. On the other hand, many Narodnaya Volya members saw pogroms as incited by the tsarist Government and as one of the most revolting of the regime's crimes. The question of antisemitism was rendered even more divisive by the fact that many members were ethnic Jews. Richard Pipes

Richard Edgar Pipes (; July 11, 1923 – May 17, 2018) was an American historian who specialized in Russian and Soviet history. Pipes was a frequent interviewee in the press on the matters of Soviet history and foreign affairs. His writings als ...

speculated that the article was a part of Sudeykin's plan to transform Narodnaya Volya from an anti-government to an ultra-nationalist organisation similar to the later Black Hundreds

The Black Hundreds were reactionary, monarchist, and ultra-nationalist groups in Russia in the early 20th century. They were staunch supporters of the House of Romanov, and opposed any retreat from the autocracy of the reigning monarch. Their na ...

. pp. 85–86

Toward the middle of 1883, Sudeykin and Degayev established quite friendly relations. Sudeykin regularly visited the apartment of his agent and even used the apartment for his extramarital affairs. Sometimes they had wagers: once, Degayev announced that there was a person of interest to police in Saint Petersburg at the moment and claimed that Sudeykin would not be able to catch him without Degayev's help. Sudeykin answered that he had enough agents besides Degayev. The pair had a monetary bet that Sudeykin would not be able to effect an arrest: Sudeykin lost.

At that time Sudeykin was frustrated with his superiors. He did not like their attempts to put legal constraints on the actions of his secret police. He also considered his rank of Lieutenant Colonel (the seventh in the Table of Ranks

The Table of Ranks () was a formal list of positions and ranks in the military, government, and court of Imperial Russia. Peter I of Russia, Peter the Great introduced the system in 1722 while engaged in a struggle with the existing hereditary ...

) to be absurdly low for a person of his importance within the state security apparatus. Sudeykin proposed to Degayev a plan . Sudeykin would resign from his position, stating that he did not have enough powers to do his job properly. Soon Narodnaya Volya would assassinate the tsar's brother Grand Duke Vladimir and the tsar's aide Konstantin Pobedonostsev

Konstantin Petrovich Pobedonostsev ( rus, Константи́н Петро́вич Победоно́сцев, p=kənstɐnʲˈtʲin pʲɪˈtrovʲɪtɕ pəbʲɪdɐˈnostsɨf; 30 November 1827 – 23 March 1907) was a Russian jurist and states ...

. The double assassination would frighten the tsar into accepting all Sudeykin's demands over the powers of secret police and might, too, make the tsar more responsive to Degayev's suggestions about government reforms. Sudeykin also gave Degayev information about the movements of Sudeykin's own boss, the Minister of Interior Dmitry Tolstoy

Count Dmitry Andreyevich Tolstoy (; , Moscow – , Saint Petersburg) was a Russian politician and a member of the State Council of Imperial Russia (1866). He belonged to the comital branch of the Tolstoy family.

Career

Tolstoy graduated f ...

considering that the killing might free a deserved position for Sudeykin. Unexpectedly the tsar refused Sudeykin's letter of resignation, causing the pair to postpone assassination plans to 1884.

Assassination of Georgy Sudeykin

Some immigrant members of Narodnaya Volya harbored suspicions about Degayev, which were confirmed after Degayev talked with another prominent Narodnaya Volya member,

Some immigrant members of Narodnaya Volya harbored suspicions about Degayev, which were confirmed after Degayev talked with another prominent Narodnaya Volya member, German Lopatin

German Alexandrovich Lopatin (; 13 January 1845, in Nizhny Novgorod, Russia – 26 December 1918, in Petrograd) was a Russian revolutionary, journalist, writer and poet.

Biography

Lopatin came from an aristocratic family. He studied physics ...

, an experienced escapee from prisons himself. Lopatin found many inconsistencies in Degayev's story about his escape from Odessa prison. Interrogated by Lev Tikhomirov

Lev Alexandrovich Tikhomirov (; 19 January 1852, Gelendzhik – 10 October 1923, Sergiyev Posad), originally a Russian revolutionary and one of the members of the Executive Committee of the Narodnaya Volya, following his disenchantment with violen ...

, Degayev confessed that he was an Okhrana agent and offered to help kill Sudeykin. On 17 October – 19 October 1883, the Executive Committee of Narodnaya Volya, which at that time consisted of eight Russians and three Poles, decided to spare Degayev's life if he killed Sudeykin. They appointed two young Narodnaya Volya members, V. P. Konashevich and N. P. Starodvorsky to assist Degayev and to ensure that Degayev would not renege on his promise. pp. 92–108

The conspirators planned to get Sudeykin to visit Degayev's apartment and to kill him there. Degayev insisted that because of Sudeykin's great physical strength and his great ability with guns, their only chance was to shoot Sudeykin unexpectedly. For some reason Sudeykin twice missed his appointed meetings (6 December 1883 and 13 December 1883). To lure Sudeykin to the next meeting Degayev told him a story that he had a woman from Narodnaya Volya staying in his apartment who had planned to assassinate the tsar but who could possibly be persuaded to become an Okhrana agent. Sudeykin came on 16 December accompanied by his nephew, another secret police officer, Nikolay (Koka) Sudovsky. Degayev invited Sudeykin to the bedroom to be introduced to the woman and in the passageway between the dining room and the bedroom, near the watercloset, shot him in the back. Mortally wounded, Sudeykin cried to his nephew: "Koka, take your gun and help me!" But Koka ran out of the apartment. While he was struggling with the locks trying to open the door Konashevich came from behind and with several blows of a crowbar cracked Sudovsky's skull. Unexpectedly Sudeykin was able to stand up and walk to the dining room. There he was shot by Starodvorsky. Degayev (and later Konashevich) ran away from the apartment without waiting for the end of the ordeal. Degayev was sure that his accomplices had been ordered to kill him after Sudeykin was killed. The gunshots and cries were heard all across the building; however, when the concierge reported to the local police they told him that they had instructions not to interfere with the apartment whatever happened there. The apartment was searched only the next day after Sudeykin's servant reported that his master had not returned at the expected hour. Rushing to the apartment police found the dying Koka and dead Sudeykin.

All the posts in the Empire were plastered with posters showing Degayev's photographs and announcing 5000 roubles for information as to his whereabouts and 10,000 roubles for help in catching him. Still the conspirators had a good lead on their hunters and successfully arrived in Paris. At a winter 1884 meeting, Narodnaya Volya, led by V. A. Karaulov, Lev Tikhomirov and German Lopatin, fulfilled its end of the bargain and granted Degayev his life on the condition that he never again appear in the

The conspirators planned to get Sudeykin to visit Degayev's apartment and to kill him there. Degayev insisted that because of Sudeykin's great physical strength and his great ability with guns, their only chance was to shoot Sudeykin unexpectedly. For some reason Sudeykin twice missed his appointed meetings (6 December 1883 and 13 December 1883). To lure Sudeykin to the next meeting Degayev told him a story that he had a woman from Narodnaya Volya staying in his apartment who had planned to assassinate the tsar but who could possibly be persuaded to become an Okhrana agent. Sudeykin came on 16 December accompanied by his nephew, another secret police officer, Nikolay (Koka) Sudovsky. Degayev invited Sudeykin to the bedroom to be introduced to the woman and in the passageway between the dining room and the bedroom, near the watercloset, shot him in the back. Mortally wounded, Sudeykin cried to his nephew: "Koka, take your gun and help me!" But Koka ran out of the apartment. While he was struggling with the locks trying to open the door Konashevich came from behind and with several blows of a crowbar cracked Sudovsky's skull. Unexpectedly Sudeykin was able to stand up and walk to the dining room. There he was shot by Starodvorsky. Degayev (and later Konashevich) ran away from the apartment without waiting for the end of the ordeal. Degayev was sure that his accomplices had been ordered to kill him after Sudeykin was killed. The gunshots and cries were heard all across the building; however, when the concierge reported to the local police they told him that they had instructions not to interfere with the apartment whatever happened there. The apartment was searched only the next day after Sudeykin's servant reported that his master had not returned at the expected hour. Rushing to the apartment police found the dying Koka and dead Sudeykin.

All the posts in the Empire were plastered with posters showing Degayev's photographs and announcing 5000 roubles for information as to his whereabouts and 10,000 roubles for help in catching him. Still the conspirators had a good lead on their hunters and successfully arrived in Paris. At a winter 1884 meeting, Narodnaya Volya, led by V. A. Karaulov, Lev Tikhomirov and German Lopatin, fulfilled its end of the bargain and granted Degayev his life on the condition that he never again appear in the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire that spanned most of northern Eurasia from its establishment in November 1721 until the proclamation of the Russian Republic in September 1917. At its height in the late 19th century, it covered about , roughl ...

. Lev Tikhomirov personally verified that he boarded a steamship bound for South America.

American mathematician

From South America Degayev moved to the United States; there he joined his wife, Lyubov Degayeva. His brother, Vladimir Degayev, who worked at the time in a Russian consulate in the United States and moonlighted as a foreign correspondent for a few Russian publications printed an article claiming that Sergey Degayev was killed inNew Zealand

New Zealand () is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and List of islands of New Zealand, over 600 smaller islands. It is the List of isla ...

, discouraging searches for him by both Russian police and Russian revolutionaries.

Both Vladimir and Sergey Degayevs were registered in the USA under the name Polevoi after their maternal grandfather Nikolai Polevoy

Nikolai Alekseevich Polevoy (, ― ) was a controversial Russian editor, writer, translator, and historian; his brother was the critic and journalist Ksenofont Polevoy and his sister the writer and publisher of folktales Ekaterina Avdeeva.

Bi ...

. pp. 2–4 After his naturalization

Naturalization (or naturalisation) is the legal act or process by which a non-national of a country acquires the nationality of that country after birth. The definition of naturalization by the International Organization for Migration of the ...

Alexander (Sergey) took the name Alexander Pell and his wife took the name Emma Pell. At first they were poor; Sergey worked as a stevedore

A dockworker (also called a longshoreman, stevedore, docker, wharfman, lumper or wharfie) is a waterfront manual laborer who loads and unloads ships.

As a result of the intermodal shipping container revolution, the required number of dockwork ...

and as an unskilled labourer while his wife worked as a cook and a laundress

A washerwoman or laundress is a woman who takes in laundry. Both terms are now old-fashioned; equivalent work nowadays is done by a laundry worker in large commercial premises, or a laundrette (laundromat) attendant, who helps with handling wa ...

. In 1895 Alexander was enrolled into a PhD program in Johns Hopkins University

The Johns Hopkins University (often abbreviated as Johns Hopkins, Hopkins, or JHU) is a private university, private research university in Baltimore, Maryland, United States. Founded in 1876 based on the European research institution model, J ...

with majors in mathematics and astronomy

Astronomy is a natural science that studies celestial objects and the phenomena that occur in the cosmos. It uses mathematics, physics, and chemistry in order to explain their origin and their overall evolution. Objects of interest includ ...

and a minor in English. During his study he was financially supported by his wife who continued to work as a cook. He received his doctorate in 1897 for the dissertation ''On the Focal surface

For a surface in three dimension the focal surface, surface of centers or evolute is formed by taking the centers of the curvature spheres, which are the tangential spheres whose radii are the reciprocals of one of the principal curvatures at t ...

s of the Congruences of Tangents to a Given Surface''.

The University of South Dakota

The University of South Dakota (USD) is a public research university in Vermillion, South Dakota, United States. Established by the Dakota Territory legislature in 1862, 27 years before the establishment of the state of South Dakota, USD is t ...

was established in the frontier town of Vermillion

Vermilion (sometimes vermillion) is a color family and pigment most often used between antiquity and the 19th century from the powdered mineral cinnabar (a form of mercury sulfide). It is synonymous with red orange, which often takes a modern ...

and started its classes in 1882. In 1897 they decided that they needed a professor of mathematics. They asked Professor L. S. Hulburt from Johns Hopkins

Johns Hopkins (May 19, 1795 – December 24, 1873) was an American merchant, investor, and philanthropist. Born on a plantation, he left his home to start a career at the age of 17, and settled in Baltimore, Maryland, where he remained for mos ...

if he could suggest a suitable candidate. He replied that he "could suggest a first class mathematician who had the disadvantage of having a strong Russian brogue

Brogue may refer to:

Language

* Brogue (accent), regionally accented English, especially Irish-accented

* Mission brogue, an accent of English spoken in the Mission District of San Francisco

* Ocracoke brogue, a family of English dialects in the S ...

". The reply from South Dakota was "Send your Russian mathematician along, brogue and all".

Alexander Pell was immensely popular among his students who referred to him as the "class father" and "Jolly Little Pell" (who could "crack jokes faster than the freshmen could crack nuts"). He was a good researcher, a member of the

Alexander Pell was immensely popular among his students who referred to him as the "class father" and "Jolly Little Pell" (who could "crack jokes faster than the freshmen could crack nuts"). He was a good researcher, a member of the American Mathematical Society

The American Mathematical Society (AMS) is an association of professional mathematicians dedicated to the interests of mathematical research and scholarship, and serves the national and international community through its publications, meetings, ...

and the author of many journal publications. He was also an accomplished administrator who organized the School of Engineering of the University of South Dakota and became its first Dean (1905).

Alexander Pell had a habit of providing financial support from his own resources, and providing accommodation in his house to a few of his students. One such student was Anna Johnson, the future accomplished mathematician Anna Johnson Pell Wheeler

Anna Johnson Pell Wheeler (née Johnson; May 5, 1883 – March 26, 1966) was an American mathematician. She is best known for early work on linear algebra in infinite dimensions, which has later become a part of functional analysis.Louise S. Gri ...

. Anna Johnson received her A.B. degree under Pell's supervision in 1903 and continued her study at the University of Iowa

The University of Iowa (U of I, UIowa, or Iowa) is a public university, public research university in Iowa City, Iowa, United States. Founded in 1847, it is the oldest and largest university in the state. The University of Iowa is organized int ...

and then at the University of Göttingen

The University of Göttingen, officially the Georg August University of Göttingen (, commonly referred to as Georgia Augusta), is a Public university, public research university in the city of Göttingen, Lower Saxony, Germany. Founded in 1734 ...

. In 1904 Emma Pell died. Three years later Alexander Pell went to Göttingen

Göttingen (, ; ; ) is a college town, university city in Lower Saxony, central Germany, the Capital (political), capital of Göttingen (district), the eponymous district. The River Leine runs through it. According to the 2022 German census, t ...

and married Anna in July 1907. They both returned to Vermillion where Anna taught classes in the theory of function

Function or functionality may refer to:

Computing

* Function key, a type of key on computer keyboards

* Function model, a structured representation of processes in a system

* Function object or functor or functionoid, a concept of object-orie ...

s and differential equations and Alexander was the Dean of Engineering. In 1908 Pell resigned from the University of South Dakota and went with Anna to Chicago. There Anna completed her doctorate under E. H. Moore

Eliakim Hastings Moore (; January 26, 1862 – December 30, 1932), usually cited as E. H. Moore or E. Hastings Moore, was an American mathematician.

Life

Moore, the son of a Methodist minister and grandson of US Congressman Eliakim H. Moore, di ...

, while Pell took a position at the ''Armour Institute of Engineering'' (currently Illinois Institute of Technology

The Illinois Institute of Technology, commonly referred to as Illinois Tech and IIT, is a Private university, private research university in Chicago, Illinois, United States. Tracing its history to 1890, the present name was adopted upon the m ...

). In 1911 Pell suffered a stroke and was unable to work thereafter. The same year the Pells moved to South Hadley, Massachusetts

South Hadley (, ) is a New England town, town in Hampshire County, Massachusetts, United States. The population was 18,150 at the 2020 United States census, 2020 census. It is part of the Springfield metropolitan area, Massachusetts.

South Hadle ...

where Anna taught at Mount Holyoke College

Mount Holyoke College is a Private college, private Women's colleges in the United States, women's Liberal arts colleges in the United States, liberal arts college in South Hadley, Massachusetts, United States. It is the oldest member of the h ...

. In 1918 they moved again to Bryn Mawr, Pennsylvania

Bryn Mawr (, from Welsh language, Welsh for 'big hill') is a census-designated place (CDP) located in Pennsylvania, United States. It is located just west of Philadelphia along Lancaster Avenue, also known as U.S. Route 30 in Pennsylvania, U.S. ...

where Anna taught at Bryn Mawr College

Bryn Mawr College ( ; Welsh language, Welsh: ) is a Private college, private Women's colleges in the United States, women's Liberal arts colleges in the United States, liberal arts college in Bryn Mawr, Pennsylvania, United States. Founded as a ...

. Alexander Pell died in Bryn Mawr in 1921.

Despite his past as a political activist Alexander Pell was not much involved in American politics although he always voted for the Republican Party (his former comrades from Narodnaya Volya considered Republicans "ultra-bourgeois"). His opinion about his former country was strongly negative. He never spoke Russian at home. During the Russo-Japanese War

The Russo-Japanese War (8 February 1904 – 5 September 1905) was fought between the Russian Empire and the Empire of Japan over rival imperial ambitions in Manchuria and the Korean Empire. The major land battles of the war were fought on the ...

he supported Japan. After the October Revolution

The October Revolution, also known as the Great October Socialist Revolution (in Historiography in the Soviet Union, Soviet historiography), October coup, Bolshevik coup, or Bolshevik revolution, was the second of Russian Revolution, two r ...

and beginning of the Red Terror

The Red Terror () was a campaign of political repression and Mass killing, executions in Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic, Soviet Russia which was carried out by the Bolsheviks, chiefly through the Cheka, the Bolshevik secret police ...

he wrote: "Accursed Russia: even after liberating herself, she does not let people live".p. 120 (Internet Archive)/ref>

Dr. Alexander Pell scholarship

In 1952, Anna Johnson Pell Wheeler established the ''Dr. Alexander Pell scholarship''. The fund continues to operate. It is given to prominent undergraduates majoring in mathematics.References

Bibliography

* *David C. Rapoport, ''Terrorism: The first or anarchist wave'', Taylor & Francis, 2006,External links

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Degayev, Sergey Revolutionaries from the Russian Empire Okhrana informants 20th-century American mathematicians Johns Hopkins University alumni University of South Dakota faculty Illinois Institute of Technology faculty 1857 births 1921 deaths Emigrants from the Russian Empire to the United States People from Vermillion, South Dakota