Jesse Alexander Helms Jr. (October 18, 1921 – July 4, 2008) was an American politician. A leader in the

conservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilization in ...

movement, he served as a senator from North Carolina from 1973 to 2003. As chairman of the

Senate Foreign Relations Committee

The United States Senate Committee on Foreign Relations is a standing committee of the U.S. Senate charged with leading foreign-policy legislation and debate in the Senate. It is generally responsible for overseeing and funding foreign aid ...

from 1995 to 2001, he had a major voice in foreign policy. Helms helped organize and fund the conservative resurgence in the 1970s, focusing on

Ronald Reagan's quest for the White House as well as helping many local and regional candidates.

On domestic social issues, Helms opposed

civil rights

Civil and political rights are a class of rights that protect individuals' freedom from infringement by governments, social organizations, and private individuals. They ensure one's entitlement to participate in the civil and political life ...

,

disability rights

The disability rights movement is a global new social movements, social movement that seeks to secure equal opportunity, equal opportunities and equality before the law, equal rights for all people with disability, disabilities.

It is made u ...

,

environmentalism

Environmentalism or environmental rights is a broad Philosophy of life, philosophy, ideology, and social movement regarding concerns for environmental protection and improvement of the health of the environment (biophysical), environment, par ...

,

feminism

Feminism is a range of socio-political movements and ideologies that aim to define and establish the political, economic, personal, and social equality of the sexes. Feminism incorporates the position that society prioritizes the male po ...

,

gay rights

Rights affecting lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people vary greatly by country or jurisdiction—encompassing everything from the legal recognition of same-sex marriage to the death penalty for homosexuality.

Notably, , ...

,

affirmative action, access to

abortions

Abortion is the termination of a pregnancy by removal or expulsion of an embryo or fetus. An abortion that occurs without intervention is known as a miscarriage or "spontaneous abortion"; these occur in approximately 30% to 40% of pregnan ...

, the

Religious Freedom Restoration Act

The Religious Freedom Restoration Act of 1993, Pub. L. No. 103-141, 107 Stat. 1488 (November 16, 1993), codified at through (also known as RFRA, pronounced "rifra"), is a 1993 United States federal law that "ensures that interests in religio ...

(RFRA), and the

National Endowment for the Arts

The National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) is an independent agency of the United States federal government that offers support and funding for projects exhibiting artistic excellence. It was created in 1965 as an independent agency of the federa ...

. Helms brought an "aggressiveness" to his conservatism, as in his rhetoric against

homosexuality

Homosexuality is romantic attraction, sexual attraction, or sexual behavior between members of the same sex or gender. As a sexual orientation, homosexuality is "an enduring pattern of emotional, romantic, and/or sexual attractions" to pe ...

.

''

The Almanac of American Politics

''The Almanac of American Politics'' is a reference work published biennially by Columbia Books & Information Services. It aims to provide a detailed look at the politics of the United States through an approach of profiling individual leaders and ...

'' once wrote that "no American politician is more controversial, beloved in some quarters and hated in others, than Jesse Helms".

As chairman of the powerful Senate Foreign Relations Committee, he demanded an anti-communist foreign policy. His relations with the State Department were often acrimonious, and he blocked numerous presidential appointees.

Helms was the longest-serving popularly elected Senator in North Carolina's history. He was widely credited with shifting the one-party state into a competitive two-party state. He advocated the movement of conservatives from the Democratic Party – which they deemed too liberal – to the Republican Party. The Helms-controlled

National Congressional Club

The National Congressional Club (NCC) was a political action committee formed by Tom Ellis in 1973 and controlled by Jesse Helms, who served as a Republican Senator from North Carolina from 1973 to 2003. The NCC was originally established as the ...

's state-of-the-art

direct mail

Advertising mail, also known as direct mail (by its senders), junk mail (by its recipients), mailshot or admail (North America), letterbox drop or letterboxing (Australia) is the delivery of advertising material to recipients of postal mail. The d ...

operation raised millions of dollars for Helms and other conservative candidates, allowing Helms to outspend his opponents in most of his campaigns. Helms was considered the most stridently conservative American politician of the post-1960s era, especially in opposition to federal intervention into what he considered state affairs (including legislating

integration

Integration may refer to:

Biology

* Multisensory integration

* Path integration

* Pre-integration complex, viral genetic material used to insert a viral genome into a host genome

*DNA integration, by means of site-specific recombinase technolo ...

via the

Civil Rights Act of 1964

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 () is a landmark civil rights and labor law in the United States that outlaws discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex, and national origin. It prohibits unequal application of voter registration req ...

and enforcing suffrage through the

Voting Rights Act of 1965

The suffrage, Voting Rights Act of 1965 is a landmark piece of Federal government of the United States, federal legislation in the United States that prohibits racial discrimination in voting. It was signed into law by President of the United ...

).

Childhood and education (1921–1940)

Helms was born in 1921 in

Monroe, North Carolina

Monroe is a city in and the county seat of Union County, North Carolina, United States. The population increased from 32,797 in 2010 to 34,551 in 2020. It is within the rapidly growing Charlotte metropolitan area. Monroe has a council-manager ...

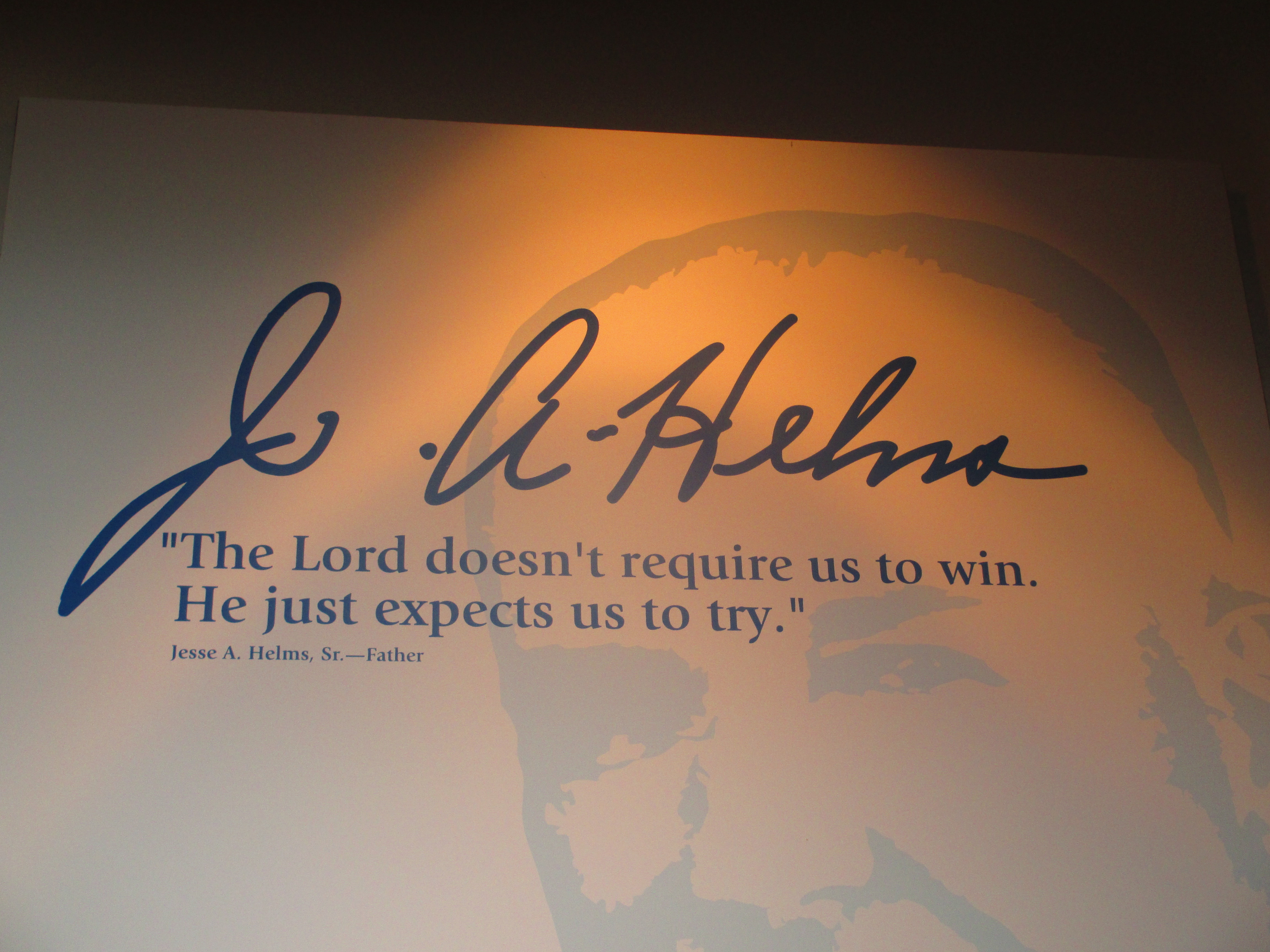

, where his father, nicknamed "Big Jesse", served as both fire chief and chief of police; his mother, Ethel Mae Helms, was a homemaker. Helms was of English ancestry on both sides.

[Link (2008) ch 1] Helms described Monroe as a community surrounded by farmland and with a population of about three thousand where "you knew just about everybody and just about everybody knew you."

The Helms family was poor during the

Great Depression, resulting in each of the children working from an early age. Helms acquired his first job sweeping floors at ''The Monroe Enquirer'' at age 9.

The family attended services each Sunday at First Baptist, Helms later saying he would never forget being served chickens raised in the family's backyard by his mother, following their weekly services. He recalled initially being bothered by their chickens becoming their food, but abandoned this view to allow himself to concentrate on his mother's cooking.

Helms recalled that his family rarely spoke about politics, reasoning that the political climate did not call for discussions as most of the people the family were acquainted with were members of the

Democratic Party Democratic Party most often refers to:

*Democratic Party (United States)

Democratic Party and similar terms may also refer to:

Active parties Africa

*Botswana Democratic Party

*Democratic Party of Equatorial Guinea

*Gabonese Democratic Party

*Demo ...

.

Link described Helms's father as having a domineering influence on the child's development, describing the pair as being similar in having the traits of being extrovert, effusive, and enjoying the company of others while both favored constancy, loyalty, and respect for order. The elder Helms asserted to Jesse that ambition was good and accomplishments and achievements would come his way through following a strict work ethic. Years later, Helms retained fond memories of his father's involvement with his youth: "I shall forever have wonderful memories of a caring, loving father who took the time to listen and to explain things to his wide-eyed son." In high school, Helms was voted "Most Obnoxious" in his senior yearbook.

Helms briefly attended Wingate Junior College, now

Wingate University

Wingate University is a private Baptist university with campuses in Wingate, Charlotte, and Hendersonville, North Carolina. It is affiliated with the Baptist State Convention of North Carolina (Southern Baptist Convention).

The university enr ...

, near Monroe, before leaving for

Wake Forest College

Wake Forest University is a private research university in Winston-Salem, North Carolina. Founded in 1834, the university received its name from its original location in Wake Forest, north of Raleigh, North Carolina. The Reynolda Campus, the un ...

. He left Wingate after a year to begin a career as a

journalist

A journalist is an individual that collects/gathers information in form of text, audio, or pictures, processes them into a news-worthy form, and disseminates it to the public. The act or process mainly done by the journalist is called journalism ...

, working for the next eleven years as a newspaper and radio reporter, first as a sportswriter and news reporter for Raleigh's ''

The News & Observer

''The News & Observer'' is an American regional daily newspaper that serves the greater Triangle area based in Raleigh, North Carolina. The paper is the largest in circulation in the state (second is the '' Charlotte Observer''). The paper has be ...

'', and also as assistant city editor for ''

The Raleigh Times

The ''Raleigh Times'' was the afternoon newspaper in Raleigh, North Carolina. The history of the paper dates back to the ''Evening Visitor'', first published in 1879. The ''Visitor'' later bought out other rival afternoon papers, the ''Daily Pres ...

''. Helms retained a positive view of Wingate into his later years, saying the school was filled with individuals that treated him with kindness and that he had made it an objective to repay the institution for what it had done for him. While attending Wake Forest, Helms left work early and ran a few blocks to catch a train every morning to ensure he was on time to his classes. Helms stated that his goal in attending was never to get a diploma but instead form the skills needed for forms of employment he was seeking at a time when he aspired to become a journalist.

Marriage and family

Helms met Dorothy "Dot" Coble, editor of the

society page

In journalism, the society page of a newspaper is largely or entirely devoted to the social and cultural events and gossip of the location covered. Other features that frequently appear on the society page are a calendar of charity events and pic ...

at ''The News & Observer'', and they married in 1942. Helms's first interest in politics came from conversations with his conservative father-in-law.

In 1945, his and Dot's first child Jane was born.

Early career (1940–1972)

Helms's first full-time job after college was as a

sports reporter with ''

The Raleigh Times

The ''Raleigh Times'' was the afternoon newspaper in Raleigh, North Carolina. The history of the paper dates back to the ''Evening Visitor'', first published in 1879. The ''Visitor'' later bought out other rival afternoon papers, the ''Daily Pres ...

''.

During

World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

, Helms served stateside as a recruiter in the

United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage ...

.

After the war, he pursued his twin interests of journalism and

Democratic Party Democratic Party most often refers to:

*Democratic Party (United States)

Democratic Party and similar terms may also refer to:

Active parties Africa

*Botswana Democratic Party

*Democratic Party of Equatorial Guinea

*Gabonese Democratic Party

*Demo ...

politics. Helms became the city news editor of ''The Raleigh Times.'' He later became a radio and television newscaster and commentator for ''

WRAL-TV

WRAL-TV (channel 5) is a television station licensed to Raleigh, North Carolina, United States, serving as the NBC affiliate for the Research Triangle area. It is the flagship station of the locally based Capitol Broadcasting Company, which h ...

'', where he hired

Armistead Maupin

Armistead Jones Maupin, Jr. ( ) (born May 13, 1944) is an American writer notable for ''Tales of the City'', a series of novels set in San Francisco.

Early life

Maupin was born in Washington, D.C., to Diana Jane (Barton) and Armistead Jones Mau ...

as a reporter.

Entry into politics

In 1950, Helms played a critical role as campaign publicity director for

Willis Smith in the U.S. Senate campaign against a prominent

liberal,

Frank Porter Graham

Frank Porter Graham (October 14, 1886 – February 16, 1972) was an American educator and political activist. A professor of history, he was elected President of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in 1930, and he later became the firs ...

.

Smith (a conservative Democratic lawyer and former president of the

American Bar Association

The American Bar Association (ABA) is a voluntary bar association of lawyers and law students, which is not specific to any jurisdiction in the United States. Founded in 1878, the ABA's most important stated activities are the setting of acad ...

) portrayed Graham, who supported school

desegregation

Desegregation is the process of ending the separation of two groups, usually referring to races. Desegregation is typically measured by the index of dissimilarity, allowing researchers to determine whether desegregation efforts are having impact o ...

, as a "dupe of communists" and a proponent of the "

mingling of the races".

Smith's fliers said, "Wake Up, White People",

in the campaign for the virtually all-

white primaries

White primaries were primary elections held in the Southern United States in which only white voters were permitted to participate. Statewide white primaries were established by the state Democratic Party units or by state legislatures in South Car ...

. Blacks were still mostly

disfranchised in the state, because its 1900 constitutional amendment had been passed by white Democrats with restrictive voter registration and electoral provisions that effectively and severely reduced their role in electoral politics.

Smith won and hired Helms as his administrative assistant in Washington. In 1952, Helms worked on the presidential

campaign

Campaign or The Campaign may refer to:

Types of campaigns

* Campaign, in agriculture, the period during which sugar beets are harvested and processed

* Advertising campaign, a series of advertisement messages that share a single idea and theme

* B ...

of

Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the Southeast United States

Georgia may also refer to:

Places

Historical states and entities

* Related to t ...

Senator

Richard Russell Jr. After Russell dropped out of the presidential race, Helms returned to working for Smith. When Smith died in 1953, Helms returned to Raleigh.

From 1953 to 1960, Helms was executive director of the North Carolina Bankers Association. He and his wife set up their home on Caswell Street in the

Hayes Barton Historic District, where he lived the rest of his life.

In 1957, Helms as a Democrat won his first election for a

Raleigh City Council

Raleigh City Council is the governing body for the city of Raleigh, the state capital of North Carolina.

Raleigh is governed by council-manager government. It is composed of eight members, including the Mayor of Raleigh. Five of the members a ...

seat. He served two terms and earned a reputation as a conservative gadfly who "fought against everything from putting a median strip on Downtown Boulevard to an

urban renewal

Urban renewal (also called urban regeneration in the United Kingdom and urban redevelopment in the United States) is a program of land redevelopment often used to address urban decay in cities. Urban renewal involves the clearing out of bligh ...

project".

Helms disliked his tenure on the council, feeling all the other members acted as a private club and that Mayor

William G. Enloe was a "steamroller". In 1960, Helms worked on the unsuccessful primary gubernatorial campaign of

I. Beverly Lake Sr.

Isaac Beverly Lake Sr. (1906–1996), was an American jurist, law professor at Wake Forest University and Campbell University, and politician. He was born in Wake Forest, North Carolina.

Early career

A graduate of Wake Forest College and Harv ...

, who ran on a platform of

racial segregation

Racial segregation is the systematic separation of people into racial or other ethnic groups in daily life. Racial segregation can amount to the international crime of apartheid and a crime against humanity under the Statute of the Intern ...

.

[ ]

Link to book profile

accessed on July 14, 2008 on Google Books. Lake lost to

Terry Sanford

James Terry Sanford (August 20, 1917April 18, 1998) was an American lawyer and politician from North Carolina. A member of the Democratic Party, Sanford served as the 65th Governor of North Carolina from 1961 to 1965, was a two-time U.S. presi ...

, who ran as a racial moderate willing to implement the federal policy of school integration. Helms felt

forced busing

Race-integration busing in the United States (also known simply as busing, Integrated busing or by its critics as forced busing) was the practice of assigning and transporting students to schools within or outside their local school districts in ...

and forced racial integration caused animosity on both sides and "proved to be unwise".

Capitol Broadcasting Company

In 1960, Helms joined the Raleigh-based

Capitol Broadcasting Company

The Capitol Broadcasting Company, Inc. (CBC) is an American media company based in Raleigh, North Carolina. Capitol owns three television stations and nine radio stations in the Raleigh–Durham and Wilmington areas of North Carolina and the ...

(CBC) as the executive vice-president, vice chairman of the board, and assistant chief executive officer. His daily CBC editorials on

WRAL-TV

WRAL-TV (channel 5) is a television station licensed to Raleigh, North Carolina, United States, serving as the NBC affiliate for the Research Triangle area. It is the flagship station of the locally based Capitol Broadcasting Company, which h ...

, given at the end of each night's local news broadcast in Raleigh, made Helms famous as a conservative commentator throughout eastern North Carolina.

Helms's editorials featured folksy anecdotes interwoven with conservative views against "the civil rights movement, the liberal news media, and anti-war churches", among many targets.

He referred to ''

The News and Observer

''The News & Observer'' is an American regional daily newspaper that serves the greater Triangle area based in Raleigh, North Carolina. The paper is the largest in circulation in the state (second is the '' Charlotte Observer''). The paper has be ...

'', his former employer, as the "Nuisance and Disturber" for its promotion of liberal views and support for African-American civil rights activities.

The

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

A university () is an institution of higher (or tertiary) education and research which awards academic degrees in several academic disciplines. ''University'' is derived from the Latin phrase ''universitas magistrorum et scholarium'', which r ...

, which had a reputation for liberalism, was also a frequent target of Helms's criticism. He is said to have referred to the university as "The University of Negroes and Communists" despite a lack of evidence,

and suggested a wall be erected around the campus to prevent the university's liberal views from "infecting" the rest of the state. Helms said the civil rights movement was infested by

Communists

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, a ...

and "moral degenerates". He described the federal program of

Medicaid

Medicaid in the United States is a federal and state program that helps with healthcare

Health care or healthcare is the improvement of health via the prevention, diagnosis, treatment, amelioration or cure of disease, illness, injury, and ...

as a "step over into the swampy field of socialized medicine".

Commenting on the 1963 protests and

March on Washington

The March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, also known as simply the March on Washington or The Great March on Washington, was held in Washington, D.C., on August 28, 1963. The purpose of the march was to advocate for the civil and economic rig ...

during the

Civil Rights Movement

The civil rights movement was a nonviolent social and political movement and campaign from 1954 to 1968 in the United States to abolish legalized institutional Racial segregation in the United States, racial segregation, Racial discrimination ...

, Helms stated, "The negro cannot count forever on the kind of restraint that's thus far left him free to clog the streets, disrupt traffic, and interfere with other men's rights."

He later wrote, "Crime rates and irresponsibility among Negroes are facts of life which must be faced."

He was at Capitol Broadcasting Company until he filed for the Senate race in 1972.

Senate campaign of 1972

Helms announced his candidacy for a seat in the

United States Senate

The United States Senate is the upper chamber of the United States Congress, with the House of Representatives being the lower chamber. Together they compose the national bicameral legislature of the United States.

The composition and ...

in 1972. His Republican primary campaign was managed by

Thomas F. Ellis, who would later be instrumental in

Ronald Reagan's 1976 campaign and also become the chair of the

National Congressional Club

The National Congressional Club (NCC) was a political action committee formed by Tom Ellis in 1973 and controlled by Jesse Helms, who served as a Republican Senator from North Carolina from 1973 to 2003. The NCC was originally established as the ...

. Helms took the Republican primary, winning 92,496 votes, or 60.1%, in a three-candidate field.

Meanwhile, Democrats retired the ailing Senator

B. Everett Jordan, who lost his primary to Congressman

Nick Galifianakis Nick Galifianakis may refer to:

*Nick Galifianakis (politician)

Nick Galifianakis (born July 22, 1928) is a former American politician who served as a Democratic U.S. Congressman from North Carolina from 1967 to 1973.

Life and career

Galifiana ...

. The latter represented the "new politics" of voters who included the young, African Americans voting since federal legislation removed discriminatory restrictions, and anti-establishment activists, who were based in and around the urban

Research Triangle

The Research Triangle, or simply The Triangle, are both common nicknames for a metropolitan area in the Piedmont region of North Carolina in the United States, anchored by the cities of Raleigh and Durham and the town of Chapel Hill, home to ...

and

Piedmont Triad

The Piedmont Triad (or simply the Triad) is a metropolitan region in the north-central part of the U.S. state of North Carolina anchored by three cities: Greensboro, Winston-Salem, and High Point. This close group of cities lies in the Piedm ...

. Although Galifianakis was a "liberal" by North Carolina standards, he opposed

busing to achieve integration in schools.

Polls put Galifianakis well ahead until late in the campaign, but Helms, facing all but certain defeat, hired a professional campaign manager, F. Clifton White, giving him dictatorial control over campaign strategy. While Galifianakis avoided mention of his party's presidential candidate, the liberal

George McGovern

George Stanley McGovern (July 19, 1922 – October 21, 2012) was an American historian and South Dakota politician who was a U.S. representative and three-term U.S. senator, and the Democratic Party presidential nominee in the 1972 pre ...

,

Helms employed the slogans "McGovernGalifianakis – one and the same", "Vote for Jesse. Nixon Needs Him" and "Jesse: He's One of Us", an implicit play suggesting his opponent's Greek heritage made him somehow less "American".

Helms won the support of numerous Democrats, especially in the conservative eastern part of the state. Galifianakis tried to woo Republicans by noting that Helms had earlier criticized Nixon as being too left-wing.

In a taste of things to come, money poured into the race. Helms spent a record $654,000,

much of it going toward carefully crafted television commercials portraying him as a soft-spoken mainstream conservative. In the final six weeks of the campaign, Helms outspent Galifianakis three-to-one.

Though the year was marked by Democratic gains in the Senate,

Helms won 54 percent of the vote to Galifianakis's 46 percent. He was elected as the first Republican senator from the state since 1903, before senators were directly elected, and when the Republican Party stood for a different tradition.

Helms was helped by

Richard Nixon

Richard Milhous Nixon (January 9, 1913April 22, 1994) was the 37th president of the United States, serving from 1969 to 1974. A member of the Republican Party, he previously served as a representative and senator from California and was t ...

's gigantic landslide victory in that year's presidential election;

Nixon carried North Carolina by 40 points.

First Senate term (1973–79)

Entering the Senate

Helms quickly became a "star" of the conservative movement, and was particularly vociferous on the issue of

abortion

Abortion is the termination of a pregnancy by removal or expulsion of an embryo or fetus. An abortion that occurs without intervention is known as a miscarriage or "spontaneous abortion"; these occur in approximately 30% to 40% of pregn ...

. In 1974, in the wake of the US Supreme Court's decision in ''

Roe v. Wade

''Roe v. Wade'', 410 U.S. 113 (1973),. was a landmark decision of the U.S. Supreme Court in which the Court ruled that the Constitution of the United States conferred the right to have an abortion. The decision struck down many federal and ...

'', Helms introduced a constitutional amendment that would have prohibited abortion in all circumstances, by conferring

due process

Due process of law is application by state of all legal rules and principles pertaining to the case so all legal rights that are owed to the person are respected. Due process balances the power of law of the land and protects the individual pe ...

rights upon every

fetus

A fetus or foetus (; plural fetuses, feti, foetuses, or foeti) is the unborn offspring that develops from an animal embryo. Following embryonic development the fetal stage of development takes place. In human prenatal development, fetal develo ...

.

However, the Senate hearing into the proposed amendments heard that neither Helms', nor

James L. Buckley

James Lane Buckley (born March 9, 1923) is an American politician, jurist, and lawyer who currently serves as a senior judge on the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit. Buckley served in the United States Senat ...

's similar amendment, would achieve their stated goal, and shelved them for the session.

Both Helms and Buckley proposed amendments again in 1975, with Helms's amendment allowing states leeway in their implementation of an enshrined constitutional "right to life" from the "moment of fertilization".

Helms was also a prominent advocate of

free enterprise

In economics, a free market is an economic system in which the prices of goods and services are determined by supply and demand expressed by sellers and buyers. Such markets, as modeled, operate without the intervention of government or any ot ...

and favored cutting the budget. He was a strong advocate of a global return to the

gold standard

A gold standard is a Backed currency, monetary system in which the standard economics, economic unit of account is based on a fixed quantity of gold. The gold standard was the basis for the international monetary system from the 1870s to the ...

,

which he would push at numerous points throughout his Senate career; in October 1977, Helms proposed a successful amendment that allowed United States citizens to sign contracts linked to gold, overturning a 44-year ban on gold-indexed contracts, reflecting fears of inflation. Helms supported the tobacco industry,

which contributed more than 6% of the state's

GSP until the 1990s (the highest in the country); he argued that federal price support programs should be maintained, as they did not constitute a

subsidy

A subsidy or government incentive is a form of financial aid or support extended to an economic sector (business, or individual) generally with the aim of promoting economic and social policy. Although commonly extended from the government, the ter ...

but insurance.

Helms offered an amendment that would have denied food stamps to strikers when the Senate approved increasing federal contributions to food stamp and school lunch programs in May 1974.

In 1973, the

United States Congress

The United States Congress is the legislature of the federal government of the United States. It is bicameral, composed of a lower body, the House of Representatives, and an upper body, the Senate. It meets in the U.S. Capitol in Washi ...

passed the

Helms Amendment Helms Amendment may refer one of two legislative actions initiated by US Senator Jesse Helms:

* Helms Amendment to the Foreign Assistance Act, US legislation designed to limit the use of foreign assistance funds for abortion.

* Helms AIDS Amendment ...

to the

Foreign Assistance Act

The Foreign Assistance Act (, et seq.) is a United States law governing foreign aid policy. It outlined the political and ideological principles of U.S. foreign aid, significantly overhauled and reorganized the structure U.S. foreign assistance ...

. It states that, "no foreign assistance funds may be used to pay for the performance of abortion as a method of family planning or to motivate or coerce any person to practice abortions."

In January 1973, along with Democrats

James Abourezk

James George Abourezk (born February 24, 1931) is an American attorney and Democratic politician who served as a United States senator and United States representative from South Dakota. He did not seek re-election to the US Senate in 1978. He wa ...

and

Floyd Haskell

Floyd Kirk Haskell (February 7, 1916August 25, 1998) was an American lawyer and politician. A member of the Democratic Party, he served as a U.S. Senator from Colorado from 1973 to 1979.

Early life and career

Floyd Haskell was born in Morristo ...

, Helms was one of three senators to vote against the confirmation of

Peter J. Brennan

Peter Joseph Brennan (May 24, 1918 – October 2, 1996) was an American labor activist and politician who served as United States Secretary of Labor from February 2, 1973 until March 15, 1975 in the administrations of Presidents Nixon and Ford. B ...

as

United States Secretary of Labor

The United States Secretary of Labor is a member of the Cabinet of the United States, and as the head of the United States Department of Labor, controls the department, and enforces and suggests laws involving unions, the workplace, and all ot ...

.

In May 1974, when the Senate approved the establishment of no‐fault automobile insurance plans in every state, it rejected an amendment by Helms exempting states that were opposed to no‐fault insurance.

Foreign policy

From the start, Helms identified as a prominent anti-communist. He proposed an act in 1974 that authorized the President to grant

honorary citizenship

Honorary citizenship is a status bestowed by a city or other government on a foreign or native individual whom it considers to be especially admirable or otherwise worthy of the distinction. The honour usually is symbolic and does not confer an ...

to

Soviet

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...

dissident

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn

Aleksandr Isayevich Solzhenitsyn. (11 December 1918 – 3 August 2008) was a Russian novelist. One of the most famous Soviet dissidents, Solzhenitsyn was an outspoken critic of communism and helped to raise global awareness of political repress ...

. He remained close to Solzhenitsyn's cause, and linked his fight to that of freedom throughout the world. In 1975, as

North Vietnam

North Vietnam, officially the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (DRV; vi, Việt Nam Dân chủ Cộng hòa), was a socialist state supported by the Soviet Union (USSR) and the People's Republic of China (PRC) in Southeast Asia that existed f ...

ese forces

approached Saigon, Helms was foremost among those urging the US to evacuate all Vietnamese demanding this, which he believed could be "two million or more within seven days". When the

Senate Armed Services Committee

The Committee on Armed Services (sometimes abbreviated SASC for ''Senate Armed Services Committee'') is a committee of the United States Senate empowered with legislative oversight of the nation's military, including the Department of Def ...

voted to suppress a report critical of the US's strategic position in the

arms race, Helms read the entire report out, requiring it to be published in full in the ''

Congressional Record

The ''Congressional Record'' is the official record of the proceedings and debates of the United States Congress, published by the United States Government Publishing Office and issued when Congress is in session. The Congressional Record In ...

''.

Helms was not at first a strong supporter of Israel; for instance, in 1973 he proposed a resolution demanding Israel return the

West Bank

The West Bank ( ar, الضفة الغربية, translit=aḍ-Ḍiffah al-Ġarbiyyah; he, הגדה המערבית, translit=HaGadah HaMaʽaravit, also referred to by some Israelis as ) is a landlocked territory near the coast of the Mediter ...

to

Jordan

Jordan ( ar, الأردن; tr. ' ), officially the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan,; tr. ' is a country in Western Asia. It is situated at the crossroads of Asia, Africa, and Europe, within the Levant region, on the East Bank of the Jordan Ri ...

, and, in 1975, demanding that the Palestinian Arabs receive a "just settlement of their grievances".

[Link (2007), p. 318] In 1977, Helms was the sole senator to vote against prohibiting American companies from joining the

Arab League boycott of Israel, but that was primarily because the bill also relaxed discrimination against Communist countries. In 1982, Helms called for the US to break diplomatic relations with Israel during the

1982 Lebanon War

The 1982 Lebanon War, dubbed Operation Peace for Galilee ( he, מבצע שלום הגליל, or מבצע של"ג ''Mivtsa Shlom HaGalil'' or ''Mivtsa Sheleg'') by the Israeli government, later known in Israel as the Lebanon War or the First L ...

. He favored prohibiting foreign aid to countries that had recently detonated nuclear weapons: this was aimed squarely at India, but it also affected Israel should it conduct a

nuclear test

Nuclear weapons tests are experiments carried out to determine nuclear weapons' effectiveness, Nuclear weapon yield, yield, and explosive capability. Testing nuclear weapons offers practical information about how the weapons function, how detona ...

. He worked to support the supply of arms to the United States' Arab allies under presidents Carter and Reagan, until his views on Israel shifted significantly in 1984.

Helms and

Bob Dole

Robert Joseph Dole (July 22, 1923 – December 5, 2021) was an American politician and attorney who represented Kansas in the United States Senate from 1969 to 1996. He was the Republican Leader of the Senate during the final 11 years of his ...

offered an amendment in 1973 that would have delayed cutting off funding for bombing in

Cambodia

Cambodia (; also Kampuchea ; km, កម្ពុជា, UNGEGN: ), officially the Kingdom of Cambodia, is a country located in the southern portion of the Indochinese Peninsula in Southeast Asia, spanning an area of , bordered by Thailan ...

if the President informed Congress that North Vietnam was not making an accounting "to the best of its ability" of US servicemen missing in

Southeast Asia

Southeast Asia, also spelled South East Asia and South-East Asia, and also known as Southeastern Asia, South-eastern Asia or SEA, is the geographical United Nations geoscheme for Asia#South-eastern Asia, south-eastern region of Asia, consistin ...

. The amendment was defeated by a vote of 56 to 25.

Nixon resignation

Helms delivered a Senate speech blaming liberal media for distorting Watergate and questioned if President Nixon had a constitutional right to be considered innocent until proven guilty following the April 1973 revelation of details relating to the scandal and Nixon administration aides resigning. He advocated against illegal activities being condoned with concurrent "half-truth and allegations" being reported by the media. Helms had four separate meetings with President Nixon in April and May 1973 where he attempted to cheer up the president and called for the White House to challenge its critics even as fellow Republicans from North Carolina criticized Nixon. Helms opposed the creation of the Senate Select Committee to Investigate Campaign Practices in the summer of 1973, even as it was chaired by fellow North Carolina Senator

Sam Ervin

Samuel James Ervin Jr. (September 27, 1896April 23, 1985) was an American politician. A Democrat, he served as a U.S. Senator from North Carolina from 1954 to 1974. A native of Morganton, he liked to call himself a "country lawyer", and often to ...

, arguing that it was a ploy by Democrats to discredit and oust Nixon.

[Link (2008), pp. 137–138]

In August 1974, ''

Newsweek

''Newsweek'' is an American weekly online news magazine co-owned 50 percent each by Dev Pragad, its president and CEO, and Johnathan Davis, who has no operational role at ''Newsweek''. Founded as a weekly print magazine in 1933, it was widely ...

'' published a list by the White House including Helms as one of thirty-six senators that the administration believed would support President Nixon in the event of his impeachment and being brought to trial by the Senate. The article stated that some supporters were not fully convinced and this would further peril the administration as 34 were needed to prevent conviction. Nixon resigned days later and kept contact with Helms during his post-presidency, calling Helms to either chat or offer advice.

[

]

1976 presidential election

Helms supported Ronald Reagan for the presidential nomination in 1976, even before Reagan had announced his candidacy. His contribution was crucial in the North Carolina primary victory that paved the way for Reagan's presidential election in 1980. The support of Helms, alongside Raleigh-based campaign operative Thomas F. Ellis, was instrumental in Reagan's winning the North Carolina primary and later presenting a major challenge to incumbent President Gerald Ford

Gerald Rudolph Ford Jr. ( ; born Leslie Lynch King Jr.; July 14, 1913December 26, 2006) was an American politician who served as the 38th president of the United States from 1974 to 1977. He was the only president never to have been elected ...

at the 1976 Republican National Convention

The 1976 Republican National Convention was a United States political convention of the Republican Party that met from August 16 to August 19, 1976, to select the party's nominee for President. Held in Kemper Arena in Kansas City, Missouri, t ...

. According to author Craig Shirley

Craig Paul Shirley (born September 24, 1956) is a conservative American political consultant and author of the 2011 New York Times bestseller "December 1941", as well as four books on Ronald Reagan.

Life and career

Youth and education

Shirley ...

, the two men deserve credit "for breathing life into the dying Reagan campaign". Going into the primary, Reagan had lost all the primaries, including in New Hampshire, where he had been favored, and was two million dollars in debt, with a growing number of Republican leaders calling for his exit.[Shirley (2005), p. 176] The Ford campaign was predicting a victory in North Carolina, but assessed Reagan's strength in the state simply: Helms's support. While Ford had the backing of Governor James Holshouser

James Eubert Holshouser Jr. (October 8, 1934 – June 17, 2013) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 68th Governor of North Carolina from 1973 to 1977. He was the first Republican candidate to be elected as governor of the ...

, the grassroots movement formed in North Carolina by Ellis and backed by Helms delivered an upset victory by 53% to 47%. The momentum generated in North Carolina carried Ronald Reagan to landslide primary wins in Texas, California, and other critical states, evening the contest between Reagan and Ford, and forcing undeclared delegates to choose at the 1976 convention.

Later, Helms was not pleased by the announcement that Reagan, if nominated, would ask the 1976 Republican National Convention to make moderate Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania (; (Pennsylvania Dutch: )), officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a state spanning the Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes regions of the United States. It borders Delaware to its southeast, Ma ...

Senator Richard Schweiker

Richard Schultz Schweiker (June 1, 1926 – July 31, 2015) was an American businessman and politician. A member of the Republican Party, he served as the 14th U.S. Secretary of Health and Human Services under President Ronald Reagan from 1 ...

his running mate for the general election, but kept his objections to himself at the time.[Shirley (2005), p. 275] According to Helms, after Reagan told him of the decision, Helms noted the hour because, "I wanted to record for posterity the exact time I received the shock of my life."Strom Thurmond

James Strom Thurmond Sr. (December 5, 1902June 26, 2003) was an American politician who represented South Carolina in the United States Senate from 1954 to 2003. Prior to his 48 years as a senator, he served as the 103rd governor of South Caro ...

tried to make Reagan drop Schweiker for a conservative, perhaps either James Buckley or his brother William F. Buckley Jr.

William Frank Buckley Jr. (born William Francis Buckley; November 24, 1925 – February 27, 2008) was an American public intellectual, conservative author and political commentator. In 1955, he founded ''National Review'', the magazine that stim ...

, and rumors surfaced that Helms might run for vice president himself,[Shirley (2005), p. 311] but Schweiker was kept. In the end, Reagan lost narrowly to Ford at the convention, while Helms received only token support for the vice presidential nomination, albeit enough to place him second, far behind Ford's choice of Bob Dole

Robert Joseph Dole (July 22, 1923 – December 5, 2021) was an American politician and attorney who represented Kansas in the United States Senate from 1969 to 1996. He was the Republican Leader of the Senate during the final 11 years of his ...

. The Convention adopted a broadly conservative platform, and the conservative faction came out acting like the winners; except Jesse Helms.

Helms vowed to campaign actively for Ford across the South, regarding the conservative platform adopted at the convention to be a "mandate" on which Ford was pledging to run. However, he targeted Henry Kissinger

Henry Alfred Kissinger (; ; born Heinz Alfred Kissinger, May 27, 1923) is a German-born American politician, diplomat, and geopolitical consultant who served as United States Secretary of State and National Security Advisor under the preside ...

after the latter issued a statement calling Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn a "threat to world peace", and Helms demanded that Kissinger embrace the platform or resign immediately. Helms continued to back Reagan, and the two remained close friends and political allies throughout Reagan's political career, although sometimes critical of each other.1980 Republican National Convention

The 1980 Republican National Convention convened at Joe Louis Arena in Detroit, Michigan, from July 14 to July 17, 1980. The Republican National Convention nominated retired Hollywood actor and former Governor Ronald Reagan of California for pr ...

and ultimately the presidency of the United States

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States of America. The president directs the executive branch of the federal government and is the commander-in-chief of the United States ...

.

According to Craig Shirley,

Had Reagan lost North Carolina, despite his public pronouncements, his revolutionary challenge to Ford, along with his political career, would have ended unceremoniously. He would have made a gracious exit speech, cut a deal with the Ford forces to eliminate his campaign debt, made a minor speech at the Kansas City Convention later that year, and returned to his ranch in Santa Barbara. He would probably have only reemerged to make speeches and cut radio commercials to supplement his income. And Reagan would have faded into political oblivion.

Torrijos–Carter treaties

Helms was a long-time opponent of transferring possession of the Panama Canal

The Panama Canal ( es, Canal de Panamá, link=no) is an artificial waterway in Panama that connects the Atlantic Ocean with the Pacific Ocean and divides North and South America. The canal cuts across the Isthmus of Panama and is a Channel ( ...

to Panama

Panama ( , ; es, link=no, Panamá ), officially the Republic of Panama ( es, República de Panamá), is a transcontinental country spanning the southern part of North America and the northern part of South America. It is bordered by Co ...

, calling its construction an "historic American achievement".[Link (2008), p. 188] He warned that it would fall into the hands of Omar Torrijos

Omar Efraín Torrijos Herrera (February 13, 1929 – July 31, 1981) was the Commander of the Panamanian National Guard and military leader of Panama from 1968 to his death in 1981. Torrijos was never officially the president of Panama ...

's "communist friends". The issue of transfer of the canal was debated in the 1976 presidential race, wherein then-President Ford suspended negotiations over the transfer of sovereignty to assuage conservative opposition. In 1977, President Jimmy Carter

James Earl Carter Jr. (born October 1, 1924) is an American politician who served as the 39th president of the United States from 1977 to 1981. A member of the Democratic Party, he previously served as the 76th governor of Georgia from 19 ...

reopened negotiations, appointing Sol Linowitz

Sol Myron Linowitz (December 7, 1913 – March 18, 2005) was an American diplomat, lawyer, and businessman.

Early life

Linowitz was born to a Jewish family in Trenton, New Jersey. He was a graduate of Trenton Central High School, Hamilton Colle ...

as co-negotiator without Senate confirmation, and Helms and Strom Thurmond led the opposition to the transfer.bailout

A bailout is the provision of financial help to a corporation or country which otherwise would be on the brink of bankruptcy.

A bailout differs from the term ''bail-in'' (coined in 2010) under which the bondholders or depositors of global sys ...

of American banking interests. He filed two federal suits, demanding prior congressional approval of any treaty and then consent by both houses of Congress. Helms also rallied Reagan, telling him that negotiation over Panama would be a "second Schweiker" as far as his conservative base was concerned.constitutional crisis

In political science, a constitutional crisis is a problem or conflict in the function of a government that the political constitution or other fundamental governing law is perceived to be unable to resolve. There are several variations to this d ...

, cited the need for the support of United States' allies in Latin America, accused the U.S. of submitting to Panamanian blackmail, and complained that the decision threatened national security in the event of war in Europe. Helms threatened to obstruct Senate business, proposing 200 amendments to the revision of the United States criminal code, knowing that most Americans opposed the treaties and would punish congressmen who voted for them if the ratification vote came in the run-up to the election. Helms announced the results of an opinion poll showing 78% public opposition. However, Helms's and Thurmond's leadership of the opposition made it politically easier for Carter,Paul Laxalt

Paul may refer to:

*Paul (given name), a given name (includes a list of people with that name)

* Paul (surname), a list of people

People

Christianity

* Paul the Apostle (AD c.5–c.64/65), also known as Saul of Tarsus or Saint Paul, early Chr ...

.

1978 re-election campaign

Helms began campaigning for re-election in February 1977, giving himself 15 months by the time of the primaries. While he faced no primary opponent, the Democrats nominated Commissioner of Insurance

An insurance commissioner (or commissioner of insurance) is a public official in the executive branch of a state or territory in the United States who, along with his or her office, regulate the insurance industry. The powers granted to the office ...

John Ingram,populist

Populism refers to a range of political stances that emphasize the idea of "the people" and often juxtapose this group against " the elite". It is frequently associated with anti-establishment and anti-political sentiment. The term develope ...

and used low-budget campaigning,Democratic National Committee

The Democratic National Committee (DNC) is the governing body of the United States Democratic Party. The committee coordinates strategy to support Democratic Party candidates throughout the country for local, state, and national office, as well ...

targeted Helms, as did President Carter, who visited North Carolina twice on Ingram's behalf.Strom Thurmond

James Strom Thurmond Sr. (December 5, 1902June 26, 2003) was an American politician who represented South Carolina in the United States Senate from 1954 to 2003. Prior to his 48 years as a senator, he served as the 103rd governor of South Caro ...

, Helms was one of two senators named by an environmental group as part of a congressional "Dirty Dozen" that the group believed should be defeated in their re-election efforts due to their stances on environmental issues; membership on the list was based "primarily on 14 Senate and 19 House votes, including amendments to air and water pollution control laws, strip‐mining controls, auto emissions and water projects".

Over the long campaign, Helms raised $7.5 million, more than twice as much as the second most-expensive nationwide (John Tower

John Goodwin Tower (September 29, 1925 – April 5, 1991) was an American politician, serving as a Republican United States Senator from Texas from 1961 to 1985. He was the first Republican Senator elected from Texas since Reconstruction. Tow ...

's in Texas), thanks to Richard Viguerie

Richard Art Viguerie (; born September 23, 1933) is an American conservative figure, pioneer of political direct mail and writer on politics. He is the current chairman of ConservativeHQ.com.

Life and career

Viguerie was born in Golden Acres, ...

's and Alex Castellanos

Alejandro Castellanos (born 1954) is a Cuban-American political consultant. He has worked on electoral campaigns for Republican candidates including Bob Dole, George W. Bush, Jeb Bush, and Mitt Romney. In 2008, Castellanos, a partner at Nation ...

's pioneering direct mail

Advertising mail, also known as direct mail (by its senders), junk mail (by its recipients), mailshot or admail (North America), letterbox drop or letterboxing (Australia) is the delivery of advertising material to recipients of postal mail. The d ...

strategies. It was estimated that at least $3 million of Helms's contributions were spent on fund-raising. Helms easily outspent Ingram several times over, as the latter spent $150,000. Due to a punctured lumbar

In tetrapod anatomy, lumbar is an adjective that means ''of or pertaining to the abdominal segment of the torso, between the diaphragm and the sacrum.''

The lumbar region is sometimes referred to as the lower spine, or as an area of the back i ...

disc, Helms was forced to suspend campaigning for six weeks in September and October.[Link (2007), p. 199] In a low-turnout election, Helms received 619,151 votes (54.5 percent) to Ingram's 516,663 (45.5 percent).

Second Senate term (1979–1985)

New Senate term

On January 3, 1979, the first day of the new Congress, Helms introduced a constitutional amendment outlawing abortion, on which he led the conservative Senators.Sandra Day O'Connor

Sandra Day O'Connor (born March 26, 1930) is an American retired attorney and politician who served as the first female associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1981 to 2006. She was both the first woman nominated and th ...

to the US Supreme Court; their opposition hinged over the issue of O'Connor's presumed unwillingness to overturn the ''Roe v. Wade

''Roe v. Wade'', 410 U.S. 113 (1973),. was a landmark decision of the U.S. Supreme Court in which the Court ruled that the Constitution of the United States conferred the right to have an abortion. The decision struck down many federal and ...

'' ruling. Helms was also the Senate conservatives' leader on school prayer

School prayer, in the context of religious liberty, is state-sanctioned or mandatory prayer by students in public schools. Depending on the country and the type of school, state-sponsored prayer may be required, permitted, or prohibited. Countries ...

.sex education

Sex education, also known as sexual education, sexuality education or sex ed, is the instruction of issues relating to human sexuality, including emotional relations and responsibilities, human sexual anatomy, sexual activity, sexual reproduct ...

without written parental consent. In 1979, Helms and Democrat Patrick Leahy

Patrick Joseph Leahy (; born March 31, 1940) is an American politician and attorney who is the senior United States senator from Vermont and serves as the president pro tempore of the United States Senate. A member of the Democratic Party, L ...

supported a federal Taxpayer Bill of Rights.

He joined the Senate Foreign Relations Committee

The United States Senate Committee on Foreign Relations is a standing committee of the U.S. Senate charged with leading foreign-policy legislation and debate in the Senate. It is generally responsible for overseeing and funding foreign aid ...

, being one of four men critical of Carter who were new to the committee. Leader of the pro-Taiwan

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is a country in East Asia, at the junction of the East and South China Seas in the northwestern Pacific Ocean, with the People's Republic of China (PRC) to the northwest, Japan to the northe ...

congressional lobby, Helms demanded that the People's Republic of China reject the use of force against the Republic of China

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is a country in East Asia, at the junction of the East and South China Seas in the northwestern Pacific Ocean, with the People's Republic of China (PRC) to the northwest, Japan to the northea ...

, but, much to his shock, the Carter administration did not ask them to rule it out.

Helms also criticized the government over Zimbabwe Rhodesia

Zimbabwe Rhodesia (), alternatively known as Zimbabwe-Rhodesia, also informally known as Zimbabwe or Rhodesia, and sometimes as Rhobabwe, was a short-lived sovereign state that existed from 1 June to 12 December 1979. Zimbabwe Rhodesia was p ...

, leading support for the Internal Settlement

The Internal Settlement was an agreement which was signed on 3 March 1978 between Prime Minister of Rhodesia Ian Smith and the moderate African nationalist leaders comprising Bishop Abel Muzorewa, Ndabaningi Sithole and Senator Chief Jeremiah Ch ...

government under Abel Muzorewa

Abel Tendekayi Muzorewa (14 April 1925 – 8 April 2010), also commonly referred to as Bishop Muzorewa, was a Zimbabwean bishop and politician who served as the first and only Prime Minister of Zimbabwe Rhodesia from the Internal Settlement to ...

, and campaigned along with Samuel Hayakawa

Samuel Ichiye Hayakawa (July 18, 1906 – February 27, 1992) was a Canadian-born American academic and politician of Japanese ancestry. A professor of English, he served as president of San Francisco State University and then as U.S. Senator from ...

for the immediate lifting of sanctions on Muzorewa's government. Helms complained that it was inconsistent to lift sanctions on Uganda

}), is a landlocked country in East Africa. The country is bordered to the east by Kenya, to the north by South Sudan, to the west by the Democratic Republic of the Congo, to the south-west by Rwanda, and to the south by Tanzania. The south ...

immediately after Idi Amin

Idi Amin Dada Oumee (, ; 16 August 2003) was a Ugandan military officer and politician who served as the third president of Uganda from 1971 to 1979. He ruled as a military dictator and is considered one of the most brutal despots in modern w ...

's departure, but not Zimbabwe Rhodesia after Ian Smith

Ian Douglas Smith (8 April 1919 – 20 November 2007) was a Rhodesian politician, farmer, and fighter pilot who served as Prime Minister of Rhodesia (known as Southern Rhodesia until October 1964 and now known as Zimbabwe) from 1964 to ...

's. Helms hosted Muzorewa when he visited Washington and met with Carter in July 1979. He sent two aides to the Lancaster House Conference because he did not "trust the State Department on this issue",John Carbaugh

John is a common English name and surname:

* John (given name)

* John (surname)

John may also refer to:

New Testament

Works

* Gospel of John, a title often shortened to John

* First Epistle of John, often shortened to 1 John

* Second ...

was accused of encouraging Smith to "hang on" and take a harder line, implying that there was enough support in the US Senate to lift sanctions without a settlement.Ted Kennedy

Edward Moore Kennedy (February 22, 1932 – August 25, 2009) was an American lawyer and politician who served as a United States senator from Massachusetts for almost 47 years, from 1962 until his death in 2009. A member of the Democratic ...

accused Carter of conceding the construction of a new aircraft carrier in return for Helms's acquiescence on Zimbabwe Rhodesia, which both parties denied. Helms's support for lifting sanctions on Zimbabwe Rhodesia may have been grounded in North Carolina's tobacco traders, who would have been the main group benefiting from unilaterally lifting sanctions on tobacco-exporting Zimbabwe Rhodesia.

1980 presidential election

In 1979, Helms was touted as a potential contender for the Republican nomination

Presidential primaries have been held in the United States since 1912 to nominate the Republican presidential candidate.

1912

This was the first time that candidates were chosen through primaries. President William Taft ran to become the nomi ...

for the 1980 presidential election,running mate

A running mate is a person running together with another person on a joint ticket during an election. The term is most often used in reference to the person in the subordinate position (such as the vice presidential candidate running with a pres ...

for Reagan, and said he'd accept if he could "be his own man".George H. W. Bush

George Herbert Walker BushSince around 2000, he has been usually called George H. W. Bush, Bush Senior, Bush 41 or Bush the Elder to distinguish him from his eldest son, George W. Bush, who served as the 43rd president from 2001 to 2009; p ...

as his preferred candidate. At the convention, Helms toyed with the idea of running for vice-president despite Reagan's choice, but let it go in exchange for Bush's endorsing the party platform and allowing Helms to address the convention.Equal Rights Amendment

The Equal Rights Amendment (ERA) is a proposed amendment to the United States Constitution designed to guarantee equal legal rights for all American citizens regardless of sex. Proponents assert it would end legal distinctions between men an ...

.

In the fall of 1980, Helms proposed another bill denying the Supreme Court

A supreme court is the highest court within the hierarchy of courts in most legal jurisdictions. Other descriptions for such courts include court of last resort, apex court, and high (or final) court of appeal. Broadly speaking, the decisions of ...

jurisdiction over school prayer

School prayer, in the context of religious liberty, is state-sanctioned or mandatory prayer by students in public schools. Depending on the country and the type of school, state-sponsored prayer may be required, permitted, or prohibited. Countries ...

, but this found little support in committee. It was strongly opposed by mainline Protestant

The mainline Protestant churches (also called mainstream Protestant and sometimes oldline Protestant) are a group of Protestant denominations in the United States that contrast in history and practice with evangelical, fundamentalist, and chari ...

churches, and its counterpart was defeated in the House. Senators Helms and James A. McClure

James Albertus McClure (December 27, 1924 – February 26, 2011) was an American lawyer and politician from the state of Idaho, most notably serving as a Republican in the U.S. Senate for three terms.

Early life and education

McClure attende ...

blocked Ted Kennedy's comprehensive criminal code that did not relax federal firearms restrictions, inserted capital punishment procedures, and reinstated current statutory law on pornography

Pornography (often shortened to porn or porno) is the portrayal of sexual subject matter for the exclusive purpose of sexual arousal. Primarily intended for adults, , prostitution, and drug possession

The prohibition of drugs through sumptuary legislation or religious law is a common means of attempting to prevent the recreational use of certain intoxicating substances.

While some drugs are illegal to possess, many governments regulate th ...

.gold standard

A gold standard is a Backed currency, monetary system in which the standard economics, economic unit of account is based on a fixed quantity of gold. The gold standard was the basis for the international monetary system from the 1870s to the ...

, and successfully passed an amendment setting up a commission to look into gold-backed currency. After the presidential election, Helms and Strom Thurmond

James Strom Thurmond Sr. (December 5, 1902June 26, 2003) was an American politician who represented South Carolina in the United States Senate from 1954 to 2003. Prior to his 48 years as a senator, he served as the 103rd governor of South Caro ...

sponsored a Senate amendment to a Department of Justice

A justice ministry, ministry of justice, or department of justice is a ministry or other government agency in charge of the administration of justice. The ministry or department is often headed by a minister of justice (minister for justice in a ...

appropriations bill denying the department the power to participate in busing, due to objections over federal involvement, but, although passed by Congress, was vetoed by a lame duck Carter. Helms pledged to introduce an even stronger anti-busing bill as soon as Reagan took office.

Republicans take the Senate

In the 1980 Senate election, the Republicans unexpectedly won a majority,John Porter East

John Porter East (May 5, 1931 – June 29, 1986) was a Republican U.S. senator from the state of North Carolina from 1981 until his suicide in 1986.

A paraplegic since 1955 because of polio, East was a professor of political science at East Caro ...

, a social conservative and a Helms protégé soon dubbed "Helms on Wheels", winning the other North Carolina seat. Howard Baker

Howard Henry Baker Jr. (November 15, 1925 June 26, 2014) was an American politician and diplomat who served as a United States Senate, United States Senator from Tennessee from 1967 to 1985. During his tenure, he rose to the rank of Senate Min ...

was set to become Majority Leader

In U.S. politics (as well as in some other countries utilizing the presidential system), the majority floor leader is a partisan position in a legislative body. , but conservatives, angered by Baker's support for the Panama treaty, SALT II

The Strategic Arms Limitation Talks (SALT) were two rounds of bilateral conferences and corresponding international treaties involving the United States and the Soviet Union. The Cold War superpowers dealt with arms control in two rounds o ...

, and the Equal Rights Amendment, had sought to replace him with Helms until Reagan gave Baker his backing.Charles H. Percy

Charles Harting Percy (September 27, 1919 – September 17, 2011) was an American businessman and politician. He was president of the Bell & Howell Corporation from 1949 to 1964, and served as a Republican U.S. senator from Illinois from 1967 ...

,Alexander Haig

Alexander Meigs Haig Jr. (; December 2, 1924February 20, 2010) was United States Secretary of State under President Ronald Reagan and White House Chief of Staff under Presidents Richard Nixon and Gerald Ford. Prior to and in between these cab ...

,Chester Crocker

Chester Arthur Crocker (born October 29, 1941) is an American diplomat and scholar who served as Assistant Secretary of State for African Affairs from June 9, 1981, to April 21, 1989, in the Reagan administration. Crocker, architect of the U.S. p ...

,John J. Louis Jr.

John Jeffry Louis Jr. (June 10, 1925 – February 15, 1995) was an American businessman and diplomat. He served as the United States Ambassador to the United Kingdom.

Early life

John J. Louis Jr., was born in Evanston, Illinois to Chicago adverti ...

, and Lawrence Eagleburger

Lawrence Sidney Eagleburger (August 1, 1930 – June 4, 2011) was an American statesman and career diplomat, who served briefly as the Secretary of State under President George H. W. Bush from December 1992 to January 1993, one of the shortest t ...

,Caspar Weinberger

Caspar Willard Weinberger (August 18, 1917 – March 28, 2006) was an American statesman and businessman. As a prominent Republican, he served in a variety of state and federal positions for three decades, including chairman of the Californ ...

, Donald Regan

Donald Thomas Regan (December 21, 1918 – June 10, 2003) was the 66th United States Secretary of the Treasury from 1981 to 1985 and the White House Chief of Staff from 1985 to 1987 under Ronald Reagan. In the Reagan administration, he advoca ...

,Frank Carlucci

Frank Charles Carlucci III ( ; October 18, 1930 – June 3, 2018) was an American politician and diplomat who served as the United States Secretary of Defense from 1987 to 1989 in the administration of President Ronald Reagan. He was the f ...

.Eugene V. Rostow

Eugene Victor Rostow (August 25, 1913 – November 25, 2002) was an American legal scholar and public servant. He was Dean of Yale Law School and served as Under Secretary of State for Political Affairs under President Lyndon B. Johnson. In ...

.

Food stamp program

An opponent of the Food Stamp Program

In the United States, the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), formerly known as the Food Stamp Program, is a federal program that provides food-purchasing assistance for low- and no-income people. It is a federal aid program, ad ...

, Helms had already voted to reduce its scope, and was determined to follow this through as Agriculture Committee chairman.workfare

Workfare is a governmental plan under which welfare recipients are required to accept public-service jobs or to participate in job training. Many countries around the world have adopted workfare (sometimes implemented as "work-first" policies) to ...

. He then proposed that food stamp benefits be dropped by $11.50 per month per child for each youngster enrolled in the school lunch program. He maintained that "free lunches" duplicate food stamps. The outcry against his proposal was so strong that he was compelled to back down. Helms also challenged fraud in the food stamp program. He said that the public had "grown legitimately resentful about the abuses which they themselves have observed".

As a freshman lawmaker in 1973, Helms tried to reverse the 1968 congressional vote which had permitted workers on strike to qualify for food stamps. Though he failed to gain reversal, his position drew the support of future Minority and Majority Leader Howard Baker

Howard Henry Baker Jr. (November 15, 1925 June 26, 2014) was an American politician and diplomat who served as a United States Senate, United States Senator from Tennessee from 1967 to 1985. During his tenure, he rose to the rank of Senate Min ...

of Tennessee

Tennessee ( , ), officially the State of Tennessee, is a landlocked state in the Southeastern region of the United States. Tennessee is the 36th-largest by area and the 15th-most populous of the 50 states. It is bordered by Kentucky to ...

and twelve Senate Democrats. Helms's position was upheld in 1988, when the United States Supreme Court

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all U.S. federal court cases, and over state court cases that involve a point ...

decreed 5–3 that a law denying food stamps to strikers was constitutional unless the worker otherwise qualified for food stamps before going on strike. Justice Byron White

Byron "Whizzer" Raymond White (June 8, 1917 April 15, 2002) was an American professional football player and jurist who served as an associate justice of the U.S. Supreme Court from 1962 until his retirement in 1993.

Born and raised in Colora ...

said that the government must maintain neutrality in labor dispute and not subsidize strikers.

As the Agriculture Committee chairman, Helms proposed repeal of the 1977 amendment which had deleted the purchase requirement for food stamps. With that position he ran afoul of fellow Republican Bob Dole

Robert Joseph Dole (July 22, 1923 – December 5, 2021) was an American politician and attorney who represented Kansas in the United States Senate from 1969 to 1996. He was the Republican Leader of the Senate during the final 11 years of his ...

, who claimed that the purchase requirement had contributed to fraud and administrative difficulties in the program. Helms cited a Congressional Budget Office report which showed that 75 percent of the increase in stamp usage had occurred since the purchase requirement was dropped. When Helms's ally, Steve Symms

Steven Douglas Symms (born April 23, 1938) is an American politician and lobbyist who served as a four-term congressman (1973–81) and two-term U.S. Senator (1981–93), representing Idaho. He is a partner at Parry, Romani, DeConcini & Symms, a ...

of Idaho

Idaho ( ) is a state in the Pacific Northwest region of the Western United States. To the north, it shares a small portion of the Canada–United States border with the province of British Columbia. It borders the states of Montana and W ...

, proposed to reinstitute the purchase requirement, the motion was defeated, 33–66.

The Helms bloc also failed to secure other limits to the program, including a motion to delete alcohol and drug residential treatment patients from benefits. House and Senate conferees dropped a Helms-backed provision requiring families disqualified from the program to repay double the amount of any benefits received improperly. House Democratic Whip Tom Foley

Thomas Stephen Foley (March 6, 1929 – October 18, 2013) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 49th speaker of the United States House of Representatives from 1989 to 1995. A member of the Democratic Party, Foley represent ...

of Washington

Washington commonly refers to:

* Washington (state), United States

* Washington, D.C., the capital of the United States

** A metonym for the federal government of the United States

** Washington metropolitan area, the metropolitan area centered o ...

insisted that such a penalty would violate the Fifth Amendment rights to due process

Due process of law is application by state of all legal rules and principles pertaining to the case so all legal rights that are owed to the person are respected. Due process balances the power of law of the land and protects the individual pe ...

. Instead families repay the actual amount of improperly obtained benefits.

Economic policies

Helms supported the gold standard

A gold standard is a Backed currency, monetary system in which the standard economics, economic unit of account is based on a fixed quantity of gold. The gold standard was the basis for the international monetary system from the 1870s to the ...

through his role as the Agriculture Committee chairman, which exercises wide powers over commodity markets.trade war

A trade war is an economic conflict often resulting from extreme protectionism in which states raise or create tariffs or other trade barriers against each other in response to trade barriers created by the other party. If tariffs are the exclu ...

with the European Union

The European Union (EU) is a supranational political and economic union of member states that are located primarily in Europe. The union has a total area of and an estimated total population of about 447million. The EU has often been ...

. Helms heavily opposed cutting food aid to Poland after martial law was declared, and called for the end of grain exports to (and arms limitation talks with) the Soviet Union instead.

In 1982, Helms authored a bill to introduce a federal flat tax

A flat tax (short for flat-rate tax) is a tax with a single rate on the taxable amount, after accounting for any deductions or exemptions from the tax base. It is not necessarily a fully proportional tax. Implementations are often progressiv ...

of 10% with a personal allowance

In the UK tax system, personal allowance is the threshold above which income tax is levied on an individual's income. A person who receives less than their own personal allowance in taxable income (such as earnings and some benefits) in a given ...

of $2,000. He voted against the 1983 budget: the only conservative Senator to have done so, and was a leading voice for a balanced budget amendment

A balanced budget amendment is a constitutional rule requiring that a state cannot spend more than its income. It requires a balance between the projected receipts and expenditures of the government.

Balanced-budget provisions have been added ...

. With Charlie Rose

Charles Peete Rose Jr. (born January 5, 1942) is an American former television journalist and talk show host. From 1991 to 2017, he was the host and executive producer of the talk show '' Charlie Rose'' on PBS and Bloomberg LP.

Rose also co- ...