Senator George McGovern on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

George Stanley McGovern (July 19, 1922 – October 21, 2012) was an American politician, diplomat, and historian who was a

When George was about three years old, the family moved to Calgary for a while to be near Frances's ailing mother, and he formed memories of events such as the

When George was about three years old, the family moved to Calgary for a while to be near Frances's ailing mother, and he formed memories of events such as the

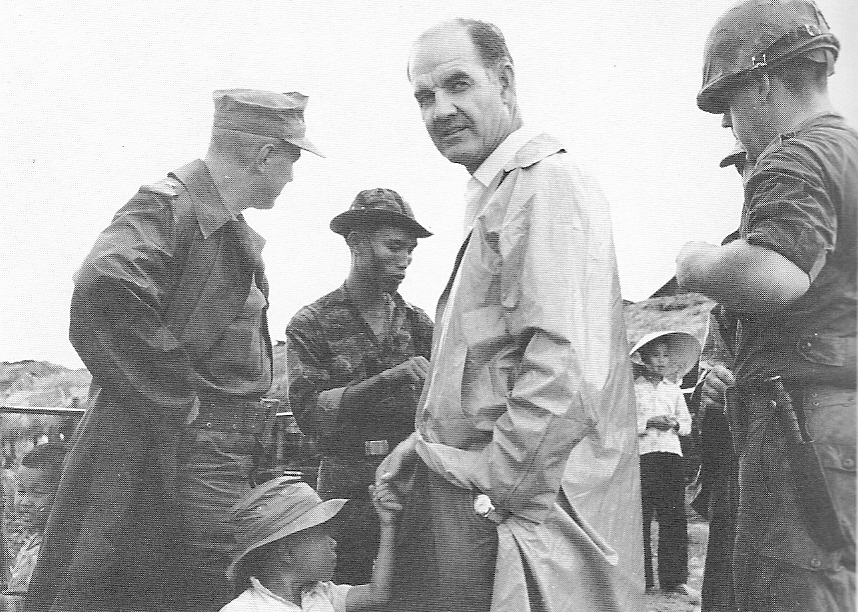

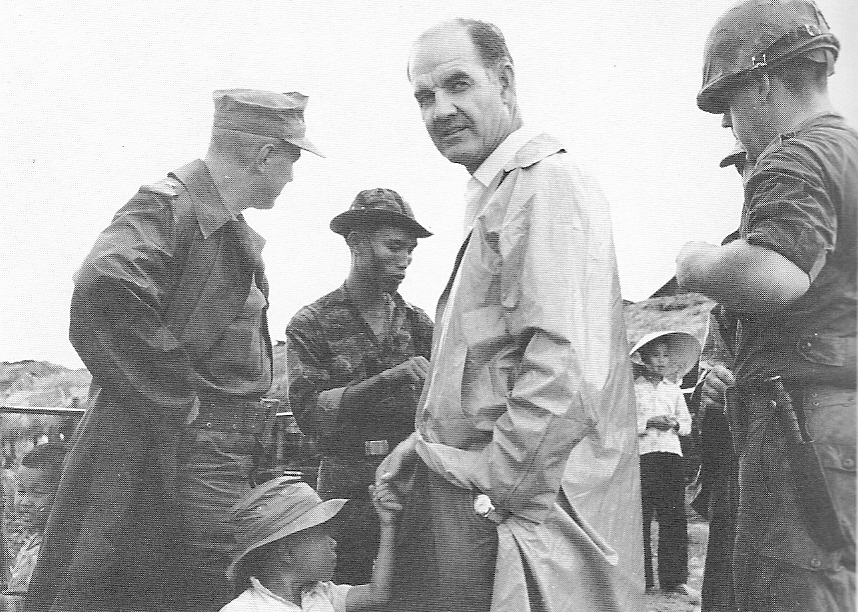

Having relinquished his House seat to run for the Senate, McGovern was available for a position in the new

Having relinquished his House seat to run for the Senate, McGovern was available for a position in the new

In a speech on the Senate floor in September 1963, McGovern became the first member to challenge the growing U.S. military involvement in Vietnam.Weil, ''The Long Shot'', pp. 16–17. Bothered by the

In a speech on the Senate floor in September 1963, McGovern became the first member to challenge the growing U.S. military involvement in Vietnam.Weil, ''The Long Shot'', pp. 16–17. Bothered by the

The general election campaign did not go well for McGovern. Nixon did little campaigning; he was buoyed by the success of his visit to China and arms-control-signing summit meeting in the Soviet Union earlier that year, and shortly before the election

The general election campaign did not go well for McGovern. Nixon did little campaigning; he was buoyed by the success of his visit to China and arms-control-signing summit meeting in the Soviet Union earlier that year, and shortly before the election  By the final week of the campaign, McGovern knew he was going to lose. While he was appearing in

By the final week of the campaign, McGovern knew he was going to lose. While he was appearing in

After this loss, McGovern remained in the Senate. He was scarred by the enormous defeat,Miroff, ''The Liberals' Moment'', p. 293. and his wife, Eleanor, took it even worse; during the winter of 1972–1973, the couple seriously considered moving to England. His allies were replaced in positions of power within the Democratic Party leadership, and the McGoverns did not get publicly introduced at party affairs they attended. On January 20, 1973, a few hours after Richard Nixon was re-inaugurated, McGovern gave a speech at the

After this loss, McGovern remained in the Senate. He was scarred by the enormous defeat,Miroff, ''The Liberals' Moment'', p. 293. and his wife, Eleanor, took it even worse; during the winter of 1972–1973, the couple seriously considered moving to England. His allies were replaced in positions of power within the Democratic Party leadership, and the McGoverns did not get publicly introduced at party affairs they attended. On January 20, 1973, a few hours after Richard Nixon was re-inaugurated, McGovern gave a speech at the

McGovern did not mourn leaving the Senate. Although being rejected by his own state stung, intellectually he could accept that South Dakotans wanted a more conservative representative; he and Eleanor felt out of touch with the country and in some ways liberated by the loss. Nevertheless, he refused to believe that

McGovern did not mourn leaving the Senate. Although being rejected by his own state stung, intellectually he could accept that South Dakotans wanted a more conservative representative; he and Eleanor felt out of touch with the country and in some ways liberated by the loss. Nevertheless, he refused to believe that

Owing to his resounding loss to Nixon in the 1972 election and the causes behind it, "McGovernism" became a label that a generation of Democratic politicians tried to avoid. In 1992, nationally syndicated ''

Owing to his resounding loss to Nixon in the 1972 election and the causes behind it, "McGovernism" became a label that a generation of Democratic politicians tried to avoid. In 1992, nationally syndicated ''

* Watson, Robert P. (ed.), ''George McGovern: A Political Life, A Political Legacy'', South Dakota State Historical Society Press, 2004. .

* Wayne, Stephen J., ''The Road to the White House 2008: The Politics of Presidential Elections'' (8th edition), Boston: Thomson Wadsworth, 2008. .

* Weil, Gordon L., ''The Long Shot: George McGovern Runs for President'', New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1973. .

* White, Theodore H., ''The Making of the President 1968'', Antheneum Publishers, 1969.

* White, Theodore H., ''The Making of the President 1972'', Antheneum Publishers, 1973. .

* Witcover, Jules, ''Party of the People: A History of the Democrats'', New York: Random House, 2003. .

* Watson, Robert P. (ed.), ''George McGovern: A Political Life, A Political Legacy'', South Dakota State Historical Society Press, 2004. .

* Wayne, Stephen J., ''The Road to the White House 2008: The Politics of Presidential Elections'' (8th edition), Boston: Thomson Wadsworth, 2008. .

* Weil, Gordon L., ''The Long Shot: George McGovern Runs for President'', New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1973. .

* White, Theodore H., ''The Making of the President 1968'', Antheneum Publishers, 1969.

* White, Theodore H., ''The Making of the President 1972'', Antheneum Publishers, 1973. .

* Witcover, Jules, ''Party of the People: A History of the Democrats'', New York: Random House, 2003. .

*

*

*

*

"George McGovern, Presidential Contender"

from

George McGovern – Goodwill Ambassador at World Food Programme

McGovern-Dole International Food for Education and Child Nutrition Program

George and Eleanor McGovern Center for Leadership and Public Service at Dakota Wesleyan University

McGovern Library at Dakota Wesleyan University

* ttp://arks.princeton.edu/ark:/88435/f7623c58x George S. McGovern Papers at the Seeley G. Mudd Manuscript Library, Princeton University

McGovern nomination acceptance speech, July 10, 1972

George McGovern FBI files, Part 1

George McGovern FBI files, Part 2

with George McGovern by Stephen McKiernan, Binghamton University Libraries Center for the Study of the 1960s, August 13, 2010

Recordings of George McGovern presidential campaign radio spots, 1972–1974, Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library, Emory University

, - , - , - , - , - , - , - {{DEFAULTSORT:McGovern, George 1922 births 2012 deaths 20th-century American biographers 21st-century American historians 21st-century American male writers American anti–Vietnam War activists American autobiographers American male non-fiction writers American people of Canadian descent American people of Irish descent American political writers Candidates in the 1968 United States presidential election Candidates in the 1972 United States presidential election Candidates in the 1984 United States presidential election Dakota Wesleyan University alumni Dakota Wesleyan University faculty Democratic Party (United States) presidential nominees Democratic Party United States senators from South Dakota Democratic Party members of the United States House of Representatives from South Dakota Military personnel from Sioux Falls, South Dakota Northwestern University alumni People from Bon Homme County, South Dakota People from Mitchell, South Dakota Politicians from Sioux Falls, South Dakota Presidential Medal of Freedom recipients Recipients of the Air Medal Recipients of the Distinguished Flying Cross (United States) Representatives of the United States to the United Nations Agencies for Food and Agriculture United States Army Air Forces bomber pilots of World War II United States Army Air Forces officers Writers from South Dakota Methodists from South Dakota Liberalism in the United States 20th-century United States senators 20th-century members of the United States House of Representatives

U.S. representative

The United States House of Representatives is a chamber of the bicameral United States Congress; it is the lower house, with the U.S. Senate being the upper house. Together, the House and Senate have the authority under Article One of th ...

and three-term U.S. senator

The United States Senate is a chamber of the bicameral United States Congress; it is the upper house, with the U.S. House of Representatives being the lower house. Together, the Senate and House have the authority under Article One of the ...

from South Dakota

South Dakota (; Sioux language, Sioux: , ) is a U.S. state, state in the West North Central states, North Central region of the United States. It is also part of the Great Plains. South Dakota is named after the Dakota people, Dakota Sioux ...

, and the Democratic Party presidential nominee in the 1972 U.S. presidential election.

McGovern grew up in Mitchell, South Dakota

Mitchell is a city in and the county seat of Davison County, South Dakota, United States. The population was 15,660 at the 2020 United States Census, 2020 census making it the List of cities in South Dakota, sixth most populous city in South Dako ...

, where he became a renowned debater. He volunteered for the U.S. Army Air Forces upon the country's entry into World War II. As a B-24 Liberator

The Consolidated B-24 Liberator is an American heavy bomber, designed by Consolidated Aircraft of San Diego, California. It was known within the company as the Model 32, and some initial production aircraft were laid down as export models desi ...

pilot, he flew 35 missions over German-occupied Europe

German-occupied Europe, or Nazi-occupied Europe, refers to the sovereign countries of Europe which were wholly or partly military occupation, militarily occupied and civil-occupied, including puppet states, by the (armed forces) and the governmen ...

from a base in Italy. Among the medals he received was a Distinguished Flying Cross for making a hazardous emergency landing of his damaged plane and saving his crew. After the war, he earned degrees from Dakota Wesleyan University

Dakota Wesleyan University (DWU) is a private Methodist university in Mitchell, South Dakota. It was founded in 1885 and is affiliated with the United Methodist Church. The student body averages slightly fewer than 800 students. The campus of t ...

and Northwestern University

Northwestern University (NU) is a Private university, private research university in Evanston, Illinois, United States. Established in 1851 to serve the historic Northwest Territory, it is the oldest University charter, chartered university in ...

, culminating in a PhD, and served as a history professor. He was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives in 1956 and re-elected in 1958. After a failed bid for the U.S. Senate in 1960, he was a successful candidate in 1962.

As a senator, McGovern was an example of modern American liberalism

Modern liberalism, often referred to simply as liberalism, is the dominant version of liberalism in the United States. It combines ideas of civil liberty and equality with support for social justice and a mixed economy. Modern liberalism is o ...

. He became most known for his outspoken opposition to the growing U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War

The Vietnam War (1 November 1955 – 30 April 1975) was an armed conflict in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia fought between North Vietnam (Democratic Republic of Vietnam) and South Vietnam (Republic of Vietnam) and their allies. North Vietnam w ...

. He staged a brief nomination run in the 1968 U.S. presidential election as a stand-in for the assassinated Robert F. Kennedy

Robert Francis Kennedy (November 20, 1925 – June 6, 1968), also known as RFK, was an American politician and lawyer. He served as the 64th United States attorney general from January 1961 to September 1964, and as a U.S. senator from New Yo ...

. The subsequent McGovern–Fraser Commission

The McGovern–Fraser Commission, formally known as Commission on Party Structure and Delegate Selection,Kamarck, Elaine C. (2009). Primary Politics: How Presidential Candidates Have Shaped the Modern Nominating System'. Washington, DC: Brookings I ...

fundamentally altered the presidential nominating process, by increasing the number of caucus

A caucus is a group or meeting of supporters or members of a specific political party or movement. The exact definition varies between different countries and political cultures.

The term originated in the United States, where it can refer to ...

es and primaries

Primary elections or primaries are elections held to determine which candidates will run in an upcoming general election. In a partisan primary, a political party selects a candidate. Depending on the state and/or party, there may be an "open pri ...

and reducing the influence of party insiders. The McGovern–Hatfield Amendment sought to end the Vietnam War by legislative means but was defeated in 1970 and 1971. McGovern's long-shot, grassroots-based 1972 presidential campaign found triumph in gaining the Democratic nomination but left the party split ideologically, and the failed vice-presidential pick of Thomas Eagleton

Thomas Francis Eagleton (September 4, 1929 – March 4, 2007) was an American lawyer who served as a United States senator from Missouri from 1968 to 1987. He was briefly the Democratic vice presidential nominee under George McGovern in 1972. H ...

undermined McGovern's credibility. In the general election, McGovern lost to incumbent Richard Nixon

Richard Milhous Nixon (January 9, 1913April 22, 1994) was the 37th president of the United States, serving from 1969 until Resignation of Richard Nixon, his resignation in 1974. A member of the Republican Party (United States), Republican ...

in one of the biggest landslides

Landslides, also known as landslips, rockslips or rockslides, are several forms of mass wasting that may include a wide range of ground movements, such as rockfalls, mudflows, shallow or deep-seated slope failures and debris flows. Landslide ...

in U.S. electoral history. Although re-elected to the Senate in 1968 and 1974, McGovern was defeated in his bid for a fourth term in 1980.

Beginning with his experiences in war-torn Italy and continuing throughout his career, McGovern was involved in issues related to agriculture, food, nutrition, and hunger. As the first director of the Food for Peace

Since the 1950s, in different administrative and organizational forms, the United States' Food for Peace program has used America's agricultural surpluses to provide food assistance around the world, broaden international trade, and advance U.S. ...

program in 1961, McGovern oversaw the distribution of U.S. surpluses to the needy abroad and was instrumental in the creation of the United Nations-run World Food Programme

The World Food Programme (WFP) is an international organization within the United Nations that provides food assistance worldwide. It is the world's largest humanitarian organization and the leading provider of school meals. Founded in 1961 ...

. As sole chairman of the Senate Select Committee on Nutrition and Human Needs from 1968 to 1977, McGovern publicized the problem of hunger within the United States and issued the "McGovern Report", which led to a new set of nutritional guidelines for Americans. McGovern later served as U.S. ambassador to the United Nations Agencies for Food and Agriculture from 1998 to 2001 and was appointed the first UN global ambassador on world hunger by the World Food Programme in 2001. The McGovern–Dole International Food for Education and Child Nutrition Program has provided school meals for millions of children in dozens of countries since 2000 and resulted in McGovern's being named World Food Prize

The World Food Prize is an international award recognizing the achievements of individuals who have advanced human development by improving the quality, quantity, or availability of food in the world. Conceived by Nobel Peace Prize laureate No ...

co‑laureate in 2008.

Early years and education

McGovern was born in the 600‑person farming community ofAvon, South Dakota

Avon is a city in Bon Homme County, South Dakota, United States. The population was 586 at the 2020 census.

History

Avon was founded in 1879. The community owes its name to Avon, New York, the hometown of an early postmaster. Construction of t ...

.''Current Year Biography 1967'', p. 265. His father, the Rev. Joseph C. McGovern, born in 1868, was pastor of the local Wesleyan Methodist Church there. Joseph, the son of an alcoholic who had immigrated from Ireland, had grown up in several states, working in coal mines from the age of nine and parentless from the age of thirteen. He had been a professional baseball player in the minor leagues

Minor leagues are professional sports leagues which are not regarded as the premier leagues in those sports. Minor league teams tend to play in smaller, less elaborate venues, often competing in smaller cities/markets. This term is used in Nort ...

, but had given it up due to his teammates' heavy drinking, gambling, and womanizing, and entered the seminary instead.Ambrose, ''The Wild Blue'', pp. 27, 29. George's mother was the former Frances McLean, born and initially raised in Ontario

Ontario is the southernmost Provinces and territories of Canada, province of Canada. Located in Central Canada, Ontario is the Population of Canada by province and territory, country's most populous province. As of the 2021 Canadian census, it ...

, Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its Provinces and territories of Canada, ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, making it the world's List of coun ...

; her family had later moved to Calgary

Calgary () is a major city in the Canadian province of Alberta. As of 2021, the city proper had a population of 1,306,784 and a metropolitan population of 1,481,806 making it the third-largest city and fifth-largest metropolitan area in C ...

, Alberta

Alberta is a Provinces and territories of Canada, province in Canada. It is a part of Western Canada and is one of the three Canadian Prairies, prairie provinces. Alberta is bordered by British Columbia to its west, Saskatchewan to its east, t ...

, and then she came to South Dakota looking for work as a secretary. George was the second oldest of four children. Joseph McGovern's salary never reached $100 per month, and he often received compensation in the form of potatoes, cabbages, or other food items.Ambrose, ''The Wild Blue'', p. 30. Joseph and Frances McGovern were both firm Republicans

Republican can refer to:

Political ideology

* An advocate of a republic, a type of government that is not a monarchy or dictatorship, and is usually associated with the rule of law.

** Republicanism, the ideology in support of republics or agains ...

, but were not politically active or doctrinaire.

When George was about three years old, the family moved to Calgary for a while to be near Frances's ailing mother, and he formed memories of events such as the

When George was about three years old, the family moved to Calgary for a while to be near Frances's ailing mother, and he formed memories of events such as the Calgary Stampede

The Calgary Stampede is an annual rodeo, fair, exhibition, and festival held every July in Calgary, Alberta, Canada. The ten-day event, which bills itself as "The Greatest Outdoor Show on Earth", attracts over one million visitors per year a ...

. When George was six, the family returned to the United States and moved to Mitchell, South Dakota

Mitchell is a city in and the county seat of Davison County, South Dakota, United States. The population was 15,660 at the 2020 United States Census, 2020 census making it the List of cities in South Dakota, sixth most populous city in South Dako ...

, a community of 12,000. McGovern attended public schools there and was an average student. He was painfully shy as a child and was afraid to speak in class during first grade. His only reproachable behavior was going to see movies, which were among the worldly amusements forbidden to good Wesleyan Methodists. Otherwise he had a normal childhood marked by visits to the renowned Mitchell Corn Palace

The Corn Palace, commonly advertised as The World's Only Corn Palace and the Mitchell Corn Palace, is a multi-purpose arena/facility located in Mitchell, South Dakota, United States. The Moorish Revival building is decorated with crop art; the m ...

and what he later termed "a sense of belonging to a particular place and knowing your part in it". He would long remember the Dust Bowl

The Dust Bowl was a period of severe dust storms that greatly damaged the ecology and agriculture of the American and Canadian prairies during the 1930s. The phenomenon was caused by a combination of natural factors (severe drought) and hum ...

storms and grasshopper plagues that swept the prairie states during the Great Depression

The Great Depression was a severe global economic downturn from 1929 to 1939. The period was characterized by high rates of unemployment and poverty, drastic reductions in industrial production and international trade, and widespread bank and ...

. The McGovern family lived on the edge of the poverty line

The poverty threshold, poverty limit, poverty line, or breadline is the minimum level of income deemed adequate in a particular country. The poverty line is usually calculated by estimating the total cost of one year's worth of necessities for ...

for much of the 1920s and 1930s. Growing up so close to privation gave young George a lifelong sympathy for underpaid workers and struggling farmers. He was influenced by the currents of populism

Populism is a essentially contested concept, contested concept used to refer to a variety of political stances that emphasize the idea of the "common people" and often position this group in opposition to a perceived elite. It is frequently a ...

and agrarian unrest, as well as the "practical divinity" teachings of cleric John Wesley

John Wesley ( ; 2 March 1791) was an English cleric, Christian theology, theologian, and Evangelism, evangelist who was a principal leader of a Christian revival, revival movement within the Church of England known as Methodism. The societies ...

that sought to fight poverty, injustice, and ignorance.Mann, ''A Grand Delusion'', pp. 292–293.

McGovern attended Mitchell High School, where he was a solid but unspectacular member of the track team. A turning point came when his tenth-grade English teacher recommended him to the debate team, where he became quite active. His high-school debate coach, a history teacher who capitalized on McGovern's interest in that subject, proved to be a great influence in his life, and McGovern spent many hours honing his meticulous, if colorless, forensic style.Anson, ''McGovern'', pp. 27–31. McGovern and his debating partner won events in his area and gained renown in a state where debating was passionately followed by the general public. Debate changed McGovern's life, giving him a chance to explore ideas to their logical end, broadening his perspective, and instilling a sense of personal and social confidence. He graduated in 1940 in the top ten percent of his class.

McGovern enrolled at small Dakota Wesleyan University

Dakota Wesleyan University (DWU) is a private Methodist university in Mitchell, South Dakota. It was founded in 1885 and is affiliated with the United Methodist Church. The student body averages slightly fewer than 800 students. The campus of t ...

in Mitchell and became a star student there.Ambrose, ''The Wild Blue'', p. 46. He supplemented a forensic scholarship by working a variety of odd jobs.Anson, ''McGovern'', pp. 32–33. With World War II under way overseas and feeling insecure about his own courage, McGovern took flying lessons in an Aeronca aircraft

Aeronca, contracted from Aeronautical Corporation of America, located in Middletown, Ohio, is a US manufacturer of engine components and airframe structures for commercial aviation and the defense industry, and a former aircraft manufacturer. ...

and received a pilot's license through the government's Civilian Pilot Training Program

The Civilian Pilot Training Program (CPTP) was a flight training program (1938–1944) sponsored by the United States government with the stated purpose of increasing the number of civilian pilots, though having a clear impact on military prepare ...

. McGovern recalled: "Frankly, I was scared to death on that first solo flight. But when I walked away from it, I had an enormous feeling of satisfaction that I had taken the thing off the ground and landed it without tearing the wings off." In late 1940 or early 1941, McGovern had pre-marital sex with an acquaintance that resulted in her giving birth to a daughter during 1941, although this did not become public knowledge during his lifetime. In April 1941 McGovern began dating fellow student Eleanor Stegeberg, who had grown up in Woonsocket, South Dakota

Woonsocket is a city in Sanborn County, South Dakota, United States. The population was 631 at the 2020 United States Census, 2020 census. It is the county seat of Sanborn County.

History

Woonsocket was developed in 1883 as a railroad town becau ...

.Ambrose, ''The Wild Blue'', p. 45. They had first encountered each other during a high school debate in which Eleanor and her twin sister Ila defeated McGovern and his partner.

McGovern was listening to a radio broadcast of the New York Philharmonic Orchestra

The New York Philharmonic is an American symphony orchestra based in New York City. Known officially as the ''Philharmonic-Symphony Society of New York, Inc.'', and globally known as the ''New York Philharmonic Orchestra'' (NYPO) or the ''New Yo ...

for a sophomore-year music appreciation class when he heard the news of the December 7, 1941, attack on Pearl Harbor

The attack on Pearl HarborAlso known as the Battle of Pearl Harbor was a surprise military strike by the Empire of Japan on the United States Pacific Fleet at Naval Station Pearl Harbor, its naval base at Pearl Harbor on Oahu, Territory of ...

.Ambrose, ''The Wild Blue'', pp. 42–43. In January 1942 he drove with nine other students to Omaha, Nebraska

Omaha ( ) is the List of cities in Nebraska, most populous city in the U.S. state of Nebraska. It is located in the Midwestern United States along the Missouri River, about north of the mouth of the Platte River. The nation's List of United S ...

, and volunteered to join the United States Army Air Forces

The United States Army Air Forces (USAAF or AAF) was the major land-based aerial warfare service component of the United States Army and ''de facto'' aerial warfare service branch of the United States during and immediately after World War II ...

. The military accepted him, but they did not yet have enough airfields, aircraft, or instructors to start training all the volunteers, so McGovern stayed at Dakota Wesleyan. George and Eleanor became engaged, but initially decided not to marry until the war was over. During his sophomore year, McGovern won the statewide intercollegiate South Dakota Peace Oratory Contest with a speech called "My Brother's Keeper", which was later selected by the National Council of Churches

The National Council of the Churches of Christ in the USA, usually identified as the National Council of Churches (NCC), is a left-wing progressive activist group and the largest ecumenical body in the United States. NCC is an ecumenical partners ...

as one of the nation's twelve best orations of 1942. Smart, handsome, and well liked, McGovern was elected president of his sophomore class and voted "Glamour Boy" during his junior year. In February 1943, during his junior year, he and a partner won a regional debate tournament at North Dakota State University

North Dakota State University (NDSU, formally North Dakota State University of Agriculture and Applied Sciences) is a public university, public Land-grant university, land-grant research university in Fargo, North Dakota, United States. It was ...

that featured competitors from thirty-two schools across a dozen states; upon his return to campus, he discovered that the Army had finally called him up.Knock, "Come Home America", p. 87.

Military service

Groundschool and trainers

Soon thereafter McGovern was sworn in as aprivate

Private or privates may refer to:

Music

* "In Private", by Dusty Springfield from the 1990 album ''Reputation''

* Private (band), a Denmark-based band

* "Private" (Ryōko Hirosue song), from the 1999 album ''Private'', written and also recorded ...

at Fort Snelling

Fort Snelling is a former military fortification and National Historic Landmark in the U.S. state of Minnesota on the bluffs overlooking the confluence of the Minnesota and Mississippi Rivers. The military site was initially named Fort Saint An ...

in Minnesota

Minnesota ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Upper Midwestern region of the United States. It is bordered by the Canadian provinces of Manitoba and Ontario to the north and east and by the U.S. states of Wisconsin to the east, Iowa to the so ...

.Ambrose, ''The Wild Blue'', p. 49. He spent a month at Jefferson Barracks Military Post

The Jefferson Barracks Military Post is located on the Mississippi River at Lemay, Missouri, south of St. Louis. It was an important and active U.S. Army installation from 1826 through 1946. It is the oldest operating U.S. military installat ...

in Missouri

Missouri (''see #Etymology and pronunciation, pronunciation'') is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. Ranking List of U.S. states and territories by area, 21st in land area, it border ...

and then five months at Southern Illinois Normal University in Carbondale, Illinois

Carbondale is a city in Jackson County, Illinois, United States, within the Southern Illinois region informally known as "Little Egypt". As of the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, the city had a population of 25,083, making it the most po ...

, for ground school training. McGovern later maintained that both the academic work and physical training were the toughest he ever experienced.Ambrose, ''The Wild Blue'', pp. 54, 56–57. He spent two months at a base in San Antonio, Texas

San Antonio ( ; Spanish for "Anthony of Padua, Saint Anthony") is a city in the U.S. state of Texas and the most populous city in Greater San Antonio. San Antonio is the List of Texas metropolitan areas, third-largest metropolitan area in Texa ...

, and then went to Hatbox Field

Hatbox Field is a closed airfield located within city limits, two nautical miles (3.7 km) west of central Muskogee, a city in Muskogee County, Oklahoma, United States. It was opened sometime in the early 1920s and was closed in 2000. It ...

in Muskogee, Oklahoma

Muskogee () is the 13th-largest city in Oklahoma and is the county seat of Muskogee County, Oklahoma, Muskogee County. Home to Bacone College, it lies approximately southeast of Tulsa, Oklahoma, Tulsa. The population of the city was 36,878 as of ...

, for basic flying school, training in a single-engined PT‑19. McGovern married Eleanor Stegeberg on October 31, 1943, during a three-day leave (lonely and in love, the couple had decided to not wait any longer).Ambrose, ''The Wild Blue'', pp. 65–66. His father presided over the ceremony at the Methodist church in Woonsocket.

After three months in Muskogee, McGovern went to Coffeyville Army Airfield in Kansas

Kansas ( ) is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. It borders Nebraska to the north; Missouri to the east; Oklahoma to the south; and Colorado to the west. Kansas is named a ...

for a further three months of training on the BT‑13.Ambrose, ''The Wild Blue'', pp. 68–70, 73–74. Around April 1944, McGovern went on to advanced flying school at Pampa Army Airfield in Texas

Texas ( , ; or ) is the most populous U.S. state, state in the South Central United States, South Central region of the United States. It borders Louisiana to the east, Arkansas to the northeast, Oklahoma to the north, New Mexico to the we ...

for twin-engine training on the AT‑17 and AT‑9. Throughout, Air Cadet McGovern showed skill as a pilot, with his exceptionally good depth perception

Depth perception is the ability to perceive distance to objects in the world using the visual system and visual perception. It is a major factor in perceiving the world in three dimensions.

Depth sensation is the corresponding term for non-hum ...

aiding him. Eleanor McGovern followed him to these duty stations, and was present when he received his wings and was commissioned a second lieutenant.

Training in the B-24

McGovern was assigned to Liberal Army Airfield in Kansas and its transition school to learn to fly the B‑24 Liberator, an assignment he was pleased with. McGovern recalled later: "Learning how to fly the B‑24 was the toughest part of the training. It was a difficult airplane to fly, physically, because in the early part of the war they didn't have hydraulic controls. If you can imagine driving a Mack truck without any power steering or power brakes, that's about what it was like at the controls. It was the biggest bomber we had at the time." Eleanor was constantly afraid. Accidents while training claimed a huge toll of airmen over the course of the war. This schooling was followed by a stint at Lincoln Army Airfield inNebraska

Nebraska ( ) is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. It borders South Dakota to the north; Iowa to the east and Missouri to the southeast, both across the Missouri River; Ka ...

, where McGovern met his B-24 crew.Ambrose, ''The Wild Blue'', pp. 94, 96, 99. Traveling around the country and mixing with people from different backgrounds proved to be a broadening experience for McGovern and others of his generation. The USAAF sped up training times for McGovern and others, owing to the heavy losses that bombing missions were suffering over Europe. Despite, and partly because of, the risk that McGovern might not come back from combat, the McGoverns decided to have a child, and Eleanor became pregnant. In June 1944, McGovern's crew received final training at Mountain Home Army Air Field

A mountain is an elevated portion of the Earth's crust

Earth's crust is its thick outer shell of rock, referring to less than one percent of the planet's radius and volume. It is the top component of the lithosphere, a solidified divi ...

in Idaho

Idaho ( ) is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Pacific Northwest and Mountain states, Mountain West subregions of the Western United States. It borders Montana and Wyoming to the east, Nevada and Utah to the south, and Washington (state), ...

. They then shipped out via Camp Patrick Henry

Camp Patrick Henry is a decommissioned United States Army base which was located in Warwick County, Virginia. After World War II, the site was redeveloped as a commercial airport, and became part of City of Newport News in 1958 when the former C ...

in Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern and Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic regions of the United States between the East Coast of the United States ...

, where McGovern found history books with which to fill downtime, especially during the trip overseas on a slow troopship.

Italy

In September 1944 McGovern joined the 741st Squadron of the455th Bombardment Group 455th may refer to:

*455th Air Expeditionary Wing, provisional United States Air Force USAFCENT unit

*455th Flying Training Squadron, United States Air Force unit of the Air Education and Training Command (AETC)

See also

*455 (number)

*455 (disamb ...

of the Fifteenth Air Force

The Fifteenth Air Force (15 AF) is a numbered air force of the United States Air Force's Air Combat Command (ACC). It is headquartered at Shaw Air Force Base. It was reactivated on 20 August 2020, merging the previous units of the Ninth Air Forc ...

, stationed at San Giovanni Airfield

The Foggia Airfield Complex was a series of World War II military airfields located within a radius of Foggia, in the Province of Foggia, Italy. The airfields were used by the United States Army Air Forces' Fifteenth Air Force as part of the st ...

near Cerignola

Cerignola (; ) is a town and ''comune'' of Apulia, Italy, in the province of Foggia, southeast from the town of Foggia. It has the third-largest land area of any ''comune'' in Italy, at , after Rome and Ravenna and it has the largest land ar ...

in the Apulia

Apulia ( ), also known by its Italian language, Italian name Puglia (), is a Regions of Italy, region of Italy, located in the Southern Italy, southern peninsular section of the country, bordering the Adriatic Sea to the east, the Strait of Ot ...

region of Italy.Ambrose, ''The Wild Blue'', pp. 124, 128–130. There he and his crew found a starving, disease-ridden local population wracked by the ill fortunes of war and far worse off than anything they had seen back home during the Depression. Those sights would form part of his later motivation to fight hunger. Starting on November 11, 1944, McGovern flew 35 missions over enemy territory from San Giovanni, the first five as co-pilot for an experienced crew and the rest as pilot for his own plane, known as the ''Dakota Queen'' after his wife Eleanor. His targets were in Austria

Austria, formally the Republic of Austria, is a landlocked country in Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine Federal states of Austria, states, of which the capital Vienna is the List of largest cities in Aust ...

; Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia ( ; Czech language, Czech and , ''Česko-Slovensko'') was a landlocked country in Central Europe, created in 1918, when it declared its independence from Austria-Hungary. In 1938, after the Munich Agreement, the Sudetenland beca ...

; Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany, officially known as the German Reich and later the Greater German Reich, was the German Reich, German state between 1933 and 1945, when Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party controlled the country, transforming it into a Totalit ...

; Hungary

Hungary is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning much of the Pannonian Basin, Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the south, Croatia and ...

; Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It extends from the Baltic Sea in the north to the Sudetes and Carpathian Mountains in the south, bordered by Lithuania and Russia to the northeast, Belarus and Ukrai ...

; and northern, German-controlled Italy, and were often either oil refinery

An oil refinery or petroleum refinery is an industrial processes, industrial process Factory, plant where petroleum (crude oil) is transformed and refining, refined into products such as gasoline (petrol), diesel fuel, Bitumen, asphalt base, ...

complexes or rail marshaling yards, all as part of the U.S. strategic bombing campaign in Europe. The eight- or nine-hour missions were grueling tests of endurance for pilots and crew, and while German fighter aircraft were a diminished threat by this time as compared with earlier in the war, his missions often faced heavy anti-aircraft artillery

Anti-aircraft warfare (AAW) is the counter to aerial warfare and includes "all measures designed to nullify or reduce the effectiveness of hostile air action".AAP-6 It encompasses surface-based, subsurface (Submarine#Armament, submarine-lau ...

fire that filled the sky with flak bursts.

On McGovern's December 15 mission over Linz

Linz (Pronunciation: , ; ) is the capital of Upper Austria and List of cities and towns in Austria, third-largest city in Austria. Located on the river Danube, the city is in the far north of Austria, south of the border with the Czech Repub ...

, his second as pilot, a piece of shrapnel from flak came through the windshield and missed fatally wounding him by only a few inches. The following day on a mission to Brüx

Most (; ) is a city in the Ústí nad Labem Region of the Czech Republic. It has about 63,000 inhabitants.

Most is an industrial city with a long tradition of lignite mining. Due to mining, the historic city was demolished and replaced by a plann ...

, he nearly collided with another bomber during close-formation flying in complete cloud cover. The following day, he was recommended for a medal after surviving a blown wheel on the always-dangerous B-24 take-off, completing a mission over Germany, and then landing without further damage to the plane. On a December 20 mission against the Škoda Works

The Škoda Works (, ) was one of the largest European industrial conglomerates of the 20th century. In 1859, Czech engineer Emil Škoda bought a foundry and machine factory in Plzeň, Bohemia, Austria-Hungary that had been established ten ye ...

at Pilsen, Czechoslovakia, McGovern's plane had one engine out and another in flames after being hit by flak. Unable to return to Italy, McGovern flew to a British airfield on Vis

Vis, ViS, VIS, and other capitalizations may refer to:

Places

* Vis (island), a Croatian island in the Adriatic sea

** Vis (town), on the island of Vis

* Vis (river), in south-central France

* Vis, Bulgaria, a village in Haskovo Province

* Visa ...

, a small island in the Adriatic Sea

The Adriatic Sea () is a body of water separating the Italian Peninsula from the Balkans, Balkan Peninsula. The Adriatic is the northernmost arm of the Mediterranean Sea, extending from the Strait of Otranto (where it connects to the Ionian Se ...

off the Yugoslav coast that was controlled by Josip Broz Tito

Josip Broz ( sh-Cyrl, Јосип Броз, ; 7 May 1892 – 4 May 1980), commonly known as Tito ( ; , ), was a Yugoslavia, Yugoslav communist revolutionary and politician who served in various positions of national leadership from 1943 unti ...

's Partisans

Partisan(s) or The Partisan(s) may refer to:

Military

* Partisan (military), paramilitary forces engaged behind the front line

** Francs-tireurs et partisans, communist-led French anti-fascist resistance against Nazi Germany during WWII

** Itali ...

. The short field, normally used by small fighter planes, was so unforgiving to four-engined aircraft that many of the bomber crews who tried to make emergency landings there perished. But McGovern successfully landed, saving his crew, a feat for which he was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross.Ambrose, ''The Wild Blue'', pp. 192–196.Schlesinger, ''A Thousand Days'', p. 176.

In January 1945 McGovern used R&R time to see every sight that he could in Rome, and to participate in an audience with the pope. Bad weather prevented many missions from being carried out during the winter, and during such downtime McGovern spent much time reading and discussing how the war had come about. He resolved that if he survived it, he would become a history professor. In February, McGovern was promoted to first lieutenant

First lieutenant is a commissioned officer military rank in many armed forces; in some forces, it is an appointment.

The rank of lieutenant has different meanings in different military formations, but in most forces it is sub-divided into a se ...

. On March 14 McGovern had an incident over Austria in which he accidentally bombed a family farmhouse when a jammed bomb inadvertently released above the structure and destroyed it, an event that haunted McGovern.Ambrose, ''The Wild Blue'', pp. 228–233. Four decades later, after McGovern related the incident during an Austrian television program and indicated he was still haunted by it, the owner of the farm called the television station to say that his farm was hit by that bomb but that no one had been hurt and the farmer felt that it had been worth the price if that event helped achieve the defeat of Nazi Germany in some small way. McGovern said finding this out was "an enormous release".

On returning to base from the flight, McGovern was told his first child Ann had been born four days earlier. April 25 saw McGovern's 35th mission, which marked fulfillment of the Fifteenth Air Force's requirement for a combat tour, against heavily defended Linz. The sky turned black and red with flak – McGovern later said, "Hell can't be any worse than that" – and the ''Dakota Queen'' was hit multiple times, resulting in 110 holes in its fuselage and wings and an inoperative hydraulic system. McGovern's waist gunner was injured, and his flight engineer was so unnerved by his experience that he would subsequently be hospitalized with battle fatigue, but McGovern managed to bring back the plane safely with the assistance of an improvised landing technique.Ambrose, ''The Wild Blue'', pp. 240–245. According to a McGovern associate speaking after McGovern's passing, sometime during his wartime experiences in Europe, McGovern had an extramarital affair and fathered a child with an unknown woman.

Postwar relief

In May and June 1945, following the end of the European war, McGovern continued with the 741st Bomb Squadron delivering surplus food and supplies nearTrieste

Trieste ( , ; ) is a city and seaport in northeastern Italy. It is the capital and largest city of the Regions of Italy#Autonomous regions with special statute, autonomous region of Friuli-Venezia Giulia, as well as of the Province of Trieste, ...

in Northeastern Italy; this was then trucked to the hungry in nearby locations, including to German prisoners of war. McGovern liked making these relief flights, as it gave a way to address the kinds of deprivations he had witnessed when first arriving in Italy. He then flew back to the United States with his crew.Knock, ''The Rise of a Prairie Statesman'', p. 75. McGovern was discharged from the Army Air Forces in July 1945, with the rank of first lieutenant. He was also awarded the Air Medal

The Air Medal (AM) is a military decoration of the United States Armed Forces. It was created in 1942 and is awarded for single acts of heroism or meritorious achievement while participating in aerial flight.

Criteria

The Air Medal was establi ...

with three oak leaf cluster

An oak leaf cluster is a ribbon device to denote preceding decorations and awards consisting of a miniature bronze or silver twig of four oak leaves with three acorns on the stem. It is authorized by the United States Armed Forces for a spec ...

s, one instance of which was for the safe landing on his final mission.

Later education and early career

Upon coming home, McGovern returned to Dakota Wesleyan University, aided by theG.I. Bill

The G.I. Bill, formally the Servicemen's Readjustment Act of 1944, was a law that provided a range of benefits for some of the returning World War II veterans (commonly referred to as G.I. (military), G.I.s). The original G.I. Bill expired in ...

, and graduated from there in June 1946 with a B.A.

A Bachelor of Arts (abbreviated B.A., BA, A.B. or AB; from the Latin ', ', or ') is the holder of a bachelor's degree awarded for an undergraduate program in the liberal arts, or, in some cases, other disciplines. A Bachelor of Arts degree ...

degree ''magna cum laude

Latin honors are a system of Latin phrases used in some colleges and universities to indicate the level of distinction with which an academic degree has been earned. The system is primarily used in the United States. It is also used in some Sout ...

''.Anson, ''McGovern'', pp. 50–53. For a while he suffered from nightmares about flying through flak barrages or his plane being on fire. He continued with debate, again winning the state Peace Oratory Contest with a speech entitled "From Cave to Cave" that presented a Christian-influenced Wilsonian

Wilsonianism, or Wilsonian idealism, is a certain type of foreign policy advice. The term comes from the ideas and proposals of United States President Woodrow Wilson. He issued his famous Fourteen Points in January 1918 as a basis for ending Wor ...

outlook. The couple's second daughter, Susan, was born in March 1946.

McGovern switched from Wesleyan Methodism to less fundamentalist regular Methodism

Methodism, also called the Methodist movement, is a Protestant Christianity, Christian Christian tradition, tradition whose origins, doctrine and practice derive from the life and teachings of John Wesley. George Whitefield and John's brother ...

. Influenced by Walter Rauschenbusch

Walter Rauschenbusch (1861–1918) was an American theologian and Baptist pastor who taught at the Rochester Theological Seminary. Rauschenbusch was a key figure in the Social Gospel and single tax movements that flourished in the United States ...

and the Social Gospel

The Social Gospel is a social movement within Protestantism that aims to apply Christian ethics to social problems, especially issues of social justice such as economic inequality, poverty, alcoholism, crime, racial tensions, slums, unclean en ...

movement, McGovern began divinity studies at Garrett Theological Seminary

Garrett may refer to:

Places in the United States

* Garrett, Illinois, a village

* Garrett, Indiana, a city

* Garrett, Floyd County, Kentucky, an unincorporated community

* Garrett, Meade County, Kentucky, an unincorporated community

* Garrett, ...

in Evanston, Illinois

Evanston is a city in Cook County, Illinois, United States, situated on the North Shore (Chicago), North Shore along Lake Michigan. A suburb of Chicago, Evanston is north of Chicago Loop, downtown Chicago, bordered by Chicago to the south, Skok ...

, near Chicago

Chicago is the List of municipalities in Illinois, most populous city in the U.S. state of Illinois and in the Midwestern United States. With a population of 2,746,388, as of the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, it is the List of Unite ...

. Among Methodist seminaries, Garrett tended towards social involvement paired with a theologically liberal approach, and many of the students there leaned towards pacifism. McGovern was influenced by the weekly sermons of a well-known local minister, Ernest Fremont Tittle, and the ideas of Boston personalism

Personalism is an intellectual stance that emphasizes the importance of human persons. Personalism exists in many different versions, and this makes it somewhat difficult to define as a philosophical and theological movement. Friedrich Schleierm ...

. McGovern preached as a Methodist student supply minister at Diamond Lake Church in Mundelein, Illinois

Mundelein is a village in Lake County, Illinois, United States and a northern suburb of Chicago. Per the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, the population was 31,560, making this the fourth largest town in Lake County. The village straddles ...

, during 1946 and 1947, but became dissatisfied by the minutiae of his pastoral duties. In late 1947 McGovern left the ministry and enrolled in graduate studies at Northwestern University in Evanston, where he also worked as a teaching assistant.Anson, ''McGovern'', pp. 55–56. The relatively small history program there was among the best in the country,Knock, "Come Home America", p. 89. and McGovern took courses given by noted academics Ray Allen Billington

Ray Allen Billington (September 28, 1903 in Bay City, Michigan – March 7, 1981 in San Marino, California) was an American historian who researched the history of the American frontier and the American West, becoming one of the leading defenders ...

, Richard W. Leopold, and L. S. Stavrianos. He received an M.A.

A Master of Arts ( or ''Artium Magister''; abbreviated MA or AM) is the holder of a master's degree awarded by universities in many countries. The degree is usually contrasted with that of Master of Science. Those admitted to the degree have ...

in history in 1949.

McGovern then returned to his alma mater, Dakota Wesleyan, and became a professor of history and political science. With the assistance of a Hearst fellowship for 1949–50, he continued pursuing graduate studies during summers and other free time. The couple's third daughter, Teresa, was born in June 1949. Eleanor McGovern began to suffer from bouts of depression but continued to assume the large share of household and child-rearing duties.McGovern, ''Terry'', pp. 44–46, 49. McGovern earned a Ph.D.

A Doctor of Philosophy (PhD, DPhil; or ) is a terminal degree that usually denotes the highest level of academic achievement in a given discipline and is awarded following a course of graduate study and original research. The name of the deg ...

in history from Northwestern University

Northwestern University (NU) is a Private university, private research university in Evanston, Illinois, United States. Established in 1851 to serve the historic Northwest Territory, it is the oldest University charter, chartered university in ...

in 1953. His 450-page dissertation, ''The Colorado Coal Strike, 1913–1914'', was a sympathetic account of the miners' revolt against Rockefeller interests in the Colorado Coalfield War

The Colorado Coalfield War was a major Labor dispute, labor uprising in the southern and central Colorado Front Range between September 1913 and December 1914. Striking began in late summer 1913, organized by the United Mine Workers of Ameri ...

. His thesis advisor, noted historian Arthur S. Link, later said he had not seen a better student than McGovern in 26 years of teaching. McGovern was influenced not only by Link and the " Consensus School" of American historians but also by the previous generation of "progressive" historians. Most of his future analyses of world events would be informed by his training as a historian, as well as his personal experiences during the Great Depression and World War II.Knock, "Come Home America", p. 94. Meanwhile, McGovern had become a popular if politically outspoken teacher at Dakota Wesleyan, with students dedicating the college yearbook to him in 1952.Knock, "Come Home America", p. 92.

Nominally a Republican growing up, McGovern began to admire Democratic president Franklin Delano Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), also known as FDR, was the 32nd president of the United States, serving from 1933 until his death in 1945. He is the longest-serving U.S. president, and the only one to have served ...

during World War II, even though he supported Roosevelt's opponent Thomas Dewey

Thomas Edmund Dewey (March 24, 1902 – March 16, 1971) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 47th Governor of New York from 1943 to 1954. He was the Republican Party's nominee for president of the United States in 1944 and ...

in the 1944 U.S. presidential election.White, ''The Making of the President 1972'', pp. 40–41.Knock, ''The Rise of a Prairie Statesman'', p. 122. At Northwestern, his exposure to the work of China scholars John King Fairbank

John King Fairbank (May 24, 1907September 14, 1991) was an American historian of China and United States–China relations. He taught at Harvard University from 1936 until his retirement in 1977. He is credited with building the field of China ...

and Owen Lattimore

Owen Lattimore (July 29, 1900 – May 31, 1989) was an American Orientalist and writer. He was an influential scholar of China and Central Asia, especially Mongolia. Although he never earned a college degree, in the 1930s he was editor of '' Pac ...

had convinced him that unrest in Southeast Asia

Southeast Asia is the geographical United Nations geoscheme for Asia#South-eastern Asia, southeastern region of Asia, consisting of the regions that are situated south of China, east of the Indian subcontinent, and northwest of the Mainland Au ...

was homegrown and that U.S. foreign policy toward Asia was counterproductive. Discouraged by the onset of the Cold War, and never thinking well of incumbent president Harry S. Truman

Harry S. Truman (May 8, 1884December 26, 1972) was the 33rd president of the United States, serving from 1945 to 1953. As the 34th vice president in 1945, he assumed the presidency upon the death of Franklin D. Roosevelt that year. Subsequen ...

, in the 1948 U.S. presidential election McGovern was attracted to the campaign of former vice president and secretary of agriculture Henry A. Wallace

Henry Agard Wallace (October 7, 1888 – November 18, 1965) was the 33rd vice president of the United States, serving from 1941 to 1945, under President Franklin D. Roosevelt. He served as the 11th U.S. secretary of agriculture and the 10th U.S ...

.Anson, ''McGovern'', pp. 58–61. He wrote columns supporting Wallace in the ''Mitchell Daily Republic

The ''Mitchell Daily Republic'' is a daily newspaper published in Mitchell, South Dakota. The paper's circulation is reported to be 9,859 and primarily serves Davison County, South Dakota. It was founded in 1934 and is currently owned by the F ...

'' and attended the Wallace Progressive Party's first national convention as a delegate

Delegate or delegates may refer to:

* Delegate, New South Wales, a town in Australia

* Delegate (CLI), a computer programming technique

* Delegate (American politics), a representative in any of various political organizations

* Delegate (United S ...

. There he became disturbed by aspects of the convention atmosphere, decades later referring to "a certain rigidity and fanaticism on the part of a few of the strategists." He remained a public supporter of Wallace and the Progressive Party afterward. As Wallace was kept off the ballot in Illinois where McGovern was now registered, McGovern did not vote in the general election.

By 1952, McGovern was coming to think of himself as a Democrat

Democrat, Democrats, or Democratic may refer to:

Politics

*A proponent of democracy, or democratic government; a form of government involving rule by the people.

*A member of a Democratic Party:

**Democratic Party (Cyprus) (DCY)

**Democratic Part ...

. He was captivated by a radio broadcast of Governor Adlai Stevenson Adlai Stevenson may refer to:

* Adlai Stevenson I

Adlai Ewing Stevenson (October 23, 1835 – June 14, 1914) was an American politician and diplomat who served as the 23rd vice president of the United States from 1893 to 1897 under President Gr ...

's speech accepting the presidential nomination at the 1952 Democratic National Convention

The 1952 Democratic National Convention was held at the International Amphitheatre in Chicago, Illinois from July 21 to July 26, 1952, which was the same arena the Republicans had gathered in a few weeks earlier for their national convention from ...

.McGovern, ''Grassroots'', pp. 49–51. He immediately dedicated himself to Stevenson's campaign, publishing seven articles in the ''Mitchell Daily Republic'' newspaper outlining the historical issues that separated the Democratic Party from the Republicans. The McGoverns named their only son, Steven, born immediately after the convention, after his new hero. Although Stevenson lost the election, McGovern remained active in politics, believing that "the engine of progress in our time in America is the Democratic Party." In early 1953,E. McGovern, ''Uphill'', p. 86. McGovern left a tenure-track

Tenure is a type of academic appointment that protects its holder from being fired or laid off except for cause, or under extraordinary circumstances such as financial exigency or program discontinuation. Academic tenure originated in the United ...

position at the university to become executive secretary of the South Dakota Democratic Party

The South Dakota Democratic Party is the affiliate of the Democratic Party in the U.S. state of South Dakota. The party currently has very weak electoral power in the state, controlling none of South Dakota's statewide or federal elected offices ...

,''Current Year Biography 1967'', p. 266. the state chair having recruited him after reading his articles. Democrats in the state were at a low, holding no statewide offices and only 2 of the 110 seats in the state legislature. Friends and political figures had counseled McGovern against making the move, but despite his mild, unassuming manner, McGovern had an ambitious nature and was intent upon starting a political career of his own.

McGovern spent the following years rebuilding and revitalizing the party, building up a large list of voter contacts via frequent travel around the state. Democrats showed improvement in the 1954 elections, winning 25 seats in the state legislature.Anson, ''McGovern'', pp. 73–75. From 1954 to 1956 he also was on a political organization advisory group for the Democratic National Committee

The Democratic National Committee (DNC) is the principal executive leadership board of the United States's Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party. According to the party charter, it has "general responsibility for the affairs of the ...

. The McGoverns' fifth and final child, Mary, was born in 1955.

U.S. House of Representatives

In 1956, McGovern sought elective office himself, and ran for the House of Representatives fromSouth Dakota's 1st congressional district

South Dakota's 1st congressional district is an obsolete List of United States congressional districts, congressional district that existed from 1913 to 1983.

When South Dakota was admitted into the Union in 1889, it was allocated two congressi ...

, which consisted of the counties east of the Missouri River

The Missouri River is a river in the Central United States, Central and Mountain states, Mountain West regions of the United States. The nation's longest, it rises in the eastern Centennial Mountains of the Bitterroot Range of the Rocky Moun ...

. He faced four-term incumbent Republican Party representative Harold O. Lovre. Aided by the voter lists he had earlier accumulated, McGovern ran a low-budget campaign, spending $12,000 while borrowing $5,000. His quiet personality appealed to voters he met, while Lovre suffered from a general unhappiness over Eisenhower administration

Dwight D. Eisenhower's tenure as the 34th president of the United States began with his first inauguration on January 20, 1953, and ended on January 20, 1961. Eisenhower, a Republican from Kansas, took office following his landslide victor ...

farm policy. When polls showed McGovern gaining, Lovre's campaign implied that McGovern's support for admitting the People's Republic of China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. With population of China, a population exceeding 1.4 billion, it is the list of countries by population (United Nations), second-most populous country after ...

to the United Nations and his past support for Henry Wallace meant that McGovern was a communist appeaser or sympathizer.Anson, ''McGovern'', pp. 81–84. In his closing speech, McGovern responded: "I have always despised communism and every other ruthless tyranny over the mind and spirit of man." McGovern staged an upset victory, gaining 116,516 votes to his opponent's 105,835, and became the first Democrat elected to Congress from South Dakota in 22 years. The McGoverns established a home in Chevy Chase, Maryland

Chevy Chase () is the colloquial name of an area that includes a town, several incorporated villages, and an unincorporated census-designated place in southern Montgomery County, Maryland; and one adjoining neighborhood in northwest Washington, D ...

.

Entering the 85th United States Congress

The 85th United States Congress was a meeting of the legislative branch of the United States federal government, composed of the United States Senate and the United States House of Representatives. It met in Washington, D.C. from January 3, 1957 ...

, McGovern became a member of the House Committee on Education and Labor. As a representative, McGovern was attentive to his district. He became a staunch supporter of higher commodity prices, farm price supports, grain storage programs, and beef import controls, believing that such stored commodities programs guarded against drought and similar emergencies. He favored rural development, federal aid to small business and to education, and medical coverage for the aged under Social Security. In 1957 he traveled and studied conditions in the Middle East under a fellowship from the American Christian Palestine Committee. McGovern first allied with the Kennedy family

The Kennedy family () is an American political family that has long been prominent in American politics, public service, entertainment, and business. In 1884, 35 years after the family's arrival from County Wexford, Ireland, Patrick Joseph "P ...

by supporting a House version of Senator John F. Kennedy's eventually unsuccessful labor reform bill.

In his 1958 reelection campaign, McGovern faced a strong challenge from South Dakota's two-term Republican governor and World War II Medal of Honor

The Medal of Honor (MOH) is the United States Armed Forces' highest Awards and decorations of the United States Armed Forces, military decoration and is awarded to recognize American United States Army, soldiers, United States Navy, sailors, Un ...

recipient Joe Foss

Joseph Jacob Foss (April 17, 1915January 1, 2003) was a United States Marine Corps Major and a leading Marine fighter ace in World War II. He received the Medal of Honor in recognition of his role in air combat during the Guadalcanal Campaign. In ...

, who was initially considered the favorite to win.Anson, ''McGovern'', pp. 87–90. McGovern ran an effective campaign that showcased his political strengths of having firm beliefs and the ability to articulate them in debates and on the stump.Brokaw, ''The Greatest Generation'', p. 121. He prevailed with a slightly larger margin than two years before. In the 86th United States Congress

The 86th United States Congress was a meeting of the legislative branch of the United States federal government, composed of the United States Senate and the United States House of Representatives. It met in Washington, D.C. from January 3, 1959 ...

, McGovern was assigned to the House Committee on Agriculture

The United States House of Representatives Committee on Agriculture, or Agriculture Committee is a standing committee of the United States House of Representatives. The House Committee on Agriculture has general jurisdiction over federal agricultu ...

. The longtime chairman of the committee, Harold D. Cooley, would subsequently say, "I cannot recall a single member of Congress who has fought more vigorously or intelligently for American farmers than Congressman McGovern." He helped pass a new food-stamp law. He was one of nine representatives from Congress to the NATO Parliamentary Assembly

The NATO Parliamentary Assembly serves as the consultative interparliamentary organisation for the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). It consists of delegates from the parliaments of the 32 NATO member countries as well as from associate ...

conferences of 1958 and 1959. Along with Senator Hubert H. Humphrey, McGovern strongly advocated a reconstruction of Public Law 480

Since the 1950s, in different administrative and organizational forms, the United States' Food for Peace program has used America's agricultural surpluses to provide food assistance around the world, broaden international trade, and advance U.S. ...

(an agricultural surplus act that had come into being under Eisenhower) with a greater emphasis on feeding the hungry around the world, the establishment of an executive office to run operations, and the goal of promoting peace and stability around the world. During his time in the House, McGovern was regarded as a liberal

Liberal or liberalism may refer to:

Politics

* Generally, a supporter of the political philosophy liberalism. Liberals may be politically left or right but tend to be centrist.

* An adherent of a Liberal Party (See also Liberal parties by country ...

overall, and voted in accordance with the rated positions of Americans for Democratic Action

Americans for Democratic Action (ADA) is a liberal American political organization advocating progressive policies. ADA views itself as supporting social and economic justice through lobbying, grassroots organizing, research, and supporting p ...

(ADA) 34 times and against 3 times. Two of the themes of his House career, improvements for rural America and the war on hunger, would be defining ones of his legislative career and public life.

McGovern did not vote on the initial House bill for the Civil Rights Act of 1957

The Civil Rights Act of 1957 was the first federal civil rights law passed by the United States Congress since the Civil Rights Act of 1875. The bill was passed by the 85th United States Congress and signed into law by President Dwight D. E ...

, but voted in favor of the Senate amendment to the bill in August 1957. McGovern voted in favor initial House bill for the Civil Rights Act of 1960

The Civil Rights Act of 1960 () is a United States federal law that established federal inspection of local voter registration polls and introduced penalties for anyone who obstructed someone's attempt to register to vote. It dealt primarily wi ...

, but did not vote on the Senate amendment to the bill in April 1960. In 1960, McGovern decided to run for the U.S. Senate and challenge the Republican incumbent Karl Mundt

Karl Earl Mundt (June 3, 1900August 16, 1974) was an American educator and a Republican member of the United States Congress, representing South Dakota in the United States House of Representatives (1939–1948) and in the United States Senate ...

, a formidable figure in South Dakota politics whom McGovern loathed as an old-style McCarthyite

McCarthyism is a political practice defined by the political repression and persecution of left-wing individuals and a campaign spreading fear of communist and Soviet influence on American institutions and of Soviet espionage in the United St ...

.Anson, ''McGovern'', pp. 92–94. The race centered mostly on rural issues, but John F. Kennedy's Catholicism was a drawback at the top of the ticket in the mostly Protestant state. McGovern made careless charges during the campaign, and the press turned against him; he would say eleven years later, "It was my worst campaign. I hated undtso much I lost my sense of balance." McGovern was defeated in the November 1960 election, gaining 145,217 votes to Mundt's 160,579, but the margin was one third of Kennedy's loss to Vice President Richard M. Nixon in the state's presidential contest.

Food for Peace director

Having relinquished his House seat to run for the Senate, McGovern was available for a position in the new

Having relinquished his House seat to run for the Senate, McGovern was available for a position in the new Kennedy administration

John F. Kennedy's tenure as the List of presidents of the United States, 35th president of the United States began with Inauguration of John F. Kennedy, his inauguration on January 20, 1961, and ended with Assassination of John F. Kennedy, his ...

. McGovern was picked to become a special assistant to the president and first director of Kennedy's high-priority Food for Peace

Since the 1950s, in different administrative and organizational forms, the United States' Food for Peace program has used America's agricultural surpluses to provide food assistance around the world, broaden international trade, and advance U.S. ...

program, which realized what McGovern had been advocating in the House. McGovern assumed the post on January 21, 1961.

As director, McGovern urged the greater use of food to enable foreign economic development, saying, "We should thank God that we have a food abundance and use the over-supply among the underprivileged at home and abroad." He found space for the program in the Executive Office Building rather than be subservient to either the State Department

The United States Department of State (DOS), or simply the State Department, is an executive department of the U.S. federal government responsible for the country's foreign policy and relations. Equivalent to the ministry of foreign affairs o ...

or Department of Agriculture

An agriculture ministry (also called an agriculture department, agriculture board, agriculture council, or agriculture agency, or ministry of rural development) is a ministry charged with agriculture. The ministry is often headed by a minister f ...

. McGovern worked with deputy director James W. Symington and Kennedy advisor Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr.

Arthur Meier Schlesinger Jr. ( ; born Arthur Bancroft Schlesinger; October 15, 1917 – February 28, 2007) was an American historian, social critic, and public intellectual. The son of the influential historian Arthur M. Schlesinger Sr. and a ...

in visiting South America to discuss surplus grain distribution, and attended meetings of the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization

The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations; . (FAO) is a specialized agency of the United Nations that leads international efforts to defeat hunger and improve nutrition and food security. Its Latin motto, , translates ...

. In June 1961, McGovern became seriously ill with hepatitis

Hepatitis is inflammation of the liver parenchyma, liver tissue. Some people or animals with hepatitis have no symptoms, whereas others develop yellow discoloration of the skin and whites of the eyes (jaundice), Anorexia (symptom), poor appetite ...

, contracted from an infected White House dispensary needle used to give him inoculations for his South American trip; he was hospitalized and unable to come to his office for two months;Anson, ''McGovern'', pp. 110–113. his campaign disguised the condition by saying it was a mild kidney infection.

By the close of 1961, the Food for Peace program was operating in a dozen countries, and 10 million more people had been fed with American surplus than the year before. In February 1962, McGovern visited India and oversaw an expanded school lunch

A school meal (whether it is a breakfast, lunch, or evening meal) is a meal provided to students and sometimes teachers at a school, typically in the middle or beginning of the school day. Countries around the world offer various kinds of schoo ...

program thanks to Food for Peace. Subsequently, one in five Indian schoolchildren would be fed from it; by mid-1962, it fed 35 million children around the world.Knock, "Feeding the World and Thwarting the Communists", p. 107. During an audience in Rome, Pope John XXIII

Pope John XXIII (born Angelo Giuseppe Roncalli; 25 November 18813 June 1963) was head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City State from 28 October 1958 until his death on 3 June 1963. He is the most recent pope to take ...

warmly praised McGovern's work,Knock, "Feeding the World and Thwarting the Communists", pp. 114–115. and the distribution program was also popular among South Dakota's wheat farmers. In addition, McGovern was instrumental in the creation of the United Nations-run World Food Programme

The World Food Programme (WFP) is an international organization within the United Nations that provides food assistance worldwide. It is the world's largest humanitarian organization and the leading provider of school meals. Founded in 1961 ...

in December 1961; it started distributing food to affected regions of the world the following year and would go on to become the largest humanitarian agency fighting hunger worldwide.

Administration was never McGovern's strength, and he was restless for another try at the Senate. With the approval of President Kennedy, McGovern resigned his post on July 18, 1962. Kennedy said that under McGovern the program had "become a vital force in the world", improving living conditions and economies of allies and creating "a powerful barrier to the spread of Communism". Columnist Drew Pearson wrote that it was one of the "most spectacular achievements of the young Kennedy administration", while Schlesinger would later write that Food for Peace had been "the greatest unseen weapon of Kennedy's third-world policy".

U.S. Senator

1962 election and early years as a senator

In April 1962, McGovern announced he would run for election to South Dakota's other Senate seat, intending to face incumbent RepublicanFrancis H. Case

Francis Higbee Case (December 9, 1896June 22, 1962) was an American journalist and politician who served for 25 years as a member of the United States Congress from South Dakota. He was a Republican.

Biography

Case was born in Everly, Iowa, t ...

. Case died in June, and McGovern instead faced an appointed senator, former lieutenant governor Joseph H. Bottum. Much of the campaign revolved around policies of the Kennedy administration and its New Frontier

The term ''New Frontier'' was used by Democratic presidential candidate John F. Kennedy in his acceptance speech, delivered July 15, in the 1960 United States presidential election to the Democratic National Convention at the Los Angeles Memo ...

;''Current Year Biography 1967'', p. 267. Bottum accused the Kennedy family of trying to buy the Senate seat. McGovern appealed to those worried about the outflux of young people from the state, and had the strong support of the Farmers Union. Polls showed Bottum slightly ahead throughout the race, and McGovern was hampered by a recurrence of his hepatitis problem in the final weeks of the campaign. (During this hospitalization, McGovern read Theodore H. White's classic ''The Making of the President 1960