Sen no Rikyū on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

, also known simply as Rikyū, was a Japanese tea master considered the most important influence on the ''chanoyu'', the Japanese "Way of Tea", particularly the tradition of '' wabi-cha''. He was also the first to emphasize several key aspects of the ceremony, including rustic simplicity, directness of approach and honesty of self. Originating from the Sengoku and Azuchi–Momoyama periods, these aspects of the tea ceremony persist.

There are three ''

Urasenke website

Accessed May 16, 2006. As a young man, Rikyū studied tea under the townsman of Sakai named Kitamuki Dōchin (1504–62), and at nineteen, through Dōchin's introduction, he began to study tea under Takeno Jō'ō, who is also associated with the development of the wabi aesthetic in tea ceremony. He is believed to have received the Buddhist name from the Rinzai Zen priest Dairin Sōtō (1480–1568) of Nanshū-ji in Sakai. He married a woman known as Hōshin Myōju (d. 1577) around when he was 21. Rikyū also underwent

It was during his later years that Rikyū began to use very tiny, rustic tea rooms referred as ('grass hermitage'), such as the two-

It was during his later years that Rikyū began to use very tiny, rustic tea rooms referred as ('grass hermitage'), such as the two-flowers for chanoyu are not called ikebana; need verification about him practicing ikebana

One of his favourite gardens was said to be at Chishaku-in in Kyoto.

OCLC 469293854

* Sansom, George Bailey. (1961). ''A History of Japan: 1334-1615.'' London: Cresset Press

OCLC 216583509

Momoyama, Japanese Art in the Age of Grandeur

an exhibition catalog from The Metropolitan Museum of Art (fully available online as PDF), which contains material on Sen no Rikyū

Turning point : Oribe and the arts of sixteenth-century Japan

an exhibition catalog from The Metropolitan Museum of Art (fully available online as PDF), which contains material on Sen no Rikyū {{DEFAULTSORT:Sen no, Rikyu 1522 births 1591 deaths Japanese tea masters Male suicides Suicides by seppuku People from Sakai, Osaka Forced suicides 16th-century suicides Japanese Rinzai Zen Buddhists Buddhist clergy of Muromachi-period Japan Clergy of the Azuchi–Momoyama period

iemoto

is a Japanese term used to refer to the founder or current Grand Master of a certain school of traditional Japanese art. It is used synonymously with the term when it refers to the family or house that the iemoto is head of and represents.

Th ...

'' (''sōke

, pronounced , is a Japanese term that means "the head family ouse" In the realm of Japanese traditional arts, it is used synonymously with the term '' iemoto''. Thus, it is often used to indicate "headmaster" (or sometimes translated as "head o ...

''), or 'head houses' of the Japanese Way of Tea, that are directly descended from Rikyū: the Omotesenke, Urasenke, and Mushakōjisenke, all three of which are dedicated to passing forward the teachings of their mutual family founder, Rikyū. They are collectively called .

Early life

Rikyū was born inSakai

is a city located in Osaka Prefecture, Japan. It has been one of the largest and most important seaports of Japan since the medieval era. Sakai is known for its '' kofun'', keyhole-shaped burial mounds dating from the fifth century. The ''kofun ...

in present-day Osaka Prefecture

is a prefecture of Japan located in the Kansai region of Honshu. Osaka Prefecture has a population of 8,778,035 () and has a geographic area of . Osaka Prefecture borders Hyōgo Prefecture to the northwest, Kyoto Prefecture to the north, Nara ...

. His father was a warehouse owner named , who later in life also used the family name Sen, and his mother was . His childhood name was ."The Urasenke Legacy: Family Lineage", iUrasenke website

Accessed May 16, 2006. As a young man, Rikyū studied tea under the townsman of Sakai named Kitamuki Dōchin (1504–62), and at nineteen, through Dōchin's introduction, he began to study tea under Takeno Jō'ō, who is also associated with the development of the wabi aesthetic in tea ceremony. He is believed to have received the Buddhist name from the Rinzai Zen priest Dairin Sōtō (1480–1568) of Nanshū-ji in Sakai. He married a woman known as Hōshin Myōju (d. 1577) around when he was 21. Rikyū also underwent

Zen

Zen (; from Chinese: ''Chán''; in Korean: ''Sŏn'', and Vietnamese: ''Thiền'') is a Mahayana Buddhist tradition that developed in China during the Tang dynasty by blending Indian Mahayana Buddhism, particularly Yogacara and Madhyamaka phil ...

training at Daitoku-ji

is a Rinzai school Zen Buddhist temple in the Murasakino neighborhood of Kita-ku in the city of Kyoto Japan. Its ('' sangō'') is . The Daitoku-ji temple complex is one of the largest Zen temples in Kyoto, covering more than . In addition to ...

in Kyoto. Not much is known about his middle years.

Later years

In 1579, at the age of 58, Rikyū became a tea master forOda Nobunaga

was a Japanese ''daimyō'' and one of the leading figures of the Sengoku period, Sengoku and Azuchi-Momoyama periods. He was the and regarded as the first "Great Unifier" of Japan. He is sometimes referred as the "Demon Daimyō" and "Demo ...

and, following Nobunaga's death in 1582, he was a tea master for Toyotomi Hideyoshi

, otherwise known as and , was a Japanese samurai and ''daimyō'' (feudal lord) of the late Sengoku period, Sengoku and Azuchi-Momoyama periods and regarded as the second "Great Unifier" of Japan.Richard Holmes, The World Atlas of Warfare: ...

. His relationship with Hideyoshi quickly deepened, and he entered Hideyoshi's circle of confidants, effectively becoming the most influential figure in the world of . In 1585, as he needed extra credentials to enter the Imperial Palace in order to help at a tea gathering that would be given by Hideyoshi for Emperor Ōgimachi, the emperor bestowed upon him the Buddhist lay name and title . Another major event of Hideyoshi's that Rikyū played a central role in was the Grand Kitano Tea Ceremony, held by Hideyoshi at the Kitano Tenman-gū in 1587.

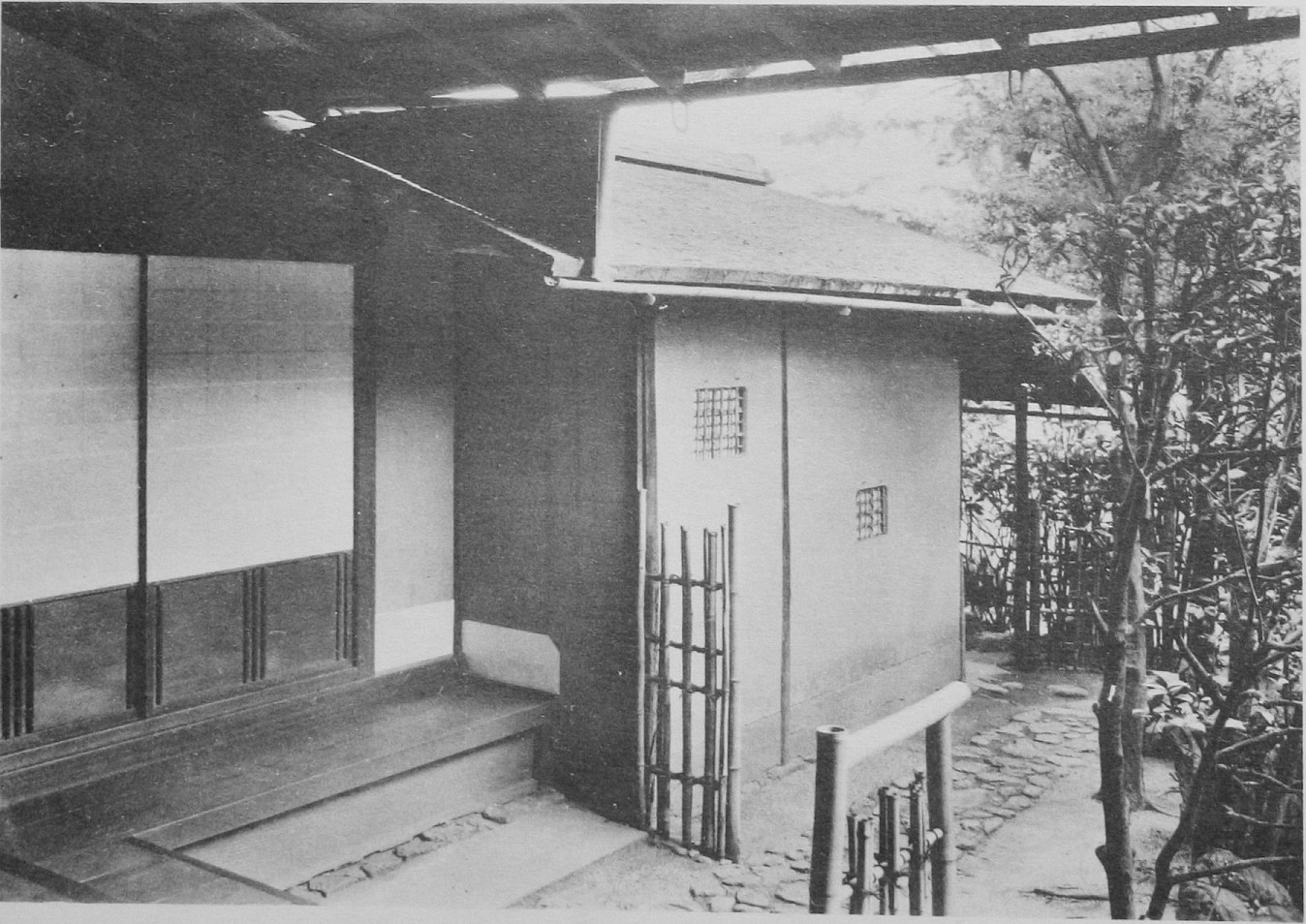

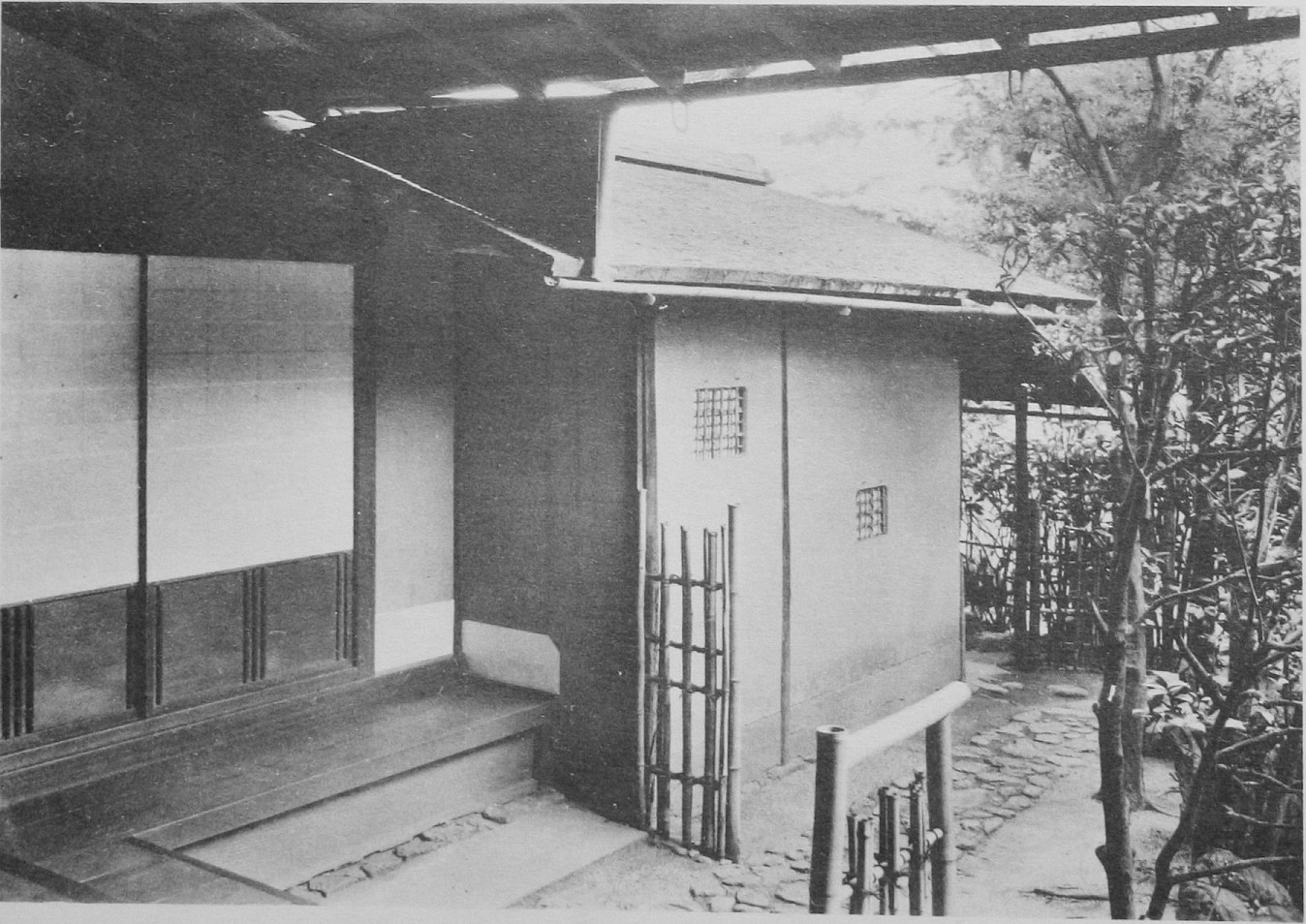

It was during his later years that Rikyū began to use very tiny, rustic tea rooms referred as ('grass hermitage'), such as the two-

It was during his later years that Rikyū began to use very tiny, rustic tea rooms referred as ('grass hermitage'), such as the two-tatami

are soft mats used as flooring material in traditional Japanese-style rooms. They are made in standard sizes, twice as long as wide, about , depending on the region. In martial arts, tatami are used for training in a dojo and for competition.

...

mat tea room named Tai-an, which can be seen today at Myōki-an temple in Yamazaki, a suburb of Kyoto, and which is credited to his design. This tea room has been designated as a National Treasure. He also developed many implements for tea ceremony, including flower containers, teascoops, and lid rests made of bamboo, and also used everyday objects for tea ceremony, often in novel ways.

Raku teabowls were originated through his collaboration with a tile-maker named Raku Chōjirō. Rikyū had a preference for simple, rustic items made in Japan, rather than the expensive Chinese-made items that were fashionable at the time. Though not the inventor of the philosophy of '' wabi-sabi'', which finds beauty in the very simple, Rikyū is among those most responsible for popularizing it, developing it, and incorporating it into tea ceremony. He created a new form of tea ceremony using very simple instruments and surroundings. This and his other beliefs and teachings came to be known as (the grass-thatched hermitage style of ), or more generally, . This line of that his descendants and followers carried on was recognized as the .

A writer and poet, the tea master referred to the ware and its relationship with the tea ceremony, saying, "Though you wipe your hands and brush off the dust and dirt from the vessels, what is the use of all this fuss if the heart is still impure?"

Two of his primary disciples were Nanbō Sōkei (; dates unknown), a somewhat legendary Zen priest; and Yamanoue Sōji (1544–90), a townsman of Sakai. Another was Furuta Oribe (1544-1615), who became a celebrated tea master after Rikyū's death. Nanbō is credited as the original author of the '' Nanpō roku'', a record of Rikyū's teachings. There is, however, some debate as to whether Nanbō even existed, and some scholars theorize that his writings were actually by samurai litterateur Tachibana Jitsuzan (1655-1708), who claimed to have found and transcribed these texts. Yamanoue's chronicle, the (), gives commentary about Rikyū's teachings and the state of at the time of its writing.

Rikyū had a number of children, including a son known in history as Sen Dōan, and daughter known as Okame. This daughter became the bride of Rikyū's second wife's son by a previous marriage, known in history as Sen Shōan. Due to many complex circumstances, Sen Shōan, rather than Rikyū's legitimate heir, Dōan, became the person counted as the 2nd generation in the Sen-family's tradition of (see at schools of Japanese tea ceremony).

Rikyū also wrote poetry, and practiced ''ikebana

is the Japanese art of flower arrangement. It is also known as . The origin of ikebana can be traced back to the ancient Japanese custom of erecting Evergreen, evergreen trees and decorating them with flowers as yorishiro () to invite the go ...

''.Death

Although Rikyū had been one of Hideyoshi's closest confidants, because of crucial differences of opinion and because he was too independent, Hideyoshi ordered him to commit ritual suicide. One year earlier, after theSiege of Odawara (1590)

The third occurred in 1590, and was the primary action in Toyotomi Hideyoshi's campaign to eliminate the Hōjō clan as a threat to his power. The months leading up to it saw hasty but major improvements in the defense of the castle, as H ...

, his famous disciple Yamanoue Sōji was tortured and decapitated on Hideyoshi's orders. While Hideyoshi's reason may never be known for certain, it is known that Rikyū committed ''seppuku'' at his residence within Hideyoshi's Jurakudai palace in Kyoto

Kyoto ( or ; Japanese language, Japanese: , ''Kyōto'' ), officially , is the capital city of Kyoto Prefecture in the Kansai region of Japan's largest and most populous island of Honshu. , the city had a population of 1.46 million, making it t ...

in 1591 on the 28th day of the 2nd month (of the traditional Japanese lunar calendar

A lunar calendar is a calendar based on the monthly cycles of the Moon's phases ( synodic months, lunations), in contrast to solar calendars, whose annual cycles are based on the solar year, and lunisolar calendars, whose lunar months are br ...

; or April 21 when calculated according to the modern Gregorian calendar

The Gregorian calendar is the calendar used in most parts of the world. It went into effect in October 1582 following the papal bull issued by Pope Gregory XIII, which introduced it as a modification of, and replacement for, the Julian cale ...

), at the age of seventy.Okakura Kakuzo, ''The Illustrated Book of Tea'' (Okakura's classic with 17th-19th century ukiyo-e woodblock prints and a chapter on Sen no Rikyu). Chiang Mai: Cognoscenti Books. 2012. ASIN: B009033C6M

According to Okakura Kakuzō in '' The Book of Tea'', Rikyū's last act was to hold an exquisite tea ceremony. After serving all his guests, he presented each piece of the tea-equipage for their inspection, along with an exquisite '' kakemono'', which Okakura described as "a wonderful writing by an ancient monk dealing with the evanescence of all things". Rikyū presented each of his guests with a piece of the equipment as a souvenir, with the exception of the bowl, which he shattered, as he uttered the words: "Never again shall this cup, polluted by the lips of misfortune, be used by man." As the guests departed, one remained to serve as witness to Rikyū's death. Rikyū's last words, which he wrote down as a death poem

The death poem is a genre of poetry that developed in the literary traditions of the Sinosphere—most prominently in Culture of Japan, Japan as well as certain periods of Chinese history, Joseon Korea, and Vietnam. They tend to offer a reflectio ...

, were in verse, addressed to the dagger with which he took his own life:

When Hideyoshi was building his lavish residence at Fushimi the following year, he remarked that he wished its construction and decoration to be pleasing to Rikyū. Hideyoshi was known for his temper, and is said to have expressed regret at his treatment of Rikyū.Sansom, George (1961). "A History of Japan: 1334-1615." Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. pp364,370.

Rikyū's grave is located at Jukōin temple in the Daitoku-ji

is a Rinzai school Zen Buddhist temple in the Murasakino neighborhood of Kita-ku in the city of Kyoto Japan. Its ('' sangō'') is . The Daitoku-ji temple complex is one of the largest Zen temples in Kyoto, covering more than . In addition to ...

compound in Kyoto; his posthumous Buddhist name is Fushin'an Rikyū Sōeki Koji.

Memorials for Rikyū are observed annually by many schools of Japanese tea ceremony. The Omotesenke school's annual memorial takes place at the family's headquarters each year on March 27, and the Urasenke school's takes place at its own family's headquarters each year on March 28. The three Sen families (Omotesenke, Urasenke, Mushakōjisenke) take turns holding a memorial service on the 28th of every month, at their mutual family temple, the subsidiary temple Jukōin at Daitoku-ji temple.

Rikyū's Seven High-Status Disciples

The () ('Seven Foremost Disciples', 'Seven Luminaries') is a set of seven high-rankingdaimyō

were powerful Japanese magnates, feudal lords who, from the 10th century to the early Meiji era, Meiji period in the middle 19th century, ruled most of Japan from their vast hereditary land holdings. They were subordinate to the shogun and no ...

or generals who were also direct disciples of Sen no Rikyū: Maeda Toshinaga, Gamō Ujisato, Hosokawa Tadaoki, Furuta Oribe, Makimura Toshisada, Dom Justo Takayama, and Shibayama Munetsuna. The seven-member set was first mentioned by Rikyū's grandson Sen no Sōtan. In a 1663 list given by Sōtan's son (and fourth-generation head of the Sen Sōsa lineage of tea masters), Maeda Toshinaga is replaced by Seta Masatada.

See also

* Sen Shōan * Sen Sōtan * Schools of Japanese tea ceremonyNotes

References

* Bodart-Bailey, Beatrice. (1977). ''Tea and counsel, the political rele of Sen Rikyū.''OCLC 469293854

* Sansom, George Bailey. (1961). ''A History of Japan: 1334-1615.'' London: Cresset Press

OCLC 216583509

Further reading

* Tanaka, Seno, Tanaka, Sendo, Reischauer, Edwin O. “The Tea Ceremony”, Kodansha International; Revised edition, May 1, 2000. , .External links

Momoyama, Japanese Art in the Age of Grandeur

an exhibition catalog from The Metropolitan Museum of Art (fully available online as PDF), which contains material on Sen no Rikyū

Turning point : Oribe and the arts of sixteenth-century Japan

an exhibition catalog from The Metropolitan Museum of Art (fully available online as PDF), which contains material on Sen no Rikyū {{DEFAULTSORT:Sen no, Rikyu 1522 births 1591 deaths Japanese tea masters Male suicides Suicides by seppuku People from Sakai, Osaka Forced suicides 16th-century suicides Japanese Rinzai Zen Buddhists Buddhist clergy of Muromachi-period Japan Clergy of the Azuchi–Momoyama period