Selma, AL on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Selma is a city in and the

On March 30, 1865, Union General James H. Wilson detached Gen.

On March 30, 1865, Union General James H. Wilson detached Gen.  Early the next morning, Forrest reached Selma; he advised Gen. Richard Taylor, departmental commander, to leave the city. Taylor did so after giving Forrest command of the defense. Selma was protected by fortifications that circled much of the city; it was protected on the north and south by the

Early the next morning, Forrest reached Selma; he advised Gen. Richard Taylor, departmental commander, to leave the city. Taylor did so after giving Forrest command of the defense. Selma was protected by fortifications that circled much of the city; it was protected on the north and south by the  The Federals suffered many casualties (including General Long) but continued their attack. Once the Union Army reached the works, there was vicious hand-to-hand fighting. Many soldiers were struck down with clubbed muskets, but they kept pouring into the works with their greater numbers. In less than 30 minutes, Long's men had captured the works protecting the Summerfield Road.

Meanwhile, General Upton, observing Long's success, ordered his division forward. They succeeded in overmounting the defenses and soon U.S. flags could be seen waving over the works from Range Line Road to Summerfield Road.

After the outer works fell, General Wilson led the

The Federals suffered many casualties (including General Long) but continued their attack. Once the Union Army reached the works, there was vicious hand-to-hand fighting. Many soldiers were struck down with clubbed muskets, but they kept pouring into the works with their greater numbers. In less than 30 minutes, Long's men had captured the works protecting the Summerfield Road.

Meanwhile, General Upton, observing Long's success, ordered his division forward. They succeeded in overmounting the defenses and soon U.S. flags could be seen waving over the works from Range Line Road to Summerfield Road.

After the outer works fell, General Wilson led the

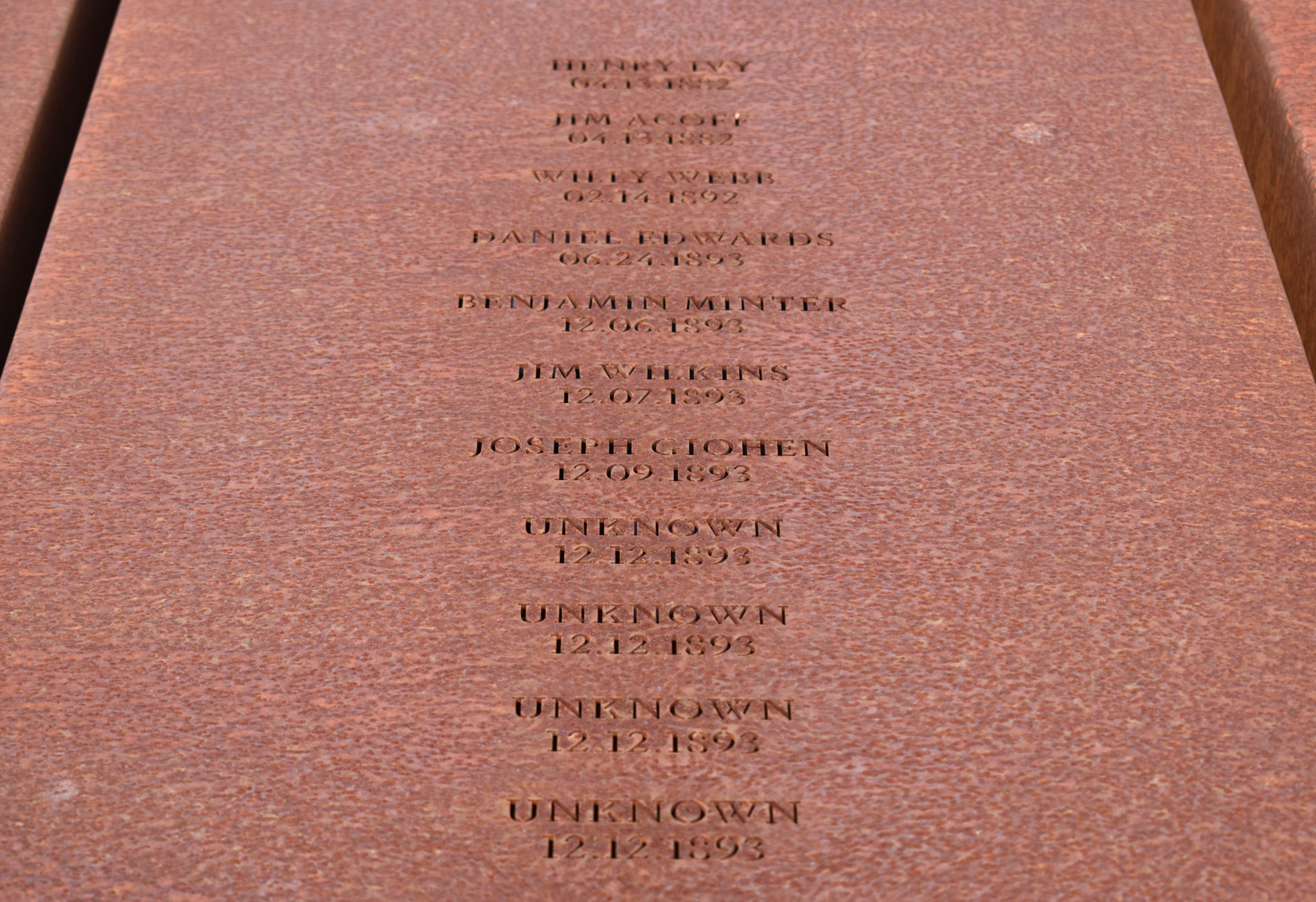

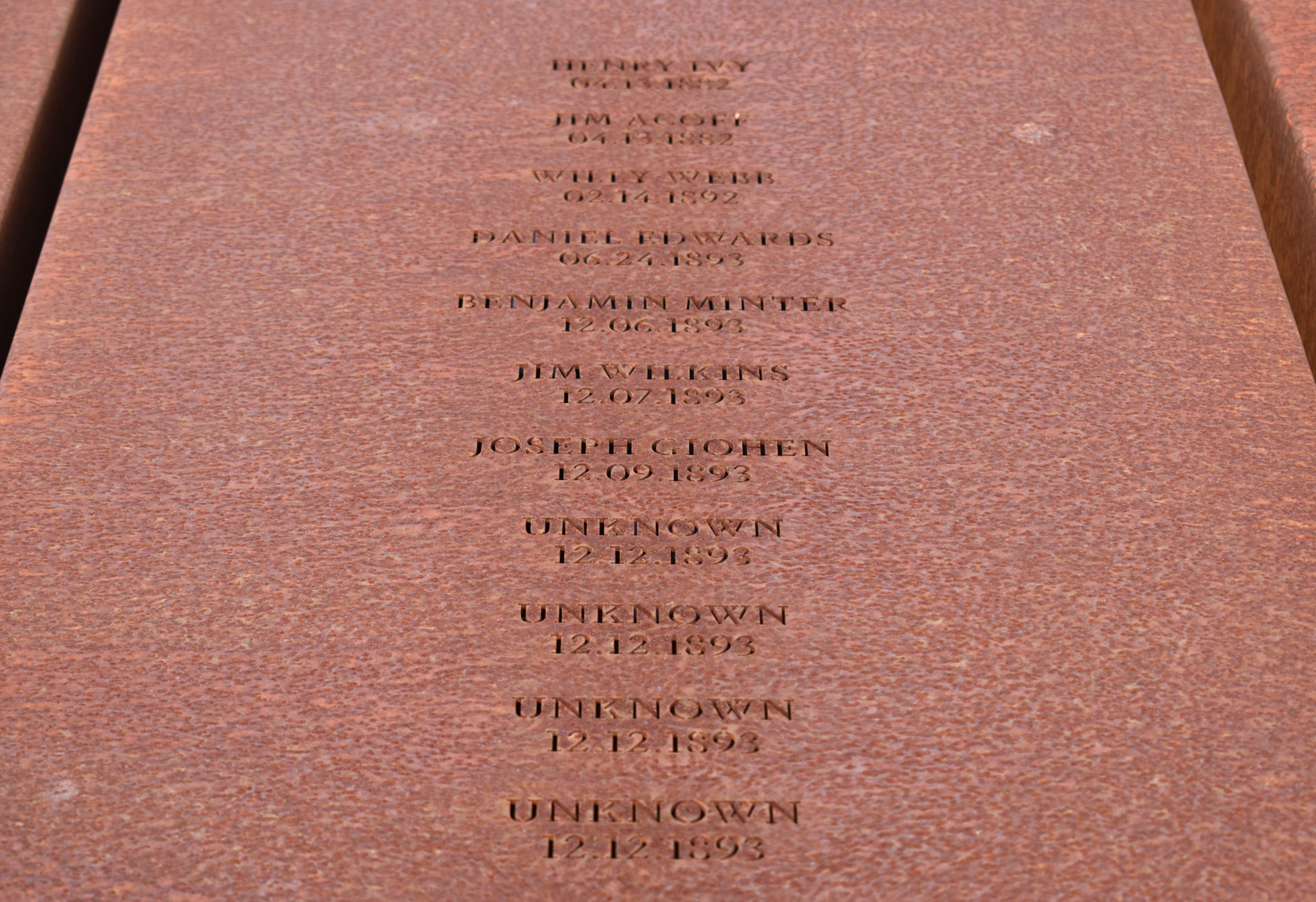

The city developed its own police force. County law enforcement was run by an elected county sheriff, whose jurisdiction included the grounds of the county courthouse. The county courthouse and jail were scenes of numerous lynchings of African-Americans, as sometimes mobs would take prisoners from the jail and hang them before trial. In February 1892, Willy Webb was put in the jail in Selma after police arrested him in Waynesville. The police intended to save Webb from a local lynch mob, but the mob abducted Webb from the jail and killed him. In June 1893, a lynch mob numbering 100 men seized "a black man named Daniel Edwards from the Selma jail, hanged him from a tree, and fired multiple rounds into his body" for allegedly becoming intimate with a white woman. In the 20th century, African-Americans were also lynched for labor-organizing activities. In 1935, Joe Spinner Johnson, a leader of the Alabama Sharecroppers Union, which worked from 1931 to 1936 to get better pay and treatment from white planters, was beaten by a mob near his field, taken to the jail in Selma and beaten more; his body was left in a field near

The city developed its own police force. County law enforcement was run by an elected county sheriff, whose jurisdiction included the grounds of the county courthouse. The county courthouse and jail were scenes of numerous lynchings of African-Americans, as sometimes mobs would take prisoners from the jail and hang them before trial. In February 1892, Willy Webb was put in the jail in Selma after police arrested him in Waynesville. The police intended to save Webb from a local lynch mob, but the mob abducted Webb from the jail and killed him. In June 1893, a lynch mob numbering 100 men seized "a black man named Daniel Edwards from the Selma jail, hanged him from a tree, and fired multiple rounds into his body" for allegedly becoming intimate with a white woman. In the 20th century, African-Americans were also lynched for labor-organizing activities. In 1935, Joe Spinner Johnson, a leader of the Alabama Sharecroppers Union, which worked from 1931 to 1936 to get better pay and treatment from white planters, was beaten by a mob near his field, taken to the jail in Selma and beaten more; his body was left in a field near

In the 1960s, black people who pushed the boundaries, attempting to eat at "white-only" lunch counters or sit in the downstairs "white" section of movie theaters, were still beaten and arrested. Nearly half of Selma's residents were black, but because of the restrictive electoral laws and practices in place since the turn of the century, only one percent were registered to vote, preventing them from serving on juries or serving in local office. All the members of the city council were elected by

In the 1960s, black people who pushed the boundaries, attempting to eat at "white-only" lunch counters or sit in the downstairs "white" section of movie theaters, were still beaten and arrested. Nearly half of Selma's residents were black, but because of the restrictive electoral laws and practices in place since the turn of the century, only one percent were registered to vote, preventing them from serving on juries or serving in local office. All the members of the city council were elected by  Against fierce opposition from Dallas County Sheriff

Against fierce opposition from Dallas County Sheriff

Activists planned a larger, more public march from Selma to the state capital of Montgomery to publicize their cause. It was initiated and organized by

Activists planned a larger, more public march from Selma to the state capital of Montgomery to publicize their cause. It was initiated and organized by  On Sunday, March 21, 1965, approximately 3,200 marchers departed for Montgomery. Marching in the front row with King were Rev.

On Sunday, March 21, 1965, approximately 3,200 marchers departed for Montgomery. Marching in the front row with King were Rev.

''The Nation'', February 25, 2015. Retrieved March 12, 2015

Cultural events are held at the Performing Arts Center, and the Selma Art Guild Gallery.

Cultural events are held at the Performing Arts Center, and the Selma Art Guild Gallery.

The complex history is reflected in naming and monuments as well. Highway 80, which runs east and west through Selma and the state has reflected this in naming patterns. In 1920 the east-west Highway 80 was designated as part of the Jefferson Davis Memorial Highway. In 1977 US 80 was named Givhan Parkway in honor of the long-serving state senator Walter C. Givhan, a segregationist to the end. In 1996 it was designated as part of the 'National Civil Rights Trail' by President Bill Clinton and is administered by the National Park Service. In 2000 sections of Highway 80 leading into Selma were renamed in honor of leaders in the Selma Voting Rights Movement:

The complex history is reflected in naming and monuments as well. Highway 80, which runs east and west through Selma and the state has reflected this in naming patterns. In 1920 the east-west Highway 80 was designated as part of the Jefferson Davis Memorial Highway. In 1977 US 80 was named Givhan Parkway in honor of the long-serving state senator Walter C. Givhan, a segregationist to the end. In 1996 it was designated as part of the 'National Civil Rights Trail' by President Bill Clinton and is administered by the National Park Service. In 2000 sections of Highway 80 leading into Selma were renamed in honor of leaders in the Selma Voting Rights Movement:

''The Crime Report'', February 2, 2015. Retrieved March 14, 2015

The Selma-Dallas County Public Library serves the city and the region with a collection of 76,751 volumes. It was established as a Carnegie library in 1904, receiving matching funds for construction. The library is in downtown Selma.

The Selma-Dallas County Public Library serves the city and the region with a collection of 76,751 volumes. It was established as a Carnegie library in 1904, receiving matching funds for construction. The library is in downtown Selma.

The city government of Selma consists of a mayor and a nine-member

The city government of Selma consists of a mayor and a nine-member

The official website of Selma, Alabama

Selma-Dallas County Chamber of Commerce

Selma-Dallas County Public Library

{{Authority control Populated places established in 1820 1820 establishments in Alabama Cities in Alabama Cities in Dallas County, Alabama Micropolitan areas of Alabama County seats in Alabama

county seat

A county seat is an administrative center, seat of government, or capital city of a county or civil parish. The term is in use in Canada, China, Hungary, Romania, Taiwan, and the United States. The equivalent term shire town is used in the US ...

of Dallas County, in the Black Belt region of south central Alabama

(We dare defend our rights)

, anthem = " Alabama"

, image_map = Alabama in United States.svg

, seat = Montgomery

, LargestCity = Huntsville

, LargestCounty = Baldwin County

, LargestMetro = Greater Birmingham

, area_total_km2 = 135,7 ...

and extending to the west. Located on the banks of the Alabama River

The Alabama River, in the U.S. state of Alabama, is formed by the Tallapoosa and Coosa rivers, which unite about north of Montgomery, near the town of Wetumpka.

The river flows west to Selma, then southwest until, about from Mobile, it ...

, the city has a population of 17,971 as of the 2020 census. About 80% of the population is African-American.

Selma was a trading center and market town during the antebellum

Antebellum, Latin for "before war", may refer to:

United States history

* Antebellum South, the pre-American Civil War period in the Southern United States

** Antebellum Georgia

** Antebellum South Carolina

** Antebellum Virginia

* Antebellum arc ...

years of King Cotton

"King Cotton" is a slogan that summarized the strategy used before the American Civil War (of 1861–1865) by secessionists in the southern states (the future Confederate States of America) to claim the feasibility of Secession in the United Sta ...

in the South. It was also an important armaments-manufacturing and iron shipbuilding center for the Confederacy

Confederacy or confederate may refer to:

States or communities

* Confederate state or confederation, a union of sovereign groups or communities

* Confederate States of America, a confederation of secessionist American states that existed between ...

during the Civil War

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government polic ...

, surrounded by miles of earthen fortifications. The Confederate forces were defeated during the Battle of Selma

The Battle of Selma, Alabama (April 2, 1865), formed part of the Union campaign through Alabama and Georgia, known as Wilson's Raid, in the final full month of the American Civil War.

Union Army forces under Major General James H. Wilson, tot ...

, in the final full month of the war.

In modern times, the city is best known for the 1960s civil rights movement

The civil rights movement was a nonviolent social and political movement and campaign from 1954 to 1968 in the United States to abolish legalized institutional Racial segregation in the United States, racial segregation, Racial discrimination ...

and the Selma to Montgomery marches

The Selma to Montgomery marches were three Demonstration (protest), protest marches, held in 1965, along the 54-mile (87 km) highway from Selma, Alabama, to the state capital of Montgomery, Alabama, Montgomery. The marches were organized ...

, beginning with "Bloody Sunday" in 1965 and ending with 25,000 people entering Montgomery at the end of the last march to press for voting rights. This activism generated national attention for social justice and that summer, the Voting Rights Act of 1965

The suffrage, Voting Rights Act of 1965 is a landmark piece of Federal government of the United States, federal legislation in the United States that prohibits racial discrimination in voting. It was signed into law by President of the United ...

was passed by Congress to authorize federal oversight and enforcement of constitutional rights of all American citizens.

Due to agriculture and industry decline, Selma has lost about a third of its peak population in the 1960s. The city now is focusing its income on tourism for its major influence in civil rights and desegregation. Selma is also one of Alabama's poorest cities with an average income of $35,500, which is 30% less than the state average. Selma also has a high poverty rate with one in every three residents in Selma living below state poverty line

The poverty threshold, poverty limit, poverty line or breadline is the minimum level of income deemed adequate in a particular country. The poverty line is usually calculated by estimating the total cost of one year's worth of necessities for ...

.

History

Before discovery and settlement, the area of present-day Selma had been inhabited for thousands of years by various warring tribes of Native Americans. The Europeans encountered the historic Native American people known as theMuscogee

The Muscogee, also known as the Mvskoke, Muscogee Creek, and the Muscogee Creek Confederacy ( in the Muscogee language), are a group of related indigenous peoples of the Southeastern Woodlands, indigenous (Native American) peoples of the Southe ...

(also known as the Creek), who had been in the area for hundreds of years.

French explorers and colonists were the first Europeans to explore this area. In 1732, they recorded the site of present-day Selma as ''Écor Bienville.'' Later Anglo-Americans called it the Moore's Bluff settlement. Selma was incorporated in 1820. The city was planned and named as Selma by William R. King, a politician and planter from North Carolina

North Carolina () is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States. The state is the 28th largest and 9th-most populous of the United States. It is bordered by Virginia to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the east, Georgia a ...

who was a future vice president of the United States. The name, meaning 'high seat' or 'throne', came from the Ossian

Ossian (; Irish Gaelic/Scottish Gaelic: ''Oisean'') is the narrator and purported author of a cycle of epic poems published by the Scottish poet James Macpherson, originally as ''Fingal'' (1761) and ''Temora'' (1763), and later combined under ...

ic poem ''The Songs of Selma''.

Selma during the Civil War

During theCivil War

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government polic ...

, Selma was one of the South's main military manufacturing centers, producing many supplies and munitions, and building Confederate warships such as the ironclad

An ironclad is a steam engine, steam-propelled warship protected by Wrought iron, iron or steel iron armor, armor plates, constructed from 1859 to the early 1890s. The ironclad was developed as a result of the vulnerability of wooden warships ...

''Tennessee''. The Selma iron works and foundry, where a young William Kehoe

William Kehoe (September 12, 1876 – September 17, 1932) was an American lawyer and politician.

Biography

William Kehoe was born in Greenwood (now Elk), California on September 12, 1876. He earned a degree at the University of Michigan and w ...

made bullets, was considered the second-most important source of weaponry for the South, after the Tredegar Iron Works

The Tredegar Iron Works in Richmond, Virginia, was the biggest ironworks in the Confederacy during the American Civil War, and a significant factor in the decision to make Richmond its capital.

Tredegar supplied about half the artillery used by ...

in Richmond, Virginia

(Thus do we reach the stars)

, image_map =

, mapsize = 250 px

, map_caption = Location within Virginia

, pushpin_map = Virginia#USA

, pushpin_label = Richmond

, pushpin_m ...

. This strategic concentration of manufacturing capabilities eventually made Selma a target of Union raids into Alabama late in the Civil War

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government polic ...

.

Because of its military importance, Selma had been fortified by three miles of earthworks that ran in a semicircle around the city. They were anchored on the north and south by the Alabama River

The Alabama River, in the U.S. state of Alabama, is formed by the Tallapoosa and Coosa rivers, which unite about north of Montgomery, near the town of Wetumpka.

The river flows west to Selma, then southwest until, about from Mobile, it ...

. The works had been built two years earlier, and while neglected for the most part since, were still formidable. They were to high, thick at the base, with a ditch wide and deep along the front. In front of this was a -high picket fence of heavy posts planted in the ground and sharpened at the top. At prominent positions, earthen forts were built with artillery in position to cover the ground over which an assault would have to be made.

The North had learned of the importance of Selma to the Confederate military, and the US military planned to take the city. Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman

William Tecumseh Sherman ( ; February 8, 1820February 14, 1891) was an American soldier, businessman, educator, and author. He served as a general in the Union Army during the American Civil War (1861–1865), achieving recognition for his com ...

first made an effort to reach it, but after advancing from the west as far as Meridian, Mississippi

Meridian is the seventh largest city in the U.S. state of Mississippi, with a population of 41,148 at the 2010 census and an estimated population in 2018 of 36,347. It is the county seat of Lauderdale County and the principal city of the Meri ...

, within of Selma, his forces retreated back to the Mississippi River. Gen. Benjamin Grierson

Benjamin Henry Grierson (July 8, 1826 – August 31, 1911) was a music teacher, then a career officer in the United States Army. He was a cavalry general in the volunteer Union Army during the Civil War and later led troops in the American ...

, invading with a cavalry force from Memphis, Tennessee

Memphis is a city in the U.S. state of Tennessee. It is the County seat, seat of Shelby County, Tennessee, Shelby County in the southwest part of the state; it is situated along the Mississippi River. With a population of 633,104 at the 2020 Uni ...

, was intercepted and returned. Gen. Rousseau made a dash in the direction of Selma, but was misled by his guides and struck the railroad forty miles east of Montgomery.

Battle of Selma

On March 30, 1865, Union General James H. Wilson detached Gen.

On March 30, 1865, Union General James H. Wilson detached Gen. John T. Croxton

John Thomas Croxton (November 20, 1836 – April 16, 1874) was an attorney, a general in the United States Army during the American Civil War, and a postbellum U.S. diplomat.

Early life and career

Croxton was born near Paris, Kentucky, in rur ...

's brigade to destroy all Confederate property at Tuscaloosa

Tuscaloosa ( ) is a city in and the seat of Tuscaloosa County in west-central Alabama, United States, on the Black Warrior River where the Gulf Coastal and Piedmont plains meet. Alabama's fifth-largest city, it had an estimated population of 10 ...

. Wilson's forces captured a Confederate courier, who was found to be carrying dispatches from Confederate General Nathan Bedford Forrest

Nathan Bedford Forrest (July 13, 1821October 29, 1877) was a prominent Confederate Army general during the American Civil War and the first Grand Wizard of the Ku Klux Klan from 1867 to 1869. Before the war, Forrest amassed substantial wealth ...

describing his scattered forces. Wilson sent a brigade to destroy the bridge across the Cahaba River at Centreville, which cut off most of Forrest's reinforcements from reaching the area. He began a running fight with Forrest's forces that did not end until after the fall of Selma.

On the afternoon of April 1, opening what would be the final full month of the war, and after skirmishing

Skirmishers are light infantry or light cavalry soldiers deployed as a vanguard, flank guard or rearguard to screen a tactical position or a larger body of friendly troops from enemy advances. They are usually deployed in a skirmish line, an i ...

all morning, Wilson's advanced guard ran into Forrest's line of battle at Ebenezer Church, where the Randolph Road intersected the main Selma road. Forrest had hoped to bring his entire force to bear on Wilson. Delays caused by flooding, plus earlier contact with the enemy, resulted in Forrest's mustering fewer than 2,000 men, many of whom were not war veterans but home militia consisting of old men and young boys.

The outnumbered and outgunned Confederates fought for more than an hour as reinforcements of Union cavalry and artillery were deployed. Forrest was wounded by a saber-wielding Union captain, whom he shot and killed with his revolver. Finally, a Union cavalry charge broke the Confederate militia, causing Forrest to be flanked on his right. He was forced to retreat.

Early the next morning, Forrest reached Selma; he advised Gen. Richard Taylor, departmental commander, to leave the city. Taylor did so after giving Forrest command of the defense. Selma was protected by fortifications that circled much of the city; it was protected on the north and south by the

Early the next morning, Forrest reached Selma; he advised Gen. Richard Taylor, departmental commander, to leave the city. Taylor did so after giving Forrest command of the defense. Selma was protected by fortifications that circled much of the city; it was protected on the north and south by the Alabama River

The Alabama River, in the U.S. state of Alabama, is formed by the Tallapoosa and Coosa rivers, which unite about north of Montgomery, near the town of Wetumpka.

The river flows west to Selma, then southwest until, about from Mobile, it ...

. The wall was high and deep, surrounded by a ditch and picket fence. Earthen forts were built to cover the grounds with artillery fire.

Forrest's defenders consisted of his Tennessee escort company, McCullough's Missouri Regiment, Crossland's Kentucky Brigade, Roddey's Alabama Brigade, Frank Armstrong's Mississippi Brigade, General Daniel W. Adams' state reserves, and the citizens of Selma who were "volunteered" to man the works. Altogether this force numbered less than 4,000. As the Selma fortifications were built to be defended by 20,000 men, Forrest's soldiers had to stand 10 to apart to try to cover the works.

Wilson's force arrived in front of the Selma fortifications at 2 pm. He had placed Gen. Eli Long's Division across the Summerfield Road with the Chicago Board of Trade Battery in support. Gen. Emory Upton

Emory Upton (August 27, 1839 – March 15, 1881) was a United States Army General and military strategist, prominent for his role in leading infantry to attack entrenched positions successfully at the Battle of Spotsylvania Court House during the ...

's Division was placed across the Range Line Road with Battery I, 4th US Artillery in support. Altogether Wilson had 9,000 troops available for the assault.

The Federal commander's plan was for Upton to send in a 300-man detachment after dark to cross the swamp on the Confederate right; enter the works, and begin a flanking movement toward the center moving along the line of fortifications. A single gun from Upton's artillery would signal the attack to be undertaken by the entire Federal Corps.

At 5 pm, however, Gen. Eli Long

Eli Long (June 16, 1837 – January 5, 1903) was a general in the Union Army during the American Civil War.

Early life

Long was born on June 16, 1837, in Woodford County, Kentucky, and graduated from the Kentucky Military Institute in 1855.Eicher ...

's ammunition train in the rear was attacked by advance elements of Forrest's scattered forces approaching Selma. Both Long and Upton had positioned significant numbers of troops in their rear for just such an event. But, Long decided to begin his assault against the Selma fortifications to neutralize the enemy attack in his rear.

Long's troops attacked in a single rank in three main lines, dismounted and shooting their Spencer's carbines, supported by their own artillery fire. The Confederates replied with heavy small arms and artillery fire. The Southern artillery had only solid shot on hand, while a short distance away was an arsenal which produced tons of canister, a highly effective anti-personnel ammunition.

The Federals suffered many casualties (including General Long) but continued their attack. Once the Union Army reached the works, there was vicious hand-to-hand fighting. Many soldiers were struck down with clubbed muskets, but they kept pouring into the works with their greater numbers. In less than 30 minutes, Long's men had captured the works protecting the Summerfield Road.

Meanwhile, General Upton, observing Long's success, ordered his division forward. They succeeded in overmounting the defenses and soon U.S. flags could be seen waving over the works from Range Line Road to Summerfield Road.

After the outer works fell, General Wilson led the

The Federals suffered many casualties (including General Long) but continued their attack. Once the Union Army reached the works, there was vicious hand-to-hand fighting. Many soldiers were struck down with clubbed muskets, but they kept pouring into the works with their greater numbers. In less than 30 minutes, Long's men had captured the works protecting the Summerfield Road.

Meanwhile, General Upton, observing Long's success, ordered his division forward. They succeeded in overmounting the defenses and soon U.S. flags could be seen waving over the works from Range Line Road to Summerfield Road.

After the outer works fell, General Wilson led the 4th U.S. Cavalry

The 4th Cavalry Regiment is a United States Army cavalry regiment, whose lineage is traced back to the mid-19th century. It was one of the most effective units of the Army against American Indians on the Texas frontier. Today, the regiment ex ...

Regiment in a mounted charge down the Range Line Road toward the unfinished inner line of works. The retreating Confederate forces, upon reaching the inner works, united and fired repeatedly together into the charging column. This broke up the charge and sent General Wilson sprawling to the ground when his favorite horse was wounded. He quickly remounted his stricken horse and ordered a dismounted assault by several regiments.

Mixed units of Confederate troops had also occupied the Selma railroad depot and the adjoining banks of the railroad bed to make a stand next to the Plantersville Road (present day Broad Street). The fighting there was heavy, but by 7 p.m. the superior numbers of Union troops had managed to flank the Southern positions. The Confederates abandoned the depot as well as the inner line of works.

In the darkness, the Federals rounded up hundreds of prisoners, but hundreds more escaped down the Burnsville Road, including generals Forrest, Armstrong, and Roddey. To the west, many Confederate soldiers fought the pursuing Union Army all the way down to the eastern side of Valley Creek. They escaped in the darkness by swimming across the Alabama River near the mouth of Valley Creek (where the present day Battle of Selma Reenactment is held.)

The Union troops looted the city that night and burned many businesses and private residences. They spent the next week destroying the arsenal and naval foundry. They left Selma heading to Montgomery. When the war ended three weeks later, they were en route to Columbus

Columbus is a Latinized version of the Italian surname "''Colombo''". It most commonly refers to:

* Christopher Columbus (1451-1506), the Italian explorer

* Columbus, Ohio, capital of the U.S. state of Ohio

Columbus may also refer to:

Places ...

and Macon, Georgia.

Post-war period

Selma became the seat of Dallas County in 1866 and the county courthouse was built there. Planters and other slaveholders struggled with how to deal with freed slaves after the war. Insurgents tried to keepwhite supremacy

White supremacy or white supremacism is the belief that white people are superior to those of other races and thus should dominate them. The belief favors the maintenance and defense of any power and privilege held by white people. White s ...

over the freedmen

A freedman or freedwoman is a formerly enslaved person who has been released from slavery, usually by legal means. Historically, enslaved people were freed by manumission (granted freedom by their captor-owners), abolitionism, emancipation (gra ...

, and most whites resented former slaves being granted the right to vote. As in other southern states, white Democrats regained political power in the mid-1870s after suppressing black voting through violence and fraud; Reconstruction officially ended in 1877 when federal troops were withdrawn. The white Democratic state legislature imposed Jim Crow laws

The Jim Crow laws were state and local laws enforcing racial segregation in the Southern United States. Other areas of the United States were affected by formal and informal policies of segregation as well, but many states outside the Sou ...

of racial segregation

Racial segregation is the systematic separation of people into racial or other ethnic groups in daily life. Racial segregation can amount to the international crime of apartheid and a crime against humanity under the Statute of the Intern ...

in public facilities and other means of white supremacy.

The city developed its own police force. County law enforcement was run by an elected county sheriff, whose jurisdiction included the grounds of the county courthouse. The county courthouse and jail were scenes of numerous lynchings of African-Americans, as sometimes mobs would take prisoners from the jail and hang them before trial. In February 1892, Willy Webb was put in the jail in Selma after police arrested him in Waynesville. The police intended to save Webb from a local lynch mob, but the mob abducted Webb from the jail and killed him. In June 1893, a lynch mob numbering 100 men seized "a black man named Daniel Edwards from the Selma jail, hanged him from a tree, and fired multiple rounds into his body" for allegedly becoming intimate with a white woman. In the 20th century, African-Americans were also lynched for labor-organizing activities. In 1935, Joe Spinner Johnson, a leader of the Alabama Sharecroppers Union, which worked from 1931 to 1936 to get better pay and treatment from white planters, was beaten by a mob near his field, taken to the jail in Selma and beaten more; his body was left in a field near

The city developed its own police force. County law enforcement was run by an elected county sheriff, whose jurisdiction included the grounds of the county courthouse. The county courthouse and jail were scenes of numerous lynchings of African-Americans, as sometimes mobs would take prisoners from the jail and hang them before trial. In February 1892, Willy Webb was put in the jail in Selma after police arrested him in Waynesville. The police intended to save Webb from a local lynch mob, but the mob abducted Webb from the jail and killed him. In June 1893, a lynch mob numbering 100 men seized "a black man named Daniel Edwards from the Selma jail, hanged him from a tree, and fired multiple rounds into his body" for allegedly becoming intimate with a white woman. In the 20th century, African-Americans were also lynched for labor-organizing activities. In 1935, Joe Spinner Johnson, a leader of the Alabama Sharecroppers Union, which worked from 1931 to 1936 to get better pay and treatment from white planters, was beaten by a mob near his field, taken to the jail in Selma and beaten more; his body was left in a field near Greensboro

Greensboro (; formerly Greensborough) is a city in and the county seat of Guilford County, North Carolina, United States. It is the third-most populous city in North Carolina after Charlotte and Raleigh, the 69th-most populous city in th ...

.

Twentieth century

In 1901, the state legislature passed a new constitution with electoral provisions, such aspoll taxes

A poll tax, also known as head tax or capitation, is a tax levied as a fixed sum on every liable individual (typically every adult), without reference to income or resources.

Head taxes were important sources of revenue for many governments f ...

and literacy tests

A literacy test assesses a person's literacy skills: their ability to read and write have been administered by various governments, particularly to immigrants. In the United States, between the 1850s and 1960s, literacy tests were administered t ...

, that effectively disenfranchised most blacks and tens of thousands of poor whites, leaving them without representation in government, and deprived them of participation in juries and other forms of citizenship. Selma, Dallas County and other jurisdictions carried out the segregation laws passed by the state.

Especially in the post-World War II period, legal challenges by the NAACP

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) is a civil rights organization in the United States, formed in 1909 as an interracial endeavor to advance justice for African Americans by a group including W. E.&nb ...

against Southern discriminatory laws enabled blacks to more freely exercise their constitutional rights as citizens.

Selma Voting Rights Movement

Selma maintained segregated schools and other facilities, enforcing the state law in new enterprises such as movie theaters. The Jim Crow laws and customs were enforced with violence. In the 1960s, black people who pushed the boundaries, attempting to eat at "white-only" lunch counters or sit in the downstairs "white" section of movie theaters, were still beaten and arrested. Nearly half of Selma's residents were black, but because of the restrictive electoral laws and practices in place since the turn of the century, only one percent were registered to vote, preventing them from serving on juries or serving in local office. All the members of the city council were elected by

In the 1960s, black people who pushed the boundaries, attempting to eat at "white-only" lunch counters or sit in the downstairs "white" section of movie theaters, were still beaten and arrested. Nearly half of Selma's residents were black, but because of the restrictive electoral laws and practices in place since the turn of the century, only one percent were registered to vote, preventing them from serving on juries or serving in local office. All the members of the city council were elected by at-large

At large (''before a noun'': at-large) is a description for members of a governing body who are elected or appointed to represent a whole membership or population (notably a city, county, state, province, nation, club or association), rather than ...

voting. Black people were prevented from registering to vote by means of a literacy test

A literacy test assesses a person's literacy skills: their ability to read and write have been administered by various governments, particularly to immigrants. In the United States, between the 1850s and 1960s, literacy tests were administered ...

, administered in a subjective way, as well as through economic retaliation organized by the White Citizens' Council in response to civil rights activism, Ku Klux Klan

The Ku Klux Klan (), commonly shortened to the KKK or the Klan, is an American white supremacist, right-wing terrorist, and hate group whose primary targets are African Americans, Jews, Latinos, Asian Americans, Native Americans, and Ca ...

violence and police repression. After the Supreme Court case '' Smith v. Allwright'' (1944) ended the use of white primaries

White primaries were primary elections held in the Southern United States in which only white voters were permitted to participate. Statewide white primaries were established by the state Democratic Party units or by state legislatures in South Car ...

by the Democratic Party, the Alabama state legislature passed a law giving voting registrars more authority to challenge prospective voters under the literacy test. In Selma, the county registration board opened doors for registration only two days a month, arrived late and took long lunches.

In early 1963, Bernard Lafayette

use both this parameter and , birth_date to display the person's date of birth, date of death, and age at death) -->

, death_place =

, death_cause =

, body_discovered =

, resting_place =

, resting_place_coordinates = ...

and Colia Lafayette of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee

The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC, often pronounced ) was the principal channel of student commitment in the United States to the civil rights movement during the 1960s. Emerging in 1960 from the student-led sit-ins at segreg ...

(SNCC) began organizing in Selma alongside local civil rights leaders Sam, Amelia and Bruce Boynton, Rev. L.L. Anderson of Tabernacle Baptist Church, J.L. Chestnut (Selma's first black attorney), SCLC Citizenship School teacher Marie Foster, public school teacher Marie Moore, Frederick D. Reese and others active with the Dallas County Voters League

The Dallas County Voters League (DCVL) was a local organization in Dallas County, Alabama, which contains the city of Selma, that sought to register black voters during the late 1950s and early 1960s.

The organization was founded in the 1920s b ...

(DCVL).

In 1963, under the leadership of Patricia Swift Blalock

Patricia Swift Blalock (May 9, 1914 – September 7, 2011) was an American librarian, social worker, and civil rights activist born in Gadsden, Alabama.

Blalock graduated from the University of Montevallo and studied social work at the University ...

, the public library of Selma-Dallas County was integrated.

Against fierce opposition from Dallas County Sheriff

Against fierce opposition from Dallas County Sheriff Jim Clark

James Clark Jr. OBE (4 March 1936 – 7 April 1968) was a British Formula One racing driver from Scotland, who won two World Championships, in 1963 and 1965. A versatile driver, he competed in sports cars, touring cars and in the Indianapol ...

and his volunteer posse, black people continued their voter registration and desegregation efforts, which expanded during 1963 and the first part of 1964. Defying intimidation, economic retaliation, arrests, firings and beatings, an ever-increasing number of Dallas County blacks tried to register to vote, but few were able to do so under the subjective system administered by whites.

In the summer of 1964, a sweeping injunction issued by local judge James Hare barred any gathering of three or more people under sponsorship of SNCC, SCLC or DCVL, or with the involvement of 41 named civil rights leaders. This injunction temporarily halted civil-rights activity until Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. defied it by speaking to a crowd about the struggle at Brown Chapel AME Church on January 2, 1965. He had been invited by local leaders to help their movement.

Beginning in January 1965, SCLC and SNCC initiated a revived voting-rights campaign designed to focus national attention on the systematic denial of black voting rights in Alabama, and particularly in Selma. Over the next weeks, more than 3,000 African-Americans were arrested, and they suffered police violence and economic retaliation. Jimmie Lee Jackson

Jimmie Lee Jackson (December 16, 1938 – February 26, 1965) was an African American civil rights activist in Marion, Alabama, and a deacon in the Baptist church. On February 18, 1965, while unarmed and participating in a peaceful voting righ ...

, who was unarmed, was killed in a café in nearby Marion after state police broke up a peaceful protest in the town.

Activists planned a larger, more public march from Selma to the state capital of Montgomery to publicize their cause. It was initiated and organized by

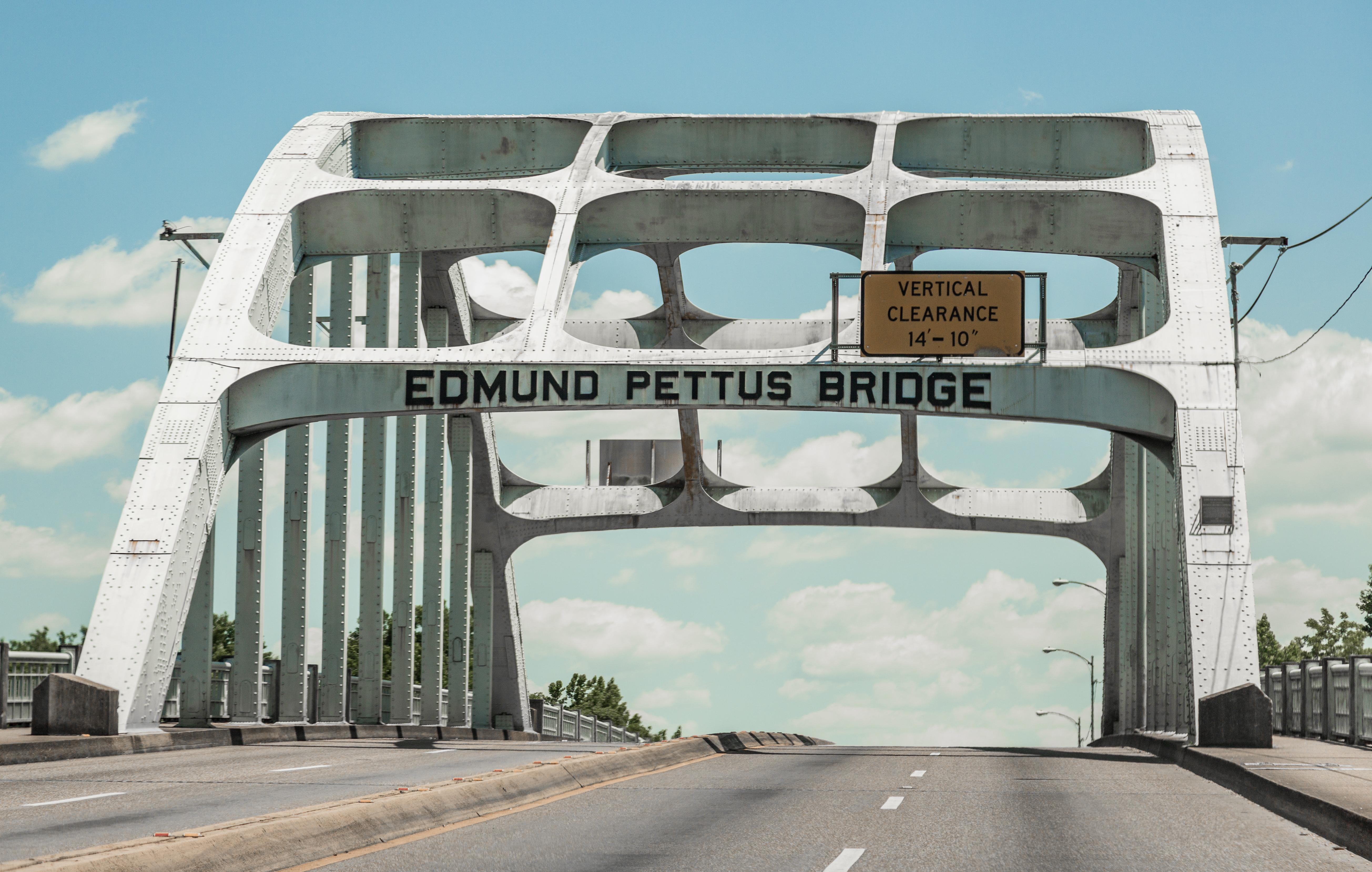

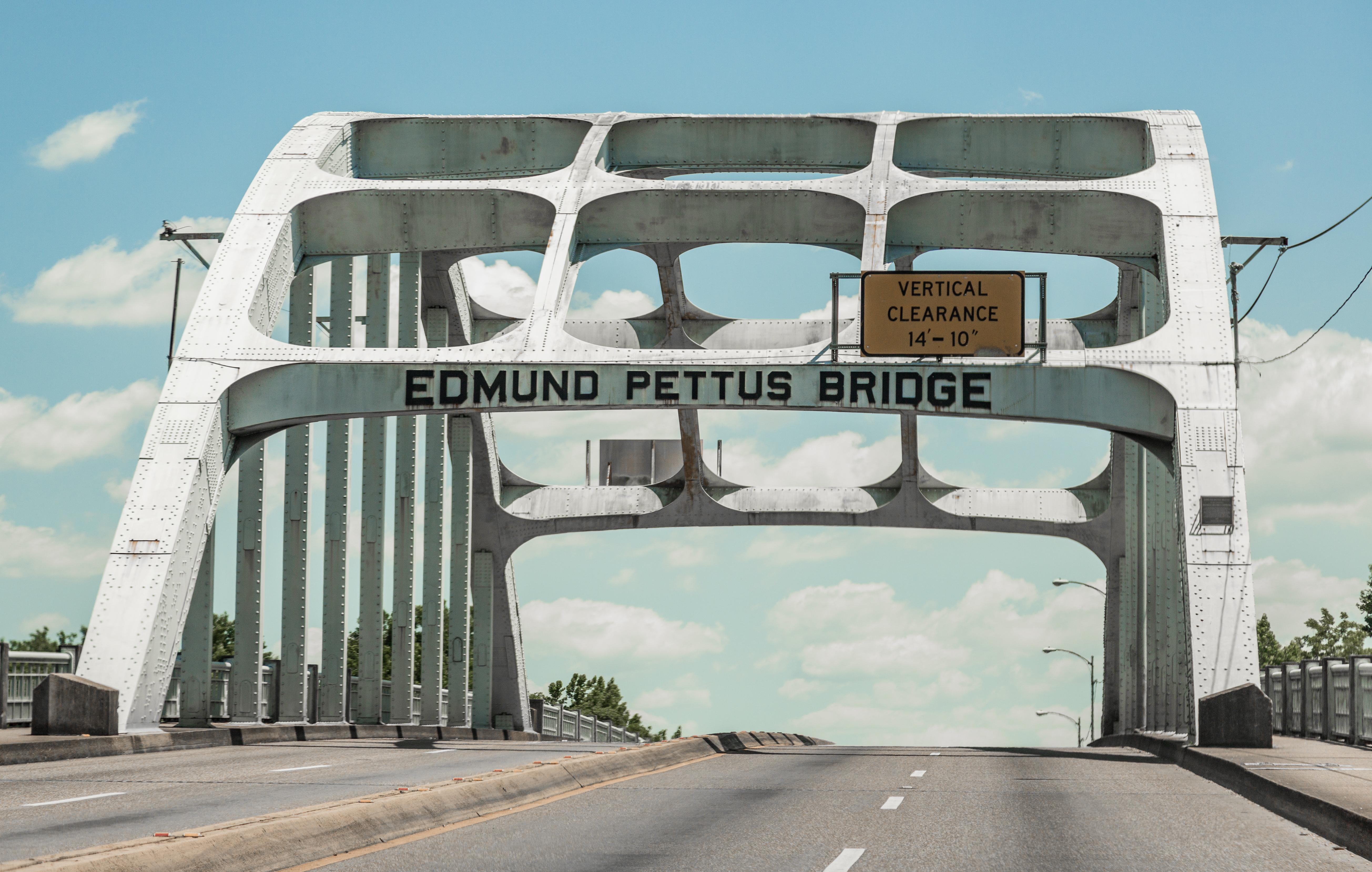

Activists planned a larger, more public march from Selma to the state capital of Montgomery to publicize their cause. It was initiated and organized by James Bevel

James Luther Bevel (October 19, 1936 – December 19, 2008) was a minister and leader of the 1960s Civil Rights Movement in the United States. As a member of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), and then as its Director of Direct ...

, SCLC's Director of Direct Action, who was directing SCLC's Selma Movement. This march represented one of the political and emotional peaks of the modern civil-rights movement. On March 7, 1965, approximately 600 civil rights marchers departed Selma on U.S. Highway 80, heading east to the capital. After they passed over the crest of the Edmund Pettus Bridge

The Edmund Pettus Bridge carries U.S. Route 80 Business (US 80 Bus.) across the Alabama River in Selma, Alabama. Built in 1940, it is named after Edmund Pettus, a former Confederate brigadier general, U.S. senator, and state-level l ...

and left the boundaries of the city, they were confronted by county sheriff's deputies and state troopers, who attacked them using tear gas

Tear gas, also known as a lachrymator agent or lachrymator (), sometimes colloquially known as "mace" after the early commercial aerosol, is a chemical weapon that stimulates the nerves of the lacrimal gland in the eye to produce tears. In ...

, horses and billy clubs, and drove them back across the bridge. Governor George Wallace

George Corley Wallace Jr. (August 25, 1919 – September 13, 1998) was an American politician who served as the 45th governor of Alabama for four terms. A member of the Democratic Party, he is best remembered for his staunch segregationist an ...

had vowed that the march would not be permitted. Seventeen marchers were hospitalized and 50 more were treated for lesser injuries. Because of the brutal attacks, this became known as "Bloody Sunday." It was covered by national press and television news, reaching many American and international homes.

Two days after the first march, on March 9, 1965, Martin Luther King, Jr. led a symbolic march over the bridge. By then local activists and residents had been joined by hundreds of protesters from across the country, including numerous clergy and nuns. White people made up one-third of the marchers. King pulled the marchers back from entering the county and having another confrontation with county and state forces. But that night, white minister James Reeb, who had traveled to the city from Boston, was attacked and killed in Selma by members of the KKK.

King and other civil-rights leaders filed for court protection for a third, larger-scale march from Selma to Montgomery, the state capital. King was also in touch with the administration of President Lyndon B. Johnson, who arranged for protection for another march. Frank Minis Johnson, Jr., the federal district court judge for the area who reviewed the injunction, decided in favor of the demonstrators, saying:

On Sunday, March 21, 1965, approximately 3,200 marchers departed for Montgomery. Marching in the front row with King were Rev.

On Sunday, March 21, 1965, approximately 3,200 marchers departed for Montgomery. Marching in the front row with King were Rev. Ralph Abernathy

Ralph David Abernathy Sr. (March 11, 1926 – April 17, 1990) was an American civil rights activist and Baptist minister. He was ordained in the Baptist tradition in 1948. As a leader of the civil rights movement, he was a close friend and ...

, Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel

Abraham Joshua Heschel (January 11, 1907 – December 23, 1972) was a Polish-born American rabbi and one of the leading Judaism, Jewish theologians and Jewish philosophers of the 20th century. Heschel, a professor of Jewish mysticism at the ...

, Greek Orthodox Father Iakovos (later Archbishop Iakovos of America

Archbishop Iakovos of North and South America ( el, Ιάκωβος; born Demetrios Koukouzis (Δημήτριος Κουκούζης); July 29, 1911 – April 10, 2005) was the primate of the Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of North and South America ...

) and Roman Catholic nuns. They walked approximately 12 miles a day and slept in nearby fields. The federal government provided protection in the form of National Guard

National Guard is the name used by a wide variety of current and historical uniformed organizations in different countries. The original National Guard was formed during the French Revolution around a cadre of defectors from the French Guards.

N ...

and military troops. Thousands joined the march along the way. By the time the marchers reached the capital four days later, on March 25, their strength had swelled to around 25,000 people. Their moral campaign had attracted thousands from across the country.

The events at Selma helped increase public support for the cause; later that year the U.S. Congress passed the Voting Rights Act of 1965

The suffrage, Voting Rights Act of 1965 is a landmark piece of Federal government of the United States, federal legislation in the United States that prohibits racial discrimination in voting. It was signed into law by President of the United ...

, a bill introduced, supported and signed by President Lyndon B. Johnson

Lyndon Baines Johnson (; August 27, 1908January 22, 1973), often referred to by his initials LBJ, was an American politician who served as the 36th president of the United States from 1963 to 1969. He had previously served as the 37th vice ...

. It provided for federal oversight and enforcement of voting rights for all citizens in state or jurisdictions where patterns of underrepresentation showed discrimination against certain populations such as ethnic minorities.

By March 1966, a year after the Selma-to-Montgomery marches, nearly 11,000 black people had registered to vote in Selma, where 12,000 white people were registered. Registration increased by November, when Wilson Baker was elected as Dallas County Sheriff to replace the notorious Jim Clark

James Clark Jr. OBE (4 March 1936 – 7 April 1968) was a British Formula One racing driver from Scotland, who won two World Championships, in 1963 and 1965. A versatile driver, he competed in sports cars, touring cars and in the Indianapol ...

.

However, seven years later, black people had not been able to elect a candidate of their choice to the city council. The council's members were elected at-large by the entire city, and the white majority had managed to control the elections. Threatened with a lawsuit under the Voting Rights Act, the council voted to adopt a system of electing its ten members from single-member districts. After the change, five African-American Democrats were elected to the city council, including activist Frederick Douglas Reese

Frederick Douglas Reese (November 28, 1929 – April 5, 2018) was an American civil rights activist, educator and minister from Selma, Alabama. Known as a member of Selma's "Courageous Eight", Reese was the president of the Dallas County Voters Le ...

, who became a major power in the city; five white people were also elected to the council.Ari Berman, "Fifty Years After Bloody Sunday in Selma, Everything and Nothing Has Changed"''The Nation'', February 25, 2015. Retrieved March 12, 2015

Geography

Selma is located at , west of Montgomery. According to theU.S. Census Bureau

The United States Census Bureau (USCB), officially the Bureau of the Census, is a principal agency of the U.S. Federal Statistical System, responsible for producing data about the American people and economy. The Census Bureau is part of the ...

, the city has a total area of , of which is land and is water.

Climate

Demographics

2020 census

As of the 2020 United States Census, there were 17,971 people, 7,612 households, and 4,517 families residing in the city.2010 census

As of the 2010 census, there were 20,756 people living in the city. The racial makeup of the city was 80.3%Black

Black is a color which results from the absence or complete absorption of visible light. It is an achromatic color, without hue, like white and grey. It is often used symbolically or figuratively to represent darkness. Black and white ha ...

or African American

African Americans (also referred to as Black Americans and Afro-Americans) are an Race and ethnicity in the United States, ethnic group consisting of Americans with partial or total ancestry from sub-Saharan Africa. The term "African American ...

, 18.0% White

White is the lightness, lightest color and is achromatic (having no hue). It is the color of objects such as snow, chalk, and milk, and is the opposite of black. White objects fully diffuse reflection, reflect and scattering, scatter all the ...

, 0.20% Native American, 0.60% Asian, 0.1% other races, 0.80% from two or more races and Hispanics or Latinos, of any race, comprised 0.60% of the population.

2000 census

As of the census of 2000, there were 20,512 people, 8,196 households, and 5,343 families living in the city. The population density was . There were 9,264 housing units at an average density of . The racial makeup of the city was 70.68% Black or African American, 28.77% White, 0.10% Native American, 0.56% Asian, 0.01%Pacific Islander

Pacific Islanders, Pasifika, Pasefika, or rarely Pacificers are the peoples of the Pacific Islands. As an ethnic/racial term, it is used to describe the original peoples—inhabitants and diasporas—of any of the three major subregions of Ocea ...

, 0.22% from other races, and 0.66% from two or more races.

There were 8,196 households, out of which 30.3% had children under the age of 18 living with them; 34.2% were married couples living together, 27.2% had a female householder with no husband present, and 34.8% were non-families. 32.6% of all households were made up of individuals, and 14.6% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.44 and the average family size was 3.10.

In the city, the population was spread out, with 27.3% under the age of 18, 9.7% from 18 to 24, 24.9% from 25 to 44, 21.8% from 45 to 64, and 16.3% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 36 years. For every 100 females, there were 78.2 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 72.0 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $21,261, and the median income for a family was $28,345. Males had a median income of $29,769 versus $18,129 for females. The per capita income for the city was $13,369. About 26.9% of families and 31.7% of the population were below the poverty line, including 41.8% of those under age 18 and 28.0% of those age 65 or over.

Economy

Industries in Selma includeInternational Paper

The International Paper Company is an American pulp and paper company, the largest such company in the world. It has approximately 56,000 employees, and is headquartered in Memphis, Tennessee.

History

The company was incorporated January 31, ...

, Bush Hog

A bush hog or "brush hog" is a type of rotary mower. Typically these mowers attach to the back of a farm tractor using the three-point hitch and are driven via the power take-off (PTO). It has blades that are not rigidly attached to the drive like ...

(agricultural equipment), Plantation Patterns, American Apparel, and Peerless Pump Company (LaBour), Renasol, and Hyundai.

The city and rural region have struggled economically, as agriculture does not provide enough jobs. There was a downturn after restructuring in industry that had done well into the 1960s.

Civil rights

Civil and political rights are a class of rights that protect individuals' freedom from infringement by governments, social organizations, and private individuals. They ensure one's entitlement to participate in the civil and political life ...

tourism has become a new source of business.

Arts and culture

Arts

Cultural events are held at the Performing Arts Center, and the Selma Art Guild Gallery.

Cultural events are held at the Performing Arts Center, and the Selma Art Guild Gallery.

Museums and points of interest

Museums in the city include Sturdivant Hall, the National Voting Rights Museum, Historic Water Avenue, Martin Luther King, Jr. Street Historic Walking Tour, Old Depot Museum, Joe Calton Bates Children Education and History Museum, Vaughan-Smitherman Museum and Heritage Village. Selma boasts the state's largest contiguoushistoric district

A historic district or heritage district is a section of a city which contains older buildings considered valuable for historical or architectural reasons. In some countries or jurisdictions, historic districts receive legal protection from ce ...

, with more than 1,250 structures identified as contributing. Area attractions include the Old Town Historic District, Old Live Oak Cemetery, Paul M. Grist State Park, and Old Cahawba Archaeological Park.

The complex history is reflected in naming and monuments as well. Highway 80, which runs east and west through Selma and the state has reflected this in naming patterns. In 1920 the east-west Highway 80 was designated as part of the Jefferson Davis Memorial Highway. In 1977 US 80 was named Givhan Parkway in honor of the long-serving state senator Walter C. Givhan, a segregationist to the end. In 1996 it was designated as part of the 'National Civil Rights Trail' by President Bill Clinton and is administered by the National Park Service. In 2000 sections of Highway 80 leading into Selma were renamed in honor of leaders in the Selma Voting Rights Movement:

The complex history is reflected in naming and monuments as well. Highway 80, which runs east and west through Selma and the state has reflected this in naming patterns. In 1920 the east-west Highway 80 was designated as part of the Jefferson Davis Memorial Highway. In 1977 US 80 was named Givhan Parkway in honor of the long-serving state senator Walter C. Givhan, a segregationist to the end. In 1996 it was designated as part of the 'National Civil Rights Trail' by President Bill Clinton and is administered by the National Park Service. In 2000 sections of Highway 80 leading into Selma were renamed in honor of leaders in the Selma Voting Rights Movement: F.D. Reese

Frederick Douglas Reese (November 28, 1929 – April 5, 2018) was an American civil rights activist, educator and minister from Selma, Alabama. Known as a member of Selma's "Courageous Eight", Reese was the president of the Dallas County Voters Le ...

, Marie Foster, and Amelia Boynton.

As part of its Civil War history, a monument to native Nathan Bedford Forrest

Nathan Bedford Forrest (July 13, 1821October 29, 1877) was a prominent Confederate Army general during the American Civil War and the first Grand Wizard of the Ku Klux Klan from 1867 to 1869. Before the war, Forrest amassed substantial wealth ...

, a Confederate General, was installed in Old Live Oak Cemetery. It was torn down in 2012, reflecting the continuing controversy about him. In August 2012, plans were announced to build a larger monument, more resistant to vandalism, but many African Americans object to it because of his established history as a postwar leader with the KKK and his earlier involvement in the massacre of black Union troops at Fort Pillow.David J. Krajicek, "On the Road to Selma, a Jim Crow Relic"''The Crime Report'', February 2, 2015. Retrieved March 14, 2015

Library

The Selma-Dallas County Public Library serves the city and the region with a collection of 76,751 volumes. It was established as a Carnegie library in 1904, receiving matching funds for construction. The library is in downtown Selma.

The Selma-Dallas County Public Library serves the city and the region with a collection of 76,751 volumes. It was established as a Carnegie library in 1904, receiving matching funds for construction. The library is in downtown Selma.

Government

The city government of Selma consists of a mayor and a nine-member

The city government of Selma consists of a mayor and a nine-member city council

A municipal council is the legislative body of a municipality or local government area. Depending on the location and classification of the municipality it may be known as a city council, town council, town board, community council, rural counc ...

, elected from single-member districts

A single-member district is an electoral district represented by a single officeholder. It contrasts with a multi-member district, which is represented by multiple officeholders. Single-member districts are also sometimes called single-winner vo ...

. The current mayor is James Perkins Jr.

James Perkins Jr. (born 1952 or '53) was the first African American mayor and is the incumbent mayor of Selma, Alabama. He won a run-off in 2000 and served two terms, lost his second bid for reelection in 2008, and won a third non-consecutive term ...

The city council members are: William Warren Young, City Council President; Troy Harvill, Ward 1; Christie Thomas, Ward 2; Clay Carmichael, Ward 3; Lesia James, Ward 4; Samuel L. Randolph, Ward 5; Atkin Jemison, Ward 6; Jannie Thomas, Ward 7; Michael Johnson, Ward 8.

Transportation

* U.S. Highway 80 * State Route 14 * State Route 22 * State Route 41 * State Route 140 * State Route 219Airports

* Craig Field (SEM), located four nautical miles (4.6 mi, 7.4 km) southeast of the central business district of SelmaEducation

Colleges and universities

Colleges in Selma includeSelma University

Selma University is a Private historically black Baptist Bible college in Selma, Alabama. It is affiliated with the Alabama State Missionary Baptist Convention.

History

The institution was founded in 1878 as the Alabama Baptist Normal and The ...

and Wallace Community College Selma

George Corley Wallace State Community College (referred to as Wallace Community College Selma or WCCS) is a community college in Selma, Alabama. As of the Fall 2010 semester, WCCS has an enrollment of 1,938 students. The college was founded ...

, which is located at the edge of the city limits near Valley Grande, Alabama. Concordia College Alabama

Concordia College Alabama was a Private historically black college associated with the Lutheran Church–Missouri Synod and located in Selma, Alabama. It was the only historically black college among the ten colleges and universities in the C ...

, a private Lutheran university, operated in Selma from 1922 to 2018. Daniel Payne College

Daniel Payne College, also known as the Payne Institute, Payne University and Greater Payne University, was a historically black college in Birmingham, Alabama from 1889 to 1979. It was associated with the African Methodist Episcopal Church (AME ...

, an institution of the African Methodist Episcopal Church, operated in Selma from 1889 to 1922.

Public

Selma City Schools

Selma City Schools is a school district - for public schools - headquartered in Selma, Alabama

(We dare defend our rights)

, anthem = "Alabama (state song), Alabama"

, image_map = Alabama in United States.svg

, seat = Montgomery, Alabama, ...

operates the city's public schools. The public high school

A secondary school describes an institution that provides secondary education and also usually includes the building where this takes place. Some secondary schools provide both '' lower secondary education'' (ages 11 to 14) and ''upper seconda ...

is Selma High School

Selma High School is a public secondary school in Selma, Alabama. It is the only public high school in the Selma City School System.

History

Selma High School was formed in 1970 in response to court-ordered integration, merging the former white ...

. Middle schools include R.B. Hudson Middle School and the School of Discovery. The city has eight elementary schools.

Private

Selma has four privateK–12

K–12, from kindergarten to 12th grade, is an American English expression that indicates the range of years of publicly supported primary and secondary education found in the United States, which is similar to publicly supported school grades ...

schools: John T. Morgan Academy

John T. Morgan Academy, commonly known as Morgan Academy, is a school in Selma, Alabama, USA, originally founded in 1965 as a segregation academy.

History

The school is named for John Tyler Morgan, a Confederate general and Grand Dragon of the ...

, founded in 1965, Meadowview Christian School, Ellwood Christian Academy

Ellwood Christian Academy is a private, coeducational PK-12 Christian school in Selma, Alabama

Selma is a city in and the county seat of Dallas County, in the Black Belt region of south central Alabama and extending to the west. Located on th ...

, and Cathedral Christian Academy.

Media

Selma is served by the Montgomery-Selma television Designated Market Area (DMA).Charter Communications

Charter Communications, Inc., is an American telecommunications and mass media company with services branded as Spectrum. With over 32 million customers in 41 states, it is the second-largest cable operator in the United States by subscribers, ...

provides cable television service. DirecTV

DirecTV (trademarked as DIRECTV) is an American Multichannel television in the United States, multichannel video programming distributor based in El Segundo, California, El Segundo, California. Originally launched on June 17, 1994, its primary ...

and Dish Network

DISH Network Corporation (DISH, an acronym for DIgital Sky Highway) is an American television provider and the owner of the direct-broadcast satellite provider Dish, commonly known as Dish Network, and the over-the-top IPTV service, Sling TV ...

provide direct broadcast satellite

Satellite television is a service that delivers television programming to viewers by relaying it from a communications satellite orbiting the Earth directly to the viewer's location. The signals are received via an outdoor parabolic antenna commo ...

television including both local and national channels to area residents.

Radio stations

*WALX

WALX (100.9 FM, "ALEX-FM") is a classic hits music formatted radio station licensed to Orrville, Alabama, and serving the Selma, Alabama, market. The station is owned by Scott Communications, Inc.

Programming

WALX airs ''The Rick and Bubba Show' ...

100.9 FM (Classic Hits

Classic hits is a radio format which generally includes songs from the top 40 music charts from the late 1960s to the early 2000s, with music from the 1980s serving as the core of the format. Music that was popularized by MTV in the early 198 ...

)

* WAPR 88.3 FM (Educational)

* WAQU 91.1 FM (Christian

Christians () are people who follow or adhere to Christianity, a monotheistic Abrahamic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus Christ. The words '' Christ'' and ''Christian'' derive from the Koine Greek title ''Christós'' (Χρ ...

)

*WDXX

WDXX (100.1 FM, "Dixie Country") is a radio station licensed to serve Selma, Alabama, United States. The station is owned by Broadsouth Communications, Inc. It airs a country music format and features programming from Premiere Radio Networks.

...

100.1 FM (country

A country is a distinct part of the world, such as a state, nation, or other political entity. It may be a sovereign state or make up one part of a larger state. For example, the country of Japan is an independent, sovereign state, whil ...

)

*WHBB

WHBB (1490 AM) is a radio station licensed to serve Selma, Alabama, United States. The station is owned by Broadsouth Communications, Inc. WHBB serves the greater Central Alabama region with a 1,000 watt signal at 1490 kHz.

Programming

WHBB ...

1490 AM ( news/Talk

Talk may refer to:

Communication

* Communication, the encoding and decoding of exchanged messages between people

* Conversation, interactive communication between two or more people

* Lecture, an oral presentation intended to inform or instruct

...

/Gospel

Gospel originally meant the Christian message (" the gospel"), but in the 2nd century it came to be used also for the books in which the message was set out. In this sense a gospel can be defined as a loose-knit, episodic narrative of the words a ...

)

*WJAM

WJAM (1340 AM) is a radio station licensed to serve Selma, Alabama, United States. Originally launched in 1946, the station is currently owned by Scott Communications, Inc., and the WJAM broadcast license is held by Scott Communications, Inc.

...

1340 AM/96.3 FM (Urban adult contemporary

Urban adult contemporary, often abbreviated as urban AC or UAC, (also known as adult R&B,) is the name for a format of radio music, similar to an urban contemporary format. Radio stations using this format usually would not have hip hop music ...

)

* WRNF 89.5 FM (Religious

Religion is usually defined as a social- cultural system of designated behaviors and practices, morals, beliefs, worldviews, texts, sanctified places, prophecies, ethics, or organizations, that generally relates humanity to supernatural, ...

)

*WBFZ

WBFZ (105.3 FM) is a radio station licensed to serve Selma, Alabama, United States. The station is owned by Imani Communications Corporation, Inc. It airs an urban contemporary/gospel format.

History

This station received its original constructio ...

105.3 FM ( ospel Blues R&B Talk

Television stations

*WAKA

Waka may refer to:

Culture and language

* Waka (canoe), a Polynesian word for canoe; especially, canoes of the Māori of New Zealand

** Waka ama, a Polynesian outrigger canoe

** Waka hourua, a Polynesian ocean-going canoe

** Waka taua, a Māor ...

(Channel 8) CBS

* WBIH (Channel 29) Independent

Independent or Independents may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Artist groups

* Independents (artist group), a group of modernist painters based in the New Hope, Pennsylvania, area of the United States during the early 1930s

* Independe ...

Newspaper

*'' Selma Times-Journal'' (daily) Selma Sun (weekly)Notable people

*Zinn Beck

Zinn Bertram Beck (September 30, 1885 – March 19, 1981) was an American professional baseball player and manager. A third baseman, shortstop and first baseman, Beck played in Major League Baseball for the St. Louis Cardinals and New York Yankee ...

– Major League Baseball

Major League Baseball (MLB) is a professional baseball organization and the oldest major professional sports league in the world. MLB is composed of 30 total teams, divided equally between the National League (NL) and the American League (AL) ...

player; managed the first Selma Cloverleafs from 1928 to 1930, winning the Southeastern League

The Southeastern League was the name of four separate baseball leagues in minor league baseball which operated in the Southeastern and South Central United States in numerous seasons between 1897 and 2003. Two of these leagues were associated wit ...

pennant in 1930

* Ann Bedsole – Alabama State Representative (1979), first female member of the Alabama Senate

The Alabama State Senate is the upper house of the Alabama Legislature, the state legislature of the U.S. state of Alabama. The body is composed of 35 members representing an equal number of districts across the state, with each district contai ...

(1983)

*Patricia Swift Blalock

Patricia Swift Blalock (May 9, 1914 – September 7, 2011) was an American librarian, social worker, and civil rights activist born in Gadsden, Alabama.

Blalock graduated from the University of Montevallo and studied social work at the University ...

– librarian and civil rights movement

The civil rights movement was a nonviolent social and political movement and campaign from 1954 to 1968 in the United States to abolish legalized institutional Racial segregation in the United States, racial segregation, Racial discrimination ...

activist

* Jo Bonner – U.S. Representative for Alabama (2003)

*Edgar Cayce

Edgar Cayce (; 18 March 1877 – 3 January 1945) was an American clairvoyant who claimed to channel his higher self while in a trance-like state. His words were recorded by his friend, Al Layne; his wife, Gertrude Evans, and later by his ...

– psychic who worked and lived in Selma

* J.L. Chestnut – author, attorney, and civil rights movement

The civil rights movement was a nonviolent social and political movement and campaign from 1954 to 1968 in the United States to abolish legalized institutional Racial segregation in the United States, racial segregation, Racial discrimination ...

activist

*Jim Clark

James Clark Jr. OBE (4 March 1936 – 7 April 1968) was a British Formula One racing driver from Scotland, who won two World Championships, in 1963 and 1965. A versatile driver, he competed in sports cars, touring cars and in the Indianapol ...

– Dallas County Sheriff leading the attacks on citizens during the 1964–1965 voter registration campaign

A voter registration campaign or voter registration drive is an effort by a government authority, political party or other entity to register to vote persons otherwise entitled to vote. In some countries, voter registration is automatic, and is ca ...

in Selma

* Mattie Moss Clark – Gospel music artist & choir director, mother/founder of The Clark Sisters

The Clark Sisters are an American gospel vocal group consisting of five sisters: Jacky Clark Chisholm (born 1948), Denise "Niecy" Clark-Bradford (born 1953), Elbernita "Twinkie" Clark (born 1954), Dorinda Clark-Cole (born 1957), and Karen Cl ...

* Annie Lee Cooper – civil rights movement

The civil rights movement was a nonviolent social and political movement and campaign from 1954 to 1968 in the United States to abolish legalized institutional Racial segregation in the United States, racial segregation, Racial discrimination ...

activist

* Charles Davis – member of the Azerbaijan national basketball team

* Howard W. Gilmore – World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

submarine commander who posthumously received the Medal of Honor

The Medal of Honor (MOH) is the United States Armed Forces' highest military decoration and is awarded to recognize American soldiers, sailors, marines, airmen, guardians and coast guardsmen who have distinguished themselves by acts of valor ...

*Jimmy Gresham

James H. Gresham (born October 14, 1934 in Selma, Alabama), is a soul singer and writer. BMI list 14 songs to his credit. He wrote and produced records in Los Angeles in the 1960s. He also played in Rosey Grier's band, and wrote and produced reco ...

– soul music

Soul music is a popular music genre that originated in the African American community throughout the United States in the late 1950s and early 1960s. It has its roots in African-American gospel music and rhythm and blues. Soul music became pop ...

ian

* Gunnar Henderson- MLB Player for the Baltimore Orioles

*Mia Hamm

Mariel Margaret Hamm-Garciaparra (; born March 17, 1972) is an American retired professional soccer player, two-time Olympic gold medalist and two-time FIFA Women's World Cup champion. Hailed as a soccer icon, she played as a forward for the ...

– Women's United Soccer Association

The Women's United Soccer Association (WUSA) was the world's first women's soccer league in which all the players were paid as professionals. Founded in February 2000, the league began its first season in April 2001 with eight teams in the U ...

player, Olympic gold medallist

Olympic or Olympics may refer to

Sports

Competitions

* Olympic Games, international multi-sport event held since 1896

** Summer Olympic Games

** Winter Olympic Games

* Ancient Olympic Games, ancient multi-sport event held in Olympia, Greece b ...

*Jeremiah Haralson

Jeremiah Haralson (April 1, 1846 – 1916?), was a politician from Alabama who served as a state legislator and was among the first ten African-American United States Congressmen. Born into slavery in Columbus, Georgia, Haralson became self-educ ...

– slave, farmer and politician who lived here from 1859; he was the first African American from the state to be elected an Alabama State Representative (1870), Alabama State Senator (1872), and U.S. Representative (1875)

*Candy Harris

Alonzo Harris (born September 17, 1947) is a former Major League Baseball player for the Houston Astros just at the beginning of the season (April 13-April 27). He had been signed by the Baltimore Orioles as an amateur free agent before the 196 ...

– Major League Baseball

Major League Baseball (MLB) is a professional baseball organization and the oldest major professional sports league in the world. MLB is composed of 30 total teams, divided equally between the National League (NL) and the American League (AL) ...

player

*Sam Hobbs

Samuel Francis Hobbs (October 5, 1887 – May 31, 1952) was a United States Representative from Alabama.

Biography

Born in Selma, Alabama, Hobbs attended the public schools, Callaway's Preparatory School, Marion (Alabama) Military Institute ...

– U.S. Representative (1935)

* Eunice W. Johnson – founder and director of the ''Ebony

Ebony is a dense black/brown hardwood, coming from several species in the genus '' Diospyros'', which also contains the persimmons. Unlike most woods, ebony is dense enough to sink in water. It is finely textured and has a mirror finish when ...

'' Fashion Fair

* Michael Johnson – National Football League

The National Football League (NFL) is a professional American football league that consists of 32 teams, divided equally between the American Football Conference (AFC) and the National Football Conference (NFC). The NFL is one of the ma ...

player

* James Ralph "Shug" Jordan – head football coach of Auburn University

* William Rufus King – Vice President of the United States

The vice president of the United States (VPOTUS) is the second-highest officer in the executive branch of the U.S. federal government, after the president of the United States, and ranks first in the presidential line of succession. The vice p ...

(1853), U.S. Senator

The United States Senate is the upper chamber of the United States Congress, with the House of Representatives being the lower chamber. Together they compose the national bicameral legislature of the United States.

The composition and powe ...

(1844), U.S. Minister to France (1848)

*Terry Leach

Terry Hester Leach (born March 13, 1954) is a former Major League Baseball pitcher, and author of the book, ''Things Happen for a Reason: The True Story of an Itinerant Life in Baseball''.

Route to the majors

Leach played college ball at Auburn ...

– Major League Baseball

Major League Baseball (MLB) is a professional baseball organization and the oldest major professional sports league in the world. MLB is composed of 30 total teams, divided equally between the National League (NL) and the American League (AL) ...

player, namesake of Leach Field at Bloch Park

* Larry Marks – professional boxer

*William Clarence Matthews

William Clarence Matthews (January 7, 1877 – April 9, 1928) was an early 20th-century African-American pioneer in athletics, politics and law. Born in Selma, Alabama, Matthews was enrolled at the Tuskegee Institute and, with the help of Book ...

– baseball player, first head football coach for Tuskegee University

Tuskegee University (Tuskegee or TU), formerly known as the Tuskegee Institute, is a private, historically black land-grant university in Tuskegee, Alabama. It was founded on Independence Day in 1881 by the state legislature.

The campus was ...

, lawyer, and civil rights movement

The civil rights movement was a nonviolent social and political movement and campaign from 1954 to 1968 in the United States to abolish legalized institutional Racial segregation in the United States, racial segregation, Racial discrimination ...

activist

* Pat McHugh – National Football League

The National Football League (NFL) is a professional American football league that consists of 32 teams, divided equally between the American Football Conference (AFC) and the National Football Conference (NFC). The NFL is one of the ma ...

player

*Darrio Melton

Darrio Melton is an American politician who served as the Mayor of Selma from 2016 to 2020 and served in the Alabama House of Representatives

The Alabama State House of Representatives is the lower house of the Alabama Legislature, the st ...

– Alabama State Representative (2010), Mayor of Selma (2016)

* John Melvin – first American naval officer to die in World War I