Self-proclaimed monarchy on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

A self-proclaimed monarchy is established when a person claims a monarchy without any historical ties to a previous dynasty. The

A self-proclaimed monarchy is established when a person claims a monarchy without any historical ties to a previous dynasty. The

''The Second World War''

Boston: Mariner Books. p. 314. .

Voice of America, Oct 21, 2019. Accessed Oct 22, 2019. or "King" of

In 1860, a French adventurer, Orélie-Antoine de Tounens, proclaimed the " Kingdom of Araucanía" in

In 1860, a French adventurer, Orélie-Antoine de Tounens, proclaimed the " Kingdom of Araucanía" in

/ref> On 12 April 1961, Kalonji's father was granted the title ''Mulopwe'' (which roughly translates to "emperor" or "god-king"), but he immediately "abdicated" in favor of his son. On 16 July, but retained the title of ''Mulopwe'' and changed his name to Albert I Kalonji Ditunga. The move was controversial with members of Kalonji's own party and cost him much support. Shortly thereafter, as preparation for the invasion of Katanga, Congolese government troops invaded and occupied South Kasai, and Kalonji was arrested. He escaped, but South Kasai ultimately returned to the Congo.

In 1804, in

In 1804, in

"A Brief History of Sealand"

Historia Infinitas. Retrieved 11 May 2011 Upon his death in 2012, "

A self-proclaimed monarchy is established when a person claims a monarchy without any historical ties to a previous dynasty. The

A self-proclaimed monarchy is established when a person claims a monarchy without any historical ties to a previous dynasty. The self-proclaimed Self-proclaimed describes a legal title that is recognized by the declaring person but not necessarily by any recognized legal authority. It can be the status of a noble title or the status of a nation. The term is used informally for anyone declari ...

monarch

A monarch is a head of stateWebster's II New College DictionarMonarch Houghton Mifflin. Boston. 2001. p. 707. Life tenure, for life or until abdication, and therefore the head of state of a monarchy. A monarch may exercise the highest authority ...

may be of an established state, such as Zog I of Albania

Zog I ( sq, Naltmadhnija e tij Zogu I, Mbreti i Shqiptarëve, ; 8 October 18959 April 1961), born Ahmed Muhtar bey Zogolli, taking the name Ahmet Zogu in 1922, was the leader of Albania from 1922 to 1939. At age 27, he first served as Albania's y ...

, or of an unrecognised micronation

A micronation is a political entity whose members claim that they belong to an independent nation or sovereign state, but which lacks legal recognition by world governments or major international organizations. Micronations are classified s ...

, such as Leonard Casley of Hutt River, Western Australia.

Past self-proclaimed monarchies

Albania

In 1928,Ahmet Zogu

Zog I ( sq, Naltmadhnija e tij Zogu I, Mbreti i Shqiptarëve, ; 8 October 18959 April 1961), born Ahmed Muhtar bey Zogolli, taking the name Ahmet Zogu in 1922, was the leader of Albania from 1922 to 1939. At age 27, he first served as Albania's ...

, a president of Albania

Albania ( ; sq, Shqipëri or ), or , also or . officially the Republic of Albania ( sq, Republika e Shqipërisë), is a country in Southeastern Europe. It is located on the Adriatic

The Adriatic Sea () is a body of water separating the ...

, proclaimed himself "King Zog I". He ruled for 11 years in a nominally constitutional monarchy

A monarchy is a form of government in which a person, the monarch, is head of state for life or until abdication. The political legitimacy and authority of the monarch may vary from restricted and largely symbolic (constitutional monarchy ...

that was overthrown in the Italian invasion of Albania

The Italian invasion of Albania (April 7–12, 1939) was a brief military campaign which was launched by the Kingdom of Italy against the Albanian Kingdom in 1939. The conflict was a result of the imperialistic policies of the Italian prime ...

.Keegan, J. and Churchill, W. (1986)''The Second World War''

Boston: Mariner Books. p. 314. .

Andorra

In 1934,Boris Skossyreff

Boris Mikhailovich Skossyreff (russian: Бори́с Миха́йлович Ско́сырев, link=no, translit=Boris Mikhailovich Skosyrev; ca, Borís Mikhàilovitx Skóssirev ; 12 January 1896 – 27 February 1989) was a Russian adventure ...

declared himself "Boris I, King of Andorra

, image_flag = Flag of Andorra.svg

, image_coat = Coat of arms of Andorra.svg

, symbol_type = Coat of arms

, national_motto = la, Virtus Unita Fortior, label=none ( Latin)"United virtue is str ...

". After months in power, he was expelled when he declared war on Justí Guitart i Vilardebó, Bishop of Urgell and ex officio co-prince of Andorra

The co-princes of Andorra are jointly the heads of state ( ca, cap d'estat) of the Principality of Andorra, a landlocked microstate lying in the Pyrenees between France and Spain. Founded in 1278 by means of a treaty between the Bishop of ...

.

Australia

In 1970, after a dispute over wheat production quotas, Leonard Casley proclaimed his wheat farm inWestern Australia

Western Australia (commonly abbreviated as WA) is a state of Australia occupying the western percent of the land area of Australia excluding external territories. It is bounded by the Indian Ocean to the north and west, the Southern Ocean to ...

the "Principality of Hutt River

The Principality of Hutt River, often referred to by its former name, the Hutt River Province, was a micronation in Australia. The principality claimed to be an independent sovereign state, founded on 21 April 1970. It was dissolved on 3 Aug ...

", styling himself as "HRH Prince Leonard I of Hutt". The Australian government did not recognize his claim of independence. Casley abdicated in 2017, passing the principality to his son, " Prince Graeme I". The principality formally dissolved in 2020.

Cameroon

Lekeaka Oliver

Lekeaka Oliver, popularly known as Field Marshall, was a Cameroonian army soldier and later an Ambazonian separatist commander and the leader of the Red Dragon militia. His armed group is part of the loosely-structured Ambazonia Self-Defence Cou ...

was a separatist rebel commander who fought in the Anglophone Crisis

The Anglophone Crisis (), also known as the Ambazonia War or the Cameroonian Civil War, is an ongoing civil war in the Northwest and Southwest regions of Cameroon, part of the long-standing Anglophone problem. Following the suppression of the ...

. In 2019, he proclaimed himself "Paramount Ruler"Cameroon Separatist Fighter Names Himself 'King' of Southwest DistrictVoice of America, Oct 21, 2019. Accessed Oct 22, 2019. or "King" of

Lebialem

Lebialem is a department of Southwest Province in Cameroon. The department covers an area of 617 km and as of 2005 had a total population of 113,736. The capital of the department lies at Menji.

Since the outbreak of the Anglophone Crisis ...

, a department of Cameroon. This move was condemned both by Cameroonian loyalists as well as other rebels. Oliver was killed in 2022.

Central African Republic

In 1976, a short-lived 'Imperial' monarchy, the "Central African Empire

From 4 December 1976 to 21 September 1979, the Central African Republic was officially known as the Central African Empire (french: Empire centrafricain), after military dictator (and president at the time) Marshal

Marshal is a term used ...

", was created when dictator Jean-Bédel Bokassa

Jean-Bédel Bokassa (; 22 February 1921 – 3 November 1996), also known as Bokassa I, was a Central African political and military leader who served as the second president of the Central African Republic (CAR) and as the emperor of its s ...

of the Central African Republic

The Central African Republic (CAR; ; , RCA; , or , ) is a landlocked country in Central Africa. It is bordered by Chad to the north, Sudan to the northeast, South Sudan to the southeast, the DR Congo to the south, the Republic of the C ...

proclaimed himself "Emperor Bokassa I". The following year, he held a lavish coronation ceremony. He was deposed in 1979.

Chile

In 1860, a French adventurer, Orélie-Antoine de Tounens, proclaimed the " Kingdom of Araucanía" in

In 1860, a French adventurer, Orélie-Antoine de Tounens, proclaimed the " Kingdom of Araucanía" in Chile

Chile, officially the Republic of Chile, is a country in the western part of South America. It is the southernmost country in the world, and the closest to Antarctica, occupying a long and narrow strip of land between the Andes to the eas ...

with the support of local Mapuche

The Mapuche ( (Mapuche & Spanish: )) are a group of indigenous inhabitants of south-central Chile and southwestern Argentina, including parts of Patagonia. The collective term refers to a wide-ranging ethnicity composed of various groups who s ...

chiefs. He called himself "Orélie-Antoine I". In 1862, he was arrested and deported by the Chilean government.

China

Hong Xiuquan

Hong Xiuquan (1 January 1814 – 1 June 1864), born Hong Huoxiu and with the courtesy name Renkun, was a Chinese revolutionary who was the leader of the Taiping Rebellion against the Qing dynasty. He established the Taiping Heavenly Kingdo ...

proclaimed himself the leader of the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom

The Taiping Heavenly Kingdom, later shortened to the Heavenly Kingdom or Heavenly Dynasty, was an unrecognised rebel kingdom in China and a Chinese Christian theocratic absolute monarchy from 1851 to 1864, supporting the overthrow of the Q ...

during the Taiping Rebellion

The Taiping Rebellion, also known as the Taiping Civil War or the Taiping Revolution, was a massive rebellion and civil war that was waged in China between the Manchu-led Qing dynasty and the Han, Hakka-led Taiping Heavenly Kingdom. It last ...

in 1851.

In 1915, the president of China, Yuan Shikai

Yuan Shikai (; 16 September 1859 – 6 June 1916) was a Chinese military and government official who rose to power during the late Qing dynasty and eventually ended the Qing dynasty rule of China in 1912, later becoming the Emperor of China. ...

, declared a restoration of the Chinese monarchy, with himself as emperor. The plan failed, and he was forced to step down.Kuo T'ing-i et al. ''Historical Annals of the ROC (1911–1949).'' Vol 1. pp 207–241.

Since then, there have been repeated attempts by individuals to declare themselves Chinese emperor or empress. In the 1920s and 1930s, there were several peasant rebels who declared themselves members of House of Zhu

The House of Zhu () was the ruling house of the Ming dynasty (1368–1644) and the Southern Ming (1644–1662) in Chinese history.

After the fall of the Ming dynasty, the Manchu-led Qing dynasty started persecuting the Zhu clan, hence a number ...

and tried to restore the Ming dynasty

The Ming dynasty (), officially the Great Ming, was an Dynasties in Chinese history, imperial dynasty of China, ruling from 1368 to 1644 following the collapse of the Mongol Empire, Mongol-led Yuan dynasty. The Ming dynasty was the last ort ...

, such as the self-proclaimed emperors "Chu the Ninth" (1919–1922, backed by the Yellow Way Society), "Wang the Sixth" (1924), and Chu Hung-teng (1925, backed by the Heavenly Gate Society). In course of the Spirit Soldier rebellions (1920–1926)

The Spirit Soldier rebellions of 1920–1926 were a series of major peasant uprisings against state authorities and warlords in the Republic of China (1912–1949), Republic of China's provinces of Hubei and Sichuan during the Warlord Era. Follow ...

, a former farm worker and rebel leader named Yuan declared himself the "Jade Emperor

The Jade Emperor or Yudi ( or , ') in Chinese culture, traditional religions and myth is one of the representations of the first god ( '). In Daoist theology he is the assistant of Yuanshi Tianzun, who is one of the Three Pure Ones, the thre ...

". Following the Chinese Civil War

The Chinese Civil War was fought between the Kuomintang-led government of the Republic of China and forces of the Chinese Communist Party, continuing intermittently since 1 August 1927 until 7 December 1949 with a Communist victory on main ...

, there have been hundreds of monarchist pretenders who oppose the Chinese Communist Party

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP), officially the Communist Party of China (CPC), is the founding and sole ruling party of the People's Republic of China (PRC). Under the leadership of Mao Zedong, the CCP emerged victorious in the Chinese Ci ...

and often gathered small groups of supporters. Notable self-proclaimed monarchs include: Li Zhu, declared a new dynasty in 1954; Song Yiufang, leader of the Nine Palaces Way (crowned by his followers after sneaking into the Forbidden City

The Forbidden City () is a palace complex in Dongcheng District, Beijing, China, at the center of the Imperial City of Beijing. It is surrounded by numerous opulent imperial gardens and temples including the Zhongshan Park, the sacrific ...

in 1961); Yang Xuehua, empress of the Heavenly Palace Sect (arrested in 1976 and executed after allegedly planning a rebellion); Chao Yuhua, empress of the "Great Sage Dynasty" (crowned in 1988 in a factory); Tu Nanting, ex-soldier and emperor (believed in his emperorship after reading several books on prophecies, the arcane, and morals); Yang Zhaogong who attempted to establish a new dynasty with alleged backing of CCCPC members. In general, these self-proclaimed monarchs were not very successful and quickly arrested by security forces. However, one self-proclaimed emperor, Li Guangchang, organized a large sect of supporters and factually governed a small territory in Cangnan County

Cangnan County ( ) is a county in the prefecture-level city of Wenzhou in southern Zhejiang. The county government is in Lingxi. Cangnan has 20 towns, 14 townships, and two nationality townships. The predominant Chinese dialect spoken in Cangnan ...

, called the "Zishen Nation", from 1981 to 1986 in ''de facto'' independence from China. He was eventually arrested, reportedly after attempting to organize a wider rebellion.

Congo

Within days of being independent from Belgium, the new Republic of the Congo found itself torn between competing political factions, as well as by foreign interference. As the situation deteriorated,Moise Tshombe

Moise is a given name and surname, with differing spellings in its French and Romanian origins, both of which originate from the name Moses: Moïse is the French spelling of Moses, while Moise is the Romanian spelling. As a surname, Moisè and M ...

declared the independence of Katanga Province

Katanga was one of the four large provinces created in the Belgian Congo in 1914.

It was one of the eleven provinces of the Democratic Republic of the Congo between 1966 and 2015, when it was split into the Tanganyika, Haut-Lomami, Lualaba, ...

as the State of Katanga

The State of Katanga; sw, Inchi Ya Katanga) also sometimes denoted as the Republic of Katanga, was a breakaway state that proclaimed its independence from Congo-Léopoldville on 11 July 1960 under Moise Tshombe, leader of the local ''C ...

on 11 July 1960. Albert Kalonji

Albert Kalonji Ditunga (6 June 1929 – 20 April 2015) was a Congolese politician best known as the leader of the short-lived secessionist state of South Kasai (''Sud-Kasaï'') during the Congo Crisis.

Early life

Little is known about Alb ...

, claiming that the Baluba were being persecuted in the Congo and needed their own state in their traditional Kasai homeland, followed suit shortly afterwards and declared the autonomy of South Kasai

South Kasai (french: Sud-Kasaï) was an unrecognised secessionist state within the Republic of the Congo (the modern-day Democratic Republic of the Congo) which was semi-independent between 1960 and 1962. Initially proposed as only a province, ...

on 8 August, with himself as head."The Imperial Collection: The Autonomous State of South Kasai"/ref> On 12 April 1961, Kalonji's father was granted the title ''Mulopwe'' (which roughly translates to "emperor" or "god-king"), but he immediately "abdicated" in favor of his son. On 16 July, but retained the title of ''Mulopwe'' and changed his name to Albert I Kalonji Ditunga. The move was controversial with members of Kalonji's own party and cost him much support. Shortly thereafter, as preparation for the invasion of Katanga, Congolese government troops invaded and occupied South Kasai, and Kalonji was arrested. He escaped, but South Kasai ultimately returned to the Congo.

France

In 1736, Freiherr Theodor Stephan von Neuhof established himself asKing of Corsica

Theodore I of Corsica (25 August 169411 December 1756), born Freiherr Theodor Stephan von Neuhoff, was a low-ranking German title of nobility, usually translated "Baron". was a German adventurer who was briefly King of Corsica. Theodore is the sub ...

in an attempt to free the island of Corsica from Genoese rule.

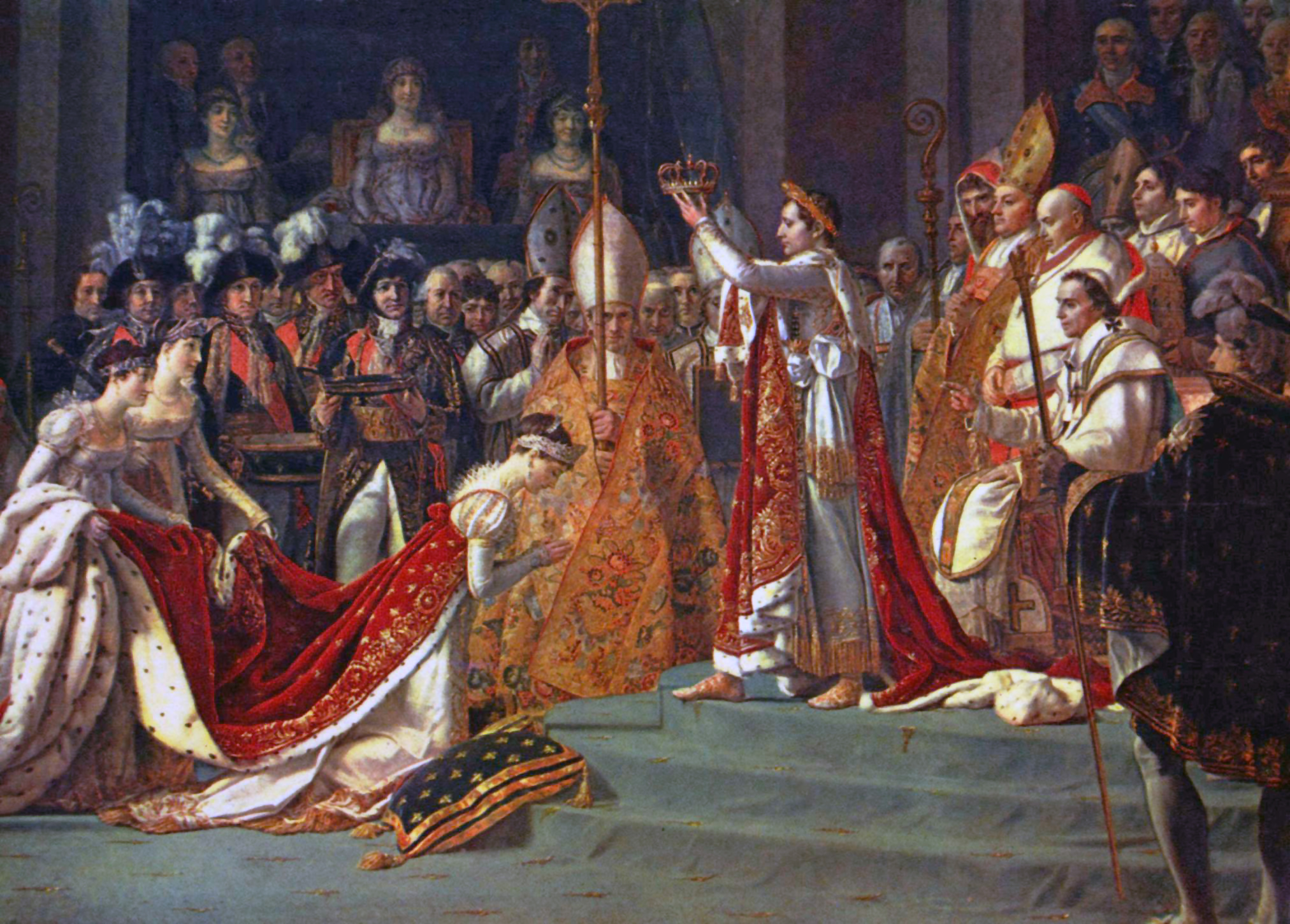

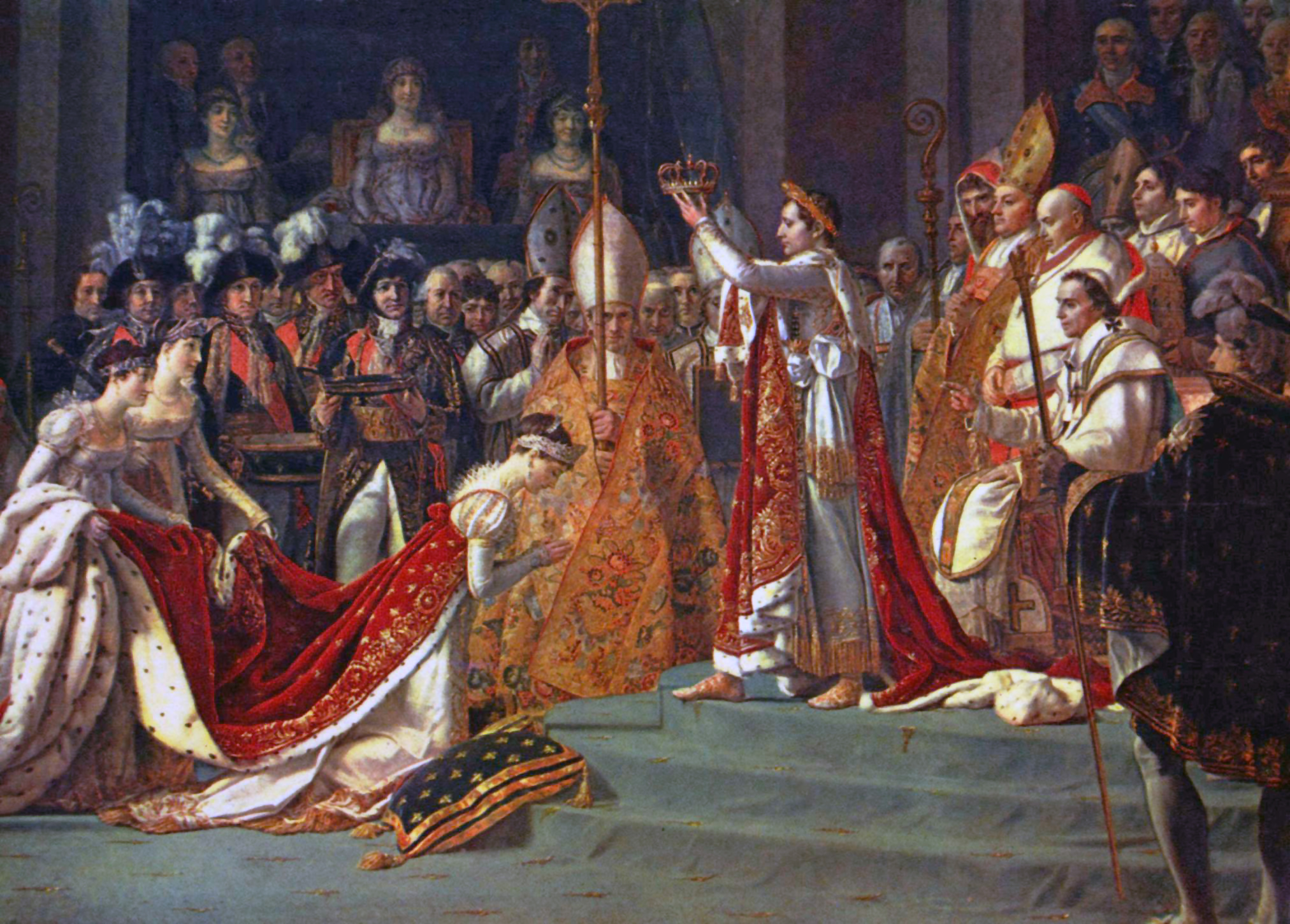

In 1804, French Consul

Consul (abbrev. ''cos.''; Latin plural ''consules'') was the title of one of the two chief magistrates of the Roman Republic, and subsequently also an important title under the Roman Empire. The title was used in other European city-states th ...

Napoleon Bonaparte

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader wh ...

proclaimed himself "Emperor

An emperor (from la, imperator, via fro, empereor) is a monarch, and usually the sovereign ruler of an empire or another type of imperial realm. Empress, the female equivalent, may indicate an emperor's wife ( empress consort), mother ( e ...

Napoleon I". Although this imperial regime ended with his fall from power, Napoleon's nephew, Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte, was elected in 1848 as President of France

The president of France, officially the president of the French Republic (french: Président de la République française), is the executive head of state of France, and the commander-in-chief of the French Armed Forces. As the presidency is ...

. In 1852, he declared himself "Emperor Napoleon III

Napoleon III (Charles Louis Napoléon Bonaparte; 20 April 18089 January 1873) was the first President of France (as Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte) from 1848 to 1852 and the last monarch of France as Emperor of the French from 1852 to 1870. A nephew ...

"; he was deposed in 1870.Nohlen & Stöver, p683

Haiti

In 1804, in

In 1804, in Haiti

Haiti (; ht, Ayiti ; French: ), officially the Republic of Haiti (); ) and formerly known as Hayti, is a country located on the island of Hispaniola in the Greater Antilles archipelago of the Caribbean Sea, east of Cuba and Jamaica, and ...

, the governor general, Jean-Jacques Dessalines

Jean-Jacques Dessalines (Haitian Creole: ''Jan-Jak Desalin''; ; 20 September 1758 – 17 October 1806) was a leader of the Haitian Revolution and the first ruler of an independent Haiti under the 1805 constitution. Under Dessalines, Haiti bec ...

, proclaimed himself "Emperor Jacques I". He ruled for two years. In 1811, the president, Henry Christophe, proclaimed himself " King Henri I" and ruled until 1820.Cheesman, 2007. In 1849, the president, Faustin Soulouque

Faustin-Élie Soulouque (15 August 1782 – 3 August 1867) was a Haitian politician and military commander who served as President of Haiti from 1847 to 1849 and Emperor of Haiti from 1849 to 1859.

Soulouque was a general in the Haitian Army ...

, proclaimed himself " Emperor Faustin I" and ruled until 1859.

Mexico

On 19 May 1822,Agustín Cosme Damián de Iturbide y Arámburu

Agustín is a Spanish given name and sometimes a surname. It is related to Augustín. People with the name include:

Given name

* Agustín (footballer), Spanish footballer

* Agustín Calleri (born 1976), Argentine tennis player

* Agustín C� ...

, was crowned as Emperor of Mexico

The Emperor of Mexico (Spanish: ''Emperador de México'') was the head of state and ruler of Mexico on two non-consecutive occasions in the 19th century.

With the Declaration of Independence of the Mexican Empire from Spain in 1821, Mexico be ...

. He was a Mexican-born general who had served in the Spanish Army, during the Mexican War of Independence

The Mexican War of Independence ( es, Guerra de Independencia de México, links=no, 16 September 1810 – 27 September 1821) was an armed conflict and political process resulting in Mexico's independence from Spain. It was not a single, co ...

, but switched sides and joined the Mexican rebels in 1820. He was proclaimed president of the Regency in 1821. When King Ferdinand VII of Spain refused to become a constitutional monarch, Iturbide was crowned Emperor. He ruled Mexico

Mexico ( Spanish: México), officially the United Mexican States, is a country in the southern portion of North America. It is bordered to the north by the United States; to the south and west by the Pacific Ocean; to the southeast by Guate ...

for less than as a year as he abdicated and went into exile during a revolt in March 1823. He returned to Mexico on 14 July 1824 and was executed by the Provisional Government of Mexico

The Supreme Executive Power ( es, link=no, Supremo Poder Ejecutivo) was the provisional government of Mexico that governed between the fall of the First Mexican Empire in April 1823 and the election of the first Mexican president, Guadalupe Victo ...

.

Philippines

In 1823, inManila

Manila ( , ; fil, Maynila, ), officially the City of Manila ( fil, Lungsod ng Maynila, ), is the capital city, capital of the Philippines, and its second-most populous city. It is Cities of the Philippines#Independent cities, highly urbanize ...

, Philippines

The Philippines (; fil, Pilipinas, links=no), officially the Republic of the Philippines ( fil, Republika ng Pilipinas, links=no),

* bik, Republika kan Filipinas

* ceb, Republika sa Pilipinas

* cbk, República de Filipinas

* hil, Republ ...

, a regimental captain, Andrés Novales, staged a mutiny and proclaimed himself "Emperor of the Philippines". After one day, Spanish

Spanish might refer to:

* Items from or related to Spain:

** Spaniards are a nation and ethnic group indigenous to Spain

**Spanish language, spoken in Spain and many Latin American countries

**Spanish cuisine

Other places

* Spanish, Ontario, Ca ...

troops from Pampanga

Pampanga, officially the Province of Pampanga ( pam, Lalawigan ning Pampanga; tl, Lalawigan ng Pampanga ), is a province in the Central Luzon region of the Philippines. Lying on the northern shore of Manila Bay, Pampanga is bordered by Tar ...

and Intramuros

Intramuros (Latin for "inside the walls") is the historic walled area within the city of Manila, the capital of the Philippines. It is administered by the Intramuros Administration with the help of the city government of Manila.

Present-day I ...

removed him.

Trindade

In 1893, James Harden-Hickey, an admirer of Napoleon III, crowned himself "James I of the Principality of Trinidad". For two years he tried but failed to assert his claim.United States

In 1850, James J. Strang, who claimed to beJoseph Smith

Joseph Smith Jr. (December 23, 1805June 27, 1844) was an American religious leader and founder of Mormonism and the Latter Day Saint movement. When he was 24, Smith published the Book of Mormon. By the time of his death, 14 years later, h ...

's successor as leader of the Latter Day Saint movement

The Latter Day Saint movement (also called the LDS movement, LDS restorationist movement, or Smith–Rigdon movement) is the collection of independent church groups that trace their origins to a Christian Restorationist movement founded by Jo ...

, proclaimed himself king of his followers on Beaver Island, Michigan

Beavers are large, semiaquatic rodents in the genus ''Castor'' native to the temperate Northern Hemisphere. There are two extant species: the North American beaver (''Castor canadensis'') and the Eurasian beaver (''C. fiber''). Beavers a ...

. On 8 July 1850, he was crowned in an elaborate coronation

A coronation is the act of placement or bestowal of a crown upon a monarch's head. The term also generally refers not only to the physical crowning but to the whole ceremony wherein the act of crowning occurs, along with the presentation of o ...

ceremony. Strang evaded Federal government charges of treason

Treason is the crime of attacking a state authority to which one owes allegiance. This typically includes acts such as participating in a war against one's native country, attempting to overthrow its government, spying on its military, its diplo ...

and continued to rule until 1856, the year he was assassinated by two disgruntled "Strangites".

In 1859, Joshua Abraham Norton, a failed businessman from San Francisco

San Francisco (; Spanish language, Spanish for "Francis of Assisi, Saint Francis"), officially the City and County of San Francisco, is the commercial, financial, and cultural center of Northern California. The city proper is the List of Ca ...

, declared himself "Emperor of America and Protector of Mexico"; he became and remained a local celebrity for the rest of his life.

Current self-proclaimed monarchies

Italy

The Principality of Seborga ( it, Principato di Seborga) is amicronation

A micronation is a political entity whose members claim that they belong to an independent nation or sovereign state, but which lacks legal recognition by world governments or major international organizations. Micronations are classified s ...

that claims a area located in the northwestern Italian Province of Imperia

The Province of Imperia ( it, Provincia di Imperia, french: Province d'Imperia, Ligurian: ''Provinsa d’Imperia'') is a mountainous and hilly province, in the Liguria region of Italy, situated between France to the north and the west, and the L ...

in Liguria

Liguria (; lij, Ligûria ; french: Ligurie) is a Regions of Italy, region of north-western Italy; its Capital city, capital is Genoa. Its territory is crossed by the Alps and the Apennine Mountains, Apennines Mountain chain, mountain range and is ...

, near the French border, and about from Monaco

Monaco (; ), officially the Principality of Monaco (french: Principauté de Monaco; Ligurian: ; oc, Principat de Mónegue), is a sovereign

''Sovereign'' is a title which can be applied to the highest leader in various categories. The word ...

. The principality is in coexistence with, and claims the territory of, the town of Seborga

Seborga ( lij, A Seborca) is a small village and self-proclaimed principality in the region of Liguria near the French border. Administratively, it is a '' comune'' of the Italian province of Imperia. The main economic activities are horticult ...

. In the early 1960s, Giorgio Carbone, began promoting the idea that Seborga restore its historic independence as a principality. By 1963 the people of Seborga were sufficiently convinced of these arguments to elect Carbone as their Head of State. He then assumed the style and title ''His Serene Highness'' Giorgio I, Prince of Seborga, which he held until his death in 2009. The Principality of Seborga is an elective monarchy

An elective monarchy is a monarchy ruled by an elected monarch, in contrast to a hereditary monarchy in which the office is automatically passed down as a family inheritance. The manner of election, the nature of candidate qualifications, and t ...

and elections are held

every seven years. The subsequent monarch was Prince Marcello Menegatto (Prince Marcello I) who ruled from 2010 to 2019. On 23 April 2017, Prince Marcello was re-elected and took office for another seven years, but abdicated the throne in 2019. Nina Menegatto was elected head of state as Princess Nina on 10 November 2019.

United Kingdom

In 1967, Paddy Roy Bates, a former major in theBritish Army

The British Army is the principal land warfare force of the United Kingdom, a part of the British Armed Forces along with the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force. , the British Army comprises 79,380 regular full-time personnel, 4,090 Gur ...

, took control of Roughs Tower

HM Fort Roughs was one of several World War II installations that were designed by Guy Maunsell and known collectively as ''His Majesty's Forts'' or as ''Maunsell Sea Forts''; its purpose was to guard the port of Harwich, Essex, and more bro ...

, a Maunsell sea fort situated off the coast of Suffolk

Suffolk () is a ceremonial county of England in East Anglia. It borders Norfolk to the north, Cambridgeshire to the west and Essex to the south; the North Sea lies to the east. The county town is Ipswich; other important towns include L ...

and declared it the "Principality of Sealand

The Principality of Sealand () is an unrecognized micronation that claims HM Fort Roughs (also known as Roughs Tower), an offshore platform in the North Sea approximately off the coast of Suffolk, as its territory. Roughs Tower is a Maunsell ...

".Strauss, Erwin. ''How to Start Your Own Country'', Paladin Press, 1999, p. 132, cited in admin (20 September 2008)"A Brief History of Sealand"

Historia Infinitas. Retrieved 11 May 2011 Upon his death in 2012, "

Prince

A prince is a Monarch, male ruler (ranked below a king, grand prince, and grand duke) or a male member of a monarch's or former monarch's family. ''Prince'' is also a title of nobility (often highest), often hereditary title, hereditary, in s ...

" Paddy Roy Bates was succeeded by his son, Michael.

Canada

Romana Didulo, a Filipina–Canadian woman, claimed to be the "secret Queen of Canada" in June 2021, and amassed a cult-like following, mainly consisting of right-wingQAnon

QAnon ( , ) is an American political conspiracy theory and political movement. It originated in the American far-right political sphere in 2017. QAnon centers on fabricated claims made by an anonymous individual or individuals known as "Q". ...

supporters, being followed by 17,000 users of Telegram

Telegraphy is the long-distance transmission of messages where the sender uses symbolic codes, known to the recipient, rather than a physical exchange of an object bearing the message. Thus flag semaphore is a method of telegraphy, whereas ...

, a messaging platform favoured by the far-right and QAnon figures. She and her followers began to hand out "cease and desist" letters, demanding people and businesses stop following Canadian COVID-19

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is a contagious disease caused by a virus, the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). The first known case was identified in Wuhan, China, in December 2019. The disease quickl ...

restrictions.

In an introductory video on Telegram, Didulo claimed to be "the founder and leader of Canada1st", an unregistered political party, and "the head of state and commander in chief of Canada, the Republic". She alleged that Canada's actual head of state, Queen Elizabeth II

Elizabeth II (Elizabeth Alexandra Mary; 21 April 1926 – 8 September 2022) was Queen of the United Kingdom and other Commonwealth realms from 6 February 1952 until her death in 2022. She was queen regnant of 32 sovereign states during ...

, had been executed secretly and that she had been appointed as Queen by "the same group of people who have helped president Trump", in reference to a common belief within the QAnon conspiracy theory. In reality, Elizabeth II did not die until September 8, 2022, and she was not executed.

References

Citations

Works cited

* * * * {{refend Monarchy