Second Reform Act on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Representation of the People Act 1867 ( 30 & 31 Vict. c. 102), known as the Reform Act 1867 or the Second Reform Act, is an act of the British Parliament that enfranchised part of the urban male

Faced with the possibility of popular revolt going much further, the government rapidly included into the bill amendments which enfranchised far more people. Consequently, the bill was more far-reaching than any Members of Parliament had thought possible or really wanted; Disraeli appeared to accept most reform proposals, so long as they did not come from

Faced with the possibility of popular revolt going much further, the government rapidly included into the bill amendments which enfranchised far more people. Consequently, the bill was more far-reaching than any Members of Parliament had thought possible or really wanted; Disraeli appeared to accept most reform proposals, so long as they did not come from

online

advanced statistical tests * Blake, Robert. ''The Conservative Party from Peel to Churchill'' (1970

online

* Cowling, Maurice. ''1867, Disraeli, Gladstone, and Revolution'' (1967). * * Evans, Eric J. ''Parliamentary reform in Britain, c. 1770–1918'' (Routledge, 2014). * Foot, Paul. ''The Vote: how it was won and how it was undermined'' (2005) * Gallagher, Thomas F. "The Second Reform Movement, 1848-1867" ''Albion'' 12#2 (1980): 147–163. * Garrard, John A. "Parties, members and voters after 1867: a local study." ''Historical Journal'' 20.1 (1977): 145–163

online

* Goldman, Lawrence. "Social Reform and the Pressure of ‘Progress’ on Parliament, 1660–1914." ''Parliamentary History'' 37 (2018): 72-88. * * Husted, T. A. and L. W. Kenny. "The effect of the expansion of the voting franchise on the size of government." ''Journal of Political Economy'' (1997) 105#1, 54–82. * Lawrence, Jon. "Class and gender in the making of urban Toryism, 1880-1914." ''English Historical Review'' 108.428 (1993): 629–652

online

* * St John, Ian. ''The Historiography of Gladstone and Disraeli'' (2016) ch 3. * Saunders, Robert. “The Politics of Reform and the Making of the Second Reform Act, 1848-1867.” ''Historical Journal,'' 50#3 (2007), pp. 571–591

online

* Saunders, Robert. ''Democracy and the Vote in British Politics, 1848–1867: The Making of the Second Reform Act'' (2013)

excerpt

* Seghezza, Elena, and Pierluigi Morelli. "Suffrage extension, social identity, and redistribution: the case of the Second Reform Act." ''European Review of Economic History'' 23.1 (2018): 30–49. * * * Walton, John K. ''The Second Reform Act'' (1987) * Zimmerman, Kristin. "Liberal Speech, Palmerstonian Delay, and the Passage of the Second Reform Act." ''English Historical Review'' vol. 118 (November 2003): 1176–1202.

Digital reproduction of the Original Act on the Parliamentary Archives catalogue

{{UK electoral reform, state=expanded Representation of the People Acts United Kingdom Acts of Parliament 1867 August 1867 Benjamin Disraeli Edward Smith-Stanley, 14th Earl of Derby William Ewart Gladstone John Russell, 1st Earl Russell

working class

The working class is a subset of employees who are compensated with wage or salary-based contracts, whose exact membership varies from definition to definition. Members of the working class rely primarily upon earnings from wage labour. Most c ...

in England and Wales

England and Wales () is one of the Law of the United Kingdom#Legal jurisdictions, three legal jurisdictions of the United Kingdom. It covers the constituent countries England and Wales and was formed by the Laws in Wales Acts 1535 and 1542. Th ...

for the first time, extending the franchise from landowners of freehold property above a certain value, to leaseholders and rental tenants as well. It took effect in stages over the next two years, culminating in full commencement on 1 January 1869.

Before the act, one million of the seven million adult men in England and Wales could vote; the act immediately doubled that number. Further, by the end of 1868 all male heads of household could vote, having abolished the widespread mechanism of the deemed rentpayer or ratepayer being a superior lessor or landlord who would act as middleman for the money paid ("compounding"). The act introduced a near-negligible redistribution of seats, far short of the urbanisation and population growth since 1832.

The overall intent was to help the Conservative Party, Benjamin Disraeli

Benjamin Disraeli, 1st Earl of Beaconsfield (21 December 1804 – 19 April 1881) was a British statesman, Conservative Party (UK), Conservative politician and writer who twice served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom. He played a ...

expecting a reward for his sudden and sweeping backing of the reforms discussed, yet it resulted in their loss of the 1868 general election.

Background

For the decades after theReform Act 1832

The Representation of the People Act 1832 (also known as the Reform Act 1832, Great Reform Act or First Reform Act) was an act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom (indexed as 2 & 3 Will. 4. c. 45), enacted by the Whig government of Pri ...

(the First Reform Act), cabinets (in that era leading from both Houses) had resisted attempts to push through further reform, and in particular left unfulfilled the six demands of the Chartist movement. After 1848, this movement declined rapidly, but elite opinion began to pay attention. It was thus only 27 years after the initial, quite modest, Great Reform Act 1832 that leading politicians thought it prudent to introduce further electoral reform. Following an unsuccessful attempt by Benjamin Disraeli

Benjamin Disraeli, 1st Earl of Beaconsfield (21 December 1804 – 19 April 1881) was a British statesman, Conservative Party (UK), Conservative politician and writer who twice served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom. He played a ...

to introduce a reform bill in 1859, Lord John Russell, who had played a major role in passing the Reform Act 1832, attempted this in 1860; but the Prime Minister, Lord Palmerston

Henry John Temple, 3rd Viscount Palmerston (20 October 1784 – 18 October 1865), known as Lord Palmerston, was a British statesman and politician who served as prime minister of the United Kingdom from 1855 to 1858 and from 1859 to 1865. A m ...

, a fellow Liberal, was against any further electoral reform.

The Union victory in the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and the Confederate States of A ...

in 1865 emboldened the forces in Britain that demanded more democracy and public input into the political system, to the dismay of the upper class landed gentry who identified with the US Southern States planters and feared the loss of influence and a popular radical movement. Influential commentators included Walter Bagehot, Thomas Carlyle

Thomas Carlyle (4 December 17955 February 1881) was a Scottish essayist, historian, and philosopher. Known as the "Sage writing, sage of Chelsea, London, Chelsea", his writings strongly influenced the intellectual and artistic culture of the V ...

, Anthony Trollope

Anthony Trollope ( ; 24 April 1815 – 6 December 1882) was an English novelist and civil servant of the Victorian era. Among the best-known of his 47 novels are two series of six novels each collectively known as the ''Chronicles of Barsetshire ...

, Karl Marx

Karl Marx (; 5 May 1818 – 14 March 1883) was a German philosopher, political theorist, economist, journalist, and revolutionary socialist. He is best-known for the 1848 pamphlet '' The Communist Manifesto'' (written with Friedrich Engels) ...

and John Stuart Mill

John Stuart Mill (20 May 1806 – 7 May 1873) was an English philosopher, political economist, politician and civil servant. One of the most influential thinkers in the history of liberalism and social liberalism, he contributed widely to s ...

. Proponents used two arguments: the balance of the constitution and "moral right". They emphasized that deserving, skilled, sober, thrifty, and deferential artisans deserve the franchise. Liberal William Gladstone emphasized the "moral" improvement of workingmen and felt that they should therefore have the opportunity of "demonstrating their allegiance to their betters". However the opposition warned against the "low-class democracy" of the United States and Australia.

Palmerston's death in 1865 opened the floodgates for reform. In 1866 Russell (Earl Russell as he had been since 1861, and now Prime Minister for the second time), introduced a Reform Bill. It was a cautious bill, which proposed to enfranchise "respectable" working men, excluding unskilled workers and what was known as the "residuum", those that the MPs of the time described as feckless and criminal poor. This was ensured by a £7 annual rent qualification to vote—or 2 shillings and 9 pence (2s 9d) a week. This entailed two "fancy franchises", emulating measures of 1854, a £10 lodger qualification for the boroughs, and a £50 savings qualification in the counties. Liberals claimed that "the middle classes, strengthened by the best of the artisans, would still have the preponderance of power".

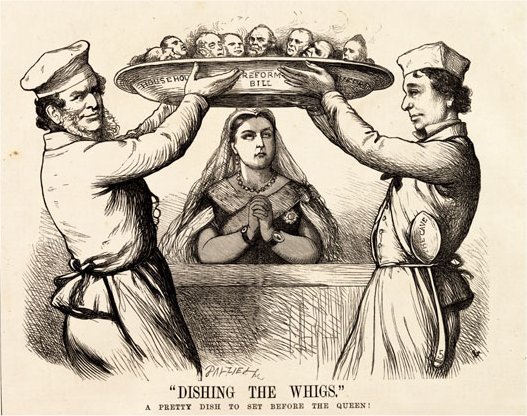

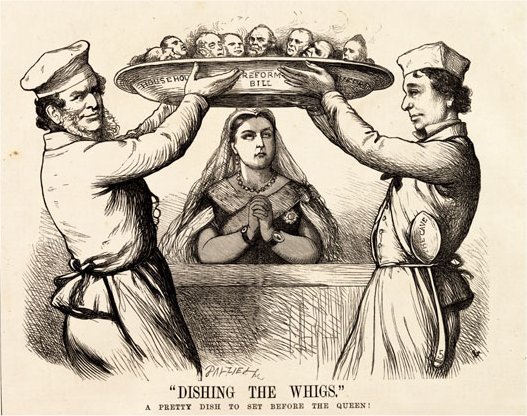

When it came to the vote, however, this bill split the Liberal Party: a split partly engineered by Benjamin Disraeli

Benjamin Disraeli, 1st Earl of Beaconsfield (21 December 1804 – 19 April 1881) was a British statesman, Conservative Party (UK), Conservative politician and writer who twice served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom. He played a ...

, who incited those threatened by the bill to rise up against it. On one side were the reactionary conservative Liberals, known as the Adullamites

The Adullamites were a short-lived anti-reform faction within the UK Liberal Party in 1866. The name was a biblical reference to the cave of Adullam where David and his allies sought refuge from Saul.

After the death of Palmerston in 1865, a ...

; on the other were pro-reform Liberals who supported the Government. The Adullamites were supported by Tories and the liberal Whigs were supported by radicals and reformists.

The bill was thus defeated and the Liberal government of Russell resigned.

Birth of the act

The Conservatives formed a ministry on 26 June 1866, led byLord Derby

Edward George Geoffrey Smith-Stanley, 14th Earl of Derby (29 March 1799 – 23 October 1869), known as Lord Stanley from 1834 to 1851, was a British statesman and Conservative politician who served three times as Prime Minister of the United K ...

as Prime Minister

A prime minister or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. A prime minister is not the head of state, but r ...

and Disraeli as Chancellor of the Exchequer

The chancellor of the exchequer, often abbreviated to chancellor, is a senior minister of the Crown within the Government of the United Kingdom, and the head of HM Treasury, His Majesty's Treasury. As one of the four Great Offices of State, t ...

. They were faced with the challenge of reviving Conservatism: Henry John Temple, 3rd Viscount Palmerston

Henry John Temple, 3rd Viscount Palmerston (20 October 1784 – 18 October 1865), known as Lord Palmerston, was a British statesman and politician who served as prime minister of the United Kingdom from 1855 to 1858 and from 1859 to 1865. A m ...

, the powerful Liberal leader, was dead and the Liberal Party was split and defeated. Thanks to manoeuvring by Disraeli, Derby's Conservatives saw an opportunity to be a strong, viable party of government; however, there was still a Liberal majority in the House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the Bicameralism, bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of ...

.

The Adullamites

The Adullamites were a short-lived anti-reform faction within the UK Liberal Party in 1866. The name was a biblical reference to the cave of Adullam where David and his allies sought refuge from Saul.

After the death of Palmerston in 1865, a ...

, led by Robert Lowe

Robert Lowe, 1st Viscount Sherbrooke, GCB, PC (4 December 1811 – 27 July 1892), British statesman, was a Liberal politician who helped shape British politics in the latter half of the 19th century. He held office under William Ewart Glad ...

, had already been working closely with the Conservative Party. The Adullamites were anti-reform, as were the Conservatives, but the Adullamites declined the invitation to enter into Government with the Conservatives as they thought that they could have more influence from an independent position. Despite the fact that he had blocked the Liberal Reform Bill, in February 1867, Disraeli introduced his own Reform Bill into the House of Commons.

By this time the attitude of many in the country had ceased to be apathetic regarding reform of the House of Commons. Huge meetings, especially the ‘Hyde Park riots', and the feeling that many of the skilled working class were respectable, had persuaded many that there should be a Reform Bill. However, wealthy Conservative MP Lord Cranborne resigned his government ministry in disgust at the bill's introduction.

The Reform League

The Reform League was established in 1865 to press for manhood suffrage and the ballot in Great Britain. It collaborated with the more moderate and middle class Reform Union and gave strong support to the abortive Reform Bill 1866 and the su ...

, agitating for universal suffrage

Universal suffrage or universal franchise ensures the right to vote for as many people bound by a government's laws as possible, as supported by the " one person, one vote" principle. For many, the term universal suffrage assumes the exclusion ...

, became much more active, and organized demonstrations of hundreds of thousands of people in Manchester

Manchester () is a city and the metropolitan borough of Greater Manchester, England. It had an estimated population of in . Greater Manchester is the third-most populous metropolitan area in the United Kingdom, with a population of 2.92&nbs ...

, Glasgow

Glasgow is the Cities of Scotland, most populous city in Scotland, located on the banks of the River Clyde in Strathclyde, west central Scotland. It is the List of cities in the United Kingdom, third-most-populous city in the United Kingdom ...

, and other towns. Though these movements did not normally use revolutionary language as some Chartists had in the 1840s, they were powerful movements. The high point came when a demonstration in May 1867 in Hyde Park was banned by the government. Thousands of troops and policemen were prepared, but the crowds were so huge that the government did not dare to attack. The Home Secretary

The secretary of state for the Home Department, more commonly known as the home secretary, is a senior minister of the Crown in the Government of the United Kingdom and the head of the Home Office. The position is a Great Office of State, maki ...

, Spencer Walpole

Sir Spencer Walpole KCB, FBA (6 February 1839 – 7 July 1907) was an English historian and civil servant.

Background

He came of the younger branch of the '' de facto'' first prime minister, Robert Walpole who revived the Whig Party, b ...

, was forced to resign.

Faced with the possibility of popular revolt going much further, the government rapidly included into the bill amendments which enfranchised far more people. Consequently, the bill was more far-reaching than any Members of Parliament had thought possible or really wanted; Disraeli appeared to accept most reform proposals, so long as they did not come from

Faced with the possibility of popular revolt going much further, the government rapidly included into the bill amendments which enfranchised far more people. Consequently, the bill was more far-reaching than any Members of Parliament had thought possible or really wanted; Disraeli appeared to accept most reform proposals, so long as they did not come from William Ewart Gladstone

William Ewart Gladstone ( ; 29 December 1809 – 19 May 1898) was a British politican, starting as Conservative MP for Newark and later becoming the leader of the Liberal Party (UK), Liberal Party.

In a career lasting over 60 years, he ...

. An amendment tabled by the opposition (but not by Gladstone himself) trebled the new number entitled to vote under the bill; yet Disraeli simply accepted it. The bill enfranchised most men who lived in urban areas. The final proposals were as follows: a borough franchise for all who paid rates in person (that is, not compounders), men who paid more than £10 rent per year, and extra votes for graduates, professionals and those with over £50 savings. These last "fancy franchises" were seen by Conservatives as a weapon against a mass electorate.

However, Gladstone attacked the bill; a series of sparkling parliamentary debates with Disraeli resulted in the bill becoming much more radical. Having been given his chance by the belief that Gladstone's bill had gone too far in 1866, Disraeli had now gone further.

Disraeli was able to persuade his party to vote for the bill on the basis that the newly enfranchised electorate would be grateful and would vote Conservative at the next election. Despite this prediction, in 1868 the Conservatives lost the first general election

A general election is an electoral process to choose most or all members of a governing body at the same time. They are distinct from By-election, by-elections, which fill individual seats that have become vacant between general elections. Gener ...

in which the newly enfranchised electors voted.

The bill ultimately aided the rise of the radical wing of the Liberal Party and helped Gladstone to victory. The Act was tidied up with many further Acts to alter electoral boundaries.

Provisions of the act

Reduced representation

Disenfranchised boroughs

Four electoral boroughs were disenfranchised by the act, for corruption, their last number of MPs shown as blocks: *Totnes

Totnes ( or ) is a market town and civil parish at the head of the estuary of the River Dart in Devon, England, within the South Devon Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty. It is about west of Paignton, about west-southwest of Torquay and ab ...

, Devon

*Great Yarmouth

Great Yarmouth ( ), often called Yarmouth, is a seaside resort, seaside town which gives its name to the wider Borough of Great Yarmouth in Norfolk, England; it straddles the River Yare and is located east of Norwich. Its fishing industry, m ...

, Norfolk

*Lancaster

Lancaster may refer to:

Lands and titles

*The County Palatine of Lancaster, a synonym for Lancashire

*Duchy of Lancaster, one of only two British royal duchies

*Duke of Lancaster

*Earl of Lancaster

*House of Lancaster, a British royal dynasty

...

, Lancashire

*Reigate

Reigate ( ) is a town status in the United Kingdom, town in Surrey, England, around south of central London. The settlement is recorded in Domesday Book of 1086 as ''Cherchefelle'', and first appears with its modern name in the 1190s. The ea ...

, Surrey

Seven English boroughs were disenfranchised by the Representation of the People (Scotland) Act 1868

The Representation of the People (Scotland) Act 1868 ( 31 & 32 Vict. c. 48) was an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. It carried on from the Representation of the People Act 1867, and created seven additional Scottish seats in the Hou ...

the next year, their last number of MPs shown as blocks:

*Arundel

Arundel ( ) is a market town and civil parish in the Arun District of the South Downs, West Sussex, England.

The much-conserved town has a medieval castle and Roman Catholic cathedral. Arundel has a museum and comes second behind much la ...

, Sussex

* Ashburton, Devon

* Dartmouth, Devon

*Honiton

Honiton () is a market town and civil parish in East Devon, situated close to the River Otter, Devon, River Otter, north east of Exeter in the county of Devon. Honiton has a population estimated at 12,154 (based on 2021 census).

History

The ...

, Devon

*Lyme Regis

Lyme Regis ( ) is a town in west Dorset, England, west of Dorchester, Dorset, Dorchester and east of Exeter. Sometimes dubbed the "Pearl of Dorset", it lies by the English Channel at the Dorset–Devon border. It has noted fossils in cliffs and ...

, Dorset

*Thetford

Thetford is a market town and civil parishes in England, civil parish in the Breckland District of Norfolk, England. It is on the A11 road (England), A11 road between Norwich and London, just east of Thetford Forest. The civil parish, coverin ...

, Norfolk

* Wells, Somerset

Halved representation

The following boroughs were reduced from electing two MPs to one: *Andover

Andover may refer to:

Places Australia

*Andover, Tasmania

Canada

* Andover Parish, New Brunswick

* Perth-Andover, New Brunswick

United Kingdom

* Andover, Hampshire, England

** RAF Andover, a former Royal Air Force station

United States

* Andov ...

, Hampshire

*Bodmin

Bodmin () is a town and civil parish in Cornwall, England, United Kingdom. It is situated south-west of Bodmin Moor.

The extent of the civil parish corresponds fairly closely to that of the town so is mostly urban in character. It is bordered ...

, Cornwall

*Bridgnorth

Bridgnorth is a market town and civil parish in Shropshire, England. The River Severn splits it into High Town and Low Town, the upper town on the right bank and the lower on the left bank of the River Severn. The population at the United Kingd ...

, Shropshire

*Bridport

Bridport is a market town and civil parish in Dorset, England, inland from the English Channel near the confluence of the River Brit and its tributary the River Asker, Asker. Its origins are Anglo-Saxons, Saxon and it has a long history as a ...

, Dorset

*Buckingham

Buckingham ( ) is a market town in north Buckinghamshire, England, close to the borders of Northamptonshire and Oxfordshire, which had a population of 12,890 at the United Kingdom Census 2011, 2011 Census. The town lies approximately west of ...

, Buckinghamshire

*Chichester

Chichester ( ) is a City status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city and civil parish in the Chichester District, Chichester district of West Sussex, England.OS Explorer map 120: Chichester, South Harting and Selsey Scale: 1:25 000. Publisher ...

, Sussex

*Chippenham

Chippenham is a market town in north-west Wiltshire, England. It lies north-east of Bath, Somerset, Bath, west of London and is near the Cotswolds Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty. The town was established on a crossing of the River Avon, ...

, Wiltshire

*Cirencester

Cirencester ( , ; see #Pronunciation, below for more variations) is a market town and civil parish in the Cotswold District of Gloucestershire, England. Cirencester lies on the River Churn, a tributary of the River Thames. It is the List of ...

, Gloucestershire

*Cockermouth

Cockermouth is a market town and civil parish in the Cumberland unitary authority area of Cumbria, England. The name refers to the town's position by the confluence of the River Cocker into the River Derwent. At the 2021 census, the built u ...

, Cumberland

*Devizes

Devizes () is a market town and civil parish in Wiltshire, England. It developed around Devizes Castle, an 11th-century Norman architecture, Norman castle, and received a charter in 1141. The castle was besieged during the Anarchy, a 12th-cent ...

, Wiltshire

* Dorchester, Dorset

*Evesham

Evesham () is a market town and Civil parishes in England, parish in the Wychavon district of Worcestershire, in the West Midlands (region), West Midlands region of England. It is located roughly equidistant between Worcester, England, Worceste ...

, Worcestershire

*Guildford

Guildford () is a town in west Surrey, England, around south-west of central London. As of the 2011 census, the town has a population of about 77,000 and is the seat of the wider Borough of Guildford, which had around inhabitants in . The nam ...

, Surrey

*Harwich

Harwich is a town in Essex, England, and one of the Haven ports on the North Sea coast. It is in the Tendring district. Nearby places include Felixstowe to the north-east, Ipswich to the north-west, Colchester to the south-west and Clacton-o ...

, Essex

*Hertford

Hertford ( ) is the county town of Hertfordshire, England, and is also a civil parish in the East Hertfordshire district of the county. The parish had a population of 26,783 at the 2011 census.

The town grew around a Ford (crossing), ford on ...

, Hertfordshire

*Huntingdon

Huntingdon is a market town in the Huntingdonshire district of Cambridgeshire, England. The town was given its town charter by John, King of England, King John in 1205. It was the county town of the historic county of Huntingdonshire. Oliver C ...

, Huntingdonshire

*Knaresborough

Knaresborough ( ) is a market and spa town and civil parish on the River Nidd in North Yorkshire, England. It is east of Harrogate and was in the Borough of Harrogate until April 2023.

History

The Knaresborough Hoard, the largest hoard of ...

, West Riding of Yorkshire

*Leominster

Leominster ( ) is a market town in Herefordshire, England; it is located at the confluence of the River Lugg and its tributary the River Kenwater. The town is north of Hereford and south of Ludlow in Shropshire. With a population of almos ...

, Herefordshire

*Lewes

Lewes () is the county town of East Sussex, England. The town is the administrative centre of the wider Lewes (district), district of the same name. It lies on the River Ouse, Sussex, River Ouse at the point where the river cuts through the Sou ...

, Sussex

*Lichfield

Lichfield () is a city status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city and Civil parishes in England, civil parish in Staffordshire, England. Lichfield is situated south-east of the county town of Stafford, north-east of Walsall, north-west of ...

, Staffordshire

*Ludlow

Ludlow ( ) is a market town and civil parish in Shropshire (district), Shropshire, England. It is located south of Shrewsbury and north of Hereford, on the A49 road (Great Britain), A49 road which bypasses the town. The town is near the conf ...

, Shropshire

*Lymington

Lymington is a port town on the west bank of the Lymington River on the Solent, in the New Forest (district), New Forest district of Hampshire, England.

The town faces Yarmouth, Isle of Wight, to which there is a Roll-on/roll-off, car ferry s ...

, Hampshire

*Maldon

Maldon (, locally ) is a town and civil parish on the Blackwater Estuary in Essex, England. It is the seat of the Maldon District and starting point of the Chelmer and Blackwater Navigation. It is known for Maldon Sea Salt which is prod ...

, Essex

* Marlow, Buckinghamshire

* Malton, North Riding of Yorkshire

*Marlborough, Wiltshire

Marlborough ( , ) is a market town and Civil parishes in England, civil parish in the England, English Counties of England, county of Wiltshire on the A4 road (England), Old Bath Road, the old main road from London to Bath, Somerset, Bath. Th ...

* Newport, Isle of Wight

*Poole

Poole () is a coastal town and seaport on the south coast of England in the Bournemouth, Christchurch and Poole unitary authority area in Dorset, England. The town is east of Dorchester, Dorset, Dorchester and adjoins Bournemouth to the east ...

, Dorset

*Richmond

Richmond most often refers to:

* Richmond, British Columbia, a city in Canada

* Richmond, California, a city in the United States

* Richmond, London, a town in the London Borough of Richmond upon Thames, England

* Richmond, North Yorkshire, a town ...

, North Riding of Yorkshire

*Ripon

Ripon () is a cathedral city and civil parish in North Yorkshire, England. The city is located at the confluence of two tributaries of the River Ure, the Laver and Skell. Within the boundaries of the historic West Riding of Yorkshire, the ...

, West Riding of Yorkshire

* Stamford, Lincolnshire

*Tavistock

Tavistock ( ) is an ancient stannary and market town and civil parish in the West Devon district, in the county of Devon, England. It is situated on the River Tavy, from which its name derives. At the 2011 census, the three electoral wards (N ...

, Devon

*Tewkesbury

Tewkesbury ( ) is a market town and civil parish in the north of Gloucestershire, England. The town grew following the construction of Tewkesbury Abbey in the twelfth century and played a significant role in the Wars of the Roses. It stands at ...

, Gloucestershire

* Windsor, Berkshire

* Wycombe, Buckinghamshire

Three further boroughs (Honiton, Thetford, Wells) were also due to have their representation halved under the 1867 Act, but before this reduction took effect they were disenfranchised altogether by the 1868 Scottish Reform Act as noted above.

Enfranchisements

The Act created nine new single-member borough seats: *Burnley

Burnley () is a town and the administrative centre of the wider Borough of Burnley in Lancashire, England, with a 2021 population of 78,266. It is north of Manchester and east of Preston, at the confluence of the River Calder and River B ...

, Lancashire

*Darlington

Darlington is a market town in the Borough of Darlington, County Durham, England. It lies on the River Skerne, west of Middlesbrough and south of Durham. Darlington had a population of 107,800 at the 2021 Census, making it a "large town" ...

, County Durham

*Dewsbury

Dewsbury is a market town in the Metropolitan Borough of Kirklees in West Yorkshire, England. It lies on the River Calder, West Yorkshire, River Calder and on an arm of the Calder and Hebble Navigation waterway. It is to the west of Wakefield, ...

, West Riding of Yorkshire

*Gravesend

Gravesend is a town in northwest Kent, England, situated 21 miles (35 km) east-southeast of Charing Cross (central London) on the Bank (geography), south bank of the River Thames, opposite Tilbury in Essex. Located in the diocese of Roche ...

, Kent

*Hartlepool

Hartlepool ( ) is a seaside resort, seaside and port town in County Durham, England. It is governed by a unitary authority borough Borough of Hartlepool, named after the town. The borough is part of the devolved Tees Valley area with an estimat ...

, County Durham

*Middlesbrough

Middlesbrough ( ), colloquially known as Boro, is a port town in the Borough of Middlesbrough, North Yorkshire, England. Lying to the south of the River Tees, Middlesbrough forms part of the Teesside Built up area, built-up area and the Tees Va ...

, North Riding of Yorkshire

*Stalybridge

Stalybridge () is a town in Tameside, Greater Manchester, England. At the 2021 United Kingdom census, 2021 census, it had a population of 26,830.

Historic counties of England, Historically divided between Cheshire and Lancashire, it is east o ...

, Cheshire

* Stockton, County Durham

*Wednesbury

Wednesbury ( ) is a market town in the Sandwell district, in the county of the West Midlands (county), West Midlands, England; it was historically in Staffordshire. It is located near the source of the River Tame, West Midlands, River Tame and ...

, Staffordshire

The following two boroughs were enfranchised with two MPs:

* Chelsea, Middlesex

* Hackney, Middlesex

The following two were enlarged:

*Salford

Salford ( ) is a City status in the United Kingdom, city in Greater Manchester, England, on the western bank of the River Irwell which forms its boundary with Manchester city centre. Landmarks include the former Salford Town Hall, town hall, ...

and Merthyr Tydfil

Merthyr Tydfil () is the main town in Merthyr Tydfil County Borough, Wales, administered by Merthyr Tydfil County Borough Council. It is about north of Cardiff. Often called just Merthyr, it is said to be named after Tydfil, daughter of K ...

were given two MPs, up from one.

*Birmingham

Birmingham ( ) is a City status in the United Kingdom, city and metropolitan borough in the metropolitan county of West Midlands (county), West Midlands, within the wider West Midlands (region), West Midlands region, in England. It is the Lis ...

, Leeds

Leeds is a city in West Yorkshire, England. It is the largest settlement in Yorkshire and the administrative centre of the City of Leeds Metropolitan Borough, which is the second most populous district in the United Kingdom. It is built aro ...

, Liverpool

Liverpool is a port City status in the United Kingdom, city and metropolitan borough in Merseyside, England. It is situated on the eastern side of the River Mersey, Mersey Estuary, near the Irish Sea, north-west of London. With a population ...

and Manchester

Manchester () is a city and the metropolitan borough of Greater Manchester, England. It had an estimated population of in . Greater Manchester is the third-most populous metropolitan area in the United Kingdom, with a population of 2.92&nbs ...

now had three MPs, up from two.

Other changes

*TheWest Riding of Yorkshire

The West Riding of Yorkshire was one of three historic subdivisions of Yorkshire, England. From 1889 to 1974 the riding was an administrative county named County of York, West Riding. The Lord Lieutenant of the West Riding of Yorkshire, lieu ...

divided into three districts each returning two MPs.

*Cheshire

Cheshire ( ) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in North West England. It is bordered by Merseyside to the north-west, Greater Manchester to the north-east, Derbyshire to the east, Staffordshire to the south-east, and Shrop ...

, Derbyshire

Derbyshire ( ) is a ceremonial county in the East Midlands of England. It borders Greater Manchester, West Yorkshire, and South Yorkshire to the north, Nottinghamshire to the east, Leicestershire to the south-east, Staffordshire to the south a ...

, Devon

Devon ( ; historically also known as Devonshire , ) is a ceremonial county in South West England. It is bordered by the Bristol Channel to the north, Somerset and Dorset to the east, the English Channel to the south, and Cornwall to the west ...

shire, Essex

Essex ( ) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in the East of England, and one of the home counties. It is bordered by Cambridgeshire and Suffolk to the north, the North Sea to the east, Kent across the Thames Estuary to the ...

, Kent

Kent is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South East England. It is bordered by Essex across the Thames Estuary to the north, the Strait of Dover to the south-east, East Sussex to the south-west, Surrey to the west, and Gr ...

, Lincolnshire

Lincolnshire (), abbreviated ''Lincs'', is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in the East Midlands and Yorkshire and the Humber regions of England. It is bordered by the East Riding of Yorkshire across the Humber estuary to th ...

, Norfolk

Norfolk ( ) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in England, located in East Anglia and officially part of the East of England region. It borders Lincolnshire and The Wash to the north-west, the North Sea to the north and eas ...

, Somerset

Somerset ( , ), Archaism, archaically Somersetshire ( , , ) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South West England. It is bordered by the Bristol Channel, Gloucestershire, and Bristol to the north, Wiltshire to the east ...

, Staffordshire

Staffordshire (; postal abbreviation ''Staffs''.) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in the West Midlands (region), West Midlands of England. It borders Cheshire to the north-west, Derbyshire and Leicestershire to the east, ...

and Surrey

Surrey () is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South East England. It is bordered by Greater London to the northeast, Kent to the east, East Sussex, East and West Sussex to the south, and Hampshire and Berkshire to the wes ...

divided into three districts instead of two, each returning two MPs.

*Lancashire

Lancashire ( , ; abbreviated ''Lancs'') is a ceremonial county in North West England. It is bordered by Cumbria to the north, North Yorkshire and West Yorkshire to the east, Greater Manchester and Merseyside to the south, and the Irish Sea to ...

divided into four two-member districts instead of a three-member district and a two-member district.

*University of London

The University of London (UoL; abbreviated as Lond or more rarely Londin in Post-nominal letters, post-nominals) is a collegiate university, federal Public university, public research university located in London, England, United Kingdom. The ...

was given one seat.

*Parliament was allowed to continue sitting through a Demise of the Crown

Demise of the Crown is the legal term in the United Kingdom and the other Commonwealth realms for the transfer of the Crown upon the death or abdication of the monarch. The Crown transfers automatically to the monarch's heir. The concept evolved ...

.

*MPs exempted from having to seek re-election upon changing offices.

Reforms in Scotland and Ireland

The reforms forScotland

Scotland is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It contains nearly one-third of the United Kingdom's land area, consisting of the northern part of the island of Great Britain and more than 790 adjac ...

and Ireland

Ireland (, ; ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe. Geopolitically, the island is divided between the Republic of Ireland (officially Names of the Irish state, named Irelan ...

were carried out by two subsequent acts, the Representation of the People (Ireland) Act 1868

The Representation of the People (Ireland) Act 1868 ( 31 & 32 Vict. c. 49) was an act of Parliament in the United Kingdom.

The act did not alter the overall distribution of parliamentary seats in Ireland. It was originally proposed to merge t ...

and the Representation of the People (Scotland) Act 1868

The Representation of the People (Scotland) Act 1868 ( 31 & 32 Vict. c. 48) was an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. It carried on from the Representation of the People Act 1867, and created seven additional Scottish seats in the Hou ...

.

In Scotland, five existing constituencies gained members, and three new constituencies were formed. Two existing county constituencies were merged into one, giving an overall increase of seven members; this was offset by seven English boroughs (listed above) being disenfranchised, leaving the House with the same number of members.

The representation of Ireland remained unchanged.

Effects

Direct effects of the Act

The slur of local bribery and corruption dogged early debates in 1867–68. The whips' and leaders' decision to steer away discussion of electoral malpractice or irregularity to 1868's Election Petitions Act facilitated the progress of the main Reform Act. The unprecedented extension of the franchise to all householders effectively gave the vote to many working-class men, quite a considerable change.Jonathan Parry

Jonathan Philip Parry (born 1957), commonly referred to as Jon Parry, is emeritus professor of Modern British History at the University of Cambridge and Emeritus Fellow of Pembroke College. He has specialised in 19th and 20th century British polit ...

described this as a "borough franchise revolution"; Overwhelming election of the landed class or otherwise very wealthy to the Commons would no longer be assured by money, bribery and favours, those elected would reflect the most common sentiment of local units of the public. The brand-new franchise provisions were briefly flawed; the act did not address the issues of compounding and of not being a ratepayer in a household. Compounding (counting of one's under-tenants payments and using that count as a qualification) as to all rates and rents was made illegal, abolished in the enactment of a bill tabled by Liberal Grosvenor Hodgkinson. This meant that all male tenants would have to pay the parish/local rates directly and thus thereafter qualified for the vote.

A 2022 study found that the Act reduced political violence in the UK.

Unintended effects

* Increased amounts of party spending and political organisation at both a local and national level—politicians had to account themselves to the increased electorate, which without secret ballots meant an increased number of voters to treat or bribe. * The redistribution of seats actually served to make the House of Commons increasingly dominated by the upper classes. Only they could afford to pay the huge campaigning costs and the abolition of certain rotten boroughs removed some of the middle-class international merchants who had been able to obtain seats. TheLiberal Party

The Liberal Party is any of many political parties around the world.

The meaning of ''liberal'' varies around the world, ranging from liberal conservatism on the right to social liberalism on the left. For example, while the political systems ...

was worried about the prospect of a socialist party taking the bulk of the working-class vote, so they moved to the left, while their rivals the Conservatives

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy and ideology that seeks to promote and preserve traditional institutions, customs, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilizati ...

initiated occasional intrigues to encourage socialist candidates to stand against the Liberals.

Reform Act in literature

Thomas Carlyle

Thomas Carlyle (4 December 17955 February 1881) was a Scottish essayist, historian, and philosopher. Known as the "Sage writing, sage of Chelsea, London, Chelsea", his writings strongly influenced the intellectual and artistic culture of the V ...

's essay "Shooting Niagara: And After?" compares the Second Reform Act and democracy generally to plunging over Niagara Falls

Niagara Falls is a group of three waterfalls at the southern end of Niagara Gorge, spanning the Canada–United States border, border between the Provinces and territories of Canada, province of Ontario in Canada and the state of New York (s ...

. His essay provoked a response from Mark Twain

Samuel Langhorne Clemens (November 30, 1835 – April 21, 1910), known by the pen name Mark Twain, was an American writer, humorist, and essayist. He was praised as the "greatest humorist the United States has produced," with William Fau ...

, "A Day at Niagara" (1869). Trollope's ''Phineas Finn

''Phineas Finn'' is a novel by Anthony Trollope and the name of its leading character. The novel was first published as a monthly serial from 1867 to 1868 and issued in book form in 1869. It is the second of the " Palliser" series of novels. It ...

'' is concerned almost exclusively with the parliamentary progress of the Second Reform Act, and Finn sits for one of the seven fictional boroughs that are due to be disenfranchised.

See also

*Ballot Act 1872

The Ballot Act 1872 ( 35 & 36 Vict. c. 33) was an act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom that introduced the requirement for parliamentary and local government elections in the United Kingdom to be held by secret ballot. The act abolishe ...

* Reform Acts

The Reform Acts (or Reform Bills, before they were passed) are legislation enacted in the United Kingdom in the 19th and 20th century to enfranchise new groups of voters and to redistribute seats in the House of Commons of the Parliament of the ...

* Representation of the People Act

Representation of the People Act is a stock short title used in Antigua and Barbuda, The Bahamas, Bangladesh, Barbados, Belize, Ghana, Grenada, Guyana, India, Jamaica, Mauritius, Pakistan, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, Trinidad and Tobago, ...

* Representation of the People Act 1884

In the United Kingdom under the premiership of William Gladstone, the Representation of the People Act 1884 ( 48 & 49 Vict. c. 3), also known informally as the Third Reform Act, and the Redistribution Act of the following year were laws which ...

(or Third Reform Act)

* Representation of the People Act 1918

The Representation of the People Act 1918 ( 7 & 8 Geo. 5. c. 64) was an act of Parliament passed to reform the electoral system in Great Britain and Ireland. It is sometimes known as the Fourth Reform Act. The act extended the franchise in pa ...

(Fourth Reform Act)

* Redistribution of Seats Act 1885

The Redistribution of Seats Act 1885 (48 & 49 Vict. c. 23) was an Act of Parliament (United Kingdom), act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom (sometimes called the "Reform Act of 1885"). It was a piece of electoral reform legislation that r ...

* Benjamin Disraeli

Benjamin Disraeli, 1st Earl of Beaconsfield (21 December 1804 – 19 April 1881) was a British statesman, Conservative Party (UK), Conservative politician and writer who twice served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom. He played a ...

* William Ewart Gladstone

William Ewart Gladstone ( ; 29 December 1809 – 19 May 1898) was a British politican, starting as Conservative MP for Newark and later becoming the leader of the Liberal Party (UK), Liberal Party.

In a career lasting over 60 years, he ...

* Chartism

Chartism was a working-class movement for political reform in the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, United Kingdom that erupted from 1838 to 1857 and was strongest in 1839, 1842 and 1848. It took its name from the People's Charter of ...

Notes

;Notes ;ReferencesFurther reading

* Adelman, Paul. "The Second Reform Act of 1867" ''History Today'' (May 1967), Vol. 17 Issue 5, p317-325, online * Aidt, Toke, Stanley L. Winer, and Peng Zhang. "Franchise extension and fiscal structure in the United Kingdom 1820-1913: A new test of the Redistribution Hypothesis." (2020)online

advanced statistical tests * Blake, Robert. ''The Conservative Party from Peel to Churchill'' (1970

online

* Cowling, Maurice. ''1867, Disraeli, Gladstone, and Revolution'' (1967). * * Evans, Eric J. ''Parliamentary reform in Britain, c. 1770–1918'' (Routledge, 2014). * Foot, Paul. ''The Vote: how it was won and how it was undermined'' (2005) * Gallagher, Thomas F. "The Second Reform Movement, 1848-1867" ''Albion'' 12#2 (1980): 147–163. * Garrard, John A. "Parties, members and voters after 1867: a local study." ''Historical Journal'' 20.1 (1977): 145–163

online

* Goldman, Lawrence. "Social Reform and the Pressure of ‘Progress’ on Parliament, 1660–1914." ''Parliamentary History'' 37 (2018): 72-88. * * Husted, T. A. and L. W. Kenny. "The effect of the expansion of the voting franchise on the size of government." ''Journal of Political Economy'' (1997) 105#1, 54–82. * Lawrence, Jon. "Class and gender in the making of urban Toryism, 1880-1914." ''English Historical Review'' 108.428 (1993): 629–652

online

* * St John, Ian. ''The Historiography of Gladstone and Disraeli'' (2016) ch 3. * Saunders, Robert. “The Politics of Reform and the Making of the Second Reform Act, 1848-1867.” ''Historical Journal,'' 50#3 (2007), pp. 571–591

online

* Saunders, Robert. ''Democracy and the Vote in British Politics, 1848–1867: The Making of the Second Reform Act'' (2013)

excerpt

* Seghezza, Elena, and Pierluigi Morelli. "Suffrage extension, social identity, and redistribution: the case of the Second Reform Act." ''European Review of Economic History'' 23.1 (2018): 30–49. * * * Walton, John K. ''The Second Reform Act'' (1987) * Zimmerman, Kristin. "Liberal Speech, Palmerstonian Delay, and the Passage of the Second Reform Act." ''English Historical Review'' vol. 118 (November 2003): 1176–1202.

Primary sources

*External links

* *Digital reproduction of the Original Act on the Parliamentary Archives catalogue

{{UK electoral reform, state=expanded Representation of the People Acts United Kingdom Acts of Parliament 1867 August 1867 Benjamin Disraeli Edward Smith-Stanley, 14th Earl of Derby William Ewart Gladstone John Russell, 1st Earl Russell