second-wave feminist on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Second-wave feminism was a period of

The Post-war Novel and the Death of the Author

' (2020), Arya Aryan argues that although postmodern theorists saw their work as a radical break from tradition, their theories – whether deconstructive, poststructuralist or post-phenomenological – remain arguably patriarchal. Despite offering powerful critiques of authority and authorship, they largely overlook questions of gender. Concepts such as supplementarity and decentring may hold potential for exploring gendered power dynamics, yet these frameworks fail to engage explicitly with the issue of women as authors or with women’s writing as a critique of patriarchal notions of authorship. As Aryan puts it: Aryan argues that

In 1963, Betty Friedan, influenced by Simone de Beauvoir's ground-breaking, feminist ''The Second Sex'', wrote the bestselling book ''The Feminine Mystique''. Discussing primarily white women, she explicitly objected to how women were depicted in the mainstream media, and how placing them at home (as 'housewives') limited their possibilities and wasted potential. She had helped conduct a very important survey using her old classmates from

In 1963, Betty Friedan, influenced by Simone de Beauvoir's ground-breaking, feminist ''The Second Sex'', wrote the bestselling book ''The Feminine Mystique''. Discussing primarily white women, she explicitly objected to how women were depicted in the mainstream media, and how placing them at home (as 'housewives') limited their possibilities and wasted potential. She had helped conduct a very important survey using her old classmates from

''Infoplease.com''. Accessed December 28, 2013. Second-wave feminism also affected other movements, such as the civil rights movement and the student's rights movement, as women sought equality within them. In 1965 in "Sex and Caste", a reworking of a memo they had written as staffers in civil-rights organizations By the early 1980s, it was largely perceived that women had met their goals and succeeded in changing social attitudes towards gender roles, repealing oppressive laws that were based on sex, integrating the "boys' clubs" such as military academies, the

By the early 1980s, it was largely perceived that women had met their goals and succeeded in changing social attitudes towards gender roles, repealing oppressive laws that were based on sex, integrating the "boys' clubs" such as military academies, the

In 1963,

In 1963,

feminist

Feminism is a range of socio-political movements and ideology, ideologies that aim to define and establish the political, economic, personal, and social gender equality, equality of the sexes. Feminism holds the position that modern soci ...

activity that began in the early 1960s and lasted roughly two decades, ending with the feminist sex wars in the early 1980s and being replaced by third-wave feminism

Third-wave feminism is a feminist movement that began in the early 1990s, prominent in the decades prior to the fourth-wave feminism, fourth wave. Grounded in the civil-rights advances of the second-wave feminism, second wave, Generation X, Gen X ...

in the early 1990s. It occurred throughout the Western world

The Western world, also known as the West, primarily refers to various nations and state (polity), states in Western Europe, Northern America, and Australasia; with some debate as to whether those in Eastern Europe and Latin America also const ...

and aimed to increase women's equality by building on the feminist gains of the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Second-wave feminism built on first-wave feminism

First-wave feminism was a period of feminist activity and thought that occurred during the 19th and early 20th century throughout the Western world. It focused on De jure, legal issues, primarily on securing women's right to vote. The term is oft ...

and broadened the scope of debate to include a wider range of issues: sexuality, family, domesticity, the workplace, reproductive rights

Reproductive rights are legal rights and freedoms relating to human reproduction, reproduction and reproductive health that vary amongst countries around the world. The World Health Organization defines reproductive rights:

Reproductive rights ...

, ''de facto'' inequalities, and official legal inequalities. First-wave feminism typically advocated for formal equality and second-wave feminism advocated for substantive equality. It was a movement focused on critiquing patriarchal or male-dominated institutions and cultural practices throughout society. Second-wave feminism also brought attention to issues of domestic violence

Domestic violence is violence that occurs in a domestic setting, such as in a marriage

Marriage, also called matrimony or wedlock, is a culturally and often legally recognised union between people called spouses. It establishes r ...

and marital rape

Marital rape or spousal rape is the act of sexual intercourse with one's spouse without the spouse's consent. The lack of consent is the essential element and doesn't always involve physical violence. Marital rape is considered a form of dome ...

, created rape crisis centers and women's shelter

A women's shelter, also known as a women's refuge and battered women's shelter, is a place of temporary protection and support for women escaping domestic violence and intimate partner violence of all forms. The term is also frequently used to ...

s, and brought about changes in custody law and divorce law. Feminist-owned bookstores, credit unions, and restaurants were among the key meeting spaces and economic engines of the movement.

Because white feminists' voices have dominated the narrative from the early days of the movement, typical narratives of second-wave feminism focus on the sexism encountered by white middle- and upper-class women, with the absence of black and other women of color and the experience of working-class women, although women of color wrote and founded feminist political activist groups throughout the movement, especially in the 1970s. At the same time, some narratives present a perspective that focuses on events in the United States to the exclusion of the experiences of other countries. Writers like Audre Lorde

Audre Lorde ( ; born Audrey Geraldine Lorde; February 18, 1934 – November 17, 1992) was an American writer, professor, philosopher, Intersectional feminism, intersectional feminist, poet and civil rights activist. She was a self-described "Bl ...

argued that this homogenized vision of "sisterhood" could not lead to real change because it ignored factors of one's identity such as race, sexuality, age, and class. The term "intersectionality

Intersectionality is an analytical framework for understanding how groups' and individuals' social and political identities result in unique combinations of discrimination and privilege. Examples of these intersecting and overlapping factor ...

" was coined in 1989 by Kimberlé Crenshaw at the end of the second wave. Many scholars believe that the beginning of third wave feminism was due to the problems of the second wave, rather than just another movement.

Postmodern theories mark a significant historical moment and help define the dominant critical atmosphere of the period. In The Post-war Novel and the Death of the Author

' (2020), Arya Aryan argues that although postmodern theorists saw their work as a radical break from tradition, their theories – whether deconstructive, poststructuralist or post-phenomenological – remain arguably patriarchal. Despite offering powerful critiques of authority and authorship, they largely overlook questions of gender. Concepts such as supplementarity and decentring may hold potential for exploring gendered power dynamics, yet these frameworks fail to engage explicitly with the issue of women as authors or with women’s writing as a critique of patriarchal notions of authorship. As Aryan puts it: Aryan argues that

Roland Barthes

Roland Gérard Barthes (; ; 12 November 1915 – 25 March 1980) was a French literary theorist, essayist, philosopher, critic, and semiotician. His work engaged in the analysis of a variety of sign systems, mainly derived from Western popu ...

’ concept of the author who must be "killed" is inherently tied to masculinity. Aryan raises the critical question: "what if women, with few exceptions, have never had a voice to lose its origin, or what if they have never been treated as the site of origin in a piece of work at all?"

As Aryan contends, this issue became a key focus for many second-wave feminists, prompting them to challenge it directly. He argues that prior to the emergence of second-wave feminism, many women writers had already begun to assert and establish their own agency and subjectivity. As he notes, their writing "concerns with the patriarchal discourse that had dominated society and literary cultures by bringing to the fore obsessions and problems that had beset all women under patriarchy, but particularly women writers as they sought to counteract or challenge male dominated discourses."

Overview in the United States

The second wave of feminism in the United States came as a delayed reaction against the renewed domesticity of women afterWorld War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

: the late 1940s post-war boom, which was an era characterized by an unprecedented economic growth, a baby boom

A baby boom is a period marked by a significant increase of births. This demography, demographic phenomenon is usually an ascribed characteristic within the population of a specific nationality, nation or culture. Baby booms are caused by various ...

, a move to family-oriented suburbs and the ideal of companionate marriages. During this time, women did not tend to seek employment due to their engagement with domestic and household duties, which was seen as their primary duty but often left them isolated within the home and estranged from politics, economics, and law making. This life was clearly illustrated by the media of the time; for example television shows such as ''Father Knows Best

''Father Knows Best'' is an American sitcom starring Robert Young (actor), Robert Young, Jane Wyatt, Elinor Donahue, Billy Gray (actor), Billy Gray and Lauren Chapin. The series, which began on radio in 1949, aired as a television show for six ...

'' and ''Leave It to Beaver

''Leave It to Beaver'' is an American television sitcom that follows the misadventures of a suburban boy, his family and his friends. It starred Barbara Billingsley, Hugh Beaumont, Tony Dow and Jerry Mathers.

CBS first broadcast the show ...

'' idealized domesticity.

Some important events laid the groundwork for the second wave, specifically the work of French writer Simone de Beauvoir

Simone Lucie Ernestine Marie Bertrand de Beauvoir (, ; ; 9 January 1908 – 14 April 1986) was a French existentialist philosopher, writer, social theorist, and feminist activist. Though she did not consider herself a philosopher, nor was she ...

in the 1940s where she examined the notion of women being perceived as "other" in the patriarchal society. Simone de Beauvoir was an existentialist, meaning she believed in the existence of the individual person as a free and responsible agent determining their own development through acts of the will. She went on to conclude in her 1949 treatise ''The Second Sex

''The Second Sex'' () is a 1949 book by the French existentialist philosopher Simone de Beauvoir, in which the author discusses the treatment of women in the present society as well as throughout all of history. Beauvoir researched and wrote th ...

'' that male-centered ideology was being accepted as a norm and enforced by the ongoing development of myths, and that the fact that women are capable of getting pregnant, lactating, and menstruating is in no way a valid cause or explanation to place them as the "second sex". This book was translated from French to English (with some of its text excised) and published in America in 1953.

In 1960, the Food and Drug Administration

The United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA or US FDA) is a List of United States federal agencies, federal agency of the United States Department of Health and Human Services, Department of Health and Human Services. The FDA is respo ...

approved the combined oral contraceptive pill

The combined oral contraceptive pill (COCP), often referred to as the birth control pill or colloquially as "the pill", is a type of birth control that is designed to be Oral administration, taken orally by women. It is the oral form of combi ...

, which was made available in 1961. This made it easier for women to have careers without having to leave due to unexpectedly becoming pregnant. It also meant young couples would not be routinely forced into unwanted marriages due to accidental pregnancies.

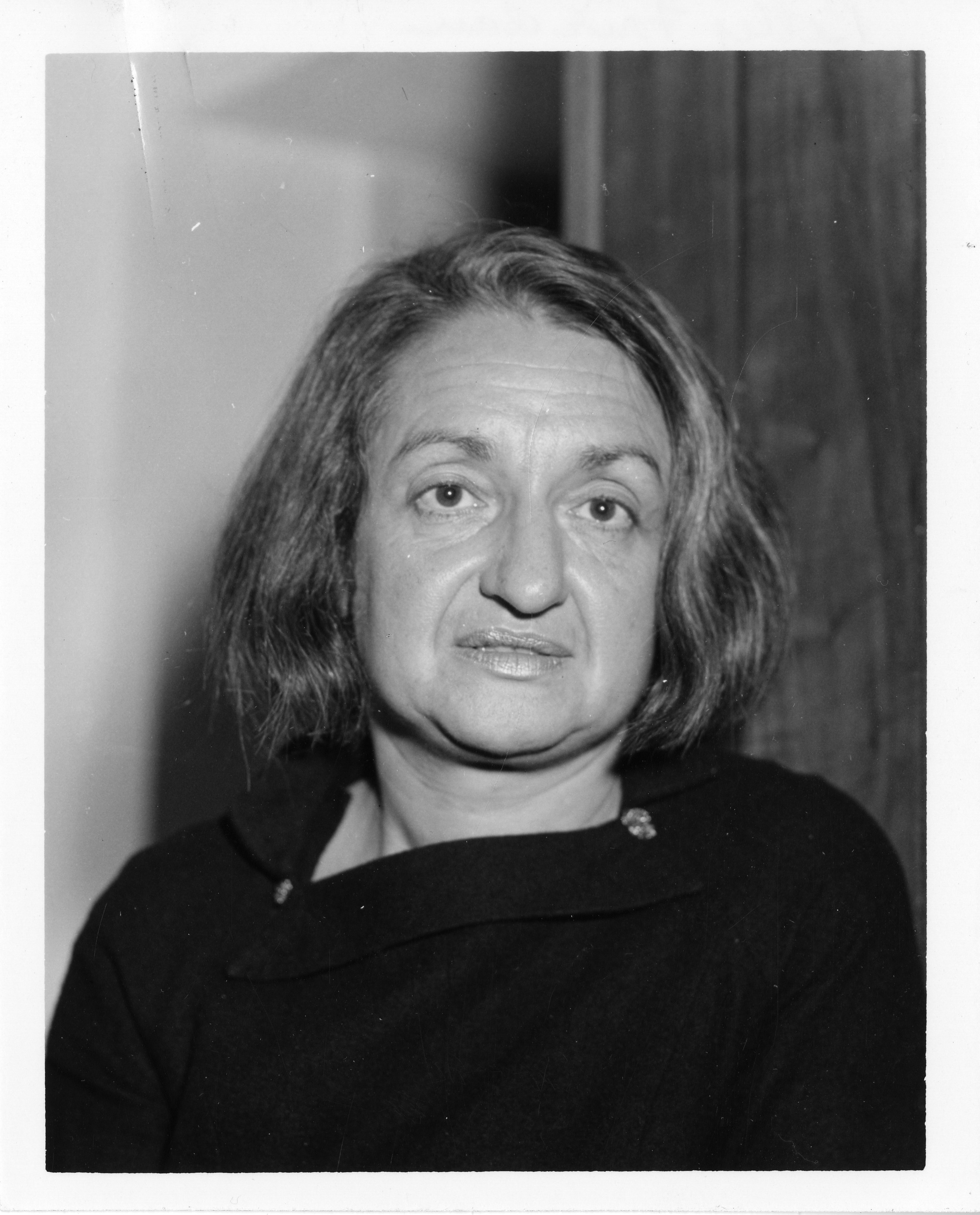

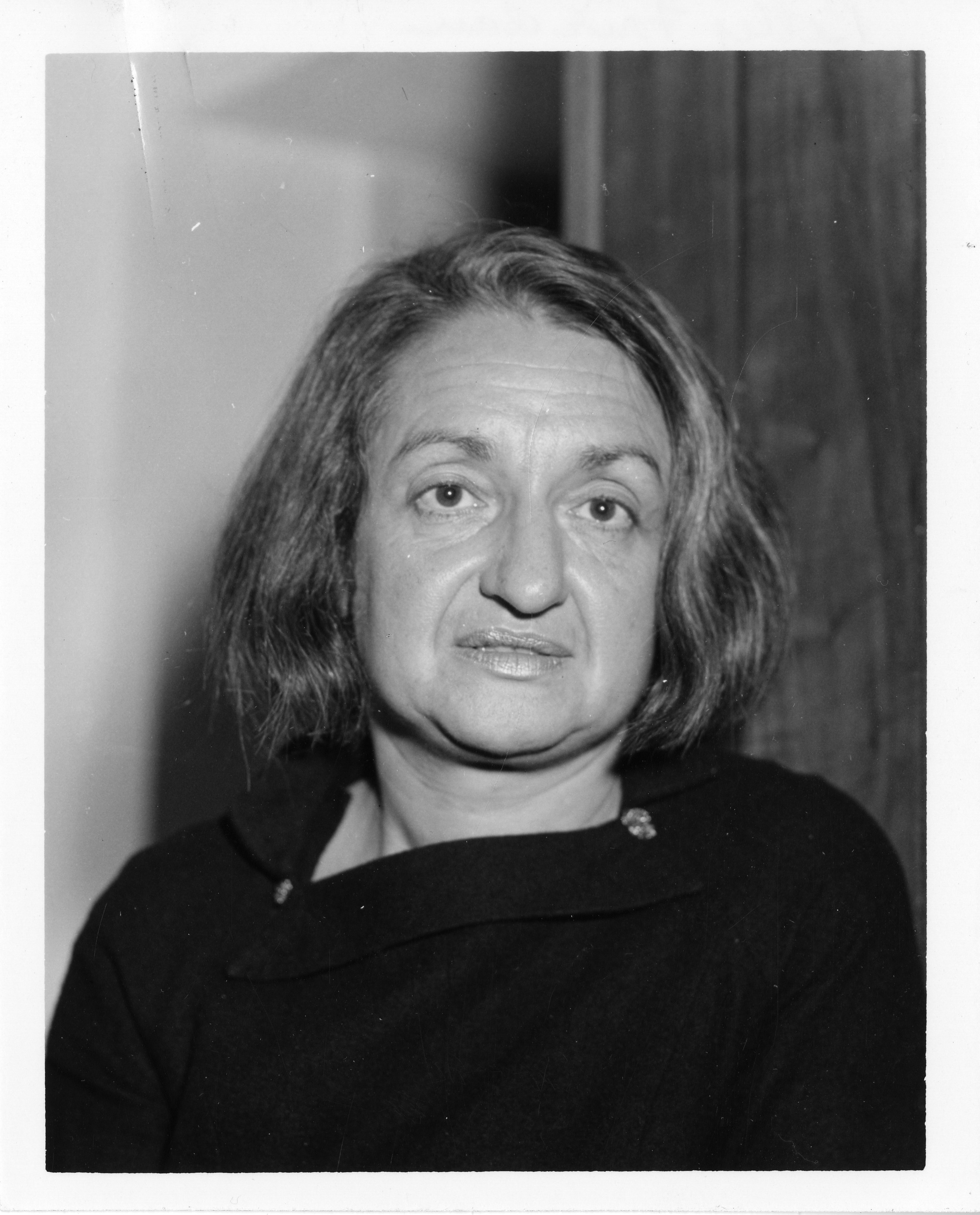

Though it is widely accepted that the movement lasted from the 1960s into the early 1980s, the exact years of the movement are more difficult to pinpoint and are often disputed. The movement is usually believed to have begun in 1963, when Betty Friedan

Betty Friedan (; February 4, 1921 – February 4, 2006) was an American feminist writer and activist. A leading figure in the women's movement in the United States, her 1963 book '' The Feminine Mystique'' is often credited with sparking the s ...

published ''The Feminine Mystique

''The Feminine Mystique'' is a book by American author Betty Friedan, widely credited with sparking second-wave feminism in the United States. First published by W. W. Norton on February 19, 1963, ''The Feminine Mystique'' became a bestseller, i ...

'', and President John F. Kennedy

John Fitzgerald Kennedy (May 29, 1917 – November 22, 1963), also known as JFK, was the 35th president of the United States, serving from 1961 until his assassination in 1963. He was the first Roman Catholic and youngest person elected p ...

's Presidential Commission on the Status of Women

The President's Commission on the Status of Women (PCSW) was established to advise the President of the United States on issues concerning the status of women. It was created by John F. Kennedy's signed December 14, 1961. In 1975 it became th ...

released its report on gender inequality.

The administration of President Kennedy made women's rights a key issue of the New Frontier

The term ''New Frontier'' was used by Democratic presidential candidate John F. Kennedy in his acceptance speech, delivered July 15, in the 1960 United States presidential election to the Democratic National Convention at the Los Angeles Memo ...

, and named women (such as Esther Peterson) to many high-ranking posts in his administration. Kennedy also established a Presidential Commission on the Status of Women

The President's Commission on the Status of Women (PCSW) was established to advise the President of the United States on issues concerning the status of women. It was created by John F. Kennedy's signed December 14, 1961. In 1975 it became th ...

, chaired by Eleanor Roosevelt

Anna Eleanor Roosevelt ( ; October 11, 1884November 7, 1962) was an American political figure, diplomat, and activist. She was the longest-serving First Lady of the United States, first lady of the United States, during her husband Franklin D ...

and comprising cabinet officials (including Peterson and Attorney General

In most common law jurisdictions, the attorney general (: attorneys general) or attorney-general (AG or Atty.-Gen) is the main legal advisor to the government. In some jurisdictions, attorneys general also have executive responsibility for law enf ...

Robert F. Kennedy), senators, representatives, businesspeople, psychologists, sociologists, professors, activists, and public servants. The report recommended changing this inequality by providing paid maternity leave, greater access to education, and help with child care to women. However, the extent of Kennedy's support for women's rights has been disputed, with some alleging that a major factor in his support included his efforts to cover up his own womanizing ways. His wife Jackie was also known for presenting herself as a traditional wife, including in the time after Friedan published ''The Feminine Mystique''. According to Yang Cao's historic analyses, ' the personal is political' may have influenced Eleanor Roosevelt's proposition in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) is an international document adopted by the United Nations General Assembly that enshrines the Human rights, rights and freedoms of all human beings. Drafted by a UN Drafting of the Universal D ...

.

There were other actions by women in wider society, presaging their wider engagement in politics which would come with the second wave. In 1961, 50,000 women in 60 cities, mobilized by Women Strike for Peace, protested above ground testing of nuclear bombs and tainted milk.

In 1963, Betty Friedan, influenced by Simone de Beauvoir's ground-breaking, feminist ''The Second Sex'', wrote the bestselling book ''The Feminine Mystique''. Discussing primarily white women, she explicitly objected to how women were depicted in the mainstream media, and how placing them at home (as 'housewives') limited their possibilities and wasted potential. She had helped conduct a very important survey using her old classmates from

In 1963, Betty Friedan, influenced by Simone de Beauvoir's ground-breaking, feminist ''The Second Sex'', wrote the bestselling book ''The Feminine Mystique''. Discussing primarily white women, she explicitly objected to how women were depicted in the mainstream media, and how placing them at home (as 'housewives') limited their possibilities and wasted potential. She had helped conduct a very important survey using her old classmates from Smith College

Smith College is a Private university, private Liberal arts colleges in the United States, liberal arts Women's colleges in the United States, women's college in Northampton, Massachusetts, United States. It was chartered in 1871 by Sophia Smit ...

. This survey revealed that the women who work in the workforce while also playing a role in the home were more satisfied with their life compared with the women who stayed home. The women who stayed home showed feelings of agitation and sadness. She concluded that many of these unhappy women had immersed themselves in the idea that they should not have any ambitions outside their home. Friedan described this as "The Problem That Has No Name". The perfect nuclear family

A nuclear family (also known as an elementary family, atomic family, or conjugal family) is a term for a family group consisting of parents and their children (one or more), typically living in one home residence. It is in contrast to a single ...

image depicted and strongly marketed at the time, she wrote, did not reflect happiness and was rather degrading for women. This book is widely credited with having begun second-wave feminism in the United States. The problems of the nuclear family in America are also heteronormative and is utilized often as a marketing strategy to sell goods within a capitalist driven society.

The report from the Presidential Commission on the Status of Women, along with Friedan's book, spoke to the discontent of many women (especially housewives

A housewife (also known as a homemaker or a stay-at-home mother/mom/mum) is a woman whose role is running or managing her family's home—housekeeping, which may include Parenting, caring for her children; cleaning and maintaining the home; Sew ...

) and led to the formation of local, state, and federal government women's groups along with many independent feminist organizations. Friedan was referencing a "movement" as early as 1964.

The movement grew with legal victories such as the Equal Pay Act of 1963

The Equal Pay Act of 1963 is a United States labor law amending the Fair Labor Standards Act, aimed at abolishing wage disparity based on sex (see gender pay gap). It was signed into law on June 10, 1963, by John F. Kennedy as part of his New F ...

, Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 () is a landmark civil rights and labor law in the United States that outlaws discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex, and national origin. It prohibits unequal application of voter registration requi ...

, and the ''Griswold v. Connecticut

''Griswold v. Connecticut'', 381 U.S. 479 (1965), is a landmark decision of the U.S. Supreme Court in which the Court ruled that the Constitution of the United States protects the liberty of married couples to use contraceptives without gove ...

'' Supreme Court

In most legal jurisdictions, a supreme court, also known as a court of last resort, apex court, high (or final) court of appeal, and court of final appeal, is the highest court within the hierarchy of courts. Broadly speaking, the decisions of ...

ruling of 1965. In 1966 Friedan joined other women and men to found the National Organization for Women

The National Organization for Women (NOW) is an American feminist organization. Founded in 1966, it is legally a 501(c)(4) social welfare organization. The organization consists of 550 chapters in all 50 U.S. states and in Washington, D.C. It ...

(NOW); Friedan would be named as the organization's first president.

Despite the early successes NOW achieved under Friedan's leadership, her decision to pressure the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission

The U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) is a federal agency that was established via the Civil Rights Act of 1964 to administer and enforce civil rights laws against workplace discrimination. The EEOC investigates discrimination ...

(EEOC) to use Title VII of the 1964 Civil Rights Act to enforce more job opportunities among American women met with fierce opposition within the organization. Siding with arguments among several of the group's African-American members, many of NOW's leaders were convinced that the vast number of male African-Americans who lived below the poverty line were in need of more job opportunities than women within the middle and upper class. Friedan stepped down as president in 1969.

In 1963, freelance journalist Gloria Steinem

Gloria Marie Steinem ( ; born March 25, 1934) is an American journalist and social movement, social-political activist who emerged as a nationally recognized leader of second-wave feminism in the United States in the late 1960s and early 1970s. ...

gained widespread popularity among feminists after a diary she authored while working undercover as a Playboy Bunny

A Playboy Bunny is a cocktail waitress who works at a Playboy Club and selected through standardized training. Their costumes were made up of lingerie, inspired by the tuxedo-wearing Playboy rabbit mascot. This costume consisted of a straples ...

waitress at the Playboy Club

The Playboy Club was initially a chain of nightclubs and resorts owned and operated by Playboy Enterprises. The first Playboy Club opened in Chicago in 1960. Each club generally featured a Living Room, a Playmate Bar, a Dining Room, and a Club ...

was published as a two-part feature in the May and June issues of '' Show''. In her diary, Steinem alleged the club was mistreating its waitresses in order to gain male customers and exploited the Playboy Bunnies as symbols of male chauvinism, noting that the club's manual instructed the Bunnies that "there are many pleasing ways they can employ to stimulate the club's liquor volume". By 1968, Steinem had become arguably the most influential figure in the movement and support for legalized abortion

Abortion is the early termination of a pregnancy by removal or expulsion of an embryo or fetus. Abortions that occur without intervention are known as miscarriages or "spontaneous abortions", and occur in roughly 30–40% of all pregnan ...

and federally funded day-cares had become the two leading objectives for feminists.

Among the most significant legal victories of the movement after the formation of NOW were a 1967 Executive Order extending full affirmative action

Affirmative action (also sometimes called reservations, alternative access, positive discrimination or positive action in various countries' laws and policies) refers to a set of policies and practices within a government or organization seeking ...

rights to women, a 1968 EEOC decision ruling illegal sex-segregated help wanted ads, Title IX

Title IX is a landmark federal civil rights law in the United States that was enacted as part (Title IX) of the Education Amendments of 1972. It prohibits sex-based discrimination in any school or any other education program that receiv ...

and the Women's Educational Equity Act

The Women's Educational Equity Act (WEEA) of 1974 is one of the several landmark laws passed by the United States Congress outlining federal protections against the gender discrimination of women in education (educational equity). WEEA was enacte ...

(1972 and 1974, respectively, educational equality), Title X (1970, health and family planning), the Equal Credit Opportunity Act

The Equal Credit Opportunity Act (ECOA) is a United States law (codified at et seq.), enacted October 28, 1974, that makes it unlawful for any creditor to discriminate against any applicant, with respect to any aspect of a credit transaction, ...

(1974), the Pregnancy Discrimination Act of 1978

The Pregnancy Discrimination Act (PDA) of 1978 () is a United States federal statute. It amended Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 to "prohibit sex discrimination on the basis of pregnancy."

The Act covers discrimination "on the basis o ...

, the outlawing of marital rape

Marital rape or spousal rape is the act of sexual intercourse with one's spouse without the spouse's consent. The lack of consent is the essential element and doesn't always involve physical violence. Marital rape is considered a form of dome ...

(although not outlawed in all states until 1993), and the legalization of no-fault divorce

No-fault divorce is the dissolution of a marriage that does not require a showing of wrongdoing by either party. Laws providing for no-fault divorce allow a family court to grant a divorce in response to a petition by either party of the marria ...

(although not legalized in all states until 2010), a 1975 law requiring the U.S. Military Academies to admit women, and many Supreme Court cases such as ''Reed v. Reed

''Reed v. Reed'', 404 U.S. 71 (1971), was a List of landmark court decisions in the United States, landmark decision of the Supreme Court of the United States holding that the administrators of Estate (law), estates cannot be named in a way that d ...

'' of 1971 and ''Roe v. Wade

''Roe v. Wade'', 410 U.S. 113 (1973),. was a List of landmark court decisions in the United States, landmark decision of the U.S. Supreme Court in which the Court ruled that the Constitution of the United States protected the right to have an ...

'' of 1973. However, the changing of social attitudes towards women is usually considered the greatest success of the women's movement. In January 2013, US Secretary of Defense Leon Panetta

Leon Edward Panetta (born June 28, 1938) is an American retired politician and government official who has served under several Democratic administrations as secretary of defense (2011–2013), director of the CIA (2009–2011), White House chi ...

announced that the longtime ban on women serving in US military combat roles had been lifted.

In 2013, the US Department of Defense

The United States Department of Defense (DoD, USDOD, or DOD) is an executive department of the U.S. federal government charged with coordinating and supervising the six U.S. armed services: the Army, Navy, Marines, Air Force, Space Force, ...

(DoD) announced their plan to integrate women into all combat positions by 2016.A History of Women in the U.S. Military''Infoplease.com''. Accessed December 28, 2013. Second-wave feminism also affected other movements, such as the civil rights movement and the student's rights movement, as women sought equality within them. In 1965 in "Sex and Caste", a reworking of a memo they had written as staffers in civil-rights organizations

SNCC

The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, and later, the Student National Coordinating Committee (SNCC, pronounced ) was the principal channel of student commitment in the United States to the civil rights movement during the 1960s. Emer ...

, Casey Hayden and Mary King proposed that "assumptions of male superiority are as widespread and deep rooted and every much as crippling to the woman as the assumptions of white supremacy are to the Negro", and that in the movement, as in society, women can find themselves "caught up in a common-law caste system".

In June 1967, Jo Freeman attended a "free school" course on women at the University of Chicago led by Heather Booth and Naomi Weisstein. She invited them to organize a woman's workshop at the then-forthcoming National Conference of New Politics (NCNP), to be held over Labor Day

Labor Day is a Federal holidays in the United States, federal holiday in the United States celebrated on the first Monday of September to honor and recognize the Labor history of the United States, American labor movement and the works and con ...

weekend 1967 in Chicago

Chicago is the List of municipalities in Illinois, most populous city in the U.S. state of Illinois and in the Midwestern United States. With a population of 2,746,388, as of the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, it is the List of Unite ...

. At that conference, a woman's caucus was formed (led by Freeman and Shulamith Firestone), who tried to present their own demands to the plenary session. However, the women were told their resolution was not important enough for a floor discussion, and when through threatening to tie up the convention with procedural motions they succeeded in having their statement tacked to the end of the agenda, it was never discussed. When the National Conference for New Politics (NCNP) Director William F. Pepper refused to recognize any of the women waiting to speak and instead called on someone to speak about American Indians, five women, including Firestone, rushed the podium demanding to know why. But Willam F. Pepper allegedly patted Firestone on the head and said, "Move on little girl; we have more important issues to talk about here than women's liberation", or possibly, "Cool down, little girl. We have more important things to talk about than women's problems." Freeman and Firestone called a meeting of the women who had been at the "free school" course and the women's workshop at the conference; this became the first Chicago women's liberation

The women's liberation movement (WLM) was a political alignment of women and feminism, feminist intellectualism. It emerged in the late 1960s and continued till the 1980s, primarily in the industrialized nations of the Western world, which resu ...

group. It was known as the Westside group because it met weekly in Freeman's apartment on Chicago's west side. After a few months, Freeman started a newsletter which she called ''Voice of the women's liberation movement.'' It circulated all over the country (and in a few foreign countries), giving the new movement of women's liberation its name. Many of the women in the Westside group went on to start other feminist organizations, including the Chicago Women's Liberation Union.

In 1968, an SDS organizer at the University of Washington

The University of Washington (UW and informally U-Dub or U Dub) is a public research university in Seattle, Washington, United States. Founded in 1861, the University of Washington is one of the oldest universities on the West Coast of the Uni ...

told a meeting about white college men working with poor white men, and " noted that sometimes after analyzing societal ills, the men shared leisure time by 'balling a chick together.' He pointed out that such activities did much to enhance the political consciousness of poor white youth. A woman in the audience asked, 'And what did it do for the consciousness of the chick? (Hole, Judith, and Ellen Levine, ''Rebirth of Feminism'', 1971, pg. 120). After the meeting, a handful of women formed Seattle

Seattle ( ) is the most populous city in the U.S. state of Washington and in the Pacific Northwest region of North America. With a population of 780,995 in 2024, it is the 18th-most populous city in the United States. The city is the cou ...

's first women's liberation group.

The term "second-wave feminism" itself was brought into common parlance by American journalist Martha Lear in a March 1968 ''New York Times Magazine

''The New York Times Magazine'' is an American Sunday magazine included with the Sunday edition of ''The New York Times''. It features articles longer than those typically in the newspaper and has attracted many notable contributors. The magazin ...

'' article titled "The Second Feminist Wave: What Do These Women Want?". She wrote, "Proponents call it the Second Feminist Wave, the first having ebbed after the glorious victory of suffrage

Suffrage, political franchise, or simply franchise is the right to vote in public, political elections and referendums (although the term is sometimes used for any right to vote). In some languages, and occasionally in English, the right to v ...

and disappeared, finally, into the great sandbar of Togetherness." The term ''wave'' helped link the generation of suffragettes who fought for legal rights to the feminists of the 1960s and '70s. It is now used to not only distinguish the different priorities in feminism throughout the years but to establish an overarching fight for equity and equality as a way of understanding its history. This metaphor however is critiqued by feminists as it generalizes the contradictions within the movement and the different beliefs that feminists hold.

Some black feminists who were active in the early second-wave feminism include civil rights lawyer and author Florynce Kennedy

Florynce Rae Kennedy (February 11, 1916 – December 21, 2000) was an American lawyer, radical feminist, civil rights advocate, lecturer, and activist.

Early life

Kennedy was born in Kansas City, Missouri, to Wiley Kennedy and Zella Rae Jackman ...

, who co-authored one of the first books on abortion, 1971's ''Abortion Rap''; Cellestine Ware, of New York's Stanton-Anthony Brigade; and Patricia Robinson. These women "tried to show the connections between racism and male dominance" in society.

The Indochinese Women's Conferences (IWC) in Vancouver and Toronto in 1971, demonstrated the interest of a multitude of women's groups in the Vietnam Antiwar movement. Lesbian groups, women of color, and Vietnamese groups saw their interests mirrored in the anti-imperialist spirit of the conference. Although the IWC used a Canadian venue, membership was primarily composed of American groups.

The ideals of liberal feminism

Liberal feminism, also called mainstream feminism, is a main branch of feminism defined by its focus on achieving gender equality through political and legal reform within the framework of liberal democracy and informed by a human rights per ...

worked towards the idea of women's equality with that of men because liberal feminists felt that women and men have the same intrinsic capabilities and that society has socialized certain skills out. This elimination of difference works to erase sexism by working within a pre-existing system of oppression rather than challenging the system itself. Working towards equality preserves a system by giving everyone the same opportunities regardless of their privilege whereas the framework of equity would address problems in society and find solutions to target the problem at hand.

The second wave of the feminist movement also marks the emergence of women's studies

Women's studies is an academic field that draws on Feminism, feminist and interdisciplinary methods to place women's lives and experiences at the center of study, while examining Social constructionism, social and cultural constructs of gender; ...

as a legitimate field of study. In 1970, San Diego State University

San Diego State University (SDSU) is a Public university, public research university in San Diego, California, United States. Founded in 1897, it is the third-oldest university and southernmost in the 23-member California State University (CS ...

was the first university in the United States to offer a selection of women's studies courses.

The 1977 National Women's Conference in Houston

Houston ( ) is the List of cities in Texas by population, most populous city in the U.S. state of Texas and in the Southern United States. Located in Southeast Texas near Galveston Bay and the Gulf of Mexico, it is the county seat, seat of ...

, Texas, presented an opportunity for women's liberation groups to address a multitude of women's issues. At the conference, delegates from around the country gathered to create a National Plan of Action, which offered 26 planks on matters such as women's health, women's employment, and child care.  By the early 1980s, it was largely perceived that women had met their goals and succeeded in changing social attitudes towards gender roles, repealing oppressive laws that were based on sex, integrating the "boys' clubs" such as military academies, the

By the early 1980s, it was largely perceived that women had met their goals and succeeded in changing social attitudes towards gender roles, repealing oppressive laws that were based on sex, integrating the "boys' clubs" such as military academies, the United States Armed Forces

The United States Armed Forces are the Military, military forces of the United States. U.S. United States Code, federal law names six armed forces: the United States Army, Army, United States Marine Corps, Marine Corps, United States Navy, Na ...

, NASA

The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA ) is an independent agencies of the United States government, independent agency of the federal government of the United States, US federal government responsible for the United States ...

, single-sex colleges, men's clubs, and the Supreme Court

In most legal jurisdictions, a supreme court, also known as a court of last resort, apex court, high (or final) court of appeal, and court of final appeal, is the highest court within the hierarchy of courts. Broadly speaking, the decisions of ...

, and making gender discrimination illegal. However, in 1982, adding the Equal Rights Amendment

The Equal Rights Amendment (ERA) was a proposed amendment to the Constitution of the United States, United States Constitution that would explicitly prohibit sex discrimination. It is not currently a part of the Constitution, though its Ratifi ...

to the United States Constitution

The Constitution of the United States is the Supremacy Clause, supreme law of the United States, United States of America. It superseded the Articles of Confederation, the nation's first constitution, on March 4, 1789. Originally includi ...

failed, having been ratified by only 35 states, leaving it three states short of ratification.

Second-wave feminism was largely successful, with the failure of the ratification of the Equal Rights Amendment and Nixon

Richard Milhous Nixon (January 9, 1913April 22, 1994) was the 37th president of the United States, serving from 1969 until his resignation in 1974. A member of the Republican Party, he previously served as the 36th vice president under P ...

's veto of the Comprehensive Child Development Bill of 1972 (which would have provided a multibillion-dollar national day care system) the only major legislative defeats. Efforts to ratify the Equal Rights Amendment have continued. Ten states have adopted constitutions or constitutional amendments providing that equal rights under the law shall not be denied because of sex, and most of these provisions mirror the broad language of the Equal Rights Amendment. Furthermore, many women's groups are still active and are major political forces. , more women earn bachelor's degree

A bachelor's degree (from Medieval Latin ''baccalaureus'') or baccalaureate (from Modern Latin ''baccalaureatus'') is an undergraduate degree awarded by colleges and universities upon completion of a course of study lasting three to six years ...

s than men, half of the Ivy League

The Ivy League is an American collegiate List of NCAA conferences, athletic conference of eight Private university, private Research university, research universities in the Northeastern United States. It participates in the National Collegia ...

presidents are women, the numbers of women in government and traditionally male-dominated fields have dramatically increased, and in 2009 the percentage of women in the American workforce temporarily surpassed that of men. The salary of the average American woman has also increased over time, although as of 2008 it is only 77% of the average man's salary, a phenomenon often referred to as the gender pay gap

The gender pay gap or gender wage gap is the average difference between the remuneration for men and women who are Employment, employed. Women are generally found to be paid less than men. There are two distinct measurements of the pay gap: non ...

. Whether this is due to discrimination is very hotly disputed, however economists and sociologists have provided evidence to that effect.

The movement was also fought alongside the civil rights

Civil and political rights are a class of rights that protect individuals' political freedom, freedom from infringement by governments, social organizations, and private individuals. They ensure one's entitlement to participate in the civil and ...

, Black power

Black power is a list of political slogans, political slogan and a name which is given to various associated ideologies which aim to achieve self-determination for black people. It is primarily, but not exclusively, used in the United States b ...

, Chicano

Chicano (masculine form) or Chicana (feminine form) is an ethnic identity for Mexican Americans that emerged from the Chicano Movement.

In the 1960s, ''Chicano'' was widely reclaimed among Hispanics in the building of a movement toward politic ...

and gay liberation

The gay liberation movement was a social and political movement of the late 1960s through the mid-1980s in the Western world, that urged lesbians and gay men to engage in radical direct action, and to counter societal shame with gay pride.Hoff ...

movements, where many feminists were active participants throughout these fights for a voice in the United States.

Many historians view the second-wave feminist era in America as ending in the early 1980s with intra-feminism disputes of the feminist sex wars over issues such as sexuality

Human sexuality is the way people experience and express themselves sexually. This involves biological, psychological, physical, erotic, emotional, social, or spiritual feelings and behaviors. Because it is a broad term, which has varied ...

and pornography

Pornography (colloquially called porn or porno) is Sexual suggestiveness, sexually suggestive material, such as a picture, video, text, or audio, intended for sexual arousal. Made for consumption by adults, pornographic depictions have evolv ...

, which ushered in the era of third-wave feminism

Third-wave feminism is a feminist movement that began in the early 1990s, prominent in the decades prior to the fourth-wave feminism, fourth wave. Grounded in the civil-rights advances of the second-wave feminism, second wave, Generation X, Gen X ...

in the early 1990s.As noted in:

*

*

*

*

*

"The Feminine Mystique"

In 1963,

In 1963, Betty Friedan

Betty Friedan (; February 4, 1921 – February 4, 2006) was an American feminist writer and activist. A leading figure in the women's movement in the United States, her 1963 book '' The Feminine Mystique'' is often credited with sparking the s ...

published her book ''The Feminine Mystique

''The Feminine Mystique'' is a book by American author Betty Friedan, widely credited with sparking second-wave feminism in the United States. First published by W. W. Norton on February 19, 1963, ''The Feminine Mystique'' became a bestseller, i ...

'' addressing the issues that many white-middle class housewives were facing at the time. Friedan's work catalyzed the second wave, and in particular the liberal feminist sector of the movement. Her work gave these women the language to be able to articulate the dissatisfaction they felt in their role of being a mother and a wife. Friedan coined the term "Feminine Mystique" to recognize the romanticization of being a "happy housewife" perpetuated by media such as TV and magazines and that women should feel satisfied with housework, marriage, child-rearing, and passivity around the home unit. Women were always seen as relational to the other people in their life and were not encouraged to have their own identity as a person with their own life and interests beyond the home. They are either seen as someone's wife or someone's mother. Women who read her work were able to realize that they were not alone in their feelings. Friedan's work only brought to life a problem experienced by a certain group of women however which left out women of color and who belonged to other marginalized groups since many of these people had to work outside the home for a source of income.

Overview outside the United States

In 1967, at theInternational Alliance of Women

The International Alliance of Women (IAW; , AIF) is an international non-governmental organization that works to promote women's rights and gender equality. It was historically the main international organization that campaigned for women's suff ...

Congress held in London, delegates were made aware of an initiative by the UN Commission on the Status of Women to study and evaluate the situation of women in their countries. Many organizations and NGOs like the Association of Business and Professional Women, Soroptimists Clubs, as well as teaching and nursing associations developed committees in response to the initiative to prepare evaluations on the conditions of women and urge their governments to establish National Commissions on the Status of Women.

In Turkey

Turkey, officially the Republic of Türkiye, is a country mainly located in Anatolia in West Asia, with a relatively small part called East Thrace in Southeast Europe. It borders the Black Sea to the north; Georgia (country), Georgia, Armen ...

and Israel

Israel, officially the State of Israel, is a country in West Asia. It Borders of Israel, shares borders with Lebanon to the north, Syria to the north-east, Jordan to the east, Egypt to the south-west, and the Mediterranean Sea to the west. Isr ...

, second-wave feminism began in the 1980s.

Australia

The Regatta Hotel protest in 1965 that challenged the ban on women being served drinks in public bars inQueensland

Queensland ( , commonly abbreviated as Qld) is a States and territories of Australia, state in northeastern Australia, and is the second-largest and third-most populous state in Australia. It is bordered by the Northern Territory, South Austr ...

marked the beginning of second wave feminist action in Brisbane

Brisbane ( ; ) is the List of Australian capital cities, capital and largest city of the States and territories of Australia, state of Queensland and the list of cities in Australia by population, third-most populous city in Australia, with a ...

and gained significant media coverage. Kay Saunders notes, "when you use the term ‘‘second wave’’ it actually started in Brisbane." In 1970 the law was changed to allow women to be served drinks in public bars in Queensland.

Finland

In the 1960s, feminism again became a part of debate in Finland after the publication of Anna-Liisa Sysiharjun's ''Home, Equality and Work'' (1960) and Elina Haavio-Mannilan's (1968), and the student feminist group Yhystis 9 (1966–1970) addressed issues such as the need for free abortions. In 1970, there was a brief but strong women's movement belonging to second wave feminism. Rape in marriage was not considered a crime at the time, and victims ofdomestic violence

Domestic violence is violence that occurs in a domestic setting, such as in a marriage

Marriage, also called matrimony or wedlock, is a culturally and often legally recognised union between people called spouses. It establishes r ...

had few places to go. Feminists also fought for a day-care

Child care, also known as day care, is the care and supervision of one or more children, typically ranging from three months to 18 years old. Although most parents spend a significant amount of time caring for their child(ren), childcare typica ...

system that would be open to the public, and for the right for not only paid maternity leave but also paternity leave. Today there is a 263-day parental leave

Parental leave, or family leave, is an employee benefit available in almost all countries. The term "parental leave" may include maternity, paternity, and adoption leave; or may be used distinctively from "maternity leave" and "paternity leave ...

in Finland. It is illegal to discriminate against women in the workforce

Since the Industrial Revolution, participation of women in the workforce outside the home has increased in industrialized nations, with particularly large growth seen in the 20th century. Largely seen as a boon for industrial society, women ...

. Two feminist groups were created to help the movement: The Marxist-Feminists () and The Red Women (, ). The feminists in Finland were inspired by other European countries such as Sweden

Sweden, formally the Kingdom of Sweden, is a Nordic countries, Nordic country located on the Scandinavian Peninsula in Northern Europe. It borders Norway to the west and north, and Finland to the east. At , Sweden is the largest Nordic count ...

and Switzerland

Switzerland, officially the Swiss Confederation, is a landlocked country located in west-central Europe. It is bordered by Italy to the south, France to the west, Germany to the north, and Austria and Liechtenstein to the east. Switzerland ...

. Other important groups for the Finnish women in the 1970s include Unioni and The Feminists ().

Germany

During the 1960s, several German feminist groups were founded, which were characterized as the second wave.Ireland

The Irish Women's Liberation Movement was an alliance of a group of Irish women who were concerned about the sexism within Ireland both socially and legally. They first began after a meeting in Dublin's Bewley's Cafe on Grafton Street in 1970. They later had their meetings in Margaret Gaj's restaurant on Baggot Street every Monday. The group was short-lived, but influential. It was initially started with twelve women, most of whom werejournalist

A journalist is a person who gathers information in the form of text, audio or pictures, processes it into a newsworthy form and disseminates it to the public. This is called journalism.

Roles

Journalists can work in broadcast, print, advertis ...

s. One of the co-founders was June Levine.

In 1971, a group of Irish feminists (including June Levine, Mary Kenny

Mary Kenny (born 4 April 1944) is an Irish journalist, broadcaster and playwright. A founding member of the Irish Women's Liberation Movement, she was one of the country's first and foremost Feminism, feminists, often contributes columns to the ...

, Nell McCafferty, Máirín Johnston, and other members of the Irish Women's Liberation Movement) travelled to Belfast

Belfast (, , , ; from ) is the capital city and principal port of Northern Ireland, standing on the banks of the River Lagan and connected to the open sea through Belfast Lough and the North Channel (Great Britain and Ireland), North Channel ...

, Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland ( ; ) is a Countries of the United Kingdom, part of the United Kingdom in the north-east of the island of Ireland. It has been #Descriptions, variously described as a country, province or region. Northern Ireland shares Repub ...

, on the so-called " Contraceptive Train" and returned with condom

A condom is a sheath-shaped Barrier contraception, barrier device used during sexual intercourse to reduce the probability of pregnancy or a Sexually transmitted disease, sexually transmitted infection (STI). There are both external condo ...

s, which were then illegal in Ireland.

In 1973, a group of feminists, chaired by Hilda Tweedy of the Irish Housewives Association, set up the Council for the Status of Women, with the goal of gaining equality for women. It was an umbrella body for women's groups. During the 1990s the council's activities included supporting projects funded by the European Social Fund

The European Social Fund Plus (ESF+) is one of the European Structural and Investment Funds (ESIFs), which are dedicated to improving social cohesion and economic well-being across the regions of the Union. The funds are redistributive financi ...

, and running Women and Leadership Programmes and forums. In 1995, following a strategic review, it changed its name to the National Women's Council of Ireland.

Spain

The 1960s in Spain saw a generational shift in Spanish feminist in response to other changes in Spanish society. This included increased emigration and tourism (resulting in the spread of ideas from the rest of the world), greater opportunities in education and employment for women and major economic reforms.Nielfa Cristóbal, Gloria. ''Movimientos femeninos'', en ''Enciclopedia Madrid S.XX'' Feminism in the late Franco period and early transition period was not unified. It had many different political dimensions, however, they all shared a belief in the need for greater equality for women in Spain and a desire to defend the rights of women. Feminism moved from being about the individual to being about the collective. It was during this period that second-wave feminism arrived in Spain. Second-wave Spanish feminism was about the struggle for the rights of women in the context of the dictatorship. PCE would start in 1965 to promote this movement with MDM, creating a feminist political orientation around building solidarity for women and assisting imprisoned political figures. MDM launched its movement in Madrid by establishing associations among the housewives of the Tetuán andGetafe

Getafe () is a municipalities in Spain, municipality and a city in Spain belonging to the Community of Madrid. , it has a population of 180,747, the region's sixth most populated municipality.

Getafe is located 13 km south of Madrid's city c ...

in 1969. In 1972, Asociación Castellana de Amas de Casa y Consumidora was created to widen the group's ability to attract members.

Second-wave feminism entered the Spanish comic community by the early 1970s. It was manifested in Spanish comics in two ways. The first was that it increased the number of women involved in comics production as writers and artists. The second was it transformed how female characters were portrayed, making women less passive and less likely to be purely sexual beings.

Sweden

:''See also Feminism in Sweden'' In Sweden, second-wave feminism is mostly associated withGroup 8 Group 8 may refer to:

* Group 8 (Sweden), a feminist movement in Sweden

* Group 8 element, a series of elements in the Periodic Table

* Group 8 Rugby League, a rugby league competition

* G8, or Group of 8, an inter-governmental political forum f ...

, a feminist organization which was founded by eight women in Stockholm in 1968.

The organization took up various feminist issues such as demands for expansions of kindergartens, 6-hour working day, equal pay for equal work and opposition to pornography. Initially based in Stockholm, local groups were founded throughout the country. The influence of Group 8 on feminism in Sweden is still prevalent.

The Netherlands

In 1967, "The Discontent of Women", by Joke Kool-Smits, was published; the publication of this essay is often regarded as the start of second-wave feminism in the Netherlands. In this essay, Smit describes the frustration of married women, saying they are fed up being solely mothers and housewives.Beginning and consciousness raising

The beginnings of second-wave feminism can be studied by looking at the two branches that the movement formed in: theliberal feminists

Liberal feminism, also called mainstream feminism, is a main branch of feminism defined by its focus on achieving gender equality through political reform, political and legal reform within the framework of liberal democracy and informed by a ...

and the radical feminists. The liberal feminists, led by figures such as Betty Friedan and Gloria Steinem advocated for federal legislation to be passed that would promote and enhance the personal and professional lives of women. On the other hand, radical feminists, such as Casey Hayden and Mary King, adopted the skills and lessons that they had learned from their work with student organizations such as the Students for a Democratic Society

Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) was a national student activist organization in the United States during the 1960s and was one of the principal representations of the New Left. Disdaining permanent leaders, hierarchical relationships a ...

and Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee

The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, and later, the Student National Coordinating Committee (SNCC, pronounced ) was the principal channel of student commitment in the United States to the civil rights movement during the 1960s. Emer ...

and created a platform to speak on the violent and sexist issues women faced while working with the larger Civil Rights Movement.

The liberal feminist movement

After being removed from the workforce, by either personal orsocial pressure

Peer pressure is a direct or indirect influence on peers, i.e., members of social groups with similar interests and experiences, or social statuses. Members of a peer group are more likely to influence a person's beliefs, values, religion and beh ...

s, many women in the post-war America returned to the home or were placed into female only jobs in the service sector. After the publication of Friedan's ''The Feminine Mystique'' in 1963, many women connected to the feeling of isolation and dissatisfaction that the book detailed. The book itself, however, was not a call to action, but rather a plea for self-realization and consciousness raising

Consciousness raising (also called awareness raising) is a form of activism popularized by United States feminists in the late 1960s. It often takes the form of a group of people attempting to focus the attention of a wider group on some cause or ...

among middle-class women throughout America. Many of these women organized to form the National Organization for Women

The National Organization for Women (NOW) is an American feminist organization. Founded in 1966, it is legally a 501(c)(4) social welfare organization. The organization consists of 550 chapters in all 50 U.S. states and in Washington, D.C. It ...

in 1966, whose "Statement of Purpose" declared that the right women had to equality was one small part of the nationwide civil rights revolution that was happening during the 1960s.

The radical feminist movement

Women who favoured radical feminism collectively spoke of being forced to remain silent and obedient to male leaders inNew Left

The New Left was a broad political movement that emerged from the counterculture of the 1960s and continued through the 1970s. It consisted of activists in the Western world who, in reaction to the era's liberal establishment, campaigned for freer ...

organizations. They spoke out about how they were not only told to do clerical work such as stuffing envelopes and typing speeches, but there was also an expectation for them to sleep with the male activists that they worked with. While these acts of sexual harassment took place, the young women were neglected their right to have their own needs and desires recognized by their male cohorts. Many radical feminists had learned from these organizations how to think radically about their self-worth and importance, and applied these lessons in the relationships they had with each other.

Businesses

Feminist activists have established a range of feminist businesses, including women's bookstores, feminist credit unions, feminist presses, feminist mail-order catalogs, feminist restaurants, and feminist record labels. These businesses flourished as part of the second and third waves of feminism in the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s. In West Berlin sixteen projects emerged within three years (1974–76) all without state funding (except the women's shelter). Many of those new concepts the social economy picked up later, some are still run autonomously today.Music and popular culture

Second-wave feminists viewed popular culture as sexist, and created pop culture of their own to counteract this. "One project of second wave feminism was to create 'positive' images of women, to act as a counterweight to the dominant images circulating in popular culture and to raise women's consciousness of their oppressions.""I Am Woman"

Australian artistHelen Reddy

Helen Maxine Reddy (25 October 194129 September 2020) was an Australian-American singer, actress, television host, and activist. Born in Melbourne to a show business family, Reddy started her career as an entertainer at age four. She sang on ra ...

's 1972 song "I Am Woman

"I Am Woman" is a song written by Australian musicians Helen Reddy and Ray Burton (musician), Ray Burton. Performed by Reddy, the first recording of "I Am Woman" appeared on her debut album ''I Don't Know How to Love Him (album), I Don't Know H ...

" played a large role in popular culture and became a feminist anthem; Reddy came to be known as a "feminist poster girl" or a "feminist icon". Reddy told interviewers that the song was a "song of pride about being a woman". A few weeks after "I Am Woman" entered the charts, radio stations refused to play it. Some music critics and radio stations believed the song represented "all that is silly in the Women's Lib Movement". Helen Reddy then began performing the song on numerous television variety shows. As the song gained popularity, women began calling radio stations and requesting to hear "I Am Woman" played. The song re-entered the charts and reached number one in December 1972.

"The Anthem and the Angst", Sunday Magazine, Melbourne Sunday Herald Sun/Sydney Sunday Telegraph, June 15, 2003, Page 16.

Betty Friedan, "It Changed My Life" (1976), pp. 257

"Reddy to sing for the rent", Sunday Telegraph (Sydney), November 13, 1981

"Helen still believes, it's just that she has to pay the rent too", by John Burns of the Daily Express, reprinted in ''Melbourne Herald'', December 16, 1981

"I Am Woman" also became a protest song that women sang at feminist rallies and protests.

Olivia Records

In 1973, a group of five feminists created the first women's owned-and-operated record label, calledOlivia Records

Olivia Records is a record label founded in 1973 in Washington D.C. which centers female musicians. Its founders included prominent lesbian figures Ginny Berson, Meg Christian, Judy Dlugacz, Jennifer Woodul, Kate Winter and five others. Olivia ...

. They created the record label because they were frustrated that major labels were slow to add female artists to their rosters. One of Olivia's founders, Judy Dlugacz, said that, "It was a chance to create opportunities for women artists within an industry which at that time had few." Initially, they had a budget of $4,000, and relied on donations to keep Olivia Records alive. With these donations, Olivia Records created their first LP, an album of feminist songs entitled ''I Know You Know.'' The record label originally relied on volunteers and feminist bookstores to distribute their records, but after a few years their records began to be sold in mainstream record stores.

Olivia Records was so successful that the company relocated from Washington, D.C., to Los Angeles in 1975. Olivia Records released several records and albums, and their popularity grew. As their popularity grew, an alternative, specialized music industry grew around it. This type of music was initially referred to as "lesbian music" but came to be known as "women's music". However, although Olivia Records was initially meant for women, in the 1980s it tried to move away from that stereotype and encouraged men to listen to their music as well.

Women's music

Women's music consisted of female musicians who combined music with politics to express feminist ideals. Cities throughout the United States began to hold Women's Music Festivals, all consisting of female artists singing their own songs about personal experiences. The first Women's Music Festival was held in 1974 at the University of Illinois. In 1979, the Michigan Womyn's Music Festival attracted 10,000 women from across America. These festivals encouraged already-famous female singers, such asLaura Nyro

Laura Nyro ( ; born Laura Nigro; October 18, 1947 – April 8, 1997) was an American songwriter and singer. She achieved critical acclaim with her own recordings, particularly the albums ''Eli and the Thirteenth Confession'' (1968) and ''Ne ...

and Ellen McIllwaine, to begin writing and producing their own songs instead of going through a major record label. Many women began performing hard rock music, a traditionally male-dominated genre. One of the most successful examples included the sisters Ann and Nancy Wilson, who formed the famous hard rock band Heart

The heart is a muscular Organ (biology), organ found in humans and other animals. This organ pumps blood through the blood vessels. The heart and blood vessels together make the circulatory system. The pumped blood carries oxygen and nutrie ...

.

Film

German-speaking Europe

TheDeutsche Film- und Fernsehakademie Berlin

The Deutsche Film- und Fernsehakademie Berlin (DFFB, German Film and Television Academy Berlin) is a film school in Berlin, Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It lies between the Ba ...

gave women a chance in film in Germany: from 1968 on one third of the students were female. Some of them - pioneers of the women's movement - produced feminist feature films: Helke Sander in 1971 produced ''Eine Prämie für Irene'' Reward for Irene and Cristina Perincioli (although she was Swiss not German) in 1971 produced ''Für Frauen – 1.Kap'' or Women – 1st Chapter

In West Germany Helma Sanders-Brahms

Helma Sanders-Brahms (20 November 1940 – 27 May 2014) was a German film director, screenwriter and producer.

Biography

Helma Sanders was born on 20 November 1940 in Emden, Germany. She attended a school for acting in Hannover from 1960 to 1 ...

and Claudia von Alemann produced feminist documentaries from 1970 on.

In 1973, Claudia von Alemann and Helke Sander organized the 1. Internationale Frauen-Filmseminar in Berlin.

In 1974, Helke Sander founded the journal '' Frauen und Film'' – a first feminist film journal, which she edited until 1981.

In the 1970s in West Germany, women directors produced a whole series of Frauenfilm - films focusing on women's personal emancipation. In the 1980s the Goethe Institute

The Goethe-Institut (; GI, ''Goethe Institute'') is a Nonprofit organization, nonprofit German culture, cultural organization operational worldwide with more than 150 cultural centres, promoting the study of the German language abroad and en ...

brought a collection of German women's films to every corner of the world.

"...here the term 'feminist filmmaking' does function to point to a filmmaking practice defining itself outside the masculine mirror. German feminism is one of the most active women's movements in Europe. It has gained access to television; engendered a spectrum of journals, a publishing house and a summer women's university in Berlin; inspired a whole group of filmmakers; ..." writes Marc Silberman in ''Jump Cut

A jump cut is a cut (transition), cut in film editing that breaks a single continuous sequential shot of a subject into two parts, with a piece of footage removed to create the effect of jumping forward in time. Camera positioning on the subjec ...

''. But most of the women filmmakers did not see themselves as feminists, except Helke Sander and Cristina Perincioli. Perincioli stated in an interview: "Fight first ... before making beautiful art". There, she explains how she develops and shoots the film together with the women concerned: saleswomen, battered wives - and why she prefers to work with an all female team. Camera women were still so rare in the 1970 that she had to find them in Denmark and France. Working with an all women film crew Perincioli encouraged women to learn these then male dominated professions.

= Association of women filmworkers of Germany

= In 1979, German women filmworkers formed the Association of women filmworkers which was active for a few years. In 2014, a new attempt with Proquote Film (then as Proquote Regie) turned out to be successful and effective. A study by the University of Rostock shows that 42% of the graduates of film schools are female, but only 22% of the German feature films are staged by a woman director and are usually financially worse equipped. Similarly, women are disadvantaged in the other male-dominated film trades, where men even without education are preferred to the female graduates. The initiative points out that the introduction of a quota system in Sweden has brought the proportion of women in key positions in film production around the same as the population share. As a result, the Swedish initiative calls also for a parity of film funding bodies and the implementation of a gradual women's quota for the allocation of film and television directing jobs in order to achieve a gender-equitable distribution. This should reflect the plurality of a modern society, because diversity can not be guaranteed if more than 80% of all films are produced by men. ProQuote Film is the third initiative with which women with a high share in their industry are fighting for more female executives and financial resources (see Pro Quote Medien (2012) and Quote Medizin).United States

In the US, both the creation and subjects of motion pictures began to reflect second-wave feminist ideals, leading to the development of feminist film theory. In the late 1970s and early 1980s, female filmmakers that were involved in part of the new wave of feminist film includedJoan Micklin Silver

Joan Micklin Silver (May 24, 1935 – December 31, 2020) was an American director of films and plays. Born in Omaha, Silver moved to New York City in 1967 where she began writing and directing films. She is best known for her debut film Hester S ...

('' Between the Lines''), Claudia Weill ('' Girlfriends''), Stephanie Rothman

Stephanie Rothman (born November 9, 1936) is an American film director, producer, and screenwriter, known for her low-budget independent exploitation films made in the 1960s and 1970s, especially ''The Student Nurses'' (1970) and ''Terminal Isla ...

, and Susan Seidelman

Susan Seidelman (; born December 11, 1952) is an American film director, producer, and writer. She is known for mixing comedy with drama and blending genres in her feature-film work. She is also notable for her art direction and pop-cultural refe ...

('' Smithereens'', ''Desperately Seeking Susan

''Desperately Seeking Susan'' is a 1985 American comedy-drama film directed by Susan Seidelman and starring Rosanna Arquette, Aidan Quinn and Madonna. Set in New York City, the plot involves the interaction between two women – a bored housew ...

''). Other notable films that explored feminist subject matters that were made at this time include the 1968 film '' Rosemary's Baby'' and the 1971 film adaptation of Lois Gould's 1970 novel '' Such Good Friends''.

The 2014 documentary ''She's Beautiful When She's Angry

''She's Beautiful When She's Angry'' is a 2014 American documentary film about some of the women involved in the second-wave feminism, second-wave feminist movement in the United States. It was directed by Mary Dore and co-produced by Nancy Ken ...

'' was the first documentary film

A documentary film (often described simply as a documentary) is a nonfiction Film, motion picture intended to "document reality, primarily for instruction, education or maintaining a Recorded history, historical record". The American author and ...

to cover feminism's second wave.

Art

Art during second wave feminism also flourished. Known as theFeminist art movement

The feminist art movement refers to the efforts and accomplishments of feminists internationally to produce feminist art, art that reflects women's lives and experiences, as well as to change the foundation for the production and perception of co ...

, the works and artists during the movement fought to give themselves representation in a field dominated by white men. Their works came in all different mediums and aimed to end oppression, challenge gender norms, and highlight the fraught art industry rooted in white patriarchy. Linda Nochlin

Linda Nochlin (''née'' Weinberg; January 30, 1931 – October 29, 2017) was an American art historian, Lila Acheson Wallace Professor Emerita of Modern Art at New York University Institute of Fine Arts, and writer. As a prominent feminist art hi ...

's essay " Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?" (1971) has become one of the most influential works that came from the movement and questions gender stereotypes for women in the art field as well as the definition of art as a whole.

Social changes

Use of birth control

Finding a need to talk about the advantage of theFood and Drug Administration

The United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA or US FDA) is a List of United States federal agencies, federal agency of the United States Department of Health and Human Services, Department of Health and Human Services. The FDA is respo ...

passing their approval for the use of birth control

Birth control, also known as contraception, anticonception, and fertility control, is the use of methods or devices to prevent pregnancy. Birth control has been used since ancient times, but effective and safe methods of birth control only be ...

in 1960, liberal feminists took action in creating panels and workshops with the goal to promote conscious raising among sexually active women. These workshops also brought attention to issues such as venereal diseases and safe abortion. Radical feminists also joined this push to raise awareness among sexually active women. While supporting the "Free Love Movement" of the late 1960s and early 1970s, young women on college campuses distributed pamphlets on birth control, sexual diseases, abortion, and cohabitation.

While white women were concerned with obtaining birth control for all, women of color were at risk of sterilization because of these same medical and social advances: "Native American, African American, and Latina groups documented and publicized sterilization abuses in their communities in the 1960s and 70s, showing that women had been sterilized without their knowledge or consent... In the 1970s, a group of women... founded the Committee to End Sterilization Abuse (CESA) to stop this racist population control policy begun by the federal government in the 1940s – a policy that had resulted in the sterilization of over one-third of all women of child-bearing age in Puerto Rico." The use of forced sterilization disproportionately affected women of color and women from lower socioeconomic statuses. Sterilization was often done under the ideology of eugenics

Eugenics is a set of largely discredited beliefs and practices that aim to improve the genetic quality of a human population. Historically, eugenicists have attempted to alter the frequency of various human phenotypes by inhibiting the fer ...

. Thirty states within the United States authorized legal sterilizations under eugenic sciences.

Domestic violence and sexual harassment

The second-wave feminist movement also took a strong stance against physical violence and sexual assault in both the home and the workplace. In 1968, NOW successfully lobbied theEqual Employment Opportunity Commission

The U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) is a federal agency that was established via the Civil Rights Act of 1964 to administer and enforce civil rights laws against workplace discrimination. The EEOC investigates discrimination ...

to pass an amendment to Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 () is a landmark civil rights and United States labor law, labor law in the United States that outlaws discrimination based on Race (human categorization), race, Person of color, color, religion, sex, and nationa ...

, which prevented discrimination based on sex in the workplace. This attention to women's rights in the workplace also prompted the EEOC to add sexual harassment to its "Guidelines on Discrimination", therefore giving women the right to report their bosses and coworkers for acts of sexual assault.