Seawater Foundation on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Seawater, or sea water, is

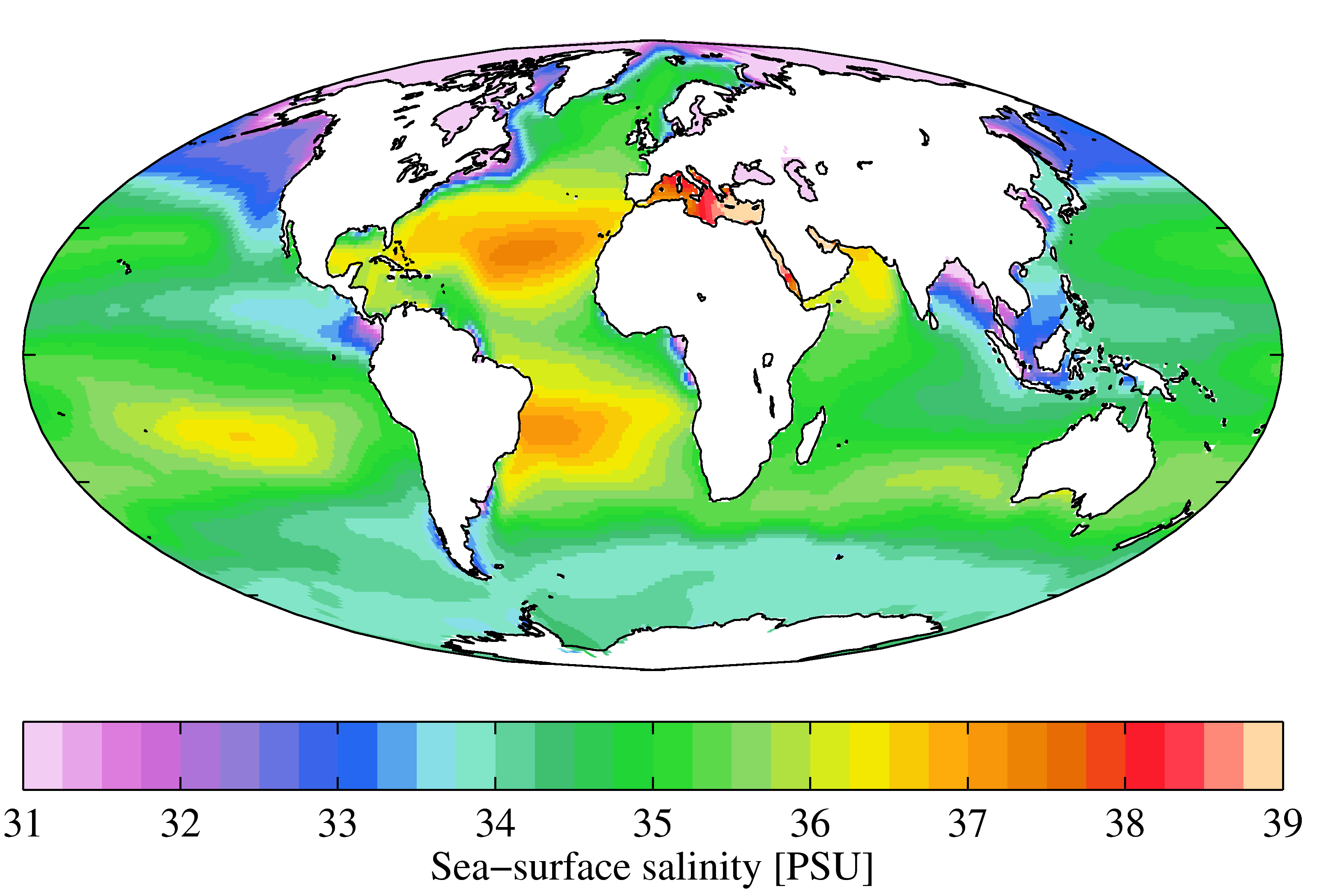

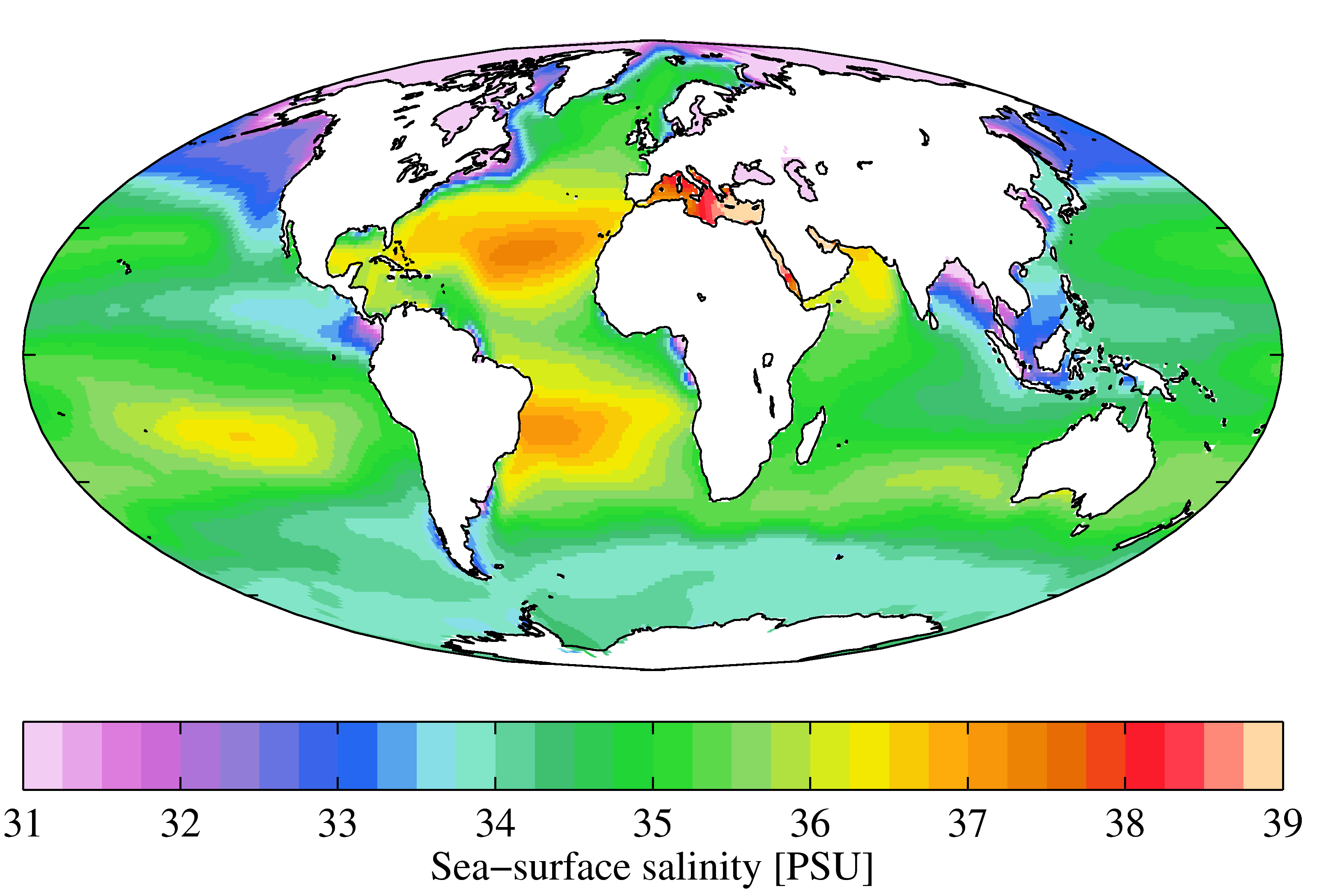

Although the vast majority of seawater has a salinity of between 31 and 38 g/kg, that is 3.1–3.8%, seawater is not uniformly saline throughout the world. Where mixing occurs with freshwater runoff from river mouths, near melting glaciers or vast amounts of precipitation (e.g.

Although the vast majority of seawater has a salinity of between 31 and 38 g/kg, that is 3.1–3.8%, seawater is not uniformly saline throughout the world. Where mixing occurs with freshwater runoff from river mouths, near melting glaciers or vast amounts of precipitation (e.g.

Technical Summary

. I

Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change

[Masson-Delmotte, V., P. Zhai, A. Pirani, S.L. Connors, C. Péan, S. Berger, N. Caud, Y. Chen, L. Goldfarb, M.I. Gomis, M. Huang, K. Leitzell, E. Lonnoy, J.B.R. Matthews, T.K. Maycock, T. Waterfield, O. Yelekçi, R. Yu, and B. Zhou (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA, pp. 33−144. Since then, it has been decreasing due to a human-caused process called

water

Water is an inorganic compound with the chemical formula . It is a transparent, tasteless, odorless, and Color of water, nearly colorless chemical substance. It is the main constituent of Earth's hydrosphere and the fluids of all known liv ...

from a sea

A sea is a large body of salt water. There are particular seas and the sea. The sea commonly refers to the ocean, the interconnected body of seawaters that spans most of Earth. Particular seas are either marginal seas, second-order section ...

or ocean

The ocean is the body of salt water that covers approximately 70.8% of Earth. The ocean is conventionally divided into large bodies of water, which are also referred to as ''oceans'' (the Pacific, Atlantic, Indian Ocean, Indian, Southern Ocean ...

. On average, seawater in the world's oceans has a salinity

Salinity () is the saltiness or amount of salt (chemistry), salt dissolved in a body of water, called saline water (see also soil salinity). It is usually measured in g/L or g/kg (grams of salt per liter/kilogram of water; the latter is dimensio ...

of about 3.5% (35 g/L, 35 ppt, 600 mM). This means that every kilogram (roughly one liter by volume) of seawater has approximately of dissolved salts (predominantly sodium

Sodium is a chemical element; it has Symbol (chemistry), symbol Na (from Neo-Latin ) and atomic number 11. It is a soft, silvery-white, highly reactive metal. Sodium is an alkali metal, being in group 1 element, group 1 of the peri ...

() and chloride

The term chloride refers to a compound or molecule that contains either a chlorine anion (), which is a negatively charged chlorine atom, or a non-charged chlorine atom covalently bonded to the rest of the molecule by a single bond (). The pr ...

() ions

An ion () is an atom or molecule with a net electrical charge. The charge of an electron is considered to be negative by convention and this charge is equal and opposite to the charge of a proton, which is considered to be positive by convent ...

). The average density at the surface is 1.025 kg/L. Seawater is denser than both fresh water

Fresh water or freshwater is any naturally occurring liquid or frozen water containing low concentrations of dissolved salt (chemistry), salts and other total dissolved solids. The term excludes seawater and brackish water, but it does include ...

and pure water (density 1.0 kg/L at ) because the dissolved salts increase the mass by a larger proportion than the volume. The freezing point of seawater decreases as salt concentration increases. At typical salinity, it freezes

Freezing is a phase transition in which a liquid turns into a solid when its temperature is lowered below its freezing point.

For most substances, the melting and freezing points are the same temperature; however, certain substances possess dif ...

at about . The coldest seawater still in the liquid state ever recorded was found in 2010, in a stream under an Antarctic

The Antarctic (, ; commonly ) is the polar regions of Earth, polar region of Earth that surrounds the South Pole, lying within the Antarctic Circle. It is antipodes, diametrically opposite of the Arctic region around the North Pole.

The Antar ...

glacier

A glacier (; or ) is a persistent body of dense ice, a form of rock, that is constantly moving downhill under its own weight. A glacier forms where the accumulation of snow exceeds its ablation over many years, often centuries. It acquires ...

: the measured temperature was .

Seawater pH is typically limited to a range between 7.5 and 8.4. However, there is no universally accepted reference pH-scale for seawater and the difference between measurements based on different reference scales may be up to 0.14 units.Stumm, W, Morgan, J. J. (1981) ''Aquatic Chemistry, An Introduction Emphasizing Chemical Equilibria in Natural Waters''. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 414–416. .

Properties

Salinity

Although the vast majority of seawater has a salinity of between 31 and 38 g/kg, that is 3.1–3.8%, seawater is not uniformly saline throughout the world. Where mixing occurs with freshwater runoff from river mouths, near melting glaciers or vast amounts of precipitation (e.g.

Although the vast majority of seawater has a salinity of between 31 and 38 g/kg, that is 3.1–3.8%, seawater is not uniformly saline throughout the world. Where mixing occurs with freshwater runoff from river mouths, near melting glaciers or vast amounts of precipitation (e.g. monsoon

A monsoon () is traditionally a seasonal reversing wind accompanied by corresponding changes in precipitation but is now used to describe seasonal changes in Atmosphere of Earth, atmospheric circulation and precipitation associated with annu ...

), seawater can be substantially less saline. The most saline open sea is the Red Sea

The Red Sea is a sea inlet of the Indian Ocean, lying between Africa and Asia. Its connection to the ocean is in the south, through the Bab-el-Mandeb Strait and the Gulf of Aden. To its north lie the Sinai Peninsula, the Gulf of Aqaba, and th ...

, where high rates of evaporation

Evaporation is a type of vaporization that occurs on the Interface (chemistry), surface of a liquid as it changes into the gas phase. A high concentration of the evaporating substance in the surrounding gas significantly slows down evapora ...

, low precipitation

In meteorology, precipitation is any product of the condensation of atmospheric water vapor that falls from clouds due to gravitational pull. The main forms of precipitation include drizzle, rain, rain and snow mixed ("sleet" in Commonwe ...

and low river run-off, and confined circulation result in unusually salty water. The salinity in isolated bodies of water can be considerably greater still about ten times higher in the case of the Dead Sea

The Dead Sea (; or ; ), also known by #Names, other names, is a landlocked salt lake bordered by Jordan to the east, the Israeli-occupied West Bank to the west and Israel to the southwest. It lies in the endorheic basin of the Jordan Rift Valle ...

. Historically, several salinity scales were used to approximate the absolute salinity of seawater. A popular scale was the "Practical Salinity Scale" where salinity was measured in "practical salinity units (PSU)". The current standard for salinity is the "Reference Salinity" scale with the salinity expressed in units of "g/kg".

Density

Thedensity

Density (volumetric mass density or specific mass) is the ratio of a substance's mass to its volume. The symbol most often used for density is ''ρ'' (the lower case Greek letter rho), although the Latin letter ''D'' (or ''d'') can also be u ...

of surface seawater ranges from about 1020 to 1029 kg/m3, depending on the temperature and salinity. At a temperature of 25 °C, the salinity of 35 g/kg and 1 atm pressure, the density of seawater is 1023.6 kg/m3. Deep in the ocean, under high pressure, seawater can reach a density of 1050 kg/m3 or higher. The density of seawater also changes with salinity. Brines generated by seawater desalination plants can have salinities up to 120 g/kg. The density of typical seawater brine of 120 g/kg salinity at 25 °C and atmospheric pressure is 1088 kg/m3.

pH value

The pH value at the surface of oceans in pre-industrial time (before 1850) was around 8.2.Arias, P.A., N. Bellouin, E. Coppola, R.G. Jones, G. Krinner, J. Marotzke, V. Naik, M.D. Palmer, G.-K. Plattner, J. Rogelj, M. Rojas, J. Sillmann, T. Storelvmo, P.W. Thorne, B. Trewin, K. Achuta Rao, B. Adhikary, R.P. Allan, K. Armour, G. Bala, R. Barimalala, S. Berger, J.G. Canadell, C. Cassou, A. Cherchi, W. Collins, W.D. Collins, S.L. Connors, S. Corti, F. Cruz, F.J. Dentener, C. Dereczynski, A. Di Luca, A. Diongue Niang, F.J. Doblas-Reyes, A. Dosio, H. Douville, F. Engelbrecht, V. Eyring, E. Fischer, P. Forster, B. Fox-Kemper, J.S. Fuglestvedt, J.C. Fyfe, et al., 2021Technical Summary

. I

Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change

[Masson-Delmotte, V., P. Zhai, A. Pirani, S.L. Connors, C. Péan, S. Berger, N. Caud, Y. Chen, L. Goldfarb, M.I. Gomis, M. Huang, K. Leitzell, E. Lonnoy, J.B.R. Matthews, T.K. Maycock, T. Waterfield, O. Yelekçi, R. Yu, and B. Zhou (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA, pp. 33−144. Since then, it has been decreasing due to a human-caused process called

ocean acidification

Ocean acidification is the ongoing decrease in the pH of the Earth's ocean. Between 1950 and 2020, the average pH of the ocean surface fell from approximately 8.15 to 8.05. Carbon dioxide emissions from human activities are the primary cause of ...

that is related to carbon dioxide emissions

Greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions from human activities intensify the greenhouse effect. This contributes to climate change. Carbon dioxide (), from burning fossil fuels such as coal, oil, and natural gas, is the main cause of climate change. The ...

: Between 1950 and 2020, the average pH of the ocean surface fell from approximately 8.15 to 8.05.

The pH value of seawater is naturally as low as 7.8 in deep ocean waters as a result of degradation of organic matter in these waters. It can be as high as 8.4 in surface waters in areas of high biological productivity

In ecology, the term productivity refers to the rate of generation of biomass in an ecosystem, usually expressed in units of mass per volume (unit surface) per unit of time, such as grams per square metre per day (g m−2 d−1). The unit of mass ...

.

Measurement of pH is complicated by the chemical properties

A chemical property is any of a material property, material's properties that becomes evident during, or after, a chemical reaction; that is, any attribute that can be established only by changing a substance's chemical substance, chemical identit ...

of seawater, and several distinct pH scales exist in chemical oceanography

Marine chemistry, also known as ocean chemistry or chemical oceanography, is the study of the chemical composition and processes of the world’s oceans, including the interactions between seawater, the atmosphere, the seafloor, and marine organ ...

.Zeebe, R. E. and Wolf-Gladrow, D. (2001) ''CO2 in seawater: equilibrium, kinetics, isotopes'', Elsevier Science B.V., Amsterdam, Netherlands There is no universally accepted reference pH-scale for seawater and the difference between measurements based on different reference scales may be up to 0.14 units.

Chemical composition

Seawater contains more dissolvedion

An ion () is an atom or molecule with a net electrical charge. The charge of an electron is considered to be negative by convention and this charge is equal and opposite to the charge of a proton, which is considered to be positive by convent ...

s than all types of freshwater. However, the ratios of solutes differ dramatically. For instance, although seawater contains about 2.8 times more bicarbonate

In inorganic chemistry, bicarbonate (IUPAC-recommended nomenclature: hydrogencarbonate) is an intermediate form in the deprotonation of carbonic acid. It is a polyatomic anion with the chemical formula .

Bicarbonate serves a crucial bioche ...

than river water, the percentage

In mathematics, a percentage () is a number or ratio expressed as a fraction (mathematics), fraction of 100. It is often Denotation, denoted using the ''percent sign'' (%), although the abbreviations ''pct.'', ''pct'', and sometimes ''pc'' are ...

of bicarbonate in seawater as a ratio of ''all'' dissolved ion

An ion () is an atom or molecule with a net electrical charge. The charge of an electron is considered to be negative by convention and this charge is equal and opposite to the charge of a proton, which is considered to be positive by convent ...

s is far lower than in river water. Bicarbonate ions constitute 48% of river water solutes but only 0.14% for seawater. Differences like these are due to the varying residence time

The residence time of a fluid parcel is the total time that the parcel has spent inside a control volume (e.g.: a chemical reactor, a lake, a human body). The residence time of a set of parcels is quantified in terms of the frequency distribu ...

s of seawater solutes; sodium

Sodium is a chemical element; it has Symbol (chemistry), symbol Na (from Neo-Latin ) and atomic number 11. It is a soft, silvery-white, highly reactive metal. Sodium is an alkali metal, being in group 1 element, group 1 of the peri ...

and chloride

The term chloride refers to a compound or molecule that contains either a chlorine anion (), which is a negatively charged chlorine atom, or a non-charged chlorine atom covalently bonded to the rest of the molecule by a single bond (). The pr ...

have very long residence times, while calcium

Calcium is a chemical element; it has symbol Ca and atomic number 20. As an alkaline earth metal, calcium is a reactive metal that forms a dark oxide-nitride layer when exposed to air. Its physical and chemical properties are most similar to it ...

(vital for carbonate

A carbonate is a salt of carbonic acid, (), characterized by the presence of the carbonate ion, a polyatomic ion with the formula . The word "carbonate" may also refer to a carbonate ester, an organic compound containing the carbonate group ...

formation) tends to precipitate much more quickly. The most abundant dissolved ions in seawater are sodium, chloride, magnesium

Magnesium is a chemical element; it has Symbol (chemistry), symbol Mg and atomic number 12. It is a shiny gray metal having a low density, low melting point and high chemical reactivity. Like the other alkaline earth metals (group 2 ...

, sulfate

The sulfate or sulphate ion is a polyatomic anion with the empirical formula . Salts, acid derivatives, and peroxides of sulfate are widely used in industry. Sulfates occur widely in everyday life. Sulfates are salts of sulfuric acid and many ...

and calcium. Its osmolarity

Osmotic concentration, formerly known as osmolarity, is the measure of solute concentration, defined as the number of osmoles (Osm) of solute per litre (L) of solution (osmol/L or Osm/L). The osmolarity of a solution is usually expressed as Osm/ ...

is about 1000 mOsm/L.

Small amounts of other substances are found, including amino acids

Amino acids are organic compounds that contain both amino and carboxylic acid functional groups. Although over 500 amino acids exist in nature, by far the most important are the Proteinogenic amino acid, 22 α-amino acids incorporated into p ...

at concentrations of up to 2 micrograms of nitrogen atoms per liter, which are thought to have played a key role in the origin of life

Abiogenesis is the natural process by which life arises from abiotic component, non-living matter, such as simple organic compounds. The prevailing scientific hypothesis is that the transition from non-living to organism, living entities on ...

.

Microbial components

Research in 1957 by theScripps Institution of Oceanography

Scripps Institution of Oceanography (SIO) is the center for oceanography and Earth science at the University of California, San Diego. Its main campus is located in La Jolla, with additional facilities in Point Loma.

Founded in 1903 and incorpo ...

sampled water in both pelagic

The pelagic zone consists of the water column of the open ocean and can be further divided into regions by depth. The word ''pelagic'' is derived . The pelagic zone can be thought of as an imaginary cylinder or water column between the sur ...

and neritic

The neritic zone (or sublittoral zone) is the relatively shallow part of the ocean above the drop-off of the continental shelf, approximately in depth.

From the point of view of marine biology it forms a relatively stable and well-illuminated ...

locations in the Pacific Ocean. Direct microscopic counts and cultures were used, the direct counts in some cases showing up to 10 000 times that obtained from cultures. These differences were attributed to the occurrence of bacteria in aggregates, selective effects of the culture media, and the presence of inactive cells. A marked reduction in bacterial culture numbers was noted below the thermocline

A thermocline (also known as the thermal layer or the metalimnion in lakes) is

a distinct layer based on temperature within a large body of fluid (e.g. water, as in an ocean or lake; or air, e.g. an atmosphere) with a high gradient of distinct te ...

, but not by direct microscopic observation. Large numbers of spirilli-like forms were seen by microscope but not under cultivation. The disparity in numbers obtained by the two methods is well known in this and other fields. In the 1990s, improved techniques of detection and identification of microbes by probing just small snippets of DNA

Deoxyribonucleic acid (; DNA) is a polymer composed of two polynucleotide chains that coil around each other to form a double helix. The polymer carries genetic instructions for the development, functioning, growth and reproduction of al ...

, enabled researchers taking part in the Census of Marine Life

The Census of Marine Life was a scientific initiative involving a global network of researchers in more than 80 nations, engaged to assess and explain the diversity, distribution, and abundance of life in the oceans. The census cost US$650 milli ...

to identify thousands of previously unknown microbes usually present only in small numbers. This revealed a far greater diversity than previously suspected, so that a litre of seawater may hold more than 20,000 species. Mitchell Sogin

Mitchell Sogin is an American microbiologist. He is a distinguished senior scientist at the Marine Biological Laboratory in Woods Hole, Massachusetts. His research investigates the evolution, diversity,and distribution of single-celled organisms. ...

from the Marine Biological Laboratory

The Marine Biological Laboratory (MBL) is an international center for research and education in biological and environmental science. Founded in Woods Hole, Massachusetts, in 1888, the MBL is a private, nonprofit institution that was independent ...

feels that "the number of different kinds of bacteria in the oceans could eclipse five to 10 million."

Bacteria are found at all depths in the water column

The (oceanic) water column is a concept used in oceanography to describe the physical (temperature, salinity, light penetration) and chemical ( pH, dissolved oxygen, nutrient salts) characteristics of seawater at different depths for a defined ...

, as well as in the sediments, some being aerobic, others anaerobic. Most are free-swimming, but some exist as symbionts

Symbiosis (Ancient Greek : living with, companionship < : together; and ''bíōsis'': living) is any type of a close and long-term

"Cooking with seawater – is it the best way to season food?"

''Guardian'', 21 April 2015. The water is marketed as , "the perfect salt", containing less sodium with what is considered a superior taste. A restaurant run by

Another practice that is being considered closely is the process of

Another practice that is being considered closely is the process of

Technical Papers in Marine Science 44, Algorithms for computation of fundamental properties of seawater, ioc-unesco.org, UNESCO 1983

Tables

Tables and software for thermophysical properties of seawater

MIT * {{Authority control Aquatic ecology Chemical oceanography Liquid water Physical oceanography Oceanographical terminology

Cyanobacteria

Cyanobacteria ( ) are a group of autotrophic gram-negative bacteria that can obtain biological energy via oxygenic photosynthesis. The name "cyanobacteria" () refers to their bluish green (cyan) color, which forms the basis of cyanobacteri ...

played an important role in the evolution of ocean processes, enabling the development of stromatolites

Stromatolites ( ) or stromatoliths () are layered sedimentary formations ( microbialite) that are created mainly by photosynthetic microorganisms such as cyanobacteria, sulfate-reducing bacteria, and Pseudomonadota (formerly proteobacteria) ...

and oxygen in the atmosphere.

Some bacteria interact with diatoms

A diatom (Neo-Latin ''diatoma'') is any member of a large group comprising several Genus, genera of algae, specifically microalgae, found in the oceans, waterways and soils of the world. Living diatoms make up a significant portion of Earth's B ...

, and form a critical link in the cycling of silicon in the ocean. One anaerobic species, ''Thiomargarita namibiensis

''Thiomargarita namibiensis'' is a gram-negative, Facultative anaerobic organism, facultative anaerobic, coccus, coccoid bacterium found in South Africa's ocean sediments of the continental shelf of Namibia. The genus name ''Thiomargarita'' mean ...

'', plays an important part in the breakdown of hydrogen sulfide

Hydrogen sulfide is a chemical compound with the formula . It is a colorless chalcogen-hydride gas, and is toxic, corrosive, and flammable. Trace amounts in ambient atmosphere have a characteristic foul odor of rotten eggs. Swedish chemist ...

eruptions from diatomaceous sediments off the Namibian coast, and generated by high rates of phytoplankton

Phytoplankton () are the autotrophic (self-feeding) components of the plankton community and a key part of ocean and freshwater Aquatic ecosystem, ecosystems. The name comes from the Greek language, Greek words (), meaning 'plant', and (), mea ...

growth in the Benguela Current

The Benguela Current is the broad, northward flowing ocean current that forms the eastern portion of the South Atlantic Ocean gyre. The current extends from roughly Cape Point in the south, to the position of the Angola-Benguela Front in the no ...

upwelling zone, eventually falling to the seafloor.

Bacteria-like Archaea

Archaea ( ) is a Domain (biology), domain of organisms. Traditionally, Archaea only included its Prokaryote, prokaryotic members, but this has since been found to be paraphyletic, as eukaryotes are known to have evolved from archaea. Even thou ...

surprised marine microbiologists by their survival and thriving in extreme environments, such as the hydrothermal vents

Hydrothermal vents are fissures on the seabed from which geothermally heated water discharges. They are commonly found near volcanically active places, areas where tectonic plates are moving apart at mid-ocean ridges, ocean basins, and hots ...

on the ocean floor. Alkalotolerant marine bacteria

Marine prokaryotes are marine bacteria and marine archaea. They are defined by their habitat as prokaryotes that live in marine environments, that is, in the saltwater of seas or oceans or the brackish water of coastal estuaries. All cellu ...

such as ''Pseudomonas

''Pseudomonas'' is a genus of Gram-negative bacteria belonging to the family Pseudomonadaceae in the class Gammaproteobacteria. The 348 members of the genus demonstrate a great deal of metabolic diversity and consequently are able to colonize a ...

'' and ''Vibrio

''Vibrio'' is a genus of Gram-negative bacteria, which have a characteristic curved-rod (comma) shape, several species of which can cause foodborne infection or soft-tissue infection called Vibriosis. Infection is commonly associated with eati ...

'' spp. survive in a pH range of 7.3 to 10.6, while some species will grow only at pH 10 to 10.6. Archaea also exist in pelagic waters and may constitute as much as half the ocean's biomass

Biomass is a term used in several contexts: in the context of ecology it means living organisms, and in the context of bioenergy it means matter from recently living (but now dead) organisms. In the latter context, there are variations in how ...

, clearly playing an important part in oceanic processes. In 2000 sediments from the ocean floor revealed a species of Archaea that breaks down methane

Methane ( , ) is a chemical compound with the chemical formula (one carbon atom bonded to four hydrogen atoms). It is a group-14 hydride, the simplest alkane, and the main constituent of natural gas. The abundance of methane on Earth makes ...

, an important greenhouse

A greenhouse is a structure that is designed to regulate the temperature and humidity of the environment inside. There are different types of greenhouses, but they all have large areas covered with transparent materials that let sunlight pass an ...

gas and a major contributor to atmospheric warming. Some bacteria break down the rocks of the sea floor, influencing seawater chemistry. Oil spills, and runoff containing human sewage and chemical pollutants have a marked effect on microbial life in the vicinity, as well as harbouring pathogens and toxins affecting all forms of marine life

Marine life, sea life or ocean life is the collective ecological communities that encompass all aquatic animals, aquatic plant, plants, algae, marine fungi, fungi, marine protists, protists, single-celled marine microorganisms, microorganisms ...

. The protist dinoflagellates

The Dinoflagellates (), also called Dinophytes, are a monophyletic group of single-celled eukaryotes constituting the phylum Dinoflagellata and are usually considered protists. Dinoflagellates are mostly marine plankton, but they are also commo ...

may at certain times undergo population explosions called blooms or red tide

A harmful algal bloom (HAB), or excessive algae growth, sometimes called a red tide in marine environments, is an algal bloom that causes negative impacts to other organisms by production of natural algae-produced toxins, water deoxygenation, ...

s, often after human-caused pollution. The process may produce metabolites

In biochemistry, a metabolite is an intermediate or end product of metabolism.

The term is usually used for small molecules. Metabolites have various functions, including fuel, structure, signaling, stimulatory and inhibitory effects on enzymes, c ...

known as biotoxins, which move along the ocean food chain, tainting higher-order animal consumers.

''Pandoravirus salinus

''Pandoravirus salinus'' is a large virus of genus ''Pandoravirus'', found in the marine sediment layer of the Tunquen River in Chile, and is one of the largest viruses identified, along with '' Pandoravirus dulcis''. It is 2.5 million nucleoba ...

'', a species of very large virus, with a genome much larger than that of any other virus species, was discovered in 2013. Like the other very large viruses ''Mimivirus

''Mimivirus'' is a genus of giant viruses, in the family ''Mimiviridae''. It is believed that Amoeba serve as their natural hosts. It also refers to a group of phylogenetically related large viruses.

In colloquial speech, APMV is more commonly ...

'' and ''Megavirus

''Megavirus'' is a viral genus, phylogenetically related to '' Acanthamoeba polyphaga mimivirus'' (APMV). In colloquial speech, ''Megavirus chilense'' is more commonly referred to as just "Megavirus". Until the discovery of pandoraviruses in 2 ...

'', ''Pandoravirus'' infects amoebas, but its genome, containing 1.9 to 2.5 megabases of DNA, is twice as large as that of ''Megavirus'', and it differs greatly from the other large viruses in appearance and in genome structure.

In 2013 researchers from Aberdeen University

The University of Aberdeen (abbreviated ''Aberd.'' in post-nominals; ) is a public research university in Aberdeen, Scotland. It was founded in 1495 when William Elphinstone, Bishop of Aberdeen and Chancellor of Scotland, petitioned Pope Al ...

announced that they were starting a hunt for undiscovered chemicals in organisms that have evolved in deep sea trenches, hoping to find "the next generation" of antibiotics, anticipating an "antibiotic apocalypse" with a dearth of new infection-fighting drugs. The EU-funded research will start in the Atacama Trench and then move on to search trenches off New Zealand and Antarctica.

The ocean has a long history of human waste disposal on the assumption that its vast size makes it capable of absorbing and diluting all noxious material.

While this may be true on a small scale, the large amounts of sewage routinely dumped has damaged many coastal ecosystems, and rendered them life-threatening. Pathogenic viruses and bacteria occur in such waters, such as ''Escherichia coli

''Escherichia coli'' ( )Wells, J. C. (2000) Longman Pronunciation Dictionary. Harlow ngland Pearson Education Ltd. is a gram-negative, facultative anaerobic, rod-shaped, coliform bacterium of the genus '' Escherichia'' that is commonly fo ...

'', ''Vibrio cholerae

''Vibrio cholerae'' is a species of Gram-negative bacteria, Gram-negative, Facultative anaerobic organism, facultative anaerobe and Vibrio, comma-shaped bacteria. The bacteria naturally live in Brackish water, brackish or saltwater where they att ...

'' the cause of cholera

Cholera () is an infection of the small intestine by some Strain (biology), strains of the Bacteria, bacterium ''Vibrio cholerae''. Symptoms may range from none, to mild, to severe. The classic symptom is large amounts of watery diarrhea last ...

, hepatitis A

Hepatitis A is an infectious liver disease caused by Hepatitis A virus (HAV); it is a type of viral hepatitis. Many cases have few or no symptoms, especially in the young. The time between infection and symptoms, in those who develop them, is ...

, hepatitis E

Hepatitis E is inflammation of the liver caused by infection with the hepatitis E virus (HEV); it is a type of viral hepatitis. Hepatitis E has mainly a fecal-oral transmission route that is similar to hepatitis A, although the viruses are u ...

and polio

Poliomyelitis ( ), commonly shortened to polio, is an infectious disease caused by the poliovirus. Approximately 75% of cases are asymptomatic; mild symptoms which can occur include sore throat and fever; in a proportion of cases more severe ...

, along with protozoans causing giardiasis

Giardiasis is a parasitic disease caused by the protist enteropathogen ''Giardia duodenalis'' (also known as ''G. lamblia'' and ''G. intestinalis''), especially common in children and travellers. Infected individuals experience steatorrhea, a typ ...

and cryptosporidiosis

Cryptosporidiosis, sometimes informally called crypto, is a parasitic disease caused by ''Cryptosporidium'', a genus of protozoan parasites in the phylum Apicomplexa. It affects the ileum, distal small intestine and can affect the respiratory tr ...

. These pathogens are routinely present in the ballast water of large vessels, and are widely spread when the ballast is discharged.

Other parameters

Thespeed of sound

The speed of sound is the distance travelled per unit of time by a sound wave as it propagates through an elasticity (solid mechanics), elastic medium. More simply, the speed of sound is how fast vibrations travel. At , the speed of sound in a ...

in seawater is about 1,500 m/s (whereas the speed of sound is usually around 330 m/s in air at roughly 101.3 kPa pressure, 1 atmosphere), and varies with water temperature, salinity, and pressure. The thermal conductivity

The thermal conductivity of a material is a measure of its ability to heat conduction, conduct heat. It is commonly denoted by k, \lambda, or \kappa and is measured in W·m−1·K−1.

Heat transfer occurs at a lower rate in materials of low ...

of seawater is 0.6 W/mK at 25 °C and a salinity of 35 g/kg.

The thermal conductivity decreases with increasing salinity and increases with increasing temperature.

Origin and history

The water in the sea was thought to come from the Earth'svolcano

A volcano is commonly defined as a vent or fissure in the crust of a planetary-mass object, such as Earth, that allows hot lava, volcanic ash, and gases to escape from a magma chamber below the surface.

On Earth, volcanoes are most oft ...

es, starting 4 billion years ago, released by degassing from molten rock. More recent work suggests much of the Earth's water may come from comet

A comet is an icy, small Solar System body that warms and begins to release gases when passing close to the Sun, a process called outgassing. This produces an extended, gravitationally unbound atmosphere or Coma (cometary), coma surrounding ...

s.

Scientific theories

A scientific theory is an explanation of an aspect of the natural world that can be or that has been repeatedly tested and has corroborating evidence in accordance with the scientific method, using accepted protocols of observation, measureme ...

behind the origins of sea salt started with Sir Edmond Halley

Edmond (or Edmund) Halley (; – ) was an English astronomer, mathematician and physicist. He was the second Astronomer Royal in Britain, succeeding John Flamsteed in 1720.

From an observatory he constructed on Saint Helena in 1676–77, Hal ...

in 1715, who proposed that salt and other minerals were carried into the sea by rivers after rainfall washed it out of the ground. Upon reaching the ocean, these salts concentrated as more salt arrived over time (see Hydrologic cycle

The water cycle (or hydrologic cycle or hydrological cycle) is a biogeochemical cycle that involves the continuous movement of water on, above and below the surface of the Earth across different reservoirs. The mass of water on Earth remains fai ...

). Halley noted that most lakes that do not have ocean outlets (such as the Dead Sea

The Dead Sea (; or ; ), also known by #Names, other names, is a landlocked salt lake bordered by Jordan to the east, the Israeli-occupied West Bank to the west and Israel to the southwest. It lies in the endorheic basin of the Jordan Rift Valle ...

and the Caspian Sea

The Caspian Sea is the world's largest inland body of water, described as the List of lakes by area, world's largest lake and usually referred to as a full-fledged sea. An endorheic basin, it lies between Europe and Asia: east of the Caucasus, ...

, see endorheic basin

An endorheic basin ( ; also endoreic basin and endorreic basin) is a drainage basin that normally retains water and allows no outflow to other external bodies of water (e.g. rivers and oceans); instead, the water drainage flows into permanent ...

), have high salt content. Halley termed this process "continental weathering".

Halley's theory was partly correct. In addition, sodium leached out of the ocean floor when the ocean formed. The presence of salt's other dominant ion, chloride, results from outgassing

Outgassing (sometimes called offgassing, particularly when in reference to indoor air quality) is the release of a gas that was dissolved, trapped, frozen, or absorbed in some material. Outgassing can include sublimation and evaporation (whic ...

of chloride (as hydrochloric acid

Hydrochloric acid, also known as muriatic acid or spirits of salt, is an aqueous solution of hydrogen chloride (HCl). It is a colorless solution with a distinctive pungency, pungent smell. It is classified as a acid strength, strong acid. It is ...

) with other gases from Earth's interior via volcano

A volcano is commonly defined as a vent or fissure in the crust of a planetary-mass object, such as Earth, that allows hot lava, volcanic ash, and gases to escape from a magma chamber below the surface.

On Earth, volcanoes are most oft ...

s and hydrothermal vent

Hydrothermal vents are fissures on the seabed from which geothermally heated water discharges. They are commonly found near volcanically active places, areas where tectonic plates are moving apart at mid-ocean ridges, ocean basins, and hot ...

s. The sodium and chloride ions subsequently became the most abundant constituents of sea salt.

Ocean salinity has been stable for billions of years, most likely as a consequence of a chemical/tectonic

Tectonics ( via Latin ) are the processes that result in the structure and properties of the Earth's crust and its evolution through time. The field of ''planetary tectonics'' extends the concept to other planets and moons.

These processes ...

system which removes as much salt as is deposited; for instance, sodium and chloride sinks include evaporite

An evaporite () is a water- soluble sedimentary mineral deposit that results from concentration and crystallization by evaporation from an aqueous solution. There are two types of evaporite deposits: marine, which can also be described as oce ...

deposits, pore-water burial, and reactions with seafloor basalt

Basalt (; ) is an aphanite, aphanitic (fine-grained) extrusive igneous rock formed from the rapid cooling of low-viscosity lava rich in magnesium and iron (mafic lava) exposed at or very near the planetary surface, surface of a terrestrial ...

s.

Human impacts

Climate change

Present-day climate change includes both global warming—the ongoing increase in Global surface temperature, global average temperature—and its wider effects on Earth's climate system. Climate variability and change, Climate change in ...

, rising levels of carbon dioxide in Earth's atmosphere

In Earth's atmosphere, carbon dioxide is a trace gas that plays an integral part in the greenhouse effect, carbon cycle, photosynthesis and oceanic carbon cycle. It is one of three main greenhouse gases in the atmosphere of Earth. The conce ...

, excess nutrients, and pollution in many forms are altering global oceanic geochemistry

Geochemistry is the science that uses the tools and principles of chemistry to explain the mechanisms behind major geological systems such as the Earth's crust and its oceans. The realm of geochemistry extends beyond the Earth, encompassing the e ...

. Rates of change for some aspects greatly exceed those in the historical and recent geological record. Major trends include an increasing acidity

An acid is a molecule or ion capable of either donating a proton (i.e. hydrogen cation, H+), known as a Brønsted–Lowry acid, or forming a covalent bond with an electron pair, known as a Lewis acid.

The first category of acids are the ...

, reduced subsurface oxygen in both near-shore and pelagic waters, rising coastal nitrogen levels, and widespread increases in mercury and persistent organic pollutants. Most of these perturbations are tied either directly or indirectly to human fossil fuel combustion, fertilizer, and industrial activity. Concentrations are projected to grow in coming decades, with negative impacts on ocean biota and other marine resources.

One of the most striking features of this is ocean acidification

Ocean acidification is the ongoing decrease in the pH of the Earth's ocean. Between 1950 and 2020, the average pH of the ocean surface fell from approximately 8.15 to 8.05. Carbon dioxide emissions from human activities are the primary cause of ...

, resulting from increased uptake of the oceans related to higher atmospheric concentration of and higher temperatures, because it severely affects coral reef

A coral reef is an underwater ecosystem characterized by reef-building corals. Reefs are formed of colonies of coral polyps held together by calcium carbonate. Most coral reefs are built from stony corals, whose polyps cluster in group ...

s, mollusk

Mollusca is a phylum of protostomic invertebrate animals, whose members are known as molluscs or mollusks (). Around 76,000 extant species of molluscs are recognized, making it the second-largest animal phylum after Arthropoda. The ...

s, echinoderm

An echinoderm () is any animal of the phylum Echinodermata (), which includes starfish, brittle stars, sea urchins, sand dollars and sea cucumbers, as well as the sessile sea lilies or "stone lilies". While bilaterally symmetrical as ...

s and crustacean

Crustaceans (from Latin meaning: "those with shells" or "crusted ones") are invertebrate animals that constitute one group of arthropods that are traditionally a part of the subphylum Crustacea (), a large, diverse group of mainly aquatic arthrop ...

s (see coral bleaching

Coral bleaching is the process when corals become white due to loss of Symbiosis, symbiotic algae and Photosynthesis, photosynthetic pigments. This loss of pigment can be caused by various stressors, such as changes in water temperature, light, ...

).

Seawater is a means of transportation throughout the world. Every day plenty of ships cross the ocean to deliver goods to various locations around the world. Seawater is a tool for countries to efficiently participate in international commercial trade and transportation, but each ship exhausts emissions that can harm marine life, air quality of coastal areas. Seawater transportation is one of the fastest growing human generated greenhouse gas emissions. The emissions released from ships pose significant risks to human health in nearing areas as the oil

An oil is any nonpolar chemical substance that is composed primarily of hydrocarbons and is hydrophobic (does not mix with water) and lipophilic (mixes with other oils). Oils are usually flammable and surface active. Most oils are unsaturate ...

and gas

Gas is a state of matter that has neither a fixed volume nor a fixed shape and is a compressible fluid. A ''pure gas'' is made up of individual atoms (e.g. a noble gas like neon) or molecules of either a single type of atom ( elements such as ...

released from the operation of merchant ships decreases the air quality and causes more pollution

Pollution is the introduction of contaminants into the natural environment that cause harm. Pollution can take the form of any substance (solid, liquid, or gas) or energy (such as radioactivity, heat, sound, or light). Pollutants, the component ...

both in the seawater and surrounding areas.

Another human use of seawater that has been considered is the use of seawater for agricultural

Agriculture encompasses crop and livestock production, aquaculture, and forestry for food and non-food products. Agriculture was a key factor in the rise of sedentary human civilization, whereby farming of domesticated species created f ...

purposes. In areas with higher regions of sand dunes

A dune is a landform composed of wind- or water-driven sand. It typically takes the form of a mound, ridge, or hill. An area with dunes is called a dune system or a dune complex. A large dune complex is called a dune field, while broad, flat ...

, such as Israel

Israel, officially the State of Israel, is a country in West Asia. It Borders of Israel, shares borders with Lebanon to the north, Syria to the north-east, Jordan to the east, Egypt to the south-west, and the Mediterranean Sea to the west. Isr ...

, the use of seawater for irrigation

Irrigation (also referred to as watering of plants) is the practice of applying controlled amounts of water to land to help grow crops, landscape plants, and lawns. Irrigation has been a key aspect of agriculture for over 5,000 years and has bee ...

of plants would eliminate substantial costs associated with fresh water when it is not easily accessible. Although it is not typical to use salt water

Saline water (more commonly known as salt water) is water that contains a high concentration of dissolved salts (mainly sodium chloride). On the United States Geological Survey (USGS) salinity scale, saline water is saltier than brackish wate ...

as a means to grow plants as the salt gathers and ruins the surrounding soil, it has been proven to be successful in sand and gravel soils. Large-scale desalination of seawater is another factor that would contribute to the success of agriculture farming in dry, desert

A desert is a landscape where little precipitation occurs and, consequently, living conditions create unique biomes and ecosystems. The lack of vegetation exposes the unprotected surface of the ground to denudation. About one-third of the la ...

environments. One of the most successful plants in salt water agriculture is the halophyte

A halophyte is a salt-tolerant plant that grows in soil or waters of high salinity, coming into contact with saline water through its roots or by salt spray, such as in saline semi-deserts, mangrove swamps, marshes and sloughs, and seashores. ...

. The halophyte is a salt tolerant plant whose cells are resistant to the typically detrimental effects of salt in soil. The endodermis

The endodermis is the innermost layer of cortex in land plants. It is a cylinder of compact living cells, the radial walls of which are impregnated with hydrophobic substances ( Casparian strip) to restrict apoplastic flow of water to the inside ...

forces a higher level of salt filtration throughout the plant as it allows for the circulation of more water through the cells. The cultivation of halophytes irrigated with salt water were used to grow animal feed

Animal feed is food given to domestic animals, especially livestock, in the course of animal husbandry. There are two basic types: fodder and forage. Used alone, the word ''feed'' more often refers to fodder. Animal feed is an important input ...

for livestock

Livestock are the Domestication, domesticated animals that are raised in an Agriculture, agricultural setting to provide labour and produce diversified products for consumption such as meat, Egg as food, eggs, milk, fur, leather, and wool. The t ...

; however, the animals that were fed these plants consumed more water than those that did not. Although agriculture from use of saltwater is still not recognized and used on a large scale, initial research has shown that there could be an opportunity to provide more crops in regions where agricultural farming is not usually feasible.

Human consumption

Accidentally consuming small quantities of clean seawater is not harmful, especially if the seawater is taken along with a larger quantity of fresh water. However, drinking seawater to maintain hydration is counterproductive; more water must be excreted to eliminate the salt (viaurine

Urine is a liquid by-product of metabolism in humans and many other animals. In placental mammals, urine flows from the Kidney (vertebrates), kidneys through the ureters to the urinary bladder and exits the urethra through the penile meatus (mal ...

) than the amount of water obtained from the seawater itself. In normal circumstances, it would be considered ill-advised to consume large amounts of unfiltered seawater.

The renal system

The human urinary system, also known as the urinary tract or renal system, consists of the kidneys, ureters, bladder, and the urethra. The purpose of the urinary system is to eliminate waste from the body, regulate blood volume and blood pressu ...

actively regulates the levels of sodium and chloride in the blood within a very narrow range around 9 g/L (0.9% by mass).

In most open waters concentrations vary somewhat around typical values of about 3.5%, far higher than the body can tolerate and most beyond what the kidney can process. A point frequently overlooked in claims that the kidney can excrete NaCl in Baltic

Baltic may refer to:

Peoples and languages

*Baltic languages, a subfamily of Indo-European languages, including Lithuanian, Latvian and extinct Old Prussian

*Balts (or Baltic peoples), ethnic groups speaking the Baltic languages and/or originatin ...

concentrations of 2% (in arguments to the contrary) is that the gut cannot absorb water at such concentrations, so that there is no benefit in drinking such water. The salinity of Baltic surface water, however, is never 2%. It is 0.9% or less, and thus never higher than that of bodily fluids. Drinking seawater temporarily increases blood's NaCl concentration. This signals the kidney

In humans, the kidneys are two reddish-brown bean-shaped blood-filtering organ (anatomy), organs that are a multilobar, multipapillary form of mammalian kidneys, usually without signs of external lobulation. They are located on the left and rig ...

to excrete sodium, but seawater's sodium concentration is above the kidney's maximum concentrating ability. Eventually the blood's sodium concentration rises to toxic levels, removing water from cells and interfering with nerve

A nerve is an enclosed, cable-like bundle of nerve fibers (called axons). Nerves have historically been considered the basic units of the peripheral nervous system. A nerve provides a common pathway for the Electrochemistry, electrochemical nerv ...

conduction, ultimately producing fatal seizure

A seizure is a sudden, brief disruption of brain activity caused by abnormal, excessive, or synchronous neuronal firing. Depending on the regions of the brain involved, seizures can lead to changes in movement, sensation, behavior, awareness, o ...

and cardiac arrhythmia

Arrhythmias, also known as cardiac arrhythmias, are irregularities in the heartbeat, including when it is too fast or too slow. Essentially, this is anything but normal sinus rhythm. A resting heart rate that is too fast – above 100 beat ...

.

Survival manuals

Survival or survivorship, the act of surviving, is the propensity of something to continue existing, particularly when this is done despite conditions that might kill or destroy it. The concept can be applied to humans and other living things ...

consistently advise against drinking seawater. A summary of 163 life raft

A lifeboat or liferaft is a small, rigid or inflatable boat carried for emergency evacuation in the event of a disaster aboard a ship. Lifeboat drills are required by law on larger commercial ships. Rafts ( liferafts) are also used. In the m ...

voyages estimated the risk of death at 39% for those who drank seawater, compared to 3% for those who did not. The effect of seawater intake on rats confirmed the negative effects of drinking seawater when dehydrated.

The temptation to drink seawater was greatest for sailors who had expended their supply of fresh water and were unable to capture enough rainwater for drinking. This frustration was described famously by a line from Samuel Taylor Coleridge

Samuel Taylor Coleridge ( ; 21 October 177225 July 1834) was an English poet, literary critic, philosopher, and theologian who was a founder of the Romantic Movement in England and a member of the Lake Poets with his friend William Wordsworth ...

's ''The Rime of the Ancient Mariner

''The Rime of the Ancient Mariner'' (originally ''The Rime of the Ancyent Marinere''), written by English poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge in 1797–98 and published in 1798 in the first edition of '' Lyrical Ballads'', is a poem that recounts th ...

'':

Although humans cannot survive on seawater in place of normal drinking water, some people claim that up to two cups a day, mixed with fresh water in a 2:3 ratio, produces no ill effect. The French physician Alain Bombard

Alain Bombard (; Paris, 27 October 1924 – Paris, 19 July 2005) was a French biologist, physician and politician famous for sailing in a small boat across the Atlantic Ocean without provision. He theorized that a human being could very well su ...

survived an ocean crossing in a small Zodiak rubber boat using mainly raw fish meat, which contains about 40% water (like most living tissues), as well as small amounts of seawater and other provisions harvested from the ocean. His findings were challenged, but an alternative explanation could not be given. In his 1948 book ''The Kon-Tiki Expedition

''The Kon-Tiki Expedition: By Raft Across the South Seas'' () is a 1948 book by the Norwegian writer Thor Heyerdahl. It recounts Heyerdahl's experiences with the ''Kon-Tiki'' expedition, where he travelled across the Pacific Ocean

The P ...

'', Thor Heyerdahl

Thor Heyerdahl KStJ (; 6 October 1914 – 18 April 2002) was a Norwegian adventurer and Ethnography, ethnographer with a background in biology with specialization in zoology, botany and geography.

Heyerdahl is notable for his Kon-Tiki expediti ...

reported drinking seawater mixed with fresh in a 2:3 ratio during the 1947 expedition. A few years later, another adventurer, William Willis, claimed to have drunk two cups of seawater and one cup of fresh per day for 70 days without ill effect when he lost part of his water supply.

During the 18th century, Richard Russell advocated the medical use of this practice in the UK, and René Quinton

René Joseph Quinton (1866–1925) was a French biologist, aviation pioneer and decorated World War I soldier.

In his biology career, he developed a treatment based on seawater injections that he called ''sérum de Quinton'', which has been aban ...

expanded the advocation of this practice to other countries, notably France, in the 20th century. Currently, it is widely practiced in Nicaragua and other countries, supposedly taking advantage of the latest medical discoveries.

Purification

Like any other type of raw or contaminated water, seawater can be evaporated or filtered to eliminate salt, germs, and other contaminants that would otherwise prevent it from being consideredpotable

Drinking water or potable water is water that is safe for ingestion, either when drunk directly in liquid form or consumed indirectly through food preparation. It is often (but not always) supplied through taps, in which case it is also calle ...

. Most oceangoing vessels desalinate

Desalination is a process that removes mineral components from saline water. More generally, desalination is the removal of salts and minerals from a substance. One example is soil desalination. This is important for agriculture. It is possible ...

potable water from seawater using processes such as vacuum distillation

Vacuum distillation or distillation under reduced pressure is a type of distillation performed under reduced pressure, which allows the purification of compounds not readily distilled at ambient pressures or simply to save time or energy. This te ...

or multi-stage flash distillation

Multi-stage flash distillation (MSF) is a water desalination process that distills sea water by flashing a portion of the water into steam in multiple stages of what are essentially countercurrent heat exchangers. Current MSF facilities may h ...

in an evaporator

An evaporator is a type of heat exchanger device that facilitates evaporation by utilizing conductive and convective heat transfer, which provides the necessary thermal energy for phase transition from liquid to vapour. Within evaporators, a ci ...

, or, more recently, reverse osmosis

Reverse osmosis (RO) is a water purification process that uses a partially permeable membrane, semi-permeable membrane to separate water molecules from other substances. RO applies pressure to overcome osmotic pressure that favors even distribu ...

. These energy-intensive processes were not usually available during the Age of Sail

The Age of Sail is a period in European history that lasted at the latest from the mid-16th (or mid-15th) to the mid-19th centuries, in which the dominance of sailing ships in global trade and warfare culminated, particularly marked by the int ...

. Larger sailing warships with large crews, such as Nelson

Nelson may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* ''Nelson'' (1918 film), a historical film directed by Maurice Elvey

* ''Nelson'' (1926 film), a historical film directed by Walter Summers

* ''Nelson'' (opera), an opera by Lennox Berkeley to a lib ...

's , were fitted with distilling apparatus in their galleys

A galley is a type of ship optimised for propulsion by oars. Galleys were historically used for warfare, trade, and piracy mostly in the seas surrounding Europe. It developed in the Mediterranean world during antiquity and continued to exist ...

.

The natural sea salt obtained by evaporating seawater can also be collected and sold as table salt

In common usage, salt is a mineral composed primarily of sodium chloride (NaCl). When used in food, especially in granulated form, it is more formally called table salt. In the form of a natural crystalline mineral, salt is also known as ro ...

, typically sold separately owing to its unique mineral make-up compared to rock salt

Halite ( ), commonly known as rock salt, is a type of salt, the mineral (natural) form of sodium chloride ( Na Cl). Halite forms isometric crystals. The mineral is typically colorless or white, but may also be light blue, dark blue, purple, pi ...

or other sources.

A number of regional cuisines across the world traditionally incorporate seawater directly as an ingredient, cooking other ingredients in a diluted solution of filtered seawater as a substitute for conventional dry seasoning

Seasoning is the process of supplementing food via herbs, spices, and/or salts, intended to enhance a particular flavour.

General meaning

Seasonings include herbs and spices, which are themselves frequently referred to as "seasonings". Salt may ...

s. Proponents include world-renowned chefs Ferran Adrià

Fernando Adrià Acosta (; born 14 May 1962) is a Spanish chef. He was the head chef of the El Bulli restaurant in Roses, Girona, Roses on the Costa Brava and is considered one of the best chefs in the world. He has often collaborated with his b ...

and Quique Dacosta, whose home country of Spain has six different companies sourcing filtered seawater for culinary use.Baker, Trevor"Cooking with seawater – is it the best way to season food?"

''Guardian'', 21 April 2015. The water is marketed as , "the perfect salt", containing less sodium with what is considered a superior taste. A restaurant run by

Joaquín Baeza

Joaquín or Joaquin is a male given name, the Spanish version of Joachim.

Given name

* Joaquín (footballer, born 1956) (Joaquín Alonso González), Spanish football midfielder

* Joaquín (footballer, born 1981) (Joaquín Sánchez Rodríguez), ...

sources as much as 60,000 litres a month from supplier Mediterranea

Animals such as fish, whales, sea turtle

Sea turtles (superfamily Chelonioidea), sometimes called marine turtles, are reptiles of the order Testudines and of the suborder Cryptodira. The seven existing species of sea turtles are the flatback, green, hawksbill, leatherback, loggerh ...

s, and seabird

Seabirds (also known as marine birds) are birds that are adaptation, adapted to life within the marine ecosystem, marine environment. While seabirds vary greatly in lifestyle, behaviour and physiology, they often exhibit striking convergent ...

s, such as penguins and albatross

Albatrosses, of the biological family Diomedeidae, are large seabirds related to the procellariids, storm petrels, and diving petrels in the order Procellariiformes (the tubenoses). They range widely in the Southern Ocean and the North Paci ...

es, have adapted to living in a high-saline habitat. For example, sea turtles and saltwater crocodiles remove excess salt from their bodies through their tear ducts

The nasolacrimal duct (also called the tear duct) carries tears from the lacrimal sac of the eye into the nasal cavity. The duct begins in the eye socket between the maxillary and lacrimal bones, from where it passes downwards and backwards. The o ...

.

Mineral extraction

Minerals have been extracted from seawater since ancient times. Currently the four most concentrated metals – Na, Mg, Ca and K – are commercially extracted from seawater. During 2015 in the US 63% ofmagnesium

Magnesium is a chemical element; it has Symbol (chemistry), symbol Mg and atomic number 12. It is a shiny gray metal having a low density, low melting point and high chemical reactivity. Like the other alkaline earth metals (group 2 ...

production came from seawater and brines. Bromine

Bromine is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol, symbol Br and atomic number 35. It is a volatile red-brown liquid at room temperature that evaporates readily to form a similarly coloured vapour. Its properties are intermediate between th ...

is also produced from seawater in China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. With population of China, a population exceeding 1.4 billion, it is the list of countries by population (United Nations), second-most populous country after ...

and Japan. Lithium

Lithium (from , , ) is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol, symbol Li and atomic number 3. It is a soft, silvery-white alkali metal. Under standard temperature and pressure, standard conditions, it is the least dense metal and the ...

extraction from seawater was tried in the 1970s, but the tests were soon abandoned. The idea of extracting uranium

Uranium is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol, symbol U and atomic number 92. It is a silvery-grey metal in the actinide series of the periodic table. A uranium atom has 92 protons and 92 electrons, of which 6 are valence electrons. Ura ...

from seawater has been considered at least from the 1960s, but only a few grams of uranium were extracted in Japan

Japan is an island country in East Asia. Located in the Pacific Ocean off the northeast coast of the Asia, Asian mainland, it is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan and extends from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north to the East China Sea ...

in the late 1990s. The main issue is not one of technological feasibility but that current prices on the uranium market

The uranium market, like all commodity markets, has a history of volatility, moving with the standard forces of supply and demand as well as geopolitical pressures. It has also evolved particularities of its own in response to the unique nature ...

for uranium from other sources are about three to five times lower than the lowest price achieved by seawater extraction. Similar issues hamper the use of reprocessed uranium

Reprocessed uranium (RepU) is the uranium recovered from nuclear reprocessing, as done commercially in France, the UK and Japan and by nuclear weapons states' military plutonium production programs. This uranium makes up the bulk of the material ...

and are often brought forth against nuclear reprocessing

Nuclear reprocessing is the chemical separation of fission products and actinides from spent nuclear fuel. Originally, reprocessing was used solely to extract plutonium for producing nuclear weapons. With commercialization of nuclear power, the ...

and the manufacturing of MOX fuel

Mixed oxide fuel (MOX fuel) is nuclear fuel that contains more than one oxide of fissile material, usually consisting of plutonium blended with natural uranium, reprocessed uranium, or depleted uranium. MOX fuel is an alternative to the low-enr ...

as economically unviable.

The future of mineral and element extractions

In order for seawater mineral and element extractions to take place while taking close consideration of sustainable practices, it is necessary for monitored management systems to be put in place. This requires management of ocean areas and their conditions,environmental planning

Environmental planning is the process of facilitating decision making to carry out land development with the consideration given to the natural environment, social, political, economic and governance factors and provides a holistic framework to a ...

, structured guidelines to ensure that extractions are controlled, regular assessments of the condition of the sea post-extraction, and constant monitoring. The use of technology, such as underwater drones, can facilitate sustainable extractions. The use of low-carbon infrastructure would also allow for more sustainable extraction processes while reducing the carbon footprint from mineral extractions.

Another practice that is being considered closely is the process of

Another practice that is being considered closely is the process of desalination

Desalination is a process that removes mineral components from saline water. More generally, desalination is the removal of salts and minerals from a substance. One example is Soil salinity control, soil desalination. This is important for agric ...

in order to achieve a more sustainable water supply from seawater. Although desalination also comes with environmental concerns, such as costs and resources, researchers are working closely to determine more sustainable practices, such as creating more productive water plants that can deal with larger water supplies in areas where these plans weren't always available. Although seawater extractions can benefit society greatly, it is crucial to consider the environmental impact and to ensure that all extractions are conducted in a way that acknowledges and considers the associated risks to the sustainability of seawater ecosystems.

Standard

ASTM International

ASTM International, formerly known as American Society for Testing and Materials, is a standards organization that develops and publishes voluntary consensus technical international standards for a wide range of materials, products, systems and s ...

has an international standard for artificial seawater

Artificial seawater (abbreviated ASW) is a mixture of dissolved mineral salts (and sometimes vitamins) that simulates seawater. Artificial seawater is primarily used in marine biology and in marine and reef aquaria, and allows the easy preparati ...

: ASTM D1141-98 (Original Standard ASTM D1141-52). It is used in many research testing labs as a reproducible solution for seawater such as tests on corrosion, oil contamination, and detergency evaluation.

Ecosystems

The minerals found in seawater can also play an important role in the ocean and its ecosystem's food cycle. For example, theSouthern Ocean

The Southern Ocean, also known as the Antarctic Ocean, comprises the southernmost waters of the world ocean, generally taken to be south of 60th parallel south, 60° S latitude and encircling Antarctica. With a size of , it is the seco ...

contributes greatly to the environmental carbon cycle

The carbon cycle is a part of the biogeochemical cycle where carbon is exchanged among the biosphere, pedosphere, geosphere, hydrosphere, and atmosphere of Earth. Other major biogeochemical cycles include the nitrogen cycle and the water cycl ...

. Given that this body of water does not contain high levels of iron

Iron is a chemical element; it has symbol Fe () and atomic number 26. It is a metal that belongs to the first transition series and group 8 of the periodic table. It is, by mass, the most common element on Earth, forming much of Earth's o ...

, the deficiency impacts the marine life living in its waters. As a result, this ocean is not able to produce as much phytoplankton

Phytoplankton () are the autotrophic (self-feeding) components of the plankton community and a key part of ocean and freshwater Aquatic ecosystem, ecosystems. The name comes from the Greek language, Greek words (), meaning 'plant', and (), mea ...

which hinders the first source of the marine food chain. One of the main types of phytoplankton are diatoms

A diatom (Neo-Latin ''diatoma'') is any member of a large group comprising several Genus, genera of algae, specifically microalgae, found in the oceans, waterways and soils of the world. Living diatoms make up a significant portion of Earth's B ...

which is the primary food source of Antarctic krill

Antarctic krill (''Euphausia superba'') is a species of krill found in the Antarctica, Antarctic waters of the Southern Ocean. It is a small, swimming crustacean that lives in large schools, called swarms, sometimes reaching densities of 10,000� ...

. As the cycle continues, various larger sea animals feed off of Antarctic krill, but since there is a shortage of iron from the initial phytoplankton/diatoms, then these larger species also lack iron. The larger sea animals include Baleen Whales

Baleen whales (), also known as whalebone whales, are marine mammals of the order (biology), parvorder Mysticeti in the infraorder Cetacea (whales, dolphins and porpoises), which use baleen plates (or "whalebone") in their mouths to sieve plankt ...

such as the Blue Whale

The blue whale (''Balaenoptera musculus'') is a marine mammal and a baleen whale. Reaching a maximum confirmed length of and weighing up to , it is the largest animal known ever to have existed. The blue whale's long and slender body can ...

and Fin Whale

The fin whale (''Balaenoptera physalus''), also known as the finback whale or common rorqual, is a species of baleen whale and the second-longest cetacean after the blue whale. The biggest individual reportedly measured in length, wi ...

. These whales not only rely on iron for a balance of minerals within their diet, but it also impacts the amount of iron that is regenerated back into the ocean. The whale's excretions also contain the absorbed iron which would allow iron to be reinserted into the ocean’s ecosystem. Overall, one mineral deficiency such as iron in the Southern Ocean can spark a significant chain of disturbances within the marine ecosystems which demonstrates the important role that seawater plays in the food chain

A food chain is a linear network of links in a food web, often starting with an autotroph (such as grass or algae), also called a producer, and typically ending at an apex predator (such as grizzly bears or killer whales), detritivore (such as ...

.

Upon further analysis of the dynamic relationship between diatoms, krill, and baleen whales, fecal samples of baleen whales were examined in Antarctic seawater. The findings included that iron concentrations were 10 million times higher than those found in Antarctic seawater, and krill was found consistently throughout their feces which is an indicator that krill is in whale diets. Antarctic krill had an average iron level of 174.3mg/kg dry weight, but the iron in the krill varied from 12 to 174 mg/kg dry weight. The average iron concentration of the muscular tissue of blue whales and fin whales was 173 mg/kg dry weight, which demonstrates that the large marine mammals are important to marine ecosystems such as they are to the Southern Ocean. In fact, to have more whales in the ocean could heighten the amount of iron in seawater through their excretions which would promote a better ecosystem.

Krill and baleen whales act as large iron reservoirs in seawater in the Southern Ocean. Krill can retain up to 24% of iron found on surface waters within its range.The process of krill feeding on diatoms releases iron into seawater, highlighting them as an important part of the ocean's iron cycle

The iron cycle (Fe) is the biogeochemical cycle of iron through the atmosphere, hydrosphere, biosphere and lithosphere. While Fe is highly abundant in the Earth's crust, it is less common in oxygenated surface waters. Iron is a key micronutrient ...

. The advantageous relationship between krill and baleen whales increases the amount of iron that can be recycled and stored in seawater. A positive feedback loop

Positive feedback (exacerbating feedback, self-reinforcing feedback) is a process that occurs in a feedback loop where the outcome of a process reinforces the inciting process to build momentum. As such, these forces can exacerbate the effects ...

is created, increasing the overall productivity of marine life in the Southern Ocean.

Organisms of all sizes play a significant role in the balance of marine ecosystems with both the largest and smallest inhabitants contributing equally to recycling nutrients in seawater. Prioritizing the recovery of whale populations because they boost the overall productivity in marine ecosystems as well as increasing iron levels in seawater would allow for a balanced and productive system for the ocean. However, a more in depth study is required to understand the benefits of whale feces as a fertilizer and to provide further insight in iron recycling in the Southern Ocean. Projects on the management of ecosystems and conservation are vital for advancing knowledge of marine ecology.

Environmental impact and sustainability

Like any mineral extraction practices, there are environmental advantages and disadvantages.Cobalt

Cobalt is a chemical element; it has Symbol (chemistry), symbol Co and atomic number 27. As with nickel, cobalt is found in the Earth's crust only in a chemically combined form, save for small deposits found in alloys of natural meteoric iron. ...

and Lithium

Lithium (from , , ) is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol, symbol Li and atomic number 3. It is a soft, silvery-white alkali metal. Under standard temperature and pressure, standard conditions, it is the least dense metal and the ...

are two key metals that can be used for aiding with more environmentally friendly technologies above ground, such as powering batteries that energize electric vehicles

An electric vehicle (EV) is a motor vehicle whose propulsion is powered fully or mostly by electricity. EVs encompass a wide range of transportation modes, including road vehicle, road and rail vehicles, electric boats and Submersible, submer ...

or creating wind power

Wind power is the use of wind energy to generate useful work. Historically, wind power was used by sails, windmills and windpumps, but today it is mostly used to generate electricity. This article deals only with wind power for electricity ge ...

. An environmentally friendly approach to mining that allows for more sustainability would be to extract these metals from the seafloor. Lithium mining

Lithium (from , , ) is a chemical element; it has symbol Li and atomic number 3. It is a soft, silvery-white alkali metal. Under standard conditions, it is the least dense metal and the least dense solid element. Like all alkali metals, ...

from the seafloor at mass quantities could provide a substantial amount of renewable metals to promote more environmentally friendly practices in society to reduce humans' carbon footprint

A carbon footprint (or greenhouse gas footprint) is a calculated value or index that makes it possible to compare the total amount of greenhouse gases that an activity, product, company or country Greenhouse gas emissions, adds to the atmospher ...

. Lithium mining from the seafloor could be successful, but its success would be dependent on more productive recycling

Recycling is the process of converting waste materials into new materials and objects. This concept often includes the recovery of energy from waste materials. The recyclability of a material depends on its ability to reacquire the propert ...

practices above ground.

There are also risks that come with extracting from the seafloor. Many biodiverse species have long lifespans on the seafloor, which means that their reproduction takes more time. Similarly to fish harvesting from the seafloor, the extraction of minerals in large amounts, too quickly, without proper protocols, can result in a disruption of the underwater ecosystems. Contrarily, this would have the opposite effect and prevent mineral extractions from being a long-term sustainable practice, and would result in a shortage of required metals. Any seawater mineral extractions also risk disrupting the habitat of the underwater life that is dependent on the uninterrupted ecosystem within their environment as disturbances can have significant disturbances on animal communities.

See also

* * * * * global ocean salinity * * * * * * * *References

External links

Technical Papers in Marine Science 44, Algorithms for computation of fundamental properties of seawater, ioc-unesco.org, UNESCO 1983

Tables

Tables and software for thermophysical properties of seawater

MIT * {{Authority control Aquatic ecology Chemical oceanography Liquid water Physical oceanography Oceanographical terminology