Scott Russell (writer) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

John Scott Russell (9 May 1808,

Scott Russell's experimental work seemed at contrast with

Scott Russell's experimental work seemed at contrast with

Once Russell had a way of observing boats at hitherto unprecedented speeds at the front of his wave of translation, he tackled the more fundamental issue for boat design of finding the hull shape which gives the least resistance. This, he reasoned was concerned with moving the mass of water efficiently out of the way of the hull and then back to fill the gap after it has passed. By careful measurements with dynamometers he validated his theory that a versed sine wave produces the ideal shape.

Initially he thought that the

Once Russell had a way of observing boats at hitherto unprecedented speeds at the front of his wave of translation, he tackled the more fundamental issue for boat design of finding the hull shape which gives the least resistance. This, he reasoned was concerned with moving the mass of water efficiently out of the way of the hull and then back to fill the gap after it has passed. By careful measurements with dynamometers he validated his theory that a versed sine wave produces the ideal shape.

Initially he thought that the

At a time when all previous train ferries were riverine vessels, in 1868 Scott Russell designed a train ferry for service on

At a time when all previous train ferries were riverine vessels, in 1868 Scott Russell designed a train ferry for service on

Although his design for the Great Exhibition was trumped by that of

Although his design for the Great Exhibition was trumped by that of

In 1838 he was awarded the gold

In 1838 he was awarded the gold

John Scott Russell and the solitary wave

{{DEFAULTSORT:Russell, John Scott 1808 births 1882 deaths 19th-century Scottish engineers Engineers from Glasgow British naval architects Alumni of the University of Glasgow Academics of the University of Edinburgh Shipbuilding in London Fluid dynamicists Fellows of the Royal Society Fellows of the Royal Society of Edinburgh Scottish shipbuilders Alumni of the University of Edinburgh Alumni of the University of St Andrews Scottish Engineering Hall of Fame inductees 19th-century Scottish businesspeople Scottish company founders Fellows of the Royal Society of Arts

Parkhead

Parkhead () is a district in the East End of Glasgow. Its name comes from a small weaving hamlet (place), hamlet at the meeting place of the Great Eastern Road (now the Gallowgate and Tollcross Road) and Westmuir Street. Glasgow's Eastern Necro ...

, Glasgow

Glasgow is the Cities of Scotland, most populous city in Scotland, located on the banks of the River Clyde in Strathclyde, west central Scotland. It is the List of cities in the United Kingdom, third-most-populous city in the United Kingdom ...

– 8 June 1882, Ventnor

Ventnor () is a seaside resort town and civil parishes in England, civil parish established in the Victorian era on the southeast coast of the Isle of Wight, England, from Newport, Isle of Wight, Newport. It is situated south of St Boniface D ...

, Isle of Wight) was a Scottish civil engineer

A civil engineer is a person who practices civil engineering – the application of planning, designing, constructing, maintaining, and operating infrastructure while protecting the public and environmental health, as well as improving existing i ...

, naval architect This is the top category for all articles related to architecture and its practitioners.

{{Commons category, Architecture by occupation

Design occupations

Occupations

Occupation commonly refers to:

*Occupation (human activity), or job, one's rol ...

and shipbuilder who built '' Great Eastern'' in collaboration with Isambard Kingdom Brunel

Isambard Kingdom Brunel ( ; 9 April 1806 – 15 September 1859) was an English civil engineer and mechanical engineer who is considered "one of the most ingenious and prolific figures in engineering history", "one of the 19th-century engi ...

. He made the discovery of the wave of translation that gave birth to the modern study of soliton

In mathematics and physics, a soliton is a nonlinear, self-reinforcing, localized wave packet that is , in that it preserves its shape while propagating freely, at constant velocity, and recovers it even after collisions with other such local ...

s, and developed the wave-line system of ship construction.

Russell was a promoter of the Great Exhibition of 1851

Great may refer to:

Descriptions or measurements

* Great, a relative measurement in physical space, see Size

* Greatness, being divine, majestic, superior, majestic, or transcendent

People

* List of people known as "the Great"

* Artel Great (bo ...

.

Early life

John Russell was born on the 9th May 1808 with in Parkhead, Glasgow, the son of Reverend David Russell and Agnes Clark Scott. He spent one year at theUniversity of St. Andrews

The University of St Andrews (, ; abbreviated as St And in post-nominals) is a public university in St Andrews, Scotland. It is the oldest of the four ancient universities of Scotland and, following the universities of Oxford and Cambridge, t ...

before transferring to the University of Glasgow

The University of Glasgow (abbreviated as ''Glas.'' in Post-nominal letters, post-nominals; ) is a Public university, public research university in Glasgow, Scotland. Founded by papal bull in , it is the List of oldest universities in continuous ...

. It was while at the University of Glasgow that he added his mother's maiden name, Scott, to his own, to become John Scott Russell. He graduated from Glasgow University in 1825 at the age of 17 and moved to Edinburgh

Edinburgh is the capital city of Scotland and one of its 32 Council areas of Scotland, council areas. The city is located in southeast Scotland and is bounded to the north by the Firth of Forth and to the south by the Pentland Hills. Edinburgh ...

where he taught mathematics and science at the Leith Mechanics' Institute

Mechanics' institutes, also known as mechanics' institutions, sometimes simply known as institutes, and also called schools of arts (especially in the Australian colonies), were educational establishments originally formed to provide adult edu ...

, achieving the highest attendance in the city.

On the death of Sir John Leslie

Sir John Leslie, FRSE KH (10 April 1766 – 3 November 1832) was a Scottish mathematician and physicist best remembered for his research into heat.

Leslie gave the first modern account of capillary action in 1802 and froze water using an ai ...

, Professor of Natural Philosophy

Natural philosophy or philosophy of nature (from Latin ''philosophia naturalis'') is the philosophical study of physics, that is, nature and the physical universe, while ignoring any supernatural influence. It was dominant before the develop ...

at the University of Edinburgh

The University of Edinburgh (, ; abbreviated as ''Edin.'' in Post-nominal letters, post-nominals) is a Public university, public research university based in Edinburgh, Scotland. Founded by the City of Edinburgh Council, town council under th ...

in 1832, Scott Russell, though only 24 years old, was elected to temporarily fill the vacancy pending the election of a permanent professor, due to his proficiency in the natural sciences and popularity as a lecturer. But although encouraged to stand for the permanent position he refused to compete with another candidate he admired and thereafter concentrated the engineering profession and experimental research on a large scale.

Family life

He married Harriette Osborne, daughter of the Irish baronet Sir Daniel Toler Osborne and Harriette Trench, daughter of theEarl of Clancarty

Earl of Clancarty is a title that has been created twice in the Peerage of Ireland.

History

The title was created for the first time in 1658 in favour of Donough MacCarty, 2nd Viscount Muskerry, of the MacCarthy of Muskerry dynasty. He had ...

in Dublin

Dublin is the capital and largest city of Republic of Ireland, Ireland. Situated on Dublin Bay at the mouth of the River Liffey, it is in the Provinces of Ireland, province of Leinster, and is bordered on the south by the Dublin Mountains, pa ...

in 1839; they had two sons (Norman survived) and three daughters, Louise (1841–1878), Rachel (1845–1882) and Alice. In London they lived for five years in a house provided for the secretary of the Society of Arts

The Royal Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce, commonly known as the Royal Society of Arts (RSA), is a learned society that champions innovation and progress across a multitude of sectors by fostering creativity, s ...

and then moved to Sydenham Hill

Sydenham Hill forms part of Norwood Ridge, a longer ridge and is an affluent Human settlement, locality in southeast London. It is also the name of a road which runs along the northeastern part of the ridge, demarcating the London Boroughs of ...

, which became a centre of attention especially after Russell and his friends moved Paxton's glasshouse for the Great Exhibition

The Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations, also known as the Great Exhibition or the Crystal Palace Exhibition (in reference to the temporary structure in which it was held), was an international exhibition that took ...

to the Crystal Palace

The Crystal Palace was a cast iron and plate glass structure, originally built in Hyde Park, London, to house the Great Exhibition of 1851. The exhibition took place from 1 May to 15 October 1851, and more than 14,000 exhibitors from around ...

close by.

Arthur Sullivan

Sir Arthur Seymour Sullivan (13 May 1842 – 22 November 1900) was an English composer. He is best known for 14 comic opera, operatic Gilbert and Sullivan, collaborations with the dramatist W. S. Gilbert, including ''H.M.S. Pinaf ...

and his friend Frederic Clay

Frederic Emes Clay (3 August 1838 – 24 November 1889) was an English composer known principally for songs and his music written for the stage.

Although from a musical family, for 16 years Clay made his living as a civil servant in HM Treasury ...

were frequent visitors at the Scott Russell home in the mid-1860s; Clay became engaged to Alice, and Sullivan wooed Rachel. While Clay was from a wealthy family, Sullivan was still a poor young composer from a poor family; the Scott Russells welcomed the engagement of Alice to Clay, who, however broke it off, but forbade the relationship between Sullivan and Rachel, although the two continued to see each other covertly. At some point in 1868, Sullivan started a simultaneous (and secret) affair with Louise (1841–1878). Both relationships had ceased by early 1869.

The American engineer Alexander Lyman Holley

Alexander Lyman Holley ( Lakeville, Connecticut, July 20, 1832 – Brooklyn, New York, January 29, 1882) was an American mechanical engineer, inventor, and founding member of the American Society of Mechanical Engineers (ASME). He was consid ...

befriended Scott Russell and his family on his various visits to London at the time of the construction of ''Great Eastern''. Holley also visited Scott Russell's house in Sydenham. As a result of this, Holley, and his colleague Zerah Colburn, travelled on the maiden voyage of ''Great Eastern'' from Southampton to New York in June 1860. Scott Russell's son, Norman, stayed with Holley at his house in Brooklyn — Norman also travelled on the maiden voyage, one voyage that John Scott Russell did not make.

His son, Norman, followed his father in becoming a naval architect, contributing to the Institution of Naval Architects which his father had founded.

Steam carriage

While in Edinburgh he experimented with steam engines, using a square boiler for which he developed a method of staying the surface of the boiler which became universal. The ''Scottish Steam Carriage Company'' was formed producing a steam carriage with two cylinders developing 12 horsepower each. Six were constructed in 1834, well-sprung and fitted out to high standard, which from March 1834 ran between Glasgow'sGeorge Square

George Square () is the principal Town square, civic square in the city of Glasgow, Scotland. It is one of six squares in the city centre, the others being Cathedral Square, Glasgow, Cathedral Square, St Andrew's Square, Glasgow, St Andrew's ...

and the Tontine Hotel in Paisley at hourly intervals at 15 mph. The road trustees objected that it wore out the road and placed various obstructions of logs and stones in the road, which actually caused more discomfort for horse-drawn carriages. But in July 1834 one of the carriages was overturned and the boiler smashed, causing the death of several passengers. Two of the coaches were sent to London where they ran for a short time between London and Greenwich.

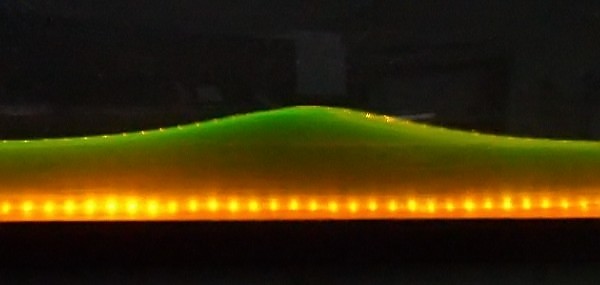

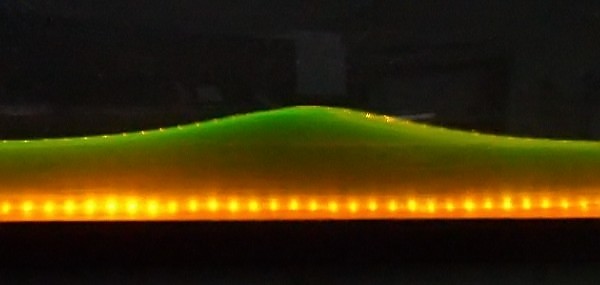

The wave of translation

In 1834, while conducting experiments to determine the most efficient design for canal boats, he discovered a phenomenon that he described as the wave of translation. Influid dynamics

In physics, physical chemistry and engineering, fluid dynamics is a subdiscipline of fluid mechanics that describes the flow of fluids – liquids and gases. It has several subdisciplines, including (the study of air and other gases in motion ...

the wave is now called Russell's solitary wave. The discovery is described here in his own words:

I was observing the motion of a boat which was rapidly drawn along a narrow channel by a pair of horses, when the boat suddenly stopped—not so the mass of water in the channel which it had put in motion; it accumulated round the prow of the vessel in a state of violent agitation, then suddenly leaving it behind, rolled forward with great velocity, assuming the form of a large solitary elevation, a rounded, smooth and well-defined heap of water, which continued its course along the channel apparently without change of form or diminution of speed. I followed it on horseback, and overtook it still rolling on at a rate of some eight or nine miles an hour 4 km/h preserving its original figure some thirty feet mlong and a foot to a foot and a half 0−45 cmin height. Its height gradually diminished, and after a chase of one or two miles –3 kmI lost it in the windings of the channel. Such, in the month of August 1834, was my first chance interview with that singular and beautiful phenomenon which I have called the Wave of Translation.The phenomenon of solitary waves had previously been reported in 1826 by Giorgio Bidone in

Turin

Turin ( , ; ; , then ) is a city and an important business and cultural centre in northern Italy. It is the capital city of Piedmont and of the Metropolitan City of Turin, and was the first Italian capital from 1861 to 1865. The city is main ...

, but Bidone's work seems to have gone unnoticed by researchers in the Netherlands and Britain, despite being mentioned in the Edinburgh Journal of Science in the same year.

Scott Russell spent some time making practical and theoretical investigations of these waves. He built wave tanks at his home and noticed some key properties:

* The waves are stable, and can travel over very large distances (normal waves would tend to either flatten out, or steepen and topple over)

* The speed depends on the size of the wave, and its width on the depth of water.

* Unlike normal waves they will never merge—so a small wave is overtaken by a large one, rather than the two combining.

* If a wave is too big for the depth of water, it splits into two, one big and one small.

Scott Russell's experimental work seemed at contrast with

Scott Russell's experimental work seemed at contrast with Isaac Newton

Sir Isaac Newton () was an English polymath active as a mathematician, physicist, astronomer, alchemist, theologian, and author. Newton was a key figure in the Scientific Revolution and the Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment that followed ...

's and Daniel Bernoulli

Daniel Bernoulli ( ; ; – 27 March 1782) was a Swiss people, Swiss-France, French mathematician and physicist and was one of the many prominent mathematicians in the Bernoulli family from Basel. He is particularly remembered for his applicati ...

's theories of hydrodynamics

In physics, physical chemistry and engineering, fluid dynamics is a subdiscipline of fluid mechanics that describes the flow of fluids – liquids and gases. It has several subdisciplines, including (the study of air and other gases in ...

. George Biddell Airy

Sir George Biddell Airy (; 27 July 18012 January 1892) was an English mathematician and astronomer, as well as the Lucasian Professor of Mathematics from 1826 to 1828 and the seventh Astronomer Royal from 1835 to 1881. His many achievements inc ...

and George Gabriel Stokes

Sir George Gabriel Stokes, 1st Baronet, (; 13 August 1819 – 1 February 1903) was an Irish mathematician and physicist. Born in County Sligo, Ireland, Stokes spent his entire career at the University of Cambridge, where he served as the Lucasi ...

had difficulty to accept Scott Russell's experimental observations because Scott Russell's observations could not be explained by the existing water-wave theories. Additional observations were reported by Henry Bazin in 1862 after experiments carried out in the canal de Bourgogne

The Canal de Bourgogne (; English: Canal of Burgundy or Burgundy Canal) is a canal in the Burgundy historical region in east-central France. It connects the Yonne (river), Yonne at Migennes with the Saône at Saint-Jean-de-Losne. Construction beg ...

in France. In 1863, Bazin authored a research paper titled ' (English: ''Hydraulic Researches Undertaken by M.H. Darcy'') which featured the work of Scott Russell.

A Dutch translation of Bazin's work entitled ' (English: ''Report to the French Academy of Sciences on the portion of Bazin's treatise relating to surges and the propagation of waves'') was featured in the proceedings of the Dutch ' (English: ''Royal Institute of Engineers'') in 1869. Within the original French paper, and the translated work, the velocity of a solitary wave is given as:

The formula is denoted as "the law of Scott Russell" within the text. His contemporaries spent some time attempting to extend the theory but it would take until the 1870s before an explanation was provided.

Lord Rayleigh

John William Strutt, 3rd Baron Rayleigh ( ; 12 November 1842 – 30 June 1919), was an English physicist who received the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1904 "for his investigations of the densities of the most important gases and for his discovery ...

published a paper in Philosophical Magazine in 1876 to support John Scott Russell's experimental observation with his mathematical theory. In his 1876 paper, Lord Rayleigh mentioned Scott Russell's name and also admitted that the first theoretical treatment was by Joseph Valentin Boussinesq

Joseph Valentin Boussinesq (; 13 March 1842 – 19 February 1929) was a French mathematician and physicist who made significant contributions to the theory of hydrodynamics, vibration, light, and heat.

Biography

From 1872 to 1886, he was appoin ...

in 1871; Boussinesq had mentioned Scott Russell's name in his 1871 paper. Thus Scott Russell's observations on solitary waves were accepted as true by some prominent scientists within his own lifetime.

Korteweg and de Vries

De Vries is one of the most common Netherlands, Dutch surnames. It indicates a geographical origin: "Vriesland" is an old spelling of the Netherlands, Dutch province of Friesland (Frisia). Hence, "de Vries" means "the Frisian". The name has been m ...

did not mention John Scott Russell's name at all in their 1895 paper but they did quote Boussinesq's paper in 1871 and Lord Rayleigh's paper in 1876. Although the paper by Korteweg and de Vries in 1895 was not the first theoretical treatment of this subject, it was a very important milestone in the history of the development of soliton

In mathematics and physics, a soliton is a nonlinear, self-reinforcing, localized wave packet that is , in that it preserves its shape while propagating freely, at constant velocity, and recovers it even after collisions with other such local ...

theory.

It was not until the 1960s and the advent of modern computers that the significance of Scott Russell's discovery in physics

Physics is the scientific study of matter, its Elementary particle, fundamental constituents, its motion and behavior through space and time, and the related entities of energy and force. "Physical science is that department of knowledge whi ...

, electronics

Electronics is a scientific and engineering discipline that studies and applies the principles of physics to design, create, and operate devices that manipulate electrons and other Electric charge, electrically charged particles. It is a subfield ...

, biology

Biology is the scientific study of life and living organisms. It is a broad natural science that encompasses a wide range of fields and unifying principles that explain the structure, function, growth, History of life, origin, evolution, and ...

and especially fibre optics

An optical fiber, or optical fibre, is a flexible glass or plastic fiber that can transmit light from one end to the other. Such fibers find wide usage in fiber-optic communications, where they permit transmission over longer distances and at ...

started to become understood, leading to the modern general theory of solitons.

Note that solitons are, by definition, unaltered in shape and speed by a collision with other solitons. So solitary waves on a water surface are not solitons – after the interaction of two (colliding or overtaking) solitary waves, they have changed slightly in amplitude

The amplitude of a periodic variable is a measure of its change in a single period (such as time or spatial period). The amplitude of a non-periodic signal is its magnitude compared with a reference value. There are various definitions of am ...

and an oscillatory residual is left behind.

Wave line system

Once Russell had a way of observing boats at hitherto unprecedented speeds at the front of his wave of translation, he tackled the more fundamental issue for boat design of finding the hull shape which gives the least resistance. This, he reasoned was concerned with moving the mass of water efficiently out of the way of the hull and then back to fill the gap after it has passed. By careful measurements with dynamometers he validated his theory that a versed sine wave produces the ideal shape.

Initially he thought that the

Once Russell had a way of observing boats at hitherto unprecedented speeds at the front of his wave of translation, he tackled the more fundamental issue for boat design of finding the hull shape which gives the least resistance. This, he reasoned was concerned with moving the mass of water efficiently out of the way of the hull and then back to fill the gap after it has passed. By careful measurements with dynamometers he validated his theory that a versed sine wave produces the ideal shape.

Initially he thought that the stern

The stern is the back or aft-most part of a ship or boat, technically defined as the area built up over the sternpost, extending upwards from the counter rail to the taffrail. The stern lies opposite the bow, the foremost part of a ship. O ...

could be a mirror of the stem

Stem or STEM most commonly refers to:

* Plant stem, a structural axis of a vascular plant

* Stem group

* Science, technology, engineering, and mathematics

Stem or STEM can also refer to:

Language and writing

* Word stem, part of a word respon ...

, but soon realised that the removing water produced something closer to conventional waves than his solitary waves and ended up with a rounded stern with a catenary

In physics and geometry, a catenary ( , ) is the curve that an idealized hanging chain or wire rope, cable assumes under its own weight when supported only at its ends in a uniform gravitational field.

The catenary curve has a U-like shape, ...

shape.

His studies produced a revolution in the design of hulls for merchant and navy vessels. Most ships of the time had rounded bows to optimise the cargo-carrying capacity, but starting from the 1840s the "extreme clipper ship

A clipper was a type of mid-19th-century Merchant ship, merchant Sailing ship, sailing vessel, designed for speed. The term was also retrospectively applied to the Baltimore clipper, which originated in the late 18th century.

Clippers were gen ...

s" started to show concave bows as increasingly did steam ships culminating with ''Great Eastern''. After his views were propounded by Commander Fishbourne, the American naval architect John W. Griffiths acknowledged the force of Russell's work in his ''Treatise on marine and naval architecture'' of 1850 though he was grudging in acknowledging a debt to Russell.

Doppler effect

Scott Russell made one of the first experimental observations of theDoppler effect

The Doppler effect (also Doppler shift) is the change in the frequency of a wave in relation to an observer who is moving relative to the source of the wave. The ''Doppler effect'' is named after the physicist Christian Doppler, who described ...

which he published in 1848. Christian Doppler

Christian Andreas Doppler (; ; 29 November 1803 – 17 March 1853) was an Austrian mathematician and physicist. He formulated the principle – now known as the Doppler effect – that the observed frequency of a wave depends on the relative spe ...

published his theory in 1842.

Professional association

Much of Russell's early experimental work had been conducted under the auspices of theBritish Association

The British Science Association (BSA) is a charity and learned society founded in 1831 to aid in the promotion and development of science. Until 2009 it was known as the British Association for the Advancement of Science (BA). The current Chief ...

and throughout his life he contributed to the scientific and professional associations that were becoming more important in that era.

In 1844, the railway boom was at its height. Russell had contributed an article on the Steam engine and steam navigation for the 7th edition of Encyclopædia Britannica

The is a general knowledge, general-knowledge English-language encyclopaedia. It has been published by Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. since 1768, although the company has changed ownership seven times. The 2010 version of the 15th edition, ...

in 1841 which also appeared in book form. Charles Wentworth Dilke

Charles Wentworth Dilke (1789–1864) was an English liberal critic and writer on literature.

Professional life

He served for many years in the Navy Pay-Office, on retiring from which in 1830 he devoted himself to literary pursuits.

Lite ...

offered him the editorial position of a new weekly paper, the ''Railway Chronicle'' in London and the Russell family was soon in a small two-room flat in Westminster

Westminster is the main settlement of the City of Westminster in Central London, Central London, England. It extends from the River Thames to Oxford Street and has many famous landmarks, including the Palace of Westminster, Buckingham Palace, ...

. The next year he also became the secretary of the committee set up by the Royal Society of Arts

The Royal Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce, commonly known as the Royal Society of Arts (RSA), is a learned society that champions innovation and progress across a multitude of sectors by fostering creativity, s ...

to organise a national exhibition, which provided them with a town house in the Strand

Strand or The Strand may refer to:

Topography

*The flat area of land bordering a body of water, a:

** Beach

** Shoreline

* Strand swamp, a type of swamp habitat in Florida

Places Africa

* Strand, Western Cape, a seaside town in South Africa

* ...

. Russell soon introduced Henry Cole Henry Cole may refer to:

*Sir Henry Cole (inventor)

Sir Henry Cole FRSA (15 July 1808 – 15 April 1882) was an English civil servant and inventor who facilitated many innovations in commerce, education and the arts in the 19th century in the ...

to the committee and when, a few weeks before the first exhibition in 1847, there were no exhibitors, Russell and Cole spent three whole days travelling around London to enlist manufacturers and shopkeepers. This and two subsequent exhibitions were such a success that an international version was planned for 1851. By this time Russell had once again started shipbuilding, the railway boom having finished, and although he became the RSA's appointed secretary for the Great Exhibition

The Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations, also known as the Great Exhibition or the Crystal Palace Exhibition (in reference to the temporary structure in which it was held), was an international exhibition that took ...

, Henry Cole was by this time taking the lead, and he ended up with only a Gold Medal as his reward for much work.

Russell became a member of the Institution of Civil Engineers

The Institution of Civil Engineers (ICE) is an independent professional association for civil engineers and a Charitable organization, charitable body in the United Kingdom. Based in London, ICE has over 92,000 members, of whom three-quarters ar ...

in 1847 attending regularly and making frequent contributions, was elected to its council in 1857 and became a vice-president in 1862. However he became involved in a financial dispute with Sir William Armstrong and didn't become president. But "as a speaker, and particularly as an after-dinner speaker, he had few equals." He was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society

Fellowship of the Royal Society (FRS, ForMemRS and HonFRS) is an award granted by the Fellows of the Royal Society of London to individuals who have made a "substantial contribution to the improvement of natural science, natural knowledge, incl ...

in 1849 although he contributed less.

In 1860 at a meeting at his house in Sydenham, the Institution of Naval Architects

The Royal Institution of Naval Architects (also known as RINA) is a professional institution and global governing body for naval architecture and maritime engineering. Members work in industry, academia, and maritime organisations worldwide, part ...

was set up, with Russell as one of the professional vice-presidents. He attended most meetings and rarely failed to comment. In 1864 he published a massive 3-volume treatise on ''The Modern System of Naval Architecture'' which laid out the profiles of many of the new ships being built.

His obituary said of naval architecture:

:"it may be said that on commencing his career he found it the most empirical of arts, and he left it one of the most exact of engineering sciences. To this great result many others contributed largely besides himself; but his personal investigations, and the theories which he deduced from them, gave the first impetus to scientific naval architecture".

Ship building

From around 1838, Scott Russell was employed at the smallGreenock

Greenock (; ; , ) is a town in Inverclyde, Scotland, located in the west central Lowlands of Scotland. The town is the administrative centre of Inverclyde Council. It is a former burgh within the historic county of Renfrewshire, and forms ...

shipyard of Thomson and Spiers where he introduced his wave-line system to a series of Royal Mail

Royal Mail Group Limited, trading as Royal Mail, is a British postal service and courier company. It is owned by International Distribution Services. It operates the brands Royal Mail (letters and parcels) and Parcelforce Worldwide (parcels) ...

ships, together with many other innovations. After the shipyard was taken over by Caird, he decided to move to London and in 1848 purchased the Millwall Iron Works

The Millwall Iron Works, London, England, was a 19th-century industrial complex and series of companies, which developed from 1824. Formed from a series of small shipbuilding companies to address the need to build larger and larger ships, the hol ...

shipbuilding

Shipbuilding is the construction of ships and other Watercraft, floating vessels. In modern times, it normally takes place in a specialized facility known as a shipyard. Shipbuilders, also called shipwrights, follow a specialized occupation th ...

company. He built two ships for Brunel for the Australia run, much the same size as Brunel's SS Great Britain

SS ''Great Britain'' is a museum ship and former passenger steamship that was advanced for her time. The largest passenger ship in the world from 1845 to 1853, she was designed by Isambard Kingdom Brunel (1806–1859), for the Great Western ...

, ''Adelaide'' and ''Victoria''. Problems with refuelling and water led Brunel to think in terms of larger ships for this voyage, but five more were built in the same class.

Before they started any business together, he was held in high regard by Isambard Kingdom Brunel

Isambard Kingdom Brunel ( ; 9 April 1806 – 15 September 1859) was an English civil engineer and mechanical engineer who is considered "one of the most ingenious and prolific figures in engineering history", "one of the 19th-century engi ...

who made him a partner in his project to build '' Great Eastern''.

Although the original conception, the cellular construction and the joint use of paddle and screw were Brunel's ideas, "the ship embodies the wave-line form, the longitudinal system of construction, the complete and partial bulkheads, and other details of construction which were peculiarly Scott Russell’s".

The project was plagued with a number of problems—Scott Russell put in a bid which was far too low with the result that he was bankrupt halfway through, though he recovered to finish the job; but it was Brunel that insisted on a sideways launch rather than the dry dock that Russell preferred. ''Great Eastern'' was eventually launched in 1858. Scott Russell was a better scientist than a businessman and his reputation never fully recovered from his financial irregularities, gross neglect of duty and disputes. As L. T. C. Rolt writes in his biography of Brunel "That Russell had indeed misled Brunel and betrayed his trust was now becoming the more lamentably apparent with every day that passed".

During the 1850s he argued within the Navy for the construction of iron warships and the first design, , is said by some to be a "Russell ship". He afterwards complained about the secrecy that prevented an open discussion of the issues, criticizing those within the Navy who argued that iron ships could not be protected.

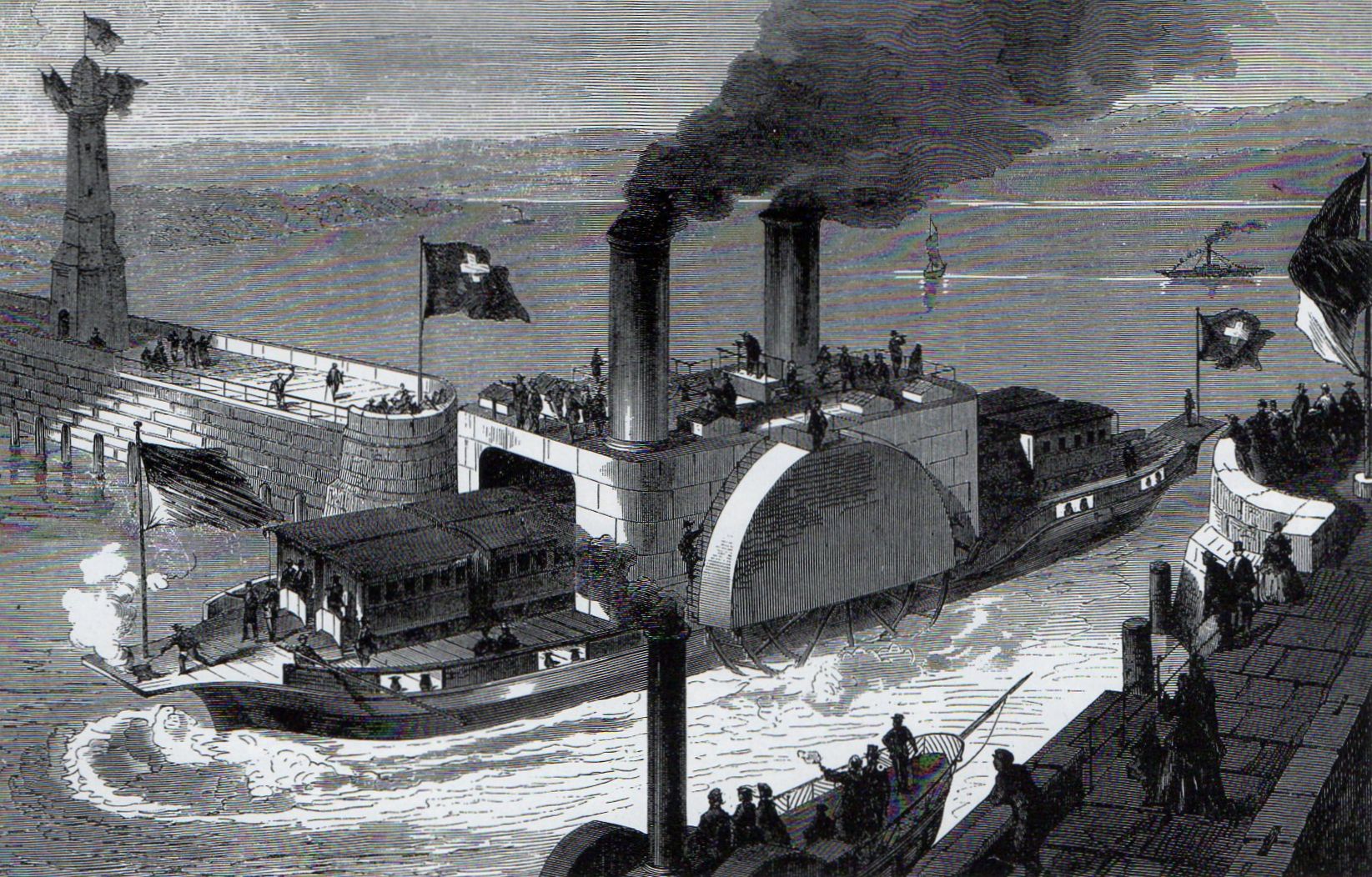

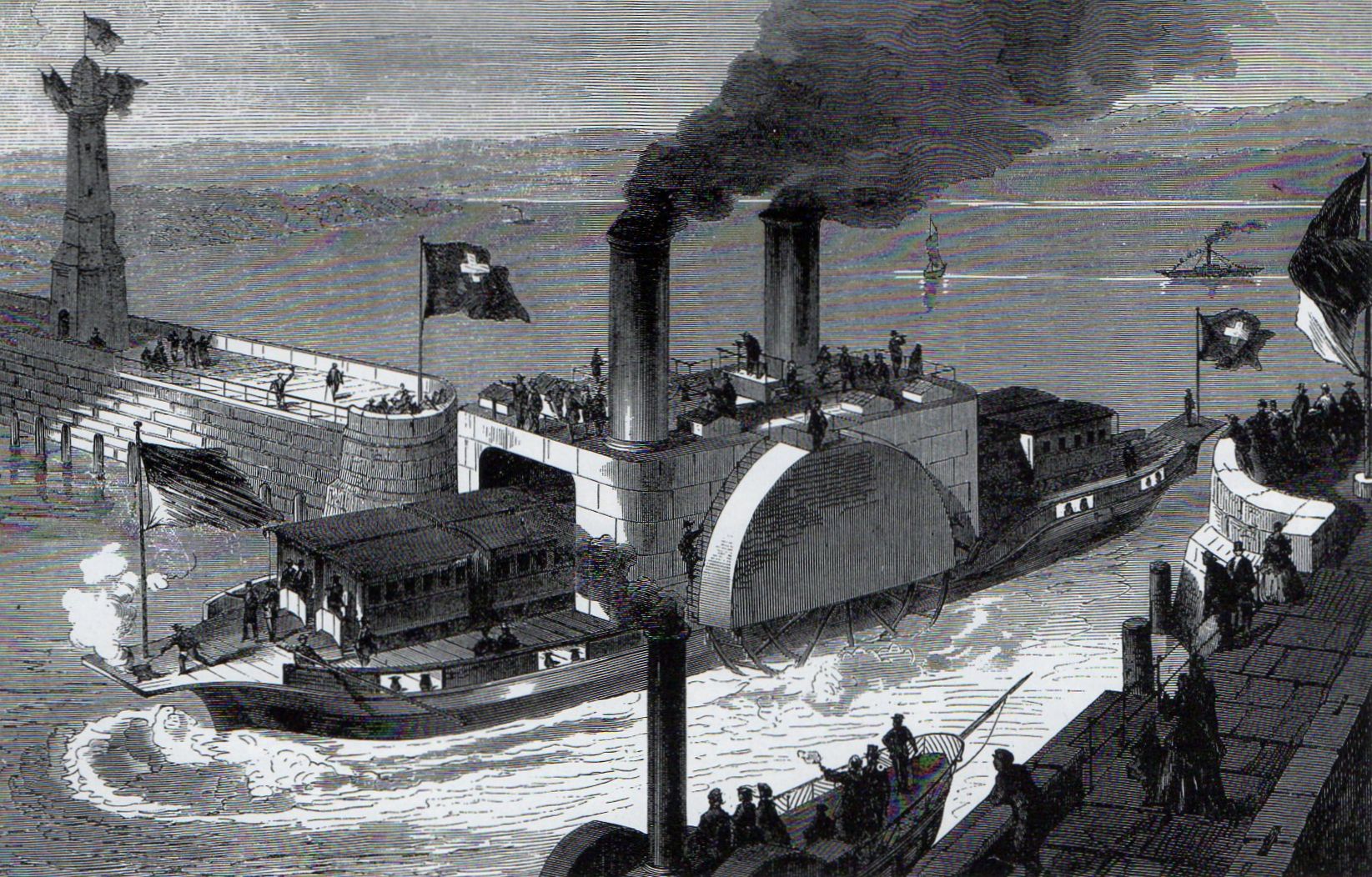

At a time when all previous train ferries were riverine vessels, in 1868 Scott Russell designed a train ferry for service on

At a time when all previous train ferries were riverine vessels, in 1868 Scott Russell designed a train ferry for service on Lake Constance

Lake Constance (, ) refers to three bodies of water on the Rhine at the northern foot of the Alps: Upper Lake Constance (''Obersee''), Lower Lake Constance (''Untersee''), and a connecting stretch of the Rhine, called the Seerhein (). These ...

, the ''Bodensee Trajekt'', which entered service in 1869. This was the world's first cross-lake train ferry. The ''Bodensee Trajekt'' had to meet the unusual requirement that its draft not exceed six feet (1.85m). He achieved this by using the superstructure to carry the stresses of the train. (It was not until 1892 that the first Lake Michigan

Lake Michigan ( ) is one of the five Great Lakes of North America. It is the second-largest of the Great Lakes by volume () and depth () after Lake Superior and the third-largest by surface area (), after Lake Superior and Lake Huron. To the ...

cross-lake train ferry, the ''Ann Arbor No. 1'', designed by Frank E. Kirby Frank E. Kirby (July 1, 1849 – August 25, 1929) was a naval architect in the Detroit, Michigan (United States) area in the early 20th century. He is widely regarded as one of the greatest naval architects in United States, American history.

Biog ...

, entered service.) Scott Russell used the design of the ''Bodensee Trajekt'' as the basis of a cross-channel ferry that could manage the shallow harbour of Dover, but this was not realised until 1933.

The Vienna Rotunda

Although his design for the Great Exhibition was trumped by that of

Although his design for the Great Exhibition was trumped by that of Joseph Paxton

Sir Joseph Paxton (3 August 1803 – 8 June 1865) was an English gardener, architect, engineer and Liberal Party (UK), Liberal Member of Parliament. He is best known for designing the Crystal Palace, which was built in Hyde Park, London, Hyde ...

, Scott Russell did design the Rotunde

The Rotunde () in Vienna's Leopoldstadt district was a building erected for the 1873 Vienna World's Fair (). The building was a partially covered circular wrought iron construction, tall, with a diameter of . While the Rotunda stood, its dome w ...

for the 1873 Vienna Exposition. At in diameter it was for nearly a century the largest cupola in the world, having no ties to obstruct the view. Some consider it his greatest structural engineering achievement.

Honours and awards

In 1838 he was awarded the gold

In 1838 he was awarded the gold Keith Medal

The Keith Medal was a prize awarded by the Royal Society of Edinburgh, Scotland's national academy, for a scientific paper published in the society's scientific journals, preference being given to a paper containing a discovery, either in mathema ...

by the Royal Society of Edinburgh for his paper "On the Laws by which water opposes Resistance to the Motion of Floating Bodies".

He was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society

Fellowship of the Royal Society (FRS, ForMemRS and HonFRS) is an award granted by the Fellows of the Royal Society of London to individuals who have made a "substantial contribution to the improvement of natural science, natural knowledge, incl ...

in June 1849 for ''Memoirs on "The great Solitary Wave of the First Order, or the Wave of Translation" published in the Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh, and of several Memoirs in the Reports of the British Association''.

In 1995, the aqueduct which carries the Union Canal – the same canal where he observed his Wave of Translation – over the Edinburgh Bypass (A720) was named the Scott Russell Aqueduct in his memory. Also in 1995, the hydrodynamic soliton effect was reproduced near the place where John Scott Russell observed hydrodynamic solitons in 1834.

A building at Heriot-Watt University

Heriot-Watt University () is a public research university based in Edinburgh, Scotland. It was established in 1821 as the School of Arts of Edinburgh, the world's first mechanics' institute, and was subsequently granted university status by roya ...

is named after him.

In 2019 he was inducted into the Scottish Engineering Hall of Fame

The Scottish Engineering Hall of Fame honours "those engineers from, or closely associated with, Scotland who have achieved, or deserve to achieve, greatness", as selected by an independent panel representing Scottish engineering institutions, aca ...

Publications

His 1844 paper has become a classical paper and is quite frequently cited insoliton

In mathematics and physics, a soliton is a nonlinear, self-reinforcing, localized wave packet that is , in that it preserves its shape while propagating freely, at constant velocity, and recovers it even after collisions with other such local ...

-related papers or books even after more than one hundred and fifty years.

*

*

*

Notes

Sources

* * includes discussion on the discovery of solitons * *External links

John Scott Russell and the solitary wave

{{DEFAULTSORT:Russell, John Scott 1808 births 1882 deaths 19th-century Scottish engineers Engineers from Glasgow British naval architects Alumni of the University of Glasgow Academics of the University of Edinburgh Shipbuilding in London Fluid dynamicists Fellows of the Royal Society Fellows of the Royal Society of Edinburgh Scottish shipbuilders Alumni of the University of Edinburgh Alumni of the University of St Andrews Scottish Engineering Hall of Fame inductees 19th-century Scottish businesspeople Scottish company founders Fellows of the Royal Society of Arts