Origin of the term

The term was found in English in a 1937 report on theMilitary theory

Historic examples

Notable historic examples of successful scorched-earth tactics include the failed6th century BCE

European Scythian campaign

The4th century BCE

March of the Ten Thousand

The Greek general3rd century BCE

Second Punic War

During the2nd century BCE

Third Punic War

After the end of the1st century BCE

Gallic Wars

The system of punitive destruction of property and subjugation of people when accompanying a military campaign was known as ''vastatio''. Two of the first uses of scorched earth recorded happened in the4th century CE

Roman invasion of Persia

In the year CE 363, the Emperor Julian's invasion of Persia was turned back by a scorched-earth policy:7th century CE

First Fitna

During the9th century CE

Viking invasion of England

During the Viking invasion of England, the Viking chieftain11th century

Harrying of the North

In the14th century

Hundred Years' War

During the

During the Wars of Scottish Independence

ACrusades

A strategy of slighting castles in Palestine was also adopted by the Mamlukes during their wars with the Crusades, Crusaders.15th century

Moldavian–Ottoman Wars

Stephen the Great used scorched earth in the Carpathians against the Ottoman Army in 1475 and 1476.Wallachian–Ottoman Wars

In 1462, a massive Ottoman army, led by Sultan Mehmed II, marched into Wallachia. Vlad the Impaler retreated to Transylvania. During his departure, he conducted scorched-earth tactics to ward off Mehmed's approach. When the Ottoman forces approached Tirgoviste, they encountered over 20,000 people impalement, impaled by the forces of Vlad the Impaler, creating a "forest" of dead or dying bodies on stakes. The atrocious, gut-wrenching sight caused Mehmed to withdraw from battle and send instead Radu, Vlad's brother, to fight Vlad the Impaler.

In 1462, a massive Ottoman army, led by Sultan Mehmed II, marched into Wallachia. Vlad the Impaler retreated to Transylvania. During his departure, he conducted scorched-earth tactics to ward off Mehmed's approach. When the Ottoman forces approached Tirgoviste, they encountered over 20,000 people impalement, impaled by the forces of Vlad the Impaler, creating a "forest" of dead or dying bodies on stakes. The atrocious, gut-wrenching sight caused Mehmed to withdraw from battle and send instead Radu, Vlad's brother, to fight Vlad the Impaler.

16th century

Anglicisation of the Irish

Further use of scorched-earth policies in war was seen during the 16th century in Ireland, where it was used by English commanders such as Walter Devereux, 1st Earl of Essex, Walter Devereux and Richard Bingham (soldier), Richard Bingham. The Desmond Rebellions were a famous case in Ireland. Much of the province of Munster was laid waste. The poet Edmund Spenser left an account of it:Great Siege of Malta

In early 1565, Grandmaster Jean Parisot de Valette ordered the harvesting of all the crops in Malta, including unripened grain, to deprive the Ottomans of any local food supplies since spies had warned of an imminent Ottoman attack. Furthermore, the Knights well poisoning, poisoned all of the wells with bitter herbs and dead animals. The Ottomans arrived on 18 May, and the Great Siege of Malta began. The Ottomans managed to capture one fort but were eventually defeated by the Knights, the Maltese militia and a Spanish relief force.17th century

Thirty Years' War

In 1630, Generalfeldmarschall, Field-Marshal General Torquato Conti was in command of the Holy Roman Empire's forces during the Thirty Years' War. Forced to retreat from the advancing Swedish army of King Gustavus Adolphus of Sweden, Gustavus Adolphus, Conti ordered his troops to burn houses, destroy villages and cause as much harm generally to property and people as possible.:Nine Years' War

In 1688, France attacked the German Electoral Palatinate. The German states responded by forming an alliance and assembling a sizeable armed force to push the French out of Germany. The French had not prepared for such an eventuality. Realising that the war in Germany was not going to end quickly and that the war would not be a brief and decisive parade of French glory, Louis XIV and War Minister François-Michel le Tellier, Marquis de Louvois, Marquis de Louvois resolved upon a scorched-earth policy in the Palatinate (region), Palatinate, Baden and Württemberg. The French were intent on denying enemy troops local resources and on preventing the Germans from invading France. By 20 December 1688, Louvois had selected all the cities, towns, villages and châteaux intended for destruction. On 2 March 1689, the René de Froulay de Tessé, Count of Tessé torched Heidelberg, and on 8 March, Joseph de Montclar, Montclar levelled Mannheim. Oppenheim and Worms, Germany, Worms were finally destroyed on 31 May, followed by Speyer on 1 June, and Bingen on 4 June. In all, French troops burnt over 20 substantial towns as well as numerous villages.Mughal–Maratha Wars

In the Maratha Empire, Shivaji Maharaj had introduced scorched-earth tactics, known as ''Ganimi Kava''. His forces looted traders and businessmen from Aurangzeb's Mughal Empire and burnt down his cities, but they were strictly ordered not to rape or hurt the innocent civilians and not to cause any sort of disrespect to any of the religious institutes. Shivaji's son, Sambhaji Maharaj, was detested throughout the Mughal Empire for his scorched-earth tactics until he and his men were captured by Muqarrab Khan and his Mughal Army contingent of 25,000. On 11 March 1689, a panel of Mughal qadis indicted and sentenced Sambhaji to death on accusations of casual torture, arson, looting and massacres but most prominently for giving shelter to Sultan Muhammad Akbar, the fourth son of Aurangzeb, who had sought Sambhaji's aid in winning the Mughal throne from the emperor, his father. Sambhaji was particularly condemned for the three days of ravaging committed after the Battle of Burhanpur.18th century

Great Northern War

During the Great Northern War, Russian Emperor Peter the Great's forces used scorched-earth tactics to hold back Swedish King Charles XII's campaign towards Moscow in 1707–1708.Sullivan–Clinton genocide

In 1779 Congress decided to defeat the four British allied nations of the Iroquois decisively during the American Revolutionary War with the Sullivan Expedition. General John Sullivan used a scorched earth campaign by destroying more than 40 Iroquois villages and their stores of winter crops resulting in many deaths by starvation and cold in the following winter.Haitian Revolution against Napoleon

In a letter to Jean-Jacques Dessalines, Toussaint Louverture outlined his plans for defeating the French in the Haitian Revolution starting in 1791 using scorched-earth: "Do not forget, while waiting for the rainy reason which will rid us of our foes, that we have no other resource than destruction and fire. Bear in mind that the soil bathed with our sweat must not furnish our enemies with the smallest sustenance. Tear up the roads with shot; throw corpses and horses into all the foundations, burn and annihilate everything in order that those who have come to reduce us to slavery may have before their eyes the image of the hell which they deserve".19th century

Napoleonic Wars

During the third Peninsular War, Napoleonic invasion of Portugal in 1810, the Portuguese people, Portuguese population retreated towards Lisbon and was ordered to destroy all the food supplies the French might capture as well as forage and shelter in a wide belt across the country. (Although effective food-preserving techniques had recently been invented, they were still not fit for military use because a suitably-rugged container had not yet been invented.) The command was obeyed as a result of French plundering and general ill-treatment of civilians in the previous invasions. The civilians would rather destroy anything that had to be left behind, rather than leave it to the French. When the French armies reached the Lines of Torres Vedras on the way to Lisbon, French soldiers reported that the country "seemed to empty ahead of them". Low morale, hunger, disease and indiscipline greatly weakened the French army and compelled the forces to retreat, see also Attrition warfare against Napoleon. In 1812, Emperor Alexander I of Russia, Alexander I was able to render Napoleon's invasion of Russia useless by using a scorched-earth policy. As Russians withdrew from the advancing French army, they burned the countryside over which they passed (Fire of Moscow (1812), and allegedly Moscow), leaving nothing of value for the pursuing French army. Encountering only desolate and useless land Napoleon's Grande Armée was prevented from using its usual doctrine of living off the lands that it conquered. Pushing relentlessly on despite dwindling numbers, the Grand Army met with disaster as the invasion progressed. Napoleon's army arrived in a virtually-abandoned Moscow, which was a tattered starving shell of its former self, largely because of scorched-earth tactics by the retreating Russians. Having conquered essentially nothing, Napoleon's troops retreated, but the scorched-earth policy came into effect again because even though some large supply dumps had been established on the advance, the route between them had both been scorched and marched over once already. Thus, the French army starved as it marched along the resource-depleted invasion route.

In 1812, Emperor Alexander I of Russia, Alexander I was able to render Napoleon's invasion of Russia useless by using a scorched-earth policy. As Russians withdrew from the advancing French army, they burned the countryside over which they passed (Fire of Moscow (1812), and allegedly Moscow), leaving nothing of value for the pursuing French army. Encountering only desolate and useless land Napoleon's Grande Armée was prevented from using its usual doctrine of living off the lands that it conquered. Pushing relentlessly on despite dwindling numbers, the Grand Army met with disaster as the invasion progressed. Napoleon's army arrived in a virtually-abandoned Moscow, which was a tattered starving shell of its former self, largely because of scorched-earth tactics by the retreating Russians. Having conquered essentially nothing, Napoleon's troops retreated, but the scorched-earth policy came into effect again because even though some large supply dumps had been established on the advance, the route between them had both been scorched and marched over once already. Thus, the French army starved as it marched along the resource-depleted invasion route.

South American War of Independence

In August 1812, Argentina, Argentine General Manuel Belgrano led the Jujuy Exodus, a massive forced displacement of people from what is now Jujuy Province, Jujuy and Salta Province, Salta Provinces to the south. The Jujuy Exodus was conducted by the patriot forces of the Army of the North, which was battling a Royalist (Spanish American Revolution), Royalist army. Belgrano, faced with the prospect of total defeat and territorial loss, ordered all people to pack their necessities, including food and furniture, and to follow him in carriages or on foot together with whatever cattle and beasts of burden that could endure the journey. The rest (houses, crops, food stocks and any objects made of iron) was to be burned to deprive the Royalists of resources. The strict scorched-earth policy made him ask on 29 July 1812 the people of Jujuy to "show their heroism" and to join the march of the army under his command "if, as you assure, you want to be free". The punishment for ignoring the order was execution, with the destruction of the defector's properties. Belgrano labored to win the support of the populace and later reported that most of the people had willingly followed him without the need for force. The exodus started on 23 August and gathered people from San Salvador de Jujuy, Jujuy and Salta Province, Salta. People travelled south about 250 km and finally arrived at the banks of the Pasaje River, in Tucumán Province in the early hours of 29 August. They applied a scorched-earth policy and so the Spaniards advanced into a wasteland. Belgrano's army destroyed everything that could provide shelter or be useful to the Royalists.Greek War of Independence

In 1827, Ibrahim Pasha of Egypt led an Ottoman-Egyptian combined force in a campaign to crush Greek revolutionaries in the Peloponnese. In response to Greek guerrilla attacks on his forces in the Peloponnese, Ibrahim launched a scorched earth campaign that threatened the population with starvation and deported many civilians into slavery in Egypt Eyalet, Egypt. The fires of burning villages and fields were clearly visible from Allied ships standing offshore. A British landing party reported that the population of Messinia was close to mass starvation. Ibrahim's scorched-earth policy caused much outrage in Europe, which was one factor for the Great Powers (United Kingdom, the Kingdom of France and the Russian Empire) decisively intervening against him in the Battle of Navarino.American Civil War

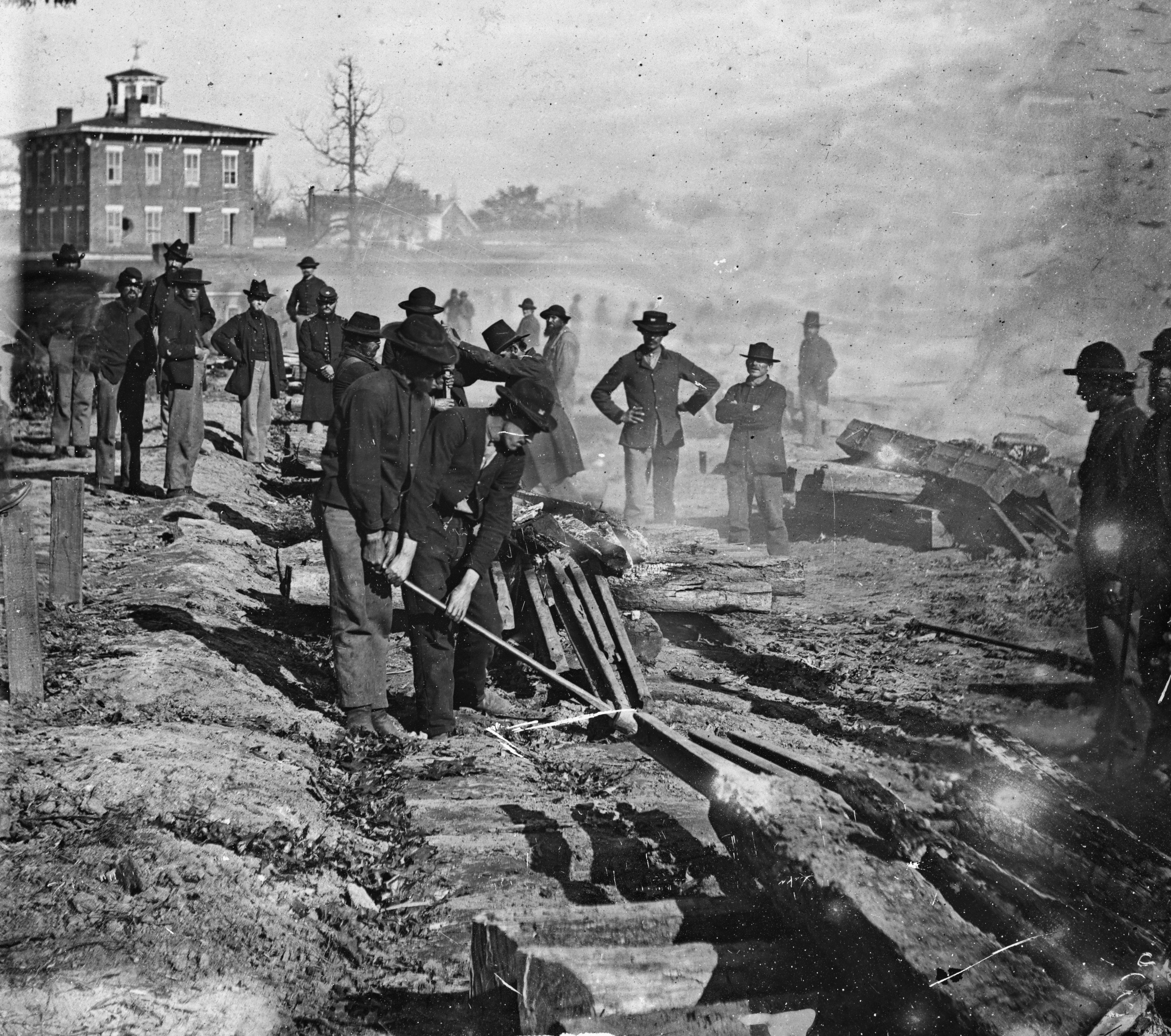

In the American Civil War, Union forces under Philip Sheridan and William Tecumseh Sherman used the policy widely:

General Sherman used that policy during his Sherman's March to the Sea, March to the Sea.

Another event, in response to William Quantrill's Lawrence massacre, raid on Lawrence, Kansas, and the many civilian casualties, including the killing of 150 men, Brigadier General Thomas Ewing Jr., Sherman's brother-in-law, issued US Army General Order No. 11 (1863) to order the near-total evacuation of three-and-a-half counties in western Missouri, south of Kansas City, which were subsequently looted and burned by US Army troops. Under Sherman's overall direction, General Philip Sheridan followed that policy in the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia and then in the American Indian Wars, Indian Wars of the Great Plains.

In the American Civil War, Union forces under Philip Sheridan and William Tecumseh Sherman used the policy widely:

General Sherman used that policy during his Sherman's March to the Sea, March to the Sea.

Another event, in response to William Quantrill's Lawrence massacre, raid on Lawrence, Kansas, and the many civilian casualties, including the killing of 150 men, Brigadier General Thomas Ewing Jr., Sherman's brother-in-law, issued US Army General Order No. 11 (1863) to order the near-total evacuation of three-and-a-half counties in western Missouri, south of Kansas City, which were subsequently looted and burned by US Army troops. Under Sherman's overall direction, General Philip Sheridan followed that policy in the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia and then in the American Indian Wars, Indian Wars of the Great Plains.

When General Ulysses S. Grant, Ulysses Grant's forces broke through the defenses of Richmond, Virginia, Confederate President Jefferson Davis ordered the destruction of Richmond's military supplies. The resulting fires quickly spread to other buildings, as well as to the Confederate warships docked on the James River. Civilians in panic were forced to escape the city as it quickly burned.

When General Ulysses S. Grant, Ulysses Grant's forces broke through the defenses of Richmond, Virginia, Confederate President Jefferson Davis ordered the destruction of Richmond's military supplies. The resulting fires quickly spread to other buildings, as well as to the Confederate warships docked on the James River. Civilians in panic were forced to escape the city as it quickly burned.

Native American Wars

During the wars with Native Americans in the United States, Native American tribes of the American West,

During the wars with Native Americans in the United States, Native American tribes of the American West, Second Boer War

During the Second Boer War (1899–1902), British forces applied a scorched-earth policy in the occupied Boer republics under the direction of General Horatio Kitchener, 1st Earl Kitchener, Lord Kitchener. Numerous Boers, refusing to accept military defeat, adopted guerrilla warfare despite the capture of both of their capital cities. As a result, under Lord Kitchener's command British forces initiated a policy of the destruction of the farms and the homes of civilians in the republics to prevent the Boers who were still fighting from obtaining food and supplies. Boer noncombatants inhabiting the republics (mostly women and children) were interned in Second Boer War concentration camps, concentration camps to prevent them from supplying guerillas still in the field.

The existence of the concentration camps was exposed by English activist Emily Hobhouse, who toured the camps and began petitioning the Government of the United Kingdom, British government to change its policy. In an attempt to counter Hobhouse's activism, the British government commissioned the Fawcett Commission, but it confirmed Hobhouse's findings. The British government then claimed that it perceived the concentration camps to be humanitarian measure and were established to care for displaced noncombatants until the war's end, in response to mounting criticism of the camps in Britain. A number of factors, including outbreaks of infectious diseases, a lack of planning and supplies for the camps, and overcrowding led to numerous internees dying in the camps. A decade after the war, historian P. L. A. Goldman estimated that 27,927 Boers died in the concentration camps, 26,251 women and children (of whom more than 22,000 were under the age of 16) and 1,676 men, with 1,421 being above the age of 16.

The number of Black Africans who also suffered the same is unknown.

During the Second Boer War (1899–1902), British forces applied a scorched-earth policy in the occupied Boer republics under the direction of General Horatio Kitchener, 1st Earl Kitchener, Lord Kitchener. Numerous Boers, refusing to accept military defeat, adopted guerrilla warfare despite the capture of both of their capital cities. As a result, under Lord Kitchener's command British forces initiated a policy of the destruction of the farms and the homes of civilians in the republics to prevent the Boers who were still fighting from obtaining food and supplies. Boer noncombatants inhabiting the republics (mostly women and children) were interned in Second Boer War concentration camps, concentration camps to prevent them from supplying guerillas still in the field.

The existence of the concentration camps was exposed by English activist Emily Hobhouse, who toured the camps and began petitioning the Government of the United Kingdom, British government to change its policy. In an attempt to counter Hobhouse's activism, the British government commissioned the Fawcett Commission, but it confirmed Hobhouse's findings. The British government then claimed that it perceived the concentration camps to be humanitarian measure and were established to care for displaced noncombatants until the war's end, in response to mounting criticism of the camps in Britain. A number of factors, including outbreaks of infectious diseases, a lack of planning and supplies for the camps, and overcrowding led to numerous internees dying in the camps. A decade after the war, historian P. L. A. Goldman estimated that 27,927 Boers died in the concentration camps, 26,251 women and children (of whom more than 22,000 were under the age of 16) and 1,676 men, with 1,421 being above the age of 16.

The number of Black Africans who also suffered the same is unknown.

New Zealand Wars

In 1868, the Tūhoe, who had sheltered the Māori people, Māori leader Te Kooti, were thus subjected to a scorched-earth policy in which their crops and buildings were destroyed and the people of fighting age were captured.20th century

World War I

On the Eastern Front (World War I), Eastern Front of World War I, the Imperial Russian Army created a zone of destruction by using a massive scorched-earth strategy during their retreat from the Imperial German army, Imperial German Army in the summer and the autumn of 1915. The Russian troops, retreating along a front of more than 600 miles, destroyed anything that might be of use to their enemy, including crops, houses, railways and entire cities. They also forcibly removed huge numbers of people. In pushing the Russian troops back into Russia's interior, the German army gained a large area of territory from the Russian Empire that is now Poland, Ukraine, Belarus, Latvia and Lithuania. In late 1916 the British army set fire to the Romania in World War I, Romanian oil fields in order to prevent the Central Powers from capturing them. 800 million litres of oil were burned. On the Western Front (World War I), Western Front on 24 February 1917, the German Army (German Empire), German army made a strategic scorched-earth withdrawal (Operation Alberich) from the Battle of the Somme, Somme battlefield to the prepared fortifications of the Hindenburg Line to shorten the line that had to be occupied. Since a scorched-earth campaign requires a maneuver warfare, war of movement, the Western Front of World War I, Western Front provided little opportunity for the policy as the war was mostly a stalemate and was fought mostly in the same concentrated area for its entire duration.Greco-Turkish War

During the Greco-Turkish War (1919–1922), the retreating Hellenic Army, Greek Army carried out a scorched-earth policy while it was fleeing from Anatolia in the final phase of the war. The historian Sydney Nettleton Fisher wrote, "The Greek army in retreat pursued a burned-earth policy and committed every known outrage against defenceless Turkish villagers in its path".

Norman Naimark noted that "the Greek retreat was even more devastating for the local population than the occupation".

During the Greco-Turkish War (1919–1922), the retreating Hellenic Army, Greek Army carried out a scorched-earth policy while it was fleeing from Anatolia in the final phase of the war. The historian Sydney Nettleton Fisher wrote, "The Greek army in retreat pursued a burned-earth policy and committed every known outrage against defenceless Turkish villagers in its path".

Norman Naimark noted that "the Greek retreat was even more devastating for the local population than the occupation".

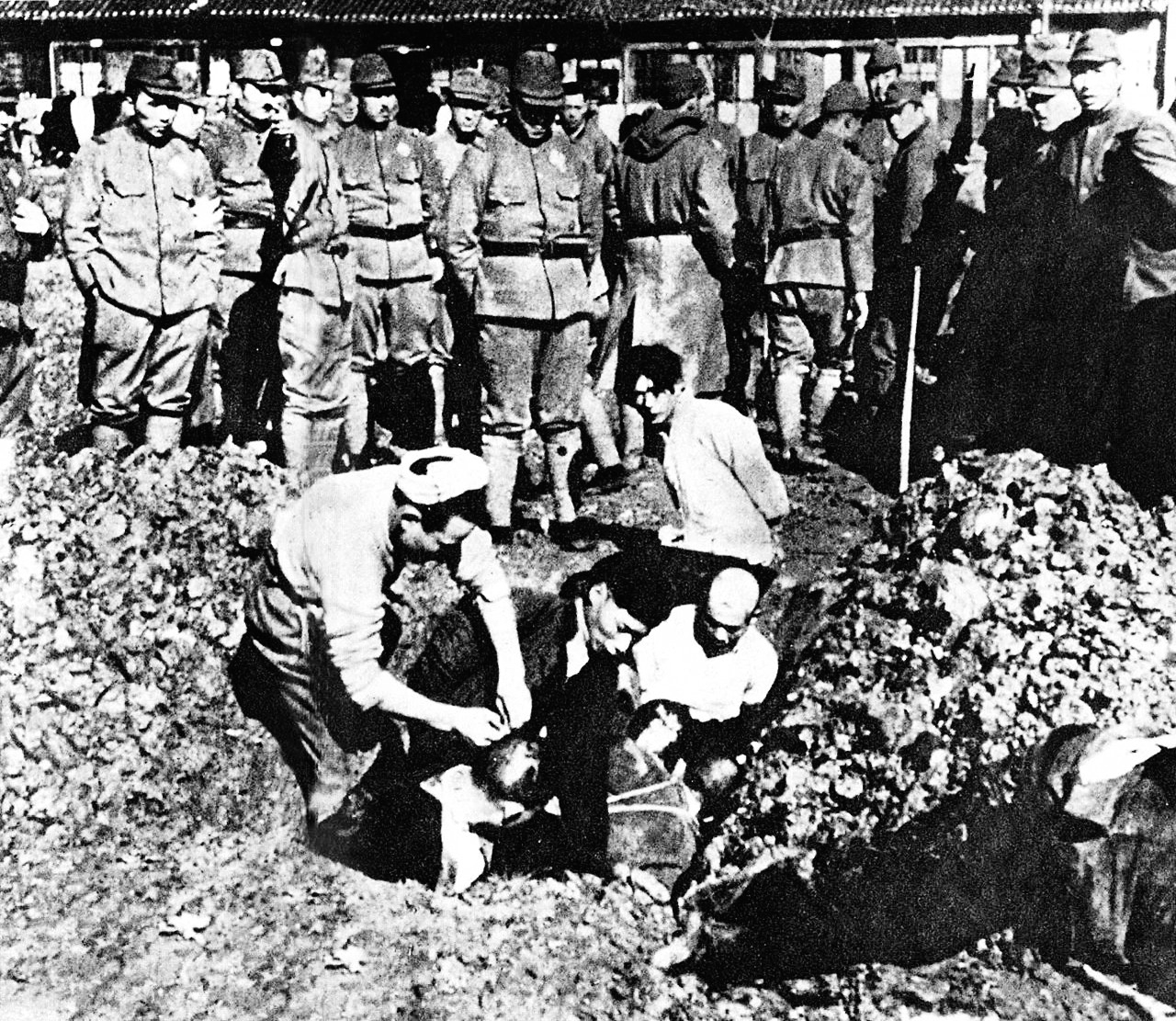

Second Sino-Japanese War

During the

During the World War II

At the start of the Winter War in 1939, the Finns used the tactic in the vicinity of the border in order to deprive the invading Soviet Red Army's provisions and shelter for the forthcoming cold winter. In some cases, fighting took place in areas that were familiar to the Finnish soldiers who were fighting it. There were accounts of soldiers burning down their very own homes and parishes. One of the burned parishes was Battle of Suomussalmi, Suomussalmi. When Operation Barbarossa, Germany attacked the Soviet Union in June 1941, many district governments took the initiative to begin a partial scorched-earth policy to deny the invaders access to electrical, telecommunications, rail, and industrial resources. Parts of the telegraph network were destroyed, some rail and road bridges were blown up, most electrical generators were sabotaged through the removal of key components, and many mineshafts were collapsed. The process was repeated later in the war by the German forces of Army Group North and Erich von Manstein's Army Group Don, which stole crops, destroyed farms, and razed cities and smaller settlements during several military operations. The rationale for the policy was that it would slow pursuing Soviet forces by forcing them to save their own civilians. The best-known victims of the German scorched-earth policy were the people of the historic city of Novgorod, which was razed during the winter of 1944 to cover Army Group North's retreat from Leningrad. Near the end of the summer of 1944, Finland, which had made a separate peace with the Allies of World War II, Allies, was required to evict the German forces, which had been fighting against the Soviets alongside Finnish troops in northern Finland. The Finnish forces, under the leadership of General Hjalmar Siilasvuo, struck aggressively in late September 1944 by making a landfall at Tornio. That accelerated the German retreat, and by November 1944, the Germans had left most of northern Finland. The German forces, forced to retreat because of an overall strategic situation, covered their retreat towards Norway by devastating large areas of northern Finland by using a scorched-earth strategy. More than a third of the area's dwellings were destroyed, and the provincial capital Battle of Rovaniemi, Rovaniemi was burned to the ground. All but two bridges in Lapland (Finland), Lapland Province were blown up, and all roads were mined. In northern Norway, which was also being invaded by Soviet forces in pursuit of the retreating Wehrmacht in 1944, the Germans also undertook a scorched-earth policy of destroying every building that could offer shelter and thus interposing a belt of "scorched earth" between themselves and the allies. In 1945, Adolf Hitler ordered his minister of armaments, Albert Speer, to carry out a nationwide scorched-earth policy, in what became known as the Nero Decree. Speer, who was looking to the future, actively resisted the order, just as he had earlier refused Hitler's command to destroy French industry when the Wehrmacht was being driven out of France. Speer managed to continue doing so even after Hitler became aware of his actions. During the Second World War, the railroad plough was used during retreats in Nazi Germany, Germany, Czechoslovakia and other countries to deny enemy use of railways by partially destroying them.Malayan Liberation War

Britain was the first nation to employ herbicides and defoliants (chiefly Agent Orange) to destroy the crops and the bushes of Malayan National Liberation Army (MNLA) insurgents in Malay Peninsula, Malaya during the Malayan Emergency. The intent was to prevent MNLA insurgents from utilizing rice fields to resupply their rations and using them as a cover to ambush passing convoys of Commonwealth troops.Goa War

In response to India's invasion of Portuguese Goa in December 1961 during the annexation of Portuguese India, orders delivered from President of Portugal, Portuguese President Américo Tomás called for a scorched-earth policy for Goa to be destroyed before its surrender to India. However, despite his orders from Lisbon, Governor General Manuel António Vassalo e Silva took stock of the superiority of the Indian troops and of his forces' supplies of food and ammunition and took the decision to surrender. He later described his orders to destroy Goa as "a useless sacrifice" (''um sacrifício inútil'')".Vietnam War

The United States used Agent Orange as a part of its herbicidal warfare program Operation Ranch Hand to destroy crops and foliage to expose possible enemy hideouts during the Vietnam War. Agent Blue was used on rice fields to deny food to the Viet Cong.Guatemalan Civil War

Efraín Ríos Montt used the policy in Guatemala's highlands in 1981 and 1982, but it had been used under the previous president, Fernando Romeo Lucas García. Upon entering office, Ríos Montt implemented a new counterinsurgency strategy that called for the use of scorched earth to combat the Guatemalan National Revolutionary Unity rebels. Plan Victoria 82 was more commonly known by the nickname of the rural pacification elements of the strategy, ''Fusiles y Frijoles'' (Bullets and Beans). Ríos Montt's policies resulted in the death of thousands, most of them indigenous Maya peoples, Mayans.Indonesia

The Indonesian National Armed Forces, Indonesian military used the method during Indonesian National Revolution when the British forces in Bandung gave an ultimatum for Indonesian fighters to leave the city. In response, the southern part of Bandung was deliberately burned down in an act of defiance as they left the city on 24 March 1946. This event is known as the Bandung Sea of Fire (''Bandung Lautan Api'').

The Indonesian military and pro-Indonesia militias also used the method in the 1999 East Timorese crisis. The Timor-Leste scorched-earth campaign was around the time of East Timor's referendum for independence in 1999.

The Indonesian National Armed Forces, Indonesian military used the method during Indonesian National Revolution when the British forces in Bandung gave an ultimatum for Indonesian fighters to leave the city. In response, the southern part of Bandung was deliberately burned down in an act of defiance as they left the city on 24 March 1946. This event is known as the Bandung Sea of Fire (''Bandung Lautan Api'').

The Indonesian military and pro-Indonesia militias also used the method in the 1999 East Timorese crisis. The Timor-Leste scorched-earth campaign was around the time of East Timor's referendum for independence in 1999.

Yugoslav Wars

The method was used during the Yugoslav Wars that started in 1991, such as against the Serbs in Republic of Serbian Krajina, Krajina by the Croatian Army, and by List of Serbian paramilitary formations#Yugoslav Wars, Serbian paramilitary groups.Soviet–Afghan War

The Soviet army used scorched-earth tactics against towns and villages in 1983 to 1984 in the Soviet–Afghan War to prevent the return of the Mujahideen by a migratory genocide. The Soviet army used mines extensively in the bordering provinces to Pakistan to cut off weapon supply.21st century

Sri Lankan Civil War

During the 2009 Sri Lankan civil war, Sri Lankan Civil War, the United Nations Regional Information Centre accused the government of Sri Lanka of using scorched-earth tactics.Myanmar civil war

In March 2023, the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights condemned the Tatmadaw, Burmese military's use of a scorched earth strategy, which has killed thousands of civilians, displaced 1.3 million people and destroyed 39,000 houses throughout the country since the 2021 Myanmar coup d'état, as the military has denied humanitarian access to survivors, razed entire villages, and used indiscriminate airstrikes and artillery shelling.In business world

The concept of scorched-earth defense is sometimes applied figuratively to the business world in which a firm facing a takeover attempts to make itself less valuable by selling off its assets.See also

* Area bombing ** Aerial bombing of cities * Area denial * ''Bellum se ipsum alet'', the strategy of relying on occupied territories for resources * ''Burmah Oil Co. v Lord Advocate'' * Carthaginian peace * Chevauchée * Countervalue * Early thermal weapons * Ecocide * Environmental impact of war * Fabian strategy *Explanatory notes

Notes

References

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Scorched Earth Scorched earth operations, Economic warfare tactics Environmental impact of war Military withdrawals Military terminology 1937 neologisms Fires