Sarajevo During The Middle Ages on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Following the

Following the

By late winter of 1878, it became clear that Ottoman authority in the area was weakened. The

By late winter of 1878, it became clear that Ottoman authority in the area was weakened. The

At the Berlin Treaty negotiations, the Austro-Hungarian side was represented by the k. und k. foreign minister, count

At the Berlin Treaty negotiations, the Austro-Hungarian side was represented by the k. und k. foreign minister, count

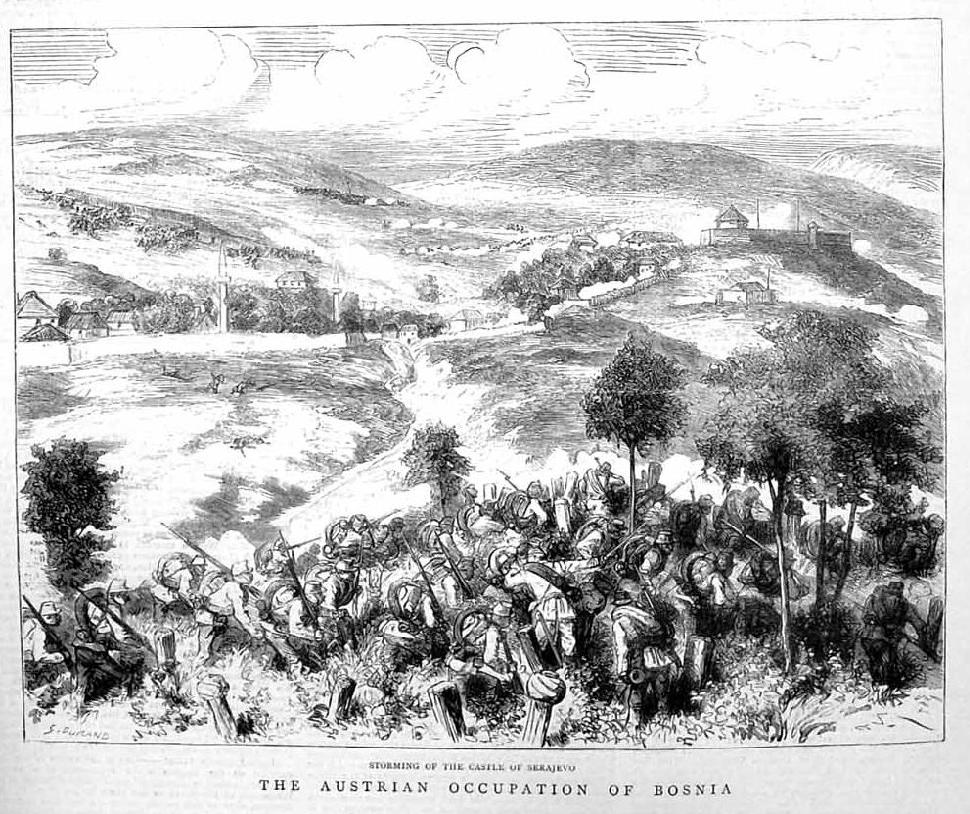

On the morning of Monday, 19 August around 6:30am, the Austro-Hungarian Army began its artillery bombardment of Sarajevo using 52 cannons with feldzeugmeister Filipović committing a sizable portion of the total 14,000 troops under his command for this actionMustaj-beg Fadilpašić, prvi gradonačelnik Sarajeva

On the morning of Monday, 19 August around 6:30am, the Austro-Hungarian Army began its artillery bombardment of Sarajevo using 52 cannons with feldzeugmeister Filipović committing a sizable portion of the total 14,000 troops under his command for this actionMustaj-beg Fadilpašić, prvi gradonačelnik Sarajeva

;radiosarajevo.ba, 20 October 2012Uz proslavu 550 godina Sarajeva

portal.skola.ba, 17 May 2012 to the hills surrounding the city. Then, the infantry came into the city from the western direction of

Unexpectedly aided by a fire that burned down a large part of the central city area (čaršija), architects and engineers who desired to modernize Sarajevo rushed to the city. The result was a unique blend of the remaining Ottoman city market and contemporary Western architecture. For the first time in centuries, the city significantly expanded outside its traditional borders. Much of the city's contemporary central municipality (Centar Municipality, Sarajevo, Centar) was constructed during this period.

Architecture in Sarajevo quickly developed into a wide range of styles and buildings. The Sacred Heart Cathedral, Sarajevo, Cathedral of Sacred Heart, for example, was constructed using elements of neo-Gothic and Romanesque architecture. The National Museum, Sarajevo brewery, and City Hall were also constructed during this period.

Unexpectedly aided by a fire that burned down a large part of the central city area (čaršija), architects and engineers who desired to modernize Sarajevo rushed to the city. The result was a unique blend of the remaining Ottoman city market and contemporary Western architecture. For the first time in centuries, the city significantly expanded outside its traditional borders. Much of the city's contemporary central municipality (Centar Municipality, Sarajevo, Centar) was constructed during this period.

Architecture in Sarajevo quickly developed into a wide range of styles and buildings. The Sacred Heart Cathedral, Sarajevo, Cathedral of Sacred Heart, for example, was constructed using elements of neo-Gothic and Romanesque architecture. The National Museum, Sarajevo brewery, and City Hall were also constructed during this period.

Sarajevo

Sarajevo ( ), ; ''see Names of European cities in different languages (Q–T)#S, names in other languages'' is the Capital city, capital and List of cities in Bosnia and Herzegovina, largest city of Bosnia and Herzegovina, with a population of 2 ...

is a city now in Bosnia and Herzegovina

Bosnia and Herzegovina, sometimes known as Bosnia-Herzegovina and informally as Bosnia, is a country in Southeast Europe. Situated on the Balkans, Balkan Peninsula, it borders Serbia to the east, Montenegro to the southeast, and Croatia to th ...

.

Ancient history

The earliest known settlements in Sarajevo were those of theNeolithic

The Neolithic or New Stone Age (from Ancient Greek, Greek 'new' and 'stone') is an archaeological period, the final division of the Stone Age in Mesopotamia, Asia, Europe and Africa (c. 10,000 BCE to c. 2,000 BCE). It saw the Neolithic Revo ...

Butmir culture

The Butmir culture was a major Neolithic culture in central Bosnia, developed along the shores of the river Bosna, spanning from Sarajevo to Zavidovići. It was discovered in 1893, at the site located in Butmir, in the vicinity of Ilidža, w ...

. The discoveries at Butmir

Butmir ( sr-cyrl, Бутмир) is a neighborhood in the municipality of Ilidža, Bosnia and Herzegovina. Sarajevo International Airport, the main airport of Bosnia and Herzegovina is located in Butmir.

Geography

The Butmir region is very rich in ...

were made in modern-day Ilidža

Ilidža ( sr-cyrl, Илиџа, ) is a spa town and a municipality located in Sarajevo Canton of the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, an entity of Bosnia and Herzegovina. It has a total population of 66,730 with 63,528 in Ilidža itself, and i ...

, Sarajevo's chief suburb. The area's richness in flint

Flint, occasionally flintstone, is a sedimentary cryptocrystalline form of the mineral quartz, categorized as the variety of chert that occurs in chalk or marly limestone. Historically, flint was widely used to make stone tools and start ...

, as well as the Željeznica river helped the settlement flourish. The Butmir culture is most famous for its ceramics

A ceramic is any of the various hard, brittle, heat-resistant, and corrosion-resistant materials made by shaping and then firing an inorganic, nonmetallic material, such as clay, at a high temperature. Common examples are earthenware, porce ...

.

The Butmir culture was conquered by the Illyrians

The Illyrians (, ; ) were a group of Indo-European languages, Indo-European-speaking people who inhabited the western Balkan Peninsula in ancient times. They constituted one of the three main Paleo-Balkan languages, Paleo-Balkan populations, alon ...

around 2400 BC. The most prominent of their settlements near Sarajevo was ''Debelo Brdo'' (literally "Fat Hill"), where an Illyrian fortification stood during the late Iron Age

The Iron Age () is the final epoch of the three historical Metal Ages, after the Chalcolithic and Bronze Age. It has also been considered as the final age of the three-age division starting with prehistory (before recorded history) and progre ...

. Numerous Illyrian forts also existed in other parts of the city, as well as at the base of Trebević

Trebević ( sr-cyrl, Требевић) is a mountain in central Bosnia and Herzegovina, located in the territories of Republika Srpska, Sarajevo and Istočno Sarajevo, bordering Jahorina mountain. Trebević is tall, making it the second shortest ...

. The Illyrians in the Sarajevo region were the Daesitiates

Daesitiates were an Illyrian tribe that lived on the territory of today's central Bosnia, during the time of the Roman Republic. Along with the Maezaei, the Daesitiates were part of the western group of Pannonians in Roman Dalmatia. They were ...

, who were the last to resist Roman

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of Roman civilization

*Epistle to the Romans, shortened to Romans, a letter w ...

occupation. Their last revolt occurred in 9 AD, and was stopped by the emperor Tiberius

Tiberius Julius Caesar Augustus ( ; 16 November 42 BC – 16 March AD 37) was Roman emperor from AD 14 until 37. He succeeded his stepfather Augustus, the first Roman emperor. Tiberius was born in Rome in 42 BC to Roman politician Tiberius Cl ...

, marking the start of Roman rule in the region.

Under Roman rule, Sarajevo was part of the province of Dalmatia. A major Roman road

Roman roads ( ; singular: ; meaning "Roman way") were physical infrastructure vital to the maintenance and development of the Roman state, built from about 300 BC through the expansion and consolidation of the Roman Republic and the Roman Em ...

ran through the Miljacka

The Miljacka ( sr-Cyrl, Миљацка) is a river in Bosnia and Herzegovina that passes through Sarajevo. Numerous city bridges have been built to cross it.

Characteristics

The Miljacka river originates from the confluence of the Paljanska Mi ...

river valley, connecting the cities of the Adriatic

The Adriatic Sea () is a body of water separating the Italian Peninsula from the Balkans, Balkan Peninsula. The Adriatic is the northernmost arm of the Mediterranean Sea, extending from the Strait of Otranto (where it connects to the Ionian Se ...

coast with Pannonia

Pannonia (, ) was a Roman province, province of the Roman Empire bounded on the north and east by the Danube, on the west by Noricum and upper Roman Italy, Italy, and on the southward by Dalmatia (Roman province), Dalmatia and upper Moesia. It ...

in the north. The largest known settlement in the region was known as "Aquae S..." (probably Aquae Sulphurae), at present-day Ilidža

Ilidža ( sr-cyrl, Илиџа, ) is a spa town and a municipality located in Sarajevo Canton of the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, an entity of Bosnia and Herzegovina. It has a total population of 66,730 with 63,528 in Ilidža itself, and i ...

.

Middle Ages

TheSlavs

The Slavs or Slavic people are groups of people who speak Slavic languages. Slavs are geographically distributed throughout the northern parts of Eurasia; they predominantly inhabit Central Europe, Eastern Europe, Southeastern Europe, and ...

came to Bosnia in the 7th century. It is fairly certain that they settled in the Sarajevo valley, replacing the Illyrians. Katera, one of the two Bosnian towns mentioned as a part of Serbia by Constantine Porphyrogenitus

Constantine VII Porphyrogenitus (; 17 May 905 – 9 November 959) was the fourth Byzantine emperor of the Macedonian dynasty, reigning from 6 June 913 to 9 November 959. He was the son of Emperor Leo VI and his fourth wife, Zoe Karbonopsina, an ...

in ''De Administrando Imperio

(; ) is a Greek-language work written by the 10th-century Byzantine Emperor Constantine VII. It is a domestic and foreign policy manual for the use of Constantine's son and successor, the Emperor Romanos II. It is a prominent example of Byz ...

'', was southeast of Sarajevo. By the time of the Ottoman occupation in the 15th century, there was little settlement in the region.

The first mentions of Bosnia describe a small region, basically the Bosna river valley, stretching from modern-day Zenica

Zenica ( ; ) is a city in Bosnia and Herzegovina and an administrative and economic center of the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina's Zenica-Doboj Canton. It is located in the Bosna (river), Bosna river valley, about north of Sarajevo. The ...

to Sarajevo. In the 12th century, when Bosnia became a vassal

A vassal or liege subject is a person regarded as having a mutual obligation to a lord or monarch, in the context of the feudal system in medieval Europe. While the subordinate party is called a vassal, the dominant party is called a suzerain ...

of Hungary

Hungary is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning much of the Pannonian Basin, Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the south, Croatia and ...

, the population consisted primarily of members of the Bosnian Church

The Bosnian Church ( sh-Latn-Cyrl, separator=/, Crkva bosanska, Црква босанска) was an autonomous Christian church in medieval Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Historians traditionally connected the church with the Bogomils, although this ...

. The area of present-day Sarajevo was part of the Bosnian province of Vrhbosna

Vrhbosna ( sr-cyrl, Врхбосна, ) was the medieval name of a small region in today's central Bosnia and Herzegovina, centered on an eponymous settlement (župa) that would later become part of the city of Sarajevo.

The meaning of the name ...

. Another theory is that Vrhbosna was a major settlement located in the middle of modern-day Sarajevo. Perhaps a village existed on the outskirts of the city itself, near present-day Ilidža

Ilidža ( sr-cyrl, Илиџа, ) is a spa town and a municipality located in Sarajevo Canton of the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, an entity of Bosnia and Herzegovina. It has a total population of 66,730 with 63,528 in Ilidža itself, and i ...

, one of the most attractive regions in the area, which had been significantly populated for about every other period of its history. It is possible that Vrhbosna may have been destroyed sometime between the 13th century and the Ottoman occupation. Foreign armies had often made their way to Vrhbosna in wars with Bosnia, and perhaps one of them razed the city, leaving it in the condition that the Turks found it in the mid-15th century. Papal

The pope is the bishop of Rome and the visible head of the worldwide Catholic Church. He is also known as the supreme pontiff, Roman pontiff, or sovereign pontiff. From the 8th century until 1870, the pope was the sovereign or head of sta ...

documents indicate that in 1238, a cathedral dedicated to Saint Paul

Paul, also named Saul of Tarsus, commonly known as Paul the Apostle and Saint Paul, was a Christian apostle ( AD) who spread the teachings of Jesus in the first-century world. For his contributions towards the New Testament, he is generally ...

was built in the city. It is speculated that the cathedral was located in the present-day Sarajevo neighborhood of Skenderija, as during construction in that neighborhood in the late 19th century, Roman-style columns were found dating to some time around the 12th century. Disciples of the saints Cyril and Methodius

Cyril (; born Constantine, 826–869) and Methodius (; born Michael, 815–885) were brothers, Byzantine Christian theologians and missionaries. For their work evangelizing the Slavs, they are known as the "Apostles to the Slavs".

They are ...

traveled to the region, founding a church near Vrelo Bosne

Vrelo Bosne (; ) is a public park and a protected Nature Monument established around the source of the Bosna river, featuring the system of numerous springs at the foothills of Mount Igman, in the municipality of Ilidža, on the outskirts of Sa ...

. Vrhbosna was a Slavic citadel from 1263 until it was occupied by the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

in 1429.

Various documents from the High Middle Ages

The High Middle Ages, or High Medieval Period, was the periodization, period of European history between and ; it was preceded by the Early Middle Ages and followed by the Late Middle Ages, which ended according to historiographical convention ...

reference a place called 'Tornik' in the region. By all indications, 'Tornik' was a very small marketplace and village, and was not considered important by Ragusan merchants. The local fortress of Hodidjed was defended by a mere two dozen men when it fell to the Turks. Sarajevo also fell under siege.

Early Ottoman era

Sarajevo was founded when theOttoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

conquered the region, with 1461 typically regarded as the date of the city's founding. The first known Ottoman governor of Bosnia, Isa-Beg Ishaković, chose the village of Brodac as a good space for a new city. He exchanged land with its residents, giving them what is now the Hrasnica neighborhood in Ilidža

Ilidža ( sr-cyrl, Илиџа, ) is a spa town and a municipality located in Sarajevo Canton of the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, an entity of Bosnia and Herzegovina. It has a total population of 66,730 with 63,528 in Ilidža itself, and i ...

. He built a number of buildings, including a mosque

A mosque ( ), also called a masjid ( ), is a place of worship for Muslims. The term usually refers to a covered building, but can be any place where Salah, Islamic prayers are performed; such as an outdoor courtyard.

Originally, mosques were si ...

, a closed marketplace, a public bath, a bridge, a hostel, and the saray which gave the city its present name. The mosque

A mosque ( ), also called a masjid ( ), is a place of worship for Muslims. The term usually refers to a covered building, but can be any place where Salah, Islamic prayers are performed; such as an outdoor courtyard.

Originally, mosques were si ...

was named " Careva džamija" (the Emperor's Mosque, or the Imperial Mosque) in honor of Mehmed II

Mehmed II (; , ; 30 March 14323 May 1481), commonly known as Mehmed the Conqueror (; ), was twice the sultan of the Ottoman Empire from August 1444 to September 1446 and then later from February 1451 to May 1481.

In Mehmed II's first reign, ...

. Sarajevo quickly grew into the largest city in the region. Many Christians

A Christian () is a person who follows or adheres to Christianity, a monotheistic Abrahamic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus Christ. Christians form the largest religious community in the world. The words '' Christ'' and ''C ...

converted to Islam

Islam is an Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the Quran, and the teachings of Muhammad. Adherents of Islam are called Muslims, who are estimated to number Islam by country, 2 billion worldwide and are the world ...

at this time, and there was a growing Orthodox population. A colony of Ragusan merchants also appeared in Sarajevo at this time. In the early 16th century, Jewish

Jews (, , ), or the Jewish people, are an ethnoreligious group and nation, originating from the Israelites of History of ancient Israel and Judah, ancient Israel and Judah. They also traditionally adhere to Judaism. Jewish ethnicity, rel ...

refugees from Andalusia

Andalusia ( , ; , ) is the southernmost autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community in Peninsular Spain, located in the south of the Iberian Peninsula, in southwestern Europe. It is the most populous and the second-largest autonomou ...

brought the Sarajevo Haggadah.

Under the leadership of Gazi Husrev-beg

Gazi Husrev Bey (, ''Gāzī Ḫusrev Beğ''; Modern Turkish: ''Gazi Hüsrev Bey''; ; 1484–1541) was an Ottoman Bosnian sanjak-bey (governor) of the Sanjak of Bosnia in 1521–1525, 1526–1534, and 1536–1541. He was known for his succes ...

, a major donor who was responsible for most of what is now the Old Town, Sarajevo grew at a rapid rate. Sarajevo became known for its large marketplace and its mosques

A mosque ( ), also called a masjid ( ), is a place of worship for Muslims. The term usually refers to a covered building, but can be any place where Islamic prayers are performed; such as an outdoor courtyard.

Originally, mosques were simple p ...

, of which there were more than one hundred by the middle of the 16th century. Gazi Husrev-Beg established a number of buildings named in his honor, such as the Sarajevo library

A library is a collection of Book, books, and possibly other Document, materials and Media (communication), media, that is accessible for use by its members and members of allied institutions. Libraries provide physical (hard copies) or electron ...

. He also built the city's clock tower

Clock towers are a specific type of structure that house a turret clock and have one or more clock faces on the upper exterior walls. Many clock towers are freestanding structures but they can also adjoin or be located on top of another building ...

, the Sahat Kula.

At its height, Sarajevo was the largest and most important Ottoman city in the Balkans

The Balkans ( , ), corresponding partially with the Balkan Peninsula, is a geographical area in southeastern Europe with various geographical and historical definitions. The region takes its name from the Balkan Mountains that stretch throug ...

after Istanbul

Istanbul is the List of largest cities and towns in Turkey, largest city in Turkey, constituting the country's economic, cultural, and historical heart. With Demographics of Istanbul, a population over , it is home to 18% of the Demographics ...

. By 1660, the population of Sarajevo was estimated to be over 80,000.

Late Ottoman era

Following the

Following the Battle of Vienna

The Battle of Vienna took place at Kahlenberg Mountain near Vienna on 1683 after the city had been besieged by the Ottoman Empire for two months. The battle was fought by the Holy Roman Empire (led by the Habsburg monarchy) and the Polish–Li ...

in 1683, the western portion of the Ottoman Empire was subject to raids. Prince Eugene of Savoy

Prince Eugene Francis of Savoy-Carignano (18 October 1663 – 21 April 1736), better known as Prince Eugene, was a distinguished Generalfeldmarschall, field marshal in the Army of the Holy Roman Empire and of the Austrian Habsburg dynasty durin ...

raided Sarajevo and torched it.

An important chronicler of the time was Mula Mustafa Bašeskija who wrote about Sarajevo. Significant libraries, schools, mosques, and fortifications were built during the late Ottoman era. Mustafa wrote about the tensions between the dervish

Dervish, Darvesh, or Darwīsh (from ) in Islam can refer broadly to members of a Sufi fraternity (''tariqah''), or more narrowly to a religious mendicant, who chose or accepted material poverty. The latter usage is found particularly in Persi ...

and Kadizadeli, the latter being a significant influence on the city.

In 1762, a plague epidemic

An epidemic (from Greek ἐπί ''epi'' "upon or above" and δῆμος ''demos'' "people") is the rapid spread of disease to a large number of hosts in a given population within a short period of time. For example, in meningococcal infection ...

hit the city, taking about 15,000 lives. At the time, city's population numbered some 20,000. In 1783, there was another outbreak; some 8,000 people died. Fires and floods were also common. The overflowing Miljacka

The Miljacka ( sr-Cyrl, Миљацка) is a river in Bosnia and Herzegovina that passes through Sarajevo. Numerous city bridges have been built to cross it.

Characteristics

The Miljacka river originates from the confluence of the Paljanska Mi ...

threatened the city's bazaar. A major flood occurred in 1783 and another in 1791. The largest fire occurred in 1788.

By the early 19th century, Serbia gained independence from the Ottoman Empire, creating a wedge between Sarajevo and Istanbul.

Demanding Bosnian independence from the Turks, Husein-Kapetan Gradaščević fought several battles around Bosnia. The last was the Battle of Sarajevo Field in 1832, where he was betrayed by a fellow Bosniak and lost. There, he spoke his famous words, "This is the last day of our freedom." For the next several decades, no major developments occurred.

Austria-Hungary

Background

The Berlin Treaty was imposed by theGreat Powers

A great power is a sovereign state that is recognized as having the ability and expertise to exert its influence on a global scale. Great powers characteristically possess military and economic strength, as well as diplomatic and soft power ...

upon the rapidly dissolving Ottoman Empire, which entered the negotiations from a position of weakness, with many of its former territories having achieved ''de facto'' independence over the previous half-century and having just been defeated in the Russo-Turkish War

The Russo-Turkish wars ( ), or the Russo-Ottoman wars (), began in 1568 and continued intermittently until 1918. They consisted of twelve conflicts in total, making them one of the longest series of wars in the history of Europe. All but four of ...

. Although the Bosnia Vilayet was part of the Ottoman Empire ''de jure

In law and government, ''de jure'' (; ; ) describes practices that are officially recognized by laws or other formal norms, regardless of whether the practice exists in reality. The phrase is often used in contrast with '' de facto'' ('from fa ...

'', it was '' de facto'' governed as an integral part of Austria-Hungary with the Ottomans having no say in its governance.

Eastern Crisis 1875–1878

Previously, the Ottoman position in the Bosnia Vilayet was weakened by the 1875–1877 Herzegovina uprising, an armed revolt by the local ethnic Serb population that began in the Herzegovina region in July 1875 before spreading to the rest of thevilayet

A vilayet (, "province"), also known by #Names, various other names, was a first-order administrative division of the later Ottoman Empire. It was introduced in the Vilayet Law of 21 January 1867, part of the Tanzimat reform movement initiated b ...

. The uprising lasted more than two years before the Ottomans, aided by the local Muslim population, managed to stop it. In 1875, inspired by the Herzegovina uprising, the exiled Bulgarian revolutionaries operating out of the neighbouring United Romanian Principalities (another ''de jure'' Ottoman vassal which was steadily moving towards independence) began planning for their own uprising which began in the spring of 1876. The Ottoman reaction to the Bulgarian insurrection was swift and brutal, leading to many atrocities and universal international condemnation as the uprising was put down within months.

Austria-Hungary closely followed the events of the 1875 Serb peasant rebellion in Bosnia. Shaped by the Austrian-Hungarian foreign minister

In many countries, the ministry of foreign affairs (abbreviated as MFA or MOFA) is the highest government department exclusively or primarily responsible for the state's foreign policy and relations, diplomacy, bilateral, and multilateral r ...

, Count Gyula Andrássy

Count Gyula Andrássy de Csíkszentkirály et Krasznahorka (, 8 March 1823 – 18 February 1890) was a Hungarian statesman, who served as Prime Minister of Hungary (1867–1871) and subsequently as List of foreign ministers of Austria-Hungar ...

, who was appointed in 1871 to replace Friedrich von Beust, the dual monarchy's foreign policy identified the Near East

The Near East () is a transcontinental region around the Eastern Mediterranean encompassing the historical Fertile Crescent, the Levant, Anatolia, Egypt, Mesopotamia, and coastal areas of the Arabian Peninsula. The term was invented in the 20th ...

as the area of particular interest for its next expansion. Andrássy saw an opportunity to move this policy forward, and on 30 December 1875 he sent a dispatch to his foreign ministry predecessor, Von Beust, who was the Austro-Hungarian Foreign Service's ambassador to the United Kingdom. In the document, known as the "Andrássy Note," Andrássy outlined his vision for Bosnia as a territory governed and administered by Austria-Hungary. After obtaining general assent from the UK and France, the document became official basis for negotiations.

Simultaneous with their defeats in the Russo-Turkish War

The Russo-Turkish wars ( ), or the Russo-Ottoman wars (), began in 1568 and continued intermittently until 1918. They consisted of twelve conflicts in total, making them one of the longest series of wars in the history of Europe. All but four of ...

, Ottoman rule in the Bosnia Vilayet was weakening. Logistical and organisational issues began arising in the Ottoman army

The Military of the Ottoman Empire () was the armed forces of the Ottoman Empire. It was founded in 1299 and dissolved in 1922.

Army

The Military of the Ottoman Empire can be divided in five main periods. The foundation era covers the years ...

, such as inability to feed and clothe its soldiers, including the nineteen garrison

A garrison is any body of troops stationed in a particular location, originally to guard it. The term now often applies to certain facilities that constitute a military base or fortified military headquarters.

A garrison is usually in a city ...

s stationed in the Bosnia Vilayet, seventeen of which were made up of local Bosnian Muslims. In a January 1878 report, the Austro-Hungarian consul stationed in the city of Sarajevo, Konrad von Wassitsch, noted to his Vienna superiors that "Ottoman administrative bodies have no authority, and the population has lost its confidence in the government." By spring of 1878, the Ottoman Army in the vilayet was in such a state of disarray that many troops deserted after being left to their own means. As a consequence, an estimated three thousand armed deserters were roaming the countryside in small bands, frequently terrorizing peasants. With no organized force implementing the law, groups of outlaws operated with impunity in many rural areas, effectively seizing control of significant territories.

Treaty of San Stefano

By late winter of 1878, it became clear that Ottoman authority in the area was weakened. The

By late winter of 1878, it became clear that Ottoman authority in the area was weakened. The Treaty of San Stefano

The 1878 Preliminary Treaty of San Stefano (; Peace of San-Stefano, ; Peace treaty of San-Stefano, or ) was a treaty between the Russian and Ottoman empires at the conclusion of the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–1878. It was signed at San Ste ...

, imposed on 3 March 1878 by Russia upon the defeated Ottomans, confirmed it. Among other provisions, it stipulated that there would be full independence from the Ottoman Empire for the principalities of Serbia

, image_flag = Flag of Serbia.svg

, national_motto =

, image_coat = Coat of arms of Serbia.svg

, national_anthem = ()

, image_map =

, map_caption = Location of Serbia (gree ...

and Montenegro

, image_flag = Flag of Montenegro.svg

, image_coat = Coat of arms of Montenegro.svg

, coa_size = 80

, national_motto =

, national_anthem = ()

, image_map = Europe-Mont ...

, ''de jure'' autonomy (''de facto'' independence) within the Ottoman Empire for the Principality of Bulgaria

The Principality of Bulgaria () was a vassal state under the suzerainty of the Ottoman Empire. It was established by the Treaty of Berlin in 1878.

After the Russo-Turkish War ended with a Russian victory, the Treaty of San Stefano was signed ...

, and autonomous province status for the Bosnian Vilayet within the Ottoman Empire.

The Muslim population of the Bosnia Vilayet welcomed the promised greater autonomy thus rekindling their autonomy aspirations. However, international reaction to the treaty was mostly negative. The Great Powers, especially British Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli

Benjamin Disraeli, 1st Earl of Beaconsfield (21 December 1804 – 19 April 1881) was a British statesman, Conservative Party (UK), Conservative politician and writer who twice served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom. He played a ...

, were unhappy with the extension of Russian power, while Austria-Hungary was also disappointed as the treaty failed to expand its influence in the Bosnia Vilayet. In a 21 April 1878 memorandum to the European powers, the Austro-Hungarian foreign minister Gyula Andrássy

Count Gyula Andrássy de Csíkszentkirály et Krasznahorka (, 8 March 1823 – 18 February 1890) was a Hungarian statesman, who served as Prime Minister of Hungary (1867–1871) and subsequently as List of foreign ministers of Austria-Hungar ...

proposed his Bosnia policy, making a case for a Habsburg occupation of Bosnia Vilayet. He argued that an autonomous Bosnia within the Ottoman Empire lacked the means to overcome internal divisions and maintain its existence against its neighbours. The United Kingdom supported Austria-Hungary's aspirations in Bosnia.

Many of the smaller nations also had objections to the San Stefano Treaty—although satisfied with receiving formal independence, Serbia was unhappy with the Bulgarian expansion, Romania was extremely disappointed as its public perceived some of the treaty stipulations as Russia breaking the Russo-Romanian pre-war agreements that guaranteed the country's territorial integrity, and the Albanians objected to what they considered a significant loss of their territory to Serbia, Bulgaria and Montenegro. Besides Bosnian Muslims, Bulgaria was the only nation happy with the treaty.

Local reaction to the prospect of Austro-Hungarian occupation

Because of its almost universal rejection by the global powers, the San Stefano Treaty was never implemented, and in the end only set the stage for a conference organized byGerman Empire

The German Empire (),; ; World Book, Inc. ''The World Book dictionary, Volume 1''. World Book, Inc., 2003. p. 572. States that Deutsches Reich translates as "German Realm" and was a former official name of Germany. also referred to as Imperia ...

chancellor Otto von Bismarck

Otto, Prince of Bismarck, Count of Bismarck-Schönhausen, Duke of Lauenburg (; born ''Otto Eduard Leopold von Bismarck''; 1 April 1815 – 30 July 1898) was a German statesman and diplomat who oversaw the unification of Germany and served as ...

three months later in Berlin. Uncertainty over San Stefano brought about rumours of imminent Austro-Hungarian occupation in Sarajevo as early as April 1878, well before the Berlin Congress, evoking different responses from the city's various ethnicities and classes.

Bosnian Croats

The Croats of Bosnia and Herzegovina (), often referred to as Bosnian Croats () or Herzegovinian Croats (), are native to Bosnia and Herzegovina and constitute the third most populous ethnic group, after Bosniaks and Serbs. They are also one of ...

welcomed the notion of being occupied by their Roman Catholic co-believers, Austrians

Austrians (, ) are the citizens and Nationality, nationals of Austria. The English term ''Austrians'' was applied to the population of Archduchy of Austria, Habsburg Austria from the 17th or 18th century. Subsequently, during the 19th century, ...

and Hungarians

Hungarians, also known as Magyars, are an Ethnicity, ethnic group native to Hungary (), who share a common Culture of Hungary, culture, Hungarian language, language and History of Hungary, history. They also have a notable presence in former pa ...

, while Bosnian Serbs on the other hand, were universally opposed to it, finding little reason to cheer the replacement of one foreign occupier with another — Serbia's old nemesis, the Habsburg Monarchy.

Bosnian Muslim reaction to the prospect of Austro-Hungarian rule was divided along social lines. Hoping that a smooth transfer of power would enhance their value to the new rulers and help preserve their privileged status and property rights, wealthy and influential landowners, despite being closely tied to the officials of the waning Ottoman regime, were now open to Austro-Hungarians. On the other hand, most of the Muslim religious authorities and lower-class Muslim population were stridently opposed, seeing nothing good in being ruled by a foreign non-Muslim power that had no plans to grant autonomy to Bosnia.

This economic class divide among the Bosnian Muslims on the Austro-Hungarian issue was clearly evident around Sarajevo in spring 1878. Members of Sarajevo's Muslim landowning elite showed public support for the Austro-Hungarian occupation at a meeting in April 1878 at the Emperor's Mosque, reasoning, as one cleric put it, that "''it was evident the Ottoman Empire had neither the power nor the support to rule the land''" before further asserting that "''a ruler who cannot control his land also loses claim to his subjects' obedience and since no Muslim would want to be a subject of Serbia or Montenegro, Austria-Hungary is the only viable alternative''". It didn't take long for the lower-class Muslim hostility to a possible Habsburg rule to surface. as in April and May 1878 a petition called the Allied Appeal written by two Islamic conservative religious officials from the Gazi Husrev-bey Mosque's madrasa

Madrasa (, also , ; Arabic: مدرسة , ), sometimes Romanization of Arabic, romanized as madrasah or madrassa, is the Arabic word for any Educational institution, type of educational institution, secular or religious (of any religion), whet ...

— effendi Abdulah Kaukčija and effendi Muhamed Hadžijamaković — were circulated in Sarajevo marketplaces. In addition to urging the population of Bosnia to unite in opposing the possible Austro-Hungarian occupation, the petition bore the imprint of Islamic religious conservatism, advocating making shari'a

Sharia, Sharī'ah, Shari'a, or Shariah () is a body of religious law that forms a part of the Islamic tradition based on Islamic holy books, scriptures of Islam, particularly the Quran, Qur'an and hadith. In Islamic terminology ''sharīʿah'' ...

the exclusive law of the land, demanding the dismissal of all Christian officials from the still-ruling Ottoman service, appealing for formation of an assembly to control the government, calling for removal of bells from the recently built Serb Orthodox Cathedral, and requesting demobilization of Ottoman troops. The petition reportedly included some five hundred signatures, but most Muslim landowners refused to sign it.

Reflecting personal politics and worldviews of two Sarajevan Islamic conservatives, well-respected in the local Muslim community, the petition reportedly also became a tool in the rivalry among the Ottoman officials in Bosnia. According to the Austro-Hungarian consul Wassitsch, the Ottoman governor in the Bosnian Vilayet Ahmed Mazhar Pasha planned to use the petition to gain popular support in a bid to keep his post in the event of Bosnia Vilayet acquiring autonomy as specified in the San Stefano Treaty. Mazhar's biggest obstacle in this regard was his own deputy Konstan Pasha, a Greek man of Orthodox faith who was uniformly described amongst the foreign consuls in Sarajevo as the only Christian to hold high office in the Ottoman civil administration in Bosnia. The petitioners' demand to eliminate all Christians would thus have removed Konstan from office and secured the Muslim Mazhar's post had the San Stefano agreement been implemented.

When several upper-class Muslims as well as some Serbian Orthodox leaders learned of the petition, they urged its redrafting without the explicitly anti-Christian demands, which was done, and a new version, written by an Ottoman official, began to circulate. The new petition, formally submitted to governor Mazhar on 2 June 1878, was seen as a win for the leading Muslim landowners who managed to purge it of its anti-Christian and anti-reform provisions. Its only two points were now a demand that a popular assembly rule the land and an appeal to all groups to unite in opposition to Austro-Hungarian occupation.

Formation of the People's Assembly

In the days following the petition's formal submission to the Ottoman governor, members of Sarajevo's Muslim elite built consensus among the factionalized local players. They managed to persuade representatives of lower-class Muslims, including religious leaders, to join a single all-Muslim assembly, and succeeded in getting governor Mazhar to allow the assembly to meet in the government headquarters building, the Konak. The new body, called the People's Assembly (''Narodni odbor''), met for the first on 5 June with an all-Muslim membership consisting of thirty individuals from the Muslim landowning elite and thirty lower-class Muslims (religious functionaries, artisans, and shopkeepers). In an appeal to the central Ottoman government, the assembly blamed Bosnia's woes on Istanbul's mismanagement and the government's failure to respond to individual complaints. The assembly's address continued by claiming that the distant government had driven them to form their own representative body to address local needs with local officials, and warned that the population would defend their land with their lives in the event of a war. It was necessary, the appeal went on, to retain permanent garrisons of Ottoman troops in the Bosnia Vilayet, and in any case the government could neither feed nor clothe its own troops. Finally, the appeal protested the punishment of deserters and their families. In its very first week, the assembly underwent four changes in composition as elite Muslims sought a formula that would include all ethnic, religious and financial class groups yet preserve their own dominance. On 8 June, the all-Muslim assembly appealed to Ottoman authorities to recognize a representative body of twelve Muslims, two Catholics, two Orthodox, and one Jew, all of them from Sarajevo, plus one Muslim and one Christian delegate from each of the six administrative districts (''kotars'') in the Bosnian Vilayet — a proposed composition that followed the makeup of the regional council, the consultative body formed in the 1860s that had governed city of Sarajevo since 1872. According to the proposal, matters affecting a single religion were to be handled by delegates from that group, and common matters would be decided in plenary sessions. Governor Mazhar approved the assembly's new composition after consulting with the regional council. The reconstituted, now multireligious, People's Assembly had its first meeting on 10 June in the Konak. Serbian Orthodox nominees originally refused to participate, claiming that the scheduled meeting fell on an Orthodox holiday, however, after the date was changed, they agreed to participate but declined to take an active role. At the first meeting, Serbian Orthodox representatives claimed they were underrepresented and the assembly honoured their request by inviting the Sarajevo Serbian Orthodox Commune to name three more delegates. The three selected were Risto Besara, Jakov Trifković, and Đorđe Damjanović. Still, though the Muslim lower classes were represented, most of the assembly members from all confessions came from the small group of local upper class leaders who enjoyed honorary Ottoman titles and close ties to the government. Wealthy Muslim landowner effendi Sunulah Sokolović who was also the regional council member was chosen as the People Assembly's president. Other Muslim members included Mustaj-beg Fadilpašić (son of the wealthy landowner and political leader Fadil-paša Šerifović), Mehmed-beg Kapetanović (wealthy landowner who came to Sarajevo from Herzegovina), effendi Mustafa Kaukčija, effendi Ahmet Svrzo, effendi Ragib Ćurčić, etc. Serbs were represented by merchant Dimitrije Jeftanović and effendi Petraki Petrović. Croats had friar Grga Martić and Petar Jandrić. And finally Jews were represented by effendi Salomon Isaković who made a good living by selling provisions to Ottoman troops. Steered along and finessed by the Muslim upper class members who had the most representation and influence, all the while avoiding divisive topics, the assembly managed to cobble together minimum unity and consensus throughout the month of June 1878. The big test would prove to be coming up with a coherent reaction to the decisions of the Berlin Congress that was simultaneously taking place.Treaty of Berlin

At the Berlin Treaty negotiations, the Austro-Hungarian side was represented by the k. und k. foreign minister, count

At the Berlin Treaty negotiations, the Austro-Hungarian side was represented by the k. und k. foreign minister, count Gyula Andrássy

Count Gyula Andrássy de Csíkszentkirály et Krasznahorka (, 8 March 1823 – 18 February 1890) was a Hungarian statesman, who served as Prime Minister of Hungary (1867–1871) and subsequently as List of foreign ministers of Austria-Hungar ...

, who was keen to expand the Imperial and Royal influence in the Balkans.

As a show of force and statement of intent, simultaneously with the start of the treaty negotiations in mid June 1878, the Austro-Hungarian Army began a major mobilization effort with more than 80,000 troops on its southeast border, ready to go into Bosnia Vilayet. For this action, the Austro-Hungarian authorities made a point of predominantly stacking their troops with k. und k. subjects of South Slavic origin — ethnic Croats

The Croats (; , ) are a South Slavs, South Slavic ethnic group native to Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina and other neighboring countries in Central Europe, Central and Southeastern Europe who share a common Croatian Cultural heritage, ancest ...

and ethnic Serbs

The Serbs ( sr-Cyr, Срби, Srbi, ) are a South Slavs, South Slavic ethnic group native to Southeastern Europe who share a common Serbian Cultural heritage, ancestry, Culture of Serbia, culture, History of Serbia, history, and Serbian lan ...

— feeling the Bosnia Vilayet population wouldn't be as outraged with the occupation after seeing their own kin amongst the invading troops.

On 28 June 1878, the terms and stipulations of the Treaty of Berlin were announced and according to its 25th point, Austria-Hungary received a mandate to "occupy and administer the Bosnian Vilayet", but not to annex it. The treaty thus officially nullified the provision of the San Stefano Treaty that foresaw autonomy for the Bosnian Vilayet.

Austro-Hungarian takeover

Austria-Hungary asserted its intent to occupy Bosnia vilayet in a telegram from Andrassy's foreign ministry received by the k. und k. consul in Sarajevo Konrad von Wassitsch on 3 July with Ottoman officials in the Konak also learning of the impending occupation from telegrams that arrived shortly after Wassitsch's. To some, such an open manner of announcing the Berlin Treaty's occupation terms was indicative of Vienna's assumption that they would be welcomed with open arms by the local population.Local reaction to the Berlin Treaty

By the next morning, city was abuzz with rumours and trepidation as Wassitsch made rounds to visit with upper-class Muslim landowners and the main leaders of the local People's Assembly, Mehmed-beg Kapetanović, Sunulah Sokolović, and Mustaj-beg Fadilpašić, reminding them of the generous benefits that would come to those loyal to the new regime. Each of the three promised to work toward a peaceful reception for k. und k. troops, though at the same time expressing fears of a lower-class uprising in opposition to new occupiers. Later that day Wassitsch went to see Ottoman governor Mazhar who told him he would support armed resistance to Austro-Hungarian rule unless he received orders from Istanbul to the contrary. At a regional council meeting the same day, Mazhar called on the councilors to support a resistance movement. This created a strange situation with Sokolović, president of the People's Assembly and a member of the regional council, taking the unusual step of opposing the governor's recommendation by advocatingpeaceful transition of power

A peaceful transition or transfer of power is a concept important to democracy, democratic governments in which the leadership of a government peacefully hands over control of government to a newly elected leadership. This may be after elections o ...

to Habsburg officials while Fadilpašić and Kapetanović backed him at the same meeting. Public demand for resistance among the lower-class masses was in evidence during the same day as a large green flag was hoisted in the courtyard of the Gazi Husrev-beg Mosque

Gazi Husrev-beg Mosque (, ) is a mosque in the city of Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina. Built in the 16th century, it is the largest historical mosque in Bosnia and Herzegovina and one of the most representative Ottoman structures in the Balkan ...

.

The next day, 5 July, following noontime prayers Muslim worshipers lingered in the surrounding streets as they listened to local rabble-rouser Salih Vilajetović, better known around the city as Hadži Lojo, deliver a stirring speech in which he called for Wassitsch and the rest of the Austro-Hungarian consulate staff to be expelled from the city. A tall, strong, and physically imposing 44-year-old agitator, Hadži Lojo was quite well known locally, having for years served as imam at a small Sarajevo mosque and taught religion at a trade school. He also had a history of unlawful activity having recently returned to Sarajevo after being expelled and living as a brigand

Brigandage is the life and practice of highway robbery and plunder. It is practiced by a brigand, a person who is typically part of a gang and lives by pillage and robbery.Oxford English Dictionary second edition, 1989. "Brigand.2" first record ...

for three years. Sharing both his vocation and educational background with Hadžijamaković and Kaukčija, the two Gazi Husrev-bey Mosque clerics behind the April Petition, Hadži Lojo very well understood the local Muslim political and religious culture in which he operated and skillfully exploited it to galvanize the crowd into action. Following his impassioned speech, Hadži Lojo unfurled a green flag and led the crowd from the mosque to Konak across river Miljacka

The Miljacka ( sr-Cyrl, Миљацка) is a river in Bosnia and Herzegovina that passes through Sarajevo. Numerous city bridges have been built to cross it.

Characteristics

The Miljacka river originates from the confluence of the Paljanska Mi ...

to confront governor Mazhar and other Ottoman officials. The demonstrators' fury was directed as much at Sultan Abdul Hamid II

Abdulhamid II or Abdul Hamid II (; ; 21 September 184210 February 1918) was the 34th sultan of the Ottoman Empire, from 1876 to 1909, and the last sultan to exert effective control over the fracturing state. He oversaw a Decline and modernizati ...

as it was at the Berlin Treaty decisions, with the bellowing cry of 'You can give away Istanbul, Stambul, but not Bosnia'. Mazhar addressed the angry mob from the Konak's balcony, appealing on them to disperse, but after they failed to adhere he made a concession by agreeing to dismiss current the Ottoman military commander, an unpopular figure, promising that he'd be replaced with a new Sarajevo-born commander. Satisfied for the moment, the Muslims dispersed at dusk.

By 7 July, governor Mazhar heard from his Istanbul superiors, receiving only vague instructions to retain public order pending conclusion of negotiations with Austria-Hungary. Lacking firm direction, he continued to take a permissive stance towards the possibility of local armed resistance to Habsburg rule.

Crowds of local Muslim men continued their daily gatherings to demonstrate in the courtyards of Gazi Husrev-beg Mosque and the Sultan's Mosque. They wanted Sarajevan Christians and Jews to join them too, who out of concern for their safety mostly retired to their homes when the demonstrations began. Within days, on 9 July, the crowd managed to force the People's Assembly to relocate from Konak to Morića Han across the river — a move seen as assembly's symbolic transition from a representative body under elite Muslim control to an activist gathering under the influence of the conservative religious establishment and lower-class Muslims.

On 10 July, the crowd demanded a change in the People's Assembly composition. so that groups claiming underrepresentation got more members. According to Wassitsch, this particular demand was instigated and pushed through by pan-Slav activists opposing Habsburg rule, leading to an increased number of Serb Orthodox members in the reconstituted assembly so that the new body consisted of 30 Muslims, 15 Serbs, 3 Jews, and 2 Croats. Most Muslim landlords abandoned the assembly within days, the only exception being Mustaj-beg Fadilpašić who was persuaded to stay and was elected as the new president.

With most upper-class Muslims gone, the assembly came under Hadži Lojo's control. He essentially turned it into the organizing body for armed resistance to Habsburg occupation. It was divided into two committees, one to assemble troops and the other to secure provisions and funds. Seeking credibility with Ottoman authorities, Hadži Lojo assembled an armed retinue that he moved around with, even showing up in Konak to seek immunity from Mazhar for past misdeeds. After receiving it, Hadži Lojo even made the humiliated governor pay him a token cash payment in recognition of his name being cleared.

The fading Ottoman authority in Sarajevo received some reinforcements on 12 July with four battalions dispatched from Istanbul under new military commander Hafiz Pasha. With governor Mazhar Pasha's credibility gone, commander Hafiz Pasha was now the only authority in the city. Though at first urging the local population to accept Austro-Hungarian occupation, he then sat at subsequent regional council meetings in enigmatic silence, leaving the foreign consul to ponder his personal attitude towards possible armed resistance as the invasion drew near. Although his predecessor banned the People's Assembly meetings, Hafiz didn't interfere when the meetings resumed on 18 July with preparations for armed resistance their only order of business as Sarajevo settled into an uneasy peace.

With the Hadži Lojo-controlled Assembly getting ready for a fight unimpeded by Ottoman authority, the Ottomans still retained the weapons and ammunition depots as confrontation between Hafiz and Hadži Lojo seemed inevitable. On 25 July Hadzi Lojo led a crowd in front of Konak demanding access to weapons depots from Hafiz, who told the crowd he would wire the request to Istanbul, which won him another 48 hours.

Civil disorder

On 27 July, further evidence of Austro-Hungarian invasion sparked unrest as consul Wassitch distributed copies of the Emperor's proclamation about the occupation. In his report, Wassitch noted seeing shopkeepers closing up before noon in order to go home and claim weapons as the final assault on the Ottoman authority in the city was being prepared by Hadži Lojo. Just after noon, a crowd led by the charismatic populist leader showed up in front of the Konak where Ottoman officials and local Muslim elite had fled for protection. Local Muslim conscripts from nearby barracks deserted their units, joining the armed mob. Around 4 p.m. Hafiz's remaining Ottoman force tried to clear the street next to the Konak building, but the crowd, now swollen with defecting soldiers, fought back as the two groups exchanged close-range fire. with an estimated twenty casualties on both sides. In the end, the Ottoman forces managed to clear the street, but were also faced with more local soldiers deserting its ranks. As night fell on the city, Hafiz's dwindling troops returned to their barracks while resurgent crowds outside began cutting water lines to the barracks, blocking the delivery of provisions, and cutting telegraph wires, hoping to isolate the city and prevent the Ottomans from summoning reinforcements. The People's Assembly began a meeting at the Sultan's Mosque that continued long into the night.The People's Government is proclaimed

At daybreak, Hafiz made one last attempt to restore his authority by leading his loyalists to the Bijela Tabija fortress high above the city, but got nowhere as more of his troops deserted. He was captured and escorted back down into the city where he was turned over to Hadži Lojo and put in jail; the crowd prevailed and by 9 a.m. took control of the Ottoman weaponry. The same day, the crowd's leaders, led by members of the People's Assembly, met at the Gazi Husrev-beg Mosque to proclaim the People's Government (Narodna vlada). Despite dominant sentiment favouring the election of native Bosnians, the leaders persuaded the crowd to elect Hafiz as governor, thus providing a thread of continuity with the previous regime. Muhamed Hadžijamaković, one of the instigators of the April petition, was made the Commander of the People's Army while an emissary was dispatched to Wassitch to assure him that no harm would come to him, to others in his consulate, or to other consuls in the city. Within hours, he received another visit from the People's Government leaders, who asked if he wished to depart for the Adriatic coast along with the party of deposed Ottoman officials. Wassitch opted to stay. Later that day, the two former rival and top Ottoman officials, Mazhar Pasha and Konstan Pasha, were stopped by the crowd as they departed Sarajevo for Istanbul via Mostar. While in the hands of the angry crowd, they were robbed of all their possessions and their lives were threatened. Reacting to the capture, Wassitsch proposed that all five consuls appear together at the Konak to ask that the two pashas and other prisoners be delivered to them, however the other four consuls (meeting without Wassitch because troops loyal to the crowd surrounded the Austro-Hungarian consulate) felt that any demarche involving Wassitsch was bound to inflame the crowd. Instead they agreed to send a conciliatory letter asking that the lives of the two captive Ottoman officials be spared. Just in time, Hadzi Lojo personally intervened to rescue the two officials. They both eventually reached Istanbul and returned to their careers in the Ottoman bureaucracy.Austro-Hungarian Army invades Bosnia

On 29 July 1878, one day after the People's Government was proclaimed in Sarajevo, the Austro-Hungarian Army under the command of feldzeugmeister (general) Josip Filipović, an ethnic Croat from Gospić, entered the Bosnia Vilayet at four different crossings. Filipović's idea was to first secure the major transportation arteries and the largest towns. Approaching from the south, west, and north, the k. und k. forces planned to suppress the resistance by conquering Sarajevo, its organizing center. In Sarajevo, the resistance fighters, overwhelmingly made up of local lower-class Muslims received some unexpected reinforcements as the local Serbs, encouraged by their religious and community leaders, began taking up arms and joining the resistance. This sudden cooperation between Muslims and Serbs contrasted remarkably with their grinding conflict of several years earlier during the Herzegovina Uprising when Serbian Orthodox ''serfdom, kmets'' rose up against Muslim ''beys''. However, according to historian Misha Glenny, the sudden alliance between Muslims and Serbs reflected a temporary coincidence of interests, rather than a basis for a future alliance. With a force of some 80,000 soldiers in total, 9,400 of which were 'occupation troops' under feldmarschallleutnant (lieutenant-general) Stjepan Jovanović, another ethnic Croat from Lika and former k. und k. consul in Sarajevo from 1861 until 1865, whose role was to move across the border from Kingdom of Dalmatia, Austrian Dalmatia into Herzegovina and hold places once they're taken by the main fighting force, Filipović's Austro-Hungarian Army moved swiftly down through northern Bosnia, seizing Banja Luka, Maglaj, and Jajce, encountering several successful resistance ambushes along the way that slowed down their progress. On 3 August a group of hussars was ambushed near Maglaj on the Bosna river, prompting Filipović to institute martial law. Austro-Hungarian consul Wassitsch fled Sarajevo with his staff and belongings on 4 August after receiving a written directive from the revolutionary government to leave the city. He led a convoy of about one hundred consular employees and Austro-Hungarian citizens on the road to Mostar. The people's government provided armed escorts to ward off dangers posed by Muslim irregulars along the way. Wassitsch and his entourage safely reached the border near Metković several days later. Meanwhile, feldmarschallleutnant Jovanović's second occupying force, the 18th Division (Austria-Hungary), 18th Division, had been advancing up along the Neretva river, capturing Mostar on 5 August. On 7 August a pitched battle was fought near Jajce and the Austro-Hungarian infantry lost 600 men. Within days of crossing the border into Bosnia, feldzeugmeister Filipović came to the conclusion that the Austro-Hungarian 'soft strategy' of capturing town-by-town is not going to work and that the aim of occupying Sarajevo would require more manpower and more brutal tactics, so he requested and received reinforcements. The k. und k. force more than tripled with 268,000 men now on the ground trying to occupy Bosnia Vilayet. Well equipped and well informed about the towns, roads, and bridges in their path, the Austro-Hungarians heavily defeated the local resistance at the battle of Klokoti near Vitez on 16 August. Two days later they reached the outskirts of Sarajevo and began installing cannons on the hills surrounding the city.Battle of Sarajevo

;radiosarajevo.ba, 20 October 2012Uz proslavu 550 godina Sarajeva

portal.skola.ba, 17 May 2012 to the hills surrounding the city. Then, the infantry came into the city from the western direction of

Ilidža

Ilidža ( sr-cyrl, Илиџа, ) is a spa town and a municipality located in Sarajevo Canton of the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, an entity of Bosnia and Herzegovina. It has a total population of 66,730 with 63,528 in Ilidža itself, and i ...

, facing a spirited resistance from some 5,000 citizens of Sarajevo who heeded a call to arms. Pushing the resistance fighters towards the more densely populated city center, gunfire welcomed the invading troops “from every house, from every window, from every doorway…even women were taking part” as urban warfare, close combat ensued for individual streets and houses with children also resisting in addition to women. A particularly vicious battle took place near the Ali Pasha Mosque (Sarajevo), Ali Pasha's Mosque with some 50 resistance fighters losing their lives with some executed right on the spot.

By 1:30pm the Austro-Hungarians essentially won the battle as the resistance fighters got pushed outside of the city towards Romanija and by early evening Sarajevo found itself under full Habsburg control. Around 5pm Filipović triumphantly marched into the Konak, the Ottoman governor's residence, thus symbolically commencing the Austro-Hungarian era in Sarajevo and Bosnia.

The Austro-Hungarian casualties in Sarajevo were reportedly 57 dead and 314 injured. On the resistance side around 400 casualties were reported. The k. und k. principal force moved on to Herzegovina and the Sanjak of Novi Pazar.

Austro-Hungarian revenge in Sarajevo

On 23 August, only four days after conquering Sarajevo, feldzeugmeister Filipović impaneled a special court with summary judgement authority. Over the following several days nine Sarajevo Muslims were hanged for instigating the uprising or leading the resistance against Austro-Hungarian troops. The first condemned to death was Muhamed Hadžijamaković. While approaching the Konak to give himself up to Filipović, he was captured, then taken to a trial the same day, sentenced to death by mid-afternoon, and finally around 4 p.m. taken to be hanged from an oak tree. Though over sixty years of age, large and powerful Hadžijamaković managed to wrest a revolver from one of his captors and fire twice, injuring several guards in the ensuing struggle. Bloodied and unconscious from a knife wound, mortally wounded Hadžijamaković was hanged after sunset. The next to be executed was Hadžijamaković's fellow cleric and resistance leader Abdulah Kaukčija. He too received a brief hearing on 24 August before being sentenced to death by hanging the same day. Over the next few days seven more Muslim resistance fighters — Avdo Jabučica, hadži Avdaga Halačević, Suljo Kahvić, hadži Mehaga Gačanica, Mehmed-aga Dalagija, Ibrahimaga Hrga, and Mešo Odobaša — were hanged as the resistance was still gaining strength in areas outside Sarajevo.Austro-Hungarian rule

The Habsburg period of Sarajevo's history was characterized by industrialization, development, westernization, and social change. It could be argued that the three most prominent alterations made by the Habsburgs to Sarajevo were to the city's political structure, architecture style, and education system.Political

The immediate political change made by the Austrians was to do away with what were then regarded as outdated Ottoman political divisions of the city, and put in place their own system which was centered on major roads.1880s architectural expansion

Educational

As the Austro-Hungarians believed theirs was a far more modern and advanced nation than theOttoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

, Sarajevo was quickly westernized and adapted to their standards. A western education system was implemented, and Sarajevo's inhabitants started writing in Latin script for the first time.

End of Habsburg dominance

In 1908, the territory was formally annexed and turned into a condominium (international law), condominium jointly controlled by both Austrian Cisleithania and Hungarian Transleithania. By 1910, Sarajevo was populated by just under 52,000 people. Just four years later the most famous event in the history of Habsburg Sarajevo, and perhaps in the city's history, occurred. The assassination in Sarajevo, in which a young Serb nationalist named Gavrilo Princip assassinated Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria and his wife Sophie, Duchess of Hohenberg on their visit to the city, started a chain of events that led to World War I. At the end of the Great War and as part of the 1919 Paris Peace Conference, Austria-Hungary ceased to exist. Sarajevo became part of the new Kingdom of Yugoslavia.Yugoslavia

After World War ISarajevo

Sarajevo ( ), ; ''see Names of European cities in different languages (Q–T)#S, names in other languages'' is the Capital city, capital and List of cities in Bosnia and Herzegovina, largest city of Bosnia and Herzegovina, with a population of 2 ...

became part of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia. Though it held some political importance, as the center of first the Bosnian region and then the Drina Banovina, it was not treated with the same attention or considered as significant as it had been in the past. Outside of today's national bank of Bosnia and Herzegovina, virtually no significant contributions to the city were made during this period.

During World War II the Kingdom of Yugoslavia put up a very inadequate defense. Following a German bombing campaign, Sarajevo was taken by the Wehrmacht on 15 April 1941. When the Wehrmacht marched in, a large crowd of Bosnian Muslims came out to welcome them while the streets in the Muslim quarter were decorated with swastikas. However, the historian David Motadel noted that those Bosnian Muslims loyal to Yugoslavia would have been unlikely to display their colors as the Wehrmacht marched in. One of the first acts of the new German occupation regime was to blow up the plaque celebrating Gavrilo Princip's assassination of the Archduke Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria, Franz Ferdinand. As part of the carve-up of Yugoslavia all of Bosnia-Herzegovina was assigned to the Ustase Croats, Croatian fascist NDH (''Nezavisna Država Hrvatska''--Independent State of Croatia), a puppet state of Nazi Germany. In 1941, Sarajevo had 85, 000 people and the population of the city was 34% Muslim, 29% Catholic Croat, 25% Orthodox Serb and 10% Jewish. Despite their different religions, all four of these ethnoreligious groups spoke the same language, namely Serbo-Croatian. The Ustaše ascribed to an extremely virulent and violent racist ethnoreligious ultra-nationalism, which defined being Croat in racial and religious terms. The policy of the Ustaše regime was to forcibly convert one-third of the Serbs living in the NDH to Roman Catholicism, expel one-third into Serbia and to kill the remaining one-third. Likewise, the Jews and Romany (Gypsies) living in the NDH were to be exterminated. Ante Pavelić, the ''Poglavnik'' ("Leader") of the Ustaše was sympathetic towards Bosnian Muslims, whom he considered "Croats of Muslim faith", and he appointed a Bosnian Muslim as mayor of Sarajevo and a Croat as deputy mayor. Despite Pavelić onward proclamations of friendship towards the Bosnian Muslims and the status of Islam as a nearly co-equal "national religion", many Bosnian Muslims complained in the NDH Roman Catholicism was treated as the first national religion and Islam as the second national religion. In general felt that they had a lesser status compared to the Roman Catholics in the NDH. By late April 1941, over a thousand Ustaše Militia, Ustaše Militiamen had been assigned to Sarajevo. The majority of the Ustaše militia in Sarajevo were not from Bosnia-Herzegovina, but rather came from the rural areas of northern Croatia. The Ustaše militiamen quickly made themselves unpopular in Sarajevo on the account of their rapacious corruption and insatiable greed along with arrogant bullying behavior and boorish manners.

The principle targets of violence by the Ustaše were Sarajevo's Serb, Jewish and Romany populations, who in the Ustaše ideology had no place in the NDH. One of the first acts of the Ustaše was to fire all Serbs from the city government, ban the use of the Cyrillic alphabet and shut down services of the Orthodox church. The Ustaše also targeted those Bosnian Muslims known to be loyal to Yugoslavia for execution. Likewise, Bosnian Muslims were executed for having engaged in what considered to be "Serbian" behavior such as writing Serbo-Croatian in the Cyrillic alphabet instead of the Latin alphabet as the Ustaše favored. The Sarajevo police department, which was staffed by Ustaše loyalists, would raid Serb communities at night to pick up small groups of Serbs who taken out to the countryside to be executed, via the usual Ustaše methods of stabbed, hacked or clubbed to death. The largest of these raids occurred on 11 August 1941 when about 100 Sarajevo Serbs were arrested on allegations of belonging to either the Chetniks or the Partisans. About a dozen were executed with the rest being sent to concentration camps. The majority of the Serbs executed in Sarajevo were intellectuals. As common with the "submerged" nations of Eastern Europe, intellectuals in Bosnia-Herzegovina had an immense influence as the bearers and trustees of the national culture. Targeting Serb intellectuals for execution was a form of not only physical genocide, but also cultural genocide as well intended to deprive the Serb community of its natural leaders. The inability of the Ustaše to set up a properly functioning economy and the fixture of the NDH regime on creating an racially and ethnically pure nation-state at the expense of economic issues made the new regime very unpopular in Sarajevo with all the ethnic groups. Despite the orders to fire all Serbs from the local government, in practice it proved impossible to do so without throwing Sarajevo into chaos as for an example one-third of all teachers in Sarajevo and half of the judges were Serbs. There were several times when the Ustaše ended in face-offs with local Bosnian Croats who refused to take part in the executions of their Serb friends and colleagues.

On 12 October 1941 a group of 108 notable Muslim citizens of Sarajevo signed the Resolution of Sarajevo Muslims in which they condemned the World War II persecution of Serbs, persecution of Serbs organized by Ustaše, made a distinction between Muslims who participated in such persecutions and the whole Muslim population, presented information about the persecutions of Muslims by the Chetniks and requested security for all citizens of the country, regardless of their identity. Many of the city's Serbs

The Serbs ( sr-Cyr, Срби, Srbi, ) are a South Slavs, South Slavic ethnic group native to Southeastern Europe who share a common Serbian Cultural heritage, ancestry, Culture of Serbia, culture, History of Serbia, history, and Serbian lan ...

, Romani, and Jews were killed in the Holocaust bringing a sad end to the prominence of Sarajevo's Jewish community. In 1941, the atrocities committed by the Ustase were strongly condemned by groups of Sarajevo's citizens. Between 5-9 April 1943, Sarajevo was visited by the Grand Mufti of Jerusalem, Amin al-Husseini, as a part of a recruiting tour for the 13th Waffen Mountain Division of the SS Handschar (1st Croatian), 13th Waffen SS ''Handschar'' division. In Sarajevo, the Grand Mufti met with Muslim leaders from across the Balkans, through the fact that Grand Mufti only spoke Arabic required a translator when he gave the Friday sermon at the Gazi Husrev-beg Mosque

Gazi Husrev-beg Mosque (, ) is a mosque in the city of Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina. Built in the 16th century, it is the largest historical mosque in Bosnia and Herzegovina and one of the most representative Ottoman structures in the Balkan ...

.

The Sarajevo resistance was led by a Partisans (Yugoslavia), NLA Partisan named Vladimir Perić, Vladimir "Valter" Perić. Legend has it that when a new German officer came to Sarajevo and was assigned to find Valter, he asked his subordinate to show him Valter. The man took the officer to the top of a hill overlooking the city and said "See this city?", "Das ist Valter". Valter was killed in the fighting on the day of Sarajevo's liberation, 6 April 1945. He has since become a city icon.

Following the liberation, Sarajevo was the capital of the republic of Bosnia within the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. The communists invested heavily in Sarajevo, building many new residential blocks in Novi Grad Municipality and Novo Sarajevo Municipality, while simultaneously developing the city's industry and transforming Sarajevo once again into one of the Balkans' chief cities. From a post-war population of 115,000, by the fall of Yugoslavia Sarajevo had 429,672 people.

Sarajevo hosted the 1984 Winter Olympics. They are widely regarded as among the most successful winter Olympic Games in history. They were followed by an immense boom in tourism, making the 1980s one of the city's best decades in a long time.

Modern

The history of modernSarajevo

Sarajevo ( ), ; ''see Names of European cities in different languages (Q–T)#S, names in other languages'' is the Capital city, capital and List of cities in Bosnia and Herzegovina, largest city of Bosnia and Herzegovina, with a population of 2 ...

begins with the declaration of independence of Bosnia and Herzegovina

Bosnia and Herzegovina, sometimes known as Bosnia-Herzegovina and informally as Bosnia, is a country in Southeast Europe. Situated on the Balkans, Balkan Peninsula, it borders Serbia to the east, Montenegro to the southeast, and Croatia to th ...

from Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, Yugoslavia. The city then became the capital of the new state, as the local division of the Yugoslav People's Army established itself on the surrounding mountains. That day, massive peace protests took place. In the midst of the largest one, a protester named Suada Dilberović was shot by unidentified gunmen from a nearby skyscraper.

The following three years found Sarajevo the center of the longest siege in the history of modern warfare (See: Siege of Sarajevo). The city was held without electricity, heating, water, or medical supplies. During this time, the surrounding Serb forces shelled the city. An average of 329 shell impacts occurred per day, with a high of 3,777 shell impacts on 22 July 1993.

Aside from the economic and political structures, the besiegers targeted numerous cultural sites. Thus places such as the Gazi Husrev-beg's Mosque, Cathedral of Jesus' Heart, and the Jewish cemetery were damaged, while places like the old City Hall and the Olympic museum were completely destroyed. For foreigners an event that defined the cultural objectives of the besiegers occurred during the night of 25 August 1992, the intentional shelling and utter destruction with incendiary shells of the irreplaceable Bosnia National and University Library, the central repository of Bosnian written culture, and a major cultural center of all the Balkans. Among the losses were about 700 manuscripts and incunabula and a unique collection of Bosnian serial publications, some from the mid-19th century Bosnian cultural revival. Libraries all over the world cooperated afterwards to restore some of the lost heritage, through donations and e-texts, rebuilding the library in cyberspace.

It is estimated that 12,000 people were killed and another 50,000 wounded during the siege. Through all this time however, the Bosnian Serb army was unable to decisively capture the city thanks to the effort of the Bosnian forces inside it. Following the Dayton Agreement, Dayton Accords and a period of stabilization, the Bosnian government declared the siege officially over on 29 February 1996. Exodus of Sarajevo Serbs, Most Serbs left Sarajevo in early 1996.

The next several years were a period of heavy reconstruction. During the siege, nearly every building in the city was damaged. Ruins were present throughout the city, and bullet holes were very common. Land mines were also located in the surroundings.

Thanks to foreign aid and domestic dedication, the city began a slow path to recovery. By 2003, there were practically no ruins in the city and bullet holes had become a rarity. Sarajevo was hosting numerous international events once again, such as the extremely successful Sarajevo Film Festival, and launched bids to hold the Winter Olympic Games in the city in the not so distant future.

Today Sarajevo is one of the fastest-developing cities in the region. Various new modern buildings have been built, significantly the Bosmal City Center and the Avaz twist tower which is tallest skyscraper in the Balkans. A new highway was recently completed between Sarajevo and the city of Kakanj. The Sarajevo City Center which started construction in 2008 opened early to public in 2014. If current growth trends continue, the Sarajevo metropolitan area should return to its pre-war population by 2020, with the city following soon after. At its current pace, Sarajevo won't surpass the million resident mark until the second half of the 21st century. The most widely accepted and pursued goal was for the city to hold the Winter Olympics in 2014. The bid failed but Sarajevo managed to hold the 2019 European Youth Olympic Winter Festival, the second major winter sports event after the 1984 Winter Olympic Games.