Sandino Rebellion on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The United States occupation of Nicaragua from August 4, 1912, to January 2, 1933, was part of the

In 1909 Nicaraguan President

In 1909 Nicaraguan President  Zelaya resigned on December 14, 1909, and his hand-picked successor, Jose Madriz, was elected by unanimous vote of the liberal Nicaraguan national assembly on December 20, 1909.

Zelaya resigned on December 14, 1909, and his hand-picked successor, Jose Madriz, was elected by unanimous vote of the liberal Nicaraguan national assembly on December 20, 1909.

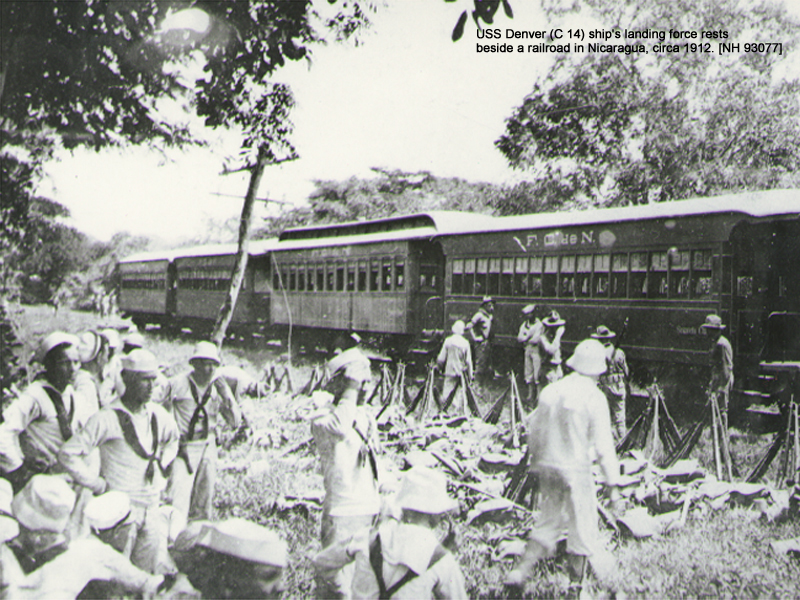

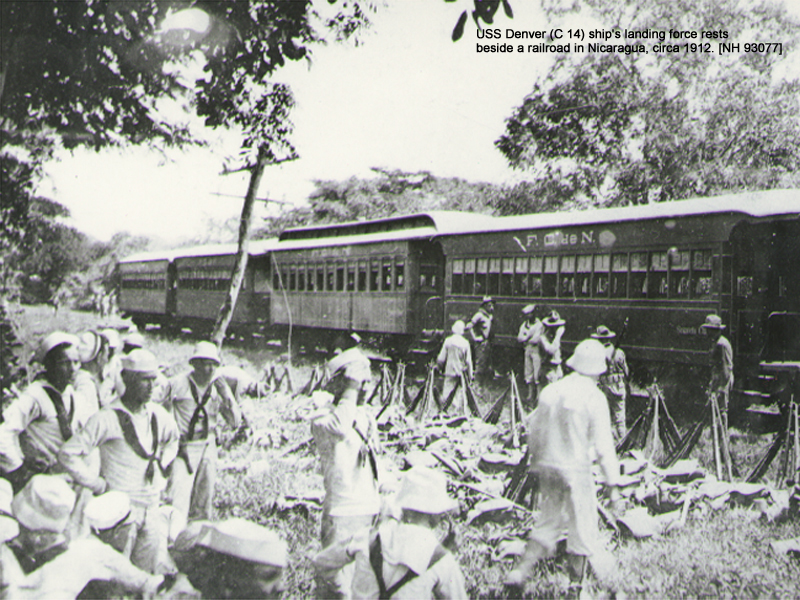

On August 29, 1912, a landing force of 120 men from USS ''Denver'', under the command of the ship's navigator, Lieutenant Allen B. Reed, landed at Corinto to protect the railway line running from Corinto to Managua and then south to Granada on the north shore of Lake Nicaragua. This landing party reembarked aboard ship October 24 and 25, 1912. One officer and 24 men were landed from the ''Denver'' at

On August 29, 1912, a landing force of 120 men from USS ''Denver'', under the command of the ship's navigator, Lieutenant Allen B. Reed, landed at Corinto to protect the railway line running from Corinto to Managua and then south to Granada on the north shore of Lake Nicaragua. This landing party reembarked aboard ship October 24 and 25, 1912. One officer and 24 men were landed from the ''Denver'' at

Nicaragua 8 1850–1868

Sandino rebellion 1927–1934

{{coord, 13.0000, N, 85.0000, W, source:wikidata, display=title * Conflicts in 1912 1910s in Nicaragua

Banana Wars

The Banana Wars were a series of conflicts that consisted of military occupation, police action, and Interventionism (politics), intervention by the United States in Central America and the Caribbean between the end of the Spanish–American W ...

, when the U.S. military

The United States Armed Forces are the military forces of the United States. U.S. federal law names six armed forces: the Army, Marine Corps, Navy, Air Force, Space Force, and the Coast Guard. Since 1949, all of the armed forces, except th ...

invaded various Latin America

Latin America is the cultural region of the Americas where Romance languages are predominantly spoken, primarily Spanish language, Spanish and Portuguese language, Portuguese. Latin America is defined according to cultural identity, not geogr ...

n countries from 1898 to 1934. The formal occupation began on August 4, 1912, even though there were various other assaults by the United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

in Nicaragua

Nicaragua, officially the Republic of Nicaragua, is the geographically largest Sovereign state, country in Central America, comprising . With a population of 7,142,529 as of 2024, it is the third-most populous country in Central America aft ...

throughout this period. American military interventions in Nicaragua were designed to stop any nation other than the United States of America

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 contiguo ...

from building a Nicaraguan Canal

Attempts to build a canal across Nicaragua to connect the Atlantic Ocean with the Pacific Ocean stretch back to the early colonial era. Construction of such a shipping route—using the San Juan River (Nicaragua), San Juan River as an access ro ...

.

Nicaragua assumed a quasi-protectorate

A protectorate, in the context of international relations, is a State (polity), state that is under protection by another state for defence against aggression and other violations of law. It is a dependent territory that enjoys autonomy over ...

status under the 1916 Bryan–Chamorro Treaty

The Bryan–Chamorro Treaty was signed between Nicaragua and the United States on August 5, 1914. It gave the United States full rights over any future canal built through Nicaragua. The Wilson administration changed the treaty by adding a provis ...

. President Herbert Hoover

Herbert Clark Hoover (August 10, 1874 – October 20, 1964) was the 31st president of the United States, serving from 1929 to 1933. A wealthy mining engineer before his presidency, Hoover led the wartime Commission for Relief in Belgium and ...

(1929–1933) opposed the relationship. On January 2, 1933, Hoover ended the American intervention.

Conflicts in Nicaragua

Estrada's rebellion (1909)

In 1909 Nicaraguan President

In 1909 Nicaraguan President José Santos Zelaya

José Santos Zelaya López (1 November 1853 – 17 May 1919) was the President of Nicaragua from 25 July 1893 to 21 December 1909. He was liberal.

In 1909, Zelaya was ousted from office in a rebellion led by conservative Juan José Estrada w ...

of the Liberal Party

The Liberal Party is any of many political parties around the world.

The meaning of ''liberal'' varies around the world, ranging from liberal conservatism on the right to social liberalism on the left. For example, while the political systems ...

faced opposition from the Conservative Party, led by governor Juan José Estrada

Juan José Estrada Morales (1 January 1872 in Managua – 11 July 1967 in Managua) was the President of Nicaragua from 29 August 1910 to 9 May 1911.

Biography

Juan José Estrada Morales was a Nicaraguan military and political figure who acte ...

of Bluefields

Bluefields is the capital of the South Caribbean Autonomous Region in Nicaragua. It was also the capital of the former Kingdom of Mosquitia, and later the Zelaya Department, which was divided into North and South Caribbean Coast Autonomous Reg ...

who received support from the U.S. government as a result of American entrepreneurs providing financial assistance to Estrada's rebellion in the hopes of gaining economic concessions after the rebellion's victory. The United States had limited military presence in Nicaragua, having only one patrolling U.S. Navy ship off the coast of Bluefields, allegedly to protect the lives and interests of American citizens who lived there. The Conservative Party sought to overthrow Zelaya which led to Estrada's rebellion in December 1909. Two Americans, Leonard Groce and Lee Roy Cannon, were captured and indicted for allegedly joining the rebellion and the laying of mines. Zelaya ordered the execution of the two Americans, which severed U.S. relations

The United States has formal diplomatic relations with most nations. This includes all United Nations members and observer states other than Bhutan, Iran, North Korea and Syria, and the UN observer Palestine, Territory of Palestine. Additiona ...

.

The forces of Emiliano Chamorro Vargas

Emiliano Chamorro Vargas (11 May 1871 – 26 February 1966) was a Nicaraguan military figure and politician who served as President of Nicaragua from 1 January 1917 to 1 January 1921. He was a member of the Conservative Party.

He lost the 192 ...

and Nicaraguan General Juan Estrada, each leading conservative revolts against Zelaya's government, had captured three small towns on the border with Costa Rica

Costa Rica, officially the Republic of Costa Rica, is a country in Central America. It borders Nicaragua to the north, the Caribbean Sea to the northeast, Panama to the southeast, and the Pacific Ocean to the southwest, as well as Maritime bo ...

and were fomenting open rebellion in the capital of Managua

Managua () is the capital city, capital and largest city of Nicaragua, and one of the List of largest cities in Central America, largest cities in Central America. Located on the shores of Lake Managua, the city had an estimated population of 1, ...

. U.S. Naval warships that had been waiting off Mexico and Costa Rica moved into position.

The protected cruisers , , and collier lay in the harbor at Bluefields, Nicaragua

Bluefields is the capital of the South Caribbean Autonomous Region in Nicaragua. It was also the capital of the former Kingdom of Mosquitia, and later the Zelaya Department, which was divided into North and South Caribbean Coast Autonomous Reg ...

, on the Atlantic coast with en route for Colón, Panama

Colón () is a city and Port#Seaport, seaport in Panama, beside the Caribbean Sea, lying near the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic entrance to the Panama Canal. It is the capital of Panama's Colón Province and has traditionally been known as Panama's se ...

, with 700 Marines. On December 12, 1909, ''Albany'' with 280 bluejackets and the gunboat with 155, arrived at Corinto, Nicaragua

Corinto is a town, with a population of 18,602 (2022 estimate), on the northwest Pacific coast of Nicaragua in the province of Chinandega. The municipality was founded in 1863.

History Early years

The town of Corinto was founded in 1849. It first ...

, to join the gunboat with her crew of 155 allegedly to protect American citizens and property on the Pacific coast of Nicaragua.

Zelaya resigned on December 14, 1909, and his hand-picked successor, Jose Madriz, was elected by unanimous vote of the liberal Nicaraguan national assembly on December 20, 1909.

Zelaya resigned on December 14, 1909, and his hand-picked successor, Jose Madriz, was elected by unanimous vote of the liberal Nicaraguan national assembly on December 20, 1909. U.S. Secretary of State

The United States secretary of state (SecState) is a member of the executive branch of the federal government of the United States and the head of the U.S. Department of State.

The secretary of state serves as the principal advisor to the p ...

Philander C. Knox

Philander Chase Knox (May 6, 1853October 12, 1921) was an American lawyer, bank director, statesman and Republican Party politician. He represented Pennsylvania in the United States Senate from 1904 to 1909 and 1917 to 1921. He was the 44th Unit ...

admonished that the United States would not resume diplomatic relations with Nicaragua until Madriz demonstrated that his was a "responsible government ... prepared to make reparations for the wrongs" done to American citizens. His request for asylum granted by Mexico, Zelaya was escorted by armed guard to the Mexican gunboat ''General Guerrero'' and departed Corinto for Salina Cruz, Mexico, on the night of December 23, with ''Albany'' standing by but taking no action.

As the flagship of the Nicaraguan Expeditionary Squadron, under Admiral William W. Kimball, ''Albany'' spent the next five months in Central America, mostly at Corinto, maintaining U.S. neutrality in the ongoing rebellion, sometimes under criticism by the U.S. press and business interests that were displeased by Kimball's "friendly" attitude toward the liberal Madriz administration. By mid-March 1910, the insurgency led by Estrada and Chamorro had seemingly collapsed and with the apparent and unexpected strength of Madriz, the U.S. Nicaraguan Expeditionary Squadron completed its withdrawal from Nicaraguan waters.

On May 27, 1910, U.S. Marine Corps Major Smedley Butler

Smedley Darlington Butler (July 30, 1881June 21, 1940) was a United States Marine Corps officer and writer. During his 34-year military career, he fought in the Philippine–American War, the Boxer Rebellion, the Mexican Revolution, World War I, ...

arrived on the coast of Nicaragua with 250 Marines, for the purpose of providing security in Bluefields. United States Secretary of State

The United States secretary of state (SecState) is a member of the executive branch of the federal government of the United States and the head of the U.S. Department of State.

The secretary of state serves as the principal advisor to the ...

Philander C. Knox

Philander Chase Knox (May 6, 1853October 12, 1921) was an American lawyer, bank director, statesman and Republican Party politician. He represented Pennsylvania in the United States Senate from 1904 to 1909 and 1917 to 1921. He was the 44th Unit ...

condemned Zelaya's actions, favoring Estrada. Zelaya succumbed to U.S. political pressure and fled the country, leaving José Madriz

José Madriz Rodríguez (21 July 1867 – 14 May 1911) was the President of Nicaragua from 21 December 1909 to 20 August 1910.

Madriz was born on 21 July 1867, in León, Nicaragua. He was president of the Nicaraguan Congress 1896, 1896-1905 and ...

as his successor. Madriz in turn had to face an advance by the reinvigorated eastern rebel forces, which ultimately led to his resignation. In August 1910, Juan Estrada became president of Nicaragua with the official recognition of the United States.

Mena's rebellion (1912)

Estrada's administration allowed PresidentWilliam Howard Taft

William Howard Taft (September 15, 1857March 8, 1930) served as the 27th president of the United States from 1909 to 1913 and the tenth chief justice of the United States from 1921 to 1930. He is the only person to have held both offices. ...

and Secretary of State Philander C. Knox

Philander Chase Knox (May 6, 1853October 12, 1921) was an American lawyer, bank director, statesman and Republican Party politician. He represented Pennsylvania in the United States Senate from 1904 to 1909 and 1917 to 1921. He was the 44th Unit ...

to apply the Dollar Diplomacy

Dollar diplomacy of the United States, particularly during the presidency of William Howard Taft (1909–1913) was a form of American foreign policy to minimize the use or threat of military force and instead further its aims in Latin America a ...

or "dollars for bullets" policy. The goal was to undermine European financial strength in the region, which threatened American interests to construct a canal in the isthmus

An isthmus (; : isthmuses or isthmi) is a narrow piece of land connecting two larger areas across an expanse of water by which they are otherwise separated. A tombolo is an isthmus that consists of a spit or bar, and a strait is the sea count ...

, and also to protect American private investment in the development of Nicaragua's natural resources. The policy opened the door for American banks to lend money to the Nicaraguan government, ensuring United States control over the country's finances.

By 1912 the ongoing political conflict in Nicaragua between the liberal and conservative factions had deteriorated to the point that U.S. investments under President Taft's Dollar Diplomacy including substantial loans to the fragile coalition government of conservative President Juan José Estrada

Juan José Estrada Morales (1 January 1872 in Managua – 11 July 1967 in Managua) was the President of Nicaragua from 29 August 1910 to 9 May 1911.

Biography

Juan José Estrada Morales was a Nicaraguan military and political figure who acte ...

were in jeopardy. Minister of War General Luis Mena forced Estrada to resign. He was replaced by his vice president, the conservative Adolfo Díaz

Adolfo Díaz Recinos (15 July 1875 in Alajuela, Costa Rica – 29 January 1964 in San José, Costa Rica) served as the President of Nicaragua between 9 May 1911 and 1 January 1917 and again between 14 November 1926 and 1 January 1929. Born in C ...

.

Díaz's connection with the United States led to a decline in his popularity in Nicaragua. Nationalistic sentiments arose in the Nicaraguan military, including Luis Mena, the Secretary of War. Mena managed to gain the support of the National Assembly, accusing Díaz of "selling out the nation to New York bankers". Díaz asked the U.S. government for help, as Mena's opposition turned into rebellion. Knox appealed to president Taft for military intervention, arguing that the Nicaraguan railway from Corinto to Granada

Granada ( ; ) is the capital city of the province of Granada, in the autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community of Andalusia, Spain. Granada is located at the foot of the Sierra Nevada (Spain), Sierra Nevada mountains, at the confluence ...

was threatened, interfering with U.S. interests.

In mid-1912 Mena persuaded the Nicaraguan national assembly to name him successor to Díaz when Díaz's term expired in 1913. When the United States refused to recognize the Nicaraguan assembly's decision, Mena rebelled against the Díaz government. A force led by liberal General Benjamín Zeledón

Benjamín Francisco Zeledón Rodríguez (October 4, 1879 – October 4, 1912) was a Nicaraguan lawyer, politician and soldier known under the posthumous title of "National Hero of Nicaragua".

He was born on 4 October 1879 in Jinotega Departmen ...

, with its stronghold at Masaya

Masaya () is the capital city of Masaya Department in Nicaragua. It is situated approximately 14 km west of Granada, Nicaragua, Granada and 31 km southeast of Managua. It is located just east of the Masaya Volcano, an active volcano ...

, quickly came to the aid of Mena, whose headquarters

Headquarters (often referred to as HQ) notes the location where most or all of the important functions of an organization are coordinated. The term is used in a wide variety of situations, including private sector corporations, non-profits, mil ...

were at Granada

Granada ( ; ) is the capital city of the province of Granada, in the autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community of Andalusia, Spain. Granada is located at the foot of the Sierra Nevada (Spain), Sierra Nevada mountains, at the confluence ...

.

Díaz, relying on the U.S. government's traditional support of the Nicaraguan conservative faction, made clear that he could not guarantee the safety of U.S. persons and property in Nicaragua and requested U.S. intervention. In the first two weeks of August 1912, Mena and his forces captured steamers on Lakes Managua and Nicaragua

Nicaragua, officially the Republic of Nicaragua, is the geographically largest Sovereign state, country in Central America, comprising . With a population of 7,142,529 as of 2024, it is the third-most populous country in Central America aft ...

that were owned by a railroad company managed by U.S. interests. Insurgents attacked the capital, Managua

Managua () is the capital city, capital and largest city of Nicaragua, and one of the List of largest cities in Central America, largest cities in Central America. Located on the shores of Lake Managua, the city had an estimated population of 1, ...

, subjecting it to a four-hour bombardment. U.S. minister George Wetzel cabled Washington to send U.S. troops to safeguard the U.S. legation

A legation was a diplomatic representative office of lower rank than an embassy. Where an embassy was headed by an ambassador, a legation was headed by a minister. Ambassadors outranked ministers and had precedence at official events. Legation ...

.

At the time the revolution broke out, the Pacific Fleet gunboat was on routine patrol off the west coast of Nicaragua. In the summer of 1912, 100 U.S. Marines

The United States Marine Corps (USMC), also referred to as the United States Marines or simply the Marines, is the maritime land force service branch of the United States Department of Defense. It is responsible for conducting expeditionary ...

arrived aboard the USS ''Annapolis''. They were followed by Smedley Butler

Smedley Darlington Butler (July 30, 1881June 21, 1940) was a United States Marine Corps officer and writer. During his 34-year military career, he fought in the Philippine–American War, the Boxer Rebellion, the Mexican Revolution, World War I, ...

's return from Panama

Panama, officially the Republic of Panama, is a country in Latin America at the southern end of Central America, bordering South America. It is bordered by Costa Rica to the west, Colombia to the southeast, the Caribbean Sea to the north, and ...

with 350 Marines. The commander of the American forces was Admiral

Admiral is one of the highest ranks in many navies. In the Commonwealth nations and the United States, a "full" admiral is equivalent to a "full" general in the army or the air force. Admiral is ranked above vice admiral and below admiral of ...

William Henry Hudson Southerland

William Henry Hudson Southerland (July 10, 1852 – January 30, 1933) was a Rear admiral (United States), rear admiral in the United States Navy. He commanded several ships in Cuban waters during the Spanish–American War, and later served as Co ...

, joined by Colonel Joseph Henry Pendleton and 750 Marines. The main goal was securing the railroad from Corinto to Managua

Managua () is the capital city, capital and largest city of Nicaragua, and one of the List of largest cities in Central America, largest cities in Central America. Located on the shores of Lake Managua, the city had an estimated population of 1, ...

.

1912 occupation

On August 4, at the recommendation of the Nicaraguan president, a landing force of 100 bluejackets was dispatched from ''Annapolis'' to the capital,Managua

Managua () is the capital city, capital and largest city of Nicaragua, and one of the List of largest cities in Central America, largest cities in Central America. Located on the shores of Lake Managua, the city had an estimated population of 1, ...

, to protect American citizens and guard the U.S. legation

A legation was a diplomatic representative office of lower rank than an embassy. Where an embassy was headed by an ambassador, a legation was headed by a minister. Ambassadors outranked ministers and had precedence at official events. Legation ...

during the insurgency. On the east coast of Nicaragua, the (a protected cruiser

Protected cruisers, a type of cruiser of the late 19th century, took their name from the armored deck, which protected vital machine-spaces from fragments released by explosive shells. Protected cruisers notably lacked a belt of armour alon ...

from the American North Atlantic Fleet

The North Atlantic Squadron was a section of the United States Navy operating in the North Atlantic. It was renamed as the North Atlantic Fleet in 1902. In 1905 the European Squadron, European and South Atlantic Squadron, South Atlantic squadr ...

) was ordered to Bluefields, Nicaragua

Bluefields is the capital of the South Caribbean Autonomous Region in Nicaragua. It was also the capital of the former Kingdom of Mosquitia, and later the Zelaya Department, which was divided into North and South Caribbean Coast Autonomous Reg ...

, where she arrived on August 6 and landed a force of 50 men to protect American lives and property. A force of 350 U.S. Marines

The United States Marine Corps (USMC), also referred to as the United States Marines or simply the Marines, is the maritime land force service branch of the United States Department of Defense. It is responsible for conducting expeditionary ...

shipped north on the collier from the Canal Zone

The Panama Canal Zone (), also known as just the Canal Zone, was a concession of the United States located in the Isthmus of Panama that existed from 1903 to 1979. It consisted of the Panama Canal and an area generally extending on each side o ...

and disembarked at Managua to reinforce the legation guard on August 15, 1912. Under this backdrop, ''Denver'' and seven other ships from the Pacific Fleet arrived at Corinto, Nicaragua

Corinto is a town, with a population of 18,602 (2022 estimate), on the northwest Pacific coast of Nicaragua in the province of Chinandega. The municipality was founded in 1863.

History Early years

The town of Corinto was founded in 1849. It first ...

, from late August to September 1912, under the command of Rear Admiral

Rear admiral is a flag officer rank used by English-speaking navies. In most European navies, the equivalent rank is called counter admiral.

Rear admiral is usually immediately senior to commodore and immediately below vice admiral. It is ...

W.H.H. Southerland.

, commanded by Commander

Commander (commonly abbreviated as Cmdr.) is a common naval officer rank as well as a job title in many army, armies. Commander is also used as a rank or title in other formal organizations, including several police forces. In several countri ...

Thomas Washington

Thomas Washington (6 June 1865 – 15 December 1954) was an admiral in the United States Navy during World War I.

Early life and career

Thomas Washington and his brother Richard were twins of Virginia and her farmer husband R.A. Washington, both ...

arrived at Corinto on August 27, 1912, with 350 navy bluejackets and Marines

Marines (or naval infantry) are military personnel generally trained to operate on both land and sea, with a particular focus on amphibious warfare. Historically, the main tasks undertaken by marines have included Raid (military), raiding ashor ...

on board. Admiral Southerland's priorities were to re-establish and safeguard the disrupted railway and cable lines between the principal port of Corinto and Managua, to the southeast.

On August 29, 1912, a landing force of 120 men from USS ''Denver'', under the command of the ship's navigator, Lieutenant Allen B. Reed, landed at Corinto to protect the railway line running from Corinto to Managua and then south to Granada on the north shore of Lake Nicaragua. This landing party reembarked aboard ship October 24 and 25, 1912. One officer and 24 men were landed from the ''Denver'' at

On August 29, 1912, a landing force of 120 men from USS ''Denver'', under the command of the ship's navigator, Lieutenant Allen B. Reed, landed at Corinto to protect the railway line running from Corinto to Managua and then south to Granada on the north shore of Lake Nicaragua. This landing party reembarked aboard ship October 24 and 25, 1912. One officer and 24 men were landed from the ''Denver'' at San Juan del Sur

San Juan del Sur is a municipality and coastal town on the Pacific Ocean, in the Rivas department in southwest Nicaragua. It is located south of Managua. San Juan del Sur is popular among surfers and is a vacation spot for many Nicaraguan fam ...

on the southern end of the Nicaraguan isthmus

An isthmus (; : isthmuses or isthmi) is a narrow piece of land connecting two larger areas across an expanse of water by which they are otherwise separated. A tombolo is an isthmus that consists of a spit or bar, and a strait is the sea count ...

from August 30 to September 6, 1912, and from September 11 to 27, 1912 to protect the cable station, custom house

A custom house or customs house was traditionally a building housing the offices for a jurisdictional government whose officials oversaw the functions associated with importing and exporting goods into and out of a country, such as collecting ...

and American interests. ''Denver'' remained at San Juan del Sur to relay wireless

Wireless communication (or just wireless, when the context allows) is the transfer of information (''telecommunication'') between two or more points without the use of an electrical conductor, optical fiber or other continuous guided transm ...

messages from the other navy ships to and from Washington until departing on September 30, for patrol duty.

On the morning of September 22, two battalions of Marines and an artillery battery under Major Smedley Butler

Smedley Darlington Butler (July 30, 1881June 21, 1940) was a United States Marine Corps officer and writer. During his 34-year military career, he fought in the Philippine–American War, the Boxer Rebellion, the Mexican Revolution, World War I, ...

, U.S.M.C.

The United States Marine Corps (USMC), also referred to as the United States Marines or simply the Marines, is the maritime land force service branch of the United States Department of Defense. It is responsible for conducting expeditionary ...

had entered Granada, Nicaragua

Granada () is a city in western Nicaragua and the capital of the Granada Department. With an estimated population of 105,862 (2022), it is Nicaragua's ninth most populous city. Granada is historically one of Nicaragua's most important cities, econ ...

(after being ambushed by rebels at Masaya on the nineteenth), where they were reinforced with the Marine first battalion commanded by Colonel Joseph H. Pendleton

Major General Joseph Henry Pendleton (June 2, 1860 – February 4, 1942) was a United States Marine Corps general for whom Marine Corps Base Camp Pendleton is named. Pendleton served in the Marine Corps for over 40 years.

Biography

Joseph Hen ...

, U.S.M.C.

The United States Marine Corps (USMC), also referred to as the United States Marines or simply the Marines, is the maritime land force service branch of the United States Department of Defense. It is responsible for conducting expeditionary ...

General Mena, the primary instigator of the failed coup d'etat surrendered his 700 troops to Southerland and was deported to Panama

Panama, officially the Republic of Panama, is a country in Latin America at the southern end of Central America, bordering South America. It is bordered by Costa Rica to the west, Colombia to the southeast, the Caribbean Sea to the north, and ...

. Beginning on the morning of September 27 and continuing through October 1, Nicaraguan government forces bombarded Barranca and Coyotepe, two hills overlooking the all-important railway line at Masaya that Zeledón and about 550 of his men occupied, halfway between Managua and Granada.

On October 2, Nicaraguan government troops loyal to President Diaz delivered a surrender ultimatum to Zelaydón, who refused. Rear Admiral Southerland realized that Nicaraguan government forces would not vanquish the insurgents by bombardment or infantry assault, and ordered the Marine commanders to prepare to take the hills.

On October 3, Butler and his men, returning from the capture of Granada, pounded the hills with artillery throughout the day, with no response from the insurgents. In the pre-dawn hours of October 4, Butler's 250 Marines began moving up the higher hill, Coyotepe, to converge with Pendletons's 600 Marines and a landing battalion of bluejackets from ''California''. At the summit, the American forces seized the rebel's artillery and used it to rout Zeledón's troops on Barranca across the valley.

Zeledón and most of his troops had fled the previous day during the bombardment, many to Masaya, where Nicaraguan government troops captured or killed most of them, including Zeledón. With the insurgents driven from Masaya, Southerland ordered the occupation of Leon to stop any further interference with the U.S.-controlled railroad. On October 6, 1,000 bluejackets and Marines, from the cruisers , , and ''Denver'' led by Lieutenant Colonel Charles G. Long, U.S.M.C. captured the city of Leon, Nicaragua, the last stronghold of the insurgency. The revolution of General Diaz was essentially over.

On October 23, Southerland announced that but for the Nicaraguan elections in early November, he would withdraw most of the U.S. landing forces. At that point, peaceful conditions prevailed and nearly all of the embarked U.S. Marines and bluejackets that had numbered approximately 2,350 at their peak, not including approximately 1,000 shipboard sailors, withdrew, leaving a legation guard of 100 Marines in Managua.

Of the 1,100 members of the United States military that intervened in Nicaragua, thirty-seven were killed in action. With Díaz safely in the presidency of the country, the United States proceeded to withdraw the majority of its forces from Nicaraguan territory, leaving one hundred Marines to "protect the American legation in Managua".

The Knox-Castrillo Treaty of 1911, ratified in 1912, put the U.S. in charge of much of Nicaragua's financial system.

In 1916, General Emiliano Chamorro Vargas

Emiliano Chamorro Vargas (11 May 1871 – 26 February 1966) was a Nicaraguan military figure and politician who served as President of Nicaragua from 1 January 1917 to 1 January 1921. He was a member of the Conservative Party.

He lost the 192 ...

, a Conservative, assumed the presidency, and continued to attract foreign investment. Some Marines remained in the country after the intervention, occasionally clashing with local residents. In 1921, a group of Marines who raided a Managua newspaper office were dishonorably discharged. Later that year, a Marine private shot and killed a Nicaraguan policeman.

1927 occupation

Civil war erupted between the conservative and liberal factions on May 2, 1926, with liberals capturingBluefields

Bluefields is the capital of the South Caribbean Autonomous Region in Nicaragua. It was also the capital of the former Kingdom of Mosquitia, and later the Zelaya Department, which was divided into North and South Caribbean Coast Autonomous Reg ...

, and José María Moncada Tapia

José is a predominantly Spanish and Portuguese form of the given name Joseph. While spelled alike, this name is pronounced very differently in each of the two languages: Spanish ; Portuguese (or ).

In French, the name ''José'', pronounced , ...

capturing Puerto Cabezas

Puerto Cabezas (; also known as Bragman's Bluff in English language, English, or Bilwi in Miskito language, Miskito) is a municipality and city in Nicaragua. It is the capital of Miskito people, Miskito nation in the North Caribbean Coast Autonom ...

in August. On May 7, 1926, a U.S. Navy landing force, consisting of 213 officers and men, was landed from the USS ''Cleveland'' (C-19) at Bluefields to protect Americans and U.S. interests. Juan Bautista Sacasa

Juan Bautista Sacasa (21 December 1874 in León, Nicaragua – 17 April 1946 in Los Angeles, California) was the President of Nicaragua from 1 January 1933 to 9 June 1936. He was the eldest son of Roberto Sacasa and Ángela Sacasa Cuadra, the fo ...

declared himself Constitutional President of Nicaragua from Puerto Cabezas on December 1, 1926. Following Emiliano Chamorro Vargas

Emiliano Chamorro Vargas (11 May 1871 – 26 February 1966) was a Nicaraguan military figure and politician who served as President of Nicaragua from 1 January 1917 to 1 January 1921. He was a member of the Conservative Party.

He lost the 192 ...

' resignation, the Nicaraguan Congress selected Adolfo Diaz Adolfo may refer to:

* Adolfo, São Paulo, a Brazilian municipality

* Adolfo (designer)

Adolfo Faustino Sardiña (February 15, 1923 – November 27, 2021), professionally known as Adolfo, was a Cuban-born American fashion designer who started out a ...

as ''designado'', who then requested intervention from President Calvin Coolidge

Calvin Coolidge (born John Calvin Coolidge Jr.; ; July 4, 1872January 5, 1933) was the 30th president of the United States, serving from 1923 to 1929. A Republican Party (United States), Republican lawyer from Massachusetts, he previously ...

. On January 24, 1927, the first elements of U.S. forces arrived, with 400 Marines.

Government forces were defeated on February 6 at Chinandega

Chinandega () is a city and the departmental seat of Chinandega department in Nicaragua. It is also the administrative centre of the surrounding municipality of the same name. It is Nicaragua's 2nd most important city (economy) and 6th largest ...

, followed by another defeat at Muy Muy

Muy Muy is a municipality in the Matagalpa department of Nicaragua.

The municipality of Muy Muy was named by the Matagalpa people, who were the indigenous group native to the area. In their native language

A first language (L1), native ...

, prompting U.S. Marine landings at Corinto and the occupation of La Loma Fort in Managua. Ross E. Rowell

Ross Erastus Rowell (September 22, 1884 – September 6, 1947) was a highly decorated United States Marine Corps aviator who served as the Marine Corps' Director of Aviation from May 30, 1935, until March 10, 1939, and was one of the three senior ...

's Observation Squadron arrived on February 26, which included DeHavilland DH-4

The Airco DH.4 is a British two-seat biplane day bomber of the First World War. It was designed by Geoffrey de Havilland (hence "DH") for Airco, and was the first British two-seat light day-bomber capable of defending itself.

It was desig ...

s. By March, the U.S. had 2,000 troops in Nicaragua under the command of General Logan Feland

Major General Logan Feland (18 August 1869 – 17 July 1936) was a United States Marine Corps general who last served as commanding general of the Department of the Pacific. Feland served during the Spanish–American War (3rd Kentucky Volunte ...

. In May, Henry Stimson

Henry Lewis Stimson (September 21, 1867 – October 20, 1950) was an American statesman, lawyer, and Republican Party politician. Over his long career, he emerged as a leading figure in U.S. foreign policy by serving in both Republican and Demo ...

brokered a peace deal which included disarmament and promised elections in 1928. However, the Liberal commander Augusto César Sandino

Augusto César Sandino (; 18 May 1895 21 February 1934), full name Augusto Nicolás Calderón Sandino, was a Nicaraguan revolutionary, founder of the militant group EDSN, and leader of a rebellion between 1927 and 1933 against the United Sta ...

, and 200 of his men refused to give up the revolution.

On June 30, Sandino seized the San Albino gold mine, denounced the Conservative government, and attracted recruits to continue operations. The next month saw the Battle of Ocotal

The Battle of Ocotal occurred in July 1927, during the American occupation of Nicaragua.

A large force of rebels loyal to Augusto César Sandino attacked the garrison of Ocotal, which was held by a small group of US Marines and Nicaraguan Natio ...

. Despite additional conflict with Sandino's rebels, U.S.-supervised elections were held on November 4, 1928, with Moncada the winner. Manuel Giron was captured and executed in February 1929, and Sandino took a year's leave in Mexico. By 1930, Sandino's guerrilla forces numbered more than 5,000 men.

The only American journalist who interviewed Sandino during this occupation was Carleton Beals

Carleton Beals (November 13, 1893 – April 4, 1979) was an American journalist, writer, historian, and political activist with a special interest in Latin America. A major journalistic coup for him was his interview with the Nicaraguan rebel Au ...

of ''The Nation

''The Nation'' is a progressive American monthly magazine that covers political and cultural news, opinion, and analysis. It was founded on July 6, 1865, as a successor to William Lloyd Garrison's '' The Liberator'', an abolitionist newspaper ...

''.

Calvin Coolidge

Calvin Coolidge (born John Calvin Coolidge Jr.; ; July 4, 1872January 5, 1933) was the 30th president of the United States, serving from 1923 to 1929. A Republican Party (United States), Republican lawyer from Massachusetts, he previously ...

sent U.S. Marines to Nicaragua, who were withdrawn shortly after Stimson announced their immediate withdrawal on the 14th of February 1931. The Hoover administration started a U.S. pullout such that by February 1932, only 745 men remained. Juan Sacasa was elected president in the November 6, 1932, election.

The Battle of El Sauce

The Battle of El Sauce, or the Battle of Punta de Rieles or Punta Rieles, took place on the 26 December 1932 during the American occupation of Nicaragua of 1926–1933. It was the last major battle of the Sandino Rebellion of 1927–1933. The in ...

was the last major engagement of the U.S. intervention.

See also

*American imperialism

U.S. imperialism or American imperialism is the expansion of political, economic, cultural, media, and military influence beyond the boundaries of the United States. Depending on the commentator, it may include imperialism through outright mi ...

* History of Nicaragua

Nicaragua is a nation in Central America. It is located about midway between Mexico and Colombia, bordered by Honduras to the north and Costa Rica to the south. Nicaragua ranges from the Caribbean Sea on the nation's east coast, and the Pacific Oc ...

* Nicaraguan Campaign Medal

The Nicaraguan Campaign Medal is a Awards and decorations of the United States military, campaign medal of the United States Navy which was authorized by Presidential Order of Woodrow Wilson on September 22, 1913. A later medal, the Second Nicara ...

* Overseas interventions of the United States

Overseas may refer to:

*Diaspora, a scattered population whose origin lies in a separate locale

*Expatriate, a person residing in a country other than their native country

** Overseas Chinese

** Overseas Citizenship of India

** Overseas Filipinos

...

* Second Nicaraguan Campaign Medal

The Second Nicaraguan Campaign Medal is a Awards and decorations of the United States military, campaign medal of the United States Navy which was authorized by an act of the United States Congress on 8 November 1929. The Second Nicaraguan Campaig ...

* United States involvement in regime change

Since the 19th century, the United States government has participated and interfered, both overtly and covertly, in the replacement of many foreign governments. In the latter half of the 19th century, the U.S. government initiated actions for ...

* United States-Latin American relations

United may refer to:

Places

* United, Pennsylvania, an unincorporated community

* United, West Virginia, an unincorporated community

Arts and entertainment Films

* ''United'' (2003 film), a Norwegian film

* ''United'' (2011 film), a BBC Two fi ...

* Nicaragua v. United States

''The Republic of Nicaragua v. The United States of America'' (1986) was a case where the International Court of Justice (ICJ) held that the U.S. had violated Public international law, international law by United States and state-sponsored terro ...

* Nicaragua–United States relations

References

External links

Nicaragua 8 1850–1868

Sandino rebellion 1927–1934

{{coord, 13.0000, N, 85.0000, W, source:wikidata, display=title * Conflicts in 1912 1910s in Nicaragua

Nicaragua

Nicaragua, officially the Republic of Nicaragua, is the geographically largest Sovereign state, country in Central America, comprising . With a population of 7,142,529 as of 2024, it is the third-most populous country in Central America aft ...

Nicaragua

Nicaragua, officially the Republic of Nicaragua, is the geographically largest Sovereign state, country in Central America, comprising . With a population of 7,142,529 as of 2024, it is the third-most populous country in Central America aft ...

American imperialism

Military history of Nicaragua

United States Marine Corps in the 20th century

Wars involving Nicaragua

Nicaragua

Nicaragua, officially the Republic of Nicaragua, is the geographically largest Sovereign state, country in Central America, comprising . With a population of 7,142,529 as of 2024, it is the third-most populous country in Central America aft ...

Nicaragua–United States military relations

1920s in Nicaragua

1930s in Nicaragua

United States involvement in regime change