Sahle Selassie on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Sahle Selassie (

On the other hand, he continued the policy of his ancestor Amha Iyasus in maintaining a buffer region to his north, created from the Yejju and Wollo Oromo rulers in the area. This helped keep Shewa out of the reach of the northern lords like Ras Ali II of Yejju, who continued their own civil wars.

After a few years, Sahle Selassie felt his position secure enough that he proclaimed himself ''Negus'', or king, of Shewa, Ifat, the Oromo and the Gurage peoples, without the authority of the Emperor of Ethiopia in Gondar, but with his apparent acquiescence. However, in 1829 Shewa suffered a

On the other hand, he continued the policy of his ancestor Amha Iyasus in maintaining a buffer region to his north, created from the Yejju and Wollo Oromo rulers in the area. This helped keep Shewa out of the reach of the northern lords like Ras Ali II of Yejju, who continued their own civil wars.

After a few years, Sahle Selassie felt his position secure enough that he proclaimed himself ''Negus'', or king, of Shewa, Ifat, the Oromo and the Gurage peoples, without the authority of the Emperor of Ethiopia in Gondar, but with his apparent acquiescence. However, in 1829 Shewa suffered a

Despite his many reverses against his political rivals inside Shewa and out, considered against any other period of history, Negus Sahle Selassie was a progressive and benevolent ruler. A contemporary British visitor, Dr Charles Johnston, commented that the:

: ...contemplation of such a prince in his own land is worth the trouble and the risk of visiting it ... his character for justice and probity has spread far and wide, and the supremacy of political excellence is without hesitation given to the Negoos egusof Shoa throughout the length and breadth of the ancient empire of Ethiopia. To be feared by every prince around, and loved by every subject at home, is the boast of the first government of civilized Europe, and strangely enough this excellence of social condition is paralleled in the heart of Africa, where we find practically carried out the most advantageous policy of a social community that one of the wisest of sages could conceive – that of arbitrary power placed in the hands of a really good man.

Abir provides several examples of Sahle Selassie's interest in the well-being of his subjects:

: In time of famine he opened the royal granaries to the population. When a plague carried off most of the work-animals of the farmers, he distributed oxen and mules. He kept enormous stores of salt so that his people would not lack this important commodity should the roads to the coast be cut.

After a few years, Sahle Selassie felt his position secure enough that he proclaimed himself ''Negus'', or king, of Shewa, Ifat, the Oromo and the Gurage peoples, without the authority of the Emperor of Ethiopia in Gondar, but with his apparent acquiescence. However, in 1829 Shewa suffered a

Despite his many reverses against his political rivals inside Shewa and out, considered against any other period of history, Negus Sahle Selassie was a progressive and benevolent ruler. A contemporary British visitor, Dr Charles Johnston, commented that the:

: ...contemplation of such a prince in his own land is worth the trouble and the risk of visiting it ... his character for justice and probity has spread far and wide, and the supremacy of political excellence is without hesitation given to the Negoos egusof Shoa throughout the length and breadth of the ancient empire of Ethiopia. To be feared by every prince around, and loved by every subject at home, is the boast of the first government of civilized Europe, and strangely enough this excellence of social condition is paralleled in the heart of Africa, where we find practically carried out the most advantageous policy of a social community that one of the wisest of sages could conceive – that of arbitrary power placed in the hands of a really good man.

Abir provides several examples of Sahle Selassie's interest in the well-being of his subjects:

: In time of famine he opened the royal granaries to the population. When a plague carried off most of the work-animals of the farmers, he distributed oxen and mules. He kept enormous stores of salt so that his people would not lack this important commodity should the roads to the coast be cut.

After a few years, Sahle Selassie felt his position secure enough that he proclaimed himself ''Negus'', or king, of Shewa, Ifat, the Oromo and the Gurage peoples, without the authority of the Emperor of Ethiopia in Gondar, but with his apparent acquiescence. However, in 1829 Shewa suffered a  Sahle Selassie also worked to modernize his country, and like his contemporaries Goshu of

Sahle Selassie also worked to modernize his country, and like his contemporaries Goshu of

Amharic

Amharic is an Ethio-Semitic language, which is a subgrouping within the Semitic branch of the Afroasiatic languages. It is spoken as a first language by the Amhara people, and also serves as a lingua franca for all other metropolitan populati ...

: ሣህለ ሥላሴ, 1795 – 22 October 1847) was the King

King is a royal title given to a male monarch. A king is an Absolute monarchy, absolute monarch if he holds unrestricted Government, governmental power or exercises full sovereignty over a nation. Conversely, he is a Constitutional monarchy, ...

of Shewa

Shewa (; ; Somali: Shawa; , ), formerly romanized as Shua, Shoa, Showa, Shuwa, is a historical region of Ethiopia which was formerly an autonomous kingdom within the Ethiopian Empire. The modern Ethiopian capital Addis Ababa is located at it ...

from 1813 to 1847. An important Amhara noble of Ethiopia

Ethiopia, officially the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, is a landlocked country located in the Horn of Africa region of East Africa. It shares borders with Eritrea to the north, Djibouti to the northeast, Somalia to the east, Ken ...

, he was a younger son of Wossen Seged

Wossen Seged (ruled c. 1808 – June 1813) was a ''Ethiopian aristocratic and court titles#Important regional offices, Merid Azmach'' of Shewa, an Amhara people, Amhara noble of Ethiopia. He was the elder son of Asfaw Wossen (ruler of Shewa), ...

. Sahle Selassie was the father of numerous sons, among them Haile Melekot, Haile Mikael, Seyfe Sahle Selassie, Amarkegne and Darge Sahle Selassie; his daughters included Tenagnework, Ayahilush, Wossenyelesh, Birkinesh, and Tinfelesh. He was the great-grandfather of Haile Selassie

Haile Selassie I (born Tafari Makonnen or ''Ethiopian aristocratic and court titles#Lij, Lij'' Tafari; 23 July 189227 August 1975) was Emperor of Ethiopia from 1930 to 1974. He rose to power as the Ethiopian aristocratic and court titles, Rege ...

, the last Emperor of Ethiopia

The emperor of Ethiopia (, "King of Kings"), also known as the Atse (, "emperor"), was the hereditary monarchy, hereditary ruler of the Ethiopian Empire, from at least the 13th century until the abolition of the monarchy in 1975. The emperor w ...

.

Biography

When their father had been murdered, Oromo rebels in Marra Biete kept Sahle Selassie's older brother Bakure from promptly marching to their father's capital at Qundi to claim the succession. Although still a teenager, Sahle Selassie seized this chance at rule by rushing from the monastery at Sela Dingay where he was a student "and probably with the support of his mother Zenebework'sMenz

Menz or Manz (, romanized: ''Mänz'') is a former Subdivisions of Ethiopia, subdivision of Ethiopia, located inside the boundaries of the modern Semien Shewa Zone (Amhara), Semien Shewa Zone of the Amhara Region. William Cornwallis Harris describe ...

ian kinsmen was proclaimed the '' Ras'' and Meridazmach of Shewa." Bakure belatedly arrived at Qundi only to be imprisoned in the state prison at Gonchu with his other brothers and some of his supporters.

Once securely in control, Sahle Selassie turned his attention to the rebels. He used diplomacy to win over the Abichu Oromo, who badly needed his help against their neighbors the Tulama Oromo, whom he defeated in the early 1820s. He followed this victory by rebuilding Debre Berhan, which had been burned in an Oromo raid, as well as a number of other towns and consolidated his hold by founding a number of fortified villages, like Angolalla. He extended the frontier of Shewa into Bulga and Karayu, to the southeast into Arsi, and as far south as the territories of the Gurage.

On the other hand, he continued the policy of his ancestor Amha Iyasus in maintaining a buffer region to his north, created from the Yejju and Wollo Oromo rulers in the area. This helped keep Shewa out of the reach of the northern lords like Ras Ali II of Yejju, who continued their own civil wars.

After a few years, Sahle Selassie felt his position secure enough that he proclaimed himself ''Negus'', or king, of Shewa, Ifat, the Oromo and the Gurage peoples, without the authority of the Emperor of Ethiopia in Gondar, but with his apparent acquiescence. However, in 1829 Shewa suffered a

On the other hand, he continued the policy of his ancestor Amha Iyasus in maintaining a buffer region to his north, created from the Yejju and Wollo Oromo rulers in the area. This helped keep Shewa out of the reach of the northern lords like Ras Ali II of Yejju, who continued their own civil wars.

After a few years, Sahle Selassie felt his position secure enough that he proclaimed himself ''Negus'', or king, of Shewa, Ifat, the Oromo and the Gurage peoples, without the authority of the Emperor of Ethiopia in Gondar, but with his apparent acquiescence. However, in 1829 Shewa suffered a famine

A famine is a widespread scarcity of food caused by several possible factors, including, but not limited to war, natural disasters, crop failure, widespread poverty, an Financial crisis, economic catastrophe or government policies. This phenom ...

, then for two years, starting in 1830, was stricken by a cholera

Cholera () is an infection of the small intestine by some Strain (biology), strains of the Bacteria, bacterium ''Vibrio cholerae''. Symptoms may range from none, to mild, to severe. The classic symptom is large amounts of watery diarrhea last ...

epidemic, where two thirds of the sick at Sahle Selassie's palace died. Then one of Sahle Selassie's generals, Medoko, rebelled and convinced a number of the elite Shewan matchlock

A matchlock or firelock is a historical type of firearm wherein the gunpowder is ignited by a burning piece of flammable cord or twine that is in contact with the gunpowder through a mechanism that the musketeer activates by pulling a lever or Tri ...

men to desert with him to join the Oromos. Together these adversaries threatened the existence of Shewa and burned Angolalla. About the time Sahle Selassie put down this rebellion in 1834 or 1835, a drought afflicted Shewa for two years, killing most of the domestic animals and bringing famine to his people. Pankhurst also documents records of a second cholera epidemic in 1834, which spread south from Welo causing a great mortality. Sahle Selassie responded to the famine by opening the royal storehouses to the needy, endearing himself to his people. The famine came to an end in time for Medoko to rise again in rebellion, and although the general was quickly crushed, Sahle Selassie was then confronted by a crisis in the local church.

A governor from Harar

Harar (; Harari language, Harari: ሀረር / ; ; ; ), known historically by the indigenous as Harar-Gey or simply Gey (Harari: ጌይ, ݘٛىيْ, ''Gēy'', ), is a List of cities with defensive walls, walled city in eastern Ethiopia. It is al ...

was permitted to administer the Abyssinian town of Aliyu Amba, suggesting that Sahle Selassie had cordial commercial ties with the rulers of the nearby Muslim state Emirate of Harar

The Emirate of Harar was a Muslim kingdom founded in 1647 when the Harari people refused to accept Imām ʿUmardīn Ādam as their ruler and broke away from the Imamate of Aussa to form their own state under `Ali ibn Da`ud.

The Harar, city of Ha ...

.

During the ongoing dispute over Christology

In Christianity, Christology is a branch of Christian theology, theology that concerns Jesus. Different denominations have different opinions on questions such as whether Jesus was human, divine, or both, and as a messiah what his role would b ...

that had split the Ethiopian Church into a number of hostile factions, Shewa had embraced the doctrine of the '' Sost Lidet'' in opposition to the theory of ''Wold Qib'', which was embraced in the north. The ''Sost Lidet'' was also embraced by the influential monastery of Debre Libanos

Debre Libanos () is an Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church, Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo monastery, lying northwest of Addis Ababa in the North Shewa Zone (Oromia), North Shewa Zone of the Oromia Region. It was founded in 1284 by Saint Tekle Hay ...

, located in Shewa. When Sahle Selassie sought to strengthen his power over the Shewan church by appointing men loyal to himself as trusties of the local monasteries—an act that brought the opposition not only of the monks themselves, but also of the Ichege, the abbot of the monastery of Debre Libanos and the second most powerful churchman in Ethiopia. Facing the threat of excommunication

Excommunication is an institutional act of religious censure used to deprive, suspend, or limit membership in a religious community or to restrict certain rights within it, in particular those of being in Koinonia, communion with other members o ...

, Sahle Selassie relented and on 24 November 1841 dismissed his appointees—only to find himself under attack by Shewan supporters of the ''Wold Qib'' in Menz

Menz or Manz (, romanized: ''Mänz'') is a former Subdivisions of Ethiopia, subdivision of Ethiopia, located inside the boundaries of the modern Semien Shewa Zone (Amhara), Semien Shewa Zone of the Amhara Region. William Cornwallis Harris describe ...

, Marra Biete, and other districts. At the moment the monarch managed to quiet this controversy, the arrival of a new Abuna

Abuna (or Abune, which is the status constructus form used when a name follows: Ge'ez አቡነ ''abuna''/''abune'', 'our father'; Amharic and Tigrinya) is the honorific title used for any bishop of the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church as w ...

, Salama III reawoke the resistance of the followers of the ''Wold Qib'', and the new Abuna excommunicated Sahle Selassie in 1845. Despite the intervention of Imperial Regent, Ras Ali II, Abuna Salama refused to lift the interdict, and Ras Ali finally arrested the Abuna in 1846 and banished him from Gondar

Gondar, also spelled Gonder (Amharic: ጎንደር, ''Gonder'' or ''Gondär''; formerly , ''Gʷandar'' or ''Gʷender''), is a city and woreda in Ethiopia. Located in the North Gondar Zone of the Amhara Region, Gondar is north of Lake Tana on ...

.

By this time, Sahle Selassie's health had begun to fail, and he was unable to pursue his intentions on the Imperial throne. Only the intervention of his close friends and advisers kept the Negus from abdicating the throne in favor of his son, and the final years of his reign are otherwise unremarkable. He died in 1847 in Debre Birhan.

Achievements as ruler of Shewa

Despite his many reverses against his political rivals inside Shewa and out, considered against any other period of history, Negus Sahle Selassie was a progressive and benevolent ruler. A contemporary British visitor, Dr Charles Johnston, commented that the:

: ...contemplation of such a prince in his own land is worth the trouble and the risk of visiting it ... his character for justice and probity has spread far and wide, and the supremacy of political excellence is without hesitation given to the Negoos egusof Shoa throughout the length and breadth of the ancient empire of Ethiopia. To be feared by every prince around, and loved by every subject at home, is the boast of the first government of civilized Europe, and strangely enough this excellence of social condition is paralleled in the heart of Africa, where we find practically carried out the most advantageous policy of a social community that one of the wisest of sages could conceive – that of arbitrary power placed in the hands of a really good man.

Abir provides several examples of Sahle Selassie's interest in the well-being of his subjects:

: In time of famine he opened the royal granaries to the population. When a plague carried off most of the work-animals of the farmers, he distributed oxen and mules. He kept enormous stores of salt so that his people would not lack this important commodity should the roads to the coast be cut.

After a few years, Sahle Selassie felt his position secure enough that he proclaimed himself ''Negus'', or king, of Shewa, Ifat, the Oromo and the Gurage peoples, without the authority of the Emperor of Ethiopia in Gondar, but with his apparent acquiescence. However, in 1829 Shewa suffered a

Despite his many reverses against his political rivals inside Shewa and out, considered against any other period of history, Negus Sahle Selassie was a progressive and benevolent ruler. A contemporary British visitor, Dr Charles Johnston, commented that the:

: ...contemplation of such a prince in his own land is worth the trouble and the risk of visiting it ... his character for justice and probity has spread far and wide, and the supremacy of political excellence is without hesitation given to the Negoos egusof Shoa throughout the length and breadth of the ancient empire of Ethiopia. To be feared by every prince around, and loved by every subject at home, is the boast of the first government of civilized Europe, and strangely enough this excellence of social condition is paralleled in the heart of Africa, where we find practically carried out the most advantageous policy of a social community that one of the wisest of sages could conceive – that of arbitrary power placed in the hands of a really good man.

Abir provides several examples of Sahle Selassie's interest in the well-being of his subjects:

: In time of famine he opened the royal granaries to the population. When a plague carried off most of the work-animals of the farmers, he distributed oxen and mules. He kept enormous stores of salt so that his people would not lack this important commodity should the roads to the coast be cut.

After a few years, Sahle Selassie felt his position secure enough that he proclaimed himself ''Negus'', or king, of Shewa, Ifat, the Oromo and the Gurage peoples, without the authority of the Emperor of Ethiopia in Gondar, but with his apparent acquiescence. However, in 1829 Shewa suffered a famine

A famine is a widespread scarcity of food caused by several possible factors, including, but not limited to war, natural disasters, crop failure, widespread poverty, an Financial crisis, economic catastrophe or government policies. This phenom ...

, then for two years, starting in 1830, was stricken by a cholera

Cholera () is an infection of the small intestine by some Strain (biology), strains of the Bacteria, bacterium ''Vibrio cholerae''. Symptoms may range from none, to mild, to severe. The classic symptom is large amounts of watery diarrhea last ...

epidemic, where two thirds of the sick at Sahle Selassie's palace died. Then one of Sahle Selassie's generals, Medoko, rebelled and convinced a number of the elite Shewan matchlock

A matchlock or firelock is a historical type of firearm wherein the gunpowder is ignited by a burning piece of flammable cord or twine that is in contact with the gunpowder through a mechanism that the musketeer activates by pulling a lever or Tri ...

men to desert with him to join the Oromos. Together these adversaries threatened the existence of Shewa and burned Angolalla. About the time Sahle Selassie put down this rebellion in 1834 or 1835, a drought afflicted Shewa for two years, killing most of the domestic animals and bringing famine to his people. Pankhurst also documents records of a second cholera epidemic in 1834, which spread south from Welo causing a great mortality. Sahle Selassie responded to the famine by opening the royal storehouses to the needy, endearing himself to his people. The famine came to an end in time for Medoko to rise again in rebellion, and although the general was quickly crushed, Sahle Selassie was then confronted by a crisis in the local church.

Further examples of Sahle Selassie's skill in administration is his reform of the laws of his domain. Courts during the reign of his predecessors Asfa Wossen and Wossen Seged followed both the ''Fetha Negest

The Fetha Negest () is a theocratic legal code compiled around 1240 by the Coptic Egyptian Christian writer Abu'l-Fada'il ibn al-Assal in Arabic. It was later translated into Ge'ez in Ethiopia in the 15th century and expanded upon with numerous ...

'', the traditional Ethiopian legal code, as well as customary practices, which Abir states "was extremely cruel. Death sentences, severance of limbs and branding with hot iron were very common." The Negus limited executions to extreme cases of treason, sacrilege and murder, and even then, required approval from the Negus. Whenever possible, Sahle Selassie reduced a death sentence to life imprisonment or forfeiture of property; in the case of a murder conviction, where the traditional Ethiopian penalty was to hand the murderer over to the relatives of the victim, who would then exact their own punishment, the Negus worked to convince the relatives to accept blood money instead of killing the convicted man.

His reforms extended beyond criminal law and included administrative reforms. He developed a new structure of taxation

A tax is a mandatory financial charge or levy imposed on an individual or legal person, legal entity by a governmental organization to support government spending and public expenditures collectively or to Pigouvian tax, regulate and reduce nega ...

that was not only fairer to his subjects but brought in a more substantial and reliable revenue; it is estimated that around 1840 his revenue in cash alone was between 80,000 and 300,000 Maria Theresa Thaler

The Maria Theresa thaler (MTT) is a silver bullion coin and a type of Conventionsthaler that has been used in world trade continuously since it was first minted in 1741. It is named after Maria Theresa who ruled Austria, Hungary, Croatia and ...

s. Legends circulated in Shewa about the storehouses of gold, silver, and ivory the Negus had not only in his palaces in Doqaqit, Har Ambit and Ankober

Ankober (), formerly known as Ankobar, is a town in central Ethiopia. Located in the North Shewa Zone (Amhara), North Shewa Zone of the Amhara Region, it's perched on the eastern escarpment of the Ethiopian Highlands at an elevation of about . ...

, but also hidden in mountain caves. "All in all," concludes Abir, "Showa can be considered, in a way, an archaic example of a welfare state

A welfare state is a form of government in which the State (polity), state (or a well-established network of social institutions) protects and promotes the economic and social well-being of its citizens, based upon the principles of equal oppor ...

."

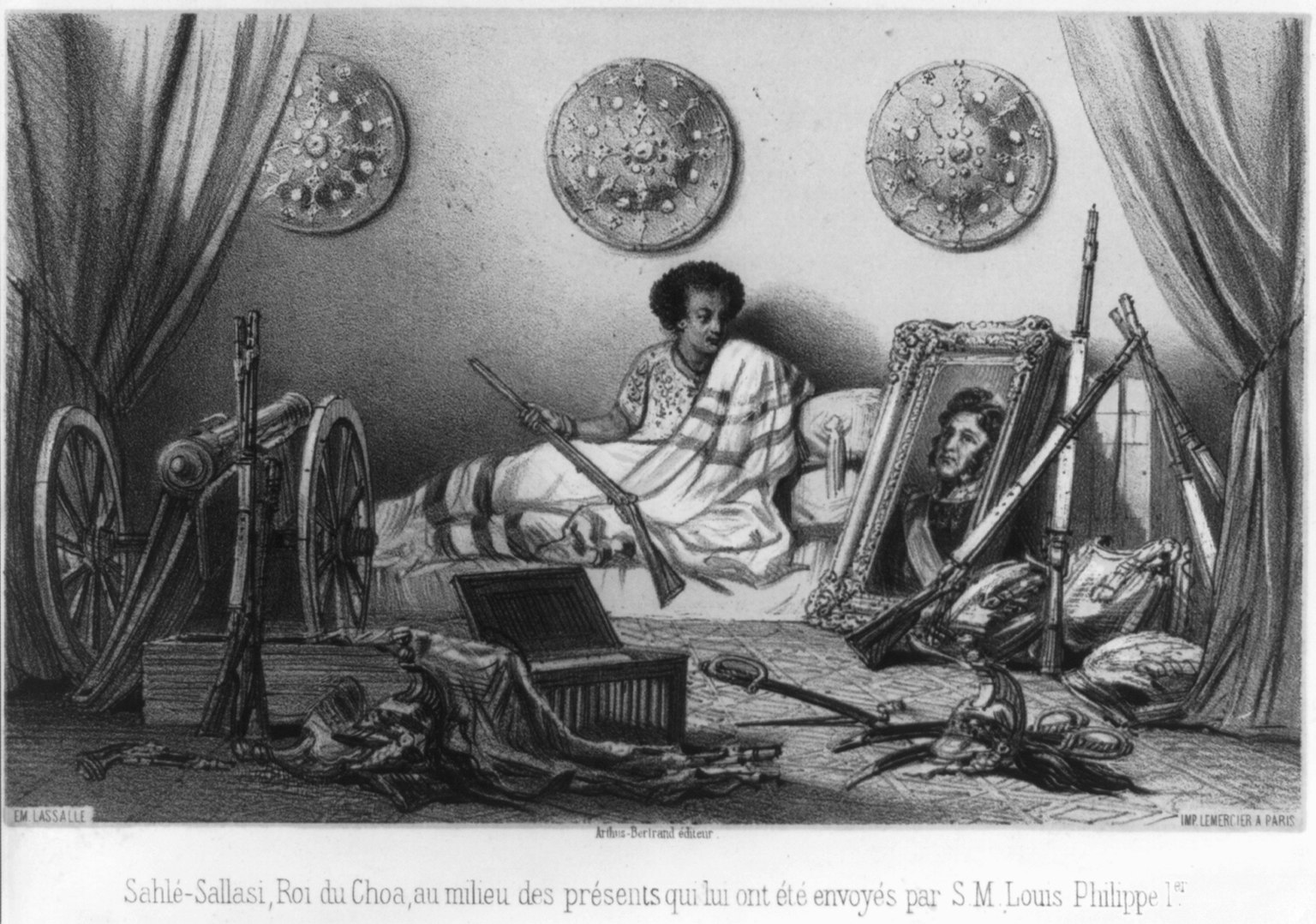

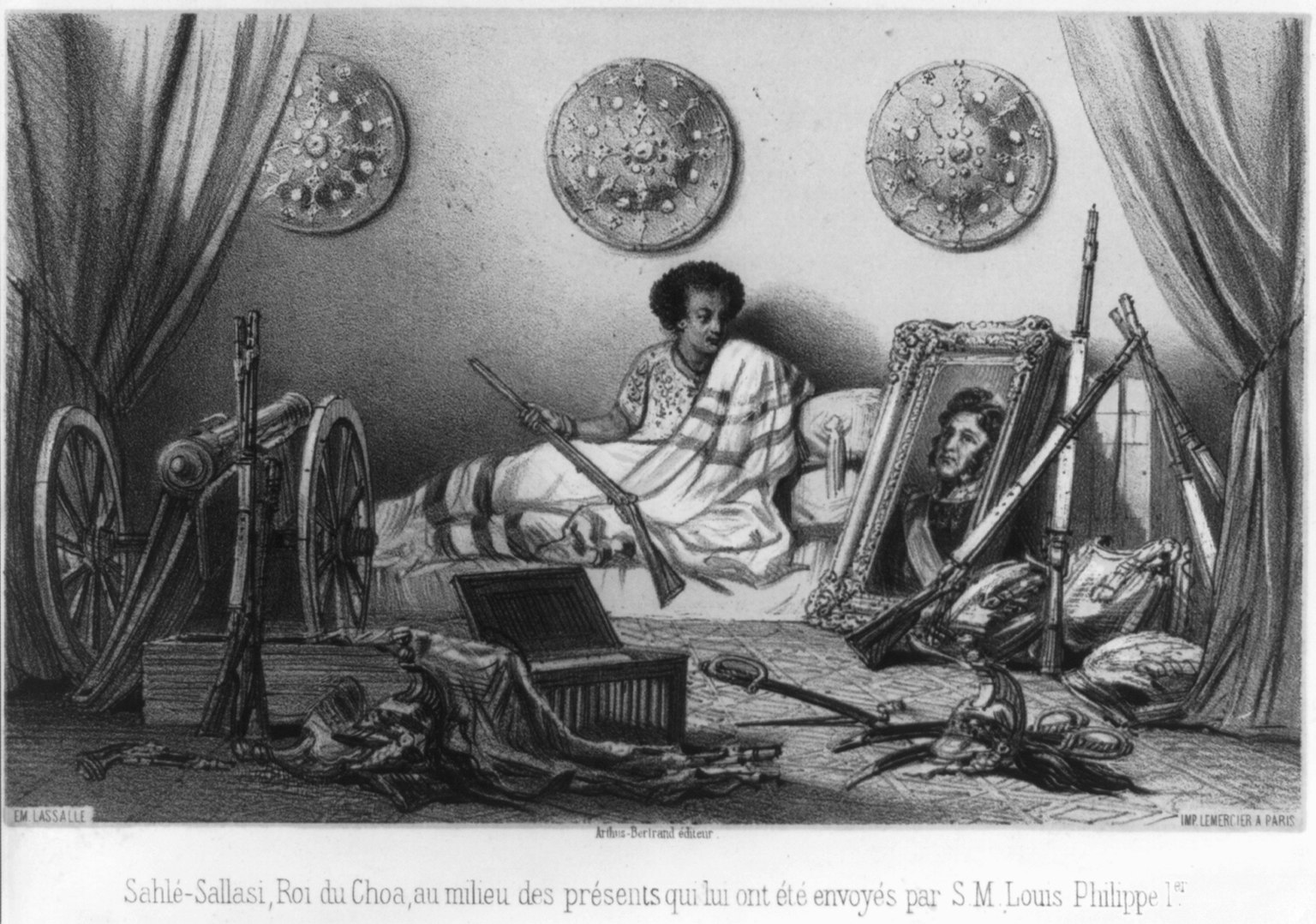

Sahle Selassie also worked to modernize his country, and like his contemporaries Goshu of

Sahle Selassie also worked to modernize his country, and like his contemporaries Goshu of Gojjam

Gojjam ( ''gōjjām'', originally ጐዛም ''gʷazzam'', later ጐዣም ''gʷažžām'', ጎዣም ''gōžžām'') is a historical provincial kingdom in northwestern Ethiopia, with its capital city at Debre Markos.

During the 18th century, G ...

and Wube Haile Maryam of Tigray

The Tigray Region (or simply Tigray; officially the Tigray National Regional State) is the northernmost Regions of Ethiopia, regional state in Ethiopia. The Tigray Region is the homeland of the Tigrayan, Irob people, Irob and Kunama people. I ...

, he made contacts with European countries like France and Great Britain in hope of gaining craftsmen, educators, and above all firearms. Like his contemporaries, he understood the value of firearms, and increased the number in his armories from a few score when he took office to 500 in 1840, and doubled that number again by 1842. He signed treaties of friendship with both France (16 November 1841) and Great Britain (7 June 1841). The Negus also encouraged foreigners to settle in Shewa, and offered considerable incentives to them, such as the revenue from a large village he granted a Greek mason by the name of Demetrios. As a result, at one point a number of foreigners were present in Shewa, who included a number of Greeks, at least one Armenian, and several traders from Eastern lands.

"Despite his understanding of the value of foreign technology and the need for craftsmen from abroad Sahla Sellase had no desire for foreign missionaries," Pankhurst notes,Pankhurst, p. 5. and although the arrival of two Protestant missionaries in 1837 led to a diplomatic mission from Britain by William Cornwallis Harris, both men were gently but firmly expelled in 1842.

Notes

{{DEFAULTSORT:Selassie, Sahle Rulers of Shewa 19th-century Ethiopian people 1795 births 1847 deaths